archives for 09/2014

Most

folks will tell you to leave a grafted apple alone for its first year

of life. The goal is for it to grow straight and tall, into a

one-year-old whip that is hopefully four feet tall (for an apple on MM111).

Most

folks will tell you to leave a grafted apple alone for its first year

of life. The goal is for it to grow straight and tall, into a

one-year-old whip that is hopefully four feet tall (for an apple on MM111).

That makes a lot of sense if you want a tree to achieve its full height potential, but what if you plan to use high-density methods to fit more apples into a smaller space? As our grafted trees

surpassed waist height, it occurred to me that if I want branching to

begin relatively close to the ground, I might as well break the apical

dominance now rather than waiting until this winter to begin

pruning. The photo to the left shows what happens a couple of

weeks after snipping the top off one of the whips --- new branches begin

to form in the leaf axils of the top three leaves or so.

What next? The

photos above show an apple on MM111 rootstock that is several years

older, and also several weeks further along in its top-snipping

adventure. As you can see, I've tied down all but one of the new

branches so the tree will once again enjoy apical dominance while

turning the horizontal twigs into scaffolds. On a vigorous tree

like this one, I've managed to snip the top off the tree twice this year

(if I recall correctly), building two whorls of scaffolds in one

summer.

I doubt our little

grafted trees will put out much more growth this summer, but hopefully

they'll sink at least a little energy into the new branches. If

all goes as planned, when I transplant them to their new homes this

winter, they'll be a bit further along than the typical one-year-old

whip.

What's the best way to store

a year's worth of harvested onions?

We like to use old citrus

bags and sort out the damaged ones to be used first.

The

hypothesis I often see put forth by the permaculture community is that

you can use weeds to discover imbalances in your soil. When I finally tracked down the best book on the subject, though, I was disappointed.

Since then, I've come to my own conclusions --- problematic weeds are

an indicator of issues with your management strategy, not necessarily of

problems with the ground underfoot.

The

hypothesis I often see put forth by the permaculture community is that

you can use weeds to discover imbalances in your soil. When I finally tracked down the best book on the subject, though, I was disappointed.

Since then, I've come to my own conclusions --- problematic weeds are

an indicator of issues with your management strategy, not necessarily of

problems with the ground underfoot.

Since I tweak my

gardening techniques every year, it's no surprise that our worst weeds

change with the times. This year's doozy is a plant that I used to

consider barely noticeable --- ground ivy (Glechoma hederacea),

which is pictured above. My mother enjoys this plant in her

garden for its bee-friendly spring flowers, its pleasant aroma, and the

way it quickly covers the ground. Unfortunately, ground ivy wreaks

havoc with the mulched areas since it quickly grows amid straw and

makes you lose most of your mulch when you rip it out.

Why is ground ivy

suddenly a big problem for us? I only see the weed in the shadier

parts of my garden, and primarily during wet years, making me think that

there's something about cool, wet conditions that gives ground ivy a

foothold over the grass that's supposed to be colonizing the garden aisles.

I can't do anything about the weather, but I can change a management

technique that I think has been giving the ground ivy a foothold in the

front garden aisles --- weedeating. Until this summer, Mark was in

charge of cutting our "lawn," and he generally opted to weedeat the

front garden rather than mow it since the aisles aren't very

linear. However, close cutting can promote ground ivy over grass,

especially in shady areas. Time to commit to mowing instead of

whacking the front garden grass!

When I first identified

our second troublesome weed of 2014, the book I looked it up in gave it

the appellation "devil's racehorse." I haven't been able to track

down the source of that name, and now call the weed by its more common

names (quickweed, shaggy soldier, Galinsoga quadriradiata).

But the colorful name that originally made me scratch my head makes so

much sense now that I garden --- quickweed will take over a garden

lickety split.

While ground ivy is the

bane of my existence in the shady front garden, quickweed makes its

annoying presence known in the sunny mule garden. I made the

mistake about three years ago of letting a single plant go to seed in a

garden bed there, and the result has been nearly endless handweeding of

every crop I've grown in that spot thereafter. The solution here

is pretty simple --- whatever you do, don't let quickweed go to seed in

your garden!

Have you learned from your garden weeds? If so, which ones taught you memorable lessons?

There's still no sign of the egg

eating snake. I think we

ran him off.

Looking at other snare poles

online prompted me to add a top bolt to ours.

I also tied a knot at the

other end so it all stays together.

As I peered at our hazelnut bush yesterday morning, I reached out to touch one of the developing fruits...and it fell into my hand. Time to harvest!

Unlike most fruits,

hazelnuts are nearly impossible to see on the bush since they're

surrounded by leaf-like husks. So I opted for the lazy harvest

approach --- I carefully shook a branch, watched to see if anything fell

off, and then picked up the nut that had dropped. I could tell

that at least one of the nuts wasn't yet ready to harvest using the

shake method, so I'll go back around and try again next week.

This

is the first year we've gotten anything from our bush, so the harvest

was small --- five tiny nuts. I took them out of their hulls and

will let them cure for a week or two before tasting. The big

question is --- how thick is the shell and how big is the kernel

inside? The bush in question came from Arbor Day's breeding campaign, when folks were just starting to hybridize American and European hazelnuts

in an attempt to combine the blight-resistance of the former and the

large kernel and thin shell of the latter. Stay tuned for the big

reveal....

This

is the first year we've gotten anything from our bush, so the harvest

was small --- five tiny nuts. I took them out of their hulls and

will let them cure for a week or two before tasting. The big

question is --- how thick is the shell and how big is the kernel

inside? The bush in question came from Arbor Day's breeding campaign, when folks were just starting to hybridize American and European hazelnuts

in an attempt to combine the blight-resistance of the former and the

large kernel and thin shell of the latter. Stay tuned for the big

reveal....

(Yes, I am nuts to be so invested in...nuts....)

Our total butternut

squash harvest this year

was 27.

We like to get them nice and

clean before storing

them for the Winter.

I put it off and put it

off and put it off, but eventually the time came to try our hands once

again at killing (and plucking) ducks. By waiting so long, I hoped

that all of the ducks would be done molting (which was true for two of

the three ducks we processed this week). Plus, once September

hits, the garden year is starting to wind down (although there's still

plenty to do), so stealing a morning for poultry butchering seems more

feasible.

You may recall that, last time around, I ended up skinning our duck rather than plucking.

Since then, I accumulated some tips from a reader who prefers to remain

anonymous, the most important of which was --- try heating the scalding

water all the way to boiling rather than stopping at the recommended

temperature. Sure enough, boiling water (and lack of pin feathers)

changed duck plucking from utterly impossible to merely tedious.

We included a generous squirt of dish fluid in the water, roughed up the

duck's feathers while dunking the duck, and then let the duck sit for

several minutes in the hot liquid. This was still insufficient to

allow us to use a power plucker

to remove feathers, but we did manage to kill, pluck, and dress that

duck in 45 man-minutes --- not great by chicken standards, but feasible.

