archives for 10/2014

One of my long-term goals

is to make our mulching campaign more sustainable. Buying in

straw has really helped build our soil and make my weeding work easier,

but it has  caused

problems too. First, there's the unique-to-us problem --- we can

only haul in heavy materials a few days a year due to the muddiness of

our driveway, so getting the straw back to our garden during wet times

is difficult. Then there are the more general problems --- price

and the introduction of weed seeds (notably curly dock last year and the grains themselves this year). All of those problems make me wonder if we wouldn't be better off growing the straw ourselves.

caused

problems too. First, there's the unique-to-us problem --- we can

only haul in heavy materials a few days a year due to the muddiness of

our driveway, so getting the straw back to our garden during wet times

is difficult. Then there are the more general problems --- price

and the introduction of weed seeds (notably curly dock last year and the grains themselves this year). All of those problems make me wonder if we wouldn't be better off growing the straw ourselves.

As a very basic experiment, I decided to try to mulch a bit more than we usually do with cover crops.

In the past, I've let the tops of cover crops break down on the beds I

planted them into as a way of building soil, but when the oats I planted

on August 1 began to bloom in mid-September, I had Mark cut them with

the weedeater and then Kayla and I gathered the tops to mulch our

strawberries.

It took about six beds of

oats to mulch one bed of strawberries, and even though we spread the

leaves and stems pretty heavily, I'm not sure if that will be enough to

suppress weeds once the oats dry down. I also suspect that the C:N ratio

of the oats will be relatively low at bloom stage (as opposed to

post-fruiting, which is when straw is collected), so this oat mulch

might not last as long as I'm accustomed to. But it's worth a

shot, especially since it's an ultra-easy way to start growing a bit

more of our own mulch. I'll keep you posted as the experimental

bed goes into the winter, and as we try out cutting other cover crops

for mulch.

It's been a year since we

upgraded to a nest box

for two.

Every now and then we'll find

an egg in the extra box, which makes it worth the effort in my book.

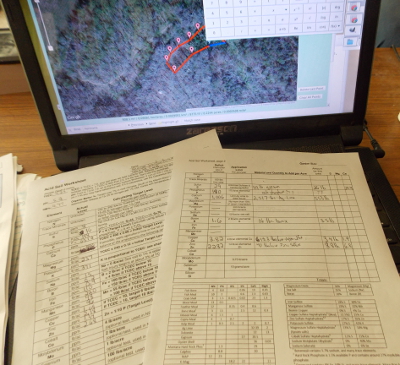

Experts recommend that you take your soil samples

in the fall if you're likely to need to add lime (or, presumably,

sulfur) to change the pH of your soil since the addition requires time

to react. Personally, I prefer to take soil samples in the winter

because the ground is very easy to dig into at that time of year (and

since our soil is already sweet). But, in reality, the best time

to take a soil sample is whenever you think about it and need some data.

Which

is a long explanation of why I was filling a flower pot with dirt from

several spots in our starplate pastures, mixing it up, and then tossing a

representative sample in a ziploc bag to go in the mail. Although

the texture of the earth in that area is excellent, there's clearly a major deficiency at play since very few plants felt like growing over the summer.

When the primary trees in an area are black locust and sassafras and

when even comfrey fails to thrive, you know you need a soil test.

Which

is a long explanation of why I was filling a flower pot with dirt from

several spots in our starplate pastures, mixing it up, and then tossing a

representative sample in a ziploc bag to go in the mail. Although

the texture of the earth in that area is excellent, there's clearly a major deficiency at play since very few plants felt like growing over the summer.

When the primary trees in an area are black locust and sassafras and

when even comfrey fails to thrive, you know you need a soil test.

Why did I feel the soil

test was so critical that it couldn't wait a few more months? I've

been itching to add a ruminant to our farm because they can get most or

all of their nutrition from pasture, but there's a flip side to that

coin. If your soil is deficient in a mineral and you expect

animals to get all of their food from that plot of earth, they'll end up

deficient in the same mineral. Starved soil could mean starved goats, and I don't want to risk it. So soil-testing in September it is.

It only takes a few minutes of filing to make our favorite high end Fiskars pruning shears cut like the day we bought it.

When we started researching battery-powered chainsaws,

I quickly narrowed down the options to three for serious

homesteaders. I actually asked each of these manufacturers for a

review saw, with varied results --- Stihl didn't even answer my query,

Greenworks turned me down, and Oregon sent out the sample saw we've been playing with.

Since we've only had the pleasure of trying out one of the options,

this comparison is largely based on reviews from other sites, combined

with firsthand information from the Oregon saw.

When we started researching battery-powered chainsaws,

I quickly narrowed down the options to three for serious

homesteaders. I actually asked each of these manufacturers for a

review saw, with varied results --- Stihl didn't even answer my query,

Greenworks turned me down, and Oregon sent out the sample saw we've been playing with.

Since we've only had the pleasure of trying out one of the options,

this comparison is largely based on reviews from other sites, combined

with firsthand information from the Oregon saw.

Stihl makes a battery-powered saw (MSA 160 C-BQ)

that might head the pack. However, it's hard to get any solid

data on how the saw operates since Stihl only sells through their

dealers, so online reviews are scanty. The price at our local

dealer is $329.95 plus the cost

of the 36V battery (an additional $260), making this the most expensive option by far. However, one review site

felt like the Stihl saw was twice as fast and cut twice as long as the

Oregon saw, so if you want a battery chainsaw to take over all of the

work of a gas saw, this might be the right choice for you.

Oregon makes the chainsaw that looked the most enticing from Amazon reviews (CS250).

The saw costs $249 with no battery, $349 with the smallest available

battery, and $449 with the largest available battery (which is what we're using). In addition

to being in the power class (40V) that is somewhat comparable with

gas-powered chainsaws, the CS250 has the added perk of having a stone

built into the saw so you can sharpen your chain with the pull of a

lever. I suspect that this feature will prove to be especially handy since a

battery saws are very sensitive to dull chains that make the motor

work harder. Reviewers (and our own experience) suggest that one  battery

will cut for about an

hour and that the saw can easily buck trees up to 9 to 12 inches in

diameter

(depending on the hardness of the wood). In a pinch you can cut

down larger trees as well --- our saw made it through a 17-inch

box-elder (a soft wood) without much trouble, but the job did require a

faster battery charge than usual. As a side note, if you cut too

aggressively, the Oregon saw will shut off to protect the motor, which we've only noticed once but which some reviewers have had trouble with.

battery

will cut for about an

hour and that the saw can easily buck trees up to 9 to 12 inches in

diameter

(depending on the hardness of the wood). In a pinch you can cut

down larger trees as well --- our saw made it through a 17-inch

box-elder (a soft wood) without much trouble, but the job did require a

faster battery charge than usual. As a side note, if you cut too

aggressively, the Oregon saw will shut off to protect the motor, which we've only noticed once but which some reviewers have had trouble with.

Greenworks sells a saw (20312 DigiPro) that is cheaper but possibly less powerful than Oregon's offering. On Amazon, Greenworks' saw

costs $140 with no battery, or $267 with a battery equivalent to

Oregon's largest.

The lower price seems to equate to a slightly less powerful saw (even

though the batteries are 40V just like Oregon's). On the other hand, it's hard to

say whether the possibly shorter run time and reported struggle with

bigger trees is just a result of the larger bar making people more

likely to be overambitious.

I'd love to hear from

anyone who has used these saws and can provide first-hand

information. Do you feel like your saw is able to handle

moderate-scale homesteading tasks, even if it would lose a battle

against a gas-powered chainsaw? Why did you choose the model you

ended up bringing home?

When I checked up on the

freezer vent hole I discovered a drip from the lid.

Maybe water is flowing off

the lid and past the seal into the inner lid?

