archives for 12/2011

I'm monitoring my quick

hoops carefully this

fall to see their limitations. So far, lettuce with no protection

has turned into a slimy mess and tokyo bekana that's not under cover  has been moderately

nipped. (Not so much that the chickens

don't think it's a treat, though.)

has been moderately

nipped. (Not so much that the chickens

don't think it's a treat, though.)

Meanwhile, under the

hoops, lettuce and all types of leafy greens are still going

strong. The Persephone

Days are here, so my

winter crops aren't actively growing, but I planted so many that I'll

still have plenty to harvest for weeks yet as long as the quick hoops

mitigate the cold.

Broccoli, however, is a

goner even under the row cover fabric. I picked the last head

yesterday and had to cut off about half the florets due to freeze

damage. My guess is that broccoli needs more protection than a

quick hoop when the outside temperatures get down into the

twenties. Still, it's hard to complain when I can make a whole

stir fry (minus the spices and rice) straight out of the garden on the

last day of November.

It got well below freezing

last night without affecting either water line.

That's big news for us and

might indicate an end to breaking a

hole in the top layer of ice on the storage tank when we need water on cold days.

The insulated box that goes

from the ground to the trailer has a small door so we can access the

water hose spigot when needed.

I'm sometimes surprised by

how bountiful the uncultivated portions of our farm are. Thursday

morning, I startled thirty wild turkeys who were hunting for bugs in

our woods. Then, while helping Mark split firewood, I looked up

and saw this box-elder chock full of wild oyster mushrooms. Taken

together, the turkeys and mushrooms would have made a bountiful

meal...if I'd had a gun with me on my walk and if the mushrooms weren't

fifteen feet up in the air.

I'm sometimes surprised by

how bountiful the uncultivated portions of our farm are. Thursday

morning, I startled thirty wild turkeys who were hunting for bugs in

our woods. Then, while helping Mark split firewood, I looked up

and saw this box-elder chock full of wild oyster mushrooms. Taken

together, the turkeys and mushrooms would have made a bountiful

meal...if I'd had a gun with me on my walk and if the mushrooms weren't

fifteen feet up in the air.

Luckily, we can recreate

that bounty in a more easily harvestable fashion. I thawed a

homegrown chicken out of the freezer and plucked yet another flush of

shiitakes off our mushrom

raft.

Permaculture gives us the best of both worlds --- high quality meat fed

partially from wild insects plus micronutrient-rich mushrooms grown on

woods-harvested logs, all right at my fingertips.

Once you've chosen your

emergency winter wardrobe, I recommend you

spend the majority of the cash you've set aside for this project

on a good sleeping bag. If you snuggle down inside a sleeping bag

rated at 0 degrees Fahrenheit in all of the clothes mentioned above

(minus the boots), you'll be warm as toast no matter what happens.

Once you've chosen your

emergency winter wardrobe, I recommend you

spend the majority of the cash you've set aside for this project

on a good sleeping bag. If you snuggle down inside a sleeping bag

rated at 0 degrees Fahrenheit in all of the clothes mentioned above

(minus the boots), you'll be warm as toast no matter what happens.

When choosing sleeping

bags for power outages, you don't need to buy

the expensive, light-weight versions meant for backpacking. And

as long as you keep your bag dry, the insulating material doesn't

matter. Instead, make your choice based on two characteristics

--- temperature rating and style.

Sleeping bag temperature

ratings should be taken with a grain of salt since a 0

degree bag probably won't make you very happy in a tent on a windy

mountaintop at 0 Fahrenheit. That said, lower ratings do mean

warmer

bags, so go as low as your wallet will allow.

There are two main types

of sleeping bag styles --- mummy bags and

rectangular bags. Mummy bags are the warmest for one person

sleeping alone since they follow the contour of your body when zipped

up (and usually even include a hood to keep your head warm.) But

don't buy a mummy bag if you can't sleep in a confined situation ---- a

zipped up rectangular bag will be warmer than an unzipped mummy

bag. In addition, make sure you choose a bag that's big enough if

you're especially tall or wide.

If you regularly sleep

with someone, you might want to choose a right

and left handed pair of sleeping bags. These bags can be used

separately or can be zipped together to make a family-sized warm spot.

If you regularly sleep

with someone, you might want to choose a right

and left handed pair of sleeping bags. These bags can be used

separately or can be zipped together to make a family-sized warm spot.

Don't just toss your

sleeping bags into the closet while waiting for a

power outage. Rectangular bags can often be unzipped so they lie

all the way flat and work as an extra comforter on your bed, allowing

you to turn down the heat at night. I enjoy slipping my mummy bag

inside the sheets to give me something to snuggle into when I first get

into my cold bed at night --- a sleeping bag heats up much faster than

a traditional bed.

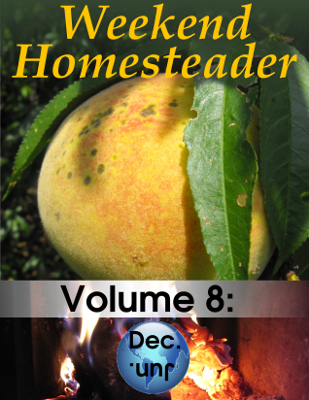

I

hope you enjoy this excerpt from Weekend

Homesteader: December.

The 99 cent ebook walks you through the basics of planting your first

fruit trees,

staying warm without electricity, understanding the uses of essential

tools, and turning trash into treasures. If you're interested in

other aspects of basic emergency preparedness, Weekend

Homesteader: November gives tips on storing drinking water and the

upcoming Weekend Homesteader: January will cover backup lighting

options.

| This post is part of our Emergency Warmth lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

One

of the best things you can do to stay warm is to move around.

This will also raise your spirits during an extended power

outage. I've found that if I get up the courage to jump out of my

toasty sleeping bag and into the cold air long enough to get fully

dressed and give the dog a walk first thing in the morning, my blood

has started pumping enough to keep me warm for an hour or more.

Of course, if you have a wood stove, splitting wood is a time-proven

method of warming you twice.

One

of the best things you can do to stay warm is to move around.

This will also raise your spirits during an extended power

outage. I've found that if I get up the courage to jump out of my

toasty sleeping bag and into the cold air long enough to get fully

dressed and give the dog a walk first thing in the morning, my blood

has started pumping enough to keep me warm for an hour or more.

Of course, if you have a wood stove, splitting wood is a time-proven

method of warming you twice.

If you're a little less

hard-core, warm foods and drinks will also wake

your body and improve your mood. It's easy to heat a pot of

water on top of a wood stove to make tea or cocoa, and then you can

make a pot of

soup for lunch. You can even pull coals out of the stove to cook

on top of, as I did during a ten day power outage in 2009 when we had

only an exterior wood furnace to keep us warm. A propane camp

stove will do the job even better. No matter how you heat up your

food and drinks, be very careful since synthetic fabrics are extremely

flammable.

Finally, know the

symptoms of hypothermia and keep an eye on young

children or elderly family members who might not be self-aware enough

to realize they're too cold. Early symptoms include constant

shivering; pale or blue lips, ears, fingers, and toes; clumsiness;

slurred speech; stumbling; trouble thinking; and poor

decision-making. You should be very concerned if you or someone

in your family experiences blue and puffy skin; inability to walk;

incoherent behavior; stupor; a weak pulse; and slow, shallow

breathing. Don't risk it if you're experiencing even mild

hypothermia --- find a way to get warm and dry immediately.

Beyond the basics

After dealing with one too many winter power

outages, we saved our

pennies to buy and install an efficient wood stove. I estimate

the stove will pay for itself in lower heating costs within three or

four years, we cook soup and beans on the stove even when the power's

on, and the cats and I love basking in the radiant heat and watching

the flames flicker inside. You can read more about our choices by

following these links:

After dealing with one too many winter power

outages, we saved our

pennies to buy and install an efficient wood stove. I estimate

the stove will pay for itself in lower heating costs within three or

four years, we cook soup and beans on the stove even when the power's

on, and the cats and I love basking in the radiant heat and watching

the flames flicker inside. You can read more about our choices by

following these links:

I

hope you enjoyed this excerpt from Weekend

Homesteader: December.

