archives for 11/2011

This year, Mark build a bunch

of chicken pastures that act as moats around a large portion of

the garden. I love the moats --- they keep the deer out, make the

edges distinct, and just make me feel relaxed. We have had a

couple of issues, though, that I'd like to remedy before boxing in the

rest of the boundary.

This year, Mark build a bunch

of chicken pastures that act as moats around a large portion of

the garden. I love the moats --- they keep the deer out, make the

edges distinct, and just make me feel relaxed. We have had a

couple of issues, though, that I'd like to remedy before boxing in the

rest of the boundary.

Lucy's job is to patrol

the perimeter, and that's a bit tough when she can't get there.

We started to notice gaps

gnawed in our fences,

and then realized that Lucy was making bolt-holes so she can spring off

in any direction to reach the edges of our homestead

lickety-split. The trouble is that deer and chickens come in

those holes and end up in the garden, which defeats the purpose of the

moats. Surely there's a way to give Lucy better access to the

perimeter without compromising our fences, but I'm not sure what it

would be. I was pondering stiles (like in the photo above), but

an agile chicken or (if we go there) goat could prance over top just as

easily as a dog could. As crazy as it sounds, I'm now thinking of

installing dog doors in select locations in the pasture fences, but any

other ideas would be appreciated as well.

The

chicken problem is similar to Lucy's dilemma. Since we started

letting our chickens free

range, we've had chickens stuck partway home multiple times.

As dusk falls, chickens seem to use a compass sense (maybe based on

magnetism?) to figure out how to shorten their peregrination and head

straight back to the coop. The problem is that there's often a

fence in their way, so they end up huddled in a corner, not realizing

that if they simply walked at right angles for a few feet, they could

get home. The chickens do seem to learn the terrain after a

while, so we might just have to plan on leading chickens home a few

times when they start free ranging. Maybe another solution would

be to make all exterior fences convex instead of concave?

The

chicken problem is similar to Lucy's dilemma. Since we started

letting our chickens free

range, we've had chickens stuck partway home multiple times.

As dusk falls, chickens seem to use a compass sense (maybe based on

magnetism?) to figure out how to shorten their peregrination and head

straight back to the coop. The problem is that there's often a

fence in their way, so they end up huddled in a corner, not realizing

that if they simply walked at right angles for a few feet, they could

get home. The chickens do seem to learn the terrain after a

while, so we might just have to plan on leading chickens home a few

times when they start free ranging. Maybe another solution would

be to make all exterior fences convex instead of concave?

I'm curious to hear some

creative solutions to our moat problems, so I hope you'll leave a

comment with your ideas!

The first step in rotating your

garden is to understand which

vegetables share the same family. The list below covers all of

the vegetables you're likely to grow, and I've italicized the more

common crops so they'll be easier to find.

The first step in rotating your

garden is to understand which

vegetables share the same family. The list below covers all of

the vegetables you're likely to grow, and I've italicized the more

common crops so they'll be easier to find.

Amaranthaceae --- Amaranth

Amaryllidaceae --- Chives, garlic, leeks, onions

Basellaceae --- Malabar spinach

Brassicaceae --- Asian greens, broccoli, broccoli raab, Brussels

sprouts, cabbage, cauliflower, collards, cress, horseradish, kale, kohlrabi, mustard, radish, rape, rocket, rutabaga, turnip, watercress

Chenopodiaceae --- Beet, beetberry, Good King Henry,

lamb's quarter, mangel, orach, quinoa, spinach, Swiss

chard

Compositae --- Artichoke, cardoon,

celtuce, chicory, endive, escarole, gobo, Jerusalem artichoke, lettuce, salsify, shungiku, sunflower, yacon

Convolvulaceae --- Water spinach, sweet

potato

Cucurbitaceae --- Balsam apple, balsam

pear, cassabanana, chayote, cucumber, gherkins, gourd, luffa, melons, pumpkins, squash

Graminae --- Corn

Labiatae --- Basil, mint, thyme

Leguminosae --- Bean, lentil, pea, peanut, pigeon pea, soybean

Liliaceae --- Asparagus

Malvaceae --- Okra

Polygonaceae --- Rhubarb, sorrel

Portulaceae --- Miner's lettuce, purslane

Solanaceae --- Cape gooseberry, eggplant, garden huckleberry, ground

cherry, naranjilla, nightshade, pepino, pepper, potato, sunberry, tomatillo, tomato

Tetragoniaceae --- New Zealand spinach

Umbelliferae --- Carrot, celery, celeriac, chervil, coriander, dill, fennel, parsley, parsnip, skirret

Valerianaceae --- Corn salad

Although this list seems

overwhelming at first glance, a closer look

will show that the majority of your garden vegetables fit into just a

few families. Experienced gardeners have pet names for several of

them, so you'll hear folks talking about "brassicas" when they mean

broccoli, kale, and the like, "cucurbits" when they want to lump squash

and cucumbers together, and "legumes" when referring to peas and beans.

Although this list seems

overwhelming at first glance, a closer look

will show that the majority of your garden vegetables fit into just a

few families. Experienced gardeners have pet names for several of

them, so you'll hear folks talking about "brassicas" when they mean

broccoli, kale, and the like, "cucurbits" when they want to lump squash

and cucumbers together, and "legumes" when referring to peas and beans.

This

week's lunchtime series includes one of the four projects from Weekend

Homesteader: November.

Stay tuned for the rest of the series, or check out the 99 cent ebook

for more information on how to store drinking water for use during

power outages, to put an entire

chicken to use in the kitchen, and to bring in cash without going to

the office.

| This post is part of our Garden Rotation lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

80 bales of straw at 4

dollars a piece.

20 dollars for delivery and

stacking.

This should keep Anna's

mulch habit going all winter and part of the spring.

Around here, Samhain means hard freezes are on

their way. Time to take a break from weeding and mulching the

garden and do a bit of winterization, like:

- Putting hoses away --- Unhooking all of our sprinkler hoses and laying them out on a hill lets the water drain out. I wind them from the uphill side and put the hoses away in the barn until next year. Treated this way, we have cheap hoses that have already lasted 5 years and seem to have several more to go.

- Erecting quick

hoops --- Greens

and lettuce can handle frost, but I don't want to keep my eye on the

forecast and scurry around once temperatures in the mid twenties are

coming up. Row cover fabric lets hot air vent out on beautiful

sunny

days while protecting the

crops on cold nights, so it's okay to put my quick hoops up when

daytime temperatures rise into the 60s.

days while protecting the

crops on cold nights, so it's okay to put my quick hoops up when

daytime temperatures rise into the 60s. - Protect the fig --- The fig

held onto its leaves until this week's harder freezes, but now that the

plant is bare, I can erect its winter

protection.

And then it's back to putting

the garden to bed.

Happy Samhain/Halloween/All Soul's Day/Cross-Quarter Day!

Congratulations to John, the winner of our seed

giveaway!

John, please drop me an email with your mailing

address and we'll put your seeds (and top bulbs) in the mail on Friday.

Congratulations to John, the winner of our seed

giveaway!

John, please drop me an email with your mailing

address and we'll put your seeds (and top bulbs) in the mail on Friday.

Meanwhile, thank you to

everyone for helping make Weekend

Homesteader: November

a success! Don't forget that I'm always happy to email a free pdf

copy to our readers --- just email

me with your

request. And don't forget to leave a review on Amazon if get a

chance.

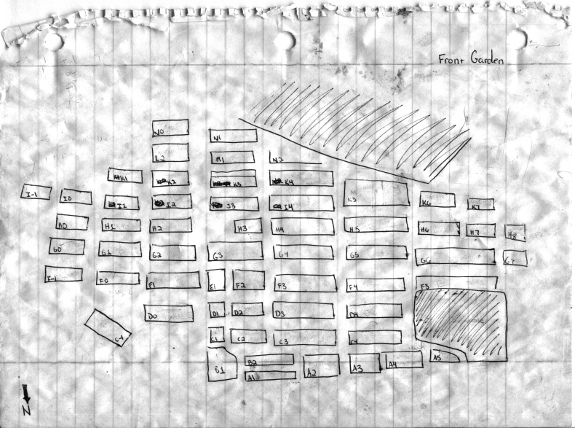

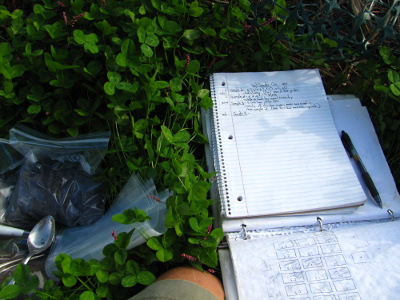

Unless you have a

stellar memory, garden rotation depends on good

notes. You may eventually decide to come up with your own method

for recording garden information, but for now I recommend you combine a

garden map with a spreadsheet.

