archives for 05/2013

The effects of cover crops are surprisingly

long-lasting in the garden. This spring, I've been finding

stunning oilseed

radish skeletons littered throughout the garden beds, along with a

few roots that must have survived the winter by freezing solid then

slowly thawing during our cold spring. Of course, the most

noticeable effect of winter cover crops is soft, dark soil in beds that

barely have any weeds, and I've definitely been enjoying the easy

spring soil prep that radishes made possible.

The effects of cover crops are surprisingly

long-lasting in the garden. This spring, I've been finding

stunning oilseed

radish skeletons littered throughout the garden beds, along with a

few roots that must have survived the winter by freezing solid then

slowly thawing during our cold spring. Of course, the most

noticeable effect of winter cover crops is soft, dark soil in beds that

barely have any weeds, and I've definitely been enjoying the easy

spring soil prep that radishes made possible.

The rye also seems to be working

well, with the tallest plants just starting to bloom. We'll cut

the rye down early next week, once most plants are blooming, and then

I'll plant

directly into that mostly weed-free soil around the beginning of

June. Rye will provide a homegrown mulch for summer vegetables,

and the tall grain outcompeted most weeds over the winter and early

spring.

The cover crop circle

continues with buckwheat soon to go into any open beds that won't be

used for crops until at least June 1. I managed to plan out my

garden rotation for the rest of the year already, which will make it

easy to slip buckwheat into beds that are slated to be used for late

plantings of corn, beans, squash, and cucumbers. A few beds are

even due to be left fallow until fall, which, in practice, means back-to-back

plantings of

buckwheat all summer long.

My goal is to use an

entire 50-pound bag of buckwheat seeds this year, which should add an

astonishing amount of organic matter to the soil. Care to enroll

your garden in my Buckwheat Challenge? You can usually find

buckwheat for about 30 cents per pound at the feed store, so you'll

likely find buckwheat-produced organic matter cheaper than any

storebought soil amendment.

It took us about four years

to find a dry spot for the hammock chair Sheila gave us. But the

actual hanging only took fifteen minutes, including cutting

the chain.

Hanging cost: $1.60 quick link plus $2.15 chain. Watching the

first lightning bugs while swinging on the porch: priceless.

Mark looked at me like I

was nutty when I told him our core homestead felt smaller this

year. "You do realize we expanded the boundaries in a couple of

places, don't you?" he asked. Well, yes, I do know that our core

homestead is actually bigger in a spatial sense, but we

seem to be starting to hit the fewer-weeds plateau that established

gardens eventually acquire, which gives me tidbits of time for play

even during the height of planting season.

This week's play has

consisted of planting two beds of flowers, something I never seem to

find time for in the spring, but always regret when summer rolls around

flower-free. One bed is an area I kill-mulched in front of our

south-facing bank of windows last fall. I added a trellis and Dani's mystery

beans in the back of

the bed, then set out some seedling sunflowers, zinnias, and marigolds

that I'd started inside a couple of weeks ago. I hope the result

will be a shady trailer interior this summer, along with a pretty view

when we eat on the porch.

This week's play has

consisted of planting two beds of flowers, something I never seem to

find time for in the spring, but always regret when summer rolls around

flower-free. One bed is an area I kill-mulched in front of our

south-facing bank of windows last fall. I added a trellis and Dani's mystery

beans in the back of

the bed, then set out some seedling sunflowers, zinnias, and marigolds

that I'd started inside a couple of weeks ago. I hope the result

will be a shady trailer interior this summer, along with a pretty view

when we eat on the porch.

The other bed is

similar, but minus the beans and located in the forest garden.

That spot is really for the bees since there's no often-used human zone

nearby.

Of course, most of my

garden time has been spent on more worthwhile pursuits, such as weeding

and planting. Even though we could have a frost anytime during

the next two weeks, the 10-day forecast looks freeze-free, so I put in

green beans, mung beans, sweet corn, cucumbers, crookneck squash,

watermelons, okra, and basil seeds last Friday. After a weekend

of heavy rain, I expect to see sprouts any day now and am hoping our

late spring won't mean a late summer after all. If the weather

decides to be tricky and slam us with a late frost, I can just replant

--- it's worth risking a couple of dollars' worth of seeds for the

chance of early harvests.

We recently ordered 2 bungee

nets from Amazon.

They seem to be a perfect

size for securing 5 gallon buckets to the ATV.

Remember my willow

rooting hormone experiment? The three fig

cuttings above were the control and the fig to the right is one of

the cuttings treated with the willow hormone. An unscientific

observer would probably say: "Clearly the willow rooting hormone did a

great job!" But let me throw a bit of data at you:

Remember my willow

rooting hormone experiment? The three fig

cuttings above were the control and the fig to the right is one of

the cuttings treated with the willow hormone. An unscientific

observer would probably say: "Clearly the willow rooting hormone did a

great job!" But let me throw a bit of data at you:

Celeste

Fig:

- Willow: 1 awesomely-rooted cutting (shown to the right), 1 well-rooted cutting, and 1 cutting not rooted at all.

- Control: All three cuttings have small roots (photo above).

Dwarf

Fig:

- Willow: 1 cutting with a small root and three unrooted (photo

below).

- Control: 2 cuttings with small roots and one unrooted.

Black

Mission Fig:

I haven't dug into this

pot yet.

After looking at the

data, my conclusions are:

- Celeste Figs are easier to root than Dwarf Figs.

- The willow rooting hormone may do nothing, or it might impact

different varieties in different ways. It seems worth trying the

willow rooting hormone again with Celeste, but maybe not with the Dwarf.

All of this geekery aside,

the reason I was delving around in my fig pots is that I noticed the

plants with the biggest leaves wilted a bit when I placed them in full

sun this week. Now that I see how few roots most of the cuttings

have, I understand why.

All of this geekery aside,

the reason I was delving around in my fig pots is that I noticed the

plants with the biggest leaves wilted a bit when I placed them in full

sun this week. Now that I see how few roots most of the cuttings

have, I understand why.

I had originally planned

to transplant these cuttings into a nursery bed in the garden for the

summer, but I opted, instead, to pot them up into individual pots large

enough for a full summer's root growth. That way, I can keep the

cuttings in partial shade on the edge of the porch until they've got

their feet under them a little more and are ready to go in the ground

in permanent locations this fall. Plus, now I can start rehoming

the extras --- the three figs shown here have already moved to our

movie-star neighbor's high-class accommodations.

We could've installed the trailer ball directly onto the ATV, but this

receiver hitch is reversible to adjust the height.

The main reason we went this

route was to provide a hook- in point for a future hitch basket carrier

for days when we don't need a trailer but could use a little extra

storage.

It's best to have at

least two hives of honeybees, so one of my goals

for this year is to double the size of our apiary. How exactly to

do that has

been an issue I've been pondering for months. Here are your main

options for getting new bees:

- Split an existing hive.

I've done this before with good luck, but it does have three

downsides. First, Warre hive enthusiasts believe you shouldn't

open the hive more than once a year, and splitting is

majorly intrusive. Second, since we're in the very early stages

of developing a chemical-free apiary, splitting wouldn't give us much genetic

diversity.

(The queen for the new hive would have the queen from the old hive as

her mother, and would likely mate with drones from the old hive since

we're pretty isolated back here in the woods. Inbreeding can be

good...or it can be bad.) And, finally, we probably wouldn't get

much, if any honey, this year if we split the hive.

- Catching a swarm. This is the Warre-approved method of getting new bees from your current hive. If we don't split our current hive, chances are it will swarm this spring because the bees seem to have already filled two boxes and are working on their third. Putting up a swarm-attractant box could help capture that swarm. This is chancy, of course, and has the same genetic problems as the option above, but is definitely worth a shot.

- Buying a new package.

