archives for 01/2012

Saturday afternoon, I

was itching for a walk, so I put on my hiking shoes and followed their

lead. They told me that it was too muddy to go down into the

floodplain without my muck boots, and wouldn't it be fun to chase the

sun up over the hill?

Eventually, the sun

angled me around onto the other hill, which overlooks our

homestead. As trashy as it may appear to most folks, this view of

our trailer and addition are pure beauty in my eyes

--- freedom for a grand total of $3,000. People keep asking me

when we're going to build a house and I look at them like they're

nuts. Why would I want to spend masses of money and/or time

building a larger space to keep clean (and use up prime growing

area?) Now, porches, a summer kitchen, a better roof, and perhaps

strawbale walls for additional insulation might make the cut...someday

when my gardening and writing projects get boring. (Ha!)

I got tired looking at

our trailer after a while and zoomed in on the garden. Here's the

shady front garden, half of it mulched with straw and the other half

with nearly dead oat

cover crops.

Perhaps you don't get the same pure joy I do out of watching things rot?

The mule garden was

still in nearly full sun, making the quick

hoops shine.

Our whole homestead is encircled by the protective arms of trees ---

young but beautiful. I'm looking forward to watching them grow up.

No New Year's

resolutions here. Just more of the same --- beauty, nourishment,

and most of all fun!

I

can't quite make up my mind whether I like our Light Sussex or

not. They're very different chickens from any we've had

before.

I

can't quite make up my mind whether I like our Light Sussex or

not. They're very different chickens from any we've had

before.

Although they do roost

on the perches sometimes, it took them months to even consider getting

up off the ground. And they still seem to think it's just fine to

bed down out in the woods if it's a clear night.

They're friendly as can

be --- almost too friendly. When the other flock, led by the

Australorp rooster, came up into the garden, I chased them away with

much hollering and Lucy action, and after a repeat performance they

didn't come back. Trying to chase the Sussex out of the garden

didn't go nearly as well --- they weren't really afraid of me even when

I ran straight at them.

The Sussex do seem to be

pretty good foragers, though. As with our

problematic winter-layers, I'm taking a wait and see

approach --- this time next year, I should be better able to report on

how well Light Sussex, Black Australorps, and Cuckoo Marans match my

homesteading criteria. I'm also interested to see whether hybrids

that we raise in the spring will show hybrid vigor --- lots of fun

breeding experiments ahead!

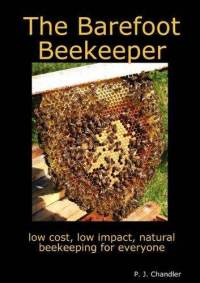

The demise

of both of our hives

this autumn pushed me to look deeper into sustainable beekeeping.

I've got a couple more books to read before I settle on a new method,

but The

Barefoot Beekeeper

by PJ Chandler was definitely a thought-provoking step in the right

direction. This week's lunchtime series will highlight the most

intriguing tips I learned about natural beekeeping (and, specifically,

top bar hives.)

The demise

of both of our hives

this autumn pushed me to look deeper into sustainable beekeeping.

I've got a couple more books to read before I settle on a new method,

but The

Barefoot Beekeeper

by PJ Chandler was definitely a thought-provoking step in the right

direction. This week's lunchtime series will highlight the most

intriguing tips I learned about natural beekeeping (and, specifically,

top bar hives.)

Before you rush out and

buy the book on Amazon, though, I should warn you that you might not

want to pay $21.61 for the paperback version. As reviewers there

rightly mentioned, the book is short and sweet --- so why not download

the ebook version from the author's website for $10 instead? And if you're

new to bees, you might want to wait on reading The

Barefoot Beekeeper

until you've pored over another beginner book and understand the basics

of bee biology and behavior.

Those caveats aside,

this book is the best natural beekeeping book I've read so far.

It delved much deeper into the issue than Natural

Beekeeping and gave

me much more food for thought. If you're an intermediate level

beekeeper, I think The

Barefoot Beekeeper

is a must-read.

| This post is part of our The Barefoot Beekeeper lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We've been taking this short cut to our trailer that saves about 3

minutes, but gets a little slippery on wet days.

I've had the idea for months

now to connect two small trees with a treated furring strip to make a

do it yourself hand rail, but kept forgetting to pick up the proper

hardware.

The total price with both U

bolts and the furring strip was around 7 dollars. Not a bad deal for

such a huge increase in safety.

I'd

love to tell you that converting from cold

frames to quick hoops

is the reason we're still enjoying fresh lettuce and greens at the

beginning of January.

I'd

love to tell you that converting from cold

frames to quick hoops

is the reason we're still enjoying fresh lettuce and greens at the

beginning of January.

But the truth is that

this winter has been strangely warm. Last year, our farm was

under a coat of snow for nearly the entire month of December and

the ground froze solid, but in December 2011 there were days when I

didn't even need to light the wood stove.

I hear we're in for an

arctic blast this week, and the snow is already falling. I'll let

you know whether the vegetables under the quick hoops survive once the

leaves thaw out and either liquify or keep growing.

Even though cold weather

is more work, I'm happy to see snow on the ground. (And maybe the

ground will freeze solid enough to drive the truck in?)

We've all heard that modern

beekeeping is in trouble, but The

Barefoot Beekeeper opened my eyes to problems that I hadn't

considered. Yes, large-scale beekeepers are mean to their bees,

stressing them out by stealing all of their honey and then feeding them

nutrient-free corn

syrup to get them

through the winter. The bees are often given access to only one

type of pollen, which leaves them perpetually malnourished, and they

have to put up with pesticides in their foraging grounds and even in

their hives. We truck bees across the nation, letting pests and

diseases piggy-back with the traveling bees and spread to other

areas. But there's a lot more to the decline of honeybees than

that.

We've all heard that modern

beekeeping is in trouble, but The

Barefoot Beekeeper opened my eyes to problems that I hadn't

considered. Yes, large-scale beekeepers are mean to their bees,

stressing them out by stealing all of their honey and then feeding them

nutrient-free corn

syrup to get them

through the winter. The bees are often given access to only one

type of pollen, which leaves them perpetually malnourished, and they

have to put up with pesticides in their foraging grounds and even in

their hives. We truck bees across the nation, letting pests and

diseases piggy-back with the traveling bees and spread to other

areas. But there's a lot more to the decline of honeybees than

that.

According to PJ

Chandler, the honeybee decline began nearly as soon as the Langstroth

hive was invented. For those of you who don't keep bees,

Langstroth hives are the wooden boxes you're likely to see in modern

apiaries. These hives are built out of wooden boxes with moveable

frames inside, the combination of which allows us to easily look

through a whole hive like paging through a book.

The Langstroth hive replaced

a much more lethal method, in which bees were kept in skeps that had to

be destroyed to harvest honey, so it was lauded as a great invention at

the time. However, Chandler argues that the Langstroth hive harms

bees in several ways:

The Langstroth hive replaced

a much more lethal method, in which bees were kept in skeps that had to

be destroyed to harvest honey, so it was lauded as a great invention at

the time. However, Chandler argues that the Langstroth hive harms

bees in several ways:

- Drastic temperature changes

--- In a natural hive, bees maintain a temperature of 94 degrees

Fahrenheit year round. When we open a Langstroth hive to page

through those frames, the temperature in the hive drops dramatically

even on a warm summer day. Did you know that varroa mites can

only reproduce at temperatures below 92 degrees? Chandler doesn't

have data to back this up, but his thesis feels sound --- the

temperature spikes in the Langstroth hive make it easier for mites to

gain a toehold, and the loss of heat also stresses out the bees who

have to work hard to bring the hive back up to optimal levels.

- Premade foundation --- As

I've written

previously, the cells in the foundation most beekeepers buy are

larger than the natural cell size. These large cells promote the

spread of varroa mites.

