archives for 03/2013

Unless March changes

personalities fast, we're going to run out of dry wood just a hair

before we run out of cold weather this year. While that sounds

like a bad thing, this past winter is the first one where I've kept the

trailer warm all the time (above 55 most days and above 40 most

nights!), so I consider it a major success.

Unless March changes

personalities fast, we're going to run out of dry wood just a hair

before we run out of cold weather this year. While that sounds

like a bad thing, this past winter is the first one where I've kept the

trailer warm all the time (above 55 most days and above 40 most

nights!), so I consider it a major success.

On the other hand, I

still don't know how much wood we burn per winter. As usual, we

went into the fall with our woodshed only partially full and had to

hire Bradley to cut up a huge standing

sycamore to make up

the difference. As we split the sycamore, we stacked

it directly on the front porch, so I never got a

measurement of the amount of dry wood we started with, either in cords

or as a fraction of the woodshed.

My goal is for the

winter of 2013-2014 to be the one where I actually get an idea for how

much wood we burn. To that end, we've already got a couple of

rows of walnut and box-elder in the back of the shed and will be

filling up the rest as soon as the floodplain becomes passable and the

golf cart comes back into action. I've really enjoyed having dry

wood all winter this year, so hope to fill the shed in time to have the

same luxury next year.

Want to increase your

success rate rooting cuttings? Try out these ten tips.

1.

Pay attention to time of day and time of year. As I mentioned in a

previous post, softwood,

greenwood, and hardwood cuttings are all taken at different times of

year, and different

plant species respond better to different seasons. If you're

taking softwood or greenwood cuttings, it's best to actually cut the

stems early in the morning when they're full of water and the air is

cool to minimize wilting.

2.

Skip the tips and blooms. The actively growing

tips of twigs usually have less stored carbohydrates, meaning that they

don't have as much food to draw on before they root and start

photosynthesizing again. Similarly, parts of trees that have

flower buds are going to be putting their energy elsewhere, so it's

best to choose areas that aren't flowering this year.

3. Stick

to the young.

Within the same tree or bush, certain parts of the plant act younger

than others. The so-called cone of juvenility shows the parts of

a tree that are the least mature biologically and most likely to root

easily. If you're trying to propagate lots of plants effectively,

it can be worth coppicing the parent plant so that it keeps putting out

new growth from within the cone. And even if you're selecting

cuttings from a mature tree, you can try to get more youthful

twigs by finding sprouts low and near the trunk.

3. Stick

to the young.

Within the same tree or bush, certain parts of the plant act younger

than others. The so-called cone of juvenility shows the parts of

a tree that are the least mature biologically and most likely to root

easily. If you're trying to propagate lots of plants effectively,

it can be worth coppicing the parent plant so that it keeps putting out

new growth from within the cone. And even if you're selecting

cuttings from a mature tree, you can try to get more youthful

twigs by finding sprouts low and near the trunk.

4.

Choose a good rooting medium. As long as it's fluffy

and able to hold a lot of water, most rooting mediums work pretty

well. Options include sand, peat, perlite, pine bark,

pumice, or sandy soil (and I generally use stump

dirt).

Remember that your plants don't need much fertility in their rooting

medium, although you will probably want to add some kind of fertilizer

once they're well rooted and are putting out new leaves.

5. Rooting hormones and

fungicides can help. I wrote a whole post

about rooting

hormones, some of

which include anti-fungicidal agents. I learned the hard way that

cuttings can be the perfect habitat for fungi, but I also suspect that

if you do everything else right, you might not need the chemical aids.

5. Rooting hormones and

fungicides can help. I wrote a whole post

about rooting

hormones, some of

which include anti-fungicidal agents. I learned the hard way that

cuttings can be the perfect habitat for fungi, but I also suspect that

if you do everything else right, you might not need the chemical aids.

6.

Wounding isn't always bad. Difficult-to-root

greenwood and hardwood cuttings are sometimes wounded near the base to

promote rooting. Wounding usually consists of scarring the bark

(but not the green cambium underneath) for half to one inch of the

base. Similarly, girdling can be used as a preconditioning step

for

rooting since it concentrates carbohydrates and hormones in small area,

which will make roots form better there.

7.

Keep cuttings moist but not wet. Softwood and greenwood

cuttings, especially, can dry out by losing too much water through

their leaves before they root. Steps as simple as partial shade

or a plastic bag over top of the pot can work, as can more complicated

misting setups used in nurseries. However, be aware that too much

moisture can be a problem, especially in the slower-growing hardwood

cuttings.

8. Some like it hot. Bottom heat can help

cuttings root...or it can prompt them to grow leaves, use up their

reserves too quickly, and perish. The most common use of heat is

beneath cuttings started outdoors in the winter. Next most common

is using heat to callus hardwood cuttings, which helps precondition

them for rooting. To callus cuttings, apply bottom heat for four

weeks, place in

plastic bag in

the dark at 50 degrees Fahrenheit, bury upside down in soil, sand, or

sawdust, or store in a warm, moist place for three to five

weeks. As you can tell from the various methods, it's probably

best to look up the species you're considering rooting before deciding

whether and how to callus.

8. Some like it hot. Bottom heat can help

cuttings root...or it can prompt them to grow leaves, use up their

reserves too quickly, and perish. The most common use of heat is

beneath cuttings started outdoors in the winter. Next most common

is using heat to callus hardwood cuttings, which helps precondition

them for rooting. To callus cuttings, apply bottom heat for four

weeks, place in

plastic bag in

the dark at 50 degrees Fahrenheit, bury upside down in soil, sand, or

sawdust, or store in a warm, moist place for three to five

weeks. As you can tell from the various methods, it's probably

best to look up the species you're considering rooting before deciding

whether and how to callus.

9.

Don't rush them out of the nursery. Softwood cuttings,

especially, often benefit from spending two years being babied before

being planted in their final location. And a few cuttings even

need supplemental light in the fall to prompt them to put out a growth

spurt and store enough energy to make it through the winter. If

you're going to go to all the trouble of rooting cuttings, don't let

them die on you after the roots form.

10.

Keep notes.

So many variables can affect the success or failure of your cuttings

that it's essential to write everything down so you can make changes

and try again. And don't feel bad if the techniques that work for

someone else don't work for you. Some varieties within the same

species root better than others, so you might not even be on an even

playing field.

| This post is part of our Reference Manual of Woody Plant Propagation

lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We helped our neighbor with

one of his audition tapes today.

I play the part of a

reluctant time traveler.

Frankie is playing a hard

nosed cop investigating a grizzly murder.

When I was younger I thought

the idea of time travel was fun and interesting...but these days I'm

inclined to label it dangerous and arrogant. In my opinion the best

time to be alive is NOW!

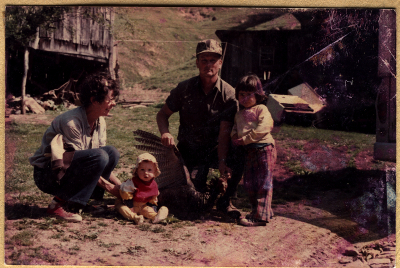

Most

of my memories of Silas come from that golden childhood period when I

assumed the stars (adults) revolved around the earth (me). In

other words, I really have no idea who he was. Except for the

obvious: farmer, father, salt of the earth, 'seng hunter, Gargamel.

Most

of my memories of Silas come from that golden childhood period when I

assumed the stars (adults) revolved around the earth (me). In

other words, I really have no idea who he was. Except for the

obvious: farmer, father, salt of the earth, 'seng hunter, Gargamel.

We Pacifist-hippie

offspring reacted to Silas's deer- and turkey-slaying with taunts of

the worst evil we could imagine --- likening him to the villain in the

Smurfs. And our good-natured neighbor played along, pretended to

chase us, and didn't mention our inconsistencies when we took home

turkey primaries to cut into quill pens.

By the time I was in

sixth grade, my family was still being drawn back to our long-sold farm

like moths to a flame. Silas and Onie's next-door house was a

safe resting place in our afternoon journeys. Mom made us bring

shoes --- "You don't have to wear them, but they have to fit in case

the car breaks down!" And sometimes she'd let us sit in the open

hatchback and bump our heels on the "dirt" (gravel) road along the

way.

