archives for 07/2013

(Photo-shy) friends

came over this weekend, so of course I wanted to feed them

something special. However, I realized the night before that

our bountiful

berries had

just passed their peak and we only had about a quart on the

bushes. How do you make a quart of raspberries feed five

people? Stretch it with chocolate, of course.

Torte

ingredients:

- 0.5 cups of almonds

- 2 ounces of dark chocolate

- 2 tablespoons of butter

- 2 eggs

- 0.5 cups of sugar

- 0.75 cups of flour

- 1 teaspoon of baking powder

- 0.5 teaspoons of salt

- 0.5 cups of raspberries

Topping

ingredients:

- 0.25 cups of heavy cream

- 6 ounces of dark chocolate

- 3.5 cups of raspberries

Preheat the oven to

350 degrees Fahrenheit and butter a 9-by-13-inch cake pan.

Toast the almonds

until they're lightly brown, then grind them for about 5 minutes

in a food processor until the nuts start to release their

oils. Meanwhile, melt the chocolate and butter in the

microwave.

At the same time,

beat the two eggs until they're fluffy. Add the sugar to the

eggs and continue beating. Then mix in the almond paste,

butter-and-chocolate mixture, flour, baking powder, and

salt. Once the batter is thoroughly mixed, lightly fold in

the raspberries, trying not to break them apart.

Pour the batter into

the pan, spread to cover the whole bottom, then bake until a knife

comes out clean. (This won't take long since the batter is

such a thin layer. I didn't time it though; sorry.

Maybe 10 minutes?)

While the cake is baking, heat the cream in a

saucepan over medium-high heat until it just boils. Remove

from the heat, stir in the chocolate, and continue stirring until

the chocolate melts and mixes with the cream.

While the cake is baking, heat the cream in a

saucepan over medium-high heat until it just boils. Remove

from the heat, stir in the chocolate, and continue stirring until

the chocolate melts and mixes with the cream.

Once the cake is

done, spread the chocolate-and-cream mixture over top, then

sprinkle on fresh raspberries generously. (We had a couple

of blackberries and included them, and I'll be blueberries would

be equally delicious.) Cool for a few hours to set the

chocolate.

Serves about 10 and

combines the taste of fresh and cooked raspberries with rich

chocolate and nutty almonds, with none of the flavors overwhelming

the others. Definitely a favorite for fresh-fruit and

dark-chocolate lovers like me!

(Based loosely on this

recipe.)

One of our most-read

posts is a reader's

rebuttal to my

square foot gardening lunchtime series. This weekend, Ron

sent me a followup detailing the next three years of his gardening

trials. I'll let him tell you about the seven-year-old,

square-foot garden in his own words.

If there is any interest,

I would like to add some up-to-date information on my square foot

garden and offer some answers to raised questions.

If there is any interest,

I would like to add some up-to-date information on my square foot

garden and offer some answers to raised questions.On this date, June 29, 2013, I now have 19 square foot garden beds (last reported was 13 - I've added six, 3' x 8' beds). This is so addicting!!! I am now in my seventh year.

In the garden area, the grass is now gone (covered by newspaper, cardboard, mulch and woodchips). I found the constant mowing, trimming and pulling of weeds a waste of time and a real pain. The most recent benefit is when the latest storms hit, my soil became a "mosh pit" of clay while the mulched area was well drained and workable.

Your readers have a real

fascination with my bamboo trellis. It was made from a childhood

memory of an old Italian gardener neighbor. Somewhat a testament

to him. He truly loved his garden and would always go that

extra mile to make things, just right, just so. This memory goes

back to the 60's.

Your readers have a real

fascination with my bamboo trellis. It was made from a childhood

memory of an old Italian gardener neighbor. Somewhat a testament

to him. He truly loved his garden and would always go that

extra mile to make things, just right, just so. This memory goes

back to the 60's.It took me hours to construct and was based on using 8 foot sections of bamboo, jute twine and a refamiliarization of an old Boy Scout handbook with lessons on "rope lashing." After a couple of hard Upstate New York winters, the jute rotted and had to be constantly maintained.

Needing something more beefy and multifunctional, I discovered cattle fencing with wood framing. Since my standard beds are 3' x 8', I can simply unbolt my frames from the beds and use elsewhere (crop rotation). I am also am a user of 24" Texas Tomato cages. With them, in a 4' x 4' bed, I can plant 16 each saladette or cherry tomato plants and not have them tumble over with the weight of hundreds and hundreds of tomatoes.

In one 3' x 8' bed, I have

24 cucumber plants started and growing totally vertical. That's

one plant per square foot.

In one 3' x 8' bed, I have

24 cucumber plants started and growing totally vertical. That's

one plant per square foot.Yes, the elegant bamboo frame is now gone (not really, taken apart and repurposed). I still enjoy the memory of making it and the images of my old Italian neighbor in his garden who spent the majority of his day there tending it and feeding his family.

I constantly experiment. The cardboard boxes in the beds shown, were in fact, the mini planting areas for fingerling potatoes. The boxes allowed me to bury deep and by stacking another, I could hill the potatoes higher by adding another cardboard box. Did it work, yes, but not really a sure winner of an idea. Win some, lose

some.

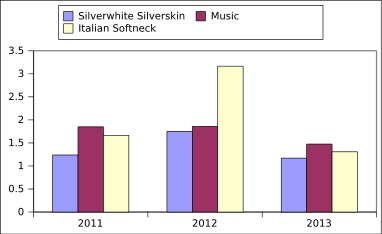

This year experiments include 3 full 3'x8' beds of fall planted hard neck rocambole garlic. I have added Azomite, kelp meal, and I just started spraying compost tea to this years' crop. Shortly, I hope to obtain rabbit manure, compost it, and then add red wigglers for their castings. All to add to the beds in the fall. It's all about building up the soil.

We are now deep into canning, freezing, and dehydrating. This year's garlic scape pesto is beyond belief!

As a reminder, I live in

suburbia. My neighbors pray to the ChemLawn Gods. "Why grow

your own when a grocery store is a half mile away?" So

sayeth the neighbors. Frankly, trying to live a sustainable

lifestyle up here is a hard sell with this bunch. Wait when they

see the chickens in a few years!

As a reminder, I live in

suburbia. My neighbors pray to the ChemLawn Gods. "Why grow

your own when a grocery store is a half mile away?" So

sayeth the neighbors. Frankly, trying to live a sustainable

lifestyle up here is a hard sell with this bunch. Wait when they

see the chickens in a few years!I believe, loosely, with slight modifications, square foot gardening works and is legitimate method for all experience levels based on their available land, soil conditions and neighborhoods. I will also note and praise, I envy your lifestyle and your more rural conditions.

Would also like to add, in addition to the methods used by the Dervaes family, I would also recommend and make mention to your readers to watch the Youtube videos of Laszlo Horvath and GrowingYourGreens. They have taken suburban square foot gardening to new levels and demonstrate its viability.

Best wishes from Upstate New York.

--- Ron

Anna and I have been talking

about the sunroom

addition and we both

realized at the same time that we don't eat as many lemons as we once

did. I gave up Iced Tea a couple of years ago when I discovered most black

teas have high amounts of Fluoride due to chemicals used in the

growing process.

We had some friends over

recently and they happily agreed to give our Myers

Lemon tree a good home.

I haven't regaled you

with tales of cover crops in a while, but that

doesn't mean we haven't been experimenting. First of all, cutting

rye with the weedeater right at ground level was highly effective, although my

scything a little higher up resulted in some resprouting.

The plants we cut early, just as they were barely starting to

bloom, were also more likely to resprout. A final warning

--- the rye did hold onto nitrogen much harder than any other

cover crop I've grown, so a few broccoli sets I transplanted

directly into manure poured on top of the stubble took a week or

two to really start getting the nutrients they needed. But,

overall, we were very pleased with our rye experiment and will

definitely repeat it, especially in problematic soil areas where

the rye built masses of organic matter.

Most of the back

garden is fallow this year as I prepare

it for next year's tomato crop, so I broadcast buckwheat seeds into the rye before

Mark cut it. Mark and I both spread our pee on certain areas

for a week or so (until the buckwheat started sprouting) to add

nitrogen to the ground, but the buckwheat is struggling. It

definitely came up well through the rye stubble, but I've always

had a problem getting much growth out of buckwheat in areas with a

very high groundwater, and this year is no exception. We'll

get a bit of growth out of the back garden buckwheat, but I'm

thinking of trying some sunflowers next.

