archives for 10/2011

The

last of the bedding is clean and dry.

The

last of the bedding is clean and dry.

Our lunchtime

entertainment is migrating warblers stopping for a snack in the peach

tree.

Lightning bugs in the

air have been replaced by glow worms on the ground.

We ate the last

watermelons and sweet corn this week and are enjoying the last bed of

bush beans.

My planting calendar has

only one item left.

Temperatures are finally

cooling down to the normal range and there's a chance of frost tonight.

Farewell, summer!

The first frost scramble was

in full swing yesterday as we were busy bringing in some of the last

few bits of harvest that will need to finish growing up inside.

Putting a quick

hoop over a few of the late tomato plants is a new experiment for

us. Stay tuned to see if it works in squeezing out yet another basket

of yumminess.

It was a good summer for our

dwarf Meyer lemon tree. Bringing her in is starting to feel like a

substantial end of summer ritual for us.

Mark and I thoroughly enjoyed

attending the Organic

Grower's School in Asheville this spring, but we hadn't

planned to seek out any similar experiences. When a flyer for the

Acres USA Conference showed up in our mailbox, I

was all set to shred it for mulch, but Mark noticed that the conference

was being held just an hour away from his Mom's house (and she is

overdue for a visit.)

Mark and I thoroughly enjoyed

attending the Organic

Grower's School in Asheville this spring, but we hadn't

planned to seek out any similar experiences. When a flyer for the

Acres USA Conference showed up in our mailbox, I

was all set to shred it for mulch, but Mark noticed that the conference

was being held just an hour away from his Mom's house (and she is

overdue for a visit.)

I was still dubious

until I noticed that Harvey Ussery would be presenting. Even

though Harvey Ussery isn't very well known, I consider him the best

homesteading author writing today. I've just about given up on

magazines, but every now and then I'll open Mother Earth News or

Backyard Poultry Magazine and flip through the table of contents.

My eye zips past repeats of the same old information and then

invariably lands on one article worth reading. Every single time

this has happened for the last two years, the author of the article has

been Harvey Ussery.

"That's nice," said Mark

politely when I enthused about the possibility of hearing Harvey Ussery

speak. "Wait, what does that say?" I'd turned the page to

the preconferences, and Mark was suddenly riveted.

"Radionics?! That's the first time I've ever seen a course about

radionics at a mainstream conference!" Suddenly interested, Mark

reminded me that the accountant we visited this spring chastised us for

not writing as much as we should off on our taxes --- this conference

would definitely count as a tax deduction.

"That's nice," said Mark

politely when I enthused about the possibility of hearing Harvey Ussery

speak. "Wait, what does that say?" I'd turned the page to

the preconferences, and Mark was suddenly riveted.

"Radionics?! That's the first time I've ever seen a course about

radionics at a mainstream conference!" Suddenly interested, Mark

reminded me that the accountant we visited this spring chastised us for

not writing as much as we should off on our taxes --- this conference

would definitely count as a tax deduction.

So who else will be

attending? For those of you with more mainstream tastes, the

conference has Joel Salatin, Francis Thicke, and Gray Graham as keynote

speakers and a huge array of lecturers and workshop leaders.

They'll be showing the films Farmageddon, American Meat, and Queen of

the Sun, and attendees will get a chance to pick the brains of

"world-class teachers/consultants/farmers" at consulting halls.

Maybe we'll see you there?

There were two hitchhikers on

our Meyer

lemon tree we brought in on Friday.

They seemed cute together on

Saturday and made me feel all warm inside.

Now there's just one. I'll

let her out tomorrow after she's had a chance to digest the weekend.

Researchers in Beaver, West

Virginia, have been exploring forest

pastures (aka

silvopastures) for over a decade. Since I've been playing around

with reinventing the wheel for the last couple of years, I was

intrigued to see solid data from a location just two and a half hours

from our farm.

Researchers in Beaver, West

Virginia, have been exploring forest

pastures (aka

silvopastures) for over a decade. Since I've been playing around

with reinventing the wheel for the last couple of years, I was

intrigued to see solid data from a location just two and a half hours

from our farm.

Traditionally,

large-scale experimenters planted trees in existing pastures to create

silvopastures, but Charles Feldhake, Jim Neel, and the other

researchers at the Appalachian

Farming Systems Research Center tried a different

tack. They thinned out 70 year old forest dominated by white oak

until the combined diameter at breast height of the remaining trees was

about 50 to 65 feet per acre. For those of you who don't spend

your time wrapping tape measurers around tree trunks, that would

require removing up to 75% of the trees --- you can get an idea of the

final tree cover from the photos included in this post.

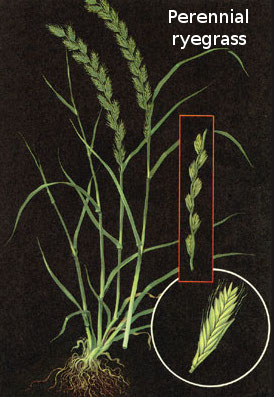

The next step was pasture

establishment. After soil testing, the scientists spread the

appropriate amount of lime (to raise the pH) and chemical fertilizer on

the soil surface, along with seeds for orchardgrass, perennial

ryegrass, and white clover. Then they turned in the sheep.

The next step was pasture

establishment. After soil testing, the scientists spread the

appropriate amount of lime (to raise the pH) and chemical fertilizer on

the soil surface, along with seeds for orchardgrass, perennial

ryegrass, and white clover. Then they turned in the sheep.

Although I wrote last

week that sheep are maintainer

livestock, Feldhake

and company used their woolly grazers as colonizers, noting that the sheep not

only ate up the undergrowth but also mashed the seeds and soil

amendments into the top layer of soil. Once pasture seeds started

to sprout, the sheep were removed to let the grass and clover establish

themselves, but they were later turned back in to rotationally graze

the new pastures.

Here are some

comparisons between the silvopastures and neighboring non-treed

pastures:

Silvopastures

produce half as much forage. So you'll need to devote

twice the area to graze the same number of sheep if you add

trees. That disadvantage is offset by the possibility of using

the trees either as timber or to produce fruit or nuts for humans

and/or livestock. (For example, if you were grazing pigs under

white oaks, the acorns might make up for the slower growth of the

pasture grasses.) Plus, forested land is more environmentally

friendly in our area than open pastures.

Silvopastures

produce half as much forage. So you'll need to devote

twice the area to graze the same number of sheep if you add

trees. That disadvantage is offset by the possibility of using

the trees either as timber or to produce fruit or nuts for humans

and/or livestock. (For example, if you were grazing pigs under

white oaks, the acorns might make up for the slower growth of the

pasture grasses.) Plus, forested land is more environmentally

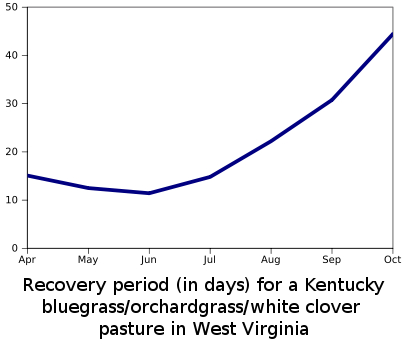

friendly in our area than open pastures.- Silvopastures have a different seasonal cycle. Under the oak trees in the Beaver study area, spring regrowth was three weeks slower than in open pasture. The scientists hypothesized that rot-resistant oak leaves shaded and stunted the pasture plants in the fall and that tree species with fewer tannins in their leaves wouldn't show the same spring pasture retardation. Feldhake noted that the presence of a tree canopy seems to have a temperature mitigating effect, so fall frosts come later under the trees --- perhaps a forest pasture can extend the grazing season later into the winter?

- The pasture plants growing in the shade of trees are nutritionally different than the same plants living in the open. On the plus side, shaded plants tend to have more protein, but that goes hand in hand with excess nitrates that can potentially harm or kill ruminants.

So what are the take-home

messages for those of us interested in creating forest pasture of our

own?

So what are the take-home

messages for those of us interested in creating forest pasture of our

own?

Several other studies

have suggested that a savannah-like environment, with scattered trees

over a grassy sward, is the most biologically productive combination of

trees and undergrowth. In other words --- space those trees out

rather than letting them shade the whole forest floor!

Since you're losing

about half of your sunlight to the tree canopy, it becomes very

important for the trees to have a purpose in a silvopasture

system. For chickens, that means planting mulberries, persimmons,

and other fruit trees rather than letting the flock graze under

whatever happens to be present. For pigs, you might focus on

chestnuts, oaks, and honey-locusts too. Time to practice what I

preach and replace those box-elders with fruit trees!

