archives for 03/2015

Two weeks ago, when the

snow and deep freeze hit our farm, spring ground to a halt. It wasn't

until this past Saturday that I felt like we were on the upward swing

once again. The snow is finally melting faster than it's falling, and

here and there bits of plant matter are beginning to poke above the

snow.

Hazel catkins loosening

and disgorging their pollen are nearly always the first spring bloom on

our farm. Like everything else, I noticed the first catkin just about

blooming before our snow storm...then the hazel bush went right back to

sleep. But with highs above forty forecast for most of the next week,

I'm betting the maple sap will start flowing and we might even hear frogs as our snow finally melts away. I sure am glad we don't live in the North!

Our two quick

hoops took some serious

damage this Winter.

It was twice the damage compared to the 2012

snow load.

I took these photos a

week ago, when snow had been on the ground for six days and I suddenly

had the realization that my poor honeybees might be smothering inside

their hive. I rushed out and brushed the entrance free, then pressed my

ear against each side of each  box. Nothing. Nothing. Nothing. And then --- there! --- a low buzz.

box. Nothing. Nothing. Nothing. And then --- there! --- a low buzz.

The colony sounded

awfully weak, which didn't really surprise me given the extremely low

temperatures we'd been experiencing. But, at the same time, I knew that

people successfully keep bees in much colder climates than ours, so I

hoped for the best.

Imagine my joy when I

went to listen again this past weekend and heard a louder hum. I think

the bees were just hunkering down during the extreme cold, and I now

have high hopes that they'll be able to make it until the first spring

flowers begin to bloom. The dandelions should be out in force within a

month --- hang in there, bees!

When the snow slid off the barn roof, I almost thought I could feel the ground shake.

Unfortunately, the plum trees

nearby were squashed by the avalanche. It looks like the snow danger

zone extends out for at least twenty feet from each side of the barn.

Good thing Anna ordered plum rootstock to bring our devastated trees back to life.

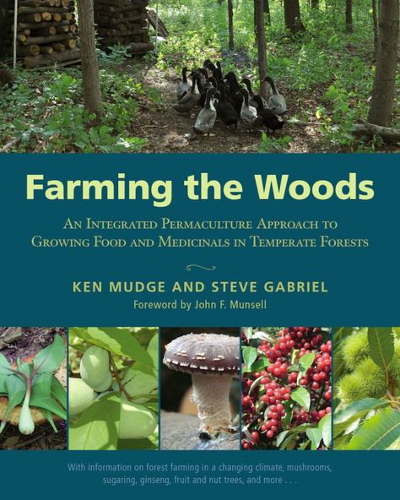

When I was reading up on

inoculating logs with shiitake mycelium, recommendations on log sizes

varied widely, ranging from 3 to 12 inches in diameter. Large logs tend

to fruit longer and to hold moisture better during dry spells. On the

other hand, small logs fruit faster and are easier to wrangle

(especially if you plan to soak logs to force fruiting).

One factor I didn't read about, but soon thought of once I started looking at the logs Mark cut for me,

is the sapwood-to-heartwood ratio. Shiitakes only eat the sapwood, the

pale-colored wood around the outer perimeter of the log. And bigger

logs, especially if they grew slowly in woodland settings, might have

three quarters of their volume made up of useless heartwood, leaving the

fungi far less food than you might think.

In case you can't pick

out the sapwood in the first photo in this post, here's a labeled

diagram to get you started. This log has been sitting around for a

couple of weeks --- the color difference is even more evident in the wet

wood of a newly cut log.

Looking closely at my

logs got me thinking that maybe the puny 3-inch treetops that I had

earmarked for firewood are actually better mushroom logs than these huge

logs that I'd originally considered prime fungi fodder. In fact, the

smaller-diameter logs have no heartwood at all, so they might contain

nearly as much sapwood as the log pictured above. Assuming I'm willing

to keep logs moist over the summer with sprinklers, perhaps little logs

are the way to go after all?

The decision will have to

be made soon because spring weather is finally upon us! Highs in the

forties and lows in the twenties means it's finally safe to pull the mycelium out of the fridge and inoculate those logs. Time to enjoy the March Into Spring!

We upgraded our goat

milking stand today.

The neck brace is now wider

and taller with a top piece to lock in place.

Everyday this week seems like

a possible baby goat day.

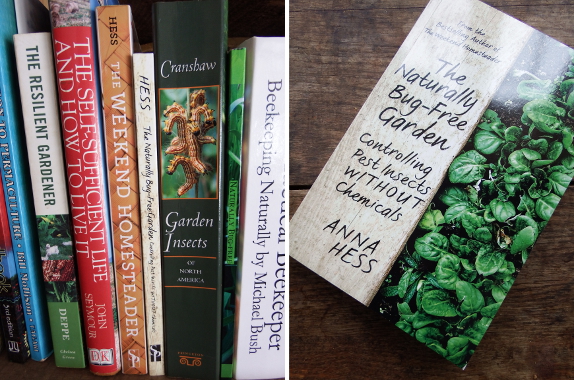

There's a new book on my shelf...and maybe on yours as well? I braved the flooded creek Tuesday to bring my first copy of The Naturally Bug-Free Garden home,

a copy that I ordered from Amazon since the box from my publisher is

running late. It was just too hard to wait any longer to hold my second

paperback in my hands....

Do you want to jumpstart

your 2015 garden with a primer on natural pest-control techniques? If

so, you can get order the paperback here:

Or

you can join in my launch treasure hunt and enter for a chance to win a

signed copy of your very own! Just head to your local library or

bookstore and ask if they have The Naturally Bug-Free Garden in stock, snap a photo of my book in the wild, then enter using the widget below. Or, if you've already bought a copy and want to win a copy for a friend, snap a shot of yourself with your new book! I'm letting this giveaway run for a full month so that you'll have time

to request your librarian stock a copy for even easier entries. (Yes,

strangely, I get even more of a kick out of hearing folks tell me that

they checked one of my books out of their local library rather than

buying their own copy.) May the hunt begin!

We trim the

goat hooves once a month, but let Abigail skip this month due to

her being a little grumpy about being wrangled with her extra weight.

Artemesia likes the attention

but wiggles a lot. I ended up holding her while Anna finished the last

hoof.

I feel like I'm living in

one of those nature documentaries where the ice pack is melting and the

grizzlies are hunting in flooded streams. Except the only thing hunting

in our flooded streams is ducks...who have finally stopped pouting in the coop and have slowly begun to lay once again!

As the snow melts, I

remember that a world exists beneath the white. Abigail will be thrilled

to learn that some of the oats have survived the deep freeze due to

their frosty blanket and will soon be dry enough to consume.

I'm finally collecting

sap again from the sugar maple and box-elder, and the Buddha who had

entirely drowned in snow is dancing in front of the trailer once again.

Crocuses by next week, perhaps?

We moved the chickens to the uphill coop when the flood waters began to lap at the toes of their former home.

We moved the chickens to the uphill coop when the flood waters began to lap at the toes of their former home.

I tried to retrieve our closer sap bucket, but had to let it go.

Red-winged blackbirds moved into the newly created swamp, and the ducks roamed far and wide.

Maybe we'll be able to cross the creek sometime next week?

I've been spending a lot

of time with our goats as I obsessively monitor Abigail's slow slide

toward delivery. The actual specifics of when ligaments disappeared,

when udder bulked up partway and then became further engorged, and so

forth are going down on paper to make our doe's next pregnancy less

nerve-wracking for the human observers. But today I can't resist sharing

some of the thoughts I've had on goat language in the interim.

The way goats communicate is so simple that I can't quite figure out why Lucy doesn't get it. Here's a typical exchange:

Artemesia: Let's play! (Slightly lowers her head, then raises one front hoof, waving it about in the air.)

Lucy: *Sigh*. No one wants to play with me. (Wanders off.)

Artemesia: *Sigh*. No one wants to play with me. (Wanders off.)

Or:

Abigail: If you know what's good for you, you'll back away slowly, right now. (Head lowered with horns directly facing forward.)