When the time came to

move to duck two, though, I decided to try dry plucking. Damp down

quickly coated my fingers while plucking duck one, and the down was

much more annoying to work around than wet chicken feathers. So I

pulled out handfuls of down before dunking the duck and found that the

down was much more pleasant (if no faster) to remove when dry.

(This method would also have allowed me to save the down for stuffing,

although I was too focused on experimenting with plucking techniques to

do so this time around.) The wing and tail feathers were too tough

to remove dry, though, so I dunked the dunk in the boiling water before

moving on to these larger feathers. The result was a duck

processed in 50 man-minutes, but resulting in a much cleaner carcass

than I managed with duck one.

Duck three was the one

with pin feathers, and I don't want to write about that pain and

suffering here. Ack! I survived (and the duck, obviously,

didn't).

Anyway, to cut a long

story short, my conclusion is --- dry plucking is a little slower than

wet plucking but is much more pleasant. And, whatever it takes,

wait until those ducks stop molting before butchering!

We continue to be impressed

with the Oregon

battery powered chainsaw.

It took about 50 minutes for

Anna and me to cut up some tree limbs.

The charge indicator

was at the halfway point when we started, which means the battery time

is close to 2 hours depending on how much stopping you do between cuts.

It still had some juice left when the indicator display was at zero and

that's when we stopped.

How do you know when your black-soldier-fly bin

is fully colonized? Keep stuffing kitchen scraps in, and pay

attention to how quickly the contents decline in size. At first,

it'll be a bit like a compost pile --- wilting and general decomposition

will reduce your scraps' volume down a bit, allowing you to add more a

week or so later. Then, suddenly, your fly larvae get on the job

and the voracious grubs eat the contents in mere days.

How do you know when your black-soldier-fly bin

is fully colonized? Keep stuffing kitchen scraps in, and pay

attention to how quickly the contents decline in size. At first,

it'll be a bit like a compost pile --- wilting and general decomposition

will reduce your scraps' volume down a bit, allowing you to add more a

week or so later. Then, suddenly, your fly larvae get on the job

and the voracious grubs eat the contents in mere days.

I'll be posting over on our chicken blog

next week about what we're feeding our black soldier flies, and about

our first trial of offering the pupae to our chickens. But I

thought you'd like to see a few photos of the bin in action in the

meantime.

There are now hundreds of grubs of various sizes visible through the walls of the bin, a clear sign that the few larvae I added out of the yard, plus the batch of eggs we purchased, aren't the only source of larvae.

Not that I'd need that information, since I caught a female black

soldier fly in the act of laying her eggs on an onion skin. No o ne

seems interested in laying in the cardboard strips on the top of the

bin, but the cycle of life is definitely working anyway. I've also

seen a lot of yellow soldier flies buzzing around, presumably adding their offspring to the festival.

ne

seems interested in laying in the cardboard strips on the top of the

bin, but the cycle of life is definitely working anyway. I've also

seen a lot of yellow soldier flies buzzing around, presumably adding their offspring to the festival.

I love it when

experiments like this just work, with nearly no effort on our

part. Woohoo for a thriving black-soldier-fly bin!

We were eating figs

this time last year, but Winter

damage slowed things down.

I'm guessing it's still going

to be another week or two before the first one ripens.

Some of you may be wondering if it's time effective to cut up the little branches Mark mentioned in a previous post for firewood. It does take a lot longer per Btu to cut small-diameter firewood, but these branches are perfect for short-lived fires during the shoulder season

(and you get some time back since they don't need to be split).

And, as Mark pointed out to me while we worked, this kind of wood is

very available for just about everyone since branches are often being

hauled away to the dump or to be burned even if you live in the

city. In our rural setting, the tops leftover from our previous

firewood sessions would just rot down to humus if we don't harvest the

wood.

In

the past, we haven't cut much of this small-diameter firewood, though,

because it feels pretty inefficient when using a gas-powered

chainsaw. This is where the battery-powered saw

really shines. Since the saw's not using any energy except when

you're cutting, the operation is quiet (and fun!) and you don't feel

like you're burning more fuel than you're creating. (Do be sure to

build a firewood guide,

though, and to have one person hold the branch while the other

cuts. Mark thinks the battery saw is a little grabby, so you have

to use precautions when cutting small branches.)

In

the past, we haven't cut much of this small-diameter firewood, though,

because it feels pretty inefficient when using a gas-powered

chainsaw. This is where the battery-powered saw

really shines. Since the saw's not using any energy except when

you're cutting, the operation is quiet (and fun!) and you don't feel

like you're burning more fuel than you're creating. (Do be sure to

build a firewood guide,

though, and to have one person hold the branch while the other

cuts. Mark thinks the battery saw is a little grabby, so you have

to use precautions when cutting small branches.)

That said, I think next

week it's time to really put our review saw through its paces. So

stay tuned for the third test --- whether a battery-powered chainsaw can

fell a two-foot-diameter tree.

Dried tomatoes are easy with our 9 tray Excalibur dryer with timer.

Long-time readers will know I've been dreaming about milk goats for years. But Mark has been adamantly opposed, and we don't ever embark on projects when one partner is unwilling.

Long-time readers will know I've been dreaming about milk goats for years. But Mark has been adamantly opposed, and we don't ever embark on projects when one partner is unwilling.

So, imagine my surprise when I teased Mark that Kayla

and I were getting a goat together...and he said I could have

one all for myself. Turns out, my adamant opposition to Mark's purchase of a

self-propelled, string mower is equivalent to his adamant opposition of

my purchase of a milk goat. "If you let me get a mower, then I'll

let you get a goat," Mark said. "I'll even help you milk

it." Much kissing and hugging ensued.

After rereading my goat book,

I decided that a mutt is probably our best option to learn on, and I

found the three or four year old girl pictured here on

craigslist. She's semi-dwarf, a combination of Saanen and Nigerian

with a bit of Nubian thrown in, and her mixed descent makes her quite

affordable ($125). She's been raised in a setting much like we

want to throw her into, and is reputed to give birth easily, to be

parasite resistant, and to have been giving a quart of milk a day while

feeding her kids on brush alone. Her owner is currently drying her

up and breeding her to a Saanen/Nigerian buck, and is willing to hold

onto her for a month while we get our act together (in the process

ensuring that the doe is really pregnant). Add in a wether (to

keep her company, source not yet decided), and this might be an easy way

to see whether we like goats during the winter, then to jump into

milking next spring.

After rereading my goat book,

I decided that a mutt is probably our best option to learn on, and I

found the three or four year old girl pictured here on

craigslist. She's semi-dwarf, a combination of Saanen and Nigerian

with a bit of Nubian thrown in, and her mixed descent makes her quite

affordable ($125). She's been raised in a setting much like we

want to throw her into, and is reputed to give birth easily, to be

parasite resistant, and to have been giving a quart of milk a day while

feeding her kids on brush alone. Her owner is currently drying her

up and breeding her to a Saanen/Nigerian buck, and is willing to hold

onto her for a month while we get our act together (in the process

ensuring that the doe is really pregnant). Add in a wether (to

keep her company, source not yet decided), and this might be an easy way

to see whether we like goats during the winter, then to jump into

milking next spring.

