archives for 06/2013

I

haven't been the only one having fun with grafting and rooting this

year --- two of our readers emailed this week with updates on

experiments of their own. Brian

wrote in to say that he ended up with accidentally-rooted fig cuttings

in his Tennessee garden:

I

haven't been the only one having fun with grafting and rooting this

year --- two of our readers emailed this week with updates on

experiments of their own. Brian

wrote in to say that he ended up with accidentally-rooted fig cuttings

in his Tennessee garden:

(I would have put an

exclamation point at least somewhere in that paragraph, so I'll add two

here for you to use as you see fit --- !!)

Brian also had quite

good success with his more intentional grafting and rooting efforts,

managing to salvage some very subpar cuttings I sent him. His

only real failure was trying to graft hardwood cuttings onto a peach

--- my understanding is that peaches are best budded in the summer, although I've

never tried it myself.

Meanwhile, you may recall Gary,

who is experimenting with propagating Illinois Everbearing mulberries. The cuttings that

callused for him didn't end up rooting, but he had much better luck

with grafting Illinois Everbearing onto wild red mulberries around his

farm. He wrote:

Meanwhile, you may recall Gary,

who is experimenting with propagating Illinois Everbearing mulberries. The cuttings that

callused for him didn't end up rooting, but he had much better luck

with grafting Illinois Everbearing onto wild red mulberries around his

farm. He wrote:

I owe you updates on my

own rooting and grafting experiments (which have been a mixed bag, but

with some great successes). That will have to wait for another

post, though. In the meantime, I hope you'll be inspired by these

two success stories to give home-propagation of woody perennials a try.

In a perfect world the scrap

pieces from one star plate triangle wall should fit together for the

next triangle.

I think maybe Lucy carried

off one of the pieces from the second triangle, but instead of cutting

a new replacement piece we decided to overlap the ill fitting pieces.

The overlapping seems to make

the wall more secure and still looks acceptable.

I put off deciding

whether to buy another package

of bees until April,

which means that our bees only went in the mail Friday. With such

a late start ahead of them, I figured it wouldn't hurt to prime the

pump by giving the new hive a box of nearly-drawn comb, partially

filled with pollen and nectar.

It was time to nadir the old hive anyway, so I

killed two birds with one stone, lifting the top two boxes from that

hive to the side, replacing the bottom box with two empty boxes, then

adding the full boxes of brood back on top. In a perfect world, I

would have left the quilt and roof on during this procedure, but I was

working by myself and figured that I could cut corners (and weight) by

removing those two components. I left the sheet of burlap on the

top box, though, so I don't think the procedure messed with the Nestduftwarmebindung of the hive too much.

Weight of the two boxes of brood was just shy of too heavy for me

(maybe forty pounds? or perhaps thirty since the bulkiness was the real

hindrance?).

It was time to nadir the old hive anyway, so I

killed two birds with one stone, lifting the top two boxes from that

hive to the side, replacing the bottom box with two empty boxes, then

adding the full boxes of brood back on top. In a perfect world, I

would have left the quilt and roof on during this procedure, but I was

working by myself and figured that I could cut corners (and weight) by

removing those two components. I left the sheet of burlap on the

top box, though, so I don't think the procedure messed with the Nestduftwarmebindung of the hive too much.

Weight of the two boxes of brood was just shy of too heavy for me

(maybe forty pounds? or perhaps thirty since the bulkiness was the real

hindrance?).

Over at the new hive spot, I

got to scratch my bee-photographing itch. That's one of the major

downsides of the Warre hive --- you're not supposed to mess with

individual frames, so you rarely get to see your bees in action.

Isn't that beautiful, straight comb drawn without

foundation?

Over at the new hive spot, I

got to scratch my bee-photographing itch. That's one of the major

downsides of the Warre hive --- you're not supposed to mess with

individual frames, so you rarely get to see your bees in action.

Isn't that beautiful, straight comb drawn without

foundation?

I didn't bother brushing

off the workers and drones who came along for the ride in the relocated

box, but I figure they'll go home tonight. Then I'll plug up the

door so they don't come back tomorrow and rob all that nectar right

back to their old hive.

The Skil drill press is still going strong with its new

return spring.

We tried using it on the StarPlate building, but ended up using the

electric hand powered one.

The issue was power.

Extension cords can only go so far before they lose some punch.

Perfectionism has

long been a character failing of mine. When other kids were

aiming for straight As in high school, I figured I should keep an

average of 98 and above --- 97s were a sign I needed to work

harder. I'm afraid I carried that need for 98% perfection

over to the homestead.

Years ago, Mark

helped me awaken to the fact that striving for perfection results

in missing the true joys of this imperfect life. But try as

I might, I only managed to make about a C- on pop quizzes in that

subject.

While reading and

watching introductory

permaculture materials over the last few weeks, though, I had an epiphany.

My main trouble is that I treat our entire homestead like zone 1,

with all the high upkeep that choice entails. (Okay, I treat

the house like zone 4, but that's neither here nor there.)

Two people can't maintain over

an acre in zone

1 conditions with hand tools and stay sane.

I need to think more

about how to plan certain portions of the farm as zones 2 and

above, but in the meantime, I decreased my stress considerably

with some stopgap measures. The broiler pastures are getting

severely overgrazed since the Starplate

coop is taking

longer than anticipated to finish, but moving at least one flock

into temporary pastures is easing pressure there. We've been

wanting to install drip irrigation for the blueberries and

mini-apples, but it occurred to me that rearranging my sprinklers a bit would allow quick

coverage in the meantime. And I decided most of the woody

perennials are going to get a quick-and-dirty

kill mulch

rather than a real weeding job this month.

The result? I

got an A+ in noticing the sheer beauty and peace of the farm this

weekend. Creek-walking, bathing in the rain, reading while

watching chicks, mini-experiments with silkworms, lightning bugs

in the dark. That's why I moved to the farm, after all ---

I'd better enjoy it!

I've ordered a total of 8

mulching mower blades from Yard Parts Express.com. Most of the time the blade shows

up the next day through UPS. They really do earn the express part of

their name

I think the unique twist

shape of the blade is what helps to re-circulate the clippings back up

to be mulched, but it also makes it more sensitive to warping if you

hit the occasional stump.

We've almost got all the

stumps taken care of, but I might not choose a mulching mower

in the future due to this issue.

The harvest is upon

us! After a week of simply gorging on the fruits, the

strawberry harvest has grown beyond even my ability to consume

it. So I cleaned up the food

dehydrator and started the first gallon drying. I

figure we may need to do a load a day all week to keep up with the

bounty.

Meanwhile, the

Italian Softneck garlic (on the right) is ready

to dig. Music (on the left) and Silverwhite Silverskin are

slightly slower to mature and aren't quite ready to harvest yet.

I'm a bit

disappointed in the size of our garlic heads this year.

Unlike last year's XXL heads, these are only large. I

suspect the difference is the sawdust our horse manure source

started using as bedding last summer instead of straw ---

lower-nitrogen compost means smaller vegetables. On the

other hand, we always have far too much garlic, so this year we

simply won't give any away.

The curing

rack is back at work, drying up the Italian Softneck

garlic. These racks stayed busy nearly all of the warm

season last year, and I suspect they'll keep plugging away all

this summer too. Every year, things are just a little bit

easier!

67 bales of straw grown on

half an acre.

It went up from 4 to 5 dollars per bale plus 20

dollars for delivery.

Still a better deal than the

local feed store with the bonus that these bales are tighter.

Part of the reason we

had to wait

so long for our package of bees is that I wanted fancy bees

that had been raised without chemicals. Last year's

chemical-free bees have done very well for us, and, granted, most

packages do well the first year, but we have high hopes that

spending a bit more on natural bees will make them more likely to

survive in the long run without chemicals.

This package of bees was even more pricey

than last

year's --- $169

--- but it's also nearly local and thus more likely to go the

distance in our neck of the woods. We purchased the bees

from AzureB in Maryland, but the

bees actually came from the mountains of Tennessee.

