archives for 08/2015

I'm proud to report that

I've so far met my New Year's resolution of taking one work day off per

month in 2015. During the peak of weeding season, we did dodge a bit and

take two Friday afternoons off per month instead of indulging in a full

day all at once, but Mark said that counts. (He's easing me into taking

time off gently.)

Kayla was my partner in

crime during our most recent random holiday, providing moral support and

acting as my dance partner at the square dancing class at Mountain

Empire's Mountain Music School. We learned the (very) basics of both

flatfooting and of the Virginia Reel and are all fired up to take

another dance class soon. Next up: the classical Indian dance of

Bharatha Natyam. Stay tuned!

We got our wood shed past the

half way mark this week.

There's still a lot more

fallen tree material to cut up which has got us to consider building

wood shed number two in the Fall.

In July, I outlaw all

talk of winter. We don't have enough firewood in, the garden seems like it

will require a time machine to get all of the requisite work done, and

winter stores of all sorts seem inevitably poised to fall short.

In August, I embrace the

changing seasons. The light is subtly different, a spell of cool nights

is bracing and revitalizing. I freeze a sixth of our winter stores in

one week and our wood shed is a little fuller than last year's. I look forward to the harvest successes and accept the inevitable failures as a simple part of gardening.

What a difference a month can make!

In the middle of the

summer, I'm so engrossed in the garden that I just don't have the mental

energy to research deeply into the solutions to thorny problems. Then,

in the winter, all I can remember is the beauty and deliciousness of our

past successes. So I thought now might be a good time to note some

problematic areas of our current garden for future research.

As basic as it sounds,

I'm still a seed-starting amateur. When I start seeds inside under

low-light conditions (I'm too cheap to use a grow light), they often

succumb to damping off. I put the flats outside in the summer sun and

they dry up in a heartbeat. Next, I try to start those same seeds in a

shady damp bed outside, in which case they get eaten up by (I assume)

slugs. And by the time I finally give up and just start the seeds in my

happy garden soil under heavy irrigation, it's often too late for fall

crucifers to have time to grow before our first hard freeze. As you can

see, our brussels sprouts are a bit smaller than I'd hope for at this

time of year, and our fall broccoli may be nonexistent. Definitely a

topic to research! First stop will be The New Seed-Starter's Handbook.

With our tree fruits, I

feel like we're 80% of the way to success...but close only counts in

horse shoes and hand grenades. One obvious issue is the fire blight

on our Seckel pear, but that's probably not worth researching. I

already know that I should have cut out the problematic limbs when they

first started appearing, and I also know that Seckel isn't as disease resistant as other pears we're now trying. Hopefully variety selection will nip this problem in future years.

Late spring freezes are a

more pressing issue since this seems to be the biggest hurdle

preventing us from getting tree fruits at the moment. This winter, I

want to research freeze protection (it really might be worth wrapping

some of our dwarf trees and hardy kiwis) and to start setting out

thermometers at potential orchard areas to gather data on anti-frost

pockets. It's painful to have mature, beautiful trees that simply don't

bear because of one late spring frost, so this topic is near the top of

my research priority list.

It's not a research

topic, but this year I've been more aware than ever before of how

differently my vegetables perform in full sun (tiny patches of our homestead)

versus partial sun. Our okra, for example, is providing about ten times

as many fruits as in previous years. Why? Because I finally put this

non-essential crop in the center of the sun zone. As our garden soil

gets better and better and we're able to shrink our growing area, I want

to be sure to focus our mulch- and fodder-producing crops in the

partial-sun areas to save the full-sun for vegetables.

What's on your winter research list so your 2016 garden will blow this year's effort out of the water?

We started eating a second round of delicious Everbearing Raspberries today.

I

hesitated to make this post since I suspect most of you won't get

anything out of it. Chances are pretty good that 40% of you don't need

this information and another 50% of you will poo-poo it. That leaves

only 10% of our readership who might benefit from this post, so feel

free to look at the pretty picture inside our daughter hive and then move on if you're in the 90%.

I

hesitated to make this post since I suspect most of you won't get

anything out of it. Chances are pretty good that 40% of you don't need

this information and another 50% of you will poo-poo it. That leaves

only 10% of our readership who might benefit from this post, so feel

free to look at the pretty picture inside our daughter hive and then move on if you're in the 90%.

Still here? Okay, I wanted to plug a website I've been using for the past month --- happify.

Mark has been training me to use positive thought to boost my

creativity and pleasure in daily life for years now, and this website's

activities are helping me build on that foundation and take my mental

hygiene to the next level.

I've worked my way through the track "Conquer your negative thoughts,"

finding some activities a bit basic but many others insightful and

thought-provoking. This weekend, I started studying the Mindfulness

track and I can tell it's going to continue to help me simplify and

focus my thoughts so they don't look so much like the image above.

In case you're curious, I haven't paid for any of the potential upgrades

they keep throwing at me (the one downside of the website), but I

thoroughly recommend the free version of happify. Just be sure to click

on the little "why it works" links to learn more about the science

behind the projects.

Homesteading is all about

choosing your own adventure, and that adventure can be terrible if your

brain isn't in the right spot. So, go on, happify!

We got 9 bales of hay bought, hauled, and stowed in the Star Plate barn today.

I'll be honest --- this post is really an excuse to share cute pictures of goats.

But there's always

something to say about our darling herd of two. For example, I've

learned that they adore sweet-corn stalks (after we've harvested the

good ears), picking off the leaves and eating the ears that didn't

develop properly. I can smell the sweetness as I cut the spent stalks,

so it's no surprise that our grain-free herd adores the fodder. Our

goats look for sugar wherever they can find it.

Artemesia is thirteen

months old now, and she's starting to act a bit more like a teenager.

That means she's darling one minute, then the next minute she wanders

off on her own and doesn't obey my request to return to the pasture

after we've finished our evening hour of grazing in the woods. Luckily,

our doeling's sunny personality inevitably comes through in the end, and

those teenage moments are still much rarer than Abigail's more frequent

strong-headedness. (Our older doe is an independent woman.)