After long thought, we've decided to go with a new package this

spring. I found a new

source of chemical-free bees in Maryland

(whose bees are actually raised in the mountains of Tennessee and

Georgia --- pretty close to us). The proprietors explained that

their bees are a mix of Carniolan and Russian varieties that have been

raised on small

cell and natural comb without chemicals for several

years, so the ones that survived are better adapted to living without

miticides and other pharmaceuticals.

In the long run, our

goal is for the apiary to be self-sustaining, but

since we've only got one hive at the moment, paying for a new package

this year makes sense. Stay tuned for the big install next week!

The Haul-Master trailer

cart showed up with a problem.

It's missing all the hardware

except a bag of small bolts.

Calling the Harbor

Freight tech support line was a joke. No real person to talk to and

a frustrating phone tree that just directs folks to the website. The

only way to communicate a problem seems to be through email. They claim

response time should be between 24 and 48 hours, but I'm going on the

third day with no help.

Nearly a decade ago, I got

bitten by a dog. I was helping a friend of a friend move tables

out of the cultural center she helped run, and her dog was napping in

the corner. The dog seemed nice, and I assumed the friend of a

friend would have warned me if it had a tendency otherwise, so I

ignored it and started hauling. But on my third or fourth trip,

the stars aligned wrong and the dog turned its head just as my foot

went in its direction, and I bumped the dog's chin with my knee.

Nearly a decade ago, I got

bitten by a dog. I was helping a friend of a friend move tables

out of the cultural center she helped run, and her dog was napping in

the corner. The dog seemed nice, and I assumed the friend of a

friend would have warned me if it had a tendency otherwise, so I

ignored it and started hauling. But on my third or fourth trip,

the stars aligned wrong and the dog turned its head just as my foot

went in its direction, and I bumped the dog's chin with my knee.

The seemingly-friendly

dog went nuts, snarled, and bit a big gash into my hand. My

initial reaction (after the usual surprise and terror that a dog bite

brings) was to reassure the friend of a friend that it wasn't the dog's

fault. After all, I knocked its chin. Sure, a dog like Lucy

would turn the other cheek in that scenario, but who knows what had

happened in the dog's past to put it on such a short fuse? My

motto is: if in doubt, take responsibility.

And now, ten years

later, Mark and I sustained the human equivalent of that dog

bite. It was even more painful this time around, and will

probably make me twice as people-shy as that dog bite made me

dog-shy. But it's over now (and, no, I don't plan to hash the

issue out in a public forum, although I may write about what I learned

in a decade once everyone has moved on). The upshot is, you won't

be seeing B.J. on our blog any more, but

you will be seeing the returned truck doing hauling for us without

its former master.

Even though our first

impulse was to give up on community-building experiments, Mark and I

have determined that the issue is a tough nut to crack, but is still

worth pursuing. If it were easy, everyone would be doing it,

right?

More on our next

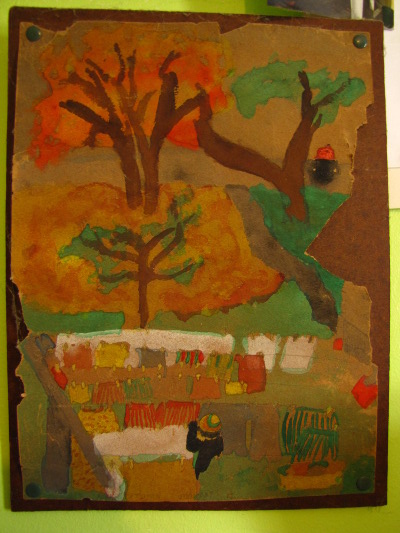

experiment in a later post. Meanwhile, I hope you enjoy these

photos from my cheer-up visit to my mom --- the first one is a painting

she made as a child of her mother doing laundry, the second is the

creek I grew up beside, and the last is a tough nut to crack.

We'll just keep gnawing away like that squirrel until we get it right.

It's been a year since we

first installed the DIY

chicken feed trough.

One thing I might do

different next time would be to make the inside of the trough more of a

V shape. It might also help if it was secured in a way that was easy to

lift out and clean.

Katie

asked for a tour of the inside of our trailer, and while I'm not ready to

oblige yet, I thought I'd share a few little-known truths about living

in a tiny house (or trailerstead). These all seem like

lemons on the surface, but can be turned into lemonade with a little

care.

There

are no public spaces in your house. Those of you who live

in large houses probably don't pay much attention to the way your

residence has public spaces where you don't mind inviting strangers in,

as well as private spaces like your bedroom. Tiny houses double

up functions, which tends to make all spaces feel private (at least to

a shy introvert). Solution: Build a nice porch and only invite

people over in the summer. Silver lining: Small spaces feel cozy

during the 99% of the time you spend at home with only your family

around.

Only

one person can move around in a room at a time.

Small spaces mean that you need to find a spot to settle once you're

inside, then stay there. Solution: I have no clue how families

with

rowdy kids handle this, but for Mark and me, it generally means

treating the trailer like a time-share --- when I'm cooking, he stays

out of the kitchen, and vice versa when the dishes are being

done.

Silver lining: Not sure whether to mention this since it's PG-13, but

you

can imagine how this adds to marital harmony.

Walls

are not for art.

Chances are, you'll need every speck of wall space for some combination

of windows, shelves, and hanging things. Solution: Maybe the art

should go in the outhouse? Silver lining: It's much easier to

keep your life relatively simple if you look at all of your accumulated

possessions every day.

Your

smoke detector will go off at least once a week. Even the

best smoke detectors

are designed for larger residences, so chances are good you'll set

off false alarms quite frequently. Deglazing a greasy pan for

easier

cleanup inevitably sets off our smoke detector, as does roasting

vegetables under the broiler. Solution: Learn the right doors and

windows to open when broiling to prevent the klaxon. Silver

lining:

You don't need to worry about your smoke detector running out of

batteries without you noticing.

This is far from an

exhaustive list, so I'm curious to hear from others who live in houses

smaller than the national average. What unconventional techniques

do you use to make tiny house living fun?

Anna has enjoyed her Canon

Powershot SX20 over the

last two and a half years, but the camera finally gave up the

ghost. Dirt has caused an intermittent lens error for most of the

camera's life. Usually, we can simply do a hard reboot and the

camera starts working again, but this time around none of the recommended

tricks solved the problem.

We plan to see if a camera

repair shop can do any better next time we're in the big city, but in

the meantime, we decided to upgrade our high-tech camera to a Nikon

Coolpix L810. Until

the L810 arrives, my Nikon

Coolpix L22 will be the

primary blog camera.

The L22 often outperformed the Canon in picture quality, even though it

lacked the supermacro features and extensive zoom, and the price and

size are both very reasonable. We hope the Nikon Coolpix L810

will be an upgrade in all departments.

A long, gentle rain over

Sunday and Monday has increased the lushness factor of our farm by

50%. I wanted to give you an extensive farm-tour, but I'm working

with one hand tied behind my back with our current

camera situation.

(Life without supermacro is tough.) So, instead, I'll just tell

you that the first of the summer vegetables (beans and cucumbers) are

up, the rye is ready to be cut, and the perennials are growing like

crazy.

The strawberry beds are

finally white with blooms, and the first fruits are being set.

Other perennials that already have little berries swelling include nanking

cherries,

gooseberries, blueberries, and even one of the red currants we planted

this spring.

The peaches are bursting

out of their faded flower wraps and will soon be big enough to thin. I can't tell yet

whether the apples are hanging onto their fruits this year or not, but

I have high hopes.

And it looks like this

will be the first year we'll enjoy iris flowers. Our polyculture

of irises with thyme seems to be working pretty well --- the trick will

be whether the tall iris leaves start to outcompete the low herb now

that they're well-rooted. This is one of my attempts to include a

few more flowers in the garden without feeling the space is entirely

wasted.

Finally, the woody

plants are starting to yearn for another round of weeding. This

week, I'll be torn between prepping 31 beds for the big frost-free,

spring planting on May 15, and getting a head-start on the weedy, woody

perennials. According to Michael

Phillips, the trees

will be be putting out a new flush of feeder roots soon once they hit a

lull in leaf growth, and I definitely want them to be weeded and

mulched down again before then.

