archives for 03/2012

Joy wrote in recently to

tell me about an alternative quick

hoop design she'd

seen while touring a nearby farm. She wrote:

Neither had I, so I thought I

should share the design. It looks like the structure of the hoops

comes from remesh with metal pipes along the bottom.

Neither had I, so I thought I

should share the design. It looks like the structure of the hoops

comes from remesh with metal pipes along the bottom.I'm a bit afraid of the scratch factor from working with remesh, but I think the design has merit as a jumping off point for further experiments. If you try it out, I'd be curious to hear what you think of this alternative. And, as you spread the idea, be sure to credit it back to Steve Whiteman at Trillium Farms who can be reached at stevesmicrogreens@gmail.com.

Our chicken waterer prevents day old chicks from

drowning and gets them off to a healthy start.

Sepp Holzer raises cattle,

bison, yaks, water buffalo, ducks, and chickens on his farm, but his centerpiece

animal is clearly

the pig. His swine are nearly self-sufficent, and also help out

by eating spoiled fruit in the orchard, increasing plant diversity by

creating small patches of bare ground, and regulating the snail

population. Holzer scatters feed on the ground when he wants the

soil loosened, and his pigs till that specific patch of earth.

And, of course, they provide meat.

Sepp Holzer raises cattle,

bison, yaks, water buffalo, ducks, and chickens on his farm, but his centerpiece

animal is clearly

the pig. His swine are nearly self-sufficent, and also help out

by eating spoiled fruit in the orchard, increasing plant diversity by

creating small patches of bare ground, and regulating the snail

population. Holzer scatters feed on the ground when he wants the

soil loosened, and his pigs till that specific patch of earth.

And, of course, they provide meat.

Holzer's pigs (and other

livestock) live in rotational paddocks that encompass his entire

farm. So the pigs move through the vegetable garden when it's

fallow, through the orchard to clean up windfalls, and

through the green

manure areas busy

improving the soil.

Holzer's pigs (and other

livestock) live in rotational paddocks that encompass his entire

farm. So the pigs move through the vegetable garden when it's

fallow, through the orchard to clean up windfalls, and

through the green

manure areas busy

improving the soil.

The pigs are stocked at

a density of about one to five pigs per acre, and are allowed to do a

moderate amount of damage before moving to the next paddock.

Holzer ensures that perennial tubers like Jerusalem artichokes aren't

entirely dug up by swine snouts, and finds that pig action spreads

smaller tubers around so that the plants actually expand before the  livestock come through

again. In the vegetable garden, he makes sure to leave lots of

crops unharvested at the end of the year, including beets, carrots,

turnips, cabbage, and potatoes, so that the pigs have something to eat

during the winter. And after the pigs leave a paddock, Holzer

seeds bare ground with green manure crops, tree seeds, or vegetables.

livestock come through

again. In the vegetable garden, he makes sure to leave lots of

crops unharvested at the end of the year, including beets, carrots,

turnips, cabbage, and potatoes, so that the pigs have something to eat

during the winter. And after the pigs leave a paddock, Holzer

seeds bare ground with green manure crops, tree seeds, or vegetables.

For those of you who

want to follow along at home, the trick to making sure that pigs

don't create a moonscape is variety choice and plenty

of space. Holzer's favorite breeds are Mangalitza, Swabian-Hall,

Duroc, and Turopolje, heritage breeds that may or may not be available

in the United States.

| This post is part of our Sepp Holzer's Permaculture lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

There's a small piece of 1x1

attached to the bottom edge of the carpet

for weight.

We will soon find out if

chickens are smart and or strong enough to push through.

Lucy figured it out in 10

minutes once we involved a chunk of Milk Bone.

When

we started eating our Hakurei turnips in November, Daddy admonished me, "Don't

eat the turnips, eat the greens all winter long." So I left them

alone to see what would happen.

When

we started eating our Hakurei turnips in November, Daddy admonished me, "Don't

eat the turnips, eat the greens all winter long." So I left them

alone to see what would happen.

I was disappointed when

my turnips didn't put out many more leaves, but that's to be expected

since our Persephone

Days were beginning

by the time I cut the turnip tops the first time. Then, this

week, I discovered the real treat from overwintering turnips ---

"turnip raab" (aka "almost broccoli raab").

Despite the name,

broccoli raab is actually most closely related to turnips. Also

known as rapini, the vegetable is grown primarily for the unopened

flower buds, which can be cut repeatedly and which taste a bit like

broccoli. I haven't had good luck with broccoli raab in the past

--- it seems to bolt quickly and barely give me much of a harvest ---

so I stick to real broccoli.

That said, the flower

buds on my turnips were delicious, and the plants seem to be following

the lead of their relatives by sending out side shoots once I cut the

main head.  We've been eating bolted

mustard buds for a few weeks now, but the turnip buds are clearly a cut

above, with thicker stalks that don't go woody as quickly.

We've been eating bolted

mustard buds for a few weeks now, but the turnip buds are clearly a cut

above, with thicker stalks that don't go woody as quickly.

The moral of the story

is --- if you have overwintering turnips, go out and check on them now

for some bonus broccoli raab. The buds are best before they open,

but even young flowers like this are pretty tasty when you saute with

some mustard leaves and a bit of balsamic vinegar and peanut oil.

Whatever you do, don't pull out the bolting plants and consider them a

loss!

Sepp

Holzer's book has a whole chapter on growing edible mushrooms, which

helped me realize that he was probably the one who came up with the

ideas of mushroom

totems and notching

logs for easy inoculation. He also has the

following helpful tips for the permaculture mushroom keeper:

Sepp

Holzer's book has a whole chapter on growing edible mushrooms, which

helped me realize that he was probably the one who came up with the

ideas of mushroom

totems and notching

logs for easy inoculation. He also has the

following helpful tips for the permaculture mushroom keeper:

- Inoculate most logs ASAP, but wait to inoculate stumps until they stop resprouting. (I'll bet this is why neither of my stumps have produced fruit --- the living tree probably killed off the invading fungi.)

- Propagate most mushrooms by spawn, but use spores with woodtufts and enoki. Just place ripe caps on the end of moist, newly cut logs and the fungi will colonize them. However, spore propagation takes much longer than vegetative propagation, even among the mushroom species that handle the process well.

- To plug inocolution holes quickly when you're out in the woods, just stick in a twig of the right size and cut off the excess.

When inoculating logs with

notches, cut more than half the diameter of the log, fill it with

spawn, and cover the wound with plastic sheeting or adhesive tape.

When inoculating logs with

notches, cut more than half the diameter of the log, fill it with

spawn, and cover the wound with plastic sheeting or adhesive tape.- Rather than sticking mushroom totems in the ground right away, expedite colonization by pushing all of the logs together and covering them with leaves and jute bags. Once fungi have grown through the logs, you can sink them a third of the way in the ground in the direction that the tree grew for low-work fruiting.

- Onion bags full of ripe mushrooms can be hung in trees to spread

spores throughout your woodland.

Although his mushroom

chapter is only twenty pages long, it's one of the best primers I've

seen for homesteaders who want to incorporate mushrooms into their

ecosystem in the easiest ways possible.

| This post is part of our Sepp Holzer's Permaculture lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Our new Eco-Glow chick

brooder works great, but

it needs some help on cold, wet mornings like today.

The above configuration is

full of possible hazards, but not a terrible solution if you can

control any possible delinquent

cats that might be in the vicinity.

I was going to include a

picture of the first new chick, but I guess he's camera shy.

I

was totally unprepared for our first hatch of the year, for a couple of

reasons. First, our 2011 chicks never seemed to even consider

hopping out of their shells until day 22, which I now figure may be due

to our hatching

eggs being weakened

when they were jostled around by the postal service.

I

was totally unprepared for our first hatch of the year, for a couple of

reasons. First, our 2011 chicks never seemed to even consider

hopping out of their shells until day 22, which I now figure may be due

to our hatching

eggs being weakened

when they were jostled around by the postal service.

