High carbon materials for humanure composting

Next week, I'll continue our

humanure lunchtime series by delving into several different types of

composting systems. However, before you get too excited, I want

to take a step back and consider the biggest issue with humanure

composting.

Next week, I'll continue our

humanure lunchtime series by delving into several different types of

composting systems. However, before you get too excited, I want

to take a step back and consider the biggest issue with humanure

composting.

No, I'm not talking

about disease. Joseph Jenkins does an admirable job of explaining

how a well-managed humanure recycling system is perfectly safe.

(Check out The

Humanure Handbook if

you don't believe me.) I'm more concerned with an issue that's

already problematic on our farm --- a paucity of high

carbon materials.

We've been experimenting with deep

bedding in our

chicken coop for the last couple of years, which is a bit like a

humanure composting system for chickens. Theoretically, the idea

has merit, and it does work pretty well in practice, but I'm always

scrambling in search of quality bedding.

We've been experimenting with deep

bedding in our

chicken coop for the last couple of years, which is a bit like a

humanure composting system for chickens. Theoretically, the idea

has merit, and it does work pretty well in practice, but I'm always

scrambling in search of quality bedding.

In a pinch, I can use straw, but I don't like buying carbon for my

chickens to poop on, and the optimal bedding is higher in carbon and

smaller in size so chickens can scratch through and mix the bedding

regularly. When we run out of autumn leaves, either raked from

the woods or collected by my kind mother during city trash pickup days,

manure piles up, smells turn foul, and flies start to plague our porch

dinners. The conclusion is: we don't have enough high carbon

materials for essential uses right now without diverting some to a

humanure composting system.

Jenkins recommends

hunting down 20 cubic feet of sawmill sawdust per hundred pounds of

human body weight in the household per year, which (rounding up to

include guests and to give us a bit of wiggle room) would equate to 80

cubic feet (600 gallons) for us. That's 120 five gallon buckets

or 7 of our 95

gallon wheelie bins full --- a pretty hefty helping of sawdust for

which

we've yet to find a source. In addition, he recommends having

about ten bales of straw or hay on hand for covering the outdoor

pile. (I'll explain more about the uses of the two types of high

carbon material in a later post.)

Jenkins does offer sawdust

alternatives, including peat moss, leaf mould, rice hulls, or grass

clippings (although I'm not so sure grass clippings would work well ---

they're pretty high in nitrogen). However, all of those sources

would either have to be bought or would require considerable effort to

gather, making their use equally problematic.

Jenkins does offer sawdust

alternatives, including peat moss, leaf mould, rice hulls, or grass

clippings (although I'm not so sure grass clippings would work well ---

they're pretty high in nitrogen). However, all of those sources

would either have to be bought or would require considerable effort to

gather, making their use equally problematic.

Mark isn't a fan of humanure composting, so he was very relieved when I

told him I couldn't even consider a system until we stock up on enough

high carbon bedding for the chickens plus a year's supply for a

humanure system. Looks like we'll be scouring the countryside in

search of a sawmill....

| This post is part of our The Humanure Handbook lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

I had the same struggle.

First, I found planar shavings. There are lots of woodworkers around here, and they were glad to have help getting rid of it. However, this doesn't work as well as sawdust, taking a very long time to break down.

I looked everywhere for something better, and finally broke down and bought a truckload of sawdust from a sawmill. 40-45 yards. It's huge. It will last years. Most of the price was the cost of trucking it to me.

Recently a neighbor had some trees cut and milled. He asked me to help him get rid of the sawdust, so we headed over with snowshovels and filled the truck. (Remember to put a tarp down first, and close the back window!)

Jay --- The Humanure Handbook does make a firm distinction between sawdust from a woodworking shop and the wetter sawdust from a mill. Like you, I'd be thrilled to buy a truckload of sawdust from a mill, but haven't found a place that would deliver it. I guess I should look into that....

Nolan --- The trouble with grass isn't the wetness, but the nitrogen. You want to add high carbon materials to counteract the high nitrogen humanure so that the mixture is close to the 30:1 C:N recommended for making compost. That's why sawdust works so well --- it has a C:N of about 200:1 to 500:1 (depending on type of tree and whether it's partially rotted). Grass clippings have a C:N of 15:1, which means that they'll off-gas nitrogen when composted by themselves and won't counteract any other high nitrogen materials.

We do get wood chips, which we rot down and use for mulch around trees and berries. But the author of The Humanure Handbook notes that wood chips don't work well with humanure because of their consistency, which is very different from sawdust.