In other goat news, I'm solarizing weedy areas and prepping as much fallow garden ground as I can this month to really boost our fall oat cover crop. Our goats adore grazing on oats after summer weeds are only a memory,

and I suspect that with careful management we could cut our hay needs

in half using the cover crop. We're still in the early days of

goatkeeping, though, so I keep my goals simpler --- plant what I can,

and don't worry too much if I have to buy feed to fill in the gaps.

These new concrete deck blocks will be used for the new wood shed.

In a shocking display of

preemptive selfishness, I planned our August random holiday for only

five days into the month. Kayla had found out about a workshop teaching a

classical dance from the southern part of India, and she was kind

enough to let me come along while she checked it out.

Bharatha Natyam looked so

easy when I watched a youtube video before the class, a bit like a

walking version of yoga. Boy was I wrong! Kayla and I were surrounded by

a passel of young dancers who had been studying ballet for years, and

they had no trouble picking up the steps. But figuring out how to move

my feet and my arms and my hands all in sync was vastly beyond my skill

level, especially once the teacher went at full speed. The dance was

definitely beautiful and fun though!

What I liked most about

the class was the realization that the scenes I'd studied in art history

class of Indian gods in strange poses involved catching those beings

mid-dance. The teacher also opened the class with a simple earth

blessing that I want to learn to incorporate into my own

cobbled-together spiritual practices...but that will only happen if I

can find a video to walk me through the motions on the internet.

Drinking from the fire hose, I'm afraid none of the instruction actually

stuck to my gut.

Despite my inability to recall the most basic steps, it was still so

much fun to go outside my comfort zone and explore new things. I'm

looking forward to seeing what Kayla comes up with for us to try next!

On a weekend near the 4th of

July we, my parents, two younger sisters and I would pile into the

family's 1948 Chevy and drive out in the county to a farm near Shultz,

where my mother's classmate, Feeny, lived. The road into his house

went up a creekbed bordered by a hill on the right and a grown-up

pasture on the left, where a few cows grazed around blackberry

bushes. We  pulled

out of the trunk a washtub, five-gallon pail, and several picking

buckets made by cutting the tops from grapefruit juice cans and punching

two opposing holes to attach a wire bale.

pulled

out of the trunk a washtub, five-gallon pail, and several picking

buckets made by cutting the tops from grapefruit juice cans and punching

two opposing holes to attach a wire bale.

We'd get there early, before

the heat of the day. With the picking-can bale fastened to my belt

I would wander around avoiding others picking blackberries until my can

was in danger of spilling. Then I would take it to where Dad had

left the pail and empty it. When it was full, Dad would empty the

pail into the washtub. Before noon we'd leave with a trunkful of

washtub, pail and picking buckets all filled to the brim with berries.

That

afternoon I'd help Mother sort out clean berries from a water-filled

tub, pulling any stems, removing floating leaves and debris. When a

container was full of clean berries Mother would fill quart jars, seal

them with zinc lids and a rubber gasket, add sweetened liquid, and place

seven at a time into a water-bath canner. When they were finished

she removed the jars, tightening the lids firmly and setting them aside

to cool while she prepared another container full. Meanwhile I was

sorting clean berries.

That

afternoon I'd help Mother sort out clean berries from a water-filled

tub, pulling any stems, removing floating leaves and debris. When a

container was full of clean berries Mother would fill quart jars, seal

them with zinc lids and a rubber gasket, add sweetened liquid, and place

seven at a time into a water-bath canner. When they were finished

she removed the jars, tightening the lids firmly and setting them aside

to cool while she prepared another container full. Meanwhile I was

sorting clean berries.

We had enough from that day's work to eat a berry pie every Sunday till the next summer.

I still use a water-bath canner to preserve fruit, including grape juice and tomatoes.

The

tomatoes are cleaned, skinned after a parboil, and packed in their own

juice made by shaking each full jar till it has liquid to an inch from

the top. Tomato juice is easier to prepare using a Champion

juicer. But we learned the hard way that the juicer grinds up

grape seeds, giving the juice a bitter taste. So we use a steam

juicer (pictured above) for our grapes, pears, and apples.

The

tomatoes are cleaned, skinned after a parboil, and packed in their own

juice made by shaking each full jar till it has liquid to an inch from

the top. Tomato juice is easier to prepare using a Champion

juicer. But we learned the hard way that the juicer grinds up

grape seeds, giving the juice a bitter taste. So we use a steam

juicer (pictured above) for our grapes, pears, and apples.

Of course, to can non-acid

foods one needs a pressure canner. Although I grew up eating corn

and beans canned in a water-bath canner, the experts no longer advise

it. Today, I think, most just freeze these vegetables.

Errol Hess is the author of Hunting Pennies, a memoir in verse about his Appalachian childhood.

After dancing, Kayla and I headed over to Heartwood

to peruse some Appalachian crafts (and to eat some lunch). But we got

sidetracked on the way by a sign bound to tug any homesteader astray:

"Plant sale."

The Virginia Highlands

Community College has a large greenhouse system, and they were taking

advantage of visitors attending the Virginia Highlands Festival

to show off their space (and to move a few plants to new homes). At 25

to 50 cents per plant, I splurged on about a dozen broccoli and brussels

sprouts to add a bit of security to my own tardy plantings, and Kayla

picked out some fall greens and flowers.

But the most intriguing feature of the greenhouse wasn't for sale. Instead, a large aquaponics

setup was filled with huge koi living happily in water filtered through

the growing medium beneath a slew of plants. Granted, both fish and

greenery were purely ornamental, but it was still intriguing to finally

see an aquaponics system in action.

And that --- plus some

chocolate --- filled up our girl's day out to the brim. Kayla called it a

once-in-a-lifetime experience. Do you think that means she's never

getting in the car with me again?

We plant some of our fall crops

in June (brussels sprouts, cabbage, broccoli) and July (carrots, peas).

