archives for 05/2015

There's no doubt that our goats enjoy comfrey.

I have patches here and there throughout the farm, and Abigail

especially is always looking to grab a mouthful as she passes by. But of

my three types --- Common Comfrey, Bocking 4, and Bocking 14 --- which should I most focus on propagating for goats?

On a rainy afternoon when

tethering didn't seem to be an option, I decided to run a comfrey taste

test. First, I brought the goats a bucketful of Common Comfrey, which

they seemed to adore. However, when I came back a couple of hours later,

most of the comfrey was still in the bucket. Maybe another variety

would be better received?

This time, I grabbed a

handful of each of the three varieties and presented two handfuls at a

time to the goats to try to get a taste preference. Their answer? All

comfrey tastes delicious when handfed! They slurped up every leaf of all

three types (while continuing to ignore the container of older comfrey

leaves at their feet).

So I guess the solution

isn't to focus on a particular variety, but to instead figure out a

better presentation option for feeding cut comfrey to our goats. Any

ideas? (No, I'd rather not stand in the rain and feed our goats leaf

after leaf, even if that method is Abigail-approved....)

We decided to give up on the Warre hive box method of raising bees.

The plan is to lure the hive

now living in one of our Warre boxes to migrate into a Langstroth

box with a hole cut in the top.

I attached a piece of wood on each side to prevent any accidental bumps.

May Day is my traditional

planting of the first big round of summer crops. Our frost-free date

isn't until May 15, but it takes seeds a few days to come up and late

frosts are usually quite mild. As a result, a bit of row cover fabric is

generally sufficient protection for the

tender-but-not-excessively-tender crops like green beans, sweet corn,

and summer squash. (We save true tenderfoots like sweet potatoes,

peppers, tomatoes, and okra for after the frost-free date, when I plant a

second round of the early birds too.)

Actually, the first three

weeks of April were so warm this year that I started thinking I might

get away with presprouting some of this first set of summer seeds. So

the green beans and (perhaps not the brightest idea) the experimental

arava melons went into the ground as seedlings just barely starting to

poke their cotyledons above the soil surface. Only time will tell

whether I regret this move, or whether pre-sprouting gives me crops a

week or two earlier than their seed-started bedmates.

Meanwhile, I'm now regretting having jumped the gun by starting my tomatoes inside during the last week of February.

The plants thrived for quite a while, but they really needed more space

and more sun by early April. I suspect that's why a damping-off fungus

leapt from a tray of zinnia seedlings into the tomatoes and began to

wreak havoc once warm weather hit. I've never seen such mature plants

succumb to damping off, but something caused about half of my tomatoes to decline and several to outright kick the bucket.

I thought I didn't have any more seeds of the disease-resistant varieties

I'm trying out this year, but last weekend I realized that I did, in

fact, have quite a few more seeds in my storage box. So I started

another flat of seedlings who will be barely big enough to go into the

ground at our frost-free date. In the meantime, I also set out three of

my best-looking tomato plants in the cold frame in front of the trailer.

I don't like to plant tomatoes outside before frost is definitely in

the rear-view mirror, but by sinking the plants pretty far into the

soil, I should still be able to close the cold-frame lid for the next

two weeks if frost comes to call one more time.

(Okay, yes, I snuck two

borage plants and a row of zinnias into the front of the cold frame as

well. Here's hoping I don't regret planting so close to the tomatoes,

but I can always weed the flowers out!)

The square hole for the Warre Langstroth adapter is 12 inches on each side.

It took less than two weeks after flipping my experimental shiitake logs

over before the second side of the new round was well colonized. At

this point, the two logs and the cardboard sandwiched in between were

all fused together with mycelium, and I had to tug gently to break them

apart.

I'm assuming that means

the new round can now take care of itself, with the mycelium moving in

from each direction to colonize all of the wood in the middle. So it's

time to see if I can force fruit my mini-log using common kitchen items.

First, an overnight soak in a tupperware container full of water, then a

few days in the fridge to simulate winter. If all goes as planned, we

could see mushrooms beginning to bud on the log surface as early as next

week, about ten weeks after inoculation.

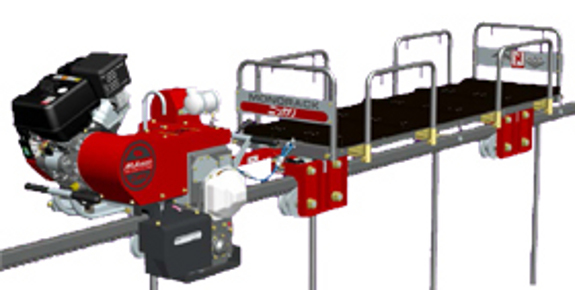

We made contact with a super

nice guy at the monorail factory in Japan who has agreed to put a

Briggs and Stratton engine on one so they can ship it to us here.

The new engine configuration

has to go through 300 hours of testing first, which means we'll have to

wait a few months.

We'll be their first sale in

the United States.

"Do you think you'll run

out of weeds for the goats to eat?" Joey asked when he was over this

weekend. The answer will depend on whether or not tethering our little

herd in the woods works out.

Dry weather has finally

slowed the growth of grass within our core homestead, so I've started

taking the goats beyond our fences to graze. The trouble is that the

goats don't feel quite so safe outside the boundaries...and I'm not sure

whether it's really safe for them to be that far away, tied down so our

local pack of wild dogs could make short work of them. Of course, I'm

always home, Lucy is always on patrol, Abigail has big horns, and the

goats are always well within ear shot, so I think Abigail and I are

probably both overreacting.

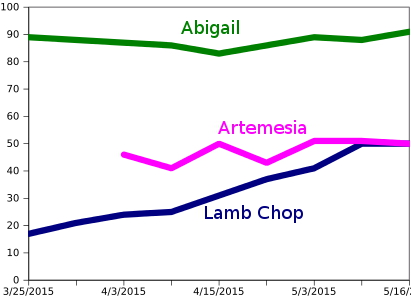

My tethering method

currently involves putting Artemesia on a long line, leaving Lamb Chop

untethered (if we're safely away from the garden), and then putting

Abigail on the shortest leash with the deepest anchor. It sounds

counterintuitive, but Abigail is such a browser that if she has a long

leash, she spends most of her time wandering around picking out which

morsel looks the tastiest. On the other hand, if you put her on a short

line, then she hunkers down and eats for nearly two hours...at which

point I go out and move her to the other side of Artemesia's spot. If

the weather permits, Abigail seems to fill her belly within about four

or five hours, even in the slimmer pickings of the woods, which works

well with my daily routine.

Lamb Chop is generally done eating within the first half an hour...especially if he's broken out of his stall and stolen the morning milk again.

(Bad Lamb Chop! And here Abigail had upgraded to three cups a day too!)

Luckily, Artemesia doesn't need much more grazing time than that and is

quite willing to butt heads or nap with her charge while Abigail

continues stuffing her rumen.

I keep hoping to see

signs of heat from our doeling since both Nubians

and Nigerians (her two lineages) can sometimes go into heat out of

season, but Artemesia always likes spending time with the buckling, is

always a loud mouth, and

always wags her tail a lot. She even lets Lamb Chop mount her, but it

seems to be in more of a "whatever, he's a kid, let him play" sort of

way. I'm hopeful that when they're both really serious about mating I'll

be able to tell the difference, but I'm not so sure. From an

animal-management perspective, it sure would be nice if Artemesia got

pregnant now for a fall kidding and Lamb Chop went in the freezer, but

there's not really much I can do about goat sex....

We got the sprinkler system

going today for the first time this year.

Adding a coat of White

Lithium Grease before it gets wet seems to make some of the

sprinklers go all Summer without a re-greasing.