We'd stop and gather

berries or persimmons, depending on the season, at favored roadside

spots, then I'd hunt minnows, scooping fish out of Silas and Onie's

creek with a five-gallon bucket. Back home, I poured the bucket

through a banged-up colander and let our city cats enjoy a country

feast as the fish flopped vainly in search of liquid air.

"You'll use all of our

fish up!" Silas's grandson

complained once. Adult-Anna agrees, and cringes even more at the

use to which we put our creek-caught crawdads, racing them down the

gutter into the storm-sewer. But at the time I was mourning the

loss of our own wooded acres, and Silas and Onie tacitly took my side

and let me treat their creek as my own.

During my fishing time,

Mom was sitting under the spreading catalpa, talking to Onie, who had

been a life-line during Mom's ten years on the farm, her own family 800 miles distant in Massachusetts. I would drop by the

shade tree, but soon became bored with adult conversation.

Instead, I ended up coaxing Silas's kittens out of the hole at the

bottom of the shed. There were always new kittens, but the farm

didn't become overrun because the road was nearby and lethal. I

remember the passion with which Silas condemned the speeding drivers,

and how easily he stroked the soft balls of fur.

Recently, Mom told me she

learned easy family affection from Silas, mentioning how struck she was

to find him holding three young daughters on his lap, when her New

England parents had kept touch to a minimum. Love --- so

complicated for most of us --- was simple for Silas.

Recently, Mom told me she

learned easy family affection from Silas, mentioning how struck she was

to find him holding three young daughters on his lap, when her New

England parents had kept touch to a minimum. Love --- so

complicated for most of us --- was simple for Silas.

Years earlier, when

my mother-to-be showed up and turned a rented store

into a honkey-tonk, Silas's teenage son was attracted to the

action. What did the newly-saved Silas do? Invited the

hippie to dinner, then crammed her into the car with his five kids and

wife and brought them all to the fair. The more the merrier.

My father's relationship

to Silas was built around work. I can only guess how Silas must

have taken this overeducated, idealistic, new farmer under his wing and

shared ideas as well as equipment. Silas went so far as to turn

Daddy on to the farm being auctioned off next door, which is how we

became neighbors when I was a few months old. Our right-of-way

through Silas's land felt like a daily handshake, rather than an

intrusion.

But you have to remember

that the world still revolved around me then. That I was intent

on capturing tadpoles in Silas's cows' water trough and oohing and

ahhing over the year's newest calves in the barn. I was thrilled

to drink from a dipper at the outside faucet, the water so cold it

almost hurt, and to sneak stale potato chips discarded from the factory

and trucked home to feed Silas's livestock.

The

truth is that I knew Silas only as the non-astronomers among us know

the stars. He was bright and memorable --- definitely part of

Orion's belt --- but I'd be hard-pressed to tell you a fact as simple

as the color of his hair before it went gray. All I knew was the

gestalt of Silas --- warm and strong and full of boundless love.

The

truth is that I knew Silas only as the non-astronomers among us know

the stars. He was bright and memorable --- definitely part of

Orion's belt --- but I'd be hard-pressed to tell you a fact as simple

as the color of his hair before it went gray. All I knew was the

gestalt of Silas --- warm and strong and full of boundless love.

And that's why, I

explained to my family, I couldn't begin to eulogize him on the

blog. Because all I really know is how much I miss him and how

his death has left a black hole in my life. And reminded me of a

time when the sun revolved around the earth...even though that sun had

kids and grandkids of his own. The more the merrier.

It's been cold lately, but the new Lectro heated kennel pad is keeping Lucy toasty.

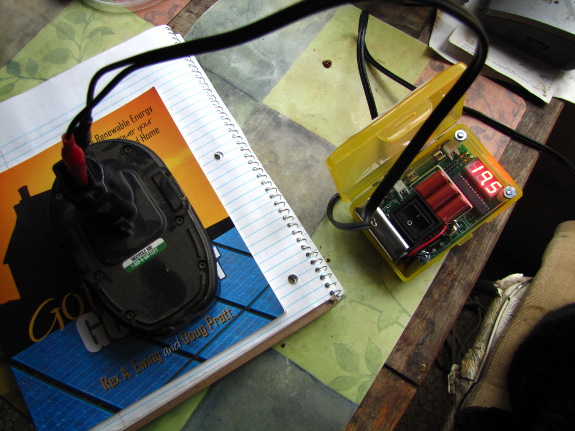

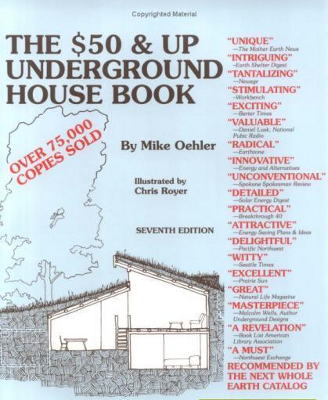

Brian sent me a copy of Got

Sun? Go Solar along

with a bunch of scionwood, and I skipped over some other items on my winter

reading list to

scarf it down. Rex A. Ewing and Doug Pratt have produced a quick

and easy read, with an explanation of the physics of solar that nearly

made me understand volts, amps, and watts. For that alone, the

book is worth a read if you're interested in solar, but I know I'll

have to delve much deeper to set up our tiny system.

Brian sent me a copy of Got

Sun? Go Solar along

with a bunch of scionwood, and I skipped over some other items on my winter

reading list to

scarf it down. Rex A. Ewing and Doug Pratt have produced a quick

and easy read, with an explanation of the physics of solar that nearly

made me understand volts, amps, and watts. For that alone, the

book is worth a read if you're interested in solar, but I know I'll

have to delve much deeper to set up our tiny system.

The trouble with the

book from a DIY point of view is that it's all about grid-tie

systems, which the

authors explain average around $20,000 to $25,000. (You can build

a grid-tie solar system for around $5,000, but that "low-end" audience

isn't who the authors are aiming for.) In that price bracket,

most people are going to be hiring installers to do all of the hard

stuff, so Ewing and Pratt left out nearly all the nitty-gritty.

Next on my list is Photovoltaic

Design & Installation for Dummies, which already appears to go

too far in the other direction --- assuming I'm going to become a

career solar installer putting in other people's multi-thousand-dollar

systems. Hopefully between the two sources, I'll come up with

enough information to get our tiny backup system off the ground at long

last.

We're still

experimenting with low-carb, tomato-rich recipes, and this one seems

like it's a keeper. A bit like a mix between quiche and lasagna,

it's won the approval of both Mark and B.J. so far, mostly because I

called it a "tomato pie".

Crust:

- 3 ounces cheddar cheese

- 1/4 cup grated parmesan cheese

- 3/8 cup all-purpose flour

- 1 tbsp sugar

- 1/8 tsp paprika

- 1/8 tsp salt

- 1 tbsp butter

- 1 tbsp water

Filling:

- 4 strips of bacon (baked with grease removed)

- 6 eggs

- 2/3 cup Greek yogurt

- 1 cup dried tomatoes (soaked in water, but with water poured off)

- 6 Egyptian

onion tops (green onions work too)

- 2 tbsp pesto

- 1 tbsp Hollywood

sun-dried tomatoes (optional)

- a bit of salt and pepper

- 1 cup mozarella cheese (in parts)

- a bit more grated parmesan cheese

Three hours before you

want to eat, soak your dried tomatoes in water to plump them up.

Go away for two hours, then start with the crust.

Mix the crust

ingredients in the food processor, then pat into the

bottom of a greased pie pan. Bake at 350 degrees for about 10

minutes, until cooked but not browned.

Meanwhile, bake the

bacon on a cookie sheet. Discard the grease,

then crumble the bacon into a bowl.

Pour the water off the

tomatoes and cut them up. (I used a food processor.) Then

add the tomatoes to the bacon along with the eggs, yogurt, Egyptian

onion tops (cut

into small pieces), pesto, Hollywood sun-dried tomatoes, salt, pepper,

and half a cup of the

mozarella cheese.

Pour the mixture into

the crust and bake at 350 degrees until the eggs set (with the time

depending on the size and depth of your dish). Then spread the

rest of the mozarella and parmesan on top and continue baking until the

cheese is brown (about 10 minutes).

Serves six hungry people.