In addition, we have to

consider other aspects of modern beekeeping, such as the tendency to

concentrate our hives in large apiaries. As I mentioned about my native

bee nests, if you

house a lot of bees together, pests and diseases are much more apt to

spread through the populations. This makes me wonder if we

wouldn't be better off keeping our hives on opposite sides of the

property rather than close together.

In addition, we have to

consider other aspects of modern beekeeping, such as the tendency to

concentrate our hives in large apiaries. As I mentioned about my native

bee nests, if you

house a lot of bees together, pests and diseases are much more apt to

spread through the populations. This makes me wonder if we

wouldn't be better off keeping our hives on opposite sides of the

property rather than close together.

All of that said, most

of us aren't ready to go back to tearing skeps apart and killing

colonies just to get at the honey. Stay tuned for a modern

solution that still keeps the bees healthy.

| This post is part of our The Barefoot Beekeeper lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The non potable water line

froze up last night...the first time this winter.

Like Anna said, "the good

news is the drinking water didn't freeze".

It might be this gap that

formed where the tank meets the insulation box as the line arcs down

into a trench. I think I'll let this problem marinate for a few days

while I think of a solution. Maybe it'll be warmer then.

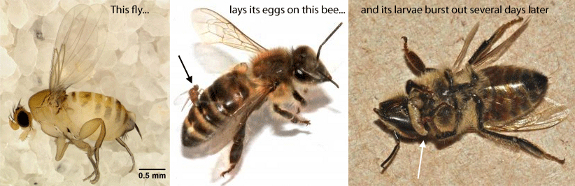

I've read at least half

a dozen different possible explanations for colony

collapse disorder,

but the Apocephalus borealis fly is a new one. This

tiny parasitic fly lays its eggs on honeybees, then the larvae nibble

their way into the bees' brains and eat them alive.

Unsurprisingly, bees

that fall prey to the Apocephalus

borealis flies

don't do so well. The bees get disoriented, abandon their hives,

and become stranded near bright lights.

Although lots of other

problems have been correlated with hives that succumb to colony

collapse disorder, the parasitic fly is unique in that it seems like it

might actually cause the symptoms we see. In addition, the timing

seems right --- in the San Francisco Bay area where the scientists

work, the fly visits honeybees from October to January and again in

late summer, right before the majority of hives come down with colony

collapse disorder.

So far, scientists are

simply adding Apocephalus

borealis to the

suite of problems that colony collapse disorder hives seem to share,

but I wouldn't be surprised if it turns out to be the primary culprit.

For

those of you who didn't take statistics, if two things always happen

together, that's a correlation. For example, Huckleberry likes to

sit in my chair whenever I want to sit there. Just because the

events are correlated, though, doesn't prove anything about causation

--- sometimes, two correlated events are simply caused by the a third

event we didn't think to measure. In my example, the third event

is a warm fire on a cold night --- the warmth attracts both me and

Huckleberry like moths to a flame. Returning to the serious case

of colony collapse disorder, just because we often see Nosema apis and Varroa destructor in the

sick hives doesn't mean these illnesses cause the disorder.

Before

I write about modern beekeeping methods that promote healthier bee

populations, let's take a step back and look at the way honeybees live

in the wild. Although some of them will move into the walls of

our houses (oops), most feral honeybees prefer to nest in hollow

trees. That means they are quite well insulated from the

elements, with thick wooden walls on the sides and an even thicker

"roof" above their heads.

Before

I write about modern beekeeping methods that promote healthier bee

populations, let's take a step back and look at the way honeybees live

in the wild. Although some of them will move into the walls of

our houses (oops), most feral honeybees prefer to nest in hollow

trees. That means they are quite well insulated from the

elements, with thick wooden walls on the sides and an even thicker

"roof" above their heads.

Nest chambers of

wild bees are vertically elongated cylinders with a

capacity of about 8 to 16 gallons. To give you a frame of

reference, the deep brood box that most Langstroth hives begin with has

a capacity of about 11 gallons, and beekeepers generally add on at

least one more deep brood box or two shallow supers. That makes

the wild bee hives sound small, but keep in mind that wild bees don't

sock away as much honey as we ask our bees to. Instead, they

swarm as soon as conditions in the hive start to get cramped, sending

out a daughter colony to make a new hollow her own.

Wild bee hives are usually at

or near the base of a tree and the

entrances are generally at the bottom of the hollow. Entrances

vary in size depending on the capacity of the tree, but range from

about 4 to 16 inches in diameter.

Wild bee hives are usually at

or near the base of a tree and the

entrances are generally at the bottom of the hollow. Entrances

vary in size depending on the capacity of the tree, but range from

about 4 to 16 inches in diameter.

The bees chew away rough

bark at the entrance to make a smooth landing

area, then they coat the inside walls with propolis. Combs are

fastened to the top and sides of the chamber, but the bees leave small

passageways along the edges to allow them to move around inside

easily. They put honey in the top of the combs, then pollen, and

care for their brood below.

Can we develop a hive

that allows for human management while keeping as

many of these wild bee characteristics as possible? Tomorrow's

post will suggest one possible compromise.

| This post is part of our The Barefoot Beekeeper lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I decided to upgrade my winter foot wear with some new Muck

boots.

These boots fit my feet like

no other boot I've ever encountered.

The stretchy material hugs

the upper ankle area in just the right spots while at the same time

having enough give to allow for a superior freedom of movement.

Remember two weeks ago when I

wrote that I was trying to combine

two roosters into one flock? I'm ready to

tentatively call the experiment a success.

Remember two weeks ago when I

wrote that I was trying to combine

two roosters into one flock? I'm ready to

tentatively call the experiment a success.

The Light

Sussex are still at

the bottom of the pecking order, but they're now allowed to eat side by

side with the grownups, as long as they mind their manners. As

usual, it was the head rooster who made the decision --- once he

started guarding the Sussex as well as his previous harem, they were in.

The only trouble with

the merger occurred last week when the Light Sussex cockerel led his

ladies up over the hill into the garden...and the Australorps and

Marans started following behind! Luckily, I saw the first white

heads peek up over the hill as I was cooking supper and ran out to

scare them out of their wits. There have been no repeat

performances.

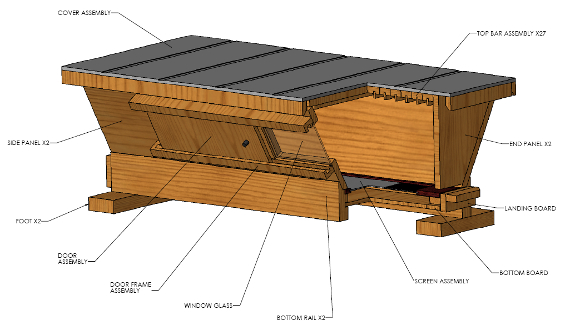

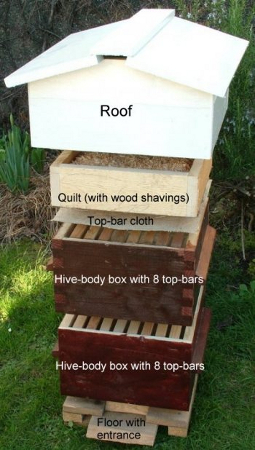

PJ

Chandler's solution

to the ills

of modern beekeeping

is the top bar hive. The hive is simply a long box with sides

that slant inwards and a lid that fits over top. Removable frames

are placed in the box a bit like the frames in a Langstroth hive, but

top bar frames are just what they sound like --- simply a top

bar. The bees create their own wax just like they do in foundationless frames, which allows them to build

at a more natural cell size.