I'm thinking of cutting a

tarp just big enough to cover the lid with enough left over surface

area to drape over the seal.

Is it worth babying a Brown Turkey fig by giving it the prime warm spot beside our wood-stove alcove? Since we already have two fig varieties that are hardier in our climate

(Chicago Hardy and Celeste), the answer will be based on taste.

Daddy was kind enough to give me one of his Brown Turkey figs, which we

roasted along with three Chicago Hardy figs and then sampled to solve

the mystery.

The upshot? I

thought that the Brown Turkey fig had a slightly figgier flavor than the

Chicago Hardy and contained less acidity, but both varieties ranked

about the same in terms of quality of overall flavor. Mark

preferred our Chicago Hardy (although I didn't blindfold him, and he's

always kind about saying that whatever I put in front of him from our

farm is better than any other option).

Looks like I'll be saving

that ultra-special spot for a different not-quite-hardy-here

edible. The possibilities are endless!

I wasn't feeling any

resistance when I first engaged the sharpening stone on the 40

volt Oregon battery powered chainsaw.

Turns out you can install

the stone backwards and

the cover still fits.

Expect to see sparks flying

for the few seconds of sharpening.

Our fava beans are starting to bloom! The flowers are definitely photogenic, but will the resulting beans be tasty?

Of course, since I'm primarily interested in the fava beans as a cover crop,

the real question is --- how much biomass will they produce and do they

mix well with others? The jury's still out on the first question,

but the mixing results are starting to come in.

The photo above shows some fava beans I interplanted with oats --- even

though the beans are a bit hard to see to the human eye, the plants are

doing nearly as well as those grown alone and mulched in another

bed. On the other hand, fava beans at the feet of sunflowers are

much more spindly, perhaps because they're in soil that I haven't babied into top productivity yet.

Or perhaps the sunflowers simply shade the fava beans too much, or the

sunflowers' established roots are hard to compete with? This

second hypothesis seems more likely since fava beans in poor soil

interplanted with oilseed radishes look nearly as good as those

interplanted with oats.

Have you tried mixing fava beans with other cover crops? I'm

always curious to hear about cover crop mixtures that do and don't make

the cut.

How long does it take us to

get to an East Coast beach?

It's about an 8 hour drive

depending on lunch breaks and wrong turns.

We always enjoy resting at

the beach, but we really start missing our place in the mountains after

only a few days.

We really hadn't planned a second beach vacation just a year after our Pawleys Island excursion,

but when I started getting crabby in the middle of this past summer, we

decided something to anticipate would be good for morale. Pawleys

Island was Mark's childhood haunt, so it seemed like we should visit my

old stomping grounds this time around for balance. My family

always used to hare off to camp on Ocracoke every summer, but Mark and I

instead opted to stay in a beach-front condo in Rodanthe, an hour's

drive and a ferry ride further north up the island chain.

We really hadn't planned a second beach vacation just a year after our Pawleys Island excursion,

but when I started getting crabby in the middle of this past summer, we

decided something to anticipate would be good for morale. Pawleys

Island was Mark's childhood haunt, so it seemed like we should visit my

old stomping grounds this time around for balance. My family

always used to hare off to camp on Ocracoke every summer, but Mark and I

instead opted to stay in a beach-front condo in Rodanthe, an hour's

drive and a ferry ride further north up the island chain.

I

was excited to get to enjoy Outer Banks waves again, since Pawleys

Island's waterworks are puny in comparison. Unfortunately, a

dredger made swimming a bit different than I was used to since it

churned up masses of seaweed while harvesting sand to rebuild

hurricane-damaged dunes. I didn't mind swimming amid seaweed,

though (and I even stole a bagful for a garden experiment --- more on

that in a later post).

I

was excited to get to enjoy Outer Banks waves again, since Pawleys

Island's waterworks are puny in comparison. Unfortunately, a

dredger made swimming a bit different than I was used to since it

churned up masses of seaweed while harvesting sand to rebuild

hurricane-damaged dunes. I didn't mind swimming amid seaweed,

though (and I even stole a bagful for a garden experiment --- more on

that in a later post).

Either

Mark or I will regale you with the tale of our biggest adventure --- a

visit to the Wright Brothers National Memorial --- in a later

post. Otherwise, we mostly just soaked up the sounds of the ocean,

with occasional sunrise walks on the beach (for me), jaunts to the

seafood market (for Mark), and general relaxation. One of my

favorite events was a morning walk up the road to a little gift shop

where they baked fresh cinnamon buns, during which time I talked to the

lady in charge about the raccoon that had shown up on her porch and

about local sights. I never quite caught the lady's name, but I'm

still thinking of sending her a postcard since I felt like if we'd

stayed longer, she and I might have become friends.

Either

Mark or I will regale you with the tale of our biggest adventure --- a

visit to the Wright Brothers National Memorial --- in a later

post. Otherwise, we mostly just soaked up the sounds of the ocean,

with occasional sunrise walks on the beach (for me), jaunts to the

seafood market (for Mark), and general relaxation. One of my

favorite events was a morning walk up the road to a little gift shop

where they baked fresh cinnamon buns, during which time I talked to the

lady in charge about the raccoon that had shown up on her porch and

about local sights. I never quite caught the lady's name, but I'm

still thinking of sending her a postcard since I felt like if we'd

stayed longer, she and I might have become friends.

Kayla dropped by to check

on the animals once during our five-day absence, and it sounded like

the only problem was a few broken eggs in one nest box. The ducks

miraculously learned to use their own nest box right before we left, so

the sea of eggs we came home to was mostly clean-shelled, and the

opossum who came to visit while we were  gone

was eliminated by Lucy. We even arrived back home in time to

scurry around for about an hour before dark Saturday evening preparing

for the first-frost-that-didn't-quite-happen.

gone

was eliminated by Lucy. We even arrived back home in time to

scurry around for about an hour before dark Saturday evening preparing

for the first-frost-that-didn't-quite-happen.

Mark and I both agreed

that our farm is even more beautiful than the ocean...but that we might

not have enjoyed its current beauty as thoroughly if we'd never left

home. Next year, we might be due for a staycation, or perhaps

we'll explore something else entirely --- the Outer Banks was fun, but

the landscape was almost too familiar for me. I like vacations to

be an adventure, so we'll have to put on our thinking caps for next

year!

It was nice seeing a full

size replica of the original Wright flyer, but what Anna and I both

enjoyed the most was the 30 minute talk given by one of the park guides

named Amanda.

The details and enthusiasm

she expressed really brought those years in the early 1900's alive in a

way that pushed my invention buttons.

At one point the brothers

were frustrated and announced it would take 1000 years for man to fly,

but their clever sister convinced them to give it another try.

There are two kinds of

gardener responses to the first fall frost. Some of you are

probably sick of garden tasks and are quite happy for the cold weather

to come and put your garden to sleep. (This is probably the more

healthy reaction to the inevitable loss of summer.) Then there are

the obsessive people (like me) who will spend days protecting every

single plant in hopes that this current frost is just going to be a

fluke. We obsessive types figure that (previous data to the

contrary), there's bound to be another month or two of Indian summer to

enjoy...if we can just ease our gardens through that one bad night.

In an effort to keep my obsessive side under control, we often plan our vacation

around the first-frost date, figuring that if we're off-farm, I won't

be able to run around like a chicken with its head cut off. And

that strategy kinda works. The photo above shows what I picked to

take with us on vacation, just in case the frost came while we were

gone...

...and this photo shows

some of what I picked in the two hours of daylight left when we got home

(with a frost predicted for that very night). I plucked figs and

raspberries and tomatoes, then ran out of time and just cut the whole

pepper plants to be managed inside the next morning.

