archives for 08/2013

A body of water

that's kept full by rain alone, with no spring or stream flowing

in, is known as a sky pond. Our experimental

pond is going

to be filled by roof-overflow, so it's a sky pond, but one that

needs an inlet pipe.

Since the

pond

is located in the area that used to be a swamp due to said

roof-overflow,

it was a simple matter to pipe the water downhill into the

pond. I dug a shallow trench, fitted a piece of corrugated

plastic pipe around the gutter outlet, and ran the pipe down to

the pond. Mom had picked up a three-foot piece of corrugated

pipe by the side of the road a couple of months ago, which

combined with a ten-foot, purchased length to go right to the edge

of the pond depression. (Thanks for bringing me just what I

needed, Mom!)

As with our greywater

wetland, I

didn't want the inflow of water to erode away my bank, so I lined

the entrance with stones. Then I covered up the pipe, and

sat back to wait for rain. (This seems to be the surefire

way to dry up a soppy summer --- the watched rain cloud never

forms.)

While I bided my time

until the sky pond filled, I kept an eye on the

gleying process. Earth

Ponds reports

that it may take up to two weeks for gleying to take effect (with

total sealing of an earth pond sometimes requiring two years), but

I could tell something was already happening...by smell.

Yep,

the pond developed a quite-distinctive fermentation odor, which

attracted all kinds of winged critters. (To be fair, some

of them might have just been dropping by to drink from the open

water.) The smell wasn't terrible, but I'd hesitate to

reproduce this procedure in a small city lot with nosy neighbors

next door. Good thing our closest neighbor is half a mile

away.

And then the rain

came! It was a gentle shower, dropping no more than half an

inch of water, but the sky pond filled up fast. Eventual

depth at the deepest point was 13.25 inches.

We ran out of rain

before we ran out of water-holding capacity, but I can tell I'm

going to have to hook up the overflow and dig the secondary pond

sooner rather than later. In the meantime, I'm curious to

see whether the pond sinks down to its groundwater level quickly

or whether it holds onto this rain.

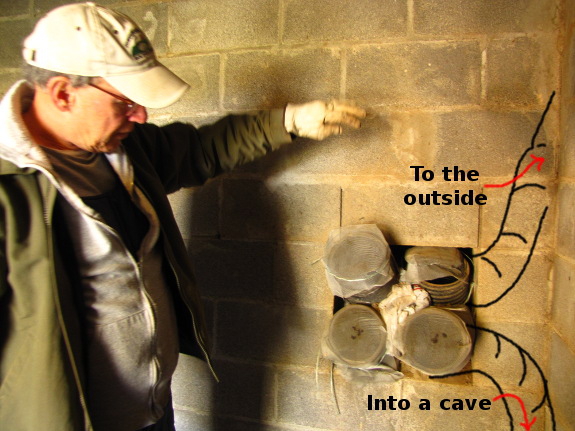

Our neighbor, Frank Hoyt Taylor, took

advantage of the backhoe rented by a friend for grading a

house site to dig a root cellar into his north-facing

hillside. When the excavation was completed, it became

clear that Frank had opened a hole into a cave, so he decided

to gain some extra geothermal cooling by running pipes from

the back of his root cellar into the cave.

Our neighbor, Frank Hoyt Taylor, took

advantage of the backhoe rented by a friend for grading a

house site to dig a root cellar into his north-facing

hillside. When the excavation was completed, it became

clear that Frank had opened a hole into a cave, so he decided

to gain some extra geothermal cooling by running pipes from

the back of his root cellar into the cave.As with Emily's basement cut-off, I'm going to refer you to $10 Root Cellar if you want to read all of Frank's construction tips. That way, I'll have room in this post to sum up his results.

The weakest link in Frank's root cellar is the front wall and door, both of which are open to the elements (although insulated with foamboard). Ice does occasionally form on the inside of the exposed front wall, but temperatures in the main root cellar stay steady for most of the year between 50 and 55 degrees.

The real beauty of

Frank's root cellar is the way he has created a very low-budget

geothermal system by tapping into a naturally-occurring

cave. The cool-air intake involves four drainage-tile pipes,

two of which go directly to the outside and two of which dip into

the cave. Unfortunately, the outside-air pipes were crushed

when the backhoe pushed soil  up against the back of the root cellar, so

Frank feels the root cellar could benefit from more

ventilation. He is considering adding vents at the bottom of

the wooden door, but is happy with the outlet vent at the top of

the cellar.

up against the back of the root cellar, so

Frank feels the root cellar could benefit from more

ventilation. He is considering adding vents at the bottom of

the wooden door, but is happy with the outlet vent at the top of

the cellar.

Frank built the root

cellar with the help of his friend Jim around 2003. The pair

didn't keep track of their labor (which was extensive) and didn't

have to pay for the backhoe since it was already on-site.

Those caveats aside, they estimate they built their cave root

cellar for about $200.

Frank enjoys the way

cave salamanders share space with homegrown potatoes, and he notes

that the structure could double as a tornado shelter if

necessary. When the backhoe-driver came to check up on the

cellar a few months after construction, he opined "That root

cellar is worth a fortune," and Frank agrees.

| This

post is part of our $10

Root Cellar lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

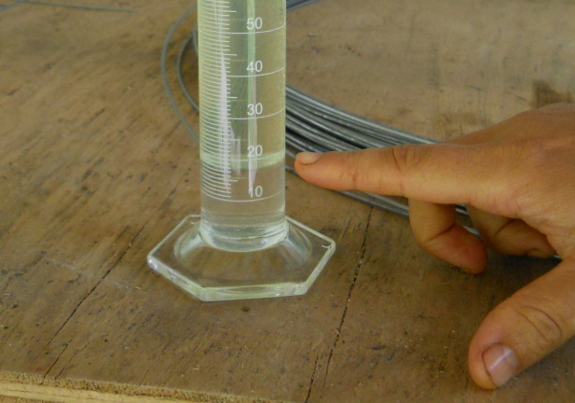

We got this 100

mL graduated cylinder on

Amazon for 12 dollars to do some fuel testing.

Anna has some lab experience

and talked me into the glass model for twice the money.

The first test was done on

some premium fuel I got at the Food City in St Paul.

Food City uses Ethanol like

everybody else and the results showed the advertised 10%, but that was

just to get us accustomed to the procedure. We plan to do the next test

on some so called "Ethanol Free" fuel that a few stations around here

claim to sell.

What do you do if you have a dwarf apple tree

that comes down with fire

blight, you're forced to prune it radically, then it

responds by sending up masses of water sprouts? One website

recommended tying the water sprouts into loops to make the tree

fruit next year instead of zooming further upright.

What do you do if you have a dwarf apple tree

that comes down with fire

blight, you're forced to prune it radically, then it

responds by sending up masses of water sprouts? One website

recommended tying the water sprouts into loops to make the tree

fruit next year instead of zooming further upright.

This particular dwarf

is the oldest perennial we have on the farm, but has yet to give

me a single flower. It's been my learning tree in a lot of

ways, and has the growing pains to prove it. I started the

tree in the mule garden, transplanted it out when we moved the

mules in, then didn't realize that dwarf trees need

a lot of TLC if you want them to bear.

So these loops are my

last-ditch effort to save a very troubled tree who should have

been producing years ago. The loops are certainly

interesting, whether they work or not!

Nita uses a

mechanical chopper to cut up the five pounds of mixed roots

she provides for her dairy cow each winter day. She

notes that the chopper processes the day's roots in one

minute, versus five minutes with a knife. Alternative

methods for processing roots for livestock include cooking

(essential when feeding potatoes to non-ruminants like pigs

and chickens), grating, or feeding whole and raw.

Nita uses a

mechanical chopper to cut up the five pounds of mixed roots

she provides for her dairy cow each winter day. She

notes that the chopper processes the day's roots in one

minute, versus five minutes with a knife. Alternative

methods for processing roots for livestock include cooking

(essential when feeding potatoes to non-ruminants like pigs

and chickens), grating, or feeding whole and raw."While the roots won't replace all the grain for your stock, they can play a bigger part of their winter diet, giving variety and giving you more control in what you are feeding your animals," Nita concluded. "Growing and harvesting roots has made us feel closer to our goal of self-reliance. And we find as we eat more of these types of in-season vegetables ourselves, we rely less on labor- and energy-intensive food-preservation methods. While I'm not giving up my canning and freezing, I find that I'm storing less food that way, and actually providing more variety in our meals."

