archives for 08/2011

I'm

bound and determined to grow

our onions from seed rather than sets

because it costs much less and the onions will store through the winter

rather than giving up the ghost in late fall. One year, I had a

beautiful harvest from seed, but the next two years I got just a

few small onions. So this spring, I decided to try out several

different methods to figure out the simplest way to grow onions

effectively from seed.

I'm

bound and determined to grow

our onions from seed rather than sets

because it costs much less and the onions will store through the winter

rather than giving up the ghost in late fall. One year, I had a

beautiful harvest from seed, but the next two years I got just a

few small onions. So this spring, I decided to try out several

different methods to figure out the simplest way to grow onions

effectively from seed.

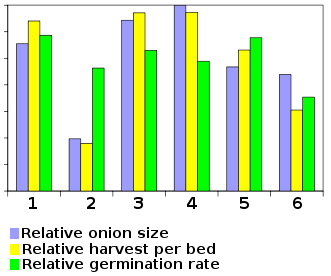

Here are the six

"treatments" I used in my 2011 onion experiment:

- 1. Early start with biochar under a quick hoop --- Direct-seeded on February 18 into soil treated with biochar under a quick hoop

- 2. Early start under a quick hoop

--- Just like above, but no biochar

- 3. Transplant into quick hoop

late --- Started indoors in February, then transplanted into a

quick hoop on March 8

- 4. Transplant into bare soil late

--- Same as above, but transplanted into soil not covered by a quick

hoop

- 5. Direct seeded into quick hoop

late --- Started directly under a quick hoop on March 8

- 6. Direct seeded into bare soil late --- Started directly into bare soil on March 8

It

looks like the pros who tell you to start your onions inside and then

transplant them are right since treatments 3 and 4 are the clear

winners. (It doesn't seem to matter whether you transplant into a

quick hoop or not.) However, I was interested to see that if

you're lazy and don't like starting seeds inside, you can get results

nearly as good by direct-seeding into biochar-doctored soil under a

quick hoop at the same time you would have started your onions

inside.

My sample size for that treatment was extremely small (half of a bed),

so I'd hate to have anyone plan their entire year's onion harvest

around that observation, but it's definitely worth further

experimentation.

It

looks like the pros who tell you to start your onions inside and then

transplant them are right since treatments 3 and 4 are the clear

winners. (It doesn't seem to matter whether you transplant into a

quick hoop or not.) However, I was interested to see that if

you're lazy and don't like starting seeds inside, you can get results

nearly as good by direct-seeding into biochar-doctored soil under a

quick hoop at the same time you would have started your onions

inside.

My sample size for that treatment was extremely small (half of a bed),

so I'd hate to have anyone plan their entire year's onion harvest

around that observation, but it's definitely worth further

experimentation.

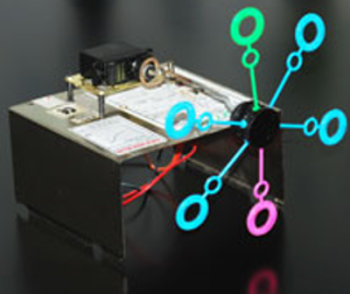

We've been having some

trouble with our

creek pump and the first

place we decided to upgrade was the quality of the wiring.

You can get a 250 foot roll

of outdoor grade 12 gauge 2 wire for around 138 dollars. Our stretch is

just over 300 feet, which required the above 4 dollar junction box.

The plan will be to silicone

up the ends and mount it on a tree above the point where the flood

waters usually get.

As I slowly work my way

beyond the seed-saving

basics, I'm starting

to realize that saving the seeds from the lone kale plant that

overwintered in my garden might not be a good idea. To understand

how many individuals you need to save healthy seeds, first you have to

delve into a bit of pollination biology.

As I slowly work my way

beyond the seed-saving

basics, I'm starting

to realize that saving the seeds from the lone kale plant that

overwintered in my garden might not be a good idea. To understand

how many individuals you need to save healthy seeds, first you have to

delve into a bit of pollination biology.

All plants fit somewhere

on the spectrum between strong inbreeders and strong outbreeders.

At the far inbreeding extreme lie plants like

tomato-leaved tomatoes, peas, and green beans, all of which have

flowers that make it extremely unlikely that an insect can get inside

to move pollen from one plant to another. These vegetables breed

with themselves as a matter of course, so they've worked the bad

recessive traits out of their populations. The pros recommend

saving seeds from at least 20 plants for strong inbreeder species, but

at the backyard scale, you can get away with just a few parent plants

(or sometimes even one.)

At

the opposite end of the spectrum, strong outbreeders (like most crucifers, swiss

chard, spinach, and beets) depend on getting pollen from another plant

to keep those recessive genes in check. You'll need around 80 to

100 individuals of these species in your garden to keep your seed

vigorous. If you save seeds from just a few individuals, next

year's plants will tend to be weaker and you'll eventually need to buy

seeds to reset your gene pool.

At

the opposite end of the spectrum, strong outbreeders (like most crucifers, swiss

chard, spinach, and beets) depend on getting pollen from another plant

to keep those recessive genes in check. You'll need around 80 to

100 individuals of these species in your garden to keep your seed

vigorous. If you save seeds from just a few individuals, next

year's plants will tend to be weaker and you'll eventually need to buy

seeds to reset your gene pool.

Most plants, of course,

lie somewhere in the middle, and there are also outbreeders (like most

cucurbits) that don't seem to show many problems even if you inbreed

them. You can download a free pdf

here that gives

recommended population sizes for most common vegetables. (The

website asks for your email address before download, but they haven't

sent me any spam. The file you want is A Seed

Saving Guide for Gardeners and Farmers.) Alternatively, if

you want to become a real seed-saving pro, I can't recommend Seed to Seed by Suzanne Ashworth highly

enough. This text made the very short list of book purchases in

our household for 2012 and has turned my dabbling in seed-saving into a

scientific endeavor.

It has been a very wet year.

The truck has been stuck most

of the summer.

Today we got close to getting

it on its way....but it's still stuck.

Maybe tomorrow will be dry

enough?

Although breadseed

poppies and opium poppies are in the same species and look very

similar, it's legal

to grow your own poppy seeds. Many websites will

tell you otherwise, though, so I was afraid to try my hand until I

found culinary poppy seeds being sold by a reputable seed company.

Growing poppies is

pretty simple, but I've learned a few tricks over the last couple of

years to increase yields. Unlike most ornamental poppies,

breadseed poppies aren't hardy enough to be seeded in the fall here in

zone 6, so you should instead scatter

the tiny seeds lightly on the soil surface in late February. If you live in a

warmer climate, you might get away with seeding in late autumn.

In 2010, I

sowed my seeds too far apart, so this year I planted more

heavily with the result that the seedlings formed a solid mass of green

across the bed by late April. That seems to have been overkill

--- fewer poppy seeds came up on a different bed, and these better

spaced seedlings resulted in much larger pods. I suspect that the

optimal distance between plants would be about four inches in a highly productive,

no-till garden, although extension service websites suggest 6 to 8 inch

spacing in a more conventional garden. If you're going to

overplant and thin, remove the extra seedlings by March or early April

--- I thinned later than I should have in the photo above.

In 2010, I

sowed my seeds too far apart, so this year I planted more

heavily with the result that the seedlings formed a solid mass of green

across the bed by late April. That seems to have been overkill

--- fewer poppy seeds came up on a different bed, and these better

spaced seedlings resulted in much larger pods. I suspect that the

optimal distance between plants would be about four inches in a highly productive,

no-till garden, although extension service websites suggest 6 to 8 inch

spacing in a more conventional garden. If you're going to

overplant and thin, remove the extra seedlings by March or early April

--- I thinned later than I should have in the photo above.

Your breadseed poppies

will be in full bloom in June, and your honeybees will love them.

Besides keeping the plants weeded, you don't have to do anything now

until the pods bulk up and then turn brown. At that point, snip off

the seed heads and bring them inside to dry.