This package of bees was even more pricey

than last

year's --- $169

--- but it's also nearly local and thus more likely to go the

distance in our neck of the woods. We purchased the bees

from AzureB in Maryland, but the

bees actually came from the mountains of Tennessee.

Our new colony is a

cross of Carniolan and Russian, raised on small-cell, natural

comb. They're bred to be hygenic, meaning the bees spend a

lot of time grooming off mites. By skipping the miticides

and breeding the survivor bees, the company is able to raise bees

that are much more likely to survive without chemical

intervention.

You can read last

year's lunchtime series if you're interested in the nuts and bolts

of our package installation into a Warre hive. We'll be feeding

our newest colony for a while, but I suspect will be able to slack

off in a week or two when the basswood buds unfurl into

nectar-laden flowers.

The Harbor Freight people

sent the missing

hardware pretty fast, but

our priorities shifted a bit and the new ATV

trailer project got moved

down the list.

Seven full buckets of moist

and aged horse manure is really too much weight for this lawn

trailer, but the lazy side of me didn't want to do an extra trip.

Anna says these 21 buckets

should be enough for this week and with any luck we'll get the new

trailer finished and modified to carry either 9 or 12 at a time for

next week.

Usually, we have

three strawberry

varieties in

the garden --- early, midseason, and late. I hated the late

variety we tried last year (Allstar), though, so I ripped it out

and didn't replace it with a new late variety (Sparkle) until this

spring. Instead, I just increased my plantings of the early

and midseason varieties.

That sounded like a

good idea at the time, but then the peak harvest came on...all at

once. Monday,

I filled the dehydrator with two gallons of fruits and we ate

perhaps another half gallon. Tuesday was the same, but it became clear

the strawberries needed to get picked even faster. So I

asked Mark to get me low-sugar pectin at the grocery store,

invited one of our young

helpers over as

a picker, and planned for Wednesday to be strawberry day.

Before I regale you with what we did with

Wednesday's five gallons of strawberries, I should give you the

bad news. This spring's cool, wet conditions were perfect

for fungal spread, and the many of the Honeoye plants came down

with strawberry leaf spot (Mycosphaerella

Before I regale you with what we did with

Wednesday's five gallons of strawberries, I should give you the

bad news. This spring's cool, wet conditions were perfect

for fungal spread, and the many of the Honeoye plants came down

with strawberry leaf spot (Mycosphaerella

fragariae). This fungus

causes a decline in vigor, which means the fruits aren't as sweet

and are more prone to rotting. My solution is to cut out the

rotten bits, add more honey than usual when making fruit leather,

and mix in the virtually-untouched and still-very-sweet Ozark

Beauties. (Think of this as like making cider --- a

combination of varieties leads to a fuller-bodied taste.)

Leaf spot aside,

there were still plenty of fruits to preserve for the

winter. I

filled the dehydrator once, put aside enough to fill it again before bed, then

moved on to a double recipe of strawberry freezer

jam.

We've already

preserved more strawberries this week than all of last year, and I

figure we'll need at least one more massive strawberry day to use

up the rest.

Even the chickens

were happy. With all of the rotten strawberries and tops, I

had to split a gallon of waste between three flocks to ensure it

would all get eaten. "No problem!" our Leghorn pullets

declared. "We can clean that up lickety-split!"

I've got the base of the new Haul Master ATV trailer together today.

The current plan is to make

it 3 inches wider on each side by attaching wood which will also be

used to fabricate the walls.

These modifications should

allow for 9 five gallon buckets to fit snugly inside and maybe by

extending the front and back I could squeeze the total to 12.

Our package

of bees was in

the mail longer than expected because they got stuck at the post

office over the weekend. The can of syrup still had food in

it when they arrived four days later, but the attendant bees had

all died. (Luckily, the queen was okay.) And there was

even a palm-sized piece of comb hanging from the top of the box!

Our package

of bees was in

the mail longer than expected because they got stuck at the post

office over the weekend. The can of syrup still had food in

it when they arrived four days later, but the attendant bees had

all died. (Luckily, the queen was okay.) And there was

even a palm-sized piece of comb hanging from the top of the box!

Two days after

installing the package, I opened the hive back up to take the

queen cage out. I must have done a better job than usual

poking a hole in the candy end, because our matriarch had freed

herself and was already lost in the mass of workers and drones.

The photo above is a

shot up through the bottom of the hive. It's tough to tell

if our new package of bees has done much because I gave

them a box of partially-drawn comb to prime the pump, but they do look busy

in there. Now I'll just feed and nadir as necessary for the

rest of the summer --- a hive of bees is definitely a zone 3

endeavor.

Got the ATV

lawn trailer base

together today.

Seeing it with the wheels

helped me to decide that it should be able to handle 12 five gallon

buckets.

Being able to haul a dozen

buckets makes me want to increase the truck bed bucket limit from 21 to

24. I'm pretty sure I could stack a few buckets near the cab and

ratchet strap them down.

I found this marbled

salamander under the mulch while planting Thursday. In the

next few minutes, I also turned up a toad and a ringneck snake,

along with one of those wolf spiders  with her tiny babies all clinging to her

back.

with her tiny babies all clinging to her

back.

Earlier in the week,

a large snapping turtle crawled up through the gate and laid her

eggs in the driveway, and a minuscule blue-gray gnatcatcher has

been hanging out in the garden while we eat our dinners.

Meanwhile, Mark was careful enough to leave this song sparrow nest

behind while cutting rye and weeds in the old house area.

Quite a wild and

wonderful week in (south)west Virginia!

I hate the dumping feature on

lawn trailers.

Maybe it works okay for

people with "lawns"...but our driveway has enough bumps to trigger the

dump feature while moving, which is why I modified ours to never dump.

It was easy to drill a hole

where the dump lever slides in and out. A short bolt with a couple of

washers and a nut keeps it in no-dump mode for good.

After the astonishing, five-gallon

day, our

strawberry harvest began to decline. Now we're down to just

a gallon or two a day, but that's okay because I'm sated...and the

red raspberries are starting to ripen.

After the astonishing, five-gallon

day, our

strawberry harvest began to decline. Now we're down to just

a gallon or two a day, but that's okay because I'm sated...and the

red raspberries are starting to ripen.

Similarly, the kale

buds have nearly all turned into flowers, removing raab from the

menu, but broccoli is taking their place. The broccoli heads

(like this

year's garlic)

are smaller than average, but the cold weather has also resulted

in very few cabbage worms, so I'm happy. Other vegetables

we're currently eating in profusion include snap peas and lettuce.

The whole garden is starting to look like the

coming-attractions section of a homesteading movie. The

first tomato flowers don't mean much since those fruits take a

long time to ripen, but cucumber and bean flowers mean we could be

enjoying those two vegetables within a week or two. And

don't get me started on the peaches, apples, gooseberries, and

blueberries studding the trees and bushes or I'll go back out with

the camera and make this post far too long.

The whole garden is starting to look like the

coming-attractions section of a homesteading movie. The

first tomato flowers don't mean much since those fruits take a

long time to ripen, but cucumber and bean flowers mean we could be

enjoying those two vegetables within a week or two. And

don't get me started on the peaches, apples, gooseberries, and

blueberries studding the trees and bushes or I'll go back out with

the camera and make this post far too long.

What's ripe (or ripening) in your garden?

I sent back the leaky

chest waders and tested

out the new neoprene hip waders on Friday.

The boot part is more solid

than other waders I've tried... more like a Muck boot.

I decided the chest waders

were too heavy and if the water is higher than my hips I don't need to

be crossing the creek that day anyway.

Since I

last posted here about our silkworms, they have grown...a lot. The more serious

side of our foray into insect farming is playing out over on our chicken blog,

where recent posts have included:

...and I've got a lot

more tidbits coming up on topics like how to kill two-hundred

silkworms in one fell swoop (oops) and which types of leaves the

caterpillars prefer.