Which is all a long way of saying --- I thought I had all day Friday to

get the little indoor brooder ready for chicks so that I could be

prepared for a hatch to begin Saturday afternoon. The tupperware

container was outside, wet and dirty, and the leaves I planned to use

for bedding were still a bit damp.

Second, by this stage of

the winter, I've gotten acclimated to mild cold. Most

of this past week, overnight temperatures only dropped into the

forties, and

I woke to a trailer around 50 degrees Fahrenheit. It hardly

seemed

worth lighting a fire since my morning walk with Lucy warmed my blood

enough to tide me over until the sun came through the trees and heated

the trailer to summer levels. But chicks are less resilient (and

our brooder is only rated down to 50 degrees Fahrenheit with bone dry

chicks and bedding).

So our first chick of

2012 hatched into a household scurrying around to prepare his

brooder. I set Mark on cleaning out the brooder while I watched

the tiny ball of fuzz push its way out of the shell.

Last year, I got into

the habit of moving chicks out of the incubator nearly immediately

rather than waiting until they dried off fully since I didn't like

newly hatched chicks rolling the unhatched eggs around. So, half

an hour after hatch, I plucked out our hatchee and popped him under the

Brinsea

Ecoglow Brooder.

Peep, peep, peep. The peeping got worse

and worse until I was tearing out my hair. I thrust the chick

back into the incubator, lit a fire in the woodstove, and turned on a

space heater, all at the same time. (At least the chick didn't

end up in the stove.) Then, half an hour later, I tried Operation

Chick Move again.

Peep, peep, peep. The peeping got worse

and worse until I was tearing out my hair. I thrust the chick

back into the incubator, lit a fire in the woodstove, and turned on a

space heater, all at the same time. (At least the chick didn't

end up in the stove.) Then, half an hour later, I tried Operation

Chick Move again.

Peep, peep, peep. Boy, that chick

wasn't a happy camper, and neither was I. With some trepidation,

I set the brood box up on top of the space heater and ran to get Mark's

input.

Peep,

peep, PEEP. The chick was still

yelling his head off, so Mark

added another space heater to increase the temperature inside.

Peep, peep, peep, peeeep.

Finally, peace and quiet! Lesson learned --- homegrown eggs might

pop open on day 20 and early spring chicks need some extra heat beyond

the Brinsea brooder during the drying off period. And here I

thought I was such an old hand that there wouldn't be any drama during

the hatching period. Stay tuned to hear the stats on the rest of

the hatch.

Two bungee cords was what it

took to make the new chick

coop convertible.

I've been using these mug

hooks on several projects lately.

They're self starting and

easy to install. I try to keep a package on hand for any emergency chicken projects.

We're flooded in and our

roofing

tin is partially

submerged halfway back through the floodplain. But talking about

that isn't nearly as much fun as pondering ebook ideas.

I told you two weeks ago

that working

hard to make Weekend Homesteader a text worthy of print publication had

worn me out...but

that I expected to be gungho about writing again by the end of the

month. Sure enough, last week I started dreaming up ebook ideas

as I weeded the beds to prepare for planting spring greens. Here

are the top contenders so far:

- Garden Ecology ---

Several books cover the identification of beneficial and pest insects,

but I would delve deeper, walking you through identifying large and

small critters, fungi, and plants that live in your garden but don't

cause enough problems to end up on the list of garden bandits.

With chapters on producers, decomposers, predators, and pollinators,

you'd learn about food webs and nutrient cycles and figure out how to

manage your garden to keep a healthy ecosystem in place.

Estimated length: 4 ebooks with 30 to 40 pages each.

- The Permaculture Chicken

--- This intermediate guide to chickens starts where most books leave

off and helps you turn your flock into a more self-sufficient and

integrated part of the homestead. Learn the pros and cons of

housing your chickens in tractors, pastures, or free range; choose

chicken varieties good at rustling up their own grub; and manage a

small-scale pasture of annuals and perennials that keeps your flock

healthy. A chapter on incubation will make raising your own

chicks less traumatic for newbies, while tips on cooking with heirloom

chickens will help you make the transition from supermarket chicken

breasts to more wholesome fowl. Finally, I'll give you ideas for

using chickens as more than mere producers of eggs and meat --- their

pastures can keep out deer, their manure can feed the garden, and the

chickens themselves can scratch cover crops into the ground.

Estimated length: 6 ebooks with 30 to 40 pages each.

- No-till Cover Crops ---

This short guide reveals the pros and cons of the three main types of

cover crops --- small grains, legumes, and everything else --- and

helps you choose varieties that match your gardening style. Learn

the easiest ways to plant and kill cover crops without tilling the soil,

then time your planting to fit into fallow periods you didn't even know

existed in your garden year. Estimated length: 1 ebook with 30 to

40 pages.

You did such a good job

of choosing a

winner

last year that I'm going to let you weigh in on this year's project as

well. Which of these ideas sounds like something you'd like to

hear me

write about at length? Is there another topic you wish I'd write

about instead? Thanks in advance for your feedback!

The creek is still too high

to cross wearing hip waders.

Not a problem if you're part

of the dedicated roofing team working on our barn.

They got the tin moved

back and all but one panel installed.

We are both very impressed

with their level of hustle!

Rather

than braving

the raging creek to

carry in the milled grain we bought for our chicks, I've been

tantilizing their budding appetites with hard-boiled eggs.

Technically, I could have just waited until the flood waters receded

--- after all, chicks can go for three days without food or water after

birth. But they'd already figured out how to drink from

their chicken waterer within hours of landing in

the brooder, so I figured they could handle some solids as well.

Rather

than braving

the raging creek to

carry in the milled grain we bought for our chicks, I've been

tantilizing their budding appetites with hard-boiled eggs.

Technically, I could have just waited until the flood waters receded

--- after all, chicks can go for three days without food or water after

birth. But they'd already figured out how to drink from

their chicken waterer within hours of landing in

the brooder, so I figured they could handle some solids as well.

I can't help wondering

whether we couldn't get chicks off to an even better start by feeding

them real food for the first few weeks, while their appetites are small

enough that the fancy foods won't break the bank (or wear us out

foraging). I've seen a mother hen pecking apart worms for her day

old offspring, which makes me think animal products are the way to go.

What's your favorite

homemade chick starter feed? Have you ever raised chicks on

non-storebought feed?

This

week's lunchtime series is a little unusual. I usually either

titillate you with a topic I feel (semi-) expert on, or highlight the

most interesting facts from a book. But topworking my pears was

so educational (and photo rich) last week that I decided to bring you

along and let you walk through the process with me.

This

week's lunchtime series is a little unusual. I usually either

titillate you with a topic I feel (semi-) expert on, or highlight the

most interesting facts from a book. But topworking my pears was

so educational (and photo rich) last week that I decided to bring you

along and let you walk through the process with me.

I have to admit, though,

that I'm far from an expert at grafting.

I've taken a couple of workshops and read a few websites and chapters

on the topic, but I'm still very much learning. I'm also

experimenting with ways to graft without buying the tools and

supplies most grafters think they need since I figure if I went out to

find the official

tools for every project I wanted to try on the homestead, we wouldn't

have room for them even in our huge barn.

Which is all a long way

of saying that I hope those of you with more

experience will chime in this week and point me in a different

direction if you think I'm going astray. And, as for the rest of

you with even less experience than me, take this series with a grain of

salt --- this is the way I did it, not necessarily the way you should.

| This post is part of our Grafting Experiment lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Need some foam,

but don't know how to get an 8 foot by 4 foot sheet in your car?

You could cut the sheet into

sections in the parking lot, or get one of these panel kits for about 6

dollars.

