archives for 09/2013

Next month, we'll be swapping over to the

other composting

toilet hole,

but I wanted to go ahead and put

the roughage on the bottom now while I have corn stalks available.

Learning from our

mistakes, I asked Mark to use some of the better junk tin

from the barn roof replacement to cover up the cracks in the walls

of this new chamber.

Next month, we'll be swapping over to the

other composting

toilet hole,

but I wanted to go ahead and put

the roughage on the bottom now while I have corn stalks available.

Learning from our

mistakes, I asked Mark to use some of the better junk tin

from the barn roof replacement to cover up the cracks in the walls

of this new chamber.

"I told you so!" Mark

crowed. He did indeed. Back when we initially designed

the composting toilet, I adamantly refused to make the walls

solid, but Mark's gut reaction was right. I'm glad he's

still willing to fix my design flaws even though he knew better

from the beginning.

A third or fourth appendage would be helpful on a job like this, but the next best thing for holding a piece of sheet metal in place is one of those medium to large plastic spring clamps.

I rustled up another early Virginia

Beauty apple

along with the first ripe Liberty apple so that Mark and I could

taste test them together. The Liberty we tasted had a

simpler flavor than the Virginia Beauty, wasn't as dense, and was

sweeter, all of which led to me giving it a lower score and Mark

giving it a higher score than the Virginia Beauty. (We have

slightly different apple tastes.) For the record, here are

our variety ratings so far for our homegrown apples:

I rustled up another early Virginia

Beauty apple

along with the first ripe Liberty apple so that Mark and I could

taste test them together. The Liberty we tasted had a

simpler flavor than the Virginia Beauty, wasn't as dense, and was

sweeter, all of which led to me giving it a lower score and Mark

giving it a higher score than the Virginia Beauty. (We have

slightly different apple tastes.) For the record, here are

our variety ratings so far for our homegrown apples:

| Variety |

Mark |

Anna |

| Early

Transparent |

6 |

7 |

| Virginia Beauty |

7 |

9 |

| Liberty |

7.5 |

7 |

Yet to come in this year's spectacular

fruiting run is six Enterprise apples from our high-density

planting. I had fun lifting up leaves close to the

Enterprise fruits and seeing green spots where the fruit was

hidden from the sun, a bit like developing images on sun-sensitive

paper. Some people even stick paper shapes onto their apples to

create specially-colored fruits, but I let nature do the work for

me.

Yet to come in this year's spectacular

fruiting run is six Enterprise apples from our high-density

planting. I had fun lifting up leaves close to the

Enterprise fruits and seeing green spots where the fruit was

hidden from the sun, a bit like developing images on sun-sensitive

paper. Some people even stick paper shapes onto their apples to

create specially-colored fruits, but I let nature do the work for

me.

Even though all of the apples were accounted

for, there was one more fruiting surprise waiting for me.

Last year at this time, the first

Chicago Hardy fig was ripening up, but the fruits all looked

stiff and green on Monday, so I figured they were running

late. Then, out of the blue, a fig tripled in size

Wednesday, and by Saturday there were three ready to eat!

The fruits are huge and numerous this year --- maybe we'll be able

to eat our fill for the first time?

Even though all of the apples were accounted

for, there was one more fruiting surprise waiting for me.

Last year at this time, the first

Chicago Hardy fig was ripening up, but the fruits all looked

stiff and green on Monday, so I figured they were running

late. Then, out of the blue, a fig tripled in size

Wednesday, and by Saturday there were three ready to eat!

The fruits are huge and numerous this year --- maybe we'll be able

to eat our fill for the first time?

We've had some troubled hens

escaping from their pastures lately and we also have some areas of the

garden that could go for some agressive chicken scratching.

The solution seemed obvious

after Anna suggested it. Tune up our last remaining chicken

tractor for some End of

the Summer poultry powered weed eating and fertilization.

It only took an hour to get

this tractor back in running order. I think it's held up pretty good

for being out in the elements these past 4 and a half years.

"I was wondering if there

is something you do to your fruit trees each year to help them

grow.

I have just started doing that espalier

thing for my trees. It is their first year, I put in aged horse

manure and mulch around each tree. But I was wondering what type

of annual chores your do for your trees."

"I was wondering if there

is something you do to your fruit trees each year to help them

grow.

I have just started doing that espalier

thing for my trees. It is their first year, I put in aged horse

manure and mulch around each tree. But I was wondering what type

of annual chores your do for your trees."

I'm a very hands-on

gardener, so even our fruit trees (the lowest -maintenance parts

of our garden) get a lot of care scattered throughout the

year. It starts with pruning

and feeding each tree in late winter, the latter generally being a

topdressing

of horse manure scattered very lightly underneath the

canopy. In a perfect world, I would mulch each tree at the

same time I fertilize it, then keep topping up the mulch as needed

throughout the year, but in reality our older trees tend to have

small weeds grow up underneath by summer, then Mark cuts the

growth back a couple of times with a weedeater. If I have

extra cardboard, I may lay down a kill mulch instead, which is

particularly handy around younger trees who can't stand much

competition.

Younger trees also get more

structural attention in the summer when I prune a second time (removing

watersprouts) and train the limbs into shape. At the

moment, I'm training

peaches to the open center system (which I love) and apples

to the central-leader system (which I'm not as sure about

yet). After they start fruiting, most trees will begin to

maintain their shape on their own and will need less summer

pruning and training, but the warm-weather attention is very handy

with young trees since it keeps them on track to produce the

growth you really want while they're small.

Younger trees also get more

structural attention in the summer when I prune a second time (removing

watersprouts) and train the limbs into shape. At the

moment, I'm training

peaches to the open center system (which I love) and apples

to the central-leader system (which I'm not as sure about

yet). After they start fruiting, most trees will begin to

maintain their shape on their own and will need less summer

pruning and training, but the warm-weather attention is very handy

with young trees since it keeps them on track to produce the

growth you really want while they're small.

Speaking of fruit, I start

paying attention to the developing fruits as soon as the petals

drop. I worry myself sick about late frosts (although I've

yet to come up with any preventative that works there), then after

the last freeze, I thin

the tiny fruits hard. I think thinning is one of the

most-overlooked aspects of getting high-quality fruit in the

backyard --- don't skip it! I also perform some pest

management, which mostly consists of removing troubled fruits and

twigs.

Speaking of fruit, I start

paying attention to the developing fruits as soon as the petals

drop. I worry myself sick about late frosts (although I've

yet to come up with any preventative that works there), then after

the last freeze, I thin

the tiny fruits hard. I think thinning is one of the

most-overlooked aspects of getting high-quality fruit in the

backyard --- don't skip it! I also perform some pest

management, which mostly consists of removing troubled fruits and

twigs.

Finally, I pick

and pick and pick! I've learned that fruits on the

same tree don't ripen all at once, and I get a much better harvest

if I pluck

early fruits as soon as they start to develop infection,

then keep picking problematic or particularly ripe fruits as the

season proceeds. We gorge on fruits, dry them, then give

extras away or experiment with other preservation techniques.

Finally, I pick

and pick and pick! I've learned that fruits on the

same tree don't ripen all at once, and I get a much better harvest

if I pluck

early fruits as soon as they start to develop infection,

then keep picking problematic or particularly ripe fruits as the

season proceeds. We gorge on fruits, dry them, then give

extras away or experiment with other preservation techniques.

That's the bare bones of

our fruit-tree management schedule, but, of course, I'm always

experimenting with new techniques. For example, this summer,

I'm trying out sweet potatoes planted beyond the tree canopies

then used as a living, noncompetitive groundcover under the

trees. Last winter, I started experimenting with grafting

new varieties onto medium-sized pear trees, and next year my

dwarfing apple rootstock will be big enough to stool

and propagate to extend our high-density

planting. But that's all advanced tree husbandry ---

the techniques mentioned previously should be enough to get you

off to a very good start.