In the interest of full

disclosure, I'm not really a believer in aquaponics. My gut

reaction is that it's not sustainable in most situations, so it annoys

me that it's being marketed as a green agriculture solution. Part

of this may be a blind spot because I don't like seafood (although I do

love fish ponds), but mostly it's just a knee-jerk reaction not to use

electricity to grow things if you don't need to.

In the interest of full

disclosure, I'm not really a believer in aquaponics. My gut

reaction is that it's not sustainable in most situations, so it annoys

me that it's being marketed as a green agriculture solution. Part

of this may be a blind spot because I don't like seafood (although I do

love fish ponds), but mostly it's just a knee-jerk reaction not to use

electricity to grow things if you don't need to.

On the other hand, Mark

has been intrigued by hydroponics ever since he was a kid, imagining

austronauts growing their food in water, and he loves the idea of a

more sustainable form of hydroponics. So I decided to hunt down a

book and read more about it.

Aquaponic

Gardening by Sylvia

Bernstein is a good beginners' guide to the subject. Even though

her arguments for sustainability didn't win me over, she did present a

very good explanation of how to set up an aquaponics system, including

a fascinating look at the ecology involved in growing fish and plants

together. The book has some flaws, but as best I can tell it's

the main contender in a very new genre. I'll write about some of

the top points in this week's lunchtime series, but I recommend

checking out Bernstein's book to learn more if you actually want to set

up an aquaponics system.

| This post is part of our Aquaponic Gardening lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We were walking to our car

today and I noticed a medium sized fish had somehow got his head stuck

in the hole of one of the cinder

block stepping stones.

It's possible he was trying

to feast on the many snails that have attached themselves to each block

and just got a little greedy going for the deeper ones.

We debated having him for

dinner, but decided he was too cute to eat.

When we first moved to the

farm, we teamed up with our movie-star neighbor in a chicken-share arrangement. I can't

say for sure whether our neighbor got enough eggs to make the deal

worthwhile, but we certainly benefited. In fact, our whole business was built around those free

chickens.

When we first moved to the

farm, we teamed up with our movie-star neighbor in a chicken-share arrangement. I can't

say for sure whether our neighbor got enough eggs to make the deal

worthwhile, but we certainly benefited. In fact, our whole business was built around those free

chickens.

So when B.J. turned up in our life,

lacking transportation, we decided to try the same sort of deal, this

time from the other side. He hunted down a quality used truck, we

bought it and paid the first year's insurance and fees, and he'll use

that truck to do some much-needed hauling for us. The truck-share

is born!

B.J. tells us her name

is Shelley, and, yes, it was love at first sight. Sure, they had

a long-distance relationship for the first couple of weeks, and B.J.

put in a lot of time talking Shelley's father around (and dated a few

other trucks in the meantime). But they finally got hitched and

are a hard-working team already. Congratulations, B.J. and

Shelley!

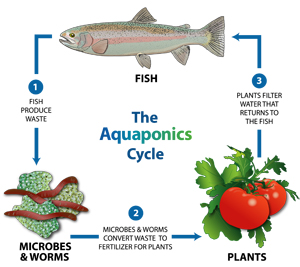

So, what is

aquaponics? The gist is that you keep a tank of fish, circulating

their water through a plant grow bed to clean the water and feed the

plants.

Although fish and plants are

what most people get excited about, an aquaponic system is actually

fuelled by a complex cycle including bacteria and worms. Fish

waste is full of ammonia, which is toxic to fish and which plants can't

use, but two types of bacteria convert that ammonia first to nitrites

(nitrosomona bacteria) and then into nitrates (nitrospira

bacteria). Plants love nitrates, so when you pump the fish-tank

water up to flow around your vegetables' roots, the plants quickly suck

up the nitrogen and return clean, aerated water to your fish.

Although fish and plants are

what most people get excited about, an aquaponic system is actually

fuelled by a complex cycle including bacteria and worms. Fish

waste is full of ammonia, which is toxic to fish and which plants can't

use, but two types of bacteria convert that ammonia first to nitrites

(nitrosomona bacteria) and then into nitrates (nitrospira

bacteria). Plants love nitrates, so when you pump the fish-tank

water up to flow around your vegetables' roots, the plants quickly suck

up the nitrogen and return clean, aerated water to your fish.

Meanwhile, compost worms in the plant grow bed are

cleaning up excess solids. Without these wrigglers, dead bits of

plant roots and larger particles of fish waste would build up  and require cleaning.

Luckily, compost worms can handle periodic inundations and do their

part to convert particulate matter into chemicals plants can easily

suck up.

and require cleaning.

Luckily, compost worms can handle periodic inundations and do their

part to convert particulate matter into chemicals plants can easily

suck up.

The fish, bacteria,

plants, and worms all work together to give each organism just the food

and environment it needs. I suspect this elegant, created

ecosystem is why aquaponics has won so many fans in permaculture

circles.

| This post is part of our Aquaponic Gardening lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

A few relevant details Anna

left out of this morning's truck share post.

The new truck is a 1993 Chevy S-10 four wheel

drive.

B.J. bought it off a trusted,

local mechanic for 1500 dollars who included a brief warranty.

Its got a Chevy Blazer engine

with just under 100 thousand miles. The 4 wheel drive won't go in 4

wheel low, but we can live with that. All 4 tires have at least 80

percent life left in them and it came with a nice bed liner.

With

the worst of the winter's cold over (we hope), I figure I have enough

data to finish up my ebook about the fridge

root cellar.

For a very low-work and low-cost option, it passed with flying colors,

using about 2 kilowatt-hours of electricity to keep a whole

winter's-worth of carrots in prime shape. During a power outage

that corresponded to a frigid spell, the interior dropped to 28 degrees

Fahrenheit (and I brought our carrots inside for a few days to protect

them), but otherwise the fridge root cellar stayed at the perfect

temperature all winter long.

With

the worst of the winter's cold over (we hope), I figure I have enough

data to finish up my ebook about the fridge

root cellar.

For a very low-work and low-cost option, it passed with flying colors,

using about 2 kilowatt-hours of electricity to keep a whole

winter's-worth of carrots in prime shape. During a power outage

that corresponded to a frigid spell, the interior dropped to 28 degrees

Fahrenheit (and I brought our carrots inside for a few days to protect

them), but otherwise the fridge root cellar stayed at the perfect

temperature all winter long.

Even though I think our

fridge root cellar is awesome, I want to round out my ebook with

overviews of some more traditional root cellars, so I gave my

movie-star neighbor a call. You'll have to wait for the ebook to

hear all about his root cellar that taps into a cave, but I'll regale

you with the other highlights of my visit below. (Meanwhile, the

offer's still open

to be included in the ebook if you have a root cellar or low-tech root

storage technique to share.)

Our neighbor has been

grafting new varieties onto his apples for years, and it was intriguing

to see the grafts one to three years after joining. He even sent

me home with two little Colette pear trees grafted onto rootstock last

winter --- we tasted some of his homegrown Colettes last year and were

blown away by the flavor.

I also dropped by his

spring-fed pond to get a bit more inoculant for my tiny water

garden (as Sara suggested I call it instead of a puddle).

This pond's water will stay more cold and aerated than mine, so I'm not

positive the water snails and water cress will make the transition, but

I suspect the forget-me-nots and water mint will do fine.

Finally, we gathered a

few wild golf balls and I watched my neighbor enjoy pasture

golfing. Isn't that the best part of homesteading --- you can do

whatever crazy thing suits your fancy?

If aquaponics

is such an elegant, created ecosystem, why am I down on it?

Simple --- electricity use.

First, there's the pump (or

pumps) used to push water out of the fish tank and into the grow

beds. Next comes the energy used to heat the water --- to ensure

the bacteria and worms stay active enough to convert fish waste into

nitrates, most people keep their aquaponics systems running at or above

room temperature summer and winter. And then there are the grow

lights since many people run aquaponics systems inside to get more

control over the environment. To be honest, once you pour all

that electricity into the system, I'm not so sure aquaponics is any

better for the earth than mainstream agriculture.

First, there's the pump (or

pumps) used to push water out of the fish tank and into the grow

beds. Next comes the energy used to heat the water --- to ensure

the bacteria and worms stay active enough to convert fish waste into

nitrates, most people keep their aquaponics systems running at or above

room temperature summer and winter. And then there are the grow

lights since many people run aquaponics systems inside to get more

control over the environment. To be honest, once you pour all

that electricity into the system, I'm not so sure aquaponics is any

better for the earth than mainstream agriculture.