We've had a strangely

elongated hatch this time around, which I think is due to cold weather

exacerbating differences

in temperature within the incubator. But it's hard to

complain when the final count is 18 living chicks, two yolkers (which

were either infertile or died very young), and one fully formed but

dead in the shell chick. (It's possible even that last guy might

have hatched, but I thought for sure he was dead when he hadn't pipped

by the end of day 23!)

We've had a strangely

elongated hatch this time around, which I think is due to cold weather

exacerbating differences

in temperature within the incubator. But it's hard to

complain when the final count is 18 living chicks, two yolkers (which

were either infertile or died very young), and one fully formed but

dead in the shell chick. (It's possible even that last guy might

have hatched, but I thought for sure he was dead when he hadn't pipped

by the end of day 23!)

Most of the chicks have australorp

fathers and mothers, but two have sussex and seven have marans

mothers. You know how humans take one look at the squashed up

face of a newborn baby and immediately say it looks like the father

(seldom the mother)? Well, I thought the same of our little

hybrids at first. But soon I noticed that some appeared blacker

than others, making me think those are the maransXaustralorp

chicks. I wonder if I'll see signs of hybrid vigor when the time

comes to weigh then eat them?

face of a newborn baby and immediately say it looks like the father

(seldom the mother)? Well, I thought the same of our little

hybrids at first. But soon I noticed that some appeared blacker

than others, making me think those are the maransXaustralorp

chicks. I wonder if I'll see signs of hybrid vigor when the time

comes to weigh then eat them?

(As you can tell, the

creek went down enough that I could bring in the chick feed. Our

youngsters thought the milled grain was almost as interesting as hard-boiled

egg yolks, but they

spilled it pretty badly until I made a homemade feeder. More on

that eventually if it works.)

My first step after

deciding to topwork my two pear trees was to

find scionwood. I wanted to try specific varieties, so I ordered

some from Burnt Ridge Nursery, but you can also get scionwood from a

neighbor's tree if you know you like the taste and habits of their

fruit varieties. The best scionwood is about the thickness of a

pencil, is from last year's growth, doesn't contain flower buds, and

does contain two or three leaf buds. Longer scionwood is fine,

and gives you some wiggle room in case you make the first cut wrong ---

you can always shorten it to three buds later.

Although you should wait

to prepare your official scionwood until it's ready to go into place

(Thursday's post), raw beginners like me should practice first so we

become relatively adept at our cuts before working on the limited

scionwood. Grafting cuts should always be as straight as

possible, which means you should try to make them with a single cut

rather than "whittling" --- fixing incorrect cuts by making two or

three more cuts. The photo above shows some of my early practice

strokes --- you can see the curves that result from whittling.

Luckily for me, I had plenty

of wood to practice on. I planned to cut the whole top off my two

small pear trees and insert new scionwood in a cleft graft, so nearly

all of the twigs on the tree were fair game.

Luckily for me, I had plenty

of wood to practice on. I planned to cut the whole top off my two

small pear trees and insert new scionwood in a cleft graft, so nearly

all of the twigs on the tree were fair game.

I actually practiced on

a little walnut tree I needed to cut out of the yard first, but soon

discovered that different trees' twigs behave very differently.

If you're going to graft a pear tree, practice on some pear twigs; if

you're going to graft an apple, practice on an apple.

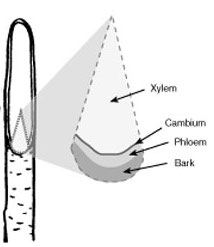

So, what did I want my cuts

to look like? The easiest grafting cut is for a whip graft, where

you attach two twigs of the same diameter together. That kind of

graft simply requires a long straight cut so that the scionwood comes

to a point, as is shown in the drawing to the left.

So, what did I want my cuts

to look like? The easiest grafting cut is for a whip graft, where

you attach two twigs of the same diameter together. That kind of

graft simply requires a long straight cut so that the scionwood comes

to a point, as is shown in the drawing to the left.

For my cleft graft, I

needed to make a slightly more complex cut. I wanted to turn the

base of the scionwood into a wedge by making two angled cuts. To

complicate matters further, the wedge needed to be pie-shaped in

cross-section, with the side containing the lowest bud larger than the

other side of the twig. This sounds complex, but wasn't really

that hard to cut, once I wrapped my head around the goal.

Time to start

cutting! Grafting teachers always warn you to make sure the buds

point up, which seems ludicrously obvious to me, but maybe folks not as

tuned into plants need to be told that? Once you turn your

scionwood right side up, decide which spot will be the bottom of your

cut. I learned the hard way that you won't get a nice, straight

cut if you try to go through a node (where the buds are), so I cut my

scionwood off just above a bud.

It's best if you also

choose a spot where the internode (length of wood between two buds) is

relatively long since your angled cut should be at least an inch long,

preferably 1.5 to 2 inches. Longer cuts give your scionwood a

better chance of merging with the growing tissue of the tree it's being

grafted onto.

relatively long since your angled cut should be at least an inch long,

preferably 1.5 to 2 inches. Longer cuts give your scionwood a

better chance of merging with the growing tissue of the tree it's being

grafted onto.

Now find a good sharp

knife (I used our chicken butchering knife, recently sharpened) and

make your first test cut. Remember, you don't want to whittle, so

you should create the wedge shape at the bottom of your piece of

scionwood in two quick cuts. Once you try it a time or two,

you'll see why I told you to practice on a twig you didn't care about.

After making Mark stand

around in the sun and watch me whittle for about fifteen minutes, I

started to feel like my cuts were going more smoothly. Time

to move on to the next step --- preparing the tree to be grafted

onto. Stay tuned for tomorrow's post to learn tips in that

department.

After making Mark stand

around in the sun and watch me whittle for about fifteen minutes, I

started to feel like my cuts were going more smoothly. Time

to move on to the next step --- preparing the tree to be grafted

onto. Stay tuned for tomorrow's post to learn tips in that

department.

| This post is part of our Grafting Experiment lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We added 2 layers of foam to the floor of the chick

coop in an effort to retain more heat from the Eco-Glow brooder.

The plan is to use the above

Rubbermaid tub as a mini-enclosure for the brooder while inside the

chick coop.

Stay tuned to see if these

preparations will be enough to keep the new round of chicks warm and

happy.

Can

you tell the flower buds from the leaf buds on your fruit trees?

The distinction is important if you prune in the winter, but it's also

handy to be able to guess whether your young trees are going to bear

fruit this year or not.

Can

you tell the flower buds from the leaf buds on your fruit trees?

The distinction is important if you prune in the winter, but it's also

handy to be able to guess whether your young trees are going to bear

fruit this year or not.

In general, flower buds

are fat and round while leaf buds are more pointy and less

significant. The differences really become obvious at this time

of year when the flower buds are swelling up in preparation for

opening, in contrast to leaf buds that are still dormant. (Well,

unless you're a plum, as is shown above, which tends to spit out leaves

at the same time it blooms.)

Apple

buds are a bit trickier, but share the same general theme. Most

apple varieties bloom on fruiting spurs, which are simply dwarfed twigs

sticking out the sides of your branches. You might find a single

flower bud (shown on the right) on a spur, or it might be an entire

cluster. The photo on the left shows an inconspicuous apple leaf

bud.

Apple

buds are a bit trickier, but share the same general theme. Most

apple varieties bloom on fruiting spurs, which are simply dwarfed twigs

sticking out the sides of your branches. You might find a single

flower bud (shown on the right) on a spur, or it might be an entire

cluster. The photo on the left shows an inconspicuous apple leaf

bud.

Pears buds are similar

to apples while peaches are similar to plums. Cherries fall

somewhere in between.

We got a slow start on

our apples, but our oldest tree (a Virginia Beauty planted three years

ago) seems to be covered with flower buds this year. Similarly,

our three year old Methley plum is also dotted with plump flower buds.

I'm trying hard not to

count my fruit before they ripen, though. I've learned from

experience that late

freezes can easily wipe out flower buds, and that young trees often

drop their flowers the first year rather than setting fruit. In

addition, since my Virginia Beauty may be the only apple in my orchard

who's ready to bloom this year, the precocious tree might not get

pollinated.