And, after all that, it

didn't quite frost. Yes, one of my outside thermometers read 32

degrees on Sunday morning and there was a little bit of ice in the

wheelbarrow, but only the basil and summer squash looked nipped and I

saw no frost on the ground. Still, I was glad that I'd taken the

time to bring in vegetables curing on the front porch,

and that I'd picked the last summer treats. The baskets full of

food gave me an excuse to fire up the oven and bake some troubled

butternuts, taking a bit of the edge off a cold morning. With

similar temperatures Monday morning, though, Huckleberry required an

actual fire in the wood stove, so I guess I failed in my other obsessive

campaign --- to hold off on fire-building until after the first frost.

We picked up our first goat

today!

A tarp covering the backseat

and a junk sheet to absorb any accidents worked like a charm in getting

our goat safely home.

Total travel time with our

new goat was just over 2 hours.

We brought home our first

goat Tuesday! We're planning on getting a second goat this week

(who's all picked out --- more on her later), but for the day, goat #1

got to be an only child. She also appears to be nameless ---

we're taking suggestions if you can think of just the right appellation

for our farm's first caprine resident.

Names aside, goat #1

wasn't entirely thrilled at spending two hours winding down country

roads in the backseat of our car, but she only bleated a few

times. Once we disembarked, though, the struggles began. As

total neophytes to goat wrangling, we hadn't considered the species'

extreme aversion to water, so we chose to bring home goat #1 on a day

when the creek was about knee high and the floodplain was one big mass

of puddles. Our nanny was just starting to get the hang of walking

on a leash when we came to the first body of water...and then she

decided that being dragged was superior to walking. I ended up

carrying the poor (and heavy) beast about halfway up the floodplain,

stopping to drag and cajole her through drier spots, and the goat and I

were both pretty tuckered out by the time we got home.

Poor Mark had just driven for two hours in heavy rain with goat horns jabbing him in the back of the head, so he wasn't much better off. Still, he managed to leash Lucy and take her for a walk, then to introduce our obedient dog to the new goat

with no major trauma on either side. We'll do a more serious

training session later, but I'm about 75% sure our smart farm dog got

the message --- goats are to be protected, not chased. (Rolling in

their manure, though, is definitely high on Lucy's list.)

Before

shutting our new nanny away in the starplate coop for her much-deserved

rest, I let her browse some oat cover crops (which she probably would

have eaten all day if I'd let her, but I started getting worried about

bloat even though that probably wouldn't be a problem at this time of

year). A few feet further down the trail (with the goat walking

nicely now that we were out of the marsh), she found a fenceline covered

with Japanese honeysuckle and began to chow down --- or, rather, to

daintily pick the leaves off the stems, proving that she may be a goat,

but that she's also a lady.

Before

shutting our new nanny away in the starplate coop for her much-deserved

rest, I let her browse some oat cover crops (which she probably would

have eaten all day if I'd let her, but I started getting worried about

bloat even though that probably wouldn't be a problem at this time of

year). A few feet further down the trail (with the goat walking

nicely now that we were out of the marsh), she found a fenceline covered

with Japanese honeysuckle and began to chow down --- or, rather, to

daintily pick the leaves off the stems, proving that she may be a goat,

but that she's also a lady.

Once our nanny saw the

dry straw inside the coop, though, all thoughts of food were

forgotten. I brought Unnamed Goat some stalks from sweet corn,

sorghum, and sunflowers to tide her over until morning, then shut her in

so she could begin learning her new home.

My conclusions so far? Goats --- even ones with long horns --- are

extremely gentle even when manhandled. And their ability to eat

the weeds is very satisfactory. Only time will tell how well we

work the species into our farm, but I'm excited to begin to learn the

ways of goats.

We got our first goat gate

frame finished today.

The Oregon

battery powered chainsaw

made it easy to cut 2x4's where I would normally need to stretch an

extension cord.

I suspect that by the end of the week, you're going to be thoroughly sick of reading about goats. Oh well....

I

loved all of your name suggestions, but when Mark and I finally had

time to sit down and talk Wednesday, I learned that a name had come into

his head nearly as soon as we saw our goat:

Abigail. Mark told me that I had final say in the name

department, but I liked his choice --- simple and pretty. So

Abigail she is!

I

loved all of your name suggestions, but when Mark and I finally had

time to sit down and talk Wednesday, I learned that a name had come into

his head nearly as soon as we saw our goat:

Abigail. Mark told me that I had final say in the name

department, but I liked his choice --- simple and pretty. So

Abigail she is!

As I mentioned previously,

Abigail is a hybrid between a Saanen and a Nigerian (plus a smidge of

Nubian blood), which makes her moderately sized even though she's fully

grown. We hope she's all knocked up, the father of her upcoming

kids being a similar mixture of Saanen and Nigerian genes.

Unfortunately, Abigail's owner wasn't keeping track of her cycles, so

our goat might be due any time between the beginning of February and the

beginning of March. Chances are relatively good that she'll have

twins, like she did this year.

The photo above shows

Abigail in situ in her old habitat, where she shared a rotational

pasture with a buck, a doe, two kids, and a milk cow. Her previous

owner explained that she's been breeding away from the dairy look with

all of her animals, aiming for a chunkier body type instead that does

better on pasture.

I'm

just beginning my hands-on goat education (despite copious reading), so

I'm not 100% sure whether my gut feeling that Abigail could use a bit

more body weight is accurate. Her previous owner showed me how to

feel for fat along her spine, illustrating that Abigail isn't as

emaciated as she looks to the untrained eye. It will be a learning

process to start gauging the fullness of her rumen (the indentation in

the photo to the right) and her fat stores, a bit of a tricky campaign

since I hope to get away without feeding Abigail any appreciable grain

(at least until she kids). Trickiness aside, I'm already in love

with the idea of an herbivore who can get most or all of her nutrition

from weeds and brush rather than feed from a bag.

I'm

just beginning my hands-on goat education (despite copious reading), so

I'm not 100% sure whether my gut feeling that Abigail could use a bit

more body weight is accurate. Her previous owner showed me how to

feel for fat along her spine, illustrating that Abigail isn't as

emaciated as she looks to the untrained eye. It will be a learning

process to start gauging the fullness of her rumen (the indentation in

the photo to the right) and her fat stores, a bit of a tricky campaign

since I hope to get away without feeding Abigail any appreciable grain

(at least until she kids). Trickiness aside, I'm already in love

with the idea of an herbivore who can get most or all of her nutrition

from weeds and brush rather than feed from a bag.

I've

read that goats need a caprine friend, and Abigail's buddy will be

arriving soon. In the meantime, though, I was surprised by how

much our first goat craved being close to us. Wednesday morning, I

made her a little goat tractor out of four cattle panels in the weedy

area at the top of the front garden, but our poor little goat just stood

at the fence and bleated instead of chowing down.

I've

read that goats need a caprine friend, and Abigail's buddy will be

arriving soon. In the meantime, though, I was surprised by how

much our first goat craved being close to us. Wednesday morning, I

made her a little goat tractor out of four cattle panels in the weedy

area at the top of the front garden, but our poor little goat just stood

at the fence and bleated instead of chowing down.

Some of her agitation was

initially due to being unsure about Lucy, since Abigail's previous

owner used dogs to herd her animals (extremely well!), meaning that our

goat was sensitive to a canine hanging out nearby. But, mostly,

Abigail was just lonely. So we instead opted to tether her within

reach of a bed of oat cover crops right beside where Mark and I were

working, which made her much happier.

It's a good thing that

Abigail isn't bound for the freezer, because I could feel myself bonding

with her nearly immediately. She's a little shy, but quickly

learned to come toward me rather than running away once I gave her a

little dried sweet corn

and an over-size summer squash. She's getting better at walking

on a leash already, and hopefully will soon be coming when she's

called. Now I just need to learn some goat noises since the clucks

I'd originally been using made Lucy think I was talking to her....

