archives for 02/2015

In Natural Goat Care, Pat Coleby says in no uncertain terms that deep bedding is a bad idea with goats. Unfortunately, she doesn't give any information on why

deep bedding is such a terrible idea. So I went ahead and used my usual

methods with our girls, and they haven't seemed to have any problems.

However, a timely post on Throwback at Trapper Creek's blog

suggests that the issue could have to do with bacteria affecting

newborn kids. So I figured I might as well clean out all the deep

bedding in preparation for Mark separating the coop into two stalls for

kidding season. That way, we can keep the kidding stall manure-free just

to be on the safe side.

However, a timely post on Throwback at Trapper Creek's blog

suggests that the issue could have to do with bacteria affecting

newborn kids. So I figured I might as well clean out all the deep

bedding in preparation for Mark separating the coop into two stalls for

kidding season. That way, we can keep the kidding stall manure-free just

to be on the safe side.

The girls had different

reactions to me invading their home for the afternoon. Abigail promptly

settled in to eat more hay, refusing to move her feet when the time came

to scoop beneath her. Artemesia, on the other hand, asked if she could

help me out. Maybe standing in the doorway would help? How about if she jumped up in the wheelbarrow? "You lifted me out? Oh, great, I can jump back in --- that's the fun part!"

I'm tossing all of the

used bedding over the fence into the tree alley in hopes it will build

the soil and maybe kill back some of the weeds. I'll lay down some

cardboard on top, if necessary, to turn this into a zone to plant fodder

crops for next fall. On the menu are field corn (with the grain being

earmarked for the chickens and the stalks for the goats), sunflower

seeds, sweet potatoes, mangels, and carrots. The last two on the list

will probably go in the main garden, though, since this rough kill mulch

won't make soil good enough for carrot-like roots...at least not for

this year.

I'd be curious to hear

from other goat keepers. What do you grow for your goats? Have you had

any trouble keeping your herd on deep bedding?

We staged some materials to finish our IBC water tower project but had to use a few 2x4's for the new kidding stall.

On warm, sunny days in January and February, I itch to be out in the garden, so I

often turn to pruning. However, last winter, I felt like my wintry

pruning bout may have been responsible for killing off the spring shoots

of our everbearing raspberries, so this year I decided to research

before pruning.

Unfortunately, the conclusion I drew after reading several scientific

articles was...it's complicated. Winter hardiness is affected by a

variety of factors, including how dormant the tree is at the time, the

recent air temperature, the plant's maturity, and more. So, although

most orchardists agree that fall pruning will lower your fruit plants'

winter hardiness for months afterwards, few are willing to go out on a

limb and give you a firm date after which it's safe to prune during the

dormant season. In fact, the data made me wonder whether, from a tree-health

point of view, you wouldn't be better off waiting to prune until after

the tree's flowers have opened in the spring.

On the other hand, pruning not only makes a tree less winter hardy; it

also makes the tree's flowers more sensitive to cold. Critical temperatures

for

peach blossoms, for example, can vary by as much as ten degrees based on

factors that include the temperature just before the freeze and whether

the tree has been recently pruned. So maybe we really shouldn't

be winter pruning at all and should stick to the summer pruning and

training that has become much more of a staple on our farm.

But, on the third hand, there's just so much more time for careful

pruning at this time of year than there is in the summer when every

plant is breathing down my neck and asking for attention. So, I'll

probably winter prune anyway, maybe taking Lee Reich's advice of pruning

in February, or following the Iowa State University guideline of

pruning between late February and early April. Because, after all, we do have

to compromise between what's best for us and what's best for the trees

--- and what's best for me is to enjoy pruning under the winter sun

before the vegetable garden begins to consume all of my attention.

We celebrated Ground Hog Day

today by taking the day off.

Our friend Richard made this

cool drawing on how we might change the way our IBC

water tower is going together.

It's

time to start planning your 2015 garden, and for many of us, roots will

be a large part of our planting. Mark and I love to stock up on carrots

for fresh eating throughout the winter months, and now that we've added

goats we'll be expanding our root repertoire. But how do you store

those crunchy carbohydrates?

It's

time to start planning your 2015 garden, and for many of us, roots will

be a large part of our planting. Mark and I love to stock up on carrots

for fresh eating throughout the winter months, and now that we've added

goats we'll be expanding our root repertoire. But how do you store

those crunchy carbohydrates?

$10 Root Cellar

walks you through growing, storing, and using root vegetables for

animals and humans alike. And you're in luck because the book is on sale

for 99 cents today! Grab your copy while it's cheap and plan ahead for a

more self-sufficient year.

(By the way, what do you think of my pretty new cover? Credit for the awesome photo goes to Stephen Ausmus at the U.S. Department of Agriculture.)

As I began setting aside garden areas to grow fodder crops for goats,

I realized that I needed to do some math. I'm starting to get a handle

on how much supplemental feed Abigail needs to stay in good shape while

pregnant, and I assume she'll need a similar ration while milking. So,

based on that data, how much space would it take to grow the

supplemental feed for one small milk goat during the six-month cold

season?

Abigail didn't seem to

need much other than hay during the beginning of the winter while her

pregnancy was in its early stages, so I figure a sixth of a head of

sunflowers and a carrot per day would provide the bulk of her ration

during that time. In addition, I've been matching her carrot ration with

a similar amount of butternut squash or sweet potatoes lately, figuring

that variety is good for our goat's health, and I'll include mangels in

that extras list next winter. For the sake of easy math, I then doubled

that ration for the late pregnancy and early milking months, resulting

in the feed amounts listed below:

| Weekly ration (Oct. - Dec.) |

Weekly ration (Jan. - Mar.) |

Total ration |

|

| Heads of sunflowers |

1.2 |

2.4 |

43 |

| Carrots (large) |

7 |

14 |

252 |

| Butternuts (small) |

1 |

2 |

36 |

| Sweet potatoes (small) |

0.5 |

1 |

18 |

| Mangels (small) |

0.5 |

1 |

18 |

Next, the question

becomes, how much space would I need to grow that much feed? Using

low-ball figures on yield for each of our 5-foot-by-3-foot beds (better

safe than sorry), I came up with:

| Yield/bed |

# beds |

Square feet |

|

| Heads of sunflowers |

15 |

2.9 |

43 |

| Carrots |

150 |

1.7 |

25 |

| Butternuts |

15 |

2.4 |

36 |

| Sweet potatoes |

15 |

1.2 |

18 |

| Mangels |

40 |

0.5 |

7 |

| Total |

8.7 |

129 |

That's really not much

space at all to provide a goat all of her feed except hay! Of course, by

this time next year, Artemesia will be pregnant too, so we'll need to

double those numbers. And we might also need to add on some supplemental

feed for the summer months, so I'll triple the chart's estimates to be

on the safe side. Still, considering that I plant nearly ten times that

much area for me and Mark, a few extra beds of butternuts tucked away in

a corner shouldn't be too much skin off my teeth, especially since all

except the carrots (and possibly mangels) are on my ultra-easy-to-grow

list.

Does Box Elder sap taste as

good as Sugar

Maple sap?

We tapped our first Box Elder

today to find out.

I went out into the woods last weekend looking for tree species on the shiitake-favorites list...and

ended up stumbling across not one but two places with white oaks

perfect for the cutting! I guess I wrote too soon when I said our farm

is too low and wet for oaks.

The great thing about the

oaks I found is that they're close to our core homestead and they're

double-trunked. The latter factor means that cutting down one trunk is

equivalent to pruning the tree, not killing it. In fact, when Mark cut

the trunk he's currently working on in the photo above, I could tell

that the top part was already starting to die back as the larger trunk

took up more and more of the tree's nutrients. Using up the base of the

trunk for mushroom logs and the top for firewood won't be taking much

out of our forest ecosystem at all (although the woodpeckers may miss

the snag for nesting).

I had planned to cut one

of the double trunks from the tree in the foreground of the first photo

as our second tree, but in the end I decided to give that individual

another five or ten years to grow. I wouldn't have gotten many mushroom

logs out of the trunk as-is, so instead I opted to let Mark cut a

single-trunked oak that was just the right diameter. I think

this tree will sprout back from the base (since that's how our

double-trunked trees arose in the first place), so hopefully we'll have

more mushroom logs there...in about forty-five years. (Yes, counting the

rings of one of the cut oaks showed it to be just about Mark's age.)