The 99 cent ebook walks you through the basics of planting your first

fruit trees,

staying warm without electricity, understanding the uses of essential

tools, and turning trash into treasures. If you're interested in

other aspects of basic emergency preparedness, Weekend

Homesteader: November gives tips on storing drinking water and the

upcoming Weekend Homesteader: January will cover backup lighting

options.

This post is part of our Emergency Warmth lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: This post is part of our Emergency Warmth lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

It finally dried up enough

yesterday for me to put a new coat of high

temperature caulking on the first Jotul

woodstove chimney.

I checked it today and it

seems like a solid seal.

The real test will be the

next time it rains.

The journalists

who fell in the alligator swamp a year and a half ago

recently posted a video of our farm on youtube. It makes me a

cringe a bit, partly because they got Mark's last name wrong, partly

because of all the messy bits I didn't clean up (I didn't think they

were coming in the house...), but mostly because it's just painful to

listen to myself talk. What I do find interesting, though, is to

see how much the garden has changed in just a few months. I keep

meaning to post a video tour of the farm and not getting around to it,

so maybe this will suffice for now.

Edited to add: Mark's name is now right --- thanks, Mimi!

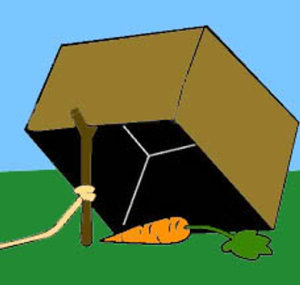

Racoons are cute, but they're

also one of the top predators to worry about if you have chickens.

Dragonflypower.com

has a system where he traps and cooks them. His suggestion for those

who are not enthusiastic about raccoon stew is to trap the biggest one

and take him to the vet to be fixed. Once he realizes your coop is

secure he'll stop trying and keep other racoons out of his territory.

Otherwise you end up with a fresh new crop of racoons each year who

will want to have a try at your delicious chickens.

We've never had a problem

with racoons thanks to Lucy's vigilante patrols.

Image credit goes to

Alaska-in-pictures.com.

Our first foray into buying in bulk was only approximately 50%

successful. We saved a bundle on bulk cocoa and had no trouble

using it up in good time, but the flours were more problematic.

Whole wheat flour (and other processed whole grains, like brown rice)

are only good for six months, or considerably less if you live in a

hot, humid climate like ours. If you save 10% on the flour but

have to give 25% of it to the chickens, that's a net loss.

Our first foray into buying in bulk was only approximately 50%

successful. We saved a bundle on bulk cocoa and had no trouble

using it up in good time, but the flours were more problematic.

Whole wheat flour (and other processed whole grains, like brown rice)

are only good for six months, or considerably less if you live in a

hot, humid climate like ours. If you save 10% on the flour but

have to give 25% of it to the chickens, that's a net loss.

I'm currently

considering going a bit higher tech, buying wheat in its unprocessed

form and a grain grinder. (We do have a hand grinder, but I know

that I wouldn't grind much wheat if it was my only option. It's

terrible on my wrists.) The good thing about this option is that

you end up with much higher quality flour since grains start to degrade

as soon as they're ground. In addition, untouched hard grains

(like wheat and corn) can easily last a decade, and I'm pretty sure we

could manage to go through 45 pounds in that time period. (Soft

grains, such as barley and oats will last at least six years.)

I suspect that many of

you have already tried this out, and I'd love to hear your

experiences. Here are my primary questions, but feel free to

ramble on about other things that are moderately relevant:

- What kind of grain grinder do you use? The Nutrimill and Whispermill have very good ratings, but both are micronizers, which means they basically explode the grain rather than grind it. That has implications for bread-baking, and would also mean that all of our flour would be whole grain. I want to be able to sift out the bran --- I know that whole wheat is better for you, but we've cut back our grain usage so drastically that it's more of a dessert, and I follow the French guidelines of eating the tastiest food in extreme moderation. Which is a long way of saying that I'm considering the more expensive mills that grind grains on stones, such as the Komo Fidibus. What do you think?

- Where do you get your bulk grains? Once you add on shipping, all of the online options are exorbitant. I was shocked to see that Sam's Club sells wheat in plastic bucket for about 45 cents per pound, which is the best price I've seen short of the feed store. Speaking of the feed store --- I know that Dolly Freed in Possum Living got her family's grain from the feed store, but I'm just not sure. I'd like to know whether I'm getting hard wheat or soft wheat, and if I do end up buying one of the micronizers, I've read that a single stone can tear up your machine. Ideas?

- Where and how do you store your

grains?

Chicken keeping doesn't get

much easier than free

range chickens with an automatic

heated chicken waterer.

Toss four cups of food to the seven hens and a rooster in the morning,

collect four eggs that night. The flock does all the work.

Some

of my experiments fade away while others stand the test of time and

become part of our daily routine. Biochar falls into the latter

category.

Some

of my experiments fade away while others stand the test of time and

become part of our daily routine. Biochar falls into the latter

category.

We haven't gotten around

to making large amounts of biochar, but it's simple to sift

charcoal out of the ashes from our wood stove whenever the ash bucket

fills up (once or twice a month.) Come spring, I'll soak

the charcoal in urine to give it a dose of nitrogen, then add it to my soil.

This past growing

season, I discovered that biochar

gave early spring onion seedlings a leg up, probably due to absorbing

sunlight and heating the soil. The real benefits of biochar,

though, will show up later when microorganisms move into their "condos."

For more information on

biochar, check out some of my previous posts. First, videos from

the experts:

Next, my research and

experiments with bringing biochar to the backyard:

- Backyard biochar resources

- Biochar chemistry and biology

- Do I need to crush biochar?

- How to activate biochar

- How to apply biochar to your garden

I'm always looking for

the permaculture low hanging fruit, and I'd put my biochar system on

that list. If you heat with wood, don't toss those hunks of

charcoal! Put them to work in your garden.

What

do you do if you want to grow as much of your own food as possible but

you love oranges? If you live in the Deep South, of course, you

can plant oranges, lemons, and grapefruits in your yard and laugh at us

northerners. Even in zone 8, citrus grafted onto particularly

cold hardy rootstocks (usually trifoliate orange) can survive outdoors

with a little care. Here in zone 6, though, our only outdoors

choice is to plant trifoliate orange with nothing grafted onto it, and the

fruits just aren't worth it.

What

do you do if you want to grow as much of your own food as possible but

you love oranges? If you live in the Deep South, of course, you

can plant oranges, lemons, and grapefruits in your yard and laugh at us

northerners. Even in zone 8, citrus grafted onto particularly

cold hardy rootstocks (usually trifoliate orange) can survive outdoors

with a little care. Here in zone 6, though, our only outdoors

choice is to plant trifoliate orange with nothing grafted onto it, and the

fruits just aren't worth it.

Luckily, there is

another way to grow your own citrus even in cold

climates --- dwarf trees in pots that live inside over the

winter. Dwarf citrus trees stay just small enough that you can

manhandle them inside for the winter, then you enjoy their color,

scent, and fruits in a sunny window until spring. The trees

are naturally somewhat cold hardy, so you don't end up losing

your plants when you leave the door open for an hour on a winter day

the way we did with our dwarf

bananas.

The rest of this week's

lunchtime series will explain the biology and

care of dwarf citrus trees. Be careful, though --- once you read

about them, you'll want your own. And it's hard to stop with just

one.

| This post is part of our Dwarf Citrus lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The downside to ratchet

strapping bales of straw to a car roof is the access issue.

Securing the straps with the

door frame holds both doors closed and requires climbing in and out

through the window.

Last year, I was so excited

to have homegrown

tomatoes left at Thanksgiving. This year, I gave the

last of the house-ripened tomatoes to the chickens.

Last year, I was so excited

to have homegrown

tomatoes left at Thanksgiving. This year, I gave the

last of the house-ripened tomatoes to the chickens.

The truth is that even

the best heirloom tomatoes taste an awful lot like storebought if

they're picked green in October before the first frost and ripened

inside. It may sound crazy, but we'd rather eat delicious

lettuce, leafy greens, and carrots at this time of year than a less

than perfect tomato.

In fact, we're hardly

even eating out of the freezer yet. Even summer soup, frozen at

its peak of perfection, doesn't hold a candle to the sweetness of

November kale. Maybe I'll replace my dream of a Thanksgiving

tomato with a New Year's salad?