After so many years of

raising chicks annually, we've got chick care down to a science....until

I forget to follow the rules. Problem one this year was when I started

out with the automatic feeder you can see at the top of this post instead of the tray feeder

I usually use with very young chicks. I had forgotten that minuscule

feet can hop right in the larger automatic feeder and scratch grain all

over the ground. After wasting about half a gallon of feed, I remembered

and went back to the old way. I'll upgrade to the automatic feeder once

the chicks are eating the entire contents of the tray feeder in a day

and need a bigger reservoir.

The bigger mistake I made

was completely forgetting to shut the brooder door on Friday night.

Keep in mind that the brooder is located only a few feet from our back

door, in an area fenced off from the wilds and patrolled by Lucy at

regular intervals. Despite this supposed safety, I woke up to one dead

chick, a spooked flock, and perhaps four other birds missing. (It's hard

to count when they're all cowering in the weeds.) It always hurts when

you lose plants or animals due to human error, but hopefully the sad

reminder (plus Mark's backup memory) will suffice to keep the brooder

door closed every night in the future.

On the plus side, the surviving chicks are growing like crazy and have

reached that perfect age where they like to ramble through the nearby

raspberry patch. It's fun watching each breed grow into its unique

feathers!

We uncovered our fig

trees today and were

relieved to see signs of life.

I'd say if they can survive

the extreme cold of this past Winter then they can make it through

anything.

My weather guru

doesn't want to commit to no more frosts this early in May. But the

10-day forecast shows lows only descending in the mid-50s to low-60s

between now and our frost-free date, so I decided to go ahead and set

out our tomatoes. Worst-cast scenario, we can always cover the plants with buckets

during the inevitable Blackberry Winter. Best-case scenario, there

won't be any more freezes and our little plants can finally start

perking up with their feet in the earth. I know it's just my

imagination, but the plants look happier already.

Meanwhile, I went ahead and set out eight sweet potato slips

as well. I've got lots more slips coming off my tubers inside or

rooting in a cup of water, and those will go in the ground throughout

the month of May. But since these guys were rooted and ready (and since

the highs are suddenly very summery), I decided to set them out early.

On the other hand, I really will wait to transplant the peppers and basil until after our frost-free date. Probably. Maybe....

We noticed our first cabbage worm of the year today.

Feels like a good time to

plug Anna's new book "The

Naturally Bug-Free Garden".

Its got 4.5 out of 5 stars

and makes a great Mother's Day gift.

It's that time of year

again --- fruit-dreaming season! This year, the crop I'm watching most

closely is my seckel pear, which does appear to have set around half a

dozen fruits.

Of course, lots can

happen between now and fruit-ripening season, but

spring freeze damage and the plants' ability to hold onto the developing

ovaries are usually the deciding factors in whether or not we'll get to

enjoy a given fruit each year. For example, our apples are right at the

stage where failed flowers fall off at the lightest brush of a finger.

The photos above show the same twig before and after my test touch ---

there might be one apple staying in that cluster...if I'm lucky.

Up in the blueberry patch, there's yet more bad winter-kill news. None of the rabbiteye blueberries

outright perished in last winter's cold, but all were damaged. On the

other hand, our two northern highbush blueberries are a year or two

slower to fruit, but they shrugged off the extreme cold and are now

coated with flowers. I guess I'll be digging up the rabbiteyes and

giving them to my mom (who lives in town, at least one zone warmer),

then focusing on northern highbush blueberries in the future.

Up in the blueberry patch, there's yet more bad winter-kill news. None of the rabbiteye blueberries

outright perished in last winter's cold, but all were damaged. On the

other hand, our two northern highbush blueberries are a year or two

slower to fruit, but they shrugged off the extreme cold and are now

coated with flowers. I guess I'll be digging up the rabbiteyes and

giving them to my mom (who lives in town, at least one zone warmer),

then focusing on northern highbush blueberries in the future.

Next door, gooseberries

and currants continue to prove themselves as ultra-dependable berries.

Last summer, something defoliated our gooseberries long before their

time...but despite the damage, the bushes are loaded with fruits once

again. Winter cold, spring snaps, and apparently whatever ate their

leaves aren't nearly enough to faze this thorny but productive bush.

Speaking of

ultra-dependable, our strawberry fruits are plumping up as always.

Whenever I wonder why everyone doesn't focus on strawberries as one of

their primary fruits, I remind myself of the hard work that goes into

weeding out runners to ensure my plants stay big and the fruits taste

delicious. But if you're willing to weed, it's hard to go wrong with

this fast, productive fruit.

In other strawberry news, now's a good time to report on my oat-mulch experiment.

As I suspected, oats seeded around strawberry plants in the fall

competed with the main crop, resulting in much smaller plants with many

fewer flowers in the spring. The plant on the left was in the control

half of the bed, mulched with straw, and the little plant on the right

further back was surrounded by a living oat mulch. I had

to try the technique after reading about it...but I'm glad I only

experimented on a very small scale. I estimate production under the

living-mulch system will be a third to a fourth of that under my usual

system.

In other strawberry news, now's a good time to report on my oat-mulch experiment.

As I suspected, oats seeded around strawberry plants in the fall

competed with the main crop, resulting in much smaller plants with many

fewer flowers in the spring. The plant on the left was in the control

half of the bed, mulched with straw, and the little plant on the right

further back was surrounded by a living oat mulch. I had

to try the technique after reading about it...but I'm glad I only

experimented on a very small scale. I estimate production under the

living-mulch system will be a third to a fourth of that under my usual

system.

Returning to the point of

this post.... In the end, it feels a bit strange to be focusing so hard

on fewer species --- apples, pears, raspberries, strawberries, northern

highbush blueberries,  and

gooseberries --- with so many experimental species being ripped out

this spring. (Hardy kiwis, figs, and grapes are still borderline enough

to stay...for now.) On the other hand, I learned from each "failed"

species, and I'm now realizing that keeping only the dependable

producers will mean nearly as much fruit with only half the work.

and

gooseberries --- with so many experimental species being ripped out

this spring. (Hardy kiwis, figs, and grapes are still borderline enough

to stay...for now.) On the other hand, I learned from each "failed"

species, and I'm now realizing that keeping only the dependable

producers will mean nearly as much fruit with only half the work.

Mark and I envision a farm where we grow all of our food in half or a

quarter of the current time in just a few years, and I can definitely

see our garden working toward that point as we expand the top producers

and cull the duds. Of course, I'll probably spend any time saved on

further experiments. But what can you do? I like to try new things....

We installed our new Warre

Langstroth adapter box

underneath the active Warre hive today.

The transfer was very smooth

and sting free.

The floodplain isn't

precisely dry, but after quite a bit of hot weather, the groundwater has

sunk about six or eight inches below the surface. Which means that Mark

is now able to get the ATV to the edge of our new footbridge,

about 370 feet from the trailer. And roughly two-thirds of the distance

from motorized transport to garden is easily traversable by

wheelbarrow. Yep, the combination of factors finally makes it worthwhile

to haul in ten bales of straw!

This isn't the time of year to buy straw.

Since no one has cut their overwintering grains yet, any straw

available hails from last year and is expensive --- $8 a bale, and only

available a 45-minute drive away. But I couldn't stock up on our usual

supply of straw last year because the offerings turned out to be full of

grain seeds, so the extra time and money is worth it now to keep the

spring garden in good shape. It's even worthwhile to haul the straw one

bale at a time up the hill pictured above.

Back in the garden, I

made short work of my delicious new organic matter. I've been hoarding

newspapers since 2012 (according to the dates on the pages), and I put

most of my stash to good use acting as a weed barrier beneath the straw.

That meant I didn't have to hand-weed each bed before mulching, and I

could also use the straw more lightly than I would have needed to

otherwise. Between Mark's hard work with the weedeater and the

newspaper-straw combination, our garden is finally starting to look

presentable! (Mom and Kayla, any chance you'll start saving me newspaper

once again?)

Hand

milking our goat means we

have to filter out any stray hairs.