In Organic Mushroom Farming and Mycoremediation

(a top-notch book that I'll be reviewing later this month), Tradd

Cotter recommends cutting logs about a week before plugging with spawn

to give the tree's natural defenses time to dissolve. At the other

extreme, you might get away with waiting as long as two months between

cutting and plugging for oaks, but sooner is generally better than later

since wild mushroom spawn can invade if you wait too long. But don't

inoculate if you're going to see prolonged periods below 18 degrees

Fahrenheit in the near future --- instead, keep the spawn in the fridge

and wait until the weather warms up a bit. Hopefully our weather will

cooperate and we'll be able to plug our oak logs week after next.

When

Artemesia gets bored, she starts jumping on things. And since her belly

is smaller than Abigail's, even an afternoon of nibbling cover crops

counts as boring for our little doeling.

When

Artemesia gets bored, she starts jumping on things. And since her belly

is smaller than Abigail's, even an afternoon of nibbling cover crops

counts as boring for our little doeling.

Last weekend, I had the terrifying image of Artemesia hopping up onto our well housing...and falling down the hole. A well cover will keep the water cleaner and will also give us some peace of mind.

Sometimes

when I overthink a project, I back myself into a corner and nothing

ever gets done. For example, re-insulating the lower part of the trailer

would, in a perfect world, go in this order:

Sometimes

when I overthink a project, I back myself into a corner and nothing

ever gets done. For example, re-insulating the lower part of the trailer

would, in a perfect world, go in this order:

- Add insulation under the floor everywhere that the original insulation has fallen out (and perhaps replace the stuff that's still in place while I'm at it).

- Run insulated skirting around the entire trailer to fill in the gap between the walls and the ground.

- Add on porches and other structures onto the sides of the trailer.

But the problem with this

campaign is that I haven't wrapped my head around the best way to

insulate under the floor, and that's also the project I care about the

least. As a result, somehow two porches ended up attached to the trailer

before I'd even begun step one of my reinsulation project.

Still, it did seem like a good idea to install the skirting behind the mushroom tower

before we started putting mushroom logs and water-tower braces in

place. Luckily, I discovered that it's not all that difficult to do the

tasks in the wrong order --- yes, I had to crawl under the porch and the

trailer, but I embraced my inner coal miner and survived.

So maybe I was wrong with my original plan. Maybe it should have been:

- Do what I think is the most fun first.

- Then do whatever suits my fancy next.

- And finish up with what's left.

Turns out you can use a

ribbon to estimate the weight of your goat.

Artemesia was very

interested...Abigail not so much.

(This picture of Mark and Artemesia is totally unrelated to this post. But aren't they cute together?)

Now

back to the point.... I'm experimenting with offering some of my ebooks

beyond Amazon at the moment, and I'm hoping I can bribe you into

helping me out by leaving a review on one or more of the new sites. I

decided to start off with Permaculture Chicken: Incubation Handbook and The Naturally Bug-Free Garden.

The first book is perfect for folks who are considering hatching

homegrown chicks this spring (or who just want to learn about pasturing

very young birds) while the second will get your garden off to a good

start (and will be hitting bookstores next month!).

Now

back to the point.... I'm experimenting with offering some of my ebooks

beyond Amazon at the moment, and I'm hoping I can bribe you into

helping me out by leaving a review on one or more of the new sites. I

decided to start off with Permaculture Chicken: Incubation Handbook and The Naturally Bug-Free Garden.

The first book is perfect for folks who are considering hatching

homegrown chicks this spring (or who just want to learn about pasturing

very young birds) while the second will get your garden off to a good

start (and will be hitting bookstores next month!).

But don't take my word for it! You can download a free epub copy of either or both between now and February 11. Just use the code QB38N at Smashwords for Incubation Handbook and the code SX87Z at Smashwords for The Naturally Bug-Free Garden.

Then, if you enjoy what you read, please use the links below to leave

reviews on any retailers where you have an account (and also feel free

to copy and paste reviews from Amazon if you've already read and

reviewed there).

Here are the links for Permaculture Chicken: Incubation Handbook:

Here are the links for Permaculture Chicken: Incubation Handbook:

- Amazon

- Barnes & Noble

- Google play

- iTunes

- Kobo

- Scribd

- Inkterra

- (and also Tolino, but I can't quite figure out how to find the link since their page is in German)

And for The Naturally Bug-Free Garden:

- Amazon

- Barnes & Noble

- Google play

- iTunes

- Kobo

- Scribd

- Inkterra

- (and also Tolino, but I can't quite figure out how to find the link since their page is in German)

"Yeah, yeah," I can hear you

saying. "What's in it for me?" I'm glad you asked. I really appreciate

the time you take leaving your reviews, so if you do so on any of the

sites listed above (including Smashwords and Amazon), you'll be eligible

to enter our giveaway using the widget below. One lucky winner will take home a heaping helping of homesteading books:

- A signed copy of The Weekend Homesteader

- A signed copy of The Naturally Bug-Free Garden (which may ship separately --- I haven't gotten them in my grubby little hands yet)

- Creating a Life Together (a step-by-step guide for building intentional communities)

- Gaia's Garden (an introduction to home-scale permaculture)

- Create an Oasis with Greywater

- Success with Baby Chicks

That's

a $92 value, and a huge amount of homesteading wisdom at your

fingertips --- I hope the bribe is sufficient to get you to enter. Thanks in advance for your help as I expand my readership beyond Amazon!

The solution is to cut until just before the trunk starts to bend back and pinch the chainsaw's bar...

...then push over the tree.

There are quite a few reasons to estimate your goats' weight

on a regular basis. With a doeling, most sources recommend that you

wait to breed her until she's attained 70% of her adult weight, and it's

also handy to keep track of all kids' weight as they grow to make sure

they're doing well.

With adult goats,

frequent weigh-ins help you decipher feeding regimes, medications, and

possible parasite loads. For example, most sources recommend that a goat

be allowed to eat 10% of her body weight in hay if she's not on

pasture. Similarly, you should expect a mature goat to put on a little

weight naturally in the spring when the grass greens up, perhaps to lose

a bit during hot spells in midsummer, then to bulk up a bit again in

the fall. If she's losing weight when she should be gaining, you might

need to focus on deworming.

But it's tough to get an

accurate weight measurement on a goat. First of all, you either need an

animal scale, or you need to pick up the goat (tough for a goat like

Abigail who is not

interested in being manhandled; the photo above comes from this past

fall, when our herd boss was less pregnant and thus less sensitive about

her belly). Similarly, that 10% weight gain after eating her morning

hay is going to completely throw off the measurement.

Enter the goat-girth

chart or the (slightly) more complicated body-weight formula. In the

case of the former (which is accurate to +5%

on standard-sized dairy goats), you measure around the goat's body just

behind their armpits and shoulder blades, then convert from inches to

pounds using the table below. (Be sure to pull the tape tight, and to

take into account fluffy winter hair.) If you want to be more accurate,

you can use the formula right after the chart, which adds in a second

measurement --- the goat's length --- to add in a bit more accuracy.

| Heart girth (inches) | Weight (pounds) | Heart girth (inches) | Weight (pounds) | Heart girth (inches) | Weight (pounds) |

| 10 3/4 | 5 | 20 | 30 | 32 | 100 |

| 11 3/4 | 6 | 21 | 34 | 33 | 105 |

| 12 3/4 | 7 | 22 | 38 | 34 | 115 |

| 13 1/4 | 8 | 23 | 43 | 35 | 125 |

| 13 3/4 | 9 | 24 | 50 | 36 | 140 |

| 14 1/4 | 10 | 25 | 56 | 37 | 150 |

| 14 3/4 | 11 | 26 | 62 | 38 | 160 |

| 15 1/4 | 12 | 27 | 68 | 39 | 170 |

| 16 | 14 | 28 | 73 | 40 | 180 |

| 17 | 16 | 29 | 80 | 41 | 190 |

| 18 | 22 | 30 | 85 | 42 | 200 |

| 19 | 26 | 31 | 90 | 43 | 215 |

Here's the formula: (If you put in inches, then you'll get pounds.)