The plum might have

issues as well. When I bought the tree, it was marked as

self-pollinating, but now I'm seeing that Methley plums are Japanese

type plums and require pollinators --- I guess I'll see who's right

depending on whether we sink our teeth into juicy plum flesh this year

or not. Although it would be a bummer to have to wait another

three years to eat homegrown plums, I never mind an excuse to expand

our fruit selection.

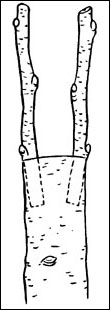

A previous post about topworking explained that my four year

old pears are small enough to graft all in one go. However, I've

also read that it can be tough for a tree of any size to suddenly lose all of its branches, so some

orchardists leave a few in place to shade the scionwood a bit so it's

not exposed to blazing sun while trying to get established. As a

result, I decided to cut into the main trunk just above the first pair

of limbs.

The

other factor to consider when preparing your tree to be grafted onto is

ensuring you make a very clean cut. The success of a graft

depends on the cambium, which is the thin layer of living tissue just

under the bark. So, if you cut a tree and it tears half the bark

off one side in the process, your grafts are going to be less

successful.

The

other factor to consider when preparing your tree to be grafted onto is

ensuring you make a very clean cut. The success of a graft

depends on the cambium, which is the thin layer of living tissue just

under the bark. So, if you cut a tree and it tears half the bark

off one side in the process, your grafts are going to be less

successful.

I worked around this

potential problem by cutting about halfway through the tree, then

coming around to the other side and cutting through the bark

there. When I finished my cut, the top fell off the tree without

damaging the bark at all. (By the way, these sharp

little saws are awesome for making precise cuts like this.)

Timber!

Timber!

The final step in

preparing the tree to be grafted onto is to trim any irregularities

from the wood. One of my cuts came out perfect, and the other

needed just a tad of whittling with my sharp knife. Now the tree

was ready to accept scionwood and to be turned into a new variety.

| This post is part of our Grafting Experiment lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The new chick coop is ramped

up and ready for business.

I've been lucky to have

a weeding buddy come over every week or two for the last couple of

months. Those problem perennials that I didn't quite remember to

weed in the last year? They're almost all ship shape! I

suspect that one more round of weeding will bring the last couple of

rows in line. Thanks, Anndrena!

Now that I've cut

the top off of my young tree, I can insert the

scionwood. Step one is to slit the trunk of the tree vertically

for about two inches --- making the cleft.

Orchadists have special

tools for cleft grafting, but I figured I could find everything I

needed between the kitchen and the toolbox. The small, sharp

knife shown below was too miniscule to do the job, but a big, dull

butcher knife combined with a hammer was just right.

I hammered the big knife

into the center of the trunk, then pounded on the sides of the knife to

insert it a bit deeper. On my second tree, I didn't make the slit

quite so deep, and found it more difficult to insert the scionwood, so

be sure to make your slit big enough the first time.

The next step is to

widen the cleft using a wedge. Again, professionals use a special

tool for this procedure, but a screwdriver pounded in easily and worked

great.

Cut

the scionwood as described previously, then insert two pieces, one

on

each side of the wedge. If the cleft isn't quite as open as you'd

like, you can rotate the screwdriver slightly to widen the gap.

Cut

the scionwood as described previously, then insert two pieces, one

on

each side of the wedge. If the cleft isn't quite as open as you'd

like, you can rotate the screwdriver slightly to widen the gap.

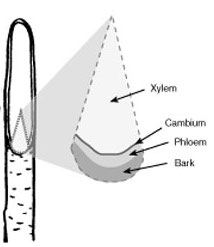

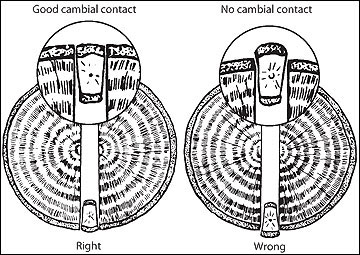

Scionwood insertion is

the trickiest and most important part of the whole process, so take a

few minutes to make sure you're doing it right. The diagram below

shows a cross section through a piece of scionwood, illustrating the

layers of different kinds of cells that make up a twig.

You can think of the cambium

as the stem cells of the plant world --- the cambium cells are still

physiologically flexible and can grow together with the cambium of a

different tree. The cambium is relatively easy to see if you have

good eyes since it tends to be bright green. Your goal is to make

sure the cambium of your scionwood lines up with the cambium of the

tree you're grafting onto.

You can think of the cambium

as the stem cells of the plant world --- the cambium cells are still

physiologically flexible and can grow together with the cambium of a

different tree. The cambium is relatively easy to see if you have

good eyes since it tends to be bright green. Your goal is to make

sure the cambium of your scionwood lines up with the cambium of the

tree you're grafting onto.

Your gut reaction will

probably be to try to make the scionwood fit flush against the side of

the tree being grafted onto, but that's not quite right. As a

tree grows, it not only expands the xylem (the woody part in the

center), but also the phloem (which turns into the bark). So, the

cambium is going to  be a little deeper into the

older tree being grafted onto than it is on the little twig of

scionwood. That's why most people recommend making sure your

scionwood is slightly indented as you look at your graft from the side.

be a little deeper into the

older tree being grafted onto than it is on the little twig of

scionwood. That's why most people recommend making sure your

scionwood is slightly indented as you look at your graft from the side.

One way to hedge your

bets is to insert your scionwood at a slight angle, as is shown in the

drawing to above, so that the cambial layers intersect somewhere. This type of angled

scionwood placement won't give you as strong a connection, but is

better than nothing if you're not sure you'll get your cambial layers

lined up otherwise.

One last note on

scionwood placement (which you really should have considered when

making your cuts) --- most sources recommend that the first bud on your

scionwood sits just above the top of the tree being grafted onto.

If you had extra scionwood length, now is a good time to cut each one

down to two or three buds. Stay tuned for tomorrow's post, in

which I'll explain how to seal the cut surfaces.

| This post is part of our Grafting Experiment lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Lucy is still making holes in

the chicken pasture fence.

Arghhh...

When I tested the electric

fence line we installed today it seemed a little weak. I first

thought we might be reaching the limit of distance, but the

instructions say it should go up to 1500 feet.

I'm thinking I may have not

tightened down the wing nut enough where the two wires attach. Either

that or maybe the unit is suffering some sort of power decline?

Even though chickens get most

of their nutrition from insects and

seeds, tender young plants provide lots of vitamins and minerals (and a

surprising amount of protein). That's why I was thrilled to

notice grasses beginning to grow in several spots around the farm in

the last week.

Even though chickens get most

of their nutrition from insects and

seeds, tender young plants provide lots of vitamins and minerals (and a

surprising amount of protein). That's why I was thrilled to

notice grasses beginning to grow in several spots around the farm in

the last week.

One of our newest

pastures is under the trees where "normal" grasses seldom grow.

However, a few clumps of bunchgrasses are evident. The chickens

ate them down to nubbins, but this clump has already started to regrow

in the last week since the chickens were turned out of the

pasture. Does anyone have a clue what kind of grass this might be?

I'm relatively sure that

the tender-leaved grasses that pop up in closely mown parts of our yard

and in the treeless pastures are bluegrass. Bluegrass feels

delightful to bare feet, and  also stays tender enough for

chickens to enjoy even in the summer, so I'm pleased it sprouts

anywhere we open up the canopy and mow regularly.

also stays tender enough for

chickens to enjoy even in the summer, so I'm pleased it sprouts

anywhere we open up the canopy and mow regularly.

New bluegrass leaves

started to push up through the dead brown litter in the garden aisles a

week or so ago, but regrowth started sooner in more protected

areas. For example, this patch of green is underneath where we

usually park the truck --- I assume that big old hunk of metal

mitigated some of winter's cold and let the grass grow faster.

