Four ways to propagate woody plants

The Reference

Manual of Woody Plant Propagation begins with a discussion of

the four main methods you can use to take one plant and make

several. Each has its pros and cons, so it's worth taking a look

at all four before you decide which one(s) you want to use.

The Reference

Manual of Woody Plant Propagation begins with a discussion of

the four main methods you can use to take one plant and make

several. Each has its pros and cons, so it's worth taking a look

at all four before you decide which one(s) you want to use.

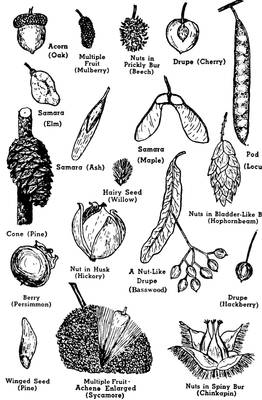

For those of us used to

working with annuals, the most obvious form of propagation is to grow

plants from seed. The great thing about growing from seed is that

you end up with lots of new plants quickly and at a low cost. The

bad part is that every seedling is going to be a little different ---

very few woody plants have been line bred to the point where you can

save the seeds and end up with similar offspring the way you could with

an heirloom tomato. On the homestead, it's most handy to grow

woody plants from seed if you're working with species likely to breed

true (often self-pollinators like peaches), if there aren't many named

varieties (often the case for nuts, Nanking cherries, etc.), or if

you're just producing rootstocks to graft onto.

Which brings us to

grafting. As I explained in my lunchtime series about The

Grafter's Handbook,

grafting is a method of producing a clone of a variety you like, such

as a winesap apple. The major advantage of grafting is that it's

fast and dependable once you know what you're doing. The downside

is that you either have to buy or grow rootstocks (produced from seed

or by rooting cuttings), so grafting tends to be more expensive than

most other types of propagation.

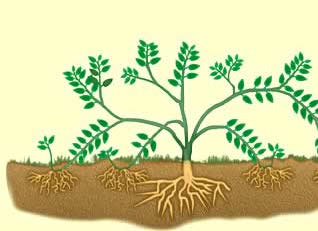

Rooting is the poor man's

grafting. Once again, you end up with an exact clone of the plant

you like, but the process can cost absolutely nothing in many

cases. The Reference

of Woody Plant Propagation notes that it's cheaper to root

cuttings than to graft if your rooting success rate is at least 50%,

but on the downside, rooting generally takes a year or two longer to

produce fruit than if you grafted. I'll spend most of the rest of

this week's lunchtime series writing about rooting cuttings, but it's

also worth noting that many plants self-root automatically at the tips

of their branches.

Rooting is the poor man's

grafting. Once again, you end up with an exact clone of the plant

you like, but the process can cost absolutely nothing in many

cases. The Reference

of Woody Plant Propagation notes that it's cheaper to root

cuttings than to graft if your rooting success rate is at least 50%,

but on the downside, rooting generally takes a year or two longer to

produce fruit than if you grafted. I'll spend most of the rest of

this week's lunchtime series writing about rooting cuttings, but it's

also worth noting that many plants self-root automatically at the tips

of their branches.

The final method of

propagation --- tissue culture --- requires lots of lab equipment, so I

won't write about it here. The benefit of tissue culture is that

you can produce lots of clones very quickly, but there is a large price

tag attached.

| This post is part of our Reference Manual of Woody Plant Propagation

lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

Cloned plants would be vulnerable to the same pests and diseases, wouldn't they?

IIRC, this is a big problem with the current cultivars of seedless bananas; most of which are supposed to be clones of a single plant.