That's the bare bones of

our fruit-tree management schedule, but, of course, I'm always

experimenting with new techniques. For example, this summer,

I'm trying out sweet potatoes planted beyond the tree canopies

then used as a living, noncompetitive groundcover under the

trees. Last winter, I started experimenting with grafting

new varieties onto medium-sized pear trees, and next year my

dwarfing apple rootstock will be big enough to stool

and propagate to extend our high-density

planting. But that's all advanced tree husbandry ---

the techniques mentioned previously should be enough to get you

off to a very good start.

Clamping a block onto the

side of the Milwaukee

M12 PVC shear cutter

allows me to cut small pipe sections at the same length without

measuring and marking.

Why am I cutting several

small sections of PVC pipe? To make the new and improved EZ miser chicken waterer.

I always mean to work

a bit harder on getting my homegrown mushroom production perfected

so we can pick mushrooms whenever we want. The trouble is

that the woods  churn out high-quality oyster mushrooms with

such regularity that I have little incentive to get my act

together.

churn out high-quality oyster mushrooms with

such regularity that I have little incentive to get my act

together.

It's hard to complain, though, when the box-elder by the barn

provides the main ingredient for wild-mushroom-and-basil pesto for

lunch, then for mushroom green beans for supper. Delicious!

It's time to vote on your

favorite entry in our "I

wish I'd known" chicken contest! I've summed up all the entries here, and you can vote by

commenting on the relevant post over on our chicken blog or by

liking or commenting on the relevant post on our facebook

page.

We're looking forward to sharing an EZ

Miser with the

winner and an Avian Aqua

Miser Original

or a DIY kit with the runnerup.

Voting ends Friday!

It's time to vote on your

favorite entry in our "I

wish I'd known" chicken contest! I've summed up all the entries here, and you can vote by

commenting on the relevant post over on our chicken blog or by

liking or commenting on the relevant post on our facebook

page.

We're looking forward to sharing an EZ

Miser with the

winner and an Avian Aqua

Miser Original

or a DIY kit with the runnerup.

Voting ends Friday!

I think there might be a

better way to haul lumber on the ATV.

Maybe some kind of wooden

holder that goes on the front and back to extend the rack surface area

by 7 or 8 inches on each side?

What does early fall

look like on our farm? It's all about fall colors, fall

flowers, and (of course) the fall garden.

For us, fall colors come in the form of red peppers. Since

we prefer our peppers ripe and raw, I don't put in the effort to

start a bunch of plants early. Instead, we just wait until

the days start to chill down for this annual treat. (We also

have the more traditional fall colors in the woods, with buckeyes

and blackgum having colored up weeks ago.)

The fall flowers, of

course, are still blooming like crazy. I particularly enjoy

the jewelweed, which attracts hummingbirds (and is so easy to rip

up that I let it go to seed even at garden edges). All these

fall flowers mean the nectar

flow is

continuing, and bees (wild and cultivated) are everywhere.

The fall garden is up

and running, too, although we're not eating from it yet. I

figure pea flowers a week ago mean we'll get our first succulent

nibbles soon.

While we wait, I've been counting the rather excessive number of

Brussels sprouts I installed this year. Last year, only

four plants were in a sunny enough spot to bear, and we

loved the vegetable so much we opted to quadruple its square

footage this year. But then I got spooked by the early onset

of tomato blight and set out another dozen or so Brussels sprouts

between the ailing vines. Is it possible we'll get sick of

Brussels sprouts this winter?

Any signs of fall

showing up in your neck of the woods?

Got the Star

Plate chicken coop doors

installed today.

We'll use the small door for

most visits and keep the big one closed except for when we need to get

a wheel

barrow in to replenish the deep

bedding.

I used hardware cloth on the

screen door to increase ventilation.

After reading about my experiments

with low-sugar jamming, one of our readers kindly sent me several packages of Pomona's

Pectin to

try. (Thank you, Rhonda!)

After reading about my experiments

with low-sugar jamming, one of our readers kindly sent me several packages of Pomona's

Pectin to

try. (Thank you, Rhonda!)

Pomona's Pectin was

discovered by Euell Gibbons' diabetic brother who experimented

with various ways to create low-sugar jam. Gibbons learned

that the pectin in citrus peels (low-methoxyl pectin) uses calcium

phosphate (the form of calcium found in cow's milk) instead of

heat and sugar to create a gel. Modern homesteaders repeat

Gibbons' feats the easy way by purchasing Pomona's Pectin, which

comes with both the low-methoxyl pectin and the calcium phosphate.

With Pomona's Pectin,

you can use much less sweetener than with normal jams (about 0.25

to 0.5 cups of sugar or equivalent per cup of fruit), and you can

also use sugar-substitutes like honey. I won't repeat the

jamming instructions here, since they come in each box of

pectin. But the upshot is that you mix the calcium with

water, put a bit of calcium water (and lemon juice) in your pureed

fruit, mix the pectin with your sweetener, then bring the fruit

mixture to a boil, add the pectin, and bring it all back to a

boil. You can eat the jam as-is, or can it in a hot-water

bath.

I was nearly out of

peaches by the time my Pomona's Pectin arrived, so I only made one

batch of jam with frozen puree and honey. The result was

delicious --- a lot like freezer jam, but less sweet and thus

fruitier. It didn't gel as well as some of my other jams,

but I suspect tweaking the recipe would have fixed that

problem. I guess I'll have to wait and report back during

jamming season next year!

It's been less than a year

since we put in new apple trees with the high

density method.

One tree died, but the rest

look great. The Enterprise tree has 6 full size apples!

When I laid out my

plantings on the north side of the trailer, I figured I'd fill in

as much space as possible, then take things out as necessary when

the trees got bigger. So I included vegetable garden,

brambles, and even a clothesline in areas that will be  beneath the eventual canopy spread of my

trees.

beneath the eventual canopy spread of my

trees.

The great thing about

the fill-it-in-from-the-beginning method is that there's less

mowing and high yields right away. The bad part is that I

actually have to rip out those plants that are now making it

impossible to walk around our peach tree.

I plan to soften the

blow by replacing some of the shadowed blackberries with a home-propagated

gooseberry. And maybe I can move one of the

blackberries over a few feet and get in another year or two of

production?

Making a Star

Plate door extra big has

a price to pay.

You need to cover a half wall

section on each side.

Metal roofing panels are easy

to attach once you get it cut to size.

I go back and forth

on the issue of swarm management. For years, I very

successfully managed

my hives so they wouldn't swarm, but this year I toed the Warre line and let my

hive release a swarm.

Before I go into the

results of that swarm, I figured I should back up and tell those

of you without bees a bit about why hives swarm. If it's

healthy, most bee hives have the impulse to reproduce in the

spring, but they reproduce at the super-organism level. So,

rather than producing an apple like a tree does, a bee hive

produces a swarm, complete with everything needed to start a new

colony (queen and workers).

Unfortunately, a hive

that puts all that energy into building a swarm tends not to put

away much honey. Which is why so many beekeepers manage

hives to prevent swarms. On the other hand, my autumn varroa

mite counts

confirmed the big benefit of allowing swarming in a chemical-free

bee hive. Our mother hive (which released a swarm this

spring) had a grand total of 6 varroa mites on the sticky board

after a three day count, and the swarm we caught dropped only 1

mite during the same three days. In contrast, the sticky

board beneath the package we purchased this spring contained 86

mites.

To put those numbers

in perspective, you have to estimate

how many mites that would be per thousand bees in the hive (or at least guesstimate

the relative size of the colonies). This year's package hive

is one of the strongest I've raised, so it's to be expected that

more bees would host more mites. However, I can't imagine

there are more than twice as many bees in the package hive

compared to the other two colonies, so swarming definitely helped

break the pest cycle in the other two hives.

