archives for 08/2014

We had several commenters

ask questions about our new black soldier fly bin, so I'm going to see

if I can answer them all in one fell swoop. I understand the

interest --- we've been intrigued by black soldier flies for years. The reason we didn't experiment sooner is because we just didn't have time to reinvent the wheel and the only premade bin available when I started researching cost nearly $200. Luckily, while we were dragging our heels, the

folks over at blacksoldierflyblog.com were experimenting to create a

lower-cost version that ships to your door for a total of $76.

Their website also walks you through all of their experiments so that

you could make your own bin easily at home, but we decided to support

their ingenuity and purchase a premade bin.

If you follow our lead, I

recommend you start some food fermenting to attract black soldier flies

as soon as you place your order. It can take a few weeks for

rotten materials (with fermented grain being the blog author's

recommendation) to become ripe enough to attract the mother flies, so

you might as well start early. Since we didn't think ahead in that

way, I started some chick feed fermenting as soon as we got our bin,

but I also went hunting around the yard for black soldier fly larvae to

seed our new bug station. I quickly found a dozen relatively

mature larvae in the bedding beneath what was the duck brooder, where

spilled feed spoiled and attracted the parent flies. Other good

places to look for larvae and eggs include under the lids of trash cans

(for eggs) and in your compost bin (for larvae).

I filled the bin halfway

with partially rotted sawdust (and a bit of homemade charcoal at the

bottom) for bedding, then added a bit of the bedding material that my

found larvae were living in on top. The fermenting chick feed went

in a container on top of the bedding so the feed will stay wet, and I

also added a few vegetable scraps to start prerotting, since black

soldier fly larvae (like compost worms) need food partially broken down

before they can eat it. And then my favorite cousin-in-law also

came bearing gifts --- coffee grounds, which one of our commenters

reports makes a great food for black soldier fly larvae. Hopefully

this combination of materials will get our bin up and running in short

order. Stay tuned for many more updates in the near future.

If

any other cousins-in-law are wondering how to make it into the favorite

category, it's pretty simple. Brave our moat and come visit!

Bearing biomass, of course....

Usually when I see a blue

heron it flies away before I can get a good look.

Today we had one visiting

that seems to want to stay a while.

Here in zone 6, August is a critical time for cover crops.

Earlier in the year, I dabbled in soil improvement by planting

buckwheat (and some sunflowers) into garden gaps. But August is

the month to plant oats and oilseed radishes for long-term soil

improvement that will keep growing throughout late summer, fall, and

early winter.

Here in zone 6, August is a critical time for cover crops.

Earlier in the year, I dabbled in soil improvement by planting

buckwheat (and some sunflowers) into garden gaps. But August is

the month to plant oats and oilseed radishes for long-term soil

improvement that will keep growing throughout late summer, fall, and

early winter.

As a result, my big goal for August is to make a pass through the entire

garden, not just weeding, but also seeding oats in any beds that have

finished up their spring or summer crops and won't be needed during the

fall and winter. This job also takes those beds off my weeding

plate until spring, which is always a great feeling during the busy

summer months.

While I'm at it, I do a bit of terraforming. This corner of the front garden has been designated excess space, and I plan to turn at least one row of it into high-density apples.

However, the beds in this area were laid out when I was very new to

gardening, so the aisles are too narrow for even annual vegetable

gardening. They definitely won't provide space for our apple trees

to grow.

The solution was to turn two long rows into one, laying down cardboard

over the grassy aisle between them then shoveling the good topsoil from

one bed over to widen the second bed. Finally, I sprinkled oat

seeds on top of both the bare soil in the new aisle and the new half of

the old bed. I'm sure our young apples will enjoy the enriched

soil when they move in this coming winter or spring.

Last year at this time we

nearly had all the worm bins

full of horse manure.

We are trying to catch up to

those levels this month, but so far I've only managed to haul enough to

almost fill one bin.

"How much chicken feed will [your black soldier fly bin] produce? How many grubs are

you expecting per week? Will it be enough to be a

substantial caloric addition or is this just for a treat? Will this

replace any supplements you may currently use?"

"How much chicken feed will [your black soldier fly bin] produce? How many grubs are

you expecting per week? Will it be enough to be a

substantial caloric addition or is this just for a treat? Will this

replace any supplements you may currently use?"

This is a good question,

but the answer is a bit complicated. As a starting point, the

number of grubs you get from a unit like ours will depend on how much

food you provide and on how well colonized your unit is. Best-case

scenario is that our six-gallon unit can handle 2 pounds of food scraps

per day, which will be converted into 0.2 to 0.4 pounds of black

soldier fly larvae per day. Of course, if you don't do everything

perfectly, you'll get less.

Mass Production of Beneficial Organisms: Invertebrates and Entomopathogens

suggests that black soldier fly larvae (fresh, I think, but the table

is a bit unclear) provide 1,994 calories per kilogram. That would

mean that our daily 0.2 to 0.4 pounds of black soldier fly larvae would

provide 180 to 360 calories, equivalent to the daily energy needs of half to one chicken.

But

that doesn't mean our bin will only feed half a chicken. Protein

makes up about 35% of the calories in black soldier fly larvae, meaning

that you should consider the grubs to be more like soybeans than like

the 16%-protein feed mixtures from the store. Since soybeans often

make up about a third of the weight of store-bought

chicken feed, it's conceivable that our bin's daily output could equate

to supplemental protein for 1.5 to 3 chickens.

But

that doesn't mean our bin will only feed half a chicken. Protein

makes up about 35% of the calories in black soldier fly larvae, meaning

that you should consider the grubs to be more like soybeans than like

the 16%-protein feed mixtures from the store. Since soybeans often

make up about a third of the weight of store-bought

chicken feed, it's conceivable that our bin's daily output could equate

to supplemental protein for 1.5 to 3 chickens.

But how do you work around having this supplemental protein source on hand? You might get away with mixing one of these homemade layer feeds

and simply substituting black soldier fly larvae for soybeans (figuring

that a pound of dry roasted soybeans is equivalent to about 2.24 pounds

of fresh black soldier fly larvae). Or, on a smaller scale, you

could simply provide your chickens with all the black soldier fly larvae

you have available and then also provide an automatic feeder full of

store-bought feed and another of grain so the chickens can lower the

overall protein level of their diet (by eating more grain) as they see

fit.

No matter how you figure

it, having a high-protein, animal-based feed available for chickens

should cut feed costs and improve the birds' health, along with boosting

the nutritional density of the eggs and meat the chickens

provide. The real question will be --- is the positive impact

greater than if we simply fed our food scraps to the chickens (as we

currently do) instead of to the black soldier fly larvae?

Why did we choose this

particular Black

Soldier Fly container?

It was less than half the

price of a BioPod, which seems like a good product,

but we have a soft spot for the smaller homesteading business

operation.

Maybe someone should compare

each one side by side to see who can produce the most grubs? Of course

you would have to put the exact same food scraps in each bin.

The one thing I wished I'd done differently with our purchase of a quarter of a pastured cow was

to ask for more stew beef. I should have realized that most

Americans would vastly prefer ground meat to stew meat, so nearly all of

the tougher cuts showed up in our freezer ground. But ground meat

doesn't make a very good fit for adding protein to soup...unless you

turn it into meat balls!

You can season your meatballs any way you want, but I decided this combination of flavors worked well with our tomato-based harvest-catch-all soups. Ingredients include:

- 1 pound of ground beef (low fat content is better)

- 1 small egg (this is a great use for pullet eggs)

- 0.25 cups of parmesan

- 1 well-packed cup of fresh basil leaves

- 1 to 3 cloves of garlic (depending on your taste buds)

- salt and pepper

If you're using a food processor, just throw a chunk of parmesan, the

basil, and the garlic in and whir the ingredients around until they're

cut into tiny pieces. Otherwise, start by cutting up the basil,

mincing the garlic, and grating the parmesan. Either way, you next

add the egg (I was making a double recipe in the photo above, thus the

two pullet eggs instead of one) and the salt and pepper. Wash your

hands well, then turn the meat into the bowl with the seasonings and

work them together until they're well mixed.

