archives for 09/2011

Mark and I have agreed

to table the issue of weed-eating livestock until spring or when we

have another

half acre fenced in

(whichever comes last), so I've been contenting myself with

research. I contacted a few breeders of Miniature

Cheviot Sheep to

figure out a ballpark estimate of how much it would cost us to get

started with a ram and ewe (around $500), and in the process "met"

Terri Brown, who turns out to keep both Miniature Cheviot Sheep and

Nigerian Dwarf Goats. She kindly agreed to let me post her

experiences (and some of her beautiful photos) on the blog to share

with you all.

Terri's 4H clubs runs petting zoos as fundraisers and she also

uses her livestock for milk, show, and pets, so her farm contains quite

a menagerie. I'll let her tell you the story in her own words:

Terri's 4H clubs runs petting zoos as fundraisers and she also

uses her livestock for milk, show, and pets, so her farm contains quite

a menagerie. I'll let her tell you the story in her own words:

I explained our situation to

Terri and asked her whether she thought we'd be better off with

miniature sheep or dwarf goats, and she replied:

I explained our situation to

Terri and asked her whether she thought we'd be better off with

miniature sheep or dwarf goats, and she replied:

We got our Nigerian Dwarfs in 1993 and have never regretted it. They have doggy personalities and become part of the family. Nigerians are perfect for attacking wild

brush... honeysuckle, brambles,

poison ivy (don't pet them afterwards!), and unwanted saplings.

They don't prefer grass and low forbes, however, so you end up mowing

that. We got the lambs last year for our pet zoos but find they

are wonderful mowers.

brush... honeysuckle, brambles,

poison ivy (don't pet them afterwards!), and unwanted saplings.

They don't prefer grass and low forbes, however, so you end up mowing

that. We got the lambs last year for our pet zoos but find they

are wonderful mowers.The Nigerians are polyestrous and produce kids & milk in any season. The sheep only breed in the fall, and if you miss it, oh well maybe next year? They only have singles or twins, unlike our goats who have triplets, quads and more! So the herd grows slowly, especially when three quarters of the flock are rams (at least in MY flock....)

My hubby, Mark, and I both agree Miniature Cheviot Sheep are a delight! Their uncomplicated way of thinking is a respite in our busy lives. They hang out together in a simple, fluffy white, peaceful group, rarely putting on a show like the goats do. The mini sheep are a blast at the county fair, getting a lot of attention in addition to winning a bunch of cash because they have their own division. Each species has its charm, and they do complement each other.

If we had more pasture,

it sounds like Terri's system of using both sheep and goats would be a

good one. Here's what she has to say about dual-caprine pasture

weed control:

They can be run together but I

prefer to rotate them through. I don't like having more than four

to six individuals per pen because of competition for food and my

attention, and mixing the two species is more complicated. They

have different ways of getting my attention, so it becomes a total mob

scene when they are together. Plus, although they can get along

sharing food, they each do better with their own special mixtures of

grain & minerals.

They can be run together but I

prefer to rotate them through. I don't like having more than four

to six individuals per pen because of competition for food and my

attention, and mixing the two species is more complicated. They

have different ways of getting my attention, so it becomes a total mob

scene when they are together. Plus, although they can get along

sharing food, they each do better with their own special mixtures of

grain & minerals.Never keep rams & bucks together; the bucks rear up and the rams bust their gut or bash them low from behind. I don't think wethers practice that behavior, but I don't have any yet so we'll see.

Terri concluded:

Miniature animals of all types are the rage

nowdays. Smaller families want a little taste of farmy life, and

they find poultry and small sheep & goats fit into their

lives. They want a small animal with less expensive shelter &

fence & transport requirements, and something that is more like a

pet. The Nigerian Dwarfs and Mini Cheviots win on both

counts.

Miniature animals of all types are the rage

nowdays. Smaller families want a little taste of farmy life, and

they find poultry and small sheep & goats fit into their

lives. They want a small animal with less expensive shelter &

fence & transport requirements, and something that is more like a

pet. The Nigerian Dwarfs and Mini Cheviots win on both

counts. Being registered helps, too, which guarantees the buyer that their babies will also be small, and gives you credibility as a reputable breeder (which you honor by helping the buyer get started right and by not selling sick babies).

Thanks so much for all

of that great information, Terri! If anyone's interested in

hiring a petting zoo for their DC area birthday party or buying

registered Nigerian Dwarf Goats or Miniature Cheviot Sheep, drop by

Terri's website at WoolyDogDown.com.

When hot water bath canning,

it's important to pay attention to

everything that goes in the jar. Sweeteners like honey and sugar

can be added with impunity, but including basil and onions in a tomato

sauce will raise the pH so much that you'd have to pressure can.

To stay on the safe side, look for proven recipes or simply can pure

fruits or tomatoes.

When hot water bath canning,

it's important to pay attention to

everything that goes in the jar. Sweeteners like honey and sugar

can be added with impunity, but including basil and onions in a tomato

sauce will raise the pH so much that you'd have to pressure can.

To stay on the safe side, look for proven recipes or simply can pure

fruits or tomatoes.

While I'm on the topic

of acidity, I should mention that the acidity

levels of tomatoes may sometimes be too low for hot water bath canning

unless you add a bit of bottled (not fresh) lemon juice or citric

acid. The magic cutoff point is 4.6 --- tomatoes with a pH at or

above this pH are not safe to hot water bath can on their own.

Proven tomatoes that definitely need lemon juice added include:

Depending on who you talk to,

San Marzano tomatoes may or may not be safe.

Depending on who you talk to,

San Marzano tomatoes may or may not be safe.

Varieties that

definitely have a pH low enough to allow you to hot

water bath can them without adding any lemon juice or citric acid

include:

However, to make the decision

even more complex, a high acid tomato variety may

produce low acid tomatoes if the fruits are overripe, bruised, cracked,

affected by blossom end rot, or nibbled by insects. In addition,

tomatoes ripened off the vine, in the fall when days are shorter, in

the

shade, or on dead vines can all have a pH too high to allow hot water

bath canning without added lemon juice. To play it safe, you

might as well add the lemon juice recommended in most modern recipes (2

tablespoons per quart of crushed tomatoes.)

However, to make the decision

even more complex, a high acid tomato variety may

produce low acid tomatoes if the fruits are overripe, bruised, cracked,

affected by blossom end rot, or nibbled by insects. In addition,

tomatoes ripened off the vine, in the fall when days are shorter, in

the

shade, or on dead vines can all have a pH too high to allow hot water

bath canning without added lemon juice. To play it safe, you

might as well add the lemon juice recommended in most modern recipes (2

tablespoons per quart of crushed tomatoes.)

To read more, check out Weekend

Homesteader: September

on Amazon (or email anna@kitenet.net and ask for your free pdf

copy.) Thank you to everyone who has already given the ebook a

try, and I would

be eternally grateful to anyone who takes the time to leave a review!

This new method of protecting

our delicate strawberry plants with a dome of plastic fence material is

working quite well during these recent

deer attacks.

So

you want to mulch your garden to keep weeds at bay all winter, but

storebought mulch is out of your price range. What can you do?

So

you want to mulch your garden to keep weeds at bay all winter, but

storebought mulch is out of your price range. What can you do?

Oats

used as a cover crop

are the cheap and easy way to grow your own winter mulch. Prices

went up 35% since last year, but a 48 pound bag of oat seeds still cost

only $16 at our local feed store. I sow my oat cover crop very

heavily since I want to make sure weeds are shaded out, but the oats

are still far more economical than a bale of straw. My 48 pound

bag of oat seeds produces the same amount of aboveground biomass as

approximately 12 bales of straw ($48), not to mention the nitrogen the

roots capture and keep in circulation and the extra organic matter

produced underground.

An oat cover crop

instead of a heavy winter mulch of straw has another benefit --- labor

savings. We didn't have to haul straw onto and off of the truck,

onto the wheelbarrow,  and

then spread it in the garden. Instead, I just raked back what was

left of the summer mulch, scattered oat seeds on the ground, and

lightly sprinkled a bit of the leftover straw back in place to help the

seeds stay moist until they germinate. After an hour and a half

of light gardening, over 10% of our growing area is off my agenda until

spring.

and

then spread it in the garden. Instead, I just raked back what was

left of the summer mulch, scattered oat seeds on the ground, and

lightly sprinkled a bit of the leftover straw back in place to help the

seeds stay moist until they germinate. After an hour and a half

of light gardening, over 10% of our growing area is off my agenda until

spring.