I like your shredded paper idea best, although we live way out in the country and don't have sources nearby.

If you live in a rice growing area like Louisiana, Missouri, or Gulf Coast TX (if my 8th grade geography lessons served me well there...) you can probably get some rice hulls cheap. That is what we use. Downside is possible pesticides on them. But usually they are not sprayed after they flower.

A chainsaw probably spits a fair amount of quality sawdust as well. Not 20 cubic feet per person, and harder to gather, but it is a bit.

I have a friend in Equador who uses soil. It comes out very improved by the end of the composting.

And finally, fall leaves are excellent as well.

Eric --- We've been collecting sawdust when we cut bought firewood down to our smaller stove size with the miter saw. It doesn't add up to all that much, but is handy. Wish we were closer to the rice-growing region....

I'm not sure about the method of using soil. I suspect what it does is cut down on smell, but that you end up losing a lot of nitrogen (which is generally the problem if you don't mix manure or urine with a high C:N additive).

Darryl --- If we were cutting firewood on a lawn or driveway, a tarp might work well. But just trying to lay down a tarp in our woods would end up trampling all the undergrowth and almost definitely ripping the tarp a few times!

I wish they made some kind of attachment that bagged sawdust as it was made. I sometimes gather up little piles of it by hand after Mark cuts wood, but it's hard to get much....

Chapters 4 and 5 of the humanure handbook didn't contain much useful information, IMO.

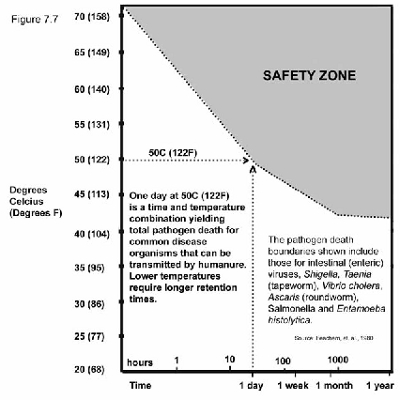

Chapter 6 was an interesting overview of low temperature systems. And chapter 7 deals with disease-causing agents in urine and excrement. What I don't get is why the author dwells on those, when the point has already been made in earlier chapters that you'd need relatively high temperatures to get safe compost?

Chapter 8 seems the most interesting chapter of the book so far; a working high-temperature composting system. Since the author has done measurements of his compost piles' temperatures as well as had his compost tested for nutrients and disease vectors, it seems to me the most valuable chapter of the book.

Doc --- In my understanding and experience, composting is a bit like baking a cake. If you don't get the proportions right, something goes wrong. Putting dirt over top would be like slapping a lot of frosting on a slumped cake --- it might look okay until you bit into it.... (And now you know what kind of cook I can be...

(And now you know what kind of cook I can be...  )

)

When you don't add much carbon to a compost pile, microorganisms break down the nitrogen into a gas and much of it is lost to the air. So a barrier like dirt would hold that gas in place in the pile, but wouldn't prevent its production in the first place. Presumably, when you cut into the pile with a shovel, you'd get off-gassing.

With the right proportions of carbon and nitrogen in the compost pile, there is no outgassing, so the finished product is actually higher in nitrogen. In addition, the carbon gets converted into humus, which is what separates the effects of compost from the effects of short term chemical fertilizers. Sure, plants take in carbon dioxide out of the air, but humus holds water, provides a home for handy soil microorganisms, and slowly releases nitrogen over time --- it's essential for good organic gardening.

Roland --- Yep, those are other parts of what I mean by it being a self-published book --- repetitive, has trouble getting to the point... I think some people are afraid that if the book doesn't look long enough, no one will buy it. Too bad because I vastly prefer to read a short, to-the-point book!

I think some people are afraid that if the book doesn't look long enough, no one will buy it. Too bad because I vastly prefer to read a short, to-the-point book!

Would e.g. the dead branches on your property make enough sawdust when processed with a sawdust maker?

Ah, another great post. I keep on finding my way to your blog quite often! I'm looking into low-energy in-house carbon sources for humanure. We don't produce enough sawdust, but there are loads of leaves, and potentially enough straw, both from grasses and from reeds.

Does anybody have experience with any? I can imagine that dry leaves could work, even without processing. But, according to Joseph Jenkins, straw doesn't, due to particle size. I'm looking into efficient ways of making "straw-dust"... any thoughts?