You can buy tape measurers that automatically convert the heart girth to pounds,

or you can make your own the way I did using a bit of ribbon. While my

ribbon won't be as accurate as using the formula, it should give me an

idea of relative weight gains and losses for our girls, and will

definitely make my life easier since I can just pull it tight around

Artemesia's chest and call out "37 pounds!" (That was my first measurement, but the girls were so  caught

up in enjoying the bright yellow ribbon that they wiggled like crazy

during the first trial. Next time, I'll try measuring while they're

chowing down on breakfast, a period when even Abigail lets me check

beneath her tail, feel under her belly for babies (who kicked

Thursday!), and probe the tendons on either side of her tail to search

for signs of impending birth.)

caught

up in enjoying the bright yellow ribbon that they wiggled like crazy

during the first trial. Next time, I'll try measuring while they're

chowing down on breakfast, a period when even Abigail lets me check

beneath her tail, feel under her belly for babies (who kicked

Thursday!), and probe the tendons on either side of her tail to search

for signs of impending birth.)

Adding this data to my

rough body-condition measurements (feeling for fat in various locations

along the body) should help make sure I feed our girls just enough but

not too much. I'm not sure that Abigail could

eat too much food right now, but since we've decided not to breed

Artemesia at her bare-minimum age, we'll have to be careful that she

doesn't get too fat while waiting for her fall date with a buck

(possibly one of Abigail's kids?). Good thing our little doeling thinks a

measuring tape around her chest is as good as a hug!

We thought a layer of flashing would keep most of the moisture away from rotting our new well cover.

I was stunned by the productivity of the one box-elder tree we tapped --- after a single bright, sunny day, our two-gallon bucket was nearly completely full!

I usually cook down my

sap in stages, letting a pan of the liquid sit on the wood stove until

it's partway cooked down, then later combining that sap with other

partway-cooked-down  sap

to cook up a larger batch of syrup. But I wanted to know right off the

bat whether box-elder syrup was worth making, so I took our bucket full

of sap and cooked it all the way down over the course of 24 hours. The

result was a quarter of a cup of syrup that lacked the bright gold color

of maple syrup and the delicate vanilla-like scent, but tasted every

bit as good. (Mark said the box-elder sap might be slightly less sweet

per unit volume, but he still licked his lips after the taste test!)

sap

to cook up a larger batch of syrup. But I wanted to know right off the

bat whether box-elder syrup was worth making, so I took our bucket full

of sap and cooked it all the way down over the course of 24 hours. The

result was a quarter of a cup of syrup that lacked the bright gold color

of maple syrup and the delicate vanilla-like scent, but tasted every

bit as good. (Mark said the box-elder sap might be slightly less sweet

per unit volume, but he still licked his lips after the taste test!)

I realized in the process

that I'd never actually gotten a comparable figure for how much syrup

we get out of sugar-maple sap, so I took the half gallon of sap that

came from our sugar maple during the same time period and cooked it

down, resulting in an eighth of a cup of syrup.

For those keeping track

at home, that means my box-elder sap-to-syrup ratio is 115:1, while the

sugar-maple sap-to-syrup ratio is 64:1. On the other hand, we got nearly

four times as much sap from the box-elder during the same time period,

so actual yields of syrup from the two trees were twice as high for the

box-elder!

The good news is that we

have hundreds of box-elders within easy tapping distance. The bad news

is that, if we go beyond tapping a tree or two at a time, we actually

have to put effort into the operation. Mark asked me to estimate how

many human-hours it took to create half a cup of maple syrup (what we'd

produced in January) and I figured about an hour, if that. The reason

the project has been so un-time-consuming in the past is that the sap

bucket is right on my daily walk, so it only takes a couple of minutes

to swap out containers each day. After that, the sap just sits on top of

the wood stove, which we're running anyway to heat the trailer, so

energy use is also kept at a minimum. For larger amounts of sap, we'd

have to make special sap-carrying trips and figure out some way to cook

down the sap efficiently (probably outside).

We'll have to put some thought into the right size for our own syruping

operation --- the sweet spot, if you will. In the meantime, I'm

experimenting with maple-syrup recipes for the next volume in the Farmstead Feast series and am taking suggestions. Other than poured over pancakes, what's your favorite way to eat maple syrup?

We installed a tether

ball today for the goats

to play with.

It started raining as we

finished up so we'll have to wait for a dry day to see how athletic

our girls are.

As Abigail gets closer to

B-day (which could be now or at the end of the month), I'm easing her

into the milking routine. She needs that extra attention since, unlike

our little lap goat, Abigail isn't a big fan of being fondled. But over

the last week or so, I've gotten our pregnant goat to the point where

she doesn't mind me feeling under her belly and along her tendons and

looking under her tail as long as she's chowing down on her morning

ration. So I figured it was high time we started moving her to the milking stand before her morning OB/GYN appointment.

Although most of you will

probably think it's crazy, we're considering leaving the milking stand

on the front porch. The plus of this location is that it's far away from

manurey bedding and is thus quite clean. Plus, it's close to the fridge

and running water, making the prep and aftermath of milking easier.

On

the negative side, Lucy gets fed on this porch at the moment, and our

loyal dog is not a fan of anyone except herself and humans eating there.

As obedient as ever, Lucy did

allow the goats to usurp her porch Sunday morning, but I could tell our

dog was edgy due to the amount of split firewood she dragged off into

the yard to gnaw on. And Lucy's edginess made Abigail edgy, so our

pregnant goat didn't allow me to feel her up the way I usually do.

On

the negative side, Lucy gets fed on this porch at the moment, and our

loyal dog is not a fan of anyone except herself and humans eating there.

As obedient as ever, Lucy did

allow the goats to usurp her porch Sunday morning, but I could tell our

dog was edgy due to the amount of split firewood she dragged off into

the yard to gnaw on. And Lucy's edginess made Abigail edgy, so our

pregnant goat didn't allow me to feel her up the way I usually do.

Meanwhile, Artemesia

proved to be even more of a problem. Our little doeling kept trying to

hop up onto the milking stand, causing Abigail to butt her off. Then the

doeling started exploring the porch, so I ended up tying her to one leg

of the milking stand. Unfortunately, I haven't been training Artemesia

to understand being tied to a leash, and so spent a lot of effort trying

to figure out why she couldn't ramble whimsically about.

So, maybe the porch wasn't such a good idea after all. Or maybe everyone just needs a few days to settle into the new routine?

In the meantime, I'm

hoping that some experienced goatkeepers will help me determine how soon

after kidding we should start milking our goat. My plan is to shut the

kids into the kidding stall

for the night, milk Abigail in the morning, then let the kids spend the

day with their mom. But when do I start milking? Various sources tell

me I should wait three days, two weeks, or much longer between kid birth

and starting to steal the kids' dinner. What do you do?

Our 2nd

utility wagon is going on

two years old.

The wagon structure is

holding up well, but the air tends to leak out of the tires after a few

weeks.

We might add inner tubes to

each wheel, but for now we just use the foot pump to add air on firewood hauling

days.

Blog-reader Ron pointed me toward the best shiitake-mushroom writing I've read to date...which you can download free here. Best Management Practices for Log-Based Shiitake Cultivation in the Northeastern United States

has a dry, scientific title, but the interior is full of photos and is

quite easy to read. In fact, I highly recommend you take the time to

peruse all 57 pages if you're thinking of growing shiitakes in logs, but

I'll sum up some of the most interesting points here in case you're

short on time.

Blog-reader Ron pointed me toward the best shiitake-mushroom writing I've read to date...which you can download free here. Best Management Practices for Log-Based Shiitake Cultivation in the Northeastern United States

has a dry, scientific title, but the interior is full of photos and is

quite easy to read. In fact, I highly recommend you take the time to

peruse all 57 pages if you're thinking of growing shiitakes in logs, but

I'll sum up some of the most interesting points here in case you're

short on time.

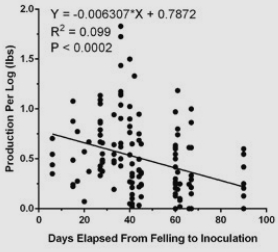

My favorite part of the

text was the copious data. The file is full of real numbers about the

best time to cut logs (winter and spring), the best number of days to

wait before inoculating (none --- although when I look at the graph

below, I wonder if a parabola wouldn't have been a better fit for the

data than a straight line?),

the best trees to inoculate (oak, sugar maple, ironwood, hop-hornbeam,

and beech), the number of flushes to expect from a log (8 from red oak, 4

to 5 from red maple, all over the course of 3 to 5 years), and much  more.

Interestingly, the scientists in charge even reported on blind taste

tests, where they found that shiitakes grown on ironwood were considered

bland while those on bitternut hickories were prized by top chefs.

more.