But the most vigorous

early spring grasses aren't in our cultivated areas at all. I

looked out across the floodplain on Monday and noticed a huge patch of

green in what we fondly term "the alligator swamp" --- a waterlogged

oxbow off our creek.

I don't know if these

water-loving grasses are a species that always gets a jumpstart on

spring, or whether the thermal mass of the water is responsible for the

vibrant greenery. But maybe that explains why the chickens have

been hanging out in the damp area on the far side of the barn rather

than following the sun in the early morning the way they did a few

months ago.

I don't know if these

water-loving grasses are a species that always gets a jumpstart on

spring, or whether the thermal mass of the water is responsible for the

vibrant greenery. But maybe that explains why the chickens have

been hanging out in the damp area on the far side of the barn rather

than following the sun in the early morning the way they did a few

months ago.

Learning the patterns of

grass growth is essential to proper pasturing. For example, I'm

planning all of my broilers to hit the ground running just as the grass

is reaching its peak. However, I've still got a long way to go

before I thoroughly understand our sod, and grass species ID is

clearly near the top of the to-learn list. Has anyone tried out

various grass field guides and settled on one that helps from a

pasturing point of view?

The final step in any

grafting project is to seal all cut surfaces so they don't dry out

before they're able to heal. Professionals buy grafting tar or

parafilm, but I wanted to try some materials I already had on hand.

The trick with using

beeswax or some other homegrown compound to seal your grafting cuts is

that hot wax can damage the cambium of the tree. I opted to dab

on mostly melted beeswax, figuring it wouldn't hurt the tree as long as

it didn't burn my finger when I dripped a bit of melted wax on my

skin. This is the most experimental part of my project, though,

since no one else seems to use straight beeswax to seal their wounds.

One recipe for making your

own sealing wax includes 1 part raw linseed oil, 2 parts beeswax, and 4

parts powdered rosin. Someone else kneaded mineral oil into hobby

clay to make a sealing compound. I suspect both of these

compounds would be flexible enough that you could paint them on cold,

which would delete the potential heat problem.

One recipe for making your

own sealing wax includes 1 part raw linseed oil, 2 parts beeswax, and 4

parts powdered rosin. Someone else kneaded mineral oil into hobby

clay to make a sealing compound. I suspect both of these

compounds would be flexible enough that you could paint them on cold,

which would delete the potential heat problem.

No matter which compound

you use, you want to cover the tips of each piece of scionwood, then

liberally dab wax or tar on the top and sides of the cleft tree

trunk. Do your best to be more careful than I was and not cover

up any of the precious buds on the scionwood --- I had to pick a bit of

wax off with my fingernails.

Some sources suggest

tying a plastic bag over the top of the grafted area when you're done

for an added layer of protection. It sounds like you can use

carpenter's glue to seal the graft as long as you top it off with

aluminum foil and then a plastic bag. However, plastic bags

require more work since you'll need to keep them out of direct sunlight

so they don't heat up, and then you have to take the bag off once the

scionwood starts to grow. I'm thinking of deleting the plastic

bags, actually --- what do you think?

Despite taking five long

posts to tell you about this, I performed a cleft graft on two pear

trees in less than an hour, counting all of my practice cutting

time. So don't be scared away from the process. I'll report

back this summer as our scionwood (hopefully) starts to grow.

| This post is part of our Grafting Experiment lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

So I went out and tightened

down the wing nut where the two wires meet and at first I didn't notice

any change....just a low level prickly feeling when you touched

it....and then a few minutes later while I was taking a few pictures it

must have had time to charge up or something because ZOWWIE!!!!....the

darn thing jolted me so hard I dropped the camera, which softly landed

in a bed of straw mulch.

My mom sent me an email

that tickled my fancy a week or two ago:

She

got interested in the idea of dandelions as an indicator of the

progression of spring, and stumbled across a Rodale pamphlet with a

chapter on "Using phenology to make planting decisions". The text

suggested paying attention to honeysuckle and lilacs "because of their

wide adaptability to different geographical areas, and their

reliability in making consistent responses to varying weather

conditons".

She

got interested in the idea of dandelions as an indicator of the

progression of spring, and stumbled across a Rodale pamphlet with a

chapter on "Using phenology to make planting decisions". The text

suggested paying attention to honeysuckle and lilacs "because of their

wide adaptability to different geographical areas, and their

reliability in making consistent responses to varying weather

conditons".

By noticing when the

indicator plants' leaves and flowers emerge, you can get an idea about

when to plant certain crops. For example, the Rodale pamphlet

recommended planting cool season crops (like peas) when lilac shows its

first leaves and waiting to plant warm season crops (like tomatoes)

until the lilacs are in bloom. Of course, oak

leaves are another classic indicator plant.

I loved Mom's idea of

testing indicator plants against soil temperature. What's your

most dependable indicator plant? Have you noticed whether it

responds to day length, air temperature, or soil temperature?

After more study I'm starting

to think tightening the wing nut was only part of the problem I was

having with the electric fence being weak.

What I missed until looking

at yesterdays picture was the washer

placement. It seems clear now that more surface area touching the

opposite wire means more charge.

Another mistake may have been

wrapping too many strands, which I think created gaps in the

connection. My new method is a simple bend that wraps around the bolt

without making a complete loop.

I've

tried to explain no-till

gardening to our

dog, but I just don't thinks she gets it. Last week, she tore up

a dozen beds in the mule garden, even breaking into the quick

hoops to continue

her vole hunt. She wreaked havoc on our young

onion beds, broke

the flats containing the extra transplants, but at least left me enough

living seedlings to replace her casualties.

People

always say that the hardest folks to convert are your own family, so I

guess it's no surprise Lucy won't practice what I preach. At

least I found the uprooted turnips while most of them were still edible

enough to toss into a pot of lentil stew.

People

always say that the hardest folks to convert are your own family, so I

guess it's no surprise Lucy won't practice what I preach. At

least I found the uprooted turnips while most of them were still edible

enough to toss into a pot of lentil stew.

And, heck, now I know

that I don't need a pig if I ever want colonizer

livestock. I

can just turn Lucy into the paddock with a few rodents and watch the

dirt fly.

The first round of chicks

have out grown their blue Rubbermaid tub and graduated to the

new mini

coop.

Sometimes I wonder if a fake

mother hen would make new born chicks feel more secure in the first few

weeks when life is so dangerous and big.

Most pasture farmers know

that endophytes are hard on animals, causing problems ranging from

pregnancy issues to staggers. Other ailments include slow growth,

hoof gangrene, and a hard time handling hot weather. But what are

endophytes?

Most pasture farmers know

that endophytes are hard on animals, causing problems ranging from

pregnancy issues to staggers. Other ailments include slow growth,

hoof gangrene, and a hard time handling hot weather. But what are

endophytes?

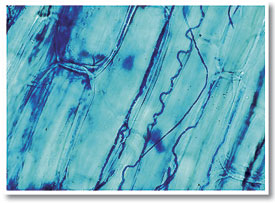

If you're a ryegrass or

fescue plant, endophytes are the coolest thing since sliced

bread. These symbiotic fungi --- Neotyphodium coenophialum in fescue and Neotyphodium

lolii in ryegrass

--- spend their whole lives inside a single grass plant, eating sugars

the plant hands over willingly. In exchange, the endophytes

produce alkaloids that deter insects and keep grazers like deer, sheep,

cattle, and horses from gorging too much on the grass.