$10 Root Cellar is free today on Amazon, so download your copy now! If you can't figure out the apps allowing you to read kindle ebooks on your computer or other device, you can also email me today for a free pdf copy. Thanks for reading!

| This

post is part of our $10

Root Cellar lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

It takes us about 40 minutes

to clean out the sediment in our gray water tank.

Anna does most of the dirty

work because she's the most petite between us.

I think it's been 5 years

since we last did this chore. There might be some fertile elements in

that sediment, but we didn't think to save it till it was all splashed

out on the ground.

Even though I had steeled myself for the

tomato blight to hit early and hard in this wet summer, it still

hurt when the fungi took over our planting this week. We've

frozen a grand total of three pints of tomato-based soup so far,

and it's looking like this major component of our winter diet will

be scanty in 2013. (I still hope to put away a few gallons

of soup from the tomatoes ripening now, and the ones I'll end up

ripening inside once the blight beats my radical

pruning and

takes the vines, but it'll be much less than usual.)

Even though I had steeled myself for the

tomato blight to hit early and hard in this wet summer, it still

hurt when the fungi took over our planting this week. We've

frozen a grand total of three pints of tomato-based soup so far,

and it's looking like this major component of our winter diet will

be scanty in 2013. (I still hope to put away a few gallons

of soup from the tomatoes ripening now, and the ones I'll end up

ripening inside once the blight beats my radical

pruning and

takes the vines, but it'll be much less than usual.)

On the positive side,

we don't need nearly as much frozen food to take us through the

winter any more. Between our $10

root cellar, quick

hoops, and the discovery of brussels

sprouts, we fill at least half of our winter vegetable needs

with fresh, living food. Plus, gallons of fruit leather,

sauces, and jams should sweeten my winter disposition even without

the taste of summer tomatoes.

Still, it's worth

taking a minute to sum up factors I could change to slow the

spread of blight in later years. Even though weather is the

biggest reason our tomatoes are failing, I made a major blunder in

selecting their location this year, placing nearly half of our

plants in the gully. During a normal year, the gully would

have provided a sunny spot that was subirrigated,

allowing me to grow tomatoes without risking blight during

watering. But during a wet year, the gully turned out to be

a reservoir of infection. The first signs of blight showed

up there, and none of the plants in the gully did well. In

fact, our copper

experiment was

completely inconclusive because the primary factor that determined

blight damage this year has been proximity to those disease

carriers in the gully.

You can get an idea

for the difference between gully tomatoes and non-gully tomatoes

in the photo above. The plants in the background are in the

lowest part of the gully and have basically been pruned down to

nothing because of major blight damage. In contrast, the

foreground plants are much taller and have quite a few healthy

leaves left.

I could probably turn the gully into an okay tomato spot by

raising the beds up about two feet off the ground, but chances are

I'll just come up with another location for tomatoes in 2016,

after rotating our tomato plot through the back garden and the

forest garden.

In the meantime, I'm

drowning my sorrows in other parts of the summer bounty.

Even a few tomatoes are delicious when fried and topped with swiss

cheese, parmesan, salt, and pepper. An influx of pullet eggs

and cucumbers reminds me that tomatoes aren't the be-all and

end-all of gardening life, even if they sometimes feel that way.

We've been having starting

issues with the ATV and I thought cleaning the muddy battery terminals

might fix the problem.

What I need to remember the

next time is to make sure not to lose the small nut that just sits on

the battery once you remove the screw that holds the wire to the

battery.

I heard it bounce off the

fender where it must have fallen into the grass, which means carrying

in the groceries the old fashioned way until I can find a replacement

nut.

This time of year

always feels melancholy to me, blight or no blight. We're

halfway through our frost-free period, and signs of autumn slowly

build. This year, the autumn feeling is coming faster, with

a low of 52 last week sending me hunting for a long-sleeved

shirt. Luckily, I have a sure cure for end-of-summer

melancholy --- pondering!

Even though I'm

supposed to be letting

the jewelweed ferment and gley my pond for at least two

weeks before adding anything that could boost oxygen content of

the water, I couldn't resist tossing in a gallon of pond inoculant

to get things moving. I aimed for transporting a few

clusters of parrots feather and some duckweed out of my tiny pond,

and ended up bringing along some water beetles and water striders

for the ride. Hopefully I got lots of even smaller critters,

too.

I couldn't resist

breaking off a runner from my lotus while I was at it. The

runner had multiple rooted points, and I pushed each into the mud

at the bottom of my sky pond with a long pole.

Something about these

various inoculants triggered the local dragonfly population, and

nearly immediately, half a dozen moved in. The most common

species (I'm thinking a Common Whitetail) was extremely

territorial, with up to five individuals chasing each other so

busily that no one got to spend much time at the pond. But

two smaller species slipped past the Whitetails' radar and hung

out on the lotus pads.

In the meantime, the

pond continues to be a bubbling cauldron of life, quite

literally. Pockets of gas continue to drift up from the fermenting

jewelweed, leaving an oily skim on the water surface. Now I

know why I sometimes see these oil-slicks in wild locations where

I can't imagine human impact has dropped anything in the water!

(And is it possible this oiliness is also why fermenting organic

matter seals a pond?)

Another odd

observation pertains to color. After the rain filled my sky

pond up, the contents suddenly turned reddish, and even though it

seems awfully coincidental that the roof feeding the pond is

glazed red, I can't imagine that so much pigment could be flaking

off a year after application. Ideas?

Of course, I know

you're probably far less interested in all of these natural

observations, and more interested in whether the sky pond is doing

its job. On Friday, as Kayla and I peered at my little pond,

she mentioned that she was able to walk across the ground above it

for the first time ever --- the swamp is drying up! I'd been

a bit afraid the soggy ground would just move to the downstream

end of the pond, but that doesn't seem to be the case either.

On the other hand, I suspect water levels in my little earth pond

are going to vacillate with the seasons. After I

measured the water depth at 13.25 inches Wednesday, we got

more rain in the afternoon that raised the pond water up another

couple of inches. And, since then, the pond level has been

slowly dropping, reaching 13.5 inches by Saturday morning.

I'll keep you posted on water levels (and far more than you

probably want to know about other aspects of the pond) as my

experiment progresses.

It turns out that those three

tip overs caused some wheel damage on the Bucket Hauler lawn trailer.

These wheels don't have

bearings, but some sort of holder broke away.

Two weeks ago, we got a

call from the sheriff's office. "There's an officer who

needs to see you. He's waiting at the mail box," the

dispatcher said.

Two weeks ago, we got a

call from the sheriff's office. "There's an officer who

needs to see you. He's waiting at the mail box," the

dispatcher said.

"Can you tell us what

it's about?" Mark asked, but the dispatcher had no answer.

So he rushed out on the ATV while I bit my figurative fingernails

and tried to decide if someone was dead or if I'd somehow broken a

law I didn't know about. It turned out, though, that I was

merely being summoned to jury duty.

I should have guessed why the deputy

came calling. Our county court system had sent out a

questionnaire a few weeks earlier, asking if there was any reason

I wasn't eligible for jury duty. I probably could have

gotten out of it since one of the eligible excuses was being the

owner of a business with no employees (or something similar), but

I figured it was my civic duty to serve. Plus, I've never

been called for jury duty before and I always feel I owe it to

myself to try new things at least once, to expand my horizons.

I should have guessed why the deputy

came calling. Our county court system had sent out a

questionnaire a few weeks earlier, asking if there was any reason

I wasn't eligible for jury duty. I probably could have

gotten out of it since one of the eligible excuses was being the

owner of a business with no employees (or something similar), but

I figured it was my civic duty to serve. Plus, I've never

been called for jury duty before and I always feel I owe it to

myself to try new things at least once, to expand my horizons.

As the date got closer,

though, I started regretting my high-minded thoughts. Our

farm and business run like a well-oiled machine most of the time,

but that all breaks down if one of the two wheels is

missing. And the jury-duty literature refused to tell me how

long I'd be serving --- maybe just one day, but maybe up to the

entire four-month court session if there's some big trial I don't

know about.

