Limiting factors in the garden

Whenever

I read permaculture-related books, I see great ideas that I can't

resist putting into practice. Some of them have amazing results,

but half or more fail miserably. Are the authors of the books

merely book learners who haven't tried out their ideas on the

ground? Sometimes. But more often, they simply fail to

mention their specific growing conditions and I forget to think about

how the ideas might mesh with my own site.

Whenever

I read permaculture-related books, I see great ideas that I can't

resist putting into practice. Some of them have amazing results,

but half or more fail miserably. Are the authors of the books

merely book learners who haven't tried out their ideas on the

ground? Sometimes. But more often, they simply fail to

mention their specific growing conditions and I forget to think about

how the ideas might mesh with my own site.

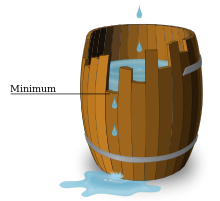

Limiting

factor is a useful ecological concept to understand when deciding

whether new ideas are worth trying in your garden. Unless you're

growing your

plants hydroponically under lights in climate-controlled conditions,

there's going to be some factor that keeps the crops from achieving

their full potential. The scientist who came up with the concept

of limiting factors used the illustration of a broken barrel to help

others visualize what he was talking about. No matter how much

water you pour into the barrel, it will only fill to the level of the

lowest stave --- the barrel's limiting factor.

Limiting

factor is a useful ecological concept to understand when deciding

whether new ideas are worth trying in your garden. Unless you're

growing your

plants hydroponically under lights in climate-controlled conditions,

there's going to be some factor that keeps the crops from achieving

their full potential. The scientist who came up with the concept

of limiting factors used the illustration of a broken barrel to help

others visualize what he was talking about. No matter how much

water you pour into the barrel, it will only fill to the level of the

lowest stave --- the barrel's limiting factor.

The most common

limiting factor for companion planted crops (and the

one that's

assumed by default in forest gardening literature) is light --- if you

plant peppers under your apple trees, the peppers will be puny because

the tree leaves steal their sunlight. In the conventional

vegetable garden, nitrogen is often assumed to be

the limiting factor since

that macronutrient can quickly wash out of the soil and since plants

won't grow much at all if faced with a nitrogen

deficiency.

Other common limiting

factors include all of the macro- and micronutrients,

water, growing

season length, cold, and heat.

In the eroded

soil of our forest garden, the limiting factor is

unusual

--- depth

of topsoil/dry soil. Once I figured out my limiting factor, I had

more of a handle on guessing which permaculture tricks were likely to

work for me.

Growing plants in the understory beneath my fruit trees is bad news in

the forest garden because these plants will compete with my trees for

the most limiting resource --- soil --- and will slow the trees' growth.

In the eroded

soil of our forest garden, the limiting factor is

unusual

--- depth

of topsoil/dry soil. Once I figured out my limiting factor, I had

more of a handle on guessing which permaculture tricks were likely to

work for me.

Growing plants in the understory beneath my fruit trees is bad news in

the forest garden because these plants will compete with my trees for

the most limiting resource --- soil --- and will slow the trees' growth.

In my kitchen peach's forest

garden island, on

the other hand, the soil

is prime, so the limiting factor is light. I'm able to grow

hungry comfrey directly under the peach's canopy with no ill effects

because there are lots of nutrients and soil space to go around and the

tree shades the comfrey enough that the understory plant doesn't

provide much competition. Instead, comfrey helps out here by

pulling micronutrients up from the subsoil to feed to the peach when

the comfrey leaves decay. Even the volunteer butternut that

showed up in the topdressed compost seems to be thriving beneath the

kitchen peach.

In my kitchen peach's forest

garden island, on

the other hand, the soil

is prime, so the limiting factor is light. I'm able to grow

hungry comfrey directly under the peach's canopy with no ill effects

because there are lots of nutrients and soil space to go around and the

tree shades the comfrey enough that the understory plant doesn't

provide much competition. Instead, comfrey helps out here by

pulling micronutrients up from the subsoil to feed to the peach when

the comfrey leaves decay. Even the volunteer butternut that

showed up in the topdressed compost seems to be thriving beneath the

kitchen peach.