When

scientists discovered the dangers posed by endophytes, they got to work

breeding endophyte-free grasses. However, they soon learned that

plants share their sugars with endophytes for a reason --- without the

endophytes, fescue and ryegrass tend to die out  quickly. (The paired

photos show an ailing stand of endophyte-free fescue on the left and a

thriving stand of endophyte-infected fescue on the right.) Now

scientists have changed their tactics and are trying to breed

endophytes that produce the alkaloids that keep bugs at bay (peramine)

without making ergovaline (which is the most problematic alkaloid for

livestock). If you haven't planted a special (read: expensive)

strain,

though, chances are your ryegrass and fescue are infested with the

common endophyte varieties.

quickly. (The paired

photos show an ailing stand of endophyte-free fescue on the left and a

thriving stand of endophyte-infected fescue on the right.) Now

scientists have changed their tactics and are trying to breed

endophytes that produce the alkaloids that keep bugs at bay (peramine)

without making ergovaline (which is the most problematic alkaloid for

livestock). If you haven't planted a special (read: expensive)

strain,

though, chances are your ryegrass and fescue are infested with the

common endophyte varieties.

Luckily, you can work

around endophytes in many situations, giving your grasses the boost

they need to thrive without hurting your livestock's health. The

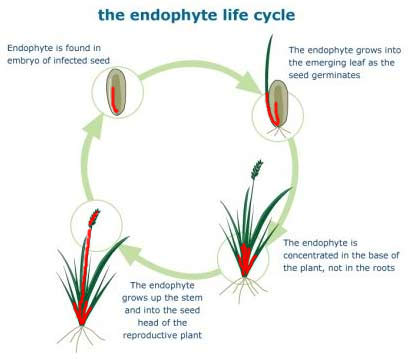

trick is to understand the life cycle of an endophyte-infected grass.

The red lines in this diagram

show the general location of endophytes within a plant. (No, you

can't actually see anything with your naked eye.) The fungus

comes along for the ride when a seed drops off the parent plant,

spreads up into the lower portion of the leaves, and then heads up the

flower stalk to infect new seeds.

The red lines in this diagram

show the general location of endophytes within a plant. (No, you

can't actually see anything with your naked eye.) The fungus

comes along for the ride when a seed drops off the parent plant,

spreads up into the lower portion of the leaves, and then heads up the

flower stalk to infect new seeds.

As a pasture maintainer,

this life cycle tells you how to ensure your livestock don't munch on

too much of the problematic fungus. If you don't overgraze your

pastures and do graze often enough that the grasses don't want to go to

seed, your livestock probably won't get enough endophyte into their

systems to cause problems. No wonder endophyte-related illnesses

tend to show up in summer or fall, when our cool season grasses are

declining and we're forced to graze them down to nubbins.

My final

endophyte-related question was --- do endophytes harm chickens? A

quick search of the internet doesn't turn up much definitive

information. Chickens fed on a diet of endophyte-infected fescue

seeds did worse than those fed on a diet of endophyte-free fescue

seeds, but other sources suggest that, in the wild, chickens don't eat

enough grass to get sick. Fescue is generally too tough for

chickens to digest, but I did plant some annual

ryegrass in one of

our pastures since these tender leaves are supposed to be much more

palatable to non-ruminants. I'll make sure to treat the ryegrass

carefully and will let you know if I see any problems.

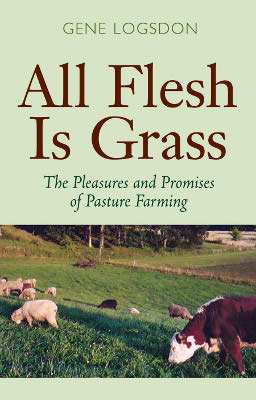

Gene Logsdon's All

Flesh is Grass

doesn't quite bring rotational grazing to the backyard, but the

author's focus on people with 2 to 100 acres who are growing meat for

personal consumption makes his ideas accessible to the average

homesteader. Don't get me wrong --- the intense information in Greener

Pastures on Your Side of the Fence and in Greg

Judy's mob grazing workshop were invaluable as I

continue to plan our pasturing setup, but it's also helpful to hear

from someone farming on a much smaller scale.

Gene Logsdon's All

Flesh is Grass

doesn't quite bring rotational grazing to the backyard, but the

author's focus on people with 2 to 100 acres who are growing meat for

personal consumption makes his ideas accessible to the average

homesteader. Don't get me wrong --- the intense information in Greener

Pastures on Your Side of the Fence and in Greg

Judy's mob grazing workshop were invaluable as I

continue to plan our pasturing setup, but it's also helpful to hear

from someone farming on a much smaller scale.

What does Logsdon's

pasture setup look like? His 32 acre farm in northern Ohio has

about 15 acres devoted to pasture, on which he raises cows, sheep, and

chickens for his family. The farm is divided into seven paddocks,

each of which is about two acres in size, and he lets livestock spend

about three weeks in each area before rotating them to the next paddock

in line. (Yes, it

is suboptimal to keep your livestock in a paddock for more than six days, but sometimes the

homesteader doesn't need to reach peak efficiency if he wants to keep

his sanity.)

Most of Logsdon's

pastures are a permanent mixture of bluegrass, ryegrass, white clover,

and tall fescue. However, he also rotates a few paddocks through

annuals (and short-lived perennials) like red clover, wheat, corn,

alfalfa, timothy, and ladino clover. Using all of these pasture

plants, Logsdon is able to start his animals on pasture in late March

and keep them there until they finish eating the stockpiled

grass in January or

February. Since he plans calving and lambing around the pasture

year, selling or eating meat animals in December, he has relatively few

livestock to feed during the nonpasture month(s).

This week's lunchtime

series will walk you through Logsdon's operation in more depth. I

highly recommend his book for the firsthand information on plant

polycultures, but have to warn you that if you have little patience for

pseudoinformation, you should skip

over the anecdotes that make up the chapters on individual types of

animals. I got bogged down in the sheep chapter for about three

months before plodding on through to the intriguing tidbits in the

second half of the book.

| This post is part of our All Flesh is Grass lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Chicks will stand in their

food dish if given the opportunity.

We've experienced this year after year, but always had bigger problems

to solve and payed the price by just adding more feed when they

scratched their way to the bottom of the dish.

This new automatic chick feeder seems to be big enough for our flock,

and so far none of them have figured out how to climb inside.

I figured that since Weekend

Homesteader is all grown up and ready to go into print, she deserved

her own page. Those of you who want to hear the blow by blow, be

sure to subscribe to the RSS feed.

I figured that since Weekend

Homesteader is all grown up and ready to go into print, she deserved

her own page. Those of you who want to hear the blow by blow, be

sure to subscribe to the RSS feed.

Meanwhile, I probably won't be blogging over here about Weekend

Homesteader until I have books in my hand. But I couldn't help

sharing the cover.

What do you think? I'm conflicted,

but I figure the publisher knows much more about covers than I do, so I

agreed to let it go to press as is.

One of my favorite parts of All Flesh

is Grass is

Logsdon's fencing advice. Every other book and blog I've read

about rotational grazing sings the praises of temporary electric

fences, but Logsdon and I both aren't

fans of electric fences.

One of my favorite parts of All Flesh

is Grass is

Logsdon's fencing advice. Every other book and blog I've read

about rotational grazing sings the praises of temporary electric

fences, but Logsdon and I both aren't

fans of electric fences.

Logsdon started out his

operation with woven wire fences, mostly because he found a lot of free

materials. He uses heavy wooden posts that are nearly eight feet

long, driven two and a half to three feet in the ground and separated

by fifteen feet along the fenceline. As an old-fashioned farmer,

he likes posts he can cut himself --- red cedar, black locust, catalpa,

osage-orange --- but he will also split old electric poles or

railroad ties into thinner sections to use as fenceposts. His

corner posts are eight inch in diameter treated lumber, nine feet long,

sunk four feet into the ground, and braced. After pulling the

woven wire taut between these fence posts (and, yes, I was exhausted

before I even got to that part of the description), Logsdon adds a

strand of electric fence over top of the woven wire as a final line of

defense.