Thanks for all the comments on my Harbor

Freight tech support frustration I posted about last week.

I tried calling today but

this time I used Edith's suggestion of hitting zero a few times and it

worked! I talked to a real person who was nice and took less than

5 minutes to figure out the problem and start the process to ship out

the missing hardware. Not

sure why that option was not listed in the menu choices at the start of

the call but I'm more than pleased to get this resolved.

If you're changing over

from Langstroth hives to Warre hives, you're stuck with a

conundrum --- should you buy all new equipment, or can those Langstroth

boxes be cut down and turned into Warre hives? I decided to give

the latter a try since I was one Warre box short of having equipment on

hand for our new package of bees.

We actually have the

parts for multiple Langstroth boxes that were never even put together,

so I decided to use those for my experiment. Step one was to cut

two of these pieces to the length of the Warre hive (13.75 inches) and

two pieces to that length minus twice the thickness of the wood (12.25

inches). If you'd like to avoid my mistake, which produces four

bee-worthy holes per box, make the longer sides be the pieces without a

rabbet (indentation for the frames to rest on). The photo above

shows what happens if you disregard that advice.

Speaking of the rabbet,

Warre hives require a smaller indentation there than Langstroth hives

do. Assuming you're cutting down a Langstroth deep, you have

plenty of wiggle room in the depth department, so mark your rabbet to

3/8 of an inch and cut off the extra wood. While you're at it,

cut enough wood off the bottom of each side so that your box is 8.25

inches tall.

Then it's just a matter

of screwing the sides together. Be sure to use pilot holes and

three screws per side. And do try to cut more exactly than I did

the first time around (shown above) or your bees will spend masses of

time propolizing all the holes. (I whittled off the longer sides

until they matched up, but next time I'll have Mark do the cutting.)

To be honest, this box

is just a stop-gap measure since the new Warre hive I've ordered is

likely to arrive after our

new package of bees

does. And I suspect I'll keep buying most of the parts for

new hives since top bars, screened bottoms, and roofs feel past my

skill level. However, saving $40 per box by cutting down a

Langstroth deep that would otherwise be collecting dust in the barn

seems like a good deal if it only takes me half an hour to construct

--- sounds like a good compromise between my wish to make all of our

equipment and the reality that woodworking is far from my strong point.

The Stihl

FS-90R trimmer did a

great job cutting the latest Rye

cover crop experiment at

the base,.

We made short work of it with

Anna following behind me with a rake to bring back the few plants that

fell in the aisle.

Last spring, we

harvested 9 buckets of worm castings from the bin at the parking area (but figured the yield was

only two net buckets since we'd initially seeded the bin with 7 buckets

of worms plus mostly-composted castings). This year, we got 6

buckets of excellent castings out of that bin. If we'd been

desperate, we probably could have harvested another 4 or 5 buckets, but

I figured castings that are still full of worms were best pushed to the

side to seed the next year's crop. There is also about a quarter

of a bin of uncomposted manure that I'll add to the worm side before

filling the rest of the bin back up with manure in preparation for next

year's crop.

Last spring, we

harvested 9 buckets of worm castings from the bin at the parking area (but figured the yield was

only two net buckets since we'd initially seeded the bin with 7 buckets

of worms plus mostly-composted castings). This year, we got 6

buckets of excellent castings out of that bin. If we'd been

desperate, we probably could have harvested another 4 or 5 buckets, but

I figured castings that are still full of worms were best pushed to the

side to seed the next year's crop. There is also about a quarter

of a bin of uncomposted manure that I'll add to the worm side before

filling the rest of the bin back up with manure in preparation for next

year's crop.

Meanwhile, I delved into

one of the closer-to-home worm bins, and was delighted to see much more

worm action than I'd

reported in early spring. I now think that the

issue with these bins was partially lack of water (which I've since

corrected by leaving the lids open during a few storms), but was also

simply lack of time. Seeding

worm bins in early fall doesn't give the worms time to do much

before winter puts activity on hold. In addition, I think that

worm bins get better after they've been in place at least one summer

and have accumulated all of the partner microorgnisms and invertebrates

that pre-digest manure for the worms. The parking-area worm

bin certainly has a much more diverse array of inhabitants, with my

harvest turning up hatched snake eggs, black soldier fly exoskeletons,

and an array of unidentified critters.

The castings from the parking

area bin are all going to potted plants --- topdressing the citrus and

potting up seedlings and cuttings. In a perfect world, I'd leave

the close-to-home bins alone since the worms are laying eggs and will

soon be experiencing a population boom. However, I need that aged

manure for the garden, so I'm carefully shoveling out the untouched

manure and pushing the worms (and eggs) to one end, then we'll fill

these bins back up once the floodplain is in shape for hauling manure

in. If all goes well, by this time next year, we'll have at least

24 buckets of worm castings to spread around the farm.

The castings from the parking

area bin are all going to potted plants --- topdressing the citrus and

potting up seedlings and cuttings. In a perfect world, I'd leave

the close-to-home bins alone since the worms are laying eggs and will

soon be experiencing a population boom. However, I need that aged

manure for the garden, so I'm carefully shoveling out the untouched

manure and pushing the worms (and eggs) to one end, then we'll fill

these bins back up once the floodplain is in shape for hauling manure

in. If all goes well, by this time next year, we'll have at least

24 buckets of worm castings to spread around the farm.

The current

worm bin design has 2

flaws that I hope to fix on the next generation of bins.

Using a sheet of plywood for

the lid seems like it won't last much more than a few years before it

warps beyond the comfort level and the hinge placement makes for a long

stretch to reach the other side.

I'm thinking of cutting the

lid area in half and hinging them on the sides with more of a steeple

shape so most of the rain can run off while some of it can be channeled

inside depending on the dryness level. Maybe a sheet of thin roofing

tin with a wooden frame for support would stand the test of time?

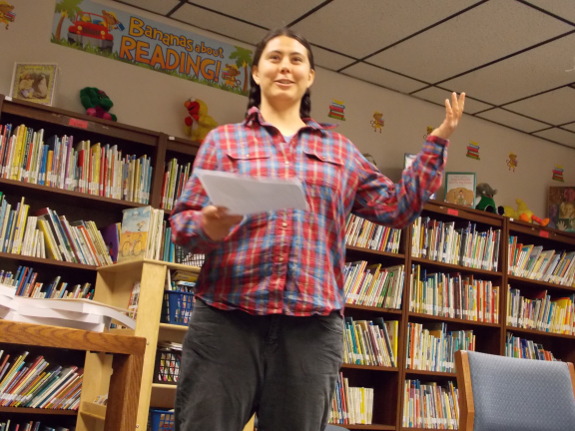

There are a few people

in my life I just can't say no to, so when our

local librarian asked me to give a talk to their Friends of the Library

group, I hemmed and I hawed, but I finally agreed. I didn't

announce it here because I figured a smaller group would be less scary,

but

Mark did record the audio to share with our readers after the

fact.

The sound quality is low

because the only electrical plug

was at the back of the room, but some of you might enjoy listening

anyway. You can either download the file (on the large side) or

listen below:

Sorry, long distance

readers don't get free Egyptian onions, nor do they get to partake of

the amazing spread the library patrons brought to share. But

maybe you'll still get a kick out of hearing me proselytizing about no-till

gardening.

Edited to add: Roland did some fancy computer work and filtered out most of the obnoxious buzz, so the file should now sound much better. Thanks, Roland!

I've been getting our lawn

mower blades from the same place for the last 4 years.

Every time I order from Yardpartsexpress.com the right blade is delivered the

next day for regular UPS shipping charges.

I haven't mentioned this

in a couple of years, so new readers might be interested in learning

about how foundationless frames

help deter varroa mites. The absence of

foundation can also help promote the health of your bees since

chemicals are often embedded in the beeswax that's used to make

foundation. The infrastructure to help bees build

regimented combs of honey without frames of foundation is generally

referred to as a top bar.