One of the major selling

points of the top bar hive is that you can manage the hive in a very

unobtrusive fashion. The frames entirely enclose the space at the

top of the bees' nest area, so taking off the lid doesn't lower the

temperature inside much, nor does it bother the bees. The bee

colony is enclosed on the sides by two follower boards to keep them

from sprawling into the entire hive before they're ready, and

inspections can be as simple as sliding one follower board away from

the bees and peeking inside.

One of the major selling

points of the top bar hive is that you can manage the hive in a very

unobtrusive fashion. The frames entirely enclose the space at the

top of the bees' nest area, so taking off the lid doesn't lower the

temperature inside much, nor does it bother the bees. The bee

colony is enclosed on the sides by two follower boards to keep them

from sprawling into the entire hive before they're ready, and

inspections can be as simple as sliding one follower board away from

the bees and peeking inside.

Honey is usually

harvested one frame at a time, by cutting the entire comb off the

wooden frame. Although bees then have to redraw the wax on that

frame, cutting off the comb probably helps sanitize the hive, slowing

the buildup of diseases and pests. In general, you should

probably expect a bit less honey from a top bar hive than from a

Langstroth hive, but if that means your bees are healthier, I'd say the

trade is worth it.

Stay tuned for

tomorrow's post in which I'll discuss more of the pros and cons of top

bar hives, or check out our friend Everett's description of his top bar hive.

| This post is part of our The Barefoot Beekeeper lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Our

do it yourself heated chicken waterer froze up the other night.

It did fine earlier in the

month when it got down to 16 degrees, but it would seem like somewhere

around 10 is the "too cold" point.

Instead of increasing the length of the electric pipe heater we decided

to wrap it with Reflectix.

Maybe we'll get lucky and

have to wait till next winter to fully test out this new generation of

diy heated chicken waterers.

We're currently trying out

three varieties of kale that are supposed to be particularly cold hardy

--- Winterbor (from Johnny's and Territorial), Improved Dwarf Siberian

(from Territorial), and Red Russian (from Sweet Garden Organics.)

I planted three beds (each with all varieties) between August 6 and

August 26, then covered them with quick

hoops once cold

weather came along.

We're currently trying out

three varieties of kale that are supposed to be particularly cold hardy

--- Winterbor (from Johnny's and Territorial), Improved Dwarf Siberian

(from Territorial), and Red Russian (from Sweet Garden Organics.)

I planted three beds (each with all varieties) between August 6 and

August 26, then covered them with quick

hoops once cold

weather came along.

Germination

The first test was how

well the seeds germinated in summer heat. Red Russian barely came

up in two of the beds while Winterbor and Improved Dwarf Siberian each

didn't feel like growing in one bed. Given such a range of data

points, I'm going to say they're all potential trouble and might need a

bit of help if you're planting your fall garden during hot weather (as

you should be.)

Growth

Despite its name,

Improved Dwarf Siberian was the largest kale variety, growing a thick

stem and long leaves that sprawled out over the bed. Red Russian

turned out to be the diminutive cousin, keeping its growing tip near

the ground and politely adding a new leaf to its topknot now and then.

Winterbor looked a lot like

Dwarf Siberian at first, but once the weather got cold, Winterbor

started growing very ruffled leaves on short stems. My gut

feeling is that Winterbor is still growing (perhaps because the

condensed leaves are better able to handle cold?) while the other two

varieties are biding their time until spring. I don't have any

real data to back that up, though --- I only peek under the quick hoops

now and then.

Winterbor looked a lot like

Dwarf Siberian at first, but once the weather got cold, Winterbor

started growing very ruffled leaves on short stems. My gut

feeling is that Winterbor is still growing (perhaps because the

condensed leaves are better able to handle cold?) while the other two

varieties are biding their time until spring. I don't have any

real data to back that up, though --- I only peek under the quick hoops

now and then.

Beauty

If I lived in the city, I'd

plant all three of these kale varieties in my flower garden for winter

color. Red Russian might be the prettiest, but the beautiful

white veins on the Siberian and the ruffled Winterbor leaves are both

quite striking.

If I lived in the city, I'd

plant all three of these kale varieties in my flower garden for winter

color. Red Russian might be the prettiest, but the beautiful

white veins on the Siberian and the ruffled Winterbor leaves are both

quite striking.

Flavor

All three varieties of

kale taste so good right now that when I go out and snip leaves for

dinner, I eat a bunch before I get back inside. I've had to cut

way back on the balsamic vinegar I saute them in --- the leaves are

already so sweet that the sugary vinegar almost turns them into

dessert. If I had to choose the least tasty variety, it would

probably be Red Russian, but not by much.

Winter

hardiness

Only time will tell

which variety lasts longest into the winter. This factor will

probably be the most important in determining what we grow next year.

For those of you who

aren't kale fans, I'll post a roundup of our other winter

greens in another

post.

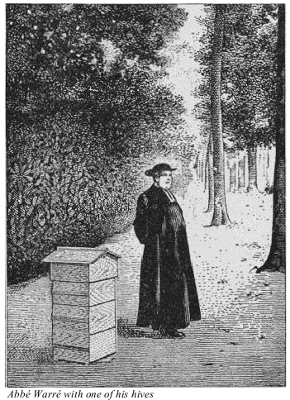

Less well known than the top

bar hive is another alternative beekeeping box --- the Warre hive,

sometimes called a "vertical top bar hive." I have to admit that

I haven't read Abbe Warre's Beekeeping for All yet (although you can

download it for free by following the link.) The information

below is drawn from The

Barefoot Beekeeper,

and is clearly biased toward the author's method.

Less well known than the top

bar hive is another alternative beekeeping box --- the Warre hive,

sometimes called a "vertical top bar hive." I have to admit that

I haven't read Abbe Warre's Beekeeping for All yet (although you can

download it for free by following the link.) The information

below is drawn from The

Barefoot Beekeeper,

and is clearly biased toward the author's method.

Although Warre used

smaller boxes, his technique is very similar to the modified Langstroth

method I've used in the past (although less intrusive.) Warre

stacked small boxes (12 inches square and a bit over 8 inches deep)

just like in a Langstroth hive, with the major difference being that

his frames were merely top bars with wax strips. When the first

box was full of bees and honey, Warre slipped an empty box underneath

(similar to my swarm prevention in years past, but without the extra checkerboarding.)

Where Warre's method differs

most from mine is that he didn't believe in delving into the hive at

intervals to page through the frames. In fact, he actually fixed

his frames in place with nails and didn't mess with the bees at

all. When they had moved down into the lower box, he would slip

another empty box underneath and then take away the top box, harvesting

all of the honey out of it at once.

Where Warre's method differs

most from mine is that he didn't believe in delving into the hive at

intervals to page through the frames. In fact, he actually fixed

his frames in place with nails and didn't mess with the bees at

all. When they had moved down into the lower box, he would slip

another empty box underneath and then take away the top box, harvesting

all of the honey out of it at once.

Warre's hive also

differs from Langstroth hives by containing a special, insulated

roof. Chandler argues that one of the problems with the

Langstroth hive is that the thin walls and roof cause condensation

within the hive in the winter, which makes the bees sick. Both

the Warre hive and the top bar hive deal with this problem by using

thicker wood and adding a sawdust layer to the inner lid.

PJ Chandler presented a

chart of pros and cons of the Warre hive versus his top bar hive, which you have to take with

a grain of salt since he clearly prefers the latter. Some

disadvantages he saw to the Warre method were:

- You have to store some boxes when not in use. The top bar hive is all one piece, so you block off empty areas but don't have to find space in the barn to store anything.

- More physical strength is

required for the Warre hive. Each time you add a new box

underneath, you have to hoist up the heavy box of bees and honey.

On the other hand, the

Warre hive did win in one respect:

- Very low maintence.

The top bar hive requires much more regular maintenance, with the

beekeeper often checking in and adding another frame twice a week

during heavy nectar flows. On the other hand, when you do work

with the Warre hive, you need to allot more time and physical strength

to the project.