It's a bit daunting to

make a commitment to branch out into larger livestock, so we haven't

decided quite yet. But I'd say we're 80% of the way there...and I let Mark

order his mower.

How do we store our dried

tomatoes?

1. Follow steps of Hollywood

Sun Dried Tomatoes.

2. Put in containers suitable

for freezing, label and store in freezer.

3. Resist the urge to eat

them all at one time, but instead wait until you need a dose of

sunshine when the short Winter days can sometimes get the better of us.

Original plan: Keep a mixed flock of ducks and chickens this winter to see whether it's true that waterfowl are better winter layers than land fowl.

Midsummer plan: Get rid of the ducks ASAP!

Late summer plan: Slaughter all the male ducks

(meaning we won't be raising waterfowl again next year), but keep the

girls for winter layers. Now that I treat the ducks like chickens (only giving them open water as a treat once a week

--- after all, it rains nearly every day), they're much easier to

handle. Sure, ducks don't forage as well as chickens on a

hillside, but the experiment is still worthy of carrying to its natural

conclusion...

Late summer plan: Slaughter all the male ducks

(meaning we won't be raising waterfowl again next year), but keep the

girls for winter layers. Now that I treat the ducks like chickens (only giving them open water as a treat once a week

--- after all, it rains nearly every day), they're much easier to

handle. Sure, ducks don't forage as well as chickens on a

hillside, but the experiment is still worthy of carrying to its natural

conclusion...

...Especially since the

ducks are starting to lay! I found the first egg (slightly dirty

because we haven't built floor-level nest boxes yet) on Thursday and we

tasted it on Friday. The consensus was --- it tastes like an

egg. (By carefully eating bites of duck and chicken eggs side by

side, I could

detect a very slightly richer flavor in the former, but the difference

was very minor.) I'll be sure to report laying stats in a few

months once day length is at winter levels.

After a week of drying and a few hours in the dehydrator with the tomatoes, our first hazelnuts were ready for a taste test.

The shell-to-nut ratio was perfect and the roasted hazelnuts had a delicious flavor reminiscent of buttered popcorn.

Anna told me I have twelve months to come up with a powered nutcracker for next year's (hopefully) much larger crop.

I

had forgotten how poor our soil used to be until I opened up some new

garden areas this year. Without frequent applications of manure,

straw, and cover crops

to build the organic-matter levels, our native soil is a cloddy mass of

pale silty-clay. Unsurprisingly, many crops failed to thrive in

this new ground...but others did even better. I figured you might

like hearing about the good and the bad in case you have poor-soil areas

of your own that you want to put into production now rather than

waiting until years of TLC turn your topsoil black.

I

had forgotten how poor our soil used to be until I opened up some new

garden areas this year. Without frequent applications of manure,

straw, and cover crops

to build the organic-matter levels, our native soil is a cloddy mass of

pale silty-clay. Unsurprisingly, many crops failed to thrive in

this new ground...but others did even better. I figured you might

like hearing about the good and the bad in case you have poor-soil areas

of your own that you want to put into production now rather than

waiting until years of TLC turn your topsoil black.

Who failed the

test? Carrots and butternuts both grew in the new ground, but

produced fruits and roots that were half the size of what I'm used

to. In the photo, the butternut on the right comes from an older

bed while the one on the left is representative of the squash we

harvested from the new bed. Total yield in the new ground was

about a third to a quarter of what I'd expect elsewhere for these two

crops.

On the other hand,

sunflowers and sweet potatoes seemed to grow even better in the poor

soil. In the top photo, the potatoes in the basket all came from a

similar square footage (but from richer soil) as the huge number of

potatoes cleaned and stacked on the porch (that came from poorer

soil). Keep in mind that I did take the time to dig these new patches,

scooping the topsoil out of the aisles to double the height of the

growing beds (and I usually don't dig or till our established beds at

all). So, the thrivers may be responding to the fluffiness and

quick breakdown of organic matter into nitrogen that you find in

recently churned ground. Or maybe they just like low organic

matter and nutrient levels.

To paraphrase Tolstoy,

happy soils are all alike; every unhappy soil is unhappy in its own

way. So you might find that the crops that thrive in our poor soil

don't do so well in yours. Still, I'd be curious to hear from our

readers who have kept an eye on crops growing in good and poor parts of

their gardens. Which plants like and dislike the bad ground?

The Oregon

battery powered chainsaw has a nice self sharpening feature.

You pull up on the red lever

while it's running and a stone sharpens the chain.

It seems to work well as long

as you clear the area of stray wood chips.

The decision has been made! I mailed in our down-payment, and we'll pick up our nanny goat

in October. In the meantime, we've got lots to do and to

decide. For example, we're still not 100% sure whether we want to

start with the lowest-work option (one doe and one  wether)

or whether, since we're going to have two goats anyway, we might as

well bite the bullet and find another girl. On the plus side, two

girls would make us more likely to have enough milk to experiment with

cheese; on the minus side, two girls would mean double the kids to

manage in the spring and double the milking chores. At the moment,

we've resolved to let serendipity decide --- if another milk goat turns

up on craigslist in the next month that seems like a good fit for our

homestead, we'll go for it; otherwise, we'll find a cheap wether

somewhere to keep our first find company.

wether)

or whether, since we're going to have two goats anyway, we might as

well bite the bullet and find another girl. On the plus side, two

girls would make us more likely to have enough milk to experiment with

cheese; on the minus side, two girls would mean double the kids to

manage in the spring and double the milking chores. At the moment,

we've resolved to let serendipity decide --- if another milk goat turns

up on craigslist in the next month that seems like a good fit for our

homestead, we'll go for it; otherwise, we'll find a cheap wether

somewhere to keep our first find company.

Since we won't be milking

at first, we can save half of our prep chores for later, but there's

still lots to do. It's time to finally add gates to our

starplate pastures, time to protect the one tree I care about that's

still growing there, and time to convert the starplate coop

into the starplate goat barn. The last task involves splitting

the building into stalls so the kids can be kept separate from the

mother(s) in the spring, adding food and water stations, and perhaps

making a food-storage room (to replace the metal garbage can we used

with chickens). My to-buy list currently includes hoof-trimming

supplies, loose minerals and maybe boluses for copper and kelp for

additional nutrition, leashes and breakaway collars, and a bit of feed

(although we're hoping to raise the goats on brush and weeds as much as

possible). And that doesn't even count the milking, kidding, and

disbudding supplies we'll need to think about before spring --- I guess

my goat endeavor is going to cost just as much as Mark's high-end mower.

Then there are the less

essential preparations that just make me happy. I decided to dry

some sweet-corn stalks in a shock to see if the goats will enjoy them as

a midwinter snack, and I also draped the sweet potato vines across the

porch for a similar reason. Too bad we've passed the time to plant

carrots and mangels --- next year!

We chose an 18

gallon Rubbermaid storage box for our new duck nest box.