Lucy: Oh, goody, you want to play! (Bounds forward.)

Lucy: WTF?! (Growls.)

Anna: Lucy! Bad dog!

Lucy: Oh, now I get it. Abigail is a cat.

Sometimes, I'm glad to be a human who speaks English, dog, goat, and cat. Does that make me multilingual?

He showed up around 10 this

morning.

There were no problems during

the delivery.

Abigail and Anna are recuperating nicely.

It seemed like every day this week, I woke up absolutely certain that Abigail would have kidded.

Without taking the time to make my own breakfast, I'd chop carrots and

then head up the hill to check on our doe...who kept showing signs of

kidding but never quite managed to pop out a kid.

So, on Friday, I decided

to go a bit slower. Even though Artemesia was standing at the gate and

hollering, I figured our half-Nubian doeling was maybe just in heat and

feeling chatty. I performed my morning ablutions, then wandered up the

hill to check on the goats about 8:30 a.m.

Nothing. Abigail's udder

had expanded again during the night, but her vulva looked about the same

--- no sign of mucus. Yes, the doe's ligaments had been absent for 44

hours at that point...but maybe Abigail hadn't read the same websites I

had?

For the last few days,

I'd had Abigail on a two-hour watch during daylight hours. This was more

for my sake than hers --- knowing that I'd wander up to the barn at a

set time prevented me from simply moving in with our goats. But at 10

a.m., I hit a natural stopping point in my writing, went out to carry in

some firewood, then decided to go up the hill just a little early....

...But

not early enough! I'd missed the main event and was greeted by a

healthy white buckling, standing on his wobbly feet as his mother

vigorously worked on licking him dry.

...But

not early enough! I'd missed the main event and was greeted by a

healthy white buckling, standing on his wobbly feet as his mother

vigorously worked on licking him dry.

I rushed back home to

alert Mark and to collect my kidding basket, then went inside the goat

barn to see if Abigail needed any help. The kid seemed extremely

vigorous, but he was also very wet and the temperature outside was about

15 degrees Fahrenheit with no sun yet having popped over the hill. Ice

was forming on top of the kid's head and on his ears, so I got to work

with a towel while Abigail continued to lick (and even bite) at the ice.

I had expected Abigail

not to want me to handle her baby, but she didn't mind me lifting him up

and setting him on my lap. According to my notes, if there was another

kid she should push that one out within about twenty minutes, so I

wasn't terribly concerned at first when Abigail didn't want to let her

current kid drink. Instead, every time he headed for a nipple, she

sidled away.

(Side note: If you're eating your breakfast as you read...maybe wait to finish this post later. Placenta pictures follow.)

This process continued

for a while, until I tucked the kid into the front of my coat and sat

down to give Abigail a little peace and quiet. She promptly lay down,

and when I let the kid out, he settled down by her head.

Nothing happened, though,

except that Abigail started to shiver, and I started to worry. The

books said another kid should come within twenty minutes and that the

first kid should also nurse within its first half hour of life, and both

deadlines had already passed. So I went back to the house to collect a

cool-minded husband and a warm bowl of molasses water.

Abigail sucked down the

entire bowl of molasses water in short order, and then she seemed ready

to push out whatever was on its way. At first, I wasn't sure if it was a

kid that needed help, but soon became confident that the mass of gunky

goo was the placenta, meaning that Abigail had carried only a singleton

this time around.

Some goat owners are disappointed by singletons (since twins are the

average), but Mark and I were actually both glad to have only a single

kid to handle. The buckling can be Artemesia's paramour this fall, then

will go in the freezer (so no name). In the interim, a single kid will

drink less of the milk that I want for myself. Yes, I know I sound a bit

hard-nosed here, but that's what growing your own food is all about.

Anyway, back to the

kidding drama.... Once the placenta plopped to the ground, Abigail

turned around and promptly began to chow down. Some goat keepers don't

let their does eat the placenta, and the process did

look a little gross. But I felt like Abigail might need the dose of

nutrients, and her intentness on the placenta also gave me a chance to

help the buckling finally find a nipple. I squeezed out a little

colostrum to make sure Abigail had let down her milk, then worked with

the kid until he figured out that the teat went in his mouth. Soon, he was happily suckling and his fur was quite dry, so I finally felt comfortable leaving the pair alone.

Next up --- I need to

decide whether to milk out a bit of colostrum to put in the freezer as a

backup, and then (in a few days) it will be time to learn to milk for

the human table. With only a single kid, we should be able to start

drinking homegrown dairy pretty soon --- I can hardly wait!

Abigail is clearly bonded

with her new baby except for the fact that she can't seem to teach the

new guy how to nurse.

We start out with me holding

the back leg down for the first few kicks, and then she loses interest

in kicking once the milking begins.

I think once he figures out

how to control his legs better then he'll learn how to attain the

proper nipple angle.

I've never grown borage

before, but I should have guessed from the larger seed size that the

plant wasn't one of those slow-growing herbs. While thyme, oregano, and chamomile

planted in the middle of February are still so tiny that you can hardly

imagine them growing out of their starter cells, the borage planted ten

days later seemed to be too big for its home as soon as the cotyledons

emerged. Time to pot up!

I like to keep the

nutrient levels very low in my seed-starting trays to get the babies to

work on roots while also minimizing problematic soil fungi. But bigger

pots means it's time to mix in well-rotted horse manure along with the stump dirt

or potting soil, at a ratio of one to one. A friend of Mark's

introduced the idea of potting up into plastic cups with holes drilled

in the bottom, which is a great innovation since the pots are cheap and

you're able to keep an eye on root growth. I have a feeling our borage

will require yet one more round of potting up before we're allowed to

set them out in the middle of May, and the clear pots will help me

ensure they don't grow root bound in the interim.

Technical

note: Some of you probably noticed we were unable to make new posts for

the last 24 hours. I'm afraid that comments you made during that time

period may have been lost --- sorry! I think I got to read them all, at

least, although I'm especially sorry that Brandy's comment about

placenta can't be shared with the world....

Are

you thinking of adding chickens to your homestead this spring? Or

perhaps you want to expand your flock and make sure their run doesn't

turn into a muddy mess? I have two books that should hit the spot, one

free and one on sale today!

Are

you thinking of adding chickens to your homestead this spring? Or

perhaps you want to expand your flock and make sure their run doesn't

turn into a muddy mess? I have two books that should hit the spot, one

free and one on sale today!

Pasture Basics

is the freebie, full of everything I've learned about rotational

chicken pasturing over the last few years. Then, if you like what you

read in book one, you'll want to be sure to pick up Thrifty Chicken Breeds

while it's marked down to 99 cents since this companion book will help

you choose the right type of chicken to put on your new pasture.

And, to make this a true chicken-giveaway week, one lucky reader will walk away with a free premade EZ Miser,

our favorite type of waterer for pastured poultry. Just share why you

want an EZ Miser (or why you love the Avian Aqua Miser or EZ Miser

you've already got) on facebook, twitter, or google plus, click on the

giveaway widget below, and you'll be entered to win!

Our creek went down enough to

get across on the

log.

It felt a little dicey

walking on it with a full back pack, so we decided to use the kayak to

ferry our groceries and chicken feed.

We'll be ready for the next

100 year flood by having one of the kayaks in the barn on this side of

the creek.

I should have known that Abigail's kidding experience

was too simple. The birth itself went fine and our doe clearly bonded

with her kid...but she really, really didn't want to let him nurse. On

the first day, once the placenta was gone and life in the coop had

returned to normal, I kept checking in and seeing the kid head for the

udder...then Abigail would run in the other direction. A search of the

internet suggested that this behavior is distressingly common, and that

the solution is either to bottle raise the kid (not our goal) or to

stick mom in the milking stanchion in order to give the kid an

opportunity to drink.