Whether the benefits

of swarming will outweigh the lower honey yields on our farm is

yet to be seen. I'd really love to eventually develop a

beekeeping method that both keeps bees alive without chemicals and provides sweet treats

for the beekeeper.

They decided it made a perfect jungle gym.

Permaculture is all about stacking, right?

Congratulations to Robin and Eva, who won free chicken

waterers as part of our last contest! Since we've finally

perfected the EZ

Miser enough that we're selling it in kit form (10%

off this week!), we decided to celebrate with another contest.

Congratulations to Robin and Eva, who won free chicken

waterers as part of our last contest! Since we've finally

perfected the EZ

Miser enough that we're selling it in kit form (10%

off this week!), we decided to celebrate with another contest.

To enter,

email anna@kitenet.net with one or more photos

and your answer to this question: "What is your favorite

chicken variety and why?" To make this round a bit

fairer, we'll be judging the winners ourselves so it doesn't turn

into a popularity contest.

The fine print: All entries

must reach my inbox by Sunday (September 15) at midnight. Be

sure to send photos one at a time if they're larger than 2 MB

apiece. Mark and I will choose winners based on quality of

the photos and written explanation. All photos and text will

become the property of Anna Hess, which means I might share them

with readers via our blogs or ebooks.

Winners: The grand-prize winner will receive your

choice of a premade EZ Miser or a 4 pack EZ Miser kit,

and the second-place winner will choose between a 3

pack DIY kit, 1

Avian Aqua

Miser Original,

or a 2 pack EZ Miser kit. I look forward to

receiving your entries and to sharing clean water with your flock!

(And don't forget to

spread the word among your chicken-keeping friends about our new

EZ Miser kits. We learned from our mistakes last time around

and have a bunch of kits stockpiled, so you won't see a decline in

post quality if we have to fill a deluge of orders. Thanks

for your help keeping Walden Effect running!)

We spent most of today on EZ Miser production.

Our new source for 2 gallon

buckets is the local hardware store in St Paul.

Kayla recommended that I check out Carol W.

Costenbader's The

Big Book of Preserving the Harvest, and since the text was available at my

local library, I figured I didn't have anything to lose.

With chapters on canning, drying, freezing, jams, pickles,

vinegars, and cold storage, this initially looked like the go-to

reference for every well-rounded homesteader to have on her

shelf. Closer scrutiny, though, showed that the recipes

included are more fancy and less basic than you'd want if this was

your single reference guide.

Kayla recommended that I check out Carol W.

Costenbader's The

Big Book of Preserving the Harvest, and since the text was available at my

local library, I figured I didn't have anything to lose.

With chapters on canning, drying, freezing, jams, pickles,

vinegars, and cold storage, this initially looked like the go-to

reference for every well-rounded homesteader to have on her

shelf. Closer scrutiny, though, showed that the recipes

included are more fancy and less basic than you'd want if this was

your single reference guide.

On the other hand, The Big Book of Preserving the Harvest shines in the chapter

introductions, where Costenbader walks you through all of the

basic techniques for each preservation method. I was

particularly taken with the canning section since I haven't canned

extensively and didn't know that people at higher altitudes might

need to leave more head space (so that's why my peach sauce

erupted!) and that minerals in your water can cause the top layer

of canned food to turn brown or gray even though it's still

perfectly safe.

When I first started

the book-learning part of my homesteading education about 15 years

ago, Stocking

Up seemed like

the best option for an all-around basic preservation guide, but

since then I've mostly gravitated toward websites. What

resources do you use when you want to know how long to blanch your

green beans before freezing and how much head space to leave on

top of your canned tomatoes?

The latest

nest box addition worked

out so well we decided to make another one.

We've got more chickens in

this coop so I made it a double.

I thought the front roost

extension would help lure in the more curious chickens and then it

should turn into a game of follow the leader.

Two readers left comments last week on old

posts about amaranth

we grew for grain a few years ago, which reminded me I wanted to share my

experience with growing amaranth for greens. Generally,

you'll choose either a greens or a grain variety when you plant

(although, presumably, both are multi-purpose to a certain

extent). Our first experiment, when growing grain amaranth,

was with Manna de Montana, which I had trouble getting to

germinate but which then grew into huge plants and produced lots

of seeds. (We didn't even sample the leaves because I didn't

know they were edible at the time.) Joe (a reader) kindly

sent us some seeds for Mayo Indian amaranth this year, mentioning

that he likes the variety for greens, so we decided to give it a

shot.

Two readers left comments last week on old

posts about amaranth

we grew for grain a few years ago, which reminded me I wanted to share my

experience with growing amaranth for greens. Generally,

you'll choose either a greens or a grain variety when you plant

(although, presumably, both are multi-purpose to a certain

extent). Our first experiment, when growing grain amaranth,

was with Manna de Montana, which I had trouble getting to

germinate but which then grew into huge plants and produced lots

of seeds. (We didn't even sample the leaves because I didn't

know they were edible at the time.) Joe (a reader) kindly

sent us some seeds for Mayo Indian amaranth this year, mentioning

that he likes the variety for greens, so we decided to give it a

shot.

I planted the

amaranth late (in mid-July), but it still jumped right up and grew

like crazy. The plants have a reddish tinge to the leaves

and produce red seed heads so pretty that my mom put some in a

vase as an ornamental after coming to visit. I wasn't as

keen on the taste, though. The leaves were edible, but when

raw they had a mucilaginous texture like sassafras leaves

(interesting in small amounts, but you wouldn't want to eat a lot

of them), and cooked the flavor didn't stand up to that of our

summer favorite, Swiss chard.

On the other hand,

after a search of the internet, I discovered that Mayo Indian

amaranth is usually grown for the grain, so I guess I've yet to

try a true greens amaranth. Anyone have a favorite variety

to recommend?

Today was the day our new

chicks decided to explore what's on the other side of the trailer.

Soon they'll be big enough to

scratch up mulch, but before that we'll move them to their own private

pasture.

People throw around

the term "symbiosis" all the time, but most don't realize that the

word only means that two (or more) organisms are living close

together, not that they're helping each other out. Symbiotic

relationships can be parasitic (one organism benefits and the

other is harmed), commensalistic (one organism benefits and the

other is neutral), or mutualistic (both organisms benefit).

Why should you

care? If you're a permaculturalist trying to build guilds or

an organic gardener experimenting with companion planting, it's

handy to know where your combinations sit on the

mutualism-to-parasitism spectrum. That way you can grade the

interactions --- parasitism is probably a failure, commensalism is

a moderate success, and mutualism is the holy grail of the guild

world.

While my sweet-potato

cover-crop experiment is closer to a commensalism than a mutualism, I'm so

happy with the results that I'm going to deem it a glowing

success. This spring, I set out sweet potato slips into some

beds I've developed just past the root zone of a peach and an

apple in the forest garden, and the sweet potatoes thrived.

They soon formed a living mulch beneath the trees, but only barely

rooted there, so they didn't steal any nutrients. When

harvest time came this week, I discovered huge, beautiful tubers,

and the tops of the sweet potatoes created a deep mulch ring

around each tree, perfect for taking the trees into winter.

Meanwhile, the bare ground left behind in the sweet potato beds

made it easy to sprinkle oat seeds for even more biomass

production.

What would turn this

symbiosis from a commensalism to a mutualism? If the sweet

potatoes had done better close to the trees than they would have

done in a vegetable garden bed. I'd be curious to hear if

you've developed any true mutualisms in your garden, but in the

meantime, I whole-heartedly recommend sweet-potato cover crops for

anyone needing to build biomass around fruit trees.