If you haven't already

mapped your garden, the first step in this

week's exercise is to head out into the garden with pen and

paper. It's not really necessary to pace off boundaries and draw

your

garden to scale --- the idea is simply to mark down the main

features.

Those of you who have

permanent beds can sketch your garden once, scan

your drawing into the computer or make several photocopies, then never

have to repeat the drafting work. If that applies to you, I

recommend giving each garden bed a label so that you can quickly and

easily refer to it in your notes. I find it helpful to use a

number and letter combo to distinguish a bed, so the first row of beds

in my garden is labeled "A1", "A2", "A3", etc., the second row of beds

is labeled "B1", "B2", and so forth.

If you till up your

garden and create new rows every year, your

garden

map will be a bit fuzzier. (See the May

volume of Weekend

Homesteader for an

explanation of why permanent garden beds are better

for your soil.) But you can get the same general information

across by listing your tomatoes as grown in the southwest

quadrant. You'll probably want to draw a map each year showing

the location of each type of vegetable.

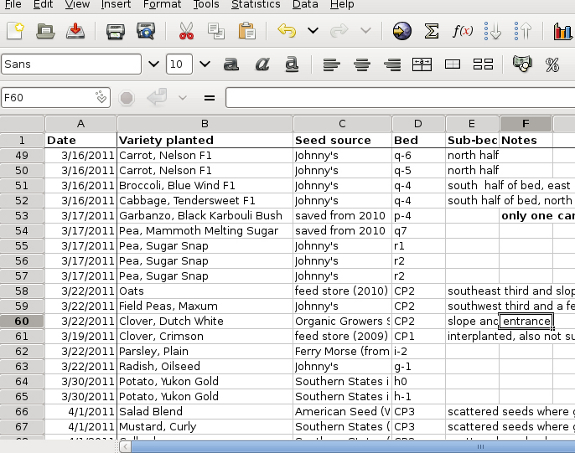

Either way, I recommend

coupling your garden map with a spreadsheet (or

at least a notebook if you're technophobic.) You can download my

garden

spreadsheet from 2011

to use as a template. Every time I plant a

bed, I note down the date, the vegetable variety, the seed source, and

the bed number. In some cases, I'll also record the portion of

the bed planted (if I'm combining more than one vegetable species or

variety in

the same bed), soil amendments I used, harvest information, and disease

and insect problems. You can put all of the same information in a

notebook, but using a spreadsheet makes it much easier to search

through your notes.

Either way, I recommend

coupling your garden map with a spreadsheet (or

at least a notebook if you're technophobic.) You can download my

garden

spreadsheet from 2011

to use as a template. Every time I plant a

bed, I note down the date, the vegetable variety, the seed source, and

the bed number. In some cases, I'll also record the portion of

the bed planted (if I'm combining more than one vegetable species or

variety in

the same bed), soil amendments I used, harvest information, and disease

and insect problems. You can put all of the same information in a

notebook, but using a spreadsheet makes it much easier to search

through your notes.

This

week's lunchtime series includes one of the four projects from Weekend

Homesteader: November.

Stay tuned for the rest of the series, or check out the 99 cent ebook

for more information on how to store drinking water for use during

power outages, to put an entire

chicken to use in the kitchen, and to bring in cash without going to

the office.

| This post is part of our Garden Rotation lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Our Chicago

Electric 5 in 1 portable power packs are just over a year old and I

thought it was time for a report.

The first one will only take

a 50% charge, while the second one is dead to the world.

The one still working came in

very handy during the 2011

power outage giving us the ability to keep the incubator going, We

only used the car

battery booster function twice.

It feels like whatever type

of battery these things have inside is underpowered. We might be able

to salvage the internal invertor if I can figure out a way to take it apart or

maybe there's a way to replace the battery with something more

substantial?

All's

well in both hives.

All's

well in both hives.

Last time I checked, I

was a bit concerned because my fall

feeding campaign had

caused

the queen in one hive to produce a lot of excess workers, but I needn't have

worried. Once the sugar water went away, I started seeing dead

bees in front of the hive, proving that the colony was just as quick

about deciding to slim their numbers back down so they didn't eat up

their winter stores prematurely.

I decided to feed the

other hive after seeing that they were 10 pounds shy of my winter goal

on October 3. It wasn't entirely purposeful, but since that hive

needed less extra honey, I let the sugar feeder run dry for a day or

two between each feeding, and the boom/bust cycle seems to have

prevented the queen from laying many extra eggs. Some queens are

simply more prone to increasing hive numbers when faced with lots of

sugar water than others, so it's possible this queen is just smarter

than the other one. Either way, though, it seems like making fall

feedings less continuous can't hurt.

With 60 pounds of capped

honey in the daughter hive, 51 pounds in the mother hive, and some

still dehydrating in each, it looks like our bees are ready for winter.

Now that you've got your

map and spreadsheet in hand, you can plan out

next year's garden. For those of you who have been gardening in

the same spot for several seasons, the goal is to make sure that plants

in the same family don't

share the same soil for at least three years. That means that you

don't want your summer beans to follow your spring peas and don't even

want those beans to be in a bed that has grown peas, beans, or peanuts

for at least three years.

Now that you've got your

map and spreadsheet in hand, you can plan out

next year's garden. For those of you who have been gardening in

the same spot for several seasons, the goal is to make sure that plants

in the same family don't

share the same soil for at least three years. That means that you

don't want your summer beans to follow your spring peas and don't even

want those beans to be in a bed that has grown peas, beans, or peanuts

for at least three years.

Some gardeners keep

rotation extremely simple by dividing their garden into four sections

and growing different families in each

section. For example, if the northeast quarter of your garden is

home to the legume family, the southeast quarter to potatoes and

tomatoes, the southwest quarter to cucurbits, and the northwest quarter

to everything else, you can simple turn your map like a wheel to plan

next year's garden. Now your legumes go in the southeast

quadrant, the tomatoes in the southwest quadrant, and so forth.

Unfortunately, the

method outlined above has several problems.

Chances are your garden isn't entirely uniform, so the wheel rotation

method would often require you to grow vegetables in spots they don't

prefer from time to time. In my garden, a third of the

growing area has deep, loamy soil that's good for root crops and

another third is very sunny and perfect for spring and fall

crops. That means my brassicas are nearly always located in

the sunny third while carrots and potatoes dominate the loamy

third. The June

volume of Weekend Homesteader walks you through locating

each part of your vegetable

garden in the proper space.

Even if you are growing

on a completely flat area with no shade and with the

same soil type throughout, planting big blocks of the same type of

vegetable

together is asking for trouble. With the exception of corn

(which requires a large planting in one spot to allow for wind

pollination of the seeds), you'll have far less insect and disease

pressure if you scatter each type of vegetable throughout the

garden. Big blocks of similar plants mimic monoculture and often

lead to insect and disease epidemics. At the other extreme, a

diverse garden with beans beside tomatoes beside parsley will make it

tough for problematic insects to find the plants they prefer while also

tempting beneficial insects to spend time in every part of the garden.

To add one more complication

to the mix, you should keep in mind that

you can often grow two or more different vegetables in the same bed

each year. For example, over-wintering garlic is harvested in

early

June, just in time to plant sweet potatoes. Spring leaf lettuce

takes

about a month to bulk up, can be cut for a month, and then turns

bitter, so I allot the lettuce two months out of the year. Your

notes

from last year will help you figure out how many months each crop will

take (and the May

volume of Weekend Homesteader explains when each one

should be planted), but there are always a few vegetables that are

pulled out early or don't come up. As a result, I generally plan

the

location for my vegetables in stages, first figuring out where each

variety will go for the spring planting (February to June) and only

later planning my summer and fall gardens.