More seriously, our doeling is also a prime pastured animal since she and her cohorts have been raised on browse (and milk) alone since birth. That should result in a well-developed rumen that will serve them well during their pasturing career. A few other doelings (and, I believe a wether) are currently available from the same breeder if you're looking for small pastured milk goats and are willing to drive to the Roanoke/Blacksburg area. The links up above in the post will lead you to the breeder's facebook page and website for more details. Tell her I sent you and she'll give you the $300 price on the Aowen's granddaughter!

We harvested our Scarlet

runner bean shade trellis this week.

Summer is now officially over.

Feeding goats naturally

seems to be a complicated subject, which I'm just starting to wrap my

head around (so readers should feel free to jump in if you think I'm off

base). From what I understand, the ancestors of our cultivated

goats would have been eating browse --- rough plant matter like tree

leaves, blackberry brambles, and so forth. They needed to consume

lots of this roughage to get enough energy to live and grow, and their

digestive system has evolved to require that kind of bulk fiber.

Grain

is a recent introduction to the goat's diet, and while it can help a

doe keep on weight when she's producing lots of milk, grain can also be

hard on a goat's gut since she isn't really adapted to eat it.

That makes the supplement more of a tradeoff than you'd find with your

dogs --- fancier rations will probably just make your canines happy, but

more grain can make a goat sick.

Grain

is a recent introduction to the goat's diet, and while it can help a

doe keep on weight when she's producing lots of milk, grain can also be

hard on a goat's gut since she isn't really adapted to eat it.

That makes the supplement more of a tradeoff than you'd find with your

dogs --- fancier rations will probably just make your canines happy, but

more grain can make a goat sick.

So why give her any grain

at all? Humans generally want the most that we can get out of our

livestock, so we've bred dairy goats to produce much more milk than

their ancestors would have in the wild. Producing that milk

requires extra energy and protein, and most goats will get really skinny

if milked hard on pasture alone. Think of this as a bit like

Appalachian Trail thru-hikers --- they physically can't

carry enough food to keep them well nourished while on the trail, so

they often gorge on ice cream and other concentrates when they hit

towns. Grain is the dairy goat's ice cream --- it helps a doe put

back on the pounds, but it's not necessarily good for her in the long

run.

Now, there are alternatives to grain that still provide concentrated nutrition. For example, Nita provided some excellent guest information in my ebook $10 Root Cellar

about how she grows and prepares carrots, beets, parsnips, rutabagas,

and (sometimes) mangels to keep her milk cow in fine flesh while milking

over the winter. And there's also something to be said for

choosing individual milking animals that have well-developed rumens from

a childhood on pasture and that don't produce quite as much milk, since

animals like this probably won't need as much nutritional

supplementation. But, in the end, most people end up giving at

least a little bit of grain to their milking animals at certain times.

Returning to your point, there is

some controversy about when a doe most needs extra nutrition --- while

milking heavily, or when pregnant. Most sources will only mention

the latter, but others tell you that it's imperative to have your doe in

relatively good condition at the start of her pregnancy if you want her

to easily get and stay pregnant. The trouble is that if you feed

much grain while she's actually pregnant, the kid(s) will grow extra

large, which can result in complications during birth. So, your

best bet is to get your doe in tip-top shape before she gets pregnant,

to cool it on the grain while she's actually pregnant, then to pick back

up with grain (or other supplements) in proportion to how much milk

she's producing after she gives birth.

Of course, all of this is

still book learning at the moment. In a year or two, I'll

probably laugh at the lack of nuance in my understanding of the subject

but, for now, I'll keep Abigail's treats to a minimum but will provide

her with lots of excellent browse to keep her healthy.

(As a side note, during

day one with two goats, it rained like crazy, so our girls have been

enjoying room service --- masses of Japanese honeysuckle torn off the

side of the barn, a handful of oat leaves, several sweet-corn stalks,

two sunflower plants, some comfrey leaves, and a sorghum stalk. Abigail thinks the oats are the best, followed by honeysuckle and comfrey, while our little doeling

still looks a bit befuddled by her new home but chowed down on quite a

bit of honeysuckle. Hopefully it'll dry off enough to get them out

on pasture for a better quality photo shoot soon!)

We came up with a name for

our second goat.

Artemisia.

Anna came up with it today over lunch.

The above shelter is where

she slept during her first few months.

One of the new

requirements that we're having to get used to with goats is the need to

provide free-choice minerals. With chickens, additives are

included in the bagged feed, and I've lazily assumed that the feed

company knows what they're doing. But since goats get most of

their nutrition from pasture, I need to choose a mineral supplement to

make sure their diet is well-rounded.

While

I'd like to buy goat minerals locally, my research thus far has turned

up only solid mineral blocks at our nearby feed stores. Unlike

horses and cows, solid minerals aren't recommended for goats since the

caprines' smaller teeth can't get enough minerals off the block to keep

them healthy. So I started hunting down loose goat minerals

online.

While

I'd like to buy goat minerals locally, my research thus far has turned

up only solid mineral blocks at our nearby feed stores. Unlike

horses and cows, solid minerals aren't recommended for goats since the

caprines' smaller teeth can't get enough minerals off the block to keep

them healthy. So I started hunting down loose goat minerals

online.

Your first decision when

choosing between different types of loose goat minerals is whether you

want to go with a scientifically formulated product, or whether you want

to follow the advice of Pat Coleby in Natural Goat Care

and figure your goat will get all of her trace minerals from kelp, to

which you add only sulfur, copper, and dolomite. I'll probably

take a hybrid approach --- providing free-choice kelp but also giving

our goats access to a mineral mix. In terms of the latter, the

table below includes the five main sources I've found online for loose goat

minerals to be shipped to your door. The only option that doesn't

require shipping is Manna Pro from Tractor Supply, which can probably

be found semi-locally if we call around (and which is cheapest on my

chart since shipping isn't included).

| Purina (Valley Vet) | Manna Pro (Tractor Supply) | Jolly German Ultimate Goat Mineral | Sweetlix Meat Maker (Jeffers Pet) | Golden Blend (Hoegger) | ||

| Protein (%) | 4 | |||||

| Calcium (%) | 10 | 17.6 | 10 | 15.4 | 14.3 | |

| Phosphorus (%) | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | |

| Salt (%) | 43 | 13.2 | 43.5 | 11 | 22 | |

| Potassium (%) | 0.1 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 1.5 | 0.9 | |

| Magnesium (%) | 1 | 1.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 1 | |

| Sulfur (%) | 1.2 | |||||

| Iron (%) | 1 | |||||

| Cobalt (varies) | 240 ppm |

0.01% | ||||

| Copper (ppm) | 1775 | 1350 | 1775 | 1780 | 1500 |

|

| Iodine (varies) | 450% | 0.0007% | ||||

| Manganese (varies) | 2750 ppm | 1.25% | 0.03% | |||

| Selenium (ppm) | 25 | 12 | 25 | 50 | 26 |

|

| Zinc (ppm) | 7500 | 5500 | 8000 | 12500 | 4000 | |

| Vitamin A (IU/lb) | 130000 | 300000 | 140000 | 300000 | 220000 | |

| Vitamin D (IU/lb) | 11000 | 30000 | 11000 | 30000 | 45000 | |

| Vitamin E (IU/lb) | 750 | 400 | 750 | 400 | 220 | |

| Price | 42.8 | 9.99 | 35.99 | 39.95 | 54.95 | |

| Pounds | 25 | 8 | 15 | 18? | 25 | |

| $/lb | 1.71 | 1.25 | 2.40 |

2.22? | 2.20 |

|

Assuming you don't need

to choose your goat minerals based solely on price, there are a few

other things to consider as you peruse the chart above. Plain salt

can be provided free choice  in

a separate compartment, so you might want to choose something like

Mannapro or Sweetlix with a low salt content so that your goats will

only eat the trace minerals if they're craving something other than

(cheap) salt. You might also want to look at your soil test

results if you plan to feed your goats primarily on pasture, then to

select a mineral mix high in the ingredients that are scarce in your

soil.

in

a separate compartment, so you might want to choose something like

Mannapro or Sweetlix with a low salt content so that your goats will

only eat the trace minerals if they're craving something other than

(cheap) salt. You might also want to look at your soil test

results if you plan to feed your goats primarily on pasture, then to

select a mineral mix high in the ingredients that are scarce in your

soil.

