archives for 11/2014

The first widespread

frost blanketed the farm Halloween morning. I've been harvesting the

broccoli and peas a bit at a time over the last month, but a low of 28

was enough to start damaging the remainder, so Mark and I spent the

afternoon bringing in the last of the early-fall harvest. Cabbages,

broccoli, peas, raspberries, and the last few figs soon lined the

kitchen counter, and then it was time to head back outside to protect

the late-fall bounty.

I've learned over the

years that it's not worth covering up tatsoi, tokyo bekana, and mustard.

These tender greens do okay in the early fall, but even with

frost-protection, they soon perish during November nights. So, instead, I

just erect quick hoops over the last planting of lettuce --- currently

in tender two-leaf stage --- and over most of our beds of kale. One kale

bed I'll leave uncovered to give us more variety in our greens harvests

before we begin delving into our covered beds in late November or early

December.

At

this time of year, I always get lots of question about quick hoops, and

I don't blame you. They're a beautiful sight in the garden, and tender

kale leaves deep into the winter are a beautiful sight in the kitchen!

All of your questions are answered in my 99-cent ebook Weekend Homesteader: October, and if you want to splurge, you can collect all of the Weekend Homesteader months in the paperback form. I hope that helps turn your garden into a year-round affair!

At

this time of year, I always get lots of question about quick hoops, and

I don't blame you. They're a beautiful sight in the garden, and tender

kale leaves deep into the winter are a beautiful sight in the kitchen!

All of your questions are answered in my 99-cent ebook Weekend Homesteader: October, and if you want to splurge, you can collect all of the Weekend Homesteader months in the paperback form. I hope that helps turn your garden into a year-round affair!

(Yes, the last shot is a totally unrelated cute goat photo. After all these weeks, you're still surprised?)

The good thing about letting

our ducks forage in the woods is the water.

What's not so good is when

they stay out all night and lay who knows where?

We'll herd them back in the

coop tonight before dark......at least that's the plan.

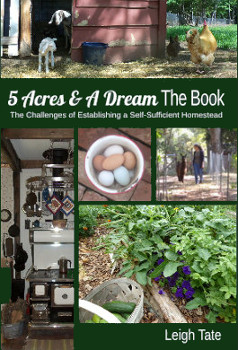

I first noticed Leigh Tate's 5 Acres & A Dream The Book when it popped up in the top 100 Sustainable Living books list on Amazon (where many of my books

reside on their good days). Once I realized the book was a

self-published paperback, I became even more intrigued because, while

self-published non-fiction ebooks are relatively easy to get into Amazon's top 100

lists, paperbacks tend to be trickier. In case you're curious

about reproducing Leigh's success, I suspect it boils down to:

I first noticed Leigh Tate's 5 Acres & A Dream The Book when it popped up in the top 100 Sustainable Living books list on Amazon (where many of my books

reside on their good days). Once I realized the book was a

self-published paperback, I became even more intrigued because, while

self-published non-fiction ebooks are relatively easy to get into Amazon's top 100

lists, paperbacks tend to be trickier. In case you're curious

about reproducing Leigh's success, I suspect it boils down to:

- An excellent title and cover.

- Choosing a black-and-white interior, which allowed her to include lots of great photos but to still price the book very reasonably.

- Quite a bit of promotion at launch (podcasts, a well-established blog with lots of fans, etc.)

- And, of course, an excellent book.

Okay, self-publishing tips

aside, I'm sure many of you are simply interested in the book

itself. If you enjoy our blog, chances are that 5 Acres & A Dream The Book

will be right up your alley. Leigh explains that her book isn't a

how to or a why to; it's simply the story of how she and her husband

found their farm and spent four years bringing the land to life.

Perhaps

the most powerful part of the book is the way Leigh records changes in

the couple's thought processes as they began

to homestead, transitions that I suspect are near-universal since Mark

and I worked

our way across many of the same hurdles during our early years here.

That's why I particularly recommend Leigh's book to folks who are still

in the dreaming stage or who have recently moved to a homestead. Chances

are, her book will help lower your own hurdles, in the process

making the obstacles look more familiar when the time comes for you to

leap

across.

As a more established

homesteader, I mostly read Leigh's book as a fun farm memoir, but I

definitely pored over the chapter on feeding animals with homegrown

products. The Tates experimented with planting field corn (a heavy

nitrogen feeder, but easy to grow and process), wheat (very tough to

process, but chickens will eat the grains out of the head), Ozark

Razorback cowpeas (can be fed to goats in the pod), and sunflowers (can

be fed in shells to goats). Since we're just getting started with

goats, Leigh's tips were very timely, especially since she's very

realistic about homestead-scale processing and storage.

As a more established

homesteader, I mostly read Leigh's book as a fun farm memoir, but I

definitely pored over the chapter on feeding animals with homegrown

products. The Tates experimented with planting field corn (a heavy

nitrogen feeder, but easy to grow and process), wheat (very tough to

process, but chickens will eat the grains out of the head), Ozark

Razorback cowpeas (can be fed to goats in the pod), and sunflowers (can

be fed in shells to goats). Since we're just getting started with

goats, Leigh's tips were very timely, especially since she's very

realistic about homestead-scale processing and storage.

Want to enjoy 5 Acres & a Dream The Book? You're in luck because one reader will win a copy just by entering the

giveaway below! If you don't win and want a free sampling of

Leigh's writing, head on over to her blog

for cute pig photos and much more. Leigh is also branching out

into ebooks, and her first two offerings, How to Preserve Eggs and How to Make a Buck Rag are now available on Amazon for 99 cents each. I

hope you enjoy the ebooks and paperback as much as I

did!

Some of our sprinklers are

cheap and don't have the ability to unscrew the hose without turning

the whole sprinkler or the hose.

A faucet

kink protector makes it

easy to disconnect hoses and eliminates that drastic kink that happens

when the hose bends down.

What

do you do if your dwarf apple tree is as tall as you want it to

get...and it keeps on growing? Whacking the top off a tree is seldom a

good idea since that type of pruning often prompts a tree to use up its

energy sending out lots of useless watersprouts. Enter a technique known as snaking.

What

do you do if your dwarf apple tree is as tall as you want it to

get...and it keeps on growing? Whacking the top off a tree is seldom a

good idea since that type of pruning often prompts a tree to use up its

energy sending out lots of useless watersprouts. Enter a technique known as snaking.

The photo to the right shows one of our high-density apple trees

that exceeded Mark's ability to easily reach the top this past summer.

As a result, I tied down all of the limbs at the top of the tree so they

became horizontal, instead of vertical, branches. Inevitably, one or

more of these limbs will bend upwards again next summer, at which point

I'll pull the top back down on itself accordion-style. This method of

slowing a tree's upward growth prevents the accumulation of

watersprouts, while also keeping a tree's fruits within easy reach.

The other alternative?

You can do as my older sister did and go out after dark as snow starts

to fall and climb your apple tree all by yourself in an effort to reach

the fruits at the very tip top. But I can't say I recommend it....

The carrots survived last

night's temperatures in the refrigerator

root cellar.

Experience tells us that when

it gets down in the teens we need the above supplemental heat to keep

our carrots from freezing.

A thermocube kicks on when it gets too cold

and shuts off when it gets above 45. The Kill a Watt meter is there to

tell us how much electricity it uses.

This week marks our one-month anniversary of having goats on the farm. Time to trim their hooves!

Hoof trimming was on my list of things I was uncertain about, which is why I opted to splurge on a special hoof-trimming tool rather than just using a pocket knife. Of course, now that I've trimmed hooves, I can see how a pocket knife could

work --- the part of the hoof you pare off is very easy to distinguish

from the not-to-be-cut area, and it's also quite soft. But clippers made

the operation very painless, and I'm glad we have them.