Next, there's the fish

food to consider. Although aquaponics looks like a closed loop,

it really isn't --- nearly everyone just buys large quantities of

commercial fish food to nourish their tilapia or goldfish.

Granted, fish are more efficient at converting feed to meat than other

forms of livestock, but you're still basically running a fish CAFO (and

contributing to overfishing since most fish feed contains wild-caught

fish meal.)

Aquaponics arose in

Australia, and there it makes much more sense. Throughout most of

their continent, Australians experience moderate-enough winter

temperatures that they don't need to bring their aquaponics systems

indoors. And rain is scarce enough that minimizing water use may

trump minimizing electricity consumption. Aquaponics also has

potential in other subtropical and tropical climates, especially in

cities where good soil is scarce.

Aquaponics arose in

Australia, and there it makes much more sense. Throughout most of

their continent, Australians experience moderate-enough winter

temperatures that they don't need to bring their aquaponics systems

indoors. And rain is scarce enough that minimizing water use may

trump minimizing electricity consumption. Aquaponics also has

potential in other subtropical and tropical climates, especially in

cities where good soil is scarce.

The other place where

aquaponics shines is if you consider it a way of growing high-density

fish with the plants just being a side note. Wild-caught fish and

factory-farmed fish both have environmental problems attached, so it

makes sense to try to come up with a more sustainable solution.

That assumes, of course, that you actually eat the fish in your

aquaponics setup, unlike the author of Aquaponic

Gardening who came

to regard her tilapia as pets.

| This post is part of our Aquaponic Gardening lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

A coal

shovel provides easier scooping and twice the carrying capacity of

a regular shovel.

Why did it take me years to

figure this out?

We've had a coal shovel since

we moved here, but I only recently re-found it behind a pile of stuff

in the barn this past summer.

At this time of year,

you hear a lot of grumbling when the weather turns wintry. The

gist seems to be "Isn't it over yet?!" But, while I can

understand the sentiment, I've learned at the Mark School of Positive

Thought that the best place and time to be is right where and when you

are.

With that in mind, not

only am I cleaning the soot off the wood stove's glass door so I can

cherish the last fires, I'm also remembering that a slow spring often

means more fruit. Last year at this time, the peach

buds were swelling...and

a late freeze wiped out every tree fruit. Maybe 2013 will be more

like 2010 when

flowers were slow to open and our peach tree was

loaded with luscious orbs a few months later?

My challenge to the

Walden-Effect hive mind is --- can we take the

elegance of an aquaponics system and reinvision it without the

unsustainable aspects?

Here are some options I'm considering:

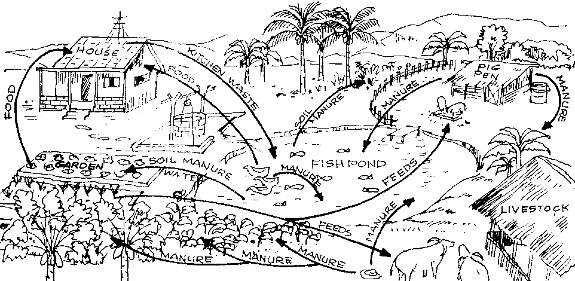

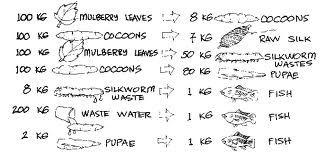

Follow the

lead of the Chinese.

I've read several tidbits about the way traditional Chinese agriculture

integrates fish into their agricultural systems. One system

involves silkworms eating mulberry leaves, fish being fed the sikworm

pupae after the silk is removed from the cocoons, and the fish waste

being dredged up to fertilize the mulberry trees. Humans get

money from the silk and food from the fish with no outside inputs.

Follow the

lead of the Chinese.

I've read several tidbits about the way traditional Chinese agriculture

integrates fish into their agricultural systems. One system

involves silkworms eating mulberry leaves, fish being fed the sikworm

pupae after the silk is removed from the cocoons, and the fish waste

being dredged up to fertilize the mulberry trees. Humans get

money from the silk and food from the fish with no outside inputs.

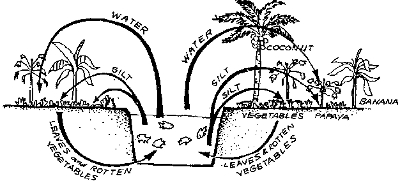

Go back to basics. A simple pond full of

aquatic plants, snails, and insects can feed low populations of

fish. Then you could harvest the aquatic plants to turn into

compost or mulch for the garden and eat the fish (or feed them to your

chickens if you'd rather).

Go back to basics. A simple pond full of

aquatic plants, snails, and insects can feed low populations of

fish. Then you could harvest the aquatic plants to turn into

compost or mulch for the garden and eat the fish (or feed them to your

chickens if you'd rather).

Take

advantage of the water's thermal mass. If we ever built a passive

solar greenhouse,

we'd want to include tanks of water as thermal mass. Turn those

tanks into fish tanks, make an integrated ecosystem just like you would

in a pond, then scoop out water from time to time to water and lightly

fertilize plants in the greenhouse.

What kind of

fish-related permaculture systems have you seen or dreamed up that

require absolutely no electricity or commercial fish food?

| This post is part of our Aquaponic Gardening lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I finally got a latch

installed on the new chicken

pasture gate.

The plan was to paint it

next, but a shelf project and some wood chopping pushed painting down

the list.

I've been looking forward to

laundry day so I could try out my new laundry

nook beside the greywater

wetland. And

it works like a charm!

I've been looking forward to

laundry day so I could try out my new laundry

nook beside the greywater

wetland. And

it works like a charm!

I actually thought I

might need to add rocks to the slope between the laundry nook and the

wetland to prevent erosion, but the water gushes out with such force it

ends up right where I want it.

Dishwater hasn't been

enough to wet more than the entrance to the wetland, but the washer

dumps enough water to inundate the whole depressed area. Not so

much it runs into the pond, though, which is a good

thing.

So far, all the

greywater wetland does is prevent excess water from souping up the

yard. I keep planting things in the wetland and around the edges,

though, so in a few months hopefully leaves will pop out and the whole

ecosystem will come together.

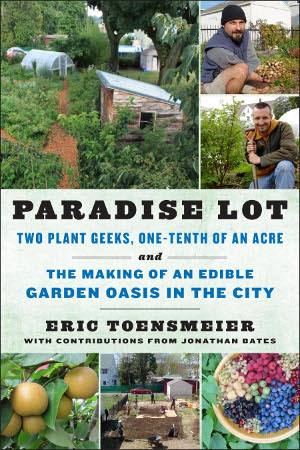

Paradise

Lot is Eric

Toensmeier's tale of how he tested the hypotheses he and Dave Jacke set

forth in Edible

Forest Gardens.

Toensmeier and his friend Jonathan Bates bought a duplex with a tenth

of an acre backyard in Holyoke Massachusetts (zone 6) in January 2004,

spent a year learning the site and planning out their forest garden,

then they dove in and made it happen. By 2009, salamanders,

fungi, and other wild creatures had shown up in what used to be a

compacted urban lot, Toensmeier and Bates had both attracted mates, and

all four of them were happily grazing on the bounty produced by their

forest garden.

Paradise

Lot is Eric

Toensmeier's tale of how he tested the hypotheses he and Dave Jacke set

forth in Edible

Forest Gardens.

Toensmeier and his friend Jonathan Bates bought a duplex with a tenth

of an acre backyard in Holyoke Massachusetts (zone 6) in January 2004,

spent a year learning the site and planning out their forest garden,

then they dove in and made it happen. By 2009, salamanders,

fungi, and other wild creatures had shown up in what used to be a

compacted urban lot, Toensmeier and Bates had both attracted mates, and

all four of them were happily grazing on the bounty produced by their

forest garden.

Unlike Toensmeier's

other books, Paradise

Lot is fun, easy

to read, and inspiring. (Don't get me wrong, I think Perennial

Vegetables and Edible

Forest Gardens

are seminal works, but neither is something you'd read entirely for

fun, while Paradise

Lot is.)

This week, I'm going to include a few highlights in a

slightly-truncated lunchtime series, but I recommend you check out Paradise

Lot yourself to

while away a winter afternoon. Maybe you'll end up having an

epiphany and decide to try out something crazy this year, like raising

silkworms for chickens.

