archives for 03/2016

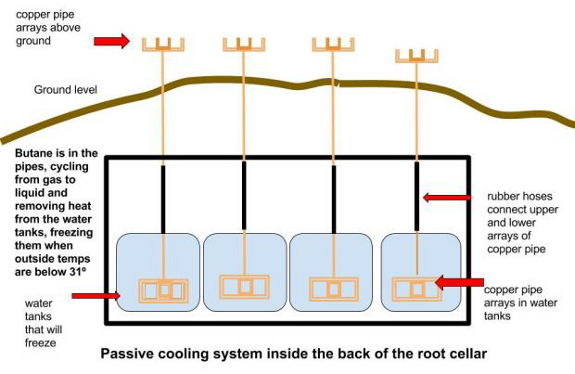

One of our readers

dropped me an email Monday to tell me about the root cellar she and her

husband want to build on their Vermont farm. The couple plan to give the

off-grid  cooler

extra oomph in the summer months by storing ice in the back, using

copper pipes full of butane to passively stockpile winter cold for

warm-weather use.

cooler

extra oomph in the summer months by storing ice in the back, using

copper pipes full of butane to passively stockpile winter cold for

warm-weather use.

In essence, they're hoping to combine the idea of an ice house with the

idea of a root cellar. If it works, they'll have achieved an

electricity-free, four-season temperature-modified area, allowing the

couple to feed themselves and their CSA customers all year

long...without the hard work of chipping blocks of ice out of the pond

every winter.

Will the ice-house/root-cellar combo go the distance? Donate to their Indiegogo campaign at the $15 level and

you'll get two years of temperature records in digital format to answer

that question. In the meantime, I'd be curious to hear your thoughts on

this innovative root cellar that's different from any I've ever seen

before.

One-week-old lettuce and peas transplanted successfully

out into the February garden. But how did they fare --- even protected

by quick hoops --- when outside temperatures fell into the mid twenties?

The

lettuce brushed off the cold as if it was nothing and kept right on

growing. The photo above shows lettuce started inside February 12 then

transplanted outside February 19 (on the right) versus lettuce

direct-seeded on February 19 (on the left), both photographed after

eleven days in dirt.

The

lettuce brushed off the cold as if it was nothing and kept right on

growing. The photo above shows lettuce started inside February 12 then

transplanted outside February 19 (on the right) versus lettuce

direct-seeded on February 19 (on the left), both photographed after

eleven days in dirt.

The difference is

striking. The transplanted lettuce will be ready to eat in a week or two

at this rate! (Yes, I snip the first leaf lettuce very young.) Of

course, transplanting lettuce is pretty fiddly compared to broadcasting a

handful of seed so densely that the crop provides a complete

weed-buffer once the second set of true leaves emerge. But transplanting

a small area looks very much worth it for extra early salads.

How about the pea

seedlings? Results there were a little more spotty. The direct-seeded

control area hasn't come up yet, and among the transplants some

seedlings got a bit burned by the 25-degree night even with a quick hoop

to protect them. On the other hand, other seedlings seem just as

vigorous and happy as always. Looks like my planting calendar --- which

told me to direct-seed a large area of lettuce and arugula under quick

hoops this week but to wait two weeks for the main pea planting --- was

spot on.

Today's the day we started

broccoli and cabbage seeds.

We like Blue Wind broccoli.

Natural beekeepers would strongly frown upon opening up the winter hive, even if the day's high was 66. But natural beekeepers would also frown upon feeding a healthy hive in late February just to boost colony size and prompt maximum honey production. Since I'm committed to doing the latter, I need to do the former as well --- more bees need more space or they'll soon swarm.

I am sticking to the Warre method of nadiring

rather than using the Langstroth method of supering, though. In part,

this is because I'm trying to get the bees out of the Warre hardware, so

I'm hoping they'll build down and finally let me remove that last Warre

box (hopefully full of honey) this summer. But nadiring also makes

intuitive sense for spring expansion.

I am sticking to the Warre method of nadiring

rather than using the Langstroth method of supering, though. In part,

this is because I'm trying to get the bees out of the Warre hardware, so

I'm hoping they'll build down and finally let me remove that last Warre

box (hopefully full of honey) this summer. But nadiring also makes

intuitive sense for spring expansion.

To that end, I dragged

Mark out to help me lift the existing hive up in preparation for

slipping new boxes underneath. But the hive (minus roof) was just barely

light enough that I could manage it on my own without straining my

back. I didn't take the boxes apart because I was trying to minimize my

intrusion as much as possible, but the moderate weight seemed pretty

good for this time of year, suggesting that there's at least a little

bit of honey left inside for the bees to consume as they wait for true

spring.

Now, if I can just remember to buy sugar in bulk, we might have our first good honey harvest since 2010....

Despite the initial dripping when we tapped a black birch Monday, it turns out the first week of March is too early for significant accumulation after all. Four days later, we'd only racked up a quarter of a cup of frozen sap --- no wonder since the daytime highs have only  been reaching the low forties.

been reaching the low forties.

With another warming

trend on the horizon, I'm hopeful we'll get more sap soon. There are

half a dozen sizable birches in that same area, actually, so the tricky

part will be deciding whether I want to tap them all or keep our project

on the fun, hobby level.

Of course, since I can take the goats out with me to both tap and

collect sap, the fun quotient may well remain high even if I tap all

half dozen. Every project is more fun with goats.

I love stump dirt, but my

onion seedlings apparently aren't nearly so keen. I ran a side-by-side

comparison of stump dirt versus store-bought potting soil...and the

latter won by a landslide.

Despite my disappointment

that the homegrown organic matter failed the test, I can guess the

reasons. Stump dirt does a great job holding moisture and looks like

rich, fluffy ground. However, if the product really is simply beetle castings, I might be seeing the same problem that those who use straight worm castings with seedlings see --- excess salts keep the baby plants from thriving.

Either way, I'll squash

my urges to go entirely homemade and will start my next round of seeds

in store-bought potting soil. After all, the final crop is the goal and

I'll take whatever path I need to in order to achieve that destination.

The crocuses are running late this year...which apparently means nothing at all. But I sure hope it makes the tree flowers run equally late!

Finding ways to harvest

tree fruits despite late spring freezes is one of my thought projects

for the year. Possible solutions I've come up with include:

- Easily coverable espaliers so I can protect opening flowers from hard freezes.

- Espaliers along an earthen bank so the thermal mass of soil can do the job for me.

Planting late-blooming varieties.

Planting late-blooming varieties.- Planting standard-sized apples in hopes the blooms near the top of each tree won't get nipped. (We don't have tree-free room to try this...yet.)

- Finding less frost-prone pockets on our property, perhaps the

south-facing hillside across the way. Unfortunately, this would require

considerable tree removal.

One option I've read about that doesn't seem to work here is:

- Planting trees on the north side of a building or hillside to slow

down their bloom cycle. That's where our high-density apple planting

is...and they still persist in getting nipped each spring.