I have to admit that I

think I'd drive myself nuts not being allowed to look into the hive

using Warre's method. On the other hand, there's always the

potential of creating viewing windows in the sides of the boxes, and if

the Warre method was better for the bees, I'd be tempted to try it.

Has anyone had

experience with Warre and/or top bar hives? Do you know of other

reasons to choose one over the other?

| This post is part of our The Barefoot Beekeeper lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I've tested out

a wide variety of work gloves over the last 8 years, but none of

them have come close to the quality these new John Deere gloves exude.

At 20 dollars they're a bit

over twice what I usually

like to pay, but I can already tell it's going to be worth it in

just the way the green stretchy material hugs the back of my hand.

The leather is thicker than

most work gloves without being too thick. Some gloves are plenty thick,

but next to impossible to grip anything with full confidence.

If Attracting

Native Pollinators

is the prettiest homesteading-related book of 2011, The

Small-Scale Poultry Flock

is the most thought-provoking. You can read my gushing review on

our chicken blog, along with my summary of Ussery's most interesting

points:

If Attracting

Native Pollinators

is the prettiest homesteading-related book of 2011, The

Small-Scale Poultry Flock

is the most thought-provoking. You can read my gushing review on

our chicken blog, along with my summary of Ussery's most interesting

points:

Breeding

small flocks of chickens --- Homestead-scale tips on

growing better birds.

Choosing

mother hens ---

Breeds and traits that make good broody hens.

Chicken

feed: Beyond the basics --- Chicken food groups,

mangels, and more.

Keeping chickens happy in the winter --- Ussery has a variety of

tips for dealing with this tough time of year.

Eating

the whole chicken

--- Parts of the bird you never knew were a delicacy. (Mountain

oysters, anyone?)

Diversifying

your poultry flock

--- Did you know you can train geese to weed your garden?

I would have made the

book a lunchtime series over here, but as you can see, I couldn't

summarize it in five posts. In fact, there are dozens of

fascinating tidbits in his book that I didn't manage to fit into a post

--- go read it!

Bays Mountain Park and

Planetarium is a 3500 acre nature preserve in Northeast Tennessee.

We hiked all the way up to

the fire tower today, and the view was well worth it.

I'm obsessed with my book

project. I

wake up with sidebars in mind and try to go to sleep with editing

decisions still rolling around in my head.

I'm obsessed with my book

project. I

wake up with sidebars in mind and try to go to sleep with editing

decisions still rolling around in my head.

The choice to put the

farm on hold and bulldoze my way through finishing the book has been a

good one for the manuscript, which is suddenly starting to look like

something I won't cringe to see in Tractor Supply. (I might even

go so far as to say I'm proud of it.) Unfortunately, just a few

weeks of sedentism is enough to remind me that my body craves motion.

So

I begged Mark to take me to Bays Mountain, where I could wear myself

out walking up to the fire tower. I had forgotten the tower was

so high (60 feet) and scarily open, and that the platform at the top

was so tiny. We didn't stay aloft long, but did try out the

homemade parachute some kid had left behind.

So

I begged Mark to take me to Bays Mountain, where I could wear myself

out walking up to the fire tower. I had forgotten the tower was

so high (60 feet) and scarily open, and that the platform at the top

was so tiny. We didn't stay aloft long, but did try out the

homemade parachute some kid had left behind.

After an engrossing

planetarium presentation, I realized I hadn't thought about the book

all day. Success! If editing takes much longer, we'll have

to go back for another round of nature meditation.

Increasing the height of our firewood chopping block by several inches

really helped the process.

I guess the optimal height

might vary depending on how tall one is and what size logs are being

cut, but for me the sweet spot is easier to hit with the chopping block

as high as the middle spot between the ground and your knee.

I promised you a peek under

the quick

hoops, but it took a

few days for the snow to thaw enough that the edges of the fabric

weren't frozen down. Winter lows have so far dropped to 10

degrees Fahrenheit, and we've had a few days where even the highs

remained below freezing --- a pretty good test.

I promised you a peek under

the quick

hoops, but it took a

few days for the snow to thaw enough that the edges of the fabric

weren't frozen down. Winter lows have so far dropped to 10

degrees Fahrenheit, and we've had a few days where even the highs

remained below freezing --- a pretty good test.

(You might want to read

about the

winter greens I'm growing first. Also, sorry

about the smudge on the camera lens.)

The bad news is that our

two varieties of Asian greens are pretty much kaput. They were

vigorous and productive in the fall, but I probably should have

harvested them harder and planned to completely eat  them up before cold weather

hit. Instead, I left a lot behind, hoping they'd be strong enough

to keep going into the winter, and most of those stored leaves turned

to inedible mush. Live and learn!

them up before cold weather

hit. Instead, I left a lot behind, hoping they'd be strong enough

to keep going into the winter, and most of those stored leaves turned

to inedible mush. Live and learn!

On the other hand, our

Black-seeded Simpson lettuce fared much better than I expected.

Although several leaves did get nipped, the majority of the plants look

healthy and ready to eat.

I didn't expect much from our

mustard since two varieties (Tendergreen and Broadleaf) had started to

bolt in the sunny December weather. I was wrong! The

mustard looked nearly untouched by the cold weather and Giant mustard

(the one variety that didn't bolt) has plenty of leaves to get us

through another couple of weeks until growth starts back up.

mustard looked nearly untouched by the cold weather and Giant mustard

(the one variety that didn't bolt) has plenty of leaves to get us

through another couple of weeks until growth starts back up.

Of course, the kale is still just as delicious

looking as it was last week, and our Hakurei turnips might actually be

putting out new leaves (although small and slowly.)

But here's a surprise ---

Fordhook Giant Swiss chard, out in the open with no quick hoop covering,

is still alive and doing pretty well! I didn't think the Swiss

chard even deserved protection because the colorful stalked varieties

I've grown previously have wimped out over the winter. But

reports that Fordhook Giant is a much more winter hardy variety seem to

be founded in fact. I guess we'll stick to the "ugly" variety and

turn Swiss chard into a winter standby!

reports that Fordhook Giant is a much more winter hardy variety seem to

be founded in fact. I guess we'll stick to the "ugly" variety and

turn Swiss chard into a winter standby!

All told, our greens and

lettuce beds have given us at least sixty meals so far --- pretty good

for the minimal effort of tossing down seeds, weeding and mulching

once, then erecting quick hoops. I thought I'd planted too many

beds, but there's really no such thing as too much fresh food in the

winter.

I took the cover off the tank box and

stuffed in some Reflectix to

fill in the gap.

Will be crossing my fingers

the next time it gets really cold.

Remember how I wrote that many

of our native bees nest in old beetle burrows in dead trees, stumps,

and branches?

I'd never noticed these holes before, but now that I've read about

them, I see them everywhere.

Remember how I wrote that many

of our native bees nest in old beetle burrows in dead trees, stumps,

and branches?

I'd never noticed these holes before, but now that I've read about

them, I see them everywhere.

The stumps we lazily

left strewn throughout the yard and garden are clearly one of the

sources of our huge native bee population. This is a

representative sample of just a few inches of one of our stumps.

Come to think of it, a

couple of years ago, I saw a strange-looking wasp visit this stump for

an unknown reason --- I guess I know what she was doing now!

Since our stumps are

slowly being ripped

out of the ground

and turned into hugelkultur

mounds, I guess it's

a good thing I'm making the bees replacement

homes.

As of today I'm 43 years old.

Anna made me some awesome

birthday brownies, while at the same time indulging my

recent experiment with deleting wheat. How did she do it? Coconut

flour. More on that later.

Best birthday brownies ever.

Many folks turn to coconut

flour when they decide to ditch

wheat.