However, I thought

even those of you uninterested in the nuts and bolts of silkworm

culture might like to hear how they eat mulberry leaves using the

typewriter method --- nibble in a semi-circle until you come to

the end of the line, then skip back to the beginning to start

again. I also tried out a few silkworms on our

broody hen's flock and the chicks deemed the caterpillars

"wicked!" (Or at least I'm assuming the speed with which

they gulped those silkworms down was an implied superlative.)

Finally, if you don't

care for bugs, even combined with cute chicks, here's a song

sparrow in the garden to brighten your Monday morning instead.

As I delved into the next

round of permaculture

lectures, it

became clear that the professor had included some topics out of

order to fit his field-trip schedule. Since we don't have

that restriction, I recommend you skip around with me and watch

lectures 5, 11, and 12 as a set before moving on to lecture 6.

As I delved into the next

round of permaculture

lectures, it

became clear that the professor had included some topics out of

order to fit his field-trip schedule. Since we don't have

that restriction, I recommend you skip around with me and watch

lectures 5, 11, and 12 as a set before moving on to lecture 6.

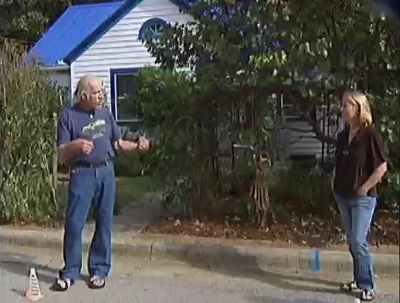

Lecture 11 should

really have gone along with the slideshow

tour of the professor's urban homestead since this later

"lecture" is a field trip to the professor's house. You'll

end up seeing some of the same information over again, but lecture

11 adds in Hooker's wife's perspective, and you also learn more

specifics about variety selection (Black Mission is his favorite

fig) and design. (Keep in mind that varieties that work well

for him are more likely to suit your homestead if you live in an

urban environment near Raleigh, North Carolina, which is in zone

7b. Some of his favorites have failed miserably for us here

in rural zone 6.)

My favorite part of

the tour was the twenty minutes Hooker spent in the chicken run

(starting around an hour and four minutes into the video).

I'm still working on the best way to match chickens up with

compost, and I liked his method of keeping an open-topped compost

bin in the chicken run and just letting the chickens hop in and

eat what they want. Although pastures provide more food if

you have the space, Hooker's mulched yard also  looked very effective for

the urban environment. He provides about 10 square feet per

bird, keeps the whole area mulched with straw, then rakes out the

mulch every two to four weeks to use on the garden. Finally,

he has planted peaches, figs, and kiwis in the run, protecting the

last with 3-foot lengths of black PVC pipe, which keeps chickens

from eating the tender vines and also protects their bases from

late freezes.

looked very effective for

the urban environment. He provides about 10 square feet per

bird, keeps the whole area mulched with straw, then rakes out the

mulch every two to four weeks to use on the garden. Finally,

he has planted peaches, figs, and kiwis in the run, protecting the

last with 3-foot lengths of black PVC pipe, which keeps chickens

from eating the tender vines and also protects their bases from

late freezes.

Stay tuned for my

next post, which will cover lectures 5 and 12, and also the

reading for this section of the course:

Took the ATV in for some repair work today.

The brakes stopped working

and I couldn't determine what's wrong.

Figured out it will drive off

a trailer this size with no problem, but ramps are needed to get it on.

We used a couple of 2x6's, but might think about getting some proper

ramps in the future so we can drive it up into the bed of the truck and

transport it without the trailer.

This light rain was a constant in Aug. '75, when I had morning-sickness and was trying to sort thru curing onions, at the Old House at the Store. A year or 2 earlier, still in that house, it rained all summer, and the bushes expanded, the trees drooped, and Geoff Greene called it "the Mendoty Blues"! Good weather for ducks....

Rain has been a near

constant on the farm so far this year, with no end in sight.

This is our seventh year here, and most have been moderate or "dry"

except for this year and the summer of 2009. (I put "dry" in

quotes because even our driest years are pretty wet, with our

average rainfall being about an inch per week for all twelve

months.)

So I'm taking evasive

action. A few of the peach branches are drooping down toward

the ground under the weight of the developing fruits. I

probably should have thinned harder, but as a stopgap measure, I'm

propping the low limbs up on fence posts to keep them out of the

three-foot fungal zone right above the ground.

And, of course, I'm pruning

and training our tomatoes hard. The toughest part this year has been

finding a time when the leaves are dry enough to touch!

Some of the

strawberries are rotting in the wet, but there are so many that

even losing 20% barely makes a dent in the harvest. I've

taken to picking the fruits slightly unripe, though, to keep decay

at bay.

What kind of

non-chemical fungal-prevention techniques do you use?

The theme of Will

Hooker's lecture

5 is biomes and trees, and even though I have a poster of the

former on my bedroom wall and adore the latter, the lecture bored

me stiff. If you're going to skip one lecture, it should be

this one. Hooker's take-home message, though, is very valid

--- if you're not settled in one spot yet, be sure to learn about

the ecosystem you move into and tweak your permaculture plans

accordingly.

The theme of Will

Hooker's lecture

5 is biomes and trees, and even though I have a poster of the

former on my bedroom wall and adore the latter, the lecture bored

me stiff. If you're going to skip one lecture, it should be

this one. Hooker's take-home message, though, is very valid

--- if you're not settled in one spot yet, be sure to learn about

the ecosystem you move into and tweak your permaculture plans

accordingly.

On the other hand,

the associated readings were riveting, so that's what I'll write

about today. As you'll recall, both Toby Hemenway and Bill

Mollison included a chapter on forest gardening in their

introductory texts, and it's fascinating to compare and contrast

their recommendations.

Both gurus recommend

interplanting trees, shrubs, and herbs, but Mollison focuses in on

including lots of legumes

to make your forest self-fertilizing, and he also writes about using animals

in your orchards.

"Should you be so unfortunate as to inherit a monocultural

orchard," he wrote, "add 3-4 hens, a pig, and 4-6 large leguminous

trees per 1000 square meters (1/4 acre), with many smaller

legumes." Mollison went on to recommend introducing pigs to

your orchard when the trees are three-to-seven years old, then

sheep and cattle at seven-to-twenty years.

Although both

authors wrote about cover crops and

kill

mulches, I preferred Hemenway's suggestions to kill mulch

zones 1 and 2, then use low-maintenance cover crops in zone 3.

(Specifically, Hemenway prefers a mixture of clover, annual rye,

yarrow, dill, fennel, and daikon radishes that only needs to be

mown once or twice a year.) Mollison adds that your orchard

for personal use should be considered zone 2, while any commercial

operation extends out into zone 3.

Although both

authors wrote about cover crops and

kill

mulches, I preferred Hemenway's suggestions to kill mulch

zones 1 and 2, then use low-maintenance cover crops in zone 3.

(Specifically, Hemenway prefers a mixture of clover, annual rye,

yarrow, dill, fennel, and daikon radishes that only needs to be

mown once or twice a year.) Mollison adds that your orchard

for personal use should be considered zone 2, while any commercial

operation extends out into zone 3.

My main

disappointment with both explanations of forest gardens is their

recommendation to include prolific understory herbs. In

fact, Mollison writes that broadleaf plants are much better around

the feet of young trees than grass is, but my own experience has

shown that anything interfering with the

root zone of young trees slows growth markedly when compared to a solid

mulch. Of course, my original soil is terrible, so those of

you with deep, well-drained loam might have better luck applying

these guru's wisdom without tweaking.

I decided to use 3/4 inch

treated plywood to extend the base of the new ATV

lawn trailer.

Thank you Roland for the

suggestion.

8X4 3/4 inch plywood costs 41

dollars and I figure this project will use about 40% of the sheet. The

guy at our local lumber store made the cuts for free to make

transporting it easier, but we'll have to wait until we get the ATV back to haul it the rest of the

way.