When the kid was six

hours old, I decided to try the stanchion trick. The result? Complete

and utter chaos. I tried to leave Artemesia in the coop and to carry the

kid while walking Abigail to the porch, but our doe seemed more

concerned about leaving her herd mate than she was about the location of

her kid. After much screaming (Abigail and Artemesia --- I refrained,

despite my frustration), we went back to collect the doeling and all

four of us (plus Lucy) ended up on the porch.

Lucy was intrigued by the

new creature in my arms, Artemesia figured out that by jumping up on

top of the picnic table she could stick her nose in the bag of alfalfa

pellets, and Abigail realized that she could yank her neck right out of

the stanchion. Nearly in tears, I ran to get backup.

"You

should have called me sooner," said Mark, taking in the drama unfolding

in front of him. He tied up Lucy and Artemesia, then grabbed Abigail's hind leg

while I pinned our doe against the wall. That left each human with one

free hand, which we used to push the befuddled kid up against the

nipple. And, to everyone's relief, he drank...and drank...and drank.

"You

should have called me sooner," said Mark, taking in the drama unfolding

in front of him. He tied up Lucy and Artemesia, then grabbed Abigail's hind leg

while I pinned our doe against the wall. That left each human with one

free hand, which we used to push the befuddled kid up against the

nipple. And, to everyone's relief, he drank...and drank...and drank.

Mark and I considered a

second feeding that day, but it gets dark so early at this time of year,

and I wasn't sure that Abigail would have produced any new milk in two

hours. So we left her until morning, at which point I made the same

mistake all over again. I was worried and went up to check on the goats

at 7:30 while Mark was still asleep, and seeing the kid shivering in

14-degree weather, I figured that surely

I could repeat the feeding on my own this time around. To cut a long

story short, chaos reigned again, this time with Abigail discovering a

new trick --- lying down in the milking stanchion, never mind that the

kid's head was underneath her belly. But I was finally able to tie up

the two troublemakers (Lucy and Artemesia), to heft Abigail's belly up

in one arm, and to stick the kid onto a nipple with the other.

Meanwhile, I decided that

with only one kid, Abigail's udder wasn't getting all the way cleared

out, which probably kept the flesh perennially tender, so I pulled out our milking machine

and set it to sucking colostrum out of the other teat. I have to say

--- that milking machine is a life saver. I was able to hold Abigail up,

keep the kid's mouth on the nipple (he isn't too bright), and milk the

second teat all with my two hands. When Mark showed up, everything was

under control (even though, once again, he was right --- I should have

called him sooner).

Since then, Abigail still hasn't let the kid drink on his own, but things have

gotten much smoother. After his fourth real feeding, the kid finally

started jumping around and acting like a baby goat should, which was a

huge relief. Meanwhile, Abigail still requires an admonishing hold

around her hind leg at first, but she soon settles into the stanchion

(which we've relocated to the kidding stall to make crowd control

simpler). Even Artemesia has figured out her role --- cleaning up any

tidbits Abigail leaves behind once the milking is done.

For the next few days, we'll stick to thrice-daily feedings, but by the

end of the week I hope to attain a morning and evening schedule as if we

were milking. And maybe by then Abigail will be making enough milk to

share with us as well as her kid.

Soaking our mini

mushroom logs in a pan of

water every other week seems to be enough to keep them moist.

We also wrap each one in a

grocery bag to hold in moisture.

Guess whose belly was

full and whose udder was empty when I showed up with milking gear in

hand Tuesday morning? I guess Abigail's finally going to let me off nursing duty so I can start enjoying this speedy transition from January-in-February to April-in-March.

Yes, the first speedwell

and bittercress are starting to bloom, the frogs are starting to call,

and it's time to get serious about the gallons of sap coming out of the one tree we've tapped on this side of the still-flooded creek!

My movie-star neighbor

had big plans about expanding his sugar mapling operation this year,

and I have to admit his enthusiasm was contagious. After all, tapping

maples seems to be much simpler and more dependable than getting honey

from chemical-free bees.

The kink in the maple syrupping plan, though, is boiling down all that

sap. The weather is already getting too warm to drive off the moisture

from a single tree's sap on our wood stove, and using the electric stove

seems very inefficient. But what about the rocket stove?

I filled a big pot with

box-elder sap on Monday night and decided to give the system a test run.

The good news is, one hour of rocket-stove use only consumed about half

again as much wood as is pictured above. The bad news is, the flames

only drove off about a cup or so of water, the sap ended up getting a

bit ashy, and I learned that you really do have to tweak the fuel in a rocket stove every five minutes or it'll burn down to coals.

So, no rocket-stove maple

syrup for us. I guess we'll stick to syruping on a small scale until a

better way to boil down the sap appears out of the ether. Maybe we need

to make a self-feeding rocket-stove-fuel hopper?

Abigail figured out how to

buck the milking

stanchion in just the

right way to unlock the screen door latch that was holding it.

I'm pretty sure she can't get

out of the above latch, but if she does we might change her name to

Houdini.

It's almost physically

painful to be forced to stay out of the garden when the weather has

suddenly changed over spring after weeks of anticipation. Unfortunately,

I made the mistake of going in to the doctor's office for a

regular checkup (which I'd been putting off for 7 years) and came home

with a clean bill of health...and a virus. So Mark has ordered bed rest

and I'm doing my best to comply.

My long-suffering husband

did let me up long enough to get the first garden seeds in the ground

at last, a quick project since Kayla and I had already prepared the beds

weeks ago, hoping that the abnormally cold weather would someday break.

Lettuce, arugula, and peas should enjoy this current mild, wet

spell...and planting a month late probably won't make very much

difference in the eventual harvest time. That's the great thing about

spring --- every day gets warmer and sunnier and plants quickly make up

for any lost time.

So, if you're enjoying the warm spell we are --- by all means plant!

Just have some quick hoops waiting in the wings for when the lion

returns for one last roar before true spring.

A stainless steel wine bucket

makes a nice milking

machine jar holder.

It was easy to mount with a

short section of pipe

strapping.

Five months of

goatkeeping has been such a joy that I almost forgot the whole point ---

milk! But Abigail's production has been increasing quickly, and even

though the kid is still drinking as much as he wants, our doe shared a pint yesterday with her human caretakers. Time to

figure out the dairying side of goatkeeping. As usual in the caprine

world, I've got more questions than answers at the moment, so I hope

you'll chime in with your wisdom.

To wash or not to wash?

The udder that is. Older advice was to wash and dry the udder before

milking, but newer sources suggest that you might actually move more

bacteria toward the milk that way than you remove. Unless there's actual

dirt on the teat, many modern experts simply recommend dipping the teat

in a disinfectant instead of washing. Others say you shouldn't dip the

teat until after milking, and that the dip's purpose is to prevent bacteria from getting up inside the teat and causing mastitis. What do you

do? What kind of teat dip do you use (if any) and when? And won't the

chemicals from the dip end up in the milk if you use it before milking?

To wash or not to wash?

The udder that is. Older advice was to wash and dry the udder before

milking, but newer sources suggest that you might actually move more

bacteria toward the milk that way than you remove. Unless there's actual

dirt on the teat, many modern experts simply recommend dipping the teat

in a disinfectant instead of washing. Others say you shouldn't dip the

teat until after milking, and that the dip's purpose is to prevent bacteria from getting up inside the teat and causing mastitis. What do you

do? What kind of teat dip do you use (if any) and when? And won't the

chemicals from the dip end up in the milk if you use it before milking?

What to do with all that milk?

Wow, even a pint a day seems like a lot of milk and production is

likely to continue to rise for the next few weeks. I want to start

experimenting with cheesemaking, but most cheeses seem to require

cultures (except for the lemon juice method that most people say isn't

very good). Do you have a culture source you particularly recommend? A

way to grow your own cultures so you don't have to keep buying them?

Which cheese recipes have worked well for you with goat's milk? And what

cheese-making recipes do you recommend? Finally, if that kind reader

who once offered us a buttermilk culture is still around, I'd love to

take you up on that kind gift now!

A strip of shelf

liner makes it a little easier for our baby goat to get a sure

footing when trying to nurse on the milking stanchion.