To add one more complication

to the mix, you should keep in mind that

you can often grow two or more different vegetables in the same bed

each year. For example, over-wintering garlic is harvested in

early

June, just in time to plant sweet potatoes. Spring leaf lettuce

takes

about a month to bulk up, can be cut for a month, and then turns

bitter, so I allot the lettuce two months out of the year. Your

notes

from last year will help you figure out how many months each crop will

take (and the May

volume of Weekend Homesteader explains when each one

should be planted), but there are always a few vegetables that are

pulled out early or don't come up. As a result, I generally plan

the

location for my vegetables in stages, first figuring out where each

variety will go for the spring planting (February to June) and only

later planning my summer and fall gardens.

This

week's lunchtime series includes one of the four projects from Weekend

Homesteader: November.

Stay tuned for the rest of the series, or check out the 99 cent ebook

for more information on how to store drinking water for use during

power outages, to put an entire

chicken to use in the kitchen, and to bring in cash without going to

the office.

This post is part of our Garden Rotation lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: This post is part of our Garden Rotation lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We ended up trading our old Toyota

mini-van for a 22 rifle and the few hours of labor it took to

replace the golf cart brake pads.

I've been dreading the last

part of the deal...getting the seats from our barn to the parking area

without the help of the truck.

The TC1840H

garden wagon was a big

help today, but it took some major effort to make it across the creek

due to one of the wheels rubbing on the frame when our

friend pulled too fast.

Not sure if it's something I

can fix to make stronger. Maybe it's time to consider the next step up

in garden wagons?

Step

1: Dream

Step

1: Dream

When

I was a kid, I dreamed of publishing a book. I didn't care about

the fame, but Daddy had explained the concept of royalties to me, and

the idea of doing a bunch of work and then having money trickle in for

the rest of my life sounded really awesome. Plus, I just loved

books.

Step 2: Strive

I started writing

"novels" in elementary school, but it took until

after college for me to realize that I lacked the life experience to

write good fiction. In the interim, I agonized over a bunch of

young adult fiction, pored over Writer's

Market, and even

sent some "novels" off to publishers to get those mandatory rejection

letters.

Step 3: Check in with reality

Time passed and I got an actual

job, which I loved and then

hated. After I quit, a local businessman threw a book deal into

my lap --- I'd write about the local flora and fauna, his niece would

format it, and he'd publish it. I hunkered down over my laptop

for a month or two and spewed forth my first non-fiction

book. It

had growing pains, but the breaking point was realizing that when the

businessman said he'd publish it, he merely meant he'd print it.

There was no distribution involved, and I would need to hawk my

book on street corners to get it sold. No way! That was

going to irritate my introvert tendencies more than the job I just

quit. I published the book in ebook format instead.

Time passed and I got an actual

job, which I loved and then

hated. After I quit, a local businessman threw a book deal into

my lap --- I'd write about the local flora and fauna, his niece would

format it, and he'd publish it. I hunkered down over my laptop

for a month or two and spewed forth my first non-fiction

book. It

had growing pains, but the breaking point was realizing that when the

businessman said he'd publish it, he merely meant he'd print it.

There was no distribution involved, and I would need to hawk my

book on street corners to get it sold. No way! That was

going to irritate my introvert tendencies more than the job I just

quit. I published the book in ebook format instead.

Step 4: Revise the dream

Step 4: Revise the dream

Hmm, ebooks. Now

that's an interesting idea. I churned

out

a few more, getting

better at the process and enjoying writing about a

topic where I really had something to say. After a while, I

realized that I could reach a much wider audience by selling my ebooks

on Amazon rather than just on my website, and with your help, my Weekend

Homesteader

series took off. This was the cat's meow! No need to hold

book signings when I could rely on the power of the internet to sell my

books.

I came to the conclusion

that paper books were good for nothing more

than stroking the author's ego. I figured that if I were a

publisher, I'd cyber-stalk Amazon's independent ebook authors and watch

who sells the most books, then approach them in hopes of publishing the

book in a paper format. I steeled myself for that day --- if a

publisher approached me, I would simply say no.

Step 5: Revisit the dream

I thought the email was spam

at first. But no, it was a small but

established publisher that had several well known books under their

belt. They wanted to publish a full color paperback version of my

Weekend

Homesteader series.

I poised my fingers over the keyboard to say no...then went to tell

Mark instead.

"You know that if you

don't at least ask them for the terms, you'll

always wonder," he told me. "Why don't you email them back and

ask what advance and royalties they'd offer?"

Well, okay. The

editor tossed off some figures on the low end of

normal (8% royalties, $1,500 advance.) I shrugged.

Interesting --- I'd write a post about it after telling the publisher

no.

Instead, I drafted a

lengthy pro-con list. The pro list was short, the con list long,

long, long.

Daddy picked up the

phone right away. "I'm shocked!" he said once

he heard who was there. (Yes, I don't call my father

enough. No, I hadn't told him the reason for my call yet.)

"A publisher wants to

make a print copy of my book," I

told him, then added: "But I think I should say no."

I didn't think I could

ever break Daddy's heart more than when I

decided to live in a trailer, but I could almost hear that essential

organ cracking into two uneven pieces. He immediately started

trying to talk me into it, so I explained my list of disadvantages

one at a time. After "deadlines, angst, stress", my perfectionist

belief that Weekend

Homesteader

isn't ready for prime time, and having to deal with criticism, I asked

him whether accepting the first publisher who comes knocking isn't a

bit like going to the prom with a boy simply because you're flattered

he asked. "No, no!" Daddy said. "It doesn't matter who

publishes your first book! Just who publishes your second.

And, by the way, about your perfectionist tendencies, you've heard of

second editions, right?"

Finally,

I moved on to the real sticking point --- public

appearances. "You could try asking the publisher how they

distribute the book and what you'd be expected to do," Daddy said

soothingly. So I sent the publisher back an email they probably

don't get often. I told them I was a hermit. I told them

there was no way I was going to market the book in a non-internet

manner. What bookstores did they have their books in, who was

their distributer, how were they going to advertise the book, how

quickly do they remainder? The answers sucked me right in --- not

so much the part about being in mainstream bookstores throughout the

U.S. and Canada (although that was cool), but about being sold in

Tractor Supply. Tractor Supply would really reach my target

audience and help build our "empire"!

Finally,

I moved on to the real sticking point --- public

appearances. "You could try asking the publisher how they

distribute the book and what you'd be expected to do," Daddy said

soothingly. So I sent the publisher back an email they probably

don't get often. I told them I was a hermit. I told them

there was no way I was going to market the book in a non-internet

manner. What bookstores did they have their books in, who was

their distributer, how were they going to advertise the book, how

quickly do they remainder? The answers sucked me right in --- not

so much the part about being in mainstream bookstores throughout the

U.S. and Canada (although that was cool), but about being sold in

Tractor Supply. Tractor Supply would really reach my target

audience and help build our "empire"!

With the invaluable

assistance of my friend's husband (thanks,

Seth!), I poked at the contract

until it felt pretty feasible.

And then...I said yes.

(If you were hoping that

this post would actually help you get

published, you've probably realized it won't. Those of you who

noticed that the path of my publishing career looks an awful lot like

the way I got a

husband win bonus points.)

(If you were hoping that

this post would actually help you get

published, you've probably realized it won't. Those of you who

noticed that the path of my publishing career looks an awful lot like

the way I got a

husband win bonus points.)

Which is all an

excessively long way of saying that a full color paperback edition of Weekend

Homesteader will

be hitting bookstores in fall of 2012. I'll be dealing with

"deadlines, angst, stress" in February and before then will be asking

all of our ebook readers for their feedback so that the paper edition

glows. For the next little while, though, I'm going to channel

the eleven year old me and tell her that getting published really is

possible and not

to give up.

The problem with a diverse

garden is that planning rotation can be a

mind-bending exercise if you grow in a large space. Luckily,

there are ways to simplify the process.

The first step toward

easy rotations is to figure out which

families

cover the most ground in your garden. These widespread families

will vary depending on what you like to eat, of course, but I always

struggle to find fresh ground for legumes, brassicas, cucurbits, the

onion family, and the tomato family. Everything else is pretty

easy since, for example, I just don't grow enough okra to make it

difficult to find the vegetable a home in next year's garden.

