archives for 07/2015

About a month ago, I grafted named varieties onto our seedling American persimmons.

I used two different techniques, whip grafting the hard-to-get-to

plants up in the powerline pasture and bark grafting the more accessible

plants where our pullets and cockerels are currently grazing. Since I'm

a lazy farmer whenever possible, I'd only been watching the accessible

plants, and was disappointed to see that one piece of scionwood had

broken off and that the other two pieces of scionwood showed no signs of

life.

About a month ago, I grafted named varieties onto our seedling American persimmons.

I used two different techniques, whip grafting the hard-to-get-to

plants up in the powerline pasture and bark grafting the more accessible

plants where our pullets and cockerels are currently grazing. Since I'm

a lazy farmer whenever possible, I'd only been watching the accessible

plants, and was disappointed to see that one piece of scionwood had

broken off and that the other two pieces of scionwood showed no signs of

life.

But when the weeds in the

powerline pasture got tall enough to make it worthwhile to tether our

goats up on the hill, I brought along the camera and took a look at the

whip-grafted persimmons. The result? 75% success, which is pretty

awesome for this notoriously difficult-to-graft species!

Now,

if only I hadn't tethered Artemesia quite so close the the Yates

persimmon, bringing my success rate on that hillside back down to

50%....

Now,

if only I hadn't tethered Artemesia quite so close the the Yates

persimmon, bringing my success rate on that hillside back down to

50%....

On the plus side, I still

have hopes that some more of the grafted persimmons might sprout from

the scionwood later this summer. After all, the scionwood on three trees

looks good...just seemingly dormant. But if I was going to repeat my

endeavor, based on this data, I'd go entirely for whip grafts in the

future.

Since it looks like all

of the seedling rootstock is still alive, I should get a second chance

on those trees, snipping scionwood off the successful grafts and adding

them to the unsuccessful trees next spring. In the meantime, I'll be

babying our successful grafts and hoping for fruits as early as

2018...if Artemesia keeps her mouth to herself.

I usually clean out the wood

chips on our Oregon

battery powered chainsaw with a nearby twig, but a small paintbrush

gets the job done faster and cleaner.

Two bungee cord straps on the

chainsaw handlebar keeps the brush handy.

If the brush had a flat head

screwdriver as part of the handle it would make tightening the chain in

the field easier.

Both the basswood and the

sourwood are blooming right now, so the hives are hopping. Which means

it's time to look inside and make sure there's enough space for the bees

to sock away all that honey.

You may recall that our mother hive has been weakened twice this year. First, I took a swarm-prevention split, then the hive swarmed anyway.

And yet, despite losing all of those workers (and me not finding a

second feeder to boost their stores with sugar water), there's quite a

bit of capped honey in the hive. The top box (a Warre box above a hive converter,

which was the original box in this hive) seems to be about half full of

honey and half full of capped brood. The next box down (a Langstroth

super) is similarly full. And the final box (another Langstroth super)

is full of drawn comb with some honey already stored therein.

I took the hive all the

way apart for two reasons. First, I was hoping to be able to take off

the Warre box and call the conversion a success. Unfortunately, there's

still brood in the Warre box, so I'll have to wait on finishing our

conversion.

My second reason was to

hunt for eggs, to see whether the newly hatched queen had begun to lay.

It's really too early to expect a virgin queen to have mated and started

to lay, though. And, sure enough, the only brood I found was capped

(some of which was hatching, like in the photo at the very top of this

post). So I'll have to wait there as well to see whether the new hive

has produced a successful queen.

However, I did use the

intrusion to good effect in the end. Since I had the hive entirely

dismantled, I took the opportunity to add another empty super, although I

put it at the very bottom in the Warre manner. Hopefully that will give

the bees room to continue drawing comb and socking away the massive

amounts of nectar that seem to be winging into the apiary this week.

After all, I can hear the bees flying from the back porch, about 150

feet away, so I know they're working hard!

Meanwhile, the daughter

hive (from an early June split) is much less populous, but seems to be

doing quite well nonetheless. The top box is very heavy with honey and

brood, while the bottom box is fully drawn but appears mostly empty.

It's much harder to delve into a Warre hive in search of queen signs,

but the presence of brood four weeks after the split suggests that there

is a queen present and hard at work doing what she does best ---

expanding the hive.

I put the daughter hive back together as-is and left the bees to their

colony chores. Except for sugar water for the daughter hive, the apiary

should take care of itself for a few weeks now.

Our goats have already broken

their first mineral feeder trays.

These new 6

quart feeders are made of

thick Dura-Flex plastic.

I added some large washers in

case Abigail tries to step into one again.

In

our garden, it's always a case of good news/bad news. Good news: we

started eating our first tomatoes (Jasper) this week and there is

technically still no blight in the patch. Bad news: septoria leaf spot has reared its ugly head and required me to snip off half the plants' leaves anyway.

In

our garden, it's always a case of good news/bad news. Good news: we

started eating our first tomatoes (Jasper) this week and there is

technically still no blight in the patch. Bad news: septoria leaf spot has reared its ugly head and required me to snip off half the plants' leaves anyway.

Although not a blight by

name, septoria leaf spot is a fungal disease of tomatoes (making it a

blight in my book). In our garden, septoria is usually the first such

disease to appear, and it seems to weaken the plants sufficiently to let

the other fungi get a toehold. But maybe this year our blight-resistant varieties will come through and septoria will be our only fungal problem. Only time will tell.

(As a side note, I feel

dumb/condescending typing this, but several of you have asked me about

our blight-resistant tomato varieties despite me linking copiously in my

posts. If you follow the link above, you can read much more about them.

And, in general, if you follow the links in my posts, you'll learn more

about the topics in question. And now I'll end my quick course in

Web-browsing 101....after an apology for insulting your intelligence!)

Back to the point, you

can see our tomatoes in the background of the photo above. The plants

look a little naked now with their bottom leaves all gone, but I'm

hoping the serious pruning will slow down fungal spread despite a rainy

week.

In

the foreground are happy, healthy butternuts, thriving and setting

fruit in what will probably be next year's tomato patch. Like cabbages,

squashes are such a joy in the garden simply because they grow so

vigorously that they make me feel like a pro. Honestly, though, other

than feeding the soil with a bunch of chicken bedding a few months

before planting then mulching the emerging vines, I've done nothing to

those plants. Cucurbits, unlike tomatoes, require very little babying in

our climate to party all the way across the aisles and into the next

beds. I love our naughty butternuts!

In

the foreground are happy, healthy butternuts, thriving and setting

fruit in what will probably be next year's tomato patch. Like cabbages,

squashes are such a joy in the garden simply because they grow so

vigorously that they make me feel like a pro. Honestly, though, other

than feeding the soil with a bunch of chicken bedding a few months

before planting then mulching the emerging vines, I've done nothing to

those plants. Cucurbits, unlike tomatoes, require very little babying in

our climate to party all the way across the aisles and into the next

beds. I love our naughty butternuts!