Of course he figured out how

to get a drink from Abigail the next day.

At least it will be there if

we need it for the next baby goat.

In one of his books, Paul Stamets

explains that it's essential to keep the mycelium (vegetative stage of a

fungus) running. In other words, don't let your cultures sit and

stagnate --- they need to grow!

While true for fungi,

Stamets' admonition is even more true for spring seedlings. My goal is

always to keep our seedlings running...or at least moving along at a

steady jog.

Potting up is one sure method of keeping little seedling roots and shoots

growing fast. But when I moved herbs out of their starting flat at the

beginning of March, I left about half the seedlings behind, figuring

that ultra-slow-growers like thyme and oregano probably wouldn't notice

the difference. Plus, I just didn't have enough window space for twice

that many new pots.

For

the first day or two, the left-behind seedlings grew faster than the

potted up seedlings --- such is the way of transplant stress. But a week

after that, the difference was striking. The seedlings that I'd allowed

to spread out into bigger pots had suddenly acquired twice as much leaf

area...a fact that was true even for the minuscule oregano and thyme

that barely seemed to be making a dent in their living accommodations in

the flat.

For

the first day or two, the left-behind seedlings grew faster than the

potted up seedlings --- such is the way of transplant stress. But a week

after that, the difference was striking. The seedlings that I'd allowed

to spread out into bigger pots had suddenly acquired twice as much leaf

area...a fact that was true even for the minuscule oregano and thyme

that barely seemed to be making a dent in their living accommodations in

the flat.

Unfortunately, I couldn't

repot all of the herbs because I just didn't have enough room indoors.

But since those extra seedlings were just that --- extras --- I decided

to give them a bigger and more dangerous place to run. The ultra-sunny

flowerbed in front of the trailer just might be warm enough to let these

seedlings survive spring freezes. If the next burst of cold holds off

long enough for their tender roots to get established, I'll bet the

herbs get their feet under them and outgrow the indoors seedlings by the

end of the month. The race is on!

Up next: tomato seedlings

with their second sets of true leaves need more root space ASAP. Next

week, Mark and I might make a little cold frame around the front of the

trailer to house the broccoli, cabbage, and onion seedlings so there

will be more room indoors for big tomato pots. In the meantime, the

babies get a hearty dose of manure tea to provide a quick fix of nitrogen for faster growth. Gotta keep those seedlings running!

Our swamp

bridge floated downstream during the recent flood.

The last time it floated it

only went 10 feet and I thought the anchoring

job we did after that

would have kept it in place.

Maybe there's a better way to

anchor it I'm not thinking of?

I started getting sick the night before our baby goat was born, so I missed a lot of photo and cuddling opportunities. Luckily, just holding Lambchop up to his mother's teats for the first  four

days ensured that the kid thinks I'm some kind of mother figure. So I

apparently don't have to worry about him being unsocialized.

four

days ensured that the kid thinks I'm some kind of mother figure. So I

apparently don't have to worry about him being unsocialized.

In fact, when I went out

into the pasture with Lambchop and Artemesia to give our doeling some

much overdue TLC, the kid hopped right up into my lap for extra

petting...then jumped down...then jumped back up...then jumped down. I

guess I don't need to worry about his early nursing issues impacting his

vitality either.

Abigail figures that

producing milk is a full time job. While I rollicked with the younger

goats, our doe stood in the doorway of the coop and chewed her cud. Then

she took a break to head to the manger for some hay, called Lambchop

over to relieve a bit of pressure on her udder, then got back to the

all-important work of cud-chewing. She feels no need to rub up against the human.

Artemesia, on the other

hand, has been a bit attention starved ever since she stopped being the

cutest animal on our farm. She's done a good job of turning into a

gentle auntie for Lambchop, bouncing around with the kid while Abigail

stands sentry in the doorway. But Abigail has continued to act crankily

toward her coop-mate, and Artemesia was quick to lean her shoulder

against mine and settle down to soak up a little bit of love when it was

offered.

It's

a fine line between socializing a buckling to the point where he'll be

easy to handle...and falling in love with him. But I hope that Mark's

witty name for our kid will remind us that Lambchop is bound for the

freezer.

It's

a fine line between socializing a buckling to the point where he'll be

easy to handle...and falling in love with him. But I hope that Mark's

witty name for our kid will remind us that Lambchop is bound for the

freezer.

The moniker also reminds me that I left out the biggest reason new homesteaders shouldn't get goats in my previous post

--- it's tough not to fall for the bucklings. But the world only needs

so many wethered pets, so Lambchop and I will become friends but not

confidantes. I'll save my secrets for Artemesia.

The earliest we've seen a crocus since we've been here was back in 2013 when they showed up at the end of January.

I've been pondering a shade house

somewhere on the north side of the trailer for years. The idea is to

have a cool spot for summer dining, mushroom growing, and seed starting

during the hot season while still allowing rain to fall through the

"roof."

I've been pondering a shade house

somewhere on the north side of the trailer for years. The idea is to

have a cool spot for summer dining, mushroom growing, and seed starting

during the hot season while still allowing rain to fall through the

"roof."

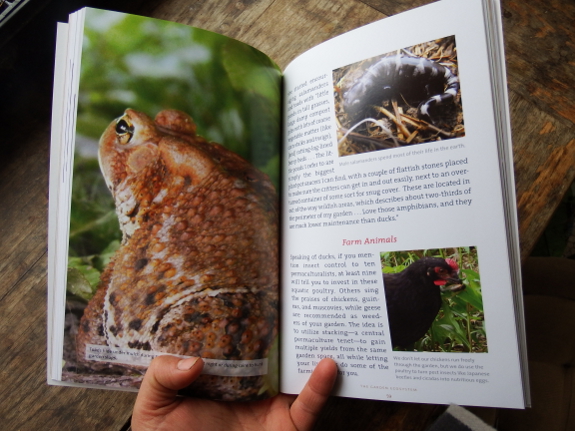

But the idea has never quite gelled into a finished form because I'm not quite sure what I want to make the structure out of. So when I stumbled across the photo to the left from Pooktre Tree Shapers, a light bulb went off in my mind. Maybe I need to build my shade house out of...trees!

Building with living

trees has a long history which may have begun with living root bridges

in India. However, those of us lacking a tropical climate can't get away

with using aerial roots for construction. Instead, we have to focus on

temperate-zone trees that grow quickly and (hopefully) have the ability

to easily graft together (inosculate) when nearby branches touch. Plants

that commonly inosculate and might be used for tree sculptures include

apple, almond, ash, beech, crepe myrtle, chestnut, dogwood, elm, fig,

grape, hazelnut, hornbeam, linden (aka basswood), maple, olive, peach,

pear, privet, river red gum, sycamore, willow, and wisteria.

Of these, willow is probably the easiest to use since you can root a

willow cutting simply by sticking the twig in the ground. Plus, the

resulting growth from the willow is malleable and extremely vigorous,

making it easy to shape and quick to grow. Finally, in our wet soil,

willows are bound to thrive, although I should mention those of you

gardening in drier climes might focus instead on elm or plum. (As a side

note, using fruit trees to make structures is enticing, but the

maturation process will be slower and you'll struggle to mesh your

sculptural needs with the plant's fruiting needs. In other words, this

is one instance where I'd probably recommend against going for an

edible-landscape selection.)

What have people built

from living willow trees? Chairs like the one shown at the top of this

post (although that tree is likely a plum), stairs, shade arbors,

arches, pergolas, and the newly named "fedge" (a fence that's also a

hedge because it's alive). I highly recommend this site (which is where I found the photo above) if you're looking for large-scale ideas, or check out this site for an inspiring array of willow fedges.

Now, before you get too

excited, I should tell you that creating structures out of living trees

is a long-term project that can take as much as a decade to fully

mature, so you'll want to think through your plan up front and make sure

you're willing to wait for the finished product. In addition, during

the early years, you're committing to a summer pruning and training campaign much like the one you'd use on a high-density apple orchard.