You could do worse than

to start off your rotation by deciding on

spots

for the members of the five prolific families mentioned above.

Make a list of all of the vegetables you grow in each family and divide

them up by planting date, then start finding homes for each crop from

earliest planted to latest planted. Don't worry if you're stumped

and can't find a good spot for the latest planted vegetables ---

openings

generally come up and let you squeeze the last few in.

The steps I use when

deciding on a spot for each vegetable in next year's garden are as

follows:

1.

Decide how many beds to devote to the crop.

I keep notes on how much I preserve of each type of vegetable and of

the month when

I ran out of those stored foods in the winter. If I had to buy

tomatoes starting in February, that's a clue that I should plant more

beds next year. On the other hand, if I ended up with peppers

that I didn't want to eat when the time came to clean out the freezer

in the spring, I might as well grow fewer this year.

Don't get too carried away, though --- if this is your first or

second year gardening, you'll want to keep your garden small and

manageable.

1.

Decide how many beds to devote to the crop.

I keep notes on how much I preserve of each type of vegetable and of

the month when

I ran out of those stored foods in the winter. If I had to buy

tomatoes starting in February, that's a clue that I should plant more

beds next year. On the other hand, if I ended up with peppers

that I didn't want to eat when the time came to clean out the freezer

in the spring, I might as well grow fewer this year.

Don't get too carried away, though --- if this is your first or

second year gardening, you'll want to keep your garden small and

manageable.2. Consider where the crop will grow best. I like to save the sunniest spots for crops planted in the early spring or those which will survive late into the winter. The next sunniest spots go to tomatoes and cucurbits that succumb to fungal diseases during our hot, humid summers. Herbs can go anywhere, but you'll use more if they're close to your front door. Root crops require deep, well-drained soil, so keep them out of clayey or swampy spots. If you hand water, you might want to keep moisture lovers like celery close to the hose.

3. Hunt and check until you find a

spot.

Now that I know I need 10 potato beds and that the root crop needs to

be located in the loamy third of my garden, I can start hunting through

the the garden until I find the appropriate number of beds that

haven't grown tomatoes, potatoes, peppers, or eggplants for a few

years. With a spreadsheet, you can simply search for the bed

number (or sort by bed if you have all of the information on the

same sheet) and get a list of all of the vegetables grown in each bed

since you started taking notes. Although a bit time-consuming,

this hunt and check method only takes me a couple of hours when

deciding on

spots for all of the crops in our huge spring and early summer garden.

3. Hunt and check until you find a

spot.

Now that I know I need 10 potato beds and that the root crop needs to

be located in the loamy third of my garden, I can start hunting through

the the garden until I find the appropriate number of beds that

haven't grown tomatoes, potatoes, peppers, or eggplants for a few

years. With a spreadsheet, you can simply search for the bed

number (or sort by bed if you have all of the information on the

same sheet) and get a list of all of the vegetables grown in each bed

since you started taking notes. Although a bit time-consuming,

this hunt and check method only takes me a couple of hours when

deciding on

spots for all of the crops in our huge spring and early summer garden.

If you need an incentive

to make garden planning happen in a timely

manner, you can use mine --- once I know where each vegetable will go,

I'm allowed to pore over seed catalogs. Garden porn!

I

hope you enjoyed this excerpt from Weekend

Homesteader: November. Check out the 99 cent ebook

for more information on how to store drinking water for use during

power outages, to put an entire

chicken to use in the kitchen, and to bring in cash without going to

the office.

| This post is part of our Garden Rotation lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Our urine

fertilizer really

paid off, with 31 ripe or nearly ripe fruits on our dwarf

Meyer lemon tree.

The fruits were all a bit smaller than in previous years (which means

this year's lemons were roughly the size of storebought fruit.)

If we have the same bonanza of blooms this winter, I'll thin the baby

fruits so that the tree isn't overwhelmed.

I picked the first six

lemons of the year and grated off the zest to use in baking. Our

homegrown lemon zest will go fast because Meyer lemons are a hybrid of

an orange and a lemon, so their skin is only about half strength.

I double the zest portion of any recipe when using Meyer lemon zest.

The juice is similar to

that of a storebought lemon, though a bit sweeter. One cup of

lemon juice is just enough to bake a double strength lemon meringue

pie. Too bad the dessert has to cool overnight before I can cut

and taste it.

We've already got more

flower buds on the lemon tree even as the other 80% of the fruits grow

out of their last tinge of green. Meanwhile, another dwarf citrus

has bloomed and started to set tiny fruits. In a very

un-Anna-like move, I let the labels wash off the pot, so I don't know

whether we'll be trying out homegrown navel oranges or key limes this

time next year. I guess it will be a surprise!

We established a new source

for firewood today that is higher quality at a lower price.

The rough estimate I did says

it's just under half a cord. A great deal at 50 dollars when you throw in

delivery and stacking. What makes it even better is the guy offered to

cut the next round to whatever size we need, which will be nice for our

tiny Jotul 602 woodstoves.

I've learned to put Lucy in a

"timeout" while I do short jobs like this during her walk,. If I don't

she sometimes gets distracted and shoots off into the woods dragging

her leash.

I'll be honest with you ---

this pie has very little redeeming nutritional value. On the

other hand, it is simply the best lemon meringue pie you'll ever taste

(especially if you use farm fresh eggs and homegrown

Meyer lemons.)

I'll be honest with you ---

this pie has very little redeeming nutritional value. On the

other hand, it is simply the best lemon meringue pie you'll ever taste

(especially if you use farm fresh eggs and homegrown

Meyer lemons.)

Crust:

0.5 c. flour

0.5 c. cocoa

0.25 c. sugar

0.5 tsp salt

7 tbsp butter

4 tbsp water

Put the flour, cocoa,

sugar, and salt in a food processor and blend briefly. Add the

butter in four or five pieces, and blend until the butter is broken

apart into tiny fragments. Then add the water and blend one more

time. Pat the dough into the bottom of a buttered, 9 inch round

cake pan and bake at 350 degrees for about 10 minutes, until the crust

is baked through.

Filling:

1 c. sugar (or a bit

more if you're using traditional lemons or have a sweet tooth)

6 tbsp cornstarch

0.25 tsp salt

1 cup lemon juice

6 medium egg yolks (or 5

large egg yolks)

2 tbsp butter

1.5 c. boiling water

1 tbsp grated Meyer

lemon peel (or 0.5 tbsp grated peel from a traditional lemon)

Mix the sugar,

cornstarch, and salt in a pan, then add the lemon juice, egg yolks, and

butter. (Set the egg whites aside for use in the meringue.)

Slowly pour in the boiling water, stirring constantly. Cook over

medium-high heat until the filling boils and thickens, stirring and

turning down the heat as necessary so the filling doesn't burn or

stick. Remove from the stove after 1 minute of boiling and add

the lemon peel, then pour into the baked pie crust.

Meringue:

6 medium egg whites (or

5 large egg whites)

6 tablespoons of sugar

1 tsp vanilla

Beat egg whites until thye

are stiff but not dry, then carefully stir in the sugar and

vanilla. Spoon the meringue over the top of the hot pie

filling, making sure that the meringue comes in contact with the cake

pan all the way around. Then bake at 350 degrees for 10 to 15

minutes, until the top is brown.

Beat egg whites until thye

are stiff but not dry, then carefully stir in the sugar and

vanilla. Spoon the meringue over the top of the hot pie

filling, making sure that the meringue comes in contact with the cake

pan all the way around. Then bake at 350 degrees for 10 to 15

minutes, until the top is brown.

Let your completed pie

cool in the fridge overnight before eating. I

never jump through the hoops to keep my meringue from weeping and

deflating, but the pie still disappears far too quickly. Good

thing we could make four more pies just like this from 2011's

dwarf Meyer lemon harvest!

It's been a full year since I

first started sleeping on

a memory foam matress and

it's still as super comfortable as it was the first day.

The factory smell went away

within a few days. I still took it out this summer to let some mountain

fresh air soak into it, and having it in sections made the operation

much easier to handle than a regular matress.