One of the first

things I learned to root was grapes, and thus we

set out quite a number of vines near the beginning of our time on

the farm. But we didn't have the cash to buy fancy varieties

then, so we got the cuttings from a friend who was raising grapes

conventionally (with lots of chemicals) to make wine. Since

I wasn't willing to dose our new vines, they came down with every

malady under the sun, and last year we completely ripped them

out.

Now we're selecting for disease resistance,

and also for seedlessness since Mark doesn't like grapes with

seeds. (To be honest, I prefer seedless grapes too, even

though I'm a pro at popping a tough-skin, seeded grape in my

mouth, masticating, then spitting out the seeds.) So far,

our young Mars Seedless grapes seem to be doing well in the first

department, but we won't know about fruiting for a year or two

more.

Now we're selecting for disease resistance,

and also for seedlessness since Mark doesn't like grapes with

seeds. (To be honest, I prefer seedless grapes too, even

though I'm a pro at popping a tough-skin, seeded grape in my

mouth, masticating, then spitting out the seeds.) So far,

our young Mars Seedless grapes seem to be doing well in the first

department, but we won't know about fruiting for a year or two

more.

This spring, Brian

sent me a bunch of cuttings from his plants, and the grapes are

rooting wonderfully. So we'll be adding Marquis, Reliance,

and Thomcord to our experimental planting this year too.

Check back in two to

four years for results on my disease-resistant, seedless grape

experiment. In the meantime, perhaps our readers would like

to chime in about which seedless grapes have done well in their

gardens without sprays?

Even though I'm

telling you to watch it out of order, lecture 12 seems to go along

with this section on trees

and forest gardening. The video consists of a field

trip to AJ Bullard's experimental orchard in Calypso, North

Carolina (zone 8). This seventy-plus-year-old man has been

experimenting with fruit tree varieties on his farm since 1967,

and distance learners like us really miss out by not getting to

taste all of the fruits being offered. We can, however, take

advantage of his wisdom to learn about varieties we might want to

try in our own gardens.

Even though I'm

telling you to watch it out of order, lecture 12 seems to go along

with this section on trees

and forest gardening. The video consists of a field

trip to AJ Bullard's experimental orchard in Calypso, North

Carolina (zone 8). This seventy-plus-year-old man has been

experimenting with fruit tree varieties on his farm since 1967,

and distance learners like us really miss out by not getting to

taste all of the fruits being offered. We can, however, take

advantage of his wisdom to learn about varieties we might want to

try in our own gardens.

Bullard tested 35

varieties of pears for dessert quality (flavor) and resistance to

fire-blight, and proclaimed Shin-li his favorite (although one of

his trees of this variety had moderate fire-blight damage).

An even more extensive fig planting resulted in the recommendation

of Celeste, Kadota, and King, while his favorite Asian persimmon

is Fuyu.

Mulberry stars

(which Bullard explained are his third-favorite type of fruit)

consist of Silk Hope and Pakistan alba. In fact, I

planted the former in my garden this past winter and am

still looking forward to tasting the fruits, although I'm

disappointed to learn in this video that the variety was named

after a town and actually produces leaves unpalatable to silkworms.

And, although Bullard's description of Pakistan alba sounds

fascinating, I recommend that readers outside his location take

the internet's advice and only plant this early-wakening mulberry

in coastal areas of zone 8, California, and Oregon, where late

frosts are seldom a problem.

Next up (in a week...or

more), Lecture 6 will return to basics with an emphasis on

design. The assignments to prepare for the lecture include:

- End of

Suburbia

- Gaia's Garden --- chapter 3

- Introduction to Permaculture --- the part of chapter 2 on design (although I'll probably just read the whole chapter), the part of chapter 3 on patterns (ditto), and pages 95 to 111 in chapter 5 (not sure what pages this is in my older edition)

I hope you'll join me as

we continue to work through this free permaculture video series.

Yesterday I mentioned how I was going to wait until we get the ATV back to haul in the plywood piece, but the need for horse manure is strong this time of year...strong enough to inspire a do it yourself rope harness.

Last fall, I wrote

that the offspring

of my all-male asparagus plants looked like they might be all-male

as well.

Less than half of the young plants had bloomed their first fall,

but every bloomer at the time was male. Unfortunately, it

turns out that only the males bloomed their first year, because

now asparagus alley is sporting lots of tiny green balls on the

feathery fronds. In fact, the planting turned out to be 60%

female! I could pull out the female plants now that they've

identified themselves and add some new seeds, but the truth is

that getting to eat asparagus next year from this planting trumps

higher yields in the long run for me, so I'll leave it

as-is. But it's a handy data-point --- saving seeds from

all-male asparagus doesn't necessarily give you any gender

advantage in the offspring.

Another problematic

perennial that's come to my attention this week is our hardy

kiwis. We

planted two females and a male in July 2008, and have been waiting

for fruits ever since. For years, I thought the problem was

late spring frosts that inevitably nipped back the kiwis' young

growth, but this year's cold spells missed all but the lowest

leaves...and still no blooms. Hardy kiwis are supposed to

fruit by year 5 at the latest, and this is year 6. Any

ideas, or will I be forced to pull out my elegant vines, to be

replaced with something more productive? I've got newly

rooted figs and gooseberries looking for a spot in the garden, so

the area won't go to waste, but I hate to give up on my dream of

homegrown kiwis.

Lest you think our

perennials are all depressing, I should note that several of our

apple trees seem to be keeping their

fruits.

In fact, apples on the Early Transparent (a variety that usually

ripens in late June in our neck of the woods) are starting to hang

pendant and to look like real apples! I can hardly wait to

taste apples from our own trees, and I'm thrilled that one of the

first will be a taste test of the same variety in a high

density method

versus in a forest garden environment.

The high demands of the

summer garden slowed down for just a minute today allowing me to do

some work on the Star

Plate chicken coop.

We decided to leave a vent

hole towards the top of three of the walls.

I attached hardware cloth

with drywall screws and washers to keep out predators.

Even though I didn't

mention it on my

post about fungal-disease prevention, another big facet of my campaign is summer

pruning.

This is something I do anyway to allow light to hit fruits and to

prevent trees from putting too much energy into watersprouts, but

the process has a side effect of letting fruits dry off faster so

they're less prone to blights.

With that in mind, I

started wondering if thinning the fall-fruiting canes of my

everbearing raspberries was in order. I thin out the

overwintering canes so the spring-bearing shoots are spaced apart,

but last year I felt I should have repeated the endeavor in early

summer to get larger fall berries. The raspberry patches had

turned into quite a thicket this year (even more so than usual),

so my urge to thin was also prompted by wanting to be able to see

the currently ripening fruits during this first harvest season of

the year.

This is an experiment

(so replicate it at your own risk) since I've never read about

anyone thinning their raspberries in the summer. But it felt

right --- the photos above both show the patch after thinning out over half

of the fall shoots, and you can tell the canes are still quite

dense. As an added benefit, I was able to layer the cut-off

stems (and any weeds I found in the patch) along the sides of the

row to top off the mulch.

Of course, I'm also

thinning the trees I usually visit at this time of year (primarily

the peaches, although heavy fruit set has resulted in fewer

watersprouts this year than usual). When I stopped by our

largest fig, I wasn't sure whether it needed any pruning, but I

did decide to rip up any small shoots around the trunk. It

turns out three had already rooted! If I didn't kill them by

leaving them in a bucket of water during a blazing afternoon,

these baby figs will go into pots with my other

rooting cuttings

and then into the ground this fall.

The last item on my

summer-pruning agenda is the black

raspberries and blackberries, who get their tops pinched instead of being

thinned. Looks like we'll be adding another variety to our

daily berry harvest soon!

Got 2 more walls on the StarPlate

chicken coop done today.

Next up is the roof, a nice

door, and 2 half wall sections next to the door.

Even though the technical name for

strawberries that crop all at once is "June-bearing," our

June-bearers are usually May-bearers. This year's cool

spring pushed the fruits forward in time, but even so, we're

nearing the end of our harvest

season.