I'd be curious to hear

from others who regularly see tree flowers in March when you still have

ten weeks of cold weather to go. Have you found any solution to the

frost-nipped blossoms and fruitless years that result?

Several of you made thoughtful and thought-provoking comments on my potting soil vs. stump dirt post (both on and off blog). So I thought it deserved a followup post.

John

asked whether veggies started in stump dirt might grow slower but then

do better in the long run. This is a valid hypothesis --- I'm always a

proponent of starting seedlings off in low-nutrient areas at first so

they'll develop good root systems. That said, the issue with stump dirt

tends to be seedling death, not slow growth, which suggests the problem

isn't low nutrients at all.

John

asked whether veggies started in stump dirt might grow slower but then

do better in the long run. This is a valid hypothesis --- I'm always a

proponent of starting seedlings off in low-nutrient areas at first so

they'll develop good root systems. That said, the issue with stump dirt

tends to be seedling death, not slow growth, which suggests the problem

isn't low nutrients at all.

But I'm not giving up on stump dirt entirely. I've had great luck

using the homegrown amendment for potting up

tomatoes, peppers, and other seedlings that

spend quite a bit of time indoors. I'm just disillusioned about stump

dirt's efficacy at getting plants from the seed to the two-true-leaf

stage

--- the area where I've traditionally had the most failures in the past.

I'm hopeful that starting them off in potting soil then moving up to

stump dirt will eliminate that issue while also keeping costs low for my

always over-ambitious indoor spring garden.

We suspended our kitchen

counter with two heavy duty spring

loaded snap links.

I've been blown away by the preorder interest in Small-Scale No-Till

Gardening Basics. Clearly, the topic has hit a

nerve! Here's hoping that everyone enjoys the writing inside now that the book is live.

I've been blown away by the preorder interest in Small-Scale No-Till

Gardening Basics. Clearly, the topic has hit a

nerve! Here's hoping that everyone enjoys the writing inside now that the book is live.

If you haven't snapped up your copy yet, you can do so today on any of the following platforms:

And while I'm regaling you with book news, part three in the series ---

Balancing Soil Nutrients and Acidity --- is up for preorder as well.

Once again, I'm

giving you a couple of days to nab the ebook at 99 cents before it goes

up to its real price of $2.99. So if you want to learn about the science

behind remineralization, along with information on how to mitigate soil

deficits and problematic pH using chemicals, cows, goats, chickens,

mushrooms, cover crops, dynamic accumulators, and more, then here are the links for

you:

Finally, just as a reminder, these ebooks are sections of the print book The Ultimate Guide to Soil,

which is currently up for preorder and will be hitting bookstores and

libraries in July. So if you'd rather wait a few months and read on

paper, that option is available as well.

Thanks so much for

reading! Your support lets me spend my days experimenting with kill

mulches, goats, and cover crops, then reporting those results to you on

the blog. So I hope you know I appreciate everyone who buys a copy,

tells their friend, shares this post on social media, or leaves a

review. You are why I write.

Good news! Artemesia is pregnant. I've been feeling under her belly right in front of her udder like Karla

suggested...feeling nothing. Then, Monday morning, a kick! Actually,

Artemesia's little parasite(s) were very rambunctious that morning,

kicking repeatedly...which is handy since I might have otherwise

considered that first movement a fluke. So now I can go back to

wondering what sex, what color, and how many.

The bad news is,

Artemesia is no longer in tip-top health. About a week ago, I started

noticing her fur losing its shine and a bit of dandruff cropping up.

Granted, both of our goats are also shedding their winter fur at the

moment, which gives them a bit of a scruffy look...but Artemesia just

looked scruffier than she ought. A peek at her inner eyelids determined that they were quite a bit paler than Abigail's, a sure sign of anemia and a likely sign of worms.

Just as when this last happened, I first took a look at the kelp feeder. It wasn't precisely empty...but

goats are a lot like cats. You know how cats will look at the last two

tablespoons of kibble, turn up their noses, and beg for more as if

they're starving to death? Apparently, that's a goat's take on the dregs

of kelp as well.

Just as when this last happened, I first took a look at the kelp feeder. It wasn't precisely empty...but

goats are a lot like cats. You know how cats will look at the last two

tablespoons of kibble, turn up their noses, and beg for more as if

they're starving to death? Apparently, that's a goat's take on the dregs

of kelp as well.

So I topped up the kelp

feeder and started the herd on a daily garlic campaign as well. I've

tried chopping up garlic and putting it in our goats' feed...and they

have a fit. Rightly so --- who wants a big bite of raw garlic when

you're expecting sweet potatoes? However, I soon discovered that goats

are quite willing to eat an after-dinner mint garlic

out of the kelp feeder. In fact, they've been going through a head of

garlic a day between them --- I'll have to cut them off soon!

Within

four days, Artemesia's fur started shining again. But her eyelids still

aren't as bright as Abigail's. I'm kicking myself for not looking at

Artemesia's eyelids when she seemed in tip-top health since individual

goats can have different baselines. Instead, I'm ordering some chemical

dewormer just to be on the safe side...and I'm also going to pull out

our microscope and see if I can get an assessment of worm load in her

poop. Mark's going to love our dinner-table conversations this week....

Within

four days, Artemesia's fur started shining again. But her eyelids still

aren't as bright as Abigail's. I'm kicking myself for not looking at

Artemesia's eyelids when she seemed in tip-top health since individual

goats can have different baselines. Instead, I'm ordering some chemical

dewormer just to be on the safe side...and I'm also going to pull out

our microscope and see if I can get an assessment of worm load in her

poop. Mark's going to love our dinner-table conversations this week....

We had some big logs that

required a bump up from the battery

powered saw.

The Stihl tech in Gate City at

Broadwater feed store tuned up our old 039 and is now the only place

I'll go for future service.

Mark and I snuck away to

visit the McClung Museum in Knoxville Wednesday. It was a long drive ---

4.5 hours round trip and probably a bit beyond what I'd usually

consider a fun day trip. But I was feeling in need of an adventure and

Mark is always willing to oblige my infrequent impulses to leave the

farm.

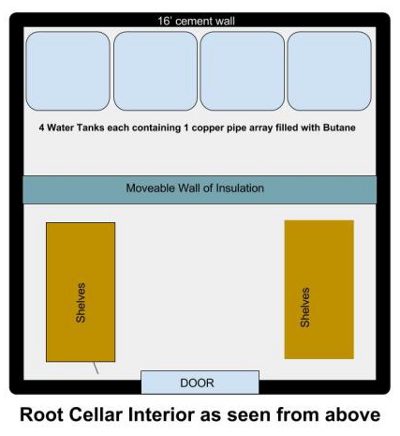

The really impressive

exhibits were about the geology and archaeology of Tennessee. But I need

to digest a bit before I regale you with lessons learned from those

rooms. So, instead, I'll just show you a couple of shots from the Mayan

exhibit. A lot of the Mayan artifacts were actually reproductions, but a

few --- like the toad and rabbit pots at the top of this post --- were

the real deal.