Before you go out and

buy your own 48 pound bag of oats, you should be aware that oats

dependably winter-kill only in zone 6 and colder (although parts of

zone 7 may see the same results, depending on the severity of your

winter.) No matter where you live, you need to plant the oats

early enough that they are well established before cold weather hits,

which means you'll have to come up with some other mulch in garden gaps

that come open later than a month before your first frost date.

You may also have to deal

with weevils in your grain --- little insects that hollow out the seeds

and prevent them from growing. I eked out my 50 pound bag for a

solid year, but I noticed that the last beds I planted in early August

didn't come up fully, and a little investigation turned up lots of

insects in the seeds. For best results, only buy as much oat seed

You may also have to deal

with weevils in your grain --- little insects that hollow out the seeds

and prevent them from growing. I eked out my 50 pound bag for a

solid year, but I noticed that the last beds I planted in early August

didn't come up fully, and a little investigation turned up lots of

insects in the seeds. For best results, only buy as much oat seed

as you'll use this year --- most feed stores will sell you less than a

full bag if you ask nicely. On the other hand, if you put on your

thinking cap, you might find uses for the full 50 pounds. I used

over half of my bag in one morning of profligate sowing --- the bare chicken

pasture should be

green again shortly!

as you'll use this year --- most feed stores will sell you less than a

full bag if you ask nicely. On the other hand, if you put on your

thinking cap, you might find uses for the full 50 pounds. I used

over half of my bag in one morning of profligate sowing --- the bare chicken

pasture should be

green again shortly!

It's been really dry lately,

but I still managed to get the truck stuck yesterday.

We did a bit of research

prompted by a suggestion from Roland about the differential unit.

I called a local dealer, who

could tell from the VIN number that our particular model does not have

a "locker" mechanism, which locks up when your tires start to spin so

that each wheel turns equally, and then unlocks for regular driving so

that normal turning can still be done.

The parts alone were going to

be around 1000 dollars with an estimate of 300 for the labor. My

current plan is to track down a used differential unit that has the

"locker" feature and have our local mechanic swap them out.

We've also decided to get an

electric winch in the hopes that it might be able to pull us out of

spots like this in the future.

Despite how much time I

spend posting and commenting on our blog, I rarely explore the

internet. I check the weather, read RSS feeds of over 100 blogs,

ask questions of google, visit extension service websites to see what

the accepted wisdom is on agricultural issues, and use google image

search to identify this and that. But I don't surf. I don't

watch videos, I don't spend time on facebook, I don't follow people's

links.

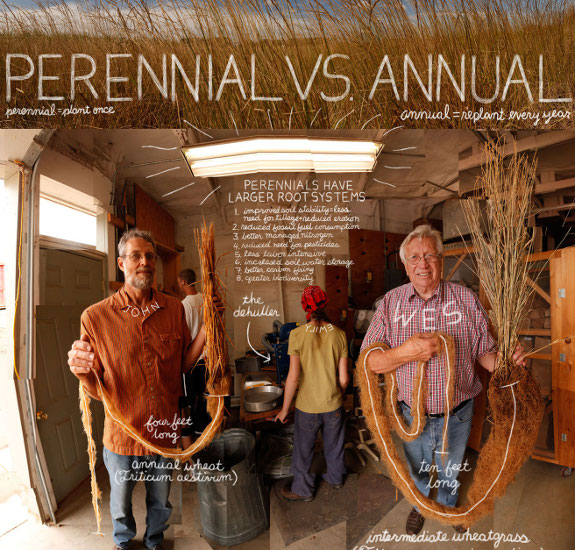

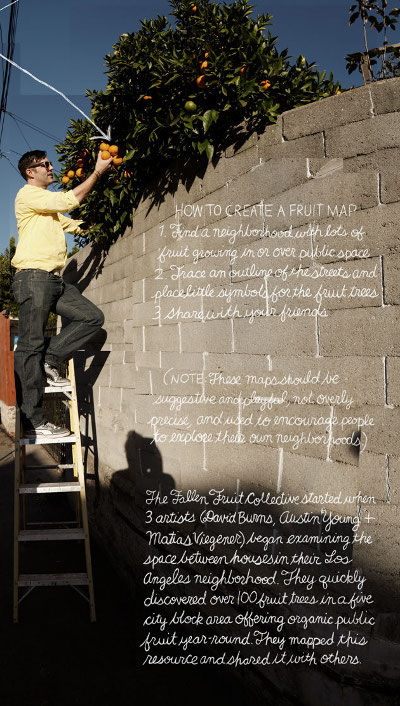

And yet...I just spent the

better part of an hour poring over the Lexicon of Sustainability

website:

And yet...I just spent the

better part of an hour poring over the Lexicon of Sustainability

website:

The images are stunning

--- a mish-mash of photography and words that illustrate many of the

agricultural concepts we embrace. The website is beautiful too,

but not very easy to use if you really want to pore over the

images. Instead, you'll need to right click on each image and

save it to your desktop so that you can zoom in and really read what

the artists/authors have to say. I've cropped a couple of the

images down so that you can read them here, but if you want a time

sink, I highly recommend you go check out the rest of the site.

Instead of putting the new

batch of chicks out in the big bird pasture we decided to convert

an old

chicken tractor into a poultry junior high.

The indoor

brood coop was getting too small, but we didn't quite feel like

they were ready for the real world due to losing some chicks back in

the spring to a mystery predator.

We've got them located behind

the trailer for ample shade and maximum protection. Even a casual

observer can notice an increase in the spring of their step with the

addition of this new environment complete with untold numbers of insects

and worms.

Our tractored

chicks were having the time of their lives...until the thunderstorm

hit. Our chicken tractors have covered sections which kept our

adult chickens quite happy through all four seasons, but chicks are

another matter entirely. Without real feathers, the little bit of

rain that splashed under the covering was quickly chilling our baby

flock, so they started piling on top of each other in distress.

I decided it was high time to step in and bring them back inside, so I

scooped up damp chicks as fast as I could catch them. "One, two,

three," I counted as I plopped each one down in a tupperware container

for transport. "...Eleven, twelve, thirteen."

Thirteen?! There were supposed to be fourteen chicks in this

tractor!

Better thirteen living chicks than fourteen dead ones, I thought,

rushing the youngsters inside to warm up in their brooder. But

what had happened to number fourteen?

Back I went into the pouring rain, first calling for the chick, then

sitting quietly in hopes that I'd hear his anguished chirping.

Silence. Did he get out of the tractor and snapped up by one of

our cats in those three brief hours of pastured life?

I poked my hand in the tractor and noticed

that the chick pileup had occurred right where two pieces of carpet

came together. Mark had simply overlapped the fabric by a few

inches during construction since the overlap was plenty to keep adult

chickens inside, but I was able to slide my hand right through the

gap. Maybe one chick had fallen out and was wandering in this

downpour looking for shelter.

I poked my hand in the tractor and noticed

that the chick pileup had occurred right where two pieces of carpet

came together. Mark had simply overlapped the fabric by a few

inches during construction since the overlap was plenty to keep adult

chickens inside, but I was able to slide my hand right through the

gap. Maybe one chick had fallen out and was wandering in this

downpour looking for shelter.

I got down on my hands and knees and looked in all directions.

And there, under the trailer, stood one damp little chick, too scared

to cry. Mark and I captured him in short order and brought him

inside to join his siblings. Soon fourteen chicks were fluffed

back up, none the worse for wear.

One pastured poultry producer ran a side by side comparison

of coops with pastures versus chicken tractors and found that

chickens were healthier in the former. I see his point now --- I

wouldn't want to put chicks out in tractors permanently until they were

at least a month old. I guess we'll either be shoring up that

coop or keeping the youngsters inside for a little longer.

Have you ever wondered if it was possible to convert a lawn mower to

run on steam power?

I'm not sure how safe it is,

but I love the ingenuity of this project by Youtube user dsquad.