Once the poppy heads are

entirely dry, tiny holes near the top of the pod will open, so it's

technically feasible to shake mature pods in a paper bag until all of

the seeds fall out. In practice, though, it's much more efficient

to pound the

pods to crush them, tear the heads open a little more with your

fingers, and then shake out the seeds from one pod at a time. This really doesn't

take very long if you've just grown a small patch of poppies.

Poppy seeds are too small to

winnow easily in front of a fan, but you can remove

nearly all of the bits of chaff by sending the seeds through a sifter. Let the seeds dry a

bit more in an open container, then seal them away for winter

treats. I've discovered that if I paint raw egg on the top of

homemade buns before their last rise, sprinkle on breadseed poppies,

then mash the seeds into the dough with the palm of my hand, nearly all

of the precious seeds stay in place and the plain old bread turns into

a treat. I figure this year's quarter cup harvest will last all

winter.

Poppy seeds are too small to

winnow easily in front of a fan, but you can remove

nearly all of the bits of chaff by sending the seeds through a sifter. Let the seeds dry a

bit more in an open container, then seal them away for winter

treats. I've discovered that if I paint raw egg on the top of

homemade buns before their last rise, sprinkle on breadseed poppies,

then mash the seeds into the dough with the palm of my hand, nearly all

of the precious seeds stay in place and the plain old bread turns into

a treat. I figure this year's quarter cup harvest will last all

winter.

We figured out the problem

was not with the wiring. I'm still glad we upgraded

to the 12 gauge wire,

which might help our new pump last longer.

The PVC

pipe I cut in half to hold the pump turned out to be a mistake. It

was allowing clay to accumulate next to the motor, which might have

been causing it to overheat and then to shut down. We deleted that

"improvement" today.

Another mistake might have been

upgrading the power from 1/2 horsepower to 3/4. We decided to take back

the 3/4 horsepower pump to Lowes and order a 1/2 horsepower pump from

our local hardware store. The new pump is made by Myers, and the step

down in power cost more than the Lowes 3/4 pump by about 50 dollars,

which I feel fine about. I'm confident our local guy is not gouging us

on the price and think that this may be a higher quality device.

Another mistake might have been

upgrading the power from 1/2 horsepower to 3/4. We decided to take back

the 3/4 horsepower pump to Lowes and order a 1/2 horsepower pump from

our local hardware store. The new pump is made by Myers, and the step

down in power cost more than the Lowes 3/4 pump by about 50 dollars,

which I feel fine about. I'm confident our local guy is not gouging us

on the price and think that this may be a higher quality device.

It sure is nice to not have a

garden full of thirsty vegetables.

The

bases of our okra flowers are currently loaded down with big, black

ants. What the insects are doing is beyond me.

The

bases of our okra flowers are currently loaded down with big, black

ants. What the insects are doing is beyond me.

My first thought was

that okra must be one of the plants with extrafloral nectaries, but a

google search turns up no useful hits on the combo of terms.

Instead, I learned that

fire ants will often feed on the base of okra bloom buds and cause the

flowers to abort. Luckily, these are neither fire ants nor bloom

buds, and my fruits seem to be setting fine.

A close look shows that

the ants aren't farming

aphids --- the other

way ants could harm okra. So what are they doing?

We bought a heavy duty

cutting blade for the new Stihl

FS-90R weedeater a few

weeks ago, but didn't read the small print and missed out on the collar

nut-thrust washer kit, which is mandatory if you want the blade to stay

bolted to the machine.

A 2 minute search on Ebay

turned up a nice guy who sells the kit for a bit over 10 dollars.

I'm very pleased with the

performance and cutting power. We let some of the forest

garden weeds get so high

that most of them were over my head. It only took a matter of minutes

to cut them down to ankle height.

Maybe next year we can cut

them before they get high enough to swallow 5 gallon buckets, which are

no match for what I've started calling the "Ninja Blade".

It's

tough to think long term when you're struggling to keep your short term

affairs in order. That could mean not putting money in your

retirement account because you can barely pay the bills. Or, in

the Walden Effect world, it could mean neglecting your perennials

because the annual garden is all you can handle.

The photo at the top of

this post shows our poor forest garden,

untouched since I halfway mulched a few areas in the winter.

Somewhere deep in that tangle, two baby apple trees, a baby peach, a

medium-sized nectarine, a plum, and a young hazel bush are hiding,

along with four tomato

plants, some perennial herbs, and a whole bunch of butternuts and

naked-seed

pumpkins. Okay, the last two aren't really hiding --- as annuals,

I gave them attention, so they are happily mulched, although starting

to run into the weeds.

The problem with this

area is that the mower can't get into it easily,

due to various experiments on my part combined with the remnants of a

brush pile. In southwest Virginia, unchecked weeds can grow

nearly twenty feet tall in just a few months --- and that's the annuals

that start from seed each spring. Enter Mark's

ninja

blade, combined with

my hand-weeding, mulching, and directing. ("No, don't cut

there! That's a tree! Cut this area again, lower!")

Four and a half man

hours later, the worst half of the forest garden has been

reclaimed. Now our seedling fruit trees won't have to compete

with ragweed taller than they are, with dodder sucking out their juices,

and with a general lack of love. Plus, I can delete the constant

low-level stress of worrying about the forest garden's inhabitants.

In retrospect, the one

thing I did right in the forest garden this year was planting

four tomatoes amid the trees. We love tomatoes so much that I

wasn't willing to risk any of the harvest, which is what finally pushed

me over the edge to putting forest garden renovation on the list.

Maybe that's a bit like setting up automatic, monthly direct deposits

into your retirement account?

A big thanks goes out to

Roland's scientific comment on my Tuesday post concerning our muddy

driveway and truck traction.

It helped in convincing Anna

that upgrading the back tires might increase traction without doing

further damage to the flood plain.

We got the truck free just

before sunset yesterday, and woke up early to visit our local tire

store and manure pile.

The next size up in tire and

traction cost us about 180 dollars. What also helped was moving the old

back tires to the front. This will help control the steering more,

which I think was a factor in driving out of the rut the last time it

got stuck.

I thought I was so clever

scooping seeds out of my monster

squash to save for

next year's garden. But once I rinsed the seeds off and let them

dry, it became evident that the flat, shriveled seeds weren't going to

be viable. What did I do wrong?

I thought I was so clever

scooping seeds out of my monster

squash to save for

next year's garden. But once I rinsed the seeds off and let them

dry, it became evident that the flat, shriveled seeds weren't going to

be viable. What did I do wrong?

Further research turned

up the information that I was skipping a step in my seed-saving

endeavor. First, I should have waited until the monster squash

was mature enough that I couldn't dent the skin with my fingernail

(which I discovered on my second try resulted in a more orange-colored

and warty fruit.) Next, remove the mature squash from the vine

and let it sit for two weeks before crushing the fruit under your heel

and scooping out the innards.

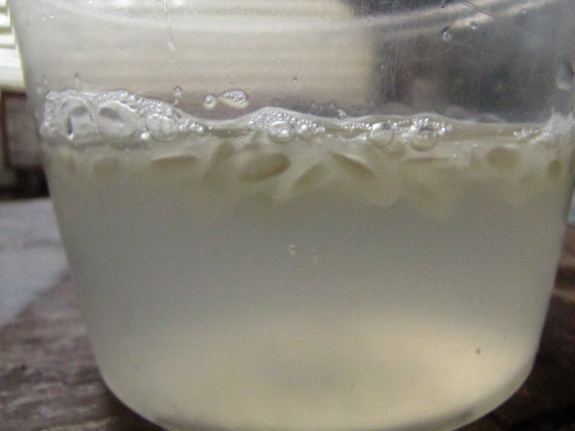

If you've done

everything right, the center of your summer squash should actually look

like

the inside of a pumpkin or other winter squash. The seeds will be

mixed in with strands of moist flesh, and there will be a significant

amount of air space. As you pull out the seeds, the squash guts

will smell just like the hollowed out center of your jack-o-lantern.

like

the inside of a pumpkin or other winter squash. The seeds will be

mixed in with strands of moist flesh, and there will be a significant

amount of air space. As you pull out the seeds, the squash guts

will smell just like the hollowed out center of your jack-o-lantern.