Compared to white flour, coconut flour has about the same amount of

protein, but replaces nearly a third of the carbohydrates with good

fats. Coconut flour makes decadent desserts, too, if you like the

taste of coconut and don't mind a bit of denseness in the final product.

Many folks turn to coconut

flour when they decide to ditch

wheat.

Compared to white flour, coconut flour has about the same amount of

protein, but replaces nearly a third of the carbohydrates with good

fats. Coconut flour makes decadent desserts, too, if you like the

taste of coconut and don't mind a bit of denseness in the final product.

Of course, if you live

in the boondocks like we do, you're not going to find coconut flour in

the grocery store. You might find whole coconuts, though, in

which case you can try to make your own. Here's the method we

used to make our coconut flour (and why

you shouldn't follow our lead):

To

make coconut flour the right way, you'll need to first send

the flesh through an oil expeller. I've hit a bit of a wall with

our expeller, but Mark thinks he can

convert it to heating with electricity so that smoke doesn't ruin the

product. If he gets that going, I think we could make real

coconut flour by first expelling the oil, then sending the coconut cake

through the Magic Mill.

No matter how you get

it, here's a delicious recipe for coconut

flour brownies:

0.5 cups cocoa

0.5 cups cocoa- 0.5 cups coconut flour

- 0.5 cups sugar

- 1 teaspoon baking powder

- 0.5 teaspoons salt

- 2 eggs

- 4 tablespoons butter (or 8 tablespoons if you get the oil out of your flour or use storebought coconut flour)

- 1 teaspoon vanilla

- a small handful of dark chocolate chips

Mix the first seven ingredients together, sprinkle

the chocolate chips on top, and bake at 350 degrees Fahrenheit until a

knife comes out clean. Serves 4 (or 8 if you have self restraint.)

Have you experimented

with coconut flour? I'd be very curious to hear about your

technique if you've made the flour at home.

Not much left of the delicious no-wheat brownies.

Look at this ---

mushrooms in the middle of January! Not only is the

totem that fruited in November pushing out new mushrooms,

so is the totem that I inoculated with wild oyster mushroom spawn.

The oyster mushrooms in

our yard aren't currently fruiting, which makes me wonder if the woods

might be a slightly more sheltered microclimate. I've read that

even leafless limbs hold in a bit of warmth on cold winter nights, a

bit like quick

hoops do. Of

course, this area is also one of the sunniest parts of our farm, so

that might be the real reason mushrooms are able to grow there in the

dead of winter.

As a side note, the

chickens are only interested because they thought they were going to

get breakfast. Otherwise, they leave oyster mushrooms alone,

meaning that those of you with limited space can "stack" chickens and

mushrooms to your heart's content. Two harvests from one space

--- gotta love permaculture.

Yet another day when my Pro Line hip waders are worth their weight in gold.

If you keep bees, you end up

with lots of wax. Folks who like comb honey or who manage top bar hives will have much more, but

even those of you who use an extractor will collect a lot of

cappings.

If you keep bees, you end up

with lots of wax. Folks who like comb honey or who manage top bar hives will have much more, but

even those of you who use an extractor will collect a lot of

cappings.

Our movie star neighbor

solved the excess beeswax problem by making 110 candles. (He

hasn't quite figure out how to solve the excess candles problem....)

The first step was to

clean the beeswax. He melts his wax in an olive oil can partially

full of water atop a pot of boiling water, then uses a seive to dip out

any gunk that floats to the surface. (This waxy debris makes

great firestarters, our neighbor points out.) After the wax is

mostly clean, pour it into a five gallon bucket to cool, then pour off

the water once the wax has solidified. You should be able to pop

the solid wax right out of your bucket, but then will need to scrape

more gunk off the bottom until you're left with beautiful, clean wax.

Knock the wax into

chunks with a hammer and melt it again in a fresh olive oil can, still

atop a pot of boiling water. If you don't want to mess your

kitchen up, lay down some newspapers, and also set up a broom or other

pole between two chairs. Cut wick material (about $2 for more

than you'll ever use) into lengths twice as long as you want your

finished candles to be. Then start dipping.

If your wax is the

perfect temperature, it will coat the wick thickly but won't drip off

excessively. A little cooler is generally better than a little

hotter since cooler wax stays on much better --- you'll know if you've

gone too cold because the wax will be a bit chunky.

Our neighbor found it

useful to keep three cans of wax melting at all times, pouring melted

wax into the foremost can so that it was always full enough to dip a

candle.

After dunking the wick

the first time, wait until the wax is partly cool, then stretch the

candle out with your fingers so that the candle straightens. You

may need to repeat this procedure after the second dipping as well, but

after that, you can just dip, cool, and dip again.

You'll notice in the

pictures that our neighbor makes two candles out of each wick.

This method makes it easy for him to drape the candles over his rod and

let them cool between dippings. Later, he'll cut the wick and end

up with a pair of candles.

Our neighbor dipped each

candle about 25 to 30 times, which means it took him six to seven hours

(and about two gallons of clean wax) to make 80 candles plus 30 tea

lights. The tea lights were to use up excess wax at the end of

the project and are made from a small piece of wick inside a cleaned

out applesauce container.

Our neighbor dipped each

candle about 25 to 30 times, which means it took him six to seven hours

(and about two gallons of clean wax) to make 80 candles plus 30 tea

lights. The tea lights were to use up excess wax at the end of

the project and are made from a small piece of wick inside a cleaned

out applesauce container.

Previous batches of

handmade candles have gone to the Harvest

Table Restaurant,

where they were priced at $5 per pair. However, our neighbor

notes that they didn't sell nearly as well as honey (which went like

hotcakes.) On the other hand, the yellow, honey-scented candles

hanging on his wall always attract the attention of guests, so he's had

no problem giving them away to loving homes.

Cold

winter days give us an incentive to catch up on our reading, so I've

launched the February

ebook a bit early. Topics include:

Cold

winter days give us an incentive to catch up on our reading, so I've

launched the February

ebook a bit early. Topics include:

- Easy berries

- Backyard chickens

- Buying in bulk

- Informal apprenticeships

For those of you who are

new to Weekend Homesteader, this series walks you through the basics of

growing your own food, cooking the bounty, preparing for emergency

power outages, and achieving financial independence.

I hope you'll consider

splurging 99

cents to buy

a copy of my newest ebook from Amazon's

Kindle store. And many

thanks in advance if you can find the

time to write a brief review.

As usual, I'm also very

glad to email you a free pdf copy to read if you

don't have the spare cash, or just don't want to deal with downloading

an app so you can

read the ebook on your computer or phone. Just email

me with your request --- no strings attached.

As usual, I'm also very

glad to email you a free pdf copy to read if you

don't have the spare cash, or just don't want to deal with downloading

an app so you can

read the ebook on your computer or phone. Just email

me with your request --- no strings attached.

Don't forget that Weekend

Homesteader: January is

still available, with the first half of the backyard chickens primer

and with information on backup lighting, soil testing, and bread

baking. Thanks for reading!

Our 2nd Jotul wood stove can sometimes heat my small room

to the point where I need to open a window. I've been experimenting

with different ways of controlling the size of the fire with mixed

results.

The first lesson learned is

to not worry about letting the fire go out. The super draft on the

Jotul makes it really easy to start. I usually stop feeding it if my

inside temperature goes above 68.

Another trick I like to use

is putting a log in the corner so one of its sides is up against a

wall. I think it burns slower when less surface area is exposed.

I don't want you to

think that life under the quick

hoops is entirely

worry-free. The winter protection does make one garden problem

much worse --- bugs.

Some

people use row cover fabric to keep insects out. For example, you

can cover up your eggplants in the summer and prevent flea beetle

damage. Or, if you're running breeding experiments, you can

uncover different varieties of the same species on alternate days to

allow for wild pollination but not cross-pollination.