We returned home half an

hour before sunset, and I was already itching to get back to my darling

goats, my spoiled cats, and my impatient garden. I guess I got that

travel-lust out of my system just in time --- 6.5 weeks left until

milking season!

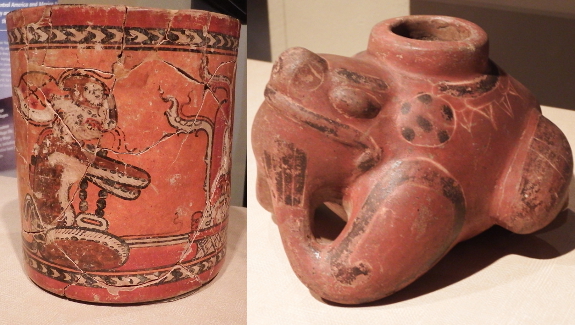

As with our bees, I hate

the idea of pumping chemicals into our goats unless I'm positive they

have a problem with worms. The solution to this dilemma is what

scientists euphemistically refer to as a fecal exam and what I call a

goat poop analysis. Basically, you're looking for eggs of the parasitic

worms that give your herd such a hard time, then you use the number of eggs to decide whether to deworm.

"Okay, Anna. You just lost me," says the random reader. "How am I going to see microscopic worm eggs, let alone count them?"

Well,

gentle reader, I'm glad you asked! It's pretty simple --- first you

follow your goat around staring at their butt until they poop. Next, you

gather three fresh pellets and mash them up in a solution of water

saturated with epsom salts. Then you strain out the non-microscopic gunk

using a clean rag and pour the remaining liquid into a test tube. Fill

the tube to the brim with a bit more of your epsom-salt solution, place a

cover slip on top so it's fully touching the liquid, wait 20 minutes,

and the worm eggs should float to the surface and adhere to your cover

slip. Then it's just a matter of examining the resulting slide under a

microscope to see if you find any worm eggs.

Well,

gentle reader, I'm glad you asked! It's pretty simple --- first you

follow your goat around staring at their butt until they poop. Next, you

gather three fresh pellets and mash them up in a solution of water

saturated with epsom salts. Then you strain out the non-microscopic gunk

using a clean rag and pour the remaining liquid into a test tube. Fill

the tube to the brim with a bit more of your epsom-salt solution, place a

cover slip on top so it's fully touching the liquid, wait 20 minutes,

and the worm eggs should float to the surface and adhere to your cover

slip. Then it's just a matter of examining the resulting slide under a

microscope to see if you find any worm eggs.

(Yes, I glossed over a lot of factors in that paragraph. This website contains the most scientific and, at the same time, home-user friendly explanation I've run across.)

The biggest problem I've

had with this experience so far is the obvious --- the watched goat

never poops. The easiest way to get your goat to defecate on command is

to wait until she stands up. The trouble is, Artemesia is such a people

pleaser, she jumps to her feet as soon as I step out the door. So I did

finally get some pellets Thursday....but they came from Abigail.

I figured I'd go ahead and try my hand at analysis anyway, even though Abigail's not the one I'm worried about. So I wasn't surprised that I didn't find anything I was sure were worm eggs. (This site

has some good images of various goat intestinal parasites. But,

basically, you're looking for ovals with circles inside.) Instead, I

mostly found lots of debris, one colony of what I think is probably

bacteria, and a few of what I think are probably plant cells that didn't

get entirely digested.

Now I just need to watch

Artemesia's butt a little longer and see what I find in her poop. In the

meantime, I've increased her concentrates in case she's anemic because

of growing kids instead of intestinal parasites. And I'm also taking the

time to sit with her while she eats so Abigail can't bully our first

freshener out of the last of her ration. Here's hoping by the time I

catch some fresh pellets from our darling doeling, Artie will be in peek

health and my anemia scare will be a thing of the past.

This basketball floated down

to our ford

and decided to just hang around.

He's been here almost a week!

I've started calling him

Wilson each time I walk by on my way to our parking area.

You'll be unsurprised to learn that my favorite exhibit at the McClung Museum

was the Native American wing. Not only is this one of my favorite

topics to learn about, but the exhibit was also based on archaeological

sites and artifacts from Tennessee, making the information very close to

home.

I particularly enjoyed

the way exhibit creators focused on how-we-know as well as what-we-know.

For example, from the exhibit above: "Corn was ground into meal using

mortars and pounders of stone or wood. Archaeologists think women did

the work. Why? The repeated motion caused their arm bones to become

thicker and stronger than those of Archaic Period women --- a change not

seen in men."

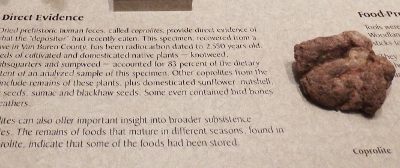

Or,

more succinctly, take a look at the coprolite to the left. Yes, that's

fossilized human poop used to analyze our ancestors' diets. I'd heard of

coprolites before, but had never thought of them in relation to our own

species. I mean, how exactly does human excrement become fossilized?

Or,

more succinctly, take a look at the coprolite to the left. Yes, that's

fossilized human poop used to analyze our ancestors' diets. I'd heard of

coprolites before, but had never thought of them in relation to our own

species. I mean, how exactly does human excrement become fossilized?

Much of the rest of the Native American agriculture exhibit contained information I'd read previously in books like 1491 and in more scholarly texts or at museums like Sunwatch. But I was particularly taken by one map (not shown here) that focused on North American cucurbits.

Much of the rest of the Native American agriculture exhibit contained information I'd read previously in books like 1491 and in more scholarly texts or at museums like Sunwatch. But I was particularly taken by one map (not shown here) that focused on North American cucurbits.

Guess which type of currently cultivated squash evolved very close to where we now farm? The crookneck squash...which just happens to be the one summer squash I find easy to grow organically in our bug- and fungus-rich environment.

Of

course, the exhibit wasn't all about field corn and summer squash.

There were plenty of cultural tidbits as well, such as clay figurines

like the one above and ornaments like the one shown to the left.

Interestingly, the pendant is supposed to represent the Cherokee myth of

the water "spider," which brought fire on its back across the water

from gods to humans.

Of

course, the exhibit wasn't all about field corn and summer squash.

There were plenty of cultural tidbits as well, such as clay figurines

like the one above and ornaments like the one shown to the left.

Interestingly, the pendant is supposed to represent the Cherokee myth of

the water "spider," which brought fire on its back across the water

from gods to humans.

I put "spider" in quotes

in the previous paragraph because, from the image, I think this

particular pendant actually represents a water strider. Yes, both water

spiders and water striders do exist. Of the two, I think the latter is

more likely to carry fire over long distances since they skim rather

than scurry across the water.

There

were other fascinating artifacts, too, like this 32-foot-long canoe

that was found drifting in the Tennessee River. Mark and I both

scratched our heads over the ungainliness of such a tremendous vessel

until I decided it must have been used like a Uhaul moving van. My guess

will have to stand since the exhibit gave no indication of the canoe's

real use.