In the photos above, the picture on the left shows a hoof pre-trimming.

Notice that the edges stick out further than the center? All you have

to do is snip that bit off, a process which is simple if you do it

frequently (but can get tricky if you wait too long).

Once I figured out what I

was doing, front hooves were easy on both girls. Artemesia thought she

was being petted the whole time, so even our doeling's hind hooves

weren't bad, but Abigail didn't understand why something kept grabbing

her feet and not letting them go. In the end, Mark and I had to work

together to get Abigail's hind feet trimmed --- he corralled her and I

clipped.

Now that I've trained both of our girls to walk easily on a leash

and to do (mostly) as I say, it's time for the second round of training

--- milking prep. Abigail is (hopefully) pregnant (more on that later),

so Mark will be building a milking station shortly. Then I'll start

giving Abigail her treats (more on those later too) while up on the

milking station. That will give me an opportunity to get our doe used to

being manhandled, and should also make trimming her hind hooves easier.

As a side note, I recently learned that you can tell the age of a goat from looking at her teeth.

Abigail's previous owner wasn't sure how old she was, so I decided to

take advantage of already being on her bad list by prying open our doe's

jaw to take a peek. I had to look fast (so no photo), but the two big

teeth in the middle of six smaller teeth proved that our doe is around

1.5 years old --- the kids she had this past spring were almost

certainly her first. Hopefully she'll come through again in February or

March, at which point we'll start enjoying homegrown milk in addition to

cute goats.

I got the base of our new

goat milking stand finished today.

It's 20 inches high, 48

inches long and 22 inches wide.

Milking day is still far off,

but we want to start using it to trim their hooves.

Even though it was hard

to believe when I stripped down to a t-shirt five hours later, we had a

low of 21 on Sunday night. The killing frost was definitely enough to

nip our fig leaves and put the tree to sleep, which meant it was time to

protect our fig from winter cold.

Regular readers will

probably know all about our fig trees (which I talk about almost as much

as cute goats). But if you're new, here are some answers to obvious

questions:

- Some fig varieties are hardy to zone 6 (with winter protection).

- General tips on protecting figs through the winter.

- Protecting a small fig tree.

Result: This was not sufficient to help summer-planted figs survive

during the ultra-cold winter last year, but it worked in other years and

on older figs.

- My 2012 method of protecting a large fig tree. Result: The tarp on top slid to the side and the leaves matted down, but it worked pretty well otherwise.

- My 2013 method of protecting a large fig tree. Result: Last winter was awfully cold, so it's hard to tell whether this method was worse or not. It definitely wasn't better.

Okay,

now that you're all up to speed, it's time to protect that fig! I opted

to return to the 2012 method, figuring that more leaves around the base

of the plant will protect the sensitive junction of stem and root from

winter injury. Brian suggested stones around the base, which is a great

idea, but I never seem to have extra rocks to throw around. (It's a

momentous occasion when a new stone turns up in the garden.) Assuming we

don't have a repeat of last year's ultra-cold winter, and assuming that

I secured the tarp well enough, hopefully the three stems I kept will

produce an early crop (which we missed out on this year).

Okay,

now that you're all up to speed, it's time to protect that fig! I opted

to return to the 2012 method, figuring that more leaves around the base

of the plant will protect the sensitive junction of stem and root from

winter injury. Brian suggested stones around the base, which is a great

idea, but I never seem to have extra rocks to throw around. (It's a

momentous occasion when a new stone turns up in the garden.) Assuming we

don't have a repeat of last year's ultra-cold winter, and assuming that

I secured the tarp well enough, hopefully the three stems I kept will

produce an early crop (which we missed out on this year).

As I pruned, I was

excited to see that several of the small stems that had grown

horizontally out from the tree base had sprouted roots over the summer! I

snipped the rooted segments off and wrapped them in damp newspaper in

case any of our readers want to give Chicago Hardy figs a try. Enter the

giveaway using the widget below if you're interested (and be sure to

plan ahead for five cuttings that should be potted up and spend the

winter in a cool spot inside while they finish growing roots).

What do we do with the goats

on a rainy day like today?

Walk-em back to their Star

Plate barn.

Artemesia likes to lead the

way...I like to take pictures from the porch.

Back when we first paid for Abigail,

the owner seemed confident that she'd be able to breed her and let us

take home a pregnant goat. However, when the time came to pick up our

new addition, the owner seemed a little less sure. Yes, she thought

she'd bred Abigail a month previously, but she'd just gotten her buck

back from his visit to a friend's farm and the buck had acted very

interested in Abigail again. "So if she didn't get bred then, she got

bred now."

That left me with a lot

of question marks. If this was the same buck who had tried previously,

are we sure he did the job this time around? Is Abigail actually

pregnant? Enter the urine test.

Leigh posted

that one technique people think is pretty accurate is to add a little

less than half a teaspoon of goat urine to a cup of bleach. Based on the

amount of fizz you see, you can determine whether or not your goat is

pregnant. Extended fizz = knocked up. No fizz = she's not knocked up.

Since Abigail nearly always pees right before I take her out of the coop

in the morning and then again right after I bring her back in at night,

it was pretty easy to stick a container underneath and run a test.

Unfortunately, the results weren't what I was looking for --- no fizz.

Even after I poured a whole lot of urine into that bleach, the only

thing that happened is that the combined liquid turned a very dark

brown/yellow color.

So now I'm back at the buck-rag method of testing Abigail's status. When we got Artemesia,

that goat lady was kind enough to rub a rag (which I'd brought along

just in case) all over her buck, then I sealed the aromatic fabric in a

ziplock bag and forgot about it. This week, I finally started pulling

out the buck rag every day for Abigail to sniff. The idea is that, if

she's not pregnant, sometime

within the next three weeks our goat will be cycling and will suddenly

grow interested in eau de buck. Here's hoping she keeps telling me that

eating oat leaves is far more interesting than going on the rag!

We tethered our goats for

about an hour this afternoon for the first time.

No need to tether Artemesia

because she likes to be close to Abigail.

I've heard some goats can be

left unattended on a tether, but we're not comfortable trying it with

these girls.

In their prime, it seems like sacrilege to cook sugar-snap peas. But I allowed a few frosts to damage the last peas before we picked the vines bare last week,

which means that the peas we harvested were subprime. They were still

crunchy and sweet, but the pods had started to turn a bit fibrous and

the aesthetics were much reduced (as you can see to the right). Time to

saute the remaining vegetables with garlic and turn so-so fare into a

feast!

In their prime, it seems like sacrilege to cook sugar-snap peas. But I allowed a few frosts to damage the last peas before we picked the vines bare last week,

which means that the peas we harvested were subprime. They were still

crunchy and sweet, but the pods had started to turn a bit fibrous and

the aesthetics were much reduced (as you can see to the right). Time to

saute the remaining vegetables with garlic and turn so-so fare into a

feast!

(As a side note, this

recipe would be perfect for grocery-store peas. That's when we start

turning up our noses --- when our residual summer vegetables start to

taste like store-bought.)

There's really not much to this recipe, but here's an ingredients list to make it even easier:

- 2 cups of sugar snap peas

- about 2 tablespoons of peanut oil (or other high-heat oil)

- 2 smallish cloves of garlic, minced

- salt and pepper to taste

Excellent sugar-snap peas

can be used whole, but if yours are turning fibrous like ours were,

you'll want to string the pods as if they were beans. Otherwise, leave

the pods whole and drop them into a skillet full of a little hot oil.

Turn down the heat to medium-high, add the garlic, salt, and pepper, and

cook for about five minutes (stirring often) until the beans turn

bright green.