The bottom 2x4 extends out 6

inches past the edge to increase stability and provide a sturdy ledge

for the ducks to step on and over to get into the box.

Purchase price was 9 dollars

and it claims to be crack and weather resistant.

The first half of

September is a surprisingly busy time in our garden. Why the

surprise? Because most people are letting their summer vegetables

drift into weeds at this time of year...but I'm opening up areas as fast

as I can to plant oilseed radishes and oats as cover crops.

My method means that our farm's soil gets richer every year while weed

pressure gets lower and lower...but it does keep me hopping.

If

I didn't have an oat deadline to consider (September 15), then I'd let

beds of dwindling summer squash, cucumbers, bush beans, and mung beans

sit around and dribble in a bit more food. Instead, I rip them out

and plant cover crops. Similarly, I look at larger plants with a

stern eye --- will I lose much by raking back the mulch around declining

tomatoes and sowing oats to hold the soil over the winter?

Probably not, so oats it is!

If

I didn't have an oat deadline to consider (September 15), then I'd let

beds of dwindling summer squash, cucumbers, bush beans, and mung beans

sit around and dribble in a bit more food. Instead, I rip them out

and plant cover crops. Similarly, I look at larger plants with a

stern eye --- will I lose much by raking back the mulch around declining

tomatoes and sowing oats to hold the soil over the winter?

Probably not, so oats it is!

I've read that some

old-timey farmers used to plant oats around their strawberry plants at

this time of year, growing mulch in place for the spring. I've

always been afraid of losing productivity in my favorite fruit, but I

opted to experiment with half of one bed this fall. Similarly, I

sowed oats beyond the canopy spread in our blueberry rows, hoping for a

bit of extra organic matter with little effort on my part.

Do I get to rest on my

laurels once the cover-crop deadline is past? Nope --- then it

will be time to weed the fall seedlings and plant a bunch of beds of

garlic. But I can definitely feel the garden locomotive slowing

down as it prepares to pull into the station and rest for the winter.

We decided the duck nest

box should be outside the coop for easy egg access.

I put a golf ball in the nest

to encourage the curious ones.

I think I may have found my new favorite sweet pepper. Too bad it's a hybrid!

I bought a packet of Lunchbox peppers from Johnny's this spring on a whim. We've been pretty happy growing pimento-type peppers

since the smaller fruits ripen up before frost even if I don't start

the plants inside ultra-early. But my heirloom variety started to

decline in vigor after a few years, perhaps because I didn't grow enough

plants to keep the gene bank deep.

Anyway,

to cut a long story short, I chose two new varieties this spring,

selecting from among peppers with the fastest days-to-maturity.

The pimento-type pepper (Round of Hungary) that I tried this time around

did

ripen its first fruit just as quickly as the Lunchbox peppers, but the

former has been providing approximiately one red pepper per week from

three plants while the latter is overflowing with goodness from a

similar size planting. Even after adding peppers to our salad all

week, I still ended up with a bowful in need of preservation.

Anyway,

to cut a long story short, I chose two new varieties this spring,

selecting from among peppers with the fastest days-to-maturity.

The pimento-type pepper (Round of Hungary) that I tried this time around

did

ripen its first fruit just as quickly as the Lunchbox peppers, but the

former has been providing approximiately one red pepper per week from

three plants while the latter is overflowing with goodness from a

similar size planting. Even after adding peppers to our salad all

week, I still ended up with a bowful in need of preservation.

Lunchbox isn't really a

variety but a mix of three different types of pepper. Luckily for

me, most of my plants turned out to be the red type, since that one is

much more vigorous than the yellow and orange. The plants and

fruits look like hot peppers, but the peppers are sweet and delicious

(although with slightly thinner flesh than you'd expect in larger

peppers).

I wonder what I'd get if I saved the seeds of my Lunchbox peppers and tried the hybrid offspring in next year's garden?

The small,

multicolored sunflowers

were ready for harvesting today.

Most of our sunflower crop

still needs a few more weeks.

I suspect we'll be making our own upgraded black-soldier-fly bin next year. The bin we bought

is an awesome introduction...but I keep overfilling it since I have 50

pounds of moldy chicken feed to work my way through. Last week,

the mass of decomposing chicken feed heated up so much that white larvae

crawled off, and even when I'm more careful, I feel like the bin is

getting waterlogged and full of castings when I add half a gallon of

chicken feed (soaked to become about a gallon) per week.

I suspect we'll be making our own upgraded black-soldier-fly bin next year. The bin we bought

is an awesome introduction...but I keep overfilling it since I have 50

pounds of moldy chicken feed to work my way through. Last week,

the mass of decomposing chicken feed heated up so much that white larvae

crawled off, and even when I'm more careful, I feel like the bin is

getting waterlogged and full of castings when I add half a gallon of

chicken feed (soaked to become about a gallon) per week.

The photo above shows the

kind of crawl-off I'd rather see --- just the black pupae. This

type of heavy harvest comes about once a week, when I add more chicken

feed and soak the bin contents in the process. On other days, I

instead get perhaps a couple dozen pupae, still enough to make our

tractored hens happy. But more pupae is definitely better, and I

now understand why you might want to have a 10- or 20-gallon bin.

Or perhaps to have several smaller bins (although I'd still want them

all to be located right outside the back door where it's easy to put in

scraps and to take out pupae for the chickens).

Meanwhile, there's at

least one feature of our current bin that I don't feel is working as it

should. The velcro strip around the top of the bin, meant to keep

pupae from escaping without crawling into the collection bin, has a gap

in each corner just big enough for pupae to wriggle through. I

keep finding drowned pupae in the ant-trap moat around the bin, which makes me sad.

While I'm writing a wish

list of future changes, I'd like to drill holes in the top of the

collection jar just large enough for an adult fly to escape, but too

small for a pupa to get  through.

Three times now, I've seen adult flies trapped in the collection bin,

once because I left a pupa inside too long and it hatched, but twice

because the flies went to lay their eggs in the main bin and ended up

exiting in a different direction.

through.

Three times now, I've seen adult flies trapped in the collection bin,

once because I left a pupa inside too long and it hatched, but twice

because the flies went to lay their eggs in the main bin and ended up

exiting in a different direction.

That said, our bin is

providing a healthy dose of animal protein for our flock nearly every

day, and the number of larvae inside seems to keep growing. I

caught one fly laying eggs inside the handle of the drainpipe last week

(which I transferred to the bin), but I suspect there have been many

other sets of eggs laid without my notice. I'm definitely ready to

say that Mark is right --- black soldier flies are a good fit for our

farm. Now we just need to work the kinks out of the operation.

The new self propelled

trimmer mower showed up a week early.

Her first day on the job will

be Monday if it doesn't rain.

