How to start a no-till garden from scratch

Like

Square Foot

Gardening, Lee

Reich's Weedless

Gardening is really

a

rehashing of a lot of older methods that come down to creating

permanent beds and keeping them mulched. I liked Lee Reich's book

a lot better because he included more hands on information that

answered questions I've been tossing around about my similar gardening

method. For example --- can you start a no-till garden without an

initial episode of tilling? Lee Reich's answer can be paraphrased

as "Yes, easily, and here's how..."

Like

Square Foot

Gardening, Lee

Reich's Weedless

Gardening is really

a

rehashing of a lot of older methods that come down to creating

permanent beds and keeping them mulched. I liked Lee Reich's book

a lot better because he included more hands on information that

answered questions I've been tossing around about my similar gardening

method. For example --- can you start a no-till garden without an

initial episode of tilling? Lee Reich's answer can be paraphrased

as "Yes, easily, and here's how..."

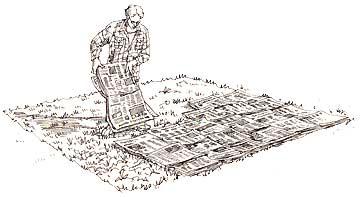

Starting a new no-till

garden is a simple matter of laying down a kill

mulch (also known as creating a lasagna bed or putting down a sheet

mulch.) Lee

Reich first

applies six cups of 5% nitrogen fertilizer per 100 square feet, then

flattens or mows the existing vegetation so that it is as low to the

ground as possible. Next, he lays down a four-sheet-thick layer

of newspaper

and tops the paper off with one to three inches of mulch. If he

plans to plant into the bed immediately, that mulch

would be compost, but the mulch could also be any of the materials I'll

discuss tomorrow if you're making a bed for later use. In

his own garden, Lee Reich lays out compost as mulch in the permanent

beds and wood chips as mulch in the aisles.

I got a bit bogged down in

Lee Reich's statement that he uses 5%

nitrogen fertilizer, as well as by his later explanation that he uses

soybean meal to give his garden a nitrogen boost every year. As

with Steve Solomon's complete

organic fertilizer,

I think that high

nitrogen inputs like this may pass the "organic" test, but fail

my permaculture test. Adding nitrogen to the soil in any

concentrated form kills off some of the beneficial soil

microorganisms, and I can't help feeling that burning oil to cultivate

fields of soybeans then using those soybeans to grow vegetables is

about as far as you can get from a closed loop. All of that said,

Lee Reich has a valid point that you need a bit of high nitrogen at the

beginning

of the no-till process to counteract the high carbon of the weeds being

killed.

Why not run chickens over that patch of ground instead, or toss down an

equivalent amount of chicken manure?

I got a bit bogged down in

Lee Reich's statement that he uses 5%

nitrogen fertilizer, as well as by his later explanation that he uses

soybean meal to give his garden a nitrogen boost every year. As

with Steve Solomon's complete

organic fertilizer,

I think that high

nitrogen inputs like this may pass the "organic" test, but fail

my permaculture test. Adding nitrogen to the soil in any

concentrated form kills off some of the beneficial soil

microorganisms, and I can't help feeling that burning oil to cultivate

fields of soybeans then using those soybeans to grow vegetables is

about as far as you can get from a closed loop. All of that said,

Lee Reich has a valid point that you need a bit of high nitrogen at the

beginning

of the no-till process to counteract the high carbon of the weeds being

killed.

Why not run chickens over that patch of ground instead, or toss down an

equivalent amount of chicken manure?

No matter how you get

the extra nitrogen to the soil, Lee Reich explains

that you don't need to (nor should you) dig up your soil by hand or

with a rototiller except in a few rare cases. If you have to make

drastic changes to your soil pH, you will need to dig the lime  or

sulfur into the soil, and if you're the unlucky inheritor of hardpan,

you'll have to break up that tough soil layer before returning to

no-till techniques. Lee Reich is generally opposed to raised

beds, which he notes dry out quickly (and require an initial round of

digging), but he does admit that areas with bedrock just beneath the

soil surface or with a very high water table (like we have) will

benefit from raised beds.

or

sulfur into the soil, and if you're the unlucky inheritor of hardpan,

you'll have to break up that tough soil layer before returning to

no-till techniques. Lee Reich is generally opposed to raised

beds, which he notes dry out quickly (and require an initial round of

digging), but he does admit that areas with bedrock just beneath the

soil surface or with a very high water table (like we have) will

benefit from raised beds.