After rinsing my second

round of squash seeds and pouring off any that floated in water, I

ended up with the plump seeds shown here. Success at last!

The above picture of our

truck being parked in its designated spot represents a small victory

for us.

It's a hard thing to gauge,

but if I had to guess I would say the new

tires are giving us a 30 percent increase in traction and steering

control.

We've been able to haul in

some much needed manure, a load of firewood, and a new futon couch

during what must be our driest stretch of 2011 so far this year.

The next step will be to pick

up a load of big gravel to fill in some of the troubled spots...that is

if the rain can hold off for another few days.

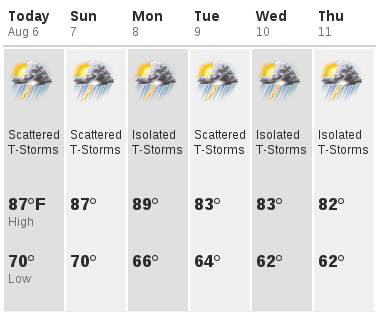

The ten day weather forecast

is

often what spurs us on to crazy exploits. Realizing that Friday

was our lone day of sun before the rain set back in, Mark donned his

work clothes at 8:30 Thursday evening and rocked the

truck out of what

remained of the mud.

Twelve hours later, he was in town replacing

the tires and then shoveling masses of horse manure into the truck's

bed.

The ten day weather forecast

is

often what spurs us on to crazy exploits. Realizing that Friday

was our lone day of sun before the rain set back in, Mark donned his

work clothes at 8:30 Thursday evening and rocked the

truck out of what

remained of the mud.

Twelve hours later, he was in town replacing

the tires and then shoveling masses of horse manure into the truck's

bed.

Meanwhile, I stayed home

to see what I could do about scavenging some

bricks from the old house's chimney and collecting bits of discarded

rip-rap to toss in the most muddy  part

of the driveway. Then I

rearranged the woodpile to put all of last year's wood in the front and

cleared a path so the truck could be driven around to the back.

part

of the driveway. Then I

rearranged the woodpile to put all of last year's wood in the front and

cleared a path so the truck could be driven around to the back.

Finally, I cooled down

from what was already

turning out to be a

scorcher. You see, I had a crazy, over-ambitious plan of not only

unloading the horse manure, but also hauling in the load of firewood

we'd had delivered to the other side of the creek, and I figured that

if Mark and I tag-teamed our mandatory cool-down periods, we could get

twice as much work done. So, in a rare show of housewifery, I met

him at the door with his AC running on high and a cup of ice water and

cold watermelon in my hand. He ate that (and his lunch) while I

unloaded the manure --- so much easier to shovel it out of a truck than

in.

The day had taken on a

dream-like quality by the time the two of us

heaved huge slabs of wood into a towering pile in the truck. We

filled the cab with chicken waterer  supplies

that had also been piling

up in the parking area and I walked home while Mark and the truck did

the work of about 100 people by transporting goods the third of a mile

to our trailer.

supplies

that had also been piling

up in the parking area and I walked home while Mark and the truck did

the work of about 100 people by transporting goods the third of a mile

to our trailer.

I made Mark go cool down

again while I unloaded the light boxes.

This was clearly a mistake --- I seem to know Mark's limitations better

than my own, and the afternoon sun was pounding on my hatted head

despite the lightness of my burden. By that evening, I would be

suffering from the early stages of heat exhaustion --- a pounding

headache, clammy skin, and nausea. But at the time I was running

on adrenaline --- look at all this biomass driven right to our doorstep!

Luckily, Mark thought the

suggestion that I unload the firewood by

myself was nuts, so he handed me wood off the truck while I obsessively

stacked it into neat rows, segregated from last year's bone dry wood

which we'll use first. I'm always amazed by the power of

teamwork, which in this case meant

that we unloaded the truck in

perhaps thirty minutes flat.

Luckily, Mark thought the

suggestion that I unload the firewood by

myself was nuts, so he handed me wood off the truck while I obsessively

stacked it into neat rows, segregated from last year's bone dry wood

which we'll use first. I'm always amazed by the power of

teamwork, which in this case meant

that we unloaded the truck in

perhaps thirty minutes flat.

"So, I was thinking," I

tentatively broached the subject of yet more

hauling. "I know you've been eying that futon..." Mark's

room was devoid of furniture save a bed, and he'd been wanting a futon

for months. There was no point in buying any furniture, though,

when we had no way of bringing it home. Maybe this was our

chance, if we could survive a few more hours driving to town?

Mark was game.

And that's how we ended

our Friday at 8:30 pm,

a truckload of manure, a truckload of wood, and a futon (and

wheelbarrrow) richer. I went to bed shortly thereafter with ice

on my head, but it was all worth it. Mental note --- when I

complain about us starting work late on dark winter mornings, I need to

remember the twelve hour summer days that preceded them.

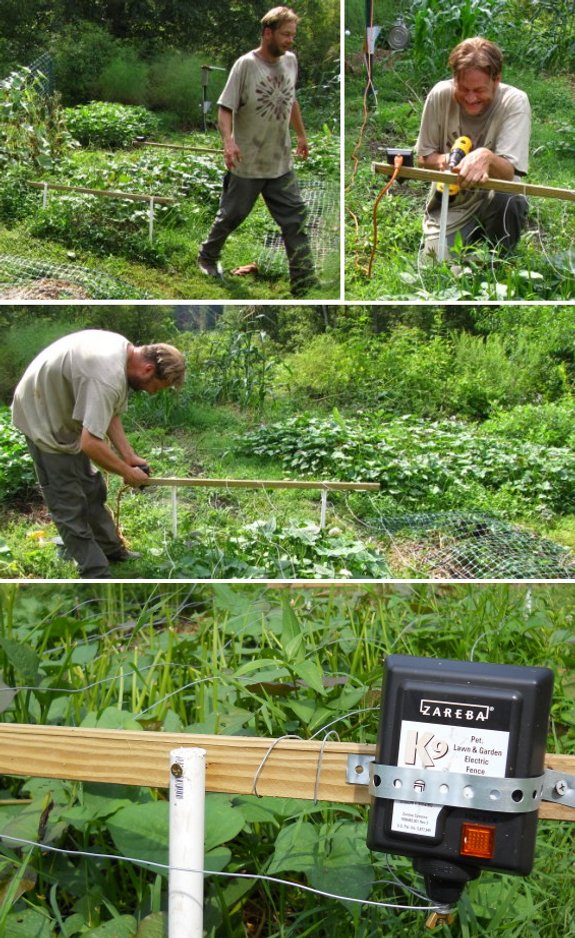

Anna noticed some additional

deer damage near the sweet potato leaves this morning.

Sigh.........

I noticed a mother deer with

two small ones yesterday near a neighbor's mail box when I was driving

back from the post office. They seemed more bold than most deer and

took a few seconds to scurry off into the woods where as most deer

around here bolt at the slightest hint of a car. I'm thinking it's the

same trio that's been attacking our garden since the 22

hour power outage we had last month.

We changed one of the mechanical

deer deterrent clangers

from a pet bowl to an old baking pan and Anna brushed up on her

shooting skills. If things get much worse we'll start taking turns

waking up early in hopes of ambushing the offending deer while at the

same time adding some venison to our winter meal plans.

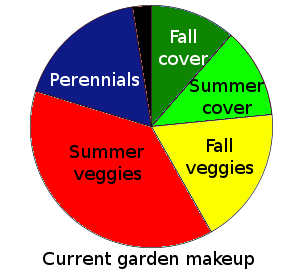

By

now, parts of your summer garden are probably toast. That early

sweet corn should be long gone, maybe you pulled out some buggy beans, and you're about to dig

your potatoes. Or perhaps you have trouble zones where the soil

wasn't good enough to support much of a crop and you're thinking about

writing that bed off entirely. Once you set aside some good

ground for your fall

garden, now's the

perfect time to plant the rest in winter cover crops --- they'll create

organic matter, prevent erosion, cut down on winter weed growth, and

add beauty to the winter garden.