Abigail found a weak spot on

the milking

stanchion neck brace and

nearly worked one of the side panels free.

Two brackets made it feel

more stable.

Sometimes I get so deeply focused on tomato blight or persimmon grafting

that I forget to show you the big-picture garden. So I snuck out

between rain showers Friday to snap some shots of this and that.

June

was weeding month, when I did my best to uproot interlopers between

young vegetable seedlings and then mulched the growing plants left

behind. The task is ongoing, but by the beginning of July I'm officially

ahead of the weeds and can finally breathe a sigh of relief.

June

was weeding month, when I did my best to uproot interlopers between

young vegetable seedlings and then mulched the growing plants left

behind. The task is ongoing, but by the beginning of July I'm officially

ahead of the weeds and can finally breathe a sigh of relief.

We're also eating quite a

few summer vegetables already, making all that weeding worthwhile.

Cucumbers, summer squash, tommy-toe tomatoes, green beans, and Swiss

chard are all making regular appearances on our plates now, with more

contenders still to come.

I also took a bit of time this week to start working on our strawberry beds. Midsummer strawberry tasks include renovating keeper beds,

ripping out old beds, and clipping blooms off any newly bought plants.

These last have been sitting in cold storage since winter, so they think

it's spring when they arrive at our farm. But June blooms in 2015 will mean fewer strawberries in 2016, so I pinch off flowers as they form.

I also took a bit of time this week to start working on our strawberry beds. Midsummer strawberry tasks include renovating keeper beds,

ripping out old beds, and clipping blooms off any newly bought plants.

These last have been sitting in cold storage since winter, so they think

it's spring when they arrive at our farm. But June blooms in 2015 will mean fewer strawberries in 2016, so I pinch off flowers as they form.

The only difference in my

strawberry campaign this year is that I opted to fertilize and mulch

our renovated beds with fresh goat bedding. I hope I don't see burning

and regret this shortcut! I definitely wouldn't apply fresh chicken

bedding around growing plants, but goat bedding seems to be lower in

nitrogen and might make the cut. We'll see....

Speaking of nitrogen, I'm keeping an eye on the two new nitrogen-fixing cover crops

we're trying out this year --- alfalfa (above) and soybeans (to the

left). I'm not sure if alfalfa puts out enough growth to really count as

a cover crop, although the goats adore the leaves. The soybeans are

more intriguing from a garden perspective, since they appear to be

thriving in very poor soil. That's a cover-crop niche I'd been looking

to fill --- what to plant before your earth has been improved enough to

keep buckwheat and oats happy. But it's early days yet, so I'm not ready

to pass judgment on either cover crop right now.

Speaking of nitrogen, I'm keeping an eye on the two new nitrogen-fixing cover crops

we're trying out this year --- alfalfa (above) and soybeans (to the

left). I'm not sure if alfalfa puts out enough growth to really count as

a cover crop, although the goats adore the leaves. The soybeans are

more intriguing from a garden perspective, since they appear to be

thriving in very poor soil. That's a cover-crop niche I'd been looking

to fill --- what to plant before your earth has been improved enough to

keep buckwheat and oats happy. But it's early days yet, so I'm not ready

to pass judgment on either cover crop right now.

On a less utilitarian

note, borage doesn't look like it's going to make the cut as an

Anna-friendly flower. To survive on our farm, flowers have to be able to

thrive with absolutely no care, and our borage seems to be failing. I

could look up the disease and take steps to fix it...but with happy

nasturtiums and zinnias, I see no point in babying a flower.

Scarlet runner beans,

of course, continue to prove themselves to be Anna-friendly flowers.

This area in front of the trailer is entirely subsoil, dug out of a bank

nearby and mounded up into a little bed that partially hides our

skirting. But despite poor soil, the beans are already growing so fast

that I've pulled Mark off other projects to start building them a

trellis.

The bed and trellis were

really meant to house grapevines, three of which are hidden amid the

beans in the photo above. Mark will tell you more about the trellis

soon, I'm sure, but suffice it to say that the eventual goal is to shade

this west-facing window from the hot summer sun.

And that's a quick tour of bits of the garden that caught my eye before it started to rain. Happy Fourth of July!

Anna has been teaching me how

to milk Abigail.

It might take me a while to

learn the hand action and milking machine suction.

It's time for us to cross another goat-keeping hurtle --- breeding our does. I was hoping to do this the lazy way, letting our buckling

mate with our (unrelated) doeling this summer for a fall birth. But

Lamb Chop didn't mature fast enough to do the deed before my

self-imposed deadline, and any matings now would result in kids being

born too late in the season to be safe.

So we've got a bit of

breathing room to figure out a better way to get our does knocked up.

For an early April birth, we'd need to breed our does in early November.

Which seems like a lot of time to make up our minds...but probably

isn't.

There are lots of ways to

find goat sperm, which vary in dependability, safety, and quality.

Honestly, Mark and I would prefer artificial insemination (AI) for our high-class doeling

for reasons of safety and since she's a quality goat whose offspring

could be equally high quality (if dad supplies the right genes). But we

haven't found anyone local who can do goat AI, and driving a few hours

to get our goat bred could be problematic if the first time doesn't

take. (Success rates with frozen semen run about 60% with goats.)

Option 2 is to buy a

liquid nitrogen tank and supplies so we can inseminate on our own. My

understanding is that this would cost about $500 (plus ongoing liquid

nitrogen costs), which seems pretty expensive for goat sex.

Option

3, the simplest and probably cheapest option, is to find a local buck

whom our does can have a date with. The trouble is that I'm working hard

to keep our farm's parasite levels very low, so I wouldn't want a

run-of-the-mill buck sleeping over and spreading his worms. (All goats

have worms, and if you've been deworming your herd monthly the way most

people around here do, those worms are most likely vermicide-resistant

"superbugs." Doesn't sound good, does it?) And the bucks I've heard

about nearby probably won't produce offspring that are worth keeping,

which would be a shame since a daughter of Artemesia's could potentially

be a top-notch goat. The closest milking-quality Dwarf Nigerians or

Mini-Nubians (Artemesia's breed) that I've found so far are a couple of

hours away, which adds another layer of complication to the breeding

endeavor if I want to produce keeper kids.

Option

3, the simplest and probably cheapest option, is to find a local buck

whom our does can have a date with. The trouble is that I'm working hard

to keep our farm's parasite levels very low, so I wouldn't want a

run-of-the-mill buck sleeping over and spreading his worms. (All goats

have worms, and if you've been deworming your herd monthly the way most

people around here do, those worms are most likely vermicide-resistant

"superbugs." Doesn't sound good, does it?) And the bucks I've heard

about nearby probably won't produce offspring that are worth keeping,

which would be a shame since a daughter of Artemesia's could potentially

be a top-notch goat. The closest milking-quality Dwarf Nigerians or

Mini-Nubians (Artemesia's breed) that I've found so far are a couple of

hours away, which adds another layer of complication to the breeding

endeavor if I want to produce keeper kids.