All of that said,

Logsdon is now changing over to livestock panels. These four foot

tall and sixteen feet long fence sections can be used on uneven

terrain, don't collapse if a tree limb falls on them, are modular and

easy to replace piecemeal, and are rated to last twice as long as woven

wire fences (for twice the price, of course). Installation is

easy --- just set a post every eight feet, with panels overlapping two

inches at the each end. After a year of closing up the holes Lucy

made in our chicken wire fences (and watching Mark swear as he tried to

stretch the fences up hills), I'm wishing we'd gone the livestock panel

route as well. Maybe for our next fences!

While we're on the topic of

fencing, I should add that one benefit of permanent fences is that you

can plant trees long the fenceline, adding another layer of

productivity to the pasture while making animals less likely to break

through. Logsdon has tried many different types of trees and

sings the praises of apples and peaches (both grown from seed), pears,

thornless honey locusts, and chinquapin oaks for

providing extra food for livestock. Red cedars make a good

windbreak and don't taste good to livestock, so you don't have to fence

the animals away from the young trees as carefully, plus you can use

them to make fence posts.

While we're on the topic of

fencing, I should add that one benefit of permanent fences is that you

can plant trees long the fenceline, adding another layer of

productivity to the pasture while making animals less likely to break

through. Logsdon has tried many different types of trees and

sings the praises of apples and peaches (both grown from seed), pears,

thornless honey locusts, and chinquapin oaks for

providing extra food for livestock. Red cedars make a good

windbreak and don't taste good to livestock, so you don't have to fence

the animals away from the young trees as carefully, plus you can use

them to make fence posts.

On the other hand,

Logsdon has tried some trees he wouldn't plant in a pasture

again. Weeping willows and black walnuts love to drop limbs all

over the fenceline, black locust leaves are toxic to animals, and

cherries not only have poisonous leaves, they also don't make very

tasty fruits if grown from seed. In addition, even if you plant

the best-behaved  trees,

you'll need to spend a day every year cutting out grapevines, poison

ivy, and tree seedlings growing along your fencerow, but you'd spend

the same time weed-eating if you didn't have trees.

trees,

you'll need to spend a day every year cutting out grapevines, poison

ivy, and tree seedlings growing along your fencerow, but you'd spend

the same time weed-eating if you didn't have trees.

I've always liked the

idea of turning fencelines into productive zones, but with our small

pastures, trees are out of the question. However, when I bought

the scionwood

for our pear tree, I

threw in a couple of shrubs that are supposed to make good, thorny

hedges while providing edibles for chickens --- Rosa

rugosa and

Siberian pea shrub. Meanwhile, the timber

bamboo (Phyllostachys

vivax) that I

planted last year seems to be holding its ground. Maybe in

another five years or so, our fences will be lost in a sea of edible

and beautiful greenery.

| This post is part of our All Flesh is Grass lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Quick

hoop protection no longer needed?

We're crossing our fingers,

but at the same time we'll keep the hoops up and the Agribon material handy just in case.

I let spring creep up on

us without telling you. The elderberry leaves have been poking

out of their buds for weeks now (although not getting terribly far),

and I noticed the first  peas

slipping up through the soil last week. Meanwhile, the Egyptian onions are growing so fast my

frequent cuttings become invisible by the next day.

peas

slipping up through the soil last week. Meanwhile, the Egyptian onions are growing so fast my

frequent cuttings become invisible by the next day.

We also started eating

the first spring lettuce, but it wasn't quite as much of an event as

usual since we've been enjoying homegrown salads all winter. It

is fun to switch our salad greens from primarily kale to lettuce,

though, since that frees up the greens for sauteing.

I saw blooming spring

beauties and spicebushes (not pictured) while walking Lucy Tuesday, but

the real event was ground dry enough (in spots) to wander around

barefoot. With beautiful weather dominating the 10 day forecast,

I can't help but wonder if the floodplain might not become passable in

a week or two.

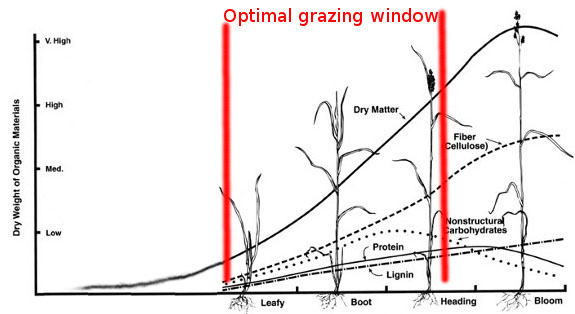

The rest of this week's

lunchtime series is an overview of forage plants that match the three

pasture seasons --- spring/fall (this post), summer, and winter.

You should keep in mind that specifics like this are very location

specific, so if you live in the Deep South or in another area where

warm season (rather than cool season) grasses dominate, you should take

everything I write with several grains of salt. The closer you

live to Gene Logsdon's home base in northern Ohio, the more likely his

suggestions are to fit your pasture like a glove.

The rest of this week's

lunchtime series is an overview of forage plants that match the three

pasture seasons --- spring/fall (this post), summer, and winter.

You should keep in mind that specifics like this are very location

specific, so if you live in the Deep South or in another area where

warm season (rather than cool season) grasses dominate, you should take

everything I write with several grains of salt. The closer you

live to Gene Logsdon's home base in northern Ohio, the more likely his

suggestions are to fit your pasture like a glove.

In Logsdon's (and our)

location, spring is when pasture plants are at their peak, with a

lesser peak ocurring in the fall. You'll plan your meat animals

to match these peaks and (if your operation is big enough) will also

use the extra growth to make hay (or stockpiled

grass) for the

winter. So what do you plant in those spring/fall paddocks?

Logsdon makes a good case for

not planting at all. His experience (and mine) has been that if

you open up the tree canopy and mow close to the ground regularly, bluegrass will eventually dominate

your pastures. You might or might not need to plant the white

clover that works

so well to round out the pasture polyculture.

Logsdon makes a good case for

not planting at all. His experience (and mine) has been that if

you open up the tree canopy and mow close to the ground regularly, bluegrass will eventually dominate

your pastures. You might or might not need to plant the white

clover that works

so well to round out the pasture polyculture.

A less permanent

alternative is to plant ryegrass in the place of the

bluegrass that springs up naturally. Ryegrass is a bit taller

than bluegrass, so it may shade out your white clover (unless you seed

specially formulated clover varieties that can handle the more

aggressive grass), and even the perennial ryegrass versions need to be

reseeded at intervals. On the other hand, ryegrass might make up

for the extra effort since it produces more dry matter per acre than

bluegrass does and establishes quickly. Both bluegrass and

ryegrass are among the most palatable grasses in most livestocks'

estimation, but ryegrass

is often infected with an endophyte.

Ryegrass and bluegrass are

managed about the same. As I learned the hard way last year, you

need to graze or mow them hard and repeatedly in the spring and early

summer so they don't go to seed, since fruit production makes the

grasses less palatable and slows their growth considerably. You

can graze the pasture down to one inch, then let the grass regrow to

four to six inches before turning your animals back in. This

happens pretty quickly in the spring, and is one of the advantages of

short grasses.

Ryegrass and bluegrass are

managed about the same. As I learned the hard way last year, you

need to graze or mow them hard and repeatedly in the spring and early

summer so they don't go to seed, since fruit production makes the

grasses less palatable and slows their growth considerably. You

can graze the pasture down to one inch, then let the grass regrow to

four to six inches before turning your animals back in. This

happens pretty quickly in the spring, and is one of the advantages of

short grasses.

Drought, more than heat,

is what prevents bluegrass and ryegrass from barreling on through the

summer, so Logsdon suggests that it might be worth your while to

irrigate your pastures to keep them productive. I noticed that

the paddocks directly downhill from my oft-watered vegetable garden did

much better last summer than grasses in other areas.

Although bluegrass and

ryegrass aren't really winter grasses, you can let them grow in the

fall to stockpile forage for the winter. Logsdon notes that the

dense root structure of the bluegrass/clover sod prevents major damage

when smaller livestock are turned into the pasture in wet weather, and

he finds that the disturbed soil in hoofprints actually helps clover

gain more of a foothold. Stay tuned for later posts detailing

summer and winter alternatives to the bluegrass/clover pasture.

| This post is part of our All Flesh is Grass lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I'm starting a new

Appalachian myth.