In contrast, the

buckwheat I've planted into good garden areas is over twice as

large and is thriving. I've already made inroads into my buckwheat

challenge,

having planted about 4.5 gallons of seed so far this spring and

summer.

But our big

experiment came into my inbox as a whim. Harvey

Ussery is

testing out sunn hemp (Crotalaria juncea), and wanted to send out

samples to his readers for us to try in different parts of the

country. This legume gets up to eight feet tall and produces

huge amounts of biomass before frosts kill the plants in the

fall. You can cut the plants at 60 days as a high-nitrogen

addition to the garden or compost pile, or wait a bit longer, at

which point the carbon levels rise and sunn hemp becomes a quality

mulch. In addition, cutting the plants once at four feet

tall results in resprouting and even more biomass

production. I slipped the seeds into gaps in the forest

garden where broccoli was coming out, and I envision the

high-carbon stems at the end of the year will make good mulch

around fruit trees. I'll keep you posted about the results

of my experiment, and you'll be able to read how sunn hemp did for

us and other experimenters this fall or winter in an article by

Harvey Ussery in Mother Earth News.

We recently noticed our first

deer damage of the year.

It's hard to know for sure,

but we think she came in through our weakest fence line.

Weed eating around the fence

and repairing the weak spot might help to make this deer think twice

before coming in, but it might also be time to ask the local Game

Warden for another deer

killing permit.

It's been a while

since I've written a sumup of the garden, which is mostly because

both the produce and the weeds are growing like crazy.

Broccoli and pea season has come and gone. For about a week

in the middle of June, the broccoli heads became so full of

southern cabbageworms that I barely wanted to cook them, but then

the checkered white butterflies stopped laying eggs, and recent

heads have been pristine. (The more common cabbage

worms from the cabbage white are still around in small

numbers, but they're not nearly as big of a deal for us.)

These early crops

were quickly replaced by cucumbers, which immediately began to

overwhelm us to the point where we had to give extras away.

Although I could cut back on my planting next year, it's nice to

have a quick, easy vegetable that scales up to feed an unlimited

number of mouths on a moments' notice, so I probably won't scale

down.

We're also enjoying

yellow crookneck squash, green beans, and the first huge cabbage

heads. Monday, Mark and I sampled cattail flowers for the

first time, which you're supposed to pick when they're still

enclosed in their sheath, remove from their husk, boil for 3

minutes, then eat like corn on the cob. Although Eric in

Japan reported cattails taste like avocadoes (one of our favorite

storebought addictions), Mark and I were less than impressed by

the cattail heads and deemed them mere survival food.

While waiting for the tomatoes to ripen

(which will mark the beginning of major preservation season),

we're staying busy planting late crops, renovating

the strawberry beds, weeding, mowing, and saving

seeds (kale, tokyo bekana, and peas so far). The kale

plants I left to go to seed are so vigorous, I'm considering using

the vegetable as a cover crop in areas that don't need to be

planted until mid summer, and the dying plants are still doing

double duty by sheltering a song sparrow nest. Kale plants

that have already given me their quota of seed (and that aren't

housing wildlife) made good deep bedding in the chicken coop.

While waiting for the tomatoes to ripen

(which will mark the beginning of major preservation season),

we're staying busy planting late crops, renovating

the strawberry beds, weeding, mowing, and saving

seeds (kale, tokyo bekana, and peas so far). The kale

plants I left to go to seed are so vigorous, I'm considering using

the vegetable as a cover crop in areas that don't need to be

planted until mid summer, and the dying plants are still doing

double duty by sheltering a song sparrow nest. Kale plants

that have already given me their quota of seed (and that aren't

housing wildlife) made good deep bedding in the chicken coop.

It continues to rain

nearly every day, but so far I haven't seen the fungal diseases

I've been dreading. Our first peaches (Redhaven) are already

thinking of ripening up, and despite insect damage to many fruits,

I suspect we'll enjoy a bountiful crop.

How's your garden

doing now that summer is officially here?

Aerial line maintenance has caused two power outages this week.

A short summer power

outage is no big deal, though. Anna whipped up supper on the

camp stove and we enjoyed an afternoon of quiet.

It does remind us to check

back over our emergency

preparedness goals. We've come a long way, but still

have several items to check off the list.

Due to some dieoff

during our final

silkworm week,

we ended up with only ten silkworm cocoons, but that should be

enough to carry our livestock on to the next generation. I

was amazed by the colors of the cocoons, especially the brilliant

orange one that almost looks fake. My understanding is that

commercial silkworm producers select for white cocoons so that

they don't have to bleach the silk before dying it.

One of our chicken blog readers wrote in to ask

if she could have our cocoons after we're done with them, which

made me realize it's far from common knowledge how silk is

produced. Unfortunately, you have to decide whether to use

your cocoons to make silk or whether to let the moths escape and

breed, so our cocoons will end up being useless from a fiber

perspective.

If you're not trying to

breed the moths, though, it is quite feasible to make silk on the

backyard scale if you're up for some tedious labor. Just

boil the cocoons once they're fully formed, which kills the pupae

inside and dissolves the glues binding the silk together.

Each cocoon is made up of one extremely long strand, which you can

tease apart and wind up, then weave like any other thread.

The reason you can't raise the moths and still use the thread is

that the mature insect gnaws its way to freedom, breaking that

long thread into many smaller pieces that are much less useful.

Mark and I are still

on the fence about whether silkworm culture is an efficient use of

time, but we're definitely going to breed our moths and start

tweaking the procedure so it works better. Stay tuned for

round two, coming up next month.

We celebrated Independence Day with some bucket

hauler sparks.

I used 16 heavy duty exterior wood screws for a second attempt at plywood

attachment.

They ended up protruding through the plywood side and needed to be

grinded off to achieve a smooth surface. I also used 4 bolts with

washers and nuts to be on the safe side. The nut side sticks out a bit,

but I located each hole so it fits in a gap between buckets.

The interest in Mark's

post about fighting tomato blight with pennies has been

astounding. Even though I'm dubious about pocket change's

effect on fungal diseases, that post's popularity made me decide

to experiment with a slightly different form of copper.

My budget for the

project was the $80 we've made in ad revenue from folks coming to

check out our tomato blight post, but I tacked on another $10 so I

could try two types of copper --- this

expensive and high-quality copper screen and this

ultra-cheap mesh.

Mark cut the screen into eight sections (each of which was a foot

square with a  notch to allow the screen to slide around the

tomato stem), and I cut the mesh into four lengths that cover

about the same area. My test subjects consisted of a row of

yellow romas, where I alternated control (no copper), mesh, and

screen beneath subsequent plants.

notch to allow the screen to slide around the

tomato stem), and I cut the mesh into four lengths that cover

about the same area. My test subjects consisted of a row of

yellow romas, where I alternated control (no copper), mesh, and

screen beneath subsequent plants.

The theory is that

the anti-fungal properties of copper will prevent fungal spores

from being splashed up from the soil line into the lower leaves

(where blight usually first takes hold of a tomato plant).

Organic farmers sometimes  use powdered copper on tomatoes for this

purpose, but that technique is dicey from a permaculture

standpoint since the powdered copper gets into the soil and kills

beneficial fungi as well as disease-causing species. Only

time will tell whether a solid copper mesh will serve the same

purpose without the harm to ecosystem life.

use powdered copper on tomatoes for this

purpose, but that technique is dicey from a permaculture

standpoint since the powdered copper gets into the soil and kills

beneficial fungi as well as disease-causing species. Only

time will tell whether a solid copper mesh will serve the same

purpose without the harm to ecosystem life.