There

were other fascinating artifacts, too, like this 32-foot-long canoe

that was found drifting in the Tennessee River. Mark and I both

scratched our heads over the ungainliness of such a tremendous vessel

until I decided it must have been used like a Uhaul moving van. My guess

will have to stand since the exhibit gave no indication of the canoe's

real use.

Overall, the McClung Museum's "Archaeology & Native Peoples of Tennessee" exhibit

may be the best I've seen on the topic. I only wish I'd skipped the

Mayans so we could have hit the room with my brain fully fresh. In fact,

if it wasn't such a schlep to get to Knoxville, I would have used up

all of my museum brainpower on that one room alone. If you're in the

area, I highly recommend giving it a try!

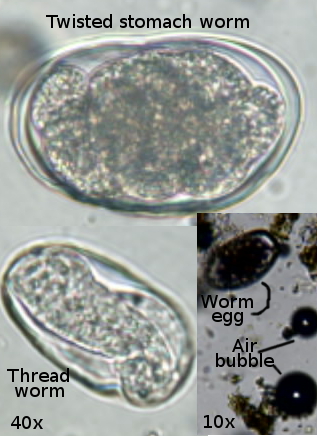

Good news --- finding worm eggs in a goat fecal sample

is pretty easy. Just focus on the air bubbles at 10x and look for oval

shapes on the same level that are just a little larger. Zoom in to 40x

to confirm your ID and figure out the species. Thread worm is

distinctive because you can actually see a little worm wriggling around

inside the egg, while most other eggs look more like the top picture to

the right (which I may or may not have identified correctly to species).

Good news --- finding worm eggs in a goat fecal sample

is pretty easy. Just focus on the air bubbles at 10x and look for oval

shapes on the same level that are just a little larger. Zoom in to 40x

to confirm your ID and figure out the species. Thread worm is

distinctive because you can actually see a little worm wriggling around

inside the egg, while most other eggs look more like the top picture to

the right (which I may or may not have identified correctly to species).

Bad news --- Artemesia's

worm load is indeed too high. I counted about 50 eggs on my slide,

mostly thread worm but some (probably) twisted stomach worm as well.

That count might equate to about 2,500 eggs per gram, which is higher

than is optimal.

While I'd love to stay

organic with Artemesia, I don't want to risk her health during

pregnancy. So I went ahead and treated her to a dose of Safe-guard

(fenbendazole), which is supposed to be okay for use during pregnancy. I

also changed her over to our other winter pasture since thread worms

enter a goat's system through the hooves in wet ground. Looks like that muddy spot

that offended my sense of order (and Abigail's dignity) also offends

Artemesia's health. Time to think of a solution for winter goat lounging

near the gate.

In early March, the grass

is just barely starting to grow and there's not very much to see yet in

the garden. But, despite the brownness of winter, this is still a

pivotal time of the growing year. Not only am I making new beds like the

one shown here, I'm also planting annuals and nurturing perennials.

On the list for the month

--- weeding around the garlic, which is starting to grow like

gangbusters now that the serious cold has fled. A newspaper layer

beneath the straw did a great job keeping weeds at bay everywhere except

around the plants themselves. But it's still better to yank that dead

nettle before it goes to seed!

Other overwinterers won't

be around long, so I'll wait to deal with weeds until it's time for the

next crop. Above, you can see the tiny bit of kale that survived the

winter under a quick hoop. Now exposed to spring rains, the leaves are

slowly but surely beginning to grow again.

The

cabbage shown to the left was more of a surprise. I can't recall

whether it was just a small plant that didn't have time to head up last

fall or a plant that resprouted after I harvested the main head. Either

way, it accidentally got covered by a quick hoop due to its proximity to

the parsley. And when I took off the cover, the crucifer started to

regrow. I guess we'll have one ultra-early cabbage this year!

The

cabbage shown to the left was more of a surprise. I can't recall

whether it was just a small plant that didn't have time to head up last

fall or a plant that resprouted after I harvested the main head. Either

way, it accidentally got covered by a quick hoop due to its proximity to

the parsley. And when I took off the cover, the crucifer started to

regrow. I guess we'll have one ultra-early cabbage this year!

Most of my attention,

though, is focused on March, April, and May plantings. To that end, I'm

spreading various types of compost on spring beds. I'm not 100% happy

with any of my homegrown compost...yet. But that's okay because a little

extra time in the dirt works wonders toward mitigating high-nitrogen

chicken bedding and high-carbon garden-weed compost. Here, I'm

topdressing beds that won't be planted until the first of May, giving

the compost plenty of time to mellow in the interim.

This final shot shows the

results of my February garden-redesign campaign. I shoveled all the

good dirt from shady beds to make one long new bed on the left side of

the photo in an area that enjoys full sun. The topsoilless areas in the

foreground will be seeded in oats and clover so goats can enjoy a nibble

as I work in the garden.

There are a few more

areas I want to redesign too. But now that spring is here, I suspect

those beds won't be remade until the fall. Oh well, my garden is now and

always a work in progress!

We installed two goat decks to give our girls a place to lounge during the day.

A year ago, Mark and I plugged oak logs with shiitake spawn.

This is our second round of shiitakes, but our first logs didn't last

as long as we thought they should have. So we put in a bit more effort, building the fungi a station up off the ground in a shady spot and watering them during droughts (or rather, when I remembered).

A year ago, Mark and I plugged oak logs with shiitake spawn.

This is our second round of shiitakes, but our first logs didn't last

as long as we thought they should have. So we put in a bit more effort, building the fungi a station up off the ground in a shady spot and watering them during droughts (or rather, when I remembered).

Fast forward ahead twelve months, and we harvested a bowlful of Native Harvest and Snow Cap

mushrooms! There's about that many unexpanded buttons to be harvested

later in the week too and many more to come in the years ahead.

As a side note, the first miniature mushroom log to

fruit is providing quite a good crop --- three medium-sized mushrooms.

Mark and I both think these little logs would make great gifts for

homesteaders to give suburbanite friends who have neither the space nor

the energy levels to move larger logs around. The minis don't fruit any

faster than the big logs (despite my hopes), but they do seem to produce

a good-size crop in a very manageable package. The next question will

be --- do minis last as long as the big logs?

As a side note, the first miniature mushroom log to

fruit is providing quite a good crop --- three medium-sized mushrooms.

Mark and I both think these little logs would make great gifts for

homesteaders to give suburbanite friends who have neither the space nor

the energy levels to move larger logs around. The minis don't fruit any

faster than the big logs (despite my hopes), but they do seem to produce

a good-size crop in a very manageable package. The next question will

be --- do minis last as long as the big logs?

I'll end by sending you to my ebook Weekend Homesteader: March for step-by-step instructions about turning trees from your woodlot into easy edible fungi. Now's the time to plug logs, so best get crackin'!

I

can still remember where I was when I first saw it --- a picture of a

man harvesting tomatoes from the top of an extension ladder. Louis Ver

had grown a 23-foot-tall plant a few decades earlier in a town only 45

minutes drive from where I lived in Pennsylvania. Best of all, he had done it

organically and picked over 200 tomatoes from the plant over the course

of the season! I couldn't wait to try it for myself.