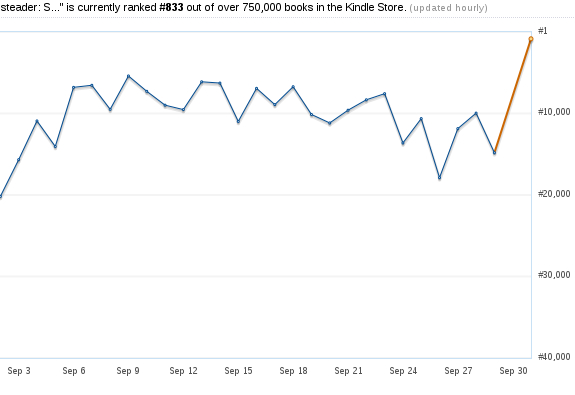

Saturday morning, I was

stunned to see that Weekend

Homesteader: September

was ranked as #833 in Amazon's kindle store. I never thought I'd

break #1,000 and I know I owe the ebook's success to our loyal readers.

I wish I could give a package of my

favorite seeds

to each of you, but unfortunately there's only enough for one.

Congratulations, April,

for being our seed winner! Drop an email to

anna@kitenet.net with your

mailing address and I'll put your seeds in

the mail tomorrow. And thank you to everyone else for helping my

ebooks see the light of day!

This is the first year

that we've wholeheartedly experimented with chickens, and I learned a

huge amount...as well as figuring out how much more we have to

learn. We began the year with four old hens and a rooster, ate

the rooster when he started attacking me, progressed through four sets

of chicks of varying breeds, and will go into winter with an entirely

new flock of ten hens and one or two roosters.

In the process, I've

started to wrap my mind about the best ways to incubate, brood, and

pasture chickens. I've consumed chicken-related books and

websites, kept lots of notes on how the chickens acted on the ground,

and generally pondered chickens at great length. Be sure to check

back at lunchtime for the next two weeks to read about my experiments!

This post is part of our 2011 Chicken Experiments lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

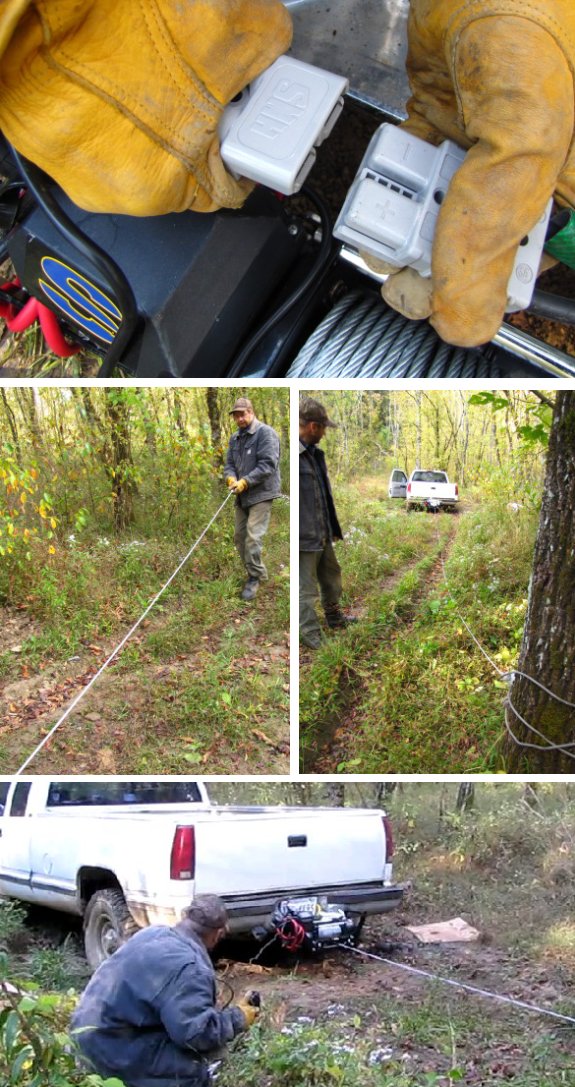

We've decided against making

a portable

Super Winch extension cord and instead went with an auxiliary

wiring harness that was custom made for portable winch applications

like this.

The positive strand is 25

feet long so it will reach the battery from the bumper. The negative

side is only 4 feet and will need to attach to the frame near the rear.

Both strands are 2 gauge with a heavy duty quck connector crimped at

the end.

I started the job of routing

the positive wire underneath the truck when I wimped out due to the

ground being cold and wet. Maybe it'll be warmer tomorrow?

The first frost of fall 2011

was gentle (albeit early --- October 3.) It barely nipped the

basil and summer squash and I suspect even our uncovered tomatoes might

keep right on ripening.

The first frost of fall 2011

was gentle (albeit early --- October 3.) It barely nipped the

basil and summer squash and I suspect even our uncovered tomatoes might

keep right on ripening.

The sudden cold was a

shock to our systems, though. I cleaned out the wood stove nook

and lit our first little fire. I just burnt five or six sticks of

leftover kindling, but the wood was enough to take the chill off until

the sun came in our south-facing window, and to remind me how much I

love our efficient

wood stove!

The frost is our cue to

get ready for our first little "staycation" of the year, slated to

begin October 11. We realized after last winter's trip that the

vacation had been too long and that we started missing home pretty

fast, so we're opting to take two half weeks off at home this winter

instead. I've always loved the idea of a staycation, but didn't

trust myself not to work right through them. Let's see if Mark

can keep me honest so that I get the same deep relaxation during a

staycation as during a cruise.

The frost is our cue to

get ready for our first little "staycation" of the year, slated to

begin October 11. We realized after last winter's trip that the

vacation had been too long and that we started missing home pretty

fast, so we're opting to take two half weeks off at home this winter

instead. I've always loved the idea of a staycation, but didn't

trust myself not to work right through them. Let's see if Mark

can keep me honest so that I get the same deep relaxation during a

staycation as during a cruise.

If you're starting from

scratch with pasturing chickens the way we were this year, you'll

probably be asking a slew of questions. Your first decision will

be between chicken

tractors and day range --- we chose the latter so I'll focus on

rotational pastures in this post. Here are some of the questions

I wish I'd known the answers to twelve months ago.

If you're starting from

scratch with pasturing chickens the way we were this year, you'll

probably be asking a slew of questions. Your first decision will

be between chicken

tractors and day range --- we chose the latter so I'll focus on

rotational pastures in this post. Here are some of the questions

I wish I'd known the answers to twelve months ago.

What

kind of fencing should I use?

Your second decision is

between permanent and temporary pastures. The

former are harder to build in the short run and are more expensive per

square foot, but are easier to use in the long run. If you're

raising 50 or fewer chickens in your backyard, I'd recommend permanent

fences.

For happy chickens who

don't live in a predator hotspot, a roll of

five foot chicken wire strung between t-posts about 15 feet apart with

a few old boards or logs tacking down the  bottom will be

sufficient. Here's

my theory on what you should do if your chickens try to escape. A well-trained

dog is our solution

to predation.

bottom will be

sufficient. Here's

my theory on what you should do if your chickens try to escape. A well-trained

dog is our solution

to predation.

If you'd prefer

temporary fencing, the traditional choice is electrified netting.

I wrote about why

electrified netting is often a poor choice for the backyard and what I

use instead here.

What

does a permanent, rotational grazing system look like for chickens?

A chicken coop sits at

the center, surrounded by several small pastures (often called

paddocks.) The chickens spend the night in the coop (and go

inside whenever they want to lay an egg), then exit through a small pophole into the pasture of your

choice. When you want to move the chickens to a new pasture, it's

as simple as closing the old  pophole while the chickens

are all sound asleep and then opening a pophole into the next pasture.

pophole while the chickens

are all sound asleep and then opening a pophole into the next pasture.

One of my favorite parts

of this system is how easy it is to move chickens to a new patch of

ground. I've seen several temporary fencing or chicken tractoring

systems where people get lazy and let the chickens sit on the same

patch of ground far too long because it's just a pain in the butt to

move them. You won't have that problem here.

How

much space do I need to devote to chicken pastures?