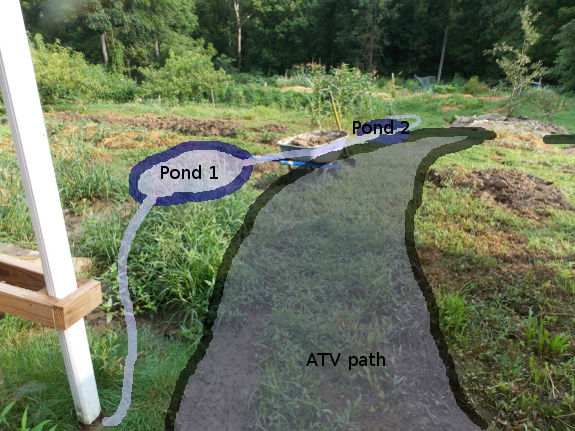

We got the ATV back from the shop last week and

it's better, but not quite fixed.

The problem was no brakes. We

had the back pads replaced and made sure the front pads had enough life

in them.

It slows down, but I have to

pump the brake handle and be careful not to hit anything. I think maybe

the caliper got damaged and we may have to plan on having it replaced

in the future, but for now we'll get by with half brakes so we can get

caught up on manure hauling.

I hadn't really

intended to get back into Langstroth beekeeping anytime soon, but

when

the bees speak,

I listen. I figured I might as well leave our new swarm in

the boxes they chose...with a few modifications.

My first step in the

modification process was to brainstorm the primary features of a Warre hive, and ways I might easily

modify the Langstroth hive to serve the same purpose:

| Warre hive

feature |

Purpose |

Possible

retrofit to Langstroth |

| Quilt |

Insulation and winter drip

prevention |

Modify an extra super to

become a quilt. (Easy.) |

| Fancy roof |

Air flow? |

Built a similar roof.

(Hard.) |

| Small entrance |

Not positive, but bees select

for this in the wild, so it must be important, perhaps in

guarding the hive and/or maintaining Nestduftwarmebindung. |

Entrance reducer. (Easy.) |

| Thick hive walls |

Insulation |

Rebuild boxes out of thicker

boards. (Hard.) |

| Top bars |

Prevent varroa mites using

small cell size. |

Foundation

strips. (Easy.) |

| Smaller boxes |

Winter temperature

maintenance? |

(I don't like the idea of

using all supers instead of deeps, which would be easy, and

am not sure this is actually an important feature of the

Warre hive.) |

| Hive opened only once a year |

Maintain Nestuftwarmebindung

and don't make bees waste propolis. |

Raise up base of hive so I

can photograph underneath and monitor bees' progress that

way. (Moderate.) |

| Nadiring |

A subset of the feature

above. |

Add larger handles on sides

of the boxes so entire hive can be raised at once for

nadiring. (Easy.) |

| Allow swarming |

Creates a break in disease

cycle. |

Don't use swarm

prevention techniques. (Easy. But, this is

one feature of a Warre hive I might consider ditching in the

long run since it drastically reduces honey

production. The health of the bees is my first

priority, though, so I'm keeping it for now.) |

| Queen works throughout hive. |

Allows cycling of wax if you

crush and strain, which prevents disease. |

Don't use excluder, do nadir,

and remove honey from top. (Easy.) |

Once we get a spare

minute in the garden, I plan to apply the easiest of these

features to our Warre hive, notably the quilt and raising the box

up so I can slide my camera underneath. (I already installed

foundation strips so the bees will build most of their own

wax.) The bees shouldn't need to be nadired this year since

they already have the equivalent of four Warre hive boxes, but

Mark and I will plan to suit up (or wait until winter) and add

handles to the boxes before next spring. It will be

interesting to see whether a Langstroth hive with a few simple

modifications will be as effective as the more expensive and less

common Warre equipment.

There's fuzzy evidence that a

deer is still sneaking in at night...but the damage lately has been

minimal.

I was happy to see one of the

old mechanical

deer deterrents start up

with no problem, although it didn't seem to stop this one...but maybe

the noise shortened her stay.

Joey brought over

four pork chops and threw them on the grill, along with some of

our overabundant summer squash and some storebought corn.

The pork chops were pastured, brined overnight in an

herb-salt-and-water solution, then cooked a bit faster than we'd

planned. (In the photo above, Joey's letting them finish off

atop some ears of corn to get the meat further away from the

heat.)

I'd never tasted pastured pork before, but every other

pastured meat I've tried has been ten times better than feedlot

produce. So I shouldn't have been surprised that this pork was

also phenomenal. We'll definitely be making an order of our

own soon.

I'd never tasted pastured pork before, but every other

pastured meat I've tried has been ten times better than feedlot

produce. So I shouldn't have been surprised that this pork was

also phenomenal. We'll definitely be making an order of our

own soon.

Meanwhile, if you

live in or near Rogersville, Johnson City, or Knoxville,

Tennessee, J.E.M. Farm likely delivers to your

town and even offers a CSA. I'm looking forward to a field

trip to tour their operation once our own garden slows down for

the year.

We used some basic tin snips

to cut the copper

screen material into

squares.

If I do this again I'll

remember to wear gloves to avoid being cut from the sharp edges.

Every time I looked at the

huge, red-blushed peaches on our Redhaven tree last week, I

reminded myself the chances of eating any were slim to none.

We'd seen the sun for about ten hours of that week and had enjoyed

rains at least once a day, so I knew brown rot would set in before the

fruits ripened.

Every time I looked at the

huge, red-blushed peaches on our Redhaven tree last week, I

reminded myself the chances of eating any were slim to none.

We'd seen the sun for about ten hours of that week and had enjoyed

rains at least once a day, so I knew brown rot would set in before the

fruits ripened.

Sure enough, Friday I

noticed a rotting peach in the center of the tree. I removed

it, but by Sunday, five more peaches had come down with the fungal

disease. Unless the weather miraculously stops thinking we

live in a rain forest, I suspect each fruit will succumb as it

builds up enough sugars to feed the fungus.

In the meantime, I'm

trying out some mitigating measures. The first year we

fought brown rot, I didn't know what it was and wasn't paying

attention, with the result that we basically got no crop.

This time around, I'm using the same techniques I use on other

fungal diseases --- an eagle eye and removal of infected tissue as

quickly as possible. The jury's still out on whether that

will allow at least a few peaches to ripen to perfection on the

tree.

In the meantime, I'm

trying out some mitigating measures. The first year we

fought brown rot, I didn't know what it was and wasn't paying

attention, with the result that we basically got no crop.

This time around, I'm using the same techniques I use on other

fungal diseases --- an eagle eye and removal of infected tissue as

quickly as possible. The jury's still out on whether that

will allow at least a few peaches to ripen to perfection on the

tree.

Meanwhile, I'm also

experimenting with ripening up peaches inside. Granted, I've

read that peaches don't really ripen off the tree, but merely

soften. Still, I suspect they'll be at least as good as

storebought fruit, and will definitely be better than

nothing. The question is whether the brown-rotted fruits

(with the bad spots cut out) will ripen in the fridge, or whether

I need to pick fruits before they're infected. I'm trying a

few of each to see.

I have to confess that my

grand plan of slowly working through both Gaia's

Garden and Introduction

to Permaculture

in tandem with Will

Hooker's online permaculture course fell by the wayside. My edition of

Mollison's book didn't have the right page numbers, and it was

more interesting than either of the other information sources, so

I zipped ahead to finish Introduction to

Permaculture

before listening to more lectures or reading more of Gaia's Garden.

I have to confess that my

grand plan of slowly working through both Gaia's

Garden and Introduction

to Permaculture

in tandem with Will

Hooker's online permaculture course fell by the wayside. My edition of

Mollison's book didn't have the right page numbers, and it was

more interesting than either of the other information sources, so

I zipped ahead to finish Introduction to

Permaculture

before listening to more lectures or reading more of Gaia's Garden.

Which is all a long

way of saying --- even though I didn't get into Mollison's book

when I first tried it several years ago, I now consider Introduction to Permaculture

to be the best way for those new to permaculture to get a

sampling of dominant ideas in the field. You'll be

introduced to Salatin-style grazing, greywater management, no-till

gardening, and much more, and will be inspired by line drawings

that make you want to jump out there and put some of these ideas

into action. And while I'm usually dubious of books that

contain no photos (is this all just philosophizing, or has the

author actually tried it?), Mollison is clearly a doer who seasons

his text with  warnings about when each

project is likely to succeed or fail. 90% of the time, I

even agree with him, even though Mollison gardens in dry Australia

and I garden in wet Appalachia.

warnings about when each

project is likely to succeed or fail. 90% of the time, I

even agree with him, even though Mollison gardens in dry Australia

and I garden in wet Appalachia.

