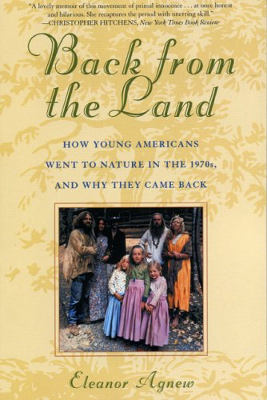

Back from the Land

Although

I stole my parents' dream of going back to the land, I don't want

to share the end of their story --- fleeing to town and selling the

farm. So when I heared about Eleanor Agnew's Back

from the Land: How Young Americans Went to Nature in the 1970s, and Why

They Came Back, I

had to check it out.

Although

I stole my parents' dream of going back to the land, I don't want

to share the end of their story --- fleeing to town and selling the

farm. So when I heared about Eleanor Agnew's Back

from the Land: How Young Americans Went to Nature in the 1970s, and Why

They Came Back, I

had to check it out.

The reviews for Agnew's

book aren't all glowing, and I can see why

not. She interviews a variety of ex-back-to-the-landers, some of

whom seem to have enjoyed the experience, but Agnew herself has nearly

nothing good to say about her four-year stint on a farm in Maine.

Her book includes phrases like "Building a house from scratch is a

labor from hell," and, although she doesn't use these exact words, I

can tell she thinks current homesteaders and adherents to voluntary

simplicity are naive. However, it's worth reading a more

pessimistic view of the movement in the interest of preventing history

from repeating itself, and the book is well written and easy to read if

you don't give yourself a tension stomachache taking it all personally

the way I did.

Who

they were

As Agnew sees it, most of the

four to five million back-to-the-landers

who existed by the end of the 1970s were young, white, middle class,

and educated. Reading between the lines, it sounds like they were

also philosophers who envisioned genteel poverty on the land as

requiring little work and lots of fun.

As Agnew sees it, most of the

four to five million back-to-the-landers

who existed by the end of the 1970s were young, white, middle class,

and educated. Reading between the lines, it sounds like they were

also philosophers who envisioned genteel poverty on the land as

requiring little work and lots of fun.

Their reasons for going

back to the land were similar to those of

today's homesteaders in many ways, but there were striking

differences. Many 1970s back-to-the-landers joined up because

they liked the idea of being part of something larger than themselves,

and many more ended up in intentional communities or communes than do

today. The 1970s back-to-the-landers also seem to have been more

dogmatic and less willing to compromise --- for example, Agnew seems to

have thought that everything from hooking up to the electric grid to

getting a white-collar job equated to selling out --- and

they also were more isolated and had fewer job opportunities in the

days before the internet.

Why

they left

Differences between the

two movements aside, I think modern

homesteaders should take note of the reasons 1970s back-to-the-landers

fled to cities. For some, the issue was a simple dislike of the

reality of homesteading, whether that was cold weather or slaughtering

meat animals. Chores like carrying water that had at first seemed

so romantic turned into inconveniences, and the hard work left little

time for the creative pursuits many had fled the rat race to

puruse. Agnew (and many others) eventually concluded "if it's

simplicity I want, it's simpler to play along with the system."

Another common theme was being torn down by

relentless poverty.

Sources like the Nearings (who actually had an annual

writing and

speaking income that would translate to $17,000 to $55,000 in today's

dollars) caused these young people to drastically underestimate the

amount of capital required to keep a farm going, so they thought they'd

be able to make a good living selling fruits and vegetables or arts and

crafts (something I preach against in Microbusiness

Independence).

When that didn't pan out, they tried to get traditional jobs, but rural

areas had few opportunities that paid above minimum wage, so the

back-to-the-landers spent

more and more time off their farms trying to make a living.

Another common theme was being torn down by

relentless poverty.

Sources like the Nearings (who actually had an annual

writing and

speaking income that would translate to $17,000 to $55,000 in today's

dollars) caused these young people to drastically underestimate the

amount of capital required to keep a farm going, so they thought they'd

be able to make a good living selling fruits and vegetables or arts and

crafts (something I preach against in Microbusiness

Independence).

When that didn't pan out, they tried to get traditional jobs, but rural

areas had few opportunities that paid above minimum wage, so the

back-to-the-landers spent

more and more time off their farms trying to make a living.

A reason for failure

that seems just as prevalent in today's

homesteading community is relationship ills. Often one partner

was more interested in the homesteading gig than the other, and they

never learned to compromise their work ethics and coordinate their

dreams. The period was also marked by a belief in the importance

of individual fulfillment, and that, along with a lack of personal

space, stress over money, and exhaustion from hard work, caused many

couples to fall apart. When a couple split, at least one of them

inevitably left the land.