But August is really the make-or-break month for our fall garden. This

is when I decide which beds are going to be seeded in oats or oilseed radishes

and taken out of commission for the rest of the year, and which will

instead feed us lettuce and leafy greens all fall and winter, along with

slowly bulking up garlic and potato onion bulbs for next spring.

My August goal is always to have the entire garden planted in something

by the end of the month. That might be lingering summer vegetables

(sometimes with cover crops interplanted for fall), buckwheat to hold

the ground for later plantings, fall cover crops, or the first tender

shoots of autumn vegetables. There's no place for weed patches in our

fall garden!

Once the August planting

push is done, the garden slowly begins to calm down. While the landscape

remains vibrant, there's less work after everything's planted and

mulched, and Mark and I start thinking of our fall vacation. We're

planning a staycation

this year, probably in late September or early October. It's nice to

have a carrot to dangle in front of our noses when the sun pounds down

on our heads and the garden threatens to eat us alive (rather than vice

versa). We hope to visit Bristol Caverns, go on a hike, and generally

rest and relax. I can hardly wait!

I installed a quick connect battery tender snap cord on the ATV to make trickle charging more of a daily event instead of whenever we need it.

What do you do if you're harvesting two or three gallons of okra per week for a family of two? Freeze some for the winter, then try a new recipe to boost your current consumption, of course.

My movie-star neighbor

suggested a technique he calls blackened okra. He recommends starting

with your biggest cast-iron skillet, but I instead opted for an even

bigger stainless-steel skillet so we'd be sure to produce enough to

serve three. I sliced the okra into rounds, placed them one layer deep

on the oiled skillet, then cooked over medium-low heat for about an

hour. I turned up the heat for the last fifteen minutes and stirred

some, but didn't stir earlier since the goal is to drive off moisture

(to prevent sliminess).

Honestly, I think I could

have cooked the okra a little longer/hotter, because it ended up

browned instead of blackened. It was quite good, though, and half a

gallon was quickly consumed by me, Joey, and Mark, with requests for

more. Definitely a good start on using up all of that okra, but if

you've got an even better recipe I'd love to hear it!

The Scarlet

Runner Beans are probably the most ornamental looking crop we have

in the garden this Summer.

One of my favorite parts

of goatkeeping (combined with our too-small pastures) is that our herd

prompts me to wander in the woods on a regular basis. On previous

summers, I've usually figured I'm too busy to go on extra walks, but our

goats have taught me that there's always time for a good ramble.

During the week, we just

spend an hour in the evening hanging out within a short distance of the

coop. I read and relax while the goats browse. But on the weekends, I

often like to explore...even if that means we end up in parts of the

woods that are so deer browsed that they're nearly barren from a goat

point of view.

(Note to self --- I

definitely need to buckle down on the hunting this fall. The deer have

been staying out of our garden, but their populations appear to be very

high this year.)

Ah, this spot looks much more goat friendly.

There's nothing like a

pair of goats to make a bipedal human feel even more ungainly than

usual. Our darling does prance across deadfalls like this in a heartbeat

while I slowly pick my way through the trip hazard with much more care.

Of course, I shouldn't be

surprised at their agility since the girls have been practicing on

their balance beams for most of the summer. In case you can't tell,

Abigail is repeatedly headbutting that tree in front of her while

staying steady atop the log despite her trailing leash. Ah, to be a

goat.

Top

finds of the day Sunday included a small patch of goldenseal that I

likely couldn't pinpoint again and a couple of blooming downy

rattlesnake plantain (a relatively inconspicuous orchid). Plus some extra peace and joy to hoard for the busy week ahead.

Top

finds of the day Sunday included a small patch of goldenseal that I

likely couldn't pinpoint again and a couple of blooming downy

rattlesnake plantain (a relatively inconspicuous orchid). Plus some extra peace and joy to hoard for the busy week ahead.

Thanks for the boost, Abigail and Artemesia!

Three large straw bales seems

to be right at the ATV load limit.

It was dry enough today to get in several trips before the dashboard

started showing a temperature warning light.

We've eaten our way through 2.5 plantings

of sweet corn, with three plantings left to mature before the frost.

The final beds are right outside our front door, so I walk by them

multiple times a day and watch their growth the way you'd watch sand

slip through an hourglass. The first freeze seems remarkably close when

measured by the height of sweet corn!

Elsewhere in the garden, I'm also shifting gears with winter in mind. A week ago, my gut said that it was time to stop pruning the tomatoes

because blight had spread so much that I had to remove every leaf if I

wanted to eradicate all signs of the problematic fungi. It turns out

that was a good call --- even with blight (mostly septoria leaf spot)

throughout the plants' foliage, our plants matured more tomatoes than

the previous week due to their extra leaf area. It looks like we'll

reach quota on soup this year after all. Phew!

Our new immersion

hand blender makes mixing basil into soup easy and fun.

What I really like is the

easy clean up compared to a traditional blender.

One of our new crops this year is Mammoth mangels,

a kind of fodder beet often grown for livestock. In our case, we're

hopeful the roots will supplement our milk goat's diet during the winter

months. I only planted one bed, though, since I wasn't sure whether

Abigail would actually eat the offering and also wasn't sure how well

the fodder beets would grow in our garden. With new crops, it always

makes sense to start small!

I'd been ignoring our mangel bed all summer, actually. But when I dropped by to weed the bed, I realized that forgetting to thin our plants this spring

meant some roots would be best harvested early. So when I went ahead

and pulled the largest plants and will hope that the smaller mangels

left behind will still have time to bulk up this fall. I ended up with

about half a bushel of thinnings --- pretty impressive from about nine

square feet of growing area!

Mangels are reputed to be a high-quality feed for ruminants,

but there are a couple of reasons why the crop has fallen out of favor.

First is the thinning problem. Like their relative Swiss chard, each

mangel "seed" is really a cluster of seeds. So you nearly always end up

with two or three plants in each spot, meaning you absolutely have to

hand thin. As I learned, if your seeds germinate well and you don't

thin, mangels won't thrive since they're too close together. On the

other hand, if you have so-so germination and forget to thin, the plants

can still grow quite large even without thinning.