Monday, I put the last load in the dehydrator (bringing us to over

two gallons of strawberry leather preserved for winter), and ever

since we've been gorging on a mere 3 quarts a day.

Even though the technical name for

strawberries that crop all at once is "June-bearing," our

June-bearers are usually May-bearers. This year's cool

spring pushed the fruits forward in time, but even so, we're

nearing the end of our harvest

season.

Monday, I put the last load in the dehydrator (bringing us to over

two gallons of strawberry leather preserved for winter), and ever

since we've been gorging on a mere 3 quarts a day.

Next year, matters will be different because

we'll once again have a late-bearing

variety to join our early and midseason varieties. I ordered 25

Sparkle strawberries from Nourse Farms and have been highly

impressed by the plants' vigor. The roots were about four

times as large as those I got from Burgess last year, and the

plants are already trying to bloom. (I snip the flowers off

so we'll get good crops next year.)

Next year, matters will be different because

we'll once again have a late-bearing

variety to join our early and midseason varieties. I ordered 25

Sparkle strawberries from Nourse Farms and have been highly

impressed by the plants' vigor. The roots were about four

times as large as those I got from Burgess last year, and the

plants are already trying to bloom. (I snip the flowers off

so we'll get good crops next year.)

In the meantime,

we're eating red raspberries, the first black raspberries, and are

hoping the blueberries and gooseberries start to bear before the

last strawberries disappear. It's so sweet to have eaten no

storebought fruit for weeks.

The ATV

bucket hauler is near

completion.

Adding the plywood

extension will increase

the capacity from 6 buckets to 12.

I guess I should paint the

wood red to match the tongue, but will most likely go with whatever

exterior paint I can find in the barn.

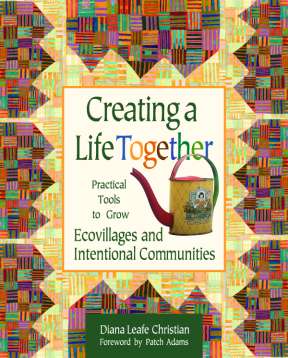

Creating

a Life Together,

by Diana Leafe Christian, is a step-by-step guide for building

intentional communities. Rather than summing up the key

points the way I usually do in my book reviews, though, I want to

take this opportunity to go off on a tangent and explore one of

the exercises the book recommends as part of a community visioning

process. The idea is to write about times when you've felt

like part of a community or a shared group activity, then to use

these recollections to consider what makes community-building work

for you specifically.

Creating

a Life Together,

by Diana Leafe Christian, is a step-by-step guide for building

intentional communities. Rather than summing up the key

points the way I usually do in my book reviews, though, I want to

take this opportunity to go off on a tangent and explore one of

the exercises the book recommends as part of a community visioning

process. The idea is to write about times when you've felt

like part of a community or a shared group activity, then to use

these recollections to consider what makes community-building work

for you specifically.

Beyond my family, the

first community I met was the science-fiction club at college,

which turned out to be a sort of non-drinking,

non-gender-specific, geeky fraternity. In retrospect, it's

easy to see why the community worked so well --- we had shared

interests, we ate nearly every lunch and dinner together (four

meals a week is the book's recommendation as the minimum shared

meals in a community), most of us went to folk-dance classes

together (shared movement seems to bond people), and we had a high

tolerance for unconventional or even problematic members (since

that was most of us at one time or another). On the other

hand, our club had a seamy underbelly in that people who attended

fewer events were considered para-club members, and they were

never really included. Later, I was to discover that this

aspect holds true across many communities and makes it tough for

introverts to find a good balance of personal space and community

involvement.

During my year

abroad, I spent

four months in Monteverde, Costa Rica, where a

band of expatriat American Quakers had developed an intentional

community in the midst of Hispanic culture. Although my

father is a Quaker, he didn't convert until I was a teenager  and he didn't drag the

rest of us along with him, so I was definitely in the "para"

category in Monteverde. (My short-term stay also put me in

that category, since the community sees lots of lookie loos

passing through and can't commit limited energy to each one of

them.) So even though I was inspired by the community

potlucks, their shared library accessible by walking paths, and

the way they seemed to involve their Costa Rican neighbors, I

never felt like part of the Monteverde community.

and he didn't drag the

rest of us along with him, so I was definitely in the "para"

category in Monteverde. (My short-term stay also put me in

that category, since the community sees lots of lookie loos

passing through and can't commit limited energy to each one of

them.) So even though I was inspired by the community

potlucks, their shared library accessible by walking paths, and

the way they seemed to involve their Costa Rican neighbors, I

never felt like part of the Monteverde community.

Fast forward ahead a

decade, and Mark and I had settled a mile down the road from

another intentional

community.

After a few years of sporadically attending their events (and

perhaps because most of them knew my parents during the 70s and

80s), there were even noises about asking us to join. I like

my crazy experiments (no way urine

fertilizer and

trailersteading were going to fly

there), and I'm just too antisocial to live that close to anyone

except Mark, so we graciously declined. Again, we've ended

up in a para-community situation, although this time I feel a

little closer to the core because we're definitely in the area for

the long haul and we share many of the community's ideals.

But we still miss having

like-minded friends our own age around. (As you probably

gathered, the neighboring intentional-community members are

primarily from our parents' generation.) So Mark and I have

considered crazy community-building concepts of our own from time

to time. We'd tossed around the idea of buying up a large

tract of land, planning it as a community, then selling tracts to

interested and interesting folks. Or perhaps finding a

couple-sized homestead nearby and partnering with someone who

might trade labor for the cost of the land. Or finding a

partner to do the day-to-day work but being involved in the

bigger-picture planning and implementation of an

educational/internship program. The truth is, though, that

even if we found just the right people, neither Mark nor I has the

socializing budget to put in the hours required to build a real

community from scratch.

But we still miss having

like-minded friends our own age around. (As you probably

gathered, the neighboring intentional-community members are

primarily from our parents' generation.) So Mark and I have

considered crazy community-building concepts of our own from time

to time. We'd tossed around the idea of buying up a large

tract of land, planning it as a community, then selling tracts to

interested and interesting folks. Or perhaps finding a

couple-sized homestead nearby and partnering with someone who

might trade labor for the cost of the land. Or finding a

partner to do the day-to-day work but being involved in the

bigger-picture planning and implementation of an

educational/internship program. The truth is, though, that

even if we found just the right people, neither Mark nor I has the

socializing budget to put in the hours required to build a real

community from scratch.

Which brings me to my

main complaint about Creating a Life

Together

(and the intentional-community movement it portrays so

well). Even though most of the communities in the book are

located in rural settings, they're essentially country homes for

city people --- the inhabitants generally come from urban areas,

they live clustered together on their new land, and they are

presumably highly-social people. There's a short segment

titled "Creating privacy in the midst of community," but the page

basically consists of telling you to plan your house so you can

feel alone when you're indoors. Isn't the whole point of

homesteading to be able to do whatever you want outdoors?

So here's my

thought-question for our readers. Have you ever met a

community that adequately involves introverts without draining

their social energy past their limits? Or is community

really just for extroverts, no matter where it's located?

Adding a proper

hitch coupler to the ATV

bucket hauler turned out

to be easy.

One of the top holes lines up

with the Haul Master tongue. The other hole is just

barely off. Securing the first hole with a bolt and nut makes for the

perfect drill guide for the second hole.

I topped it off with a somewhat

toxic adhesive to keep

the nuts from loosening. Since Toluene was banned in Europe in 2004 for

sale to consumers I make sure to not get any on my skin.

Our new

package hasn't

done all that much, but they seem to have settled into their box

of partially-drawn comb, and perhaps have drawn a bit more.

By listening at the side of each box, I gather that the top box is

completely empty still, so the colony has plenty of room to spread

out. These guys are going through a quart of heavy

sugar water

every two to three days, but seem to be finding lots of wild food

as well. Since the workers are bringing home plenty of

pollen, I'm assuming the queen is laying and the hive will be

expanding soon.