Or maybe you'll simply enjoy reading the first book I've seen profiling

the growing pains of an actual North American forest garden. Just

be aware that you'll need to keep a handle on your wallet because

you'll want to try out several new species by the time the book is done.

| This post is part of our Paradise Lot lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

It's been just over 4 years

since we last cut sycamore

logs for shitake inoculation.

Some of those logs still

produce mushrooms, but not many.

Today we cut off 2 sections

of a large oak that fell during a recent storm.

We're not ready to cut them up into logs, but it was necessary to cut

them off from the main tree so they'll be ready in time to inoculate

this Spring.

Friday, the sun finally came

out and the cold weather broke. A perfect day to check on our

invertebrates! The honeybees were flying busily in and out of

their hive and even visiting the crocuses. But three of our four

worm bins were less vibrant.

Friday, the sun finally came

out and the cold weather broke. A perfect day to check on our

invertebrates! The honeybees were flying busily in and out of

their hive and even visiting the crocuses. But three of our four

worm bins were less vibrant.

I'll start out by

telling you about the one worm bin that's thriving (pictured above and

to the left). This is our first bin, located at the parking area

with a lot of winter sun. The plywood lid bowed down on one side,

so water tends to pool there and seep into the bin. Sure enough,

the area under the pool is full of thriving compost worms, but the rest

of the manure has dried out too much to host worm activity.

I'm sure not sure if the

problem with our other three bins is lack of moisture, cold, or

both. We built

the lids on those bins at a slant

so rain would run off and the wood would last longer. I started

out

the winter by saturating the manure and sawdust bedding, but sometime

over the cold months, all of the water drained away and left the

contents quite dry. Even after I opened the lid this week and let

rain

pound down on the manure, there were still lots of dry pockets when I

poked around Friday, and very few worms were left.

The three bins in our core

homestead are also in heavy shade during the

winter, so the contents probably froze solid a few times. And

there are several other differences between our oldest bins and our

three newer bins beyond moisture and temperature. Looking back at

old photos like the one to the right, I notice that the

vibrant-worm-area is on the side of the bin where I raked

all of the finished compost and worms last August,

so maybe they just haven't spread beyond home base due to the cold

weather? Or maybe they don't like the horse-manure-in-sawdust as

much

as they liked the original horse-manure-in-straw? Or maybe

variety is

the deciding factor since the

worms that went into the core homestead bins

were purchased from a different location than the locally-adapted worms

that went into our original bin.

The three bins in our core

homestead are also in heavy shade during the

winter, so the contents probably froze solid a few times. And

there are several other differences between our oldest bins and our

three newer bins beyond moisture and temperature. Looking back at

old photos like the one to the right, I notice that the

vibrant-worm-area is on the side of the bin where I raked

all of the finished compost and worms last August,

so maybe they just haven't spread beyond home base due to the cold

weather? Or maybe they don't like the horse-manure-in-sawdust as

much

as they liked the original horse-manure-in-straw? Or maybe

variety is

the deciding factor since the

worms that went into the core homestead bins

were purchased from a different location than the locally-adapted worms

that went into our original bin.

Still, moisture is my

best guess, and I have a way to test my hypothesis. As I empty

out the core homestead bins to add manure to the garden, I should

eventually hit a wetter area near the bottom of the bins. If the

damp zone is full of worms, I'll know water was the difference between

the bin that thrived and the bins that didn't.

Mark's already talking

about ways to let rainwater soak in without losing the shade effect of

the lid in the summer --- perhaps drilling holes at intervals

throughout the lid might work. Other ideas for hydration that

don't require running hoses during freezing weather are appreciated.

The best part of Paradise Lot is that Toensmeier is

completely honest about which parts of his forest gardening experiments

succeeded and which parts failed. It turns out that he had nearly

as many growing pains building polycultures in the forest garden as I

did, and came to some of the same conclusions. For example,

Toensmeier recommends letting trees and shrubs get established for a

year or two before adding anything to compete with them, and likes to plant

sun-loving annual vegetables in young forest gardens to take advantage of the

light before the canopy closes up and to keep your attention tuned to

these spots. He also intentionally places vigorous species in

subpar habitat to slow them down so they won't take over the world.

The best part of Paradise Lot is that Toensmeier is

completely honest about which parts of his forest gardening experiments

succeeded and which parts failed. It turns out that he had nearly

as many growing pains building polycultures in the forest garden as I

did, and came to some of the same conclusions. For example,

Toensmeier recommends letting trees and shrubs get established for a

year or two before adding anything to compete with them, and likes to plant

sun-loving annual vegetables in young forest gardens to take advantage of the

light before the canopy closes up and to keep your attention tuned to

these spots. He also intentionally places vigorous species in

subpar habitat to slow them down so they won't take over the world.

On the other hand,

Toensmeier was more tenacious than I've been and came up with some polycultures he considers a success, such

as:

- Hidcote Blue dwarf running

comfrey and walking onions under jostaberries. The

jostaberries are tall enough that they can handle the understory, and

the comfrey and onions are vigorous enough that neither outcompetes the

other.

Ramps, toothwort, and hog peanuts under

pawpaws. The ramps and toothwort take over in the early

spring, then die back just as the hog peanuts begin vining over the

ground.

Ramps, toothwort, and hog peanuts under

pawpaws. The ramps and toothwort take over in the early

spring, then die back just as the hog peanuts begin vining over the

ground.- Jerusalem artichokes and hog peanuts. The Jerusalem artichokes are tall enough and grow fast enough in the spring that the nitrogen-fixing hog peanuts don't choke them out, and both need to be dug at the same time in the fall to harvest the tubers.

- Comfrey and mint.

Toensmeier planted this in his much-travelled alley since the two

vigorous growers can handle quite a lot of abuse.

Although it's not a

polyculture, I was also intrigued by so-called fodder banks --- dense

plantings of trees and shrubs that are coppiced one or more times per

year to produce leaves for livestock or people. Toensmeier

planted littleleaf linden, edible-leaf mulberry, and fragrant spring

tree to produce people food, but I've been planning a similar system

with mulberries to feed the chickens in their pastures.

| This post is part of our Paradise Lot lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We still love both of our Kobalt Neverflat wheelbarrows,

but there's a problem.

It seems that rain can drip

its way into the hollow portion of the handles if stored outside in the

face down position.

I finally got around to

adding a drain hole today, which should prevent any further freezing

and expansion trouble.

Chick weekend is in full

swing! Friday, the first few hatched. Above, two chicks are

groggily exploring the brooder before sleeping off their efforts.

Saturday morning, I

awoke to six fully-fluffed fuzz-balls in the incubator. And the

hatch continued throughout the morning and early afternoon.

By noon on Saturday, the

sun streaming in tempted the older chicks out for a feeding

frenzy. I'm thoroughly enjoying the chicks' company while they're

cute and new, but have no illusions I won't be ready to move them to

the outdoor

brooder before the

week is out.

Toensmeier didn't only report

on his own forest garden in Paradise Lot; he also included tidbits

he'd seen in others' gardens around the world. In his experience,

forest gardeners tend to follow one of three main methods of

incorporating nitrogen-fixing plants into forest gardens.

Toensmeier didn't only report

on his own forest garden in Paradise Lot; he also included tidbits

he'd seen in others' gardens around the world. In his experience,

forest gardeners tend to follow one of three main methods of

incorporating nitrogen-fixing plants into forest gardens.

The first method is

typified by Martin

Crawford's forest garden in England. Crawford includes a

tall, open canopy of nitrogen-fixing plants, which in his case is

primarily high-pruned alders. Toensmeier mimicked this technique

on a small scale by using a mimosa tree as a nitrogen-fixing canopy

species, but he wasn't very interested in using up much of his small

backyard with nitrogen-fixing trees.

Another method that

works well in extensive forest gardens is to alternate nitrogen-fixing

trees with food-producing trees. In general, Toensmeier wrote,

gardeners tend to alternate two or three edibles with one

nitrogen-fixer. Of course, space constraints again make this

approach problematic for the urban gardener.