Mainstream pastured

poultry producers will tell you that broilers need 10 square feet of

pasture per bird per week (or a total of 40 square feet for the four

weeks the birds typically live on pasture.) You should consider

that the bare minimum required for breeds that don't forage much, with

the chickens housed in tractors that are moved daily so that the flock

can't scratch the ground bare.

In my permanent,

rotational pastures with keen foragers, I see pasture degradation when

I have fewer than 270 square feet per bird during the summer. I

suspect I'd need at least twice that much space to keep the ground from

turning into mud in the winter.

Keep in mind that the

amount of space your chickens need will depend on a variety of factors, including climate, season,

chicken breed and age, and pasture quality. If in doubt, give

your chickens as much space as you can --- the more they can roam, the

more they will supplement storebought feed with insects caught on the

wing. You can tell that your flock doesn't have enough space when

bare spots turn up amid the grass, you can see poop on the ground, and

the pasture starts to smell and fill with flies.

Keep in mind that the

amount of space your chickens need will depend on a variety of factors, including climate, season,

chicken breed and age, and pasture quality. If in doubt, give

your chickens as much space as you can --- the more they can roam, the

more they will supplement storebought feed with insects caught on the

wing. You can tell that your flock doesn't have enough space when

bare spots turn up amid the grass, you can see poop on the ground, and

the pasture starts to smell and fill with flies.

How

many pastures do I need?

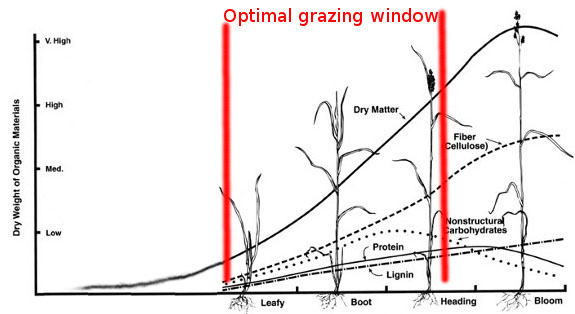

What you're really

asking here is --- how long should I leave my chickens in one paddock

and how long should I let that paddock sit fallow before I move

chickens back into it? The answer will depend on whether you're

just raising broilers when pasture plants are growing fast or are

keeping laying hens year round. Your type and quality of pasture

plants will also affect the answer.

Once again, it's helpful to

look at the bare minimum, which is four pastures for summer use or six

pastures for year round use. If you size each pasture so that

your flock eats the tender growth in about a week, you'll be able to

rotate the chickens through three other pastures  before turning them back into

the first one in a four pasture system. Three weeks off is

sufficient for plants to rebound as long as they

weren't overgrazed, the pasture got enough rain, and it's not too cold

or hot for growth. Click

here to read more about pasture rotation.

before turning them back into

the first one in a four pasture system. Three weeks off is

sufficient for plants to rebound as long as they

weren't overgrazed, the pasture got enough rain, and it's not too cold

or hot for growth. Click

here to read more about pasture rotation.

What's

the best shape for a pasture?

The perfect chicken

pasture is square, but you'll often have to work around obstructions

and use a wiggly or rectangular shape. If you can help it, don't

make your pasture more than twice as long as it is wide or chickens

will tend to hang out near the coop and not explore the far

reaches. A sharp bend in the pasture will have the same

effect. You can counteract this behavior to some extend by

locating a compost pile or chicken waterer at the far end of the

pasture.

Does the

pasture location matter?

Does the

pasture location matter?

Yes. In the

winter, chickens will do best if their pasture is in the sunniest

possible location, beyond the shade of hills, buildings, or evergreen

trees. In the summer, the reverse is true --- chickens like some

sunny spots but will enjoy hanging out in shaded corners and under

bushes. You can either build separate pastures for winter and

summer or can create the best of both worlds by using deciduous trees

to shade certain parts of your summer pasture while letting in the

winter sun.

What's

the best type of pasture?

Chickens

enjoy succulent, young growth, which means that tall

plants like ragweed are the worst choice for your pasture. The

best types of groundcover for year-round growth tend to be perennial

grasses and legumes like bluegrass, clover, etc. You may want

to plant paddocks of annual

grains and legumes to extend the pasture season into the cold

weather. Trees and shrubs can be useful additions if they produce

fruits that chickens enjoy, but there's a tradeoff since the perennials

will also shade out the undergrowth even when the trees aren't bearing.

Is

one time of the year best for raising broilers?

Once you get a feel for the

peak production times for your individual pasture, you'll know when it

can handle an influx of extra birds. In regions like ours where

pastures are dominated by cool season grasses, those peak periods occur

in mid spring to mid summer and again in early fall. Putting one

set of broilers on pasture in May and pasturing another in September

would use our pastures to best effect.

Once you get a feel for the

peak production times for your individual pasture, you'll know when it

can handle an influx of extra birds. In regions like ours where

pastures are dominated by cool season grasses, those peak periods occur

in mid spring to mid summer and again in early fall. Putting one

set of broilers on pasture in May and pasturing another in September

would use our pastures to best effect.

Should I

include other animals in my pastures?

Joel

Salatin's model uses

grazing animals like cows, sheep, or goats to keep the tall weeds down

and the chicken-friendly plants growing as fast as possible. Miniature

livestock are an

option for the backyard, but an alternative is to simply mow your

pasture a few times a year.

and the chicken-friendly plants growing as fast as possible. Miniature

livestock are an

option for the backyard, but an alternative is to simply mow your

pasture a few times a year.

Can I

use chicken pastures to keep deer out of the garden?

Chicken moats are a permaculture concept

that utilize linear chicken pastures on the perimeter of a garden to

deter deer. Even though the deer can jump over a five foot fence,

they don't like to be confined and will hesitate to jump two in

succession. Our deer moats have worked very well...too bad they

don't completely encircle our tender garden plants.

I'm sure I'll have

another long list of mistakes to shun next year, but that's the fun of

pasturing!

This post is part of our 2011 Chicken Experiments lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: This post is part of our 2011 Chicken Experiments lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

Thanks for all the helpful

wiring comments. We especially liked the old water hose idea. That

extra layer of protection feels solid and secure.

I've

been waiting with baited breath for our fruit trees to mature enough to

bear, and it seems like every one has had a surprise in store for

me. This year it was the Kieffer Pear that set two fruits a year

earlier than expected.

I watched those

beautiful green pears

swell all summer, and at last saw that their lenticels had turned

brown, meaning that the fruit was fully developed. As with all

storage pears, you have to pick the fruits and then let them ripen for

a few more weeks inside, so again I waited. Finally, the day of

the taste test came. I sliced the pear into quarters and Mark and

I each took a nibble...and just about spit it out. Unfortunately,

the pear I'd been waiting on for the last four years has gritty fruit

with very little taste --- a pear that's best canned, reports the

internet.

Looking up the pear's sister

tree --- Orient --- turned up the fact that

these two varieties are often planted for their extreme disease

resistance,

but that their fruit is extremely unexceptional. I bought the duo

because they were cheap and I wanted a pear tree, but now I

wish I'd waited a year until I could save the cash for a tree that was

both disease resistant and flavorful. We put in an order for

Starking Delicious Pear (reported to be "Bartlett-quality" and

"virtually blight-free"), so hopefully in another four years, we'll be

tasting a more flavorful fruit.

Looking up the pear's sister

tree --- Orient --- turned up the fact that

these two varieties are often planted for their extreme disease

resistance,

but that their fruit is extremely unexceptional. I bought the duo

because they were cheap and I wanted a pear tree, but now I

wish I'd waited a year until I could save the cash for a tree that was

both disease resistant and flavorful. We put in an order for

Starking Delicious Pear (reported to be "Bartlett-quality" and

"virtually blight-free"), so hopefully in another four years, we'll be

tasting a more flavorful fruit.

Meanwhile, I plan to

graft some tastier varieties onto our existing pear trees. More

on that project in a later post.

What

do chickens eat on pasture? Invertebrates are their favorites,

but I'm still working out methods of attracting tasty insects and worms

for the flock to consume. (Keeping a compost pile in each pasture

is a good start.) Meanwhile, I did some research and then kept

notes on the plants our chickens enjoyed.

What

do chickens eat on pasture? Invertebrates are their favorites,

but I'm still working out methods of attracting tasty insects and worms

for the flock to consume. (Keeping a compost pile in each pasture

is a good start.) Meanwhile, I did some research and then kept

notes on the plants our chickens enjoyed.