Now that you know why you might choose top bars,

let's talk about the specific frame Mike was asking about. The

photo at the top of this post shows the top bars that came with our

premade Warre hive. You can get these for $1.50 apiece at

Beethinking (or at

least I think you can --- that's where ours came from in 2012, although

the picture on their website shows a different design). Even

though the top bar is only a tiny piece of wood, I think these are

worth buying if you can afford them since they're rather complex to

build yourself, and this design definitely helped our bees create

beautiful, straight comb with no foundation. We did modify

the box slightly to use pins instead of nails, though, in order to make

the frames easier to move.

Now that you know why you might choose top bars,

let's talk about the specific frame Mike was asking about. The

photo at the top of this post shows the top bars that came with our

premade Warre hive. You can get these for $1.50 apiece at

Beethinking (or at

least I think you can --- that's where ours came from in 2012, although

the picture on their website shows a different design). Even

though the top bar is only a tiny piece of wood, I think these are

worth buying if you can afford them since they're rather complex to

build yourself, and this design definitely helped our bees create

beautiful, straight comb with no foundation. We did modify

the box slightly to use pins instead of nails, though, in order to make

the frames easier to move.

I've

seen (and used) various other top bar options, and one of these might

be better for you, depending on your situation. If you're using a

Langstroth hive, it's simplest to modify the frames that come

with the hive.

You can nail the wooden strip that's usually used to hold foundation on

vertically instead of horizontally, but I didn't have luck with getting

bees to build from that option. Instead, thin strips of

foundation at the top of each frame worked well for me. (Of

course, you still end up with a bit of foundation in the hive with this

method, but much less than if you filled the whole frame with

foundation.)

I've

seen (and used) various other top bar options, and one of these might

be better for you, depending on your situation. If you're using a

Langstroth hive, it's simplest to modify the frames that come

with the hive.

You can nail the wooden strip that's usually used to hold foundation on

vertically instead of horizontally, but I didn't have luck with getting

bees to build from that option. Instead, thin strips of

foundation at the top of each frame worked well for me. (Of

course, you still end up with a bit of foundation in the hive with this

method, but much less than if you filled the whole frame with

foundation.)

This image, through a viewing

window up into a horizontal top-bar hive, shows the V-shaped top bars

that are perhaps the simplest to construct if you're making your

own. The

package we installed in our top bar hive absconded, so I can't tell you whether

our bees would have built off these top bars, but I believe most

top-bar beekeepers use a similar design with good results, so it's

worth a try.

This image, through a viewing

window up into a horizontal top-bar hive, shows the V-shaped top bars

that are perhaps the simplest to construct if you're making your

own. The

package we installed in our top bar hive absconded, so I can't tell you whether

our bees would have built off these top bars, but I believe most

top-bar beekeepers use a similar design with good results, so it's

worth a try.

No matter what kind of

top bar you use, the idea is pretty simple. You want to make the

bottom of the bar come to a point to tempt your bees to draw out comb

in a straight line. And you want to allow the right amount of

space between frames (if you're using a vertical hive like a Warre hive

or Langstroth hive) so that bees can pass through but won't be tempted

to fill in the gap. In contrast, with a horizontal top-bar hive,

you want to have the top bars completey fill the space so that bees

don't end up under the roof. Those two design points in place, a

top bar can be pretty much anything you dream up.

We had our new friend Waylon

help out with some chicken care today.

It might be a few more years

before he's ready to apply for the intern program, but he seems to have

an aptitude for poultry that could give him an advantage over other

applicants..

Daddy gave me Jay

Walljasper's The

Great Neighborhood Book a few years ago on the

understanding I'd review it on our blog. Unfortunately, there

weren't enough plants and non-human animals in the book to move it out

of my slush pile, so it sat there until our

failed intern experiment got me thinking that I

needed to learn more about community-building.

Daddy gave me Jay

Walljasper's The

Great Neighborhood Book a few years ago on the

understanding I'd review it on our blog. Unfortunately, there

weren't enough plants and non-human animals in the book to move it out

of my slush pile, so it sat there until our

failed intern experiment got me thinking that I

needed to learn more about community-building.

It turns out I could

have sucked the marrow out of The

Great Neighborhood

book in just a few hours, but the long wait was no big loss because

there is, unfortunately, absolutely nothing for rural dwellers in the

whole text. In fact, Walljasper is one of those folks who

believes that cities are the only solution to environmental problems (a

stance I tend to disagree with since the extra car use in rural areas

can easily be offset by working online and growing your own food).

Anyway, rants aside, I

love the idea of turning neighborhoods into interconnected villages,

and I wish someone would write a similar book for the

countryside. While I'm waiting for The

Great Neighborhood: The Rural Edition, a few of Walljasper's tips

might carry over to our habitat. For example, a neighborhood

listserv (or, in this day and age, perhaps a facebook page) could help

people communicate more, and Mark's always wanted to get folks on our

little road together once a month for a potluck.

On the other hand, if

you live in a suburb or urban area, I highly recommend at least

flipping through this easy-to-read book to get ideas for turning your

neighborhood around. Learn how putting a bench in front of your

house or waving at people passing by can turn up new friends, decrease

crime, and slow traffic. Walljasper might change your mind about

dogs (good for neighborhoods) and wide roads (bad for neighborhoods),

and the case studies will definitely inspire you to get out there and

make change.

Do you have a suggestion

for a more rural-based community-building book? I suspect someone

out there has done as good a job with that topic as Walljasper did with

the city neighborhood.

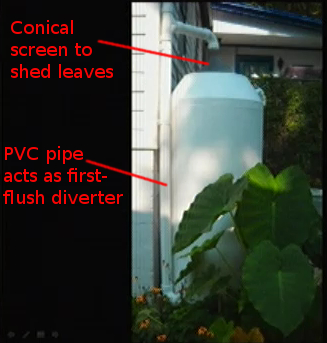

We installed gutters last

year, but have not got around to diverting all the water.

I found this baby snapping

turtle in our biggest puddle.

Anna thought about moving him

to the new

pond, but got concerned

he might be too small to climb over its plastic walls. We ended up

moving him to a more friendly puddle with no foot traffic.

The only downside of Swarm

Traps and Bait Hives

by McCartney Taylor is the price --- $6.99 for the ebook or $16.16 for

the paperback. As you've probably noticed, I price ebooks of this

length at 99 cents, and I don't make print books available because I

figure no one would want to pay $20 for a copy of Incubation

Handbook,

for example. However, I went ahead and bought Taylor's paperback

because I wanted something I could easily work from, and figured I'd

likely lend the text to friends once I'm done.

The only downside of Swarm

Traps and Bait Hives

by McCartney Taylor is the price --- $6.99 for the ebook or $16.16 for

the paperback. As you've probably noticed, I price ebooks of this

length at 99 cents, and I don't make print books available because I

figure no one would want to pay $20 for a copy of Incubation

Handbook,

for example. However, I went ahead and bought Taylor's paperback

because I wanted something I could easily work from, and figured I'd

likely lend the text to friends once I'm done.

And I wasn't

disappointed. After an hour perusing the elegant and

well-written interior of this 50-page book, I was itching to go out and

build a swarm trap. I'll write some followup posts once I've

created my first box, but for now, here are some tips to get you

started:

- Leave your swarm traps up between a couple of weeks before you usually see swarms (probably April around here) until about July.

- The best swarm trap is dark inside,

has an entrance hole near the

bottom about 1.5 to 2 inches in diameter, includes frames with a bit of

old wax on one or more, and has a capacity of around 10 gallons.

An 8-frame or 10-frame Langstroth deep with a top and bottom screwed on

and a hole in the side makes an instant swarm trap.

- Lemongrass oil vastly increases your chances of catching a swarm. (I wonder if lemon balm would work as well? I recall watching a swarm of ants when I was a kid and being struck by the fact they smelled exactly like lemon balm.)