As the date got closer,

though, I started regretting my high-minded thoughts. Our

farm and business run like a well-oiled machine most of the time,

but that all breaks down if one of the two wheels is

missing. And the jury-duty literature refused to tell me how

long I'd be serving --- maybe just one day, but maybe up to the

entire four-month court session if there's some big trial I don't

know about.

So I scurried around

to get the farm ready to live without me. Like most couples

who homestead together, Mark and I divide up our responsibilities,

and he can't really do my job any more than I can do his.

Things like checking the peach tree for brown

rot, saving

tomato

seeds, cooking up soup, and feeding the bees take longer to

explain than they do to perform, and I did my best to get caught

up for the next day or two on Sunday.

tomato

seeds, cooking up soup, and feeding the bees take longer to

explain than they do to perform, and I did my best to get caught

up for the next day or two on Sunday.

Which is all a long

way of explaining why, by the time you read this, I'll be winding

down a foggy, country road to the courthouse (and why your

comments won't come out of moderation until I get home). I felt

like a real weekend

homesteader trying to get ready for a 9 to 5 job that might

last all week, and I have to admit that I vastly prefer my

full-time homesteading status.

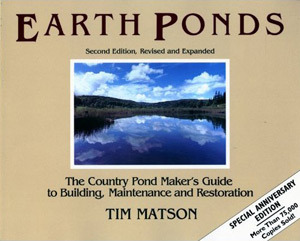

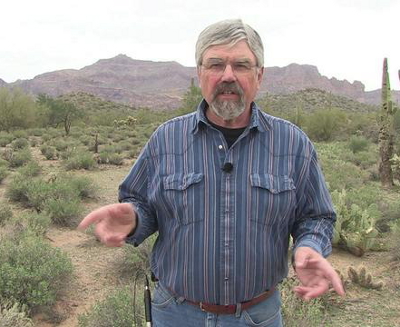

As you can probably tell from all of my pond

experimentation last week, Tim Matson's Earth

Ponds did a

great job getting me excited about playing in the mud. I

read the second edition because a perusal of the table of contents

suggested it was pretty much identical to the newer edition, and

at the time Amazon had a used copy available for only $4.

(If you've looked at the third edition and see updates, I hope

you'll add your two cents' worth as comments on this week's

lunchtime series!)

As you can probably tell from all of my pond

experimentation last week, Tim Matson's Earth

Ponds did a

great job getting me excited about playing in the mud. I

read the second edition because a perusal of the table of contents

suggested it was pretty much identical to the newer edition, and

at the time Amazon had a used copy available for only $4.

(If you've looked at the third edition and see updates, I hope

you'll add your two cents' worth as comments on this week's

lunchtime series!)

The first third of

Matson's book is a chatty story of how he built his own pond

around 1980 in Vermont. He cleared trees in a wetland, then

hired a bulldozer to do the excavation. For $850, the

bulldozer operator dug out a large area (about 93 feet by 75 feet)

to a depth of 8  feet. Water seeped

in through the earth as the pond was was being excavated, then

overflow created its own spillway once rains arrived, with Matson

coming along behind to rock the water's path and prevent erosion.

feet. Water seeped

in through the earth as the pond was was being excavated, then

overflow created its own spillway once rains arrived, with Matson

coming along behind to rock the water's path and prevent erosion.

The rest of this

week's lunchtime series will hit the highlights of pond

construction according to Matson, but I wanted to provide a few

caveats up front. Earth Ponds is focused on creating

an earth-bottomed swimming hole that will keep fish happy and

provide a bit of water for the garden, so it won't be relevant to

everyone. If you want to make a little backyard pond like

ours, you'll have to guess and experiment, and if you want to

create a more vibrant ecosystem, you'll have to overlook all of

Matson's attempts to eradicate "weeds" (meaning any aquatic

vegetation) from his pond. Still, I've yet to find a better

book about earth-bottomed ponds, so Matson's text is at the top of

my list.

| This

post is part of our Earth

Ponds lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I was able to use a wheel

barrow wheel to get the Bucket Hauler going today.

The driveway still has deep

and uneven ruts, which has me re-thinking the trailer concept.

Maybe there's a way to carry

6 buckets on the ATV without the trailer trouble?

"Ok, so an (Amazon Associate paid link to

a) graduate cylinder, and what I assume is fuel. But no details

on what test you're doing, how you're doing it, or how to

interpret the results. Let me rush right out to click your link,

buy the cylinder, and pour some gas into it. Not that I'd know

what the hell anything meant, but hey, you'd make a dime,

right?"

"Ok, so an (Amazon Associate paid link to

a) graduate cylinder, and what I assume is fuel. But no details

on what test you're doing, how you're doing it, or how to

interpret the results. Let me rush right out to click your link,

buy the cylinder, and pour some gas into it. Not that I'd know

what the hell anything meant, but hey, you'd make a dime,

right?"

While this comment is

a remarkably trollish response to a blog post meant to show you

tidbits of our personal life, I had been meaning to give our

readers more details on how simple it is to perform a test for

ethanol content of gasoline. All you need is something that

easily measures volume --- a 100 mL or larger graduated cylinder

takes nearly all the math out of your hands, but you could just as

easily use a ruler in a straight-sided glass cup or jar.

The idea is that when

you mix water with gas, any ethanol in the gas comes out of

solution and joins the water instead. So all you have to do

is know how much water you initially added to the gas, subtract

that out of the clear layer at the bottom of your graduated

cylinder at the end of the experiment, and the rest of the clear

substance is ethanol.

When starting your

ethanol test, the first step is to take your gas sample

carefully. As a

far-more-constructive commenter mentioned, you should run at least a gallon

of gas into your car before taking a sample from any pump that

uses a shared hose. Then pump a sample into a container and

bring the gas home to experiment.

In the meantime, you

should take a minute to prep your graduated cylinder (assuming

you're like us and only bought a 100 mL one instead of a cylinder

with a larger capacity). Later in the experiment, you'll

need to know where the 110 mL line is, which is easy to guestimate

by measuring the distance between the 90 and 100 mL lines, then

measuring that same distance above the 100 mL line. To keep

things simple, use a piece of tape to wrap around the graduated

cylinder at the 110 mL line, marking its location.

Now you're ready to

add the gas. I found it much easier to pour some gas into a

small container rather than trying to fill the graduated cylinder

from the gas can. You want to add gas up to the 100 mL line,

and don't forget your chemistry lessons --- read from the bottom

of the meniscus!

Top the gas off with

10 mL of water, meaning that the total liquid level should match

the taped 110 mL line. Then mix the contents.

(Mixing was the

hardest part for me because our graduated cylinder didn't come

with a stopper, and I ended up slopping a bit of liquid out while

plugging the top with my palm. I think a better solution

would have been to use a sandwich baggie pulled over the top of

the graduated cylinder, or to invest in some parafilm.

Either way, thorough mixing is imperative.)

After mixing, the

clear ethanol and water will settle to the bottom, while the

colored gas will sit above it. You can easily measure how

much water and ethanol is present, then subtract 10 mL from that

to find the percent ethanol in the water. Probably because

of my sloppy mixing, our clear layer came to 17 mL, producing a

reading of 7% ethanol instead of the 10% listed on the pump at the

gas station. (If you didn't use the exact amounts of gas and

water I listed above, you'll have to do a bit more math: ((Clear

layer - Water)/(Gas))x100%.)

As Mark has mentioned

previously, ethanol

in gas can wreak havoc on many of the small engines found on our farm, so

it's useful to know for sure that the ethanol-free gas we've

hunted down really doesn't have any ethanol in it. We'll be

testing gas stations soon and hoping to find one near us that is

really ethanol-free.

The most important

factors to consider when building a pond without a liner are

location and soil quality. You can get an idea for both by

digging test pits in an area where you want a large pond to

go. Each pit should be about eight to ten feet deep and

should be excavated during your driest season. You're

looking for rock ledges (bad), clay (good), and high groundwater

(good).

The most important

factors to consider when building a pond without a liner are

location and soil quality. You can get an idea for both by

digging test pits in an area where you want a large pond to

go. Each pit should be about eight to ten feet deep and

should be excavated during your driest season. You're

looking for rock ledges (bad), clay (good), and high groundwater

(good).