Nearly all dwarf trees get

their size from the rootstock. For citrus trees, that's usually a

flying dragon trifoliate

orange, which stunts

the resulting tree down to around 10 to 12 feet tall.

Nearly all dwarf trees get

their size from the rootstock. For citrus trees, that's usually a

flying dragon trifoliate

orange, which stunts

the resulting tree down to around 10 to 12 feet tall.

You can use the bonsai

effect --- a small pot and occasional pruning --- to miniaturize your

tree further, down to about

4 to 5 feet.

Generally, if you want your dwarf tree to grow larger, you'll pot it up

into a 25% larger container annually. If you're happy with the

size of your dwarf tree, wait until the tree has finished ripening up

all of its fruits, then tip it out of the pot, cut off about an inch or

two around the outside of the rootball, add some fresh soil to the pot,

and put your tree back in. At the same time, cut back about a

third of the tree's branches so the top growth roughly matches the

root growth.

The

scionwood (what you graft onto the rootstock) decides what kind

of

fruit you get. That's why you get huge lemons from a dwarf Meyer

lemon tree that's only two feet tall --- it's the variety, not the size

of the tree, that determines fruit size. Since some citrus

varieties

do better grafted on dwarfing rootstock than others, there's not the

same

range of fruit types available as dwarfs, but you can often find dwarf

lemons, limes, oranges, tangerines, and grapefruits. In some

cases, the fruits are the same size as the ones you'd find in the

grocery store, in come cases they're larger, and in some cases they're

smaller --- it all depends on the variety.

The

scionwood (what you graft onto the rootstock) decides what kind

of

fruit you get. That's why you get huge lemons from a dwarf Meyer

lemon tree that's only two feet tall --- it's the variety, not the size

of the tree, that determines fruit size. Since some citrus

varieties

do better grafted on dwarfing rootstock than others, there's not the

same

range of fruit types available as dwarfs, but you can often find dwarf

lemons, limes, oranges, tangerines, and grapefruits. In some

cases, the fruits are the same size as the ones you'd find in the

grocery store, in come cases they're larger, and in some cases they're

smaller --- it all depends on the variety.

Which brings me to the

final question I often get about dwarf citrus

--- can you grow one from seed? You can probably answer that

question yourself from the data I've already given you. Remember,

the rootstock determines how big the tree is and the scionwood is

responsible for the fruits. So, if I plant a seed from my dwarf

Meyer lemon tree, the offspring is only going to get its DNA from the

scionwood and will turn into a full-size Meyer lemon tree.

| This post is part of our Dwarf Citrus lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

It took a few years of

tightening and loosening these hose clamps with a flat head screwdriver

before I realized a socket attached to a ratchet driver is the easy way

to get the job done.

The flat head, sometimes

called slotted, often gets distracted and wants to slip off at the

worst possible moment.

Remember how I wrote

about sampling some Autumn

Olive fruits a

couple of months ago? I liked the flavor initially, but not the

aftertaste. So I wasn't too keen on trying my movie star

neighbor's Autumn Olive fruit leather. Boy was I wrong! The

beautiful leather was sweet, tart, and delicious, with no strange

aftertaste at all.

My neighbor's recipe is

almost too simple to post about. He just sent the fruits through

a foley mill to remove the seeds and mash them up, then dried them in

his dehydrator. No added lemon juice or sweetener of any

sort. I'm only guessing, but I suspect the aftertaste I  didn't like was in the seeds,

which is why the leather was pure ambrosia.

didn't like was in the seeds,

which is why the leather was pure ambrosia.

As a side note, our

neighbor loves his American Harvest dehydrator. It's round like

those cheap ones that do nothing, but has heating elements at the top

and a fan to force air through the trays. If you don't want to

spring for the top of the line Excalibur

dehydrator we chose,

this might be a good second best.

If

you kill your spiderplants, you probably won't want to buy a dwarf

citrus tree. Potted citrus plants are going to produce quite a

bit of food for you, so they require a proportionate amount of care.

If

you kill your spiderplants, you probably won't want to buy a dwarf

citrus tree. Potted citrus plants are going to produce quite a

bit of food for you, so they require a proportionate amount of care.

Light

In a perfect world, your

citrus tree would like to have full sun.

Most growers move their plants outside into a sunny spot for the

summer, but in the winter you'll need either a south-facing window or a

grow light to keep your tree happy. Although I've read that Meyer

lemons

want 8 to 14 hours of direct sun per day, our tree fruits quite

well for us even though it probably only gets about 6 hours of real sun

in the dead of winter. But don't think you're going to be able to

grow a dwarf citrus tree in a shady living room --- allot sixteen

square feet in your sunniest window.

Pots and soil

I

like to start young dwarf citrus trees in pots like the one shown

here. The wide, bowl-shape is perfect since dwarf citrus produce

very

shallow roots and just ignore the soil in the bottom of deeper

pots. Once the tree needs more space, I'll pot it up into

a 10 gallon pot, which is about as big as Mark and I like to go.

You'll get a beautiful tree and scads of fruits if you pot your

tree up yet again into a 15 gallon pot, but it's dicey maneuvering such

a huge plant inside for the winter.

I

like to start young dwarf citrus trees in pots like the one shown

here. The wide, bowl-shape is perfect since dwarf citrus produce

very

shallow roots and just ignore the soil in the bottom of deeper

pots. Once the tree needs more space, I'll pot it up into

a 10 gallon pot, which is about as big as Mark and I like to go.

You'll get a beautiful tree and scads of fruits if you pot your

tree up yet again into a 15 gallon pot, but it's dicey maneuvering such

a huge plant inside for the winter.

If you're going to buy

soil, there are special citrus blends

available. I like to make my own potting soil from a mixture of

stump

dirt, worm

castings, and

composted horse manure. No matter what

you do, don't dig up dirt out of your yard, put it in a pot, and expect

your citrus tree to thrive. In such a confined space, you need

light, fluffy soil with a great cation

exchange capacity,

which

generally means lots of organic matter (or vermiculite.)

Feeding and watering

Once

your dwarf citrus trees get old enough to fruit (often in the

first or second year), they are hungry eaters. My neighbor gets

awesome results with storebought chemical liquid citrus

fertilizer. I don't like to buy things, so I get nearly as good

results by feeding my tree with watered

down urine, compost

tea, or

worm tea (depending on what I have on hand at the time.)

For best results, feed your tree once a week in lieu of watering it.

Once

your dwarf citrus trees get old enough to fruit (often in the

first or second year), they are hungry eaters. My neighbor gets

awesome results with storebought chemical liquid citrus

fertilizer. I don't like to buy things, so I get nearly as good

results by feeding my tree with watered

down urine, compost

tea, or

worm tea (depending on what I have on hand at the time.)

For best results, feed your tree once a week in lieu of watering it.

Speaking of watering,

citrus trees are like most house plants --- they

hate getting too much water. For best results, water your tree

whenever the soil feels dry an inch or two below the surface.

(Just stick your finger into the dirt.) Only water enough that

you'll need to give the tree another drink in a week or less.

Another frequent mistake

is to let your plant sit in a saucer of water

so that the bottom third of the soil in the pot is saturated with water

and unusable by the tree. One way to get around this is to drill

a few holes in the side of

your pot an inch or so from the bottom. Now your saucer will

overflow if you water too much (oops), but you won't fill the plant's

growing area up with water.

Indoors and outdoors

Dwarf citrus trees fall prey

to the usual banes of houseplants ---

scale, aphids, whiteflies, etc. You can go to great lengths to

delete these pest insects, but I prefer a simpler approach. As

soon as the last frost has passed in the spring, I move my houseplants

outside and let my garden's army of beneficial insects eat all the bad

bugs up.

Dwarf citrus trees fall prey

to the usual banes of houseplants ---

scale, aphids, whiteflies, etc. You can go to great lengths to

delete these pest insects, but I prefer a simpler approach. As

soon as the last frost has passed in the spring, I move my houseplants

outside and let my garden's army of beneficial insects eat all the bad

bugs up.

Growing your dwarf

citrus trees indoors in the winter and outdoors in the summer has other

benefits as well as insect control.

The extra sunlight gives your trees lots of energy to put out fruits,

and rains naturally cleanse the leaves. (Since citrus trees are

evergreens, their leaves can become dusty if raised solely indoors.)