Some

people use row cover fabric to keep insects out. For example, you

can cover up your eggplants in the summer and prevent flea beetle

damage. Or, if you're running breeding experiments, you can

uncover different varieties of the same species on alternate days to

allow for wild pollination but not cross-pollination.

Unfortunately, row

covers keep out all of the beneficial insects too --- like ladybugs to

eat up the aphids that seem to grow like crazy on my winter

greens. I'm not sure what these tiny flies are or what eats them,

but I'd like some of those predators inside my quick hoops too.

I've ranted at length

about the downside

of greenhouses --- most relevantly, the fact that you have to

supply most ecosystem functions yourself rather than relying on the

earth to do the work for you. It looks like quick hoops share at

least a one of these flaws.

I've ranted at length

about the downside

of greenhouses --- most relevantly, the fact that you have to

supply most ecosystem functions yourself rather than relying on the

earth to do the work for you. It looks like quick hoops share at

least a one of these flaws.

On the upside, I'll be

moving the quick hoops in just a couple of months, so these insect

infestations will soon be a thing of the past. I can just hear

the hibernating ladybugs planning their entrance strategy.

19 degrees last night was

cold enough to freeze the non-potable water line for the 2nd time this

season.

I'm not complaining though.

Today was a perfect winter

day for being still.

Can

you get honey out of the comb without an extractor. Well, sure.

Can

you get honey out of the comb without an extractor. Well, sure.

Just cut the comb off

the frame, put it in a colander atop a bowl, and mash everything up a

bit with a potato masher (or spoon.)

Honey will slowly

trickle down into the bowl...slow being the operative word if

you start out with frozen honey from a dead

hive in January.

On the scale of our two

person family, the truth is that extracting honey using a bowl and

colander is probably the best option --- faster than cleaning the

extractor, really. Yet another reason to set my sights on top bar hives.

This small electric heater is

another element in the formula for keeping

my Jotul wood stove burning at its lowest temperature.

Knowing it will kick in when

the fire dies down lets me sleep a little easier.

It also functions as a main

heat source when the outside temperature is above freezing.

Despite

what the calendar says, I consider this the halfway point of winter.

Despite

what the calendar says, I consider this the halfway point of winter.

From a heating

perspective, January is the coldest month. That means we should

be midway through our wood supply, but we've actually used more than we

should have. It's been a warm, but sedentary, winter, and I've

burnt excess wood so I wouldn't irritate my carpal tunnel while

pounding away on the keyboard. We have plenty more out at the

parking area if the driveway ever cooperates, but for now we've only

got about 40% of the farmside wood left. Time to be a little more

sparing.

From

a food storage perspective, I'd say we're only a third of the way

through winter. Even though our Persephone

Days

will soon be over and the winter greens will start growing again, we

won't pick anything non-leafy until oyster mushrooms pop up in March,

asparagus in April, and then finally strawberries, broccoli, and more

in May. Here, we've done a much better job than with our wood

stores, in large part due to the seemingly endless supplies of lettuce

and greens from the quick hoops. Of the 28.75 gallons of winter

vegetables we stored away, we've consumed a mere 4.5 gallons.

We'd better pick up the pace!

From

a food storage perspective, I'd say we're only a third of the way

through winter. Even though our Persephone

Days

will soon be over and the winter greens will start growing again, we

won't pick anything non-leafy until oyster mushrooms pop up in March,

asparagus in April, and then finally strawberries, broccoli, and more

in May. Here, we've done a much better job than with our wood

stores, in large part due to the seemingly endless supplies of lettuce

and greens from the quick hoops. Of the 28.75 gallons of winter

vegetables we stored away, we've consumed a mere 4.5 gallons.

We'd better pick up the pace!

In the long run, an orchard

provides the most fruit per hour of

maintenance, but berries fill in the gap while you're waiting for

your apple trees to produce. Luckily, easy berry plants like

strawberries and raspberries will start producing in a year or

less. Better yet, they're so easy to propagate that you'll soon

have filled up every nook and cranny of your yard with edibles and will

be begging neighbors to take extra plants off your hands.

In the long run, an orchard

provides the most fruit per hour of

maintenance, but berries fill in the gap while you're waiting for

your apple trees to produce. Luckily, easy berry plants like

strawberries and raspberries will start producing in a year or

less. Better yet, they're so easy to propagate that you'll soon

have filled up every nook and cranny of your yard with edibles and will

be begging neighbors to take extra plants off your hands.

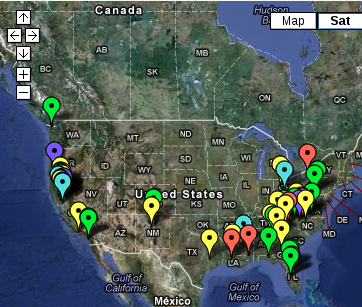

Choosing your berries

The

primary purpose of this week's exercise is to be harvesting your own

fruit in

a year or less. As a result, I'm going to focus on the quickest

bearing berries --- blackberries, raspberries, and strawberries.

Each of these plants require only minimal to moderate care, with their

differences detailed in the chart below.

| USDA

hardiness zones |

pH |

Spacing (feet) |

Notes |

|

| Blackberry |

5-10 |

5.5-7.0 |

3-10 |

Best in southern climates and

for people with lots of space |

| Raspberry, red |

3-8 |

6.0-6.8 |

1-2 |

Best in northern climates; can

fit into smaller spaces than other brambles |

| Raspberry, black |

5-8 |

6.0-6.8 | 2-3 |

A good southern berry for those

with less space, but not as productive as other brambles |

| Strawberry |

3-8 |

6.5-6.8 |

1-2 |

You can tuck a few strawberry

plants into even the smallest garden, but they take more care than the

brambles |

If you're feeling patient, you might want to select additional small fruits from the second chart below. Although you may get a grape or blueberry the first or second year, these "advanced" species all require four or five years to reach their full potential. I consider a blueberry patch a long term investment --- on par with planting a fruit tree --- while strawberries and raspberries can be snuck into the yard of a rental property.

| USDA

hardiness zones |

pH |

Spacing (feet) |

Notes |

|

| Blueberry, highbush |

3-8 |

4.5-5.5 |

6-8 |

Best in northern climates; must

have acidic soil; needs more than one variety for pollination |

| Blueberry,

rabbiteye |

7-9 | 4.5-5.5 |

6-8 |

Best in southern climates; must

have acidic soil; needs more than one variety for pollination |

| Currant |

3-6 |

6.2-6.5 |

4 |

Best in northern climates; some

states don't allow you to plant certain varieties because of the white

pine blister rust |

| Gooseberry |

3-7 |

6.2-6.5 |

4 |

Best in northern climates but

can be planted a bit further south than currants; if you live in the

south, try to find a cool microclimate |

| Grape |

3-8 |

6.0-7.5 |

8-10 |

Bunch grapes hate hot, humid

summers, so consider muscadines in the deep south |

| Kiwi |

5-8 |

5.0-6.5 |

10 |

Kiwis come in male and female

varieties --- be sure to plant at least one male for every eight

females; only hardy

kiwis can survive below zone 7 |

For the rest of this

lunchtime series, I'll be focusing on care of the

simplest berry varieties. If you decide to plant any of the more

"advanced" small fruits from the second chart, you'll need to do a bit

of extra research on pruning and trellising. But don't let that

discourage you --- all of these small fruits are well within the reach

of the backyard homesteader.

For the rest of this

lunchtime series, I'll be focusing on care of the

simplest berry varieties. If you decide to plant any of the more

"advanced" small fruits from the second chart, you'll need to do a bit

of extra research on pruning and trellising. But don't let that

discourage you --- all of these small fruits are well within the reach

of the backyard homesteader.This week's lunchtime series is exerpted from Weekend Homesteader: February, which is available for 99 cents from Amazon's kindle store. The ebook also includes a primer on choosing and caring for a backyard flock of chickens, information on buying in bulk, and tips for creating your own apprenticeship. If you enjoy the book, please consider leaving me a review.

| This post is part of our Easy Berries lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Our dog Lucy works overtime

to keep predators away from the perimeter.