Lessons

learned

Although I found Back

from the Land

to be a handy cautionary tale, I think that most of us have a better

chance of success than our parents did, especially if we're able to

compromise. Now more of us believe we can choose to be part of

society on our

own terms without losing sight of the goal we're striving toward.

We can take advantage of the power of the internet to make a living,

can hire local craftspeople to help us improve our living conditions,

and can still enjoy the benefits of homegrown food and a debt-free

existence.

Although I found Back

from the Land

to be a handy cautionary tale, I think that most of us have a better

chance of success than our parents did, especially if we're able to

compromise. Now more of us believe we can choose to be part of

society on our

own terms without losing sight of the goal we're striving toward.

We can take advantage of the power of the internet to make a living,

can hire local craftspeople to help us improve our living conditions,

and can still enjoy the benefits of homegrown food and a debt-free

existence.

Meanwhile (and as

usual), I think there's also another book waiting to

be written about the flip side of the coin. I know of at least

one couple in our county who went back to the land in the 1970s and

still lives the dream today, so there must be other examples out

there. If you're one of those success stories, I hope you'll

comment with your tips for the next generation.

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

I was really excited to read the book, just because I knew (or I hoped) it would rub me the wrong way. Remember when Joel Salatin encouraged us to read things that get our blood pressure up?

I ended up enjoying the chance to look at the more difficult side of homesteading. In my experience, a lot of people go into homesteading (or communal living) with a utopian view of how it will straighten out their lives and make everything better. I can understand why Agnew felt compelled to write about her failed attempt. Too often, the failures are simply too difficult and embarrassing to write about, so they don't come to light very often.

Granted, I don't think the failures on the early homesteads were exclusive to homesteaders, but reflected the larger conflicts that society was experiencing-- a new awareness of environmental issues, globalization, etc. Also, like you pointed out, many of the failures were personal and not much different than the personal issues that lead to divorce, bankruptcy, etc. in mainstream society today.

I was somewhat comforted by the tearing down of the myth of the perfect life of a homesteader. The good thing about it, from my perspective, is that she makes the point that changing your lifestyle isn't necessarily going to fix everything.

The book did make me a bit gloomy though. Especially the chapter on poverty. I suppose if I read this in the beginning instead of after a few years in, it would have been very discouraging.

You're right: most of them were pseudo-hippies living in the Fantasyland of youthful liberalism. They were, for the most part, coddled suburbanites, partially educated at their fathers' expense, never having done an honest day's labor in their whole lives. Once introduced to reality, they quickly learned the value of conservative thinking in confronting the problems of the real world. Many, if not most, were part of a "commune" which involved not only the rigors of hard work, but also the problems of getting along with others. It would seem to me that a spirit of rugged individualism, not social dependence, is the trait needed most to successfuoly live the self-reliant lifestyle.

Even today, I compare many of those who procalim to be "living green" with the 9 yr old kids who try the great adventure of camping out in the tent in the backyard. They're imagining the wild, dangerous exposure, but know full well they can retreat to the safety of the house if a thunderstorm pops up.

During the time of the 1970's, much had happened in our society. We were young teenagers during this time, and the generation right in-front of us had that 'persistent - vile', to do it 'their way.' often, during those days those of us who were still being raised traditionally, (and missed the time of being in college during the time of Vietnam,) did not fully embrace those things. We continued to go on with our educations, and some of us lived in rural areas, knowing that the only way to have a better start was to progress more to the urban area. The '70's' group that did alot of this type of thing, also were not 'conditioned' much in knowing how 'physically challenging' that life could be in working the land and living this way. Much like the types' that were over there in the Asia part of the world, revolting, protesting, and rebelling. Well, it was such a turn of behavior, that some of what was stated early in the posts on this: was surely destined to fail. Living on a farm, ruraly, is hard work and it's a way of life. Many did not have clear maturity in some of these culture movements, and went in 'revolt' to mainstream society to prove something. And, so be it. However, being older now, currently my husband and I are moving to rural; still working the end of our careers in the urban area- building our world for retirement. We've already owned homes in other states, put away for rainy days, raised the children. And, with the maturity, challenges in life we have learned; as mature adults we hope to revive and sustain a 140 yr. old farmstead that has been in good shape. 'The Hippie culture', was all about free love too. If your going to survive in the 'wild', you must have personal and relationship committment totally and both have to agree what you really want in life and have a plan along the way as to how to accomplish it. Just thoughts to this, have not read the book but seems very interesting. Have cousins of that age group, and remember clearly as a pre-teen how that culture was, very vividly.