Roll out the meat mixture into small balls and set them on a plate in

the fridge for half an hour for the flavors to meld. Then heat a

little bit of oil in a skillet over medium high heat and place the

meatballs in the pan. Once the bottoms begin to brown, turn the

meatballs over and cook until the other side is brown as well.

(The meat in the center of the balls will still be uncooked at this

point.) Finally, make sure your pot of soup is at a gentle simmer

and plop in the meatballs to finish cooking in the soup broth, a process

that takes about ten more minutes. Cut a meatball open to make

sure the centers are brown before serving.

This recipe makes

enough meatballs to add protein and oomph to 1.5 gallons of hearty soup

if you're an average American. Before I met Mark, I probably would

have made the meatballs smaller and used this recipe for 3 gallons of

soup; and before Mark met me, he probably would have doubled this recipe

to use in 1.5 gallons of soup, so use your own judgment. No

matter which proportion you use, these meatballs will spice up your soup

and turn it into a full meal!

Anna likes to push our basket carrying capacity a little past its normal limits.

I've been surprised by

how much joy I've gotten out of flowers this year. I always put

the bare minimum amount of effort into non-edible plants, choosing the

easiest annuals and perennials that survive lots of neglect.

Zinnias, sunflowers, touch-me-nots, and scarlet runner beans seem worth

replanting using my lazy methods, and echinacea and bee balm have

already survived years of neglect.

From the perspective of

the local wildlife, sunflowers are probably the top choice among my

for-show flowers --- I definitely see more bugs there than on my other

"useless" plants. I've been enjoying the hummingbird who claimed

our patch of scarlet runner beans, though --- she drops by multiple

times a day and has been busy chasing off the competition.

Part of the reason I've

gotten so much bang for my buck from flowers this year is that I started

a patch in front of the trailer where we can see the flowers from the

couch and from the outdoor table. So I'm dumping weeds along

another section of the front porch this summer to give a little

fertility to soil that will become flowers next year. No, flowers

aren't worth wasting cardboard on, but this lazy kill mulch will do its

job pretty well anyway.

I'm curious to hear from

other similarly lazy flower gardeners. Which species make the cut

among your low-work annuals and perennials?

The driveway was dry enough

today to drive in a truckload of straw.

How many bales can you fit

into a Chevy S-10 truck?

We got 10 bales today for

57.50.

We really depend on our pulsating sprinklers to turn dirty creek water into a well-hydrated garden. So when one starts acting up, we rush to fix it.

We really depend on our pulsating sprinklers to turn dirty creek water into a well-hydrated garden. So when one starts acting up, we rush to fix it.

The easiest problems are when the sprinklers clog (often from algae growing in the hoses), but this issue has been much less frequent since Mark removed the filters.

More often (now that the sprinklers are aging), we have to deal with

sprinklers that get stuck. Water keeps flowing out, but the

pulsating action isn't enough to push the sprinkler head around in its

little circle. Sometimes, greasing the sprinkler helps, but this week, two rounds of grease failed to have any impact on the sprinkler shown above.

As

I growled and moaned at my sick sprinkler, I realized that if I placed

my thumb where the moving piece at the back of the sprinkler hits the

solid piece, the sprinkler would run normally. Perhaps the

sprinkler had just come slightly out of true (or had worn down the metal

that the moving piece is supposed to hit on)? Twisting a piece of

wire around that stationary piece to emulate where my thumb had been

sitting was enough to get the sprinkler running normally again. My

pride at doing Mark-style troubleshooting knew no bounds!

As

I growled and moaned at my sick sprinkler, I realized that if I placed

my thumb where the moving piece at the back of the sprinkler hits the

solid piece, the sprinkler would run normally. Perhaps the

sprinkler had just come slightly out of true (or had worn down the metal

that the moving piece is supposed to hit on)? Twisting a piece of

wire around that stationary piece to emulate where my thumb had been

sitting was enough to get the sprinkler running normally again. My

pride at doing Mark-style troubleshooting knew no bounds!

Of course, the wire isn't

a long-term fix, since the action of the sprinkler tends to bend it out

of true. We can upgrade to a heavier piece of wire, but perhaps

those of you familiar with this type of sprinkler can tell me what's

really wrong based on the description above. Is there something I

can adjust to bring back our sprinkler's charmed youth?

We decided to get rid of this

old Statesman tiller we never use anymore.

Why did we stop using it?

Because the soil in a no-till

garden looks, feels, and

smells a whole lot better.

Berries are much simpler

than tree fruit. At least in our climate, the former are less

prone to bug and disease problems, and many berry bushes start fruiting

when they're a year or less old. But berries do have two major

problems --- picking time and bird predation. People are always asking me how we keep birds out of our berries, and the truth is that we'd never had much of a problem...until this year.

This spring, the blue

jays were so bad amid our strawberries that I'll admit I shot at them to

get the family to move out of the yard. It's illegal to kill a

blue jay without a permit from the game warden, but you can scare the

birds off with frequent shots into your strawberry patch. I was

very relieved when the jays moved on, leaving the rest of the berries

for me.

So

when our blueberries started getting eaten, I thought perhaps the

corvids were once again at fault. Nope. Mild-mannered

cardinals were responsible for pecking each ripening fruit just before

it became 100% sweet, ruining the flesh that they didn't consume.

So

when our blueberries started getting eaten, I thought perhaps the

corvids were once again at fault. Nope. Mild-mannered

cardinals were responsible for pecking each ripening fruit just before

it became 100% sweet, ruining the flesh that they didn't consume.

At this busier time of

year, Mark and I didn't have time to put much energy into the bird

problem, so we waited...and it went away. No, the cardinals didn't

stop dining, but the heavier-bearing bushes began ripening their

fruits, and there were soon so many blueberries present that the birds

couldn't really put a dent in the harvest.

My conclusion is that,

short of a voracious family like this spring's blue jays, your best bet

is simply to overplant berries so that you can share with the

birds. Yes, you can rig up some kind of bird deterrent or build a

frame to cover with netting, but isn't it easier just to double your

planting and dine with the cardinals?

We got the truck stuck in the

worst possible place yesterday.

It's bottoming out on our row

of carefully

placed cinder blocks.

Pulling it backward and

forward didn't work today.

Arghhh!

One of our readers asked what we do with excess summer squash. We definitely have a lot of it, since I succession plant to beat the bugs and thus put in far more squash plants than we really need. We've tried drying

or freezing the excess, but neither option seemed very palatable when

we broke back into our winter stores. So, currently, I just pull

out old vines once the new ones start producing and eat what we want in

the interim.

Even

using that method, there are still lots of big squash that get away

from us. So when I remove vines, I select half a dozen of the

darkest-orange squash from various plants to sit on the porch for a

month and then be broken open to provide next year's seeds. After that, the rest of the squash go to the chickens.

Even

using that method, there are still lots of big squash that get away

from us. So when I remove vines, I select half a dozen of the

darkest-orange squash from various plants to sit on the porch for a

month and then be broken open to provide next year's seeds. After that, the rest of the squash go to the chickens.

If you watch your flock, you'll discover that they're not so interested in cucurbit flesh (although they will

eat it if they haven't had many other vegetables lately). What

the birds really want, instead, is the fresh seeds. Unfortunately,

big squash like the ones I earmark for chickens have skins too tough

for the birds to peck through, but that's easily fixed by whacking away

at the squash with a shovel until each fruit has popped open to expose

the more nutritionally-dense morsels inside. This same method is

pretty effective at moving overripe cucumbers back into the food chain

too.