Interestingly, the scientists in charge even reported on blind taste

tests, where they found that shiitakes grown on ironwood were considered

bland while those on bitternut hickories were prized by top chefs.

Equally useful was the

authors' sum-up of the differences between the three categories of

shiitakes: wide-range, warm-weather, and cold-weather strains. In the

past, I'd just assumed that these distinctions referred only to fruiting

times, but mushrooms in each category actually tend to act and taste

quite different as well. Cold-weather strains are nice for low-work

backyard producers like us since they generally start fruiting on their

own (actually preferring not to be shocked

in most cases), can be inoculated into larger logs since you won't have

to wrestle the substrate into and out of water to force fruiting, and

often have the most intense flavor in their fruits. Wide-range strains

are also a good choice for beginners because logs fruit quickly after

inoculation and recover rapidly between shock treatments. Finally,

warm-weather strains are optimal if you only have softer hardwoods like

red maples available, or if you need to make sure you'll have a

dependable harvest throughout the summer months.

Our spawn is already in

the mail as I type, so it's too late to pick out varieties with this new

information in hand. But I'm hopeful the types of shiitakes we chose

will do well on our farm. Here are the descriptions for our three new

strains (shamelessly copied from Field and Forest Products' website):

- Snow Cap Shiitake (cold weather) --- Produces beautiful, uniform, thick fleshed caps tufted with white lacey ornamentation. A long natural outdoor season makes it a favorite for those who like to visit their logs regularly. Heaviest fruiting occurs early spring and late fall. Possibly the best winter strain in the South.

- WW70 Shiitake (warm weather) --- This warm/cool weather strain has characteristics close to a CW strain. Its late summer - late fall fruiting period outdoors is one of the longest of all our strains. It is also one of the most beautiful, with dark caps and lots of contrasting ornamentation. Please note that WW70™ does not respond well to force fruiting.

- Native Harvest Shiitake (wide range) ---

Naturalized on our farm several years ago, this strain has been tested

from North to South and the results are the same: a very fast, vigorous

strain with excellent quality. First found on oak, it is also a good

producer on Red Maple. Unlike other wide range species, Native Harvest™

also gives a late fall flush; an added bonus for the Thanksgiving table!

Spawn run is 6 to 12 months.

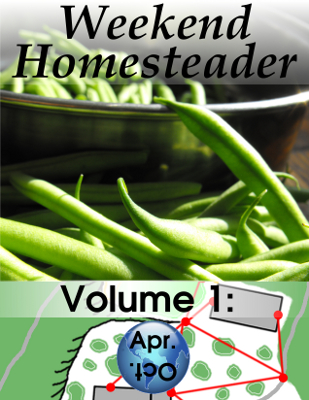

A huge thank-you to those of you who have entered my

homesteading book giveaway by downloading and reviewing a free copy of

The Naturally Bug-Free Garden and/or Permaculture Chicken: Incubation

Handbook! You've

still got a couple of days left to win $92 worth of homesteading books,

and I've got one more option for you to review. Weekend Homesteader: April

covers the first four projects in my Weekend Homesteader series,

including tips on why and how to start a no-till garden from scratch.

The book is currently free (and seeking reviews) on:

A huge thank-you to those of you who have entered my

homesteading book giveaway by downloading and reviewing a free copy of

The Naturally Bug-Free Garden and/or Permaculture Chicken: Incubation

Handbook! You've

still got a couple of days left to win $92 worth of homesteading books,

and I've got one more option for you to review. Weekend Homesteader: April

covers the first four projects in my Weekend Homesteader series,

including tips on why and how to start a no-till garden from scratch.

The book is currently free (and seeking reviews) on:

Take a look, and if you

like what you see, I'd really appreciate it if you left a review to help

the book get a head start on those new retailers! Then come back over

here and plug in your information for a chance to win a bundle of

homesteading paperbacks.

I installed this battery

disconnect switch to

prevent a small short in our truck from draining the battery.

It's a well built product

that was easy to install.

Hooking up the battery cable

to the switch first gives you a little more wiggle room to get things

tightened. You have to reach under a heater hose to reach the knob, but

it's a whole lot better than jumping the truck every time we need to use

it.

The first recipe I tried with our homemade maple syrup

was meringues. I'm looking for a recipe that you can make using

homegrown ingredients and that really showcases the maple-syrup flavor,

and the meringues came in as a definite...maybe.

The first recipe I tried with our homemade maple syrup

was meringues. I'm looking for a recipe that you can make using

homegrown ingredients and that really showcases the maple-syrup flavor,

and the meringues came in as a definite...maybe.

The sticking point (quite

literally) is that if you don't have parchment paper, your dessert will

crumble to pieces when you try to pry the cookies off the pan. Also,

Mark didn't realize until prompted that the cookies were made with maple

syrup --- instead, he felt that they tasted like vanilla wafers. Still

tasty enough to eat up all the crumbs, though!

Here's the recipe in case you want to try this simple recipe at home. Ingredients:

- 2 egg whites

- 0.5 cups maple syrup

- pinch of salt

Preheat the oven to 200

F. Beat the eggs until soft peaks form, then add the maple syrup and

salt. Mix lightly, then spoon onto a cookie sheet (or two) lined with

parchment paper. Bake in the middle to upper rack for 60 to 75 minutes,

until the meringues are starting to turn golden brown. The maple syrup

means that these meringues will cook a shorter time than that listed in

most recipes, so be careful not to let them burn!

In other syrup-related

news, we've produced about a pint of syrup so far in 2015, and I'm

starting to work the kinks out of my low-tech production methods. When I

bring home a bucket of sap, I immediately put the liquid in a skillet

on the wood stove if we're currently heating the house. Unattended

(perhaps over multiple days if the weather is warm), I cook the sap down

until it's perhaps a fourth of its original volume, then I sock that

concentrate away in a big jar in the fridge until I've got about half a

gallon to a gallon of the condensed sap.

When the fridge is

getting overloaded with sap jars, I throw the condensed sap back on the

wood stove until it once again cooks down to a fraction of its original

volume. When I start seeing white bubbles, though, I take the skillet

off the wood stove and put it on the electric  stove

where I can monitor it more closely. Next, I cook on medium to high

heat until foam over --- when the sap suddenly starts creating a huge

amount of big white bubbles that fill the entire pan. At this point, I

stir frequently and watch the clock, aiming for 1.5 to 2 minutes of

further cooking to create the perfect maple syrup.

stove

where I can monitor it more closely. Next, I cook on medium to high

heat until foam over --- when the sap suddenly starts creating a huge

amount of big white bubbles that fill the entire pan. At this point, I

stir frequently and watch the clock, aiming for 1.5 to 2 minutes of

further cooking to create the perfect maple syrup.

As you can see from the

sap-sickle at the top of this post, our weather is still too cold for

strong sap runs, but we've had a few good days so far. It sure is fun to

come home from my morning walk with a bucket of subtly sweet liquid

that I know will turn into a delightful project and a delicious addition

to our late-winter meals!

One downside to using a bucket

to collect sap is the bugs.

We modified this lid with a

piece of metal screen material to help keep our sap more pure.

The first chorus frog

creaked its spring call from the woods Wednesday and the first male

hazel catkins softened into bloom. Meanwhile, Kayla and I spent the

afternoon with our hands sunk deep into the soil, preparing a bed for

spring lettuce and mulching some overlooked garlic. In fact, it was so

warm that even Huckleberry came out to help with our garden tasks.

But I won't be planting

lettuce (or peas) quite yet. Even though I mark February 2 as the first

outside planting of the year, I play the actual date by ear, keeping an

eye on the weather and on soil temperatures.

With temperatures due to plummet today and to stay below freezing for

the foreseeable future, I opted to simply lay down some dark-colored

compost and erect quick hoops to continue heating the lettuce-bed soil,

but to keep my seeds inside where they can stay warm and dry.

Good thing too since our farm looked very different 22 hours later! Fingers sure do get chilly when you cut scionwood in the snow.

We tried to get a big truck

of 6 inch rock delivered today.

The driver had some problems

with our driveway and had to give up after several failed attempts.

Now we need to either find

someone with a smaller dump truck or do some repair to our driveway.