Traditional

chicken pastures

tend to be either unimproved pastures (ie whatever survives repeated

close grazing), or mixtures of legumes (white clover and subclovers),

grasses (orchardgrass, perennial

ryegrass, tall

fescue, and annual ryegrass), and weeds. Some  farmers plant annuals like

oats or rye in certain plots for winter forage.

farmers plant annuals like

oats or rye in certain plots for winter forage.

Our pastures are

currently a mix of native woodland and whatever popped up when we mowed

other reclaimed woods for a few years. That gave me a chance to

watch our chickens explore quite a range of habitats, and I

discovered that they showed seasonal preferences for plant foods.

In the winter and early

spring, most plants are dormant, but our flock still found some tasty

wild food. Ground

cherry fruits

hung on the plants until February and were thoroughly enjoyed, even

though the chickens had to find a way through the papery husks. Chickweed leaves,

of course, were a huge hit --- whenever we turned chickens into

fresh pasture in early spring, they ran straight to the chickweed

before eating anything else. The chickens were willing to eat tender

young grass leaves,

but only after all of the tastier

In the winter and early

spring, most plants are dormant, but our flock still found some tasty

wild food. Ground

cherry fruits

hung on the plants until February and were thoroughly enjoyed, even

though the chickens had to find a way through the papery husks. Chickweed leaves,

of course, were a huge hit --- whenever we turned chickens into

fresh pasture in early spring, they ran straight to the chickweed

before eating anything else. The chickens were willing to eat tender

young grass leaves,

but only after all of the tastier  plants were gone.

plants were gone.

As spring advanced, our

chickens started chowing down on clover and fleabane

leaves.

Although I'd read that most people plant white clover in their chicken

pastures, red clover

seemed to be

preferred by our flock. Our rooster fell in love with violet

flowers, but no

one else seemed interested.

Chickweed was past its prime

in mid April (at least according to our snobbish chickens), so they

turned to small-flowered crowfoot seeds.

Chickweed was still their second favorite food, though, and they also

enjoyed other tender young plants for the rest of the spring period.

Chickweed was still their second favorite food, though, and they also

enjoyed other tender young plants for the rest of the spring period.

Come late May, the pastures were changing --- the "weeds" were starting

to get too woody for chicken digestion and the grasses were going to

seed. Now the flock enjoyed a smorgasbord of grass seed heads, sedge seed heads, cranesbill seeds, clover leaves, and

violet leaves.

And then we hit the summer lull. Drier weather slowed down the

tender new growth chickens crave, big weeds shaded the ground, and

suddenly grass leaves were a favorite because they were the only

non-lignified plants within reach. Our one patch of warm

season grass

was especially hard hit since it kept producing throughout the

summer. In contrast to our traditional pastures, the forested

pasture became a virtual desert from a chicken's point of view.

In late August, Mark fenced in a new forest pasture. In this

previously fallow land, there was still fresh growth on the forest

floor, and our flock enjoyed Japanese

stiltgrass leaves and various seed heads...for two days.

Then they asked to go back to the perennial grasses.

As a side note, I should mention the

foods preferred by our chicks, since they were quite different

than those consumed by adult chickens. Chicks have tiny beaks, so

they can't eat  anything

large and they can't break anything tough up into bits small enough to

eat (without a hen's help.) Our spring batch ate everything in

sight since the greenery was all so succulent, but our fall chicks had

more trouble finding tasty food they could actually eat. Tick

trefoil flowers and sourgrass

flowers and young seed pods fit the bill even at the beginning

of September, and then the chicks branched out into eating sourgrass leaves and clover leaves

as they got a bit older.

anything

large and they can't break anything tough up into bits small enough to

eat (without a hen's help.) Our spring batch ate everything in

sight since the greenery was all so succulent, but our fall chicks had

more trouble finding tasty food they could actually eat. Tick

trefoil flowers and sourgrass

flowers and young seed pods fit the bill even at the beginning

of September, and then the chicks branched out into eating sourgrass leaves and clover leaves

as they got a bit older.

Finally, I should mention that I tried out planting various annuals in

the pastures throughout the year. In the long run, I've decided

that planting annuals only makes sense to give the chickens fresh food

during the summer and winter lulls --- otherwise, leaving the planted

ground chicken-free for a few weeks or months as the cultivated crops

get established just slows down rotation speeds and does the pastures

more harm than good. And it turns out that our flock only really

enjoyed one cultivated plant I tried --- butternut squash.

The vines were able to survive moderate chicken scratching, and the

fruits were happily hollowed out by our hungry chickens.

more harm than good. And it turns out that our flock only really

enjoyed one cultivated plant I tried --- butternut squash.

The vines were able to survive moderate chicken scratching, and the

fruits were happily hollowed out by our hungry chickens.

I went into the year thinking that I'd see what our chickens' favorite

foods were and then plant pastures in just those plants. However,

as the year progressed, I started to realize that I need to think of

the pasture as an ecosystem rather than as a collection of

plants. Next year, I'll be experimenting with traditional pasture plants along with perennials that provide off-season feasts.

This post is part of our 2011 Chicken Experiments lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

A generous coating of

dielectric grease should help to prevent corrosion on this Super

Winch ground connection.

What I'm not sure about is

how to prevent dirt and mud from getting into the grease.

Maybe a plastic barrier held

on with a few layers of duct tape?

Although the flavor of our Kieffer

pear was

disappointing, I didn't want to waste four years of vigorous and

disease free growth. The solution? Graft some new varieties

onto the tree so I get tasty pears.

Although the flavor of our Kieffer

pear was

disappointing, I didn't want to waste four years of vigorous and

disease free growth. The solution? Graft some new varieties

onto the tree so I get tasty pears.

Step

one is choosing varieties. Yup --- I meant to

use that plural. As long as you stay within the same species

(meaning, grafting pears onto pears), you can graft as many varieties

onto a tree as you have branches to graft to. After four years of

growth, I've got plenty of limbs to be converted to tastier fruits.

The factors most

important to me in pear tree variety selection are taste ("dessert

quality" is the word to look for), disease resistance (focusing on fire

blight), and time

of bearing.

Checking with your local extension

service is a good

way to find varieties that work well in your neck of the woods.

Here are the varieties I selected (all of which are fire blight

resistant):

- Dabney - very early bearer, developed in Knoxville (so probably

does well here), and listed as having very good dessert quality

- Tyson - very early bearer, flavor listed as "second only to Seckel"

- Harrow Delight - moderately early bearer, flavor noted to be as good as Bartlett but different

- Seckel --- early midseason, fruits are very small, but many sources list Seckel as having the best flavor of all pears

- Honeysweet --- midseason, flavor similar to Seckel but lacking the bit of grit in the center

- Hoskins --- late bearer and fruits will keep until Christmas, good for dessert

- Luscious --- late bearer, flavor like Bartlett

Step

two is finding scionwood. Scionwood is

basically a twig cut off of another tree that I will graft onto my

existing pear tree. As long as the graft takes, all further

growth on that limb will be the variety of the scionwood, not of the

tree being grafted onto.

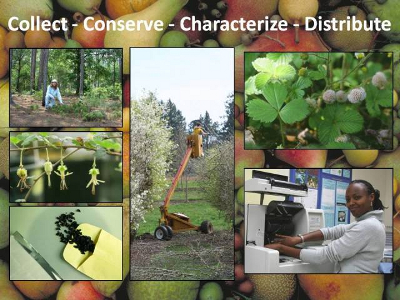

The holy grail of pear tree

scionwood is the National

Clonal Germplasm Repository in Corvallis, Oregon. (There are two other

branches of this government funded program that specialize in other

types of fruit.) It's a bit tough to tell from their website, but

I'm 95% sure that they will send two cuttings of any variety selected

to just about anyone for free --- I've put in my order and will know

more about the process in the winter when the scionwood (hopefully)

arrives. Requests for pear scionwood have to be made by December

1 to be shipped this winter.

The holy grail of pear tree

scionwood is the National

Clonal Germplasm Repository in Corvallis, Oregon. (There are two other

branches of this government funded program that specialize in other

types of fruit.) It's a bit tough to tell from their website, but

I'm 95% sure that they will send two cuttings of any variety selected

to just about anyone for free --- I've put in my order and will know

more about the process in the winter when the scionwood (hopefully)

arrives. Requests for pear scionwood have to be made by December

1 to be shipped this winter.

The Clean

Plant Center of the Northwest (part of Washington State

University) has a slightly less staggering but still pretty good

selection of scionwood available as well. They charge $5 per

"budstick", each of which generally has ten or more buds on it.