The other potential issue

with mangels is that they can cause scouring (diarrhea) if fed in large

quantities to ruminants. Johnny's (the source of our seeds) reports

that small roots of our variety can be fed to livestock immediately, but

that it's safer to wait at least a month before feeding larger roots.

So I'll try a few of the fingerling mangels on Abigail today and will

sock away the larger roots in the crisper drawer of our fridge, which

has been halfway emptied after the huge influx of carrots this spring

made their way into our goat's mouth. It looks like goat-feed season is

shifting from orange to red roots --- I hope Abigail enjoys the mangels

as much as the more labor-intensive carrots!

Rule number one of goathood: The grass is always greener

just out of reach. For the record, I took this photo five minutes after

tethering our herd for the day, and there was millet exactly like the

plants Artemesia was straining after within easy reach. Apparently that

bite just beyond her rope looked much tastier, though.

Actually, I debated

letting our girls chow down on the millet leaves (having originally

tethered the herd in that spot thinking they'd go after the tick-trefoil

instead). The trouble is that warm season grasses can produce hydrogen cyanide when stressed by drought or frost,

and our weather has been relatively dry lately. On the other hand, I've

been irrigating that area weekly if there's not sufficient rain, so I

decided to risk a bit of grazing.

Two

hours after putting the goats back in their pen, though, I went up to

pick blueberries and got concerned when Artemesia didn't meet me at the

gate. I called her name and heard no reply, so quickly put down my bowl

and headed to the coop, terrible images running through my mind.

Two

hours after putting the goats back in their pen, though, I went up to

pick blueberries and got concerned when Artemesia didn't meet me at the

gate. I called her name and heard no reply, so quickly put down my bowl

and headed to the coop, terrible images running through my mind.

Of course, our darling

doeling was simply taking a break, chewing her cud while standing in the

doorway of the starplate coop and gazing out at the world. "Hi!" she

called as soon as I came into view. "I love you!"

(Yes, this is how I parse Artemesia's numerous bleats. Don't tell me what she's really saying --- I don't want to know.)

"No stomach ache?" I asked in response.

"Of course not!" Artemesia replied. "And millet leaves taste even better the second time around!"

For the record, the only weird food that has ever bothered our

iron-tummy goats was when Artemesia drank a whole gallon of mozzarella

whey in one afternoon (whey that Abigail refused to touch). Our

doeling's stomach got a bit bulgy afterwards and her droppings were a

little loose the next day, so now excess whey goes to our dog.

Otherwise, our girls seem to know what is and isn't good for them, and

pearl millet is apparently in the former category.

I'm finally ready to pass judgment on this year's bokashi experiment.

To recap, bokashi is a method of pre-decaying food scraps in an

airtight container with the help of a microbial starter before applying

that proto-compost to the soil. I tried three different versions this

spring --- bokashi using a storebought starter, bokashi using a homemade (lactofermented) starter, and a control bucket with no starter.

I'm finally ready to pass judgment on this year's bokashi experiment.

To recap, bokashi is a method of pre-decaying food scraps in an

airtight container with the help of a microbial starter before applying

that proto-compost to the soil. I tried three different versions this

spring --- bokashi using a storebought starter, bokashi using a homemade (lactofermented) starter, and a control bucket with no starter.

It takes us about a month

for us to fill a five-gallon bucket with food scraps during the

non-preserving season. So I had to space my experiments out, applying

the control to poor pasture soil March 17, digging in the lactofermented

scraps on May 8, and the traditional bokashi on June 6. The photos to

the left show that digging up those three patches in the middle of

August resulted in a time-lapse image of decomposition, suggesting that

neither type of bokashi sped up decomposition much, if at all.

Would I recommend bokashi to anyone? Well, the air-tight buckets

were a nice way to consolidate lots of foods scraps, and the bokashi

starter did cut down on bad odors when opening the bucket...although the

starter became much less effective once the true heat of summer hit.

But I don't feel like the method is really worth the expense unless you

live in an air-conditioned apartment and have to hoard your scraps for a

long time before use. Instead, our food scraps have been hitting the

outside compost pile this summer, where I think we'll get just as much

fertility with much less work (and no outlay of cash). It looks like

bokashi isn't for us.

This has been a bad year for caterpillars on fruit trees. First came the fall webworms, who ate through leaves like nobody's business. And this month the yellow-necked caterpillars hit one of my dwarf apple trees.

This has been a bad year for caterpillars on fruit trees. First came the fall webworms, who ate through leaves like nobody's business. And this month the yellow-necked caterpillars hit one of my dwarf apple trees.

I'm not used to worrying about caterpillars other than cabbageworms, actually. We have so many wild predators

--- like wasps and birds --- that most infestations are gone in short

order. But ignoring the issue didn't make it disappear in either case

this year, so I resorted to hand picking.

As you can see in the

photo to the right, I should have picked a little sooner. I only found

about a dozen caterpillars in our apple tree, but they were all big and

fat after eating about a third of the available leaves. Luckily, the

nibblers died quickly when dropped in a jar of plain water --- problem

solved!

We had a small deer incursion last week that seems to have been thwarted thanks to this mechanical deer deterrent and the metallic noises it makes..

Want a summery side-dish

treat? Pick some firm tomatoes (romas are a good bet, or slicers that

are pink instead of red), slice each one, then cook the slices in a

medium-heat, greased skillet until the bottom begins to turn orange-red

instead of pink-red. Flip your tomatoes over and top each with a thin

slice of homemade mozzarella,

a sprinkle of salt and pepper, and a little grated parmesan. Put on the

lid and cook some more, just until the cheese melts. Delicious!

And now I need to make more mozzarella....

Joey dropped off some pears that

were improved with a little Excalibur

drying.

I broke a few cheap apple slicers before I upgraded to the best

apple cutter.

We've used it a lot over the last 4 years and it will most likely last

another 400.

"Is the below (more or less) the formula for planning on when to plant for our Persephone date?