Option 4 is to buy a

buck, presumably one with good genetics and who has a clean bill of

health. The trouble here is that our farm is small and our

infrastructure is minimal, so we wouldn't really have anywhere to keep

him. Granted, if he didn't cost too much, we could simply buy a buck in

the fall, make sure he mates with our does, then eat him, which would

lower the hassle factor dramatically. But high-quality bucks tend to

cost high-quality money, making it less feasible to turn him into

sausage after he breeds with our does. And there's still the parasite

issue to consider.

I'd be curious to hear

from more experienced goatkeepers among you. Is there an option I'm

missing? And, given our goals and infrastructure, which breeding

technique would you choose? I suspect November will be here before we

know it, and it would be great if I had our breeding plans all lined up

before those fall heats.

Our Chicago

Hardy Fig is limping along this year due to a harsh Winter.

Makes me wonder if a support

post might encourage more vertical growth?

My first try with

mozzarella tasted and looked a little funny since I used balsamic

vinegar to acidify the milk. (That was the only acid I had in the

house.) But after a trip to the store to pick up a bottle of lemon

juice, my second attempt came together quite easily. Total time: 30

minutes active, 2 hours total in the kitchen, 3 days wait on the milk.

First of all, Leigh warns not to try to make mozzarella until goat's milk is at least three days old.

So I started a careful milk-aging system in the fridge --- new jars

went in the right side, wrapped around the back, and we drank out of the

jar in the front left. The great part about aging the milk before

turning it into cheese is that I was able to skim off enough cream to

whip as berry topping. Yum!

(Edited to add: I made this later with the cream left in, and I have to

admit that whole mozzarella was tastier than skim mozzarella. So you

might consider skipping the skimming step.)

Okay,

back to the point. I poured eight

cups of three-day-old milk into a stainless-steel pot. Next, I mixed 1/4 cup of lemon juice

(bottled) with one cup of water and poured that mixture into the milk,

stirring well.

Okay,

back to the point. I poured eight

cups of three-day-old milk into a stainless-steel pot. Next, I mixed 1/4 cup of lemon juice

(bottled) with one cup of water and poured that mixture into the milk,

stirring well.

The next step was to warm

the milk to 90 degrees Fahrenheit. My jelly thermometer doesn't go down

that low, so I used the inside-of-your-wrist test that is recommended

for warming water for bread-yeast proofing.

Once the milk was warm, I

mixed 1 drop of liquid rennet into 1/4 cup of cold water. Our raw goat milk requires very little rennet, so I then poured half

of the rennet-water mixture into my acidified milk. In other words, I

ended up only using half a drop of rennet for this recipe, which makes

the mozzarella come out at more the consistency I was looking for than

the harder, chewier cheese resulting from following a recipe.

After mixing the rennet-water into the

acidified milk, I was ready for the first waiting step --- 1 hour for

curds to form.

When you gently tilt your

pot of proto-mozzarella and the clearish whey slides away from the

solid curd, you're ready to move on to the next stage. Use a knife to

cut the curd into squares, then put the pot back on the stove over

medium-low heat.

This is where the candy

thermometer comes into play. Your goal is to achieve a temperature of

105 to 108 degrees Fahrenheit, then to hold your liquid at that

temperature

(stirring every five minutes) for thirty-five minutes. During this time,

the curds will shrivel and clump together to form a substance much more

like mozzarella. Be careful because I feel like overdoing the heat here

makes the mozzarella a little chewier than I would have liked.

Now strain the curds from the whey by passing the contents of your pot through a stainless-steel sieve.

Add 1/4 teaspoon of salt

to the curds, then put them in the microwave (in a microwavable dish)

for between 30 seconds. The mozzarella should melt enough

to be stretched and easily formed into a ball. If not, put it back in

for 15 to 30 seconds before stretching a few times and calling the

cheese done.

The result is about six ounces of cheese from two quarts of milk, with the possibility to get more cheese out of the whey later. All told, mozzarella seems a bit more wasteful of milk than cultured cheeses,

but it's definitely quick and easy. In fact, there's a 30-minute

version knocking around the web that cuts out some of these steps, if you don't mind trading a bit of flavor for time.

What fun to add another homemade cheese to my arsenal!

We put up a new shade

trellis today for grapes and scarlet

runner beans.

The increased shade on these

West facing windows will help to cool the kitchen.

It's

hard not to be intrigued by the shape of carrots when they come out of

the ground twisted or gnarly. For example, the photo to the left (from

our 2009 garden) made me think one carrot was giving his buddy a hug.

It's

hard not to be intrigued by the shape of carrots when they come out of

the ground twisted or gnarly. For example, the photo to the left (from

our 2009 garden) made me think one carrot was giving his buddy a hug.

However, after a while,

most gardeners realize that the goal is long, straight carrots that are

easy to clean and chop. So why, we begin to wonder, are some carrots

fine, upstanding members of our gardening community...while others split

and twist and make trouble?

The answer is usually in

your soil. The carrots in the photo to the left probably should have

been thinned, while the carrots on the right side of the photo at the

top of this post likely hit something hard in the soil and split to grow

around it. Since we don't have any rocks, those were likely tough spots

within the earth itself, a sign that our soil isn't yet perfect.

Luckily, more of our carrots come out of the ground long and straight

every year --- a good sign!

I harvested one of our

beds of spring carrots early this year because the plants were starting

to rot. It's possible the rot is due to our recent bout of wet weather

(2.7 inches in the last week). Perhaps more likely (since only one bed

was affected and the roots are rotting from the tips up) is carrot fly

larvae tunneling down into the roots. I'll probably pull the other three

beds this week just in case.

On the plus side, I

planted twice as many carrots as we needed so Abigail could get off the

storebought-carrot wagon. So I sorted our harvest into straight,

easy-to-handle carrots for the humans and partially rotted or gnarly

carrots for the goats. Even though I had to take care of twice as many

beds in the garden, I think the goats just saved us time overall since I

don't have to scrub those gnarly roots!

Our Stihl

FS-90R weed trimmer is just over 4 years old and still runs great!

The trimmer head needs to be

replaced. I was going to order an after market trimmer head on Amazon

but changed my mind when I saw all the bad reviews.

Better to wait and pay a

little more at a Stihl dealership. My new favorite place to take Stihl

products is the feed store in Gate City.

It's that time of year

again --- when a couple of hours weeding in the garden has the side

effect of bringing home a bigger harvest than we can possibly eat in the

next few days. Our local librarians are going to have to add more

cucumbers and squash to their diets. (We'll keep the carrots.)

The photos above show the

part of the garden I hit Tuesday, before (above) and after (below). I

pushed back the squash (who were trying to eat the onions), yanked out

our first planting of cucumbers (since we have another bed in full

production now), and harvested the carrots. Other beds had been home to

oats (which didn't die properly and turned into weeds) or garlic

(harvested a few weeks ago). The result is that most of this area is now

fallow until it turns back into a fall garden. So I scattered buckwheat

seeds liberally across the bare ground and can write this area off my

agenda until planting time for kale, lettuce, and brussels sprouts.