For simple grafts, you need two buds apiece, and you can also graft a

bud at a time, so a single budstick goes a long way.

In the commercial

sphere, several nurseries offer small selections of pear scionwood, but

Nick Botner is the best source if you want something even moderately

unusual. Unfortunately, Mr. Botner has no internet presence

(beyond folks mentioning his amazing selection), so you have to mail

your order to 4015 Eagle Valley Road, Yoncalla, OR 97499 or call him at

(503) 849-2781. I've uploaded his 2009 variety list

for your perusal, but you should be aware that internet rumors say he

put his farm on the market this past summer, so Mr. Botner may no

longer be selling scionwood.

Step

three is grafting.

But I have to wait until early spring for that step, so I'll stop here.

Unless you raise your own

meat birds (often called "broilers"), you

have probably only eaten one kind of chicken in your life --- Cornish

Cross. This hybrid is a wonder of modern breeding since it can

reach a

carcass size of nearly nine pounds in just eight weeks. The

Cornish Cross

also has a lower feed

conversion rate

than any other variety of chicken, which means you give the

birds less grain for every pound of weight they put on --- a boon for

your wallet and for the environment.

Unless you raise your own

meat birds (often called "broilers"), you

have probably only eaten one kind of chicken in your life --- Cornish

Cross. This hybrid is a wonder of modern breeding since it can

reach a

carcass size of nearly nine pounds in just eight weeks. The

Cornish Cross

also has a lower feed

conversion rate

than any other variety of chicken, which means you give the

birds less grain for every pound of weight they put on --- a boon for

your wallet and for the environment.

Homesteaders groan about

the Cornish Cross because of the multitude of

health problems that come along with their rapid weight gain, but what

prevented me from raising these efficient birds is their proprietary

genetics. Not only is the Cornish Cross a hybrid, the parent

lines are

owned by corporations, so the only possible way to get Cornish Cross

chickens is to buy the chicks from a hatchery. I want our flock

to be

as self-sufficient as possible, and that means raising our own chicks,

so Cornish Cross are off the table, as are other hybrid broiler

varieties like Freedom Rangers.

On the other hand, there are two

problems with raising heirloom chickens for meat, and

both are so serious that you probably won't find heirlooom broilers for

sale even at the

farmer's market. The first problem is aesthetics. Since we

all grew up with big, plump-breasted chickens on our plates, we think

that heirloom chickens

look odd, with their big thighs sticking out and their skinny

breasts.

I crunched some numbers from one of our batches of Black Australorps

and discovered that they gave me twice as much dark meat as light meat,

which would be a problem if I was afraid of animal fats. Luckily,

I

believe that fat from pastured animals is good for me, so I cherish

both light and dark meat from our homegrown birds.

On the other hand, there are two

problems with raising heirloom chickens for meat, and

both are so serious that you probably won't find heirlooom broilers for

sale even at the

farmer's market. The first problem is aesthetics. Since we

all grew up with big, plump-breasted chickens on our plates, we think

that heirloom chickens

look odd, with their big thighs sticking out and their skinny

breasts.

I crunched some numbers from one of our batches of Black Australorps

and discovered that they gave me twice as much dark meat as light meat,

which would be a problem if I was afraid of animal fats. Luckily,

I

believe that fat from pastured animals is good for me, so I cherish

both light and dark meat from our homegrown birds.

The second problem with

heirloom chickens is the real sticking point

--- feed conversion rate. The chicken industry claims that

factory-farmed Cornish Cross chickens have a feed to meat conversion

rate of 2:1 meaning that you feed the chickens two pounds of feed and

get back one pound of meat (and bones.) Third party studies of

pastured Cornish Cross chickens report a rate of 3.5:1 at the best, so

this is what I'm aiming for. And I fell far, far short --- more

on that tomorrow.

This post is part of our 2011 Chicken Experiments lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

I wrapped the plastic bag our

license plate came in around the Super

Winch negative ground connection and then secured it with a couple

strands of galvanized wire. I realize now that dielectric

grease may not have been the best choice for corrosion prevention, but it should keep the air out,

and if I can remember I'll peel the plastic back a few years from now

and check up on the corrosion status.

The positive end requires a

surge protector, which was easy to install.

Digging out a small trench

where the truck had bottomed out was the hard part. It was pretty well

packed in and I didn't want to take a chance of over straining the Super Winch

motor on its first day at work.

If you want to monitor the

varroa mite levels in your bee hives, it's a good idea to take counts

at multiple times rather than using one snapshot to assess the long

term health of your hive. So I repeated my three

day stickyboard counts

this week. To refresh your memories, the

mother hive dropped 44 varroa mites per day in mid September while the

daughter hive dropped 12 per day.

If you want to monitor the

varroa mite levels in your bee hives, it's a good idea to take counts

at multiple times rather than using one snapshot to assess the long

term health of your hive. So I repeated my three

day stickyboard counts

this week. To refresh your memories, the

mother hive dropped 44 varroa mites per day in mid September while the

daughter hive dropped 12 per day.

My new count showed

nearly the same mite fall for the mother hive --- 41 mites per day ---

but it seemed like the varroa mite population in the daughter have had

undergone a population explosion. This time, the daughter hive

dropped 200 total mites, or 67 per day!

An increasing varroa

mite population in the autumn is bad news, but I decided to get a bit

more scientific before I started to worry. Mite fall is a

problematic way to monitor varroa mites since a large population of

bees will naturally drop many more mites than a small population of

bees. The way to deal with this error is to estimate how many

bees are currently in your hive and calculate mite fall per thousand

bees per day.

No, I didn't sit in front of

the hive and count heads all day long. Instead, I looked through

both hives, counting how many frames (or portions of frames) were

covered with bees. A deep frame completely covered with bees on

both sides holds roughly 2,000 workers, so I was able to come up with

population estimates for both hives.

No, I didn't sit in front of

the hive and count heads all day long. Instead, I looked through

both hives, counting how many frames (or portions of frames) were

covered with bees. A deep frame completely covered with bees on

both sides holds roughly 2,000 workers, so I was able to come up with

population estimates for both hives.

Remember how I started feeding

the daughter hive a

few weeks ago since I was concerned that she was going into winter with

too few honey stores? One of the troubles with fall feeding is

that it can prompt the queen to lay lots of eggs at a time of year when

the hive doesn't need that many workers. The mother hive --- not

fed, so changing her population based on the natural ebb of the seasons

--- had roughly 9,500 bees in the hive. On the other hand, the

daughter hive had bulked up drastically and now housed 18,250 bees!

The good news is that when

you divide the mite fall figures by the population of each hive, it

turns out that the daughter hive is in fine shape. The mother had

roughly 4.3 varroa mites fall per thousand bees per day during my test

while the daughter had 3.7 mites per thousand bees per day. Given

all of the wiggle room in my measurements, I'd say mite populations in

each hive are roughly equal on a per bee basis.

The good news is that when

you divide the mite fall figures by the population of each hive, it

turns out that the daughter hive is in fine shape. The mother had

roughly 4.3 varroa mites fall per thousand bees per day during my test

while the daughter had 3.7 mites per thousand bees per day. Given

all of the wiggle room in my measurements, I'd say mite populations in

each hive are roughly equal on a per bee basis.

The bad news is that the

daughter hive has way too many workers in it! She has put away

the 22 pounds of sugar I gave her and now has 48 pounds of capped

honey, but I'm a little concerned that the massive population of

workers will eat right through it before winter comes. Hopefully

once the unnatural "nectar flow" disappears, the hive will kick out

those extra workers ASAP.

As I mentioned

yesterday, the feed

conversion rate of

3.5:1 for pastured Cornish Cross is extremely tough to beat.

We've tried four different experiments with raising heirloom chickens

as broilers and yet my very best

feed to meat conversion rate was 5:1. The figure means that my

chickens required 5 pounds of storebought feed for every pound of meat

I got back, half again as much as what Cornish Cross would have

consumed.

As I mentioned

yesterday, the feed

conversion rate of

3.5:1 for pastured Cornish Cross is extremely tough to beat.

We've tried four different experiments with raising heirloom chickens

as broilers and yet my very best

feed to meat conversion rate was 5:1. The figure means that my

chickens required 5 pounds of storebought feed for every pound of meat

I got back, half again as much as what Cornish Cross would have

consumed.