Stay tuned for some

of the highlights of Bill Mollison's book later in this week's

lunchtime series, and consider dropping by our chicken blog later in the week where

I'll be relating Mollison's tips for grazers. Or, if you're

just tuning in, you might be interested in this post from a few

weeks ago about Mollison's

approach to forest gardening.

| This

post is part of our Mollison's

Introduction to Permaculture lunchtime series.

Read

all of the entries: |

We noticed more deer damage

this morning but this time we were able to follow her trail to a spot

where we think she might be jumping over the fence.

It's a spot where we don't

have a chicken

moat.

Using two tall trees to

attach to we were able to double the fence height on that section from

5 feet to 10 feet.

"Why not just give in and

spray high risk crops with Neem Oil (or whatever fungicide you are

comfortable with)?" --- Robert

"Why not just give in and

spray high risk crops with Neem Oil (or whatever fungicide you are

comfortable with)?" --- Robert

I get this question a

lot, or the related "Why don't you just spray an

insecticide?" Folks familiar with organic gardening are used

to "safe" sprays like neem oil that do many of the same jobs as

non-organic pesticides or fungicides. But my philosophy is a

little different.

No matter how

specific you think your organic spray is, it's going to do damage

to beneficials in the same category as the problem species you're

trying to combat. The question is, are you willing to harm

the fungi in the soil that help your trees suck up micronutrients,

resulting in a tree that's going to need more help every

year? How about if that also means the food from the tree is

going to be less nutrient dense? Basically, by spraying

organic killers of any kind, I'd be going back to

storebought-produce quality, and the goal of growing our own is to

feed ourselves tastier and more nutritious food than we could buy

in any store.

Without chemicals, you have to be a bit

smarter, willing to experiment, and able to handle failures.

In some cases, we've come up with systems that work perfectly for

our climate. For example, instead of spraying Bt

to prevent the dastardly vine

borers that pretty much kill all squash in our region, I now

take a multi-prong (but chemical-free) approach. First, I

chose varieties that are less tasty to vine-borers (butternut

squash and yellow crookneck squash), which solves the problem for

the winter squash entirely. With summer squash, even the

crooknecks succumb to the vine borers eventually, but as long as I

plant a new bed of squash every two weeks in the summer, we

still end up giving bagsful away.

Without chemicals, you have to be a bit

smarter, willing to experiment, and able to handle failures.

In some cases, we've come up with systems that work perfectly for

our climate. For example, instead of spraying Bt

to prevent the dastardly vine

borers that pretty much kill all squash in our region, I now

take a multi-prong (but chemical-free) approach. First, I

chose varieties that are less tasty to vine-borers (butternut

squash and yellow crookneck squash), which solves the problem for

the winter squash entirely. With summer squash, even the

crooknecks succumb to the vine borers eventually, but as long as I

plant a new bed of squash every two weeks in the summer, we

still end up giving bagsful away.

In other cases, I

hand pick and (impatiently) wait for the natural predators of pest

insects to show up. For example, we used to be overrun with

asparagus

beetles, but I nearly wiped out their population by

thrice-weekly squashing sessions. This year, I saw some show

up  again for the first time in years, but

after a round of squashing, I started noticing more wheel bugs and

ladybug larvae on the asparagus and no more asparagus beetles.

again for the first time in years, but

after a round of squashing, I started noticing more wheel bugs and

ladybug larvae on the asparagus and no more asparagus beetles.

Fungi don't seem to

have natural enemies (or at least I can't see them with my naked

eye. Some sources suggest that good fungi build up on plant

surfaces and battle the bad fungi for space.) So I plant

blight-resistant varieties, site fungal-prone plants in the

sunniest part of our garden, pluck off fungal damage as soon as I

see it, and trellis plants like cucumbers so they stay away from

the damp ground. And, if worst comes to worst, I rip out

varieties (and sometimes whole species) that can't handle our

damp.

Which is all a long

way of explaining that our peaches are still on probation, and if

I can't find a cultural control for brown rot, I'm willing to let

them go. Sure, they're one of my favorite fruits, but I

could put the same space and energy into more dependable June

apples, blueberries, blackberries, and late raspberries if I have

to. (Hear that peach trees --- either shape up or ship

out!) I'd rather eat healthier, tastier food of a

second-favorite variety than throw chemicals into the ecosystem I

live in and eat out of.

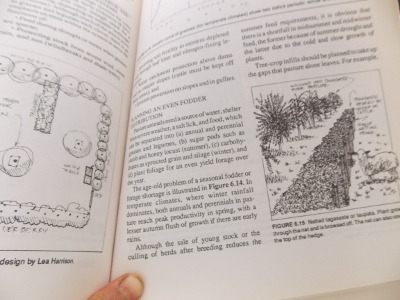

One of my favorite

chapters in Bill Mollison's Introduction

to Permaculture was the one on housing. In addition to

all of the mainstream information on passive solar (with or

without an attached greenhouse), closing and opening windows to

manage air temperature, thermal mass, and shade trees, he

introduced a concept I'd never heard of --- the shade house.

One of my favorite

chapters in Bill Mollison's Introduction

to Permaculture was the one on housing. In addition to

all of the mainstream information on passive solar (with or

without an attached greenhouse), closing and opening windows to

manage air temperature, thermal mass, and shade trees, he

introduced a concept I'd never heard of --- the shade house.

A search of the

internet suggestions that Mollison's shadehouse may sometimes be

known as a lathe house. Regardless of the name, the

structure is placed on the north side of the home in our

hemisphere, has a partially covered top to provide shade, and is

coated with vegetation inside and out. Vines are often

trellised up the sides, and the top may be made of trellis

material to allow the vines to continue their growth there, or it

might consist of multiple layers of snow fencing or one layer of

reflective shade cloth. Water tanks inside or around the

structure can provide extra thermal mass.

The shade house

produces a very cool environment to feed air into the house in the

summer. Opening a high window on the opposite side of the

house (or a vent in the top of an attached greenhouse) lets hot

air escape, then a vent low in the wall attached to the shade

house pulls in cool air from that structure to replace the warm

air.

A shade house also provides

other much-needed uses on the summer homestead as well. You

can add an outdoor bathing station, and should definitely consider

raising mushrooms there and rooting cuttings in the shade.

We've yet to find the best environment for mushroom logs in the

summer, and although my cuttings do pretty well in the semi-shade

of the porch edge, I can see how a shade house would make

propagation even easier.

A shade house also provides

other much-needed uses on the summer homestead as well. You

can add an outdoor bathing station, and should definitely consider

raising mushrooms there and rooting cuttings in the shade.

We've yet to find the best environment for mushroom logs in the

summer, and although my cuttings do pretty well in the semi-shade

of the porch edge, I can see how a shade house would make

propagation even easier.

The one thing I'm

unsure of is whether a shade house would make the main house too

moist in our wet climate. Constant rain during summers like

this one mean that fabrics left to dry over chairs in the house

often mold before the water leaves them, and swamp coolers

definitely won't work on our humid farm. Part of the benefit

of shade houses is supposed to be adding humidity to the air, so

maybe they're not compatible with our area after all?

| This

post is part of our Mollison's

Introduction to Permaculture lunchtime series.

Read

all of the entries: |

No deer damage last night,

but we're still shoring up our perimeter.

This new gate will rule out

the possibility of her walking in the way we enter.

"Are you Anna Hess's

husband?" asked the clerk at one of the local hardware stores Mark

frequents. Mark admitted that he was, indeed. "My

daughter's been reading your

wife's book.

The library wants it back, but she's not done with it. Do

you think she could buy a copy from you?"

"I've got a better

idea," Mark answered. "Would she like a job?"

Which is all a long

way of explaining how Kayla showed up on our doorstep a month or

so ago. She's an industrious helper who doesn't get bored

when I ask her to weed all morning, she's genuinely interested in

all of my crazy garden experiments, she can handle slogging

through the mud to get to work, and (best of all) she has a large

enough extended family to eat all of our extra cucumbers and

summer squash.