I wish I could give you a

solid recipe for the paste I made Saturday because it's based on beans

but even Mark found it delicious. (Plus, all of the ingredients

except the olive oil, salt, pepper, and walnuts are ripe on the farm

right now). But I mostly just put in some of this and some of that

until the paste tasted right. Here's my best guess on

proportions:

- 1 heaping cup of scarlet runner beans in the lima-bean stage, pods removed

- 1 cup of homemade chicken broth

- 2 small red peppers, minced

- 4 small sprigs of fresh thyme

- 1 large clove of garlic, minced

- salt and pepper

- olive oil (about 0.25 cups, enough to get the consistency hummusy)

- 1 large handful of dried tomatoes, on the soft side rather than thoroughly dried

- 1 small handful of walnuts

Cook

the beans, broth, peppers, thyme, and garlic in the chicken broth for

about 20 minutes, until the beans are soft. (Unfortunately, the

brilliant color goes away and the beans turn gray at this point.)

Cool, then puree the mixture in the food processor with the other

ingredients. If you're smart, you'll blend up the tomatoes and

walnuts first, but they worked out okay added in later.

Cook

the beans, broth, peppers, thyme, and garlic in the chicken broth for

about 20 minutes, until the beans are soft. (Unfortunately, the

brilliant color goes away and the beans turn gray at this point.)

Cool, then puree the mixture in the food processor with the other

ingredients. If you're smart, you'll blend up the tomatoes and

walnuts first, but they worked out okay added in later.

Serving suggestion:

Make little tacos out of Malabar spinach leaves filled with bean paste,

chopped arugula, and thinly sliced tomatoes, red peppers, and edible-pod

peas. These can be eaten with one hand like a soft taco if you're

careful not to overfill. While this serving method is a bit

time-consuming to prepare, it's pretty and fun for a special

occasion! Happy birthday, farm!

Our old

ratchet straps are 5 years old and rusty.

My new method is to store the

new one in a ziploc bag to protect it from the elements.

One

of Mom's friends gave her this unripe passionflower fruit, which she

then passed along to me. Since the maypop is edible and the vine

is often included in permaculture texts, I might see if the fruit had

gotten far enough along on the vine to produce viable seeds.

One

of Mom's friends gave her this unripe passionflower fruit, which she

then passed along to me. Since the maypop is edible and the vine

is often included in permaculture texts, I might see if the fruit had

gotten far enough along on the vine to produce viable seeds.

I'm always up for growing an experimental species, even though I have a

feeling that, if maypops tasted all that good, I would have eaten one

before since they're native to our region and since I grew up amid

foragers. In

the meantime, I'd be curious to hear from those of you who have grown

passionflowers in your garden. I know the blossoms are beautiful,

but is the fruit worth eating?

We put together the new Swisher

trimmer mower today.

It feels like more than twice

the cutting power of our previous mower.

I'm still learning how to use

it. When the self propelled mechanism is engaged I found myself

struggling to keep up with its pace. It's better to just pump the

engagement lever a few seconds at a time to let the machine do most of

the work.

I don't usually cross-promote books here if we publish them but they're written by someone else. But our publishing wing

has become the majority of our bread and butter lately, so I hope you

don't mind the occasional plug...especially if it comes with a

homesteading-related giveaway!

I don't usually cross-promote books here if we publish them but they're written by someone else. But our publishing wing

has become the majority of our bread and butter lately, so I hope you

don't mind the occasional plug...especially if it comes with a

homesteading-related giveaway!

I'll start with the part

you're probably most interested in --- the free stuff! I rooted a

cutting from my father's Brown Turkey fig this year, and the sapling is

looking for a zone-7 or warmer home. Daddy is picking a gallon of

figs a day from this little tree's mother, and says that fig pie is his

current favorite way to consume the fruit. As long as you don't

live in a cold climate, fig trees require nearly no care, and can be fit

into an area about eight feet in diameter (although I hear they get

much larger in California). Why not enter to win your own no-work

fruit tree?

What if you live up

north? Don't worry, I'll swap out your prize for something more

appropriate. You might prefer cuttings from my Chicago hardy fig --- these are easy to root and will produce fruit (with a little care) up through zone 6. However, if even that is  too

tropical for your tastes, you can choose either a medley of our

favorite seeds, or a signed copy of one of my (or Aimee's) books.

And, if a northerner wins the prize, I'll pick a second winner to give

the fig tree to!

too

tropical for your tastes, you can choose either a medley of our

favorite seeds, or a signed copy of one of my (or Aimee's) books.

And, if a northerner wins the prize, I'll pick a second winner to give

the fig tree to!

How do you enter the

giveaway? Just plug our books using the widget below. Aimee

has several new books out now or soon --- you've probably heard me

mention Shiftless, which has already sold over 3,000 copies and will be an audio book within a few weeks; Burgling the Dragon is available at a special preorder price of 99 cents through September 30; and Aimee's short story Flight of the Billionaire's Sister will make you itch to read her newest novel, slated to release in November or December. Oh, and did I mention that her short-story collection

is free on Amazon today? Once books are out of the preorder

period, you can also borrow nearly all of her books (and mine too!)

using Amazon Prime or Kindle Unlimited, so why not check some out?

Thanks in advance for reading and for spreading the word!

How is the new Swisher

trimmer mower on very steep hills?

Like a dream!

The above hill took a lot of

effort with our blade mower, but today was easy once I got the hang of

letting the machine drive it up the hill. Gravity takes over when you

release the engagement lever for the downward portion.

Autumn weather arrived

this past weekend and the long-range forecast suggests it may stick

around. Luckily, we're mostly in gravy mode in the garden ---

we've packed away enough vegetables to last us for the winter, and are

just enjoying eating the rest of the harvest (with occasional bouts of

tomato drying or pepper freezing for variety later in the  year).

The figs are still dragging their feet and refusing to ripen, but the

blueberries are winding down and the red raspberries are in full swing.

year).

The figs are still dragging their feet and refusing to ripen, but the

blueberries are winding down and the red raspberries are in full swing.

Mom asked what I planned to do if we get an early frost and I said that,

really, we're ready. Not that I want summer to end, but when

freezing temperatures are forecast, we'll just let them happen.

One experiment hasn't quite reached it conclusion --- the sorghum plants

I seeded at the beginning of July. Just as our current cool spell

came in, the plants shot up even higher and pushed out flower heads,

which may or may not have time to turn into seeds before the

frost. I took the photo to the left with the zoom feature since

these heads are way out of my reach, making our tall sunflowers look

like midgets in comparison.

Cooler weather also reminds me that it's time to pay attention to the bees. I did a second varroa-mite count

last weekend and was extremely pleased with the results --- 2.5 mites

per day in the daughter hive and 3.5 mites per day in the mother

hive. Our Texas bees continue to be worth their weight in gold.

But are they worth their

weight in honey? Now that the humidity has dropped below 90%, I'm

hoping for a sunny and moderately warm afternoon to harvest honey from

the mother hive. (The daughter will have the empty bottom box

removed but will otherwise be left alone.) Maybe Friday?

Why are we moving this ancient freezer?

To have a rodent proof

container to store goat feed near the Star Plate coop.

Yes...Anna helped push once

she finished taking pictures.

Several of you asked (or warned) about fencing for our upcoming goats.