In general, you'll want to train the young growth into its final shape

as it appears, then rub off new branches that pop up in the wrong spot

during the summer months. After the sculpture matures, you'll still need

to prune perhaps twice a year (which can provide a handy source of goat

fodder or mulch for your garden).

I'm pondering starting

out with a simple arch over our current mushroom station. A lattice of

willows at the back could arch across and merge with two larger trees in

the front to make a shady bower. Now I just need to determine whether

our wild black willows (Salix nigra)

are a good choice for tree sculptures, or whether I should splurge and

buy one of the willow hybrids that are reputed to grow up to 15 feet the

first year. Decisions, decisions....

How long does it take to

drill and plug our mushroom

logs?

We managed 2.5 an hour this

morning with me doing the drilling and Anna marking, hammering and

sealing each plug with bees wax.

I've used both quick hoops and cold frames in the past, and usually prefer the latter. However, now that we've finally skirted around the front of the trailer,

I couldn't help thinking that the sheltered, warm spot would be perfect

for a glass-covered cold frame to house flats of cabbage, broccoli, and

onion seedlings while they wait for safe outdoor-planting time. The

area is close enough to the front door that I won't mind opening and

closing the lid daily during sunny spells, and it'll also be pretty

simple to carry the flats inside if we hit a really cold spell. So when

Mark found two large, double-glazed windows in the barn, I figured the

cold frame was fated to be!

The first step of

building our new cold frame was checking to make sure we'd still be able

to get up on the roof to clean out our chimney. Now that I have a

grapevine on the right side of the wood-stove alcove and a cold frame on

the left, Mark will have to go up the front. Luckily, he says the

ascent is feasible...as long as I hold the ladder.

This area is a relatively

easy spot for cold-frame construction since two sides of the cold frame

can simply butt up against the existing building. Mark attached a

two-by-four along the trailer to support the windows...

...Then hinged the first window into place. (Thanks for the hinges, Rose Nell!)

After adding the second

window, we realized that the two windows bumped against each other when

closed all the way. Although we could have tweaked the hinge arrangement

slightly to prevent this issue, Mark instead used metal brackets to

attach the two windows together into one solid piece. In addition to

fixing our slight mismeasurement, that arrangement also made it easy to

hold both windows open with a single screen-door hook on the side of the

trailer.

Next, we used a

two-by-six to form the front wall of the cold frame. Slanting the glass

from an 18-inch-high back to a 5.5-inch-high front should help the cold

frame collect more winter sun. But the angle did

make it tough to determine the location of the two-by-four support on

the right side. "Oh, that's easy," Mark said. He lifted up the window

glass and motioned me inside to mark and hold the support board.

The left side of the cold

frame involved building a triangle out of wood, which we opted to do

the easy way. We used the end of the two-by-six that had formed the

front of the cold frame to butt up against the window on the top, then

cut segments of an old door (thanks, Sheila!) to fill in the gap left

behind.

We've still got a little

work to do filling in gaps and painting the untreated wood, but the cold

frame is nearly ready to go after just a couple of hours' work. I've

got a max-min thermometer

in there now to test the waters and can hardly wait until we reclaim a

bit of our kitchen table from the cold-hardy seedlings. Right now,

there's barely enough room to fit two plates into the section the plants

left behind....

It was 5 degrees warmer

inside our new cold frame than the outside temp.

Adding some silicone and

spray foam sealant today should help to keep it even warmer tonight.

I

have a love-hate relationship with books from Chelsea Green. Their

titles are so enticing...but the price tags are daunting and about half

of the books ultimately disappoint once I crack them open. Farming the Woods

by Ken Mudge and Steve Gabriel was partially inspiring and partially

disappointing, with a dry and academic tone and far too much basic

information, but with beautiful pictures and hands-on information that

made reading worthwhile.

I

have a love-hate relationship with books from Chelsea Green. Their

titles are so enticing...but the price tags are daunting and about half

of the books ultimately disappoint once I crack them open. Farming the Woods

by Ken Mudge and Steve Gabriel was partially inspiring and partially

disappointing, with a dry and academic tone and far too much basic

information, but with beautiful pictures and hands-on information that

made reading worthwhile.

The most helpful part of the book was the authors' realistic notations on which plants will really

produce in the shade. Despite forest-gardening literature to the

contrary, Mudge and Gabriel report that in a woodland setting with more

than 40% canopy cover, the only species that reliably bear fruit are

pawpaws, elderberries, ramps, and mushrooms. At 25 to 40% shade,

shisandra, hawthorn, currant, gooseberry, honeyberry, hazelnut,

juneberry, and groundnut join the mix, although productivity is likely

to be significantly lower than yields in full-sun environments. For

example, hazelnuts produce about 70% of their optimal yield in 30% shade

and 30% of their optimal yield in 90% shade, so you have to decide at

which point the juice is no longer worth the squeeze.

Another useful facet of Farming the Woods

was the authors' analysis of which non-timber forest products make

economic sense. After all, for forest farming to be more than a hobby,

landowners need to be given an incentive to keep those trees standing

rather than selling them to the local sawmill. Although many non-timber

options were presented, the authors felt that the most economically

feasible include tapping sugar maples (and possibly birch) for syrup,

growing ginseng for roots, and raising shiitakes on logs. In addition,

chestnuts and hazelnuts can provide relatively lucrative nut crops, and

turning the forest into a nursery for shade-loving ornamentals can also

help pay the bills.

In the end, Farming the Woods

isn't the must-read permaculture book of the year that I thought it

would be, but it's definitely worth at least checking out of your local

library. Or maybe you'd like to be the lucky recipient of my lightly

read copy? Enter the giveaway below and you may get a copy of your very

own for free!

We finished up the new cold

frame today.

Two coats of paint and some

caulk where we connected the two windows should help it to go well into

the future.

Our Meadow Creature broadfork

came in the mail a week and a half ago, but between the flood and my

cold, I only got to play with it for the first time Wednesday. My first

impression? This tool is fun! I'm slowly running out of terraforming opportunities to keep myself happy during the winter, so adding the broadfork to the mix will be as good as an antidepressant.

More seriously, in soft

garden soil, the broadfork works almost too well. Mark had to rein me

in, reminding me that our goal is merely a light loosening rather than

to really till up the soil. I eventually decided that a gentle fluff

from the edge of the bed is a good compromise in this kind of situation,

which will hopefully add a bit of aeration without negatively impacting

soil life. I plan to run a side-by-side comparison this spring, but

suspect that beds loosened lightly with the broadfork will be especially

good for root crops like carrots.

I also wanted to see how

well the broadfork performs in hard ground, so I headed up to the

extremely poor soil of the starplate pastures for test run number two.

Here, it took more effort to sink the tines into the earth and I had to

put my back into it to loosen once the tines were engaged. This area

will definitely be a good spot to work up a sweat next winter, and the

soil will probably benefit much more from broadfork action up here than

down in the main garden, but I'll admit this area felt more like work

than like play.

So did I select the right size?

I went for the smallest model, and that is definitely all I could

handle in the starplate pasture. I suspect I could have worked with the

next size up if I'd stuck to the main garden, but I'm not so sure the

extra two inches of loosening depth are really mandatory. So, yes, I

think Mark's nudge toward the smallest size was a good choice, and for

most female gardeners I would recommend the same. If you're particularly

tall or brawny, though, feel free to choose the 14 inch!

We're trying a new syrup

experiment on a nearby black birch.

Our newspaper bokashi experiment is now underway. Here's our current method:

- Make a lactobacillus starter using yogurt, molasses, and newspaper. Wait at least two weeks. (We waited nearly three.)

- Use a gamma-seal lid and a five-gallon bucket to make an airtight container.

- Fill the bottom of the container with about four inches of dry sawdust to soak up any liquid that forms. Alternatives to this step include adding a spout to the bottom of the bucket so you can decant the leachate, drilling holes in the bottom of the bucket and setting it inside another bucket for the same purpose, or using newspaper or cardboard to soak up the leachate.