In different parts of

his book, Matson writes that pond

soil should be either 10% to 20% clay,

or at least 20% clay. As far as I can tell, more clay is

almost always better, unless you're building a dam (more on that

in a later post), in which case pure clay won't be as

stable. And, while we're talking about the earth, hitting

rock bottom in your test pit is a sign that you should put your

pond someplace else --- ledges, especially, allow water to flow

right out the bottom of your pond and disappear.

Equally as important

as the soil, you're looking for high groundwater in your test

pits. In a pond without a dam, the level of the groundwater

will tell you the eventual low-water level of your pond, so not

hitting water in your test pits is another sign you should look

for a different pond location. Of course, groundwater moves

slowly, and in

my experiment I

found that it took several hours for my excavation to fill up with

water, so give your test pits a day or two to fill before calling

them failures.

| This

post is part of our Earth

Ponds lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Congratulations to Bernard, Letty, and Wendy,

who won our permaculture

onion giveaway!

Letty

regaled us with information about how she integrates chickens into

her Louisiana homestead, Bernard took advantage of old hay and horse manure on

his newly purchased farm to get the garden off to a good start,

and Wendy has created a bountiful, edible garden that fits into a

suburban front yard (pictured here).

Congratulations to Bernard, Letty, and Wendy,

who won our permaculture

onion giveaway!

Letty

regaled us with information about how she integrates chickens into

her Louisiana homestead, Bernard took advantage of old hay and horse manure on

his newly purchased farm to get the garden off to a good start,

and Wendy has created a bountiful, edible garden that fits into a

suburban front yard (pictured here).

Unfortunately, we

have more onions looking for homes than we had winners.

(Mark tells me the contest was too hard for most people.)

So, I'll make things easier for this second round and stick to the

old standby in the blogging world --- you plug one of our books or our chicken waterer in the social media

world, leave a comment on this post to let me know you entered,

and I'll draw names out of a hat on August 13 and give away Egyptian

onions until

we run out. Hopefully this will give folks a chance if they

missed our lightning giveaway or found the permaculture giveway

too hard. Thanks in advance for entering and spreading the

word about our products so we have time to share our adventures

with you on the blog!

I left you all

hanging about jury

duty because

they left me hanging too. Monday turns out to have been an

orientation day, after which I'm on call for half the work days

over the next three months. The system seems awkward --- I

have to check a website after 5:30 pm the night before each

potential trial date, and then I'll know whether the relevant

people decided to go to trial or not. According to the

judge, most cases end up being decided without a jury, and the

average juror is asked to serve only two days during that

three-month period.

So I'm back at work

on the farm, feeling unbelievably grateful to have such a

wonderful "work" environment! Chattering with Kayla as we

perk up the mule garden feels more like socializing than like

work, but we still get a lot done.

In case you wanted

something homestead-related in today's post, I've got two

disjointed observations to throw at you. The first has to do

with flowers --- have you ever noticed that the old-fashioned

annuals that are so easy to grow from seed (like the touch-me-nots

in the first photo in this post) attract the most

pollinators? The zinnias I half-heartedly tossed out into

the same flower bed are also drawing in butterflies and bees,

while the irises I was so happy about this spring were largely

ignored by insects.

My second observation

has to do with the peaches in the second photo. These are

the white peaches on our oldest tree, the first of which came down

with brown rot over the weekend. Even though the ground

color looks awfully green, I'm guessing this is the right

stage to pick them if I want to ripen white peaches inside.

Has anyone else had experience with the best time to pick white

peaches for indoors ripening?

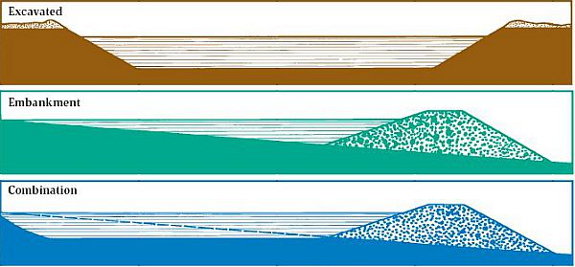

Tim Matson explains

that there are two types of earth

ponds --- the

dug-out pond and the embankment pond. The former is

generally built in a flat area where groundwater lies close to the

surface, while the latter works best in a valley that can be

turned into a pond by building a wall across the valley bottom.

Tim Matson explains

that there are two types of earth

ponds --- the

dug-out pond and the embankment pond. The former is

generally built in a flat area where groundwater lies close to the

surface, while the latter works best in a valley that can be

turned into a pond by building a wall across the valley bottom.

Dug-out ponds are

just what the name suggests --- a hole in the ground. They

can be quite small, and commercial fisheries often use a series of

dugout ponds in series rather than one big pond to make management

easier. In the case of the fisheries Matson mentioned in his

book, ponds are about 15 feet in diameter and 3 to 5 feet deep.

The main disadvantage

of a dug out pond is that the earth needs to go somewhere else ---

mounding it up around the sides just creates a really

funny-looking pond in a hole. If you live in a very wet

area, though, that excavated soil can be a pro rather than a con

--- Matson mentioned one farmer who dug out a pond in a very low

area, then used the soil to bring a nearly-as-low field out of the

marsh and into more productive conditions. We're

doing something similar on a much smaller scale with our pond

experiment.

The embankment method

is often used to create a larger pond since it's more

cost-effective to mound up the excavated earth as a dam, raising

the potential water level and increasing your volume twice as

quickly for each scoop of earth removed. However, embankment

ponds often blow out at the dam if you're not careful, so you'll

want to follow Matson's tips to clear the embankment area down to

the subsoil, then slowly build it up with impervious soil,

compacting after every foot or two. Unlike the walls of a

dugout pond, which can be as steep as 2:1, you should keep your

embankment flatter, with a maximum slope of 3:1.

In both the case of a

dugout pond and an embankment pond, you need to think about how

water comes into and leaves the pond as well. Some dugout

ponds are sky ponds, relying completely on groundwater and rain to

stay full, but most ponds of both types are fed by a spring or

stream. Planning your inlet pipe so water cascades out onto

the pond surface will add oxygen, while burying the pipe keeps

water cooler in the summer and from freezing in the winter.

On the other hand,

you can use an unpiped inflow with a small settling pool just

before you reach the pond, preventing silt from entering the pond

proper.

In both the case of a

dugout pond and an embankment pond, you need to think about how

water comes into and leaves the pond as well. Some dugout

ponds are sky ponds, relying completely on groundwater and rain to

stay full, but most ponds of both types are fed by a spring or

stream. Planning your inlet pipe so water cascades out onto

the pond surface will add oxygen, while burying the pipe keeps

water cooler in the summer and from freezing in the winter.

On the other hand,

you can use an unpiped inflow with a small settling pool just

before you reach the pond, preventing silt from entering the pond

proper.

At the other end of

the pond, Matson is less keen on piping, having seen far too many

ponds leak around the outflow pipe. Instead, he recommends

creating a stone-lined spillway channel, or, if you absolutely

must pipe your outflow, adding an anti-seep collar around the

pipe.

Stay tuned for

tomorrow's post on sealing the earthen pond!

| This

post is part of our Earth

Ponds lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We tested out a new milk

crate ATV bucket holder system today.

Anna said "Do you think a

bucket would fit in one of those old milk crates?"

It was easy to attach the

milk crate to the ATV rack by weaving a few feet of rope through the

holes in the crate and pulling it tight against the rack.

At this time of year,

the garden moves inside and spreads out across all flat

surfaces. Seeds

are fermenting or drying, to be eaten or planted. Tomatoes

from the vines I've deemed too  blighted are ripening on a table, and so are

the first few peaches from our late-fruiting tree.

blighted are ripening on a table, and so are

the first few peaches from our late-fruiting tree.

I can't quite

remember where I did all this work before we had a porch and moved

our summer dining outside. Actually, I've used up half of

the picnic table, too, for curing warty summer squash before we

smash them open and rip out the seeds.

What does your

seed-saving station look like?