And then there's the big

copper debate, which will be fodder for another post. Goats need a

lot more copper than other livestock, and some breeders provide boluses

(huge pills) of copper every few months to keep their goats healthy and

to combat worms. Others follow Pat Coleby's advice and add copper

sulfate to their goats' mineral ration for the same reason. More

on pros and cons of copper supplementation in a later post, but feel

free to chime in now if you have thoughts one way or another on any

goat-mineral-related issue. And I'd love to hear your feedback on

which mineral mixes you've used and on how well they've done at keeping

your goats healthy.

(As for the photos ---

yep, I'm busy leash-training our goats. When Lucy isn't involved,

the training sessions go quite well.)

The room we had for our

recent vacation had a 400 pound dumb waiter that made staying on the

third floor easy and fun.

It's called the Stair Tamer. Invented by Ricky

Edwards you can buy them from his welding shop in Shiloh North Carolina.

He also sells a 1000 pound

model that would make loading hay bales in a barn loft a lot easier

than the old fashioned method.

I promise to write about

something other than goats within the next week....or so. Would

you believe me if I said this post is about cover crops and fences?

Way back when we started making chicken pastures, we built our fences out of chicken wire.

The theory was simple --- chicken wire's cheap, and that's all we could

afford. Now, many of those fences are nearly lost beneath impenetrable hedges of Japanese honeysuckle...which

happens to be a plant that goats adore. The question became ---

although a chicken-wire fence obviously isn't going to keep in a

determined goat long term, would it be sufficient for goat retention

until the honeysuckle was gone?

Within half an hour, I

learned that the answer was no. Perhaps if the only goats involved

were little shrimps like Artemisia, my experiment would have worked,

but the fence bowed down under Abigail's hooves, and soon our doe

decided that the honeysuckle was greener on the other side of the

fence. Luckily, I was sitting on the porch watching at the time

because the result was a scary race around the yard, Lucy having decided

that anything running should be chased and Abigail having decided that

if she was being chased she would have to keep running. Once Mark

came out and collared Lucy, though, peace descended immediately ---

Abigail came right to me and so did Artemisia, and soon they were both

safely behind cattle panels

(although on less exciting browse). At least now I know that

worry number two isn't a concern --- a loose goat isn't going to

disappear into the woods, not if she knows I dole out dried sweet corn

every day or two.

The other thing I've been

learning this weekend is goat dietary preferences. In addition to

honeysuckle, Abigail adores oat leaves, red clover, plantain, and

broccoli leaves. She's also quite fond of the tops of oilseed

radishes, but is totally uninterested in the roots, suggesting that I

can put this cover crop to dual duty, feeding our herd and the soil with

the same planting. In fact, I suspect, I can do something similar

with oats since Abigail tends to browse the plants high enough that

they should regrow as well.

What about

Artemisia? She eats whatever's close to Abigail, since our little

doeling is much more interested in being sociable than in being

fed. Luckily, her pint-sized rumen fills up fast, and she always

seems fat and happy when I run my hands over her little round

body. It's extremely satisfying to watch our goats grow on weeds

alone.

We're making a limited run of

heated

chicken waterers that

utilize a nifty,

heavy duty heated bucket

from a company called Farm

Innovations.

I could've chose any number

of cheap handles for the lid, but decided to go with a fancy,

high end bird cage handle

that tops the project off with a bit of class.

You can save a little money

by making one yourself. We made a video

on how to make a heated chicken waterer that gives all the details if

you've got the time, tools, skills, and patience.

I got my soil test results back, and it's no wonder nothing wants to grow in the Starplate pasture

--- the pH is 5.2 and the soil is seriously deficient in calcium (and

also rather low on sulfur, phosphorus, boron, copper, and zinc).

Luckily, I was able to look back at my old lunchtime series for The Intelligent Gardener and generate a prescription to fix the issues.

I got my soil test results back, and it's no wonder nothing wants to grow in the Starplate pasture

--- the pH is 5.2 and the soil is seriously deficient in calcium (and

also rather low on sulfur, phosphorus, boron, copper, and zinc).

Luckily, I was able to look back at my old lunchtime series for The Intelligent Gardener and generate a prescription to fix the issues.

When liming soil, it's

best to apply the minerals in advance of other additions since the

calcium can cause other cations to wash out of the soil. So my

plan is to apply lime this fall, then gypsum, borax, copper sulfate, and

zinc sulfate in the spring. The hardest part of the endeavor will

be hauling 550 pounds of lime back through the muck to our core

homestead!

We've been making heated

bucket chicken waterers today.

My favorite

pipe thread sealant is

this Rectorseal No.5.

A thin coat on the threads is

all it takes for a tight seal.

A week ago, the ground

was so dry that I was considering turning on the sprinklers to get our

last round of lettuce seeds germinated in a timely manner. Since

then, it's rained and rained and rained. Six inches in seven days,

enough that we spent five of those days flooded in.

I

soon settled into donning wet clothes whenever I went outside ---

better to have only one set of damp pants and tops strewn around the

trailer, even though pulling on clammy clothing is never fun.

Otherwise, though, the rain isn't too difficult, especially since it

gives me the gumption to edit (my least favorite part of writing, but

more palatable when the alternative is getting soaked).

I

soon settled into donning wet clothes whenever I went outside ---

better to have only one set of damp pants and tops strewn around the

trailer, even though pulling on clammy clothing is never fun.

Otherwise, though, the rain isn't too difficult, especially since it

gives me the gumption to edit (my least favorite part of writing, but

more palatable when the alternative is getting soaked).

I wouldn't mind a dry spell soon, though (just in case the weather gods are reading this blog post). Now's prime leaf-raking

weather, but it's not worth hauling wet leaves home for bedding the

coops and mulching the garden, so the first fall of early leaves is

going to waste at the moment. The goats seem less scared of rain

than I'd thought, their annoyed bleating when stuck in the tractor more

closely correlated to the amount of honeysuckle present than to

rainfall, but I know they'd be happier if it were dry. Even our

water dog has been spending a lot of time in her doghouse, and our

younger rooster has a long-suffering look about him as he minds his

puddle-loving ducks.

I know that many of you

are currently facing drought conditions. I'd send you some of this

rain if I could! In the meantime, can you send us some sunny

thoughts in exchange?

We finished our first goat

gate today.

I used 2x2's for the frame to

keep it light and treated furring strips for the slats.

You got it!

Cleaning up weedy edges has been one of the major selling points of

goats, and I was excited (after the rain finally let up) to see how our

girls would fare in that department. To that end, I made a

temporary pasture using six cattle panels, encircling a roughly

650-square-foot problem area. This spot is where the old house

used to stand, and where blackberry brambles and honeysuckle have since

taken over the decaying wood. Could Abigail and Artemesia help us

with this thorny problem?

"Glad

to!" they chorused. The top photo shows the area a day and a half

after goat action began, at which point I was already starting to be

able to see wood rather than simply a huge thicket of weeds. In

contrast, the photo on the right is the before shot, taken moments after

our goats were let into the pasture on their first day. Our girls

enjoyed the browse so much that I had to bribe them with a little sweet

corn Tuesday evening before Abigail would let me put on her leash for

the walk back to the starplate coop. (I've learned that Artemesia

doesn't need her own leash --- she just trips along behind.)