Since I added

two empty boxes to the bottom of our oldest warre hive, taking a photo up

through the bottom only tells me so much. But I'm guessing

by the mass of bees I can see between the bottom box's bars (and

by listening at the side of each box) that the bees have drawn

comb in the next box up and are hard at work there. They're

also buzzing busily in the third box from the bottom, but the

fourth box up has gone much quieter, suggesting it's full of

capped honey.

Neither hive needs

another box yet, but I'm going to keep a close eye on them since

the basswood

buds look

nearly ready to open. This has been a stellar year for

nectar, and I suspect that with the help of the basswood, I'll be

getting an appreciable harvest from the older warre hive despite

their swarm.

Found a can of good blue

exterior paint that we got from the Lowes reject bin years ago.

There should be enough to do

the underside and maybe a second coat.

I guess I'll be checking out

the reject bin the next time I'm there...It's very convenient to have a

can standing by for future projects.

Two

weeks ago, I harvested our Italian Softneck garlic, and this week the Music

and Silverwhite Silverskin were finally ready to join their

precocious siblings on the curing racks. It's shaping up to

be a mediocre year for alliums, probably because of a cold winter,

lack of sun during the critical bulking up period this spring, and

perhaps mineral

burn.  Although I'm a bit disappointed that my

garlic heads are only 75% to 100% as large as storebought rather

than 100% to 200% as large, we plant extra to hedge our bets, so

we'll still enjoy a garlicky season.

Although I'm a bit disappointed that my

garlic heads are only 75% to 100% as large as storebought rather

than 100% to 200% as large, we plant extra to hedge our bets, so

we'll still enjoy a garlicky season.

Half of the potato

onions were also ready this week (with the ones closer to the

shady hill needing a bit more time). Again, the bulbs were

smaller than last

year, but

larger than the year before when I gave

up on one variety and changed

over to this one.

With the curing racks completely full of garlic, I had to cobble

together makeshift arrangements for the onions. Most went

into old freezer baskets propped off the ground, but I'm hoping

even the ones on this gutter downspout (not under the gutter) have

enough airflow to dry well.

Completely unrelated,

we're making the transition to raspberries, and loving every

minute of it. At the peak of strawberry season, I can't

imagine wanting any other berries, but now that the quality is

declining in the strawberry beds, the raspberries become my

favorites. A delicious quart full!

The last full wall to be

filled in on the StarPlate

chicken coop didn't have

much space for board attachment, which is why I decided to install

these boards on the inside.

My brother

and sister-in-law are visiting from California, a twice-per-decade event, so

I'm mostly playing hooky this week. I apologize in advance

if my posts are on the light side, or if I bore you with family

photos. (For the record, the images above are not representations of my

family. I managed to take 17 pictures of silkworms and 16

pictures of plants on my first visiting day...but none of my

long-lost family members. I'll try to do better. But

silkworms are just so darn cute!)

Anyway, on to the

meat of this post, which is --- cucurbits! It's officially

summer when the members of Cucurbitaceae begin to take over the

world.

We ate our first cucumber on Tuesday, and

many more are just about ready to be consumed. The summer

squash are also starting to bloom, albeit only male flowers at

first.

We ate our first cucumber on Tuesday, and

many more are just about ready to be consumed. The summer

squash are also starting to bloom, albeit only male flowers at

first.

Mark asked me a

couple of weeks ago if we'd planted fewer cucumbers than last

year, when I sent him to town with bagsful to dispose of and even

the librarians got sick of the bounty. I'm ashamed to say, I

kept my planting at the same size. If our new varieties and

methods overflow our coffers with cucumbers again this year, I'll

cut back, but with the wetness of the season, I'm kinda glad I'm

hedging my bets by overplanting.

I decided to fill in the

StarPlate half walls with some scrap tin.

The bottom piece sits in a 3

inch trench to discourage digging.

This has been a great

year for free fruiting perennials. Not only do our figs and grapes seem to be rooting very

well, I found another eight gooseberry plants that have popped

up around the base of one of our older gooseberries. With such a

profusion of riches on hand, the question becomes --- how many of

these newly-rooted fruit plants should I put in the ground this

fall, and how many should I give away? Plus, I also want to

fit in another hardy kiwi since I've decided to give ours a few

more years' grace and also to try

the specific variety and source Throwback at Trapper Creek

suggested.

There are two main

factors involved in my decisions --- filling in physical gaps in

the core homestead and filling in temporal gaps in our fruiting

schedule. Starting with the latter, the table below sums up

fruit plants we already have on the farm (or are definitely

installing this fall):

| Variety | Harvest date | Dependability | Work |

Fruiting now |

| Honeyberry, Blue Sea | ?early May | High? | High | |

| Honeyberry, Blue Velvet | ?early May | High? | High | |

| Strawberries | mid-May to mid-June | High | High | x |

| Raspberry, Caroline Red | June through Fall | High | High | x |

| Black Raspberry, Jewel | early June | Medium-high | High | |

| Raspberry, Bristol Black | mid to late June | Medium-high | High | x |

| Apple, Early

Transparent |

late June |

Medium? |

Low |

x |

| Red Currant | late June | High? | High | |

| Gooseberry, Poorman | late June | High | High | x |

| Gooseberry, Invicta | late June | High | High | x |

| Blueberry |

late June to ?Aug. |

High |

High |

x |

| Blackberry | July | Medium | High | x |

| Plum, Imperial Epineuse | ?July | Low? | Low | |

| Apple, Pristine | July to Aug. | Medium? | Low | |

| Apple, Summer Rambo | July to Aug. | Medium? | Low | |

| Grape, Mars Seedless | ? late July to early Aug. | Medium? | Medium | |

| Grape, Thomcord | August | Medium? | Medium | |

| Peach, White | mid August | Low | Low | x |

| Peach, Cresthaven | md Aug. | Low | Low | |

| Plum, Seneca | mid Aug. | Low? | Low | |

| Grape, Reliance | ? mid Aug. | Medium? | Medium | |

| Fig, Celeste | ? Aug to frost | High? | Low | |

| Apple, Zestar! | Sept. | Medium? | Low | |

| Grape, Marquis | ? Sept. | Medium? | Medium | |

| Kiwi, Hardy, Dunbarton Oaks | Sept - Oct | Low? | Low | |

| Apple, Liberty | Sept to Oct. | Medium? | Low | |

| Apple, Sweet Sixteen | Sept. to Oct. | Medium? | Low | |

| Fig, Chicago Hardy | Sept. through frost | High? | Low | x |

| Pear, Seckel | Sept. (and keeps) | High? | Low | |

| Pear, Keiffer | late Sept. (and keeps) | High? | Low | |

| Apple, Winesap | late Sept. (and keeps) | Medium? | Low | |

| Watermelon | October | Medium-high | Low | x |

| Kiwi, Hardy, Ananasnaya | Oct. | Low? | Low | |

| Apple, Virginia Beauty | Oct. (and keeps) | Medium? | Low | x |

| Apple, Red Empire | Oct. to Dec. | Medium? | Low | x |

| Apple, Grimes Golden | Oct. to Jan. | Medium? | Low | |

| Apple, Enterprise | Oct. to Jan. | Medium? | Low |

Even though it seems

like we've got the whole fruiting season covered, it's worth

noting that some plants are very undependable --- for example,

we've only gotten fruits from our peaches one year in three so

far. Other plants --- like most berries --- are quite

dependable, but take so much time to pick that I can only handle

so many plants. Plus, who knows which of the varieties that

haven't yet fruited will end up working for us, and which ones

will be ripped out for one reason or another?

All of that said, there are potential gaps in

August (if the peaches fail), September (if the apples fail), and

among keepers. Increasing our fig planting seems like a good

way to potentially fill the August and September gap with a

dependable and only medium-work fruit, and grapes might also hedge

our bets during the late-summer period. I suspect we don't

really need any more gooseberries, though, since they produce at

the same time as Early Transparent apples, black raspberries, and

red currants, but I'll slip in a couple since gooseberry bushes

are small and fruit even in partial shade, so they help fill

troublesome spatial gaps.