Why have we only grown Masai beans

for the last 7 years?

Because they taste delicious with a

little garlic and oil with salt and pepper.

Wednesday's carrot

harvest put Monday's and Tuesday's to shame. These are Bolero carrots,

which get much bigger (although not as tasty) compared to the Sugarsnax I

harvested earlier in the week. The Bolero also seem much less affected

by carrot flies, which is a good thing given this year's infestation.

Without the carrot-fly

depredations, I was able to get a better feel for the difference between

broadforked soil and unbroadforked soil. You may recall that I broadforked half of each carrot bed before planting

in an effort to see what effect this soil-loosening step would have on

the root crop. Overall yields seemed roughly comparable on the two

halves of the bed, but I thought the carrots in the broadforked side

averaged a bit larger and they were definitely easier to pull up. I'll

get Kayla's unbiased conclusions on the last carrot bed tomorrow...if I

can think of somewhere to store another near-bushel of carrots.

Speaking of storage,

upgrading the quantity of carrots we're growing so we can feed some to

the goats means changes in our harvesting habits. In the past, I've

sometimes stored carrots unwashed, but our heavy soil tends to really

stick to the vegetables if I dig them during a rainy spell as I'm doing

this year. Mark had the bright idea of filling up our huge sink with

water, pouring in the carrots, then swishing them around. After draining

out the muddy water, I then sprayed the carrots down well. The

combination of quick-and-dirty cleaning techniques probably removed

about 95% of the soil, which is pretty good for ten minutes of work! Now

if my inventive husband can just put his mind to work figuring out

where to put excess carrots when the weather is too hot to use our refrigerator root cellar....

We sweep the chimney every

year and each time the build up is tiny.

I think it's a testament to how

efficient the Jotul stove burns.

It's easy to get

engrossed in soil improvement and forget how important sun is to

vegetable production. Various lists suggest that some edibles do well in

partial shade, but my experiences have shown that full sun is mandatory

for full production of even supposedly tolerant species like asparagus.

Of course, no one will

tell you to plant tomatoes in partial shade. The photos above show the

huge difference between plants set out in partial shade (photo on the

left, in an area shaded by our wood stove alcove during the morning)

versus what counts for full sun on our farm.

All of the plants pictured (in the foreground at least) are the same

variety, and the ones in partial shade were actually set out five days

before the other. Guess who's going to give us the first tomato of that

variety? The same plant who has fewer fungal problems and will produce

more overall --- the one who enjoys more sun!

We had a water snake visitor

today.

She's probably this far from

the creek to lay some eggs.

Anna chased her away with the

hose and a stern warning not to come back.

One of our readers commented to ask what the parasite-prevention program looks like for our goats.

I haven't posted about it previously because I'm a bit afraid to be

told that you absolutely can't raise goats without dewormers. So far,

though, that's been our plan. Instead of a regular deworming program,

we:

One of our readers commented to ask what the parasite-prevention program looks like for our goats.

I haven't posted about it previously because I'm a bit afraid to be

told that you absolutely can't raise goats without dewormers. So far,

though, that's been our plan. Instead of a regular deworming program,

we:

- Rotate goats weekly (although the goats do return to used pastures much sooner than the 90 days recommended for total worm eradication).

- Primarily feed goats outside the pasture, through morning

tethering and afternoon rambles, so they're very rarely eating where

they've pooped. (We also work hard not to make them so hungry they have

to eat weeds low to the ground where worms are more likely to hang out.)

- Keep kelp (which they scarf down) and minerals (which they largely ignore) available free-choice at all times.

- Keep a close eye on condition to see if worm loads are getting too high.

- Use garlic as our first line of defense if we begin to see problems.

- Cross the dewormer bridge when we come to it. (We've never reached this stage yet, and I'd probably head for copper first.)

What do I mean by keeping

a close eye on condition? Parasites get first dibs on your goat's feed,

so an animal with too many worms will be skinny even though she's

getting plenty to eat. I was intially testing for fat deposits using a weight tape...but

then one of our spoiled darlings knocked the ribbon down from its high

shelf and chewed it apart. So I've moved on to body-condition scoring,

which requires no supplies except your fingers and a goat. As long as

our voracious beasts don't eat my fingers, I'm all set.

This factsheet

walks you through scoring your goat's body condition, so I won't repeat

the same information here. To cut a long story short, you're really

looking for fat in two locations --- under the goat between her front

legs (the sternal fat, which is what a weight tape really measures) and

in the area between the spine and the jutty-out bit (aka the transverse

process) above the hind legs (the lumbar fat).

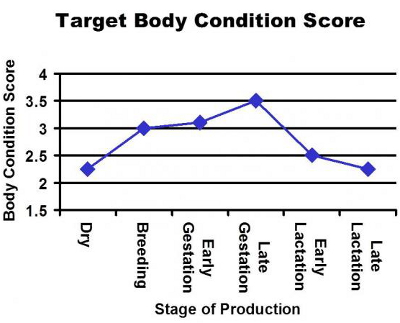

The image to the right is a quick cheat sheet on body-condition goals for milk goats, stolen from this page.

The graph was made for dairy sheep, but is similar to the goals for

milk goats. As you can see, it's best to have a goat bred at a

body-condition score of around 3, then she naturally drops some fat as

she makes milk. However, if you can't keep your milk goat above a

body-condition score of 2, then it's time to dry her off and feed her up

for next time.

The image to the right is a quick cheat sheet on body-condition goals for milk goats, stolen from this page.

The graph was made for dairy sheep, but is similar to the goals for

milk goats. As you can see, it's best to have a goat bred at a

body-condition score of around 3, then she naturally drops some fat as

she makes milk. However, if you can't keep your milk goat above a

body-condition score of 2, then it's time to dry her off and feed her up

for next time.

So where do our goats

stand? Artemesia's body-condition score is a good estimate of her

parasite loads since she's not doing anything difficult (like milking)

and is barely getting any supplemental feed. My estimate is that she's a

solid 3, which is just about perfect. (Much higher and she'd count as a

fat goat.)

Abigail is a bit thinner,

with the fat deposit between the peak of her spine and the transverse

process being very slightly concave rather than in a straight line. Even

though it's not technically part of the body-condition score, I think

it's also relevant data that Abigail's hair doesn't shine in the sun

quite the way Artemesia's does. As a result, I'd estimate that our older

doe's body-condition score is 2.5 --- not too bad for four months into

her lactation cycle. I probably should increase her carrot rations,

though, since I'd let them dwindle recently in favor of feeding mostly

alfalfa pellets in her daily rations.

I should mention that

inside-the-eyelid color is another way of keeping track of a goat's

parasite load, but I haven't crossed that bridge yet. It just seems

easier to feel up our goats externally than to flip their eyelid out to

look inside. However, I feel pretty good about worms at the moment,

given how sleek and healthy our goats appear.