By

now, parts of your summer garden are probably toast. That early

sweet corn should be long gone, maybe you pulled out some buggy beans, and you're about to dig

your potatoes. Or perhaps you have trouble zones where the soil

wasn't good enough to support much of a crop and you're thinking about

writing that bed off entirely. Once you set aside some good

ground for your fall

garden, now's the

perfect time to plant the rest in winter cover crops --- they'll create

organic matter, prevent erosion, cut down on winter weed growth, and

add beauty to the winter garden.

The

perfect winter cover crop for a no-till garden can handle problematic

soil conditions, will thrive in the fall and early winter, then

naturally dies back when the coldest part of winter hits. Here in

zone 6, I've found only two winners that really fit the bill --- oats and oilseed

radishes. Oats

have the advantage that they are available at my local feed store

(which means the seeds are dirt cheap) and the plants leave behind a

light mulch that will protect the soil until it's time to plant summer

vegetables. Oilseed radishes hold their own, though, by aerating

and adding organic matter deep in poor soil, then rotting fast enough

that I can plant spring vegetables directly behind them. After a

year of experimentation, I've decided that oilseed radishes will go

into the very poorest soil of my garden while oats will be planted

almost everywhere else.

The

perfect winter cover crop for a no-till garden can handle problematic

soil conditions, will thrive in the fall and early winter, then

naturally dies back when the coldest part of winter hits. Here in

zone 6, I've found only two winners that really fit the bill --- oats and oilseed

radishes. Oats

have the advantage that they are available at my local feed store

(which means the seeds are dirt cheap) and the plants leave behind a

light mulch that will protect the soil until it's time to plant summer

vegetables. Oilseed radishes hold their own, though, by aerating

and adding organic matter deep in poor soil, then rotting fast enough

that I can plant spring vegetables directly behind them. After a

year of experimentation, I've decided that oilseed radishes will go

into the very poorest soil of my garden while oats will be planted

almost everywhere else.

So, when do you plant winter

cover crops? Again, this will be climate specific, but I plant

oats betwen August 1 and September 15 and oilseed radishes between

August 1 and September 7. If you plant too late, your cover crops

won't do much good and you'll instead enter the next garden year with

lots of weeds. On the other hand, plant too early and your cover

crops might go to seed and produce weed problems of their own (although

you can stave this off with oats by mowing the mature plants.)

So, when do you plant winter

cover crops? Again, this will be climate specific, but I plant

oats betwen August 1 and September 15 and oilseed radishes between

August 1 and September 7. If you plant too late, your cover crops

won't do much good and you'll instead enter the next garden year with

lots of weeds. On the other hand, plant too early and your cover

crops might go to seed and produce weed problems of their own (although

you can stave this off with oats by mowing the mature plants.)

Unless you have fancy

equipment to do the work for you, cover crops aren't worth the extra

effort of seeding in rows. Instead, I've had good luck

broadcasting oat seeds on the soil surface and covering them with a

very light mulch of straw to keep the ground moist  while preventing seed

predation by our

intelligent sparrows and cardinals. Radish seeds are less tasty,

so I often toss them directly onto the soil surface with no further

care. (Do be aware that in really hot, dry weather, the radish

seedlings can burn to a crisp if planted this way.) A safer (but

more time-consuming method) for planting both is to rake

back the top half inch of soil, broadcast your seeds, and pull the soil

back overtop.

while preventing seed

predation by our

intelligent sparrows and cardinals. Radish seeds are less tasty,

so I often toss them directly onto the soil surface with no further

care. (Do be aware that in really hot, dry weather, the radish

seedlings can burn to a crisp if planted this way.) A safer (but

more time-consuming method) for planting both is to rake

back the top half inch of soil, broadcast your seeds, and pull the soil

back overtop.

There are several winter

cover crops that can be planted later than September 15, but I've found

that barley, crimson clover, and (especially) annual ryegrass are tough

to kill

without tilling.

I suspect that any cover crop that can be planted within a month of the

first frost date will be too cold hardy to die on its own over the

winter. For beginners who live in zone 6 or colder, I'd recommend

sticking to oats and oilseed radishes this year for a beautiful and

bountiful winter cover crop.

We've been liking our Kobalt

Neverflat wheelbarrow so much that we decided to get it a

companion.

The guy at the store said it

was a long shot, but if they spark within the first 90 days then you've

got at least a 20 percent chance at producing some viable hybrids. This

particular species has been known to have litters as high as 10 little

ones, but 5 is more common.

Of course we won't need that

many wheelbarrows if the coupling does happen, but I have a feeling it

won't be too difficult to find good homes for a handful of young Kobalts

ready to haul their way into a lucky gardener's heart.

The forest garden area we

renovated on Thursday

has been a major experimenting ground for me because I'm trying to find

a way to grow useful plants on highly degraded soil. Previous

owners had used this spot as a pasture, and I suspect they overgrazed

it so much that every bit of topsoil eroded away. As a result,

there's a gully leading from the forest garden down to the floodplain,

absolutely no topsoil above the bare clay remaining in  place, and a

very high water table. On the positive side, the spot gets good

sun and is close to our trailer, so it's easy to keep the deer

out. Clearly, the ground is worth renovating back into production.

place, and a

very high water table. On the positive side, the spot gets good

sun and is close to our trailer, so it's easy to keep the deer

out. Clearly, the ground is worth renovating back into production.

I'm slowly figuring out

ways to grow things in this extremely sub-prime

soil. The trick is to raise the plants' roots up high enough that

they don't drown while also adding enough organic matter and mulch that

the plants have something to eat and don't dry to a crisp in the summer

sun. Planting

trees in raised beds

works well for year one, but by year two the trees want to spread their

roots further, so I need to keep expanding the mound --- this winter's hugelkultur

donuts seem to have

been a good option in that regard.

Since there's a lot of

empty space between the young fruit trees, I've also been

experimenting with making instant raised beds out of a layer of

cardboard topped by a bunch of composted manure. I can plant

annual crops on these rich raised beds and get a return on my

investment in year one. Meanwhile, by attaching the vegetable

beds to my tree islands, I'm also giving my fruit trees room to

grow. This idea works great if you mulch the manure beds

immediately so the top doesn't crust up, then transplant in tomatoes or

direct-seed squash into small, mulch-free areas. Without mulch,

though, the cowpeas, field corn, and amaranth I planted in another bed

barely germinated (although pearl millet seems to be hardy enough that

even scattered on the manure surface, enough seeds sprouted to make

the stand pictured here.)

When Mark cut all of the

weeds I'd let grow up over our heads, I raked

some into piles alongside the tree beds for a new experiment. My

hope is that they'll rot down slowly enough that the greenery will act

like a kill mulch and smother weeds underneath. Meanwhile, the

composting weeds will add organic matter and height to the soil.

I even threw some firewood that was too punky to

split into the lowest spot for yet more height and organic matter.

The beauty of

permaculture is that every problem can be viewed as a

benefit. Yes, this part of the garden is extremely troubled, but

the high groundwater acts to subirrigate

my beds, keeping roots moist and the leaves dry. The tomatoes in

the forest garden are taller than the unwatered tomatoes in tomato

alley and less blighted than the tomatoes in the watered part of

the mule garden. Maybe I should plant all of my tomatoes here

next year?

1. Place submersible pump at

the bottom of a large trash can.

2. Hook modified garden hose

from pump to sprinkler.

3. Fill trash can with water

and scented soap.

4. Adjust timer so that pump

turns on for a short burst and off for maybe an hour.

The goal is to spook the offending deer with a fresh, unnatural scent.