At first, I was

puzzled by the

box turtle I photographed for yesterday's post. Why

was she hiding under the sweet potato leaves when the

turtle-friendly zone is currently around the dropped raspberries

fifty feet away? Then I took a look at the turtle's chin and

realized she had been chowing down on slugs.

Some gardeners stop

mulching entirely after a few years because they feel the slug

populations get too high. We have seen an increase in

slugs since we started mulching seriously, but our resident

critters seem to keep them mostly in line. Along with box

turtles, other wildlife I've seen in our garden intent on slug

patrol include skinks, worm snakes,

garter

snakes, ringneck

snakes, shrews, mole

salamanders, wolf

spiders, and even (potentially) some species of slugs.

So far, the benefits

of mulch outweigh the negatives, but I suspect the tables would

turn if we tilled. Chopping up the soil would invariably

also chop up a lot of our slug predators, giving slugs the upper

hand. So maybe the moral is --- either till and don't mulch

or mulch and don't till.

Finished up the new

nest box with a proper

exterior door installation.

One brave Leghorn hen settled

in and sat there through all the construction noise.

I've always looked forward to Friday the

13ths. I figure if everyone else is sure they're going to

have bad luck on those days, there must be lots of good luck

floating around looking for a home, and if I focus, it'll stick to

me. Here's a disjointed account of all of my Friday the 13th

good luck.

I've always looked forward to Friday the

13ths. I figure if everyone else is sure they're going to

have bad luck on those days, there must be lots of good luck

floating around looking for a home, and if I focus, it'll stick to

me. Here's a disjointed account of all of my Friday the 13th

good luck.

I discovered that

slices of our Chicago Hardy figs dry quickly and taste

delicious. Yum!

Our curing

rack is now 100% full with winter bounty. I've moved

most of the onions inside to make room for butternuts and sweet

potatoes, and yet some spillover squash still have to cure on the

floor.

I dug out the

blackberries being shaded by the peach and discovered that

the soil left behind has been improved dramatically by five years

of mulch and compost tossed on top of the soil.

Transplanting one of the blackberries out of the shade zone and

into a hole in the lawn reminded me that most of that area is pure

clay with about an inch and a half of slightly-dark topsoil near

the surface. In contrast, the soil in the old blackberry row

is loose and dark for at least five or six inches down.

Thanks, worms!

I dug out the

blackberries being shaded by the peach and discovered that

the soil left behind has been improved dramatically by five years

of mulch and compost tossed on top of the soil.

Transplanting one of the blackberries out of the shade zone and

into a hole in the lawn reminded me that most of that area is pure

clay with about an inch and a half of slightly-dark topsoil near

the surface. In contrast, the soil in the old blackberry row

is loose and dark for at least five or six inches down.

Thanks, worms!

And, despite the

blight, we're still getting tomatoes! The Crazy (a large

tommy-toe), in particular, barely seems phased by the

fungus. Next time I think it's going to be a blight year, I

should include half a dozen plants of this productive variety in

our garden.

Anything lucky happen

to you on Friday the 13th?

Mowing this segment of our chicken

pasture system requires

moving within the flight path of hundreds of worker bees doing their

thing.

This hive has been a bit

aggressive the past few months, which is why I put the bee

suit on yesterday.

I was interested to see so many comments on

my post about eating

amaranth leaves,

especially Nita's suggestion of Orach as an alternative. We

may try Orach next year, but in the meantime I should report on

the other summer green we experimented with in 2013 --- Malabar

Spinach. (Thanks for the seeds, Shannon!)

I was interested to see so many comments on

my post about eating

amaranth leaves,

especially Nita's suggestion of Orach as an alternative. We

may try Orach next year, but in the meantime I should report on

the other summer green we experimented with in 2013 --- Malabar

Spinach. (Thanks for the seeds, Shannon!)

Malabar spinach is a

lot like amaranth in that I think it could slip into an urban

homestead's ornamental flower garden without raising

eyebrows. The flavor is superior to amaranth, in my opinion,

being very spinachy and mild (acceptable even for salads).

The main problem with

turning Malabar spinach into a main crop is that the plant is a

vigorous vine, so we'd have to provide a trellis. The one

pictured here grew sideways until it was able to take over the

stake I'd put in the ground beside our baby Issai kiwi, then

headed straight up.

I was quite content

with Swiss chard being our sole summer green until three years ago

when blister beetles showed up. Ever since, these night-time

nibblers have turned my Swiss chard into a mess of holes and

frass, with only the youngest leaves available for eating.

Maybe I should be focusing on blister beetle control, not looking

for a replacement summer green?

It took 2 ATV trips to haul 100 two

gallon buckets back to

the barn.

45 stack up nicely in the

back with 10 in the front.

Long-time readers will be aware that our

movie-star neighbor loves to harvest Autumn

Olive berries,

which he freezes for the winter and also turns into delicious fruit

leather.

His farm is overrun with the invasive bush, so he only has to walk

a few feet from his door to pick, but that picking can be

time-consuming. So this year, our neighbor developed the

Berry Apron, a DIY picking tool to make his harvests even

easier. You can follow along at home.

Long-time readers will be aware that our

movie-star neighbor loves to harvest Autumn

Olive berries,

which he freezes for the winter and also turns into delicious fruit

leather.

His farm is overrun with the invasive bush, so he only has to walk

a few feet from his door to pick, but that picking can be

time-consuming. So this year, our neighbor developed the

Berry Apron, a DIY picking tool to make his harvests even

easier. You can follow along at home.

The first step is to

take a length of PVC pipe like you'd use for quick

hoops and thread a rope through it. It's even better

if the pipe has already been used for quick hoops and has

developed a bend. Using this bend (or what you envision the

bend would be) as a guide, sew a channel into an old sheet (the

same way you'd make the top of a curtain fit over a curtain rod),

then push the pipe (with its embedded rope) through. Tie the

ends of the rope  together to pull the pipe

into a solid curve, then make a hole at the peak of the pipe's

curve to attach another rope, which will go around your

neck. Finally, use a bungee cord to secure the Berry Apron

around your back, and you're ready to pick.

together to pull the pipe

into a solid curve, then make a hole at the peak of the pipe's

curve to attach another rope, which will go around your

neck. Finally, use a bungee cord to secure the Berry Apron

around your back, and you're ready to pick.

The great thing about

the Berry Apron, my neighbor reports, is that it lets you pick

with both hands at once without worrying about channeling the

berries into a bucket. He and Nellie (pictured above)

plucked about two gallons of Autumn Olive berries into their Berry

Aprons in about half an hour, and he could envision using the same

aprons with highbush blueberries or any other non-thorny bush

berry.

I'll be curious to

hear if anyone else tries the Berry Apron and streamlines the

process. Our neighbor was already thinking that version 2.0

might be made with a screen instead of cloth, so bugs and dirt

fall through. Any other suggestions to make this good idea

even better?

One advantage to not having a

mother hen raising new chicks is a reduced foraging perimeter.

We like to have our new chicks near the garden without being

close enough to do any real damage.

Moving the brooder a hundred feet seems to reset

their foraging zone, but when they're this big we start fencing them in

over by the barn with some temporary plastic fence.

I've noticed by

reading back over old posts that I tend to be less than enthralled

with just about every cover crop the first time I grow it, so take

this with a grain of salt, but...I'm less than enthralled with sunn

hemp.

Here are the negatives that jumped out at me this summer:

- Japanese beetles adore the plants, which meant I either had to extend my beetle-plucking to the cover crop beds (and cover crops are supposed to be no work) or let our beetle population expand.