"Or do you just have a chart already made up that you would be willing to let me try?

"Or do you just have a chart already made up that you would be willing to let me try?"My garden space is ready and waiting, and I still have a lot of good seeds."

--- Jeannette, zone 7, east Tennessee on a gentle southeast slope of a mountain

Jeannette, I've been

getting lots of fall-gardening questions lately, so I thought I'd answer

yours in a post instead of via email. Persephone Days

are most relevant for people who garden in a mild climate, in a

greenhouse, or are growing hardy leaf crops like kale and lettuce. The

date tells you when these cut-and-come-again crops will stop producing

due to lack of sunlight, but it doesn't take into account killing

freezes that will completely wipe out your crops. Broccoli, for example,

is going to kick the bucket at 25 degrees Fahrenheit unless you cover

it well, so the Persephone Date (which comes much later than the

hard-freeze date for most of us) is irrelevant.

My favorite chart for fall planting is here, and I give you lots more information about how to choose planting dates and how to make easy frost-protection in my book Weekend Homesteader.

The short version is --- it's too late for you to plant carrots,

cabbages, and broccoli from seed, but you can still have a great fall

garden with leafy greens (kale is our special favorite) and lettuce,

which grow much faster than other fall vegetables. If you buy big sets,

you might also get away with planting out brussels sprouts, cabbage, and

broccoli now since you live further south than we do. We don't like

radishes, but I believe they're pretty fast so planting another round of

those as well as some turnips could fill in the gaps. Just be sure to

check the days-to-maturity date on your packets and add two weeks for

safety --- some varieties grow much faster than others!

I hope that helps, and

good luck with your fall garden. I always feel like I get more food for

my effort with the fall garden than at any other time of year, so it's

definitely worth figuring out.

We harvested 38 healthy sized

butternut

squashes today.

There's still a whole lot

more that needs another week or two on the vine.

Monday is usually the day

to catch up on pressing issues that caught my eye over the weekend.

This week, that meant harvest, harvest, harvest!

In addition to picking the butternuts Mark posted about yesterday,

I froze just shy of three quarts of tomatoes and basil, picked some

mung and scarlet runner beans, and served us fresh berries and blackened okra

with our lunch. We're now up to 18 gallons of veggies in the freezer,

which is a little less than we'd put away at this time last year but

which is still on track for socking away our winter stores in a timely

manner.

There are few more satisfying times of the year for a gardener than preservation season. Don't forget to enjoy the bounty!

How does Abigail like small mangels that were recently harvested?

She hates them!

We're hoping maybe a month of

curing will make them more delicious.

Now's a good time to go

out and look at experimental crops to see if they're worth growing next

year. I started out my exploration by tethering Abigail between our

little patch of Tithonia diversifolia

and a big patch of weeds. Since Tithonia was meant to be a

cover-crop/goat-fodder-crop, I didn't give the cuttings the TLC I

usually offer this spring (although I did plant them in a very damp spot

as instructed). Given my neglect, it's no big surprise that only about a

third of the cuttings took off. The other two plants are much smaller,

but you can see our largest Tithonia on the far right side of the photo

above.

Did you also notice how

Abigail has wandered off in the totally opposite direction? She

preferred ragweed, red clover, and plantain within her tether-circle to

the Tithonia, completely ignoring the latter's leaves after one taste.

So while this cover crop clearly has potential in the tropics, I'm going

to have to say it isn't worth babying as cuttings over the winter in a

temperate climate. (At least not if you have spoiled goats like we do.)

Soybeans, in contrast, have proven themselves to be not only a great cover crop

but also a goat favorite. At first, Abigail picked off all of the

high-protein leaves in the patch she was tethered near. But soon our

smart goat learned that if she delved a little deeper, she could

daintily pluck the half-filled pods off the stems instead.

Soybeans, in contrast, have proven themselves to be not only a great cover crop

but also a goat favorite. At first, Abigail picked off all of the

high-protein leaves in the patch she was tethered near. But soon our

smart goat learned that if she delved a little deeper, she could

daintily pluck the half-filled pods off the stems instead.

While you're supposed to cook dried soybeans in some way before feeding them to animals (or people) due to phytates,

our doe seems to love the raw-soybean treat at the endamame stage. I'd

be curious to hear from someone more knowledgable than me. Do you think

phytates in young soybeans are problematic, or are these more like green

beans and snap peas --- pretty harmless and delicious when young?

Artemesia prefers to bend down stalks of Rag Weed so she can reach the top where the leaves are new and tender.

From a biological perspective, I prefer a patchwork-quilt garden.

I don't like actual companion planting because I feel like the

companions always compete with each other. But a bed of one vegetable

surrounded by a bed of four other types of vegetables tends to break

pest and disease cycles and also promote pollination (especially if you

slip in a buckwheat or flower bed here and there).

On the other hand, there are issues with the patchwork-quilt approach. Watering can be tricky if you use overhead irrigation, so I already pull my tomatoes out to live in their own dry patch with drip irrigation. Major runners like winter squash and sweet potatoes often fare better if given a compound rather than a single bed since you can let the vines intermingle rather than begging them to stay on their own side of the garden. And I've learned the hard way that it's very difficult to graze goats on an oat cover crop if that grain is next door to overwinterers like garlic and kale that you don't want nibbled.

So I'm setting aside

entire zones of the garden for goat grazing this winter...which means

weeding under the current plants and scattering oat seeds this month.

I've had good luck with this technique in the past amid tall summer

crops like tomatoes and corn, so am pretty confident I can turn the

entire forest and back gardens into goat-forage zones. But there are

only two weeks left to plant if I want the oats to have time to grow

before winter cold sets in. So for the rest of August, oats are a top

priority!

We're still harvesting large bowls of Masai beans on a semi-regular basis.

The fall rains have come.

1.6 inches over the

course of a week is close to average around here. But we'd enjoyed a

couple of dry months this summer, so the returning water feels like both

a relief and a surprise.