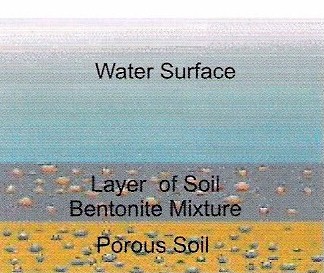

Earth ponds are never 100%

water-tight, but it's important to keep the seepage to a minimum

so water levels stay high. As I mentioned in a previous

post, compaction

and gleying are

two traditional methods of creating a (mostly) water-tight seal,

but you can't expect either one to be effective all at once.

A good pond will seep less and less over the course of the first

two years as sediment fills leaks and as the weight of the water

continues to compact the soil.

Earth ponds are never 100%

water-tight, but it's important to keep the seepage to a minimum

so water levels stay high. As I mentioned in a previous

post, compaction

and gleying are

two traditional methods of creating a (mostly) water-tight seal,

but you can't expect either one to be effective all at once.

A good pond will seep less and less over the course of the first

two years as sediment fills leaks and as the weight of the water

continues to compact the soil.

But what if your

pond's still leaking in year three? Pond remediation often

includes adding native clay or bentonite (the latter of which is a

specific kind of clay) to the soil. To do so, you have to

drain any remaining water out of the pond, mix the additive into

the soil surface, then compact the pond to re-create the

seal. Bentonite generally comes as a powder, so you only

need one pound per square foot of surface, but with clay you'll

need to add a foot or two to create a good seal.

But what if your

pond's still leaking in year three? Pond remediation often

includes adding native clay or bentonite (the latter of which is a

specific kind of clay) to the soil. To do so, you have to

drain any remaining water out of the pond, mix the additive into

the soil surface, then compact the pond to re-create the

seal. Bentonite generally comes as a powder, so you only

need one pound per square foot of surface, but with clay you'll

need to add a foot or two to create a good seal.

If even this fails,

chances are you've picked

a poor site for your pond. In that case, it's best to find a better

location and try again.

| This

post is part of our Earth

Ponds lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Anna's ATV

milk crate bucket holder

idea turns out to be a great solution!

We added two more crates to

bring the carrying capacity to six 5 gallon buckets.

It now takes 5 trips to empty

the truck compared to 3 with the trailer.

I've been giving sugar water to our two new

colonies every time the feeders empty, but at the beginning of

this week I decided they needed to start slowing down their

brood-raising for winter, so I let the feeders run dry. I

expected that would mean bee activity outside the hive would slow

down, but instead, I noticed bearding

again on our Warre package hive. I couldn't even get

the camera close without a bee suit, so I haven't looked inside

yet, but I'll probably add another box today just in case.

I've been giving sugar water to our two new

colonies every time the feeders empty, but at the beginning of

this week I decided they needed to start slowing down their

brood-raising for winter, so I let the feeders run dry. I

expected that would mean bee activity outside the hive would slow

down, but instead, I noticed bearding

again on our Warre package hive. I couldn't even get

the camera close without a bee suit, so I haven't looked inside

yet, but I'll probably add another box today just in case.

Seeing the bearding

on one hive prompted me to check on our other colonies, and all

were buzzing with life! My beekeeping mentor (aka my

movie-star neighbor) told me Wednesday that his hive was hopping,

which he attributed to the jewelweed flowers opening up.

Just within fifteen feet of one hive, though, I saw jewelweed,

woodland sunflower, and virgin's bower all coming into bloom, so I

suspect this nectar flow is due to a mixture of fall

flowers. Maybe the fall flow will be strong enough that

we'll get to harvest a bit of honey from our two-year-old hive

despite their

swarm this spring.

Tim Matson didn't

provide much information on pond biology because he was trying to

keep the plants in his pond to a minimum. However, he did

include a list of flora in his section on wildlife ponds,

mentioning that fish, ducks, and geese will all eat Sago pondweed,

wild celery, coontail, elodea, muskgrass (gives fish an off

flavor), arrowhead, wild Japanese millet, wild rice (needs flowing

water), lotus, waterlilies, iris, pickerel plant, burr reed,

cattails, smartweed, and bulrush.

Tim Matson didn't

provide much information on pond biology because he was trying to

keep the plants in his pond to a minimum. However, he did

include a list of flora in his section on wildlife ponds,

mentioning that fish, ducks, and geese will all eat Sago pondweed,

wild celery, coontail, elodea, muskgrass (gives fish an off

flavor), arrowhead, wild Japanese millet, wild rice (needs flowing

water), lotus, waterlilies, iris, pickerel plant, burr reed,

cattails, smartweed, and bulrush.

Fish were more

Matson's cup of tea, specifically trout. As with the paucity

of information on plant life, Matson didn't try to cover the needs

of different kinds of fish, but he did warn new pond owners away

from dropping fish into their water right away. It often

takes about a year for water quality to stabilize in an earthen

pond, with initially low pH and low-dissolved-oxygen levels slowly

being mitigated by an influx of organic matter and by the growth

of microorganisms. Short of buying water-testing equipment,

the best way to know if your pond is ready for fish is to drop a

few cheap ones in and see if they survive.

I hope you've enjoyed

these tidbits from Earth

Ponds, even

though the information is more suited to half-acre-and-larger

ponds than to little backyard water gardens. As you can

tell, I've been doing

experiments of my own about how to make an earth pond that

better fits the backyard, and I'll continue to keep you

posted about the results.

| This

post is part of our Earth

Ponds lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We filled the fourth Cadilac

worm bin with horse

manure today.

I think having full worm bins

is a bit of a warmer, fuzzier feeling than a full wood shed.

Firewood is something we

could buy if push came to shove, but a horse manure delivery service is

a homesteading fantasy from a hundred years ago.

I had three surprises

Thursday --- one unpleasant, one pleasant, and one

interesting. Mark always takes his surprises from worst to

best, so I'll write this post that way too.

I had three surprises

Thursday --- one unpleasant, one pleasant, and one

interesting. Mark always takes his surprises from worst to

best, so I'll write this post that way too.

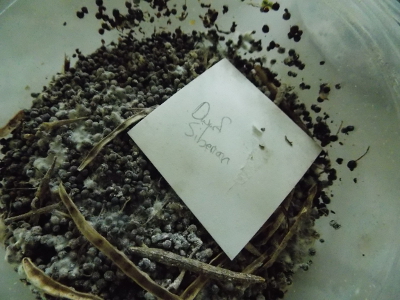

The unpleasant

surprise came when I pulled out the kale seeds I'd saved this

spring in preparation for planting our fall crop. The seeds

had rotted in the container! I'm usually pretty good about

harvesting seeds when they're as dry as possible, then letting

them sit out for another week or two in an open container to

finish dehydrating (especially if I'm going to seal them in

plastic instead of paper), but I clearly missed a step somewhere

along the way. Luckily, I have some 2012 seeds still kicking

around for one kale variety, and have time to order more of the

second variety since the whole month of August works for kale

planting around here. (I also snuck in a packet of Laciniato

kale into my seed order to try yet another variety.)

The interesting surprise came in the tomato

patch, where one of my yellow romas turned into an orangish roma

instead. Last year, a totally new tomato variety popped up

in my garden (shown to the right), and I assumed the seed had come

in with the manure. But now that I've seen this happen two

years in a row, I think I'm seeing the unusual-but-possible

effects of tomato hybridization. (Tomatoes are usually

self-pollinating, so you can grow several varieties in the same

patch even when saving seeds, but nature doesn't always play by

the rules.) I'm guessing this year's hybrid is probably a

Yellow Roma mixed with a Japanese

Black Trifele,

and I like the way I get the indeterminate, vigorous nature of the

Yellow Roma along with a heavier fruit set and a reddish

fruit. Last year's little red roma bred true, so I'll save

some seeds of the new hybrid too and will start pondering names

for my newly created tomato varieties.

The interesting surprise came in the tomato

patch, where one of my yellow romas turned into an orangish roma

instead. Last year, a totally new tomato variety popped up

in my garden (shown to the right), and I assumed the seed had come

in with the manure. But now that I've seen this happen two

years in a row, I think I'm seeing the unusual-but-possible

effects of tomato hybridization. (Tomatoes are usually

self-pollinating, so you can grow several varieties in the same

patch even when saving seeds, but nature doesn't always play by

the rules.) I'm guessing this year's hybrid is probably a

Yellow Roma mixed with a Japanese

Black Trifele,

and I like the way I get the indeterminate, vigorous nature of the

Yellow Roma along with a heavier fruit set and a reddish

fruit. Last year's little red roma bred true, so I'll save

some seeds of the new hybrid too and will start pondering names

for my newly created tomato varieties.