This stainless

steel funnel with filter

works about the same as a clean cloth but is a whole lot easier to

clean.

Grafting plums using dormant scionwood and rootstock

is not usually recommended, so I was much heartened when two of my five

grafts took immediately and sent vigorous shoots up from the scionwood.

Of the other three rootstock/scionwood combinations, I was willing to

give one plant a little more time to make up its mind since the

scionwood looked good  and

there were no sprouts yet from the rootstock either. But I assumed that

the grafts on the last two plants had failed. After all, the plants in

question were growing from the rootstock and the scionwood didn't look

particularly promising.

and

there were no sprouts yet from the rootstock either. But I assumed that

the grafts on the last two plants had failed. After all, the plants in

question were growing from the rootstock and the scionwood didn't look

particularly promising.

You may recall that the purpose of this experiment was to save two plum trees who were flattened by snow falling off the barn roof last winter.

Of those trees, one perished...but luckily the deceased was the same

variety as one of my successful grafts! The second tree is alive

(although not thriving), so I decided to try budding active growth from

that variety onto two of my failed rootstocks.

But imagine my surprise

when I removed the parafilm from one of the "failed" grafts and saw the

above. That green stuff growing between rootstock and scionwood...could

that be cambium beginning to join the two pieces of wood together? I'm

not positive, but decided it wouldn't hurt to give the tree a little

more time to get its act together. So I rewrapped the graft, plucked off

the rootstock sprout (to give the plant notice that it needed to sprout

from the scionwood) and set it back in the low light of our living

room.

The second failed graft,

though, was truly failed. The scionwood came right out and there appears

to be no life (green) left in the wood. Time to try again with

budding...in tomorrow's post!

The store

bought paper mulch product

we tried last month is doing a good job at blocking sunlight to the

weeds, but don't expect it to stay black more than a few weeks.

When grafting during the growing season, most people turn to some permutation of budding

(aka bud grafting). The idea is that you cut a bud off the variety you

prefer, slip the bud into an incision in the bark of the rootstock, let

the wound heal, then bend down the rootstock's top growth to prompt a

new stem to grow out of the transplanted bud. Yes, this technique does

require more TLC than the simple whip-and-tongue grafts used during the

dormant season, but budding is much more successful than dormant

grafting on stone fruits like peaches and plums.

This is my very first

time budding, so I did the deed with book in hand (and without much

confidence). In other words --- who knows if this will work, so do some

research on your own before following my lead!

The first step was to

make a T-shaped incision in the side of the rootstock. You want to cut

down through the cambium (green layer) so the bud can slide all the way

underneath, right up against the wood. I've been told it's easier to do

this step in August, but I was able to pry the cambium up in early May.

Next, I sliced a bud (and

the surrounding wood) off a growing stem on the plum tree I want to

propagate. (See photo at top of this post.) I snipped off the leaf, then

slid the bud down  into the incision on the rootstock.

into the incision on the rootstock.

The top of the scionwood

above the bud is just a handle. So once the bud was in place, I cut the

scionwood off flush with the top of the T incision.

Next, I wrapped the graft

carefully, leaving an opening for the bud to burst through. Now it's

time to wait a month or two (or more?) and then see if I can get the

scionwood bud to grow!

Now I see why the experts recommended that I try dormant grafting my plums.

Sure, my success rate so far using that method has only been 40%

(possibly as high as 80% when all is said and done), but at least I knew

within a month whether the grafts had healed! Patiently keeping an eye

on my budded plum this summer will probably be the hardest part of this

new experiment.

I made two Big City trips

this past week to pick up straw.

This post is to help me

remember that the load rides a bit smoother when I leave the tailgate

down and ratchet strap from the wheel wells.

It was 8 dollars a bale.

Quite a jump up from last year.

I read a lot of blogs

written by aspiring and actual homesteaders, and one theme that often

comes up is --- "This simple life isn't all that simple, is it?"

Of course, the bloggers

are right. The intricacies of growing your own food and trying to be

more self-sufficient can be daunting and exhausting. But I find that the

complicated lifestyle simplifies me.

I was thinking about this

over the weekend while enjoying our usual weekly Mark-mandated respite.

"I'm a pretty boring person," I thought as I loosed the goats in the

floodplain, then settled down with a book to watch them graze. Lamb Chop

curled up in the crook of my legs and I reached down to scratch that

itchy spot at the base of his horns. In that moment, all of us (boring

or not) were 100% happy.

After a couple of hours,

even Abigail was starting to waddle as she walked, and I figured it was

time to come home. Standing, I saw for the first time a huge patch of

yellow flags --- a wild water iris that I rarely see --- about thirty

feet away from my resting spot. Even though I'd walked directly toward

the flowers while heading out for our weekend browse, I hadn't noticed

the blooms until I rose at last, my head completely emptied by an

afternoon with a novel and three goats.

And that, to me, is the

purpose of the simple life. When my usually far-to-busy brain slows down

and completely empties, when I can't think of anything I want that's

not within reach of my fingertips, when the sight of a flower makes me

happy...that's the simple life.

Our Hardy Kiwi got nipped by the recent Dogwood Winter, but we've still got hope that the new leaf life will lead to flowers and then fruit.

As I've mentioned, I like parts of both the Warre and Langstroth hive systems. So even though we're currently converting our colony from the former to the latter,

I'm not ready to throw in the towel on Warre methods. Here are some

Warre components I'm considering incorporating into our new system:

As I've mentioned, I like parts of both the Warre and Langstroth hive systems. So even though we're currently converting our colony from the former to the latter,

I'm not ready to throw in the towel on Warre methods. Here are some

Warre components I'm considering incorporating into our new system:

- The insulated "quilt" box. I can't see anything not to love about helping the hive retain heat in the winter by adding a layer of insulation on top. However, straw doesn't seem to be the best filler material since it breeds ants. I'm thinking of transferring over to a sheet of solid styrofoam insulation in the next iteration of the hive.

- Leaving the bees alone as much as possible. In all honesty, I suspect this is why bees survive so well in Warre hives, and I hope to maintain hands-off methods despite returning to Langstroth boxes.

- Nadiring instead of supering. I'm undecided on this one. On the one hand, nadiring makes it possible for me not to disrupt the hive while still knowing when the bees need more space, since the empty box is just above the screened bottom board and can be examined photographically. On the other hand, nadiring becomes physically difficult once a hive reaches a certain size, and one of the reasons to return to the Langstroth hive is to get more (heavy) honey. I suspect I might use the modified Warre method of nadiring the first box or two in the spring, then supering for later honey flows.

By the way, I should

mention that the primary reason we're converting our Warre hive back to

Langstroth is because both places we ordered bees from this year fell

through. One company changed their shipping method to the US Postal

Service (which I'm okay with) but refused to insure the bees traveling

that way (which I'm not okay with). The other company pushed back their

shipping date twice and then threw in the towel and said they wouldn't

be sending out bees at all this year. Two refunds behind me, I figured

I'd better focus on the hive I have on hand. Maybe next year we'll be

able to expand our apiary and will be able to put what I'm learning this

year to use!

We carried the rest of our

straw up a hill that's equivalent to a few flights of stairs.

Anna improvised this clever

shoulder dolly from one of our cloth

tow straps.

The tow hooks transfer most

of the weight to her back and shoulders and away from the wrists.

I made our first trial

cheese! I suspect this is most people's first cheese because it can be

made with normal kitchen supplies --- a quart of goat's milk, 1/4 cup of

lemon juice, a jelly thermometer, a clean cloth, and a collander. Just

slowly heat the milk to 180 degrees, add the vinegar, watch curds form,

then strain through the cloth. Nearly instant cheese!

If you want, you can

finish by adding salt, garlic, herbs, or other seasonings. I kept it

simple with a dash of salt and found the cheese tasty, but nothing like

the goat's cheese I've had from the store. Instead, this simple lemon

cheese tasted more like mozzarella.