Of course, given how wet

it was last winter, our soil never really dried six inches below the

surface. But as a gardener starting fall crops, it's the surface that

counts.

So hauling gets pushed back into the maybe-it'll-dry-again future and

planting takes a front seat. Time to cover the compost piles so those

nutrients don't leach away!

I had to repair the milking

stanchion again today.

Our girls can be rough when

they want to be. The damage usually happens when they fight each other

for what treats are left after milking.

Last year, our hazelnuts weren't ready to pick until early September.

But when I was weeding around the bush on Friday, I noticed a few

clusters had fallen to the ground, and several of those nuts were gnawed

open on one end. That's a classic dining pattern for flying squirrels, so I figured I'd better bring in any nuts that were ready ASAP!

Our hazelnut bush is now

six years old, and this is our first significant harvest. After a little

handpicking, I realized that the easiest method was to clear away the

few weeds that had grown up through the cardboard beneath the bush, then

to shake each limb vigorously. About half of the nuts dropped and were

easy to pluck off the ground. I'll go back next week to try to beat the

squirrels to the remaining clusters.

(Look who joined me in my harvest morning --- a beautiful katydid!)

Back at the trailer, I

decided to dehull the nuts right away. Really, I would have been better

off waiting for the hulls to dry since some required prying action to

get the leafy lobes apart. But it's been so wet that I was afraid the

nuts would mold in their shells, so I went ahead and dehulled, ending up

with about a cup of hazels in the shell for this first batch. Not a

whole lot, but pretty exciting since we only got five hazelnuts total

last year!

Meanwhile, back in the

garden, our bush has already created proto-flowers to produce next

year's nuts, as you can see if you look closely at the photo above.

Except for the multi-year wait for the first harvest and the possible

squirrel problem, hybrid hazels seem to be an excellent low-work food plant. I'm glad we set out three extra bushes last fall!

The glue

repair I did on Anna's sandals only lasted a few months.

I talked her into buying a

replacement pair, but the new design had a problem staying fastened.

So far two zip ties locking

down the front strap seems to be the solution.

One of my favorite things about having a traditional compost pile this year is that it makes it simple to use up all that high-nitrogen urine

that often goes to waste on our farm. I figure about half our pee has

made it onto the piles this summer, which has probably pushed the

compost a little on the higher nitrogen side than was optimal.

How can I tell? When I forked through one pile to consolidate it with another, I found lots of black soldier fly larvae.

These grubs usually show up in compost that's not quite optimally

balanced, and they mean I probably should have added some extra ragweed

or other carbon source to even things out.

On the plus side, the pee

has made our compost piles decompose fast. Our two oldest piles, now

merged into one, are in their final cooking stage, covered by plastic to

keep excess rain at bay. I figure the summer's weeds (and pee) will

result in maybe two to three wheelbarrows full of compost when all's

said and done, or approximately 5% of the vegetable garden's needs for

the year. Yes, it's a drop in the bucket, but a satisfying one!

We've been getting our garlic ready

for Winter storage.

I can't remember the last

time we bought garlic at the store.

The world is green, the grass is lush...and now's the time to stock up on hay for the winter. But how much will we need?

You'd think that my relentless recordkeeping would have the answer to

that question since we've already enjoyed one winter with goats. But we

bought hay a bit at a time last year, and I have just a vague memory of

using two bales per week for our herd of two during the peak of winter's

cold. That was before we lowered our hay-wastage with a better manger,

and I don't have solid estimates on hay usage during the shoulder

seasons, though. So I'm not really sure how many bales we went through

in the end and how that will relate to years to come.

Luckily, the internet is

always willing to come to the rescue. Various websites suggest that a

full-size goat will eat about 5 pounds of hay

per day and a dwarf will eat about 3 pounds per day. Since our goats are

semi-dwarfs and I figure we have to feed them hay for about 6 months

out of the year, I'm guessing we might need about 29 bales (roughly 50

pounds apiece, $6.50 per bale from the feed store).

On the other hand, good

hay is much easier to find at this time of year than if you run out in

March, so I'd really like to have more like 40 bales on hand for

safety's sake. We've learned that our kidding stall holds 27 bales...but

that the girls like to nibble down the edges (far more fun than eating

out of the manger), bringing the actual stored total closer to 25 bales.

Time to find a dry, accessible place to store another 15 bales of hay!

We had some more deer damage

that's starting to threaten our Fall garden.

I dug out the trail

camera, didn't have batteries but noticed an external power hole,

found a universal plug, selected the proper voltage and turned it on.

The screen powered up, but then went blank with a slight burning smell.

I'm pretty sure I got the polarity wrong on the plug and burned it

out.....Ouch.....

I kept hearing good things about The Market Gardener

by Jean-Martin Fortier, but I put off picking the book up because I

have no inclination to sell any of our homegrown food. Having now

consumed this easy-to-read and gorgeously illustrated text, I now

recommend it to just about every reader on this blog. If you're

interested in producing food for a CSA or farmer's market, the book is a

no-brainer. But it's also invaluable for intermediate-level home

gardeners who want to streamline their production by focusing on

techniques that really work.

I kept hearing good things about The Market Gardener

by Jean-Martin Fortier, but I put off picking the book up because I

have no inclination to sell any of our homegrown food. Having now

consumed this easy-to-read and gorgeously illustrated text, I now

recommend it to just about every reader on this blog. If you're

interested in producing food for a CSA or farmer's market, the book is a

no-brainer. But it's also invaluable for intermediate-level home

gardeners who want to streamline their production by focusing on

techniques that really work.

Fortier's thesis is

simple --- those of us gardening or farming on less than two acres need

to minimize our startup costs, to focus on hand tools and light power

tools, and to plan for high productivity in a small space using

intensive methodology and season extension. He explains that you can

expect to net between $30,000 and $50,000 per acre per year by working

(long hours) for ten months selling directly to the public. His CSA,

located in zone 5 of Quebec, for example, feeds 200 customers off 1.5

acres and pays his family's bills while also employing 3.5 workers in

the process.