Voila! Deliciousness from

so-so produce! Now, with the last of the summer bounty down the gullet,

it's time to eat up all of those stockpiled cabbages.

We went over our neighbor's

for lunch today and got blocked by a fallen tree.

It was my first time seeing

his new Stihl chainsaw with a spring loaded quick start.

I was impressed with what

little effort it took to get the saw started. He says the guy he bought

it from says the only trouble they have with this type of mechanism is

people with muscle memory still wanting to pull like the old style

which can break the spring.

In Weekend Homesteader: October,

one of the projects I suggest is spending some time scavenging free

biomass for use on the garden. I barely touched on seaweed in that

chapter, including it only because I'd read that some people use seaweed

as mulch. But while Mark and I were at the beach last month, I decided to collect a bagful and bring it home as an experiment.

In Weekend Homesteader: October,

one of the projects I suggest is spending some time scavenging free

biomass for use on the garden. I barely touched on seaweed in that

chapter, including it only because I'd read that some people use seaweed

as mulch. But while Mark and I were at the beach last month, I decided to collect a bagful and bring it home as an experiment.

My first impulse, actually, was to feed the seaweed to the goats instead. After all, we offer kelp as a source of salt and micronutrients, so surely seaweed would be even better, right? A search of the internet found that some people do

feed seaweed to goats, but that you really have to find a source of

fresh, live seaweed and scrape it off the rocks (at which point I'd

start to worry about damaging the ecosystem). The seaweed that so

copiously washes up on our shores is instead dead and beginning to rot,

so isn't very healthy for our caprine friends.

But when applied to the

garden, the same seaweed shines. The bag I brought home went a long way,

mulching around a sage plant, a newly-transplanted grape, and a young

hardy kiwi. With a C:N

of 19:1, the mulch will probably rot down quickly, and I'd have to keep

an eye on salt levels if I used seaweed as a mulch on a regular basis.

But as it is, I suspect the top-dressed plants will get a boost in the

trace-mineral department and should grow quite well.

I'll keep you posted

about the results of my experiment, but in the meantime I'd love to hear

from those of you who live by the shore and presumably have plenty of

seaweed to throw at your gardens. Do you love it? Hate it? Somewhere in

between? Does it make up for painfully sandy, low-organic-matter soil?

Our kale seems to stop growing at this time of year, but it makes up for it by getting a little bit sweeter with each cold snap.

My

favorite college professor wasn't a "real" professor at all. The "real"

professor was her husband Tim, who taught ornithology and animal

behavior. But Tim and Janet were true partners, which I suspect is why

she opted to accept a job as assistant professor (if I've got my

terminology correct) at the same college where her husband taught. Or

perhaps Janet was just the smartest person I knew, who managed to create

a job doing exactly the things she loved --- leading field trips and

looking at birds --- within no administration to sully the mix.

My

favorite college professor wasn't a "real" professor at all. The "real"

professor was her husband Tim, who taught ornithology and animal

behavior. But Tim and Janet were true partners, which I suspect is why

she opted to accept a job as assistant professor (if I've got my

terminology correct) at the same college where her husband taught. Or

perhaps Janet was just the smartest person I knew, who managed to create

a job doing exactly the things she loved --- leading field trips and

looking at birds --- within no administration to sully the mix.

I liked birds, but I

loved Janet. She was exuberant and inquisitive, and she felt the same

awe toward the natural world that I did. Janet was just as mature anyone

else, but she was also unabashedly childlike. I remember walking

through the upstairs of her house one day and seeing stuffed animals

arranged across her bedspread, which Janet told me she set out every day

despite her children being grown and gone. The task made her happy, and

that was purpose enough.

Janet wore peasant

blouses and skirts and she loved to dance. She and Tim attended folk

dance classes with the students, where we all enjoyed taking part in her

favorite dance --- Levi Jackson's Rag. And like me, Janet couldn't stop

smiling because life was just so much fun.

Janet was the only

college professor who I considered to be a true friend. During my

student days, I'd drop by her office and watch enviously as she mixed

homemade granola with yogurt and a cut-up apple for lunch, and we'd talk

about our lives. Janet once told me that she didn't feel any different

than she had when she was my age, and, years later, I finally understand

what she meant. Looking back at the few snapshots I have from my

college days, I'm surprised to see that I looked so young since I still

feel so similar to that girl who loved to track down the source of a

scent in the woods and who followed Janet across the creek one spring

morning in hopes of capturing a deciduous magnolia in bloom.

Janet challenged me, but

in such a gentle way that I didn't realize I was being helped to grow

until I'd already filled the shoes she always assumed I could fit into.

Janet aided me by writing letters of recommendation, but more

importantly, she told me that of course I could remember how to ride a bike despite not having been on wheels in nearly a decade, of course I could lead bird walks as her T.A., and of course I could spend a year exploring foreign countries on my own. And she was always right.

Janet and her husband

eventually "graduated" and moved to their home in New Hampshire, where

they had spent their non-college years (and summers). I visited the

college only once after Janet left, and couldn't talk myself into going

back thereafter --- the beautiful campus simply felt empty without my

favorite professor to drop in on.

And, last week, the whole world became a little emptier when Janet

passed away. She had been sick for some time, and near the end, her son

sent out an email to all of her family and friends to alert us of the

situation. He said that Janet was too weak to visit with us in person,

but that she loved receiving emails, and that she especially loved

seeing photos and hearing about what was happening in our own lives. And

that was Janet to a T --- even at the bitter end, she wanted to hear

about our lives rather than to talk about her own.

Chickadees make a single high-pitched call that Janet was always able to identify because I could hear it and she

could not. But my teacher never bemoaned her failing hearing and

instead simply reveled in walking through the woods and catching a wood

duck perched on a slanted tree. And, in true Janet fashion, I choose not

to mourn her passing, and instead to let birds remind me of the one professor who changed my life. She was very much real, and she will be missed.

We had some trouble with

Abigail chasing her little sister today.

Letting them graze on some

oats seems to have fixed the problem for now.

Hopefully they'll be more

bonded by the time we run out of oats.

When I talked Mark into letting me experiment with ducks,

what interested me the most was the waterfowls' reputation for laying

well in the winter months even without lights in the coop. And I'm now

ready to say that their reputation is well deserved! We currently have

three point-of-lay pullets in the chicken department and five

similarly-aged ducks, and we receive about four eggs a day from the

latter (80% lay rate) and one egg a day (if we're lucky) from the former

(25% lay rate). Granted, this is without supplemental lighting in the chicken coop,

which would have increased our chicken-egg numbers, but that's

definitely a striking difference and a major mark in the pro-duck

column!

When I talked Mark into letting me experiment with ducks,

what interested me the most was the waterfowls' reputation for laying

well in the winter months even without lights in the coop. And I'm now

ready to say that their reputation is well deserved! We currently have

three point-of-lay pullets in the chicken department and five

similarly-aged ducks, and we receive about four eggs a day from the

latter (80% lay rate) and one egg a day (if we're lucky) from the former

(25% lay rate). Granted, this is without supplemental lighting in the chicken coop,

which would have increased our chicken-egg numbers, but that's

definitely a striking difference and a major mark in the pro-duck

column!

However, I've also

learned that not all eggs are created equal. Duck and chicken eggs look

similar but taste and cook quite differently. The first thing you'll

notice is how dirty duck eggs get if you don't harvest them from the

coop very promptly --- ducks can't hop up into raised nest boxes, so they'll walk all over their eggs after laying and coat them with filth.

This can be a health issue since washing can sometimes push bad

bacteria through the shell and into the eggs, so we usually give dirty

eggs to Lucy (who thinks all eggs are created equal).