Each

chicken will only consume the seeds from maybe half or one large squash

per day, but I'm hoping my wheelbarrowful will get eaten before the

fruits entirely rot away. I came back a couple of hours after

dumping the squash in the chicken pasture and saw several fruits

hollowed out, but also lots Yellow Soldier Flies (Ptecticus trivittatus) circling over the

squash, some mating and presumably laying their eggs in the squash

flesh. Does anyone know if Yellow Soldier Flies can be raised in the same bins as Black Soldier Flies?

Each

chicken will only consume the seeds from maybe half or one large squash

per day, but I'm hoping my wheelbarrowful will get eaten before the

fruits entirely rot away. I came back a couple of hours after

dumping the squash in the chicken pasture and saw several fruits

hollowed out, but also lots Yellow Soldier Flies (Ptecticus trivittatus) circling over the

squash, some mating and presumably laying their eggs in the squash

flesh. Does anyone know if Yellow Soldier Flies can be raised in the same bins as Black Soldier Flies?

Side note about soldier

flies aside, what should you do with your squash if you don't have

chickens? Today is Sneak Some Zucchini onto Your Neighbor's Porch

Night --- go celebrate!

We appreciated everyone's educated feedback about our natural-gas-to-propane stove-conversion project.

It turns out the stove's previous owner wasn't as well informed.

Using the manual, we flipped

the pressure regulator from natural gas to propane. But when we

removed the orifices, we discovered that the burners had already been

converted over. ("L" on the orifice refers to LP, commonly known

as propane.)

Perhaps the improper conversion is why the stove was being sold cheap?

Although I probably would

have gone with the wait-and-see approach, Mark opted to spend an extra

$20 on some black-soldier-fly eggs to get our bin

off to a faster start. This was probably a good idea since summer

is already waning and we'd like to get some data on the composting

experiment before winter.

Meanwhile, an expert over at Bugguide.net provided some information on the yellow soldier flies that I posted about yesterday.

Fly expert Martin Hauser noted: " While [the black soldier fly] eats

literally everything (it is used in organic waste

disposal), [the yellow soldier fly] develops also in my compost pile,

but they clearly

prefer rotten fruit." It sounds like if we had enough excess

squash and other semi-sweet morsels, we could expand our bin's capacity

with this second species too. In fact, I wouldn't be surprised if

yellow soldier flies end up laying eggs in many black-soldier-fly bins

undetected.

Meanwhile, an expert over at Bugguide.net provided some information on the yellow soldier flies that I posted about yesterday.

Fly expert Martin Hauser noted: " While [the black soldier fly] eats

literally everything (it is used in organic waste

disposal), [the yellow soldier fly] develops also in my compost pile,

but they clearly

prefer rotten fruit." It sounds like if we had enough excess

squash and other semi-sweet morsels, we could expand our bin's capacity

with this second species too. In fact, I wouldn't be surprised if

yellow soldier flies end up laying eggs in many black-soldier-fly bins

undetected.

In a perfect world our chickens would get most of the sunflower seeds we grow, but the local bird population usually takes a major chunk before the seeds get a chance to finish drying.

Mom brought me this

140-year-old book yesterday, and I've been pondering it ever

since. Books like this always feel like an opportunity, but I

generally end up asking myself, "An opportunity for what?"

The

illustrations are beautiful...but the text is really only interesting

to folks who are intrigued by both nature and history and thus don't

mind mentally translating captions like "hive bee" into "honey

bee." There is a print-on-demand version of the title available on

Amazon already, but the book's lack of ranking within the store means

it's probably never been purchased.

The

illustrations are beautiful...but the text is really only interesting

to folks who are intrigued by both nature and history and thus don't

mind mentally translating captions like "hive bee" into "honey

bee." There is a print-on-demand version of the title available on

Amazon already, but the book's lack of ranking within the store means

it's probably never been purchased.

My mind wanders through

various scenarios for bringing the heart of this book back into the

public eye. I could hire someone to scan every image and simply

write a quick summary of the nest to go with each picture. Or I

could think outside the box and turn it into a children's story since

the author's theme (animal nests) is very age-appropriate.

I've gone through similar

mental perambulations over more homesteading-related titles, and always

ended up veering away because I have a hard time figuring out which

books are really in the public domain and up for grabs. Robert Plamondon

does an excellent job bringing old farm-related titles back into print,

so perhaps I should leave the job to him. But it's hard to turn

down opportunities when they stare me in the face so prettily....

Ideas?

The 28

inch flashing material is keeping the coop dry.

One of the rolls is

discolored a bit, but it seems to be fine.

I'm guessing it's some kind

of coating material that was different when we got the second roll.

A couple of weeks ago, I opted to super (rather than nadir) our larger warre hive.

If you're interested, you'll want to follow that link for more on the

pros and cons, but since I wrote my original post, I've realized there's

one more major disadvantage to the action. Supering the hive

makes it impossible to guess what's going on inside using a simple

photograph up through the screened bottom rather than using an invasive

search through the boxes.

In contrast, I nadired the smaller hive

three weeks ago, which has allowed me to keep a close eye on the bees'

progress. The sourwood started petering out soon thereafter and

the "yellow flowers" (as my beekeeping mentor refers to wingstem,

woodland sunflowers, goldenrod, etc.) have only barely started up.

So I wasn't surprised to see that that daughter colony has just now

begun to build the first piece of new comb in its third box.

With 20/20 hindsight, I'm

now figuring that the smarter tack when choosing to super a warre hive

is to add two boxes at the same time, figuring any empty space can be

deleted when I delve back into the hive to collect honey. And I

think there's a good chance we will

be harvesting honey from our mother hive this year since sources on the

internet suggest that two warre-hive boxes (one of honey and one of

brood) are sufficient to keep a colony going through the winter months

unless you live in the far north. We currently have at least three

full boxes on that hive, with the super being the wild card that could

bring us up to four.

Since I don't want to repeat last year's disaster of removing brood when I thought I was removing honey,

I'll be waiting until mid to late September to steal the sweet

stores. At that point, the queen should have moved down lower into

the hive and left the honey unaldulterated in the top box or two,

making robbing relatively painless.

It's been a long wait to

get significant honey from our warre hives, and I can see how that could

turn many apiarists off the method. On the other hand, either the

hive or the chemical-free bees

we put into them have resulted in at least one colony that seems able

to survive without chemical intervention. Here's hoping the

daughter hive will be just as vigorous, surviving the winter and perhaps

giving us a honey harvest in 2015.

Our ATV developed a fuel leak

recently.

A visual inspection revealed

what looked like a spot where it was dripping and clearing away mud,

and above that was a hose clamp that needed tightening.

The plan is to add a small

amount of fuel with newspaper spread out underneath to see if the leak

is fixed.

It's ragweed week around here. Even though Mark went through a couple of months ago and tried to rip up all of the small ragweed

within our core homestead, some plants slipped through his net.

Now that the massive plants are getting ready to bloom, it's time to go

through with the loppers and cut each one down so we don't have

thousands of new plants next year. The "chore" becomes much more

fun when I realize I can easily load all that awesome biomass into the

green wagon and use it to top off a kill mulch for next year's high-density apples.

Meanwhile, out in the

starplate pastures, I'm leaving the ragweed alone. I figure that

anything willing to grow in that poor soil will only add much-needed

organic matter to the ground, and if the ragweed plants spread their

seeds widely, we can just mow down the offspring when it's time to turn

the area back into pasture. In the interim, ragweed acts as a very

good deer-monitoring tool since the plants are very tasty to ungulates

at three to five feet tall. Weeds like the one shown above are a

sign that the deer are busy munching in that pasture --- yet another

reason not to plant apple trees there until our fencing is 100%

complete.

Fogged up safety glasses have

always been a problem for me on humid days.

Some days I need to stop weed

eating every 10 minutes to clear the fog.

Today I tried something

called Clarity

Defog it wipes. Wipe

the inside of your glasses and say goodbye to fogged up lenses. Not

sure how long it will last. I put my used wipe in an airtight container

after I opened the sealed foil.