The final technique, which is

what Toensmeier mostly follows, is to use Geoff Lawton's chop-and-drop

method of coppicing nitrogen-fixing trees and shrubs. Toensmeier

also includes a lot of nitrogen-fixers in the groundcover category,

notably hog peanut, licorice milk vetch, and groundnut, although these

vigorous plants do outcompete some preferred species.

Foot-tolerant groundcovers like clovers and prostrate birdsfoot trefoil

in the pathways can also help bring nitrogen into the system.

The final technique, which is

what Toensmeier mostly follows, is to use Geoff Lawton's chop-and-drop

method of coppicing nitrogen-fixing trees and shrubs. Toensmeier

also includes a lot of nitrogen-fixers in the groundcover category,

notably hog peanut, licorice milk vetch, and groundnut, although these

vigorous plants do outcompete some preferred species.

Foot-tolerant groundcovers like clovers and prostrate birdsfoot trefoil

in the pathways can also help bring nitrogen into the system.

I'm less of a

nitrogen-cycling purist than many permaculture advocates, and I have to

admit that if I had a only a tenth of an acre, I'd devote the whole

acreage to edibles and bring in my nitrogen as manure or compost.

Even Toensmeier admits at the end of his book that the forest-gardening

dream of a do-nothing paradise is unrealistic, and if you're going to

have to nurture the garden anyway, why not topdress a little manure

from your rabbit hutch or chicken coop?

| This post is part of our Paradise Lot lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I forgot to mention a safety

note on the Kobalt wheelbarrow modification.

Avoid drilling at an angle

while holding the handle for support. This will help to keep the bit

from popping out through the sides and scratching a finger.

Ouch!

I've had James Marcus Bach's Secrets

of a Buccaneer-Scholar

on my reading list for a while just because it sounded interesting, but

when B.J. came into our life, the time

seemed ripe for giving it a read. B.J. had trouble with high

school (despite being sharp as a whip), and after completing his GED,

has considered college. Although my own experience with college

was 90% positive, I can't help feeling that most higher education isn't

worth the time and money nowadays, and Mark is even more

anti-establishment. So I opened Bach's book with the question ---

are we doing B.J. a disservice by recommending he self-educate rather

than enroll?

I've had James Marcus Bach's Secrets

of a Buccaneer-Scholar

on my reading list for a while just because it sounded interesting, but

when B.J. came into our life, the time

seemed ripe for giving it a read. B.J. had trouble with high

school (despite being sharp as a whip), and after completing his GED,

has considered college. Although my own experience with college

was 90% positive, I can't help feeling that most higher education isn't

worth the time and money nowadays, and Mark is even more

anti-establishment. So I opened Bach's book with the question ---

are we doing B.J. a disservice by recommending he self-educate rather

than enroll?

James Marcus Bach's book

covers both his own methods of educating himself and the reasons he was

forced to do so. Bach (son of Richard

Bach, who he writes

a lot like) ended up living in a motel down the road from his mother's

house at 14 due to a falling out with his stepfather, and he later

dropped out of high school due to differences of opinion with the

administration. His thesis is that school is great if you enjoy

it, but if you're not getting anything out of the experience, you

should get out. Bach had no problem getting a job at Apple

Computers and then embarking on his own software-testing consulting

business without a high school diploma, and he figures lack of

credentials isn't going to sink anyone else's boat either.

Most of the book is

engagingly written (and quite funny in parts), but I found Bach's

methods of educating himself more dense. Part of the problem is

that Bach clearly thinks and works very differently than I do --- I

suspect a type B person would get more out of this book than I

did. On the other hand, I'm not so sure that Bach's tips would

really work for a type B person who doesn't have a wife to keep the

accounting side of the business  going (as Bach readily admits

he does). And it also seems a bit unfair to assume that just

because the software industry can handle lack of credentials, that all

industries can.

going (as Bach readily admits

he does). And it also seems a bit unfair to assume that just

because the software industry can handle lack of credentials, that all

industries can.

I know that I would be a

very different person if I hadn't gone to college (but, also, that I

wouldn't have gotten nearly as much out of the experience if I hadn't

landed in just the right liberal arts setting). My social

education was probably the most important component of my college

experience, but I also learned a lot of critical thinking skills as

well as how to learn on my own. That said, I probably was ready

to start self-educating after a couple of years of college, and I've

vastly preferred my own recent self-directed learning to any classroom

work I'd done previously.

I'm curious to hear our

readers' take on higher education. If you had a young person in

your life, would you send him to college or mentor him to learn on his

own? Do you feel like college helped you become a more fulfilled

person or did you simply enroll to increase your earning potential (or

perhaps you skipped college for a particular reason)?

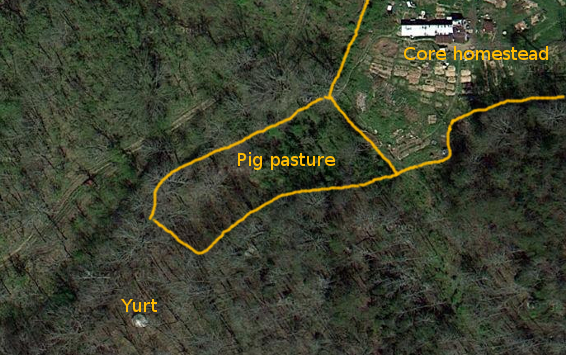

Now that B.J.'s truck makes us 85% sure we can try

pigs this year, I decided it was

time to crack open Storey's

Guide to Raising Pigs

by Kelly Klober. Although some volumes are better than others,

I've enjoyed Storey's

Guides to

various new livestock we've considered adding to our homestead.

The volume on pigs is no exception, being full of a breadth of

firsthand information (although perhaps without as much depth as I'd

like in certain areas).

Now that B.J.'s truck makes us 85% sure we can try

pigs this year, I decided it was

time to crack open Storey's

Guide to Raising Pigs

by Kelly Klober. Although some volumes are better than others,

I've enjoyed Storey's

Guides to

various new livestock we've considered adding to our homestead.

The volume on pigs is no exception, being full of a breadth of

firsthand information (although perhaps without as much depth as I'd

like in certain areas).

Klober takes the same

middle-of-the-road approach in his book that he advocates when breeding

hogs. Sure, crazy permaculturalists like me will have to look elsewhere for in-depth information on

pasturing, but so will folks who want to raise swine in confinement

settings. The book has an excellent overview of what to expect

when raising a couple of finishing hogs for the family's table, when

showing swine, and when starting your own breeding operation.

Overall, I'd highly

recommend this book for the complete beginner (like me), but I'm still

waiting with baited breath for Walter Jeffries to hurry up and complete

his book on pasturing pigs. In the meantime, I hope you'll enjoy

this week's lunchtime series --- an introduction to pigs on the

homestead.

| This post is part of our Storey's Guide to Raising Pigs lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

Our neighbor has an ATV with

a bad battery.

We offered to buy a new

battery in exchange for some hauling help.

It's not 4 wheel drive, but

it did a fine job towing the golf cart back home today.

I

went out to take a photo of our honeybees visiting the crocuses, but

instead caught this fly in the act. In fact, although our

honeybees were out working during the past warm days, flies were making

up about 80% of the pollinators.

I

went out to take a photo of our honeybees visiting the crocuses, but

instead caught this fly in the act. In fact, although our

honeybees were out working during the past warm days, flies were making

up about 80% of the pollinators.

Spring continues to be slow despite the balmy weekend,

so there's not all that much blooming yet. Speedwells and purple

dead nettle are in full bloom in the yard, but I haven't seen any

dandelions yet. In the woods, hazels are blooming, but I haven't

even seen a spring beauty on the forest floor. And the first few

daffodils are just beginning to open their blooms in the sunniest part

of the yard.

Meanwhile, Huckleberry

thinks he's definitely pretty enough to be highlighted in a post about

flowers.

The first thing I learned from Storey's

Guide to Raising Pigs

was that my terminology was all wrong. I wrote previously about

my idea of raising two

pigs from when they're weaned (feeder pigs) until slaughter, which I now know is known

as finishing hogs. According to Klober, the term "pigs" is used

to refer to baby hogs, and piglet is "a layman's term for a young pig,

but don't use this around swine producers unless you want to be laughed

out of the coffee shop." After a short time, pigs grow into

shoats, than at 125 pounds they are known as hogs.