Don't move your citrus

plants outside prematurely, though. They

can tolerate temperatures just above freezing for short periods, but

prefer 55 to 85 degrees Fahrenheit.

Pruning

How (or whether) you prune

your Meyer lemon depends on the size

you wish it to attain. In addition to the

tips here, you'll

want to prune away branches that cross or shade

other ones, just like you would with a fruit tree outdoors. You

can also decide whether to prune your Meyer lemon into an erect tree

shape or to let it grow as more of a bush with lots of branches that

arch up and then droop down with the weight of their fruits. If

you choose the latter route, most auhorities suggest training to the

three strongest trunks.

How (or whether) you prune

your Meyer lemon depends on the size

you wish it to attain. In addition to the

tips here, you'll

want to prune away branches that cross or shade

other ones, just like you would with a fruit tree outdoors. You

can also decide whether to prune your Meyer lemon into an erect tree

shape or to let it grow as more of a bush with lots of branches that

arch up and then droop down with the weight of their fruits. If

you choose the latter route, most auhorities suggest training to the

three strongest trunks.

The only reason your

tree would definitely need pruning is if it

sprouts below the graft union. Even if you can't pick out the

scar on the tree's trunk where the scionwood was grafted onto the

rootstock, you'll know the rootstock has sprouted if you see three-part

leaves instead of

simple leaves on your tree. Prune back all of

the rootstock sprouts and keep an eye on the tree since they may

come back.

| This post is part of our Dwarf Citrus lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

2011 was a very wet year for

our driveway.

One of the lessons learned

was to be flexible. Being able to drop everything and shift into

hauling mode when the ground dried up helped us to bring in several

truck loads of organic inputs in spite of the rain.

We usually get a few windows

of opportunity when the driveway freezes, but shoveling horse manure on

days like that is a bit beyond my skill level.

Yes, I admit it --- one

of my incentives for making the homesteading

internship property

a reality is to find a place to plant all of the persimmon seeds I've

been accumulating this fall. They seem to be jumping out of the

woodwork, and I'm itching to put them all in the ground.

First

came an intriguing package from down south. Pulling out the

ziploc baggies, I thought perhaps someone had sent me an early batch of

Christmas candy. But, not, it was one bag of very smelly coyote

scat and another of whole persimmons. I'll be excited to see

which does better --- the seeds that went through the animal, or those

that came straight out of the fruit.

First

came an intriguing package from down south. Pulling out the

ziploc baggies, I thought perhaps someone had sent me an early batch of

Christmas candy. But, not, it was one bag of very smelly coyote

scat and another of whole persimmons. I'll be excited to see

which does better --- the seeds that went through the animal, or those

that came straight out of the fruit.

Next, Mom brought me a

batch of local persimmons. Both of these first sets of seeds are

from trees that fruit early in the year, which would make great pasture

plants to fatten up fall broilers.

On the internship property

itself, I got sidetracked from inventorying all of the land's features

when I found this great fox scat on a log. The scat had dried up

and fallen apart, so I'm not sure whether the persimmon seeds I picked

out will sprout --- time will tell. (Most of the seeds in the

photo are Red Cedar seeds, just in case you're wondering.)

On the internship property

itself, I got sidetracked from inventorying all of the land's features

when I found this great fox scat on a log. The scat had dried up

and fallen apart, so I'm not sure whether the persimmon seeds I picked

out will sprout --- time will tell. (Most of the seeds in the

photo are Red Cedar seeds, just in case you're wondering.)

Then came the piece de

resistance --- my brother brought two ripe Asian

persimmons to

Thanksgiving. The fruits yielded only one seed apiece, but I'm

excited to give them a try for a handful of reasons. First, Joey

reports that the fruits are the non-astringent type of persimmon even

when unripe, and I didn't think that type survived this far

north. Second, I've read that Asian persimmons grafted onto

American rootstocks (like the ones I planted this fall) sometimes die

suddenly, so I'm excited to try an ungrafted Asian persimmon.

And, finally, these are a later-ripening variety, perfect for

stretching winter pasture.

I wrapped each seed in a

damp rag inside a ziploc bag and stored them all in the fridge.

Hopefully that will work to stratify the seeds and they'll sprout well

in the spring. Thank you

so much to each of my persimmon seed gatherers!

Now

for the fun part --- blooming! I suspect that some people get

dwarf Meyer lemons for the beauty and fragrance of the blooms alone,

not even caring about the fruits. Other dwarf citrus plants have

similar, but less showy, flowers, and the information below applies to

all of the common species.

Now

for the fun part --- blooming! I suspect that some people get

dwarf Meyer lemons for the beauty and fragrance of the blooms alone,

not even caring about the fruits. Other dwarf citrus plants have

similar, but less showy, flowers, and the information below applies to

all of the common species.

Meyer lemons can bloom

throughout the year, but they tend to bloom the

most in the winter, as do most other dwarf citrus trees. That

presents a problem since there are no bees flying around your living

room to pollinate the flowers. I've found that some flowers will

self-pollinate (especially if you shake the tree a bit), but you'll get

more fruits if you take a few minutes to hand-pollinate each new batch

of blooms.

The flowers are ready to be

pollinated when the pistil (green part in

the middle of the flower) is shiny and the petals are lush and

white. Simply take a small paintbrush (or your fingertip) and

gently tap the stamens of one flower to gather pollen, then tap the

pistil of another flower to fertilize that fruit. You'll have to

repeat this procedure a few times over the course of the bloom since

flowers open in stages, and some have already lost their petals (too

late to pollinate) by the time the last ones have opened.

The flowers are ready to be

pollinated when the pistil (green part in

the middle of the flower) is shiny and the petals are lush and

white. Simply take a small paintbrush (or your fingertip) and

gently tap the stamens of one flower to gather pollen, then tap the

pistil of another flower to fertilize that fruit. You'll have to

repeat this procedure a few times over the course of the bloom since

flowers open in stages, and some have already lost their petals (too

late to pollinate) by the time the last ones have opened.

Another option --- but

one I can't recommend --- is to open your window

during a sunny winter day and let your honeybees in. We did this

last year because our worker bees could smell the flowers' aroma

through the

screen and wanted in for such a luscious winter treat. The bees

pollinated our tree beautifully, but couldn't figure out how to get

back outside, and several perished.

No matter how you pollinate

the

flowers,

you'll know you've been

successful if the flowers drop their petals but maintain the green

ovary in the center. The tree will naturally thin itself,

dropping perhaps 75% of its flowers within a few days of full

bloom. Citrus trees generally go through a second round of

thinning a few weeks later when the fruits are pea- to

marble-sized. After this second thinning, you may choose to thin

a bit further so that there's no more than one fruit in each cluster.

No matter how you pollinate

the

flowers,

you'll know you've been

successful if the flowers drop their petals but maintain the green

ovary in the center. The tree will naturally thin itself,

dropping perhaps 75% of its flowers within a few days of full

bloom. Citrus trees generally go through a second round of

thinning a few weeks later when the fruits are pea- to

marble-sized. After this second thinning, you may choose to thin

a bit further so that there's no more than one fruit in each cluster.

Then you wait, and wait,

and wait. Our dwarf Meyer lemon

generally takes about eight months to ripen its fruits, which gives us

lemons in November or December. You can tell the fruits are ripe

by color (Meyer lemons should actually turn slightly orange) and by the

lift test --- gently lift a fruit upwards, and if the fruit is ripe it

will snap off the branch without any force on your part. Give one

fruit a taste and then pick the others if that one was juicy and sweet.

I won't bother to tell

you what

to do with the fruits.

They go

far too fast because they're so delicious. That's when you have

to be careful not to buy five more dwarf citrus trees, requiring you to

kick your kids out to take over their sunny room.

| This post is part of our Dwarf Citrus lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We found this battery charger at a

thrift store for 5 dollars back when we first started collecting tools.

We found this battery charger at a

thrift store for 5 dollars back when we first started collecting tools.

It usually takes all night

for a full charge compared to just a few minutes with the unreliable 5

in 1 portable power packs.

Makes me wonder if it's

easier on the battery to do the slow trickle charge?

How easy can it be to

build your soil? This patch of oats proves that two minutes of

planting in August can produce quite a bit of biomass.

