How to count varroa mites with a sticky board

People

like to say that varroa mites on honeybees are a lot like ticks on a

dog, but when you compare the relative sizes, you'll see that a varroa

mite is more like a blood-sucking squirrel latched onto your dog's

back. Given the size of the mites, it's not surprising that a

heavy varroa mite infestation can weaken a hive so much that it dies

over the winter.

People

like to say that varroa mites on honeybees are a lot like ticks on a

dog, but when you compare the relative sizes, you'll see that a varroa

mite is more like a blood-sucking squirrel latched onto your dog's

back. Given the size of the mites, it's not surprising that a

heavy varroa mite infestation can weaken a hive so much that it dies

over the winter.

Most beekeepers treat

their hives with insecticidal strips during the fall and winter, but

the chemical control method has obvious problems. You have to be

extremely careful not to eat any of the honey that was in the hive

during the treatment period, which makes life difficult the next spring

if the bees didn't consume all of their winter stores. Beekeepers

who throw in chemicals every year without testing to see whether their

hives need it also start to run up against pesticide-resistant mites

--- bad news. Finally, the organic gardener in me has to wonder

what such a heavy dose of insecticide does to the honeybees.

Luckily, there are alternatives.

We use quite a bit of

passive management designed to reduce varroa mite populations in the

hive. Foundationless frames and screened bottom boards

both help cut down on varroa mite infestations, and the latter also

allows us to monitor how many varroa mites are actually present so that

we don't put chemicals in a hive that isn't very heavily

infested. With winter looming, I figured I'd better check the

mite levels in our three hives.

Homemade

varoa mite test sheets

Homemade

varoa mite test sheets

You can buy varroa mite

test sheets ("sticky boards") from bee supply stores, but I'm too cheap

so I've experimented until I figured out an easy way to make the sheets

at home. Just cut a piece of cardboard to 13" by 20", tape down

white scrap paper on one side, and smear on petroleum jelly (vaseline)

until it covers the entire surface of the paper. If you've got

more than one hive, it's best to label your various test sheets before

bringing them outside in order to avoid confusion. Slip one test

sheet under the screened bottom board of each hive, then remove it

three days later and take a look.

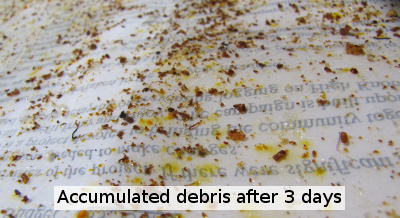

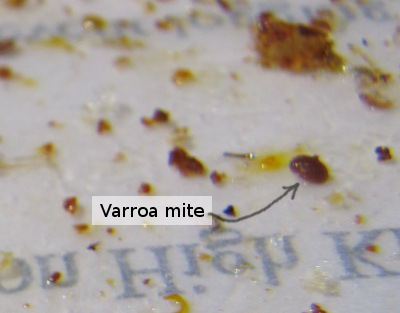

Chances

are, your test sheet will be coated in debris, so you'll need to look

carefully to see the round, dark brown varroa mites. If you're

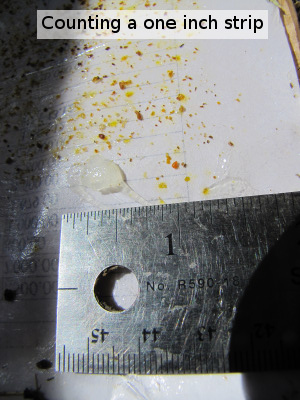

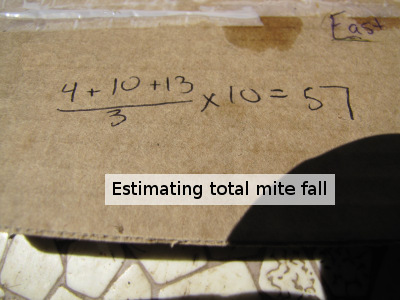

industrious, you can count every mite on the sheet, but I generally

just rule off three strips, each one inch wide, and count the mites in

each one. Since the screened section of the bottom board is ten

inches wide, adding up the number of mites in my three strips, dividing

by 3, then multiplying by 10 gives a rough estimate of total varroa

mite fall during the three day period. My three day mite counts

came to 57 and 40 in my two smaller hives, and a whopping 540 in my

biggest hive.

Chances

are, your test sheet will be coated in debris, so you'll need to look

carefully to see the round, dark brown varroa mites. If you're

industrious, you can count every mite on the sheet, but I generally

just rule off three strips, each one inch wide, and count the mites in

each one. Since the screened section of the bottom board is ten

inches wide, adding up the number of mites in my three strips, dividing

by 3, then multiplying by 10 gives a rough estimate of total varroa

mite fall during the three day period. My three day mite counts

came to 57 and 40 in my two smaller hives, and a whopping 540 in my

biggest hive.

Varroa

mite threshold

Varroa

mite threshold

The hardest part of

checking on varroa mites is figuring out how many mites you can have in

your hive without worrying. A quick search of the internet and my

bookshelf yields up numbers ranging from 50 mites per day to 200 mites

per day as the treatment threshold. For a three day mite count

like mine, that means I can have somewhere between 150 and 600 mites on

my test sheets without taking action.

The reason the threshold

figures vary so much is that you'll get widely variable mite fall

numbers from the same hive when you test during different parts of the

year even if the percentage of bees infested by mites stays the

same. Since the typical hive has few bees in it during early

spring, few mites will fall to the ground. The same hive in the

middle of summer may have ten times as many bees present (or more), so

you'd expect to see ten times as many mites. With that

information in mind, it's not all that surprising that the hive we

bulked up with early double deeps has many more varroa mites

than the hives which began the year with a single brood box.

A North

Carolina beekeeping document suggests a way to deal with

this inherent problem in the sticky board test method. They tell

you to estimate how many adult bees are present in the hive by counting

how many frames are completely coated on both sides with bees during

your inspection. A medium frame thus coated will hold about 1,250

bees and a  deep

frame will hold about 2,000 bees. If your sticky board count

shows more than 2 mites per thousand bees per day in mid-August or more

than 4 mites per thousand bees per day in September, you should find a

way to reduce the mite population. Unfortunately, I hadn't read

this the last time I opened the hive, so I don't have any data

available except my gut reaction that one of my hives has many more

bees than the others.

deep

frame will hold about 2,000 bees. If your sticky board count

shows more than 2 mites per thousand bees per day in mid-August or more

than 4 mites per thousand bees per day in September, you should find a

way to reduce the mite population. Unfortunately, I hadn't read

this the last time I opened the hive, so I don't have any data

available except my gut reaction that one of my hives has many more

bees than the others.

Clearly, I don't need to

worry about two of my hives at all since they averaged 13 and 19 mites

fallen per day. My biggest hive, though, has ten times as many

mites even though I estimate it only has perhaps two or three times as

many bees in the hive. I could treat that hive, but I had a

colony that was similarly on the edge last fall and it made it through

the winter with flying colors, so I'm going to take my chances.

As I turn into a more experienced beekeeper (and have more data from my

own hives), I'll feel more confident about which varroa mite levels are

no big deal and which ones require drastic action.

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

This is my first year as a beekeeper and i was informed by my bee club to treat for the Varroa mite . i have 6 hives and I'm using Apiguard. What would be a high Varroa count after four days of treatment? I have 6 hive and the numbers are high one hive is around 350 mite count the others are below 80. each day the numbers are lower. should i be worried and what should i do to help the hive with the high count. Loss in the Varroa world.

Jake