If you're growing on new

ground and don't know what your limiting factor is yet, you could do

worse than follow Sara's lead. She plants a

vegetable garden in a new spot every year, adding soil amendments and

learning what makes that plot of ground tick. By the time she's

ready to plant perennials that winter, Sara knows the best spots most

likely to keep those expensive fruit trees alive, and she's also

improved the soil enough to give them a head start. Now that's

permaculture in action!

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

Emily --- I was actually thinking, as I was writing this post, that some permaculture author should write a short ebook describing the limiting factors that would make all of the most popular permaculture techniques feasible or problematic in specific situations.

Josh --- I can't really remember when I learned about limiting factors --- whether it was specific to ecology or not. I'd be curious whether other people got the concept in basic science rather than in ecology class.

The concept of limiting factors is present in all kinds of interconnected systems and the study thereof. What a lot of people don't realize is that systems in different domains are essentially equivalent.

E.g. a lot of different types of systems (mechanical, electrical, thermal, etc) can be described identically via bond graphs. Any system can be described using combinations of differential equitions and boundary conditions.

Roland --- I always love the way different kinds of science/math link together. When I was taking calculus and physics at the same time in high school and they were both talking about the derivatives from their own perspective, I was ecstatic.

Sara --- Thanks for the great idea!

I don't think of the mathematical version of limits and the greatest common factor as being similar to the ecological limiting factor, but maybe I'm not thinking about them broadly enough?

In mathematics there is a rather precise definition of a limit; it is a value that a function or sequence approaches as the input (or index for a sequence) approaches another value. Most common are the limit to 0 and ∞. Note that functions do not by definition have a limit. E.g. f(x) = sin(x) will oscillate between -1 and +1 over the whole domain of ℝ.

When considering limiting factors in dynamic systems the most generic name for it would be a bottleneck, I think.

Roland --- Thanks for backing up my memory of limits. I think the only thing really similar is the name.

And thank you for translating "limiting factors" into common parlance. You're totally right that "bottleneck" would be the proper translation!

I had to think about this one for awhile, and the link I've always held between these two concepts is completely idiosyncratic. Maybe I can save face by pointing out that both phrases have the word "factor" in them. Did anyone else catch that?

Turns out that I haven't been practicing first grade math all that much recently. Though I do add and subtract daily.

I'm reading Steve Solomon's book Gardening When It Counts at the moment, and he discusses limiting factors near the start. He uses the same "staves on a barrel" explanation.

I think it's a good way to think about garden inputs (nutrients, minerals, light, water, etc). If you read books about gardening advice and biology, it's easy to be overwhelmed and start obsessing about trying to get the ratios perfect in your fertilisers etc.

But really, there's likely only one or two limiting factors holding you back and it's usually fairly easy to figure out what it is (light, water and nitrogen are probably the most common, although it helps to think about the six macronutrients and seven micronutrients). This simplifies the problem immensely, so you only need to work on one thing at a time and iterate towards ideal growing conditions.

It's a good way to think about compost, too - the main limiting factors are carbon, nitrogen, moisture and oxygen. Getting the C:N ratio perfect doesn't matter if you don't have enough moisture (or too much moisture, which is really not enough oxygen). People obsess about compost recipes, but really it's a simple matter to just keep an eye on your compost pile and adjust whatever the limiting factor is over time.

Now that you mention it, Gardening When it Counts may be where I learned about limiting factors in the garden. That's one of my favorite gardening books --- Steve Solomon feels like my kind of grower who's serious about both ecology and yields.

Good point about applying the idea of limiting factors to compost too. I've always found in-depth compost recipes a little funny --- it seems like compost piles work pretty well by feel and eyeballing.