Orchard soil health

Those

of you who read chapter three of The

Holistic Orchard

with me this week

will probably feel like you were drinking from a fire hose. The

section

took me days to digest and I suspect I'll be trying out Phillips'

techniques for the next several years. Feel free to comment about

other parts of the chapter (of which there were many), but I want to

focus my post on soil health this week.

Those

of you who read chapter three of The

Holistic Orchard

with me this week

will probably feel like you were drinking from a fire hose. The

section

took me days to digest and I suspect I'll be trying out Phillips'

techniques for the next several years. Feel free to comment about

other parts of the chapter (of which there were many), but I want to

focus my post on soil health this week.

It's very handy to read

this chapter with soil test results in hand. I

didn't actually test my orchard soil last winter, but I have test

results from the back garden, which started with the same

type of soil,

even if it has been treated slightly differently over the years.

Here are the relevant portions of the test results:

| pH | 7.3 |

| % OM | 15 |

| P (ppm) | 556 |

| K (ppm) | 615 |

| Ca (ppm) | 6801 |

| Mg (ppm) | 926 |

| CEC | 56 |

| % Sat. K | 3.7 |

| % Sat. Mg | 17.6 |

| % Sat. Ca | 78.8 |

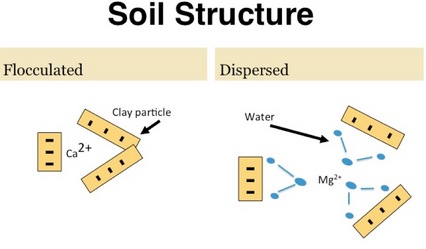

Phillips follows an

Albrecht-like ratio approach to soil health, focusing on the relative

(rather than absolute) amounts of nutrients. When I got my

results back for the garden, all of the cations were listed as "very

high", so I figured I was fine. But Phillips notes that if

there's too much magnesium (Mg) in relation to the calcium (Ca) in the

soil (for example), plants will accidentally take up magnesium while

looking for calcium and may end up deficient in the latter. In

addition, he points out that calcium tends to spread soil apart, which

can be handy for drainage and aeration in clay

soil, while magnesium pulls soil particles together (useful in

sand, but not elsewhere).

The optimal Ca:Mg ratio

(compared using the percent of base saturation figures, not the

absolute ppm figures) is 5:1 for sandy soil and 7:1 for clay. As

you can see, my ratio is 4.5:1, meaning that some of my drainage issues

might be improved by boosting calcium. However, since my pH is

already too high, I don't want to just add lime, so I'll need to look

into gypsum, which increases calcium content in soil without sweetening

the ground.

The optimal Ca:Mg ratio

(compared using the percent of base saturation figures, not the

absolute ppm figures) is 5:1 for sandy soil and 7:1 for clay. As

you can see, my ratio is 4.5:1, meaning that some of my drainage issues

might be improved by boosting calcium. However, since my pH is

already too high, I don't want to just add lime, so I'll need to look

into gypsum, which increases calcium content in soil without sweetening

the ground.

Similarly, you want to

consider the ratio of phosphorus (P) to potassium (K). Phillips

recommends P:K values of 2:1 to produce the most nutrient-dense fruits,

although 1:1 is okay in young orchards. My P:K value of 0.9:1 is

typical and signifies a need to boost phosphorus levels without

increasing the soil's supply of poassium. I'm going to have to do

some research into phosphate amendments to see which ones won't raise

our pH, but Phillips lists black rock phosphate, colloidal phosphate,

Tennessee brown phosphate, bonemeal, and bone char as possibilities.

If your head's awhirl

with numbers, here are some non-numeric soil factors to consider.

As I've mentioned previously, the goal in orchard soils is to boost

fungi at the expense of bacteria, which Phillips explains results in

more nitrogen being available in the form of ammonia.

Bacterially-dominated soils tend to have nitrogen in the form of

nitrates, which  results in happy-looking trees and big fruits,

but low nutrient density and flavor, along with more susceptability to

disease. Phillips recommends keeping your soil fungally-dominated

by making special compost for the orchard out of deciduous wood chips

slow-composted with animal manures.

results in happy-looking trees and big fruits,

but low nutrient density and flavor, along with more susceptability to

disease. Phillips recommends keeping your soil fungally-dominated

by making special compost for the orchard out of deciduous wood chips

slow-composted with animal manures.

