Brunetti on plant secondary metabolites

Jerry

Brunetti's lecture was titled "Achieving the holy grail of crop health:

Plant secondary metabolites". That probably sounds a bit

yawn-worthy if you're not a plant geek, but it turns out his talk was

my favorite from the conference so far. (In the interest of full

disclosure, though --- I am a plant geek.)

Jerry

Brunetti's lecture was titled "Achieving the holy grail of crop health:

Plant secondary metabolites". That probably sounds a bit

yawn-worthy if you're not a plant geek, but it turns out his talk was

my favorite from the conference so far. (In the interest of full

disclosure, though --- I am a plant geek.)

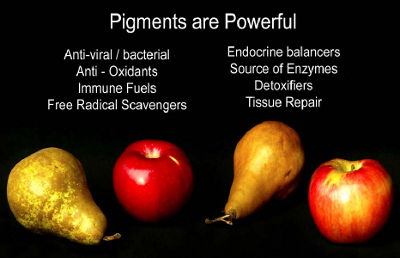

So, what are plant

secondary metabolites, and why should we care about them?

The term refers to every chemical that makes up a plant except for the

big three --- carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. The scent of a

flower, the spiciness of a pepper, and the color of an apple are all

plant secondary metabolites. So are the chemicals released by

caterpillar-nibbled trees to warn the next tree down the lane to build

anti-caterpillar chemicals proactively, as well as the attractants

emitted by plant roots to tempt soil microorganisms to stop by.

The

chemicals that give plants intriguing tastes are all plant secondary

metabolites, and so are compounds like lycopene and salicylic acid,

which help prevent prostate cancer and heart attacks,

respectively. Brunetti explains that there are tens of thousands

of plant

secondary compounds produced for reasons that include attracting

pollinators and seed dispersers, defending the plant from ultraviolet

light and herbivores, and communicating with plants, insects, and soil

microorganisms.

The fact that so many of the

compounds impact our health (positively or

negatively) is merely a side effect from the plants' point of

view. Plants create secondary metabolites because the chemicals

make their lives easier --- since a tree can't run away from problems

or travel to find true love, it has to repel the one and attract the

other. (Sounds like my life on the farm....)

The fact that so many of the

compounds impact our health (positively or

negatively) is merely a side effect from the plants' point of

view. Plants create secondary metabolites because the chemicals

make their lives easier --- since a tree can't run away from problems

or travel to find true love, it has to repel the one and attract the

other. (Sounds like my life on the farm....)

But production of these

chemicals comes at a cost. Plants

constantly have to weigh the pros and cons of using their limited

energy to make carbohydrates, fats, and proteins --- allowing them to

grow and reproduce --- or to make secondary metabolites of various

sorts. In the wild, plants usually create a bit of both, focusing

on secondary metabolites more when they're subtly stressed, but not so

injured that they're wilting away.

In an agricultural

setting, the stakes are different. Farmers try to protect

our crops from all problems, which means the plants have little reason

to produce secondary metabolites and can simply grow big and

tall. While that means more pounds of vegetables on our plates,

the lower concentrations of secondary metabolites make the food less

tasty and nutritious. Maybe that's why vineyard keepers believe

the best wine comes from grapes that had to struggle a little?

In

addition to lacking the incentive to make secondary metabolites, some

cultivated plants also lack the ability. Micronutrients like boron, copper,

aluminum,

manganese, and zinc are all essential for the production of secondary

metabolites but chemical farmers figure crops can get by without

micronutrients as long as they're well dosed up with some

10-10-10. I guess that's why I

was able to taste a micronutrient

deficiency in my strawberries --- the lack of minerals

relates

directly to the secondary metabolites that we

In

addition to lacking the incentive to make secondary metabolites, some

cultivated plants also lack the ability. Micronutrients like boron, copper,

aluminum,

manganese, and zinc are all essential for the production of secondary

metabolites but chemical farmers figure crops can get by without

micronutrients as long as they're well dosed up with some

10-10-10. I guess that's why I

was able to taste a micronutrient

deficiency in my strawberries --- the lack of minerals

relates

directly to the secondary metabolites that we  perceive as flavor.

perceive as flavor.

So how do you grow

the most delicious and nutritious fruits and

vegetables possible? Simply feed the soil well-rounded organic

amendments like compost and mulch, and don't wipe out every last

disease and pest. You'll get lower yields, but what you do grow

will be richer in flavor and nutrition.

Learn to grow healthy plants from the ground up in Weekend Homesteader.

| This post is part of our ACRES conference lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

Doc --- Hmm, I can't say I agree with you. True, it's tough to do really scientifically rigorous studies on topics of human health for ethical reasons, but that doesn't mean we should ignore all of our stabs in the dark. Does that mean you also don't believe that cigarette smoke increases our risk of lung cancer because we, presumably, haven't stuck test subjects in a room for several years with measured levels of cigarette smoke vs. test subjects with no cigarette smoke? Just because we instead asked them how many packs a day they smoked and relied on their memories?

(It's also a bit unfair to compare the effects of penicillin used to cure a serious illness --- presumably you need a lot of it in one dose --- with compounds that boost your health in small amounts over extended periods of time.)

If you are looking at some type of measurable performance with regards to plant health and micronutrients (or some other amendment like foliar sprays) you should be able to do a BRIX test before and after the application. If the plant responds well, the BRIX level should increase. If not, then that particular amendment isn't currently beneficial to that particular plant. I don't know for sure, but I would expect that secondary metabolites would contribute to the overall BRIX measurement.

Personally I still see a few challenges with this approach. I don't have a refractometer available to see how practical this testing actually is. In addition, I don't have a lot of the same type of plant where it makes sense to apply a small dose of one amendment to one plant before I decide to apply it to the rest of that variety. Finally, I think that soil testing for trace elements is probably more exact to determine major deficiencies... then again it is very expensive and takes a long time to get the results when being sent to a distant lab. I'm sure that testing the soil every few years is worth the expense, but going back to the basics of adding compost and aged manure frequently will probably address the majority of problems.

David --- Excellent point about having to have a lot of the same kind of plant to use brix most effectively. What intrigued me was the idea of monitoring a planting over time to see if the brix begins to decline, which would give me an idea I might need to topdress to ward off disease. The nice thing about brix vs. soil testing is that you can test the brix easily at home, so you can do it every day if you want to.

I'm still not totally sold, but I probably will eventually have to get one of those meters and experiment.

Ha! I get so tired of being told that my experience in life is not quantifiable nor explainable. It's in your head. Nope, it's in the strawberry, or not as real world experience tells a different tale.

I grew up eating from about an acre garden, it was our main food source, then we moved into town and ate from the grocery store. I hated it. Said the milk tasted like colored water and bad water at that. Etc. etc. I was a pain to my parents. It's always nice to learn that there might be some science to be explored that might help me understand the why and wherefore of the changing taste.

(PS Many thanks to your geeky brother for the email replies button, for someone like me who is very behind in her garden blog reading... it's a help!)

c --- Isn't it crazy how insipid grocery store food tastes after you've eaten the real thing?

I've passed your thanks on to Joey! That should oil the gears for my next webpage request.

Happy to help with the "leverage positive to encourage help from tech guy" side of things.

And yes, snobs call it "having a palate" sadly the world used to eat like that daily.