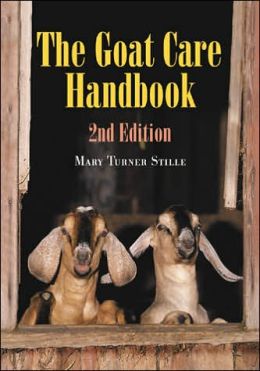

Whenever

I get excited or worried about a topic, I pick up a book to ease my

mind. I'm pretty excitable, so I read a lot...especially while waiting

for my first doe to give birth.

Whenever

I get excited or worried about a topic, I pick up a book to ease my

mind. I'm pretty excitable, so I read a lot...especially while waiting

for my first doe to give birth.

That said, I picked up Mary Turner Stille's The Goat Care Handbook

largely because I had read part of the text during a google search and

was impressed by her astute advice. "Don't trim the hooves of a pregnant

doe after the third month of gestation," she warns, "unless she is very

docile because her struggles may harm her and the unborn kids." Stille's firsthand experience from decades of goat care came through in that simple admonition, so I had to read the entire book.

And I'm glad I did since the text offered answers to other questions

that had been niggling against the back of my mind for weeks. For

example, I've often wondered how much time you'd have to allot to

goat-dining if you wanted to keep your herd penned up, giving them all

of their feed by taking them out into the woods to browse daily. Stille

actually kept goats in this manner for a while and found that her goats

required about an hour in the morning and an hour in the evening for

eating. In addition, she mentioned that she found the same grazing times

in pastured goats when she later had fences in place (with the

remainder of the day spent chewing cud, napping, and playing). I guess

my half-hour of honeysuckle herding (until we ran out last week) was making a bigger difference in our goats' dietary intakes than I'd assumed!

Although

I've promised Mark not to lobby for any new livestock for at least a

couple of years, I was also intrigued by Stille's information about

combining goats with other animals. She wrote that a goat mixed in with a

flock of sheep makes the woolly livestock easier to handle since the

goat will come when you call and the sheep will follow. Similarly, one

calf mixed in with goats will eat the waste hay (which goats won't touch

once it hits the ground) and will keep the pasture more evenly mowed.

(Unrelatedly, but still interesting, Stille is a fan of deep bedding on a dirt floor for goats, unlike Pat Coleby,

although Stille does warn that bacteria can get into caprine hooves if

you're not careful to keep bedding dry on top and hooves well trimmed.)

Although

I've promised Mark not to lobby for any new livestock for at least a

couple of years, I was also intrigued by Stille's information about

combining goats with other animals. She wrote that a goat mixed in with a

flock of sheep makes the woolly livestock easier to handle since the

goat will come when you call and the sheep will follow. Similarly, one

calf mixed in with goats will eat the waste hay (which goats won't touch

once it hits the ground) and will keep the pasture more evenly mowed.

(Unrelatedly, but still interesting, Stille is a fan of deep bedding on a dirt floor for goats, unlike Pat Coleby,

although Stille does warn that bacteria can get into caprine hooves if

you're not careful to keep bedding dry on top and hooves well trimmed.)

In the end, I'd still recommend Storey's Guide to Raising Dairy Goats as the first book for most beginners to read. But The Goat Care Handbook would make a good second read, especially if paired with Raising Goats Naturally. Of

course, the real test will be to see which goat book, if any, stays on

my shelf more than a year or two since I cull my collection just as

ruthlessly as Stille recommends culling your goats. Stay tuned to see

which goat book stands the test of time...more details to come in 2017.

I moved our goat

tether ball to the door

frame.

It took a few days but they

started to play with it yesterday.

Artemesia figured out how to

get her front feet on top of the ball enough to use it to launch

herself up and out the door like one of Santa's reindeer.

Abigail followed her lead by

bumping it with her horns but was first more interested in saying hi to

Lucy.

I wondered how long it would take for our five ducks to find the larger of our two creeks. And I also wondered --- if they took to the water, would they ever come back?

The answer is: February. And: yes.

I have to admit that our

ducks are growing on me. Chickens are so much more malleable, but ducks

have their own appeal if you're able to let them roam semi-wild across a

swampy property. (Outside

the core perimeter, of course, so they don't bother the garden.)

Despite their white color, we haven't lost a single duck to predators,

and the waterfowl continue to average an 80% lay rate throughout the

cold, dark winter. In contrast, our hens are only at about 50% at the

moment.

When two mallards (wild

version of the same species) flew over last week, I actually had a

random thought that maybe a drake would drop in and inseminate our tame

ducks, then she'd go broody and produce some ducklings to perpetuate the

local population of the species. A very slim shot...but I actually

wouldn't mind keeping ducks around for a while longer, if only to watch

them dabble in the creek...and to enjoy those big, midwinter eggs.

Our creek freezing is an

indicator that the previous night got down close to zero degrees.

Some part of our buried water

line froze last night. We added an extra electric

pipe heater to the part that enters our kitchen a few days ago and

thanks to that extra bit of warmth the line thawed just after lunch

which is a big improvement from last Winter.

To ensure a steady supply

of shiitakes, you should inoculate new logs every three to five years.

We inoculated logs in 2007 and 2009, but by 2013, were feeling in need

of more shiitakes.

Unfortunately, the plugs

we ordered that winter arrived looking like plain wooden dowels,

apparently mycelium-free. I trusted the source, though, so Mark and I drilled holes, pounded the plugs in, waxed over the holes...and waited.

Unfortunately, nothing

happened, and I eventually realize that I should have trusted my gut.

Here's your warning: if your spawn arrives and the substrate doesn't

appear to be coated with white mycelium, something might be wrong.

Fast forward ahead two

years. We decided to order from a different company this time around

(Field and Forest Products, whose spawn has always grown like

gangbusters for us). And sure enough, the plugs arrived fuzzy with

mycelium...but frozen solid!

This time, the issue was

entirely my own fault. I knew the spawn was shipping, but didn't change

my routine of walking Lucy out to check the mail the morning after it's

delivered rather than catching it on day one. So a night in the teens

meant that I brought home spawn coated with ice crystals.

I emailed the folks at

Field and Forest Products, and they responded quickly and soothingly. I

wasn't to worry --- as long as the spawn didn't freeze and thaw

repeatedly, it would be fine.

And, yes, I trusted them.

But I also recalled how much work and time we wasted on spawn that

didn't do anything two years ago. So I fell back on a technique I

recently learned in Organic Mushroom Farming and Mycoremediation.

Tradd Cotter recommends putting questionable spawn somewhere warm but

out of direct sunlight for a few days to see if the mycelium begins to

grow. Sure enough, after three days on top of the fridge, our plugs were

whiter than ever!

We'd planned to inoculate

our logs this week, but it looks like the weather isn't going to

cooperate. While I'd read previously that it's okay to inoculate logs as long as you're not going to see lows beneath about 18,

Field and Forest Products has a different guideline. They said to wait

until daytime highs are reliably hitting 40 Fahrenheit...which was the

case last year at this time, but not so much in 2015. (Actually, with

lows of -12 now forecast, we wouldn't be plugging logs this week by

anyone's guidelines.)

So the spawn is now

resting in the fridge, along with scionwood and maple sap. It sure is a

good thing I'm the head cook, or my homesteading spillover into the

kitchen might get on the kitchener's nerves....

The average reader may not know this, but my father is one of the founding editors of Sow's Ear Magazine, and his poetry has been published widely in other journals including Madison Review.

This winter, I got to enjoy the treat of looking through his body of

work in search of an ebook...or two, or three. And, in the process, I

discovered that his short stories pack the same punch as his poetry. In

fact, they remind me of a mixture between O. Henry and Wendell Berry,

and I suspect that many of you will enjoy the farm and small-town focus

of the four pieces I picked out to include in his debut work.

The average reader may not know this, but my father is one of the founding editors of Sow's Ear Magazine, and his poetry has been published widely in other journals including Madison Review.

This winter, I got to enjoy the treat of looking through his body of

work in search of an ebook...or two, or three. And, in the process, I

discovered that his short stories pack the same punch as his poetry. In

fact, they remind me of a mixture between O. Henry and Wendell Berry,

and I suspect that many of you will enjoy the farm and small-town focus

of the four pieces I picked out to include in his debut work.

But don't take my word for it! Sapling Grove Secrets

is free on Amazon today to give you a taste of my father's surprising

short stories. If you like what you read, you'll make both me and Daddy

eternally grateful if you take the time to leave a review. He's saving

up for his annual banana split, and a few good reviews on launch day

will make that treat much more likely to happen. Thanks in advance, and I

hope you enjoy these stories as much as I did!