Bouts of cool, rainy

weather prompt our asparagus to send up new spears, even if it is August

instead of April. In the past, I've left these late-summer

asparagus spears alone, but this week I started wondering how much

energy late spears will really sock away for spring. Our asparagus

patches are already covered with forests of fronds, and there are only

two months of growing time left before frost (with the days getting

shorter and cooler  all the time). So I opted to pick a handful of August spears to tempt our jaded summer palate.

all the time). So I opted to pick a handful of August spears to tempt our jaded summer palate.

If you really want a

late-summer harvest of asparagus, the official method is to plant two

beds --- one for spring and one for fall. In the fall bed, you

don't harvest any spears when they first come up, letting the plant put

all of its energy into frond production. Then, in July or August,

you lop down all the tops and enjoy the new spears that come up in their

place.

We have so many

vegetables to choose from at this time of year that it doesn't seem

worth setting aside asparagus beds just for a fall harvest. But a

stolen spear here or there never hurt anyone....

We're trying reader Faith T's comment on using a

shopping bag to block birds.

I cut some holes at the

bottom which might help to prevent molding.

Doing it side by side with an

unprotected flower should be a fair test.

About a week after applying humanure

around the base of our kiwi plants, I figured out a minor flaw --- the

compost is chock full of tomato seeds. When I cook tomatoes into

soups and sauces, I leave the skins and seeds in, and apparently the

human digestive tract doesn't bother the seeds at all. Since

tomatoes are a large proportion of our winter diet, the result is a

forest of seedlings everywhere I laid down humanure in the garden.

I'll let all of the

tomato seeds sprout, then if they seem to be growing too fast, I'll let

Mark whack them down with the weedeater. In future, it might be

smart to apply humanure just a few weeks before the first frost --- long

enough to get the seeds to sprout before winter naturally kills them

off.

Cut the tops and bottoms off.

Sort according to size.

Save the big ones to plant

again.

Yes...we used the stalks as

an addition to the ragweed

mulch.

The last time I thought we had a copperhead in the yard,

it turned out to be a water snake. And this time, once again, I'm

ashamed to say I stole half an hour of Mark's morning and tied up our

free-range dog for what I was positive was a copperhead. Only to

discover, upon closer  examination of the photos, that our reptile turns out to be...a water snake.

examination of the photos, that our reptile turns out to be...a water snake.

The snake in question was

hiding under some cardboard that I'd used to mulch between our

blueberry bushes. I ran out of tree leaves this spring and opted

to just weigh the cardboard down with branches, which did a pretty good

job keeping weeds down to a dull roar, but which seems to have mimicked a

snake's preferred napping spot --- a cavity under a rock. In

hopes of growing some of my own mulch, I was out in the morning cool

Thursday moving cardboard closer around the bases of the blueberries and

sprinkling oat seeds in between, and I nearly patted this guy on the back before I knew he was present.

Luckily for me, snakes

are slow in cool weather, and this snake was the least aggressive water

snake I've ever met. Despite quite a bit of wiggling the hoe

around, trying to get the snake to slither into a bucket for relocation,

the snake only (finally) tried to strike when Mark took over the tool

and got more aggressive at the snake-capturing campaign. In the

end, our visitor slithered away into the weeds and disappeared from view

without seriously trying to bite anyone.

In retrospect, I'm not

sure there's really much point in trying to capture and move a snake,

even if it really is poisonous. As Mark pointed out, we could have

half a dozen around the yard without knowing it due to how skittish

most snakes seem to be. I just need to remember the basic farm

rule --- when lifting something like that piece of cardboard, always

lift away from you rather than toward you and assume there's a poisonous

snake underneath. (But do check the snake book one last time

before calling in reinforcements since 67% of our copperhead sightings

seem to turn into water snakes in the light of day....)

This Clymer ATV repair manual is a little expensive at just

over 30 dollars but pays for itself when it guides you to fixing a

problem.

Almost 500 pages of

impressive technical details seems to cover just about any problem that

might happen, along with a comprehensive troubleshooting section that

can often save huge amounts of time.

It's already helped me twice

by pointing out a

quirk in the way oil is added to a Polaris 700 ATV. The other way was recently when

I used the fuel system diagram to track

down a leak.

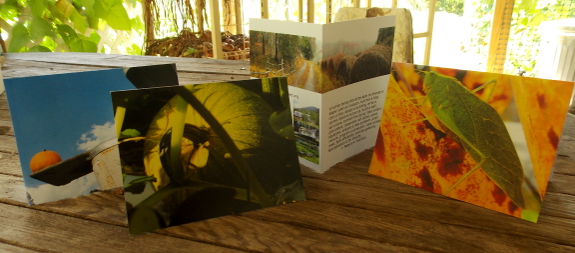

Years ago, I made

notecards out of my watercolor paintings, and I've been using those

cards for letter-writing ever since. But the inevitable finally

happened --- I ran out! Rather than buying someone else's

notecards to fill in the gap, I figured, why not make up some Walden

Effect cards to spread the word instead?

I

chose four fun images for fall, then printed 65 of each, enough for me

and my mom to use, with some to give away and sell. If the

response is good, I'll even choose another round of homesteading images

in a few months and do a winter series to match these fall images, but I

won't be reprinting the fall set, so act now if you'd like a copy!

I

chose four fun images for fall, then printed 65 of each, enough for me

and my mom to use, with some to give away and sell. If the

response is good, I'll even choose another round of homesteading images

in a few months and do a winter series to match these fall images, but I

won't be reprinting the fall set, so act now if you'd like a copy!

If you want some pumpkins

and simplicity quotes to brighten your day, you can buy sets of four or

sixteen notecards (which come with envelopes and shipping included,

even numbers of each design), or you can enter the giveaway at the

bottom of this post to win free packages of four cards. (As a side note, if you live outside the U.S., you can

enter the giveaway, but will need to email me if you'd like to buy

notecards. I haven't figured out what international shipping costs

would be yet, but I don't think they'll be too much.)

16 notecards --- $18

We'll be giving away sets

of four notecards to three different winners next week, and if we get

more than 100 entries, we'll add another winner for every 50

entries. So tell your friends and use the widget below to enter!

How can you tell which cat is

the Alpha cat in a group?

In our group Huckleberry only

sits on the prime roosting

spot when Strider is off

somewhere doing his normal activities. If Strider comes back and it's

occupied he just takes it without even a dirty look from Huckleberry.

Back

in 2003 when my previous watch died, I decided I wanted a watch that would

really go the distance. With my usual supreme unconcern for

aesthetics, I chose the huge specimen shown on the right above, and that watch has

served me very well. Between waterproofness, shock resistance,

solar battery charging, and automatically setting the time every night

using something I can't recall (radio waves from Texas?), I haven't had

to deal with watch issues in over a decade.

But all good things must

come to an end. The battery inside my beauty finally stopped

accepting a charge a few months ago, and I decided to buy a new watch rather than a new

battery. Over the last decade, due to Mark's hard work to smooth down

the edges of my type-A personality, I've stopped wearing a watch every

day and instead simply use my time piece to check the hour if I wake up

at night, to jerk me out of sleep once or twice a year when I can't wake

at my normal pace, and to monitor how long we've been rubbing rocks

when counting stream macroinvertebrates. I do

like the solar feature of my old watch since longevity is always a

boon, but since I rarely take watches out in the field now, I'm willing

to bypass the extreme waterproofing and shock resistance. I'm even

willing to set my watch twice a year to take care of daylight savings

time the hard way.

Despite that willingness

to downgrade, I put off buying a replacement watch for months. I

remember my old watch was pretty pricey (although I don't recall the

exact figure), and I wasn't sure I was willing to spend so much

again. But apparently solar technology has come down considerably

in the last decade. A simple solar watch now costs under $10 even after you factor in shipping!

At that price, and with such good reviews, Mark said he wanted one

too. Here's hoping my second solar watch will last another 11

years, not just the 6 years promised by the manufacturer.