The amount of whey to

discard is rather daunting, though. A search of the internet turned up

the fact that there are two types of whey --- acid whey (which this is)

and sweet whey (from cultured cheeses). Sweet whey has scads of uses,

but acid whey is less malleable. So I'll probably end up giving the whey

to our animals (whichever one likes it best).

When I started

researching cheeses, most people reported that they soon moved on from

acid cheeses to cultured cheeses, and I can see why. Our lemon cheese

was tasty, but I prefer the more complicated flavors of cultured

cheeses. I guess it's time to bite the bullet and buy some cultures and

rennet....

Lamb Chop can now jump over

his kidding stall with almost no running start.

We debated making the wall

taller but decided to give him his own room.

There's almost too much going on the garden right now to post about. Time for a disjointed catch-up post!

There's almost too much going on the garden right now to post about. Time for a disjointed catch-up post!

The biggest deal this

week, as usual in the middle of May, is planting. May 15 is

traditionally our frost-free date, so everything I've been holding back

goes in the ground now. Tuesday I set out basil and sweet potatoes;

Wednesday Kayla and I direct-seeded corn, okra, and melons; and today

I'll seed butternut squash, summer squash, cucumbers, and bush beans,

then set out our sweet peppers.

As if that isn't fun enough, Friday is my icing-on-the-cake day. So I'll get to plant grape vines rooted inside over the winter out

in front of the trailer, then set out some flowers between them. A

great way to end planting week, with some long-term dreams and

short-term beauty.

In the perennial sphere, I

found time last Friday to summer-train our youngest apple trees,

although our older trees are still waiting for their turn. The photo

above shows our espalier

experiment (before I picked up the porch). I lopped off the top of the

tree this past winter and am now training two new limbs along angled

pieces of string. The third incipient limb was pinched off to maintain

symmetry.

Our normal high-density trees aren't so particular, but they do get the usual light pruning and heavy training

monthly in the summer. The only new innovation I came up with there is

to make simple spreaders out of asparagus stalks dredged up out of the

mulch at the base of the plants. A notch in each end and I have a

spreader that will hopefully stay in place until the little branches

solidify their shape.

Our normal high-density trees aren't so particular, but they do get the usual light pruning and heavy training

monthly in the summer. The only new innovation I came up with there is

to make simple spreaders out of asparagus stalks dredged up out of the

mulch at the base of the plants. A notch in each end and I have a

spreader that will hopefully stay in place until the little branches

solidify their shape.

Of course, weeding is

always on the agenda, although the task goes on the back burner during

planting week. I do a lot of hand weeding, but most of our soil is now

so good that the job is easy and fun...even when the beds are ignored

too long like around the asparagus plants shown above.

Speaking of weeds, I made

a mistake last winter by planting rye in my flower bed/grapevine area

in front of the trailer. While rye is a good cover crop, it's a weed in

my flower bed  because the plant is in the wrong place!

because the plant is in the wrong place!

Luckily, ten minutes of yanking up the grain reclaimed the space with no

hassle. Columbine and chamomile are now blooming, and most of the little herbs I set out there far too early

survived and thrived as well. With the ground finally bare, I poked

some scarlet runner bean seeds into the earth and set out some fennel,

borage, and nasturtiums one evening last week, so hopefully we'll have a

vibrant flowerbed in the near future.

Of course, it would take a

whole 'nother post to tell you about how all of our other garden plants

are faring. The cliff notes version is: first strawberry fruit Monday,

first pea flowers and tomato flower Wednesday, lettuce by the gallon,

asparagus finally starting to slow down from a daily dinner option to

tri-weekly. Delicious!

A quick left to right motion helps the Rye to lay in neat rows.

I went out with Mark to decide whether each rye bed was ready to be cut

or not, and in the process I was struck by the difference in biomass

production of various beds. My bed-by-bed approach to the garden means

that some beds are extremely rich from lots of manure and cover crops,

while other beds have managed to miss the boat on organic matter

accumulation. The latter beds produced rye plants less than half as tall

as the former beds with flower heads that are more like a quarter of

the size. Those puny beds will get to keep their rye mulch, while I'll

harvest the tops from the taller beds to use as mulch in other parts of

the garden.

I went out with Mark to decide whether each rye bed was ready to be cut

or not, and in the process I was struck by the difference in biomass

production of various beds. My bed-by-bed approach to the garden means

that some beds are extremely rich from lots of manure and cover crops,

while other beds have managed to miss the boat on organic matter

accumulation. The latter beds produced rye plants less than half as tall

as the former beds with flower heads that are more like a quarter of

the size. Those puny beds will get to keep their rye mulch, while I'll

harvest the tops from the taller beds to use as mulch in other parts of

the garden.

Kayla reminded me that it was also time to take the first set of measurements from our broadfork experiment. The first bed I looked at was the mangels in the photo below. The top half of the bed was broadforked while the bottom half wasn't.

Aha! I thought. Broadforking promotes better germination! (And boy do I need to thin those seedlings.)

Then I checked out the

other beds I'd included in my first experiment. Of those, one other bed

had germinated better on the broadforked side, two beds had germinated

better on the non-broadforked side, and two beds looked the same on both

sides. I guess there's not yet any clear result of broadforking on our

root crops...but Kayla and I went ahead and broadforked half of a few

more beds anyway to test out the results on summer crops.

Another pressing question I'd been meaning to follow up on was --- does a low of 27 nip our fruit-tree flowers? Unfortunately, the answer appears to be yes. The developing apple  fruit pictured above is the only one I could find on all of our trees, and the pear fruits I'd been keeping my eye on have since dropped off.

fruit pictured above is the only one I could find on all of our trees, and the pear fruits I'd been keeping my eye on have since dropped off.

On the other hand, there's at least one flower bud on one of our hardy kiwis. So maybe we wrote them off for the year too soon?

I'm starting to wonder if

it would be worth making little anti-deer enclosures in other parts of

the property just to see whether a hilltop location would beat these

perilous late freezes. Of course, the smarter solution would be to

scatter max-min thermometers around all the places I'm interested in

during next year's dogwood winter before going to all the trouble of

planting fruit trees outside our core perimeter. Something to ponder on a

cold winter night....

The big excitement for our

goats this week was some pasture expansion.

We decided to delete one of

the cattle panel walls to double the area where they like to hang out

when not being tethered to a fresh spot where the greenery is young and

lush.

If

one of your fruit trees dies a wintry death, but the yank test says

there's still life left in the roots, you can choose to either wait a

year and then graft onto that rootstock, or to turn the area into a

rootstock-propagation zone. I opted for the latter with the

winter-killed apple tree shown above.

If

one of your fruit trees dies a wintry death, but the yank test says

there's still life left in the roots, you can choose to either wait a

year and then graft onto that rootstock, or to turn the area into a

rootstock-propagation zone. I opted for the latter with the

winter-killed apple tree shown above.

If you're interested in propagating apple rootstocks, you should read this post first since it explains the whys and hows of stooling. Do it now. I'll wait.

Are you back? Okay, so

you'll notice that my winterkilled apple sent up five sprouts of various

sizes from the rootstock (the largest four of which you can see in the

photo above). The Grafter's Handbook

recommends waiting until those sprouts are five to six inches tall (I

waited a bit too long), then hilling them up just like you would a bed

of 'taters.

The idea is to cover

about half of each sprout's length with earth, and it's worth taking

some time to work the soil in with your fingers to thoroughly fill all

the air gaps between sprouts. Once the sprouts grow a little higher,

I'll hill a little more so I continue to have half of each stem's length

(hopefully six to eight inches by the end of the season) buried in the

soil.

(You'll notice we also

fenced the little scratchers out. Always a good idea to make sure your

chickens don't knock down the mounds of soil you build up....)