It snowed enough today to

make the chickens and ducks choose a day in the coop instead of their

normal routine.

We had a hen who kept

escaping so we put her in a tractor for a week, but today seemed like

the day to move her back to the flock.

Spurred on by the permanent flower/herb beds I'm adding against the newly skirted sides of our trailer,

I decided to branch out into some additional herbs this year, and also

expand our planting of thyme. (Because there's never quite enough thyme

on our homestead!) While most perennial herbs are best purchased as

plants, I always like to test my green thumb against minuscule seeds, so

I filled a flat with chamomile, Greek oregano, thyme, fennel, lovage,

and poppies.

Of

these, the chamomile is a self-seeding annual and the middle four

should establish themselves as long-lived perennials. Poppies, on the

other hand, are typical annuals that are planted in our main garden each

year as a matter of course. So why include them in the herb flat?

Of

these, the chamomile is a self-seeding annual and the middle four

should establish themselves as long-lived perennials. Poppies, on the

other hand, are typical annuals that are planted in our main garden each

year as a matter of course. So why include them in the herb flat?

The trouble is that my planting calendar says to seed poppies outdoors now,

but our weather forecast has promised us at least a week below freezing

with an ultimate

low of -16 degrees Fahrenheit. Sure, I could just put off planting the

poppies the way I have the lettuce and will the early peas. But I often

end up thinning and resetting garden-seeded poppies, so I figured I'd

test them out as transplants instead this year.

Will the herbs be our

first garden sprouts of 2015? Not at all! Onions started in flats at the

beginning of February are beginning to send up green leaves at the

moment. A perfect visual tonic for a February cold spell!

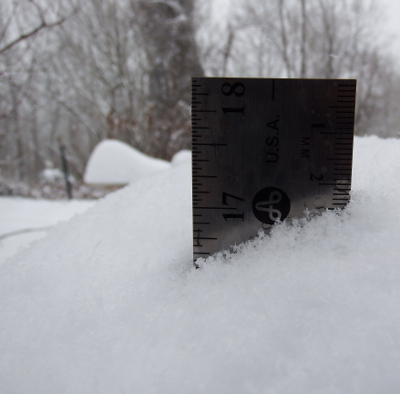

8,5 inches of snow is a bit

more than our previous snow

storm when the power went out for 10 days

Our main access road got plowed once today, but we decided to wait till

tomorrow for our regular trip to the Post Office.

"How about staying inside

today and taking it easy?" said the Red-shouldered Hawk. After seeing

how much effort it took to push my way through 8.5 inches of snow just

to do my morning chores, I decided the hawk was wise.

Indoors, my winter-mood-stabilization projects are greening up nicely. The Mars Seedless grape cuttings I started rooting six weeks ago are opening their leaves, as is the little fig tree  I

left inside for the winter. In contrast, Reliance grape cuttings

started at the same time are still dormant above ground, which actually

is a good thing --- the longer cuttings work on growing roots instead of leaves, the better.

I

left inside for the winter. In contrast, Reliance grape cuttings

started at the same time are still dormant above ground, which actually

is a good thing --- the longer cuttings work on growing roots instead of leaves, the better.

Of my Valentine's herb seeds,

all except the fennel and lovage have already sprouted! Shown here are

poppy seeds that I planted far too thickly. But I won't mind thinning

once they poke up their cotyledons --- a race to green which has been

roundly won by the chamomile seedlings.

When I got sick of

writing, I headed to the kitchen. How about some maple syrup snow ice

cream? 2 tablespoons of milk, two tablespoons of cream, 1.5 tablespoons

of maple syrup, and a big bowl of snow per serving. Delicious!

On February 11, Abigail suddenly started looking a lot less

pregnant. Maybe this is when the babies did the two-week pre-kidding

change of position? Either way, I'm pretty sure now that our doe is due

at the second possible date, which would be around March 4 if you go by

the 150 day gestational period of a standard-sized goat, or around

February 28 if you go by the 145 days that miniature goats average. (As a

semi-standard goat, I'd say Abigail might be due right in the middle.)

On February 11, Abigail suddenly started looking a lot less

pregnant. Maybe this is when the babies did the two-week pre-kidding

change of position? Either way, I'm pretty sure now that our doe is due

at the second possible date, which would be around March 4 if you go by

the 150 day gestational period of a standard-sized goat, or around

February 28 if you go by the 145 days that miniature goats average. (As a

semi-standard goat, I'd say Abigail might be due right in the middle.)

We're all enjoying the bit of breathing room from thinking there will be kids at any moment. Plus, by stocking up on hay and upgrading our manger, daily chores have been kept to a minimum. Less hay dropped to the ground means that our storage shed still  contains 7.5 of the 9 bales we put away near the end of January. We should definitely have plenty of hay to last until spring.

contains 7.5 of the 9 bales we put away near the end of January. We should definitely have plenty of hay to last until spring.

On the other hand, Abigail has

been a bit crankier lately, presumably because those unborn kids are

starting to weigh her down. She kicks Artemesia out of the shed unless

the weather's really bad in order to keep the doeling out of her hair.

"Why don't you go see if you can stand on that ice-covered barrel?" says

our pregnant doe. "Oh, goodie!" answered Artemesia. "That sounds like

loads of fun!"

We made it to town today

after being snowed in all week.

Might not have made it

without last year's

truck tire upgrade.

Although Tradd Cotter's Organic Mushroom Farming and Mycoremediation deserves a full lunchtime series...I already wrote one after listening to his inspiring lectures.

So, instead, I'll simply tell you that this beautifully illustrated

book is a must-read for anyone interested in homestead-scale mushroom

production. You'll learn more in-depth information about many of the

home-propagation techniques I've posted about previously, will be

inspired to try out mycoremediation

in your chicken coop, and much more. Then dive deeper into topics like

producing a slurry of morel spores and associated microbes to grow this

elusive species at home, or experiment with propagating shiitakes

without a lab by stacking thinly sliced logs separated by pieces of damp

cardboard.

Although Tradd Cotter's Organic Mushroom Farming and Mycoremediation deserves a full lunchtime series...I already wrote one after listening to his inspiring lectures.

So, instead, I'll simply tell you that this beautifully illustrated

book is a must-read for anyone interested in homestead-scale mushroom

production. You'll learn more in-depth information about many of the

home-propagation techniques I've posted about previously, will be

inspired to try out mycoremediation

in your chicken coop, and much more. Then dive deeper into topics like

producing a slurry of morel spores and associated microbes to grow this

elusive species at home, or experiment with propagating shiitakes

without a lab by stacking thinly sliced logs separated by pieces of damp

cardboard.

I really can't do Tradd's

book justice in a single post, so I'm merely going to sum up some

information on which mushroom species are best to grow in specific ways.

Tradd has a great section at the end of the book giving

species-by-species cultivation techniques for twenty-four types of

mushrooms, and he also breaks the species down into difficulty

categories. Based on that data, raw beginners who want to fruit their

mushrooms outdoors should consider black poplar mushrooms, wood ears,

reishi, brick tops, oysters and elm oysters, shiitakes, stropharia, and

turkey tails.

The book also clued me in to why my rafts

didn't do as well as I thought they would --- only reishi, nameko,

black poplar, brick top, and maitake are recommended for this type of

cultivation. Stumps,

similarly, are best for maitake, chicken of the woods, reishi, enoki,

oysters, and beefsteaks, with the tradeoff being that stumps take longer

to start to fruit than logs do, but that they then tend give you many

more years of harvests before petering out. Finally, if you want to grow mushrooms on cardboard, oysters, blewits, and stropharia are a good choice (at least during the vegetative stage).

Although I have a

tendency to focus on the easiest types of mushroom growing (namely

oysters and shiitakes seasonally fruiting on logs), Mark likes the idea

of faster production using sawdust, wood chips, coffee grounds and other

substances in containers. And Tradd succeeded in knocking out one of my

roadblocks to Mark's proposal, namely the constant use of throwaway

plastic bags. Instead, the mushroom guru recommends putting your growing

substrate in PVC pipes, nursery pots, or five-gallon buckets, all of

which can be modified with holes and sanitized in a 10% bleach-water

solution to allow reuse. Using these methods, you can see mushrooms as

soon as three weeks after inoculation when growing oysters on coffee

grounds --- too bad we don't drink that beverage or have a coffee shop

nearby!