Anna has been researching

battery powered chainsaws and somehow arranged for the nice people at Oregon tools to send us a

complimentary review chainsaw to drive around the block a few times.

The first test will have to

wait till the massive 40 volt battery charges up.

Stay tuned to see how long

the battery lasts and what kinds of firewood it can handle.

I knew when we bought our quarter of a cow

that we might run out of freezer space as a result, and the inevitable

has finally happened. Pastured beef, homegrown chicken, some

strawberry jam and leather, plus 22 gallons of various vegetables

equates to a freezer nearly full to the brim. What's next?

If it were September

instead of August, I'd say, "Time to rest on my laurels and prepare for

winter!" But the garden is still overflowing, and we should have

at least a bushel apiece left of beans, corn, and tomatoes coming in

over the next few weeks. In a pinch, I can give some away, but we

always wish we had more summer bounty come spring, so I'd prefer to

preserve at least a few more gallons of warm-weather food.

The obvious solutions to

round out our preservation campaign are canning and drying. If I

limit myself to plain tomatoes, canning is easiest since I can use the

hot-water-bath method, but I'm tempted to brush off the pressure canner

we bought years ago as a backup to the freezer and try my hand at

canning soup. Alternatively, I could dry tomatoes,

which is a bit more nitpicky but is cooler since the heat source is

outside rather than right in our living area. And, if I were

brave, maybe I'd even try my hand at drying corn and beans?

What do you do when you run out of room in the freezer and still have food in the garden? (Don't say "Buy a pig!")

The bottom of our chicken

tractor nest box collapsed this weekend.

After fixing it this morning

I made a holder for a 2 gallon chicken bucket waterer.

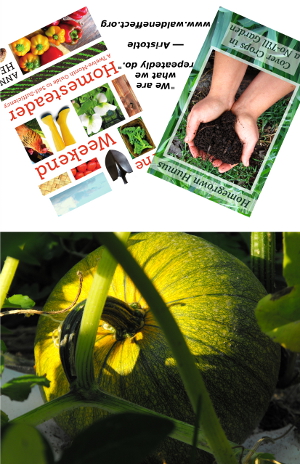

Even though I'm quite happy with my current cover-crop campaign (explained in depth in Homegrown Humus), there are some gaps I want to fill in both the book and in my own protocols. Time for an experiment!

Part of this year's cover-crop experiment is going to take place off-farm. As with any gardening book, Homegrown Humus

is largely based on my own experiences, which means that people who

live far away may have slightly different results. So I tracked

down ten readers scattered across the U.S. who were willing to accept

free packs of cover-crop seeds in exchange for putting my experiments at

work in their own gardens. Seed packages went in the mail last

week for folks living in zone 5 and colder, while everyone else's seeds

will be mailed out tomorrow. I'm really looking forward to

learning how buckwheat and sunflowers do during "cold" months in the

Deep South and how oats, oilseed radishes, and fava beans fare all over.

"Fava beans?" you may be

saying. "You haven't mentioned that cover crop before." Very

astute of you! In fact, fava beans are the other part of this

year's cover-crop experiment --- trying out a new species for our farm.

I've read a lot about fava-bean cover crops on permaculture blogs, but

the legume seems to be hardy primarily in zones 7 and warmer.

Since we live in zone 6 (and sometimes have nearly zone-5 winters due to

our north-facing hillside), I figured fava beans were out of our

league. But why not push the envelope?

To that end, I soaked Windsor fava bean seeds for speedy germination,

then planted 0.625 pounds in several different locations around the

farm. Soon I'll know if fava beans are worth the high seed price

($12.75 per pound once you factor in shipping), whether they can handle

clayey soil, whether they will survive in waterlogged ground, and

whether they do well when mixed with oats and oilseed radishes.

Stay tuned for updates!

Do

you want to be part of future experiments? I usually post this

type of opportunity to our facebook page, but even if you're already a

fan, facebook might not be showing you our updates. Be sure to

click the like button at the bottom of our posts when you notice them if

you want to be sure to see them on your news feed in the future!

We tried out the new Oregon battery powered chainsaw today.

I was very impressed with the

power. We cut down a medium sized walnut tree with no problem. We also

cut up some small pieces for an upcoming Rocket Stove experiment

It's nice to not need ear protection.

When Mark's gas-powered

chainsaw

died after only a couple of years of use, I decided to see if there were

any battery-powered chainsaws out there. It turns out that quite a

few battery-powered

saws are starting to look like possibilities for homesteaders who just

need to cut enough firewood to get them through the winter. Is a

battery-powered chainsaw a good option for us (and for homesteaders like

us?).

While attempting to

answer that question, I came across many pros and cons for

battery-powered versus gas chainsaws. The major disadvantage of

battery-powered chainsaws is that they're not quite up to handling the

same extreme cutting conditions that gas-powered saws are. Most

reviews of even the best battery-powered chainsaws suggest that cutting

trees more than 9 to 12 inches in diameter (depending on the hardness of

the wood) might stress your saw, and you'll need to be pretty careful

with maintaining chain sharpness to get even that level of

cutting. Similarly, you can't cut all day with a battery-powered

saw since the battery usually gives out after an hour or two, and, in

the long run, replacement batteries usually cost over a hundred bucks

once the cell stops accepting a charge. (Of course, Da Pimp might extend that battery life considerably.)

On the other hand,

battery-powered saws have a major appeal for folks like us who wouldn't

usually be cutting for more than a couple of hours at a time

anyway. There's the quietness factor --- not only are

battery-powered saws silent when not cutting, they're much quieter than a

gas-powered chainsaw even when zipping through wood. We'd never

have to fight those ornery pull starters (that always seem to get harder

and harder to pull as a gas-powered saw ages), and maintenance in

general is likely to be much simpler with a battery model.

Homesteaders who go for months without cutting won't need to be as

worried about their saws if they opt for battery-powered versions since

there's no fuel to go bad, and battery-powered saws probably cause less

overall pollution than a typical two-stroke gas saw. Finally, a

battery saw definitely feels safer since the motor isn't running at all

as you move between areas to cut.

Is the pleasantness factor worth the lack of power? We received a review saw from Oregon to see if we can answer that question. Stay tuned for a bunch of posts from Mark as he experiments with our trial saw,

and for a later post from me explaining how we narrowed down the

battery-powered chainsaw choices out there. In a few weeks, I hope

that we'll be able to tell you whether or not a battery-powered

chainsaw is worth the expense for homesteaders.

An old hand cranked Chinese

military generator found its way back to us recently. (More on those

details tomorrow.)

It was designed to power Army

radios in the field. Cutting the 4 pin cable reveals black, red, and

white wires. The red and white wires equal 30 regulated volts at 1 amp

and the red and black outputs 25 regulated volts at 2 amps.

I'm surprised at how

little effort it takes to create 12 to 15 volts. The first experiment I

want to do is hook up an additional voltage

regulator/charge controller

to try charging a golf cart battery.

It turns out that a

like-minded neighbor was living a mere half mile down the road from us

all this time, and we only learned the extent of our similarities when

she got ready to move away. For health reasons, our neighbor is

having to return to her home state, and she decided that much of her

homesteading gear wasn't worth shipping south. Did we want a rocket stove, hand-cranked generator, solar oven (with one broken pane), and much more? Definitely!

I'm most excited about

experimenting with the rocket stove and the solar oven, while the

Chinese military-issue generator from 1972 tops Mark's list.

However, what I actually

used first was an item I thought wouldn't be much use to us here.

A simple wooden rack of drying trays makes sense if you live in a

climate where the humidity doesn't often hover around 80%, but if we

tried to dry food in such a device without building a solar dehydrator around it, we'd just grow mold.

Still, when I realized

I'd picked too much basil for my current batch of pesto, I thought ---

maybe the simple drying setup would work for herbs? I filled the

four trays with basil, oregano, chives, and Egyptian onions and will

report back in a few weeks once I discover which, if any, dry quickly

enough to maintain their flavor in our wet climate.

