archives for 05/2019

I wrangled a tour of a 56-year-old garden this week --- such a treat!

Shown here is bird netting atop the berry patch, which easily slides

into place each season due to applesauce jugs on top of the posts.

Voles are a major issue in this good soil, which makes growing sweet

potatoes a struggle. This gardener's solution? She drills lots of small

holes in the bottom of big pots, sinks them in the ground, fills them

with compost, then adds the sets.

Voles can't get in through the bottom or sides and the raised lip

prevents them from running straight in the top. The result is tubers

without nibbles --- a relief.

My tour guide also developed her own version of quick hoops, these even

quicker than mine since they're one structural piece and can be simply

lifted off and set aside. For ultra-early tomatoes, she sets out a

couple of plants under her covers and mitigates the temperature further

with full jugs of water.

The next innovation is on the chicken side of the property. A welder

handy man made this two-part tractor easy to move with the addition of

modified bicycle wheels.

Meanwhile, a rolling wood bin keeps interior heating easy for older

arms and backs.

"So what was your favorite part? Did any of it give you garden envy?"

Mark asked when I got home.

The truth is, the only part of the tour that made me jealous was the

darling water garden beside her screened-in summer kitchen. Now that my

vegetable patch is smaller, maybe I have time for a little

extracurricular gardening?

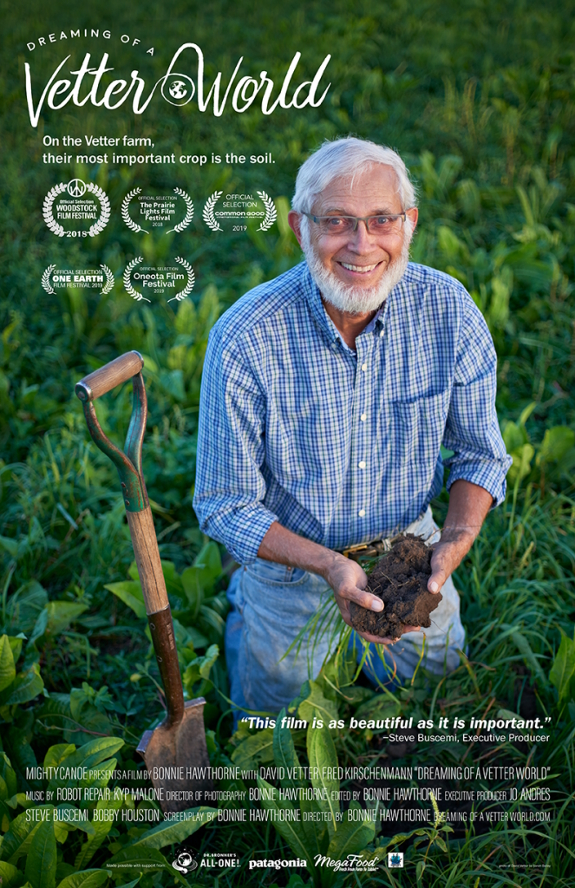

Mark and I recently attended a showing of Dreaming

of a Vetter World, with a

Q&A by Donald Vetter afterwards. If you've never heard of him,

Vetter

is a farmer right up Joel

Salatin's alley who uses long crop rotations combined with

rotational grazing to improve his soil. After decades of this

treatment, Vetter's

soil can soak in up to eight inches of rain per hour while his

neighbors' conventional fields start ponding and eroding after half an

inch in a similar time period.

So what does Vetter do to get such great results? He uses a nine-year

rotation, a third of which involves cows and pigs on pasture. We'll

start with that part --- the soil-building end of the spectrum. After

planting a grass/legume/forb mixture, he utilizes rotational grazing

for

three years, then he tills the rich greenery in.

Next comes the cash crops --- soybeans in year one, corn in year two,

then an Ethiopian land race of barley that his sister company (a

small-scale, organic grain-processing operation) bags up to sell as

bird seed. After a winter of cover

cropping combined with fall and

winter grazing, it's back to soybeans for a year followed by a final

season of popcorn.

Using this rotation, Vetter has added no off-farm inputs for twenty

years and sees annual improvement of his soil. He doesn't even buy

animal feed --- the waste seeds from his

grainary supplement his livestock's dependency on grass. The result is

a beautiful permaculture system that runs smoothly...when combined with

a lot of hard work.

The second Rural

Action mushroom foray took to the woods amid pollen so severe my

black shirt turned gray and my eyes began couldn't quite decide whether

to itch or tear up. I don't even get allergies! I can't imagine how the

more susceptible felt.

Despite adverse

conditions, we collected over twenty species in three short hours.

While plucking fungi from the woods, many seemed very similar and I had

a sinking suspicion I was bagging the same species over and over. But

once we spread them out on the picnic table, differences became clear.