And that's the

far-too-long answer about our parasite-prevention program. Here's a cute

picture of Artemesia to wake you back up in case your eyes glazed

over....

It's that time of year

again --- when I fulfill my end of the coevolutionary bargain with our

perennial vegetables. In other words --- several readers will get free Egyptian onion top bulbs this month in order to turn their garden into a delicious place year-round!

Want

to enter the giveaway? I'm keeping it simple this year. Book sales fund

postage for all of our giveaways, so all you have to do to enter is to

help push our books along. Most relevantly, Aimee's newest novel, Jaguar at the Portal,

just went live today at 99 cents (and is also available for free

borrowing if you have Amazon Prime or Kindle Unlimited). I'd love to

help the title launch with a bang rather than a fizzle. Buy or borrow a

copy, then click on the proper giveaway button below to share the first

word of chapter 10, and you've got a good chance of having a free box of

onions arrive on your doorstep next week.

Want

to enter the giveaway? I'm keeping it simple this year. Book sales fund

postage for all of our giveaways, so all you have to do to enter is to

help push our books along. Most relevantly, Aimee's newest novel, Jaguar at the Portal,

just went live today at 99 cents (and is also available for free

borrowing if you have Amazon Prime or Kindle Unlimited). I'd love to

help the title launch with a bang rather than a fizzle. Buy or borrow a

copy, then click on the proper giveaway button below to share the first

word of chapter 10, and you've got a good chance of having a free box of

onions arrive on your doorstep next week.

Of course, I realize that

many of you aren't interested in fantasy. So I've also included an

option of helping promote my non-fiction books (or any other Wetknee Book).

Reviews make or break our titles, so if you've bought (or downloaded a

free copy of) one of my books in the past but never got around to

leaving a review, here's your nudge to do so. Leave your honest review

on Amazon then put the link in the widget below.

I know I have at least

five boxes of Egyptian onions ready to wing to a new home this month,

but it might turn into more once I sort through my basket. Thanks so

much for helping our books reach a wider audience, and I hope you enjoy

your new perennial vegetables!

It occurred to me the

other day that the things I don't talk about much here on the blog are

the things all of our readers really should be doing. The things that

are so easy and successful that I barely give then a moment of my

attention...until it's time to harvest the results. So, without further

ado, four things I don't often write about:

Pastured chickens. It took us a while to work the kinks out of the system, but our laying flock is mostly a set-it-and-forget-it homesteading project nowadays.

Low-work vegetables.

I know I post (far too much) about struggling with fungal diseases in

our tomatoes and trying to harvest apples despite living in a frost

pocket. But large parts of our garden are as simple as plant, weed and

mulch once, then harvest. I write in more depth about the easiest

vegetables in Weekend Homesteader,

but here's the cliff notes' version (slightly updated over the last

four years): swiss chard, okra, crookneck and butternut squash, green

beans, kale, and lettuce are hard to go wrong with.

Easy cover crops.

Once again, I post mostly about my experiments in this department. But

the trinity of buckwheat in summer and oats and oilseed radishes in

winter build soil while keeping weeds at bay. I adore them and plant

them copiously.

Greywater wetland.

Mark weedate around the greywater wetland last week...which is the

first time we'd touched the area in about a year. The cattails are

thriving and our kitchen-sink water disappears without a trace. In case

you want to learn more, I write in great depth about our greywater

wetland (and other infrastructure projects worth their salt) in Trailersteading.

What do these four facets

of homesteading have in common? They all started out as problems ---

smelly chicken runs, ailing vegetables, poor soil, and a mucky drain out

back. Then we tweaked and tucked and soon created systems that worked

with very little effort on our part. Maybe in ten more years, my

things-I-never-write-about list will include goats and tomatoes and

frost-bitten apples. In the meantime, I hope you enjoy tagging along

with our trial and error. And, I hope you'll consider posting your own

things-too-easy-to-blog-about list below.

Our Swisher

self propelled trimmer mower is a true advancement in weed control.

One problem I had was

carrying the pieces of string in my pocket.

They had a tendency to pop

out while I was mowing until I started clipping them on the middle

support bar with a small

spring clip.

And laptop battery is too low to post. Hopefully we'll be back online tonight, but please don't worry if you don't hear from us!

Power outages have made Anna

an expert at cooking breakfast with propane.

Total time off the grid was a

little over 20 hours.

Two thumbs up for the battery

powered fan that kept me cool all night.

I might've gone a little

bit overboard on our butternut squash planting this year. The photo

above shows about half of our planting, growth fueled by chicken deep bedding.

Now that the vines have thoroughly filled in, the patch is pretty impressive. There aren't even any aisles left to mow!

In fact, the squash are

already starting to run out of bounds. This particular stem has passed

over a bed of buckwheat and is moving into our main avenue. Maybe I

shouldn't have used the electric fence on the chickens and should have saved it for our naughty butternuts?

Nearly full-size fruits

are already abundant beneath the leaves. I expanded our butternut

planting this year for the sake of our goats, who particularly enjoy the

seeds (a natural dewormer

and all-around tasty treat). But if everything keeps going at this

rate, both humans and goats might have a hard time eating our way

through the bushels of cucurbits when winter rolls around!

A good problem to have....

We liked our Little

Giant feed trays so much we got one for the milking stanchion.

Now we can lift it off to

empty out the crumbs that Abigail leaves behind.

Our tomatoes are finally

ripening fast enough that I think we'll be able to make our first pot of

soup this week. That's good news since vegetable soup is a mainstay of our winter diet --- time to get cracking!

The bad news is that I'm pruning the plants higher and higher as the blights

spread. Septoria was soon joined by small outbreaks of early blight,

and I'm very afraid that the dreaded late blight has entered the fray

now. I'm ready to deem these new blight-resistant tomato varieties

a dismal failure --- flavor isn't nearly as good as the heirlooms I'd

been growing, and they don't appear to showcase any extra blight

resistance at all.

Next year, we may try yet another anti-blight experiment --- creating an

anti-rain canopy out of clear plastic over the tomato patch. Like a

greenhouse with no walls....

On the positive side

again, hornworms are appearing...and disappearing nearly as quickly as

they show up. This little guy doesn't even appear to have lived long

enough to get parasitized by wasps. Perhaps this is an example of the plant creating anti-nibbler pesticides within its leaves?

Meanwhile, a song sparrow

family has moved into one of my tomato plants. I'd thought that the

mother bird would give up on the nest once I pruned away blighted leaves

that used to shield the contents from rain and view. But Tuesday I

found a tiny spotted egg inside, nestled atop Abigail's hair. Looks like

our resident sparrow couple will have another successful nesting this

year! Round one occurred in the hardy kiwis, and I was treated to the

inspiring view of one of the babies waking up from its nap and gaping

for food before I let the vines curl back over nest #1. Here's hoping

Mama Sparrow does as well with round two.

We crushed one of our cattle

panels last week with a falling tree.

The new plan is to lay them

all flat on the ground before we cut another tree.