A huge thank you to our soon-to-be-ex neighbor for sharing the bounty with us!

Our good spatula broke in

two. I tried gluing it once, but it didn't hold for long.

It works okay like this...but

we lost a pastured beef meatball last week due to it separating.

Today I got lucky with

drilling a hole through both the plastic and metal and securing it with

some found hardware. With any luck this will put an end to any future

meatball casualties.

Nuts are notorious for

taking a long time to bear. For most species, you probably

shouldn't expect a harvest for at least a decade, and during that time

nut trees may spread to cover an area fifty feet in diameter. So

it's no surprise that many homesteaders instead turn to the bush growth

habit and relatively fast bearing nature of the hazel.

Of course, "relatively fast" isn't exactly speedy. Almost five years after planting, our unnamed hybrid hazel variety from the Arbor Day Foundation is finally starting to take off, and I was excited to see both male and female flowers on the bush this spring. I'd thought the latter dropped off, but

closer inspection this week turned up a few developing fruits nearly

hidden amid the foliage. Since only one of the three bushes I

originally planted survived, this bush is either self-pollinated or

(more likely) the wild hazels about a hundred feet away in the woods

provided enough pollen for everybody. No matter who the nuts'

daddy is, I'm excited to think that we'll get to taste our first

homegrown hazels this year after all!

Despite our bush's slow

initial growth, it has proven itself able to handle waterlogged soil, as

is evidenced by the "pond" in the photo above, which is actually a pit I dug to gauge groundwater levels and to elevate the surrounding soil.

Unfortunately, the two named varieties I planted in the starplate

pasture this spring have been less resilient in the face of heavy deer

pressure. Only one of the two bushes has survived and I recently

decided that the hazel would probably do better if transplanted into the

safety of our core homestead close to its cousin. In fact, I

might even dig the little survivor up now rather than waiting for the

usual transplanting season (after the leaves fall) since I'm not sure

how much plant will be left after a few more months of deer grazing.

Rambling aside, the purpose of this post is really to tell my father to go check on his hazel bush. Yes, you think

it's never born fruit, but I had to look really, really close to see

the developing nuts on my bush, so yours might have them as well.

Or you can wait a few more weeks until the husks turn brown and look

less like leaves, at which point I suspect the nuts will be more

evident.

Anna:

Brandy is the

original source of my kefir grains, and she's been experimenting with

wild fermentation for much longer than I have. So I was thrilled

when she offered to share a bit about her experiences...along with a

free starter culture for one lucky winner. Scroll to the bottom of

this post to enter the giveaway, but be sure to read Brandy's tips too. (And don't forget that you've still got a few hours left to enter our notecard giveaway!)

Brandy:

It's been more than five years since

my kefir grains arrived in the mail, packed in a small zippered bag

and looking all squished. I don't think I knew what was ahead then,

that it would be the one thing I'd keep up with through good times

and bad, through morning sickness and two new babies. My kefir

grains have traveled, too. After sharing them with dear local

friends, they've been packed up and shipped all over the country.

I'm still just as excited about kefir as I was when they arrived, so

I thought I'd compile some of my thoughts and favorite recipes.

It's been more than five years since

my kefir grains arrived in the mail, packed in a small zippered bag

and looking all squished. I don't think I knew what was ahead then,

that it would be the one thing I'd keep up with through good times

and bad, through morning sickness and two new babies. My kefir

grains have traveled, too. After sharing them with dear local

friends, they've been packed up and shipped all over the country.

I'm still just as excited about kefir as I was when they arrived, so

I thought I'd compile some of my thoughts and favorite recipes.

I got the grains on a whim, thinking

it would be fun to try them out. I'd had some serious antibiotics a

few months before and I was not feeling all that great. I started by

making berry and peach smoothies and putting the kefir into biscuits.

I'm still doing that, and more. I haven't bought buttermilk in

years and I don't really buy much yogurt since Anna enlightened me on

the

differences. My stomach feels so much stronger, too.

I got the grains on a whim, thinking

it would be fun to try them out. I'd had some serious antibiotics a

few months before and I was not feeling all that great. I started by

making berry and peach smoothies and putting the kefir into biscuits.

I'm still doing that, and more. I haven't bought buttermilk in

years and I don't really buy much yogurt since Anna enlightened me on

the

differences. My stomach feels so much stronger, too.

Kefir makes a wonderful substitute

for buttermilk, even for those who enjoy buttermilk plain, and adds a

lovely leavening kick to quick breads. We put it in waffles,

pancakes, biscuits, smoothies, cobblers, coffee cakes, anywhere that

buttermilk would normally go. I've even used kefir cottage cheese in

place of ricotta in lasagna! My mother, who is gluten-free, enjoys

kefir as a way to add a yeasty taste to wheat-free baked goods. All

this is making me hungry, let's get to some recipes!

Fluffy

Kefir Biscuits

Kefir

Cottage Cheese

Vanilla

Kefir Ice Cream

Kefir

Cream Cheese

Long-Fermented

Sourdough Biscuits

My

simple kefir tutorial

Anna:

If those recipes sound good, you can get started on kefir in your own kitchen. Enter the giveaway using the widget below for a chance to win a starter culture, or buy your own for just $10 (plus $5 shipping) in Brandy's etsy store. Enjoy!

It's tough to make a chicken tractor light enough to pull and still strong enough to keep out predators.

The photo above shows how Kayla used movable screens to keep a hawk

from reaching through the mesh into her chicken tractor.

We recommend not trying to beef up your tractor to keep out raccoons. Instead, keep your chicken tractor very close to home (and get a good dog, if possible) to scare any potential predators away.

With raccoons, it's also handy

to make sure your birds eat any kitchen scraps very quickly. We

learned the hard way that raccoons will come for scraps and stay to eat

your chickens. Better a flock that only eats store-bought feed and

grass than birds with a more diverse diet who end up in a raccoon's

belly.

"You know, my parents' house used to be a trailer," Kayla mentioned after I posted about looking for a few more trailersteaders to profile in the upcoming print edition of Trailersteading.

It turns out that her family home is an elegant example of turning a

mobile home into a beautiful and functional living space...but you'll

have to wait to read about that in the book.

"You know, my parents' house used to be a trailer," Kayla mentioned after I posted about looking for a few more trailersteaders to profile in the upcoming print edition of Trailersteading.

It turns out that her family home is an elegant example of turning a

mobile home into a beautiful and functional living space...but you'll

have to wait to read about that in the book.

Still, I can't resist

sharing some highlights from my tour. From a purely aesthetic

standpoint, I was taken by the canned goods that Kayla and her mother

have stocked away in their pantry (including lots of pickles from our

cucurbit overflow). And aren't ripening tomatoes always beautiful?

More functionally, some

of you might want to follow the family's lead and turn a yard-sale bed

into a beautiful bench like the one shown above. Just use the

headboard for the back and cut the footboard in two to create the

sides. Kayla's mom decided to make her own bench after seeing a

similar one selling for $150; in contrast, her version cost only about

$10 to produce.

On a similarly crafty note, I was so taken by the harmonious sound of Kayla's silverware wind chimes that I traded a chicken waterer

for a set to take home. When I first saw photos of these wind

chimes, I expected them to be a bit tinny like the cheap chimes you can

get from big box stores, but I was very wrong! Want a set of your

own? Kayla has four more already made and up for sale in her Etsy store.

Thanks so much for letting me invade your home and take photos, Kayla and Alice!

I've looked at a lot of

chicken cam set ups over the years and have not been impressed with any

until I found Terry Golson's HenCam.com.

What's it take to keep 4 live streaming cameras going in a barnyard

environment? Terry's

husband does an excellent job explaining the not so easy IT details

that make such a project possible.

They've also got goats to

keep their flock of over a dozen chickens entertained.