Varieties are chosen to

be rootstocks in part because they're keen rooters, so in my official

stooling areas, I chopped the tops off the one-year-old trees in early

spring and stuck those tops halfway into the ground several inches away

from the original stool. In the photo above, the stem is on the left and

the rootstock is on the right (by the rebar). As you can see, both

parts of the tree are currently leafed out and growing. Since this stool

is younger than the one shown in the previous photos (one year old

versus 2.5 years old), it's not as advanced and won't be hilled for a

few more weeks.

The good news is that it

looks like, if everything goes smoothly, I won't have to buy apple

rootstocks this year. Now, the question is, where will I put another

half dozen home-grafted apple trees?

Our new chicks have gotten big enough to need another layer of bricks under their EZ Miser bucket waterer.

Option A involved a type of very thin, biodegradable black plastic.

The photo above shows Kayla helping me lay down the plastic three weeks

ago. The photo below shows completely dead oats underneath the plastic

this past Thursday.

This

product worked much faster than I thought it would, probably because

we've had crazy summer weather in April and early May (highs up to 90

some days), which surely heated up the soil underneath very quickly.

This

product worked much faster than I thought it would, probably because

we've had crazy summer weather in April and early May (highs up to 90

some days), which surely heated up the soil underneath very quickly.

On the down side, all it took was Huckleberry walking across the plastic

to tear little holes, which a light wind quickly turned into long

tears. (I'm telling you Huckleberry really isn't that big of a cat!) So,

although effective, I'd caution against using this product anywhere

that pets will be walking even a little bit.

Option 2 was solarization, which I explained in more depth in this post.

The solarization worked about equally as fast as the black plastic,

with the bonus that this clear plastic didn't shred after light pet

traffic. The clear plastic also held in the soil moisture, which was

handy since rainfall for the last few weeks has been nearly nonexistant.

Option 2 was solarization, which I explained in more depth in this post.

The solarization worked about equally as fast as the black plastic,

with the bonus that this clear plastic didn't shred after light pet

traffic. The clear plastic also held in the soil moisture, which was

handy since rainfall for the last few weeks has been nearly nonexistant.

The downside of

solarization is that my raised beds in this area are tall enough that

the north-facing side of the bed didn't heat up fully, so the oats

underneath the plastic on that side are still somewhat green. So if you

plan to use solarization to prepare soil, you'll want to stick to areas

where the ground is as flat as possible. With that caveat and assuming

hot weather, you can also plant into solarized ground in about three

weeks if your weeds are only moderatly tenacious. (Add a few more weeks

for both Option A and Option B if you're trying to kill a wily perennial

like wiregrass.)

Option 3 was a storebought roll of paper mulch.

This mulch was the least effective as a fast weedkill, although it

looks to be the most effective as a long-term ground cover.

Option 3 was a storebought roll of paper mulch.

This mulch was the least effective as a fast weedkill, although it

looks to be the most effective as a long-term ground cover.

As Mark mentioned,

the first rain bleached the dye out of the paper, and the lighter color

left behind meant that the mulch simply acted like a barrier between

the weeds and the sun rather than heating the soil underneath. The

result is that the weeds beneath the paper mulch aren't quite dead yet,

although the paper is still providing a good barrier around the

high-density apple trees. I suspect I'll need to wait about 4 to 6 weeks

between laying down this mulch over an oat cover crop and planting into

the bare soil.

As another downside, Lucy running across the mulch did

poke holes in the paper layer, allowing some weeds to come up through.

That said, the paper has much more structural integrity than the very

thin black plastic, so only the paw-print areas were affected rather

than the whole sheet of mulch. So I'd say the plastic mulch is

acceptable over areas with light pet traffic.

Option 4 was mad of

entirely free materials, but I didn't lay them down until later than the

previous options and thus don't have a comparison yet to the other

methods. Kayla's father came through with a big box of newspaper

(thanks, Jimmy!), and I've been applying the sheets using different

methods in different parts of the garden.

The

photo to the left shows how I laid the paper down dry and then anchored

it with deep-bedding material from the goat coop. Unfortunately, some

of the sheets have blown away, which is why I started soaking the paper

in a bucket of water before applying.

The

photo to the left shows how I laid the paper down dry and then anchored

it with deep-bedding material from the goat coop. Unfortunately, some

of the sheets have blown away, which is why I started soaking the paper

in a bucket of water before applying.

The top photo in this

section shows some newspaper-mulched areas around the hazelnut bushes.

Since I have comfrey plants growing along the aisles in that part of the

garden, it was easy to yank handfuls of the greenery as a short of chop-'n-drop

to weigh the wetted newspapers down. I'll post a followup in a few

weeks once I know more about how the newspaper mulches compare to the

other methods, but my guess is that they'll be comparable to the

storebought paper mulch.

The final method I'm trying is a more long-lived type of black plastic

that is supposed to be good for 12 years (assuming you don't puncture

the fabric in the interim). I laid down an experimental span in the

proto-tree-alley a week ago, with the plan of taking up the plastic at

the end of the month and planting sweet potatoes there. I'll keep you

posted about weed control there as well.

Phew! I know that's a lot

of data, but I hope it'll help you decide on a weed barrier that'll fit

your particular garden needs. And perhaps there's another method I

haven't considered that you've used with success in your garden? Be sure

to let me know in the comments!

Our asparagus is slowing down, but the strawberries are just getting started.

I suspect one of the

reason women love goats is because the caprine herd has the exact

opposite problem we have. As a goatkeeper, one of your primary goals is

to keep the weight on

your goats. Between intestinal parasites (usually present at low levels

but sometimes veering way out of control) and the energetic expense of

creating baby goats and milk out of grass, dairy goats have a bad

tendency to waste away to skin and bones. Enter my weekly bout with the measuring tape to reassure myself that our goats are in fine form.

Lamb

Chop has never given me any worries on the weight front, though. The

most I've been concerned about is that our buckling will get bigger than

his mother before his date with the butcher, making it impossible to

carry the lad across the creek to his doom. Barring that issue, he seems

bound to surpass his 11-month-old herdmate's size in short order. As of

this week, Lamb Chop has officially caught up with Artemesia; in fact, I

think he now stands a little taller at the shoulder.

Lamb

Chop has never given me any worries on the weight front, though. The

most I've been concerned about is that our buckling will get bigger than

his mother before his date with the butcher, making it impossible to

carry the lad across the creek to his doom. Barring that issue, he seems

bound to surpass his 11-month-old herdmate's size in short order. As of

this week, Lamb Chop has officially caught up with Artemesia; in fact, I

think he now stands a little taller at the shoulder.

Abigail and Artemesia, on

the other hand, worried me a bit in April, although I now think that

their weight "losses" then were merely an artifact of shedding their

winter fur. Less fur for the tape to wrap  around

simulates the loss of fat. Regardless, I dosed the whole herd with

daily helpings of chopped garlic, which they all ate happily whether or

not they needed the herbal dewormer. Now both are well above their

winter weights, even without the furry padding.

around

simulates the loss of fat. Regardless, I dosed the whole herd with

daily helpings of chopped garlic, which they all ate happily whether or

not they needed the herbal dewormer. Now both are well above their

winter weights, even without the furry padding.

I'm glad that I seem to be able to keep the weight on Abigail without adding grain

to her diet, but I'll admit that I'd probably get more milk if I fed

our doe more concentrates. As she started gaining weight on grass, I

started easing off the carrots, alfalfa pellets, and sunflower seeds I

was offering...with the result that milk production slowed down a bit

(from about 3 cups a day to about 2.5 cups a day). Bringing those

concentrates back up to previous levels (plus locking Lamb Chop away an

hour earlier in the evening) quickly increased milk back to normal, then

all the way up to a quart at my morning milking.

I suspect one of the dicey issues with dairy goats is deciding when

we're being greedy humans and pushing our goats too hard, and when it's

worth feeding a little more for a little more milk. Since I want to

experiment a bit more with cheese, I think I'll be greedy just a little longer.