- Sunn hemp doesn't cover the ground quickly (or, really, at

all) since it grows up instead of out, meaning that weeds pop up

in the bare soil around sunn hemp's feet. I didn't pull

them because cover crops aren't supposed to have to be weeded,

so our forest garden has a lot of tall weeds getting ready to go

to seed.

- I don't feel like I got nearly as much biomass production per

unit area with sunn hemp as with sweet

potatoes, and sunn hemp didn't provide an edible return.

- Sunn hemp can't handle the more-waterlogged parts of our

garden (but, then, only oats and rye have thrived there).

All of that said,

sunn hemp is pretty,

especially now that it's starting to bloom. And the plants

are legumes, so they fix nitrogen, which my other cover crops

don't do. Still, they failed to meet my two primary goals

for cover crops (maximum biomass production and weed suppression),

so I don't think we'll try sunn hemp again.

One of the Georgia

work boots started leaking. I make a point not to submerge them in

water, but today some wet grass was enough to make one of my socks damp.

I'm pretty disappointed in

the longevity. It was a wet year, which meant most of the time during

this 11 month trial I was wearing my Muck boots,

which are still going strong, and there was no walking around

construction sites with nails pointing up.

Maybe the next brand I try

will come closer to feeling like a fair deal?

The last new-to-us apple variety we got to

taste this year was Enterprise, from one of our high-density

trees. The apples were big and beautiful, and their flesh

was crisp and just the right texture, which is probably why Mark

gave the variety his highest rating of the year --- an

8. I only rated the flavor a 5, though, because I felt it

lacked the complexity (and particularly the tartness) you'd find

in my current favorite (Virginia Beauty). In fact, I'd say

the Enterprise we tasted had a flavor very much like a

top-of-the-line Red Delicious.

The last new-to-us apple variety we got to

taste this year was Enterprise, from one of our high-density

trees. The apples were big and beautiful, and their flesh

was crisp and just the right texture, which is probably why Mark

gave the variety his highest rating of the year --- an

8. I only rated the flavor a 5, though, because I felt it

lacked the complexity (and particularly the tartness) you'd find

in my current favorite (Virginia Beauty). In fact, I'd say

the Enterprise we tasted had a flavor very much like a

top-of-the-line Red Delicious.

On the other hand, a

bit of research suggests that I might like Enterprise better after

a month or two in storage. The developers

of Enterprise report: "Flavor is sprightly at harvest but

mellows to moderately subacid after storage." (I've come to

realize that "sprightly" in apple descriptions is what I call

"insipid".) Enterprise is a good keeper, lasting up to six

months in storage, so maybe when we have more than six fruits to

enjoy, I'll be able to run a second taste test with aged apples.

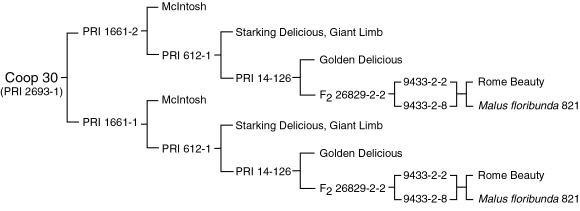

By the way, did you

notice I wrote "the developers of Enterprise" above? I chose

a mix of heirloom varieties and new developments for our high

density planting, and Enterprise is one of the latter. This

modern apple came out of the Purdue-Rutgers-Illinois cooperative

apple breeding program (thus the "pri" in the name) using the

crosses shown above. I'm definitely impressed by how well

the scientists imparted disease-resistance in the variety since

Enterprise has fared the best of all our new varieties in our

chemical-free orchard, but the taste issue is still up for debate.

Congratulations to

the winners of our chicken

variety contest! We had  an astonishing number of good entries, so I

made Mark choose the winners. (Otherwise, you all would have

gotten prizes.)

an astonishing number of good entries, so I

made Mark choose the winners. (Otherwise, you all would have

gotten prizes.)

First place went to

Julie for the beautiful shot above of her grandkids and their

Salmon Faverolles. ("Three models for the price of one!"

Mark exclaimed.)

Second prize went to

Kaat who captured the whiskers on her Ameracauna perfectly.

Honorable mention

(but, unfortunately, no prize), went to Kathleen's Buff Orpington:

...Edith's Buff Orpingtons:

...and Pamela's

ISA Brown who survived a neck injury and bounced back in three

days:

To hear more about

these and other breeds, stay tuned to our chicken blog over

the next few weeks. And a huge thank you to everyone who

entered!

It's that time of year when the kitchen screen door gets closed up until warm weather 2014.

Garlic week is

bittersweet. This is our last big planting push of the year

--- sixteen beds of garlic and potato onions. All that's

left to plant this year after the alliums go in is four final beds

of lettuce, plus rye anywhere I can fit the cover crop in.

The weather seemed to

want to drive the message home, with the first cold rains of the

year falling Wednesday. I closed the windows and asked Mark to

seal off our screen door, then settled in to make fall comfort food. Chicken

soup with the first of the fall carrots and a butternut pie with

the first of the winter squash remind me that cold weather is a

time of good food, deep thought, and writing.

This modification should help us to haul out some garbage and bring in some saw dust.

Until this year, I

didn't realize there was a right and a wrong way to pick

apples. Of course, it's important to wait until the apples

are at their peak ripeness, signs of which include dropped apples,

seeds turning brown or black, the green on the apple turning

yellowish, and (most importantly) the apples tasting ripe.

But once you've determined that your apples are ready to harvest,

you shouldn't just go out and yank the fruits off the tree.

To understand why

not, let me back up and zoom in on the top of an apple.

Fruits like peaches develop on first year wood, but apples are

different. In most apple varieties, flower buds form only on

spurs, which are second-year-and-older, short branches. The

same spur that's holding up this year's apple is also where next

year's flowers are forming, and if you're not careful, you'll rip

the flower buds off right along with this year's fruit, meaning no

apples next year. In the photo above, you can see next

year's flower bud as a pointy structure on the top, left side of

the apple.

To pick an apple

without damaging the spur, you want to lift and twist rather than

yank. You can do this one-handed, but at first you might

want to use two hands, holding the branch steady with one while

twisting the apple with the other.

Using this technique,

Mark and I harvested all of the apples from our 4.5-year-old

Virginia Beauty yesterday and got about a third of a bushel.

This is the first year our tree has produced, so I figure that's a

pretty good haul (especially considering that I've eaten at least

a third as many more over the last three weeks. I had to

consume the split

apples so they

wouldn't rot, and they tasted so good I just kept eating...).

I sorted the apples

and stacked them from best to worst in our crisper drawer.

If we had more, I'd put the fruits away in the fridge

root cellar, but at the rate I'm going through them, these

apples won't last another month. And the crisper drawer was

empty, having stored spring carrots, peaches, and now apples, with

fall carrots not coming in until next month. It's hard to

explain how satisfying it feels to be harvesting (and eating) so

much homegrown food.

Finished up the ATV

garbage hauling hitch receiver platform holder today.

A bungee cord holds it at the

bottom with a ratchet strap near the middle.

I can see a future

modification to hold some extra buckets of horse manure for 2014.

"Today's Talk Like a

Pirate Day...and I forgot to celebrate it...again!" I exclaimed to

Mark Thursday.

"You mean today's our

anniversary?" he replied.

I wracked my brain, trying

to remember when

we got married.

"Oops, um, yeah." Then, picking up steam, "So it's pretty

special that we harvested

the apples from our Virginia Beauty today because it's our

wedding anniversary!"

I wracked my brain, trying

to remember when

we got married.

"Oops, um, yeah." Then, picking up steam, "So it's pretty

special that we harvested

the apples from our Virginia Beauty today because it's our

wedding anniversary!"

"That's right!" Mark

agreed. "My

aunt gave us that tree from her neighbor's heirloom apple nursery

as a wedding present."