All of that said, there are potential gaps in

August (if the peaches fail), September (if the apples fail), and

among keepers. Increasing our fig planting seems like a good

way to potentially fill the August and September gap with a

dependable and only medium-work fruit, and grapes might also hedge

our bets during the late-summer period. I suspect we don't

really need any more gooseberries, though, since they produce at

the same time as Early Transparent apples, black raspberries, and

red currants, but I'll slip in a couple since gooseberry bushes

are small and fruit even in partial shade, so they help fill

troublesome spatial gaps.

Speaking of which,

where do I have room for new plants? We're working hard not

to expand our boundaries (except for potential pastures), but

there are still a remarkably large number of sites right here in

our core homestead:

| Location |

Characteristics |

Possible

plants |

| By well |

shady, kill-mulched

spot |

1 gooseberry |

| Along pasture fence |

shady, kill-mulched

spot |

1 gooseberry |

| Pastures |

semi-shady |

extra gooseberries |

| Gaps in forest garden |

Mostly sunny,

high-groundwater (but can plant on mounds) |

5 figs |

| Old grape row in mule

garden |

Sunny, trellised |

3 grapes (or 2 grapes

and 1 kiwi) |

| South-facing side of

gully |

Sunny, would have to

be terraced (lots of work) |

3 grapes |

| South side of front

porch |

Scorching sun in

summer, but potential frost pocket |

Grapes? |

The spots to slip in gooseberries are pretty

obvious, and the figs will work well in the forest garden as long

as I build quality mounds to keep their feet dry. But what's

a good fit for the porch-side plantings, which have the primary

goal of shading our living quarters in the summer? I'm

leaning toward grapes at the moment, although I'm not sure the

plants will thrive there.

The spots to slip in gooseberries are pretty

obvious, and the figs will work well in the forest garden as long

as I build quality mounds to keep their feet dry. But what's

a good fit for the porch-side plantings, which have the primary

goal of shading our living quarters in the summer? I'm

leaning toward grapes at the moment, although I'm not sure the

plants will thrive there.

I know it seems very

early to be planning our perennial plantings, but if I set my

sight on new spots now, I can just dump wheelbarrows full of weeds

there to build mounds and act as a kill mulch, keeping soil

preparation time to a bare minimum. Plus, knowing how much

room I have for new perennials keeps me from trying out twenty new

varieties that won't fit in our core homestead. (That said,

if you have types of fruit to suggest that would round out our

planting, I'm always open to suggestions because there's nothing I

love more than trying new plants.)

The ground we built our StarPlate chicken coop on has a medium degree slant.

We decided chickens didn't

need a perfectly level floor, so we elected to not dig out a flat spot

or prop one end up.

Making the door frame square

seems to be a good way of correcting for the hillside slant.

--- I've forgotten who posted this question, but someone did a few weeks ago

We don't generally have problems with birds

in the strawberries. (In the photo above, the cardinal is

actually stealing some buckwheat seeds that weren't adequately

covered by straw.) However, I've noticed a lot of bird

activity in the black raspberries, and a minimal amount of damage

to the red raspberries.

We don't generally have problems with birds

in the strawberries. (In the photo above, the cardinal is

actually stealing some buckwheat seeds that weren't adequately

covered by straw.) However, I've noticed a lot of bird

activity in the black raspberries, and a minimal amount of damage

to the red raspberries.

I don't know why the

blacks are preferred --- perhaps just because they're small enough

for a bird to easily gulp down, or the higher proportion of seeds

makes them more nutritious. But even with lots of birds

eating, we've been getting quite a good harvest.

I may change my tune

when our blueberries come into full production, but so far, I

don't net any of our berries or worry too much about bird

predation. There's so much wild food around that our berries

are just a side dish for them, and a main crop for us.

In the meantime, I've

noticed phoebes picking cabbage worms off the broccoli and have

even noticed a cardinal swooping down to catch an insect in

midair. (I'm well aware that cardinals are supposed to be

obligate seed- and fruit-eaters, but clearly they don't know

that.) So, in the long run, having birds in our garden is a

net plus.

I used a total of twenty 3/4

inch sheet metal screws to attach the plywood

extension to the base of

the Haul Master lawn trailer.

The rear side has 6 holes you

can use that were meant for a side brace if you add the right size

washer. The other 14 points will need a pilot hole.

Tales of books read,

berries wildcrafted, and rivers swum.

Only family truly

understands how awesome it is that there's a mulberry tree along

the driveway near where you're visiting, so you can snag some

silkworm fodder on the way home.

I forgot to mention that the new neoprene

hip waders have the Cabelas

brand name.

The neoprene material seems

much better suited for this application than the previous rubber hip

waders. I think the rubber dried out a bit and started cracking which

caused small leaks.

Neoprene cost a lot

more...these were close to 100 dollars, but well worth it if they last

twice as long as the rubber ones.

Wendy Jehanara Tremayne

sent me a copy of her beautiful and unconventional book, The

Good Life Lab a few weeks ago, and once I finally cracked

the cover, I swallowed the whole thing down in a few

sittings. The first two-thirds is a memoir/treatise on how

and why Wendy and Mikey quit the fast life in New York City for a

small-town homestead in New Mexico, and the last third is full of

useful tips such as using rainwater in place of distilled water in

batteries. I suspect that anyone who enjoys this blog would

love Wendy's book (and chances are you'd also enjoy the blog she shares

with her partner and the profile I included about Wendy and

Mikey in Trailersteading).

Wendy Jehanara Tremayne

sent me a copy of her beautiful and unconventional book, The

Good Life Lab a few weeks ago, and once I finally cracked

the cover, I swallowed the whole thing down in a few

sittings. The first two-thirds is a memoir/treatise on how

and why Wendy and Mikey quit the fast life in New York City for a

small-town homestead in New Mexico, and the last third is full of

useful tips such as using rainwater in place of distilled water in

batteries. I suspect that anyone who enjoys this blog would

love Wendy's book (and chances are you'd also enjoy the blog she shares

with her partner and the profile I included about Wendy and

Mikey in Trailersteading).

The book's spare,

easy-to-read prose has deep thought underneath, combined with just

the right level of mysticism to make me think without turning me

off. Wendy explains that people in Truth or Consequences,

New Mexico, barter everything...except the one thing that person

uses to make a living, which is always paid for. She writes

about turning online community into real

community with the addition of a week-long, in-person visit

of her favorite bloggers, and she walks you through her decision

to keep her businesses at the cottage level so that she and her

partner can do it all at home.

Wendy also has a

solution for one of the most thorny issues I see among

homesteaders --- they want to quit their jobs, but don't know how

they would fill their time instead. She wrote:

(Apparently, what I

most wished to do this weekend was to play in the rain, and a

storm obliged by raging through. If I had any doubt that I

live in paradise, a rainbow ending in the side of the barn helped

clear up that issue. Which is a long way of explaining that

the photos in this post have nothing to do with Wendy's book,

except for inspiration.)

In addition to the two holes

on top of the hitch

coupler you can also use

two on each side.

I'm thinking the top two

will be enough, mainly because I couldn't quite figure out the best way

to line up where to drill the hole on the tongue.

One thought I had was to use

a nail on the coupler side and hit it with a hammer to make an indent

where the hole needs to be drilled, but it's a difficult space to get a

hammer in and I was ready for it to be done.