I started to write a long post in reply about my complicated plans on

that front, but it seemed a little silly to theorize when I'll be able

to report on our trial and error in less than a month. However,

there is a goat-related conundrum we're currently trying to solve --- water.

We plan to house our new goats in our starplate coop,

but the structure is about 250 feet from the closest water source and

up a relatively steep hill. It was a bit wearying to carry a

five-gallon bucket to the coop once a week over the summer, so I can

only imagine how old the chore will get for goats (who presumably drink

more than chickens) during the winter months.

We've

come up with several potential summer solutions, but winter ones will

require more industry. We can finish working up the gutters and rain-barrel system,

but the spigot is bound to freeze during the winter whether or not the

tank is big enough prevent the whole thing from freezing solid.

Similarly, we could pump water from the creek

into our IBC tanks, but our creek-line isn't buried and only sometimes

runs in the winter (and we'd still have to deal with a frozen spigot).

We've

come up with several potential summer solutions, but winter ones will

require more industry. We can finish working up the gutters and rain-barrel system,

but the spigot is bound to freeze during the winter whether or not the

tank is big enough prevent the whole thing from freezing solid.

Similarly, we could pump water from the creek

into our IBC tanks, but our creek-line isn't buried and only sometimes

runs in the winter (and we'd still have to deal with a frozen spigot).

Gene Logsdon posted a few

weeks ago about burying rain barrels to make mini-cisterns, and I think

the idea has potential in our starplate pasture. I love to dig,

especially at this time of year when garden work is winding down, and

the starplate earth is much lighter than the stuff in our core

homestead. Plus, Mark brought a hand-pump home from the hardware

store many moons ago, thinking we might need it if the world came to an

end, and we could use that to get water out of the buried rain barrel in

order to hydrate our herd.

But I have a feeling that

I'm missing something even more obvious. Ideas? How would

you water goats located far enough away from the house that extension

cords don't really reach?

The Oregon

battery powered chainsaw

made quick work of this large Box Elder.

Some of it is already rotten,

but most of it will make good kindling material.

Every year, we seed six

plantings of sweet corn, which provide near-continuous availability of

the treat over most of the summer. And every year, one of those

plantings gets away from us.

Mark

and I are such connoisseurs of sweet corn that we only eat the grain at

its peak. I start the water boiling at the same time I head out

to the garden to pick and shuck the ears, then I drop the corn in the

water and turn each ear once, removing as soon as the color changes from

pale to bright yellow, a process that takes mere seconds. The

result is corn so sweet, Lucy begs for the cobs, which she completely

consumes.

Mark

and I are such connoisseurs of sweet corn that we only eat the grain at

its peak. I start the water boiling at the same time I head out

to the garden to pick and shuck the ears, then I drop the corn in the

water and turn each ear once, removing as soon as the color changes from

pale to bright yellow, a process that takes mere seconds. The

result is corn so sweet, Lucy begs for the cobs, which she completely

consumes.

But if I miss that

peak-taste window and our corn starts to turn starchy...then Lucy, Mark,

and I all turn up our noses. Instead, I shuck the corn and put it

on our drying racks for winter animal treats. In the past, I've offered dried sweet corn to our chickens, but this year, I think the ears will go to the goats.

It took me a while to figure

out how to make the Clarity

anti-fog wipes stretch as far as possible.

Store the treated glasses in

an airtight container to maximize the hydrophobic effect.

It

seems like there's never as much honey in my Warre hives as I think

there is. I went out to rob the mother hive's top box on a sunny

afternoon this week...and found that there was nothing to steal.

The fourth box was empty, the box below contained a good bit of honey

but also some capped brood (meaning it had to be left alone), I didn't

dig into the third box (but I hope it's also full of honey and brood),

and the bottom box consists of partially drawn comb (photo above).

So, instead of stealing honey, I took away the empty top box, and will

probably remove the bottom box later as well.

It

seems like there's never as much honey in my Warre hives as I think

there is. I went out to rob the mother hive's top box on a sunny

afternoon this week...and found that there was nothing to steal.

The fourth box was empty, the box below contained a good bit of honey

but also some capped brood (meaning it had to be left alone), I didn't

dig into the third box (but I hope it's also full of honey and brood),

and the bottom box consists of partially drawn comb (photo above).

So, instead of stealing honey, I took away the empty top box, and will

probably remove the bottom box later as well.

Of course, you don't really expect to harvest honey if you split a hive,

so just having enough bees and stores to get the mother hive through

the winter is good. Luckily, two boxes full of brood and honey are

supposed to be enough for a Warre hive, according to the experts,

unless you live in the far north. Since a Warre hive box is only

the size of a shallow super, that seems counterintuitive to those

of us who started with Langstroth hives, but I'm willing to bow to

wiser beekeepers, who report that the superior insulating ability of

the Warre hive allows the bees to thrive with fewer stores.

Unfortunately, the

daughter hive is also not doing as well as I'd hoped, and they may

actually be in trouble. I removed the third box (empty) and

finally got a look in the second  box,

which turns out to be full of drawn comb but absolutely empty of life

(photo to the left). That means I need to feed fast to get the

bees through the winter.

box,

which turns out to be full of drawn comb but absolutely empty of life

(photo to the left). That means I need to feed fast to get the

bees through the winter.

More troublesome was the

presence of wax moth larvae under the quilt when I peeled back the final

piece of burlap. Wax moths are usually a sign of a hive in

decline, since they mean the colony isn't strong enough to patrol their

entire territory. I hope that feeding the bees will be enough to

let them bulk up and defeat the moths, but realize that there's a good

chance the daughter hive might perish over the winter.

While I'm thrilled that my hives seem to be bypassing varroa mites without chemicals,

I'm still not sold on Warre hives being the way to go --- I'd like to

harvest some honey sooner rather than later. Unfortunately, my

past experience has been Langstroth hives with conventional bees that

produced honey but perished without chemicals or Warre hives with

chemical-free bees that don't produce honey but do survive in a natural

setting. Time to shake things up next year, maybe trying out

chemical-free bees in a Langstroth hive on foundationless frames to see

if those would give us a harvest in a natural setting. I'd love to

hear from other beekeepers who have figured the puzzle out, in case you

want to save me a few more years of trial and error!

I've added bar oil to the Oregon

battery powered chainsaw twice now.

Both times resulted in some

overspill, which can be a problem if it drips down and makes contact

with the sharpening stone.

The next time I plan to

refill the original bar oil container it came with first, that way the

amount will be exact and I won't feel like such an amateur.

It

seems a little crazy to have two giveaways running at the same time,

but we're overflowing with fun items at the moment and it seems like we

should share the bounty. You've still got a couple of days to

enter our fig giveaway, but in the meantime, why not also try your luck for a just-released farm memoir?

It

seems a little crazy to have two giveaways running at the same time,

but we're overflowing with fun items at the moment and it seems like we

should share the bounty. You've still got a couple of days to

enter our fig giveaway, but in the meantime, why not also try your luck for a just-released farm memoir?

I reviewed The Call of the Farm a few months ago,

and was surprised to get another copy in the mail last week. It

turns out, the publisher used my blurb in the front of the book (a first

for me!) and sent a more polished copy as a thank-you.