- If you include an attractant (like lemongrass oil), you can hang swarm traps as low as six feet off the ground, but do plan to put them in full shade. Good locations include along fencelines, rivers, and treelines, under a lone tree in a field, or on a lone building in the country --- bees use all these features as landmarks, so they spend more time there than in other areas.

- Check your swarm box at least twice a month. (More often is better.) You know a swarm has moved in if you not only see bees flying in and out but also notice that workers are bringing pollen inside. Once your box is occupied, visit it at dusk, plug the hole, and bring it to your apiary, where you can transfer the frames to a new hive and then put the swarm box back in its trap location.

Taylor reports that you

should have at least a 20% chance of catching a

swarm if you make one bait hive, but he recommends building several so

you can test different locations. We'll probably just start with

one since we're at the height of garden season right now, and I want to

build a slightly more complex version to make transfer to a Warre hive

easy. More on my rendition of Taylor's design in a later post.

We cobbled together our first

swarm

trap from some old hive boxes.

It took about an hour with

Anna measuring and me cutting and drilling.

When I planted our first set

of tender vegetables at the end of April, the long-term forecast looked

frost-free. But a freeze slipped up on us, so Sunday afternoon I

rushed around and put row covers over the strawberries and seedling

corn, beans, and squash.

When I planted our first set

of tender vegetables at the end of April, the long-term forecast looked

frost-free. But a freeze slipped up on us, so Sunday afternoon I

rushed around and put row covers over the strawberries and seedling

corn, beans, and squash.

The last frost in our

neck of the woods is awfully likely to wipe out young fruits on apples

and peaches, but I've figured there's not much you can do there except

hope. Luckily, these fruits usually don't

get damaged until at least 28 degrees, and our (hopefully) last

freeze of the year clocked in at a mere 32 degrees, leaving patchy

frost on the ground but no nippage higher up. I'm especially

pleased to see that our hardy kiwi wasn't harmed this year --- the

leaves have been nipped every spring to date, and we've seen no fruits

as a result, so I'm hopeful 2013 will be the year the vines have enough

vigor to bloom.

Meanwhile, concern about

the frost prompted me to test a hypothesis I have --- that the reason

basswood trees bloom erratically is simply because the flowers get

frost-nipped most springs just like many fruit trees do. Sure

enough, the bloom buds are already in place on the basswood tree, but

since our recent freeze was so light, my hypothesis will have to wait

until another year for a test. That's just as well since

non-nipped basswood flowers will make this the first year since 2010

that our farm will be enjoying this top-notch

June nectar flow.

Technically, we'll be

frost-free as of tomorrow, but I can use any weather magic you all have

on hand to ensure that will be the case. The blackberries aren't

even blooming and we usually enjoy a blackberry winter....

It cost 15 dollars to upgrade

the Heavy Hauler so it can hook up to a trailer ball.

A scrap piece of 1x3 made the

installation smooth and painless.

Backing up is now a dream

compared to the other pivot point.

Our top-bar hive has been sitting in the yard

vacant ever since our

package absconded from it this time last year. I've been leery of

giving the structure another try because the Warre hive is working so well, but

reading Swarm

Traps and Bait Hives

suggested another possible use for the top-bar hive --- catching swarms.

Our top-bar hive has been sitting in the yard

vacant ever since our

package absconded from it this time last year. I've been leery of

giving the structure another try because the Warre hive is working so well, but

reading Swarm

Traps and Bait Hives

suggested another possible use for the top-bar hive --- catching swarms.

The first step in the

top-bar-to-swarm-hive conversion involved looking inside and cleaning

the hive up. In the process, I discovered that our top-bar hive

wasn't entirely vacant  after all. An ant

colony was living in one corner, a wasp had laid eggs in a new paper

nest, and what appeared to be a mouse nest covered most of the hive's

bottom. Once I pulled out the "mouse nest," though, I discovered

that it was actually a bird nest, perhaps from the miniscule Blue-gray

Gnatcatchers that make such a racket around the edges of our yard in

the spring. There were no eggs present in the bird nest, so I

figured it was okay to make the birds find a new home, and I had no

qualms about doing the same for the wasp. (I left the ants alone

since it seems like bees and ants can coexist.)

after all. An ant

colony was living in one corner, a wasp had laid eggs in a new paper

nest, and what appeared to be a mouse nest covered most of the hive's

bottom. Once I pulled out the "mouse nest," though, I discovered

that it was actually a bird nest, perhaps from the miniscule Blue-gray

Gnatcatchers that make such a racket around the edges of our yard in

the spring. There were no eggs present in the bird nest, so I

figured it was okay to make the birds find a new home, and I had no

qualms about doing the same for the wasp. (I left the ants alone

since it seems like bees and ants can coexist.)

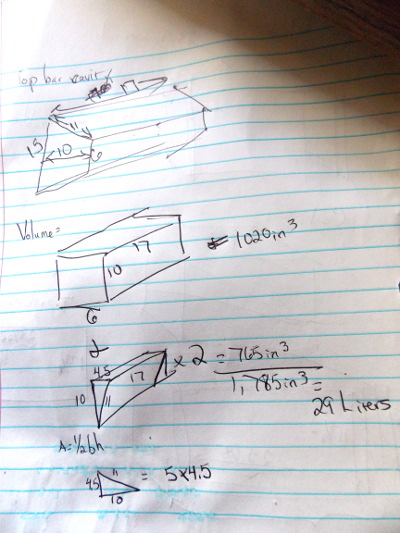

Next, I considered the cavity

size of the top-bar hive. The instructions I'd read last year

recommended moving the follower boards in so that only twelve top bars

were included in the bees' initial living area. However, my

calculations suggest that leaves a cavity volume of only 29 liters,

while 40 liters is the optimal size bees look for when choosing a new

home. So I moved the follower boards to the ends of the hive and

doubled the interior space.

Next, I considered the cavity

size of the top-bar hive. The instructions I'd read last year

recommended moving the follower boards in so that only twelve top bars

were included in the bees' initial living area. However, my

calculations suggest that leaves a cavity volume of only 29 liters,

while 40 liters is the optimal size bees look for when choosing a new

home. So I moved the follower boards to the ends of the hive and

doubled the interior space.

One hypothesis about why

our bees absconded last year was that the hive was getting too hot in

the sun, so Mark put in a max-min thermometer to see what temperatures

the colony would have been dealing with. Swarm

Traps and Bait Hives recommends locating these

structures in full shade for best chances of catching bees, and more

shade does seem to be merited since the top-bar hive reached 110

Fahrenheit last year. We may move the structure elsewhere now

that it's been reinvisioned as a swarm trap.

Finally, I smeared some

lemon balm around the inside of the top-bar hive. My lemongrass

oil hasn't arrive in the mail yet, but my gut says lemon balm will work

just as well as a swarm attracter. We'll just have to wait and

see.

The ATV

was beginning to have trouble starting from a cold stop.

I knew the previous owner

used fuel with ethanol, and it was in his garage for at least a few

weeks like that, which lead me to suspect that as the problem.

Start is a fuel system revitalizer made

by the people who make STA-BIL. It took a few days before I

started seeing results, but it seems to have improved starting.

I was weeding the mule garden

about 15 feet away from the hive when the bees decided to swarm, but I

missed the mass flight. I had walked off to the barn to get

another tool, and when I returned I heard a great buzzing overhead and

to my left. By the time I got my eyes turned around, the bees

were out of sight.

I was weeding the mule garden

about 15 feet away from the hive when the bees decided to swarm, but I

missed the mass flight. I had walked off to the barn to get

another tool, and when I returned I heard a great buzzing overhead and

to my left. By the time I got my eyes turned around, the bees

were out of sight.

Luckily, they hadn't

flown far. In fact, they'd settled into the honeysuckle on the

exact same sassafras last

year's absconded package settled on before flying away.

That means the bees would have been right beside our top-bar-hive-turned-swarm-trap...but I had talked Mark into

helping me move that structure behind the barn the day before.

Oops.