I'd been putting off adding a third box to our daughter hive, hoping that the mother hive would be done moving into the Langstroth boxes so I could begin converting

the daughter hive with the same hardware. But when I dropped by the

daughter hive Thursday morning to refill their feeder, the photo above

shows what I saw. Unless the weather is very hot, bearding is a sign

that the bees in your hive need more room. Time to get my act together

and add another box!

After

waiting until the sun was blazing and the foragers were out in the

field, Mark and I stopped by the mother hive first. The one Warre box in

this hive was very heavy, full of capped honey, and at first I thought

I'd be able to call the conversion a success.

After

waiting until the sun was blazing and the foragers were out in the

field, Mark and I stopped by the mother hive first. The one Warre box in

this hive was very heavy, full of capped honey, and at first I thought

I'd be able to call the conversion a success.

But when I delved into

the Langstroth box underneath, I found only honey and pollen, no brood.

And when I peered more carefully up under that single Warre box, I saw

some capped brood, signaling that the queen is still working up in the

attic. So I put the hive back together as-is and headed over to the

Warre hive with plan B in mind.

Although we could have made another Langstroth-to-Warre converter, I opted to instead go the simple route and just nadir

another Warre box under the daughter hive. The bees will have space to

keep expanding, and we'll wait until next year to convert them over to a

Langstroth hive.

On a different note, I

was heartened by how hard both colonies of bees are working this year.

The daughter hive is on the dole (sugar water), which seems to have

helped them bulk up well (although they still have a lot fewer foragers

than the mother hive). And the mother hive is doing well also, although

they appear to have eaten some of their honey since I last checked. If

nothing else, I hope both hives will be ready to go into winter without

any (or much) additional fall feeding.

The bird nest in the tomato patch is right along the main walkway to the composting toilet,

so I see Mama Bird several times a day. As long as I look in the other

direction when I walk past, she stays put, lack of eye contacting

tricking the song sparrow into thinking she hasn't been noticed.

But when I pulled out the

camera, even using the zoom from a distance was enough to spook Mama

Bird. I figured I might as well look in the nest since she'd flown away

for the moment, and I was pleasantly surprised to find four eggs

clustered atop goat hair.

Song sparrows are one of

my favorite birds, mostly because of their ubiquity in human habitats

and tolerance toward people. But this is the first time I've had such an

up-close-and-personal experience with their nesting behavior. I'm

looking forward to daily views of baby birds, perhaps in a week or two.

I couldn't find hardware

cloth with 1/8 inch holes at any store around here.

It's the perfect

screen material for beehive bottom boards.

Anna found us a 10 foot roll

for 25 dollars on Amazon.

I've learned a lot about

firewood this year. For example, this gem courtesy of Kayla's father

(slightly tweaked): Tulip-trees are always longer than they are tall.

Or how about this one: If you want to create a sugar-bush/goat-pasture hillside, cut down your trees before putting up your fences.

Here's a word to the wise: Let the goats eat up the poison ivy before sticking your head into the thicket to cut up logs.

And I'll end with: An hour a day fills up the woodshed (with a little help from your friends).

Now, if we can just

remember to starting cutting firewood in March instead of June next

year, we might finally have a fully dry stash of combustibles when

winter rolls around. In the meantime, I'll just enjoy the fact that

we're nearly on quota for this coming winter, and that the hillside

above the starplate coop now has a canopy open enough to let

goat-friendly herbs grow on the forest floor. Here's hoping the sugar

maples and black birches we carefully left behind will also benefit from

the extra light and will produce plenty of sugar next spring.

Our new step stool developed

a small crack on the top step.

Attaching a furring strip

with small screws through the plastic seems to have made it stable

again.

Homesteading can feel so

surreal in the summer, when the temperature is in the 90s but you know

that only about three months remain until the first frost. Then you do

the math and realize that 58% of the year isn't safe for tender summer

herbs and vegetables. But even with those warnings of the long, cold

months ahead, how can you resist living in the restful sea of summer

green?

If you want to feed

yourself homegrown vegetables all year, though, it's time to eschew the

grasshopper lifestyle and turn into the ant. We've already got a bit

over a gallon of summer produce stored away in the freezer, and much

more will be hitting the ice box shortly. Meanwhile, the garlic is

nearly done curing and the onions will soon hit those drying racks.

We're planting fall crucifers and lettuce and carrots for fresh winter

eating, and I'm dreaming of upgrading from quick hoops to a movable

greenhouse for more serious frost-protection some year soon.

But I'm also taking advantage of the hot weather to take the goats out in the woods for extended bouts of grimming (they graze, I swim). The living may not be easy on a farm in the summertime, but it sure is satisfying!

Mounting a pole fan to the ceiling on a lazy susan bearing makes it easy to change direction and keep the fan out of the way.

"Is

there a five, ten year or longer plan for wood? That is will there be a

rotating supply for the future growing in time? Good idea on let [the

goats] eat poison ivy. Any trouble touching them after they have brushed

up against the leaves?" --- Jim

"Is

there a five, ten year or longer plan for wood? That is will there be a

rotating supply for the future growing in time? Good idea on let [the

goats] eat poison ivy. Any trouble touching them after they have brushed

up against the leaves?" --- Jim

Jim has a very good

question about developing a sustainable firewood supply. To be entirely

honest, we haven't had to cross this bridge yet because we own 56 acres

of woods and seem to be constantly needing to take out trees to give me

more room for pasture or orchards or to keep our driveway clear. I

suspect we'll continue on this getting-established track for several

years to come.

In the long run, we will need to develop a plan for firewood harvest, though. One option is to coppice the trees in the powerline cut that aren't supposed to grow too high anyway. The plus side of this is that small wood is very easy to harvest with our electric chainsaw,

it dries quickly, and the limbs require little or no splitting in the

winter. The downside is that it takes about three times as long to sock

away the same volume of firewood when working with small branches versus

larger trunks.

Another

option is to develop a woodlot plan for the areas close enough to our

core homestead to make transport of the firewood simple. Selecting a

maybe 5- to 10-acre zone in which our goals are promoting trees for

sugar tapping (for the humans), nectar production (for the bees), and

log production for mushrooms would give us an incentive to take out

competing trees in that area. I've already started this plan in my head,

but should probably commit it to paper soon while I still know where

all those useful trees stand.

Another

option is to develop a woodlot plan for the areas close enough to our

core homestead to make transport of the firewood simple. Selecting a

maybe 5- to 10-acre zone in which our goals are promoting trees for

sugar tapping (for the humans), nectar production (for the bees), and

log production for mushrooms would give us an incentive to take out

competing trees in that area. I've already started this plan in my head,

but should probably commit it to paper soon while I still know where

all those useful trees stand.

To answer your second

question --- I'm not actually allergic to poison ivy, and was (I'm

ashamed to say) ripping poison ivy away from our newly cut trees with my

bare hands Friday evening. Unsurprisingly, I didn't notice any issues

when petting on our darling doeling after her cleanup job.