In the end, Tradd's book is just as inspiring as his lectures were, but

the contents are much more meaty. I read the book slowly over the course

of a couple of months and recommend you do the same to enjoy the full

effect. Other mushroom books --- notably those by Paul Stamets --- will be a good supplement for the mushroom enthusiast, but Organic Mushroom Farming and Mycoremediation

has now risen to the top of my list of recommended mushroom books for

the homestead fungiphile. This book will be staying on my shelf for

years to come and I expect it will inspire many mushroom experiments.

Stay tuned for details as we try to propagate shiitakes using the log

method and perhaps grow some oyster mushrooms on old jeans.

We had our first power

failure of 2015 last night.

I guess it was caused by the

extreme low temperatures.

Nice of it to come back on

before lunch today.

At -22 Fahrenheit, we clearly see the difference between the addition

we built and the main trailer. Even though the corners aren't precisely

square in the former, we insulated it like mad and thus find it easy to

keep the internal temperature at a balmy 68 throughout arctic blasts.

In contrast, inside the trailer, I had to keep the wood stove running

full bore from 4:30 am on to maintain a temperature above 40. We sure

would add a lot more insulation to our main living space if our normal

weather regularly dropped down so far below 0.

Despite the momentary discomfort, though, my main concern with this cold snap is fruit trees. Will our Chicago Hardy fig simply die back to the ground

the way it did last year at -12, or will -22 be the death knell for

this Mediterranean fruit? Our current thick snow cover should protect

overwintering garlic and strawberries, but with dormant peach buds

starting to get damaged at -10 Fahrenheit, will we even see a bloom this

spring? I sure am glad I decided to wait at least until March to prune.

What kinds of Homesteading

chores do we do when buried by snow?

Anna has been working on a

new book and I've been building extra chicken waterers.

Great question, Karen

(especially since it gives me an excuse to include lots of snow photos

in this post)! The answer, of course, will depend on where you live and

on what kind of homestead you have. Presumably, if you homestead in

Alaska, you've worked out systems to deal with all of the cold-weather

issues, and -22 is just par for the course. So, for the sake of this

post, I'll assume that you live exactly where we do and homestead

exactly how we do.

I've spent a lot of time

over the past week wondering how homesteaders managed before the era of

10-day weather forecasts. Luckily, modern homesteaders have quite a long

heads-up and tend to know when cold spells are coming. As a result,

Mark and I prepared extensively before our current deep freeze:

- Splitting lots of firewood and stacking it on the porch for easy access.

- Pouring out our old stored drinking water and refilling the jugs, then filling a few buckets with wash water to sit on the kitchen floor for animal hydration and dishes.

(This assumes that your water, like ours, reliably freezes around 5

Fahrenheit, but causes no problems except requiring water rationing.)

Cooking lots of easily reheatable meals for simple human nutrition when the power goes out.

Cooking lots of easily reheatable meals for simple human nutrition when the power goes out.- Making sure the top layer of deep bedding in the goat barn and

chicken coop is very fresh since the animals won't want to go outside

and will be adding more manure than usual to the bedding. (Plus, fresh

bedding will keep them warmer during those frigid nights.)

- Filling the goat manger with hay up to the brim. (Remember, a belly full of hay is the best way to keep your goats warm.)

- Moving any inside plants a little further away from the window and/or closer to the fire. Lifting anything perishable (like sweet potatoes) that are sitting directly on the floor up onto a counter so they won't freeze.

If you messed up and

didn't prepare, some of these tasks can be done on sunny afternoons

during the deep freeze. But I'll assume they're not part of your daily

chores for the sake of this post.

Okay, so the mercury has plummeted --- what do you absolutely have to

do and how long does it take? Starting at dawn, I make two quick trips

into the outside on ultra-cold mornings. The first involves bringing a

bucket of warm water and their morning ration to the goats, and taking

in yesterday's bucket of ice. The second involves bringing a chicken waterer

full of warm water to the chickens, tossing a bit of food into their

coop, and then taking in any eggs. Actual time spent outside: two

5-minute sessions, with glove-warming lulls in between.

The second trip is

similar to the first and occurs right after lunch. Once again, everyone

gets warm water swapped out for the morning ice, and I've noticed that

this is when the goats go  crazy

drinking, having spent the morning filling up on hay. This is also when

I tend to gather our eggs on cold days --- some will have frozen solid

and cracked if the night got below 0, but often I'm able to nab them in

good condition as long as I get there by early afternoon. Finally, while

my boots are already on, I bring in enough firewood to make sure I can

keep the wood stove raging until the next morning, while Mark often

takes this time to bring in a bucket or two of water from the tank so we can catch up on dishes. Actual time spent outside: 20 minutes, with more dawdling to enjoy the snow.

crazy

drinking, having spent the morning filling up on hay. This is also when

I tend to gather our eggs on cold days --- some will have frozen solid

and cracked if the night got below 0, but often I'm able to nab them in

good condition as long as I get there by early afternoon. Finally, while

my boots are already on, I bring in enough firewood to make sure I can

keep the wood stove raging until the next morning, while Mark often

takes this time to bring in a bucket or two of water from the tank so we can catch up on dishes. Actual time spent outside: 20 minutes, with more dawdling to enjoy the snow.

Of course, I can't

survive on a mere half an hour of outside time per day, so as long as

the day gets above 20, I tend to trick Lucy into going out for a walk

with me in the afternoon. She and I take turns breaking trail through the thick snow, and we do all the things that don't actually need to be done. We carry in more hay to top up the manger, check the mail box, and brush snow off the sap-bucket roofs. Then we settle in for a well-deserved rest in front of the fire. Cold and snow are a great excuse to take it easy!

Where does Lucy stay when

it's cold?

She sometimes sleeps in her

house with the heated

kennel pad, but she

prefers the couch on our front porch most nights.

The other night when it got

down to -22 she slept on the floor inside with me for the first time.

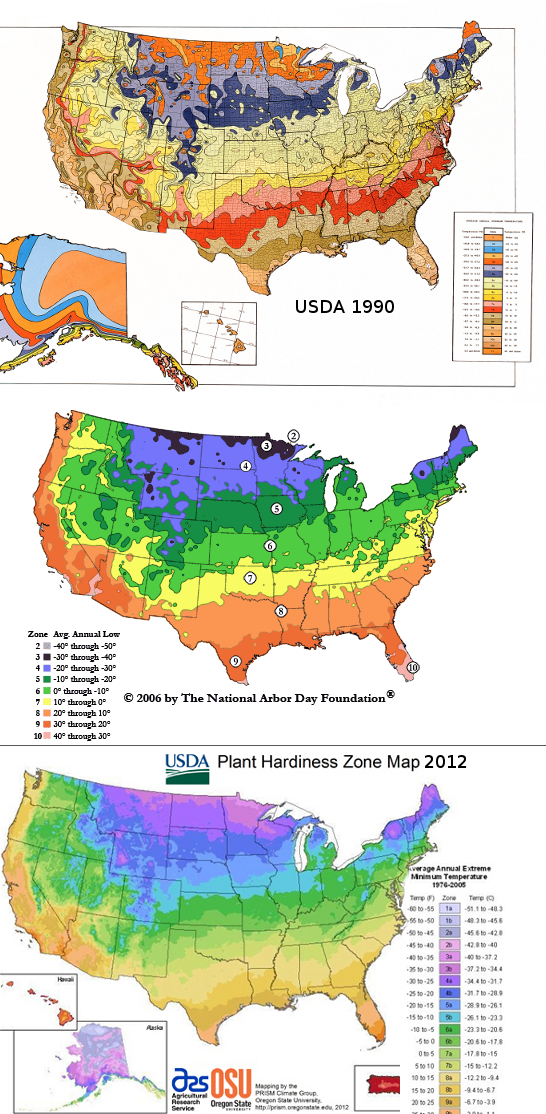

First the Arbor Day Foundation and then the USDA

came out with revised hardiness maps during the past decade, responding

to our changing climate. And in both cases, the maps promise that our

farm has moved to a warmer place. But can we take their recommendations

as gospel?

First the Arbor Day Foundation and then the USDA

came out with revised hardiness maps during the past decade, responding

to our changing climate. And in both cases, the maps promise that our

farm has moved to a warmer place. But can we take their recommendations

as gospel?