In my opinion this foam

technology is the best invention for someone who enjoys a good night's

sleep since the arrival of the pillow.

My low

tech oyster grain spawn experiment was a terrible

failure. Within a few days, the bags and jars were full of

various smelly molds, so I had to discard the grain onto the compost

pile.

I was shocked to see so

many "weed fungi" in the grain since I've had such good luck growing

oyster mushroom spawn on cardboard with similar lack of

sterility. I concluded there were two flaws in my grain

experiment:

- The oyster spawn I started with wasn't chomping at the bit. I harvested the mushrooms a few days before our pressure canner arrived in the mail, so I had to store the stem butts in the fridge. And the fridge has been running too cold, so the stem butts got a bit frosty. The ice didn't kill the spawn, but it did slow the oysters down so that wild molds had a chance to grow on the grain before the less vigorous than usual oyster spawn took over.

Grain may simply be too rich of

a medium for unsterile conditions. Since damp newspaper

isn't very enticing, most weed fungi can't get a toehold. But

cooked grain is delicious for all and sundry, giving the oyster

mushrooms a run for their money.

Grain may simply be too rich of

a medium for unsterile conditions. Since damp newspaper

isn't very enticing, most weed fungi can't get a toehold. But

cooked grain is delicious for all and sundry, giving the oyster

mushrooms a run for their money.

We've started a bit of

newspaper spawn with the last

few oyster mushroom stem butts of the year. Assuming

the spawn runs (which it should since I've grown oyster mushroom spawn

on cardboard before), I'll have to figure out what to expand the

cardboard spawn onto. Cardboard isn't high enough in nutrients to

keep expanding spawn on indefinitely, so I may try inoculating some

straw for a bit of indoor culture for the winter. I'll keep you

posted.

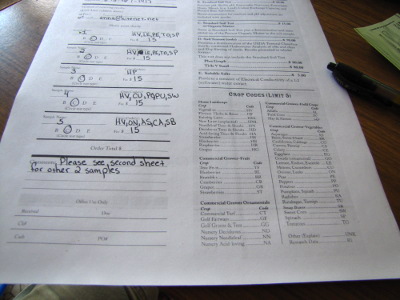

The

report from a typical soil test will tell you to

add a certain amount of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium to your

soil in order to achieve a certain yield, and might also tell you to

add

lime or sulfur to change your pH. This type of soil analysis

assumes that soil is like a checking account --- you put nutrients in

and your plants take the same amount out. Large-scale farmers

will add chemical fertilizers or --- if the fields are certified

organic --- mineral supplements and compost to supply the required

amount of each primary nutrient.

The

report from a typical soil test will tell you to

add a certain amount of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium to your

soil in order to achieve a certain yield, and might also tell you to

add

lime or sulfur to change your pH. This type of soil analysis

assumes that soil is like a checking account --- you put nutrients in

and your plants take the same amount out. Large-scale farmers

will add chemical fertilizers or --- if the fields are certified

organic --- mineral supplements and compost to supply the required

amount of each primary nutrient.

Holistic gardeners

understand that soil is

more complex, and

that the

physical environment and microorganisms work together to make nutrients

more or less available. You can compare this view of soil to a

mutual fund, with the combination of individual stocks and bonds

determining how much money is available at any given time. If

you're a real holistic gardener, you'll take the analogy one step

further and try to create soil where you're living on the interest, not

the capital.

Which is all a long way

of saying --- this lunchtime series isn't going

to show you the traditional way of interpreting your soil test

results. I'm assuming that you'll be adding half an inch to an

inch of high quality compost to your garden before each planting as a

matter

of course, so I won't mention nitrogen at all. Instead, I'll walk

you through the less well known but even more important fields on your

soil test report so that you can create a  well-rounded

soil that will

require fewer inputs every year.

well-rounded

soil that will

require fewer inputs every year.

If you don't have a soil

test for your own garden handy, this week's lunchtime series will be a

lot less fun. Check out this post

about where to send your soil tests

and be aware that fall is a great time to sample since testing labs are

less busy. I got my results via email less than a week after

putting our soil samples in the mail.

| This post is part of our Holistic Soil Test Analysis lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Sometime last year I realized

the miter saw had a place to attach a hose to

for catching saw dust. I looked around for the proper hose a few times

and then forgot about it.

I was walking by our junked

out washing machine by the barn today and noticed the drain hose was

about the same size as the exit point on the miter saw.

It was also the right length

for our current set up. A short piece of duct tape was all it took to

secure the hose to the saw.

We've now got seven hens

laying! That tiny egg in the middle is a pullet

egg, the smallest one I've ever

seen. Sometimes, a hen will produce a tiny, yolkless egg when

she's first starting to lay, so I think this picture (taken November 3)

marks the date when our last Cuckoo Marans hen came into production.

The eggs are smaller,

prettier, and less numerous than we were getting from our Golden Comets, but I hope that our

heirloom Black Australorps and Cuckoo Marans will make up for their

lower yields by eating less storebought feed and raising their own

young. Right now, we're getting around 0.475 pounds of eggs per

day (4 medium eggs) and are feeding the flock roughly 1 pound of laying

pellets. That's a feed

conversion rate of

2.1:1 and a feed cost of about $1 per dozen eggs. Not too shabby,

even if you factor in having to feed the flock for six months before

they start to lay.

Keep up the good work,

girls! We like having extra eggs to sink into lemon

meringue pies.

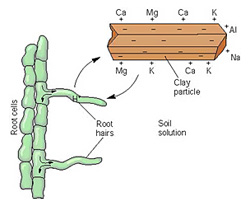

Cation exchange capacity is

the first characteristic you should consider when you get your soil

test results. Cation exchange capacity (CEC for short) is

closely tied to the amount of organic matter and clay you have in

your soil since both provide spots for positively charged ions ---

cations --- to cling to the soil. In contrast, sandy soil without

much organic matter will allow

nutrients to leach away during heavy rains.

You're throwing away your money if you add soil supplements to raise

your calcium, magnesium, or potassium levels without first increasing

your CEC so that these essential nutrients will be held in place.

Cation exchange capacity is

the first characteristic you should consider when you get your soil

test results. Cation exchange capacity (CEC for short) is

closely tied to the amount of organic matter and clay you have in

your soil since both provide spots for positively charged ions ---

cations --- to cling to the soil. In contrast, sandy soil without

much organic matter will allow

nutrients to leach away during heavy rains.

You're throwing away your money if you add soil supplements to raise

your calcium, magnesium, or potassium levels without first increasing

your CEC so that these essential nutrients will be held in place.

So what's a good

CEC? CEC can range from 0 to 100 meq/100 g, and

your goal should be to reach or exceed 20 meq/100 g. Although

clay and any kind of organic matter will help you achieve this goal,

humus is the most effective since it provides a lot more cation

binding sites per unit area. In case you're not familiar with the

distinction, humus is organic matter that has broken down to a stable

point at which it may endure for hundreds or thousands of years.

To make humus, add any kind of organic matter to your soil (compost,

mulch, or cover crops) and make sure soil

conditions are right

for earthworms, bacteria, and fungi to turn that organic matter into

high quality humus.

Let's take a look at my

CEC and organic matter test results:

| Mule (1) | Mule (2) | CP3 (3) | Back (4) | Front (5) | Mom front | Mom back | |

| CEC | 65.6 | 74.4 | 15.6 | 56 | 47.1 | 27.9 | 36.3 |

| % OM | 17 | 18.4 | 8.2 | 15 | 14.6 | 15.9 | 14.1 |

I've highlighted the one non-garden spot I sampled --- our chicken pasture, which was basically a lawn until we started letting chickens graze there this spring. I also sampled some of my Mom's soil, which has been intensively gardened for decades. Finally, the white columns are four different parts of my own vegetable garden. By comparing these three areas, you can see:

Within my garden, CEC values increase as

percent organic matter increases. Mark and I were both able to

line up our soil samples from most to least organic matter by eye, so

it would be possible to keep rough track of this information without

sending off soil samples.

Within my garden, CEC values increase as

percent organic matter increases. Mark and I were both able to

line up our soil samples from most to least organic matter by eye, so

it would be possible to keep rough track of this information without

sending off soil samples.