Assuming you manage to

swoop up the clean eggs in time (which we're getting better at), the

next distinction comes when you crack a few eggs open. Duck eggshells

are harder, and they have a thicker membrane underneath, which means

that tiny fragments of shell are more likely to end up in your egg if

you're not very careful. I'm getting better at preventing this, but I

still spend quite a bit of time chasing tiny egg fragments through my

uncooked eggs each morning. Unfortunately, I haven't found any solution

for the very glutinous whites in the duck eggs, which tend to leave a

streak of goo on the counter every time I try to decant the filling from

the center of an uncooked egg.

Which

brings me to cooking. Here, I'm on the fence about which type of egg I

prefer. In cakes, duck eggs shine, resulting in a pastry that is so

perfect that it's nearly impossible to stop eating after one piece. (No,

despite what you think, that isn't

the bad part about cooking with duck eggs.) However, when scrambled,

I'm less of a fan. It's important to cook duck eggs more slowly and at a

lower heat than chicken eggs, but if you don't want to go over the edge

into burning, the result always feels just a tiny bit less cooked than

it should be. In a perfect world, I like to mix in at least 40% chicken

eggs when scrambling so that the result tastes "normal."

Which

brings me to cooking. Here, I'm on the fence about which type of egg I

prefer. In cakes, duck eggs shine, resulting in a pastry that is so

perfect that it's nearly impossible to stop eating after one piece. (No,

despite what you think, that isn't

the bad part about cooking with duck eggs.) However, when scrambled,

I'm less of a fan. It's important to cook duck eggs more slowly and at a

lower heat than chicken eggs, but if you don't want to go over the edge

into burning, the result always feels just a tiny bit less cooked than

it should be. In a perfect world, I like to mix in at least 40% chicken

eggs when scrambling so that the result tastes "normal."

I'd be curious from other duck-keepers. What do you feel are the advantages and disadvantages of duck eggs?

We tested our new goat

milking stand today.

It's close...but needs some

small adjustments to make it work.

When we went to pick up Artemesia, her previous owner

warned me: "You'll want to get in some good hay now." I looked at the

lady's dozen-plus full-sized goats and mentally rolled my eyes. Of

course I wouldn't need hay with just two little goats to feed on our ultra-weedy farm.

Five weeks later,

pickings are starting to get more slim. Part of the trouble is that I've

spoiled our goats to want only oat leaves and honeysuckle, on which

diet Abigail is actually putting on a bit of fat despite getting

basically no concentrated feed. (I do give our girls an overmature

summer squash or a bit of dried sweet corn or some butternut seeds every

other day or so --- whenever I think about it.) Artemesia still looks a

bit skinny, probably because she's going through a growth spurt, but it

appears that high-quality pasture is quite sufficient for a dried-off,

full-grown goat, even if she's (hopefully) pregnant.

But my snooty goats are

far less excited by low-quality pasture. Last week, I penned them into a

brushy area, hoping that after they ate the honeysuckle covering the

young trees, they might eat up the twigs of the trees underneath. No

such luck. Instead, my usually-quiet Abigail yelled at me all morning

until I relented and tethered her in the oat patch

for the afternoon. And while my oat supply also seemed pretty unlimited

a few weeks ago, our girls are starting to eat the lush greenery down

to the ground, which means their afternoon fill-up sessions are going to

be harder to come by in the near future.

Which is all a long way

of saying --- once the ATV gets fixed, we're going to have to get in

some hay. Drat! Oh well --- it's still inspiring to think that, if we

planned far enough in advance, we might be able to feed our goats on

farm-only feed pretty easily. After all, they gorged for over a month

without me spending a penny, so twelve months wouldn't be all that much

harder, right?

About

forty years ago, when visiting friends near Dungannon, Virginia, I

asked what fruit were under the big tree in their front yard. That

was my first taste of persimmons. They were close in flavor to a date, and very sweet. I loved them.

About

forty years ago, when visiting friends near Dungannon, Virginia, I

asked what fruit were under the big tree in their front yard. That

was my first taste of persimmons. They were close in flavor to a date, and very sweet. I loved them.

Once, when hiking in Maryland

at a reserve reservoir for the DC water supply, I passed through a

field of young persimmons and gorged myself on the sweet fruit.

So when I moved to our

acreage in South Carolina I planted a foot-tall sapling. This is

its second year bearing, and it is loaded.

But what to do with so much

fruit? According to my online search, the skin is inedible (though

when I eat it, I eat the whole fruit and spit out the seeds). The

source I read recommended peeling the persimmons and scraping the pulp

off the seeds. An hour of this got me 0.8 ounces (see photo

below). After a complete search online I found only one article on

separating the pulp from skin and seed. A Mother Earth News

article recommended using an old fashioned potato ricer.

I

rinsed a quart of the fruit in warm water and drained it. Then I

filled the bottom of the ricer with fruit and squeezed. Sure

enough, pulp oozed out of its holes. I quickly learned that a

steady but gentle pressure was needed and that three squeezes would get

all that would come. Between squeezes I stirred the fruit with a

table knife and poked at any that hadn't split open.

I

rinsed a quart of the fruit in warm water and drained it. Then I

filled the bottom of the ricer with fruit and squeezed. Sure

enough, pulp oozed out of its holes. I quickly learned that a

steady but gentle pressure was needed and that three squeezes would get

all that would come. Between squeezes I stirred the fruit with a

table knife and poked at any that hadn't split open.

The result was eight ounces

of fruit in an hour. If you notice in the picture, the fruit color

in the earlier attempt is lighter and clearer. That is because

the machine method will render some stem and seed pieces. These

don't affect the flavor.

As I was finishing, I looked

in the corner at the box with our steam juicer and a little light bulb

went off. It did a wonderful job juicing grapes. Why not

persimmons?

We cut down a small tree

loaded with honeysuckle today.

It might be enough to get the

goats through another day or two.

The Oregon

battery powered chainsaw

continues to be a perfect fit for small jobs like this.

I

enjoy spending chilly mornings writing in front of a fire, and once I

finish up my stockpiled projects from earlier in the year, the question

becomes --- what to write next? I probably won't start any new projects

until the first of next year since I'm currently cleaning up old covers

(what do you think of Growing into a Farm version 3?), finishing the expanded manuscript of Trailersteading

for my publisher, and generally getting all of the things I let slide

during the summer back into shape. But it's good to start ruminating,

and I'd love your opinion on which of these books you'd most like to

read:

I

enjoy spending chilly mornings writing in front of a fire, and once I

finish up my stockpiled projects from earlier in the year, the question

becomes --- what to write next? I probably won't start any new projects

until the first of next year since I'm currently cleaning up old covers

(what do you think of Growing into a Farm version 3?), finishing the expanded manuscript of Trailersteading

for my publisher, and generally getting all of the things I let slide

during the summer back into shape. But it's good to start ruminating,

and I'd love your opinion on which of these books you'd most like to

read:

Eating the Working Chicken expansion --- The short ebook that currently goes by this name

is very basic, with concise butchering advise and a small amount on

cooking. But since writing the first edition, I've learned at least half

a dozen delicious ways to cook tough, old hens without ending up

gnawing for hours on stringy meat. So an update seems to be in order.

Gardening in a Wet Climate

--- This new ebook would be just what the title suggests. We've

definitely learned a lot about how to make gardens thrive when it rains

all the time and when your soil is so waterlogged you have to garden in

knee-boots, so I'd love to share the results of our experiments. But

perhaps this is too much of a niche subject since most people probably

didn't get seven inches of rain during the first two weeks of October?

Permaculture Cliff Notes --- I give away Best Books For Homesteaders to anyone who joins my email list.

But I was thinking of adding in page-length summaries of each

recommended title so you could, conceivably, get quite a good education

in just an hour of reading.