"Glad

to!" they chorused. The top photo shows the area a day and a half

after goat action began, at which point I was already starting to be

able to see wood rather than simply a huge thicket of weeds. In

contrast, the photo on the right is the before shot, taken moments after

our goats were let into the pasture on their first day. Our girls

enjoyed the browse so much that I had to bribe them with a little sweet

corn Tuesday evening before Abigail would let me put on her leash for

the walk back to the starplate coop. (I've learned that Artemesia

doesn't need her own leash --- she just trips along behind.)

The bad news for those of

you who are itching to go out and get goats is --- I don't think our

girls are going to take the weeds down to the ground. They're so

good at carefully plucking the leaves off the stems that the blackberry

brambles and honeysuckle vines are still left standing even after the

girls are done eating. Perhaps in the dead of winter, when

pickings are slimmer, our goats will be more prone to do a total rehab

on a weedy spot like this, but I suspect we'll instead be sending Mark

in with the Swisher to bring this area back under human control. I guess that's why we got two weedcutters, right?

We shipped out 8 more heated

bucket chicken waterers today.

The creek was just high

enough to need proper

neoprene hip waders.

Last year, I wrote that I dug our carrots early. And this year...I dug them even sooner. All this rain

made a couple of my cabbage heads split over the weekend, and I know

that carrots are prone to the same ailment. I'd rather get those

orange roots out of the ground before problems arise. They

probably wouldn't grow too much bigger over the next week or two anyway

since many were already heftier than store-bought!

Last year, I wrote that I dug our carrots early. And this year...I dug them even sooner. All this rain

made a couple of my cabbage heads split over the weekend, and I know

that carrots are prone to the same ailment. I'd rather get those

orange roots out of the ground before problems arise. They

probably wouldn't grow too much bigger over the next week or two anyway

since many were already heftier than store-bought!

The downside of this

fall's carrot harvest is that it's much smaller than in years

past. I dropped the ball and didn't replant after a dry spell

caused sporadic carrot germination in July. Then the straw I

mulched with (which was supposed to be weed-free, since it was the

second round from the feed store) sprouted scads of little grain

plants. As a result, carrots were getting lost in the sea of cover

crops, and I opted to pull the vegetables out before they completely

disappeared.

Of course, half a bushel

of carrots is nothing to sneeze at. And, if I'm honest, I would

admit that I actually grew twice as many as we wanted last year --- Mark

was getting heartily sick of carrot sticks before the winter

ended. Our fridge root cellar

will keep the carrots we did grow this year crisp and sweet deep into

the winter, and next year we'll plant many more to feed the goats.

Today was a good day to harvest

sunflowers.

We planted so many that the

birds only had a chance to nibble in a few spots.

A friend of a friend is

selling some land about twenty minutes from our farm, and I promised to

spread the word in case any of you were interested. It's priced at

a thousand bucks an acre and has a lot of potential, full of ponds,

forested mountain-land, and open fields. There's an electric

hookup on site and spring water piped down to an old house, plus logging

roads make for relatively easy access. Here's the Craigslist ad for more information.

At 177 acres, the

property has the potential to be bought by several homesteaders and

managed as an eco-village or education center. Or, perhaps more

realistically, if two or three homesteading families went in on the

property together, you could share the land without anyone digging their

financial hole too deep. If you're interested in these shared

options, leave a comment below and chat with each other --- it would

make my day if several of our readers got together and relocated nearby!

How tall did our Chicago

Hardy fig get this year?

Just shy of 10 feet, even

after the hard frost it suffered last year.

The Celeste was almost half as high.

When you start providing

livestock with free-choice minerals, suddenly the options become a bit

overwhelming. We've narrowed our goats' selections down to:

a pre-mixed goat mineral

a pre-mixed goat mineral- kelp (for extra trace minerals)

- table salt (iodized or noniodized is debatable. We add the extra salt because we chose a mineral mix that's only 11% salt, but you should be aware that some people believe you shouldn't provide additional salt since it might prevent your goats from eating enough of the pre-mixed minerals. If you do opt for additional salt, sea salt would be a better choice, although more expensive.)

- baking soda (as a safety valve in case our goats' rumens get out of balance due to eating grain)

Some goat-keepers also provide:

nutritional

yeast (aka brewer's yeast, for extra protein. This is more often

mixed with a processed feed that provided free choice, though.)

nutritional

yeast (aka brewer's yeast, for extra protein. This is more often

mixed with a processed feed that provided free choice, though.)

- Diamond V XPC Yeast Culture (as a probiotic. This is generally mixed with feed rather than being put out for free-choice eating.)

- diatomaceous earth (for internal parasite control, although data suggests this may not actually do any good when taken internally)

And if you're worried about

your soil being particularly deficient in one or two minerals,

presumably you could provide those nutrients free choice as well if you

weren't worried about overconsumption. This last option might

hypothetically help remineralize

your soil...or you might just end up with a very healthy dog if your

canine, like ours, runs along behind the goats to slurp up their

"berries."

I'll close with two extra goat shots...because they're cute. And getting fatter?

The new goat gate uses a Zinc

coated 4 inch barrel bolt latch to keep our new girls in.

This pasture is connected to

their Star Plate home, where they get tucked into every night before it

gets dark.

The first figs on our Celeste

bush started turning maroon a couple of weeks ago, and ever since I've

been waiting with baited breath, hoping to taste a new fig

variety. Unfortunately, cool weather has slowed down ripening

considerably, and the only summer plants that are still bearing like

crazy are our red raspberries. The Celeste fig seemed to be stuck

halfway ripe.

With another potential

frost forecast, I decided to see if those Celeste figs were

tasteable. I plucked the fruits off the bush, cut them open...and

was disappointed to see colorless flesh inside. Unlike most

fruits, the telling color-change on a ripening fig

occurs hidden inside --- in the photo above, the fig on the left is a

ripe Chicago Hardy fig for comparison. I guess we'll have to wait

until next year to taste a ripe Celeste fig!

In the meantime, I should note that despite last winter's cold killing our Chicago Hardy plant

to the ground, we've still enjoyed perhaps a gallon of figs this

year. That harvest doesn't hold a candle to last year's bounty,

but it's not bad for a tree that started from the ground up this spring!

I found several shitake

mushrooms hiding in the

weeds today.

They were a little too damp,

but a couple of hours in the Excalibur fixed that.

I've been noticing little snippets of cover-crop observations lately, none of which is quite enough to make its own post. But maybe you won't mind a hodge podge.

The photo above shows how the yellow jackets are swarming around unopened fava-bean buds. I assume they're stealing nectar somehow, a bit like the ants I noticed on okra flowers a few years ago. Presumably unrelated to the yellow jackets, our fava beans have been blooming for weeks, but keep dropping the ovaries without setting fruit, so they might not be a good edible in our location after all.

Then there's the observation two of you made in comments,

that the puny fava beans between my sunflowers are due to

allelopathy. I hadn't realized that sunflowers were allelopathic,

but the internet suggests that is indeed the case, and that water

dripping off sunflower leaves can carry chemicals that make surrounding

plants do poorly. I guess sunflowers aren't the best candidate for

multi-species cover-cropping campaigns!

My last observation is four-footed. Goats love oat leaves

so much that I've been earmarking a large proportion of that cover crop

for goat treats. I can't help it! I know the soil loves oat

biomass too, but when Artemesia blats at me, I give in and provide any

treat I can think of. In case you're curious, my ability to spoil

animals is nearly unparalleled....

We retired some old hens

today.

They made it to the ripe age

of 1.5.

We had some escapes during

the process. I think that could be fixed by making the top of the kill

coop so we could open only one half at a time.