But I don't need two versions of the book, so one lucky reader will take

home this fun farm memoir --- use the widget below to enter! The

entry options are a little different than usual, but email list

subscribers still get an effort-free entry. Thanks for spreading

the word, and I hope you enjoy the book as much as I did!

Unusually busy weekend

around here. I drove myself to town (horrors!). Mark cooked

himself supper without me (extraordinary!). I met one of our blog

readers and a couple dozen of her closest friends and family in the

flesh (hi, Emily in Bristol!). Mom showed off the one-year-old

daughter of our Chicago Hardy fig tree (impressive!). Lost 'seng

hunters wandered into our yard (unusual!). My weather guru warned

of a possible frost Monday night (yikes!).

(Bet you can't add more parentheticals and exclamation points in a 88 word post.)

The instructions say to go

from 4 to 2 strings if the mowing gets bogged down.

Discovered today that our

lawn of weeds cuts faster with just 1 string once you get the proper

cutting height figured out.

I'd like to put in my

order now for a May 2015 with no hard freezes to nip our apple

flowers. Because our high-density trees have grown remarkably over

the last two years (2013 in the top photo, 2014 below), and I suspect they could give us quite a few fruits if the weather holds off.

It's

a bit hard to get the full effect from photos like these, but trust me

--- you feel like you're in a miniature forest when you walk by the row

nowadays. Mark's already talking about snaking the tops of the

taller trees (see left) so they don't grow too far above his reach, and

I'm itching for the leaves to fall so I can set out our second

high-density row with this year's graftlings. I wonder if I'll get as much joy from eating the fruits as I do from watching the trees grow?

It's

a bit hard to get the full effect from photos like these, but trust me

--- you feel like you're in a miniature forest when you walk by the row

nowadays. Mark's already talking about snaking the tops of the

taller trees (see left) so they don't grow too far above his reach, and

I'm itching for the leaves to fall so I can set out our second

high-density row with this year's graftlings. I wonder if I'll get as much joy from eating the fruits as I do from watching the trees grow?

How tall did our sorghum get this year?

Most were close to 9 feet,

but the tallest was a little over 10.

It's the first year we've

grown it. The plan is to see if the chickens will eat the seeds and

save the stalks for our future goat

population.

Our first fig ran nearly three weeks late

this year, ripening up on September 18. Even then, we only had

the one until today, when I hope to bring in enough figs to make it

worth our while to roast

some. Good thing that possible frost passed us by or this would

have been a one-fig year! Instead, with autumn warming back up

through the beginning of October, we may get to enjoy gallons of them.

The

blueberries are finally slowing down, but another row of raspberries is

ripening to take their place. It's a bit odd how our two

plantings of red raspberries act entirely differently even though they

are all clones of one Caroline

plant. The row closer to the north-facing hillside (meaning they

get a lot of shade, even in the summer) ripened up their fall berries

nearly a month before the sunnier row, but the shady berries were

considerably smaller. The berries turning color now are huge and

copious, promising a bowlful per day for our favorite dessert.

The

blueberries are finally slowing down, but another row of raspberries is

ripening to take their place. It's a bit odd how our two

plantings of red raspberries act entirely differently even though they

are all clones of one Caroline

plant. The row closer to the north-facing hillside (meaning they

get a lot of shade, even in the summer) ripened up their fall berries

nearly a month before the sunnier row, but the shady berries were

considerably smaller. The berries turning color now are huge and

copious, promising a bowlful per day for our favorite dessert.

What fruits are you enjoying this week?

The sky

pond has a different look after one year.

It seems to be most popular

with our bee population. They often use the duck weed cover as a safe

place to land when they need a drink.

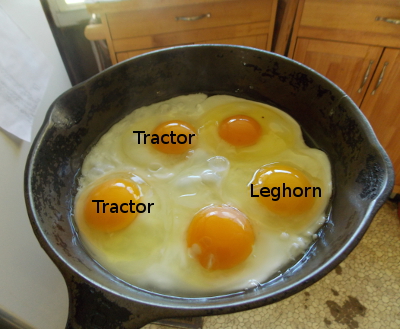

Since we've been averaging about half a cup of black-soldier-fly larvae going to the tractored

hens every day (plus they get all of our food scraps), I decided to run

a color test on yolks from our pasture versus from our tractor. I

hypothesized that the latter would have the most bright-orange yolks

due to all their treats...but I was wrong!

Since we've been averaging about half a cup of black-soldier-fly larvae going to the tractored

hens every day (plus they get all of our food scraps), I decided to run

a color test on yolks from our pasture versus from our tractor. I

hypothesized that the latter would have the most bright-orange yolks

due to all their treats...but I was wrong!

Instead, the orangest yolks came from the pastured hens (although the leghorn

egg was paler --- those flighty critters aren't as keen on scratching

for their dinner). It seems that even a daily offering of insects

and pepper tops isn't enough to make up for the hens' lack of space to

run around.

I should have thrown in a

store-bought egg to make this comparison really perfect, but I can tell

you from past experience that those yolks would be significantly paler

than even the Leghorn eggs. So, yes, you will be improving over

store-bought with a chicken tractor, but for absolutely tip-top eggs,

you need to use rotational pastures and to choose those varieties wisely. Enjoy your orange yolks!

We've been having a problem

with our pet door.

When Huckleberry squeezes

through he rubs against the locking tab and pushes it into a position

that blocks the door from opening back up.

I drilled a hole through the

tab so we could plug a wire through it to keep it open.

One of my favorite features of our black-soldier-fly bin

is the clear plastic, which lets me see exactly what's going on

inside. While this might not be quite as cool as an observation

hive (grimy grubs versus beautiful bees), the transparency does make it

easy to notice how many larvae are working inside. And, this week,

the feature helped me realize that a bunch of black pupae were

congregating in the bottom of the bin.

The

instructions tell you to flood the bin with water once a week to

prevent this exact problem...but I forgot. Luckily, it wasn't too

late to harvest all of those yummy pupae. A couple of hours after

flooding, I dropped by the bin and saw that there were pupae filling the

ant moat

(which I'd luckily forgotten to fill with water as well) since they'd

all tried to crawl out so quickly that there was a traffic jam in the

entrance ramp to the collection bin.

The

instructions tell you to flood the bin with water once a week to

prevent this exact problem...but I forgot. Luckily, it wasn't too

late to harvest all of those yummy pupae. A couple of hours after

flooding, I dropped by the bin and saw that there were pupae filling the

ant moat

(which I'd luckily forgotten to fill with water as well) since they'd

all tried to crawl out so quickly that there was a traffic jam in the

entrance ramp to the collection bin.

Mark helped me collect

all of the escaped pupae, and we ended up with about three pints

worth! In fact, based on how much the contents of the bin dropped

in height after the crawl-off, I suspect we might have lost another pint

of pupae before I noticed the great escape. Luckily, "lost" pupae

will just turn into lots of adults to repopulate the bin, so it's all

good.