- Mom's CEC values are lower than mine even though her soil has just about as much organic matter. That's the difference between gardening in very clayey soil (my garden) and in a silty loam (her soil.)

- My pasture --- where I've never added compost --- is the only

area with a CEC below the 20 meq/100

g level. As I use more intensive

management techniques on this

pasture, I hope to raise the CEC without adding any soil amendments.

Most organic gardeners believe you can't have too much organic matter in your soil, but soil scientists will roll their eyes at that statement and now I understand why. If your CEC is low but your organic matter levels are high, that means you're doing something wrong and your organic matter isn't being broken down into a stable humus. Maybe you've added too much high carbon material all at once (for example, tilling wood chips into the soil) or have sprayed pesticides that killed off your soil microorganisms. That's why I recommend using CEC rather than organic matter as the most important "grade" on your holistic gardening "report card." As far as I can tell, with CEC, more is always better.

| This post is part of our Holistic Soil Test Analysis lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We're starting to feel like

the waterline

project is finally

nearing completion.

Yes...this is year 3 of

digging the ditch.

I'm not sure how many total

labor hours we've invested so far, but there were several days when it

was just too cold or too wet for ditch digging.

We knew it was a long term

project from the start, and with any luck we'll be rewarded with our

first winter of the water not freezing on really cold nights.

10

acres of pasture in need of TLC.

10

acres of pasture in need of TLC.

48 acres of Appalachian

forest.

Two springs and a pond.

A naturally

air-conditioned sinkhole.

A fallen down barn.

Two miles from our house.

A non-profit willing to

partner on our homesteading plan.

A well-established

intentional community that just might dip their finger in the pie.

Looks like a much more

interesting internship program than I'd

originally envisioned.

But dozens of wrinkles

still need to be ironed out before we can make an announcement.

So this is a

teaser. Maybe. Maybe not.

Base

Cation Saturation Ratio (BCSR) is the more complex and controversial

side of CEC. To calculate the BCSR

of your soil, first determine how many cations your soil can

hold (the CEC), then measure what percentage of that whole is

filled up by hydrogen, calcium, magnesium, potassium, and sodium.

Base

Cation Saturation Ratio (BCSR) is the more complex and controversial

side of CEC. To calculate the BCSR

of your soil, first determine how many cations your soil can

hold (the CEC), then measure what percentage of that whole is

filled up by hydrogen, calcium, magnesium, potassium, and sodium.

Over the years, various

scientists have hypothesized that there's a

perfect ratio at which your soil achieves peak health and highest crop

yields. This idea may have begun with William Albrecht in

the 1930s, and in its most recent incarnation can be found in Neal

Kinsey and Charles Walters' Hands on

Agronomy.

In the latter, the authors posit that soil  cations should exist in the

following proportions: 60-70% calcium, 10-20% magnesium, 3-5%

potassium, 1% sodium, 10-15% hydrogen, and 2-4% other cations.

cations should exist in the

following proportions: 60-70% calcium, 10-20% magnesium, 3-5%

potassium, 1% sodium, 10-15% hydrogen, and 2-4% other cations.

Others argue that what

BCSR is really measuring is the far simpler

concept of pH and that the increased crop yields organic practitioners

notice after trying to correct their cation ratios are simply due to

liming the soil. I haven't read enough to decide what I think

about this controversial topic, but I'd be curious to hear pros and

cons from folks who have read about or practiced BCSR in more depth.

Meanwhile, if you're

interested to see how your soil stacks up, you'll

need to look on your soil test for the fields "% saturation K", "%

saturation Mg", "% saturation Ca", and possibly "% acidity" and "% base

saturation." In most cases, the three first three

fields can be added together to get the last field.

Subtract the saturation of potassium, magnesium, and calcium from 100%

and you get the percent acidity (which is the percent hydrogen, and

will be 0 if your soil has a pH at or above 7.) Here's the data

from my soil samples:

| Mule (1) | Mule (2) | CP3 (3) | Back (4) | Front (5) | Mom front | Mom back | |

| % Sat. K | 4.7 | 3.8 | 7.1 | 3.7 | 6.1 | 4.5 | 3 |

| % Sat. Mg | 16.7 | 17.2 | 13.8 | 17.6 | 16.4 | 13.3 | 8.5 |

| % Sat. Ca | 78.8 | 79.2 | 64.8 | 78.8 | 77.7 | 82.3 | 88.7 |

| % Base Sat. | 100.2 | 100.2 | 85.7 | 100.1 | 100.2 | 100.1 | 100.2 |

| % Sat. H |

−0.2 | −0.2 | 14.3 | −0.1 | −0.2 | −0.1 | −0.2 |

| pH | 7.5 | 7.6 | 6 | 7.3 | 7.4 | 7 | 7.3 |

I'll write about pH tomorrow, but I included the value in my chart so you could see the obvious --- the only acidic soil (my chicken pasture, highlighted in yellow) is also the only one with a percent base saturation less than 100. More relevantly, notice that all of the samples have more calcium than magnesium. This relationship, plus the very high values of all of the cations (shown below) suggests to me that I don't need to worry about my Base Cation Saturation Ratios.

| Mule (1) | Mule (2) | CP3 (3) | Back (4) | Front (5) | Mom front | Mom back | |

| K (ppm) | 825 | 724 | 351 | 615 | 875 | 415 | 351 |

| K | Very high | Very high | Very high | Very high | Very high | Very high | Very high |

| Ca (ppm) | 7206 | 7905 | 1643 | 6801 | 5772 | 3906 | 5480 |

| Ca | Very high | Very high | Very high | Very high | Very high | Very high | Very high |

| Mg (ppm) | 930 | 1048 | 213 | 926 | 743 | 385 | 320 |

| Mg | Very high | Very high | Very high | Very high | Very high | Very high | Very high |

What would I do if my BCSR seemed to be out of whack? The first step would be to correct any CEC problems, then I could add mineral sources of the cations that seemed too low. However, it's essential to be aware of how supplements will impact your soil pH before embarking on any cation improvement project.

| This post is part of our Holistic Soil Test Analysis lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Another day of amateur

plumbing has got us a bit closer to finishing this project.

Once our nightly frosts

got down to the high 20s, quick

hoops were no longer

enough to protect our

last tomato plants.

So I ripped out the dead vines (and two gallons of green tomatoes to

pass on to the chickens) and moved the quick hoop over to our broccoli,

tatsoi, mustard, and tokyo bekana.

Thanks to my obsession

with planting greens at the end of the summer, our vegetables are still

coming almost entirely out of the garden. I've thawed out a

couple of cups of sweet corn to go in soup and a few dried squash and

mushrooms to round out our lasagna. But mostly we're eating fresh

veggies still --- mixtures of sauteed leafy greens every day, salad

with the last tommy-toes and sweet peppers still ripening inside, and

an occassional head of broccoli.

Add in the oats

and oilseed radishes

that are vibrantly growing organic matter for our soil, and the garden

still feels completely alive. I wonder how late into the winter

we can eat fresh?

I'm not going to write about

the fundamentals of pH because I figure

most of you know:

I'm not going to write about

the fundamentals of pH because I figure

most of you know:

- 7 is neutral

- 0 to 6.9 is acidic

- 7.1 to 14 is alkaline (aka basic)

To some

extent, your pH is determined by the bedrock under your soil, but

management will also impact soil pH. For example, take a look at

my test results:

| Mule (1) | Mule (2) | CP3 (3) | Back (4) | Front (5) | Mom front | Mom back | |

| pH | 7.5 | 7.6 | 6 | 7.3 | 7.4 | 7 | 7.3 |

| CEC | 65.6 | 74.4 | 15.6 | 56 | 47.1 | 27.9 | 36.3 |

Notice that the mule garden --- just a few feet away from the chicken pasture (highlighted in yellow) has alkaline soil instead of acidic soil. Soil in both spots was identical a few years ago, and I've never added lime or large amounts of wood ashes to my soil. What I have done is topdress the mule garden with compost and manure in huge quantities, which seems to have sweetened the soil (despite various sources that report compost sours soil.)