Keeping Deer out of the Garden

--- Mark and I have certainly experimented with this topic like mad

over the last eight years, and I have a lot of permaculture tips to

share on the topic. However, my advice is pretty non-mainstream --- I

think that working with deer's behavior is the long-term solution rather

than purchasing repellents. So people in search of a quick fix might be

disappointed.

Even though I sell my

ebooks on the open market, my blog readers are the ones I really write

for. So I'm putting it up for suggestions --- does one of these ebooks

speak to you more than others? Or is there something else you'd really

like to hear about instead? Please leave a comment and let me know!

We finally found a local

mechanic that can fix our rear

prop shaft.

The operation requires some

tools and experience I don't have.

With any luck we'll be able

to haul in some hay for the goats next week.

I

probably should have done this last month, but I took a few minutes

this week to close up our hives for winter. Hive winterization involves

adding a bottom board beneath the screened bottom and removing any boxes

that aren't currently in use, with the purpose of both tasks being to

make the hive easier to heat over the winter. Many people do the same

thing in their domiciles, in fact --- if you really only use your

bedroom and kitchen in the winter, why pay to heat the whole house?

I

probably should have done this last month, but I took a few minutes

this week to close up our hives for winter. Hive winterization involves

adding a bottom board beneath the screened bottom and removing any boxes

that aren't currently in use, with the purpose of both tasks being to

make the hive easier to heat over the winter. Many people do the same

thing in their domiciles, in fact --- if you really only use your

bedroom and kitchen in the winter, why pay to heat the whole house?

Unfortunately (but unsurprisingly) I found the daughter hive empty when I went to remove the bottom box. Six weeks ago, I could tell that this hive was ailing, and even though though I tried to double down on feeding them, the bees didn't seem very interested in

sucking up sugar water. In retrospect, I suspect the colony I was trying

to feed was already gone at that point, with bees from our other hive

flying over to suck down the sweet  moisture. My guess is based on the fact that this hive didn't actually die out --- like

the one we treated with powdered sugar last fall, the entire colony

simply absconded, leaving only half a dozen dead bees behind.

moisture. My guess is based on the fact that this hive didn't actually die out --- like

the one we treated with powdered sugar last fall, the entire colony

simply absconded, leaving only half a dozen dead bees behind.

So we're back down to one

hive heading into the winter, and even that colony felt a bit light

when I lifted the two top boxes to take out the cleaned-out box

underneath. I definitely don't seem very good at keeping bees alive

without chemicals and copious sugar water (and I'm unwilling to resort

to the methods other beekeepers use to keep their hives humming). But

we've got another trick up our sleeve for next year, so I'm not giving

up!

Are we ready for temperatures

40 degrees lower than normal?

I think so after some last

minute Winterizing this afternoon.

With the snow starting to

fall, I let our girls top off their bellies with oat leaves Thursday

afternoon, then put them to bed early with a sunflower-seed head.

As she's gotten bigger,

Artemesia has grown an independent streak. She now has a bad habit of

lagging behind for just...one...more...leaf. But our doeling soon

gallops to catch up.

"Gee, I almost missed the treat?!"

Both goats enjoy eating

the sunflower-seed head right down to the stem, but Artemesia isn't

nearly as good at it. Our little doeling always takes one big bite that

doesn't quite fit in her mouth, then she spends several minutes trying

to wrestle the seeds into her throat. Meanwhile, Abigail takes little

bites --- gulp, gulp, gulp, down the gullet --- and ends up consuming

85% of the head. No wonder our doe is getting fat while our doeling just

holds her ground.

Sorry for the dark pictures, but hopefully you enjoyed walking the goats back to the coop with me!

I've

written a lot already about how much our goats love oat leaves. Always a

softy, I've taken to tethering our girls in the garden for half an hour

or an hour every afternoon to fill them to bursting, during which time I

mostly monitor them (but also cover any strawberry plants with a bit of

plastic trellis material for an added layer of protection). But as our

oat stores dwindle, I decided to try our goats on another winter cover crop --- oilseed radishes.

I've

written a lot already about how much our goats love oat leaves. Always a

softy, I've taken to tethering our girls in the garden for half an hour

or an hour every afternoon to fill them to bursting, during which time I

mostly monitor them (but also cover any strawberry plants with a bit of

plastic trellis material for an added layer of protection). But as our

oat stores dwindle, I decided to try our goats on another winter cover crop --- oilseed radishes.

Actually, I'd experimented with this offering before, including some oilseed beds into various enclosures while letting the goats eat the honeysuckle off the side of the barn.

Interestingly, our girls seemed totally uninterested in what were then

beautiful green leaves...until we had a killing frost. I suspect the

oilseed radishes changed at that point, perhaps the way carrots and kale

both get sweeter after a frost. Guesswork aside, the only thing I know

definitively is that our girls ate the oilseed radish plants to the

ground from that point on.

Since determining that our goats do

enjoy frost-bitten oilseed radishes, I've pulled up a few plants for

them now and then when no radishes are within their enclosures. But my

offerings were often abandoned, presumably because it's a lot harder for

a goat to break off bite-size pieces when a plant isn't anchored firmly

in the ground.

So, Friday, I decided to chop up the roots and see if that made the radishes more palatable. Did it ever! Artemesia got sick of radishes before too long, but Abigail ate about three big plants' worth.

The photo above shows me starting to train Abigail to her milking stand,

the tray of which was full of radish roots plus a little bit of corn.

Our doe still doesn't always get on the stand immediately, but she did

jump up one day without me even asking because she wanted to look in

the trough for food. As with most things, I think training Abigail to

the milking stand will come easy --- goats are definitely the smartest

livestock we've so far had on our farm. (Which means we have to be

ultra-careful not to let them learn bad habits!)

Talk

about a vegetable with an undeserved bad rap. In Canada they

changed its name to canola. If you want a recipe you need to look

up broccoli raab or rapini. It's one of my standard, easy-to-grow

winter vegetables. A ten-by-ten foot patch provides a never ending

supply of fresh and healthy greens.

Talk

about a vegetable with an undeserved bad rap. In Canada they

changed its name to canola. If you want a recipe you need to look

up broccoli raab or rapini. It's one of my standard, easy-to-grow

winter vegetables. A ten-by-ten foot patch provides a never ending

supply of fresh and healthy greens.

Yesterday in the dentist's

waiting room, a cooking show was on TV with the sound muted. I

watched the cook put greens on a cookie sheet and into the oven.

After the commercial when it came out the words "oven roasted rapini"

flashed on the screen. I was planning on sauteeing mixed greens

for a supper side dish, but decided to try this instead.

First I soaked the picked greens in cold water and drained them.

Then I cut them in two-or-three-inch-long sections.

A coating of olive oil with

salt preceded putting them on baking sheets and placing in a 350 degree

oven. A stir or two, then, fifteen minutes later--ready to eat

along with crock-pot navy beans cooked with chopped onions and green

pepper.

Delicious.

(Note from Anna: For those of you who aren't in the know, Errol is my

father, who homesteads in South Carolina and is the primary author of Low-Cost Sunroom. I'm tempted to nitpick about his use of the

term "rapini," which I understand to mean the broccoli-like flower buds

from various types of crucifers. But maybe he's right and I'm wrong and the whole plant can be called rapini? It definitely sounds better than rape....)

We hiked what we thought was

a fresh battery to the truck today.

Now we think something is

wrong with our ancient

trickle charger.

