How to make a cleft graft

Now that I've cut

the top off of my young tree, I can insert the

scionwood. Step one is to slit the trunk of the tree vertically

for about two inches --- making the cleft.

Orchadists have special

tools for cleft grafting, but I figured I could find everything I

needed between the kitchen and the toolbox. The small, sharp

knife shown below was too miniscule to do the job, but a big, dull

butcher knife combined with a hammer was just right.

I hammered the big knife

into the center of the trunk, then pounded on the sides of the knife to

insert it a bit deeper. On my second tree, I didn't make the slit

quite so deep, and found it more difficult to insert the scionwood, so

be sure to make your slit big enough the first time.

The next step is to

widen the cleft using a wedge. Again, professionals use a special

tool for this procedure, but a screwdriver pounded in easily and worked

great.

Cut

the scionwood as described previously, then insert two pieces, one

on

each side of the wedge. If the cleft isn't quite as open as you'd

like, you can rotate the screwdriver slightly to widen the gap.

Cut

the scionwood as described previously, then insert two pieces, one

on

each side of the wedge. If the cleft isn't quite as open as you'd

like, you can rotate the screwdriver slightly to widen the gap.

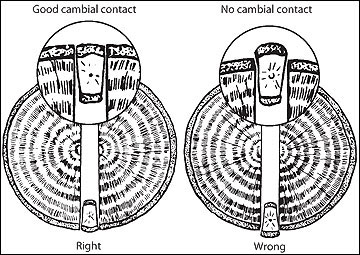

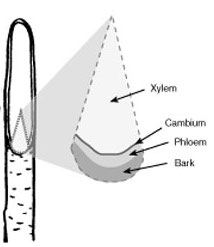

Scionwood insertion is

the trickiest and most important part of the whole process, so take a

few minutes to make sure you're doing it right. The diagram below

shows a cross section through a piece of scionwood, illustrating the

layers of different kinds of cells that make up a twig.

You can think of the cambium

as the stem cells of the plant world --- the cambium cells are still

physiologically flexible and can grow together with the cambium of a

different tree. The cambium is relatively easy to see if you have

good eyes since it tends to be bright green. Your goal is to make

sure the cambium of your scionwood lines up with the cambium of the

tree you're grafting onto.

You can think of the cambium

as the stem cells of the plant world --- the cambium cells are still

physiologically flexible and can grow together with the cambium of a

different tree. The cambium is relatively easy to see if you have

good eyes since it tends to be bright green. Your goal is to make

sure the cambium of your scionwood lines up with the cambium of the

tree you're grafting onto.

Your gut reaction will

probably be to try to make the scionwood fit flush against the side of

the tree being grafted onto, but that's not quite right. As a

tree grows, it not only expands the xylem (the woody part in the

center), but also the phloem (which turns into the bark). So, the

cambium is going to  be a little deeper into the

older tree being grafted onto than it is on the little twig of

scionwood. That's why most people recommend making sure your

scionwood is slightly indented as you look at your graft from the side.

be a little deeper into the

older tree being grafted onto than it is on the little twig of

scionwood. That's why most people recommend making sure your

scionwood is slightly indented as you look at your graft from the side.

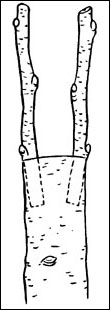

One way to hedge your

bets is to insert your scionwood at a slight angle, as is shown in the

drawing to above, so that the cambial layers intersect somewhere. This type of angled

scionwood placement won't give you as strong a connection, but is

better than nothing if you're not sure you'll get your cambial layers

lined up otherwise.

One last note on

scionwood placement (which you really should have considered when

making your cuts) --- most sources recommend that the first bud on your

scionwood sits just above the top of the tree being grafted onto.

If you had extra scionwood length, now is a good time to cut each one

down to two or three buds. Stay tuned for tomorrow's post, in

which I'll explain how to seal the cut surfaces.

| This post is part of our Grafting Experiment lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

Wedge: I honestly cannot believe anyone would buy (or even design) a wedging tool specifically for that purpose. Is it really a wedge or does it look like a speculum? If you needed more control than a screwdriver, why on earth wouldn't you just use a chisel or a wedge cut from a block of wood?

Varietal Dominance: What stops the larger, established rooted tree from taking over the scionwood? Is it more like dominant and recessive genes or simply because the scionwood has buds at the highest point? Or is the result ultimately a hybrid tree with hybrid fruit? ] j [

Excellent questions, Jeremiah! From what I can see, the wedge tool that grafters use doesn't just act as a wedge -- it also is a bit of a pry bar and knife, all in one. So, you skip the cutting step, just pounding the wedge tool in and then prying the cut open. I'm sure the idea is speed --- you would probably topwork a whole orchard much faster with the fancy tool.

The answer to your second question is twofold. The way plants work, once you graft a piece of tree onto another piece of tree, everything that grows from that second piece is built by the second piece (though fed by the roots on the first piece), so the main stem of the tree looks and acts like the second piece. This is pretty different from breeding, where the genetics from two parents get mixed up. It's a bit like if you cut your mother and father in half and sewed them back together around the waist. You'd have your mother's feet and your father's nose, and the combination wouldn't make the hair you grew more like your mother's. (Please don't try this at home. Thought experiment only....)

Thought experiment only....)

However, you do have to be careful, because the lower parts of the tree will still sprout vigorously. Those sprouts will be the old variety, so you have to cut them away once the new variety gets established. After a year or two, though, the roostock starts to behave because of apical dominance --- plants put most of their energy into the highest up bud(s). That's the same reason that if you want a plant to bush out, you pinch off the top, deleting the apical dominance and giving the side buds free rein.

Must there be bark and cambium on interior side of scion? www.waldeneffect.org/20120302cambiumgraft.jpg