You may recall that our

forest garden had grown up in a truly distressing fashion this

summer. After Mark whacked

all of the weeds down with his weed eater, there was a lot of soil

that had been shaded bare by the huge wingstem and other weeds. I

tossed handfuls of oats on the ground and ignored

them, figuring they'd either come up or get eaten by birds.

You may recall that our

forest garden had grown up in a truly distressing fashion this

summer. After Mark whacked

all of the weeds down with his weed eater, there was a lot of soil

that had been shaded bare by the huge wingstem and other weeds. I

tossed handfuls of oats on the ground and ignored

them, figuring they'd either come up or get eaten by birds.

I forgot to tell Mark

about my experiment, so he mowed through some of the cover crops, but

the patches he missed grew up quite nicely. They kept down any

late summer weeds and will probably provide semi-bare patches with a

light coating of mulch come spring. The soil won't be weed-free

and rich enough to plant vegetables directly into but will probably be

bare enough to plant a summer round of cover crops in the same quick

and dirty fashion. Those two minutes of gardening really paid off!

By

far, the most common dwarf citrus variety is the dwarf

Meyer lemon.

This variety was grown in containers in China before being

"discovered" by Frank Nicholas Meyer and brought to the United States,

and it is probably the best-suited variety for indoors

cultivation. Meyer lemons can handle lower temperatures during

fruit ripening, which is a factor that makes some dwarf citrus drop

fruits during indoor winters. We and our friends have had great

luck with Meyer lemons and only spotty luck with other varieties, so if

you want a sure bet, go for a dwarf Meyer lemon.

By

far, the most common dwarf citrus variety is the dwarf

Meyer lemon.

This variety was grown in containers in China before being

"discovered" by Frank Nicholas Meyer and brought to the United States,

and it is probably the best-suited variety for indoors

cultivation. Meyer lemons can handle lower temperatures during

fruit ripening, which is a factor that makes some dwarf citrus drop

fruits during indoor winters. We and our friends have had great

luck with Meyer lemons and only spotty luck with other varieties, so if

you want a sure bet, go for a dwarf Meyer lemon.

Variegated

Pink lemon is

another citrus well-suited to indoor growth. Like Meyer  lemons,

Variegated Pink lemons handle indoor conditions well, but the tree is

slightly larger, making it hard to fit in your living room.

lemons,

Variegated Pink lemons handle indoor conditions well, but the tree is

slightly larger, making it hard to fit in your living room.

Trovita

and Calamondin

oranges

are the easiest oranges to raise indoors according to some

websites. The Calmondin isn't actually a true orange, but a cross

between a kumquat and a tangerine, so don't expect big fruits.

We've only tried Washington

Navel orange,

which has set its first fruits this year. I'll keep you posted

about whether the Washington Navel keeps those tiny fruits and turns

into our second successful dwarf citrus variety.

Limes are interesting

because you can grow them either for leaves or for fruits (or

both.) Kaffir lime is the variety most often

grown for leaves used to season food. We're  currently growing a Dwarf Key

lime

--- no fruits yet, and it's about the same age as the Washington Navel

orange, but it's going to get another year of grace before we give up

on it.

currently growing a Dwarf Key

lime

--- no fruits yet, and it's about the same age as the Washington Navel

orange, but it's going to get another year of grace before we give up

on it.

Grapefruit often need

high heat to ripen fruit, so it's a bit tricky to grow them

indoors. Oro Blanco

grapefruit is

reputed to be delicious and also tolerant of indoor conditions.

Which dwarf citrus

varieties have you tried and loved or hated?

| This post is part of our Dwarf Citrus lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

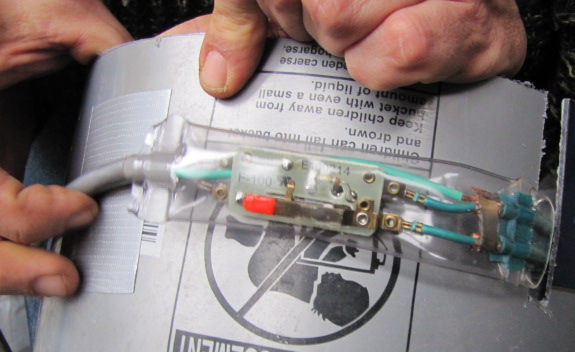

Our pipe

heating cable has a

thermostat pod encased in clear plastic.

The pilot light will come on

when the temperature reaches 38 degrees or you can push down on the

switch to activate it for testing purposes.

It's important to position

the pod so that the switch doesn't get pushed in by any type of

pressure, otherwise the unit will not shut off when it warms up.

I

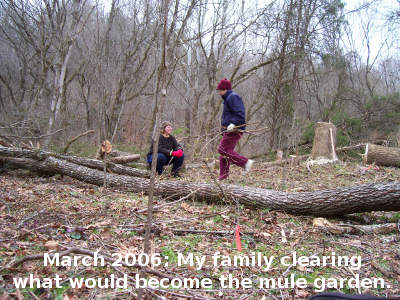

thought you all might be amused to see my ten year plan, written right

after purchasing the property in October 2003. Many of my goals

were later mitigated by Mark's realism, but it's still fun to see how

far we've gotten.

I

thought you all might be amused to see my ten year plan, written right

after purchasing the property in October 2003. Many of my goals

were later mitigated by Mark's realism, but it's still fun to see how

far we've gotten.

Generally:

1. To have repaid the

totality of the cost of the land. (Need to hurry up and pay off

the other $5,000 I owe my friend. I seem to have forgotten about

that debt in the excitement of living on the land.)

2. To be relatively self-sufficient, growing

the majority of the food I eat. To live simply, cut off as much as

possible from the consumer economy. (We do grow nearly all of our

vegetables and an increasing amount of our fruit and meat. I know

we don't live as simply as I had planned when I wrote my list in 2003,

but I think we've reached a good compromise.)

2. To be relatively self-sufficient, growing

the majority of the food I eat. To live simply, cut off as much as

possible from the consumer economy. (We do grow nearly all of our

vegetables and an increasing amount of our fruit and meat. I know

we don't live as simply as I had planned when I wrote my list in 2003,

but I think we've reached a good compromise.)

3. To have a small cash

crop, probably ginseng, possibly art or writing, to pay for cash

expenses. (Well, the ginseng got stolen by hunters and the art

and writing don't really pay the bills, but the chicken waterers do.)

4. To make no more money

than I need to pay for immediate needs and to put a small amount away

for retirement. (I guess this would be a failure --- we're making

more money than I planned to. On the other hand, we're doing our

best to give a lot of the excess back to the local community with

projects like our internship.)

5. To have half of my time free to draw and

write and take care of the woods. (This would be a total

win. If the week is divided into 14 work periods, we take four of

those off and I write for three of them.)

5. To have half of my time free to draw and

write and take care of the woods. (This would be a total

win. If the week is divided into 14 work periods, we take four of

those off and I write for three of them.)

6. Once my immediate

needs are met, to give surplus food to family and neighbors.

(Yes, we're giving away some surplus, although we could do more.)

Specifically:

7. Buildings - A house for me to

live in. Barn roof replaced so that barn can be used for tools, food

storage, and animals. A loft in the barn built for guest housing in

summer. A root cellar. A composting toilet. A greenhouse to grow food

in winter. Electricity to run a computer and lights. A phone line. A

mail box. (We're partway there. The trailer made the house

easy and we've saved the cash for the barn roof, even though we're

still talking to potential roofers. Joey's yurt has taken the

place of a loft in the barn and I decided that quick

hoops are better than a greenhouse for my uses. We've got the

composting toilet (or a semblence thereof), electricity, a phone line,

and a mail box. All we're really lacking is a root cellar.)

7. Buildings - A house for me to

live in. Barn roof replaced so that barn can be used for tools, food

storage, and animals. A loft in the barn built for guest housing in

summer. A root cellar. A composting toilet. A greenhouse to grow food

in winter. Electricity to run a computer and lights. A phone line. A

mail box. (We're partway there. The trailer made the house

easy and we've saved the cash for the barn roof, even though we're

still talking to potential roofers. Joey's yurt has taken the

place of a loft in the barn and I decided that quick

hoops are better than a greenhouse for my uses. We've got the

composting toilet (or a semblence thereof), electricity, a phone line,

and a mail box. All we're really lacking is a root cellar.)