I've decided the

paperback experiment was a total success. If it takes

writing a book to find a helper like Kayla, it's worth every

minute at the keyboard.

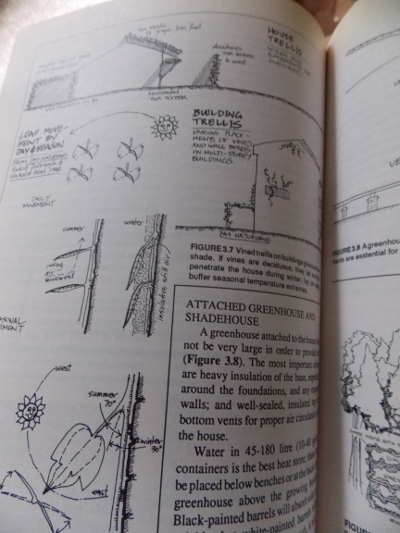

Of course, the tips from

Mollison's book that I'm most likely to put into action pertain to

plants and ecosystems. I especially enjoyed the way Mollison

suggested alternative uses for features I'd already

considered. For example, I tend to deal with my boggy ground

by building up so I can plant there, but perhaps I should instead

dig out some areas to create open water. (The swamp downhill

from the East Wing might be a good location for

bog-to-shallow-pond experimentation.) And Mollison suggests

considering hedges to be mulch sources and weed barriers as well

as animal barriers and producers of food.

Of course, the tips from

Mollison's book that I'm most likely to put into action pertain to

plants and ecosystems. I especially enjoyed the way Mollison

suggested alternative uses for features I'd already

considered. For example, I tend to deal with my boggy ground

by building up so I can plant there, but perhaps I should instead

dig out some areas to create open water. (The swamp downhill

from the East Wing might be a good location for

bog-to-shallow-pond experimentation.) And Mollison suggests

considering hedges to be mulch sources and weed barriers as well

as animal barriers and producers of food.

Meanwhile, Mollison

goes into depth about using plants to mitigate heating and cooling

issues around your

home. While deciduous shade trees are great, we just don't

have room for such a large plant on the south side of our trailer

--- a maple would take up half the garden (and would impact the

powerline). But I've been planning to trellis vines against

the south side of the porch and trailer instead, and Mollison

heartily approves of the idea. My

first attempt this spring with annual vines failed because

it turns out that the soil there is very wet and clayey, so I'm

dumping masses of weeds in the spot this summer to raise the soil

up and increase the organic matter content in preparation for fall

planting of some kind of perennial vine (probably home-propagated

grapes).

issues around your

home. While deciduous shade trees are great, we just don't

have room for such a large plant on the south side of our trailer

--- a maple would take up half the garden (and would impact the

powerline). But I've been planning to trellis vines against

the south side of the porch and trailer instead, and Mollison

heartily approves of the idea. My

first attempt this spring with annual vines failed because

it turns out that the soil there is very wet and clayey, so I'm

dumping masses of weeds in the spot this summer to raise the soil

up and increase the organic matter content in preparation for fall

planting of some kind of perennial vine (probably home-propagated

grapes).

On a related note,

did you know that hanging plants are supposed to cool the

surrounding area? I'd always thought the pots of dangling

ferns I notice in southern homes and porches are just for

aesthetics, but I can see how the plants might do their part in

keeping conditions comfortable nearby. Similarly, all those

fountains in Mediterranean countries are meant to add humidity

(and thus coolness) to the air, while ivy growing over buildings

is reputed to reduce heat  gain in the summer by 70%

and heat loss in the winter by 30% --- homegrown insulation!

Finally, a courtyard pond can buffer heat both during the summer

and the winter.

gain in the summer by 70%

and heat loss in the winter by 30% --- homegrown insulation!

Finally, a courtyard pond can buffer heat both during the summer

and the winter.

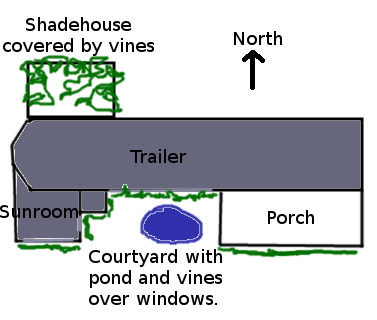

While I'm unlikely to

put all of these ideas into action right away (or maybe ever), I

couldn't help mocking up a design for the truly integrated

permaculture trailer. With the help of a few plants, we

might make our singlewide even more livable over time.

| This

post is part of our Mollison's

Introduction to Permaculture lunchtime series.

Read

all of the entries: |

We hauled some straw in with

the new

and improved bucket hauler

today.

Conditions are muddy, but it

seemed to handle the uneven driveway just fine.

Four bales might be the limit

for straw due to the load being top heavy.

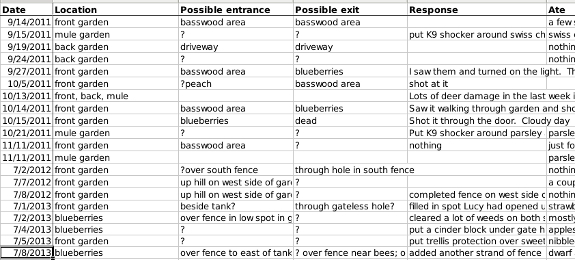

We take our war against the deer very

seriously, with multiple lines of defense, obsessive

data-gathering, and a complete

willingness to shoot on sight. And we seem to be winning. As you can

see from my spreadsheet above, there hadn't been a deer in the

garden for 12 months before the most recent raid, and before that

was an eight month gap. I'm hopeful our most recent work

will keep the deer out for at least another year, maybe longer.

We take our war against the deer very

seriously, with multiple lines of defense, obsessive

data-gathering, and a complete

willingness to shoot on sight. And we seem to be winning. As you can

see from my spreadsheet above, there hadn't been a deer in the

garden for 12 months before the most recent raid, and before that

was an eight month gap. I'm hopeful our most recent work

will keep the deer out for at least another year, maybe longer.

So what have we done

to improve the situation this time around? Mark mentioned clearing

tall weeds that shelter deer along the fencelines, putting

two of our mechanical deer deterrents back into action, adding

height to a troubled fence spot, and gating

in a gap we often walk through. We also put the wireless

deer fence

beside the most-nibbled spot and baited it with peanut

butter. I'm not sold on this little gadget actually doing

anything, but this is the kind of situation where it might come in

handy --- when a single deer is targeting one high-value spot.

We didn't stop

there. We built a trellis barrier around the dwarf apples,

which seem to be one of the deer's favorite foods. Mark

hunted down the trail

camera and

installed it to start collecting more data, and I put more trellis

material over the strawberry and sweet potato beds that are

closest to the incursion spot.

But those are really just stop-gap measures. Our

long-term goal is to moat the entire homestead,

since moats seem to be close to 100% effective at deterring deer,

even if the fences that make them up are only four or five feet

tall.

But those are really just stop-gap measures. Our

long-term goal is to moat the entire homestead,

since moats seem to be close to 100% effective at deterring deer,

even if the fences that make them up are only four or five feet

tall.

Actually, we've

already got most of the homestead moated if you count the

precipice at the edge of our plateau as a moat. (I

do.) I'd been considering leaving a deer path to let

wildlife walk between the pastures-to-be around the starplate

coop and our

blueberry patch so I'd still be able to shoot deer out the

living-room window, but now I'm thinking we'll hook those pastures

directly into our existing perimeter fence to moat that area

too. I'm not quite sure what we use we could put to a moat

above the well since we want to keep manure out of that area to

protect our drinking-water quality, but I'm sure we'll think of

something.

The new lawn

trailer bucket hauler had

its first horse manure run today.

My new method of stacking and strapping 7 buckets near the

cab brings the capacity to 28...add one bucket to the nearby worm bin

and then 3 trips with the bucket hauler and that equals a serious amount

of organic matter.

The tomatoes are late

this year and the cabbages are copious. The pair of events

is merged in my thinking because my primary use for spring

cabbages is as part of the stock for tomato-based

soups, meaning

that I want tomatoes and cabbages at the same time and in

proportion to each other. While we can definitely eat up

some of the cabbages without tomatoes, I don't want to run out of

cabbage during soup season. So this year I'm experimenting

with time-lapse soup.