We've enjoyed such a

nice, gentle fall...but all good things must come to an end. When I woke

to a low of 12 Saturday morning, I realized that I'd forgotten some of

the winter tasks that I should probably have been more on top of. Yep,

our water line had frozen

(as it generally does in extreme cold weather...especially if I forget

to put insulation back around the summer access points), and I hadn't

filled up any backup water sources. So I had to steal half of the

contents of Huckleberry's water bucket for the goats, which prompted our

grumpy cat to stalk outside in a snit and then bring a junco back to

lay across the kitchen floor. I picked up the bird, thinking it was

dead, opened the back door to toss the critter out...and Huckleberry's

prey lifted off from my hands and flew away, stunned but unharmed by our

cat's attention-getting move.

So winter is here at

last! Happily, I realized that twelve doesn't really feel all that cold

when you've gotten used to mid-fifties inside the trailer. And now maybe

those last few leaves will drop off our baby apple trees so I can enjoy one of my favorite seasons --- fall perennial planting! After the ground thaws, of course.

A short video showing what's involved in putting up a quick hoop.

"I was wondering whether this feels like it might be a longer winter

than normal and if the woodshed was full enough to make it through to

the warmer weather of spring? In our two years having a woodstove at our

cabin, we are still learning just how much wood we will need to keep us

warm during the cold months.

"I was wondering whether this feels like it might be a longer winter

than normal and if the woodshed was full enough to make it through to

the warmer weather of spring? In our two years having a woodstove at our

cabin, we are still learning just how much wood we will need to keep us

warm during the cold months.

Also - I was curious if you have to deal with mice in the trailer?

Our cabin was invaded recently and I was looking for more good ideas to

make them less inclined to visit."

--- Karen B.

Two great questions, Karen!

As for the wood --- we never seem to have quite enough, but we manage.

In order to really get ahead on firewood, we'd need to change our system

so that we can stock up on wood during the winter that comes a year

before we plan to burn it,

since that's a season when our lives are less busy. But since I need to

be able to get to last year's firewood during the winter, we instead

empty the woodshed out and then fill it back up. In the end, that method

means that cutting firewood has to compete with the garden --- I'll bet

you can guess which one wins! To make up for our slacker habits, I tend

to earmark a standing dead tree

or two for spring firewood since the dry wood can often be burned soon

after cutting, which generally ekes us through late February, March, and

April.

The mouse issue is more

interesting to me because we're finally starting to figure it out. Every

fall, the local mouse population does

tend to invade our trailer, and even though Huckleberry catches an

occasional mouse, he's not our first line of defense. (Our other cat,

Strider, is a lover, not a fighter.) We've learned the hard way that

it's essential to be hyper vigilant at this time of year --- at the

first sound of nibbling in the walls or sight of mouse droppings on the

counter, we pull out the traps with a vengeance. Mark talked me into

buying this super fancy trap

years ago, and it did work for a little while (as you can see above),

but then the scent of death built up and the mice started to avoid it.

Now, we tend to use cheaper traps, which we can reuse a few times until

they lose efficacy and then toss. Our favorite trap is currently one a lot like this.

When trapping mice, you'll

want to put the trap where you think a mouse might run. Mice are

skittish little varmints, so they're unlikely to head to your bait in

the middle of the floor; instead, set your trap against a wall in an

out-of-the-way spot (but near where you saw their signs). We sometimes

bait with peanut butter, but cheese has a higher success rate,

especially cheddar. I probably don't need to say it, but don't bother

with live traps --- moving animals around is never a good idea, and

unless you live way out in the country, the mouse is likely to head into

another home after you release it, where it will get killed anyway.

Another factor to keep in

mind is sealing away anything that a mouse might like. Food is obvious,

but clothing and toilet paper are also in great demand for bedding. An

average bureau doesn't really keep a mouse out, I've found, so

rubbermaid bins can sometimes be better. Barring that, I try to at least

go through each drawer on occasion so I don't miss a mouse nest being

built. If you have storage areas inside your home, don't pile things up

in such a manner that a cat can't get into the center to hunt, and do

check those little-used areas at intervals as well. Catching the first

few mice who drop by in the fall is only of middling difficulty, but if

you let them breed and have fifty mice to hunt down, your work will

really be cut out for you!

I hope that helps, and I'm

glad you're being proactive. In the city, roaches are probably the most

common vermin, but in the country, it's all about beating the mice. And

as cruel as it seems to kill them off in the fall, you'll be rewarded by

a winter sitting by the fire without the sound of nibbling in the

walls.

We got the first part of our

goat manger done today.

The access slots will be 2

inches wide and 4 inches tall.

Ever since we got goats, I've been building them a new "tractor"

every day out of cattle panels. At first, that effort seemed very

worthwhile, since I was moving the girls around to eat all of the

honeysuckle off our fencelines and barn. But once I ran out of easy

honeysuckle buffets, it seemed like twenty minutes of labor for half a

belly of so-so food might not be as efficient a use of my time.

Monday

afternoon, I decided to let the girls run out in the woods...and boy

did they love it! If I don't have to ensure that the honeysuckle is all

concentrated in one place, there's still quite a bit out there, maybe a

few weeks' worth within a stone's throw of the coop. The question is ---

will I regret letting our goats run wild outside our core homestead?

Monday

afternoon, I decided to let the girls run out in the woods...and boy

did they love it! If I don't have to ensure that the honeysuckle is all

concentrated in one place, there's still quite a bit out there, maybe a

few weeks' worth within a stone's throw of the coop. The question is ---

will I regret letting our goats run wild outside our core homestead?

The worst-case scenario

is that a trespassing hunter will think Abigail is a deer, or that the

pack of wild dogs who roam through our woods will get past Lucy's

defenses and try to eat Artemesia up. More likely (but only slightly

less heart-wrenching) is the possibility that our girls will hop right

over the chicken-wire fences that surround our core homestead and start

chowing down on apple-tree twigs.

To be entirely honest,

our goats have gotten out and ended up free in the yard a few times

already. So far, they seem much more interested in oat leaves than in

apple trees, so I'm willing to risk a few nibbles as long as I'm right

here to catch them in the act. Chances are good that if Artemesia got

loose in the garden, she'd just end up on the porch, as she has before,

asking why we haven't come out to play, so I'll try letting them out

into the woods for longer today. Here's hoping our goats aren't too

capricious and that they behave!

Abigail discovered how to

escape from one of her pastures today.

We think she used an edge on

the other side of this stump to climb up and over.

Trimming the stump and adding

a few pieces of wood might be enough to keep her in.

We enjoyed our first and possibly only roast brussels sprouts of the season Tuesday, the combination of a new variety and an extremely wet fall meaning that the plants blighted instead of thrived.

The experience made me think about how frequently home gardeners give

up on a crop because of a single failure, when what they really should

have gotten out of the experience was an impulse to figure out what made

their plants refuse to grow.

For example, I often hear

from folks who think carrots aren't worth growing, while for us the

tasty roots are an easy crop. Well, an easy crop as long as I pay

attention and make sure their seeds germinate during the summer heat.

And as long as I locate the root vegetables in loose, humus-rich soil. So, not really

an easy crop, but easy once you figure out what factors of your unique

site are standing in the way of getting a stellar carrot crop.

Now that the cold weather

has truly set in and most of you have nothing left to plant for the

year, why not spend a few hours thinking back over your garden past?

When you look at all of those luscious-looking pictures in the seed

catalogs this winter, try to ignore the pretty photos and tantalizing

descriptions. Instead, seek out the less sensational but more important

notes on which blights each variety is resistant to and how well they do

in other difficult situations that your garden will throw at them in

the year to come.

And, as a reward, next year your garden will grow twice as well!

Riding in our backseat lately is a rough equivalent to an old fashion hay ride.

I

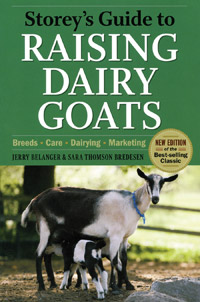

know that some weeks it seems like all I do is talk about goats and

books. So why not shake it up...and talk about goat books?!