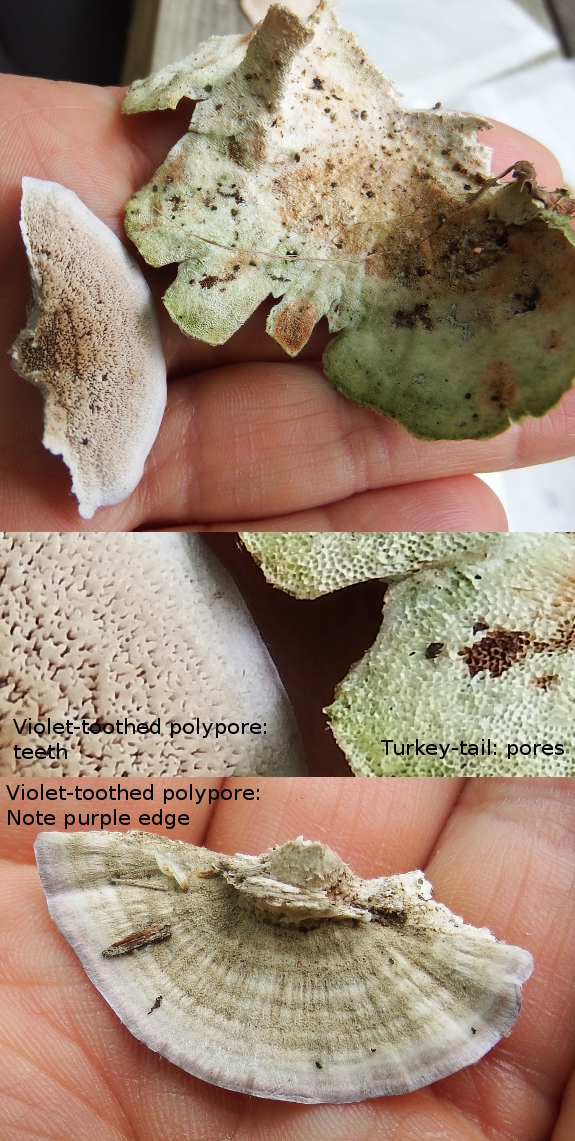

I'm going to focus on

the edibles again (although I've included a couple of inedible beauties

at the end of this post). First, another turkey-tail lookalike ---

violet-toothed polypore. My specimens of both species are old and

faded, but you can still see a little purple around the rim of the

polypore, the same color that is much more obvious underneath when the

fungi are fresh.

Lacking that giveaway,

you can distinguish violet-toothed polypores from turkey-tails by

peering at the undersides with a hand lens. As the name suggests, the

former has teeth while the latter boasts pores.

Next, a new-to-me

edible...that I never would have been brave enough to taste on my own.

Fawn mushroom (aka deer mushroom or Pluteus

cervinus) looks

an awful lot like another hundred or so species of brown, gilled

mushrooms. But if you peer closer, there are quite a few distinguishing

features.

First pay attention to

ecology --- fawn mushrooms grow on rotting wood. The gills are free, as

you can see in the top photo. And (at least when they get a little age

on them) the pink color underneath can be distinctive.

The real clincher,

though, is the aroma. Fawn mushrooms smell just like lightning bugs!

With that in mind, I was much more willing to cook them up to taste.

Flavor was good but not

amazing. Worth eating if you stumble across them, but not worth an

earmarked hunt.

A huge thank you to our

fearless leader who helped us separate the wheat from the chaff.

Although she didn't

appear to consult her library, Martha recommended the books above for

mushroom-hunting in southeast Ohio.

And now, eye candy!

Orange mycena...

...and my very favorite,

the split-gill mushroom.

I wonder what we'll find

next month?

We ate as much as we safely could of our first-year asparagus, have

gorged on lettuce and broccoli and kale, and now it's time for the

summer crops to begin. An ultra-early last frost means ultra-early

cucumber blooms. We should be adding these crunchy fruits to our salads

starting next week.

On a broccoli side note --- lowish nitrogen in the soil meant our heads

were smaller, but also faster, than usual. Interestingly, we've also

seen very few cabbageworms so far this spring. The moths have been

quite visible, but seem to prefer the flowering kale at the moment.

Could that be because of the lower-nitrogen plants?

Lower cabbageworm pressure means I've been able to leave the broccoli

plants in place for side shoots to form. (I usually pull them out after

first spring heading because otherwise they become a bad-bug nursery.)

The result? Possibly more total pounds of harvest than previously,

definitely spread over a longer time span. Despite not planning to

preserve excess food this year, I ended up packing away about a gallon

of broccoli in the freezer.

On a less pleasant note, our strawberry harvest looks like it will be

nonexistent. The berries started, a bird found them, I put bird netting

on top...and someone strong and vigorous (probably a squirrel) snuck

underneath and worked through the patch like a tornado. Every

strawberry of any size was removed, discards were strewn around the

garden, and Mark is now working on a berry enclosure to ensure this

won't happen again next year.

You win some and you lose some.

Speaking of winning --- wow, the manure! We're stocking up on

truckloads of this precious resource, in part because it disappeared

midsummer last year but also because the organic matter is full of wood

shavings and needs some rotting before it will be putting off much

nitrogen for our plants. Our worm bins quickly filled up, so now we're

starting a manure pile in the yard.

I'm also laying manure down on beds I don't plan to use in the next

several weeks, the time expanded from my initial plan of the next

month. Why? Because the tomatoes I set out into one-month-old manure

beds turned yellow and required chicken-manure topdressing to save

them. Luckily, they've now bounced back and are setting fruit.

In our second year, we're also starting to have a bit of time for

prettiness, like this grape trellis Mark made out of a cattle panel and

four fence posts.

A few weeks after erecting it, the 18-month-old grape vines are already

starting to fill their space. One plant has even begun to bloom!

What's coming up? This is a Prelude raspberry, a new-to-us variety

that's supposed to ripen before any other brambles in the patch. It

didn't bloom any earlier than my other varieties, but fruits are

starting to plump and blush. If the birds don't get them, we might have

a replacement to my demolished strawberries!

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.