I

can still remember where I was when I first saw it --- a picture of a

man harvesting tomatoes from the top of an extension ladder. Louis Ver

had grown a 23-foot-tall plant a few decades earlier in a town only 45

minutes drive from where I lived in Pennsylvania. Best of all, he had done it

organically and picked over 200 tomatoes from the plant over the course

of the season! I couldn't wait to try it for myself.

I loved the colors and flavors of heirloom tomatoes, but was sometimes

disappointed by the yield. I was pretty sure that this was the answer to

my problems. In the years since, I have continued to read and

experiment in an attempt to achieve maximum yields on my tomato plants. I

would like to share a few quick tips that will help you to grow more

tomatoes as well, even if you don't want to leave the safety of the

ground.

Tip #1: Provide constant moisture.

If a plant has all of the sunlight and fertilizer in the world, and a

wealth of perfect soil beneath it, its growth will still be frustrated

if it doesn't have the moisture it needs. Ruth Stout once had me

convinced that rich soil and a good mulch would retain all of the

moisture that my plants needed. But even when I gave my tomatoes an

occasional gallon of "irrigation tea," per Louis Ver's recommendations, I

ended up realizing that I was dwarfing the plants due to insufficient

moisture.

Tip #1: Provide constant moisture.

If a plant has all of the sunlight and fertilizer in the world, and a

wealth of perfect soil beneath it, its growth will still be frustrated

if it doesn't have the moisture it needs. Ruth Stout once had me

convinced that rich soil and a good mulch would retain all of the

moisture that my plants needed. But even when I gave my tomatoes an

occasional gallon of "irrigation tea," per Louis Ver's recommendations, I

ended up realizing that I was dwarfing the plants due to insufficient

moisture.

Here is the easiest and most efficient way that I have found to water a

very big plant. Drill a hole in the side of a 5 gallon bucket, right

where the bottom and side of the container meet. Set it 1 to 2 feet from

the base of the tomato plant, with the hole aimed toward the plant, and

fill it once weekly, letting the water drain out slowly over 5 to 10

minutes. If you don't have a supply of rain or pond water, let tap water

age in a bucket for a day or more before dumping it in the bucket with a

hole to give any chlorine time to evaporate and the water time to warm

to outdoor temperatures. This slow trickle will create a reservoir of

water in the soil directly beneath your plant that it can draw from over

the course of the week.

Tip #2: Provide constant fertility.

I've learned that spreading compost around your plant once at the

beginning of growing season is a bit like giving a child a seven-course

meal as soon as they are born and never feeding them again. Of course,

organic fertilizers are known for being slow-release, but this doesn't

mean that they don't lose potency as the elements leach away their

nutrients. It was my pole beans that first convinced me that the "once

and done" plan was foolish. Every year bean production would peter out

at some point, after which I would place a few shovels of compost in a

bucket of water, mix it up, and dump along the row. Within two weeks the

plants were pumping out beans at a machine gun pace again! At some

point I thought, "Why don't I just do this every two weeks all season

long?"

Tip #2: Provide constant fertility.

I've learned that spreading compost around your plant once at the

beginning of growing season is a bit like giving a child a seven-course

meal as soon as they are born and never feeding them again. Of course,

organic fertilizers are known for being slow-release, but this doesn't

mean that they don't lose potency as the elements leach away their

nutrients. It was my pole beans that first convinced me that the "once

and done" plan was foolish. Every year bean production would peter out

at some point, after which I would place a few shovels of compost in a

bucket of water, mix it up, and dump along the row. Within two weeks the

plants were pumping out beans at a machine gun pace again! At some

point I thought, "Why don't I just do this every two weeks all season

long?"

I was on the right track. I soon read about experts who do something

very similar, as Eliot Coleman spreads a "side-dressing" of compost

around each tomato plant monthly and Steve Solomon "fertigates" his

larger plants with a 5-gallon bucket of compost tea every other week. I

often use a method that is a hybrid of the two, slowly dumping a few

gallons of my compost "stew" (compost left in, as with the pole beans)

around the base of the plant twice a month in addition to my watering

schedule. It really doesn't take much compost to maintain fertility in

this manner as long as you planted in good soil or spread  an inch of compost in a two foot wide circle around your transplant; a trowel scoop per gallon of water seems to be adequate.

an inch of compost in a two foot wide circle around your transplant; a trowel scoop per gallon of water seems to be adequate.

Tip #3: Give your plant room to grow.

Years ago, I planted my tomatoes pretty closely, lopped off all suckers

in an attempt to channel the nutrients into that one precious vine, and

trained them up twine to a trellis. I later realized that I was

severely limiting productivity. This method is fine if you have to grow

20 varieties in a twenty foot garden bed, have lots of time for pruning,

and a trellis to train all of your single vines up to, but you won't

get much from each plant. I could have grown more tomatoes with four

plants per bed and my current techniques.

Here are two methods that work best in most situations:

- Giant tomato bush. First, plant your tomato in full sun at least five feet from any other large plant. Next, go to a hardware store and buy two sheets of re-mesh (used to reinforce concrete). Back at home, fasten the ends of one sheet with wire, and you will have a cage 3 1/2' high to set around your tomato plant. Do the same with the second, and then put it on top of the first, wiring it securely in place. Tie the cage to one or two stakes that are pounded in securely to prevent the contraption from tipping when the plant gets big. You now have a 7' tall cage, which will hold your giant tomato "bush" securely for the season, as the vines will have to reach at least 14' in length in order to grow over the top of your cage and back down to the ground. Best of all, most of you will be able to reach all of the tomatoes without even standing on your toes! (The one in the picture is just about to flop and head downward after growing out the top of a 10 1/2' cage.)

Sky-high climbing vines.

For this method, you'll need to plant your tomato in full sun beneath a

second-story balcony, window, or chimney. Next, buy a rope at least 25'

long made of rough, natural material (I've used sisal.) Third, tie the

rope to something (the balcony railing, chimney, etc.) up on the

second story, and the other end gently to the base of

the tomato plant (wait until it's not too small and tender). Then,

as the plant grows, twist its trunk gently around the rope. You'll need

to get up on the ladder weekly to trim suckers with this method,

but can allow about 4 vines to climb the rope without everything coming

undone, and without limiting your plant's height or productivity. I

harvested 500 cherry tomatoes from a single vine when I first tried

this, and each additional vine can produce just as many!

Sky-high climbing vines.

For this method, you'll need to plant your tomato in full sun beneath a

second-story balcony, window, or chimney. Next, buy a rope at least 25'

long made of rough, natural material (I've used sisal.) Third, tie the

rope to something (the balcony railing, chimney, etc.) up on the

second story, and the other end gently to the base of

the tomato plant (wait until it's not too small and tender). Then,

as the plant grows, twist its trunk gently around the rope. You'll need

to get up on the ladder weekly to trim suckers with this method,

but can allow about 4 vines to climb the rope without everything coming

undone, and without limiting your plant's height or productivity. I

harvested 500 cherry tomatoes from a single vine when I first tried

this, and each additional vine can produce just as many!