My best results came

from Black Australorps who ran in

the woods in the spring (thus getting nearly maximum forage) and then

were slaughtered at 12 weeks. At the far opposite extreme, Dark

Cornish chickens raised on overgrazed summer pasture and killed at 16

weeks had an abyssmal feed conversion rate of 8.8:1.

Here are some mistakes

you should avoid if you want to feed your broilers as little as

possible.

Slaughtering the chickens at a

more advanced age. At 12 weeks, light-weight breeds result

in carcasses of two pounds or smaller, so it seemed to make sense to

kill some a month later. Unfortunately, the growth

rate of chickens peaks around 6 to 10 weeks, so you have to feed

your flock more and more for that extra growth. To

feed the least, slaughter your chickens young.

Slaughtering the chickens at a

more advanced age. At 12 weeks, light-weight breeds result

in carcasses of two pounds or smaller, so it seemed to make sense to

kill some a month later. Unfortunately, the growth

rate of chickens peaks around 6 to 10 weeks, so you have to feed

your flock more and more for that extra growth. To

feed the least, slaughter your chickens young.

- Raising chickens during the summer lull. In our area, the succulent plants that chickens prefer are a spring and fall attraction, so I guess I shouldn't be surprised that the Cuckoo Marans we raised on summer pasture had a feed conversion rate of 5.2:1 even when killed at 12 weeks.

Keeping broilers in with laying hens.

My third batch --- Black Australorps part two --- had a truly awful

feed conversion rate of 7.6:1 at 12 weeks. The problem here is

that I mixed the broilers in with our laying flock, assuming that the

hen we tricked into adopting them would make sure the chicks had first

dibs on the food. This worked at first, but during the last month

(when broilers consume the majority of their lifetime feed), the mother

hen cut her offspring loose, and they were stuck at the bottom of the

pecking order. I had to throw in more and more food just to make

sure they had enough to eat. In future, broilers will always get

their own coop and pastures.

Keeping broilers in with laying hens.

My third batch --- Black Australorps part two --- had a truly awful

feed conversion rate of 7.6:1 at 12 weeks. The problem here is

that I mixed the broilers in with our laying flock, assuming that the

hen we tricked into adopting them would make sure the chicks had first

dibs on the food. This worked at first, but during the last month

(when broilers consume the majority of their lifetime feed), the mother

hen cut her offspring loose, and they were stuck at the bottom of the

pecking order. I had to throw in more and more food just to make

sure they had enough to eat. In future, broilers will always get

their own coop and pastures.

Even if I don't repeat any of

these mistakes, it's going to be tough to cut the amount of feed we

give to our broilers enough to achieve the awesome feed conversion

rates of Cornish Cross. That said, I have high hopes that the

Light Sussex we're currently experimenting with might do better than

our best batch of Black Australorps. I hatched the Sussex chicks

so late that I figured they wouldn't harm the garden if allowed to free

range, and they've been gorging on wild food ever since.

Meanwhile, I'm gauging

their feed needs by the state of their crops, which allows me to feed

them much less than the books tell me to. I'll report their feed

conversion rate on our chicken

blog around Thanksgiving, so stay tuned!

Even if I don't repeat any of

these mistakes, it's going to be tough to cut the amount of feed we

give to our broilers enough to achieve the awesome feed conversion

rates of Cornish Cross. That said, I have high hopes that the

Light Sussex we're currently experimenting with might do better than

our best batch of Black Australorps. I hatched the Sussex chicks

so late that I figured they wouldn't harm the garden if allowed to free

range, and they've been gorging on wild food ever since.

Meanwhile, I'm gauging

their feed needs by the state of their crops, which allows me to feed

them much less than the books tell me to. I'll report their feed

conversion rate on our chicken

blog around Thanksgiving, so stay tuned!

This post is part of our 2011 Chicken Experiments lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

We could really feel the power of the new Super

Winch as it slowly pulled the truck out of the mud and onto solid

ground.

A couple more hours of rut

repair should have the driveway ready for a trip to the quarry.

--- John Seymour, The Self-Sufficient Life and How to Live It

Despite the fact that

our property is 58 acres, I'd say our homestead is closer to one acre

in size since that's how large of an area we've carved out of the

wilderness. So I was struck by John Seymour's description of a

one acre homestead, and specifically by his conclusion that it does make sense to keep a lot of

livestock even if you have to buy hay and grain for them. He

argues that a cow produces high quality dairy for your family and for

all of the other livestock while also making huge quantities of manure

to improve the fertility of the land.

We're not going to be

getting a dairy cow anytime soon. There's not only the milking,

fencing, housing, and so forth to consider, but also the roughly $1,400

worth of grain, hay, and bedding that would go into her with only a

half acre to graze on. (And the question of how to deal with

1,500 gallons of milk per year....) However, Seymour's point is

well taken, that perhaps I shouldn't beat myself up so much about

buying all those bags of chicken feed --- after all, we do get quite a

lot of benefit from the manure we capture in the coop. And maybe

I shouldn't veto other potential livestock just because they would also

require storebought inputs of feed.

Looking at the problem

of farm fertility through Seymour's eyes, livestock are to compost as

cover crops are to mulch --- they're a way to grow your own. I

was amazed this year to see how much easier it is to plant

fallow fall beds in winter oats rather than hauling in and

then lugging around big bales of straw to mulch the bare ground.

But is there a type of livestock that would require little enough time

and feed input to make it worthwhile in comparison to Mark's trips to

the manure

motherlode?

Maybe rabbits? One pair

of New Zealand Whites will produce about 8 litters per year, with 40

surviving rabbits that dress to around 3.3 pounds apiece. That's

132 pounds of meat and 2 cubic yards of manure for the price of 750

pounds of feed ($255) and perhaps $20 worth of straw for bedding.

Plus they're a whole lot less work than the goats I've been drooling

over. Maybe I should set my sights a little lower?

Maybe rabbits? One pair

of New Zealand Whites will produce about 8 litters per year, with 40

surviving rabbits that dress to around 3.3 pounds apiece. That's

132 pounds of meat and 2 cubic yards of manure for the price of 750

pounds of feed ($255) and perhaps $20 worth of straw for bedding.

Plus they're a whole lot less work than the goats I've been drooling

over. Maybe I should set my sights a little lower?

It's possible to wrap the Super

Winch cable around a tree and hook it onto itself. The instructions

clearly say to not do this.

I'm guessing it's because the

cable could get damaged.

We had a heavy chain for

wrapping around trees, but it somehow got lost it in the weeds a few

years ago. Now we use a cable with hooks on each end or a heavy duty

nylon tow strap depending on the situation.

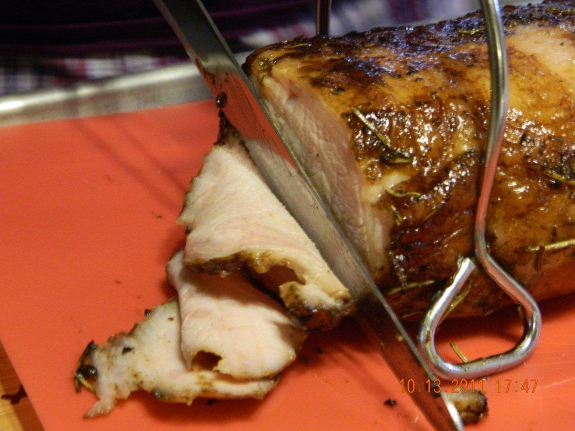

When

you start cooking with heritage

chickens, you'll

soon need to figure

out what to do with all that extra leg meat. (You might have a

similar dilemma if you're buying from the store on a budget since legs

are often much cheaper per pound than breasts.) This simple

recipe is surprisingly delicious and takes just a few minutes of

hands-on labor to prepare.

If

you're starting with a whole chicken, first cut off the legs.

You'll be surprised how easy this is --- just slice through the skin

that connects each leg to the

breast, bend the leg sideways until the bone snaps out of its socket,

and then cut through the bit of meat holding the thigh to the rest of

the chicken carcass.

If

you're starting with a whole chicken, first cut off the legs.

You'll be surprised how easy this is --- just slice through the skin

that connects each leg to the

breast, bend the leg sideways until the bone snaps out of its socket,

and then cut through the bit of meat holding the thigh to the rest of

the chicken carcass.

Meanwhile, snip some

thyme leaves out of your garden --- about a

tablespoonful is the goal if you're cooking two chicken legs. Mix

the diced thyme, two tablespoons

of lemon juice, and some salt and  pepper in a bowl.

pepper in a bowl.