We were woefully

unprepared for a swarm, despite the fact that I've been blogging about

little else all week. I really should have known it was coming,

not just because this is the swarming time of year, but also because

the Warre hive's three boxes were getting pretty congested.

I took the top two

photos up through the screened bottom the morning before the swarm

left, catching the back (left) and front (right) of the hive, and it

was evident that the cluster of bees was humongous at that time.

That's why the second photo is out of focus --- the bees were hanging

all the way down to the floor. The hive had been a bit like this

(although not quite so extremely crowded) for a couple of weeks, and if

I'd wanted to slow down swarming behavior, that would have been a good

time to nadir a fourth body into my

hive.

However, I didn't have

the spare equipment on hand because the place I ordered from is swamped

and hadn't mailed my hive bodies two weeks after I paid for them.

(I haven't figured out how to make top bars yet, so I couldn't just

make my own homemade hives.) We do have a fourth hive body, but

I'd been saving that box in case the package

shows up before the new hive parts do. Which is all a long

explanation for why I let the bees get so congested that they swarmed

before they need to have. All of that said, Warre theory is that

you want your bees to swarm to break the pest and disease cycle, so all

I would have been doing with management is slowing down the swarm, not

preventing it.

(As a side note, it's

interesting to compare the inside of the original hive the morning

before (top photos) and the afternoon after the swarm (bottom

photos). The comparison gives you an idea of how much of the

hive's population leaves with the swarm and how much stays home to tend

the worker brood and baby queens. Generally, about 10,000 workers

and drones (two-thirds of the population) leave, but they're soon

replaced by workers hatching out in the old hive.)

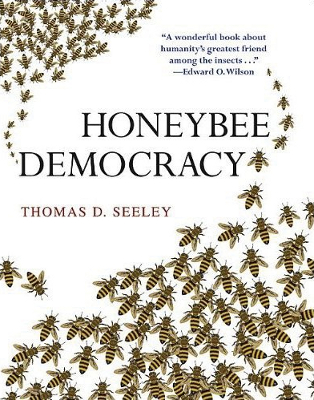

Anyhow, mea culpa's

aside, I had a swarm on my hands and I didn't want to lose it. My

first hope was that the bees would find my swarm trap even though the

structure was now a couple of hundred feet away, but I soon discovered

that the bees were considering another site instead. How could I

tell? Well, I've spent the last week reading Honeybee

Democracy (which I'll review here after finishing the last couple

of chapters), and thus had discovered a lot about the behavior of bees

in swarms.

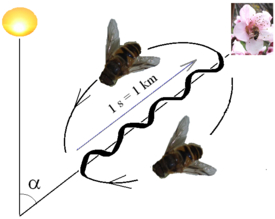

It turns out that after

a swarm leaves the hive, they always settle just like mine did, not far

from the parent hive. At that point, an astonishing exercise in

consensus decision-making occurs. Most of the bees hang out

around the queen, but 300 to 500 workers peel off to survey the

surrounding 30 square miles in search of nest sites. If a worker

finds a potential home, she returns to the swarm and performs a waggle

dance (shown below) to inform her cohorts of the location. Other

bees go and check it out, dancing about the site if they like it or

ignoring it if they don't, and eventually enough bees have settled on

one location that the swarm figures they've found what they're looking

for. At that point, they all take off and relocate to their new

home.

This all sounds a bit

esoteric, but the truth is that once you have a swarm in front of you,

waggle dances are extremely obvious and easy to decipher. After

only a few seconds of observation, I was able to find two workers

dancing about the same location, which I videoed above. The

dance's angle away from vertical shows the angle the actual location is

away from the sun, and the length of time the bee wiggles her butt

shows how far away the site is. Using this data, I was able to

tell that our bees had only found one good site so far, and that it was

two miles away to the southwest --- definitely not my swarm trap.

This all sounds a bit

esoteric, but the truth is that once you have a swarm in front of you,

waggle dances are extremely obvious and easy to decipher. After

only a few seconds of observation, I was able to find two workers

dancing about the same location, which I videoed above. The

dance's angle away from vertical shows the angle the actual location is

away from the sun, and the length of time the bee wiggles her butt

shows how far away the site is. Using this data, I was able to

tell that our bees had only found one good site so far, and that it was

two miles away to the southwest --- definitely not my swarm trap.

My first thought was to

set up a potential hive on the other side of the yard, smear it with

lemon balm, and hope my bees would find the site. Then I changed

my mind and figured I'd set up the potential hive much closer to the

swarm tree to ensure the bees found it. But half an hour of

observation showed that only one worker checked out the empty hive, and

she didn't even think it was worth crawling inside. (Scouts

looking for potential house sites go inside and measure the cavity

volume to ensure the hive is what they're looking for. When

visiting a good site, they'll spend over half an hour buzzing around to

check out the cavity from all directions.)

If we were going to lose

the swarm otherwise, it seemed worthwhile to try to catch it.

Huckleberry told me to lay out a white sheet underneath the swarm and

then cut down the tree to drive the swarm into a box (although I think

our spoiled cat might have mostly been thinking about napping in the

shade), but I got scared and called my beekeeping mentor (aka our

movie-star neighbor). More on the ensuing action in tomorrow's

post....

The Chevy S-10 truck can hold

20 five gallon buckets of horse manure.

I'm thinking of attaching a 5

inch board on each side to increase capacity to 40.

"Our hive cast

a swarm!! The

first one ever!! What do I do?"

Perhaps it was the

excess of exclamation points, but something told our

movie-star neighbor he should skip the advice and just come over to

lead the capture.

Our neighbor later told

us that this was the toughest swarm he'd ever

captured because of the masses of honeysuckle encircling the

bees. Mark had suggested we cut away the vines, but I was

terrified this swarm would be annoyed by the activity and leave just

like last year's package did. Luckily, our neighbor had a simple

solution --- spray the swarm liberally with sugar water so they'd stay

put, then clip those vines.

He also suggested we

smear peach leaves along the inside of the boxes

we were going to install the honeybees into. Since our neighbor

had just

bought some lemongrass oil on my recommendation, we also dabbed a few

drops of that fragrant substance on the inner walls of the hive as well.

"Are we going to scoop

the bees into a bucket?" I asked. (Imagine

this sentence uttered with the intonation of the classic "Are we there

yet?") We'd very carefully cut all of the vines underneath the

swarm, but left one in the middle to make the mass of bees easy to

shake. But into what?

My neighbor didn't like

the bucket idea, and planned to instead

levitate a hive body under the swarm and knock the bees directly into

their new home. Here's where Mark's ingenuity shone. "Why

don't we put a couple of brackets on the tree, add a board on top, and

then put the hive there?"

Nearly

as easily done as said! Too bad our hive was a cobbled-together

version of Langstroth and Warre equipment since we want the bees to

eventually live in the latter but have much more of the former on

hand.

It seemed to form a relatively solid container, though.

Nearly

as easily done as said! Too bad our hive was a cobbled-together

version of Langstroth and Warre equipment since we want the bees to

eventually live in the latter but have much more of the former on

hand.

It seemed to form a relatively solid container, though.

Unfortunately, the tree

grew at a bit of a slant, so there was a good

chance the bees would fall into the gap between the hive and the

trunk. Perhaps a bee book would make a good ramp to guide them in

the right direction?

Here's where activity

got heated and we stopped taking pictures (except

the last one below). Our neighbor and I suited up, I stood on a

bucket with a brush, and he stood on the ground with a hoe.

"On three, I'll yank

this vine and shake the bees into the hive, then

you start brushing any stragglers down," he ordered. "One, two,

THREE!"

Whoosh!

Bees were everywhere! Even though bees in a swarm are supposed to

be very polite, I was ultra-glad I'd donned a bee suit since I'm

positive I'd otherwise have ended up with several ladies stuck in my

hair. I put on the lid, then we stepped back and waited.

Whoosh!