I'm intrigued by the potential of the scarlet runner beans I'm growing for the first time this year. I planted them for quick shade along the south face of the trailer

while the perennial vines get established, but I was soon taken by the

way the orange-red flowers attract hummingbirds (plus bumblebees,

butterflies, and other insects). And now I'm wondering whether

biomass production might not really be scarlet runner beans' primary

selling point.

"Those

plants are like annual kudzu!" I told Mark at lunch yesterday, and he

asked me why I was being so mean to the beans. But, the truth is, I

was paying them a compliment. If the species wasn't the scourge

of the South, kudzu would have a lot going for it from a permaculture

perspective due to its ability to fix nitrogen, to thrive in poor soil,

and to grow extremely quickly. Scarlet runner beans seem to share

many of the same traits, as you can see by comparing the two photos

above --- the top picture was taken this weekend while the second photo

is from only seven weeks earlier. Since scarlet runner beans are

annuals instead of perennials, they can put out this crazy amount of

weekly growth with much less risk of the beans taking over the world.

"Those

plants are like annual kudzu!" I told Mark at lunch yesterday, and he

asked me why I was being so mean to the beans. But, the truth is, I

was paying them a compliment. If the species wasn't the scourge

of the South, kudzu would have a lot going for it from a permaculture

perspective due to its ability to fix nitrogen, to thrive in poor soil,

and to grow extremely quickly. Scarlet runner beans seem to share

many of the same traits, as you can see by comparing the two photos

above --- the top picture was taken this weekend while the second photo

is from only seven weeks earlier. Since scarlet runner beans are

annuals instead of perennials, they can put out this crazy amount of

weekly growth with much less risk of the beans taking over the world.

Since our soil is getting

richer by the year, meaning we can grow more food in less space, I've

been tossing around ideas for what to do with the freed up growing

room. One big goal is to grow more of our own compost and

mulch. To that end, I'm experimenting with some plants that I

wouldn't quite call cover crops since they don't out-compete weeds, but which might mix together to make a prime compost pile.

The

photo above shows this summer's experiment of sunflowers and sorghum,

with oilseed radish planted around the roots of the left-hand bed for

weed control. Perhaps the relatively woody stems of sunflowers

will combine with the high-nitrogen vines of scarlet runner beans to

create good compost? As a lazy gardener, I'd love it if the

compost could be made in place --- just toss the plant carcasses on top

of a garden bed in the fall and let them rot into compost by spring

while shading out weeds in the process.

The

photo above shows this summer's experiment of sunflowers and sorghum,

with oilseed radish planted around the roots of the left-hand bed for

weed control. Perhaps the relatively woody stems of sunflowers

will combine with the high-nitrogen vines of scarlet runner beans to

create good compost? As a lazy gardener, I'd love it if the

compost could be made in place --- just toss the plant carcasses on top

of a garden bed in the fall and let them rot into compost by spring

while shading out weeds in the process.

It seems like I've always

got exciting cover crop experiments in the works. That's the sign

of a geeky gardener --- she's drawn to the buckwheat being grown for

soil improvement before she takes a look at your tomatoes.

We recently decided our front

porch would be a good place for a small ceiling fan.

How do you install a ceiling

fan on a slanted roof?

Level the ceiling

fan mounting kit at the opposite angle before securing it.

The bees haven't managed

to do any extra comb-building this week, as evidenced by a photo up

through the bottom of the daughter hive. Sure, there are scads of

flowers available at the moment, but bees can't fly when it's raining

every day. Luckily, both of  our colonies have socked away so much honey that they could probably coast until winter if they had to.

our colonies have socked away so much honey that they could probably coast until winter if they had to.

Honey is on my mind

because this is the time of year to start thinking about the hives'

winter survival. But survival through the cold months doesn't just

mean honey stores. Varroa mites can be a huge drain on a hive's

resources in the winter, and the populations sometimes balloon in late

summer and early fall. So I like to do a mite check

in August, another in September, and one more in October just to make

sure the colonies are on track. Our two hives passed with flying

colors during this first round --- the daughter hive dropped two mites

per day while the mother hive dropped 1.3 mites per day, far below the

worrisome threshold.

What will we do if mite levels rise over time? We already use a lot of the methods of varroa-mite treatment/prevention listed here. Last year, we tried out treating bees with powdered sugar

as well, but I don't think I'd do that again --- it could be just a

coincidence, but the hive dosed with sugar is the only one where I've

ever had a colony abscond in the fall. Instead, I might try the rhubarb trick that an old-timer recently shared with me. Better yet, here's hoping our hygenic bees will groom off so many varroa mites that I won't have to do anything at all.

Five years ago we hauled

a freezer twice this size with the golf cart.

That was during a rare dry

spell. The golf cart wouldn't have made it on a day like today and I

think we maxed out our ATV carrying capacity with this 7 cubic foot

IDYLIS.

A 10 percent discount for

veterans along with free delivery made this a sweet deal.

Our power was out for

about 21 hours Sunday afternoon through Monday morning. That

seemed like the perfect opportunity to try out the new rocket stove that our neighbor gave us!

I'd like to be able to

tell you "I only needed two sticks of wood to scramble our breakfast

eggs," but the truth is that this first iteration of rocket-stove

cookery was a learning experience. What I mostly learned is that

damp wood doesn't fly in rocket stoves --- I didn't really get the fire

blazing until I tracked down the piece of kindling in the middle of the

photo above, which had been sitting in our woodshed for a couple of

years and was bone dry. The sticks that have been drying on the

porch for a week mostly smoldered instead of burning.

Perhaps because I only

ended up using one dry piece of wood, the temperature in the skillet on

top of the rocket stove never got warmer than what equates to about

medium on our electric range. That's fine for scrambling eggs, and

would be great for things like soups, but for my next experiment I look

forward to trying out the skirt that fits around a pot to increase the

stove's efficiency by 25%. I also want to get a more solid handle

on exactly how much wood the rocket stove consumes, although I have to

say that I'm already impressed in that regard.

What was the biggest

surprise about making breakfast on the rocket stove? How much I

enjoyed the fire therapy! Usually, I get a little cranky during

power outages due to internet deprivation, but a dose of fire first

thing in the morning instead set me singing happily as I weeded the

garden. Of course, it doesn't hurt that our Cyberpower Battery Backup combined with my laptop battery means I can enjoy about an hour and a half of blogging time even while the grid is down.

In case you're curious, everything in the freezer

stayed frozen during the outage, despite highs that nearly reached

90. If the juice had stayed off for more than 24 hours, though, we

would have topped off the cold with our generator.

I installed a firewood guide

on our steel

crate garden wagon today.

The small and medium slots

will help us cut up all the fallen limbs we have.

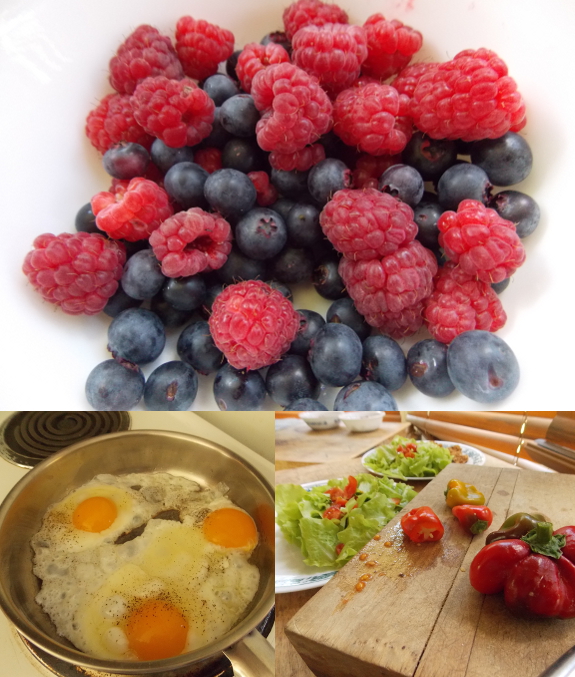

August is probably the

tastiest time of the year on our farm. This week, we've enjoyed

the first lettuce and red peppers, and the fall round of red raspberries

are starting to be nearly as copious as the blueberries we've been

enjoying for weeks. Three cups of berries per day make perfect desserts.