Heat a bit of olive oil

over medium-high heat (being careful not to

burn it), then put your chicken legs in the pan, skin side down.

Brush about half of your lemon juice and thyme mixture over top of the

legs and

cook for around five minutes until the skin is brown.

Now turn down the heat

to medium-low and flip the legs over.

Brush on the rest of the lemon juice, leaving some thyme behind in the

bowl, cover the pan, and let cook for 20 or 30 minutes (just enough

time to write a blog post and  make a salad.) You can

tell the legs are getting

done when the meat starts to pull away from the end of the bone (or you

can use a meat thermometer.)

make a salad.) You can

tell the legs are getting

done when the meat starts to pull away from the end of the bone (or you

can use a meat thermometer.)

Remove the legs from the

pan once they're fully cooked and add 1 clove

of minced garlic, the remainder of the thyme, and three tablespoons of

water to the pan. Cook over medium high heat, scraping the

drippings out of the pan and into the water. After a minute or

two, the garlic should be cooked and the water should be evaporated

enough to turn the drippings into a thick sauce to spoon over the legs.

Despite having no

special spices (or MSG), these legs taste very Chinese to us.

Delicious and easy!

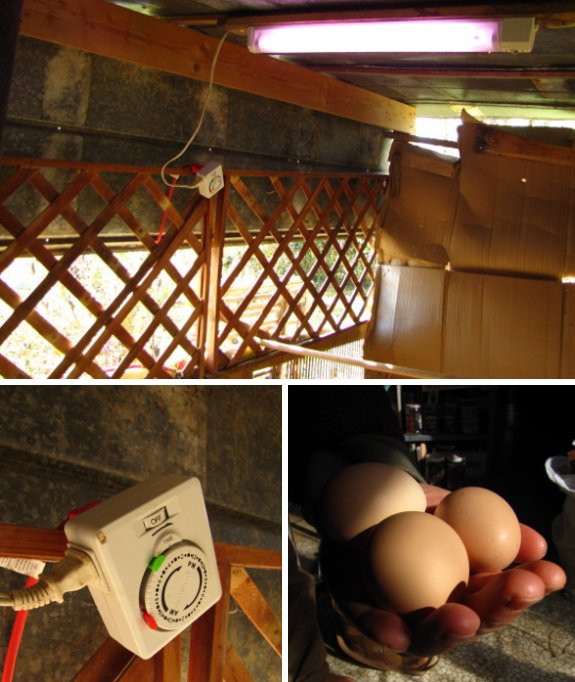

This automatic chicken

plucker is a clever and low budget alternative to the more expensive

800 dollar whiz bang option.

Kate

over at living the frugal life.blogspot.com has a nice post on her

experience building one for under 20 dollars.

I'm not sure if it's much of

a time saver, but I love the ingenuity and spirit of this poultry

project. It would be nice to see a side by side comparison of someone

trained on this method next to someone plucking by hand.

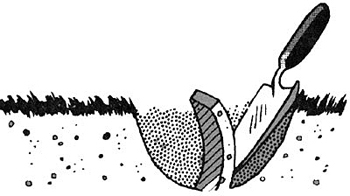

Soil

tests are very helpful for any kind of serious gardener since they give

you solid, numerical data about your soil. You can think of them

as a report card, showing you positive (or negative) changes over the

years and also pointing out areas that you need to work on.

There's plenty of information out there (like this site) to tell you how to take the

actual soil test, and I recommend this in-depth

pdf document to learn more about how your test results relate to

individual crops.

But the real question is --- which laboratory should you send your soil

sample to?

Soil

tests are very helpful for any kind of serious gardener since they give

you solid, numerical data about your soil. You can think of them

as a report card, showing you positive (or negative) changes over the

years and also pointing out areas that you need to work on.

There's plenty of information out there (like this site) to tell you how to take the

actual soil test, and I recommend this in-depth

pdf document to learn more about how your test results relate to

individual crops.

But the real question is --- which laboratory should you send your soil

sample to?

I always recommend

starting by checking with your state extension

service since most offer free or cheap soil tests. However,

extension service laboratories often skimp on testing micronutrients

and heavy metals, so it's worth spending a bit more cash at least once

during the life of your garden to get an idea of the bigger picture.

ATTRA

provides an extensive list of soil testing laboratories, but you could

spend hours checking out each one's services! (I know because I

just did.) When it comes to a wide selection of services for a

low price, there seem to be four main contenders.

ATTRA

provides an extensive list of soil testing laboratories, but you could

spend hours checking out each one's services! (I know because I

just did.) When it comes to a wide selection of services for a

low price, there seem to be four main contenders.

The cheapest

option is A&L Eastern Laboratories,

which offers a basic soil test for only $8.50 if you skip the

interpretation. (Since most interpretation is geared toward

large-scale farmers applying chemical fertilizers, you'll need to

figure out what the numbers mean on

your own anyway.) This test will cover organic matter, nitrogen,

phosphorus, potassium, magnesium, calcium, pH, buffer index, cation

exchange capacity, and percent base saturation. For an extra $4,

you can add on sulfur, zinc, manganese, copper, and boron. For

$15, you can test your soil for molybdenum, which is primarily of

interest for those of us trying to increase clover in our pastures.

AgriEnergy Resources offers pretty much the same tests

for quite a bit more cash.

Their basic package is $14.20 and throws in sodium (which you probably

don't need) while their higher end package includes the extras from the

last lab with the addition of iron for a total of $25. A separate

test for cobalt, molybdenum, and selenium is $46. Cobalt, like

molybdenum, is of interest to clover growers, while selenium is a

micronutrient important in our immune system but seldom deficient.

Maine Soil Testing Service is a little more expensive

than the cheapest commercial labs --- $15 for their basic test --- but includes

nearly all of the extras in the same package. However, they leave

out buffer index and percent base saturation while adding lead.

Finally, testing for nitrogen is $7 extra. (Although nitrogen is

very basic to the fertility of soil, I can see why they leave it out

--- you're going to add nitrogen in the form of compost every year

regardless and values can shift a lot from day to day depending on

microbial

activity. If you're not adding chemical fertilizers or farming on

a large scale, I'm not so sure you need to have that information in

your test results.)

Finally, UMass Amherst has perhaps

the best deal of all, especially for urban dwellers

worried about heavy metals. Their base package ($10) has

everything previously mentioned except sodium, sulfur, organic matter,

and nitrogen (and molybdenum, cobalt, and selenium which aren't

available anywhere without paying quite a bit extra.) Meanwhile,

they add in four more metals --- cadmium, nickel,

aluminum, and chromium. I'd pay $15 for the basic tests plus

organic matter, though, because I think organic matter is important

enough to keep track of long term. Nitrogen is its own test,

available for $15, which I would skip, and I can do without sodium and

sulfur.

Finally, UMass Amherst has perhaps

the best deal of all, especially for urban dwellers

worried about heavy metals. Their base package ($10) has

everything previously mentioned except sodium, sulfur, organic matter,

and nitrogen (and molybdenum, cobalt, and selenium which aren't

available anywhere without paying quite a bit extra.) Meanwhile,

they add in four more metals --- cadmium, nickel,

aluminum, and chromium. I'd pay $15 for the basic tests plus

organic matter, though, because I think organic matter is important

enough to keep track of long term. Nitrogen is its own test,

available for $15, which I would skip, and I can do without sodium and

sulfur.

You'll hear the

results of my soil tests in a week or two, so stay tuned for more than

you ever wanted to know about interpreting soil test results. Why

not dig up your own soil sample and play along?

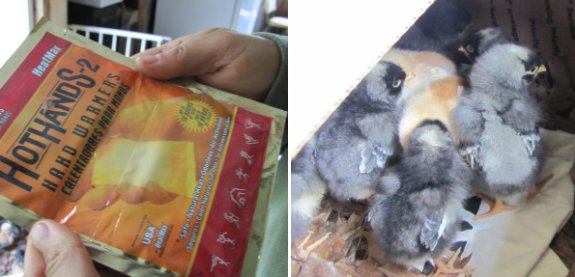

Incubating

my own chicks this year allowed me to experiment with smaller

batches

than I could get from a hatchery while also trying out rare varieties

of non-nursery stock. There was a steep learning curve, though,

and I soon learned that incubating is more complex than setting the

temperature and number of days in the incubator and then forgetting the

chicks until they hatched. Here are some of the questions I asked

as I went from a beginner to an intermediate incubator.

