How to grow your own rootstocks

When I summed up the purposes

of grafting, I

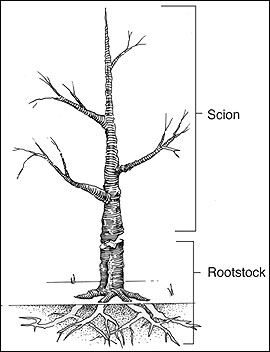

warned you that grafting won't create more plants, just change a

rootstock from one variety to another. So where do all those

rootstocks come from?

When I summed up the purposes

of grafting, I

warned you that grafting won't create more plants, just change a

rootstock from one variety to another. So where do all those

rootstocks come from?

If you want to grow your

own fruit tree rootstocks, you have two choices --- seeds or

cuttings. Seedling rootstocks are easy to grow --- just collect

pits from the fruit you eat and plant the seeds --- and seedlings have

the benefit that they're usually vigorous and healthy. With some

types of fruits, like peaches, a seedling roostock can be a good

choice, but most homesteaders with a small backyard won't want to grow

their apple rootstocks from seed since a standard apple tree can take

over their entire growing space. Instead, nurseries count on

carefully selected and vegetatively propagated rootstock varieties to

change the size of their trees and to confer resistance to disease.

Vegetatively propagated

rootstocks are much more uniform than those

grown from seed, although you have to make an investment of space and

time to grow your own. You can either root cuttings (softwood or hardwood) or use layering (a method

of making one plant produce lots of shoots, which root and can be

severed to create new plants). Garner notes that cuttings can

usually be rooted for apples, pears, plums, and cherries, although my

own experience has shown that softwood cuttings need a lot of babying

and might not be worthwhile if you don't have the right

equipment.

Vegetatively propagated

rootstocks are much more uniform than those

grown from seed, although you have to make an investment of space and

time to grow your own. You can either root cuttings (softwood or hardwood) or use layering (a method

of making one plant produce lots of shoots, which root and can be

severed to create new plants). Garner notes that cuttings can

usually be rooted for apples, pears, plums, and cherries, although my

own experience has shown that softwood cuttings need a lot of babying

and might not be worthwhile if you don't have the right

equipment.

Stooling is a type of

layering that seems very easy for the beginner. You simply plant

a purchased rootstock, let it grow for a year, cut the tree to the

ground, then mound up dirt around the shoots to create new rootstocks

that can be removed later. The downside of stooling is that it

takes two years before you get your first harvest, but the stool can

produce for twenty or more years after that. If we like the

rootstock we use for our high

density apple experiment, I think it would be worth

starting a stool so that I could create our own dwarf apples in the

future.

Some more complex types of

layering are used for various reasons. Etiolation (in which the

shoots arising from the rootstock are pegged down in a trench) is used

for shy rooters, like apples, pears, quince, plum, cherries, peaches,

walnuts, and mulberries. Etiolation is more work than stooling,

so should be considered only if you can't get your stock to root

otherwise. Similarly, air layering (in which a shoot is injured

and then surrounded with moist material to root above the soil line) is

a very sure technique, but doesn't produce as many offspring. At

the other extreme, tip layering is an easy way to get blackberries,

some raspberries, currants, and gooseberries to root.

Some more complex types of

layering are used for various reasons. Etiolation (in which the

shoots arising from the rootstock are pegged down in a trench) is used

for shy rooters, like apples, pears, quince, plum, cherries, peaches,

walnuts, and mulberries. Etiolation is more work than stooling,

so should be considered only if you can't get your stock to root

otherwise. Similarly, air layering (in which a shoot is injured

and then surrounded with moist material to root above the soil line) is

a very sure technique, but doesn't produce as many offspring. At

the other extreme, tip layering is an easy way to get blackberries,

some raspberries, currants, and gooseberries to root.

No matter how you start

our rootstocks, you need to grow the young plants until they're well

rooted before grafting onto them. Budding is often done the first

summer, but dormant grafting such as whip-and-tongue grafts have to

wait another year. So, if you planted a rootstock from the

nursery now, you could cut it to the ground to start a stool in fall

2013, mound up earth around the new shoots in 2014, cut loose your

rootstocks that winter, and graft onto them in early spring of 2016.

In case that seems

daunting, I should tell you that you can often order rootstocks

of named varieties from various nurseries. In addition, you

should check

with your local extension office since many run grafting workshops in

the spring which provide all of the rootstocks, scionwood, and

paraphernalia, allowing you to come home with several newly grafted

trees for a very small fee. A final option is to skip the rootstock entirely and graft a new branch onto an existing fruit tree in your yard.

I'd be very curious to

hear from anyone who has grown his or her own rootstock. Which

method did you use? Do you recommend it to others?

| This post is part of our Grafting lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

Thanks for the informative post! I enjoy Learning new stuff..so when the day comes I am ready to try some grafting, I've got a little background to start with. Enough to at least know where to look for more detailed instructions! You must read ALOT!

Thanks for the very interesting grafting post. I have germinated several apple seedlings, and was thinking of grafting on to them. The vigour of seedling rootstock appeals to me, considering my poorer soil. Everyone says the tree will get too large for a backyard. But just wondering - why can't the size of a tree be controlled, to any size, by constant pruning ? Especially if only a few trees need to be pruned, so labour is not a problem.

John --- Excellent question, and one I'll be experimenting with this coming year with our high density apple planting. The short answer is that if you just prune to keep a tree small, it will respond by sending up lots of vegetative growth and setting back its fruiting.

However, it clearly can be done --- for example, the San Francisco forest garden we visited this summer had a miniature planting based on full-size rootstocks. And one of our readers does the same. I'll be figuring out the tricks and posting about them this year.

Thanks Anna, much appreciated. I will be most interested in the results of your apple tree experiments. John

Anna,

The M9 series of dwarf rootstock are prone to suckering (lots of new shoots popping up from the roots around the base of the tree). While this is generally a nuisance, it is also a boon for us grafters. Dig down around the roots of your suckered tree (one side only, to prevent too much root damage from stunting the existing tree) and cut off the strongest looking suckers along with their root ball. Pot up, or drop straight into the nursery patch and let them develop for a couple of years before cutting back and using as rootstock for your new tree.