When I get this one done we'll have 3 paddocks we can cycle the goats through.

After deciding that our first cheese --- an acid cheese --- was too simple, it was time to move on to a cultured cheese. I followed this recipe for neufchatel, which uses buttermilk as the starter culture and rennet to make the curds separate from the whey.

Rennet, I learned when

hunting down these supplies, comes in several forms --- liquid animal,

liquid vegetable, tablets, and powders. The powders are usually for bulk

purchasers, tablets have a very long shelf life, liquid animal is easy

to utilize in small quantities for fractions of the recipe, and liquid

vegetable (as best I can tell) is a slightly bitter replica used by

vegetarians. Since I wanted to be able to try half recipes, I opted for this liquid animal rennet.

I'm not going to run

through all of the instructions for making this cheese since you can

find them at the link in the previous section. The shorthand version is:

take 2 quarts of room-temperature milk, add two tablespoons of cultured

buttermilk, dissolve two drops of liquid rennet in a quarter of a cup

of water and add to the milk mixture, stir, then cover and let sit for

about eight hours. You'll know your cheese is ready for the next step

when you see a clean break as is shown above.

Now you're ready to cut the curds...

...and drain off the whey

by pouring the contents of your pot into a clean towel in a colander.

You're then supposed to hang this bag of proto-cheese for a while until

the rest of the whey works its way out, but I was impatient and simply

squeezed the bag, stirred the contents, and then squeezed some more

until the cheese was dry. (Someone please tell me why this method is

wrong --- it seemed to efficient!)

The final result gets half a teaspoon of salt mixed in and is then ready to eat!

Mark and I tasted the neufchatel (top container), the same cheese mixed with some Hollywood sun-dried tomatoes,

and ricotta made from the whey. (More on the ricotta in a later post.)

Mark doesn't like goat cheese from the store, but he enjoyed this

completely non-goaty cheese...while I actually missed the goatish

overtones. Meanwhile, I've never been a fan of ricotta, but I thoroughly

enjoyed the homemade version, while finding the Neufchatel a bit bland.

As best I can tell, the

reason this cheese is neufchatel instead of chevre is because it uses

buttermilk as the starter culture. However, when I looked up the biology

of chevre and buttermilk cultures, I learned that both contain some

combination of Lactococcus lactis lactis, Lactococcus lactis cremoris, Lactococcus lactis diacetylactis, and Leuconostoc mesenteroides cremoris.

It's probably still worth buying a chevre culture to see what I come up

with using the other starter since my taste buds say this Neufchatel

isn't the same as chevre.

This sliding bolt gate latch is my new favorite way to keep goats out.

I'll

admit that when my parents made lasagna with ricotta when I was a kid, I

tried to pick around the grainy cheese. But I now that I'm

experimenting with cheesemaking, I've learned the purpose of ricotta ---

turning all that cultured whey into something useful. And, sure enough,

two quarts of milk turned into 9.5 ounces of neufchatel,

while leaving enough proteins in the whey to create another 2.9 ounces

of ricotta. Thus, I've decided this subtly acidic cheese is hereafter to

be referred to as "bonus cheese."

I'll

admit that when my parents made lasagna with ricotta when I was a kid, I

tried to pick around the grainy cheese. But I now that I'm

experimenting with cheesemaking, I've learned the purpose of ricotta ---

turning all that cultured whey into something useful. And, sure enough,

two quarts of milk turned into 9.5 ounces of neufchatel,

while leaving enough proteins in the whey to create another 2.9 ounces

of ricotta. Thus, I've decided this subtly acidic cheese is hereafter to

be referred to as "bonus cheese."

(Okay, not really. You can keep calling it ricotta. But doesn't "bonus cheese" sound good?)

Ricotta is almost too

simple to post about. You take your leftover whey and allow the liquid

to sit, covered, at room temperature for 12 to 24 hours. Next, boil to

separate the curds from the whey, then strain out the chemically altered

(greenish) whey off your new cheese.

The boiling step is

supposed to be a near-boil, using a double boiler to heat the cultured

whey to 203 degrees Fahrenheit. However, after an hour in our double

boiler, the whey was beginning to separate out little curds...but still

hadn't surpassed 180 degrees. Only after decanting the whey into a pot

to cook it the rest of the way directly on the stove, at which point it

boiled at around 198 degrees Fahrenheit, did I realize that I really

should have factored in changing boiling temperatures due to elevation.

(Or, perhaps, the fact that my candy thermomter might not be accurate?)

So, to cut a long story short --- you can make ricotta just fine by

simply bringing the whey to a boil then removing it from the heat.

Anyway, after you boil

your whey, you let it cool for a couple of hours, then pour the curds

and whey into a clean cloth above a strainer. I used our new straining funnel for this step.

You'll also notice that I

moved to a white cloth instead of the colored one I'd used for my

previous cheeses. I learned the hard way that cheese picks up a little

bit of lint from the cloth, which is unsightly if the fabric is colored.

But if the cloth is white, no one ever knows....

I actually loved the

flavor of this ricotta plain, but I'm thinking of trying it in a

chocolate cheesecake with some of the neufchatel. Because everything tastes better with a little chocolate....

The Star Plate goat barn now has a third door to access the new paddock.

Despite some bird

pressure that's been forcing me to pick berries a little on the pale

side, we've been enjoying delicious strawberry desserts for the last

week and a half or so. That said, I've decided it's finally time to pull

the plug on our Honeoyes. Not the variety

--- this early season strawberry is still a favorite. But after

expanding my patch from gifted expansions of someone else's patch for

the last eight years, viruses (I assume) are building up in the clones

and the berries are slowly becoming less flavorful. When even I want a little honey on my fruit (unlike Mark, who always does), I know that it's time to make a fresh start.

And, while I'm at it,

maybe I should try a second variety as well? Now that Kayla's in my

life, I can get away with ordering 25 plants of both Honeoye and Galleta

(an ultra-early variety) without worrying that the new plants will take

over my entire garden. Last year's addition of Sparkle

was a great boon to our homestead, so hopefully Galleta will be as

well. And even though the plants cost 70 cents apiece once you add in

shipping, when you figure that they and their children will likely feed

us for another eight years at a rate of at least a gallon a day, the

plants are definitely a bargain! That's my kind of homestead math.

Our Oregon

battery powered chainsaw

needed a new chain today.

The sharpening stone still had

about 1/4 of its surface area left, but one close look at the teeth

will tell you why it stopped cutting.

I like to flip the bar upside

down when a new chain goes on to even out the wear on the little bar

sprockets.

We are very happy with how

much cutting we got done on the first chain.

The weather and I can be

moody. After a crazy wet fall, winter, and spring, we started measuring

precipitation in hundredths of an inch this month. A quarter of an inch

of rain Thursday morning eased the earth's woes a little, but it took

Mark's cheerful demeanor and calm problem solving to ease my own bad

mood.

You'd think I'd realize that I always

get overwhelmed around the middle to the end of May. I keep a mood

diary (who, me obsessive?) and this is the time of year when my homemade

cheerfulness report card dips into Cs and Ds. All of the spring

plantings need to be weeded, our chicks are growing out of the easy

stage and require more frequent pasture changes, and learning goats has

also added to my load this year.

The trouble is, I love

the garden and chickens and goats. I just don't love it when a lengthy

to-do list pulls me out of my slumber too early and I turn irritable and

grumpy. Time to offload a few tasks.

Some chores are easy to

spread around. I pull Mark off his normal tasks to help me for a morning

in the garden, and together we move the chicks to a new bit of yard.

After a lesson in goat tethering, we figure he can halve my chores there

too.