Bees were everywhere! Even though bees in a swarm are supposed to

be very polite, I was ultra-glad I'd donned a bee suit since I'm

positive I'd otherwise have ended up with several ladies stuck in my

hair. I put on the lid, then we stepped back and waited.

At first, we thought

we'd been successful, but when I checked on the

hive just before dark, the swarm had reformed in the narrow gap between

tree and box. I guess our bee book wasn't as good of a ramp as

I'd

thought and the queen fell into the gap, then everyone else

followed. Downhearted, I figured the experiment had been a

failure, but by the next morning, I'd figured out a solution.

Mark and I headed out to

the swarm first thing the next day and I

sprayed all the bees I could reach with sugar water. Then Mark

gently

eased the second box away from the tree, figuring at least some of the

bees would adhere to the surface and end up dangling above the cavity

below. Sure enough, his gentle motion combined with my brushing

got at least half of the swarm into the lower box, then we pushed the

hive back

together.

This time, I was sure

we'd failed since bees nearly immediately began clustering between the

box and the tree again. But a few hours

later, the bees were streaming into the hive box instead. I can

only guess

that, at first, that gap smelled like queen, but as her scent

dissipated, the workers discovered the queen herself, ensconced in her

new hive.

Unfortunately, this happy

sight was not the ending of the story. On our neighbor's

recommendation, we left the hive in place that afternoon so any

stragglers would join their queen, and I went off-farm to monitor the

quality of our nearby river. It was a blazingly

hot day, reaching nearly 90 in the shade, and perhaps the heat was too

much for the bees (or they really wanted to live in that site

two miles away). Because when I came home, the hive was empty,

the swarm gone.

Unfortunately, this happy

sight was not the ending of the story. On our neighbor's

recommendation, we left the hive in place that afternoon so any

stragglers would join their queen, and I went off-farm to monitor the

quality of our nearby river. It was a blazingly

hot day, reaching nearly 90 in the shade, and perhaps the heat was too

much for the bees (or they really wanted to live in that site

two miles away). Because when I came home, the hive was empty,

the swarm gone.

So, we didn't catch our

first swarm after all, but I did get a lot of hands-on experience and I

feel much more confident that I'll know what to do next time.

I'll probably move the hive to a good location right away if we catch

another swarm, and I should definitely get our ducks in a row so we

always have extra equipment on hand for swarm catching.

Of course, catching

swarms is always chancy, so we'll continue to experiment with setting

up swarm

traps, the sooner

the better. Honeybee

Democracy explains

that the scouts who go out looking for a new homesite are usually the

hive's oldest foragers, which suggests they may be househunting on the

sly for weeks before they leave their old home (meaning that a swarm

trap set up the day before a swarm emerges may be too late). And

even though I haven't read any data to this effect, I also wouldn't be

surprised if honeybees preferentially choose new house sites further

from their home colony, since they'd then have less competition for

resources and less chance of catching pests and diseases. Perhaps

bees would be most likely to move into a swarm trap at the parking

area, a third of a mile from our other hive?

A scrap piece of decking board wedged and secured like above should be enough to prevent any future unexpected dumping in the middle of hauling.

Even though I've spent

all week talking about bees, most of my efforts have

been in the garden. The elongated spring has put us behind where

we were in years past, but this week turned into summer, prompting me

to play catch up.

First on the agenda ---

planting out everything that has been waiting in the wings until our

last chance of frost passed. Thirty

beautiful tomatoes are now in the ground, all but three gifts and two

homegrown Stupice started under quick

hoops. I had

sprouted some tomatoes inside, but the outside starts were vastly

larger and more vibrant, as usual, so the insiders went on the compost

pile.

Meanwhile, I planted the

first eight sweet potato slips. I generally set these out a few

at a time since they're homegrown and don't all root at

once. My garden plan tells me I only need four more slips to

reach this year's quota, but I think I'm going to plant some extras in

gaps in the forest garden as a summer cover crop. Sweet potato vines

definitely seem to produce at least as much biomass per unit area as

buckwheat does, plus the tubers make great gifts.

I stole a few hours away

from the vegetables to get the apples and peaches thinned. Thinning and pruning

are two of the most important factors in getting delectable fruits, but

are the most often overlooked by home gardeners. Sure, it's tough to pluck

five baby peaches off the tree for every one I keep, but I've learned

the hard way that peaches left too close together end up touching and

are more prone to brown rot infestations. In

addition, breaking off young fruits damaged by Oriental

fruit moths has

helped decrease that pest's population, and also prevents the tree from

pouring energy into fruits that will end up in the compost bucket due

to maggot frass in the middle. (Okay, I just cut out the bad

spots, but still.)

Thinning also helps

prevent the tree from breaking branches under heavy fruit loads, and

reduces your chances for biennial bearing. Finally, thinned trees

produce bigger, tastier fruits. I figure it's well worth the hour

I spent on our largest tree, and the few minutes on each smaller tree,

to get all of those benefits.

What didn't I have time

for this week? Weeding and mulching around seedlings planted

earlier in the year and catching those weeds in the woody perennials

before they get really rooted and hard to pull. Luckily, next

week begins the late May planting lull, so I should have time to catch

up in the areas I got behind on this week while playing catch up from

the weather.

Our front porch

is being attacked by carpenter bees!

I just found out they dig a

90 degree tunnel that can expand after each year of nesting.

Painting or varnish usually

prevents this kind of damage. I think we'll be using treated lumber for

any future porch projects.

As Everett once wrote

on his blog, voluntary simplicity is far from

simple. It's tough to wrap your head around why you might choose

to embrace simplicity in your life, and equally tough to figure out how

to be simple when mainstream society considers simplicity  close

to a

sin. On the other hand, when I achieve simplicity in bits and

spurts, I understand the importance of the measure --- the word

"simple" in

the phrase refers to the peace you feel when you've cut that cord to

consumer culture.

close

to a

sin. On the other hand, when I achieve simplicity in bits and

spurts, I understand the importance of the measure --- the word

"simple" in

the phrase refers to the peace you feel when you've cut that cord to

consumer culture.

Despite believing in the

philosophy, I haven't done much reading about simplicity because

writers like Thoreau

generally make my eyes roll. But when a copy of the Baltimore

Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers)'s Faith and

Practice: First Reading

(2012) fell into my lap, I flipped through the sections on

simplicity and found some helpful advice. Here's an example:

History has shown that when a

future outcome, however

noble, seems of greater worth than the human being before us, any

means, any atrocity, is possible.

History has shown that when a

future outcome, however

noble, seems of greater worth than the human being before us, any

means, any atrocity, is possible."We need to think of simplicity not as an impossible demand, but as an invitation to a more centered, intentional, and fulfilling Spirit-led life. Simplicity flows from well-ordered living. It is less a matter of doing without, than a spiritual quality that simplifies our lives by putting first things first.... This does not mean that life is to be poor and bare, destitute of joy and beauty. Each must determine...what promotes and what hinders the compelling search for inner peace...."

I'll close with one last

quote found in Faith and

Practice:

What do you think about

voluntary simplicity?

Thanks for all the comments on

last week's post about respecting

the load limits of a small truck.

Our conclusion is to be happy

with 20 buckets. The truck is over 20 years old, and she sometimes

creaks on turns with a full load, which is a message I'm getting load

and clear.

Apples are a magnet for

pests and diseases, and there are various responses to this

reality. Conventional growers just dose the trees with chemicals,

while organic growers tend to use less-noxious-but-still-problematic

sprays. Those

of us who eschew even the organic sprays, though, have to get a bit

more clever, and I start that cleverness off with variety

selection.

Our high-density-apple

planting gave me a

chance to try a lot more varieties than I could otherwise cram into our

core homestead, and I'm taking advantage of that opportunity to see how

each type of apple performs in our climate. The apple disease

that's been our biggest bugaboo in the past is cedar

apple rust, and I

tried to select only varieties that show resistance to the

fungus. Still, I've seen the pretty (but problematic) orange

spots on several of our new trees --- Sweet Sixteen, Grimes Golden,

Pristine (ironic, huh?), Mammoth Black Twig, one of our two Zestars,

and Summer Rambo. All infestations are light to moderate, so I'll

ignore it for now and consider ripping out these varieties if the

fungus seems to be unduly affecting the trees' growth in the future.