Sometimes she gets a little

too aggressive when it comes to small critters and runs them all the

way into the ground.

We briefly considered

building some sort of barrier around each bed, but the damage is rare

and usually easy to fix.

You wouldn't know it for

the huge amount of garlic

I grow every year,

but I used to hate garlic. What won me over to the anti-vampire

side of the cooking fence was roasted garlic. When you cook whole

cloves without breaking them apart, the result is sweet and mildly

garlicky, without the bite of minced garlic.

In recent years, I've

learned to love the bite, but I'm working on a roasted garlic hummus

recipe, so I figured I'd learn to roast garlic the right way.

It's surprisingly easy. Clean a dozen or so heads of garlic

(assuming your skins are still a bit dirty from the garden, like  mine),

then chop off the tops so that the tips of most cloves are barely

exposed. Drizzle a bit of olive oil on the exposed skin and bake

in a 350 degree oven for about an hour. Once you can handle the

heads again, squeeze out the roasted cloves.

mine),

then chop off the tops so that the tips of most cloves are barely

exposed. Drizzle a bit of olive oil on the exposed skin and bake

in a 350 degree oven for about an hour. Once you can handle the

heads again, squeeze out the roasted cloves.

You'll have much better

luck roasting softneck garlic than hardneck for the simple reason that

it's tough to cut the top off the latter. And why waste those

easy to skin, huge cloves on this recipe when trouble heads with two

dozen tiny cloves are so easy to roast? You can squeeze the guts

out of a head of garlic in seconds, no matter how many cloves are

present.

Use your roasted garlic

in any recipe that calls for regular garlic, but add a lot more of

it. (About a head of roasted garlic will replace a clove of raw

garlic.) Enjoy!

Be forewarned --- once

you taste a homegrown strawberry, you'll never

be able to eat another berry from the grocery store. Even ripe

fruits plucked fresh from a you-pick operation don't hold a candle to

the explosion of flavor inside a strawberry grown in the humus-rich,

no-till garden. Luckily, strawberries are pretty simple to grow

in your backyard, so you'll be able to feed your new addiction.

Your first step when planting

strawberries is variety selection.

Although everbearing strawberries look good on paper, I find

June bearers to be less work with higher returns, so I recommend the

beginning homesteader start there. Even if you stick with

June bearers, you can count on a full month of strawberries if you

plant early, midseason, and late varieties (and be aware that

"June bearers" actually fruit in April and May in the south and middle

of the country --- the name simply refers to the single annual

crop.) Your extension

service is the best source for

recommendations of varieties that do well in your area.

Strawberries can be planted in the early spring or in the fall. I

tend to plant in the fall when expanding my own strawberry patch but in

the spring when buying in fresh plants --- that way, I don't lose my

expensive new stock to drought.

You'll get the most value for

your money if you buy bare-rooted strawberries in sets of 25 from an

online nursery. The strawberries will come with few or no leaves

and will look

quite dead, but when planted with the roots spread out just below the

soil surface and the growing crown peeking up slightly above the

ground,

new leaves will soon appear.

You'll get the most value for

your money if you buy bare-rooted strawberries in sets of 25 from an

online nursery. The strawberries will come with few or no leaves

and will look

quite dead, but when planted with the roots spread out just below the

soil surface and the growing crown peeking up slightly above the

ground,

new leaves will soon appear.

There are several different methods of growing strawberries, and your

initial plant spacing will depend on which technique you plan to

follow. I put in a bit more work to get tastier fruits, spacing

my plants 12 inches apart and removing all of the runners --- this is

called the hill system. If you're more of a laissez faire

gardener, you might prefer the matted row system, in which plants are

spaced much further apart and allowed to fill up the gaps with

runners. The benefit of the matted row system is that it's less

work in year one and you don't have to buy as many plants; the downside

is that you'll spend more time next year picking lots of small fruits

that often aren't quite as tasty as the fewer big fruits you get from

the hill system.

No matter which spacing method you choose, be aware that strawberries

can handle a little bit more shade then most vegetables but will give

you the sweetest fruits in full sun. Strawberries can also become

quickly overwhelmed by weeds, so mulch them

carefully and repeatedly and hand weed as necessary. If you're

planting into weedy ground, you might choose to lay down a kill mulch

(see Weekend

Homesteader: May) and plant your strawberries into small

holes cut in the cardboard.

No matter which spacing method you choose, be aware that strawberries

can handle a little bit more shade then most vegetables but will give

you the sweetest fruits in full sun. Strawberries can also become

quickly overwhelmed by weeds, so mulch them

carefully and repeatedly and hand weed as necessary. If you're

planting into weedy ground, you might choose to lay down a kill mulch

(see Weekend

Homesteader: May) and plant your strawberries into small

holes cut in the cardboard.

This

week's lunchtime series is exerpted from Weekend

Homesteader: February,

which is available for 99 cents from Amazon's kindle store. The

ebook

also includes a primer on choosing and caring for a backyard flock of

chickens, information on buying in bulk, and tips for creating your own

apprenticeship. If you enjoy the book, please consider leaving me

a

review.

| This post is part of our Easy Berries lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

One question that's been on

the back of our minds lately is if we have

enough fire wood to get us through the rest of the cold season.

This walnut tree we cut down

not far from the trailer a couple of years ago seemed to be calling out

to me today saying "ahem......you're forgetting about me!"

I guess it's a case of not

seeing the tree for the forest. I've walked past it almost everyday

without giving it a second thought.

There

are two small difficulties with extracting

your honey by hand.

The first occurred to me as I left the honey dripping into a bowl

overnight --- in the summer, that bowl would attract ants like

crazy. (Of course, in the summer, it probably wouldn't take all

night for the honey to settle out of the wax.)

There

are two small difficulties with extracting

your honey by hand.

The first occurred to me as I left the honey dripping into a bowl

overnight --- in the summer, that bowl would attract ants like

crazy. (Of course, in the summer, it probably wouldn't take all

night for the honey to settle out of the wax.)

The other slight problem

is that you get a few wax particles in your honey. There are

several ways to deal with this --- you can strain the honey through a

finer sieve or cloth, or you can wait until the wax floats to the top

of the jar and just skim it off. Or you can do what I do and just

savor the honey, wax and all --- the tiny specks aren't really

noticeable.

Care of your first year plants

Your new plants will try to

bloom their first spring. For

best

results, carefully pick every flower off the plants so they'll put

their energy into growing healthy roots and leaves instead. Yes,

that means you won't get to taste your first berry until next year

--- it will be worth the wait. Using my growing system, this

first year is the only time you'll have to pick off flower buds since

you'll plant new strawberries in the fall from here on out. (Fall

planted berries have generally established themselves enough that you

can let them fruit their first spring.)

Your new plants will try to

bloom their first spring. For

best

results, carefully pick every flower off the plants so they'll put

their energy into growing healthy roots and leaves instead. Yes,

that means you won't get to taste your first berry until next year

--- it will be worth the wait. Using my growing system, this

first year is the only time you'll have to pick off flower buds since

you'll plant new strawberries in the fall from here on out. (Fall

planted berries have generally established themselves enough that you

can let them fruit their first spring.)

After trying to bloom,

the strawberry plants will send out lots of

runners. Those of you following the hill system will want to snip

back runners during your usual weeding sessions. You don't need

any fancy equipment as long as you catch the runners when they're young

and tender --- just pinch them off between your thumb and forefinger.