- Place a layer of the newspaper starter on top of the sawdust.

Instructions say that one sheet here is fine, but I had plenty of

newspaper and didn't want to try to tease apart wet pages so I included a

whole newspaper section. (More starter never hurts --- it just helps

the bacteria work faster.)

- Pour in food scraps. These should be no more than two days old and shouldn't include moldy or spoiled food, but you can include meat and dairy. As you can see, at this time of year, our scraps consist of eggshells, orange peels, a bit of discarded dandelion roots, and onion peels.

- Add another layer of newspaper starter to completely cover the food scraps.

- Put a plastic grocery bag on top of the newspaper and use your fists to pound everything down. The goal is to remove as many air pockets as possible and to bring the newspaper starter in close contact with the food scraps.

- Leave the grocery bag in place, screw on the lid, and set aside for two days until more food scraps accumulate. At that point, you repeat the food-scraps layer, the newspaper layer, and the pounding, then continue with bi-daily additions until the bucket is full.

- Let the bucket ferment at room temperature for two to four weeks

after filling, then apply to the soil. (More on this step in a later

post.)

I'll admit up front that I'm a bit dubious of the efficacy of bokashi, even more so after I read the "science" chapter in Bokashi Composting

by Adam Footer. So I'm running a three-part mini-experiment to give

myself a rough idea about whether the more complicated bokashi method is

worth the time and expense.

The control is shown

above. I filled a normal five-gallon bucket (no air-tight lid) with food

scraps, let them sit on the porch for a month or so, then applied them

in a trench in the starplate pasture. I marked the location of the

control and will be adding similar trenches full of bokashi made using

two methods (store-bought starter and homemade starter) in the months to

come. Finally, I'll dig into each area a month or so after application

to determine whether the bokashi method really did make the scraps

decompose faster and whether the soil seems to be better in the bokashi

zones than in the control zone. Stay tuned!

I wanted to share this nice T-shirt design one

of our readers made.

It's only available for the

next 14 days, and she needs at least 3 orders to get the printing

process rolling.

Sarah is available for custom

shirt designs and can be contacted through her ThreadBearDesign

Facebook page.

Usually,

spring comes to our farm long before the equinox. But the natural world

is running a little late this year. Can you believe it's officially

spring and the first daffodil is still struggling to open its bloom?

Usually,

spring comes to our farm long before the equinox. But the natural world

is running a little late this year. Can you believe it's officially

spring and the first daffodil is still struggling to open its bloom?

On the other hands, the frogs are calling like crazy, the first hepatica

was spotted in the woods Wednesday, and Mark and I each heard a grouse

beating on a hollow log calling for a mate. Perhaps we can finally write

off Old Man Winter after all.

In the garden, I'm a bit

behind in chores and the plants are a bit behind in emergence. I went

into the winter a little remiss because sprouting-straw

issues meant that half of my garlic never got mulched in the first

place, and snow cover in February and early March meant that I wasn't

able to reach the ground to rip out the chickweed that had taken over

that open ground. Luckily, a warm week and a lot of rain washed away the

snow and I was able to get peas and lettuce in the ground

by the middle of the month. Now I'm hard at work weeding and prepping

beds for carrots, parsley, mangels, and cabbage transplants, while

slipping in a bit of time to weed our garlic and strawberry beds.

I'm also behind on pruning, but purposely so since I was afraid that early pruning during a particularly cold winter would exacerbate freeze damage. The good news is that my gut feeling was right --- early pruning combined with cold weather is what killed back our red raspberry canes last year. This year, an even colder winter (low of -22  Fahrenheit) didn't nip the brambles, so we'll get our usual spring and fall crops --- success!

Fahrenheit) didn't nip the brambles, so we'll get our usual spring and fall crops --- success!

On the other hand, the

first elderberry leaves are now starting to pop out, so tree flowers

can't be too far behind. That means I need to hurry up and prune like

crazy to make up for lost time, a good project for wet days like this

when the garden is too sodden to make weeding a pleasure.

Even though the raspberries fared well during our winter cold, I still

plan to test some bloom buds on each new species before I prune. After

all, if the winter nipped some percentage of the peach bloom buds, for

example, I'll want to leave more behind to take their place.

Even though our vegetable

garden is running behind, wild food is already becoming available.

Creasies keep springing up in our garden despite the fact that I'm

pretty sure I haven't let any go to seed since moving here, and

dandelions always find new ground to sink their deep taproots into. I

pulled a large bowlful of these two delicious greens out of the garden

while weeding Wednesday, then washed them in several changes of water

and sauted with balsamic vinegar and peanut oil. A delicious dose of

spring!

Our little Lamb Chop is at the point where he likes to jump up into a warm lap every chance he gets.

Baby

goats grow almost unbelievably quickly. The kids can stand up within

minutes of birth, they seem to double in size at a remarkable rate, and

at two weeks old they are mature enough to be separated from Mom

overnight.

Baby

goats grow almost unbelievably quickly. The kids can stand up within

minutes of birth, they seem to double in size at a remarkable rate, and

at two weeks old they are mature enough to be separated from Mom

overnight.

Friday was Lamb Chop's

big night. After milking Abigail nearly at dark, I stuck our little kid

in the milking stall all by himself and walked away. He cried and

Abigail cried, but they both fared fine overnight, and the next morning I

was able to collect a larger share of the milk (11.8 ounces). As Lamb

Chop learns to eat solid food over the next few weeks, I'm hoping the

human milk quota will continue to grow.

My original milking plan involved separating the kid(s) at night

and then just milking once in the morning, but Abigail's early nursing

issues set me off on a

different track. Even after Lamb Chop found his

way to the teat on day four, I kept milking twice a day anyway, only

getting dribs and drabs (seldom more than cup and often much less). The

small amount of milk

was appreciated, but I felt like the milking was particularly important because Lamb Chop seems to prefer Abigail's right side, a common issue

with single kids. By milking our

doe out twice a day, I'm able to ensure that both sides of Abigail's

udder

keep producing milk. Meanwhile, Lamb Chop was getting all he could drink

until the nighttime separation, so I didn't have to worry that he was

lacking in nutrients. In fact, he seems to have doubled in size over the

last week.

My original milking plan involved separating the kid(s) at night

and then just milking once in the morning, but Abigail's early nursing

issues set me off on a

different track. Even after Lamb Chop found his

way to the teat on day four, I kept milking twice a day anyway, only

getting dribs and drabs (seldom more than cup and often much less). The

small amount of milk

was appreciated, but I felt like the milking was particularly important because Lamb Chop seems to prefer Abigail's right side, a common issue

with single kids. By milking our

doe out twice a day, I'm able to ensure that both sides of Abigail's

udder

keep producing milk. Meanwhile, Lamb Chop was getting all he could drink

until the nighttime separation, so I didn't have to worry that he was

lacking in nutrients. In fact, he seems to have doubled in size over the

last week.

Speaking of lacking in

nutrients, Abigail has recently started peeling bark off the little

saplings in her yard. I suspect she's getting desperate for fresh

growth, and I have high hopes that we can set up some temporary

enclosures in the most sunny part of the yard in a week or two to let

our goats enjoy the first spring grass. I learned this fall that even

though goats aren't supposed to be grazers, our girls are quite happy to

eat tender leaves growing out of the ground and I can hardly wait for

our girls to be off the hay train.

In

other news, Artemesia seems to be losing her youthful bounce at the

same time that Lamb Chop learns to caper --- I guess there can only be

one baby in the family at any given time. As you can see in the photo

above, I upgraded our doeling to a real collar and gave the mini collar

to Lamb Chop. I think our buckling is confident enough in his

masculinity that he won't mind wearing pink. In fact, he'll be old

enough to possibly become a father in just another ten weeks --- then

we'll have to figure out whether Artemesia is willing to go into heat in

the summer for a fall kidding or whether we'll need to separate Lamb

Chop for the summer so he doesn't knock his mother up. Goat management

definitely leaves us with a continuing set of hurdles, but they sure are

fun!