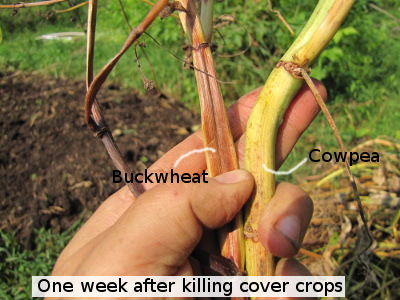

So you took my advice

and planted buckwheat and/or cowpeas as a quick

summer cover crop,

but you've actually got a longer fallow window than the cover crops

need. Once you start to see tiny fruits forming on the cover

crops (like the green triangles in the photo above), it's time to get

them out of there so that they don't set seeds and become a weed

problem.

Why not toss another round of

summer cover crop seeds on the ground before cutting, then let the

first cover crop act as a light mulch to promote germination of the

later planting? I tried out this method a week ago, and little

buckwheat seedlings are already poking up through the debris.

I'll let you know how solid of a stand I end up with, but if this

planting method works, it's definitely the easiest way of getting

summer cover crops established.

Why not toss another round of

summer cover crop seeds on the ground before cutting, then let the

first cover crop act as a light mulch to promote germination of the

later planting? I tried out this method a week ago, and little

buckwheat seedlings are already poking up through the debris.

I'll let you know how solid of a stand I end up with, but if this

planting method works, it's definitely the easiest way of getting

summer cover crops established.

The deer came back last night

and ate more sweet potato leaves.

We've now got a 110

volt surprise waiting for them when they return.

Cue Evil laugh.

As much as I swear by

Mark's deer deterrents, I'm coming to realize that

they're a bandaid. The ultimate solution to keeping deer out of

our garden is going to require no electricity, because power outages

have become our Achilles heel.

On the larger scale, I

think the solution is hunting. Unfortunately, the game laws (and local hunter

ethic) in our area are stacked in the favor of increasing the deer

population, so we're

unlikely to be able to solve our own problem by shooting a few deer.

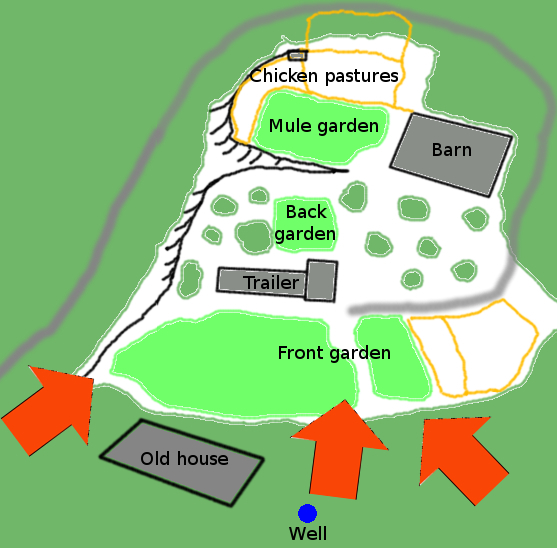

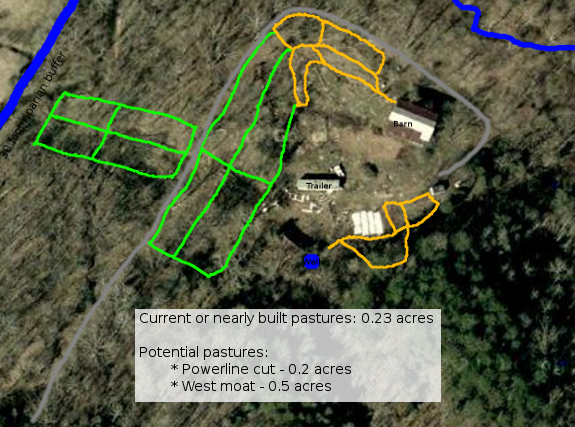

Instead, I think we need

to prevent the deer damage at a medium scale by considering where the

deer enter our garden. When we first moved in, the deer came from

all directions, but I've noticed that the mule and back gardens have

shown absolutely no signs of deer damage for the last year and a

half. Instead, the deer are only entering at the three locations

marked by arrows on the map above. So what are we doing right in

some places, and can we replicate it to save the beleaguered front

garden?

The reason the back and

mule gardens are untouched is because they are moated in. On the

north side, chicken pastures and the barn form a barrier that's too

uninteresting to deer to make it worth their while to cross. I'm

quite aware deer can easily leap a five foot fence if they want to, but

since nothing in the chicken pasture looks interesting and since we're

down there so often, they take the path of least resistance and stay

away. I've read permaculture books that call this strategy

building a "chicken moat."

The west side of the

back and front gardens is protected by an extremely steep slope.

Lucy has a path she sometimes takes down this escarpment when she's in

a big hurry, but so far, the steepness has made a good barrier to

deer. Again, path of least resistance.

On the east side of our

growing zones, the barn and another chicken pasture protect the

majority of the boundary. Three years ago, deer sometimes walked

up the driveway and into our domain, but I think some combination of

uninteresting food plants within the first few hundred feet combined

with our frequent activity in that zone keeps the deer away.

So our only real problem

now is to the south. If we could prevent the deer from walking

into that part of the garden, we would be protecting our entire

perimeter without electricity. But how?

Adding another chicken

pasture to moat off the southeast corner is already on the drawing

board, but I'm unwilling to pasture chickens within the watershed of

the well. As you can see in the aerial photo below, there's a

little hill between the south pastures and the well, which protects the

quality of our drinking water, but I'm leery of grazing chickens any

closer.

The jungle of weeds that

has grown up around the mostly-torn-down old house definitely makes the

deer feel safer when they come in from the south, so house removal is

on the to do list as well. But I think that even if the south

border was mown to remove all deer shelter, the garden would still look

enticing, especially since we don't walk up there very often. Any

ideas for a permaculture deer barrier that will protect the southwest

quadrant?

The deer came back the night

I installed the StinkMaster

smelly sprinkler system,

but they entered at a different spot, which might indicate a behavior

of avoidance to the smell zone.

One obvious problem is the soapy

water clogging up the sprinkler head. I tried switching to a hand

held shower unit and it still clogged, but at a slower rate.

We got a call from the game

warden yesterday and he gave us a 10 day kill permit. I'll save those

details for tomorrow's post.

If

forest garden enthusiasts are entirely honest, I think what we find

most intriguing is the idea of a semi-self-maintaining system that

gives you food with very little work once it's established. In

case I'm not the only lazy forest gardener out there, I thought I'd let

you know which plants really thrived on total

neglect (or outright

abuse) in my extremely

poor soil.

If

forest garden enthusiasts are entirely honest, I think what we find

most intriguing is the idea of a semi-self-maintaining system that

gives you food with very little work once it's established. In

case I'm not the only lazy forest gardener out there, I thought I'd let

you know which plants really thrived on total

neglect (or outright

abuse) in my extremely

poor soil.

Comfrey. I planted

comfrey directly into the ground, cut the leaves multiple times, let

Mark mow the plants to the ground, and then forgot about them for six

months until the

surrounding weeds were eight feet tall. When I came back in to

hand-weed the spot, I found the comfrey happily growing and blooming,

weed-free. The downside of comfrey, of course, is that you'll

never kill it so

that location will be home to comfrey forever.

But if you've got space far enough from fruit trees that it won't

compete

with the tree too much for nitrogen, comfrey is definitely a

neglected-forest-garden winner.

Fennel. I transplanted a

few fennel starts into another spot, again directly into the awful

soil. The fennel was run over by the truck, mowed to the ground

multiple times, and then ignored, but the plant kept popping back up

and even looked

so obviously cultivated that Mark started mowing around it. With

its deep taproot, fennel is probably tough to eradicate, but it doesn't

run like mint and does attract a lot of beneficial insects to its

flowers.