8. Garden - an acre of garden

and orchard. The garden will begin by growing vegetables, and will work

up to supplying all berry fruits, vegetables, grains, and beans used by

me and my animals with enough to store for the winter and for guests.

The orchard will provide tree fruit. (We've got about two acres

of garden and orchard which feed us well, although we're still in the

early stages of growing food for our animals and haven't really got our

grains figured out.)

8. Garden - an acre of garden

and orchard. The garden will begin by growing vegetables, and will work

up to supplying all berry fruits, vegetables, grains, and beans used by

me and my animals with enough to store for the winter and for guests.

The orchard will provide tree fruit. (We've got about two acres

of garden and orchard which feed us well, although we're still in the

early stages of growing food for our animals and haven't really got our

grains figured out.)

9. Animals - Chickens, probably about three,

to feed me eggs and to live primarily on scraps from me with some

grains grown for them. A goat (possibly 2) to provide me dairy

products. To set up arrangements with neighbors to give away/sell the

kids and mate my nanny once a year. (We've got a lot more

chickens than that and don't have the goats. On the other hand,

we have figured out meat animals a lot better than I thought we would

have, so it evens out.)

9. Animals - Chickens, probably about three,

to feed me eggs and to live primarily on scraps from me with some

grains grown for them. A goat (possibly 2) to provide me dairy

products. To set up arrangements with neighbors to give away/sell the

kids and mate my nanny once a year. (We've got a lot more

chickens than that and don't have the goats. On the other hand,

we have figured out meat animals a lot better than I thought we would

have, so it evens out.)

10. To heat the house and cook with deadwood

from the property. (We've got the wood stove, but we do buy

firewood. This is one goal I'm happy with letting slide ---

buying firewood puts money into a local entrepreneur's pocket and gives

me time to write and Mark time to invent.)

10. To heat the house and cook with deadwood

from the property. (We've got the wood stove, but we do buy

firewood. This is one goal I'm happy with letting slide ---

buying firewood puts money into a local entrepreneur's pocket and gives

me time to write and Mark time to invent.)

11. To provide a means

of entry to the property for those who require a road or other

un-walking method. (So-so. If it's dry enough, we've got

the truck, and we also have the golf cart if we can figure out what

that noise is....)

It's also interesting to

see what I completely left out. Husband? Naw, not on my ten

year plan. Community? What's that? I guess I know

what will be on my next ten year plan --- making our sustainable

homestead reach beyond the boundaries of our property.

Replacing

the brake pads didn't make that rubbing sound go away.

It might be a bearing or the

motor. We've stopped using it for now.

At least it provides a nice

dry spot for Lucy to take a nap on.

Ben emailed to ask if I could recommend some books about "starting

up...going from the "normal" way of life...and ESCAPING and getting

into a permaculture lifestyle." Here are my top picks:

There are a lot of good homesteading

overview books,

but my favorite is John Seymour's The

Self-Sufficient Life and How to Live It. (Well, also my Weekend Homesteader

series, of

course.) This type of book will grab your

attention about a lot of different projects, but you'll need to look in

other directions once you choose a certain area you're interested in.

In my opinion, vegetable

gardening

is at the heart of homesteading, so you might start your more in depth

reading there. Lee Reich's Weedless

Gardening and Steve

Solomon's Gardening

When it Counts are two of the best books for helping you start in a

permaculture fashion. A lot of beginners prefer Mel Bartholemew's

Square

Foot Gardening, but

I find the technique expensive and not as

focused on soil health. Speaking of which, Teaming

With Microbes by

Jeff Lowenfels is a beautiful and easy to read

primer on what's going on in your dirt.

Chickens should also be

considered low-hanging fruit in the homesteading world. By far

the best book on incorporating chickens into a permaculture homestead

is Harvey Ussery's The

Small-Scale Poultry Flock. I'm still in the

middle of that

book since it came out not long ago, so no lunchtime series on it

yet. (Speaking of which, most of the links in this post point you

toward my summaries of the top points in each book, although a few just

send you to Amazon if I haven't written a post about that book yet.)

In terms of general

permaculture

information, a

lot of people love Toby Hemenway's Gaia's

Garden. For

some reason, I didn't get into the book when I

flipped through it, but I

Edible

mushrooms are

easy and

fun and are one of the hidden sides of the permaculture garden. I

recommend reading Paul Stamets' Mycelium

Running for

inspiration, but starting with something simple like

oyster mushrooms in logs. (I don't have a more basic edible

mushroom book to recommend, but there are lots of resources on the

internet.)

There are also a range of inspirational,

memoir-type books

you might be interested in. The most

well known is The

Good Life by Helen

and Scott Nearing. Possum Living

by Dolly Freed is a fun book written by an 18 year old about "how to

live well without a job and with (almost) no money." More

recently, Barbara Kingsolver's Animal,

Vegetable, Miracle

covers one family's experience eating locally

and in season.

If you're interested in

the traditional

cultures that

spawned many modern permaculture techniques, you

might want to check out Farmers

of Forty Centuries by FH King.

And, finally, I have to

plug our own book, Microbusiness

Independence, which

helps you fund

your homesteading adventure.

So, what am I

missing? What are the best introductory books for

off-grid living, sustainable building, aquaculture and other

homesteading topics I'm not as up to date on? I hope you'll

comment with your own beginners' reading list.

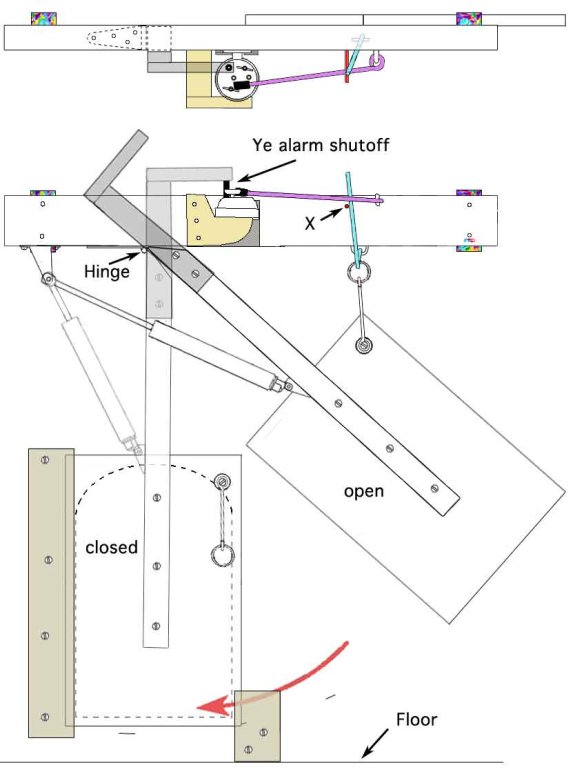

Dragonflypower.com has details on a new automatic

chicken coop door closer.

It's quite an advanced

version of the alarm

clock coop closer and in

my opinion deserves some attention for those thinking of making their

own similar contraption.

We try to report our failures

here as well as our successes. So I feel obliged to admit that we

only managed to attend a quarter of the Acres USA

conference.

We try to report our failures

here as well as our successes. So I feel obliged to admit that we

only managed to attend a quarter of the Acres USA

conference.

We drove up to Ohio

Monday so Mark could attend the first part of his pre-conference course

Tuesday. The pre-conference classes were amazing, but by the time

they ended on Wednesday night, Mark and I knew we couldn't survive

another day getting up before dark, coming home after dark, and staying

inside a huge conference center for the time in between.

Yes, there were a dozen

Amish people at the pre-conference. No, they didn't seem to be as

badly affected by the concrete jungle as we were.

I was dying to see

Harvey Ussery (oh, and Joel Salatin), both of whom spoke Friday.

I was itching to listen to in-depth lectures on plant secondary

metabolites, cover crops, and more. I wanted to peruse the

bookstore and trade show, and to hear more about Fertrell's

Nutri-Balancer (which pastured poultry keepers seem to swear by.)

But we couldn't do it.

I like to pretend that the

reason we stay home so much is because the farm needs us, but the truth

is we need the farm much more. I don't think we relaxed until we

stepped out of the car on the edge of the hay field, waded through the

flood waters, and fired up the wood stove.