GreenPowerScience has a

neat video on how to take an old weed eater engine and convert it to

run on compressed air with the addition

of a well placed reed switch. This seems like a safer alternative to

steam power. It might be possible to build a contraption that powers a

small generator if one could somehow harvest compressed air.

To be honest, farm life has been less than idyllic lately. First there's been the crazy hot summer with temperatures five to ten degrees above average, which means we can only work outside for limited periods. Then there's the fall garden, only about 20% of which survived cat scratching, dog rolling, deer nibbling, and (worst of all) intense heat. Finally, there's the relentless march of the deer, eating up our hard work. We try to keep this blog positive, but in my personal life, I've had two meltdowns in the last few weeks, and poor Mark has had to do a lot of wife propping.

Mark tells me that my problem is lack of perspective --- that never having worked a relentless 9 to 5 job in a field I hate, I can't tell how good even our worst days are. He says that even when I wake him up early to herd chickens out of the garden after Lucy breaks into the pasture at 6 am looking for food scraps...even when the day involves the minisledge breaking in half and barely missing his nose...even when the heat is so intense his brain turns off but he has to keep on going...he's still happier than he was working at the spring factory.

"Look out in the

garden!" he continues, and I take his hand as he helps

me up out of the mud at the bottom of my emotional pit. "See all

that mulch, those beautiful beds of buckwheat, the paucity of

weeds? Last year at this time, the weeds were winning the battle

and you were just barely starting to understand cover crops. Our

farm is becoming more fertile every day!"

By now, without

realizing it, I've followed my husband up far enough that a

metaphorical

breeze cools my face. "All of these problems are the price we pay

for freedom," Mark says. "Yes, it tears at your soul when the

deer eat the garden, because that garden is like an appendage of our

bodies. But we're spending our hours building our own

world. Despite minor setbacks, the farm is improving every

minute, every week, every year, and it's all ours."

Perspective can be hard

to find on a late summer farm when you have to

run as fast as you can just to stay where you are. But when I sit

outside with a book to enjoy the cool evening and a woodcock flutters

down

nearly at my feet from his mating flight...dragonflies skim the garden

like fighter pilots...and a lightning bug lands in my hand, I remember

why we're here. I take the last step out of my emotional pit to

join Mark on his tree-shaded hilltop and we revel in the farm.

These pictures were taken

early this morning.

It's clear she got spooked by

one mechanical deer deterrent

and then another in the opposite direction.

Photographic proof that a

mechanical contraption can be quite effective at making these deer feel

like they crashed the wrong party.

I decided this spring

that it was time to either figure out how to replace the barn roof or

to tear the whole thing down. Honestly, I covet that flat, sunny

growing space, but Mark has pretty much convinced me that it would cost

as much to dismantle such a huge structure as to fix it up so that we

can use it (and I do need more room to cure

sweet potatoes), so

we started saving our pennies. Rather than going on vacation,

this year we're going to be buying tin and hiring someone (or multiple

someones) to clamber up to the top of the huge pole barn and get it

back in shape.

We've

been trying to find a dependable local guy who doesn't mind walking

half a mile through the muck to the job site --- no luck so far.

The barn was built to dry tobacco, which means it's absurdly high, and

I really don't want to climb up there (or to see Mark in such a

precarious position.) Do you have any ideas for how to find

someone crazy enough to work in our weird environment other than to

keep trying out every handyman we meet in town? How much do you

think someone would charge to do that kind of job? How many days

do you think it would take? I know there are specialized roofing

companies, but I suspect they're going to balk at the working

conditions.

We've

been trying to find a dependable local guy who doesn't mind walking

half a mile through the muck to the job site --- no luck so far.

The barn was built to dry tobacco, which means it's absurdly high, and

I really don't want to climb up there (or to see Mark in such a

precarious position.) Do you have any ideas for how to find

someone crazy enough to work in our weird environment other than to

keep trying out every handyman we meet in town? How much do you

think someone would charge to do that kind of job? How many days

do you think it would take? I know there are specialized roofing

companies, but I suspect they're going to balk at the working

conditions.

Meanwhile, I want to go

ahead and order the roofing metal so that we can drive it in the next

time the ground is dry enough. Sometime in the last decade, the

previous owners of the property stuck new tin on top of the central

section of the barn, and that area (nearly) doesn't leak, so I think we can just replace the two

rows of tin below the good section. Of course, roofing tin needs

to overlap, so you should really start at the bottom of the roof and

work your way up rather than at the top and work your way down.

Do you think it'll be feasible to pry up the bottom of the top tin to

slide new tin underneath?

I'm also just a tad bit

confused about how large the roofing panels are. A hasty

measuring session in the pouring rain shows that the barn is roughly 45

feet long by 36 feet wide, and the roof extends a bit further in each

direction. Each row of tin has 26 panels in it, so I suspect the

tin is the same 24 inches wide that the tin off the old house was, but

how long are the pieces? Short of climbing up in the rafters and

measuring the barn height, I figured I might be able to get away with

some photographic math. If the horizontal distance from the center of the

barn to the edge of the roof overhang is right around 19 feet, it looks

like the height from that line to the peak is roughly 8 feet, which

would make the tin on one side of the barn about 21 feet long.

These measurements would make sense if the original builders used three

sections of 8 foot tin, overlapping each one a bit to prevent leaks.

Assuming

my math isn't wrong, I'm thinking we need 104 pieces of eight foot by 2

foot "corrugated ribbed steel roof panels," aka "5V tin."

Presumably we need a bunch of roofing nails or screws too, and I'm

tempted to go ahead and have gutters installed on each side to take

advantage of that amazing rainwater catchment opportunity --- we could

be capturing 48,000 gallons of water every year if we had the

facilities. I think channeling that water somewhere other than the

forest garden would prevent the current gully erosion and waterlogged

conditions, and free water is nothing to sneeze at.

Assuming

my math isn't wrong, I'm thinking we need 104 pieces of eight foot by 2

foot "corrugated ribbed steel roof panels," aka "5V tin."

Presumably we need a bunch of roofing nails or screws too, and I'm

tempted to go ahead and have gutters installed on each side to take

advantage of that amazing rainwater catchment opportunity --- we could

be capturing 48,000 gallons of water every year if we had the

facilities. I think channeling that water somewhere other than the

forest garden would prevent the current gully erosion and waterlogged

conditions, and free water is nothing to sneeze at.

We're still very much in

the planning stages, and I'd love to get some expert advice before we

spend such a huge lump of money. Any amateur or professional

builders out there who can check my math or tell me where I'm barking

up the wrong tree?

The ground got a good soaking

last night, which prompted us to clear the weeds from one of the

chicken pastures so we can spread out some seeds and take advantage of

this recent wet cycle.

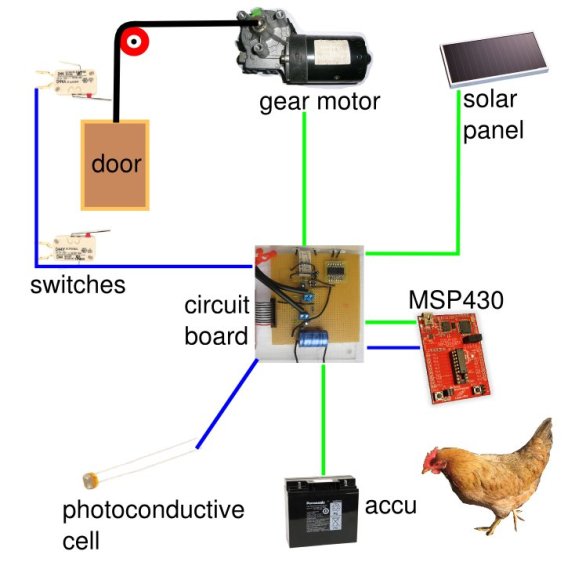

We then shored up chicken

coop number one by closing off some of the holes. Once we get it

secured the plan is to move the new

automatic chicken coop door opener over to this coop which will make that vulnerable sleeping time a little bit safer.

Maybe an alternative to an automatic

chicken coop door opener

is a simple dog door with a locking solenoid? A timer could control

when it's time to lock up at night, and maybe an electromagnet could be

used to crack the door open in the morning to encourage the flock that

it's time to push through. I guess the question is can a chicken learn

to open a pet door all by themselves?