Mint. I know I'm

starting to sound like a broken record, but I transplanted some mint

into the poor soil and let Mark mow it down multiple times and drive

over it with the truck. The mint grew so happily that

it took over the nearby hugelkultur mound that I'd made for my

apple. That's the major downside of mint --- it's easier to

eradicate than comfrey, but spreads much more thoroughly if you don't

install a root barrier. I couldn't tell how much or if the mint

was competing with the tree for nutrients, but I ripped it out of the

immediate vicinity just in case.

Mint. I know I'm

starting to sound like a broken record, but I transplanted some mint

into the poor soil and let Mark mow it down multiple times and drive

over it with the truck. The mint grew so happily that

it took over the nearby hugelkultur mound that I'd made for my

apple. That's the major downside of mint --- it's easier to

eradicate than comfrey, but spreads much more thoroughly if you don't

install a root barrier. I couldn't tell how much or if the mint

was competing with the tree for nutrients, but I ripped it out of the

immediate vicinity just in case.

I think that these three

perennials are good candidates for renovating poor soil a

good distance from fruit trees. They all produce

copious organic matter while comfrey is also a dynamic accumulator of

silica, nitrogen, magnesium,

calcium, potassium, and iron and fennel is a dynamic accumulator of

sodium, sulfur and potassium. I suspect that the trick to using

them wisely is to map out the eventual spread of your fruit tree

canopies, then plant comfrey, mint, and fennel in the spaces where the

tree leaves will never reach (adding a root barrier if you're including

mint in the mix.) Trees

will spread their roots beyond the canopy, but by the time your trees

are mature enough to reach this intercanopy area, they roots will be

better able to compete and the understory weeds will have produced

enough good soil that there won't be such a fight over nutrients.

I wish I'd though of this before scattering the three willy nilly

throughout the forest garden!

1. Call the D.G.I.F. office

in the state capital. Did that on Monday.

2. Explain situation to

dispatcher who passes message along to the actual warden.

3. Wait.....and wait some

more....and then call again on Wednesday.

Our local game warden called

us back that same day to set up a time to meet. He was free and in the

area so I agreed to meet him out at the mailbox. He was very

professional and courteous and sort of interviewed me there in our

driveway. I guess I proved to him that I was an exasperated gardener and

not some blood thirsty hunter who couldn't wait til deer season

started. He decided to give me the permit without walking back to

actually inspect the damage and took some time to explain how a kill

permit works.

1. No Bucks!...that seemed to

be one of the more important distinctions.

2. It's the only time you are

legally allowed to use spotlights to hunt deer.

3. We've only got 10

days....and no hunting on Sunday.

I asked him why no hunting on

Sundays? He just shrugged and said "Something to do with the blue laws."

I imagined a scene of church pews being almost empty during hunting

season before these laws were enacted, which I guess is what would

prompt such a law.

The picture to the right here

is Anna's

very first deer back in 2009. I have a feeling we'll be carrying her second home

within the next 9 days.

This would have been a

bumper year for peaches...if brown rot hadn't hit. Here's what

our extension

service website has

to say about it:

During warm, wet summers, the

fungus that causes brown rot infects stone fruits starting at the

blossom stage, continuing through cankers on twigs, and culminating in

peaches that rot before they fully ripen. We lost every peach

(save one) on our younger peach tree due to endless rain, and even

though I dutifully picked rotting peaches off the kitchen peach every

week, brown rot took nearly the entire crop there too. I ended up

with a five gallon bucket of rotten peaches, about two quarts of

semi-ripe peaches to turn into fruit leather, and just enough ripe

fruits for one dessert.

During warm, wet summers, the

fungus that causes brown rot infects stone fruits starting at the

blossom stage, continuing through cankers on twigs, and culminating in

peaches that rot before they fully ripen. We lost every peach

(save one) on our younger peach tree due to endless rain, and even

though I dutifully picked rotting peaches off the kitchen peach every

week, brown rot took nearly the entire crop there too. I ended up

with a five gallon bucket of rotten peaches, about two quarts of

semi-ripe peaches to turn into fruit leather, and just enough ripe

fruits for one dessert.Since I'm not willing to resort to fungicides, it may turn out that we simply can't ripen peaches during wet years, but there are some tricks I can try to at least lessen future catastrophes.

- Keep the leaves dry. I already prune my peaches to the open center system, which helps the leaves dry off as fast as possible, and I can't do anything about the rain. But I am going to tweak our sprinkler arrangements since they currently hit a little bit of our peach trees when I water the garden.

- Sanitation. The

fungus overwinters in so-called mummies --- dried up fruit that sit on

the tree or on the ground. I do my best to remove all bad fruits,

but I think I'm going to find a way to turn chickens under our peaches

for a little while right after harvest to catch anything I miss.

- Work harder to prevent insect

damage. Unripe peaches are usually safe from brown rot,

but not if their protective skin has been damaged by insects. Oriental

fruit moth larvae were a huge problem in our peaches last year, and

even though I clipped off injured twigs and thinned out infested

fruits, some still got past my radar. (I'd say my sanitation

practices reduced the insect damage by about 75%.) I'm hoping

that mini chicken pastures will help with this problem as well since

the moths overwinter in debris on the ground and chickens love looking

for insects under mulch.

- Remove the most susceptible trees. Nectarines tend to be more prone to brown rot than peaches are, and in retrospect, that's probably why our nectarine --- covered with flowers this past spring --- set no fruit. The dwarf cherry that set twelve fruits and then had them all rot before ripening also did its part to let the fungus keep reproducing all spring. Neither of these trees is happy here, so I'm going to finally rip them out so that they can't serve as reservoirs of disease that will later infect my good trees.

- Give my fruit trees less compost.

One study suggests that too much nitrogen can make trees more prone to

infection by brown rot. Perhaps I need to back off on the compost?

Cleaned out the StinkMaster

for another round of experimentation.

The next artificial scent I

plan to try is the above Classic Spash,

which can be found at local Dollar General stores for $1.50.

I'll post about the results

sometime next week once I've tested the clogibility of the new After

Shave, which in my opinion has a much more repulsive odor than the Irish Spring

soap.

Camp

out beside the deer

entrance to garden.

Camp

out beside the deer

entrance to garden.

Reality: I adore sleeping close to the earth, but miss spending evenings with my husband. Nights with Lucy nearby aren't nearly as much fun, and I wake up every time she moves thinking she's a deer. And --- about the hunting idea --- how am I going to shoot a deer in the dark again? On the plus side, the deer stop using this path and the garden is momentarily safe.

Carry

the gun while walking Lucy.

Reality: The only deer I see are far away in the neighbor's hay field. I'm unwilling to trespass and they're too distant to hit anyway.

Hang out on the plateau overlooking the

floodplain in the evening.

Hang out on the plateau overlooking the

floodplain in the evening.

Reality: No deer pass by. When I pay more attention, I notice that all tracks in the area are at least a week old.

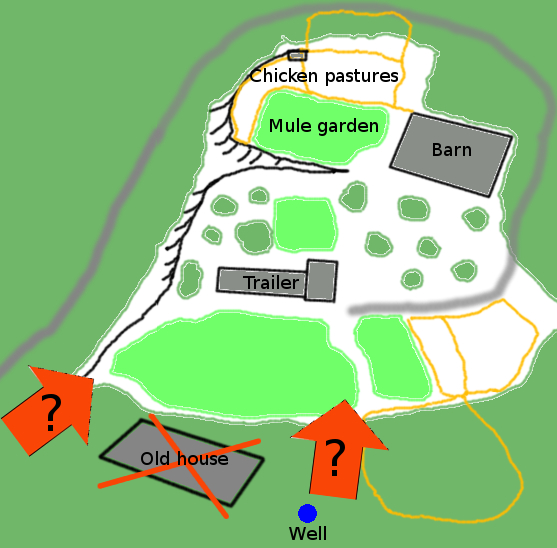

Find out where the deer actually go and stake

out the spot with a book.

Find out where the deer actually go and stake

out the spot with a book.