This is a very timely

comment because many of you are probably trying to figure out what to do

with all of those root crops (and fall fruits). I'll hit the

highlights in this post, but if you want to dig deeper, I've also set my ebook version

on sale to $1.99 this week so you can learn the rest of the story for

very little cash. (I guess that would turn your replica into a $12

root cellar?) And while you're over there, you'll probably want to snap up Low-Cost Sunroom, which is free today!

Anyhow, back to the

point. The advantages of our fridge root cellar are pretty

obvious. It was cheap and easy to build and it really works.

I particularly love how accessible the contents are --- the cook in

your family will be thrilled to be able to just pop open the door like

you would in a powered refrigerator and remove a few carrots or a head

of cabbage. And the dampness of the earth means that your roots

stay crisp and delicious for months after harvest.

The downsides are relatively minor, but they are

present. We use a very small amount of electricity to ensure that

the contents of our fridge root cellar don't freeze when outside

temperatures drop below the mid-teens Fahrenheit. If you lived in

Alaska, you'd probably have to do a lot more. And a fridge root

cellar won't do much during the summer months, so you'll need a different

storage method for your spring carrots. (I just stick them in the

real fridge inside.) Finally, youtube viewers

will call you white trash if you post a video showing how to build a

fridge root cellar, and your neighbors might feel the same way, so this

project is not for the thin-skinned.

The downsides are relatively minor, but they are

present. We use a very small amount of electricity to ensure that

the contents of our fridge root cellar don't freeze when outside

temperatures drop below the mid-teens Fahrenheit. If you lived in

Alaska, you'd probably have to do a lot more. And a fridge root

cellar won't do much during the summer months, so you'll need a different

storage method for your spring carrots. (I just stick them in the

real fridge inside.) Finally, youtube viewers

will call you white trash if you post a video showing how to build a

fridge root cellar, and your neighbors might feel the same way, so this

project is not for the thin-skinned.

I hope that helps you

make your fridge-root-cellaring decision! And I'd love to see some

reader photos of your own incarnations of the cheap root-storage device

if anyone's given our method (or something related) a try. Email me at anna@kitenet.net

and I'll share your root cellars with our readers (and maybe even add

them to the next edition of the book if they're unique enough!).

We used a kiddie pool

for the ducks when we

first got them, but it mostly got used as a place for frogs to meet and

mate this year.

Dumping the pool was bad news

for a bunch of late tadpoles, but we managed to transfer the above

cute newt to the Sky Pond for his new Winter home.

I was a bit disappointed by our goats' inability to eat a thicket of weeds to the ground,

but I've been thrilled at how well they do at cleaning honeysuckle off

our fencelines. Every evening, after walking the girls back to

their coop, I move five cattle panels into a new arrangement to prepare

for the next day. Two panels lean up against the

honeysuckle-covered fence, and the other three (and two fence posts and a

bit of rope) complete the enclosure.

I was a bit disappointed by our goats' inability to eat a thicket of weeds to the ground,

but I've been thrilled at how well they do at cleaning honeysuckle off

our fencelines. Every evening, after walking the girls back to

their coop, I move five cattle panels into a new arrangement to prepare

for the next day. Two panels lean up against the

honeysuckle-covered fence, and the other three (and two fence posts and a

bit of rope) complete the enclosure.

The next morning when I

bring the goats to their new pasture, Abigail runs right for the

honeysuckle and Artemesia soon follows suit. They gorge for a

couple of hours, then chew their cuds, then gorge again. By

dinnertime, that side of the fence is bare of honeysuckle leaves

(although some stems remain, proving that the goats will have to regraze

the same areas next year).

For the sake of

comparison, the photos above show yesterday's fenceline (left) and the

edge of tomorrow's fenceline (right). After reading that

honeysuckle leaves are equivalent in protein and total digestible

nutrients to alfalfa hay, I can understand why our girls do such a good

job removing the wily vine.

Back when I was just

reading about goats, I hadn't planned to let our new livestock within

our core homestead. In fact, I was going to keep them at least two

fences away just in case the tame deer (which is how I thought of them)

escaped and headed for my precious apple trees. Now I'm thinking

that maybe I overreacted. The only goat escape from my

cattle-panel tractors has been when I didn't tie one panel securely and

our little doeling slid out through the gap...then grazed right beside

the fence until I put her back in.

Now I'm thinking that

goats are like chickens --- they don't want to put in the energy to

escape as long as you keep them fat and happy. The big question

becomes: Can we keep the honysuckle buffet coming all winter? Only

time will tell!

Today makes the 2nd goat

escape so far.

How bad are they when they

get out?

Not that bad...Artemesia

yells a bit, but they seem fine once we tuck them back in.

(Don't worry, no animals

were actually harmed during the creation of this post. I know I just

ruined the dramatic impact of the story, but I couldn't have kept reading without that warning, so there you have it.)

(Don't worry, no animals

were actually harmed during the creation of this post. I know I just

ruined the dramatic impact of the story, but I couldn't have kept reading without that warning, so there you have it.)

Wednesday morning, Mark and I were supposed to go to the big city to get

our teeth cleaned. Instead, we had to wrap our minds around the

possibility of killing a dog.

Over the eight years

we've lived way back in the woods, we've had only a handful of uninvited

human visitors (good job, moat!), but nearly an equal number uninvited hunting dogs.

It seems like when hunting dogs get lost, they can feel Mark's good dog

energy, and they come wagging their tails at our door.

Unfortunately, the two

dogs I found beside the chicken coop Wednesday morning weren't wagging

their tails. One was sweet and submissive, but when I went to put a

leash on her, the other dog growled and rushed at me with bared

teeth. Only standing tall and yelling with my voice in its deepest

possible register prevented me from getting bitten, and I quickly

retreated out of harm's way.

Luckily,

the sweet dog had an owner's number on the collar, and I was able to

catch his girlfriend on the phone. She said her boyfriend was

unreachable on a construction site, but she and her father would be

right over. We tied up Lucy just to be on the safe side, called

the dentist to say we would be late, then settled down to wait.

Luckily,

the sweet dog had an owner's number on the collar, and I was able to

catch his girlfriend on the phone. She said her boyfriend was

unreachable on a construction site, but she and her father would be

right over. We tied up Lucy just to be on the safe side, called

the dentist to say we would be late, then settled down to wait.

When I finally heard the voices, father and daughter were fleeing up the floodplain away

from the dog. "He's never acted like that before," the girlfriend

said, tears slipping out of her eyes. Her father explained that

he'd gone to put a leash on the dog, but had gotten bit for his

trouble. The teeth hadn't broken his skin, but the father still

told us: "If you have to do something to protect yourselves or your animals, we'll understand."

We knew what he meant --- shoot the dog. The trouble is, while we can be hard-hearted about chickens, dogs are people to us. Did I ever mention that my brother once turned off Old Yeller

partway through, telling me that was the end, because he knew what was

coming and didn't want to have to soothe a grief-stricken sister?

Killing a dog in real life seems nearly unthinkable.

But, as Mark pointed out

after the dog's owners left, we also have a responsibility to our own

chickens, goats, cats, and dog. The biting dog had been lost in

the woods for two days, and whether that was long enough for something

like rabies to turn up or not, we had to protect the farm. So we

called the dentist once again to cancel, and then Mark went around

checking on the state of our guns. We didn't plan to do anything

drastic while the dogs were simply resting at the edge of our core

perimeter, but if they went after something, Mark resolved to shoot

first and ask questions later.

Luckily, as I mentioned

above, this story has a happy ending. The dog's real owner

couldn't be tracked down, but his hunting buddy could. The young

man showed up with a heavy stick, which he thrust into the dog's jaws as

it came after him. And as soon as the man snapped a leash onto the

dog's collar, the canine calmed right down. It turned out that

the submissive dog was in heat, and the other dog was merely guarding

his territory, but a calm, familiar face was enough to defuse the

situation. In the end, both dogs went home safely.