What's time-lapse

soup? It's simple --- I process each ingredient when it's on

hand, freeze it, then thaw out various bits to compile into soup

later. For example, I had more chicken carcasses this winter

than I needed right away, so I made broth out of the bones and

froze that. Now I'm thawing the chicken broth and using it

with cabbages, potato onions, parsley, and the end of last year's

garlic to make a denser stock. When the tomatoes come in,

I'm thinking I'll just turn them into paste, then in the winter

I'll thaw containers of paste, stock, green beans, and sweet corn,

add in some carrots, and make my soup that way.

The biggest flaw in

this plan is that I froze the initial broth, thawed it, then froze

it again with vegetables added. I had assumed that

refreezing was forbidden, but the internet explained that the

trouble with refreezing is that the freezer doesn't kill germs,

just puts them on hold. So the germs can multiply during the

thawing process, sit in the refrozen food, then multiply again

during the second thaw, resulting in high microorganism

populations and food that's a bit dicey. Luckily, the

intermediate boiling step sets the clock back, so my refreezing

shouldn't be a problem.

The jury's still out

on whether the winter-compiled soup will taste as good as a soup

made all at once during the summer months. I guess we'll

have to wait and see....

These new heavy duty tie

downs were easy to install in a few minutes.

I was going to use an eye

bolt, but these looked better suited for ratchet straps.

You get a package of four for

5 dollars and they're rated at 400 pounds.

If you aren't buying

your apples from a store and are instead keeping them in a root

cellar, your storage apples are going to give out by February or

so, leaving you with a hankering for crisp pomes in early

summer. The first apples might ripen up as late as July (or

even August) if you live in New England (or have a particularly

cool, rainy year like this one), but around here they're often

called "June apples" and tend to come on in late June. June

apples have a less intense flavor than later apples and they tend

to keep only a few days once they're ripe, so you wouldn't want to

plan a whole orchard around them, but one or two trees in your

garden are a summer treat.

Yellow Transparent is

the standby June apple in our area, and we've got a dwarf in our high-density planting and a

semi-dwarf in the forest garden. Thursday, Mark and I tasted

the first ripe sample (from the high-density planting) and gave it

top marks. Yellow Transparent (also known as White

Transparent, Russian Transparent, and Grand Sultan) wouldn't stand

up against really flavorful fall apples, but it beats the kind you

get in the store at this time of year and makes an excellent sauce

and pie. The trick with Yellow Transparent is to wait until

the flesh turns very yellow-green, and then to pick the fruit

right away before it gets mealy.

Tim Hensley, the source of several of our apples, posted the embedded youtube video this week

to highlight four other early apples he recommends (along with the

Yellow Transparent, which is the most popular and largest).

Henry Clay (a very small, ribbed apple introduced by Starks Bros.)

won his taste test, although the Red Astrachan was also noted to

be richly flavored. Lodi is an offspring of Yellow

Transparent that is more resistant to fire blight, but Hensley

notes that most people prefer the taste and texture of the parent

apple. Finally, Early Harvest is the very earliest apple he

reviewed, with apples sometimes ripening as soon as June 1, and

being sweeter than the other early apples.

We may try another

early apple in our high density planting next year since it looks

like the Pristine (a new, hybrid early apple) can't take the fungi

in our climate. The trick will be determining which of these

early apples is as disease resistant as

the Early Transparent, which seems to thrive despite our cedar

apple rust and general dampness.

Is there a preferred early-apple variety in your neck of the

woods? When do the first apples near you ripen? I'd be

curious to hear if Yellow Transparent is a standby in other areas,

or just around here.

Our first silk

worm moth showed up this

week!

There will be no flight for

these wings due to generations of domestic breeding.

No food or drink either. The

only job this moth has to do is hope one of the other cocoons changes

into a moth and ask her out on a date.

I reviewed Sharon Astyk's book Depletion

and Abundance a

couple of years ago, and since then I've fallen a bit out of love

with her blog. This often happens to me when a blogger

becomes repetitive, rehashing the same information over and over

--- it's interesting the first time, but not thereafter.

Still, I thought it was worth a shot to read her newest book, Making

Home.

I reviewed Sharon Astyk's book Depletion

and Abundance a

couple of years ago, and since then I've fallen a bit out of love

with her blog. This often happens to me when a blogger

becomes repetitive, rehashing the same information over and over

--- it's interesting the first time, but not thereafter.

Still, I thought it was worth a shot to read her newest book, Making

Home.

Astyk's thesis is

that Peak Oil will result in a very different world from the one

we now know. The book revolves around the idea of adapting

in place --- choosing a spot where you want to put down roots,

then making changes immediately so you won't be so hard hit when

the consequences of Peak Oil begin to be felt more widely.

As you might expect, the book gets a bit Doomy, especially in the

second half, but if you don't mind wading through that, you'll

find some handy information on emergency preparedness and

homesteading, especially from a social perspective.

On the other hand,

much of the information would be hard for us to put into

practice. Astyk is part of a relatively tightly-knit Jewish

community, and she and her husband have four kids plus an

ever-shifting number of foster kids. If you don't have a

faith-based community to fall back on, and don't have children,

you might as well skip about a third of the book and likely won't

find any community-building information that will appeal to you.

On the other hand,

Astyk's housing advice is more spot-on from our Trailersteading perspective. When

she and her husband were house-hunting, Astyk considered moving

into an Amish-built house (with the lack of electricity and other

facilities that you'd expect). She felt (as I do) that it's

much easier to start with nothing and slowly built more

sustainable workarounds than to move into a modern American house

and try to go backward. Her husband rebelled against the

Amish house, but they both seem content with living in what Astyk

calls a "working home" instead of a "show home," one that produces

rather than consumes. "[American] standards of cleanliness

and perfection can be so high," she wrote, "precisely because

homes are expensive spaces in which we do not ordinarily live."

On the other hand,

Astyk's housing advice is more spot-on from our Trailersteading perspective. When

she and her husband were house-hunting, Astyk considered moving

into an Amish-built house (with the lack of electricity and other

facilities that you'd expect). She felt (as I do) that it's

much easier to start with nothing and slowly built more

sustainable workarounds than to move into a modern American house

and try to go backward. Her husband rebelled against the

Amish house, but they both seem content with living in what Astyk

calls a "working home" instead of a "show home," one that produces

rather than consumes. "[American] standards of cleanliness

and perfection can be so high," she wrote, "precisely because

homes are expensive spaces in which we do not ordinarily live."

Astyk's take on

finances was also interesting. Of course, she recommended

that you prioritize getting out of debt, hypothesizing that debt

will be harder to deal with in the future than it is now.

But what if you have money to invest

for retirement?

Astyk believes that gold and silver will actually lose value, and

she (not entirely tongue-in-cheek) recommends investing in

alcohol, prescription sedatives, porn, and escapist videos

instead. More seriously, she recommends that we try not to

look at money as the only means to an end, and to focus on the end

itself. What will we need in the future, and what can we

spend time or money on now to prepare for that?

In the end, I felt Making Home was a

thought-provoking read, but I was thrown off by the internetisms

that popped up (smileys in a print book?) and by the word-for-word

reprints of articles I'd already seen on her blog. I'm also

a bit leery of the whole premise of the book --- yes, I believe in

Peak Oil, but I don't really believe we can predict what the

future looks like, and I also don't like the idea of planning your

life out of fear. Why not focus on being more sustainable

and self-sufficient for the joys it brings now, rather than

because it may or may not make your future easier than your

neighbors'? Despite my complaints, though, the book is well

worth a read, and is light enough to make fast summer reading.

We recently upgraded our TC1840H

garden wagon with a Sandusky utility wagon.

It's a little heavier duty

but about the same size. Cost was just under 150 with shipping.

Some of the reviews talk

about it being too heavy to pull, but it seems fine to us. Our helper

Dillon had no problem pulling it by himself loaded with firewood on Friday.

A little over a year ago, I

posted about my brother Joey's Kickstarter project to fund his free

software development project. I explained that, even though

git-annex isn't all that homesteading related, Joey's hard work in

the free software community is what keeps the backend of this blog

afloat.