A new problem is woolly

apple aphid, which showed up on the last year's cicada

wounds on some of our older trees. Once I realized the white

fuzz wasn't a fungus, I stopped  being as concerned, since I'm

quite good at squishing bugs. Woolly apple aphids only become

really problematic when they get into the roots of the trees and cause

leaf yellowing, which may be the case in the Pristine leaves shown to

the left. (All of Pristine's neighbors have darker leaves, or I

would have assumed the yellowing was simply a nitrogen deficiency, but

the issue could also be due to something else I've yet to figure out.)

being as concerned, since I'm

quite good at squishing bugs. Woolly apple aphids only become

really problematic when they get into the roots of the trees and cause

leaf yellowing, which may be the case in the Pristine leaves shown to

the left. (All of Pristine's neighbors have darker leaves, or I

would have assumed the yellowing was simply a nitrogen deficiency, but

the issue could also be due to something else I've yet to figure out.)

Possible root damage

aside, I suspect the woolly apple aphids will be long gone soon.

I started noticing the white fuzz less than a week ago, and when I went

out to visit the trees Sunday, I saw mating ladybugs and eggs --- the

predator insects are on the job.

While we're on the topic

of aphids, it's worth noting that the woolly apple aphids weren't on

all the trees with cicada damage, just the Virginia Beauty. On

the other hand, our Yellow Transparent, Winesap, and Enterprise sported

a few curled leaves like the one above, which closer inspection showed

were full of fuzz-less aphids being tended by large black ants.

Once again, I'll let nature take its course here. I've never

known aphids to be more than a passing inconvenience in our diverse

garden.

More troubling is the

dead leaf tips like the one shown above, which I'm guessing is the

apple version of fire blight. As with cedar apple rust, I tried

to select only resistant varieties, but apparently Enterprise is more

prone to fire blight than the internet lets on.

I'm not sure what to think

about the few blackened leaves like the one shown to the left, which I

discovered on our Winesap. Ideas?

I'm not sure what to think

about the few blackened leaves like the one shown to the left, which I

discovered on our Winesap. Ideas?

In case you're keeping

track at home, all of this leaves just a few varieties completely

untouched by insects and disease so far this spring --- Liberty, the

dwarf Yellow Transparent, and Red Empire. So far, the following

varieties have set fruit --- Virginia Beauty, Liberty, Yellow

Transparent (the elder and the the younger), Enterprise, and

Pristine. I'll keep you posted on how the variety selection pans

out later in the year once we've seen how our trees hold up under their

various stresses.

This chicken

pasture gate got damaged

last year because it couldn't get out of the way from the golf cart

backing up at full speed.

The latest batch of chickens

from the incubator

are starting to get big enough to threaten our strawberry crop, which

is what motivated today's gate repair.

We plan to relocate them into

this pasture tomorrow if we can figure out an easy way to move the outdoor

brooder without shaking

the chickens too much.

Planting always seems like the most

pressing part of starting the summer vegetable garden, but equally

important is following up a week or two later to make sure the crops  are off to a good

start. This week, I'm taking a close look at each of our seedling

beds and:

are off to a good

start. This week, I'm taking a close look at each of our seedling

beds and:

- Taking off the cat-repellant covers.

- Thinning if necessary, then weeding and mulching around each seedling.

- Replanting individual plants (like beans) in gaps, or replanting whole beds that didn't come up due to cold soil or that got eaten by hungry early-spring critters.

Some no-till gardeners

start everything in pots and transplant to avoid this dance (and the

bare soil that goes along with it). But I prefer the

cat-weed-mulch-replant waltz to the potted-plant polka.

It only took about 10 minutes to get the outdoor brooder to the new pasture.

There's nothing like failing

the first time around

to make your ultimate success that much sweeter. That's right ---

the grafts on my frameworked

pears are healing up well, and the growth from the scionwood is

really taking off. I've been ripping off new shoots below the

graft union as I pass the trees by for the past couple of weeks,

ensuring all energy in each grafted twig goes into the new wood, and

now it seems to be time to take off the parafilm before the twigs burst

free of their wrappings.

There's nothing like failing

the first time around

to make your ultimate success that much sweeter. That's right ---

the grafts on my frameworked

pears are healing up well, and the growth from the scionwood is

really taking off. I've been ripping off new shoots below the

graft union as I pass the trees by for the past couple of weeks,

ensuring all energy in each grafted twig goes into the new wood, and

now it seems to be time to take off the parafilm before the twigs burst

free of their wrappings.

The Seckel scionwood I

grafted onto our Keiffer pear is doing an excellent job, with nine out

of ten grafts having taken. The other pear --- with an unknown

variety and Comice replacing the Orient twigs --- isn't as perfect, but

enough grafts have taken there to make the variety changeover.

I'm not quite sure what the

big difference is between the two trees, but I've got some

guesses. The most obvious factor that determined the success or

failure of a graft was the orientation of the twig I grafted onto ---

vertical watersprouts resulted in fast and prolific growth from the

scionwood (photo to the left) while horizontal twigs (photo above)

often failed to take or started growing late. All of the twigs I

used for the Seckel pear were waterpsprouts, while a lot more of the

other tree's twigs were horizontal.

I'm not quite sure what the

big difference is between the two trees, but I've got some

guesses. The most obvious factor that determined the success or

failure of a graft was the orientation of the twig I grafted onto ---

vertical watersprouts resulted in fast and prolific growth from the

scionwood (photo to the left) while horizontal twigs (photo above)

often failed to take or started growing late. All of the twigs I

used for the Seckel pear were waterpsprouts, while a lot more of the

other tree's twigs were horizontal.

I also forgot to dab a

bit of grafting wax on the ends of the scionwood on the non-Seckel

tree, so those twigs might have dried out (although they don't look

like it). And it's also quite possible the Orient pear just isn't

as amenable of a rootstock --- several of the grafts that did take on

that tree have yellowing leaves on the scionwood and haven't put out

much new wood, while the Seckel scionwood has shoots that are often

nearly a foot long. (This isn't a crazy idea --- some varieties

are incompatible with each other and will simply die if grafted

together.)

The tricky part will be

keeping track of which twigs are the new variety and which belong to

the rootstock, so I can slowly let the former take over the

latter. For now, the graft unions are very visible, but I suspect

they'll disappear into the wood before long. And maybe all this

vigorous growth means we'll enjoy pears of the new varieties by 2015?

We learned today that 6 bales of

straw is the ATV's limit.

The truck can hold 12, which

makes an even number of trips back to the barn.

Readers from last year will

remember when I was hauling 10 with

the golf cart, but had trouble getting up the hill and decreased it

to 7.

"Do you want to see the

cutest snake in the world?" I called down to Mark from the edge of the pig pasture. I had found a Rough

Green Snake (the first one I've ever seen!) in the lumber we'd stacked

for our new coop/pig shed, and Mark was very

willing to walk up the hill for the chance of a peek.

"Do you want to see the

cutest snake in the world?" I called down to Mark from the edge of the pig pasture. I had found a Rough

Green Snake (the first one I've ever seen!) in the lumber we'd stacked

for our new coop/pig shed, and Mark was very

willing to walk up the hill for the chance of a peek.

Which is all a long way

of telling you that we're back at work on the new pasture. Not

that things have slowed down at all --- the weeds are growing a mile a

minute --- but the broilers are too. We plan to keep about ten of

this year's first batch of broilers to replace our two-year-old layers,

and those pullets need somewhere to live between when the new

broilers get their

pasture and then they begin to lay. (At laying time, our new

flock will take over the quarters of our current laying flock, while

the old hens go into our tummies.)

In completely unrelated,

but delectable, news, we ate the first strawberry of 2013 on