The moral of the

story? Have friends good enough to face down a possibly rabid dog

to save man's best friend. Or, maybe, have guns on hand to protect

your homestead from four-footed beasts. I'm not sure what I took

away from the experience, actually, except for an overwhelming urge to

sit in front of a fire with a cat on my lap, sipping some hot

chocolate. But I will be more cautious the next time I approach a strange dog...because hunting dogs sometimes bite.

We got one step closer to being ready for Winter with today's hose collection.

Your

first frost has come, or it's due any day, and you're probably ready

for winter's slowdown. But taking a few hours now to get your homestead

in order will save a few days in the spring. Here are the items at the

top of our winterizing list this fall:

Your

first frost has come, or it's due any day, and you're probably ready

for winter's slowdown. But taking a few hours now to get your homestead

in order will save a few days in the spring. Here are the items at the

top of our winterizing list this fall:

- Drain and put away hoses.

- Drain rain barrels and return gutter water to the ground.

- Run your mower and any other summer-only motorized equipment dry. This will make engines start much better come spring!

- Pull up and put away tomato stakes and other garden supports. Discard those old, blighted tomato plants somewhere far away from the garden.

- Wait until the leaves drop, then wrap fig trees and other plants you're trying to grow beyond their usual hardiness range.

- Plant any bare ground with cover crops if you've got time. (I'll plant rye for another week or so, but only in areas that I won't want to plant into until late May 2015.) If it's too late in the year for cover crops, mulch heavily, preferably with deep bedding from the chicken coop so the manure will have time to mellow before spring.

- Kill mulch new garden areas for next year.

- Cull excess animals and move chickens off pasture. We let ours run in the woods during the down season, but others move their poultry into greenhouses. Tractored chickens can be kept on pasture over the winter, but you'll tear up the ground a bit. Four-legged livestock can be put on stockpiled pasture, or can be moved inside onto deep bedding. The photo above shows what will happen if you skip this step...and that's after the ducks were only on an overused pasture for one extra week!

- Reward yourself for all this extra effort by ordering any new

perennials you have planned for fall planting. Ah, dreams of apples and

hazels....

I'm sure I'm

forgetting some essential winterizing elements, but that should get you

started. What else is top of the list at this time of year on your

homestead?

Why am I adding a bottom slat

to our new goat gate?

It turns out Artemesia can

squeeze through an opening only a few inches wide.

I don't think she was trying

to run away, she just wasn't ready to be tucked in.

One of our Wetknee Books

authors recently turned her novel into an audiobook, and the result is

inspiring! In fact, ever since listening to Kelly McCall Fumo's take on

werewolves, Mark's been talking about turning my non-fiction ebooks into

audiobooks too. I've dragged my feet so far because images are so

important to my writing process, but you can get fired up along with

Mark by listening to Aimee's novel "on tape" (as we old-fashioned people

still think of audiobooks).

And if the embedded sample entices you in, why not enter the giveaway below

and win one of three free audiobooks? Alternatively, if you're not a

member of Audible, you can download a free audio copy right now by

signing up for Audible's free trial. Here are the links to Aimee's book on Audible and Amazon (and you can also find it by searching for "Shiftless" in the iTunes store). Happy listening!

The 2014 crop of brussel sprouts

has not been doing too well.

Maybe it was too much rain at

the wrong time?

I think we'll switch back to

the old variety for next year.

I don't usually think of

marigolds as particularly bee-friendly plants. But anything blooming on a

warm, sunny day in late October is a plus. I guess the ten cents I

spent on last-chance seeds at the dollar store this summer was worth it.

Speaking

of "worth it," our goats continue to fill my days with pleasure. I

don't really know what we'll do in about a week once they're done clearing all of our fencelines, but Abigail says they aren't

going anywhere damp. Artemesia enjoyed her Saturday walk through the

gully to browse on honysuckle and multiflora rose, but Abigail said that

she didn't even want to get her feet damp. Nope, she'd just stand on

the log and wait until we were ready to move on.

Speaking

of "worth it," our goats continue to fill my days with pleasure. I

don't really know what we'll do in about a week once they're done clearing all of our fencelines, but Abigail says they aren't

going anywhere damp. Artemesia enjoyed her Saturday walk through the

gully to browse on honysuckle and multiflora rose, but Abigail said that

she didn't even want to get her feet damp. Nope, she'd just stand on

the log and wait until we were ready to move on.

We've been having a problem with our duck eggs getting dirty.

Tilting this laundry basket

at an angle should make it into a roll out nest box.

The eggs roll back where we

can get to them and the ducks can't step on them.

When Mark and I first started sharing Microbusiness Independence with the world, I was surprised by how many readers came back to me and said one of two things. First came: "Can we sell your chicken waterers for you?" I tried to explain that it was the uniqueness

of our product that helped our microbusiness grow and thrive, but then I

got the second comment: "I can't think of a unique product to make and

sell!"

When Mark and I first started sharing Microbusiness Independence with the world, I was surprised by how many readers came back to me and said one of two things. First came: "Can we sell your chicken waterers for you?" I tried to explain that it was the uniqueness

of our product that helped our microbusiness grow and thrive, but then I

got the second comment: "I can't think of a unique product to make and

sell!"

For me and Mark, ideas

have always been the easy part. I probably come up with an ebook idea

every week, only a small percentage of which I'll ever have time to

write. Meanwhile Mark dreams up a similar number of undeveloped product

ideas. But if you're among the multitude of readers who got stuck at the

"What can I sell?" stage, Tim Young's How to Make Money Homesteading is the solution to your problem!

Tim splits his book up

into three types of money-making ideas --- ways to make money from the

land itself, ways to use your skills to make money, and ways to produce

products to sell. There are probably hundreds of ideas scattered

throughout the relevant chapters, including gems such as making chicken

tractors for your neighbors, becoming an artificial insemination expert,

and hiring others to provide classes on your land. There's also a stern

admonition to eliminate your debt before embarking on your homestead

microbusiness, which I thoroughly agree with, along with a chapter on

saving money on the homestead and one on rethinking retirement.

My only complaint with How to Make Money Homesteading

is that Tim doesn't separate the wheat from the chaff when presenting

his money-making ideas. In my experience, unless you scale way up and/or

bring your wares to a big-city population, selling farm-fresh eggs and

similar products won't even pay minimum wage. But a

chapter near the end of the book on marketing helps you disentangle

some of the pros and cons of different types of businesses.

Plus, the eighteen profiles of homesteading families (including one on

us) show what's worked for other people on-the-ground, giving you an

idea about the advantages and disadvantages of each money-making

endeavor suggested in the book.

Which is all a long way

of saying --- if you're scratching your head about how to make a living

off the land, you should definitely read this book as part of your

brainstorming session. And you're in luck because Tim has kindly offered

to give one of our readers a free paperback copy of How to Make Money Homesteading. Enter the giveaway below for a chance to win!

a Rafflecopter giveaway

Our ATV stopped working due to a broken

prop shaft piece.

We got a new part in, but I

forgot to order the seal kit.

I'm starting to wrap my

head around goat digestion, but it's slow going since ruminants are so

very different from any other animal I've ever spent time with. Goats

are especially interesting because they're able to eat really fast,

filling up their rumen, then they slowly digest that food over the

course of the day. Which begs the question --- do our girls need to fill

up their rumen once daily? Twice? Keep it full all day? Or what?

I suspect that the lack

of an easy answer is due to the vast differences in nutritional value of

different food sources. Our girls have been gorging on honeysuckle

leaves for the last week or so, which probably means that Artemesia's

round evening belly is providing plenty of calories. Abigail's belly

never looks as round, but I suspect that's just the older animal's