Reality: Lucy follows me and makes a ruckus for half an hour, but she finally settles down. By the time I'm well engrossed in my book, I barely notice the two does walking down the trail toward me. They snort in alarm and my adrenaline turns me stupid. Rather than waiting in hopes they'll come closer or at least turn broadside so I'll have more of a target, I fire from my lounging bookworm position at one deer's front-on chest...and miss.

I really am making

progress...or so I tell myself. At least I finally shot at a deer

on my third hunting day. Now, if I can just shoot at a deer and hit it. Do you think they'll

come back to that same spot twenty four hours later?

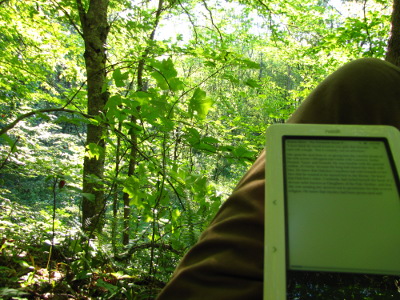

Roland made a good point

yesterday about the StinkMaster

After Shave being diluted in water, which got me to thinking of an

alternative way of dispersing liquids through the atmosphere.

Roland made a good point

yesterday about the StinkMaster

After Shave being diluted in water, which got me to thinking of an

alternative way of dispersing liquids through the atmosphere.

Bubbles?

BionicMechanic.com has the

details for building an automatic bubble machine for very little money.

I'm not sure how much

of a scare factor the bubbles might have on the deer, but if such a

machine was set up on a timer like the StinkMaster, then maybe an hourly bubble show

would be enough to keep a repulsive scent lingering in the area.

I

used to hate spaghetti night when I was a kid. My parents made

the sauce from scratch, and the result was both watery and chunky ---

pretty much par for the course with homemade tomato sauces. When

I was finally introduced to storebought spaghetti sauce, I fell in

love. Three years of trial and error later, I finally figured out

how to make a full-bodied tomato sauce with homegrown tomatoes that

tastes even better than the stuff in the jar and is just as good for

you as the kind my parents made.

I

used to hate spaghetti night when I was a kid. My parents made

the sauce from scratch, and the result was both watery and chunky ---

pretty much par for the course with homemade tomato sauces. When

I was finally introduced to storebought spaghetti sauce, I fell in

love. Three years of trial and error later, I finally figured out

how to make a full-bodied tomato sauce with homegrown tomatoes that

tastes even better than the stuff in the jar and is just as good for

you as the kind my parents made.

Start

with roma tomatoes.

There are two main types of tomatoes when it comes to cooking --- romas

and everything else. Roma tomatoes have less water and more flesh

than any other kind of tomato, and they also tend to have few enough

seeds that I make my sauces with skins and seeds in. It's okay to

include some extra slicers and tommy-toes as long as the romas

overpower their wateriness and seediness.

Get out your biggest skillet. The trick to making a

spaghetti sauce that turns out creamy and not watery is to let the

pectin in the tomatoes do its magic --- you're basically making

tomato jam. To that end, you're in a race against the naturally

occurring enzymes that start to break down the pectin in your tomato as

soon as the flesh is cut. The enzymes are activated by air and

then denatured (made inactive) by heat, so you need to keep your

tomatoes intact until the last minute, then heat the whole mass of

tomatoes up as fast as possible. Thus the skillet --- more

surface area on the burner means your sauce comes to a boil

faster. Plus, there's more surface area through which excess

water can cook off.

Get out your biggest skillet. The trick to making a

spaghetti sauce that turns out creamy and not watery is to let the

pectin in the tomatoes do its magic --- you're basically making

tomato jam. To that end, you're in a race against the naturally

occurring enzymes that start to break down the pectin in your tomato as

soon as the flesh is cut. The enzymes are activated by air and

then denatured (made inactive) by heat, so you need to keep your

tomatoes intact until the last minute, then heat the whole mass of

tomatoes up as fast as possible. Thus the skillet --- more

surface area on the burner means your sauce comes to a boil

faster. Plus, there's more surface area through which excess

water can cook off.

Prepare your tomatoes. Romas don't have any

core to speak of, so after a quick rinse, you can just lop off the very

top where the stem was attached. Quickly chop each roma into

three pieces and toss them in the skillet. (Note: I'm of the

"skins and seeds are good for you and taste fine" school of

thought. If you disagree, you'll want to remove both at this

stage.) Once you've cut all of the tomatoes into large chunks,

take big handfuls and squeeze them until there's enough liquid in the

pan that the tomatoes won't stick to the bottom and burn.

Prepare your tomatoes. Romas don't have any

core to speak of, so after a quick rinse, you can just lop off the very

top where the stem was attached. Quickly chop each roma into

three pieces and toss them in the skillet. (Note: I'm of the

"skins and seeds are good for you and taste fine" school of

thought. If you disagree, you'll want to remove both at this

stage.) Once you've cut all of the tomatoes into large chunks,

take big handfuls and squeeze them until there's enough liquid in the

pan that the tomatoes won't stick to the bottom and burn.

Add other ingredients. Put your skillet of

tomatoes on the stove on medium-high heat (stirring the contents

occasionally so nothing sticks) and add anything else you like in your

spaghetti sauce. One of my large skillets holds about a gallon of

tomatoes, and to this I generally add 1 onion (sliced), 3 cloves of

garlic (pressed), 3 or 4 dried bay leaves, and some salt and

pepper. At the very end, I'll also add a lot of fresh basil

leaves and will vainly try to fish the used bay leaves out. If

I'm going to add hamburger meat, I usually cook it up separately and

add the meat at the end. Squash, peppers, or other vegetables can

go in about thirty minutes before the sauce is done.

Add other ingredients. Put your skillet of

tomatoes on the stove on medium-high heat (stirring the contents

occasionally so nothing sticks) and add anything else you like in your

spaghetti sauce. One of my large skillets holds about a gallon of

tomatoes, and to this I generally add 1 onion (sliced), 3 cloves of

garlic (pressed), 3 or 4 dried bay leaves, and some salt and

pepper. At the very end, I'll also add a lot of fresh basil

leaves and will vainly try to fish the used bay leaves out. If

I'm going to add hamburger meat, I usually cook it up separately and

add the meat at the end. Squash, peppers, or other vegetables can

go in about thirty minutes before the sauce is done.

Cook the sauce until it thickens. Delicious spaghetti

sauce has to be cooked long enough for the pectin to do its work.

I start the pan on medium-high until the contents are boiling hard,

then turn the heat down a bit at a time over the next hour or two until

the setting is on medium-low. During that time, the tomatoes will

cook down to about half their original volume. For quite a while,

you'll be stirring a pan of tomatoes and onions, but then, all of a

sudden, you can barely see individual components and the sauce tastes

and looks like sauce. Success!

Cook the sauce until it thickens. Delicious spaghetti

sauce has to be cooked long enough for the pectin to do its work.

I start the pan on medium-high until the contents are boiling hard,

then turn the heat down a bit at a time over the next hour or two until

the setting is on medium-low. During that time, the tomatoes will

cook down to about half their original volume. For quite a while,

you'll be stirring a pan of tomatoes and onions, but then, all of a

sudden, you can barely see individual components and the sauce tastes

and looks like sauce. Success!

Don't

worry if you scorch the bottom. I tend to forget to

stir nearly every batch at a critical stage and a bit of sauce sticks

to the bottom and burns. Whatever you do, don't

scrape that burnt bit back into the sauce and don't ignore it and keep

simmering. Instead, quickly pour off all of the good sauce into a

new skillet and set the scorched pan in the sink, filled with water, to

soak. As long as you don't stir the burnt sauce in or let the

good sauce sit on top of it long, you won't be able to taste the error

at all. (Maybe if you could, I'd be better about stirring and

wouldn't always let my spaghetti sauce burn?)