I won't go deeper into

Fortier's methodology because the book is such a delight to read with

its extensive drawings and short, punchy chapters that you're really

better off going straight to the source. However, you probably will hear more about caterpillar tunnels here in later posts since The Market Gardener explained just the method I think I've been looking for to protect crops a bit more than quick hoops

do, but without the permanence and expense of high tunnels or a

greenhouse. So stay tuned to follow along with our experimentation in

that direction this fall!

I started a Film and Video class at ETSU today and will not be making a blog post on Tuesdays and Thursdays till December.

It's not as if I go

hunting song sparrow nests throughout our yard. But I seem to have found

each of our resident pair's nurseries this year.

The newest eggs are secreted away amid the raspberry canes, which I think will be a safer location than round two in the tomatoes.

Because I'm pretty sure that my tomato-leaf pruning opened up the

former nest too much and allowed a cowbird to lay one or more parasite

eggs, which is probably one I found a chick pushed out of the nest and

another disappeared days later.

Here's hoping three's the charm for our sparrows and Mama Bird will have a more successful hatch this time around.

We picked up our new Fall

chicks today.

The Post Office always calls

us as soon as they arrive off the truck.

Lucy never gets tired of

smelling a new poop filled box.

This year, our garden has

subsisted on 95% homegrown manure. This was more of an access issue

than a planned experiment, so I ended up behind and unable to compost

the bedding before application. I needed that fertility now rather than later.

As you might expect, my

results have been affected by that shortcut --- I figure we're at about

75% productivity compared to previous years when I fed the garden well-composted horse manure.

But we're finally caught up, so winter bedding will be composted and

hopefully next year we'll be back up to speed. And, just think,

homegrown manure means 70% less hauling work, 80% fewer weed invasions,

and 100% more control --- a definite long-term plus for our farm!

Interestingly, there have

been some areas in which the uncomposted goat bedding trumped

well-composted horse manure. My plan over the summer has been to apply

the goat bedding two weeks to one month before planting to ensure there

wouldn't be any seedling burn from fresh urine and goat berries. Then,

if I was planting something large (like sweet corn), I raked back the

manurey straw when I was ready to make planting furrows. If I was

planting something smaller like carrots, I raked all of the bedding to

the side of the bed, to be pulled back up around seedlings once they

sprouted.

The photo above shows two

beds planted with carrots on the same day. The bed on the right was

topdressed with the last of my stockpiled, well-rotted horse manure. The

bed on the left was treated as explained in the last paragraph with

goat bedding. I had almost zero germination in the horse manure bed,

which has been a common problem in previous years when getting the fall

garden going --- small seeds fail to sprout during dry spells, despite

what seems to be sufficient irrigation. So perhaps putting horse-manure

compost on the surface was the issue all along. I assume the compost

sucked up water and made the beds drier on the surface since the bed

next door sprouted quite well. In contrast, goat manure on top of the

soil kept the ground moist until planting day, then didn't get in the

way of seedling germination since I raked the straw to one side.

For new annuals, it's

pretty easy to incorporate a waiting step between bedding application

and plant growth. But what about when fertilizing perennials who are

already in place? I was a bit leery when topdressing fresh goat bedding around our strawberries and asparagus, but I ended up seeing fewer issues than expected. The strawberries, actually had no

complaints, presumably since there was already a layer of straw beneath

the goat bedding to sop up any high-nitrogen effluent that floated down

toward the ground. The asparagus was a bit less pleased, with the

youngest fronts showing wilting of the top four inches or so, a clear

sign of nitrogen burn.

Since my test asparagus

beds showed issues with the straight goat bedding, I'm now trying out

plan B on my other asparagus planting. I laid down a section of

newspaper (for weed control), then a healthy layer of fresh straw (to

buffer the nitrogen), then Mark and I scattered chicken manure from the

spring brooder lightly over top. Hopefully the nitrogen will be more

asparagus-friendly by the time it reaches the asparagus root zone this

time around.

The other good news on

the manure front is that most of our garden soil is now so good that

we're moving out of the renovation stage and into the maintenance stage,

meaning that some crops don't need pre-planting doses of manure at all.

We no longer feed our beans or peas, and in certain beds I also skip

feeding before planting leafy greens. I'm actually starting to imagine a

time when the composted manure from two goats, a flock of layers and an

annual round of broilers, plus the contributions of our composting

toilet will provide more fertility than our farm needs. What a change

from the eroded soil that required truckloads of manure before anything

would grow at all!

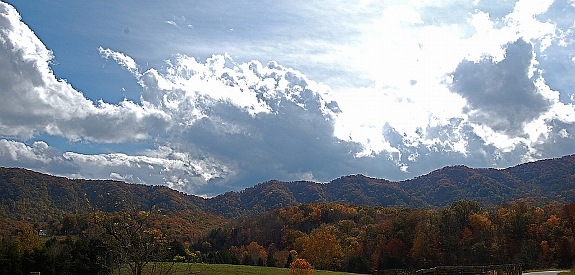

Do you want a beautiful, isolated homestead with the world's best

neighbors? Two friends of mine --- Steve and Maxine --- are selling 90

acres and a house for $225,000. If that's too much for you to handle,

they're also willing to split the land apart into two parcels, like so:

- House + 5.4 acres --- $123,000 (Includes fields, woods, pond, spring and fenced yard)

- 85 forested acres --- $102,000 (Heavily forested land above house to top of Clinch Mountain)

This property belonged to Maxine's mother and is a quarter of a mile from Steve and Maxine's beautiful homestead.

Having neighbors who've homesteaded for as long as I've been alive is

an invaluable resource that should really be factored into the already

low price tag. And even though I can't promise they'll teach you

everything they know, I have a feeling the couple would quickly take

anyone with an interest in farming under their wings. (They're some of

the nicest people I know, are very interested in folks of all shapes,

colors, and creeds, and are much less introverted than I am.)