In

other news, Artemesia seems to be losing her youthful bounce at the

same time that Lamb Chop learns to caper --- I guess there can only be

one baby in the family at any given time. As you can see in the photo

above, I upgraded our doeling to a real collar and gave the mini collar

to Lamb Chop. I think our buckling is confident enough in his

masculinity that he won't mind wearing pink. In fact, he'll be old

enough to possibly become a father in just another ten weeks --- then

we'll have to figure out whether Artemesia is willing to go into heat in

the summer for a fall kidding or whether we'll need to separate Lamb

Chop for the summer so he doesn't knock his mother up. Goat management

definitely leaves us with a continuing set of hurdles, but they sure are

fun!

Friday was one of those days

where the truck broke down and the car lost its entire exhaust system.

Nice of it to happen within a

mile of leaving home.

Sometimes I miss taking the

bus.

It's decision time around

here. Do we take the money we've been saving to improve our access and

sink 100 tons of rip rap into the 680 feet of terribly marshy floodplain our driveway currently traverses?

(That sounds like a lot, but I suspect it would be a mere drop in the

bucket.) Or do we use the cash to hire a neighbor with a bulldozer to

try to carve a path out above the floodplain, a task that might come to

naught if he hits bedrock too soon, and one that would require building a

bridge across a rather large gully?

Here's a bit more

information about plan B. After crossing the creek, there's easy access

up onto the knoll you see at the right side of this photo, but the

hillside the bulldozer would be carving into is difficult, to say the

least. There would be a lot of short-term devastation involved (although

perhaps not more than we cause on an annual basis tearing up the wet

soils of the floodplain). And our neighbor warned us that there's no

guarantee he won't hit rock before he's able to carve out enough earth

to make us a road, which would mean we had sunk our money into a project

with no improvement to our access at all.

Then you reach a gully,

which our bulldozing neighbor says would have to be bridged --- he's

pretty sure his equipment won't continue carving around the bank you see

on the right as it runs up this little cove. Instead, he recommended

felling two trees to make a bridge for our ATV (which is the intended

recipient of whichever driveway fix we decide on). Mark and I don't like

the idea of a bridge rotting out under us after a few years, though, so

we might instead see if we could find a big culvert or two to bridge

this gap (and find out whether the bulldozer can haul them in). Unlike

our main creek, this little rivulet dries up in the summer and never

gets big enough to wash a culvert out, so a bridge here is more feasible

than in other locations. (Our most recent flood reached about six

vertical feet up the side of the hill here, but it should stay clear of

the top of the bridge.)

If we were able to carve around the bank and bridge the draw, we'd be home free. Up here is where Joey's yurt

stood, and an old logging road runs between this spot and our core

homestead. All it would take is a little chainsaw work to make the route

passable with the ATV and it's all dry, with no creeks to ford or swamp

to traverse.

It's hard to decide

between plan A and plan B because we don't have any solid cost estimates

for our neighbor's work, for culverts, and for the eventual rock that

would need to go down to hold this driveway possibility into place. Our

neighbor says it would probably take about two days of dozer work,

assuming all goes as planned, but when does anything ever go as planned?

While Mark and I are

mulling it over, I'd be curious to hear your thoughts. Assuming all you

wanted was to be able to haul in manure and straw a few times a year,

would you go for plan A or for plan B? If you were looking for a big

culvert, where would you look and how much would you expect to pay?

We cut our swamp

bridge in half and moved

it to a new location.

The new path will avoid a

spot that was going to need a bridge soon.

Thanks for all the useful

comments on how to avoid losing our bridge the next time it floods.

Next up is to tether a rope to the bridge and tie it off on the medium

Willow next to it.

Are you pulling out your maple taps and plugging the holes? Maybe it's time to tap a birch!

Are you pulling out your maple taps and plugging the holes? Maybe it's time to tap a birch!

Birch trees begin running around when sugar maples let up, making them a

good second crop for people who have already invested in the equipment

for the former and want to extend their syruping season. But birch syrup

isn't the same as maple syrup, of course. For one thing, the former

sells for a lot more --- maple syrup tends to go for thirty-something

dollars per gallon, while birch syrup sells for (by some estimates) ten

times that much.

What's with the excessively high price? I think some of the appeal is

simply that birch syrup is a niche product, added to which you have to

boil down about three times as much birch sap as maple sap to make

syrup. Birch syrup is also reputed to be a bit trickier to produce since

you have to be more careful to keep the sap from scorching, which

likely adds to the price tag. On the plus side, birch syrup is supposed

to have a lower glycemic index than maple syrup and table sugar, being

closer to the value of honey and sorghum molasses. In addition, birch

syrup is often treated as a healthful tonic, perhaps because the extra

boiling means that you're concentrating more minerals in each spoonful

of syrup.

Mark and I aren't

interested in selling birch syrup, but since our maples stopped running

last week, we figured we might as well tap a birch tree and see what all

the fuss is about. I have to admit that I've only boiled down the

barest smidgen of syrup (made from about three pints of sap), but I can

tell that birch syrup is very different from maple syrup. For one thing,

the former is much darker, even in the sap stage. The photo above shows

condensed sap that began life as one gallon of liquid and will still

need to be boiled down considerably before it becomes true syrup. As you

can see, the condensed sap is already much darker than the box-elder syrup beside it.

Another difference

between maple and birch syrup is flavor, although this factor will vary

depending on which species of birch you're tapping. Most birch syrup

sold in the U.S. is made from Paper Birch or Alaska Birch grown in (you

guessed it) Alaska, but our much more southern clime means that Black

Birch is our common species. Although Black Birch twigs taste strongly

of wintergreen, I didn't notice any wintergreen flavor in the syrup we

sampled. Instead, the dark liquid reminded me of sorghum molasses, and

I'd likely use my birch syrup in the same recipes I use with that

southern staple sweetener.

I'd be curious to hear

from folks who have tapped birch trees and made their own syrup. What

did you think of the flavor and how did you use it in the kitchen?

We finished up our new

mushroom logs today.

16 logs total with 3

different varieties of shitake plugs.

It's been a long time since I took our goats out to play. First, the honeysuckle

started to give out, then the snow fell and completely covered

everything edible. But now our grass is just barely starting to grow in

the sunniest part of the yard, so I decided it was high time I started

reconditioning our herd's gut bacteria. Five minutes longer nibbling on

grass each day means that our goats' digestive system will stay happy on

the fresh greenery, and I figure within a week or two the ruminants

will be safe to graze lush grass at will. Abigail thinks this plan is

the ultimate in human stupidity...but I hold the leash.

Well, I try

to hold the leash. I'd meant to walk our little herd to the other side

of our core homestead where sun is really making the grass grow, but as

soon as Abby saw the tall rye coming up in the front garden, she decided

it was time to dine. Rye held little to no appeal this past winter, but

I guess the lush new growth tastes sweeter now --- the leaves even

smell sweeter as I stand by and watch our doe chew. She also went for

tiny new clover leaves barely pushing a quarter of an inch above the

ground, in search of protein to go in her milk, I suspect. Those alfalfa

pellets we bought are being eaten avidly, but who wants dried when they

can have fresh?

Abigail has a voracious

appetite --- making milk uses up lots of calories. In contrast,

Artemesia is just learning to walk on a leash, so our smaller goat spent

much more time figuring out how not to get her feet tangled than she

did eating. As for Lamb Chop, he apparently thinks dirt is tastier than

grass. And who really needs to eat solid food when the milk bar is open?

At the moment, Lamb Chop

is also too young to need a leash. Which is a good thing since I'm not

sure I could handle three goats in my two hands. On the other hand, our

buckling is much braver at two weeks old than Artemesia was at six

months old. When Mark came out for our photo shoot, Lamb Chop kept

trying to follow my husband across the yard rather than staying with the

goat herd. Maybe our buckling has realized that he's one of very few

males on our farm and figures the guys need to hang together?