I begged for drought to

slow the spread of blight on our tomatoes, and the weather

complied...for a while. You can only hold back our rain so long,

though, before the  weather

gods rebel and drop six inches of water on you in one fell swoop.

The creek rose, the jewelweed revived, and the parched earth in the

chicken pastures gave a sigh of relief. Time to change our plans

and renovate the forest

pasture now instead

of later.

weather

gods rebel and drop six inches of water on you in one fell swoop.

The creek rose, the jewelweed revived, and the parched earth in the

chicken pastures gave a sigh of relief. Time to change our plans

and renovate the forest

pasture now instead

of later.

The forest pasture was

chock full of life, but it was all out of reach of our chickens.

Despite being birds, chickens don't really fly, and once the weeds get

more than a couple of feet tall, the flock might as well be foraging in

a desert. The ninja

blade, the chainsaw,

and brute strength served to whack down the weeds, root out the logs,

and move all of the biomass to the edges of the pasture.

In the process, we were

treated to some magnificent finds, like the chorus frog pictured

earlier and the hickory horned devil shown here. I'll bet you've

never seen a caterpillar this big and scary --- I hadn't. This

guy will turn into a regal moth --- the heaviest moth north of Mexico

--- and despite its spines, the caterpillar won't sting.

In the process, we were

treated to some magnificent finds, like the chorus frog pictured

earlier and the hickory horned devil shown here. I'll bet you've

never seen a caterpillar this big and scary --- I hadn't. This

guy will turn into a regal moth --- the heaviest moth north of Mexico

--- and despite its spines, the caterpillar won't sting.

We planted an everbearing

mulberry in this pasture in the spring, but I haven't even been able to

see the tree for months due to the smothering action of Japanese

honeysuckle, hog-peanuts, and virgin's bower. Imagine my surprise

to discover that the mulberry was vine-wrapped but thriving, having

doubled in height already. Maybe our chickens will be treated to

summer fruits sooner rather than later.

We planted an everbearing

mulberry in this pasture in the spring, but I haven't even been able to

see the tree for months due to the smothering action of Japanese

honeysuckle, hog-peanuts, and virgin's bower. Imagine my surprise

to discover that the mulberry was vine-wrapped but thriving, having

doubled in height already. Maybe our chickens will be treated to

summer fruits sooner rather than later.

I'll be planting annuals

for winter forage (probably rye, oats, Austrian winter peas, and

oilseed radish) while the ground's still damp, but first I wanted to

give our chickens an opportunity to scratch the earth up a bit

first. Good thing we have such a large flock momentarily --- 19

near adult chickens, 8 of whom will go in the freezer this week.

Turning them onto such a

bare pasture makes it much easier to see the behavioral differences

between our various types of chickens. The Golden Comets

were the first to find the new pasture (a process that involves going

into the coop and then out a newly opened pophole), eventually followed

by just about everyone else. The White Cochin

and one Cuckoo

Marans just couldn't figure it out --- they stood forlornly on the

other side of the dividing fence, watching their buddies eat the

insects knocked loose during our clearing spree.

The Black

Australorps wandered around pecking for insects, but the Golden

Comets thought it was a better idea to stay in one place and scratch up

bugs. I got down close and was surprised to see that every swipe

of this old hen's foot turned up something edible --- little

earthworms, centipedes, and snails. The number of invertebrates

she consumed in such a short time was amazing.

For more on the larger

picture of chicken pasturing (and my evolving plans for our pastures),

be sure to subscribe to our chicken blog. As you probably

figured out, this post is really just about pretty pictures.

The creek was too high to get out yesterday, but it's no problem today

with my new

Pro Line hip waders.

It just barely qualifies as a

flood.

This particular model of hip

waders came with a pad of felt like material glued to the bottom of the

heel. The increase in traction comes in handy when walking through fast

flowing waters.

A bit over a day after

turning our flock into the

pasture we're renovating, they've already made quite

an impact. The photo above is the pasture's compost pile, so it

wasn't very weedy to begin with, but I can see bare ground in several

other locations as well.

I figure the annual

weeds (most notably ragweed) will be wiped out by our weedwhacking,

followed by a heavy round of chicken scratching, and then planting a

winter crop. The perennials will have to be cut several more

times next year before they'll give up the ghost, though.

My friend Megan not only

sells amazing

pastured meat, she

is also an experienced keeper of dairy goats, sheep, cows, pigs,

chickens, and just about any other type of farm livestock you can think

of. I picked her brains about our idea of adding miniature

goats or sheep to

our menagerie for weed control in the chicken pasture, and she had some

great local advice. She hasn't worked with miniature animals, but

reports that full-size sheep really aren't going to cut it on our rough

pastures, and that goats will be hard workers but absolutely refuse to

eat wingstem. Drat! Wingstem is one of our most common

perennial weeds.

Megan seconded one of

our reader's suggestions of running goats on new

ground using four cattle panels to make a relatively easy to move but

heavy duty goat "tractor." Her goats love Japanese honeysuckle

and will eat it down to the ground, but of course the vines will

regrow. She actually thinks we should get a pig and let it root

out all of the perennials at once then turn it into bacon, but I'm a

bit scared of that idea. I'm okay with slow and steady progress,

and our hens are definitely making headway.

I was surprised at how dark

chicken coop number one got after I sealed up most of the cracks.

A scrap piece of plexiglass

made a nice window to let a little light shine in.

This will be our last

generation of chicks for 2011.

When

I realized that soil

temperature was the limiting

factor keeping spring crops from sprouting early, I felt like I'd

discovered the scientific way to time my spring plantings. I

probably should have realized that there was a flip side to the soil

temperature coin --- many fall crops have trouble germinating in hot

summer soil.

When

I realized that soil

temperature was the limiting

factor keeping spring crops from sprouting early, I felt like I'd

discovered the scientific way to time my spring plantings. I

probably should have realized that there was a flip side to the soil

temperature coin --- many fall crops have trouble germinating in hot

summer soil.

| Vegetable |

Optimum

temp. (degrees F) |

Maximum

temp. (degrees F) |

| Beans, Snap |

80 |

95 |

| Cabbage |

85 |

100 |

| Carrots |

80 |

95 |

| Corn |

95 |

105 |

| Cucumbers |

95 |

105 |

| Lettuce |

75 |

85 |

| Muskmelons |

90 |

100 |

| Okra |

95 |

105 |

| Onions |

75 |

95 |

| Parsley |

75 |

90 |

| Peas |

75 |

85 |

| Peppers |

85 |

95 |

| Pumpkins |

95 |

100 |

| Spinach |

70 |

85 |

| Squash |

95 |

100 |

| Swiss chard |

85 |

95 |

| Tomatoes |

85 |

95 |

| Turnips |

85 |

105 |

| Watermelons |

95 |

105 |

This summer has been considerably warmer than average, but I assumed that as long as I kept my fall plantings well watered, they would grow. Not so. I managed to sprout a single spinach seedling out of three beds, only a third of my peas came up, and I wasn't able to germinate Asian greens and lettuce until I planted new areas at the shady end of the mule garden.

I finally thought to pull out

my soil thermometer one morning at the end of August, at which time I

discovered that the earth's temperature two inches down ranged from 65

degrees Fahrenheit in the more shaded front garden to 68 degrees

Fahrenheit in the sunny mule garden. Checking back at 6 PM when

the sun had pounded down all day, the mule garden soil temperature had

risen to 81 degrees. Yes, mulched spots were considerably cooler

--- clocking in at the low to mid seventies --- but my fall plantings

have all gone into bare soil since the seedlings are too small to push

aside mulch. A few weeks earlier when I was vainly planting

spinach seeds, I suspect the daytime soil highs easily exceeded the 85

degree Fahrenheit absolute upper limit for spinach germination.