"I guess I should

have gotten you something for this anniversary, huh?" I mused,

then wandered off to google the traditional gift for a fourth

anniversary. "Fruit or flowers!" I exclaimed. "And you

got me fruit today!"

"Well, really, you got me fruit," said Mark,

referring to the way I cut up the dropped apples for our

lunch. But I was intent, instead, on the fact that my sweet

husband had reached high into the tree to pluck the apples over my

head, then shaken the trunk to get the last four from the

tippy-top to fall.

Husband-wife apple-picking --- the best anniversary gift

ever! We may have to pretend it's our fourth wedding

anniversary every year, although next year's traditional gift

(wood) sounds pretty good. Maybe it will equate to an

extra-full woodshed?

The three fig cuttings are now fully established and looking great in the forest garden.

Long-time readers will recall that my young

forest garden

sits in an area where all of the topsoil has eroded away and where

the groundwater pools right at the surface during wet

seasons. My solution to this extremely-troubled growing area

is create my own topsoil, raising the trees' roots up out of the

groundwater as quickly as I can.

Long-time readers will recall that my young

forest garden

sits in an area where all of the topsoil has eroded away and where

the groundwater pools right at the surface during wet

seasons. My solution to this extremely-troubled growing area

is create my own topsoil, raising the trees' roots up out of the

groundwater as quickly as I can.

As you can see in the photo above, sometimes that's not quickly

enough. The apple tree in the worst part of the forest

garden had to be staked this year because it had no place to put

taproots, resulting in a leaning trunk. In contrast, its

age-mate to the right is thriving in the slightly-better soil not

far away.

This long

introduction is all to explain why, over the last few years, I've

been focusing most of my forest-gardening energy on building

biomass, with some techniques working better than others. My

hugelkultur

donuts were the

best option, but they depend on masses of punky firewood and we've

been doing a better job lately of making sure our firewood stays

dry and gets burned. So I've instead been growing cover

crops (like sweet

potatoes) just

past the root zone of my fruit trees, then piling up the biomass

around the trees' roots to rot down into organic matter, building

soil while feeding the trees.

And then there's my brush

pile, shown to

the right in the photo above. All of the prunings from

berries and trees across our homestead end up in this pile, which

reaches over my head during pruning season but slowly rots down to

a gentle mound by this time of year. (Right now, the pile is

also topped by yanked-up cover crops and weeds from the

surrounding bed.)

You can also see how I kill-mulched under most of the fruit trees

last week to ensure they don't have to compete with weeds during

their fall-feeding

window, then

cleared ground further away to plant rye for winter biomass

production.

The result of all of

this biomass growing is happy trees covering two-thirds of the

forest garden. The last third just needs a little more TLC

before the soil is dry enough to really keep cover crops happy, at

which point the soil-improvement cycle will take off nearly by

itself. That area is where I'll concentrate any punky wood I

rustle up this winter. I seem to recall a couple of piles of

firewood in the floodplain that didn't get collected last winter

and are probably ripe for hugelkultur right about now....

First I placed a 3.5 foot 2x6

on top of the hitch

height adjuster and

traced the square hole.

Then I cut the hole out so it

sungs onto the metal with a short support on each bottom side.

10 inch decking boards go on

the sides to act as a wall and to have a place for the eye bolts where

the bungee cord gets secured.

19 inch decking boards are

used as the two extended supports with a 2x4 to level it out.

Last year, I had a

love affair with roasting

figs.

This year, I'm not as keen, probably because the figs are bigger,

moister, and don't roast quite the same way when halved.

Instead, I'm returning to my first love --- dried figs.

Our Chicago Hardy

tree has been in the ground just shy of 3 years, and it's already

starting to produce masses of figs. For the past week, I've

been able to pick a bowlful every other day, and the bowls keep

getting bigger. Sunday's bowl contained about a gallon of

figs.

Although it's a bit

wasteful of energy, I dry the figs right away rather than saving

them up in the fridge the way my father does until he has a full

dehydrator load. I wait to pick the figs until they're so

ripe the skins have cracked, and I don't want to risk any

spoiling. So I halved each fruit in my bowl and filled two

trays of the dehydrator, then sat back and waited for the rich

rounds to come out that afternoon.

Next year, I'll save

some of the dried figs for the winter. This year, I'm just

enjoying eating them up, in between bowls of raspberries and crisp

Virginia Beauty apples.

Teaming

with Microbes

was an eye-opening, readable, and beautiful guide to the

microscopic life of the soil, so I was thrilled to hear that one

of the coauthors was coming out with a book about plant

nutrients. Unfortunately, I was very disappointed by Teaming

With Nutrients.

Granted, the topic was a tough one to cover for a layman audience,

but the long descriptions of cell biology and chemistry felt like

a textbook written by an undergraduate, and I can't really

recommend the book.

Teaming

with Microbes

was an eye-opening, readable, and beautiful guide to the

microscopic life of the soil, so I was thrilled to hear that one

of the coauthors was coming out with a book about plant

nutrients. Unfortunately, I was very disappointed by Teaming

With Nutrients.

Granted, the topic was a tough one to cover for a layman audience,

but the long descriptions of cell biology and chemistry felt like

a textbook written by an undergraduate, and I can't really

recommend the book.

On the other hand,

after wading through pages and pages of textbookery, I did finally

find some useful information scattered here and there. I'm

going to share some tidbits about how nutrients move through the

soil and through plants in later posts in this lunchtime series,

and in the meantime you might want to check out Steve Solomon's The

Intelligent Gardener for a more hands-on approach to plant

nutrition. I'm still looking for a good book to school me on

the middle ground between these two extremes.

| This

post is part of our Teaming

with Nutrients lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Why are we making yet another

new

nest box?

We moved all the laying hens

into one coop due to overgrazing of a pasture.

Anna noticed one hen trying

to sit on her sister who was trying to lay an egg. This new double

sitter should fix that problem.

At this time of year,

I'm always torn in several directions. I want to weed and

mulch the fall crops so they'll get off to a good start, but I

also want to take some time to pull back weeds around the woody

perennials so the weeds don't go to seed. Luckily, this year

I have Kayla to help me out --- she can weed the carrots while I

hit the raspberries.

Even with Kayla's

help, though, I'm being a lazy weeder so that I can get to the

other time-sensitive garden tasks on my list (like finishing clearing

up the pastures).

I have a tendency to be obsessive about tasks like weeding, but if

I leave my trake behind and limit myself

to ripping up big weeds, I can work through a row of berries like

the one shown here in less than half an hour. Next up will

be a layer of newspaper to make up for the shoddy nature of my

weeding job, then some deep

bedding from the nearby chicken coop to feed the berries

during their fall root-growth spurt.

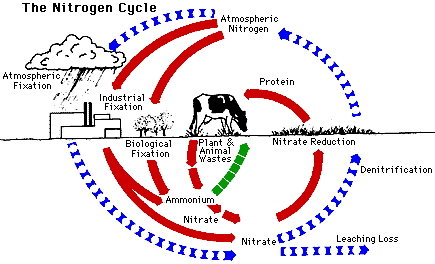

Jeff

Lowenfels' book

provided a handy way of dividing up plant nutrients --- by how

mobile they are in the soil. Understanding nutrients'

mobility helps explain why certain soil nutrients can be present

in the soil but unavailable for your plants, and why others might

not stay put when you add them to your garden.

Jeff

Lowenfels' book

provided a handy way of dividing up plant nutrients --- by how

mobile they are in the soil. Understanding nutrients'

mobility helps explain why certain soil nutrients can be present

in the soil but unavailable for your plants, and why others might

not stay put when you add them to your garden.