A little over a year ago, I

posted about my brother Joey's Kickstarter project to fund his free

software development project. I explained that, even though

git-annex isn't all that homesteading related, Joey's hard work in

the free software community is what keeps the backend of this blog

afloat.

Completely unrelated

to my blog post, Joey's Kickstarter was funded in the first day,

and he went on to rake in enough cash to pay his (very basic)

living expenses for a full year of coding. Everyone who

donated got their money's worth and much more. My only

complaint is that Joey hasn't been over to visit nearly enough in

the last year because he's been burning the midnight oil coding,

paying himself roughly minimum wage from the Kickstarter

funds. And the results have been helping scores of people,

like Joe who wrote in to say:

At long last, the

Kickstarter money ran out, but Joey's project keeps attracting new

users with new needs. So he's

launching a second-generation campaign, with the tiny goal of

$3,000 to fund three more months of coding. If all of Walden

Effect's loyal readers donate at the virtual hug level (a mere

$5), we could fund Joey for a year and a half. What do you

say we help him reach his goal in less than 24 hours again?

A week ago, I

posted about how this abnormally-wet summer has turned our peach

trees into a breeding ground for brown rot, and why

I don't want to use a fungicide to combat the infection. I decided to try

two different methods of getting edible peaches despite the rot

--- picking some when they were ripe enough to finish ripening

inside, and leaving others on the tree but plucking off any fruits

that came down with the disease.

The second method was

a big loser --- the tree-ripened fruits tended to start rotting

when they were still apple-hard, and my secondary experiment of

cutting out the bad spots and letting the peaches ripen in the

fridge was a total failure. On the other hand, plucking

beautiful peaches off the tree and ripening them inside worked

well, producing fruits at least as tasty as the best I've found at

roadside stands and produce patches. So, this week, I'm

taking a preemptive approach and picking all of the peaches that

are old enough to ripen inside right away.

How can you tell if a

peach has ripened enough on the tree to produce luscious fruit

inside? The trick is to ignore the red color (which tells

you how much sun the peach got, not how ripe it is) and to focus

on the yellowish ground color. If the ground color is

yellow-orange, your peach is ready...

...but if the ground

is a yellow-green, the fruit needs more days on the tree.

The internet suggests

several different ways to ripen peaches inside, ranging from paper

bags to cloth coverings. I've actually had good luck just

setting them on a counter or in a fruit basket. (You can see

that not all of my cabbages have yet made their way into time-lapse

soup.)

Using this method, I suspect we'll end up with a pretty good crop

of peaches this year, despite the rain.

In the meantime,

summer does appear to be arriving at long last. The first

tomato started blushing Saturday, and the dog-day cicadas are

finally making a spotty start on their mating calls. We

enjoyed two or three rainless days last week, and hope for even

more this week. Wish us sun!

Despite getting carried away and finishing

up Mollison's book before moving on with Will

Hooker's video course, I didn't completely give up on the latter. Over

the last few weeks, I've worked my way through lectures 6, 7, and

8, along with the corresponding reading material about

permaculture as a design process, about patterns, and about

starting a vegetable garden.

Despite getting carried away and finishing

up Mollison's book before moving on with Will

Hooker's video course, I didn't completely give up on the latter. Over

the last few weeks, I've worked my way through lectures 6, 7, and

8, along with the corresponding reading material about

permaculture as a design process, about patterns, and about

starting a vegetable garden.

All three lectures

were pretty basic, and lecture 7, especially didn't contain much

of value. (I felt Will Hooker got a bit caught up in what I

consider New Age math.) On the other hand, gems jumped out

at me from the other two videos.

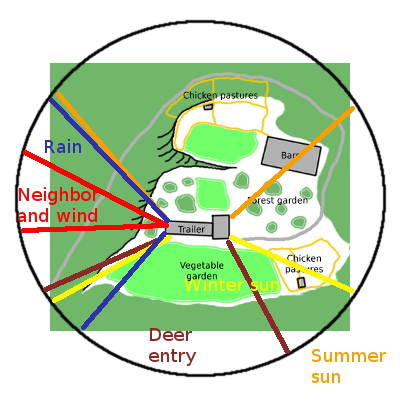

In addition to the

sun angle information that I'm going to devote a later post to, my

favorite part of lecture 6 was the notion of beginning the design

process with a sector analysis. The image at the top of this

post charts where forces of nature (and other elements beyond our

control) enter the farm. Although we already know our farm

well enough that we didn't receive any new information from the

sector analysis, those of you new an area might use the

information in a sector analysis to conclude you shouldn't plant

your fruit trees where they'll block the winter sun, that you should plant a dense barrier

where the wind comes gusting in off the prairie, and that you

might consider either making an edible garden where the neighbor's

children encroach, or keeping them out with thorny bushes

(depending on how you feel about the kids in question).

Shifting gears, Lecture 8

contained a good introduction to permaculture gardening techniques

--- I recommend that video for beginners. I enjoyed Hooker's

reiteration of the admonition to start gardening wherever you are,

even if you're renting; your first garden will be far from

perfect, so you might as well begin the trial and error process

now rather than putting it off until you have the perfect

plot. He also scavenges

biomass just

like I do, and has an excellent piece of advice there --- steer

clear of bags of clippings and leaves from beautiful lawns, since

those are more likely to be dosed in herbicides.

Shifting gears, Lecture 8

contained a good introduction to permaculture gardening techniques

--- I recommend that video for beginners. I enjoyed Hooker's

reiteration of the admonition to start gardening wherever you are,

even if you're renting; your first garden will be far from

perfect, so you might as well begin the trial and error process

now rather than putting it off until you have the perfect

plot. He also scavenges

biomass just

like I do, and has an excellent piece of advice there --- steer

clear of bags of clippings and leaves from beautiful lawns, since

those are more likely to be dosed in herbicides.

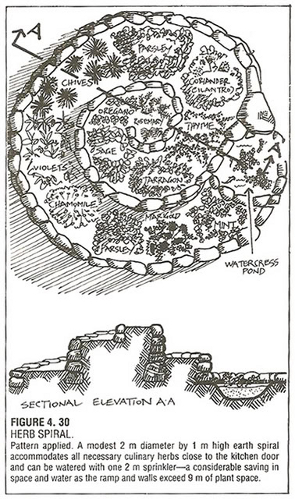

As usual, I had mixed

feelings about the reading in Gaia's Garden. Even though I tried out

keyhole beds when I was new to permaculture, I believe both keyhole

beds and herb spirals are trendy techniques that create much

more work than old-school straight lines and rectangles. On

the other hand, I do like the concept of designing from patterns

to details, looking at the flows and patterns already present in

your landscape, and optimizing them. For example, Hemenway

explains that a tree's branch design is a useful pattern to mimic

in drip irrigation systems, and that people tend to flow like

water.

I've got a bit more

to say about this trio of lectures in later posts, but for now,

here's the reading material for the next set of lectures:

- Chapters 2 and 4 in Building

Soils for Better Crops. (Free download.)

- NRCS

Soil Biology Primer. (Read for free online.)

- Cornell

Soil Health Assessment Manual. (Free download.)

- Gaia's

Garden chapter 4 (soil)

- Introduction to Permaculture chapter 5 (home garden)

If you've been

watching along with me, I'd be curious to hear if different parts

of these lectures caught your interest than caught mine.

The worst part of our

driveway is a section that turns and one of the ruts is deeper than the

other creating a situation where it causes the trailer to almost tip

over.

Until I fix that part of the

driveway the bucket hauler trailer limit for straw bales will be

3...with a couple of bales bungee strapped to the ATV.

Some of the herbicides in the aminopyralid group can be long lasting and can survive the transit thru a horses GI tract. They're great for managing a horse pasture because they are long-lasting, but the resulting manure is supposed to be kept out of the compost heap, as the warning on the containers states. Some compost sold to gardeners has been know to contain these chemicals. I'd like to think they made it there inadvertently rather than thru motives of greed.

That's an excellent

question, and the answer will depend on how livestock are

kept near you. In our area, hay is a very low-impact crop

--- people simply let whatever's there grow up, mow it once,

twice, or thrice a year, and that's that. They do sometimes

spread chemical fertilizers on the ground to make up for the

nutrients they take away while haying, but I'm willing to put up

with the possible lack of micronutrients that might result once

the hay passes through a horse and ends up in my garden. I'd

be much more leery of the hay if it was raised in a different

manner, but I don't expect people in our economically depressed

region to have enough funding to improve their hayfields by

plowing and replanting any time soon.

