Fruit in colonial gardens

In

1648, the governor of Massachusetts traded 500 apple trees for

250 acres of land. I figure that means the trees were worth at

least $500 apiece in today's dollars. Can you imagine how scarce

and important fruit trees must have been in early New England to

command that kind of price?

In

1648, the governor of Massachusetts traded 500 apple trees for

250 acres of land. I figure that means the trees were worth at

least $500 apiece in today's dollars. Can you imagine how scarce

and important fruit trees must have been in early New England to

command that kind of price?

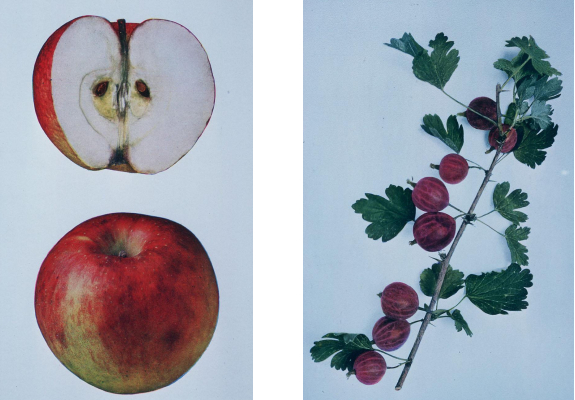

As nurseries began to

open up, fruit trees became a common component of

the New England garden. The most common were apples, pears,

peaches, and cherries, but all of the following woody fruits were

recorded in New England gardens before 1840: cornelian cherry, white

and black mulberries,

currants, highbush cranberry, fox and muscadine grapes, apricots,

barberries, gooseberries, nectarines, plums, quinces, walnuts,

chestnuts, and raspberries.

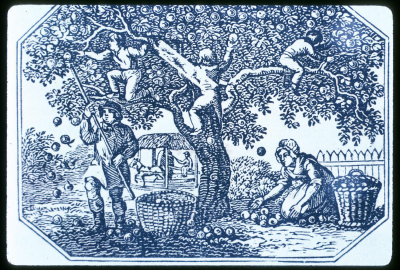

Entire orchards were

planted, but fruit trees were also tucked into

gardens wherever they might fit. Perhaps the colonists have

something to teach us about forest

gardening too?

| This post is part of our Early New England Gardens lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

yep went looking for money translation from then, this is the closest I could find.

Prices and goods available varied widely from colony to colony, and the relative prices of goods were very different from what they are today. For example, because of England’s economic policies, all but the coarsest cloth — what could be made at home — had to be imported from England. As a result, bedsheets were very expensive, and if you examine colonial probate inventories, you’ll find that relatively few people could afford them. Land, by comparison, was cheap — more people could more easily afford land than they can today. It was also cheaper to build a house than it is today, since someone could simply cut down trees on his property or on unclaimed land, fashion lumber from them, and build a crude cabin with the help of a few neighbors.

The best way to evaluate what various goods were worth in “today’s money” is to examine probate inventories and bills of sale and use your own judgment. Compare the listed values of household goods, tools, slaves, and land; look at what everyone owned as opposed to what very few people owned. For example, in Valentine Bird’s probate inventory from 1680, we can see that “fine Holland sheets” were worth 50 shillings (£2:10:00) a pair — a pair being the top and bottom sheet; pillowcases were extra. A bed stead, meanwhile — the frame of the bed itself — cost only 8 shillings (£0:08:00)! Wood could be cut and and made into a bed in North Carolina, but fine sheets had to be imported at great expense — more than six times the cost of a bed.