Cutting scionwood for a cleft graft

My first step after

deciding to topwork my two pear trees was to

find scionwood. I wanted to try specific varieties, so I ordered

some from Burnt Ridge Nursery, but you can also get scionwood from a

neighbor's tree if you know you like the taste and habits of their

fruit varieties. The best scionwood is about the thickness of a

pencil, is from last year's growth, doesn't contain flower buds, and

does contain two or three leaf buds. Longer scionwood is fine,

and gives you some wiggle room in case you make the first cut wrong ---

you can always shorten it to three buds later.

Although you should wait

to prepare your official scionwood until it's ready to go into place

(Thursday's post), raw beginners like me should practice first so we

become relatively adept at our cuts before working on the limited

scionwood. Grafting cuts should always be as straight as

possible, which means you should try to make them with a single cut

rather than "whittling" --- fixing incorrect cuts by making two or

three more cuts. The photo above shows some of my early practice

strokes --- you can see the curves that result from whittling.

Luckily for me, I had plenty

of wood to practice on. I planned to cut the whole top off my two

small pear trees and insert new scionwood in a cleft graft, so nearly

all of the twigs on the tree were fair game.

Luckily for me, I had plenty

of wood to practice on. I planned to cut the whole top off my two

small pear trees and insert new scionwood in a cleft graft, so nearly

all of the twigs on the tree were fair game.

I actually practiced on

a little walnut tree I needed to cut out of the yard first, but soon

discovered that different trees' twigs behave very differently.

If you're going to graft a pear tree, practice on some pear twigs; if

you're going to graft an apple, practice on an apple.

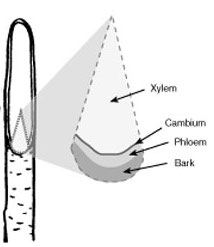

So, what did I want my cuts

to look like? The easiest grafting cut is for a whip graft, where

you attach two twigs of the same diameter together. That kind of

graft simply requires a long straight cut so that the scionwood comes

to a point, as is shown in the drawing to the left.

So, what did I want my cuts

to look like? The easiest grafting cut is for a whip graft, where

you attach two twigs of the same diameter together. That kind of

graft simply requires a long straight cut so that the scionwood comes

to a point, as is shown in the drawing to the left.

For my cleft graft, I

needed to make a slightly more complex cut. I wanted to turn the

base of the scionwood into a wedge by making two angled cuts. To

complicate matters further, the wedge needed to be pie-shaped in

cross-section, with the side containing the lowest bud larger than the

other side of the twig. This sounds complex, but wasn't really

that hard to cut, once I wrapped my head around the goal.

Time to start

cutting! Grafting teachers always warn you to make sure the buds

point up, which seems ludicrously obvious to me, but maybe folks not as

tuned into plants need to be told that? Once you turn your

scionwood right side up, decide which spot will be the bottom of your

cut. I learned the hard way that you won't get a nice, straight

cut if you try to go through a node (where the buds are), so I cut my

scionwood off just above a bud.

It's best if you also

choose a spot where the internode (length of wood between two buds) is

relatively long since your angled cut should be at least an inch long,

preferably 1.5 to 2 inches. Longer cuts give your scionwood a

better chance of merging with the growing tissue of the tree it's being

grafted onto.

relatively long since your angled cut should be at least an inch long,

preferably 1.5 to 2 inches. Longer cuts give your scionwood a

better chance of merging with the growing tissue of the tree it's being

grafted onto.

Now find a good sharp

knife (I used our chicken butchering knife, recently sharpened) and

make your first test cut. Remember, you don't want to whittle, so

you should create the wedge shape at the bottom of your piece of

scionwood in two quick cuts. Once you try it a time or two,

you'll see why I told you to practice on a twig you didn't care about.

After making Mark stand

around in the sun and watch me whittle for about fifteen minutes, I

started to feel like my cuts were going more smoothly. Time

to move on to the next step --- preparing the tree to be grafted

onto. Stay tuned for tomorrow's post to learn tips in that

department.

After making Mark stand

around in the sun and watch me whittle for about fifteen minutes, I

started to feel like my cuts were going more smoothly. Time

to move on to the next step --- preparing the tree to be grafted

onto. Stay tuned for tomorrow's post to learn tips in that

department.

| This post is part of our Grafting Experiment lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

To be sure, buds up is ludicrously obvious, as buds down is obviously ludicrous.

And I have two black thumbs.

} j {