I like to pretend that the

reason we stay home so much is because the farm needs us, but the truth

is we need the farm much more. I don't think we relaxed until we

stepped out of the car on the edge of the hay field, waded through the

flood waters, and fired up the wood stove.

Note to self: Two days

of conference is about our max. No way can we combine a

conference with a family visit --- preferably, we'd plan it so that

half of each conference day was silent contemplation time. Live

and learn....

Note to readers: All is

not lost! Once I digest the experience a bit more, I'll have a

really awesome lunchtime series on Mob Grazing for you. And I

think I can get a partial refund and use it to get MP3s of most of the

conference. Stay tuned.

We had one of the plastic

nubs to break off from our small Whirlpool

refrigerator.

I didn't think super glue

or epoxy would be strong enough, so I found a dull drill bit that was

the right diameter and installed it far enough in so it sticks out like

the old nub did.

The middle section of the

door is no doubt filled with some kind of styrofoam, which is why I

drilled a smaller pilot hole first to help get the bit positioned as

straight as possible.

It works fine and feels like

a long lasting solution.

Mark's

step-mom, Jayne, decided to convert her garden to no-till.

Previously, she had used her mulching mower to shred tree leaves and

grass clippings from her lawn, then applied the organic matter to the

vegetable garden as a generous coating of mulch. However, she

also tilled the soil every spring and fall.

Mark's

step-mom, Jayne, decided to convert her garden to no-till.

Previously, she had used her mulching mower to shred tree leaves and

grass clippings from her lawn, then applied the organic matter to the

vegetable garden as a generous coating of mulch. However, she

also tilled the soil every spring and fall.

In fall 2010, Jayne

stopped tilling, but kept adding mulch. Come

spring, she simply pulled the mulch back from directly over top of her

seeds (or seedlings), then scooped the mulch back into place around the

plants once they were up and running. Despite using the same

amount of mulch as in previous years, Jayne reported that this

year's garden had far fewer weeds than earlier gardens had.

In

addition to deleting weeds, Jayne's heavy mulching campaign seems to

have created a warmer microclimate that has allowed her garden plants

to thrive deep into the winter. She lives in zone 5, at the edge

of a huge cornfield which lets the Midwestern wind whip through her

garden --- this is a much colder spot than my zone 6, windless

garden. And yet, Jayne had unprotected arugula and other salad

greens thriving on December 8. (In contrast, the salad greens I

didn't place under quick

hoops are already

two thirds dead.)

In

addition to deleting weeds, Jayne's heavy mulching campaign seems to

have created a warmer microclimate that has allowed her garden plants

to thrive deep into the winter. She lives in zone 5, at the edge

of a huge cornfield which lets the Midwestern wind whip through her

garden --- this is a much colder spot than my zone 6, windless

garden. And yet, Jayne had unprotected arugula and other salad

greens thriving on December 8. (In contrast, the salad greens I

didn't place under quick

hoops are already

two thirds dead.)

Under her row cover

fabric, Jayne's broccoli and cabbage were

thriving. We looked under the covers when outside temperatures

were in the low 20s, and there did seem to be some frost on the stems

of the broccoli, but the heads looked fine. Could the heavy

organic matter be helping these broccoli hang on?

Are you inspired to

change over to no-till next year? A good place to start is with

my Weedless

Gardening lunchtime

series.

We finally found someone to

fix the barn roof that has experience and helpers.

It's going to take 52 pieces

of 14 foot long 26 gauge tin to get the job done.

Our new guy thinks it will

take him and a co-worker 3 or 4 full days. We agreed on 1800 dollars,

and he offered to have him and his guys carry back the tin through our

flood plain if we can't figure out a mechanized way of doing it. I

asked him how much he needed up front and I was relieved when he said

25 percent the first day. I once paid a guy to build a cinder block

fence in Las Cruces, New Mexico and learned the hard way that

motivation levels can vary when it comes to finishing a job.

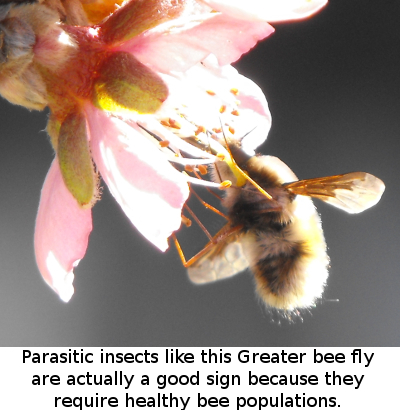

Our two bee hives have been

awfully quiet for the last few weeks. No one out flying on warm

sunny days. No perceptible buzz when I leaned down to press my

ear against the hive body. But I didn't think anything could be

wrong. In November, the hives were well-stocked

with honey and low

enough on varroa mites

that I didn't need to worry. We haven't had any terribly cold

spells yet. I just figured I wasn't paying enough attention.

Our two bee hives have been

awfully quiet for the last few weeks. No one out flying on warm

sunny days. No perceptible buzz when I leaned down to press my

ear against the hive body. But I didn't think anything could be

wrong. In November, the hives were well-stocked

with honey and low

enough on varroa mites

that I didn't need to worry. We haven't had any terribly cold

spells yet. I just figured I wasn't paying enough attention.

Unfortunately, my gut

was right and my head was wrong. I opened up the hives and found

them...empty. Chock full of honey, but no bees live or dead.

I usually poo-poo

backyard beekeepers who swear their bees died of Colony Collapse

Disorder. I believed (and still do) that we tend to jump to that

conclusion without checking the data. Our two hives that died

last winter, for

example, showed clear signs of starvation --- bees dead on the comb

with their heads stuck in empty cells. It's easy to just write

off anything as "Colony Collapse Disorder --- not my fault", but the

truth is that a dead hive often is the beekeeper's fault.

Which

is not to say that Colony Collapse Disorder never comes to the

backyard. If your bees are simply gone and the honey is untouched

(even by robber bees), you might be the unfortunate recipient of this

difficult to diagnose disorder. This week, I did start to see a

few robber bees visiting my empty hives, but I suspect the honey-rich

hives had been untouched for a few weeks before that. All of the

data points toward Colony Collapse Disorder being the culprit in this

case.

Which

is not to say that Colony Collapse Disorder never comes to the

backyard. If your bees are simply gone and the honey is untouched

(even by robber bees), you might be the unfortunate recipient of this

difficult to diagnose disorder. This week, I did start to see a

few robber bees visiting my empty hives, but I suspect the honey-rich

hives had been untouched for a few weeks before that. All of the

data points toward Colony Collapse Disorder being the culprit in this

case.

I'm going to extract the

honey and then put on my thinking cap. When we started with bees,

we got free

Langstroth equipment,

but I'd like to research whether top bar hives or Warre hives are more

likely to keep our bees healthy. We also bought package

bees from afar, and I'd like to see if we can find a local person

breeding bees well adapted to our area. Alternatively, perhaps we

should look into strains other than Italian if we have to buy in more

bees from far-flung sources. But whatever we change, we will be bringing bees back to the

farm, and hopefully our next experiment with bees will do better than

our last.

We've been trying to merge

our two chicken flocks into one happy group.

It's not going as planned.

The Light

susex breed is still

warming up to our Black

Australorp rooster and his girls. I think he's been chasing them

out of the coop. They've been huddling in a corner of the pasture the

past couple of nights so I decided to build them the above chicken coop

anex.

You can find used

50 gallon plastic barrels

at some feed stores for under 10 dollars. It only took a few minutes to

cut out the entrance with a jig saw.

When I went out to pick

these potsticker fixings, the cabbage head

was frozen clear through, but it thawed out and made a pretty tasty

dinner. This last cabbage plus parsley and Egyptian onions are

the only edibles currently growing uncovered in the garden, but we've

still got plenty of greens and lettuce under the quick

hoops.

We've also been eating a

bit out of the freezer this month --- two gallons down. Very

similar to our larder situation last

year, and plenty

more in the garden, freezer, and kitchen shelf so that we can keep

eating our own produce until spring.

One

of our favorite readers shared with us recently how she upgraded the

pneumatic wheels on her yellow wagon to solid wheels from Harbor Freight.

(Thanks Jayne)

One

of our favorite readers shared with us recently how she upgraded the

pneumatic wheels on her yellow wagon to solid wheels from Harbor Freight.