That said, I definitely wouldn't have let my mom touch a goat who has

been on poison-ivy duty since she seems able to contract poison ivy just

by looking at a plant funny. So your mileage will definitely vary.

We harvested about 10 pounds

of carrots today.

Lucy likes to watch anything

we do that happens close to the ground.

You may recall that I planted some experimental cover crops this year hoping they'd be cut-and-come-again mulch producers.

The ones I was most excited about --- pearl millet and

sorghum-sudangrass hybrids --- aren't really living up to their

potential. These warm-season grasses remind me of corn in that they grow

big stalks that require interim weeding and mulching, but the cover

crop versions actually appear to produce less biomass than corn does. As

a result, I feel like I would have been better off planting these beds

with sweet corn or field corn then using the corn stalks if I wanted to

harvest biomass from warm-season grasses. All told, I'm not very

impressed by the warm-season grasses, even though sorghum-sudangrass

hybrids are reputed to produce more biomass per acre than any other

cover crop.

On the other hand, soybeans as a cover crop

continue to intrigue me. The soybeans we planted on June 10 are just

starting to bloom, so I chose one patch to scythe a few inches above the

ground in hopes the plants will grow back and let me cut again in a few

more weeks. While I was at it, I also scythed the buckwheat growing

next door (planted two weeks later) and then I replanted the whole patch

with new buckwheat seeds.

Before I go into the

results, I should tell you that I'd been out cutting pasture weeds

before embarking on this experiment, so my scythe was a little dull. As a

result, the tool yanked up (rather than cut down) perhaps 10% of the

soybeans. Gathering up the cut tops was easy, but I only got an armload

out of this whole patch, which would probably be about enough to mulch

15 square feet in the garden. Lazily, I instead simply tossed the cut

tops onto our compost pile.

A perhaps better use of a

soybean cover crop (although more expensive since the initial seed

investment doesn't go as far) is to pull up entire soybean plants then

use the legumes to feed the next crop. I yanked up the soybean plants in

the bed pictured above less than a week ago, piling the cover crops in

between rows of new sweet corn. The soybeans are so high in nitrogen

that they're already disintegrating into the soil six days later,

meaning they'll feed the corn plants by the time the roots reach the

center of the bed. Whether or not the soybeans produce enough nitrogen

to feed an entire bed of corn with no additional amendment remains to be

seen. I'll keep an eye on leaf color and report back in a few more

weeks.

We've been growing Clemson Spineless Okra since 2007 and have saved the seeds every year.

Apple-maintenance day is

often my favorite time of the month. And not just because I find

beauties like this hidden amid the weeds.

Spending a few hours manipulating and experimenting with perennials is simply rewarding. Here, I'm stooling one of our apple rootstocks in hopes I'll be able to graft onto homegrown roots next spring. (Because I'm in sore need of more apple trees...right?)

Meanwhile, this year's experiment of planting buckwheat within the rows between young apple trees is already deemed a resounding success. As you can see, it looks like

I let this row go to weeds. But half an hour spent ripping out

buckwheat and stacking the plants at the base of each tree (then

replanting the cover crop in the gaps) provided nearly instant mulch. I

can feel the soil turning darker nearly before my eyes.

Meanwhile, this year's experiment of planting buckwheat within the rows between young apple trees is already deemed a resounding success. As you can see, it looks like

I let this row go to weeds. But half an hour spent ripping out

buckwheat and stacking the plants at the base of each tree (then

replanting the cover crop in the gaps) provided nearly instant mulch. I

can feel the soil turning darker nearly before my eyes.

I even had a little time left after taking care of the apples (and trimming the goat hooves) to go check on my willow cuttings.

The ones I'd stuck right up close to the trailer and then hidden behind

mushroom logs had spotty success, but all of the ones out in the open

survived...even though the soil there is terrible and I forgot to keep

the weeds at bay. Okay, so Mark did

accidentally mow one of the eight plants down since my mulch was pretty

much nonexistent, but that doesn't mean we didn't have 100% rooting

success first. I applied a quick newspaper kill mulch then snipped off

the lower limbs to train each new willow tree to a central leader,

preparing for my plan of building with living trees.

And that's the highlights

of my fun morning with the trees (and turtles). I can hardly wait until

tree day next month! (Yes, you only get one Arbor Day per year, but I

treat myself to twelve Tree Days. I'm spoiled that way.)

Today was the first dry day in July we've been able to use the ATV.

The internet was a bit unclear on whether the whey from mozzarella can be used to make ricotta. But I decided to give it a try anyway.

I'm no sure if this step

is necessary since mozzarella whey is already acidified from the lemon

juice, but I let the whey sit at room temperature overnight anyway. Then

I brought the whey to a simmer just as I would when making any other

kind of ricotta, strained out the liquids, and then let the solids drip

in a bag of cheesecloth for a few hours.

The result is ricotta much tastier than that which I got from chevre

whey! In fact, mozarella-offshoot ricotta is so tasty that I froze the

mozzarella for later and set aside the ricotta as this week's cheese.

It's delicious when added to sauteed summer squash right after you turn

off the heat so the ricotta melts into the vegetables. And this ricotta

is also a great addition to tomato-and-cucumber salad drizzled with a

dressing of olive oil, balsamic vinegar, honey, salt, and pepper.

Ricotta has now officially joined the ranks of my favorite cheeses!

Our perkiest strawberry plants this year are the ones that got rabbit manure.

Onions nearly ready to harvest. Persimmon grafts (the ones that took anyway) growing like gangbusters, and a hint of red on the buckeyes. A beautiful Friday on the farm!

Mom was very taken by our scarlet runner beans

when she came over. She felt like I hadn't given an accurate picture of

their impressive height and spread on the blog...but I'm afraid I've

still been unable to capture the full awesomeness of this bean. The

photo above shows beans who have only had about two and a half weeks to

grow up their trellis. They've been at roof height for half that time!

The plants in the first

picture haven't bushed out enough to provide much shade yet, but the

ones on last year's trellis on the south side of the trailer are already

doing a pretty good job breaking the summer sun. A hummingbird comes to

these plants each morning --- a perfect view to eat my breakfast to.

And, look, beans already being set to feed us this winter!

A lot of factors go into how long you decide to milk a goat. First, there's body condition, which I've discussed previously. If your goat has lost too much weight, you need to stop milking.

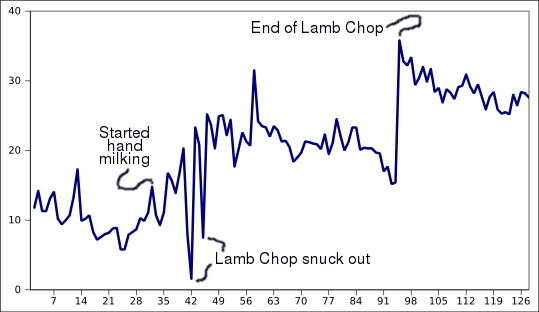

The other issue is

whether it's worthwhile for the human to keep milking as production

slowly declines. The chart above shows Abigail's lactation curve to date

(starting three weeks after Lamb Chop was born, when we started locking

him away for the night). There

was a lot of human learning involved in our first effort, so this curve

doesn't look like they usually do --- with low production slowly rising

to a peak at around 4 to 6 weeks post kidding, then declining back

down. However, you can see that production is already dwindling markedly

so we're now averaging about three and a third cups per day. I suspect

that when I'm only bringing home one or two cups per day, I'll decide

the milk is no longer worth the squeeze.