But some headaches aren't

lighter when carried on two sets of shoulders. For example --- Lamb

Chop. At eleven weeks of age, our buckling is enormous, still

nursing...and starting to get ornery. Artemesia went into her first

clearly discernible heat this week, which suddenly made goat wrangling

much more difficult. Between the screaming from the woods, Lamb Chop's

need to mount our doeling in the middle of the garden, and the

egg-laying snapping turtle guarding the path on the way home, I was glad

Mark was along or I don't think I would have been able to get all three

goats back into the pasture. So our buckling has a date with the local

butcher (aka meat packing facility) in two weeks, and we'll just hope

Lamb Chop manages to knock Artemesia up beforehand.

Speaking of offloading, I've decided to let my Winter and Spring cookbooks stand alone for the moment. I had thought my book about living in a trailer

would be my most controversial and criticism-inspiring text, but

apparently our unusual food choices are much more divisive. Lacking the

energy to push a product that the world isn't ready for, I'm moving on

to one of the other creative projects that I always have waiting in the

wings.

Decisions made and tasks

offloaded, I step out into the garden and notice that the grass is

green, the flowers are beautiful, and the garlic scapes are ready to

eat. It's amazing what a shift in perspective will do to remind me that,

despite temporary troubles, we're still living in paradise!

Some of our onions

started sprouting and going bad on us.

This post is to remind me

around next Mother's Day to delete any bad onions.

"I don't want to go out," Abigail said on Wednesday morning when I went to tether our little herd in the woods.

I was gobsmacked. Abigail not only always wants to go out, she wants to get to her fresh forage now, ASAP, hurry up, do you get the message?!

But I think the deer

flies the day before got to be too much for her. We had a light rain in

the morning, so I put the herd out later than usual. And when I went to

bring the goats home, the pesky deer flies were buzzing in their loops

so annoyingly that I was barely able to gather three goats before

rushing for cover myself. I should have worn a hat...and I'm sure that,

as a tethered goat, the deer flies were twice as annoying. (They do

bite, but it's really the buzzing that drives you mad.)

So

I met Abigail in the middle. I tethered her out early, took her in a

bit after lunch, then cut some locust boughs in the evening to top off

her belly. No, Mark, I don't know what you're talking about when you say

I spoil our goats....

So

I met Abigail in the middle. I tethered her out early, took her in a

bit after lunch, then cut some locust boughs in the evening to top off

her belly. No, Mark, I don't know what you're talking about when you say

I spoil our goats....

More seriously, I do

dream of eventually having large enough pastures so our goats can get

all of their nutrition on their own schedule, retreating to the barn

when necessary to beat the flies. In the interim, tree boughs seem to be

a quick-and-easy solution for supplemental feeding when it doesn't make

sense to bring the goats out into the woods to eat. Like tree hay...but for summer nutrition rather than winter feed.

Kayla's husband Andy helped

us out with some firewood cutting yesterday.

He gave us 2 hours of

aggressive tree cutting for only 50 dollars.

If you're within driving

distance and need some trees cut leave a comment and we'll give him

your number.

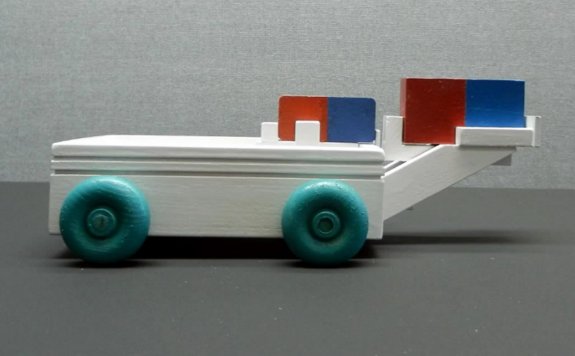

I saw a perpetual motion

Youtube video recently

that tickled my curiosity.

Anna was intrigued as well,

so we ordered some pinewood

derby wheels and a box

of magnets to see if we

could understand this puzzle a little better.

We had fun tinkering with it

for a few evenings before we came to the conclusion that the video is a

trick that uses gravity instead of magnetism to move the car.

After some research and great input from our readers, I decided to make a few changes before repeating my neufchatel/chevre

endeavor. First, even though the instructions called for two drops of

liquid rennet in my half-gallon recipe, raw goat milk is notorious for

not needing nearly as much thickening agent --- pure milk is just very

alive. So this time around I backed off to one drop of rennet, looking

for more of a soft cheese consistency instead of the more chewy cheese I

ended up with last time.

After some research and great input from our readers, I decided to make a few changes before repeating my neufchatel/chevre

endeavor. First, even though the instructions called for two drops of

liquid rennet in my half-gallon recipe, raw goat milk is notorious for

not needing nearly as much thickening agent --- pure milk is just very

alive. So this time around I backed off to one drop of rennet, looking

for more of a soft cheese consistency instead of the more chewy cheese I

ended up with last time.

I also decided to try to

boost the flavor with a bit more buttermilk (three tablespoons instead

of two) and a much longer culturing period (24 hours instead of 6,

although I should mention that the weather was much cooler during round

two). After that elongated culture period, there was quite a bit of

clear whey on top of the curd, and the curd had also begun to pull away

from the walls of the pot. This is all an effort to give the bacteria

more time to work, since I suspect microbial byproducts are what gives

soft cheese most of its flavor.

Finally, I drained the

cheese the right way for four hours instead of squeezing out the whey,

and I upped the salt to 0.75 teaspoons. The result? Nearly perfect! The

salt was too much --- I'll be going back down to half a teaspoon next

time around --- and I think the culturing period might have been just a

hair on the long side as well. But the flavor was much more full-bodied

than last time and the cheese felt much moister rather than dry and

crumbly. Success!

My young flower beds aren't quite to the stage where they stand up to distance shots, but the closeups are delightful.

Foxgloves from a family friend, chamomile because it reminds me of my

mother (who enjoys the tea), columbine from another friend, borage (not

quite blooming yet) because one of our blog readers suggested it as a

high-quality feeder of native pollinators, some zinnias and nasturtiums

(also not blooming yet) just because.

Every time I look at one of the plants, I smile!

One of the Teva

sandals I glued for Anna last year came apart.

I used JB

Weld again because the

other sandal is holding up nicely.

The plan is to use some

Plumbers Goop to seal up the edges to keep any water or dirt from

finding a way in.

I set out ten persimmon seedlings in our chicken pastures 2.5 years ago,

figuring there were all kinds of experimental possibilities for the

young trees. Option 1 would be to simply let them grow up to adult size,

but a seedling persimmon has a 50/50 chance of being male (meaning no

fruit), grows very large, and takes a long time to bear. Option 2 (my

favorite at that time) was to graft hardy Asian persimmons onto the

seedling rootstocks...but my hardy persimmon varieties kept dying back

to the ground over the winter, so I decided to ditch that plan. Instead,

I moved on to option 3 --- to trade for named American persimmon

varieties (Yates, Proc, I-94, and Early Golden) and graft those onto my

seedling rootstocks.

I set out ten persimmon seedlings in our chicken pastures 2.5 years ago,

figuring there were all kinds of experimental possibilities for the

young trees. Option 1 would be to simply let them grow up to adult size,

but a seedling persimmon has a 50/50 chance of being male (meaning no

fruit), grows very large, and takes a long time to bear. Option 2 (my

favorite at that time) was to graft hardy Asian persimmons onto the

seedling rootstocks...but my hardy persimmon varieties kept dying back

to the ground over the winter, so I decided to ditch that plan. Instead,

I moved on to option 3 --- to trade for named American persimmon

varieties (Yates, Proc, I-94, and Early Golden) and graft those onto my

seedling rootstocks.

Persimmons are trickier

than some other fruits to graft, so I tried two different approaches. I

also followed the experts' advice by waiting until it seems far too late

to graft --- late May when the leaves on the seedling trees were nearly

fully formed.

The first step for both methods, though, was the same --- yank out the

weeds that had grown up within each tree's enclosure since the last time

I dropped by. Out in the chicken pastures, these little trees are lucky

to catch my eye more than once a year, so I wasn't surprised to find

that two of my seedlings had died and that one wasn't big enough to

graft onto. The rest --- despite being a bit winter-nipped from our -22

Fahrenheit cold spell --- had stems thick enough to graft onto.