A garden

gate built on Pi day will be magically impervious to deer.

In a perfect world, I'd mulch

my vegetable garden with straw and my woody perennials with well

composted wood chips (or maybe leaves). If I needed to lay down a

kill mulch, I'd use corrugated cardboard as the kill layer. (Weekend

Homesteader: July gives the science behind these choices, but the

short version is --- it just makes the plants happy.)

In a perfect world, I'd mulch

my vegetable garden with straw and my woody perennials with well

composted wood chips (or maybe leaves). If I needed to lay down a

kill mulch, I'd use corrugated cardboard as the kill layer. (Weekend

Homesteader: July gives the science behind these choices, but the

short version is --- it just makes the plants happy.)

But we don't live in a

perfect world. Even though I'd been carrying in cardboard from

the parking area for a week, I managed to use up every lick of the

delicious kill mulch  material in one busy

Tuesday. Plus, I'd already mulched with the leaves my mother

snagged on her city curb and didn't want to spend all afternoon raking

more out of the woods.

(The piles of

wood chips at our

parking area are mellowing very nicely, but no way am I carrying that

heavy organic matter in by hand.)

material in one busy

Tuesday. Plus, I'd already mulched with the leaves my mother

snagged on her city curb and didn't want to spend all afternoon raking

more out of the woods.

(The piles of

wood chips at our

parking area are mellowing very nicely, but no way am I carrying that

heavy organic matter in by hand.)

So, having run out of my

favorite mulches, I used...whatever. Wednesday found me laying

down kill mulches alongside the black raspberries

with junk mail and then topping it all off with straw. Yes, I've

had mixed

results with paper

in the past, but I figure woody  perennials

can handle the high carbon material better than a vegetable garden

could, and I also carefully pulled out all the slick pages (although I

left some colored newsprint in). I figure the high nitrogen straw

will help counteract the high carbon kill mulch (and will add nitrogen

to the soil this summer as the straw rots, making up for the fact that

I skimped a bit on manure --- we're running out of that too).

perennials

can handle the high carbon material better than a vegetable garden

could, and I also carefully pulled out all the slick pages (although I

left some colored newsprint in). I figure the high nitrogen straw

will help counteract the high carbon kill mulch (and will add nitrogen

to the soil this summer as the straw rots, making up for the fact that

I skimped a bit on manure --- we're running out of that too).

On the plus side, many

gardeners believe that it's a good idea to change your mulch and

compost source every year so your garden never gets overloaded (or

deficient) in one nutrient. So maybe I should be telling you I

thought all this through and decided a year under straw would make the

soil in our berry patch more well-rounded? Naw --- that's too

much like bright

yellow boots.

Bluegrass

or ryegrass with white clover makes a great spring and fall

pasture, but where do you put your hungry critters during the summer

slump? Gene Logsdon offers a slew of possibilities, ranging from

semi-perennial legumes to warm season grasses and even weeds.

Bluegrass

or ryegrass with white clover makes a great spring and fall

pasture, but where do you put your hungry critters during the summer

slump? Gene Logsdon offers a slew of possibilities, ranging from

semi-perennial legumes to warm season grasses and even weeds.

In his own pasture

setup, Logsdon focuses on alfalfa, red clover, and ladino clovers to

fill in the summer lull, planting these short-lived perennial legumes

in rotation with winter crops like grains. When choosing one of

these legumes, keep in mind that alfalfa is the most drought tolerant

and produces more biomass than any other legume if it's happy, but that

it hates clay and can't be planted  in the same spot for several years after the

stand dies out. Red clover outperforms alfalfa on heavy

soils and in cold, moist climates, finding favor in the Corn Belt, the

Northeast, and the mid-South. Ladino

clover is the

most palatable of these tall legumes and can handle heavy, wet soil,

but produces less hay per acre, won't survive drought, and requires

reseeding most often.

in the same spot for several years after the

stand dies out. Red clover outperforms alfalfa on heavy

soils and in cold, moist climates, finding favor in the Corn Belt, the

Northeast, and the mid-South. Ladino

clover is the

most palatable of these tall legumes and can handle heavy, wet soil,

but produces less hay per acre, won't survive drought, and requires

reseeding most often.

All three legumes are

managed about the same. In the Deep South, red and ladino clovers

are grown as annuals, but elsewhere the legumes are perennials that

should be surface seeded in winter, then given several months to get

established. You can begin to cut or  graze once the plants begin

to bloom, then continue to cut or graze at the same stage until

September, at which point the plants must be allowed to put on some

mass so they will survive the winter.

graze once the plants begin

to bloom, then continue to cut or graze at the same stage until

September, at which point the plants must be allowed to put on some

mass so they will survive the winter.

Timothy can be mixed with the

legumes (especially red clover), but if you combine the plants, it's

best to gauge grazing or cutting time by the legume since timothy grows

more slowly. Orchardgrass is sometimes mixed with

alfalfa in the lower Corn Belt and mid-South, but the grass becomes

unpalatable quickly in the spring if you're not careful. Finally,

smooth

bromegrass is

often combined with alfalfa in the North since the grass and legume

have similar drought resistance.

At the other end of the

country, you might consider planting a paddock or two to warm season

grasses for the summer months. Quackgrass, crabgrass, and foxtail are weeds that spring up all

by themselves in cultivated ground, while bermudagrass (also a weed by many folks'

estimation) will take over in the Deep South. Sorghum-sudangrass

hybrid is often

planted for high production pastures in midsummer, but the leaves are

toxic when less than a foot tall, which gives the plant limited utility

for grazers like chickens who like tender forage. Although a

legume instead of a grass, lespedeza is a possibility in the

South, but can be a problem weed that becomes unpalatable if not

managed carefully.

At the other end of the

country, you might consider planting a paddock or two to warm season

grasses for the summer months. Quackgrass, crabgrass, and foxtail are weeds that spring up all

by themselves in cultivated ground, while bermudagrass (also a weed by many folks'

estimation) will take over in the Deep South. Sorghum-sudangrass

hybrid is often

planted for high production pastures in midsummer, but the leaves are

toxic when less than a foot tall, which gives the plant limited utility

for grazers like chickens who like tender forage. Although a

legume instead of a grass, lespedeza is a possibility in the

South, but can be a problem weed that becomes unpalatable if not

managed carefully.

Corn isn't exactly a pasture

plant, but Logsdon suggests a method to work the grain into your

pasture rotation without harvesting any of the ears yourself. You

can turn lambs into the pasture to eat the lower leaves and weeds when

the corn is above their heads, then replace them with hogs who harvest

the grain when the plants are mature. Finally, sheep and cows

munch on the fodder (and dropped ears of corn) over the winter.

In his chapter on weeds,

Logsdon tosses out the idea of a temporary ley for summer

pasture. Newman Turner's Fertility Pastures and Cover Crops recommends planting the

following combination for midsummer:

In his chapter on weeds,

Logsdon tosses out the idea of a temporary ley for summer

pasture. Newman Turner's Fertility Pastures and Cover Crops recommends planting the

following combination for midsummer:

- Alfalfa (6 pounds per acre)

- Chicory (6 pounds per acre)

- Timothy (6 pounds per acre)

- White clover (3 pounds per acre)

- Burnet (3 pounds per acre)

- Late-flowering red clover (2 pounds per acre)

- Meadow fescue (4 pounds per acre)

- Perennial ryegrass (12 pounds per acre)

- American sweet clover (2 pounds per acre)

- Sheep's parsley (2 pounds per acre)

- Carraway (1 pound per acre)

- Narrow-leaved plantain (1 pound per acre)

- Broad-leaved plantain (1 pound per acre)

Although Logsdon laughs