The moral of the

story? If you don't keep a close eye on your bin and need to do an

emergency flooding, stand by to prevent escapes!

We had to hand

winch the ATV free today.

A lot easier to pull than a truck!

I think low tire pressure on

one of the rear tires was a contributing factor.

"Anna, I think you've been doing some experimenting with pears on your

homestead, but I couldn't find any recent updates in the archives. Any

luck with your disease-resistant rootstocks, etc.?"

"Anna, I think you've been doing some experimenting with pears on your

homestead, but I couldn't find any recent updates in the archives. Any

luck with your disease-resistant rootstocks, etc.?"--- Jake, whose excellent blog is currently one of my favorites. His writing will definitely be enjoyed by those who love a combination of useful facts, zany humor, and unadulterated geekiness.

Good question,

Jake! I haven't posted much about our pear trees because they're

mostly in the waiting stage at the moment. We originally planted a

Keiffer and an Orient pear

(the latter of which shouldn't be confused with Asian pears), and they

grew quite well...but produced fruits that weren't worth eating.

(Yes, we are snobs. Yes, if you plan to cook with the fruit, these

are probably still quite good varieties.)

So, a year and a half ago, I topworked

the young trees to change them over to new varieties --- Seckel,

Comice, and an unknown variety that is supposed to be similar to

Comice. The two named varieties are reputed to be moderately

susceptible to fireblight, and I have

seen a small amount of damage from that bacteria, although not enough

to really slow down the trees. (The photo above shows the huge

number of new branches the Seckel's central leader has produced during

this growing season alone.) Otherwise, the transformed trees seem

to be immune to problems. Like most pears, our trees grow a mile a

minute and I'm kept busy ripping off watersprouts to ensure that the

pears don't revert back to their original varieties, then training

keeper branches closer to the horizontal so they don't all grow straight

for the sky.

If all goes well, we

should see several fruits on each tree next year, at which point I'll be

able to tell you whether Seckel and Comice live up to their potential

for producing delicious pears that are much less prone to diseases than

apples are. So far, except for the fireblight, our pear trees have

been pristine. Of course, there are apple varieties that are nearly as disease resistant, and we manage to grow several despite having cedar-apple rust coming in from all sides --- a focus on types that are able to fight off that particular fungus is a big help.

But, from a management standpoint, I'd say that pears have definitely

been our easiest fruit tree, followed by apples, and then trailed

further behind by peaches. Of course, the peaches do shine in terms of producing soonest after planting, so it's all a tradeoff. But, yes, plant those pears!

The truck is still where we last left it.

Turns out our neighbor with the

tractor got a little

nervous when he saw how much mud we were dealing with and wants to wait

till it gets a little dryer.

I stressed myself out

last week by playing hooky from the garden for three days while a

writing project consumed my attention. When I came up for air, I

realized that it was time to plant twelve beds of garlic and two beds of

potato onions before the end of the week --- yikes!

Whenever I get overwhelmed by homesteading tasks, Mark reminds me that, together, he and I can do anything. Add in Kayla,

and we managed to get all of the winter alliums into the ground in

about 9 man-hours. Time to quit early and enjoy the fall weather!

I've avoided posting

anything specific about garlic here because I've pretty much said it all

before. Type "garlic" into the search box on the sidebar and

you'll learn far more than you ever wanted to know.

The only thing we're doing differently this year is to cut back to only growing Music garlic.

It seems a bit dicey to put all of our eggs in one basket, but over the

last eight years, this variety has consistently done better than all

the others, and the huge cloves make cooking a breeze. Maybe next

year we'll try a few other hardneck varieties...but maybe we'll say if

it ain't broke, don't fix it.

The old freezer

we want to use for goat feed storage accumulates water.

I think it's functioning as a

solar still when the sun hits it.

Hopefully this vent hole will

help to keep it dryer.

My second paperback has a co ver, a publication date (March 3) and a preorder page! I'm not entirely sure whether I like the image, but then, I hated The Weekend Homesteader cover...until it slowly grew on me over the years so that I now find it delightful (yellow boots and all).

And Skyhorse has done a great job producing a full-color book priced at

a steal (marked down to $11.55 at the moment), so grab one while

they're hot!

ver, a publication date (March 3) and a preorder page! I'm not entirely sure whether I like the image, but then, I hated The Weekend Homesteader cover...until it slowly grew on me over the years so that I now find it delightful (yellow boots and all).

And Skyhorse has done a great job producing a full-color book priced at

a steal (marked down to $11.55 at the moment), so grab one while

they're hot!

In other book news, the ebook version of Trailersteading

is on sale today for $1.99. I haven't uploaded the expanded and

revised version yet (still waiting on print-quality photos from a few

contributers --- you know who you are and will get email nudges next

week). But if you buy now, you'll automatically receive an updated

edition this winter when the new version is available, and will have

saved 50% off the cover price in the process. Of course, you could

also wait for the paperback, which will be coming out in fall 2016.

Thanks for putting up with a day of self-promotion. I can hardly wait to see the interior of The Naturally Bug-Free Garden,

and I suspect you'll have to bear with a glowing post about that

too. I promise that serious content will return shortly to a blog

near you.

Today I tried putting a piece

of nylon rope

where the trimmer

line usually goes.

It worked pretty good till it

got frayed, and it still kept cutting, but not as fierce.

Maybe soaking the rope in

some sort of adhesive would extend the amount of cutting each piece can

do before it needs replacing?

I love collecting weather

data --- not only is it good, geeky fun, the endeavor also helps me

decide whether the garden needs to be watered and it helps me keep track

of our specific frost-free period. Unfortunately,

weather-tracking kept falling by the wayside when the tools of the trade

turned out to be shoddy and quickly bit the dust.

A couple of years ago, I solved the temperature-tracking dilemma by going completely analog, and now I'm hoping I've found the rain gauge that will survive winter freezes.

The inner cylinder measures up to one inch of rain, then the outer

container gives you an extra ten inches of wiggle room. In the

winter, you remove the inner cylinder, bring the frozen

precipitation indoors to thaw, and then pour it into the measurer.

A couple of years ago, I solved the temperature-tracking dilemma by going completely analog, and now I'm hoping I've found the rain gauge that will survive winter freezes.

The inner cylinder measures up to one inch of rain, then the outer

container gives you an extra ten inches of wiggle room. In the

winter, you remove the inner cylinder, bring the frozen

precipitation indoors to thaw, and then pour it into the measurer.

My weather guru sent our

new rain gauge along in exchange for using our farm as a weather station

--- he's tracking the way a nearby mountain impacts microclimates in

our region. He's had to replace two rain gauges (not sure out of

how many -- quite a few) over the last seven years due to freezing, but

that's much better than my previous rate of losing a rain gauge every

year.

Now, to see if I can remember to thank him by keeping track of which days begin with fog....

The new Swisher

trimmer mower is very

easy to start.

Not so easy if you try

pulling the rope with the engagement bar pulled.

Our old mower needs the

engagement bar pulled before starting, and my robot brain took over for

the first few starts before I realized my error.

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.