I grafted the first four plants before doing any research, so they got my usual whip-and-tongue graft.

It was definitely tougher to graft in situ than to bench graft, and

both the rootstock and scionwood were on the small side (compared to

apples) for most of the trees, so I'm not sure how many will take.

I grafted the first four plants before doing any research, so they got my usual whip-and-tongue graft.

It was definitely tougher to graft in situ than to bench graft, and

both the rootstock and scionwood were on the small side (compared to

apples) for most of the trees, so I'm not sure how many will take.

After I was done grafting, I still wasn't entirely sure what to do with

the existing growth on the trees. So I just cut the branches back but

left some leaves present to keep the tree alive until the graft union

heals. Again, I'm not sure if this was the best choice, or whether the

existing growth will prevent the graft union from healing. I guess time

will tell....

While I took a water break in front of the computer, I found this interesting file

suggesting an alternative method of grafting persimmons, so I followed

the author's lead for my last three trees. First, I snipped the entire

top off each seedling, then I slit a strip of bark and peeled it down

(carefully!) before cutting away a bit of the rootstock to make room for

another stick of wood to fit in.

While I took a water break in front of the computer, I found this interesting file

suggesting an alternative method of grafting persimmons, so I followed

the author's lead for my last three trees. First, I snipped the entire

top off each seedling, then I slit a strip of bark and peeled it down

(carefully!) before cutting away a bit of the rootstock to make room for

another stick of wood to fit in.

Next, it was time to prepare the scionwood by cutting one side of the

bottom at a slant and then using the knife blade to scrape the bark on

the rest of the bottom of the scionwood down to the green cambium. The

prepared scionwood slid under the rootstock's bark flap, and the whole

thing was wrapped with parafilm. (Okay, I didn't wrap my entire piece of

scionwood since that just seemed too extreme, but I may regret that

omission!)

With seven trees grafted to four varieties, I'm hopeful I'll see at

least a 50% success rate and will end up with several different types of

persimmons to continue their slow growth in the chicken pastures. Since

the trees there don't get much TLC, chances are I won't see fruit until

2020, but hopefully the results will be worth the (very little) effort

I've so far put into my experimental trees.

It's been a few years since we hooked up sprinklers in the back garden. But the groundwater has sunk too low for subirrigation to do much good.

In preparation for planting another round of beans, corn, and squash, we

let the sprinklers run all day to moisten the parched earth.

It's that time of year again --- the season for weekly doting upon our tomato plants! The first round of pruning

is simple --- I snip off the bottom leaves so none are touching the

ground, then I pinch off any suckers, no matter how small. If suckers

have grown too large to pinch,  I instead cut them with clippers. Then I look at the many beautiful bloom buds (and the open flowers on the plants I set out a week earlier) and smile for the rest of the day.

I instead cut them with clippers. Then I look at the many beautiful bloom buds (and the open flowers on the plants I set out a week earlier) and smile for the rest of the day.

That said, I am doing a few things differently this year. Most significant (I hope) will be growing only blight-resistant varieties

(although given our current weather, blight might not be an issue this

year anyway). I've also set out plants much closer together than usual

and am pruning each to one main stem instead of to three. I feel like my

previous efforts to beat the blight with maximum air flow between

plants didn't do much good, so why waste space?

On a different note, I'm

not surprised but I continue to be charmed by how the earth perks up

so-so transplants. I started another set of seedlings in early May just

in case my started-too-early transplants didn't make it, but I've only

had to replace two of the first round of thirty transplants. Within a

week of hitting real soil, everyone else perked up and grew happy new

leaves, proving that our natural ecosystem is 100% better than anything I

can replicate in pots in a sunny window. If I was listing the top ten

things I love, growing in real earth would be one near the top of the

list!

We decided our tomatoes

needed a drip irrigation system.

This white PEX

material is cheap and

easy to work with. It won't kink and you can get a 100 foot roll for

less than 30 dollars. Once I had the tubing secured to each post I went

in and drilled a small hole next to each plant.

The hole is three times

bigger than most drip systems due to the heavy sediment in the creek

water we use for irrigation.

An unusually dry May has

its pros and cons. On the plus side, if the summer stays like this, our

garden may bypass its usual wide range of fungal diseases. And, already,

the weeding pressure is much lower than in normal seasons...

...because the weed seeds simply aren't sprouting. Unfortunately, unless I give them some TLC, neither are the vegetable seeds.

Usually, the only times I have trouble with seed germination are in early spring (pushing the envelope with cold soil)

and in midsummer (when I plant cool-loving fall crops that aren't

impressed by summer heat). But, this year, I'm having to replant some of

my usually dependable vegetables --- like green beans and sweet corn

--- because even the sprinklers aren't enough to get them off to a good

start. Heaven forbid I try to plant (the way I usually  do) outside the spread of our irrigation system.

do) outside the spread of our irrigation system.

Luckily, the lack of a

spring this year is actually working in my favor. It was cold so late

into the so-called spring that I started lots of transplants inside, and

most are loving their new habitats in the garden. Those pre-sprouted

beans I mentioned a few weeks ago failed miserably --- only three of the

nine plants survived --- but I've been snipping off a few basil leaves

here and there for the last two weeks, and our pepper plants are up and

running.

Meanwhile, the summer

vegetables that I started before the weather turned dry --- either under

quick hoops or just early in the garden --- are also doing well. I hope

to see cucumber blooms next week and maybe we'll eat the first broccoli

head at the same time. The heat is  giving

some plants pause --- notably the peas (currently producing) and

crucifers, who wilt a bit in the afternoons even if they've been

recently watered. But, overall, these early vegetables seem to be

thriving beneath the bright summer sun.

giving

some plants pause --- notably the peas (currently producing) and

crucifers, who wilt a bit in the afternoons even if they've been

recently watered. But, overall, these early vegetables seem to be

thriving beneath the bright summer sun.

I still can't decide if I

should be wishing for rain. Everyone else is --- non-rotational

pastures in the area are brown and nearly bare and unwatered gardens

aren't doing much better. But I keep thinking that if we have a few more

weeks of drought, we'll be able to drive in some manure....

Luckily --- since I'm so conflicted --- my wishes have no impact on the

weather at all. Rain will come when it comes, and in the meantime I'll

give my seeds a little daily water to make sure they sprout.

We got a big straw bale

delivery today.

80 bales at 5 dollars per

bale.

The guy felt bad about last

year's issue with seed heads and gave us a discount to make up for it.

Lamb Chop's date with the butcher was supposed to be coming up next week. But, soon after Artemesia's heat subsided... (R-rated information after the next photo)

...our buckling finally matured enough to do the deed.

Lamb Chop currently runs back and forth between our two does all day

long. "Can I nurse?" he asks mama goat, who is trying to wean him (with

little success). Next, he moves on to Artemesia and asks "Can we have

sex now?"

It used to be that

Artemesia would always reply: "Yeah, whatever," for which the internet

supplied an explanation. Apparently, a buckling can't actually poke his

penis out of its sheath until he hits a certain age. So our buckling was

merely climbing up on Artemesia's back, and our doeling is a gentle

enough goat not to mind being mauled.

However, this past week, I

finally saw penis extrusion, and Artemesia started saying "No!" every

time Lamb Chop asked for sex. Which means that, hopefully, waiting for

Artemesia's next heat cycle will result in baby goats in the middle of

November.

I hate to say it, but I

can hardly wait to see the back of our little buckling. He's actually

still quite sweet, but I've had to give up on tethering since he's

impossible to walk through the garden with two other goats in my hand.

Instead, our herd is subsisting on pasture goodies (less than a third of

their food at the moment), tree leaves from cut saplings,

and a daily guided walk into the floodplain. I dream of the time when I