Strawberry plants often

keep green leaves through most or all of the

winter, but you'll want to put some mulch over top of the plants once

the rest of your garden has died back. Freezing and thawing can

otherwise push your berries' shallow roots up out of the ground and

kill the plants. Be sure to rake the mulch back from the tender

new

leaves in early spring and topdress the bed with a healthy coating of

compost, topped off with the old mulch plus a new layer of straw.

Flowering and fruiting

After patiently waiting 12

months, you're ready for your strawberry

harvest. This time, leave all of the blooms and keep an eye on

the weather. Late spring freezes can damage strawberry flowers,

so I toss row cover fabric over top of the plants if lows are expected

to drop below 30 degrees once flower buds have opened. You'll

know your flowers were damaged if the centers change from yellow to

black. All is not lost, though --- strawberry flowers tend to

open

a few at a time over the course of a week or two, so losing the

earliest flowers will just allow the plant to put more energy into

later fruits.

After patiently waiting 12

months, you're ready for your strawberry

harvest. This time, leave all of the blooms and keep an eye on

the weather. Late spring freezes can damage strawberry flowers,

so I toss row cover fabric over top of the plants if lows are expected

to drop below 30 degrees once flower buds have opened. You'll

know your flowers were damaged if the centers change from yellow to

black. All is not lost, though --- strawberry flowers tend to

open

a few at a time over the course of a week or two, so losing the

earliest flowers will just allow the plant to put more energy into

later fruits.

While watering is important

throughout the growing season, the time

between fruiting and harvest is a critical period. Strawberries

need an inch of water per week, and if the weather isn't cooperating,

you have to irrigate. Otherwise, just watch and wait, picking

your strawberries when they are bright red on the outside and at least

slightly red clear through. You'll need to set aside time to

harvest strawberries at least every other day, but daily harvesting is

better. Berries are sweetest in the afternoon and are least tasty

if picked right after a rain (or watering session.)

While watering is important

throughout the growing season, the time

between fruiting and harvest is a critical period. Strawberries

need an inch of water per week, and if the weather isn't cooperating,

you have to irrigate. Otherwise, just watch and wait, picking

your strawberries when they are bright red on the outside and at least

slightly red clear through. You'll need to set aside time to

harvest strawberries at least every other day, but daily harvesting is

better. Berries are sweetest in the afternoon and are least tasty

if picked right after a rain (or watering session.)

If you ever get sick of

grazing on fresh strawberries, Weekend

Homesteader: August tells how to make peach leather, a recipe that

can

be easily tweaked to produce the most delicious strawberry leather

you've

ever tasted. Or check out recipes for strawberry

freezer jam and chocolate

strawberry shortcake.

Renovating and expanding the strawberries

After gorging on

strawberries in May or June, it's time to start

plucking runners again. This year, you don't need to be quite as

careful about removing every single runner because you'll want to

expand your patch. By the middle of summer, missed runners will

have rooted and turned into new strawberry plants. When the

weather forecast promises three or more rainy days in a row, head out

into the garden with your trowel and carefully dig up all of these baby

strawberry plants, then start a second patch in a new garden bed.

This is another time when irrigation is critical since summer-planted

strawberries can easily wither up and die before they get their feet

under them.

After gorging on

strawberries in May or June, it's time to start

plucking runners again. This year, you don't need to be quite as

careful about removing every single runner because you'll want to

expand your patch. By the middle of summer, missed runners will

have rooted and turned into new strawberry plants. When the

weather forecast promises three or more rainy days in a row, head out

into the garden with your trowel and carefully dig up all of these baby

strawberry plants, then start a second patch in a new garden bed.

This is another time when irrigation is critical since summer-planted

strawberries can easily wither up and die before they get their feet

under them.

If you use my method of

expanding the patch in the late summer, you can

skip this step, but otherwise you'll need to renovate your bed in the

fall. Many sources recommend mowing off the strawberry leaves,

but I find that step unnecessary. Instead, I simply rip out

plants that have gotten too close together, leaving at least one foot

of mulched soil between each plant.

I've found that flavor

and vigor begin to diminish after a strawberry

patch has fruited once, twice, or three times. (How many seasons

you can eke out of the plants depends on the quality of your

soil.) I

generally eat two years' worth of strawberries from a bed, then rip the

plants out and rotate the bed back into the general vegetable

garden. As long as I transplanted runners the previous year, I'll

have a fresh bed ready to produce more berries the following

spring.

I've found that flavor

and vigor begin to diminish after a strawberry

patch has fruited once, twice, or three times. (How many seasons

you can eke out of the plants depends on the quality of your

soil.) I

generally eat two years' worth of strawberries from a bed, then rip the

plants out and rotate the bed back into the general vegetable

garden. As long as I transplanted runners the previous year, I'll

have a fresh bed ready to produce more berries the following

spring.

This

week's lunchtime series is exerpted from Weekend

Homesteader: February,

which is available for 99 cents from Amazon's kindle store. The

ebook

also includes a primer on choosing and caring for a backyard flock of

chickens, information on buying in bulk, and tips for creating your own

apprenticeship. If you enjoy the book, please consider leaving me

a

review.

| This post is part of our Easy Berries lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We had a lost dog show up in

our barn this morning...again.

The last time this happened

was with a nice pit bull back before we had a phone. We posted a

picture in the post office with our not so easy to find address. A guy

showed up a few days later looking for his Dixie. She was a cutie.

I'm guessing this dog is

someone's hunting helper. He had a collar with what I assume is his

owner's name and phone number, but the number was disconnected.

Lucy seems to be taking it in

stride. We sometimes worry about her social skills around other dogs.

She works hard at keeping a small pack of wild dogs that roam our woods

from getting too close, but clearly this guy is different. If I didn't

know any better I'd think Lucy might be a little sweet on him.

Despite playing hookie

part of the day yesterday to nurse the stray dog back to health, I still

managed to finish the second draft of Weekend

Homesteader. A

red letter day!

There's still plenty of work

to be done before I can wash my hands of the project. But I sent

the draft off to two dutiful readers. While they babysit...ahem,

edit...the manuscript, I can take a few days "off" to reenter the real

world.

There's still plenty of work

to be done before I can wash my hands of the project. But I sent

the draft off to two dutiful readers. While they babysit...ahem,

edit...the manuscript, I can take a few days "off" to reenter the real

world.

I don't want to get too

excited about the farm since I'll be back in book mode for at least

another week once I get the editorial suggestions. But maybe we

can play with firewood? Weed a few fruit trees? I can't

wait!

There

are only two potentially complicated parts of growing blackberries and

raspberries --- variety selection and pruning. Otherwise, care is

simply a matter of annual fertilizing, mulching, and (most important)

eating all those fruits.

There

are only two potentially complicated parts of growing blackberries and

raspberries --- variety selection and pruning. Otherwise, care is

simply a matter of annual fertilizing, mulching, and (most important)

eating all those fruits.

Choosing your brambles

As I mentioned

previously, blackberries and black raspberries do better

in the south while red raspberries like areas with cooler

summers. Over large parts of the United States, you can easily

grow all three types of brambles, but your life will be a bit easier if

you begin your experiment with ones that are well suited to your

climate.

Once you decide which

type of brambles you want to grow, your next step

is to settle on which additional characteristics you're looking

for.

Thornless blackberries are easier to work with, but I've noticed

they don't seem to be as cold hardy as the thorny varieties, so

northerners should bear with thorns.

Among raspberries, you'll need to decide whether you're interested in a

spring or everbearing variety --- unlike with strawberries, I have had

very good luck with everbearing raspberries and recommend them highly.

Bramble plants tend to

be more expensive than strawberries, often

costing several dollars apiece, but you don't need to start with

many. In my garden, one everbearing raspberry plant became a

clump large enough to provide lots of fruit that fall, and by the next

spring I was able to transplant yet more new raspberries to fill up a