The final surprise was a

spring broccoli plant that produced a delicious head in

August! Usually, I rip out any spring broccoli that doesn't

mature in a timely manner since summer's heat prompts the plants

to produce measly heads that aren't worth the garden space.

But this broccoli was tucked away in the forest garden, so I

forgot about it. And the cool wet summer resulted in

beautiful head after all! I guess I should have been more

serious about planting broccoli during this wet summer to take the

place of our ailing tomatoes. I did have an extra dozen

brussels sprouts sets, though, which are now getting their feet

under them between the soon-to-be-gone tomatoes:

The final surprise was a

spring broccoli plant that produced a delicious head in

August! Usually, I rip out any spring broccoli that doesn't

mature in a timely manner since summer's heat prompts the plants

to produce measly heads that aren't worth the garden space.

But this broccoli was tucked away in the forest garden, so I

forgot about it. And the cool wet summer resulted in

beautiful head after all! I guess I should have been more

serious about planting broccoli during this wet summer to take the

place of our ailing tomatoes. I did have an extra dozen

brussels sprouts sets, though, which are now getting their feet

under them between the soon-to-be-gone tomatoes:

Any surprises lately

in your garden?

Before I became a homesteader

I would usually observe the end of Summer being when young people would

go back to school....often thinking "better you

than me!" with great

relief that I have already completed my State

required dose of compulsory education.

These days Anna and I have

our very own end of Summer ritual....the hatching of the year's last

batch of incubated

chicks.

They started showing up

yesterday...and now we have an excited baker's dozen.

I slipped out just

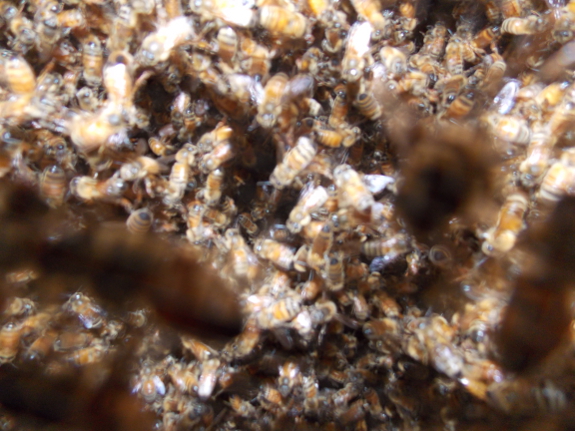

before dark to take a photograph under our three-box Warre hive to

see if bearding really meant they were

running out of room inside. It's a good thing the bees were

slowing down for the night, because even the underside of the

screened bottom was coated with bees! The out-of-focus photo

below is the best shot I could get inside, but it's pretty easy to

see that the bees needed more room.

Unfortunately, the

next day it rained. A two-hour break in showers was enough

to get the bees out and moving, so I figured I'd be able to nadir

the hive, even though I knew they'd be unruly. I suited up

very carefully because overcast days are the worst time to open up

a hive, and

the bees were definitely displeased with my actions. Good

thing I've got a few years of beekeeping under my belt now and

know to just take a step back, take a few deep breaths, and let

those angry ladies batter themselves vainly against my veil.

I didn't want to bother the colony longer

than necessary since the bees were so upset, so I just plopped the

fourth box underneath and went to peer at the entrance.

Warre hives have smaller openings than Langstroth hives do, and

this is one day the bees could probably have used more room.

There was a traffic jam of bees coming and going, but I was able

to see a lot of brilliant yellow-orange pollen on several of the

incoming bees. Sounds like the colony is still beefing

itself up by raising more brood --- here's hoping they don't eat

through their winter stores too quickly with so many new mouths to

feed.

I didn't want to bother the colony longer

than necessary since the bees were so upset, so I just plopped the

fourth box underneath and went to peer at the entrance.

Warre hives have smaller openings than Langstroth hives do, and

this is one day the bees could probably have used more room.

There was a traffic jam of bees coming and going, but I was able

to see a lot of brilliant yellow-orange pollen on several of the

incoming bees. Sounds like the colony is still beefing

itself up by raising more brood --- here's hoping they don't eat

through their winter stores too quickly with so many new mouths to

feed.

I haven't written much about my other two hives in a while, but

that's because they aren't as busy. The workers are all out

harvesting the current nectar-and-pollen source, but I don't see

any signs that either hive might be running out of room. If

anything, I might end up taking the fourth box out from under our

two-year-old hive and giving it to our package hive if both

colonies keep acting the same way in the near future --- the

package hive has been filling boxes like crazy, while the

two-year-old hive seems quite content to use two-and-a-bit boxes

for the foreseeable future.

Once upon a time Anna and I

tried selling Cattails on E-Bay to pay some bills.

Now we just admire their

beauty and water absorbing power near our wetland

pond.

For the first time

this year, I'm realizing that it's possible to reach the point

where I've made enough fruit

leather and freezer

jam, have gorged myself on fresh, and still have an excess

of summer fruits. I plan to can whole peaches once the

fruits from our late tree are entirely ripe, but the

half-ripe-but-brown-rot-affected peaches also need a home, and

those seemed like a good candidate for jam.

We don't eat much

jam, partly because we've eliminated bread from our diet, but more

because jam is just so sweet that it seems like a dessert, even

when mixed with yogurt. Despite the name, the "low-sugar",

cooked jam recipes inside the SureJell box call for 3 cups of

sugar for every 4.5 cups of peaches, and I wanted to go much lower

than that. So I started reading up on long-boil jams, where

the combination of evaporating off water and candying the sugar

produces a gel without the sugar-pectin reaction.

For my first experiment, I

used 1 cup of sugar, a box of low-sugar pectin, 1.5 cups of

peaches, and 3 cups of blackberries. The result was a very

well-set jam (although far too seedy). I didn't have any

canning lids on hand, though, so I just stuffed this first

experiment in the freezer.

For my first experiment, I

used 1 cup of sugar, a box of low-sugar pectin, 1.5 cups of

peaches, and 3 cups of blackberries. The result was a very

well-set jam (although far too seedy). I didn't have any

canning lids on hand, though, so I just stuffed this first

experiment in the freezer.

After sending Mark to

town for canning lids and accumulating another four or five cups

or so of problematic, unripe peaches, I decided to try again, this

time without pectin. I cut up the peaches into big chunks

(instead of sending them through the food processor the way I did

last time), added about half a cup of blackberries and 1 cup of

sugar, and tossed in half a cup of the seedy blackberry jam from

round 1. (So I guess this experiment did involve a little

bit of store-bought pectin.)

As the jam was cooking, I

started looking up instructions for canning jam. The

SureJell recipes simply call for sterilizing the jars, pouring the

hot jam in, then putting on the lids, with no further

processing. While that might have been acceptable even

without the pectin, I wasn't sure enough to give it a try.

As the jam was cooking, I

started looking up instructions for canning jam. The

SureJell recipes simply call for sterilizing the jars, pouring the

hot jam in, then putting on the lids, with no further

processing. While that might have been acceptable even

without the pectin, I wasn't sure enough to give it a try.

Meanwhile, extension service websites tell me that sugar isn't

necessary for preventing spoilage --- that its purpose in jam is

merely to maintain the color and to produce the gelatinous

consistency. But they also recommend processing any jam for

5 minutes in a hot water bath if you live below 1,000 feet in

elevation, and for 10 minutes if you live between 1,000 and 6,000

feet.

Despite this data, I was

still stumped because the aforementioned extension service

websites assumed I'd be adding pectin of some sort, not using the

older, boil-down method of jamming. To be entirely safe, I

figured I could use the processing guidelines for canning plain

fruit, but I couldn't find any data on how many minutes to process

peaches and blackberries in cup-size jars. I did, however,

read that prolonged boiling weakens pectin, so I opted to stick to

the extension service's 10-minute guidelines after all.