(Thanks Jayne)

It's an advanced upgrade that

required four metal sleeves to make them fit.

If we didn't have so much mud

to deal with I might do a similar operation on our TC1840H

garden wagon.

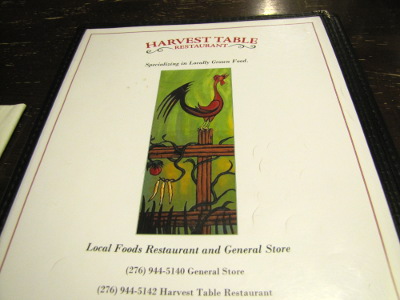

Steve Hopp started the Harvest

Table Restaurant in

Meadowview, Virginia, based on the concepts outlined in his wife's

book, Animal,

Vegetable, Miracle.

The restaurant "work[s] with seasonal produce and meats from local and

regional sources, offering the best of each season."

Steve Hopp started the Harvest

Table Restaurant in

Meadowview, Virginia, based on the concepts outlined in his wife's

book, Animal,

Vegetable, Miracle.

The restaurant "work[s] with seasonal produce and meats from local and

regional sources, offering the best of each season."

In theory, the idea is

very sound, but in practice, this

article from July

2011 reports that the restaurant has yet to turn a profit. The

problem is pretty simple and is one of the first  things I noticed during our

recent visit --- price. Mark and I took our movie star neighbor

out on Saturday night and were a bit shocked that dinner for three (all

of us drinking water, but we did get two desserts and two starter

soups) came to $70, plus tip. In an area where the average annual

income is barely above the poverty line, a $28 meal is a hard

sell. (Yes, we always tip more than 15%. Mark has done his

time as a waiter and knows servers deserve it.)

things I noticed during our

recent visit --- price. Mark and I took our movie star neighbor

out on Saturday night and were a bit shocked that dinner for three (all

of us drinking water, but we did get two desserts and two starter

soups) came to $70, plus tip. In an area where the average annual

income is barely above the poverty line, a $28 meal is a hard

sell. (Yes, we always tip more than 15%. Mark has done his

time as a waiter and knows servers deserve it.)

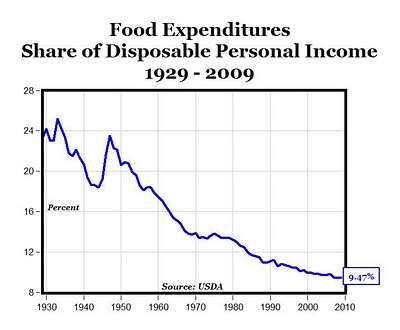

Our trip to the Harvest Table

was a thought-provoking lesson in practicing what we preach. I've

long said that if we bought our food from ethical sources --- pastured

meat and in-season produce raised by small farmers --- we'd be paying

twice as much for groceries. Realistically, that means eating out

half as often and cutting back on the pricey items (or growing them

ourselves.)

Our trip to the Harvest Table

was a thought-provoking lesson in practicing what we preach. I've

long said that if we bought our food from ethical sources --- pastured

meat and in-season produce raised by small farmers --- we'd be paying

twice as much for groceries. Realistically, that means eating out

half as often and cutting back on the pricey items (or growing them

ourselves.)

Unfortunately, that also

means leaving the poor out of the equation. I suspect that very

few locals eat at the Harvest Table and that the restaurant instead

gets most of its business from  tourists passing through on

the nearby I-81. I'm not sure what the solution is to that thorny

problem (except that gourmet food is one of the items we can all grow

with a little time and space.)

tourists passing through on

the nearby I-81. I'm not sure what the solution is to that thorny

problem (except that gourmet food is one of the items we can all grow

with a little time and space.)

For those of you who

live far away (or can't afford the high prices), the Harvest Table

could provide a simpler lesson. Keep an eye on their specials on facebook for ideas about cooking

totally in-season meals of your own. Or drop by the restaurant to

check out their selection of permaculture books and local crafts.

Went to the big city today

for an eye check up and some plywood.

Figured out that if you have

the guy at Lowes cut a sheet of plywood in 2 foot sections it will

perfectly fit in the trunk of our Toyota.

Next

month's volume of Weekend Homesteader includes in-depth information

on:

Next

month's volume of Weekend Homesteader includes in-depth information

on:

- Backup lighting for power outages

- Rotational chicken pastures, coops, and tractors

- Soil testing basics

- The science of baking bread (and pizza)

For those of you who

are

new to Weekend Homesteader, this series walks

you through the basics of growing your own food, cooking the bounty,

preparing for

emergency power outages, and achieving financial independence.

I hope you'll consider

splurging 99 cents to buy

a copy of my newest ebook from Amazon's

Kindle store. And many

thanks in advance if you can find the

time to write a brief review.

As usual, I'm also very

glad to email you a free pdf copy to read if you

don't have the spare cash, or just don't want to deal with downloading

an app so you can

read the ebook on your computer or phone. Just email

me with your request --- no strings attached. (Plus,

I'm trying out a new system on Amazon, so the book will be free there

next Monday through Friday.)

As usual, I'm also very

glad to email you a free pdf copy to read if you

don't have the spare cash, or just don't want to deal with downloading

an app so you can

read the ebook on your computer or phone. Just email

me with your request --- no strings attached. (Plus,

I'm trying out a new system on Amazon, so the book will be free there

next Monday through Friday.)

Don't forget that Weekend

Homesteader: December

is still available, full of tips on fruit trees, emergency

preparedness, and more. Thanks for reading!

Want

to make some fun and easy gifts for the backyard chicken keeper on your

list? It's too late to start the plants this year, but a couple

of hills of egg gourds might fit the bill in 2012.

Want

to make some fun and easy gifts for the backyard chicken keeper on your

list? It's too late to start the plants this year, but a couple

of hills of egg gourds might fit the bill in 2012.

The egg gourd is a type

of decorative gourd that looks astonishingly similar to chicken

eggs. Maggie gave me three, which will soon be replacing golf balls

as nest eggs in the

chicken coop. If you do a google image search for "gourd eggs",

you'll see dozens of crafty alternatives to make use of these

non-edible squash.

Thanks, Maggie!

I'm still in awe each time I

pass by Anna's quick

hoop experiments.

The pay off is pretty huge

when you consider how many fresh garden salads we continue to have on a

daily basis thanks to a mixture of cut pieces of rebar, PVC, and some Agribon

material.

I remember this time last

year dreaming of fresh leafy greens in a gastronomical sense of the

word.

I've

been enjoying the thought-provoking discussion in the comments section

of my Harvest

Table review.

Specifically, Lisa's question got me thinking about how much time and

money we put into our vegetable garden.

I've

been enjoying the thought-provoking discussion in the comments section

of my Harvest

Table review.

Specifically, Lisa's question got me thinking about how much time and

money we put into our vegetable garden.

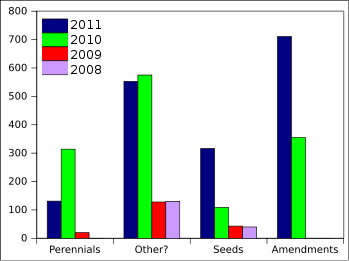

The chart to the left

shows our garden expenditures for the last four

years. The reason I went so far back in time is because I tend to

spend a lot more money on the garden when I have the cash since I think

of items like straw, cover crop seeds, and fruit trees as an investment

in our farm's future health. But I don't want anyone to think you

have to set aside $1,000 per year to grow your own vegetables.

When we were pinching pennies in 2008 and 2009, we spent less than $200

annually and still managed to grow a lot of food, even if we didn't

build our soil and increase our long term capacity with perennials.

How about time? I

estimate we put in about 540 hours over the

course of the year working in the garden. That's where the real

"money" comes in, depending on whether we want to give ourselves

minimum wage ($3,915) or the amount I make on ebooks (about $25/hour,

which would make our garden time worth $13,500.) To be honest,

though, most farmers don't even make minimum wage, so they probably

would consider my time worth more like $2,000. That lowball

figure would put our total

time and money expenditures at $2,200 to

grow all of our own vegetables (and some of our fruit), while a more

realistic figure is $14,500.

How about time? I

estimate we put in about 540 hours over the

course of the year working in the garden. That's where the real