One thing to keep in mind is that Abigail was a cheap starter goat. Artemesia's genetics are more high-brow, so there's a good chance our doeling will produce more milk for longer than Abigail has.

Why bother with a goat who doesn't give very much milk? I figured it was

worth learning on a cheaper goat, and I stand by that decision as a

good one. It would have been a shame to decide we didn't like goats

after sinking much more money into the project, and Abigail has also

proven to be an easy keeper, which might be better than an amazing

milker in the long run. So I'm happy with what I've got...but am looking

forward to much more milk next year.

And, in order to get that milk, we're going to have to breed both goats. You can read my thoughts on our options here,

with the caveat that I'm leaning more toward buying a cheapish buck

whom we can use and then eat in the fall. Now that I'm pretty sure we'll

need to breed both goats (rather than milking Abigail through), the

hassle of bringing two separate goats to be bred when they come into

heat at two different times seems larger than the hassle of dealing with

a buck for about a month.

At the moment, though, we're just enjoying our happy little herd and our delectable milk products. I'm still thoroughly in love with our goats!

We got in some more straw

bale hauling today before getting rained out.

Seems like our older ATV

needs about a quart of oil every year.

I usually try not to go

down that slippery slope of filling up my pockets. But Monday, I

realized I'd accumulated an odd assortment of odds and ends. The

pocketknife is present to cut straw-bale strings since Monday is deep-bedding-top-up

day. The seeds are to fill gaps in the garden where I noticed beans and

cucumbers didn't come up as perfectly as I'd like. And the potato onions were found while planting the beans, overlooked during a previous harvest.

My Monday mornings are

generally about as diverse as the contents of my pockets. I have to fill

about an hour and a half before the dew dries off the tomatoes, but I

don't want to get so engrossed in a big project that I'll forget about

my primary purpose for the day. So I scythe pastures animals were

recently rotated out of, feed the bees, tether the goats, and generally

mark little things off my list. And then it's time to prune those tomatoes and make some pesto chicken salad for lunch...and empty out my pockets!

Our Spring

chicks have reached the point where the roosters need to be retired.

We put 3 in the freezer today

with another three planned for later this week.

What's wrong with this picture?

(Guess before you peek!)

If you said that

Artemesia was eating our sweet corn, you got tricked by the zoom-related

flattening of the photograph. Our little doeling was actually about

five feet beyond the corn in question when I clicked the shutter button

on our camera.

On the other hand, if you noticed the large distance between the corn plants, you're on the right track. My germination test

this past winter suggested that last year's corn seeds were fine. But

in the real-world setting of our garden, those same seeds came up very

spottily. That's a problem since corn is wind pollinated and relies on a

relatively large stand to ensure the seeds develop well and the ears

bulk up. In fact, I was expecting to see lots of cobs like the one

pictured above when the time finally came to harvest our crop.

To my surprise, most of

the seeds seem to have set even with less than a dozen plants to spread

their pollen. While I'm glad the corn plants came through for us this

time around, I've resolved to stick to buying corn seed every year

rather than trying to eke out those packets for a second season. It

appears that corn, like onions, is simply better planted during year

one. Live and learn! At least we can still eat my mistakes.

I found a June Bug in a

bucket and thought the chickens might want it.

They seemed to enjoy watching

it bounce around, but could'nt quite reach the bottom of the 2 gallon

bucket.

The bug was snatched up by

what I assume is the quickest hen when I dumped it.

I was a little concerned that Mama Song Sparrow

might have decided she'd settled in too much of a high-traffic area and

abandoned her nest, because she seemed to be off more than she was on.

But I guess in the heat of July, you don't have to hug your nest to

hatch eggs. Because when I peered into the tomato patch Tuesday, I saw

two baby sparrows already out of their shells and looking for lunch.

Now to leave Mama Sparrow alone for a few more days and hope she hatches two more. It's been a couple of years since we've incubated our own chickens,

so it's fun to vicariously enjoy a successful hatch, albeit of a much

smaller species. And it's always a joy to watch wildlife move into our

garden...as long as they're not eating our crops.

With three more cockerels in the freezer, I'm ready to pass judgment on this year's round of experimental chicken breeds. I didn't raise the five varieties separately, so I can't tell you who cost the least to feed, but I do have data on foraging ability, rooster weight at roughly fifteen weeks, and survivability. I'll start with the last.

We had quite a few predator losses this year, mostly due to human error (we forgot to shut in the chicks

a few nights) but also partly because our guard dog is getting on in

years and sleeps more soundly than she used to. It could be entirely

random which chicks got picked off, but I wanted to mention that the

australorps came through unscathed, the orpingtons only lost one bird,

and the three other varieties lost two birds apiece. This is interesting

because I'd read that dominiques are very good free-range birds because

they're less likely to get picked off --- that wasn't the case in our

very small sample.

Moving on to meat

qualities of the birds, I don't have any data on dominiques or New

Hampshire reds. It turns out we did end up with one dominique cockerel,

but his comb was so small when we went to snatch birds off the roost by

flashlight that I thought he was a girl! And all of our surviving New

Hampshire reds turned out to be girls as well. So you'll have to wait

for an update on meat qualities of these two breeds at a later date.

My all-around favorite

(without tasting any of the meat) is definitely the Rhode Island red

(the dark brown bird in the photo above). Australorps grew a little

bigger (averaging 2 pounds 13.9 ounces dressed for the australorps

versus 2 pounds 11.9 ounces dressed for the Rhode Island red), but the

Rhode Island red had the brightest fat. This is a key indicator if

you're looking for high-quality pastured meat since yellow fat comes

from birds that forage the most, meaning you're getting more omega 3s

and the birds are probably eating less feed.

In contrast, our orpington cockerels were big losers, having quite pale fat that almost looked like the fat on a cornish cross.

The orpingtons were also the lightest birds at fifteen weeks, clocking

in at 2 pounds 6.2 ounces. Although they'll likely catch up to the other

breeds later, this slow growth probably also means they eat more feed

for every pound of meat that ends up on the table (although I can't be

positive of that fact). As a final nail in the breed's coffin, the

orpingtons are the only birds in this flock who have been causing

trouble, refusing to abide by my pasture rotation and returning time

after time to the first pasture we started them out in. So while Kayla

assures me that orpingtons are good pet chickens, I'm afraid I have to

take them off my list of prime thrifty chicken breeds.

One nice thing about Anna taking the goats out to graze is the bonus mushrooms they find and bring home.

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.