When should you apply

that compost? I've always thought that early spring was the best

time, but Phillips gets more scientific. He explains that the

white feeder roots that suck up nutrients are even more ephemeral than

leaves --- they generally only live 14 to 60 days before dying

back. Trees produce multiple flushes of feeder roots throughout

the year, generally during periods when growth on top of the tree has

slowed, and if you time your compost applications to match root growth

periods, you'll get more nutrients to the tree. Trees focus on

blooms in early spring, roots in mid spring, leaves in early summer,

and roots in late summer and fall. Cutting herbaceous plants

under the tree canopy (like grass or comfrey) during peak root growth

can help feed your tree at just the right time, and so can spreading

compost in autumn when half of the leaves have fallen. Meanwhile,

a heavy mulch in the fall can keep the roots growing later into the

winter, and can also muffle spring warmth so trees bloom up to ten days

later and miss fruit-killing freezes.

If you can handle

another eye-opening chapter, we'll read chapter 4 "Orchard dynamics"

for next Wednesday. Those new to the club might want to check out

previous chapters on beginning

a holistic orchard

and techniques

for designing a holistic orchard. And, as always, I'm

looking forward to hearing your thoughts on this fascinating subject.

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

Do most vegetables prefer fungal or bacterial soils?

You talk about making fungus-friendly compost. Assuming your soil fertility is good, could you get the same effect through chop-and-drop?

BeninMA --- Each vegetable is a little different in terms of the fungi to bacteria ratio they prefer. You'd have to do a bit of legwork to find out anything beyond what I mentioned in the linked post --- unfortunately, that's all I know.

Chop and drop will definitely help you veer toward fungally dominated soil. You'll still need to feed most fruits and vegetables something to bring up nitrogen levels, but it's a great start.

Irma --- Mark accidentally logged in as me when he commented above. I'd definitely recommend mulch around lilacs --- all woody perennials except nitrogen-fixers are going to enjoy that.

Anna,

Go all out on the gypsum. Do it to everything you got. It's some of the best stuff I ever used. It doesn't just break up hard soils and boots calcium, but does much much more. It's beneficial to vegetables, flowers, and fruits. Be very liberal also. It doesn't burn at all. Also you can used it often.

I have to admit that all of those numbers all at once did rather get my brain in a whirl; I'll have to let them soak in a few days and re-read this post a time or two to really get my head wrapped around the point of the numbers.

On the other hand, the stuff about the feeder roots and when it's best to apply compost really got me excited! I just can't wait until I actually have this book in hand to read myself!

I just can't wait until I actually have this book in hand to read myself!

I read this and my eyes started glazing over... And my first thought was " huh.?" So I just went back to look at the puppy.

Marco --- Well, I suspect that like any soil amendment, you don't want to go all out without knowing from a soil test that gypsum is what your soil wants. From my understanding of the way it works, it causes magnesium to get washed away, which is good for my soil, but could be terrible for someone who has low magnesium levels! I'm definitely going to give it a try, though, and am thrilled to hear that your soils were perked up by the addition.

Brian -- Me too! I'm still trying to decide if I can buck conventional wisdom and spread compost in the fall or if that's just too scary for me.

De --- It's definitely much easier to read the chemistry part once you have a soil test in hand. I actually used UMass Amherst because I wanted to test for heavy metals once in the farm's life, just in case. You might enjoy reading my post about soil testing labs and comparing the cheaper options to our extension service. There are special labs that focus more on biology of the soil, but they tend to be very expensive and I'm not sure whether I believe all of their claims, so I've steered clear so far.

Ikwig --- Yeah, this part definitely needed digestion!

Marco --- (Your subject line made me smile, again. )

)

I read up a bit on gypsum after responding to your comment, and I could see how it would be hard to overdo it. The application rates are extremely high, 1,000 to 2,000 pounds per acre! And it sounds like you're totally right about the salts too. I sent Mark to the feed store after some, but they're having to order it for us. Once it comes in, we're definitely going to try some soon.

I know I'm almost 3 months behind, but I only recently had this book given to me and am getting through it now.

Although we have access to some of the materials Phillips uses to keep his soil fungally-dominated, we will need to scrounge to get it in the volume he uses.

One thing we do have access to is coffee grounds, given to us by a local coffee establishment. I'm not sure whether that would be better for the fungus in the soil (for orchards) or the bacteria (for gardens). Is there any way for me to determine this for coffee grounds - or any other compost inputs we run across? I want to make sure I apply my amendments in the places that they're most beneficial if possible.