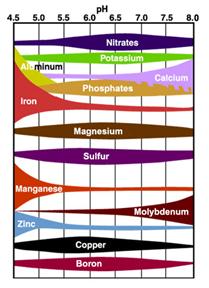

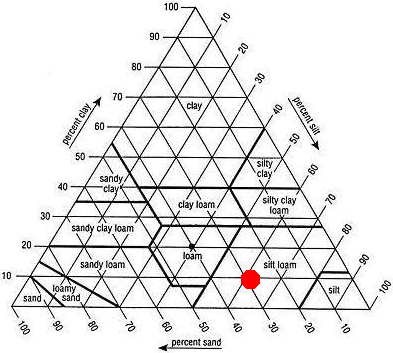

Depending

on which crops you're trying to grow, the perfect pH for most

garden plants ranges from 6 to 7 (although you'll want much more acidic

soil for blueberries.) pH is extremely important because it

determines the availability of many nutrients, as you can see in the

chart to the left. Each type of plant has evolved to deal with

specific micronutrient ranges, and a pH too high or too low can lead to

deficiencies

of some nutrients and toxic overabundances of others.

Depending

on which crops you're trying to grow, the perfect pH for most

garden plants ranges from 6 to 7 (although you'll want much more acidic

soil for blueberries.) pH is extremely important because it

determines the availability of many nutrients, as you can see in the

chart to the left. Each type of plant has evolved to deal with

specific micronutrient ranges, and a pH too high or too low can lead to

deficiencies

of some nutrients and toxic overabundances of others.If you're worried about the pH of your soil, the first thing you should do is to look at your CEC. Although a high CEC is generally a good thing, the value also means that the soil is very resistant to changes in pH. Raising the pH of my chicken pasture soil would be relatively easy due to its low CEC, but lowering the pH of my garden soil would be much tougher because of the high cation exchange capacity in that rich soil.

For now, I'm going to leave my soil pH alone, but I will probably opt to test the soil every year and keep an eye on this figure since a much higher pH could be problematic. Traditionally, soil pH is raised with lime and lowered with sulfur, but due to my high CEC, I would probably opt to apply acidic organic matter instead if I wanted to lower my garden pH. I suspect my chicken pasture will become more alkaline naturally as chicken manure and plant debris enrich the ground.

| This post is part of our Holistic Soil Test Analysis lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Last week I had an idea for a

chicken plucker that would pluck without a motor.

Tune in next week to see if

this new plucker contraption saves any time.

I was so scared that we

wouldn't have any fall crops when my plantings had

trouble germinating in the summer heat.

I was so scared that we

wouldn't have any fall crops when my plantings had

trouble germinating in the summer heat.

And it's true that my

carrot beds were only about half as populated as I would have wished.

But how can I complain

when I harvested a heaping half bushel from two small beds?

Looks like the lengthy

fall worked in my favor --- plenty of carrots despite late replanting.

What's your favorite

non-slaw recipe for raw carrot salads?

Most

problems with garden soil can be remedied with judicious application

of organic matter or other supplements, but heavy metals are more

troubling. Although humans, plants, and soil microorganisms need

small amounts of many

heavy metals, high concentrations can be toxic.

To decide whether you should be concerned, look for these possible

sources of contamination near your garden:

Most

problems with garden soil can be remedied with judicious application

of organic matter or other supplements, but heavy metals are more

troubling. Although humans, plants, and soil microorganisms need

small amounts of many

heavy metals, high concentrations can be toxic.

To decide whether you should be concerned, look for these possible

sources of contamination near your garden:

- Lead paint on old buildings

- Chemical fertilizers or pesticides

- Gas stations and mechanics' shops

- Landfills

- Industrial factories

- Runoff from streets and parking lots

- Lead paint

- Treated lumber

The table below gives

information on the seven heavy metals found in soil that are regulated

by the EPA. Of these,

lead is the most likely to be found in your soil and is the one you

should be most concerned about.

| Heavy

metal |

Natural

levels (ppm) |

Unsafe

for vegetable gardening (ppm) |

Unsafe

for children to play (ppm) |

| Arsenic (As) |

3 - 12 |

more than 50 |

more than 200 |

| Cadmium (Cd) |

0.1 - 1.0 |

more than 10 |

more than 50 |

| Copper (Cu) |

1 - 50 |

more than 200 |

more than 500 |

| Lead (Pb) |

10 - 70 |

more than 500 |

more than 1,000 |

| Nickel (Ni) |

0.5 - 50 |

more than 200 |

more than 500 |

| Selenium (Se) |

0.1 - 3.9 |

more than 50 |

more than 200 |

| Zinc (Zn) |

9 - 125 |

more than 200 |

more than 500 |

You have to ingest heavy metals to get sick, which generally means eating plants that have sucked those heavy metals up out of the soil. Luckily, plants don't tend to accumulate lead the way they do some other heavy metals, so you can garden in soil with moderately elevated lead levels as long as you don't eat much dirt. At a lead concentration of 100 ppm, you'd need to eat two teaspoonsful of soil per week to create any problem; at 300 ppm, you'd need to eat 3/4 of a teaspoonful per week.

I wasn't particularly concerned about heavy metals in my garden, but the lab I sent our samples off to tested all of the problematic metals except for arsenic and selenium as a matter of course. Mom was more worried since her front yard is right beside a busy city street and her backyard (home of her vegetable garden) isn't all that far away from car exhaust and road runoff.

| Mule (1) | Mule (2) | CP3 (3) | Back (4) | Front (5) | Mom front | Mom back | |

| Zn | 8.3 | 7.8 | 12.5 | 7.5 | 8.5 | 12.5 | 28.9 |

| Pb | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| Cd | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| Ni | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Cu | 1 | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 1 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| Est. total Pb | 37 | 38 | 40 | 37 | 37 | 64 | 108 |

| This post is part of our Holistic Soil Test Analysis lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

This is our first year

growing turnips.

The fresh leafy stalks are

delicious and the tubers have a unique spicy taste that reminds me of

my mom's garden when I was a kid.

I would call them a good

addition to any garden, especially when you factor in how easy they are

to store for the winter.

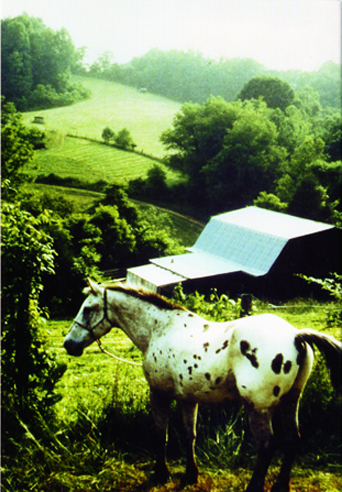

A pair of our favorite local

friends are retiring and moving to town. We're heart-broken...but

maybe one of you would like to step into their shoes and be our new

neighbor?

A pair of our favorite local

friends are retiring and moving to town. We're heart-broken...but

maybe one of you would like to step into their shoes and be our new

neighbor?

This well established

farm is located just two miles from our house. I'll let Dick tell

you about it in his own words:

near Dungannon VA

Limited offering by

Anne Leibig and Dick Austin

This 95 acre mountain

farm, overlooking

the Clinch

River has been managed organically, with horse power, for

more than 30 years (berries, peppers, range chickens, maple syrup),

with extensive hardwood forests including stands of sugar maples (+

syrup evaporator), 4+ acres of tillable land, 7+ acres of pasture/hay

land, large modern barn with 6 horse stalls, loft and

work-room. (All figures are approximate.)

Forest

management certified by

SmartWood.

The property is protected by a conservation easement with

The Nature Conservancy which has designated

the Clinch River

watershed one of America’s “Last Great Places” because of its

unusual biological diversity.

Our home comprises two

adjacent

buildings with scenic outlooks and privacy (no other homes in sight).

There are 2,100 square feet with three bedrooms, two baths, large

dining room, two living rooms, a study, a modern kitchen and pantry;

plus a distinctive curved porch (500 sq.ft.), and a deck (550 sq.ft.)

with Jacuzzi (needs plumbing repairs), and a dog run. Original house

dates from 1916 with porch from 1930, plus modern renovations and

additions. Century-old logs and hand-made bricks from the first

farmhouse are incorporated in the modern, passive-solar addition.

Both buildings have central heat and air conditioning. There is also

a wood stove in the main house.