I

know that some weeks it seems like all I do is talk about goats and

books. So why not shake it up...and talk about goat books?!

When I first started researching goats, my first stop was Storey's Guide to Raising Dairy Goats.

The Storey series is usually a safe bet for encyclopedia-style

information on livestock combined with beautiful pictures, and this book

was no different

(although a little less in-depth than some). If you've never met a goat

before and are only going to get one book, this is probably the one to

buy.

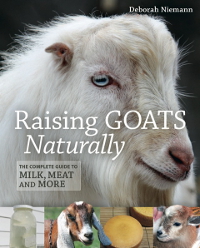

But once I finished that beginner guide...I still felt like a beginner. So I moved on to Raising Goats Naturally.

Deborah Niemann's book is also an introduction to goat care, but it's

written in a more chatty, first-person fashion (a lot like my own

books), which I suspect turns some people away. However, since I'm aware

that all one-author books inevitably share that person's biases and  knowledge

gaps, I enjoyed the honesty of Niemann's book and definitely pulled out

some interesting tidbits that weren't covered in the Storey guide.

Specifically, I learned that you should always breed miniature or

partially miniature goats with bucks that are as small as the doe or

smaller so that you don't have to worry about extra-large kids causing

problems coming out. This and other factoids probably seem obvious to

many of you, but I sucked them up happily, glad to have someone else's

experiences to help me avoid beginner mistakes.

knowledge

gaps, I enjoyed the honesty of Niemann's book and definitely pulled out

some interesting tidbits that weren't covered in the Storey guide.

Specifically, I learned that you should always breed miniature or

partially miniature goats with bucks that are as small as the doe or

smaller so that you don't have to worry about extra-large kids causing

problems coming out. This and other factoids probably seem obvious to

many of you, but I sucked them up happily, glad to have someone else's

experiences to help me avoid beginner mistakes.

By the time I finished

Niemann's book, I was starting to feel more like an accomplished

goatkeeper...but I still didn't have goats. Since I couldn't move up our

goat-arrival date, I settled on getting another book instead, this time

Natural Goat Care by Pat Coleby. I'll admit up front that our two spoiled darlings arrived when I was only a  quarter

of the way through Coleby's book and my attention quickly turned to

real, live goats, so I've still got a lot left to read, but I think that

this book makes a very good addition to the beginning goatkeeper's

knowledge-base...as long as you take the contents with a grain of salt.

Coleby veers a little too far toward the personal-experience/no-science

side for my tastes in a few spots, but most of her book walks a more

middle ground. And she presents intriguing suggestions about how the

prehistory of goats impacts their current needs, explaining that goats'

tendency to browse on tree leaves means that the animals can develop

mineral deficiencies when dining primarily on short-rooted grasses in

human-build pastures. In turn, Coleby asserts that those cravings are

what spur goats to break out of our pastures...which may be wishful

thinking, but is worth considering.

quarter

of the way through Coleby's book and my attention quickly turned to

real, live goats, so I've still got a lot left to read, but I think that

this book makes a very good addition to the beginning goatkeeper's

knowledge-base...as long as you take the contents with a grain of salt.

Coleby veers a little too far toward the personal-experience/no-science

side for my tastes in a few spots, but most of her book walks a more

middle ground. And she presents intriguing suggestions about how the

prehistory of goats impacts their current needs, explaining that goats'

tendency to browse on tree leaves means that the animals can develop

mineral deficiencies when dining primarily on short-rooted grasses in

human-build pastures. In turn, Coleby asserts that those cravings are

what spur goats to break out of our pastures...which may be wishful

thinking, but is worth considering.

I'd be curious to hear

from our readers. Which other goat books do you feel help beginners turn

into permaculture goat herders? Did I miss an obvious introductory text

from my lineup?

Of course the goats wanted to

be on top of the new manger.

The thin plywood lid was

collapsing when they stood on it, which could be a safety issue if they

fall the wrong way.

Adding some 2x4's for support

makes it more standable.

There's something

psychologically colder about nights that get down into the single

digits. Or maybe it's not completely psychological. Gates freeze shut,

my hands ache when I go out to do my morning chores, and the uncovered

winter crops begin to die back.

Last year at this time,

we enjoyed a similar cold spell, but the lowest low in November 2013 was

15. No wonder I ran through the firewood I had alloted for November

2014 by the middle of this month and have already started into

December's wood.

Everyone else on the farm

is glad that we're due to enjoy a bit more fall weather this coming

week as the current Arctic burst goes back where it belongs. But Lucy

loves the cold, so she might be sad to see it go. Don't worry, Lucy ---

there are many more frosty mornings ahead!

We transplanted some apple

trees this afternoon.

Honey Crisp will be in the

middle of Mr Winesap and Ms Red Delicious.

So, my goats-in-the-woods experiment

lasted all of about two hours. I let the girls loose, settled down to

write...and soon heard Artemesia yelling at the top of her lungs.

Abigail had circled around to the part of our boundary that has the

lowest fence and had hopped right over, but our doeling's stubby little

legs didn't allow her to follow. I guess it's a good thing that

Artemesia is part Nubian since there was no missing her anguished yells

as she was left  behind.

Or maybe our doeling was just telling on her big sister? Either way, I

pulled Abigail out of the garden before she could do any damage, then I

stuffed both goats back into the pasture with the honeysuckle trees shown above.

behind.

Or maybe our doeling was just telling on her big sister? Either way, I

pulled Abigail out of the garden before she could do any damage, then I

stuffed both goats back into the pasture with the honeysuckle trees shown above.

For experiment number

two, I decided to open the door on the far side of the starplate coop,

meaning that our goats would have to walk through some rough terrain to

circle around the fenced pastures and reach our core homestead. Sure

enough, when I came back from walking Lucy, I discovered that our goats

had decided to explore in the opposite direction. But Artemesia was

yelling again, and I got worried (even though our doeling sometimes just

likes to yell) and went to see what was up. No one was in trouble, but

both goats followed me right home, negating that experiment.

Next, I decided to try tethering Abigail

on the far side of the starplate coop. I figured that Artemesia would

stay close to her companion, and that everyone would be happy. So when I

heard non-Nubian yelling I guessed that our doe must have gotten her

chain hung up. Nope. Artemesia had decided to wander far afield in

search of honeysuckle, and her big sister was having a fit at being left

alone. So, once again, I stuffed the girls back into the pasture for

safe keeping. I guess they're stuck eating hay

now except when I take them out on monitored walks...unless I come up

with another supposedly bright technique for letting them run wild in

the woods.

I was a little worried about having the goats grazing on oats so close to our new apple trees, but it seems like they're not interested in anything with bark yet.

Although it's a little premature to count our two-year-old high-density apple experiment

as a success (since frost nipped all of the blooms this spring), I'm

feeling very positive about the system. Planting the apple trees close

together allows me to try out lots of different varieties, which in turn

makes it easy to select varieties that resist cedar apple rust and our other local bugaboos. The high-density row doesn't take up much precious garden space, and the summer pruning (although frequent) is simple and fun. No wonder Mark and I chose to plant two more high-density apple rows this fall!

Although it's a little premature to count our two-year-old high-density apple experiment

as a success (since frost nipped all of the blooms this spring), I'm

feeling very positive about the system. Planting the apple trees close

together allows me to try out lots of different varieties, which in turn

makes it easy to select varieties that resist cedar apple rust and our other local bugaboos. The high-density row doesn't take up much precious garden space, and the summer pruning (although frequent) is simple and fun. No wonder Mark and I chose to plant two more high-density apple rows this fall!