Never in my life have I

spent as much time on personal daily hygiene as I've spent lately

grooming our pregnant goat. My goal isn't really to make her look

pretty, though. Instead, I  have a couple of more constructive points on my daily agenda.

have a couple of more constructive points on my daily agenda.

The first is to keep

myself occupied while Artemesia eats her morning and evening ration at a

snail's pace. I realized a few weeks ago that Abigail was getting the

lion's share of Artie's food (as well as all of her own) since our

horned goat eats at lightning speed then bullies our smaller, hornless

goat away from the rest of her dinner. So now I lock Abigail out of the

goat shed while Artemesia nibbles on her alfalfa pellets and roots.

And even though it sometimes seems like a long time to wait on a busy

morning, I'm actually glad Artie is a slow eater. That trait means I

won't have to overfeed the doe just to keep her occupied while milking

the way I did with Abigail.

So I brush our goat to

keep myself from getting bored while Artie eats, right? Well, not

entirely. I'm also trying to get her used to being touched all over long

before the kid(s) arrive. I have a feeling that if I'd done this with

Abigail, it wouldn't have been such a hassle (especially at first) to drawn down her milk.

Of course, Artemesia is

much more malleable and people-oriented than her herd mate already. But

even she flinched and tried to tuck her hindquarters the first few times

I gently felt at her expanding udder. After a couple of weeks of

personal attention, though, she's still not entirely thrilled at being

felt up but she accepts it as a necessary part of eating her  daily carrots.

daily carrots.

While I'm messing around

down there, I also press up gently on Artemesia's belly. About 90% of

the time, Aurora (or her brother) kicks back. I have a feeling that if I

was more experienced, I'd be able to guess how many kids are in there

using this push test, but I can never seem to remember exactly where the

last kick happened well enough to know if more than one kid is nudging

its mother's insides.

If I run out of goat to

brush and prod, I move on to giving our darling a pedicure. I'm very

glad to see that her hooves are suddenly growing a rate more

commensurate with her food intake --- a good sign that the wormer

might have licked her parasite problem. The insides of her eyelids

might also be getting a little pinker, but that's harder to tell since

my camera tends to misread colors in closeups of Artie's dark face.

As you can tell, though,

I'm not entirely teaching our first freshener good habits. Once she's

done with the food in the stanchion, she moves on to licking out the

bowl. Oh well --- a beloved goat needs to be at least a little bit

spoiled, right?

Sometimes I go outside

with the camera to take a picture of one thing...but a closer look

points out that something else entirely is going on.

For example, I've been noticing pear buds beginning to break dormancy over the last few days. "Slow down!" I told the tree.

But when I took a second look, I realized that only the branches of the original variety on this topworked tree

were opening up. The grafted-on variety --- shown slightly out of focus

in the foreground of the main photo --- is still holding tight. Looks

like the new varieties I chose for flavor might also be better at

resisting late frosts as well.

Less pleasantly, I

watched Lucy kill this black rat snake while I was pruning the

blueberries Monday. I always beg her not to attack rodent-eating

reptiles, but our usually well-behaved dog goes tunnel-vision when she

smells a split tongue.

It turns out that just

this once, the snake she was after was actually a villain. No, not

poisonous --- a nest-egg robber! We keep golf balls in our chicken nest boxes to give dim-witted birds the impetus to lay in an easy-to-gather spot. The snake must have swallowed one of these fake eggs, then learned the hard way that plastic doesn't digest the way shells and yolk do.

I still would rather Lucy

didn't lay down the ultimate punishment. But I felt a little less

guilty when that big white ball popped out of the snake's belly.

I'm a big fan of this green plastic trellis material.

I use it every year with a few U-posts for supporting peas --- easy to erect and easy to dismantle.

I've used it in the past for temporary pastures for young chickens (although in recent years they've been a bit too flighty to contain that way).

I've used it in the past for temporary pastures for young chickens (although in recent years they've been a bit too flighty to contain that way).

I use it in the winter to protect strawberry plants at their most vulnerable from irregular but devastating deer attacks.

I use it in the spring to save seedlings when freshly planted ground looks extremely attractive to our naughty cats.

And I use it around young

trees in chicken pastures. The trellis material isn't strong enough to

keep out goats or deer, but chickens will leave anything within it

alone.

I'd give you an Amazon

link, but I can't seem to find the product online and figure shipping

would be prohibitive anyway. But if you're in Lowes, why not pick up a

roll? Even using my neglectful methods of piling the trellis pieces on

the ground beside the barn when I'm not using them, I've seen no decline

in quality of our stash over the last eight years.

We recently upgraded to a heavy

duty tripod by

Fancierstudio.

It's very well built and

comes with an extra camera plate and a nice carrying bag.

Wanna hang out with the cool kids? A writer friend and I joined up to create a super secret facebook hangout for other homesteaders (and homesteaders-to-be).

This is a spot where you

can chat with each other rather than listening to me ramble on

indefinitely about Artemesia and organic matter. There've been some

inspiring photos and great posts by our initial members and I look

forward to seeing what you have to say.

Want to join in? Just

follow the link above and click the "Join" button. Either Jill or I will

let you in as soon as we notice your request. Looking forward to seeing

you over there.

It was a year ago this week

when we made our

first cold frame.

Today it's brimming with

fresh greens.

Do you need an

inexpensive starter goat for a pastured dairy herd? Abigail's going to

be available as soon as Artemesia's kids are born in a month. Perhaps

you'd like to take her home with you?

Here are some stats:

- She's an unregistered Saanan x Nigerian cross.

- She's in her milking peak (3 years old).

- She can be bred in spring or fall (and is actually in heat today).

- Milk production is uncertain --- I was learning while milking her last year and know I lowered production a lot. You can see her lactation curve here.

- Milk flavor is very good. I haven't had anyone tell me it tasted

goaty, although my brother thought it was almost too rich to drink

straight.

- She's never been wormed and seems to have both parasite-resistant behavior and genes. (She won't touch any food on the ground, for example.)

- She's never been fed grain (well, except for a head of sorghum once in a blue moon for a treat) and keeps her weight on well with alfalfa pellets, roots, and hay.

She's

moderately well trained. She'll jump up on a milking stanchion on

command and only grumbles a bit when you trim her hooves or milk her.

She'll walk on a leash (although she pulls a bit if she gets excited)

and comes when she's called (as long as there's not something tasty

within reach). She follows off leash as long as you're not close to the

garden. She handles being tethered well, knows not to get her horns

stuck in cattle panels, and understands electrified poultry netting. In

her previous life, she was herded with dogs. (Okay, this sounds like

she's really well trained. But

you haven't met Artemesia --- when our other goat gets ready to chomp

down on a raspberry leaf, I just say her name in a moderately stern tone

of voice and Artemesia generally obeys me and moves over. My standards

are abnormally high.)