At one extreme lie

the nutrients that are very mobile in the soil and tend to float

into plants along with water. As long as there's enough

nitrogen in the form of nitrate, sodium, boron, and chlorine to go

around, you won't see deficiencies in your plants. On the

other hand, these mobile nutrients tend

to wash away in heavy rains, so those of you who live in

rainy climates like I do will want to make sure you provide mobile

nutrients only when plants are actively taking them up.

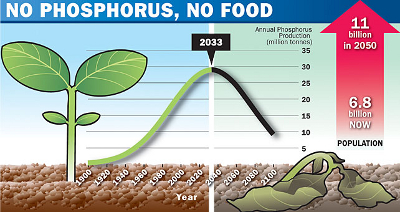

At the other end of

the spectrum, phosphorus, copper iron, manganese, and zinc (and,

in tropical soils, sulfate, nitrate, and chlorine) react

chemically to soil particles. Plants have a very tough time

taking in these nutrients without the help of mycorrhizal fungi,

so you can often see a deficiency in your plants even if (for

example) there's plenty of phosphorus in  the soil. This is

one reason why farmers worry about the world running out of

phosphate fertilizers --- they're pouring phosphorus into the soil

far faster than plants can use it rather than keeping the soil

healthy so fungi can bring plants the phosphorus that's already

there.

the soil. This is

one reason why farmers worry about the world running out of

phosphate fertilizers --- they're pouring phosphorus into the soil

far faster than plants can use it rather than keeping the soil

healthy so fungi can bring plants the phosphorus that's already

there.

In between these two

extremes lie most of the positively-charged nutrients, which are

attracted to soil particles a bit like a magnet to iron.

Roots have to trade a positively-charged hydrogen ion for each cation they take in (a process

known as cation exchange). These semi-immobile nutrients

include nitrogen in the form of ammonium, potassium, calcium,

magnesium, molybdenum, and nickel. If your soil is low on

these cations, it's probably because you haven't built up your

organic matter enough to hold them in place so your plants can

trade for them.

Stay tuned for

tomorrow's post to learn more about how plant nutrients make their

way into roots.

| This

post is part of our Teaming

with Nutrients lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Yesterday's nest box ended up forming a double decker nesting station.

Mulching with

newspapers is dangerous. If you're like me, you might get

sidetracked reading the headlines and take twice as long to put

down your kill mulch. Then your photographer will have to

take a look at an article on hops, and pretty soon you're just

sitting in the garden catching up on the news.

More seriously,

newspaper isn't my favorite kill layer in a mulch --- cardboard

works better and feeds the fungi more --- but the thinner paper

will do in a pinch. Both Mom and Kayla have been saving me

their newspapers, which is why I felt I could do a quick-and-dirty

weeding job Monday instead of ripping up every weed.

Another disadvantage

of newspaper is that it will blow away in even a mild breeze,

unlike cardboard which tends to stay put in our valley without any

help from above. I've started feeding our woody perennials

in the fall, though, so partially-decomposed deep bedding did a

great job weighing down the newspaper. In the end, the only

real problem is that there's never enough deep bedding to go

around --- clearly we need more animals!

Now that you

understand how

mobile nutrients are in the soil, it'll make more sense when I write about

how those nutrients get into roots. Root hairs (tiny roots)

are constantly growing, searching for new areas full of soil

nutrients so they can trade for cations and suck up anions.

The roots use calcium as a way of determining whether they're

growing in a good direction --- if calcium stops coming in (for

example, if the root hits a rock), the root hair stops growing.

Now that you

understand how

mobile nutrients are in the soil, it'll make more sense when I write about

how those nutrients get into roots. Root hairs (tiny roots)

are constantly growing, searching for new areas full of soil

nutrients so they can trade for cations and suck up anions.

The roots use calcium as a way of determining whether they're

growing in a good direction --- if calcium stops coming in (for

example, if the root hits a rock), the root hair stops growing.

At the same time

they're growing, the root hairs are exuding substances that help

ease their way between soil particles and that also help in other

ways. The root exudates ooze between soil particles and help

dissolve phosphorus, aid in the uptake of metals, and feed

microorganisms that make other nutrients more available. As

I mentioned in yesterday's post, the roots are also pumping out

hydrogen ions to trade for cations in the soil; and (less

importantly), roots pump out hydroxyl ions to trade for

negatively-charged nutrients.

Mycorrhizal fungi act

like extension of the root hairs during this nutrient-uptake

process. The tiny fungi are thin enough and long enough to

vastly extend the reach of the plant roots, and they're also good

at bringing in immobile nutrients like phosphorus, copper, and  nickel that would be

tough for plants to suck up on their own. Mychorrhizal fungi

also help out by digesting organic matter to free up nutrients,

making yet more nutrients available for plants.

nickel that would be

tough for plants to suck up on their own. Mychorrhizal fungi

also help out by digesting organic matter to free up nutrients,

making yet more nutrients available for plants.

As if all of the

above methods of getting nutrients aren't complicated enough,

plants also have to deal with weeding out nonessential nutrients

(like heavy metals) that would compete with essential nutrients in

the plant. Some of the exudates released by roots are used

to bind these nonessential nutrients into the soil so they become

unavailable, and mychorrhizae also help out with this binding.

Why should the

gardener care about all this microscopic action? First, it's

handy to understand how important microorganisms are in teaming

with your plants so you'll spend energy keeping the microbes happy

(with lack of tilling, the addition of organic matter, etc.)

But you should also be aware that the work of soil microorganisms

and mychorrhizal fungi slows down drastically during cool weather,

so your plants will have more trouble finding nutrients in early

spring. That might be a good time to pay more attention to

ensuring easily-soluble nutrients are available right up against

seedlings' roots so they can suck up nitrogen without bothering

their sleeping fungal neighbors.

| This

post is part of our Teaming

with Nutrients lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

These milk crates fit nicely

onto the ATV

garbage hauling hitch platform.

Driveway repair got a lot

easier with this modification.

While I was cleaning

up the forest garden, I decided to bite the bullet and rip out the Methley plum

I've been babying for the last four-and-a-half years.

Several people have sung the praises of their European plum trees

in the last year, telling me how much the trees produced with

little care, and I figured I'd obviously just chosen the wrong

species by going for an Asian plum.

Since the two new

European plums I installed last winter --- Seneca

and Imperial Epineuse --- have already grown considerably more than the Methley

ever did, I suspect my gut reaction was right and I should have

been more hard-hearted sooner. In fact, I was able to

literally rip the Methley plum out of the ground bare-handed, a

sure sign that it was lingering, not growing, in our soil.

Now I just need to

wait another three to five years for these better plum varieties

to produce. It's a bit easier to be patient now that other

fruit trees on our homestead are starting to bear...but not much.

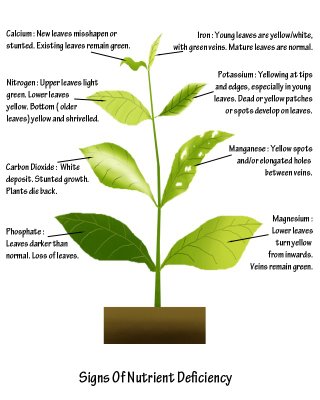

Now that you

understand how

nutrients move through the soil and into

plants, you can

finish the journey with nutrient movement within plants. A

nutrient's mobility once it gets within a plant's cells will

determine where deficiencies show up, as well as how you should

apply fertilizers. For example, Jeff Lowenfels is quick to

point out that foliar feeding is really only appropriate for very

mobile nutrients since immobile nutrients won't be able to move

out of the leaves to where they're needed by the plant.

Now that you

understand how

nutrients move through the soil and into

plants, you can

finish the journey with nutrient movement within plants. A

nutrient's mobility once it gets within a plant's cells will

determine where deficiencies show up, as well as how you should

apply fertilizers. For example, Jeff Lowenfels is quick to

point out that foliar feeding is really only appropriate for very

mobile nutrients since immobile nutrients won't be able to move

out of the leaves to where they're needed by the plant.