With this second

planting, I'm experimenting in three different directions. Two years

ago, I mostly chose trees grafted onto Bud 9, M26, and Geneva 11

rootstock, meaning that the trees are true dwarfs, but I also included

two trees on a semi-dwarf (MM111)

rootstock. The semidwarf trees grew very well...but they've already gotten

quite a bit bigger than their neighbors. So, when I grafted  onto

MM111

for some of this year's new trees, I expanded the within-row spacing to 6

feet, hoping that the additional elbow room will help our semidwarf

apples

achieve their full potential while still toeing the high-density line. I

also plan to train the MM111 trees' limbs down considerably below the

horizontal this time around, which I was a bit more cautious about in

previous years but which I've since decided is definitely a good option

for

high-density apples in the backyard.

onto

MM111

for some of this year's new trees, I expanded the within-row spacing to 6

feet, hoping that the additional elbow room will help our semidwarf

apples

achieve their full potential while still toeing the high-density line. I

also plan to train the MM111 trees' limbs down considerably below the

horizontal this time around, which I was a bit more cautious about in

previous years but which I've since decided is definitely a good option

for

high-density apples in the backyard.

I also opted to branch

out and try yet another rootstock this year --- M7, which will produce

trees midway in size between the true dwarfs on Bud 9 and the semidwarfs

on MM111. My M7 trees went into the ground at 53-inch spacing but will

otherwise be treated the same as the MM111 trees. I'll be curious

to see, over the next few years, which rootstock turns out to be the best

fit for high-density plantings on our farm. It's a bit of a tradeoff ---

the more dwarfing the rootstock, the more precocious the tree, meaning

that we'll get more fruits faster. But, at the same time, truly dwarf

rootstocks have a hard time growing if you don't give them constant TLC,

and a few of the trees in my original planting (on Geneva-11 or Bud 9

rootstock) did fail to thrive.

Hopefully, either the M7 or MM111 trees (or both) will provide a happy

middle ground --- apple trees that do pretty well without watering and

other bonus attention, but that also produce within a few years after

planting.

I've read lots of good and bad about espaliers (my third high-density apple experiment), so I earmarked only one tree for this final endeavor.

I settled on an informal design set against the south side of our front

porch and began by bending the young tree so the top was nearly

horizontal. As watersprouts inevitably pop up from the flattened trunk,

I'll probably bend them at a 45-degree angle to create a type of lattice

pattern...or whatever seems to make sense from the growth pattern of the

tree. Since I'm far from confident that my espalier will thrive,

though, I chose our Chestnut Crab for the experiment ---after all, I'm

mostly growing this sweet crabapple variety out of sentimental attachment to a similar

tree of my youth, so I won't feel too bad if I don't get high yields.

I'll keep you posted on

all three new plantings in the years ahead...and hopefully will be able

to report in summer 2015 about our first big crop from our older

high-density planting. In the meantime, stay tuned for another post

about next year's high-density experiment, which will veer off in yet

another direction.

This is the first year we've

trained Huckleberry and Strider to be good in the morning.

They've had to sleep on the

porch at night due to Huckleberry's problem of waking everybody up at

the crack of dawn.

With this new hallway door we

block off his chance to be a morning cat.

The

chicken-lovers among you will be thrilled to hear that I'm celebrating

Thanksgiving early by putting my chicken books on sale! But before you

go nodding off, you can get the first book without plunking down a cent

--- The Working Chicken is currently free on Smashwords and at Barnes & Noble.

Find out why hard-nosed homesteaders don't name their chickens and much

more in this photo-rich introduction to backyard chicken care.

The

chicken-lovers among you will be thrilled to hear that I'm celebrating

Thanksgiving early by putting my chicken books on sale! But before you

go nodding off, you can get the first book without plunking down a cent

--- The Working Chicken is currently free on Smashwords and at Barnes & Noble.

Find out why hard-nosed homesteaders don't name their chickens and much

more in this photo-rich introduction to backyard chicken care.

If that introduction tempts your appetite, my more in-depth series, Permaculture Chicken,

includes three books bound to make your chicken-keeping adventure run

more smoothly. And each ebook is marked down to 99 cents this week ---

buy them all and save 74%! Here are the links: Permaculture Chicken: Incubation Handbook, Pasture Basics, and Thrifty Chicken Breeds. Maybe next year you can grow your own free-range chicken for Thanksgiving!

Thanks for reading! And if you like what you read, why not make my day by leaving a review?

The trick to pulling

honeysuckle vines from tall trees is pressure.

Pull too quick and the leaves

can strip off.

A slow and steady pace seems

to yield the best results.

We

live deep down in a valley (known locally as a holler) where we seldom

feel breezes and even less seldom are faced with strong winds. So...I

get lazy. I lay down cardboard kill mulches

with just a rock or two to weigh the sheets down (if that), and this

fall I minimized the number of bricks holding down the sides of our quick hoops to a mere six per 15-foot span.

We

live deep down in a valley (known locally as a holler) where we seldom

feel breezes and even less seldom are faced with strong winds. So...I

get lazy. I lay down cardboard kill mulches

with just a rock or two to weigh the sheets down (if that), and this

fall I minimized the number of bricks holding down the sides of our quick hoops to a mere six per 15-foot span.

But I've noticed recently that big changes in temperature do bring

winds, even down here in our holler. And those roaring winds toss

cardboard around the yard and whip right through lazily built quick

hoops. The results are shown above.

When I went out to fix my quick hoops Monday afternoon, though, I still didn't

increase the brick count. With one wind rushing through our valley

already this winter, chances are we won't see another until March.

In an earlier post, I teased you by saying that next year's high-density

experiment will veer off in an entirely new direction. But, really, it's

the same experiment...just with a different species of tree.

High-density apple

orchards have become big business in the U.S., but at this time, pears

are mostly grown in a more traditional, spaced-out setting. However, one

report I read mentioned that high-density pear plantings are already

common in Europe, suggesting that close plantings can be appropriate for

this other pome as well. Since I have several additional pear varieties that I want to try out

but not enough space for several additional full-size trees, I figured

--- why not experiment with a high-density planting for pears?

The best option for

high-density pear trees appears to be a 4-foot spacing with the limbs

tied down to 45 degrees below the horizontal. To make this work, the

New York State Horticultural Society experimenters recommend using

semidwarf rootstocks like OHF87, which

appeared to be quite acceptable in high-density plantings during the

eight

years of their study (and, the author thought, most likely also for the

entire

life span of the orchard). I ended up buying OHF513 instead for my own

planting since the nursery I wanted to order from uses this

similarly-sized rootstock rather than OHF87, so I guess in a few years

I'll be able to report on how well OHF513 does for high-density

plantings.

There are a few downsides to high-density pear

plantings that aren't a factor when similar strategies are used on apples. First, the

fruits on high-density pear trees tend to be on the small side, and pear

rootstocks also aren't as precocious as those used to dwarf apples. As a

result, the high-density pear researchers found that, even when

planting feathered trees, you really shouldn't expect your first small

pear crop until the third year after planting, and major production

won't begin until the fourth year. If you're starting with rootstocks that you

graft at home, you should add another year onto that figure, meaning

that we probably won't see any pears from our planned row until about

2018.

But what could be more

fun than grafting five little pear trees and setting aside another

garden row for planting out the young trees at this time next year?

Nothing! So, of course, I have to give it a shot.

I was skeptical about how

well the shapening

stone on the Oregon

battery powered chainsaw

would work, but I've used it several times now and it really makes the

chain sharper with just a short pull on the sharpening lever.

I know, I know, pies are

meant to be round. But this Thanksgiving, pies are squared (or at least

rectangular). In the past, I've carefully carried pies out across our

floodplain...only to find specks of mud atop my perfect crust or

meringue once we reached our destination. Not this year! Instead, I've