She's

moderately well trained. She'll jump up on a milking stanchion on

command and only grumbles a bit when you trim her hooves or milk her.

She'll walk on a leash (although she pulls a bit if she gets excited)

and comes when she's called (as long as there's not something tasty

within reach). She follows off leash as long as you're not close to the

garden. She handles being tethered well, knows not to get her horns

stuck in cattle panels, and understands electrified poultry netting. In

her previous life, she was herded with dogs. (Okay, this sounds like

she's really well trained. But

you haven't met Artemesia --- when our other goat gets ready to chomp

down on a raspberry leaf, I just say her name in a moderately stern tone

of voice and Artemesia generally obeys me and moves over. My standards

are abnormally high.)- We paid $125 for Abigail and aren't looking to make a profit.

And some stats you might find less enticing:

Both

of the times she was bred, Abigail produced a single kid. (This isn't

necessarily a bad thing, especially if you want to maximize

milk-for-people.)

Both

of the times she was bred, Abigail produced a single kid. (This isn't

necessarily a bad thing, especially if you want to maximize

milk-for-people.)- She has horns and uses them on other goats (although never on

humans). This would actually be a plus if you kept Abigail in a large

pasture that could see predator pressure. (She's very alert at fending

off potential dangers.) But this is a minus if you want to keep her in a

very small herd (like ours) with a hornless goat of a submissive

variety. Basically, she can be a bully to smaller, weaker animals. (Yes,

this is why we're moving her on.)

Still interested? Then drop me an email at anna@kitenet.net.

I want to line up up someone who's willing to take her as soon as

Artemesia's kids are born, so that means you'd need to have your

infrastructure in place and at least one companion goat for Abigail.

(No, she can't live without goat companionship...and you wouldn't want

her to since she'd cry like crazy!)

So, what do you think? Ready for some pastured dairy of your very own?

Do you like scented candles and wax melts? Author Lindsey R. Loucks has

joined her love of story-telling with creative, eco-friendly candles,

wax melts, lip balms, and other products with her company

“turtledinosaur.” Her candles and wax melts are made with renewable,

American grown soy, and include such whimsical names as Make Friends

With Vampires, My Mermaid Tail Is Better Than Yours, and Book Boyfriend.

Each candle and wax melt comes with a short story to explain the name.

When asked what tips she'd give to other aspiring candlemakers, Lindsey answered:

"For example, Book Boyfriend is a mix of oud wood, leather, musk, and a scent called Fierce. It took a while to get the proportions right, but once I did, BAM! Book Boyfriend was created! I knew ahead of time kind of how I wanted it to smell, and I got it!"

One lucky reader is going

to get it too! Comment below with your favorite candle scent and you'll

be put in a drawing for a free sample of Make Friends With Vampires wax

melts.

Don't want to wait for luck to smile on you? Then check out Lindsey's Etsy shop and Kickstarter campaign today. Because who wouldn't want their house to smell like a mermaid's tail?

I'm still in the learning stages with my new high-tech, indoor seed-starting setup.

But so far, I've been very pleased with my results. In fact, seedlings

that usually wouldn't be ready to set out for another two weeks are

begging to be transplanted. Here's hoping that after this current cold

snap, I'll feel comfortable putting cabbages, broccoli, and onions in

the ground.

Speaking of onions, I'm

beginning to see why this has always been my hardest crop. While other

seedlings have been doing a little better in the store-bought potting soil than in the stump dirt,

the difference in growth among the onions is like night and day. I'm

guessing onions are particularly sensitive to salts and I'd been putting

majorly subpar specimens in the ground in years past.

Of course, there are still growing pains. I set the fan

too close to the seedlings at first and nipped back some of those onion

seedlings. Now I've settled on 18 inches away as a good distance to

keep air circulating and harden off the baby plants a bit without

desiccating tender leaves. Live and learn!

Sure enough, our overwintering cabbage is sending out flower buds.

Since we only have one cabbage and it's a hybrid, we'll enjoy the shoots as cabbage raab.

As usual with goats and worms, the result of my second fecal analysis on Artemesia was a case of good news/bad news.

The

good news is that the worms that were really overloading her --- thread

worms --- had a 100% kill rate from Safe-guard. I still feel the kid(s)

kicking in her belly on a regular basis too, so hopefully the

supposedly safe dewormer really did have no negative effects on her

pregnancy.

The

good news is that the worms that were really overloading her --- thread

worms --- had a 100% kill rate from Safe-guard. I still feel the kid(s)

kicking in her belly on a regular basis too, so hopefully the

supposedly safe dewormer really did have no negative effects on her

pregnancy.

The bad news is that the

other species present (possibly twisted stomach worm) wasn't killed at

all, meaning that it's resistant to this common dewormer. In fact, that

species' numbers might have risen slightly after the dewormer reduced

competition for Artemesia's gut space. At 21 eggs in one slide from four

pellets during round two, the other worm's populations are right on the

edge of dangerous...but I'll take a wait-and-see approach there and

test again in a week.

With 20/20 hindsight, here's what I've learned from my first foray into chemical dewormers:

- Identify your worm eggs to species every time you do a fecal exam and then do your counts by species. I wish I had real data (not just a gut feeling) on whether or not the second worm species increased in numbers post deworming.

- Would a probiotic supplement after deworming have prevented the rise of worm species two? I don't know, but it's worth a try.

- Clean out the barn before deworming. I don't want to use the

manure that fell post-deworming in the vegetable garden in the near

future, so I gave our most recent barn cleaning its own composting zone.

The trouble is, I hadn't cleaned out the barn for in a few weeks

beforehand, so I "lost" more organic matter than I would have liked in

the process.

Live and learn!

Although hard freezes

once the garden year starts are always a little dicey, I'm actually glad

a cool spell came along to slow spring down. 21 degrees now while apples vary from silver tip to green tip and pears from green tip to tight cluster

means a small thinning effect on our hypothetical fruit crop. 21

degrees when flowers are fully open would mean yet another year with no

fruit.

The vegetable garden is

similarly unfazed by the return of winter. Baby peas from my second

planting are just barely poking out of the ground, and I actually didn't

even cover them before the predicted cold spell. I was counting on the

fact that the young plants were very close to the earth, which had been

warmed well by weeks of summery sun. Sure enough, both the uncovered

baby peas and the larger transplanted peas under cover came through the

cold snap with flying colors.

In one part of the

garden, though, I'm speeding things up rather than letting the cold slow

things down. About a month ago, I erected quick hoops atop one row of

strawberries. And, at long last, new growth is finally starting to pop

up underneath. In contrast, uncovered plants nearby are still largely

dormant.

Of course, I could do a

lot more if I wanted ultra-early strawberries. A farm down the road

keeps their plants under row-cover fabric all winter and uses black

plastic mulch to keep down weeds and heat the soil around their roots.

As a result, their fields are already blooming...and in great danger

from hard freezes like this. A combination of sprinklers and row cover

fabric will probably keep their crop safe. Still, I prefer to walk the

middle road and speed my strawberries up a bit...but not too much.