The first thing I learned from Storey's

Guide to Raising Pigs

was that my terminology was all wrong. I wrote previously about

my idea of raising two

pigs from when they're weaned (feeder pigs) until slaughter, which I now know is known

as finishing hogs. According to Klober, the term "pigs" is used

to refer to baby hogs, and piglet is "a layman's term for a young pig,

but don't use this around swine producers unless you want to be laughed

out of the coffee shop." After a short time, pigs grow into

shoats, than at 125 pounds they are known as hogs.

Except for getting the

wording wrong, though, my idea of starting our adventure by finishing

two hogs is a good one. The first step is to find someone who

will sell you pigs when they're around two months old and are well

weaned, at which time you should expect to pay anywhere from $50 to

$200 apiece for the pigs. I'll write more about selecting your

feeder pigs tomorrow, but it's worth noting that if you're skipping the

feeder-pig stage and going right into keeping your own breeding herd,

you'll need to pay more for top-quality genetics.

When you bring your

feeder pigs home, they'll weigh about 40 to 70 pounds, and they'll need

a little TLC at first. Until pigs are eight weeks old, it's best

to keep them on unlimited feed, to wire open the doors of self-feeders

and -waterers, and to keep littermates together.  Even after that, when you move pigs to a

new location, they may go off their feed for a few days and need some

electrolyte in their water (and, Klober suggests, some flavored gelatin

powder sprinkled on their food and in their water to increase

consumption). Walter Jeffries recommends keeping your new pigs in

a 16-by-16-foot area for a few days to get them used to you and to the

fencing before moving them to pasture.

Even after that, when you move pigs to a

new location, they may go off their feed for a few days and need some

electrolyte in their water (and, Klober suggests, some flavored gelatin

powder sprinkled on their food and in their water to increase

consumption). Walter Jeffries recommends keeping your new pigs in

a 16-by-16-foot area for a few days to get them used to you and to the

fencing before moving them to pasture.

Three to four months

after you bring them home, your pigs should have grown into hogs that

weigh more than you do. Hogs are usually butchered at 220 to 260

pounds, with the lower end of the weight range giving leaner meat and

the higher end providing more cost-efficiency at the butcher.

Expect to spend a bit longer growing out your hogs if you're raising

them on pasture, especially if the weather is cold.

Stay tuned for later

posts in this week's lunchtime series walking you through more of the

specifics of raising feeder pigs.

| This post is part of our Storey's Guide to Raising Pigs lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

It took a couple of 2x6's and

an old plastic tool box to load up the ATV.

We learned that it needs to

go in backwards in order to "drive" it up over the wheel humps.

Getting it out was a lot

easier thanks to the help of a hill near our parking area.

When I made our first quick

hoop, I figured the

stucture's cost-efficiency would largely depend on how long the row

cover fabric lasts. Luckily, the delicate fabric gets less

damaged on quick hoops than it did on cold frames, but the combination

of age, snow, and falling branches did result in some serious

dings this winter.

When I made our first quick

hoop, I figured the

stucture's cost-efficiency would largely depend on how long the row

cover fabric lasts. Luckily, the delicate fabric gets less

damaged on quick hoops than it did on cold frames, but the combination

of age, snow, and falling branches did result in some serious

dings this winter.

I waited to do my

mending until it was time to move the quick hoops from the

overwintering beds they were protecting to new beds of spring

crops. Although it's possible to mend fabric when stretched over

the hoops, it's much easier to take it inside, cut out a piece of

fabric from a ruined row cover, and then whip-stitch the patch over the

hole.

I figure it cost about $50 to

make each of our 25-foot-long quick hoops, and after two years of use,

I'd say the fabric will last three years total. We've also had to

replace one of the hoops, and may need to expect to do that every year

or so. If so, our cost to keep a quick hoop going over a decade

will be about $75, or $7.50 per year. Not bad for spring

seed-starting, overwintering lettuce and kale, and protecting the last

summer crops from early frosts.

I figure it cost about $50 to

make each of our 25-foot-long quick hoops, and after two years of use,

I'd say the fabric will last three years total. We've also had to

replace one of the hoops, and may need to expect to do that every year

or so. If so, our cost to keep a quick hoop going over a decade

will be about $75, or $7.50 per year. Not bad for spring

seed-starting, overwintering lettuce and kale, and protecting the last

summer crops from early frosts.

If you decide to finish

a hog or two for your table, your

first big choice is what kind of pig(s) to bring home. Most

sources suggest starting with two animals since pigs are sociable, but

you'll still need to make decisions about breed, sex, and various

medical procedures. Let's start with breed.

If you decide to finish

a hog or two for your table, your

first big choice is what kind of pig(s) to bring home. Most

sources suggest starting with two animals since pigs are sociable, but

you'll still need to make decisions about breed, sex, and various

medical procedures. Let's start with breed.

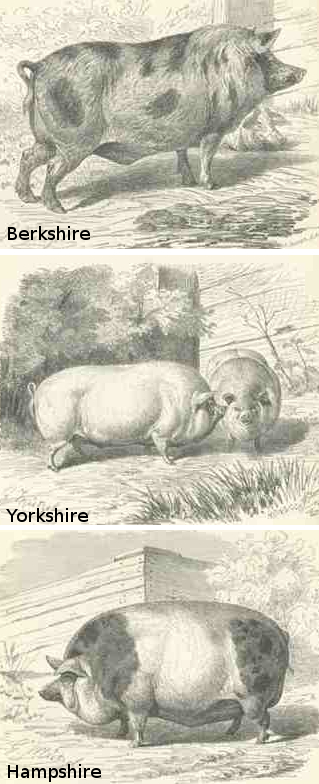

Commercial pigs are

generally pure or crossed Duroc, Hampshire, and

Yorkshire hogs, but small producers would be hard-pressed to maintain a

commercial-style hybrid without keeping two separate parent lines

going.

Klober considers purebreds best for small farmers keeping homegrown

herds, but my limited research elsewhere suggests that pastured pork

producers

often work with a single hybrid herd. For example, Walter

Jeffries' hogs are primarily a mixture of Yorkshire,

Hampshire, Berkshire, and Tamworth, while a producer local to us is

mixing Yorkshire, Hamphsire, Berkshire, and Duroc.

In general,

colored breeds may grow faster, taste better, and handle the outdoors

better in cold, damp weather, while white breeds are better mothers,

are

more docile, and do better in heat. Another factor to consider is

that fat flecks in the meat of

Duroc and Berkshire hogs are supposed to provide particularly good

flavor. But chances are, if you're just buying feeder pigs,

you'll

take whatever's available.

How about choosing

between gilts (girls) and boars (boys)? Gilts

are reputed to grow a bit slower, and to end up fatter (according to

Jeffries and our local producer) or leaner (according to Klober, who

raises his gilts on high-protein rations to speed their growth).

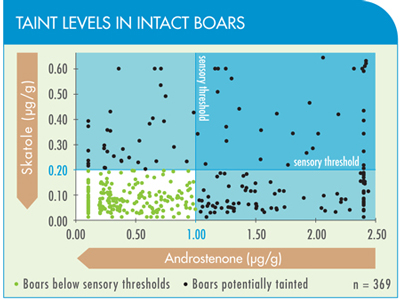

With barrows, the tricky question is whether or not to castrate the

pigs --- most sources recommend castrating boars (in which case they

become barrows) to prevent a bad taste in the meat known as boar

taint. However, Walter Jeffries believes boar taint is mostly a

myth and is only found in certain breeds, which don't include the ones

he raises. If you don't want to castrate and don't want to risk

boar taint, gilts might be a good choice.

While you're deciding whether

or not to castrate, you'll also need to

decide whether to dock tails and knock out wolf teeth. Both of

these

surgeries seem to be similar to clipping the beaks of chickens ---

confinement farmers do it so their animals don't kill each other when

packed close together, but non-confinement farmers usually skip

it. Similarly, you might get away without deworming your feeder

pigs if you're raising them in a rotational pasture arrangement.

(Organic alternatives to chemical dewormers include garlic and

diatomaceous earth.)

While you're deciding whether

or not to castrate, you'll also need to

decide whether to dock tails and knock out wolf teeth. Both of

these

surgeries seem to be similar to clipping the beaks of chickens ---

confinement farmers do it so their animals don't kill each other when

packed close together, but non-confinement farmers usually skip

it. Similarly, you might get away without deworming your feeder

pigs if you're raising them in a rotational pasture arrangement.

