Heat management in the Warre hive

Heat retention is such an

integral topic to Warre beekeeping that I thought it deserved

its own post. The entire hive is designed around the idea of

making the inside easy for the bees to keep warm while preventing too

much heat loss (or gain in extremely hot areas) from the outside.

Heat retention is such an

integral topic to Warre beekeeping that I thought it deserved

its own post. The entire hive is designed around the idea of

making the inside easy for the bees to keep warm while preventing too

much heat loss (or gain in extremely hot areas) from the outside.

The extra boxes at the

top of the Warre hive are meant to prevent condensation inside the hive

while still keeping the interior warm. The part I'm the least

clear on is the vent under the eaves of the roof --- it doesn't connect

to the rest of the hive, and I think its purpose is to move hot air

away from the top of the hive when the sun is pounding down in the

summer.

Below the roof comes the

"quilt" layer, which is actually a wooden box with burlap attached to

the bottom so it can hold straw, wood shavings, or leaves. The

organic matter acts as insulation and also soaks up moisture,

preventing the problem of condensed cold water dripping on the bees in

the winter. The beekeeper changes out the insulation layer every

year, or more often if it feels damp.

Below the roof comes the

"quilt" layer, which is actually a wooden box with burlap attached to

the bottom so it can hold straw, wood shavings, or leaves. The

organic matter acts as insulation and also soaks up moisture,

preventing the problem of condensed cold water dripping on the bees in

the winter. The beekeeper changes out the insulation layer every

year, or more often if it feels damp.

Next down comes another piece

of cloth that takes the place of the inner cover of the Langstroth

hive. The cloth is somewhat permeable to moisture-laden air, so

it allows damp to move upward into the quilt where it won't bother the

bees. The cloth can also be pried back partially to peek inside

the colony, a process that doesn't tend to jar the hive as much as

removing a wooden inner cover would.

Next down comes another piece

of cloth that takes the place of the inner cover of the Langstroth

hive. The cloth is somewhat permeable to moisture-laden air, so

it allows damp to move upward into the quilt where it won't bother the

bees. The cloth can also be pried back partially to peek inside

the colony, a process that doesn't tend to jar the hive as much as

removing a wooden inner cover would.

The Warre hive body

itself is considerably smaller than boxes in Langstroth hive, again for

the purpose of heat retention. The winter cluster fills more of a

Warre box than a Langstroth box, which makes it easier for the bees to

stay warm. Meanwhile, their honey stores are above the cluster

rather than to either side of them, so the bees can travel up to eat

(which is easier than sideways, around frames).

Speaking of frames, even

the top bar setup is part of the heat retention design. Warre

believed that frames make it harder for bees to heat the hive because

air flows up the gap  between the frame and the

walls. Without frames, the bees build their comb all the way to

the sides of the boxes, creating a more solid barrier to air movement.

between the frame and the

walls. Without frames, the bees build their comb all the way to

the sides of the boxes, creating a more solid barrier to air movement.

David Heaf's final

observation on the topic is that mesh floors are problematic because

they increase consumption of honey by 20% in the winter without (he

believes) cutting down on varroa numbers. Although some

beekeepers put a solid drawer under the mesh in the winter, that just

makes a spot for debris and microorganisms to accumulate where bees

can't reach and sanitize the hive.

The reason I'm spending

a whole post on talking about the heat-retentive design of the Warre

hive is because I think it would be possible to take a hybrid approach

without embracing the entirety of the Warre method. If you were

afraid of nadiring and really wanted to be able to check on your bees

at intervals, you still might get better results by changing over to a

Warre hive structure without using the entire set of management

techniques. Or you might simply add a Warre-type roof, quilt, and

cloth assemblage to the top of a Langstroth hive and see what

happens. I figure our eventual beekeeping system will probably be

a mish-mash of bits and pieces we like from many different beekeepers'

philosophies, so it's worth understanding how and why certain methods

work.

| This post is part of our Warre Hive lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

I assume that you thought of building a hive with a glass observation window? That way you could peer inside, but not disturb the temperature.

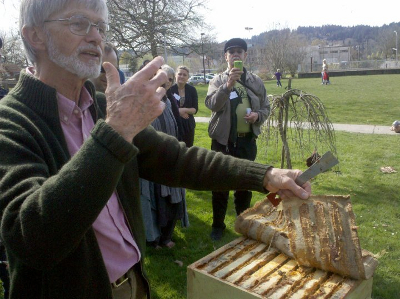

Anna, I was examining a Warre hive today at my local association's beginner's beekeeping class (I love that I can do this for very little money!) and conversing with the seasoned keepers about the merits and flaws of Warre, top bar, and Langstroth. I was stunned by how tiny a Warre hive is, but that drew me to it of course. However, there is a grea deal of trouble separating the comb from the box without harassing the bees or breaking off comb (which apparently angers them worse), because, as you mentioned, they glue straight to the walls of the box. Apparently the member with the most experience with a Warre hive had to take 2 hours carefully carving free the fragile comb and their tiny top bars to search all of the frames for a queen (which was worth it, since there was no queen to find and they were able to re-queen).

While I love the concept of a Warre, it seems to me that in trying to make things more comfortable for the bees, the process is making it harder on the keepers. I'm glad it works for Warre, and some others, but I think that—especially for beginners—it may be trouble.

Additionally, one of the keepers primarily uses top bar (which I was heavily leaning toward), and he toyed with a Warre this year and has come up with some really great ideas about taking some of the best parts of a Warre (like its attic) and building them into a top bar. I'm looking forward to seeing how it turns out for him. The top bar he brought for us to inspect was a beautiful thing and it's clear that if he can make the attic work, the moisture issues in a top bar hive would be perfectly solved. Too bad a top bar doesn't produce more honey! I think I'm more than willing to sacrifice a little honey for a healthy hive, though.