In most cases, though,

starting a new weedless garden is as simple as

adding a nitrogen input, mowing, tossing down a layer of paper, and

then topping it all of with mulch. In less time than it would

have taken to till the ground, you've created a new growing space and

preserved the soil structure and organic matter.

| This post is part of our Lee Reich's Weedless Gardening lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

this was an awesome post -- thanks for taking the time to do it.

you guys really exemplify a value-added, well-managed blog!!!

•As far as mulch, your garden is much bigger than most gardens, perhaps bigger than it has to be. I grow a year round supply of vegetables for me and my family on a couple of thousand square feet of space. Wood chips, perhaps a couple of loads per year are delivered free. Leaves are delivered free or I pick them up in suburban neighborhoods. I make many tons of compost from garden and kitchen waste, hay scythed from a half acre field here, and, occasionally, some horse manure waste from a local horse farm.

•As far as the soybean meal, I've pretty much abandoned it. One inch depth of compost should supply all plants nutritional needs. Also, I question the killing of microorganisms from soybean meal; some will thrive on the N, others won't. The N is released slowly into the soil via the action of microorganisms. Chickens would mess up the garden and, anyway, don't provide free nitrogen if you feed them. (Mine get fed only enough to know where home is.) They mess up the beds so aren't allowed in my garden.

•Also, I could not get my chickens to drink from Avian Miser. Perhaps there was too much other water around for awhile. Perhaps they're too stupid.

I really appreciate you stopping by and adding in this valuable information! I love seeing what mulch you're finding --- cutting your own hay is one that I hadn't even considered.

I'm very sorry to hear you had trouble with our waterers! I sent you a slew of tips in an email, so hopefully that will turn your flock around. Chickens do seem to be creatures of habit, so if you're not able to take their old waterers away, they don't seem to try a new system.

Hi Anna. I was just browsing at previous posts you've made to pick up as much information as i can.That's why i'm hovering at an older post.

Your comment : "and if you're the unlucky inheritor of hardpan, you'll have to break up that tough soil layer before returning to no-till techniques"

Well i was wondering, i live in Georgia with of course the infamous Georgia Clay. I've read of hardpan soil but was really unsure what it really meant. Is it just a place where water puddles to a great extent because it cannot infiltrate the soil? Because clay is hard stuff, no matter where you go in Georgia, so could it all be classified as hardpan? Also is it possible to break it up soley with deep rooted cover crops?(I know i hit on this alot. But i'm always curious about their uses)

Thanks Jalen

Hardpan is different from lots of clay soil --- we've got the latter, but not the former. Hardpan is a nearly rock-like layer of compacted soil that prevents water and roots from penetrating. It's generally formed when people run heavy equipment on damp soil, which compresses the ground below the normal plow depth. Some cover crops, like oilseed radishes, have been proven to be able to break through hardpan.

Unless you're growing in an area that has been plowed with heavy machinery for years or has otherwise been compacted (like being parked on by the family car), you probably just have lots of clay. The solution to clay is copious organic matter, which I'd add in the form of grain cover crops, compost, and mulch.

In conventional agriculture, the rows aren't permanent because you plow up the soil every year and then create new rows. The primary benefit of a permanent bed over tilling and creating rows every year is lack of soil compaction --- since you keep your walking, wheelbarrowing, etc., on the aisle, the permanent bed soil stays fluffy without tilling. Another benefit is efficient use of soil amendments --- you apply compost and mulch to the bed, not the aisles, so you're not wasting amendments on non-growing space. Add to that lack of tilling, which keeps organic matter in the soil rather than burning away. The combination tends to result in soil that gets better and better over time, rather than slowly degrading.

There is a machine you can pull with a tractor that makes long, semi-raised beds, but I don't think I'd say that my methods can be used on an industrial farming scale. The reason farmers till every year and use rows is so that they can come back through and till the aisles again for weed control with nearly no human effort. Conventional "no-till" farming tends to use herbicides to kill weeds, which is probably worse. So, no, you couldn't just scale my garden up and fix our food supply.

Personally, I think we need to scale our agriculture system down and have everyone growing their own food instead. I grow all of our vegetables, a good amount of our starches, and an increasing amount of our fruits and meat using the same amount of time the average American spends parked in front of the TV --- there is time in our lives to grow food if we want to take it.

"Personally, I think we need to scale our agriculture system down and have everyone growing their own food instead. I grow all of our vegetables, a good amount of our starches, and an increasing amount of our fruits and meat using the same amount of time the average American spends parked in front of the TV --- there is time in our lives to grow food if we want to take it."

Very well said, i couldn't agree more.

Anonymous --- Thanks for the agreement!

Jalen --- Keep asking questions. I enjoy answering them and am glad to meet someone else interested in the same agricultural issues I am.