I finally thought to pull out

my soil thermometer one morning at the end of August, at which time I

discovered that the earth's temperature two inches down ranged from 65

degrees Fahrenheit in the more shaded front garden to 68 degrees

Fahrenheit in the sunny mule garden. Checking back at 6 PM when

the sun had pounded down all day, the mule garden soil temperature had

risen to 81 degrees. Yes, mulched spots were considerably cooler

--- clocking in at the low to mid seventies --- but my fall plantings

have all gone into bare soil since the seedlings are too small to push

aside mulch. A few weeks earlier when I was vainly planting

spinach seeds, I suspect the daytime soil highs easily exceeded the 85

degree Fahrenheit absolute upper limit for spinach germination.So what's the solution for getting fall vegetables to germinate in the middle of a hot summer? Lowering soil temperature is probably the reason that some old gardening books recommend placing mulch or old boards over your fall plantings --- you just have to remember to uncover your seedlings as soon as they sprout. Another option is to plant fall vegetables in a cool, shady location, but that idea will backfire when winter cold nips those spots early. Perhaps shady beds could be used as nursery plots for larger fall vegetables, and the seedlings transplanted out into the main garden later? Or maybe there's a way to rig shade cloths to keep the soil temperature in range? I'd be interested to hear how those of you who live with this sort of summer weather every year get your fall garden to sprout.

It's that time of year when

oat cover crops flower and need to be retired.

Rake cut oats evenly on bed,

apply 5 gallon bucket of manure, cover with straw and repeat.

Many

gardeners don't water their garden at all, or just spot-water with a

cup or hose during transplanting or when specific plants wilt.

However, water is one of the most common limiting

factors, even in a

very wet climate like ours. Long before your plants droop,

they'll slow their growth to conserve moisture, so your yields in an

unwatered garden will be much lower.

Many

gardeners don't water their garden at all, or just spot-water with a

cup or hose during transplanting or when specific plants wilt.

However, water is one of the most common limiting

factors, even in a

very wet climate like ours. Long before your plants droop,

they'll slow their growth to conserve moisture, so your yields in an

unwatered garden will be much lower.

The importance of

regular irrigation was brought home to me this year when I got sick and

skipped watering for one hot week right when our earliest bed of Sugar

Baby watermelons was bulking up. Those fruits clocked in around

five inches in diameter, compared to the fruits on a later bed of the

same variety (well watered throughout their life) that produced ten

inch fruits. The moral of the story is --- your yields may double

if you provide a steady supply of water for your crops.

Of

course, watering your garden has many disadvantages. When you

look at the bigger picture, using more than your fair share of rivers

can cause them to dry up downstream, and there's nearly always at least

some energy required to move water to your crops. Closer to home,

irrigation equipment costs money, and so does either paying for city

water or paying the operating costs of your own pumps. I estimate

that we use a phenomenal 11,000 gallons of water every week during the

height of summer (exempting wet periods) to keep our vegetables

growing, which adds about $125 per year to our annual electric bill.

Of

course, watering your garden has many disadvantages. When you

look at the bigger picture, using more than your fair share of rivers

can cause them to dry up downstream, and there's nearly always at least

some energy required to move water to your crops. Closer to home,

irrigation equipment costs money, and so does either paying for city

water or paying the operating costs of your own pumps. I estimate

that we use a phenomenal 11,000 gallons of water every week during the

height of summer (exempting wet periods) to keep our vegetables

growing, which adds about $125 per year to our annual electric bill.

At the plant level, watering

can even do harm.

Overwatering hurts plants, and so does irregular watering. If

your crops are used to getting a regular dose of water every time the

soil starts to dry out, they won't have grown the deep roots needed to

withstand a drought (or to survive a week when you forget to water),

and wet leaves promote fungal diseases (like my tomato blights.)

If you water too much, you can also wash nutrients out of the soil,

which can stunt your plants and make your homegrown food less tasty and

nutritious. The trick here is to know your system and water

scientifically.

Unless

your climate is very arid (in which case it may not be sustainable to

live there in the first place), you can work around the other

irrigation-related problems as well. Catching rainwater is

something we want to get more serious about --- if you live in a large,

modern home and just have a small backyard garden, chances are your

roof runoff may be all you need to keep your plants hydrated. We

live in a small, unmodern trailer, but we're pondering adding gutters

to the East Wing, the barn, and/or the dreamed-of summer kitchen.

Unless

your climate is very arid (in which case it may not be sustainable to

live there in the first place), you can work around the other

irrigation-related problems as well. Catching rainwater is

something we want to get more serious about --- if you live in a large,

modern home and just have a small backyard garden, chances are your

roof runoff may be all you need to keep your plants hydrated. We

live in a small, unmodern trailer, but we're pondering adding gutters

to the East Wing, the barn, and/or the dreamed-of summer kitchen.

The next step to

watering in a sustainable manner is to make the water you do have go

further. Our watering method is the least efficient one out there

--- sprinklers --- which we chose for the

reasons listed here.

Using sprinklers means that we consume four times as much water as

necessary every time we irrigate --- some of that extra water hits the

garden aisles, some falls outside the garden perimeter, and some

evaporates into the hot summer air. Drip irrigation is the

typical solution to this problem, but it's far from my favorite since

turbid water messes up the system in short order, you have to use lots

of expensive, plastic hoses and replace them often, and drip irrigation

works much better with row crops than with beds. Pitcher

irrigation is a more

permanent solution, but one that only works on a very small scale and

is labor-intensive. I'm still pondering a more efficient watering

option appropriate to our vegetable garden layout.

Meanwhile, there's always

mulch! Mulching around your plants cools the soil surface and

keeps water from evaporating away, so there's more water available for

your plants and you don't have to irrigate as often. Adding

organic matter to your soil with cover crops and compost will also make

watering less essential every year since this black gold acts like a

sponge, grabbing excess water during heavy rains and then releasing it

to plant roots on demand.

Meanwhile, there's always

mulch! Mulching around your plants cools the soil surface and

keeps water from evaporating away, so there's more water available for

your plants and you don't have to irrigate as often. Adding

organic matter to your soil with cover crops and compost will also make

watering less essential every year since this black gold acts like a

sponge, grabbing excess water during heavy rains and then releasing it

to plant roots on demand.

What watering system do

you use in your garden? Why did you choose it and what do you

love and hate about it? I'm especially curious to hear from

large-scale, no-till gardeners, of course, but everyone should feel

free to chime in!

Our

tomato plants are on a downward decline, but I think they still look

great.

Our

tomato plants are on a downward decline, but I think they still look

great.

Anna says we're getting close

to meeting our goal of enough soups and sauces to get us through till

next year.

The plan is to dry most of

the excess and make enough ketchup to last the rest of this year

and most of 2012.

Our Light

Sussex chicks are

voracious. They're currently in our tiniest pasture, but I

thought for sure it would last them multiple weeks since the chicks

aren't even fully feathered. Instead, it looks like they'll need

fresh forage in less than a week.

Our Light

Sussex chicks are

voracious. They're currently in our tiniest pasture, but I

thought for sure it would last them multiple weeks since the chicks

aren't even fully feathered. Instead, it looks like they'll need

fresh forage in less than a week.

My original plan had

been to let Mark finish up the pasture running up the hill behind the

coop, but I really don't want to turn the chicks in there until they're

at least four or five weeks old --- that pasture lacks tender,

chick-friendly food and has too much predator pressure. The other

pasture attached to our chicks' coop was overgrazed by the Cuckoo Marans and has been seeded with

pasture plants that need some time to get established. What will

our Sussex chicks eat in the meantime?

My eyes turn to the

semi-frequently mowed berry and fruit tree areas that bracket our

vegetable gardens. There's lots of chick-friendly forage

available on the ground and the chicks aren't big enough to do too much

damage (especially since the mulch in these areas has rotted into the

ground and needs to be refreshed.) I've been wishing I could run

chickens in there to deal with some insect problems, and we're sick of

mowing. The problem is fencing and housing.

My eyes turn to the

semi-frequently mowed berry and fruit tree areas that bracket our

vegetable gardens. There's lots of chick-friendly forage

available on the ground and the chicks aren't big enough to do too much

damage (especially since the mulch in these areas has rotted into the

ground and needs to be refreshed.) I've been wishing I could run

chickens in there to deal with some insect problems, and we're sick of

mowing. The problem is fencing and housing.