For forty years Anne and

Dick have

engaged with the surrounding community and natural environment. In an

effort to attract new owners who may continue this tradition, we are

making a special offer to friends and to those recommended by our

friends, at a price lower than we would ask on the commercial market.

Please contact us for details, and to arrange a visit to this home

and farm of rare beauty.

For forty years Anne and

Dick have

engaged with the surrounding community and natural environment. In an

effort to attract new owners who may continue this tradition, we are

making a special offer to friends and to those recommended by our

friends, at a price lower than we would ask on the commercial market.

Please contact us for details, and to arrange a visit to this home

and farm of rare beauty.

The farm address is

2895 Sinking Creek

Hwy., Dungannon, VA, 24245

Farm phone is

276/467-2437.

You may E-mail Anne

Leibig at

abjl@mounet.com,

or call her

cell phone, 276/690-0814.

E-mail Dick

Austin at

chestnut@mounet.com.

I've been trying to take a

picture of our curled

toe chicken's feet for months now, but she's hard to keep up with.

This plucker

finger close up is the best yet.

This image illustrates how

her corrective

tapecotomy came out.

It's hard to pick her out of

a crowd. She doesn't seem to have any trouble walking, but I think bug

and worm scratching may be impaired due to her smaller size compared to

the others.

Mark's got a talent for

tinkering. He's invented a POOP-free chicken waterer that thousands of flocks

around the world enjoy. His deer deterrents keep my garden happy.

And he's always coming up with new device to make farm life

easier. But his best invention, by far, is weekends.

Readers, don't worry ---

Mark won't be patenting weekends anytime soon, so you too can enjoy his

invention. Just pretend work doesn't exist and ignore the weeds

in the garden and the apples that need to be preserved. Then

light a cheery fire, read a book, hang out with people you care about,

and enjoy yourself. You'll be glad you did.

It's been a full year since

we installed

this experimental box to

prevent the portion of our non-potable water line that goes from the tank to

the ground from freezing.

The line did freeze up a few

times in that year because the end that goes into the trailer still

needs attention. The frozen time was far less than the previous year

and it seemed to thaw out much faster.

I'm going to be writing

like crazy

over the next few weeks, so lunchtime series may be a bit sparse.

That means it's your chance to write in rather than just reading!

I'm going to be writing

like crazy

over the next few weeks, so lunchtime series may be a bit sparse.

That means it's your chance to write in rather than just reading!

To date, Weekend

Homesteader is chock full of photos of me

and Mark (and Huckleberry and Lucy), and it could use some

diversification. As you pored over my monthly ebooks, did you

say, "Hey, I have a better system than that in operation in my

garden!" Do you have some great photos of a kill mulch, a

rain barrel, a homemade worm bin, a family canning session, or anything

else in the ebook

series? Action photos with people in them (or even chickens

or dogs) get bonus points.

If so, email your photos

(one per email please) with the legalese at the end of this post to anna@kitenet.net.

A short writeup to explain your photos is great, but not

mandatory. If I choose to include your photo (and/or writeup) in

my book, I'll credit you right there in black and white and will send

you a Walden

Effect t-shirt.

Please include this text

in your email to cover my publisher's butt:

I'm looking forward to

seeing some ingenious designs!

Sometimes these barbed

connectors can be a major struggle to remove once they've been pushed

in all the way.

My new trick is to use a

coping saw to cut them free when brute force fails.

Do you have a favorite

age? I definitely do --- 6 to 10 weeks old. Mature enough

that I can stop worrying about heat and predators and frisky enough to find a

lot of their own food.

Do you have a favorite

age? I definitely do --- 6 to 10 weeks old. Mature enough

that I can stop worrying about heat and predators and frisky enough to find a

lot of their own food.

(You know we're talking

about broiler chickens here, right?)

After 10 weeks, I start

stressing again. I've yet to plan ahead well enough that I have

sufficient pasture for these rapidly growing birds, so I start hunting

down treats to keep their diet well-rounded. The pullets and

cockerels have to be shut out of the garden at that age because they

start to scratch mulch on top of my young garlic plants, and 11 week

old broilers are so long-legged that they're willing to walk the long

way round to get to those garden beds.

And then there's the deep

bedding. I

always seem to let the last few weeks get away from me, and the

increased volume of manure mats on the surface of the leaves or

straw. Our final batch of Light Sussex have been the worst in

that respect since they still want to roost in a huddle in

the corner, which means they concentrate their manure in one spot and

then sit in it. Yuck. I was beyond thrilled when Mom

brought me some more leaves to alleviate the manure pileup, but next

year I've got to plan ahead so I have enough high carbon bedding to top

off the coop floor every other day for the last two weeks of broiler

time.

And then there's the deep

bedding. I

always seem to let the last few weeks get away from me, and the

increased volume of manure mats on the surface of the leaves or

straw. Our final batch of Light Sussex have been the worst in

that respect since they still want to roost in a huddle in

the corner, which means they concentrate their manure in one spot and

then sit in it. Yuck. I was beyond thrilled when Mom

brought me some more leaves to alleviate the manure pileup, but next

year I've got to plan ahead so I have enough high carbon bedding to top

off the coop floor every other day for the last two weeks of broiler

time.

Which is all a long way

of saying that even though the Light Sussex have been my favorite flock

of the year, I am totally ready to slit their throats and put them in

the freezer. We processed the first four Monday --- six more to

go!

Every good homesteader

has a hundred or so quart size jars. Jars take up the same space

whether they are full of beautiful fruits and veggies or empty.

Every good homesteader

has a hundred or so quart size jars. Jars take up the same space

whether they are full of beautiful fruits and veggies or empty.

A great way to store water is in those jars once you use your precious

preserves. Water and preserves need the same storage requirements

--- dark, cool, rotated often --- so you can put those shelves to use

in the off season to store drinking water for emergency power outages.

Do

you have a great idea to share with Weekend Homesteaders? Enter

your photo and short writeup and win a t-shirt!

This low

tech way of plucking a chicken involves pulling the bird through

the plucker box a few times to get the majority of feathers.

It still requires some hand

plucking, but Anna seems to feel like it cuts the time needed for this

chore in half.

Maybe I can improve the

design a bit for version 2.0 by making the walls adjustable?

I needed some good visuals

for my tree-planting chapter of Weekend Homesteader. Oh, how sad, I had to

order a few more fruit trees! (Don't throw me in that briar

patch!)

I needed some good visuals

for my tree-planting chapter of Weekend Homesteader. Oh, how sad, I had to

order a few more fruit trees! (Don't throw me in that briar

patch!)

We settled on two Asian

Persimmons (Ichi-Ki-Kei-Jeiro and Saijo) that are supposed to be

hardy enough to withstand our winters, along with a Starking Delicious

Pear. All are now installed in current or future chicken pasture

areas. The persimmons are diminutive enough that they could fit

in our smaller pastures while the pear is (hopefully) willing to deal

with somewhat waterlogged, heavy clay down in the floodplain. The

long term goal is to give

the chickens some protective cover while producing late season

fruit that they and we will share.

I love planting

experimental trees more than (almost) anything, but I do have a tough

time watching the ones that die. Last year's hardy almonds were a failed experiment ---

I thought they might have trouble fruiting because of being at the edge

of their hardiness  range, but what they had

trouble with was being eaten alive by Japanese beetles. I also

lost one Carpathian Walnut

because of planting it in the woods and forgetting about it (although

I'm happy to report that its sister tree and the transplanted Chinese

chestnut in the same area survived my neglect.) But all of the

rest of last year's perennials are thriving and I figure losing two

trees out of eleven isn't terrible when so few of the varieties are

tried and true.

(One of the almonds is clinging to life for another year.)

range, but what they had

trouble with was being eaten alive by Japanese beetles. I also

lost one Carpathian Walnut

because of planting it in the woods and forgetting about it (although

I'm happy to report that its sister tree and the transplanted Chinese

chestnut in the same area survived my neglect.) But all of the

rest of last year's perennials are thriving and I figure losing two

trees out of eleven isn't terrible when so few of the varieties are

tried and true.

(One of the almonds is clinging to life for another year.)

Let's hope 2015 is the

year of the persimmon and pear!

Have you built a chicken coop or tractor so