I'll start with those

immobile nutrients. Calcium and boron are the least able to

move once they've been consumed by a plant, so any calcium or

boron deficiencies will show up in growing tips. More mobile

nutrients are usually moved from older (less efficient) areas to

these critical growing zones, so any problems in very young leaves

and buds are likely to be due to nutrients the plant really can't

move at all.

Deficiencies of

slightly-more-mobile nutrients (like nickel, molybdenum, sulfur,

copper, iron, manganese, and zinc) will show up in young

leaves. Finally, very mobile nutrients in plants include

nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, magnesium, molybdenum, and

chlorine. Since plants can take mobile nutrients away from

old, inefficient leaves if necessary and move them to young

leaves, deficiencies tend to show up in the oldest leaves first.

Lowenfels also went

into depth about what each nutrient is used for within the plant,

but I didn't feel that information was immediately useful for the

average gardener. So, if you want to learn more, check out Teaming

with Nutrients

and read for yourselves.

| This

post is part of our Teaming

with Nutrients lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The ATV

hitch receiver platform garbage hauler broke on me today.

I knew I was pushing my luck

with that extra bucket.

Maybe a piece of angle iron

would fix it and make it stronger?

"Please explain (again)

your take on soil testing. I've never

had one done and I've gardened for many years. As your

photo

depicts, deficiencies are detectable by plant performance. I

employ crop rotation and try to compensate for particular plant

needs at or before planting and religiously compost."

"Please explain (again)

your take on soil testing. I've never

had one done and I've gardened for many years. As your

photo

depicts, deficiencies are detectable by plant performance. I

employ crop rotation and try to compensate for particular plant

needs at or before planting and religiously compost."

A lot of gardeners

test their soil and never use the information, so I know what you

mean about it not really being necessary. I generally only

send a soil sample off to be tested if I have a reason to.

Specific testing purposes might include (from most to least

important for me):

You

want to plant blueberries or something similar in average soil. If you're going

to need to change the pH of your soil, it's good to have an idea

of how acid or alkaline your soil is at the moment.

You

want to get an idea of how you're improving (or worsening) your

soil over time. I like to look at the percent organic matter and CEC of my soil because these

figures are (hopefully) going up every year. This is

generally just interesting, but can be important in permanent

perennial systems (like pastures) where you never really see the

dirt, so you can't just guess based on on color and texture.

You

plan to remineralize

your soil.

If you believe that ratios of nutrients are just as important as

the absolute amounts (which I'm on the fence about), you'll need

more solid data before you can add minerals to your soil.

You're concerned there may

be a slight deficiency that isn't showing up in your plants. Most soils are

lacking in something (related to the remineralization concept

above). Your plants might just slow down a bit due to a mild

deficiency, but if you're getting most or all of your nutrition

from homegrown food, then a mild deficiency in your plants could

turn into a mild to moderate deficiency in yourself. You

might not care much if your plants are only operating at 80%

efficiency, but I'll bet you care if your kids are.

You're concerned there may

be a slight deficiency that isn't showing up in your plants. Most soils are

lacking in something (related to the remineralization concept

above). Your plants might just slow down a bit due to a mild

deficiency, but if you're getting most or all of your nutrition

from homegrown food, then a mild deficiency in your plants could

turn into a mild to moderate deficiency in yourself. You

might not care much if your plants are only operating at 80%

efficiency, but I'll bet you care if your kids are.

You

think your soil might contain heavy

metals.

A one-time soil test is probably worth doing if you live in a city

or have some other reason to believe your soil might have heavy

metals present above the recommended levels.

You

see some kind of nutrient deficiency in your plants, but can't

figure out what it is. Even though you can tell some problems apart

visually, others look pretty similar. If you're a

large-scale farmer, you might even choose to take a plant tissue

sample in this situation instead of a soil sample.

You

are a chemical farmer. If you're buying any kind of chemical fertilizer,

you should definitely get your soil tested first and see how much

of it you need. On the other hand, if you fertilize with

compost, this isn't so important.

There are probably

other reasons you'd want to test your soil, but those are the

first ones that come to mind. What would you add to the

list?

Over the last few

years, several of you have emailed me to ask if we have an

affiliate program so you can make a little cash by pushing our chicken waterers.

I've had to regretfully say no in because I hadn't jumped through

the technical hoops to make it happen...until now!

We've just started experimenting with selling on Amazon and they

have a built-in affiliate

program.

So now the answer is yes --- you can earn anywhere from $1.72 to

$7.48 each time someone follows your affiliate link and buys one

of our chicken waterers. (You can use Amazon's affiliate

program to plug my ebooks too, but the 4 to 17 cents you'd get per

book sold probably isn't worth much effort.) We've been

using Amazon's affiliate program from the other end for years and

I've been pretty happy with it, especially since they credit sales

to your account if someone clicks your link and ends up buying

something different.

At the moment, we've

only listed our Premade

EZ Miser and

our EZ

Miser kits on

Amazon (plus you

can see my books here). I'll keep you posted if we decide the experiment

is worth expanding. Thanks in advance to anyone who decides

to sign onto the affiliate program and plug our new-and-improved

chicken waterer to your friends!

What happens if you

plant oats

for a cover crop too early (before August 1 in our zone 6

garden)? They go to seed rather than winter-killing in the

vegetative stage.

If you catch the oats

just as they begin to bloom, though, I'm thinking you can scatter

rye seeds over the bed, cut the oats down, and get a second round

of biomass-building in the same season. Time will tell

whether that experiment works.

Why did I plant oats

so early? I've been trying to grow biomass in the back

garden for most of the last year, but it's been so wet (and that

area is always so soggy) that buckwheat wouldn't grow. Oats

and rye are the two cover crops that have proven their ability to

deal with waterlogged clay soil, so I went ahead and planted the

former on July 22. Due to weeds that crept into the poor

stand of buckwheat early in the season, I'll be kill mulching the

whole garden area anyway, so a few oat seeds shouldn't make much

difference.

The FS-90R trimmer is Stihl the best way to cut down an oat cover crop.

"I was wondering if you could clarify your

comment about being

on the fence about ratios vs. absolute quantities. Based on your earlier

mineralization posts, I'm supposing that you're on board with balancing

ratios and on the fence about the absolute quantities. Frankly,

I love testing my garden soils, but I'm an environmental

scientist and a data nerd

"I was wondering if you could clarify your

comment about being

on the fence about ratios vs. absolute quantities. Based on your earlier

mineralization posts, I'm supposing that you're on board with balancing

ratios and on the fence about the absolute quantities. Frankly,

I love testing my garden soils, but I'm an environmental

scientist and a data nerd  I tried Solomon's

remineralization techniques this year but didn't notice

any stellar gains in plant performance. My TCEC is rather low

(5-6) so I'm applying bentonite clay and biochar to help boost

nutrient retention. I'll give it a few more years. To me, the

soil test is a crucial step towards establishing healthy,

balanced soils."

I tried Solomon's

remineralization techniques this year but didn't notice

any stellar gains in plant performance. My TCEC is rather low

(5-6) so I'm applying bentonite clay and biochar to help boost

nutrient retention. I'll give it a few more years. To me, the

soil test is a crucial step towards establishing healthy,

balanced soils."

As you rightly

remember, I also followed Solomon's remineralization lead this

spring, and (although I haven't posted here yet about the

results), I was disappointed. Part of my disappointment

came because the

applied minerals burned the plants I had growing at the time (there's no true fallow

season in our garden), which may be due to the way I added

micronutrients in chemical form. I'm okay with a short-term decline, though, if I

see long-term improvements...but I didn't. In fact, not only