Despite this data, I was

still stumped because the aforementioned extension service

websites assumed I'd be adding pectin of some sort, not using the

older, boil-down method of jamming. To be entirely safe, I

figured I could use the processing guidelines for canning plain

fruit, but I couldn't find any data on how many minutes to process

peaches and blackberries in cup-size jars. I did, however,

read that prolonged boiling weakens pectin, so I opted to stick to

the extension service's 10-minute guidelines after all.

The result is six

little jars of light-maroon jam, which seems to have set up pretty

well as it cooled. I guess I won't know for sure if my

experiment was a success until I wait a few weeks and open up a

jar to see what's going on inside.

I'm very new to

recipe-less jam-making, so I'd love to hear about your

experiences. Any other favorite ways to process small

amounts of excess fruit, or (looking ahead), lots and lots of

peaches?

We retired some chickens

today, and for years we've been using this black bucket as an easy, DIY

substitute to the traditional Kill

Cone that has worked for thousands of backyard chicken people. My

Mom made the hole so she could grow an upside down tomato plant back

when that was all the rage in modern gardening techniques. She went

back to putting her tomatoes in the ground and offered us the bucket one

day.

That bucket collected dust in

the barn for a year or two until we started processing our own poultry.

We mounted a shelf bracket so it could hang at an easy height and it

worked well at keeping the bird still while its head poked out through

the hole.

Trial and error showed us the

hole was too big. The more aggressive chickens could sometimes get one

of their claws through the hole, complicating the procedure.

Today I finally modified an

old bucket with a smaller hole which seems to be a huge improvement. A

2 inch hole saw makes the opening just big enough for a chicken's head

without the extra room version 1.0 offered.

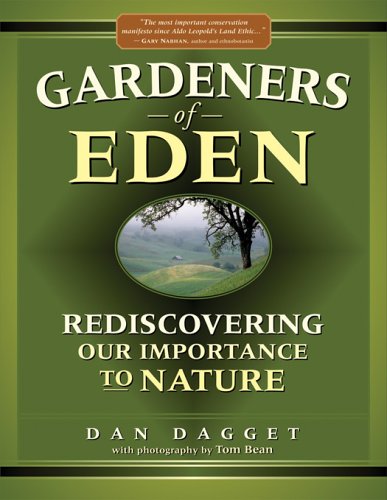

Mark and I were recently

included in A

Way of Life Less Common, by Christine Dixon. The book consists of

interviews of six couples and one mother who are homesteading,

living off the grid, and/or running a home-based business. I

particularly enjoyed hearing from several homesteaders in Canada,

where the terminology is a bit different, but the ideas are very

similar to those Mark and I base our lives on.

Mark and I were recently

included in A

Way of Life Less Common, by Christine Dixon. The book consists of

interviews of six couples and one mother who are homesteading,

living off the grid, and/or running a home-based business. I

particularly enjoyed hearing from several homesteaders in Canada,

where the terminology is a bit different, but the ideas are very

similar to those Mark and I base our lives on.

A Way of Life Less Common

is a bit like the profiles in Trailersteading

--- an interesting overview of why people chose similar lifestyles

for different reasons. One homesteader was drawn to

alternative building practices, another to wilderness ("bush")

skills, and yet another to providing a better environment for her

young son. You'll see tidbits of their daily lives (I

thought we had invented the concept of going-to-town clothes vs.

work clothes!), and will read about their biggest trials and

successes.

Mostly, though, I

enjoyed rereading my own chapter because I'd forgotten how Mark

interspersed his observations with mine. Like a love letter

I had forgotten existed! If you want to learn about our

early years on the farm (and about other homesteading bloggers),

you can get $2 off the cover price by going to Createspace and entering this code:

D9CP2GX3. Enjoy!

Today the new

chicks moved out of the

plastic tub and into their outdoor

brooder.

They seem to like scratching

around in a few inches of sawdust.

When it comes to

fruit management, Mom talks about separating the sheep from the

goats. The sheep are the good fruit that will last for a

while as-is, while the goats are damaged and need to be processed

ASAP.

I accidentally

started sorting the sheep from the goats on our kitchen peach last

week when I

picked the more-damaged-looking peaches to bring inside and ripen. In retrospect,

those peaches were a little too unripe to reach perfection off the

tree, but I suspect my premature picking was instrumental in

keeping brown rot to a minimum on the tree despite nearly constant

rain. Brown rot first hits fruits with insect wounds or that

are touching other fruits, so removing those peaches before the

sugar content was high enough to feed the rot lowered the overall

fungal pressure for the tree. (I've been picking fallen or

rotten fruits at least every other day since then, too, which also

helps, but there have been many fewer rotten peaches than I

expected given this year's weather.)

What all of this

sorting means in the real world is that I had at least half a

bushel of "goats" looking for a home Tuesday. Our freezer is

getting pretty full of fruit leather, but Mark talked me into

filling up the dehydrator one more time, then I opted to can the

rest of this batch of peaches. My goal is to have lots of

different variations

on preserved peaches to pick between this winter, allowing us to select our

favorite methods to focus on in later years.

My go-to source for

basic canning information at the moment is the National

Center for Home Food Preservation, but that website nearly steered me wrong

this time. If other sources on the internet are to be

believed, white peaches are like tomatoes --- only borderline

acidic enough for hot-water-bath canning. So even though the

NCHFP website didn't mention this, I added a tablespoonful of

lemon juice per quart to ensure my peaches are acidic enough to

can outside a pressure canner. Since I was adding lemon

juice, I decided to take NCHFP's advice on a different matter and

can in a very light syrup of 1-1/4 cups sugar in 10-1/2 cups

water, even though I'd been planning to can unsweetened peaches.

The rest of the

peaches on our kitchen tree look like sheep, although I'm sure a

few more will develop rot spots and bird bites in the next week or

so as they ripen. I plan to experiment next with making

peach sauce, then with a jam involving pectin, and then Mark will

probably talk me into turning the rest of the harvest into fruit

leather. That's not counting all the peaches I'll dice up

and add to our raspberry-and-blueberry-with-whipped-cream

desserts, of course.

Wild brambles eat through the Stihl FS-90R trimmer line pretty fast, but it's worth it for the extra garden space we've reclaimed this year.

Another rainy night,

another third of a bushel of white

peaches on the ground in the morning waiting to be

processed. I didn't feel like spending two mornings in a row

slaving over a hot stove, so I turned this batch into fruit

leather, but tomorrow's peaches are earmarked for jam. Kayla

is bringing me some green apples from her grandmother's trees

today and I'm sending her home with some of our peaches, so we'll

both be able to experiment with making jam using homemade apple

pectin.

Even though the

peaches are right outside the kitchen window and are thus on the

top of my mind, other fruit is still pouring in. This has

turned out to be our best watermelon year ever, even though two

of our three beds failed. I suspect the amazing flavor

from the remaining bed is due to constant subirrigation from roof

overflow. Perhaps those

new garden beds in the gully that were too wet for tomatoes

could be built up just a bit and then would become the best

possible spot for water-loving watermelon next year?

Daddy saved all of his

Egyptian onion top bulbs, and he tells me he has enough to allow

everyone who entered our

most recent giveaway to be a winner!

Daddy saved all of his

Egyptian onion top bulbs, and he tells me he has enough to allow

everyone who entered our

most recent giveaway to be a winner!

So, Adriana, Charles, Heather, Elizabeth, Jackie, Christine, jen,

WendP, and Nena, please email your mailing address to anna@kitenet.net and Daddy will get your

onions to you as soon as they dry out enough to go in the box

(probably next week).

Thank you all for entering!

We've been having starting

problems with the

ATV.

It was cool enough for long

sleeves this morning and the old battery groaned without cranking. What

is it about a marginal battery and the first cold spell of the season?

Filling a new battery with

fresh sulphuric acid was easy and only took a few minutes. We'll use a

trickle charger to power it up and hopefully have it ready to go for

tomorrow morning straw

hauling.

Kayla

not only brought me a big bag of green apples, she also copied

instructions out of a book (The Big Book of Preserving the Harvest) for turning those apples into

pectin. I mostly followed that recipe, which amounts to

extracting the juices from the apples in two parts. Here's

how....

First, I rinsed the

apples and quartered them, removing any really rotten spots, but

leaving cores, skins, and small dark spots in. I covered the

apples with water, brought them to a boil, then simmered for 15

minutes.