A short section of nylon rope should keep our foot bridge from floating too far during the next big flood.

If you've sent me an

email or given me a call recently and I've been extremely slow to

answer...blame it on the sun. This bout of stunningly gorgeous weather

means that our usual schedule of half a day working inside and half a

day working outside went right out the window. Instead, Mark and I have

been catching up on all of the fun garden tasks that got put off when

snow was on the ground, barely coming inside for meals and then

collapsing at the end of a long, glorious day. I promise to be a better

correspondent once the cold, wet weather returns this weekend.

Specifically, I've been

weeding and mulching garlic and strawberries, pruning perennials,

transplanting cabbage seedlings, and direct seeding carrots, parsley,

and mangels this week. As I plant, I'm experimenting with the broadfork,

fluffing up half of each bed while simply raking topdressed manure into

the top inch of the other half. It's easy to see the broadfork's

effects right away, with manure filtering down into the looser soil in

the broadforked areas while the fluffed up soil sits higher above the

aisles. I'll keep you posted about germination, growth, and yields of

the roots in the broadforked vs. unbroadforked beds as the results come

in.

Why did I secure a chicken

door with pipe strapping in the goat barn?

Because one of our goats

figured out how to pop the latch and open the door.

Kayla and I enjoyed a girl's day out Thursday --- we attended the annual grafting workshop

at the Gate City extension office. I've been to nearly half a dozen

grafting workshops now, and this one was by far my favorite. Not only

was it held at 2 pm so we could get home before dark, but the selection

of scionwood was astounding. I came in the door with nine pieces of

scionwood I'd brought from winter trades, planning to just graft what I

had...but I walked out with sixteen apple trees. (Good thing they were

willing to sell me extra rootstock for a dollar a pop.)

In addition to the copious scionwood choices, the organizers had three

apple books on hand, so I could look up each variety to see whether it would hit the spot. Yes, I did spend

an hour paging through the books to determine which types of apples were

worth a try. Even though the pages were simply text, I found the most complete book was Fruit, Berry, & Nut Inventory --- I may have to get a copy for future variety selection.

As a side note, I should mention that half of the instruction and most of the scionwood came courtesy of Kelly's Old Time Apple Trees, whose website is rather sparse but who sells both scionwood and full apple trees to ship across the country. Our wedding apple trees came from Kelly's and the fruits are superb! If you don't want to go through the hassle of swapping for scionwood, then Kelly's may be your one stop shopping outlet.

But the positive points

of this workshop went far beyond excellent scionwood selection and a

good time of day. The instructors were also pros who helped me learn

safer and more effective methods of making the classic whip-and-tongue

graft. First, start with their "rule of thumb" --- grasp the rootstock

where the top roots branch off, then cut off the top where the tip of

your thumb reaches. (I figured my thumb was a little shorter than the

digits on their male hands, so cut just a little higher.)

Next (top right photo), hold your knife in your right hand so the beveled edge is up and don't move that hand.

It feels awkward at first, but you'll soon learn how to hold the

rootstock in your left hand with the roots facing away from your body so

you can pull the rootstock away from you against the stationary knife.

This is much safer and makes a much straighter cut than the whittling

method I'd been using.

Finally, for the tongue,

brace the thumb of your knife hand against your other hand (which,

again, feels quite awkward at first), and gently pull the knife into the

wood by sawing it back and forth. Once the knife is seated, finish the

cut by rocking the knife rather than pulling it down. Then slide the two

pieces of wood together, seal them well with grafting tape, cut down to two buds on the scionwood, dab some sealer on the cut end, and you're done!

I'm still far from

perfect, but after sixteen trees, I was starting to feel pretty

proficient. Good thing too since I suspect this will be my last grafting

workshop for a while --- I'm finally running out of spots to put new

trees. Kayla and I are going to have to think of a new girl's day out

plan for next year.

Lucy went on a trip today to

visit our nice vet in the big city.

She got a clean bill of

health and multiple compliments on her beauty.

The different types of

sugars in birch sap compared to maple sap make birch syrup a little

trickier to boil down. It's imperative not to allow the developing syrup

to get above 200 degrees Fahrenheit with birch sap unless you want the

sugars to caramelize, darkening the color and impacting the flavor. In

addition, it's a bit trickier to know when birch syrup is done since it

doesn't get as thick as maple syrup, so you'll need to make your best

guess, then weigh the finished product to determine how close you are to

the optimal 11 pounds per gallon.

Luckily,

our birch tree started running hard when the warm weather came around,

and several days in a row of 1.75-gallon yields gave me enough condensed

sap to try my hand at syrup making. I ended up with about a quarter of a

cup of syrup from three gallons of sap, at a weight of 3.3 ounces for

the final product, which means I actually cooked the liquid down a bit

further than is optimal (even though the syrup still looked pretty

runny, even when cool). This equates to about 192 gallons of sap per

gallon of syrup, requiring half again as much boiling down as even the box-elder sap we experimented with last month and three times as much boiling as our sugar maple sap.

Luckily,

our birch tree started running hard when the warm weather came around,

and several days in a row of 1.75-gallon yields gave me enough condensed

sap to try my hand at syrup making. I ended up with about a quarter of a

cup of syrup from three gallons of sap, at a weight of 3.3 ounces for

the final product, which means I actually cooked the liquid down a bit

further than is optimal (even though the syrup still looked pretty

runny, even when cool). This equates to about 192 gallons of sap per

gallon of syrup, requiring half again as much boiling down as even the box-elder sap we experimented with last month and three times as much boiling as our sugar maple sap.

With a larger supply of

syrup on hand, we were able to try out a more in-depth tasting, this

time substituting birch syrup for the sorghum molasses in our favorite

oatmeal cookie bar recipe. The result was delectable! I'll include the

recipe in my upcoming ebook, Farmstead Feast: Spring, due out in March, but if you'd like some farm-friendly recipes while you wait, Farmstead Feast: Winter is still for sale for only 99 cents. Enjoy!

We discovered today that a

half buried tire makes an awesome goat toy.

Lamb Chop likes to jump from

one to the other.

Last fall, I sent out seeds of some of my tried-and-true

(along with a few experimental) cover crops to readers to see how the

species fared in other soils and climates. My favorite result is shown

above --- Aimee in Ohio planted oilseed radishes in beds that will be

used to grow strawberries this year. She reported: "[The oilseed

radishes] stayed crisp and green clear past Thanksgiving, which gave me a

ready supply of greens and radishes for the guinea pigs. I'll admit it,

I ate a few myself. Even though I am not a radish person, they weren't

bad." Oilseed radishes also got good reviews from Missouri, although

Charity in the Pacific Northwest preferred barley and white mustard in

her garden.

What's coming up this

spring? I splurged on several new varieties, which I plan to try out

both within the garden and as cut-and-come-again mulch producers in the

newly bare aisle soils in areas where I recently mounded up earth to

create higher raised beds. I figured --- why let that bare ground turn

into weedy lawn if it can do double-duty by producing biomass for the

garden instead? (Of course, I may regret this choice when I have to wade

through tall grasses to get to my tomato plants.)

New species on the planting agenda include:

- Barley --- This may be the plant I've been looking for to fill the

early-spring gap before weather warms enough to plant buckwheat. This

grain is supposed to mature enough to flower and be mow-killed in just a

little over two months. I wasn't terribly impressed when I tried barley

as a fall cover crop in the past, but I have higher hopes for its

performance in the spring garden.

- Sorghum-sudangrass hybrids --- I'm trying two different varieties, which look very distinctive in the seed stage (pictured above). I figure this will be a good fit for my aisle experiment.

- Pearl Millet --- This species should fill a niche similar to the sorghum-sudangrass.

- Alfalfa --- In part, I'm growing this legume for the goats since I'm currently buying alfalfa pellets to boost our milking doe's protein intake and calcium levels. But I figured it would also be interesting to see how alfalfa fares as a nitrogen-fixing cover crop left in place for the entire summer.

Want to join in the fun? I