(Organic alternatives to chemical dewormers include garlic and

diatomaceous earth.)

The last factor to

consider when choosing your pigs is the environment

that they came from. If you plan to raise pigs on pasture, don't

buy them from heated nurseries. And, at the other extreme,

pastured pigs won't do as well in confinement.

I'd be curious to hear

from more experience pig-keepers out

there. Do you recommend gilts or boars? Do you

castrate? Any other tips for choosing a good pig for the

homestead?

| This post is part of our Storey's Guide to Raising Pigs lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

I bought this foot pump back

in the summer as a backup to the air tank.

We don't have a compressor,

which means filling the tank requires a trip to the gas station.

The foot pump worked nicely

today on the Heavy Hauler, which we're getting ready for an

upcoming feed store delivery.

We'd figured getting pigs was dependent on finding a pickup truck to haul the stock panels

home. But after we considered the sixteen-foot length of the

panels, we ended up calling up the feed store and asking if they

deliver. It turns out they were willing to bring panels, posts,

and the rest of our gypsum and lime to our parking area for $40, which

seemed like a good deal. I figure it would cost about that much

in gas to make the many trips required to ferry all those supplies in a

smaller vehicle.

All of B.J.'s hard work adding

gravel to the parking area really paid off when the

huge truck showed up and barely spun at all maneuvering through our

small space. We did hit a snag, though --- it turns out that most

farmers have front loaders even in our backwoods location, so the

delivery guy thought I was a bit nuts when I said we were going to

unload the panels by hand. It wasn't really that tough with me,

Mark, and him all working together, though.

The next big deal is

getting those stock panels back to our core homestead, after which it

becomes time to clear some small trees, and make the fences. I've

promised Mark a fence post driver at long last in hopes that a new tool

will make this daunting project more palatable, but I'm not sure the

bribe is big enough for the amount of work involved.

Now for the thorny part of

pig-raising --- feeding. As with most other livestock, the modern

method is to pour grains (and soybeans) down their throats to produce

fast growth. At the other extreme, diversified farmers like

Walter Jeffries raise their pigs with absolutely no purchased grain,

counting on fruit-tree-filled pastures, crops planted during fallow

periods then grazed rotationally, and byproducts such as whey and

brewer's barley to fulfill their hogs' nutritional needs. Going

back in time yet further, a hog was a bit of a farm garbage disposal

unit --- you'd keep just one or two pigs and they'd subsist on all of

the food waste that came out of a homestead kitchen, plus mast from the

forest.

Now for the thorny part of

pig-raising --- feeding. As with most other livestock, the modern

method is to pour grains (and soybeans) down their throats to produce

fast growth. At the other extreme, diversified farmers like

Walter Jeffries raise their pigs with absolutely no purchased grain,

counting on fruit-tree-filled pastures, crops planted during fallow

periods then grazed rotationally, and byproducts such as whey and

brewer's barley to fulfill their hogs' nutritional needs. Going

back in time yet further, a hog was a bit of a farm garbage disposal

unit --- you'd keep just one or two pigs and they'd subsist on all of

the food waste that came out of a homestead kitchen, plus mast from the

forest.

While I'd love to mimic Jeffries' method

in the long run, we're in the reclamation stage of our homestead, so I

suspect we'll be taking a hybrid approach our first year. Klober

notes that a quarter of an acre of good legume pasture will provide 25%

of the nutrition for 10 growing hogs, so I'm hoping a similar amount of

poor forest pasture will provide at least a bit of nutrition for

2. But we'll also supplement with storebought feed (and with our

food scraps, which will be much more copious in late summer).

Klober says we should expect to feed each hog 650 to 750 pounds of

storebought feed over its short lifetime, and I'll definitely be

keeping track to see how much we knock off that estimated total.

While I'd love to mimic Jeffries' method

in the long run, we're in the reclamation stage of our homestead, so I

suspect we'll be taking a hybrid approach our first year. Klober

notes that a quarter of an acre of good legume pasture will provide 25%

of the nutrition for 10 growing hogs, so I'm hoping a similar amount of

poor forest pasture will provide at least a bit of nutrition for

2. But we'll also supplement with storebought feed (and with our

food scraps, which will be much more copious in late summer).

Klober says we should expect to feed each hog 650 to 750 pounds of

storebought feed over its short lifetime, and I'll definitely be

keeping track to see how much we knock off that estimated total.

Finally, there are two

schools of thoughts on how much food to offer growing

hogs. Some farmers provide unlimited feed, which does make pigs

grow their fastest. On the other hand, if you limit feed to 90%

of their appetite, you end up with a leaner

carcass (although you don't lower your food bill any since the hogs

grow more slowly). Most modern farmers aim for leaner meat, but

as Simon

Fairlie wrote,

farmers used to consider lard one of the most important byproducts of

hog production, so the choice is up to you.

| This post is part of our Storey's Guide to Raising Pigs lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

We got all 40 stock

panels back to the new

pasture area today.

The Heavy Hauler supports part of the load.

I started out doing 3 at a

time, but quickly figured out the ATV could handle 7.

My movie-star neighbor kept

his grafted pears over the winter in pots in an unheated

basement. However, the bit of heat from the house was enough to

prompt them to break open their buds before I brought my

two home.

My movie-star neighbor kept

his grafted pears over the winter in pots in an unheated

basement. However, the bit of heat from the house was enough to

prompt them to break open their buds before I brought my

two home.

Afraid that nippy spring

weather would hurt the tender buds, I put them in the mostly-unheated

end of the trailer, but a week later the buds were yet more

unfurled. I figured there was no stopping the plants' awakening,

so I might as well put them in the ground where cool temperatures would

at least slow them down.

Since our main pears

have also started to break their buds open (although not in as extreme

a fashion), I figured our new pears would probably survive

outdoors. And, sure enough, I don't see any frost-burn even after

a frigid night (and a day of flurries).

I plan to keep our

little pearlets in our new nursery row for a year, then plant them into

the pasture prepared by hog snouts this summer. Pears are slow to

bear, but the taste of my neighbor's fruit is enough to carry me

through dreaming about the harvest of 2019.

There are a slew of other

factors to consider when starting with pigs, but here are the top ones

on my radar:

There are a slew of other

factors to consider when starting with pigs, but here are the top ones

on my radar:

- Housing --- Each pig needs 8 to 10 square feet of sleeping space, preferably somewhere dry, draft-free, and out of the muck.

- Feeders and waterers --- Plan on one foot of trough space per hog or one self-feeder hole for three to five feeder pigs.

- Fencing --- Assuming

you're pasturing your pigs, you need to choose a fencing method and pay

attention to the where the fencing touches the ground. Unlike

many other farm animals, pigs like to go under rather than over fences

(although they'll go through them too if given the chance). Most

folks choose electric fencing, but we're going to go the

more-expensive-but-also-more-permanent route of stock panels.

Other options that work for pigs include pallets and woven wire.

Preventing damage to the pasture

--- Many pastured pork producers put a ring on the end of their hogs'

noses to prevent rooting damage. On the other hand, others use

the rooting nature of pigs to their advantage by putting the

animals into an area where they want the current plant-life destroyed

--- we're using that route this first year. It's also worth

noting that sharp pig hooves will tear up pasture nearly as much as

their snouts do, especially in oft-traveled areas like around feed and

water stations.

Preventing damage to the pasture

--- Many pastured pork producers put a ring on the end of their hogs'

noses to prevent rooting damage. On the other hand, others use

the rooting nature of pigs to their advantage by putting the

animals into an area where they want the current plant-life destroyed

--- we're using that route this first year. It's also worth

noting that sharp pig hooves will tear up pasture nearly as much as

their snouts do, especially in oft-traveled areas like around feed and

water stations.- Keep them cool --- Hogs are naturally woodland creatures and need some shade in the summer.

- Plan your butchering before you

start --- Many homesteaders skin their hogs nowadays instead of

scalding them, but if you go that route, you'll lose most of the lard

and won't be able to cure the hams. (You'll still be able to cure

bacon after skinning.) So, don't buy a gilt and try to get her

really fat if you think you're going to skin.

What else would you

suggest new pig-keepers consider?

| This post is part of our Storey's Guide to Raising Pigs lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

Our stock

panel hauling had one problem.

The dump mechanism won't stay