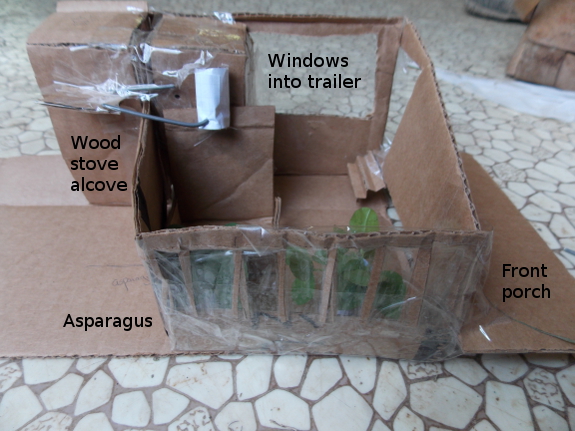

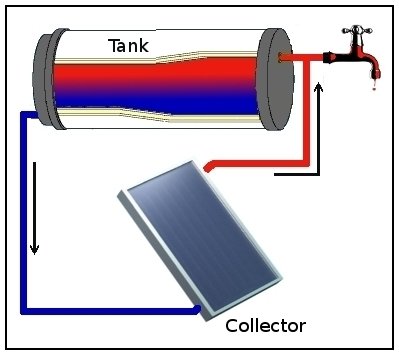

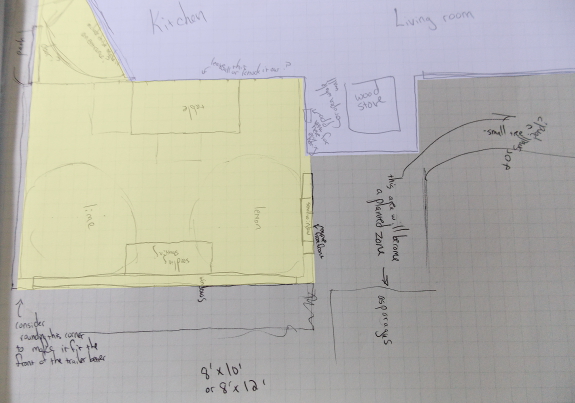

As much as I love

maps and other two-dimensional representations of the world,

sometimes it's easier to think if you visualize in three

dimensions. So Huckleberry and I sat down to model various

options for sunroom or greenhouse add-ons

to the south side of the trailer.

The more we cut and

pasted, the more we began to lean toward the sunroom option with a

face of windows and a solid roof. We live in an area with

both cold winters and hot summers, so it's always a balancing act

to decide which aspect we mitigate most. A greenhouse would

really boost winter temperatures and provide much more growing

area...but would result in a heat problem in the summer.

I've been reveling in the lower interior temperatures (high of 82

instead of 100 on ultra-hot days) since our new

trailer roof

went on, and I don't want to risk overheating our interior

again. So my current thought is that anything attached to

our living space should be a sunroom with a non-translucent roof.

That said, I do want

to ensure we have space for two large dwarf citrus plants

(represented by clover in the model above) as well as a real

bathtub/shower. After playing around with the model for a

while, I settled on including one of our IBC tanks to collect roof water

and feed a thermosyphon solar hot water heater (located outside

--- summer use only), while also providing thermal mass inside the

sunroom.

Questions I'm

pondering about this aspect of the project:

- Will the tank be high enough to provide the water pressure

Mark craves from his shower without a pump or pressure tank?

- Is it feasible to elevate the heavy, water-filled IBC tank

that high?

- If we opt for a concrete slab floor (extra work, but more

thermal mass and easier to deal with watery projects), will it

make it a nightmare to plumb an exit pipe channeling overflow

from the rainwater collection tank and the bathtub out to the greywater

wetland?

In terms of location, I've been envisioning

this add-on buffering the area between the wood stove alcove and

the front porch, where we already have a bank of south-facing

windows opening into the trailer. This zone gets lots of

sun, is close to our primary heat-source (so will be relatively

easy to keep above freezing for the citrus in the winter), and

will back up against one openable window (making it easy to

monitor airflow between the sunroom and the main trailer.

In terms of location, I've been envisioning

this add-on buffering the area between the wood stove alcove and

the front porch, where we already have a bank of south-facing

windows opening into the trailer. This zone gets lots of

sun, is close to our primary heat-source (so will be relatively

easy to keep above freezing for the citrus in the winter), and

will back up against one openable window (making it easy to

monitor airflow between the sunroom and the main trailer.

On the other hand,

this location basically negates the windows we already have in

place. Perhaps it would be smarter to turn part of the

current front

porch into a

sunroom, since adding windows there would increase our solar gain

(and the whole project would be much cheaper since the roof is

already on the porch). But the porch location would also add

more to our heating costs since I currently keep the portion of

the trailer behind the front porch only minimally heated in the

winter, and the citrus would need more warmth.

And then there's

human (and dog) traffic patterns to consider. The map above

shows our current major activity routes, all of which have

wider-than-usual access so that Lucy doesn't accidentally trample

my garden when she's excited and so we don't have to be constantly

brushing past plants when we carry things in and out. A

sunroom between the wood stove alcove and front porch would block

one of those paths, which might cause problems with Lucy in the

garden and would definitely inconvenience Mark twice a week when

he lugs bulky bags of chicken waterers down the shortcut to

town.

And then there's

human (and dog) traffic patterns to consider. The map above

shows our current major activity routes, all of which have

wider-than-usual access so that Lucy doesn't accidentally trample

my garden when she's excited and so we don't have to be constantly

brushing past plants when we carry things in and out. A

sunroom between the wood stove alcove and front porch would block

one of those paths, which might cause problems with Lucy in the

garden and would definitely inconvenience Mark twice a week when

he lugs bulky bags of chicken waterers down the shortcut to

town.

So, lots to ponder,

but at least our model got the ball rolling. I suspect the

sunroom will be our big, expensive project of the year, so I want

to put as much thought into planning as possible.

It's that time again --- the season to

send out more Egyptian onion propagules into the world!

Those of you who have read The

Weekend Homesteader know that this perennial green onion is easy to grow and to

cook with. (You can

read more about it here.) To sweeten the pot, Egyptian onions produce top

bulbs copiously at this time of year, which is an incentive to

share with friends.

It's that time again --- the season to

send out more Egyptian onion propagules into the world!

Those of you who have read The

Weekend Homesteader know that this perennial green onion is easy to grow and to

cook with. (You can

read more about it here.) To sweeten the pot, Egyptian onions produce top

bulbs copiously at this time of year, which is an incentive to

share with friends.

This year's Egyptian onion giveaway is an

everyone-wins affair. Just share your favorite Walden Effect

post on the social media platform of your choice (facebook, google

plus, twitter, pinterest, your blog, etc.), email

anna@kitenet.net with your mailing

address, and I'll mail a box of about 100 onion top bulbs to

your doorstep to fill your garden (and neighborhood) with

green-onion goodness. I'll keep mailing out top bulbs

until we run out (at which point I'll make a note on this post),

but I expect we'll have enough for at least the first twenty

folks. Enjoy!

Edited to add: All of the onions have been homed. Thanks to

everyone who entered!

I'm really liking this new Outdoor

Products Arrowhead 8.0

framed back pack.

I've had it for a few months

now and think it's superior to all the other book bags.

It's got a hefty handle that

lets you carry it as a bag and plenty of zippered pockets to stow that

back up flashlight.

One of our fun

projects this past winter was creating a greywater wetland to deal

with the water coming out of our kitchen sink. You can read

more about the wetland by following the links below:

- Inspiration

for the wetland. (Be sure to follow the links at the

bottom of the post for the rest of the lunchtime series.)

- Planning the wetland

- Digging out the wetland area

- Planning the pipes

- Rocking in the inlet to prevent erosion

- Installing the pipes

- More

on the pipes (and pond)

- Greywater wetland's first inundation

- Plans

for the future

So far, the wetland

has been quite effective, although it has the usual growing

pains. I'll show you what's working (and what's not) below.

The water from our kitchen sink is enough to

keep the area where I planted cattails (just below the inlet)

sodden. This has resulted in very happy plants, one of which

is putting up a flowering spike. I'm ultra-excited about the

spike because I've wanted to taste cattail flowers ever since Eric

blogged about them, but I'm too busy at this time of year to make weekly trips

to the wetland up the holler to check on the cattails'