Endophytes help plants, harm animals

Most pasture farmers know

that endophytes are hard on animals, causing problems ranging from

pregnancy issues to staggers. Other ailments include slow growth,

hoof gangrene, and a hard time handling hot weather. But what are

endophytes?

Most pasture farmers know

that endophytes are hard on animals, causing problems ranging from

pregnancy issues to staggers. Other ailments include slow growth,

hoof gangrene, and a hard time handling hot weather. But what are

endophytes?

If you're a ryegrass or

fescue plant, endophytes are the coolest thing since sliced

bread. These symbiotic fungi --- Neotyphodium coenophialum in fescue and Neotyphodium

lolii in ryegrass

--- spend their whole lives inside a single grass plant, eating sugars

the plant hands over willingly. In exchange, the endophytes

produce alkaloids that deter insects and keep grazers like deer, sheep,

cattle, and horses from gorging too much on the grass.

When

scientists discovered the dangers posed by endophytes, they got to work

breeding endophyte-free grasses. However, they soon learned that

plants share their sugars with endophytes for a reason --- without the

endophytes, fescue and ryegrass tend to die out  quickly. (The paired

photos show an ailing stand of endophyte-free fescue on the left and a

thriving stand of endophyte-infected fescue on the right.) Now

scientists have changed their tactics and are trying to breed

endophytes that produce the alkaloids that keep bugs at bay (peramine)

without making ergovaline (which is the most problematic alkaloid for

livestock). If you haven't planted a special (read: expensive)

strain,

though, chances are your ryegrass and fescue are infested with the

common endophyte varieties.

quickly. (The paired

photos show an ailing stand of endophyte-free fescue on the left and a

thriving stand of endophyte-infected fescue on the right.) Now

scientists have changed their tactics and are trying to breed

endophytes that produce the alkaloids that keep bugs at bay (peramine)

without making ergovaline (which is the most problematic alkaloid for

livestock). If you haven't planted a special (read: expensive)

strain,

though, chances are your ryegrass and fescue are infested with the

common endophyte varieties.

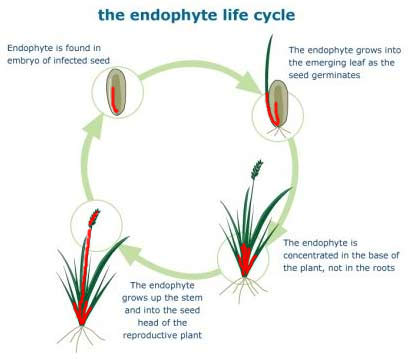

Luckily, you can work

around endophytes in many situations, giving your grasses the boost

they need to thrive without hurting your livestock's health. The

trick is to understand the life cycle of an endophyte-infected grass.

The red lines in this diagram

show the general location of endophytes within a plant. (No, you

can't actually see anything with your naked eye.) The fungus

comes along for the ride when a seed drops off the parent plant,

spreads up into the lower portion of the leaves, and then heads up the

flower stalk to infect new seeds.

The red lines in this diagram

show the general location of endophytes within a plant. (No, you

can't actually see anything with your naked eye.) The fungus

comes along for the ride when a seed drops off the parent plant,

spreads up into the lower portion of the leaves, and then heads up the

flower stalk to infect new seeds.

As a pasture maintainer,

this life cycle tells you how to ensure your livestock don't munch on

too much of the problematic fungus. If you don't overgraze your

pastures and do graze often enough that the grasses don't want to go to

seed, your livestock probably won't get enough endophyte into their

systems to cause problems. No wonder endophyte-related illnesses

tend to show up in summer or fall, when our cool season grasses are

declining and we're forced to graze them down to nubbins.

My final

endophyte-related question was --- do endophytes harm chickens? A

quick search of the internet doesn't turn up much definitive

information. Chickens fed on a diet of endophyte-infected fescue

seeds did worse than those fed on a diet of endophyte-free fescue

seeds, but other sources suggest that, in the wild, chickens don't eat

enough grass to get sick. Fescue is generally too tough for

chickens to digest, but I did plant some annual

ryegrass in one of

our pastures since these tender leaves are supposed to be much more

palatable to non-ruminants. I'll make sure to treat the ryegrass

carefully and will let you know if I see any problems.

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

To what species do the plant cells and endophytic hyphae belong? Both Neotyphodium lolii and Neotyphodium coenophialum were mentioned. Were the cells annual or perennial ryegrass?

Thank you!