Depending on which map

you consider, our farm could have moved from zone 6a to zone 6b or

even to zone 7, with average annual extreme minimums of -10 to -5, -5 to 0,

and 0 to 5 respectively. However,

given the data of the last two years --- with annual minimums of -12

and -22 --- we might be smarter looking for plants that can handle zone

5b or even zone 4b, suggesting that our winters have become colder

rather than more mild. Granted, each zone's

annual minimums are supposed to be averages only, so it's somewhat

normal to exceed those minimums from time to time. Still, two years in a

row of deep-freeze conditions begins to look like a trend.

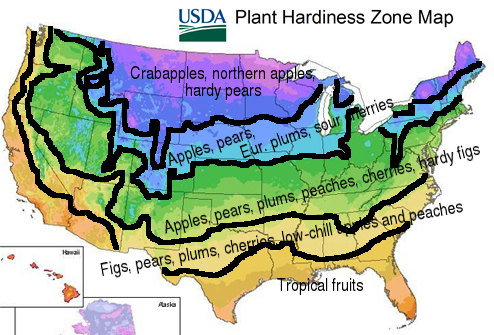

I posted before about Logsdon's recommendations for easy fruit tree species by zone,

with the map below summarizing the author's recommendations. If

we're moving a zone or two north, though, that would mean Japanese

plums, peaches, sweet cherries, and hardy figs all drop off the easy

list, leaving us with only apples, pears, European plums, and sour

cherries to savor. Similarly, blackberries, rabbiteye blueberries, and

hardy kiwis might all become dicey if the current trend toward arctic

blasts continues.

Which isn't to say that we won't be able to grow the dropped species at all. However, our sun trap

along the south face of the trailer might become prime real estate for

plants that have become a gamble from a climatic standpoint, and we

might eventually have to admit that peaches and figs in the main part of

the garden are doomed to failure.

Or maybe these brief cold spells won't have the same effect as a full

zone 5 winter. Only time will tell. But I do recommend keeping track of

your annual minimum temperatures and also perusing both of the new

hardiness-zone maps...especially if, like Karen B.,

you're planning to put in $928 worth of fruit trees. If nothing else,

stick to spring planting for questionable species, and plant your

charges in well-drained soil shielded from wind and in an area exposed

to the maximum amount of winter sun. Here's hoping all of your fruit

trees --- and mine too --- are surviving this long, cold winter.

We drilled our first mushroom

log of 2015 today.

It was just the right amount

of fun, outside labor to remind us that the snow will someday melt.

Oyster mushrooms are easy to propagate on the home scale using cardboard,

so I spent quite a few years pushing oysters. But the truth is that,

while Mark thinks oyster mushrooms are good, he thinks shiitakes are

great.

Unfortunately, shiitake mushroom spawn is less malleable than oysters

and won't thrive on cardboard. Enter the mini-mushroom-log propagation

experiment!

I call it an experiment, but the truth is that Tradd Cotter lists this as a viable technique in his book.

Granted, he uses logs that are much larger in diameter than the little

rounds I had Mark cut up and drill for me to plug Monday. But I'm hoping

that as long as I keep them moist, logs 8 inches long and 3.5 inches in

diameter will be sufficient for getting the shiitake mycelium running.

Eventually, we can stack multiple rounds together, allow the mycelium to

fuse, and thus have enough fungal body to produce a good mushroom

flush.

The

other thing I'm adding to give this experiment my own personal twist is

to bag each log loosely and let the spawn run through the logs at room

temperature. This is pure winter-doldrums thinking on my part --- I want

something to play with now!

The

other thing I'm adding to give this experiment my own personal twist is

to bag each log loosely and let the spawn run through the logs at room

temperature. This is pure winter-doldrums thinking on my part --- I want

something to play with now!

Once I start seeing

mycelium on the ends of the logs, I'll put a piece of wet cardboard on

top of each log and a fresh, unplugged log above that. Tradd promises

that the original spawn will pass through the cardboard and into the new

wood, expanding my planting without buying new plugs.

Total cost for this experiment: $3 worth of plugs, plus a bit of electricity to run the chainsaw and drill. I can only peer at my seedlings

so many times a day, so having three mushroom logs to pore over while

the ground is snow covered is worth the price of admission already.

How are the goats coping with

all this snow?

Anna has started adding some

dried kelp to their morning snacks after she noticed Abigail eating

most of the kelp

in the free choice bins.

They do bounce the tether

ball from time to time, but mostly look out the door and yearn for a

snow free pasture.

After a warm weekend that

began to thaw our accumulated snow, another couple of inches of snow

fell Tuesday and set back my belief that spring will actually come. The

solution? Ignore the outdoors and write!

I'm working on two

different projects at the moment, and am hoping to pick our readers'

hive mind about both. The first project is the sequel to Farmstead Feast: Winter, imaginatively titled Farmstead Feast: Spring.

Even though this is supposed to be a cookbook, spring is also the time

to be planting to ensure that you have something to cook with, so I was

considering throwing in a quick section on how much area we devote to

each vegetable variety and when we plant in order to feed the two of us

all year. But, of course, that information will be only moderately

useful to people with different diets and who live in different climates

than us. Would you find that a handy appendix at the end of the spring

cookbook, or should I stick to recipes?

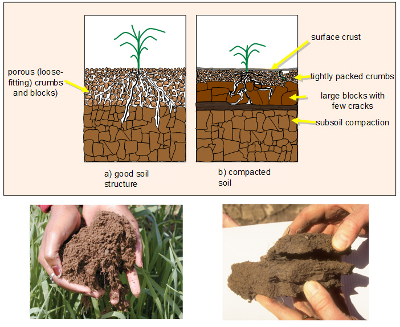

Second, I'm excited to announce that my fourth paperback,

The Ultimate Guide to Soil: A Gardener's Tips and Tricks for Organic, Nutrient-Rich, DIY Humus will be hitting bookstores in spring or summer 2016! I originally tried to sell Homegrown Humus

to my publisher, but they felt like cover crops were a little too much

of a niche subject. And when my editor came up with that alternative

title, I couldn't resist saying that I'd expand the book to include much

more than the topic I'd written about so far.

I'm planning on keeping The Ultimate Guide to Soil

much more hands-on than all of the soil books I've been perusing in

order to educate myself about the topic, so I'm devoting perhaps half of

the book to less mainstream methods home gardeners use to build the

soil. In addition to cover crops, I've planned sections on

remineralization, traditional compost, manure, bokashi, worm bins, black

soldier flies, compost tea, hugelkultur, biochar, humanure and urine,

leaf mould, and chop and drop. But I feel like there are more

soil-building techniques that I'm not thinking of at the moment. Maybe

you've got some ideas I should incorporate into the expanded book?

Please consider leaving me a comment and brightening this snowy day with

your ideas!

We ended up damaging our

truck battery with all the recent draining and jumping and had to

replace it with a new one..

The battery

disconnect switch is

working out nicely as long as I remember to turn the knob each time I

get home.

I give myself about a

week of wiggle room in my planting calendar, figuring that a few days

early or late won't impact the seedlings much and can allow me to fit

each planting into a much more favorable weather period. On the other

hand, I sometimes use that week of wiggle room for the sake of my own

sanity instead. For example, I planted a flat of tomatoes, borage, and

cabbage a little earlier than I'm supposed to as a way of keeping the

is-it-really-still-white-outside? blues away. Huckleberry was less than

impressed at the way I continue to fill up the sunniest spots with

seedling flats, but I reminded him that he's not really supposed to sit

on the table anyway.

The previous round of seedlings

are doing well, with only the fennel yet to sprout. Age might be a

factor, but it's also possible that the fennel are just taking longer

than the members of the mint family --- after all, my lovage seedlings

only started poking out of the ground a day or two ago.

I did go through and thin the faster sprouters, slaughtering hundreds of

baby seedlings in one fell swoop. I hadn't expected to have such

near-perfect germination rates!

I've also been pleased to

see absolutely no damping off, which could be due to a number of

factors. Honestly, I think the most relevant is the time of year and

weather --- my earliest plantings often tend to skip that problematic

fungus, presumably because it hasn't woken up in the wild yet. But it

can't hurt that I've been soaking the seedling flats in bleach water before planting,

and that I've been more careful about taking off the clear lids as soon

as I notice the first sign of germination. The latter technique lets

the surface of the soil dry out just enough to keep seedlings happy but

fungi out of the picture.

I've still got a flat of broccoli to plant, but I finally ran out of non-frozen stump dirt.

I'll probably break down and buy a bag of potting soil from the store,