Incubating

my own chicks this year allowed me to experiment with smaller

batches

than I could get from a hatchery while also trying out rare varieties

of non-nursery stock. There was a steep learning curve, though,

and I soon learned that incubating is more complex than setting the

temperature and number of days in the incubator and then forgetting the

chicks until they hatched. Here are some of the questions I asked

as I went from a beginner to an intermediate incubator.

What kind of incubator should I

use? We've

tried three different incubators, and the only one that worked well for

us was the Brinsea

Octagon 20 Advance.

At $300, the Octagon 20 isn't an incubator to buy on a whim, but the

lack of climate control in our trailer made the cheap Little

Giant Still Air Incubator that we bought at the local

feed store totally worthless. The Brinsea

Mini Advance Incubator

worked a little better (we got one surviving chick out of seven eggs),

but that incubator's utility is really in allowing you to see a hatch

up close and personal. It's agonizing to watch chicks who had an

improper incubation period try to struggle out of their shells and

fail, so if you're going to incubate, you should probably do it right.

What kind of incubator should I

use? We've

tried three different incubators, and the only one that worked well for

us was the Brinsea

Octagon 20 Advance.

At $300, the Octagon 20 isn't an incubator to buy on a whim, but the

lack of climate control in our trailer made the cheap Little

Giant Still Air Incubator that we bought at the local

feed store totally worthless. The Brinsea

Mini Advance Incubator

worked a little better (we got one surviving chick out of seven eggs),

but that incubator's utility is really in allowing you to see a hatch

up close and personal. It's agonizing to watch chicks who had an

improper incubation period try to struggle out of their shells and

fail, so if you're going to incubate, you should probably do it right.

Is

every egg created equal? No, and you'll have a

much better hatch rate if you put only the best eggs in your

incubator. Eggs to discard include those with even a tiny bit of

poop  on the shell, porous eggs that

seem to be speckled when you hold them up to the light, and eggs from

hens more than two years old. Of course, cracked eggs or eggs

that have been stored

improperly shouldn't be included. In addition, more eggs tend

to be fertile in the spring and fall than in the summer and winter.

on the shell, porous eggs that

seem to be speckled when you hold them up to the light, and eggs from

hens more than two years old. Of course, cracked eggs or eggs

that have been stored

improperly shouldn't be included. In addition, more eggs tend

to be fertile in the spring and fall than in the summer and winter.

How

many chicks should I expect? If you're doing

everything just right, you should expect 75% to 80% of homegrown eggs

to hatch. Mail

ordered hatching eggs

will have been bumped around in the post office, so 50% is considered a

good hatch rate there. You can tell whether a low hatch rate is

caused by your mistakes or by bad eggs if you count how many eggs were infertile. If you're a raw

beginner, put a lot more eggs than you need in the incubator --- I

ended up with only one living chick my first time around and had to

scurry to find it friends. (A lone chick is an unhappy

chick.) By my fourth hatch, though, I got a 58% hatch rate from

mail order eggs and felt very accomplished.

What's dry

incubation and should I do it? Mainstream hatching

literature tells you to add water to the wells in order to keep your

incubator at 40% to 50% humidity for the first 19 days. However,

many experienced hatchers report that running the incubator dry gives

them better hatch rates. Whether dry incubation works for you

will probably depend on your climate. The best way to decide

whether humidity in your incubator is in the right range is to weigh

your eggs every few

days and make sure they lose 13% of their weight by day 18.

What's dry

incubation and should I do it? Mainstream hatching

literature tells you to add water to the wells in order to keep your

incubator at 40% to 50% humidity for the first 19 days. However,

many experienced hatchers report that running the incubator dry gives

them better hatch rates. Whether dry incubation works for you

will probably depend on your climate. The best way to decide

whether humidity in your incubator is in the right range is to weigh

your eggs every few

days and make sure they lose 13% of their weight by day 18.

How and when should I prepare for

the hatch?

No matter whether you practice conventional or dry incubation, you want

to increase the humidity in the incubator to 65% or more on day 19 so

that the chicks will slide right out of their shells. This is

also the time for you to turn off the egg turner and remove any

dividers so that the eggs lay flat on their sides. If the well of

the incubator is chick-accessible, but sure to shield it so that no

chicks can fall in and drown.

How and when should I prepare for

the hatch?

No matter whether you practice conventional or dry incubation, you want

to increase the humidity in the incubator to 65% or more on day 19 so

that the chicks will slide right out of their shells. This is

also the time for you to turn off the egg turner and remove any

dividers so that the eggs lay flat on their sides. If the well of

the incubator is chick-accessible, but sure to shield it so that no

chicks can fall in and drown.

How

often should I open the incubator? You'll read that you

can only open the incubator once or twice a day during the hatch period

or the humidity will plummet, but I found simple ways to keep

the humidity high

while poking around inside as much as I liked. Despite

conventional wisdom, I've had best results moving chicks to the brooder

an hour or less after they hatched so that they don't injure other

chicks busy struggling out of their shells.

Should

I help

chicks hatch?

It's okay to help chicks hatch as long as you understand what

constitutes an abnormal hatch. A chick pipping

at the narrow end of the egg should always be helped

because healthy chicks will either die while trying to struggle out of

this improper position or will injure

themselves.

You might choose to help chicks that have pipped but not started to

unzip for an abnormal length of time (generally 24 hours, or until the

membrane starts to turn brown and dry), but in this case you're more

likely to be aiding a weak chick which that might have to be culled.

How

and when should I cull a chick? After helping a chick,

I generally put it in a spare incubator for a few hours to regain its

strengh, then move it to the brooder to join the other chicks. If

they attack the chick, chances are it's too weak and would die on its

own. In that case, I put the chick

in an airtight container with some baking soda and vinegar and it dies

relatively painlessly within seconds.

Is there an easier way to hatch

chicks? A broody

hen can do all of the work for you, but only certain varieties will

go broody. We added Cuckoo Marans to our flock this year in

hopes that we'll be able to raise chicks the easy way in 2012.

Is there an easier way to hatch

chicks? A broody

hen can do all of the work for you, but only certain varieties will

go broody. We added Cuckoo Marans to our flock this year in

hopes that we'll be able to raise chicks the easy way in 2012.

The only additional tip

I would give anyone wanting to become a journeyman hatcher is --- keep

lots of notes! I had several hypotheses on why certain eggs

didn't hatch, but only got real answers when I numbered each egg and

kept notes on everything about them. That way I was able to tell

that temperatures

in my incubator were slightly uneven. If the broody hens

don't come through for me next year, I should have even higher hatch

rates in the incubator.

This post is part of our 2011 Chicken Experiments lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

The driveway

troubled spot is now one of the more solid points thanks to several

well placed cinder blocks and some heavy tamping.

Anna says there's a 70%

chance of rain tomorrow.

That means there could be a

race between when the rain starts and how fast I can go pick up a load

of gravel, unload it into the other troubled areas, and haul in a few

supplies.

Mark and I have been

tossing around the idea of interns. On the one hand, I think we

know enough that a homesteader wannabe could learn a lot from us, we

certainly have plenty of extra work, and it would be great

to have more like-minded people around. On the other hand, we're

dyed in the wool introverts and the idea of having even a

low-maintenance, fascinating person on the property seven days of the

week gives me shivers.

There might be the possibility of housing the intern somewhere else

and/or sharing them with another farming group so that we don't

overwhelm our people-sensors --- we probably won't even give the idea a

shot if we can't find someone to fill that gap. That said, I

wonder if the idea even holds water. Time for a poll!

(Those of you reading

this on Facebook or via an RSS feed will probably have to come directly

to our website to participate.)

Our current idea is to

give the intern a place to stay and plenty of hands-on mentoring in

exchange for 20 hours of work per week. (They'd have to buy and

cook their own food, but might have a place to grow a garden.)

The work would involve learning, but would probably also involve a lot

of repetition, because that's what farms are like. If you were a

potential intern, would that sound good?

We actually have two

different potential internship ideas: the living homestead and the

microbusiness. Mark could really, really use an inventor's

apprentice, while I could really, really use someone good at weeding

and mulching. Do you think the same person would be likely to be

interested in both or are the farmer wannabes different from the people

who want to be financially independent?

How many interns do you

think we should have at one time? On the one hand, starting with

one intern sounds much less scary. On the other hand, maybe

interns are like chickens and goats --- more self-sufficient in flocks?

I dream that an intern

would take some training, but then would make work happen faster.

On the other hand, my nightmares involve interns who take more time to