We could use chicken

tractors, but I think our chicks

need a tighter coop for at least a few more weeks, and they're already too big

to fit all fourteen in a yard-size tractor. Instead, I'm

pondering several options:

We could use chicken

tractors, but I think our chicks

need a tighter coop for at least a few more weeks, and they're already too big

to fit all fourteen in a yard-size tractor. Instead, I'm

pondering several options:

- Temporary fencing using the existing coop. I figure it would take me and Mark less than an hour to toss up some fencing around the berries adjacent to the chicks' current pasture. We have extra pea trellis material on hand to use if the deer come calling and can rustle up enough of the lightweight fence posts that we use for trellis posts and tomato stakes. After the chicks eat up the groundcover between the berry bushes, we could move the fencing to make an avenue across the driveway and then surround parts of the forest garden. By the time the chicks eat all that, surely they'll be big enough to run up on the hill.

Permanent fencing and one or more new coops.

On the other hand, this time of year is a lull in our pasture

productivity, and we'll often want to have extra pasture areas.

So maybe it would be a good idea to fence these areas in

permanently? The problem there is that we'd have to build gates

(time consuming) and perhaps add one or more coops (even more time

consuming) since we wouldn't want permanent fencing crossing our

driveway. Plus, the area where the driveway ends in front of the

trailer is already pretty tight, and I'm not sure permanent fencing

along both sides of the driveway would be a good idea. On the

other hand, putting in the time to build permanent fences now would

save time in later years, and I suspect deer would be afraid to walk up

the driveway if it had fences on both sides.

Permanent fencing and one or more new coops.

On the other hand, this time of year is a lull in our pasture

productivity, and we'll often want to have extra pasture areas.

So maybe it would be a good idea to fence these areas in

permanently? The problem there is that we'd have to build gates

(time consuming) and perhaps add one or more coops (even more time

consuming) since we wouldn't want permanent fencing crossing our

driveway. Plus, the area where the driveway ends in front of the

trailer is already pretty tight, and I'm not sure permanent fencing

along both sides of the driveway would be a good idea. On the

other hand, putting in the time to build permanent fences now would

save time in later years, and I suspect deer would be afraid to walk up

the driveway if it had fences on both sides.

Portable coop with temporary

fencing. Another option would be to combine a portable

coop with temporary fencing, which would allow us to run the chicks all

the way over to the berry and tree area on the west side of the back

garden. The major bonus with pasturing this area is that we could

finally deal with some of the insects that hit our peach trees while

grazing more land that we're sick of mowing. The downside is that

a portable coop big enough for fourteen chickens would be heavy (and

harder to build than permanent coops.) Mark had an idea of making

a portable coop with two handles so it could be carried since dragging

definitely wouldn't be good enough in the tight spaces of our

yard. It almost seems simpler to just build an extra coop over

there if I want our chickens to graze that area.

Portable coop with temporary

fencing. Another option would be to combine a portable

coop with temporary fencing, which would allow us to run the chicks all

the way over to the berry and tree area on the west side of the back

garden. The major bonus with pasturing this area is that we could

finally deal with some of the insects that hit our peach trees while

grazing more land that we're sick of mowing. The downside is that

a portable coop big enough for fourteen chickens would be heavy (and

harder to build than permanent coops.) Mark had an idea of making

a portable coop with two handles so it could be carried since dragging

definitely wouldn't be good enough in the tight spaces of our

yard. It almost seems simpler to just build an extra coop over

there if I want our chickens to graze that area.

Any other ideas?

Additional pros and cons for the ideas above? At this instant,

I'm leaning toward temporary fencing around the berries to give us some

breathing space which we'd use to build permanent fencing around the

forest garden. Our butternuts need another week or so to finish

ripening anyway before we can take them off their dying vines.

But I'm always looking for better ideas.

Any other ideas?

Additional pros and cons for the ideas above? At this instant,

I'm leaning toward temporary fencing around the berries to give us some

breathing space which we'd use to build permanent fencing around the

forest garden. Our butternuts need another week or so to finish

ripening anyway before we can take them off their dying vines.

But I'm always looking for better ideas.

We were thrilled yesterday to

notice the first shiitake

mushrooms popping up.

These logs are mounted in the

ground like a fence post, which will hopefully allow each one to take

up as much water as it needs compared to our old

method of dipping each log in a small kiddie pool.

At least two of the logs are

still pumping out fruit, which makes me wonder if I need to sink the

other three logs a few inches deeper. It might be that those logs are

finished up. One amateur mistake we made in the beginning was soaking

some of them too long, which may have drowned the mycelium in the logs

that are now dormant. I think it depends on the condition of the log,

but now if we were still soaking we would be on the safe side and limit

the time to 12 hours.

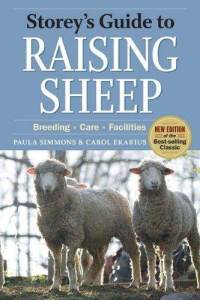

I've been researching sheep, both by talking with

shepherds and by reading Storey's

Guide to Raising Sheep, and I'm pretty sure these

fluffy livestock are not in our near future. On the plus side,

sheep are very efficient converters of plants into meat and if you

raise them on plenty of good pasture and let them lamb in late spring,

they need little or no supplemental feed or even housing. But the

trick is that sheep really need either high quality pasture (think:

beautiful green lawnlike expanses with lots of clover and other forbs

mixed in) or lots of space. Sheep just aren't going to be happy

with small, rough pastures like you find on a young homestead --- they

can handle small or rough, but not both.

I've been researching sheep, both by talking with

shepherds and by reading Storey's

Guide to Raising Sheep, and I'm pretty sure these

fluffy livestock are not in our near future. On the plus side,

sheep are very efficient converters of plants into meat and if you

raise them on plenty of good pasture and let them lamb in late spring,

they need little or no supplemental feed or even housing. But the

trick is that sheep really need either high quality pasture (think:

beautiful green lawnlike expanses with lots of clover and other forbs

mixed in) or lots of space. Sheep just aren't going to be happy

with small, rough pastures like you find on a young homestead --- they

can handle small or rough, but not both.

That said, established

homesteads and farms can often benefit from sheep. These critters

are very good at:

Grazing large expanses of

high and dry, subprime pasture that can't be used for anything

else without eroding away.

Grazing large expanses of

high and dry, subprime pasture that can't be used for anything

else without eroding away.- Keeping weeds down in established orchards, vineyards, and Christmas tree plantations. Just make sure you have other pastures to turn the flock into when young growth is present on the plants you care about and use miniature sheep if the trees are short.

- Maintaining well-sodded existing pastures. If you move onto a farm with lots of pastures that are quickly going to weeds, sheep could be a good answer to your mowing problem.

- Mixing in with larger grazers to eat the forbs that cows and horses don't prefer.

If you're trying to run

a flock of sheep with as few inputs as possible on poorer pasture, you

should stick to good foraging breeds. The ones listed in Storey's

Guide to Raising Sheep are Barbados Blackbelly, Black Welsh

Mountain, Border Cheviot (and, presumably, the related Miniature

Cheviot), California Red, Canadian Arcott, Debouillet, Gulf Coast

Native, Hog Island, Icelandic, Karakul, Katahdin (aka Hair Sheep),

Navajo-Churro, Panama, Polypay, Rambouillet, Romanov, Romney, Santa

Cruz, Scottish Blackface, Shetland, Soay, St. Croix, Targhee, Tunis,

and Wiltshire Horn. That said, even this book's sheep-loving

authors recommend that you get a goat if your pastures are overgrown

with brush. They explain that excellent foraging sheep breeds

will eat the leaves on the trees, but won't go after the twigs.

I think that if our homestead

was ever established enough that we felt it had sheep-friendly

pastures, we'd follow our neighbors' lead and get full size Hair

Sheep. The more I read about sheep, the more sheering sounds like

a hassle, especially since sheep are reputed to be skittish --- I can

just imagine trying to sheer our half-tame cat, Strider, and am not

relishing the image. Hair Sheep don't need to be sheered since

they naturally shed their hair, and they are also excellent foragers,

are docile and hardy, and lamb easily. Plus, since lots of people

in our county raise them, we would be able to keep just a couple of

ewes and rent a ram when needed.