We're

still eating tomatoes and cucumbers and watermelons (although they're

starting to decline), and have plenty of summer squash, green beans, and

Swiss chard that will continue to go the distance. We're nearly

at the end of our spring cabbage and carrots (which currently live in

the crisper drawer of the fridge), but fall crops are all growing like

gangbusters and promise to replace the spring round soon. In fact,

I saw the first pea flower Monday!

We're

still eating tomatoes and cucumbers and watermelons (although they're

starting to decline), and have plenty of summer squash, green beans, and

Swiss chard that will continue to go the distance. We're nearly

at the end of our spring cabbage and carrots (which currently live in

the crisper drawer of the fridge), but fall crops are all growing like

gangbusters and promise to replace the spring round soon. In fact,

I saw the first pea flower Monday!

What am I watching with

an eagle eye? Our fig bushes! Last year, the first fig

ripened up at the very beginning of September, and I'm looking forward

to tasting the first few Celeste figs (along with bowlsful of Chicago

Hardy) later this year.

What are you enjoying and looking forward to seeing soon in your own garden?

Our neighbor with a tractor

has agreed to help us get the truck unstuck.

Today we just looked it over

and developed a plan.

With any luck it will

continue to dry up and make things a little easier.

This

week, the world seems to be chock full of soldier beetles.

Specifically, these goldenrod leatherwings are in a mating frenzy --- I

counted half a dozen on just a few echinacea flowers on Wednesday

afternoon.

This

week, the world seems to be chock full of soldier beetles.

Specifically, these goldenrod leatherwings are in a mating frenzy --- I

counted half a dozen on just a few echinacea flowers on Wednesday

afternoon.

With nearly 500 species

of soldier beetles in the U.S., gardeners aren't likely to learn them

all by name. But I'm pretty sure all of the soldier beetles are

either innocuous or beneficial (although some of their larvae are minor problems on fall fruits).

The beneficial species

are handy because the larvae eat slugs and snails while the adults

consume aphids. Other species (like the goldenrod leatherwing)

seem to fixate on nectar instead, but the world can't have too many

pollinators!

(Yes, this post is just an excuse to share pretty bug photos. What can I say --- they're cute!)

When is the best time to pick

mung

beans?

We pick them once a week this

time of year after they turn black.

They make yummy sprouts for

greening up tuna salad during the Winter months.

I appreciated all of the thoughtful comments on my scarlet runner bean post

last weekend! Several of you correctly pointed out that the

species is actually a perennial, although the distinction won't make

much of a difference for most of us since (like tomatoes) scarlet runner

beans are perennials that act like annuals in temperate climates.

On the other hand, that reminder did point out that not only the green

beans, shelled beans, and flowers, but also the tubers of scarlet runner

beans are edible.

However,

what I wanted to share today is a downside I just discovered of my

beautiful bean planting. Unfortunately, scarlet runner beans seem

to make awesome nurseries for Mexican bean beetles,

as you can tell from the holey leaves in the photo above (and from the

larva that was hiding in a photo in my previous post, repeated to the

left). We use the ultra-simple bean-beetle control method of

succession planting bush beans (explained in more depth in The Naturally Bug-Free Garden),

but adding scarlet runner beans to the mix means that this year's

beetle population exploded and quickly colonized my bush bean

plants. Good thing I'd already frozen several gallons of the

staple crop because the plants will probably soon bite the

dust.... I might try scarlet runner beans again, but this piece of

data suggests I should keep my for-food beans far away from my

for-beauty beans in the future.

However,

what I wanted to share today is a downside I just discovered of my

beautiful bean planting. Unfortunately, scarlet runner beans seem

to make awesome nurseries for Mexican bean beetles,

as you can tell from the holey leaves in the photo above (and from the

larva that was hiding in a photo in my previous post, repeated to the

left). We use the ultra-simple bean-beetle control method of

succession planting bush beans (explained in more depth in The Naturally Bug-Free Garden),

but adding scarlet runner beans to the mix means that this year's

beetle population exploded and quickly colonized my bush bean

plants. Good thing I'd already frozen several gallons of the

staple crop because the plants will probably soon bite the

dust.... I might try scarlet runner beans again, but this piece of

data suggests I should keep my for-food beans far away from my

for-beauty beans in the future.

On a semi-related note, our experimental fava beans

have come up! The seedlings look more like peas than like beans,

which is probably because fava beans are really a vetch. We hope

to experiment with eating both the fava bean seeds and the scarlet

runner bean seeds at lima bean stage...even though I don't think I've

ever eaten lima beans before in my life. For those of you who are

more experienced --- what kind of introductory recipe would you

recommend?

Our neighbor mentioned that

he uses a miter saw blade on his weed trimmer.

The arbor hole is the same

diameter as the Ninja

brush blade. Make sure the teeth point to the left to take

advantage of the cutting teeth.

I only tried it on some rag

weed and it was like a hot knife cutting through butter. Our neighbor reported

when he tried it the blade would bind up on even medium sized trees. I

think we don't need the little bit of extra cutting power for such a

huge leap in danger.

While we refer to our

"lawn" only in parentheses since the grass is full of dandelions,

clover, and whatnot and never gets fertilized (except with the chicken tractor), I do occasionally feel guilty about the grassy areas. Granted, on our farm, grassy garden aisles make sense,

but most like-minded people think all lawns are evil. However, as

I mowed Thursday, I started wondering whether the carbon dioxide coming

from our mower might not be offset by the carbon being sequestered in

the soil as grass blades and roots turn into humus.

Sure enough, independent

scientists (in addition to the lawn-care "scientists" you might expect

to feel this way) report that lawns do act

as carbon sinks. A minimal input lawn like ours that only gets

mowed with no other treatment sequesters about 147 pounds of carbon per

lawn per year (after you subtract out the carbon released by the

mower). The abstract I read didn't mention lawn size, but I'm

assuming they're using the American average of a fifth of an acre, which

matches up with another study that reports each acre of lawn sequesters

a net of 760 pounds of carbon per year.

Of course, cover crops

will put the puny carbon sequestration powers of a lawn to shame.

Sorghum-sudangrass will pump a massive 10,565 pounds of carbon per acre

into the soil, and oilseed radishes don't do so bad either at 3,200

pounds of carbon per acre. In fact, a 120-year-old northeastern

woodland only clocks in around the carbon sequestration powers of

oilseed radishes, and you can still grow tomatoes in the oilseed-radish

ground during the summer.

Which is all a very long

way of saying --- if you're considering making a patio or leaving that

area as lawn, go for the lawn. But if you really want to sequester

carbon fast, plant some cover crops.

Thanks for the comments on using a

miter saw blade with a weed trimmer.

Most people are like my

neighbor and report problems with it binding up when cutting small

trees which could be a result of not keeping the blade exactly even

during a cut.

Maybe in the future Stihl

will invent some sort of LED indicator you could look at and know which

way to tilt the blade to make the most level cut.

A few weeks ago, we noticed a drastic decline in the number of eggs coming out of our coop. As day length decreases, it's normal to notice fewer eggs,

but a hen's lay usually drops off gradually rather than all at

once. Added to the mystery, some days our egg haul was back to

normal, followed by a series of days with only one or two eggs in the

nest box. What was going on?

Mark solved the mystery

when he found a black rat snake sunning itself outside the coop in the

middle of August. For a while, we gathered eggs earlier in the

day, and the snake seemed to have moved on, but numbers once again

declined this past week. Sure enough, this time Mark caught the

snake in the act, its body swollen around an egg.

Black

rat snakes are completely non-poisonous, and from my days as a

naturalist, I know most are actually pretty friendly too. But I

still didn't feel comfortable just picking up the snake (which I planned

to relocate to the other side of the hill).

Instead, I tried pushing the snake into a bucket, then I ended up