The location is on the Clinch Mountain in Snowflake, Scott County,

Virginia, a ten or fifteen minute drive from Gate City and less than

half an hour from Kingsport (one of the towns we consider "the big

city"). If you're planning on working in the area, chances are you'll be

looking in Kingsport or Johnson City, and these towns are also good

spots for shopping and entertainment.

Land features:

- Land extends to the top of the Clinch Mountain

- Pristine forest with old-growth trees, abundant birds and

wildlife, rare and endangered plant species. (Editorial note from me:

This is a truly beautiful forest! Very steep, though, so you'll be in

good shape if you go walking.)

- Conservation easement on forested acres – protecting forest, mountain springs & reservoir (water supply for the house). This covers Steve and Maxine's property as well, so you won't suddenly be next door to a subdivision or a clearcut no matter how the land changes hands. The easement agreement is available upon request.

- Three mown fields totaling about 1 acre in combined size – could be grazed or converted to garden space

- Pond & dock

- Private road

- Fenced yard w/electric gate

House features:

- 6 rooms, 2 bedrooms, 2 baths (1,164 sq. ft.)

- Custom-built manufactured home (standard building materials)

- Contractor-built large front porch and one-car garage

- Red cedar siding

- Hand-laid field stone over permanent block foundation

- 30/yr shingles on roof (reroofed about 10 years ago)

- 10” fiberglass insulation overhead; 4” fiberglass in walls and under floors

- Heat Pump – relatively new Carrier w/digital thermostat

- Windows – double glazed w/tilt-in feature for cleaning

- Handicap assessable 36” doorways

- Vaulted ceilings w/ceiling fans

- Sheetrock walls/ceilings throughout

- Hardwood floors in living room, dining room, hall and closets

- High-end major appliances – stack washer/dryer, glass-top stove, large refrigerator

- Tiled kitchen counter; oak cabinets

- Bathroom #1 - Tiled floor w/ large tile and glass walk-in shower

- Bathroom #2 – bathtub and stall shower

- Porcelain sinks & commodes in bathrooms

- High-speed internet access

At only $1,200 per acre for the non-house portion, this property is a great deal (and if you get the house, it's move-in ready). So if you're looking for an inexpensive homestead in an area that I consider one of the most beautiful in the world, this might just be it!

We got the lumber needed for

wood shed 2.0 staged today.

Having trouble finding

roofing tin in our local area for some unknown reason.

It sounds like you and I

are on the same wavelength, Deb. Mark and I weren't very impressed with

the Cornish Cross we raised last year. Yes, they were economical, but they barely foraged and I felt their meat was only slightly superior to store-bought.

We've raised Australorps as broilers in the past

and felt like their meat was extremely nutritious. But dogs and ducks

and other problems meant we didn't have a large enough flock to hatch

our own eggs this year. And when I pondered the hatchery catalog, I

decided that if I was buying broilers, I might as well try something

that would be a bit meatier and (hopefully) more economical. So, like

you, we chose Red Rangers, which we reserved in midsummer for a fall

broiler run.

The previous photo showed

the chicks the day we brought them home from the post office --- they

already looked pretty big and spunky! But the comparison to the photo

above, taken two days later, shows that the baby broilers are also

growing fast. I plan to let them out on pasture this weekend and will

keep you posted on how they fare.

The goats have been bad again.

Somehow they figured out how

to pull down a hay bale and use it to jump up to the remaining pile of

bales.

Maybe this tarp will keep

them out?

The mercury dropped to 49

this past week, scaring me into thinking fall may be coming along a

little faster than usual. Time to double down on preserving basil (the

tenderest summer crop) and time to make sure the bees are ready for the

winter.

I'll delve into the hives to check on winter stores next week, but for now I started with a varroa mite test.

I expected the news here to be good since splitting and swarming both

lower mite populations dramatically. So I wasn't entirely surprised to

find only 5 mites beneath the daughter hive and 11 beneath the mother

hive after 48 hours. Looks like our high-class bees came through for us

again! (Now, if they'd just make some honey....)

The

rallying cry among those of us who ascribe to voluntary simplicity is

"Things don't make us happy." Why, then, are materialistic habits so

hard to break?

The

rallying cry among those of us who ascribe to voluntary simplicity is

"Things don't make us happy." Why, then, are materialistic habits so

hard to break?

In The How of Happiness, Sonja Lyubomirsky both challenges and supports that rallying cry. She explains that money and possessions do

make us happier...for a little while. If you by a brand new car or

whatever else you've been craving, then your happiness levels receive an

immediate boost. But that boost only lasts for a short period of time,

at which point you tend to drop down to your normal happiness level.

Why? Because humans are

extremely adaptable. Lose a leg, and within a couple of years the

majority of amputees are just as happy as they were pre-surgery. Win the

lottery, and that immediate elation is long gone by the end of twelve

months. Even getting married --- which I've seen in other studies linked

to long-term increases in health and happiness --- is only supposed to

raise you above your own average happiness level for about two years.

These

examples are all types of hedonistic adaptation --- the human tendency

to get used to both positive and negative changes in our lives. The good

news is, you can counteract hedonistic adaptation, drawing out the

positive effects of everything from that new handbag to that new spouse.

These

examples are all types of hedonistic adaptation --- the human tendency

to get used to both positive and negative changes in our lives. The good

news is, you can counteract hedonistic adaptation, drawing out the

positive effects of everything from that new handbag to that new spouse.

It takes conscious effort

to extend the honeymoon period so you can keep savoring and

appreciating the wonder of having fun-loving goats and cute, cuddly

chicks on your farm, but the project is definitely worth the time.

Similarly, if you've got some money to spend and want to go out and buy

something new to make you happy, try selecting experiences instead of

physical objects, and do so in small doses spread throughout the year

rather than in one big chunk.

Or just be aware of your own tendency toward hedonistic adaptation and

ask yourself --- "how long will that new wardrobe make me happy, and is

that short boost in mood worth the expense?" The awareness just might be

enough to help you achieve your goal of voluntary simplicity.

We got our final set of 9 hay

bales hauled in today.

The Star Plate barn is full

to the brim so these bales will go in the barn.

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.