While herbicide use on the pasture is slightly more likely in our

area, it also seems to be far from widespread. Most of the

surrounding pastures are what's known as "unimproved," meaning

that they're produced by mowing whatever's there repeatedly until

only grasses and low weeds remain. If our manure-producers

were using herbicides on their pastures, we'd likely know right

away since our crops would fail, then we'd find another source of

manure.

The larger problem

with horse manure is pharmaceuticals that might have been fed to

the horses, specifically dewormers. A couple of years ago,

there were a spate of articles about home gardeners who lost crops

due to using compost that was based on horse manure with dewormers

in it. This is always a gamble, although the longer you age

the manure between horse and garden, the lower your risk is.

I've never seen any issues in our own garden, so I suspect if the

relevant horse owners use dewormers, their use is minimal enough

that the chemicals break down quickly in our biologically-rich

soil.

Although not a

chemical issue, everyone will have to deal with the problem of

weed seeds in their horse manure. In a perfect world, we'd

compost the manure well enough to kill the seeds, but in this real

world, I just hand-pull and mulch, which deals with any weeds that

might otherwise pop up.

In the end, I'm not

an organic purist from a labeling standpoint --- I'm sure the

horse manure we use wouldn't fly if we wanted to jump through the

hoops to sell our produce as organic. We're more interested

in our own health and the quality of our soil than in the word

"organic," though, and the horse manure we use seems to be the

best option there, given our location.

One of the reasons I'm plugging along with Will

Hooker's permaculture videos even though I know most of the

information is that I want to fill in any obvious gaps in my

scattered, homeschooled education. So I was thrilled to have

sun angles finally explained to me in a manner I could understand

in lecture 6.

One of the reasons I'm plugging along with Will

Hooker's permaculture videos even though I know most of the

information is that I want to fill in any obvious gaps in my

scattered, homeschooled education. So I was thrilled to have

sun angles finally explained to me in a manner I could understand

in lecture 6.

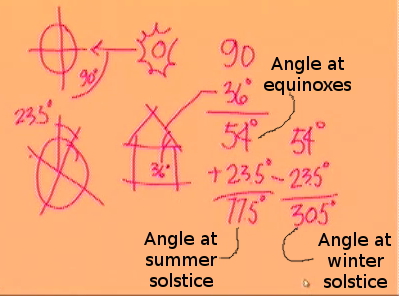

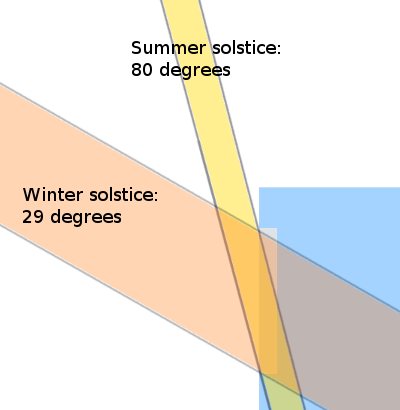

I've posted

previously about the

science behind sun angles, but the math has always eluded me. Luckily,

Hooker broke it down into simple arithmetic. All you have to

do to find the height of the sun above the horizon at the

equinoxes is to subtract your latitude from 90 degrees --- so, the

equinox sun is 54 degrees above the horizon at a latitude of 36

degrees. Since the sun angle at the equinox splits the

difference between summer and winter sun angles, people often use

this figure to calculate the tilt of their solar panels. If

you want to have the sun's rays striking a solar panel

perpendicularly at the equinox, just tilt the panel the same

number of degrees as your latitude --- 36.8 degrees here. If

you want a bit more efficiency from your panels in the winter,

tilt the panel a bit steeper; for a bit more energy in the summer,

tilt the panel more shallowly.

In order to figure out the sun angle at the

summer and winter solstice, you need to understand that the earth

is tilted at an angle of 23.5 degrees. (This is what gives

us seasons.) At the summer solstice, you add the earth's

tilt to the equinox's angle --- so Will Hooker's sun angle at the

summer solstice is 77.5 degrees (and ours is 76.7). At the

winter solstice, you subtract the tilt of the earth, so for us the

sun angle at the winter solstice is 29.7 degrees. These two

sun angles are what you need to determine

overhang depths for passive-solar structures.

In order to figure out the sun angle at the

summer and winter solstice, you need to understand that the earth

is tilted at an angle of 23.5 degrees. (This is what gives

us seasons.) At the summer solstice, you add the earth's

tilt to the equinox's angle --- so Will Hooker's sun angle at the

summer solstice is 77.5 degrees (and ours is 76.7). At the

winter solstice, you subtract the tilt of the earth, so for us the

sun angle at the winter solstice is 29.7 degrees. These two

sun angles are what you need to determine

overhang depths for passive-solar structures.

This information is just what we needed as we plan

more energy-saving trailer retrofits!

This drill powered

plucker is still our preferred tool for getting feathers off

chickens.

We retired 6 chickens today

which equals about a half hour of time saved according to last year's

estimations.

My goal is always to get all of our firewood

into the shed to dry by early June...but that's never

happened. This year, the new

pasture project

resulted in enough firewood for the winter, but we were too busy

to move most of that wood to the shed in a timely manner.

Luckily, Dillon was kind enough to come

lug firewood for two mornings and get it all under cover.

My goal is always to get all of our firewood

into the shed to dry by early June...but that's never

happened. This year, the new

pasture project

resulted in enough firewood for the winter, but we were too busy

to move most of that wood to the shed in a timely manner.

Luckily, Dillon was kind enough to come

lug firewood for two mornings and get it all under cover.

Last year, I stacked

the shed a little differently. I separated out the harder

woods to one side  and the softer, kindling-woods to the other,

which made it easy to manage my burns. But that meant I had

to leave an aisle down the middle, which took up a lot of

space. Since we have a vast array of different kinds of wood

this year, I let Dillon stack it all together, with the result

that I think we currently have as much wood in the shed as last

year, but have room for more if we track some down.

and the softer, kindling-woods to the other,

which made it easy to manage my burns. But that meant I had

to leave an aisle down the middle, which took up a lot of

space. Since we have a vast array of different kinds of wood

this year, I let Dillon stack it all together, with the result

that I think we currently have as much wood in the shed as last

year, but have room for more if we track some down.

Burning prolifically

like I did last winter, I figure one row of wood will last through

a warm month (like November or March), while the cold months take

up two rows of wood. It looks like we've got a bit of extra

wiggle room already, so maybe we won't run

out in March.

As I've typed before, every year gets a little better here on the

farm!

One of the assignments

associated with Will

Hooker's permaculture course is to watch The

End of Suburbia,

a documentary assessing the future of American suburbs post Peak

Oil. Since Sharon Astyk's Making Home covered the same

hypothetical (but with different imagined results), I thought it

would be interesting for me to sum up the differences between each

philosopher's take on the issue.

James Howard Kunstler

(and other speakers) spend the majority of the video explaining

how suburbs came about. I won't rehash all of this

information, but the major factors leading to the rise of suburbia

seem to have been the ubiquity of the automobile, cheap oil

allowing us to drive everywhere we want to go, and a

post-World-War-II push for non-urban housing. Kunstler

suspects that transportation will become much more expensive in

the future, making suburbs unsustainable as they're currently laid

out. His solution is to relocalize our suburbs so basic

needs can be met within walking distance --- otherwise, he sees

the suburban experiment failing.

Sharon Astyk considered

the issue more broadly by looking at the impact of Peak Oil on the

three places you can live (cities, suburbia, and farms). She

believes that each area has a future, but that the future is

different for each one (and, in each, is different from the way we

live now).

Sharon Astyk considered

the issue more broadly by looking at the impact of Peak Oil on the

three places you can live (cities, suburbia, and farms). She

believes that each area has a future, but that the future is

different for each one (and, in each, is different from the way we

live now).

Astyk wrote that

rural areas will suffer in many of the ways they already do, only

more so. Jobs will become even scarcer, and transportation

costs will make it increasingly difficult to get from place to