I think that if our homestead

was ever established enough that we felt it had sheep-friendly

pastures, we'd follow our neighbors' lead and get full size Hair

Sheep. The more I read about sheep, the more sheering sounds like

a hassle, especially since sheep are reputed to be skittish --- I can

just imagine trying to sheer our half-tame cat, Strider, and am not

relishing the image. Hair Sheep don't need to be sheered since

they naturally shed their hair, and they are also excellent foragers,

are docile and hardy, and lamb easily. Plus, since lots of people

in our county raise them, we would be able to keep just a couple of

ewes and rent a ram when needed.

The other point against

becoming a shepherd even if we had excellent pastures and steered clear

of sheering is that I'm not sure they mesh with our land and

lifestyle. As one of our readers mentioned, sheep are extremely

prone to internal parasites, and most of these parasites thrive in low,

wet areas --- sounds like our farm. Another big problem with

sheep is that they often need help lambing if you don't want to risk

the mother and/or lamb dying a premature death. That means

shepherds spend a lot of wakeful nights out with the sheep, and Mark

can attest to the fact that I'm not a pleasant person if I don't get my

nine hours of sleep every night. Maybe we'll just stick to buying

lamb from Megan?

As soon as we feel the

first signs of fall, my academic inclinations start tickling my brain

and I want to research this, that, and the other. Sharing my

findings with you all on our blog firms up my understanding of what I

read (and also files it away in an easily searchable format), but I

sometimes wonder how you all like these infodumps. Time for a

short survey!

My research posts often

jumpstart experiments, but they are also untried information. Do

you mind the lack of personal info in the posts?

Sometimes I write about

my research in five short posts --- a lunchtime series --- while other

times I mash it all together into one long post. Which do you

prefer?

Lately, some of my

research has been channeled into our Weekend

Homesteader

series. Even though I offer a free pdf copy to any Walden Effect

reader who emails me, I know that might feel like too much

trouble. What do you think?

Most of my chicken

related research gets fed into my chicken blog and then I try to remember

to sum up the most important points over here at least once a year. Do

you mind missing that information your daily Walden Effect read?

Thanks for taking the

time to answer the poll or comment below!

It only took Anna and me about

20 minutes to set up 100 feet of the experimental, temporary chick

fencing this morning.

The soft,

plastic green material was a dream to handle compared to the hard,

metal chicken wire.

I've got a feeling this new

temporary chicken fencing method is going to become part of our future

pasturing poultry routine.

The fall garden could

use some weeding, but this week is the last call for planting oats

as a cover crop in

our climate, so the weeds will have to wait.

I find it hard to

believe that I will have used up the whole 48 pound bag of oat seeds by

the end of the week. The bag has already seeded 26 garden beds,

one of our larger chicken pastures, and will be used to plant another

heaping handful of beds in the next few days. I guess weevils won't be a problem this

year! I'm already drooling over all of the homegrown organic

matter and next year's lower weeding pressure.

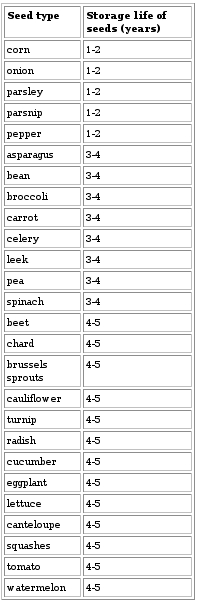

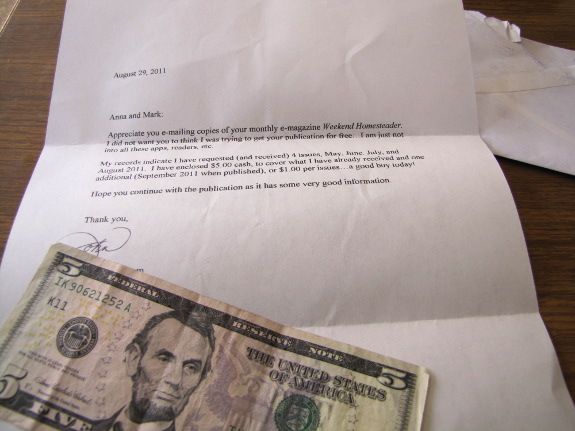

Even without setting foot in the

garden, you can save money by taking

better care of those half full seed packets you bought in the

spring. Nearly all vegetable seeds will last at least two years,

and many are viable for much longer. The chart to the right shows

the

storage life of many types of vegetable seeds under optimal conditions.

Even without setting foot in the

garden, you can save money by taking

better care of those half full seed packets you bought in the

spring. Nearly all vegetable seeds will last at least two years,

and many are viable for much longer. The chart to the right shows

the

storage life of many types of vegetable seeds under optimal conditions.

The trick to giving your

seeds as much longevity as possible is to keep water, heat, and light

at bay.

An air-tight box with cardboard dividers will keep your seeds safe and

organized, especially if you throw in a few packets of desiccant to

soak up excess moisture. To maximize shelf life, store your box

in

the freezer, garage, basement, or in another cool, dark place.

Once you optimize your

seed storage

tactics, you might be able to save yet more money by buying the

larger, value packs of many seed varieties, counting on the seeds

lasting for two or three growing seasons.

Excerpted

from the Seed Saving chapter of Weekend

Homesteader: September.

Still not sure how old it is

when baby chicks start roosting instead of crowding together in a

corner, but this new baby sized roost should do the job when they're

ready for it.

We abruptly shifted into fall

mode a week or two ago. Cool, wet weather slows down the

vegetable garden considerably, but sends mushrooms popping out of logs

and stumps. Time to check on all of our experiments!

We abruptly shifted into fall

mode a week or two ago. Cool, wet weather slows down the

vegetable garden considerably, but sends mushrooms popping out of logs

and stumps. Time to check on all of our experiments!

Our oldest mushroom

experiment is a magnolia

stump that we

inoculated with homegrown

oyster mushroom spawn

eleven months ago. (We inoculated a box-elder stump with more

homegrown spawn this past spring.) I've read a lot about using

mushrooms to break down stumps, but I think we're going to have do some

more experimenting since I haven't seen any signs of life and think I

should have by now. The trouble is that we cut down a fresh tree

to make the stump so that it wouldn't already be colonized with "weed"

fungi, but the tree vigorously sent up new shoots! Living trees

are able to fight off invading fungi, so it's possible that we need to

find a way to kill stumps before inoculating them with spawn.

Alternatively, it might just take longer for mushrooms to pop out of a

stump compared to a log --- after all, the mycelium has to colonize all

of the roots as well as the aboveground portion of the tree before it

will make mushrooms. We'll wait and see.

I'm pretty happy with our mushroom

totems since we harvested a big bowl full of shiitakes

Monday. True, we

didn't have any mushrooms all summer since the totem method lets our

fungi send out fruiting bodies more seasonally when weather conditions

are right. But the truth is that I've spent a lot of effort in

the past soaking mushroom logs and getting no results during the heat

of summer, and we certainly don't lack for fresh garden produce while

the mushroom totems take the summer off. I suspect mushroom

totems will last longer than the forced fruiting method of soaked

logs too.

I'm pretty happy with our mushroom

totems since we harvested a big bowl full of shiitakes

Monday. True, we

didn't have any mushrooms all summer since the totem method lets our

fungi send out fruiting bodies more seasonally when weather conditions

are right. But the truth is that I've spent a lot of effort in

the past soaking mushroom logs and getting no results during the heat

of summer, and we certainly don't lack for fresh garden produce while

the mushroom totems take the summer off. I suspect mushroom

totems will last longer than the forced fruiting method of soaked

logs too.

We're still waiting for

results on other experiments, like the new King

Stropharia bed we

started this spring and the mushroom rafts that are overgrown with

weeds and need to be weedwhacked before we can see if they're

fruiting. I'll report back when we know more, but right now we're

just enjoying our flush of shiitakes.

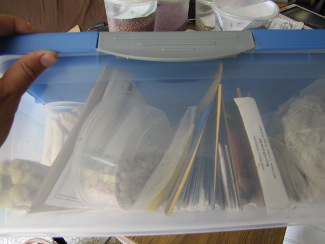

A huge thank you to John, who

sent me my first piece of author fan mail (along with a $5 bill.)