We started up our creek irrigation system today to give our Spring garden a boost.

Last year's pile of garden-weeds-and-kitchen-scraps compost

is pretty much empty. You can see what remains of it in front of one of

the covered fig trees in this photo. Basically, a few okra stalks and

squash vines weren't entirely composted, but everything else has been

spread on the garden to feed spring carrots and summer tomatoes.

The next round of garden fertilization will come from goat-barn leavings,

but I'm already building the third installment in the series. The pile

in the foreground of the photo comes from beds cleared to make way for

broccoli and cabbage...and maybe the resulting humus will feed more

broccoli and cabbage in the fall?

Circles and cycles.

Closing the fertility loop is a bit like saving seeds. You have to think

months ahead, but once you get your plans down pat there's not much

extra effort involved.

Three weeks ago, these broccoli and cabbage were my babies. I loved them and cooed over them and urged them to grow.

Now they've been

supplanted in my heart (and under the grow lights) by tomato, pepper,

zinnia, and basil seedlings. So, despite several likely freezes in the

forecast, the crucifers have been moved to the garden to sink or swim.

To give them the best chance of survival, I saturated the ground

beforehand with three hours of sprinkler action. Then, after setting

the babies out and watering them in again, I covered each bed up with

row-cover fabric. Crucifers like these can handle lows in the high

20s...but not while they're getting their feet under them. Plus, we've

had a strange bout of wind for the last two weeks and the sun is pretty

intense at the moment too. All of that adds up to the need for a bit of

additional protection.

Will they survive? I hope

so. If not, I've got about a third as many extra seedlings waiting in

the wings. Hopefully Mom and/or Kayla will take those babies off my

hands next week if this set of transplants survives. (Hear that, ladies?

You've been warned --- get the garden space ready!)

Artemesia seems to spend more time lounging now that she has a bun in the oven.

Artemesia still has four weeks to go. But as you probably noticed in Mark's post yesterday,

she looks very, very pregnant. I'm pretty sure she's got at least twins

in there because I felt kicking at the same time this week in belly

areas about eight inches apart. But I have a sinking suspicion she might

be carrying triplets.

Between the worm scare

and her growing kids, Artie needs a lot of high-quality nutrition. The

trouble is, there literally isn't room in her belly any more for her to

eat much at any one time. So I have her on a three times a day feeding

schedule. Concentrates in the morning, as much fresh greenery as we can

muster this early in the season at lunchtime, then concentrates in the

evening. On hotter days, she doesn't really want to eat at noon, though,

so I have to move everything a little later.

(Yes, I do obsess over our dear little goat. How could you tell?)

In other news, no one nibbled at my goat-sale post,

so it looks like Abigail will be going to the butcher in about a month.

From a purely financial perspective, I think that's actually the better

choice since Abigail will provide quite a lot of high-quality pastured

stew meat. Whether I cry when we drop her off remains to be seen.

We've been having the same

debate for a few years now.

Fix the old chicken tractor

or build a new, more modern tractor.

Now that I've got the nest

box fixed it might last another year.

Is it too early in the year to get the high temperatures necessary for solarization? Will these translucent drop cloths work as well as last year's transparent ones?

Only time will tell. But

it's fun to at least imagine I'm preparing large areas of summer garden

space by shaking out a sheet of plastic and weighing down the edges with

rebar.

We had a perfect hike yesterday along the 300 million year old sandstone cliffs of The Guest River Gorge.

Have you ever been on a cave tour

and been told not to break off the stalactites because they grow an

inch every two hundred years? Then you wonder how exactly scientists

came up with that figure?

At the Guest River Gorge

this weekend, we were treated to a view of baby stalactites in action.

These guys clearly grew faster than average since the little stalactites

on the ceiling were already a few inches long and the "cave" in

question was a train tunnel built in 1922.

Mark figured that at the

rate calcite-laden wader was pushing through the cracks in the vaulted

ceiling, the whole thing would start collapsing in about 150 years. I

guess we're going to have to keep eating lots of kale if we want to be

around to test that hypothesis.

We had a problem with our

newspaper layer of mulch last week.

It all blew away with some

heavy Spring winds.

The new plan is to wet it

first to make it conform to the ground more.

We cut at least twice as

many tulip-trees last summer as we needed for 2015-2016 firewood. The

trees are so tall that it just made sense to fell all the ones we wanted down while we had the pasture fences out of the way.

Now we're getting ready

to put those fences back up so Artemesia will have a completely

worm-free pasture for the weeks immediately following kidding. That

means cutting those huge logs into manageable sections and hauling them

up the hill to the logging road turned log landing. Once there, we can

take our time turning the trunks into firewood and hauling the wood home

since we learned last year that five months of seasoning is sufficient for this relatively soft wood.

I took advantage of the

canopy-free zone last fall to seed a much larger area than we can

currently afford to fence with orchardgrass and clover. Maybe by the

time I come up with another round of fencing money, the goat-friendly

forage will be tall and luxurious?

Over the winter, I

took topsoil from the beds close to the barn and the woods on either

end of the mule garden and created a new bed in a sunnier spot. That

left me with several patches of bare subsoil which are kinda-sorta an

erosion risk. Not really since they're surrounded by solid sod...but the

bare patches still offended my ecologist's eye. So I decided to seed

them in goat-fodder crops so Artemesia and kid(s) can graze in the shade

while I weed the mule garden. Sounds like paradise in the making,

right?

I

started by sprinkling some leftover clover seeds that I'd bought for

the pasture last fall into the bare patches. I could have put in grass

seeds along with the clover, but I didn't want to wait so long for grass

to get established. So instead, I waited until the first true leaves

came out of the clover seedlings, then I added oats to the mix. (I make

this sound intentional --- actually, it took us that long to get to the

feed store and pick up the grain.)

I

started by sprinkling some leftover clover seeds that I'd bought for

the pasture last fall into the bare patches. I could have put in grass

seeds along with the clover, but I didn't want to wait so long for grass

to get established. So instead, I waited until the first true leaves

came out of the clover seedlings, then I added oats to the mix. (I make

this sound intentional --- actually, it took us that long to get to the

feed store and pick up the grain.)

Will the fast-growing

oats overpower the slow-growing clover and make the legume seeding

worthless? Will spring oats suit our goats' palates as well as fall oats

do? You'll have to come back this summer to check out the answer to

this nail-biting, homesteading cliffhanger.

Stretching some top wire to make a height extension for a chicken pasture fence.

My apple-rootstock stool only produced six rooted shoots for use this spring, but my plum stool

is a major overachiever, cranking out nine husky suckers plus four

smaller shoots that I left behind for later. I set the former out in my

nursery bed just outside the back door where I can keep a close eye on

them.

(After taking the photo above, I added some straw on top of the kill

mulch, and I soaked the ground underneath first...just in case you were

worried.)

My goal is to really learn bud grafting

this year since dormant-grafted plums only had a 25% success rate last

year. Hopefully with nine rootstocks to work with, at least a few will

show success.

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.