The next step is to

strain the apple pulp through cheese cloth, but I didn't have any

on hand. Luckily, the internet had a solution --- use an old

t-shirt instead. I had to double up the t-shirt so that

apple bits wouldn't squirt through the large holes that had

relegated the shirt to  the rag-bag, but the double thickness didn't

seem to be a problem. I put the shirt on top of a steamer,

the steamer on top of the pot that fits beneath it, and the apple

pulp in the shirt, then waited about ten minutes for the juices to

ooze out.

the rag-bag, but the double thickness didn't

seem to be a problem. I put the shirt on top of a steamer,

the steamer on top of the pot that fits beneath it, and the apple

pulp in the shirt, then waited about ten minutes for the juices to

ooze out.

Next, the author

recommends putting the apple pulp back in the pot, covering it

with water again, and simmering for another 15 minutes to get yet

more pectin out. At the end of that period, you're supposed

to remove the apple mixture from the heat and let it stand for ten

minutes before straining again. Since this second time

around is the last strain, you'll want to squeeze everything you

can out of the apple pulp, which means waiting until the contents

are cool enough not to burn your hands.

The author says

you'll harvest a quart of juice for each pound of apples you

started with, but I used less water for the second round of

boiling (just covering the pulp) and instead ended up with closer

to a pint of juice per pound of apple. A quart of the less

concentrated apple stock is supposed to be equivalent to half a

bottle (3 ounces) of store-bought liquid pectin.

I'll tell you more

about my first attempt to jam with this homemade pectin later, but

I wanted to close by mentioning other recipes I've seen for

extracting pectin from apples. One recipe recommends cooking

your apples for several hours, which would presumably concentrate

the pectin (although I thought I'd read that extended cooking

damages pectin). Another recipe simply calls for adding

apples with the other fruit while making jam instead of extracting

the pectin first --- in this case, it's recommended to put the

skins and pits in a cheesecloth bag to simmer with the jam then be

removed at the end, while the apple pulp is included with the

other fruit.

I'd be curious to

hear from anyone else who's experimented with using green apples

(or other non-store-bought components) to make your own

pectin. Please comment and share your experiences!

Putting a new

battery in the ATV didn't

help.

I was able to use the pull

cord to get it started and up on the trailer for a trip to the ATV

repair shop in St Paul.

Our storage onions

began their lives as seedlings in the middle of February, hit the garden

in April, and

were finally harvested this week. I actually would have

liked to leave them in the ground a bit longer until the tops

completely died back, but it's so wet some of the bulbs were

starting to rot. (You know the weather is damp when you hang

your laundry on the line Monday, take it in halfway-dry to drape

inside when it starts to rain that afternoon, and then find mold

growing on your still-damp clothes Wednesday morning.)

A bit of rot aside, the

onions look great this year, although I suspect there won't be

enough of them (again). I've actually been harvesting onions

out of the garden for the last month to cook with, so I guess the

harvest was really bigger than it seems from this photo.

A bit of rot aside, the

onions look great this year, although I suspect there won't be

enough of them (again). I've actually been harvesting onions

out of the garden for the last month to cook with, so I guess the

harvest was really bigger than it seems from this photo.

I spread our haul out

to dry on the front porch instead of on the drying

racks partly

from laziness, but also because I want to be able to pick through

the onions as they dry and use up problematic bulbs

immediately. Mark's mom has given us a screen rack I'm

looking forward to trying out with the onions...once the ATV is

back in working order and we can haul it in.

The light gates I've made for

our chicken

pastures tend to sag a

little over time.

It took over 8 gates to

figure out that the turn and block method with a scrap piece of wood is

a better match than the fancy looking hook and eye latch.

The hook and eye gate latch

is out of adjustment with just a small amount of sag, but the turn and

block method still works no matter how much the gate has shifted.

One of our Egyptian

onion winners

included a note asking for an update on our composting

toilet.

I'd actually been meaning to write a post on the topic, but it's

really more of a Mark post than an Anna post --- there's not much

to say when things just work. But Mark is still not entirely

excited by the idea of humanure (although he does agree our new

system is better than our old one), so hopefully you will all

forgive a bit of a light post from me on the weekend.

Keeping

wildlife out of the excrement has been the only real problem with our composting

toilet. After Mark added tin to the sides last winter, we

didn't see another problem until last week when something reached

through one of the few cracks still exposed. We'll cover

that opening up soon, and will definitely cover all the gaps

before moving to the next hole this fall. I had originally

thought the compost chamber needed those openings for aeration,

but there seems to be plenty of air flow through the open seat and

smaller cracks without leaving big gaps between the wooden walls

(as was proven by the sniff

test). I've seen a few flies hanging around, but not

even as many as are in the chicken pastures, so I figure our

sawdust covering is doing its job well there.

The size of the

composting chamber seems to have been perfect for the two of us

--- the goal is to fill one chamber every year so that by the time

we use up the third chamber, the first is ready to empty.

Our original chamber started looking pretty full a month or two

again, but summer weather also prompted rapid decomposition, so

the contents have sunk down at the same rate we've added to

them. We've used up an entire bin full of sawdust to fill this chamber,

meaning that our finished compost will actually consist primarily

of rotted sawdust and will presumably be quite good around the

base of trees.

I guess I had more to

say about humanure than I thought I did. Who knew!

Thank you Darren and Jake for the

comments on our DIY

Kill Cone alternative.

I always hold the head of

each bird until it bleeds out, but some chickens have a lot of fight

and wiggle their way free and back up in the bucket.

A few pieces of a 2x4

attached to the inside of the bucket with drywall screws decreases

movement while the chicken is in the bucket and seems like it would

prevent a bird from getting all the way out if you lost hold of its

head.

Jake uses a traffic cone,

which I bet would work better than a bucket if you can find one and

figure out an easy way to mount it at a comfortable height.

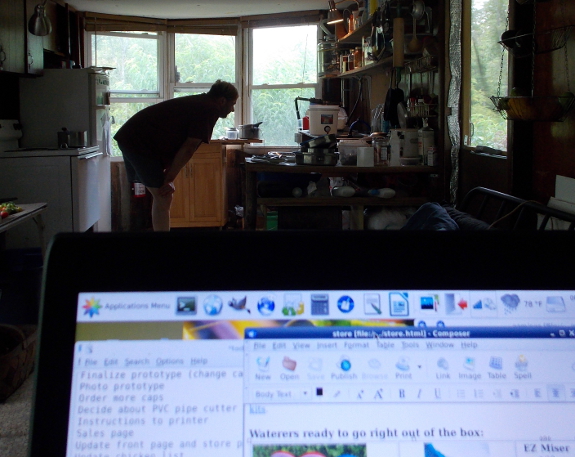

Mark and I have been hard

at work this summer developing a second-generation chicken waterer

that makes watering your flock even easier. At long last,

the EZ Miser

is ready to see the light of day!

If you're interested

in the inventing side of the story, check out this post I made about the trial and error process Mark went

through to create an even better waterer. Or just go read about the

EZ Miser itself.

I wish we could give

away waterers the way we do ebooks, but that would break the

bank. Instead, for this first week, I've taken 10% off the

price tag so that our loyal fans can afford to give the new

waterer a try.

And if you leave a note with your order, I'll even

throw in 20 Egyptian

onion bottom bulbs (while supplies last). I've been

saving these bottom bulbs for a special occasion since they're

more mature than the top bulbs I usually give away. You can

start eating the green onions from bottom bulbs nearly immediately

--- just let the plant keep at least half its leaves at any given

time.

We've had an EZ Miser prototype in our pasture for two months now,

and I can't figure out how we lived without it. I hope you

love it as much as we do, and I'll be very grateful if you spread the word

so your friends can get in on the early-bird deal too!

Even though we can't give

everyone a free EZ Miser, Mark and I do want to share this

new-and-improved chicken waterer with at least a couple of our

readers at no cost. So we're combining our 10%

off week with a

contest, with chicken

waterers as the prizes!

Even though we can't give

everyone a free EZ Miser, Mark and I do want to share this

new-and-improved chicken waterer with at least a couple of our

readers at no cost. So we're combining our 10%

off week with a

contest, with chicken

waterers as the prizes!