Agriculture led to world domination

Nearly as soon as people in the Fertile

Crescent started to farm, they embarked on world domination. If

you'll recall, I argued that overpopulation

lay at the root of the original farmers turning to agriculture, but agriculture only

exacerbated the overpopulation problem. Not only did sedentism

allow early farmers to double their birth rate, children suddenly

became useful as farm hands and old folks became fonts of wisdom rather

than a drain on the tribe. Ill

health wasn't enough

to counteract this trend toward increased population, and those new

people had to go somewhere.

Nearly as soon as people in the Fertile

Crescent started to farm, they embarked on world domination. If

you'll recall, I argued that overpopulation

lay at the root of the original farmers turning to agriculture, but agriculture only

exacerbated the overpopulation problem. Not only did sedentism

allow early farmers to double their birth rate, children suddenly

became useful as farm hands and old folks became fonts of wisdom rather

than a drain on the tribe. Ill

health wasn't enough

to counteract this trend toward increased population, and those new

people had to go somewhere.

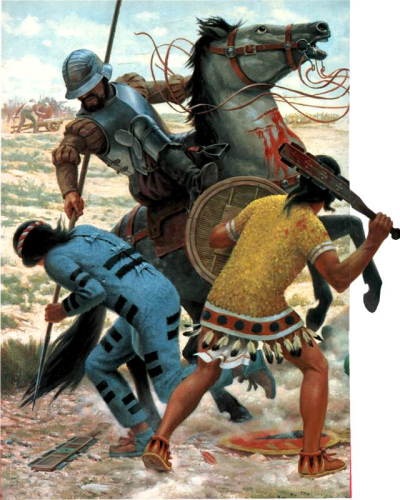

From the moment

agriculture began to spread beyond the Fertile Crescent, it took a mere

300 years for farming to displace hunting and gathering throughout

Europe. I'd like to  believe that the contemporaneous

hunter-gatherers (like those pictured above) saw how much fun it was to

grow wheat and jumped on the bandwagon, but archaeological evidence

suggests a different story. Archaeologists can tell the

difference between the artifacts of the hunter-gatherers and farmers of

the time, and there is absolutely no evidence of cultural interchange

between the two groups...except for spear points. By mapping the

offshoots of their language --- known to linguists as Indo-European

languages --- we can see that these people not only took over Europe,

but also spread out across southern Asia.

believe that the contemporaneous

hunter-gatherers (like those pictured above) saw how much fun it was to

grow wheat and jumped on the bandwagon, but archaeological evidence

suggests a different story. Archaeologists can tell the

difference between the artifacts of the hunter-gatherers and farmers of

the time, and there is absolutely no evidence of cultural interchange

between the two groups...except for spear points. By mapping the

offshoots of their language --- known to linguists as Indo-European

languages --- we can see that these people not only took over Europe,

but also spread out across southern Asia.

As Jared Diamond

eloquently argues in Guns,

Germs, and Steel,

you can continue to trace the spread of the first farmers to the

domination of the Americas. Europeans' early domestication of

plants and animals turned us into war machines --- we had

enough spare  food to feed full-time

soldiers and the leisure to invent

technologies of war like swords, guns, armor, and far-ranging

ships. Farming also led to the ability to write, and

effective communication was a big factor in our ability to win battles

against stronger foes.

food to feed full-time

soldiers and the leisure to invent

technologies of war like swords, guns, armor, and far-ranging

ships. Farming also led to the ability to write, and

effective communication was a big factor in our ability to win battles

against stronger foes.

Domesticated animals

were also essential in the European march toward

world domination. Horses were important because foot soldiers

can't stand long against a warrior on horseback, but the real reason we

devastated the native people of North, South, and Central America was

disease. Many experts believe that by the time Europeans returned

to the Americas with conquest in mind, smallpox and other diseases

from earlier contact had

already wiped out around 95% of the native population. Europeans

had evolved a partial immunity to the deadly disease

since we'd had to face smallpox ever since we domesticated its original

host --- cattle. In contrast, Native Americans had only

domesticated the

turkey and the dog, so they had no similarly deadly diseases to rebuff

us

with.

In essence,

overpopulation gave us the impetus to dominate the world and

agriculture gave us the means. Clearly, wheat has a lot to answer

for.

This post is part of our History of Agriculture lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

I wonder if this is the root cause, or if it was competition for resources that caused it? In the stone age the population was small and competition for resources presumably less.

Isn't that a relatively recent development? The first full-time soldiers on a large scale I can think of out of hand are the ancient Spartans. Most other Greek city-states maintained citizen armies. And there were the Roman legions from the late Republican era onward. But those were not the norm by any means. Few nations could afford large standing armies. At least into the middle ages there were lots of part-time farmers/citizens/soldiers.

Not by definition. In the Napoleonic wars infantry regiments "formed in square" were almost invulnerable to cavalry. It seems horses are not too keen to charge into rows of bajonets (or pikes).

But not just those. At least one one occasion the black death decimated about 30% of the European population. And there were other epicdemics too.

So it was the explorers that unknowingly did them in? Couldn't it have happened the other way around just as easily? A couple of sailors bringing back an unknown disease from the New World would have caused havoc in Europe.

One could also argue that this is just evolution (of societies) in action.

I think you should read Jared Diamond's book --- he fleshes all of this out in much greater depth. I was keeping things simple in my post, so I didn't go into all of the specifics. Here are some specific answers to your points (but read the book for many, many more!):

Competition for resources resulted directly from our domestication of plants and animals --- as I noted in early posts, it was the advent of agriculture that allowed our population to explode. I think that you're not looking at the bigger picture in a lot of your other points too (for example, how recent standing armies are.) Jared Diamond's point is that domesticating the first grain set us on a trajectory that led to standing armies, not that the early farmers immediately had standing armies.

As for your other points --- it's one thing to learn to stand against cavalry when you've seen cavalry in action and had time to get used to it, take those lessons home, and ponder a way to work around the cavalry's advantages. It's another thing to be faced with men on horseback when you'd never considered mounted soldiers and hadn't had time to devise strategies against it.

About plagues --- I was using smallpox as an example. Jared Diamond walks you through how all of the other epidemic diseases are also related to our domesticated animals, why we had to reach a certain population size before the microorganisms that produce epidemics could survive (rather than wiping themselves out when they wiped out their hosts), and why --- for those reasons (lower population and less time as an agricultural society) --- the Americas didn't have similar epidemic diseases to send back with the European explorers and wipe out Europe.

It's on my list, like many others. I'm still not finished with Roger Penrose's Road to Reality nor Feynman's Lectures on Physics. And then I'm learning the Lua and Python programming languages. And I recently saw Stephen Wolfram's "A new kind of science" mentioned, which looked very interesting. Sigh.

I think I could read for years on end and still not be bored. Maybe I should have become a librarian instead of an engineer.

Of course these days there is also wikipedia. I used to think that my parents' encyclopedia was the biggest time sink I ever found. Little did I know...

Roland --- I totally know what you mean. Reading is probably my biggest time sink, and my book list is always growing longer, not shorter....

Daddy --- Didn't you notice my post about harvest catch-all soup? That's clear evidence that you're already a font of wisdom.