I love emails and comments, but I have to admit that knowing someone

went to the trouble of printing out a note and putting it in an

envelope made my day.

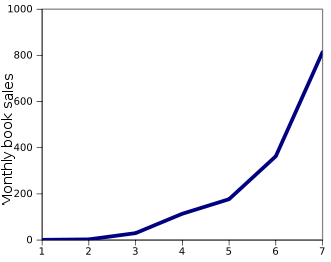

I don't want you to think

that

there are strings attached with the pdf copies I email for free to our

readers, though. I appreciate every reader of our ebooks, whether

they splurge to plop down 99 cents on Amazon or just ask for a free

copy. I never would have imagined that seven months into my

Amazon adventure, I'd be selling nearly a thousand copies a month ---

that's all due to you telling your friends and leaving glowing reviews

on Amazon. So thank you to all

of our other readers too! It's your enthusiasm that keeps us

writing.

I don't want you to think

that

there are strings attached with the pdf copies I email for free to our

readers, though. I appreciate every reader of our ebooks, whether

they splurge to plop down 99 cents on Amazon or just ask for a free

copy. I never would have imagined that seven months into my

Amazon adventure, I'd be selling nearly a thousand copies a month ---

that's all due to you telling your friends and leaving glowing reviews

on Amazon. So thank you to all

of our other readers too! It's your enthusiasm that keeps us

writing.

We've been having trouble

with Lucy breaking her way through the chicken wire to get to an egg or

food scraps thrown down for the flock.

I thought the Zareba

K9 electric fence controller fixed this problem for good last year

when I surrounded the first chicken pasture with electric wire and

watched her learn a shocking lesson on why it's important to stay away

from our poultry fence.

This year I only strung up

about 12 feet of wire within two small stakes for pasture #4 because I had a pretty

strong feeling she might try to re-enter through a recent hole she

chewed and we only half fixed. It only took a few minutes for her bad

side to take over and try another unauthorized entry.

Zap!

She didn't jump quite as high

as the first time, but it's obvious she got the message.

Tuesday was a

bittersweet day --- we killed the two hens surviving from our initial

flock of Golden Comets, purchased as adults in 2007. The photo

above shows some of those then-young ladies in an early chicken tractor

that July.

We started with twenty hens,

which was a crazy number --- we had moved to the farm not long before

and soon the few local people we knew didn't even want free eggs anymore. Two hens

died of heat exhaustion when their old fashioned waterer spilled (the

impetus for Mark's chicken waterer invention), and we gave

twelve away to my father to slim down the flock even more.

We started with twenty hens,

which was a crazy number --- we had moved to the farm not long before

and soon the few local people we knew didn't even want free eggs anymore. Two hens

died of heat exhaustion when their old fashioned waterer spilled (the

impetus for Mark's chicken waterer invention), and we gave

twelve away to my father to slim down the flock even more.

Slowly, four more

chickens bit the dust. One was a casualty of us thinking we could

keep a rooster in a chicken tractor --- he overmated our hens

mercilessly and one girl was too injured to survive. Another died

last winter when her old bones could no longer take the cold. And

to be honest I can't remember what happened to the other two.

I've written before about why

you can't expect to raise chickens for eggs and not get your hands

bloody, but I guess

I just didn't feel like my words applied to these old girls. They

were our wiliest hens, the first to come running when I called them to

a new pasture (and the first to find a hole in the fence.) When

people came to interview us about our chicken waterer, all I had to do

was tap the chicken nipples and our old Golden Comets would obediently

trot over and drink, whether they were thirsty or not.

I've written before about why

you can't expect to raise chickens for eggs and not get your hands

bloody, but I guess

I just didn't feel like my words applied to these old girls. They

were our wiliest hens, the first to come running when I called them to

a new pasture (and the first to find a hole in the fence.) When

people came to interview us about our chicken waterer, all I had to do

was tap the chicken nipples and our old Golden Comets would obediently

trot over and drink, whether they were thirsty or not.

But they were also

laying very few eggs any more, at least after spring ended. Last

winter, we started having to buy eggs from the store to round out our

diet, and the old hens never really picked up steam even when warm

weather returned.

You just can't expect a

four and a half year old hen to repay your expenses of feeding her over

a hundred pounds of feed (at least $30) per year. And you also

have to figure in the wear and tear on the pasture (worst in winter)

and the fact that your old hens are  probably head of the flock and

get to eat the best food, leaving your better layers malnourished while

their elders get fat. So we bit the bullet and turned them into

dinner this week, along with a one-year-younger Golden Comet who was

also past her prime.

probably head of the flock and

get to eat the best food, leaving your better layers malnourished while

their elders get fat. So we bit the bullet and turned them into

dinner this week, along with a one-year-younger Golden Comet who was

also past her prime.

I'd gotten used to

slaughtering three month old broilers --- we've already processed 21

this year, and after the first few, I started enjoying chicken killing

day as a break from the hard work of the garden. But those

broilers were raised from birth with dinner in mind and they hadn't

really grown into their personalities yet. The Golden Comets felt

different. Even though we hadn't named them, they almost felt

like pets.

And yet, I can almost

feel the pasture breathe a sigh of relief. Three fewer chickens

to scratch up the turf! And this year's pullets and cockerel seem

thrilled to have moved up a notch on the totem pole --- access to

scraps! It isn't always easy to do the right thing, but I'm glad

we didn't let our farm turn into a rest home for chickens.

This old picture of our very first chicken

tractor makes me cringe today.

Even though it's twice the

square footage per bird that Joel Salatin and other sources on the

internet use, it feels too crowded and I would only put 2 full sized birds in it

today.

See that white plastic I used

for a covering? It was filtering enough light to make the chickens stop

laying eggs. It took us weeks to figure that out.

The nest boxes really needed

an easy access hatch and that ancient, old fashioned, gravity waterer

was exasperating.

I like to do a

full-scale analysis of the honey situation in each hive at this time of

year so that I know whether the bees need help preparing for

winter. That means delving down into the brood box to count

frames of capped honey, which sends spirals of confused foragers

circling above my head. The video really doesn't do the situation

justice --- when you're in the middle of it, it feels a bit like

standing in the middle of five lanes of speeding traffic.

In the past, I've been

terrified of this cloud of buzzing bees when they reach their

population peak in late summer. I usually ended up jerking around

and getting stung, but last year Mark talked me into getting a bee jacket. I was surprised how a

little bit of protection increased my confidence enough that I was able

to realize the bees were just confused by losing access to the hive,

not angry. Sure enough, with calm movements, nobody even stung my

protective clothing.

So how were the honey

stores? Lower than I would like, partly because when you split hives you set them back, and

partly because of weird weather --- too much rain kept the bees cooped

up during certain periods, then too much dry made later nectar flows

sparse. The mother hive currently has 30 pounds of capped honey

and the daughter hive has 12 pounds, less than they had a month ago and

far short of our goal of 50

to 60 pounds.

That said, there's a lot of nectar dehydrating that I didn't count, so

hopefully at my next inspection, the mother hive (at least) will be in

the clear. I may have to feed the daughter sugar water to fill up

her larder.

Last night our problem

deer came in and nibbled on this buggy swiss chard.

Version 2.0 of the electric

deer zapper takes a lesson from the first generation and stays

clear of possible

leaf contact.

I learned to milk a goat

Friday --- a huge thank you to Megan and

Erek, who took time

out of their hectic harvest-time schedule to give us personalized

attention! Thank you to the duo of Saanen does, too, who waited

an extra hour with full udders so that Mark and I didn't have to get up

quite so far before dawn. (And thank you to Mark, who continues

to humor my goat obsession, hoping I'll grow out of it.)

I learned to milk a goat

Friday --- a huge thank you to Megan and

Erek, who took time

out of their hectic harvest-time schedule to give us personalized

attention! Thank you to the duo of Saanen does, too, who waited

an extra hour with full udders so that Mark and I didn't have to get up

quite so far before dawn. (And thank you to Mark, who continues

to humor my goat obsession, hoping I'll grow out of it.)

Milking a goat is harder

than it looks, but I can tell that the knack is quite learnable.

Megan milked at the speed of light, and I managed to get some good

squirts after a while. Those goats were far more patient than I