Lasagna is better for you than spaghetti. By now, I'm sure some

of you are wondering why I go to so much trouble to make spaghetti

sauce when we've deleted spaghetti from our diet and cut grains down to

a bare minimum. The same sauce can be used to make a high protein

and high vegetable lasagna that keeps my body healthy and my

spaghetti-loving tastebuds happy. To assemble a 9X13" pan of

lasagna, I use about a skillet and a half of spaghetti sauce, half this potsticker

dough recipe for the

noodles (which can be layered in uncooked), 1.5 pounds of hamburger

meat (cooked), quite a bit of cheddar, mozarella, and parmesan cheeses,

and any subset of cooked leafy greens, sliced summer squash, and sliced

mushrooms. Starting from tomatoes on the vine, it takes perhaps

three hours to make up a big pan of lasagna, but then we have quick

leftovers to heat up for lunch nearly all week!

Lasagna is better for you than spaghetti. By now, I'm sure some

of you are wondering why I go to so much trouble to make spaghetti

sauce when we've deleted spaghetti from our diet and cut grains down to

a bare minimum. The same sauce can be used to make a high protein

and high vegetable lasagna that keeps my body healthy and my

spaghetti-loving tastebuds happy. To assemble a 9X13" pan of

lasagna, I use about a skillet and a half of spaghetti sauce, half this potsticker

dough recipe for the

noodles (which can be layered in uncooked), 1.5 pounds of hamburger

meat (cooked), quite a bit of cheddar, mozarella, and parmesan cheeses,

and any subset of cooked leafy greens, sliced summer squash, and sliced

mushrooms. Starting from tomatoes on the vine, it takes perhaps

three hours to make up a big pan of lasagna, but then we have quick

leftovers to heat up for lunch nearly all week!

We had a rash of chicken

escapes this past weekend which has prompted us to start building poultry

pasture #6.

Mid to late summer is the

perfect time to start next year's no-till garden beds. Most of

the big weeds that grace neglected ground --- ragweed, wingstem, and

goldenrod for us --- are blooming or are about to bloom but haven't

gone to seed yet. At the pre- to mid-bloom stage of a plant's

life, the weed has pumped as much of its energy as possible into

creating viable blooms, so if you cut the plants now, they'll be

hard-pressed to regrow. (You take advantage of this fact when you

mow-kill

cover crops at this

same life stage.)

Mid to late summer is the

perfect time to start next year's no-till garden beds. Most of

the big weeds that grace neglected ground --- ragweed, wingstem, and

goldenrod for us --- are blooming or are about to bloom but haven't

gone to seed yet. At the pre- to mid-bloom stage of a plant's

life, the weed has pumped as much of its energy as possible into

creating viable blooms, so if you cut the plants now, they'll be

hard-pressed to regrow. (You take advantage of this fact when you

mow-kill

cover crops at this

same life stage.)

Meanwhile, midsummer is

the perfect time of year to smother lower-growing perennials (like

grasses and clover) in areas where you want garden beds to grow next

year. Cool season grasses have already gone to seed and are

currently trying to sock away as much solar energy as possible to store

in their roots and allow the plants to pop back up early next

spring. By covering up perennials in the middle of the summer,

you have the best chance of killing these hardy plants so that the soil

will be completely weed-free and ready for vegetables come spring.

So "weed" in the title

of this post does double duty --- I'm using weeds to create a kill

mulch to smother other weeds. The main component of my weed kill

mulch is those fifteen

foot tall ragweed plants from one of our chicken pastures --- I'm pretty sure the

ragweed shaded out the understory and made it harder for our Cuckoo

Marans to find tender forage. Mark's ninja

blade made quick

work of the huge ragweed stalks, then I gathered them up and tossed

them over the fence to lay alongside the existing beds in the forest

garden.

Even though the idea

makes a lot of sense, I should warn you up front that this is another

crazy experiment. That said, I already tried out a similar weed

kill mulch last week when I raked up all

of the stalks Mark whacked down in the forest garden itself and use them to increase my

mulched area. The weeds quickly died back to a black mass of free

mulch, so I'm pretty confident the weed kill mulches will work,

although they might need another layer of weeds added on top if

perennials start popping up through.

The other factor to

consider is the C:N

ratio of your

weeds. I had Mark cut a lot of saplings in one of the deer

danger zones, then I

piled them in another part of the forest garden in a sort of horizontal

brush pile (three or four feet deep.) Branches and young trees

are too woody to rot down into an acceptable mulch for vegetables by

next spring, so I'll either top them off with manure and turn the area

into a hugelkultur bed or just throw weeds on top and let the brush

pile slowly rot down. Ragweed cut at the blooming stage, though,

is only moderately woody, so I have high hopes we'll be able to plant

directly under those kill mulches next spring.

Anna noticed more deer damage

to the sweet potatoes on her morning tour.

"Not the ones by the Deer

Zapper though....right?"

Turns out a leaf grew just

tall enought to touch the electrical wire, which burned the leaf and

disarmed the Zapper.

Maybe I should have installed

the wire a bit higher. Perhaps some adjustable legs so that we can

raise it up as the plants grow.

Huckleberry informed me that

it was high time I sorted through our onions, cut off the stems, and

put them away.

Huckleberry informed me that

it was high time I sorted through our onions, cut off the stems, and

put them away.

I'm sad to say that our

beautiful onion

braids all started breaking apart after hanging for just a few

days. I guess those folks on the internet who recommend you braid

a piece of rope in amid the leaves were right.

After several braids

fell to the ground, I ended up drying the onions on the anti-cat screen

atop the chick brooder. Our last set of chicks is due to hatch

this week, so I guess Huckleberry was right.

A considerable number of

onions were already slightly softened, presumably due to bruising from

their unexpected fall. Rather than sorting by size the way I

usually do, I instead used a squeeze test to pull out all of the onions

that need to be eaten in the next month. The

hard-as-a-storage-pear onions go in other bags to be used later.

We've been hearing a rubbing

sound from the rear area of the golf cart and thought it was time for a

brake inspection.

I had some difficulty getting

the drum off. The main trouble was leaving the parking brake

engaged. In my defense it was getting very hot, which seems to increase

dumb mistakes for me.

Once the pressure was reduced

the drum started to back off with some serious effort from a

big pry bar. It took

about 10 minutes of prying. Pry a little on one side, do the other, and

then the top and bottom trying to keep it as even as possible.

Mark would appreciate it if

you all could talk me out of it, but I'm currently thinking seriously

about goats. Our land is perfect for goats (lots of brush) as

long as I keep them out of the snail-friendly floodplain, and I think

that adding an herbivore to our menagerie would make the farm more

productive and fill an empty ecological niche.

Mark would appreciate it if

you all could talk me out of it, but I'm currently thinking seriously

about goats. Our land is perfect for goats (lots of brush) as

long as I keep them out of the snail-friendly floodplain, and I think

that adding an herbivore to our menagerie would make the farm more

productive and fill an empty ecological niche.

In the past, I've

steered clear because I'm unwilling to follow the lead of my neighbors

and chain a goat, and I didn't trust my fencing ability to keep these

wily animals out of our beloved garden. However, Sharon

Astyk (fondly known

as "blogger Sharon" in our dinner table conversations) assured me that

four foot fencing is enough to keep in her favorite variety ---

Nigerian dwarf goats.

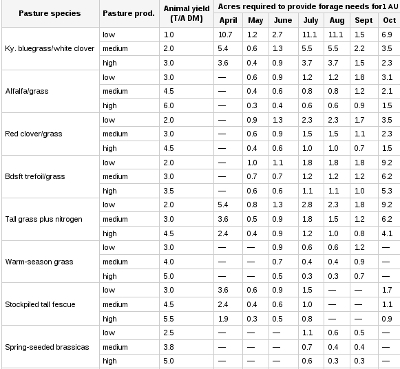

We've been doing a lot of

fencing this year for our chickens and already have nearly a tenth of

an acre of pasture (with two more pastures

partially built.) Since Nigerian dwarf goats are so small, I've

read that you can feed them on 0.13 to 0.16 acres apiece, which makes

goat pastures sound well within reach. In addition, our chickens

won't eat the woodier plants like ragweed and young trees, so it's

likely that we could add goats to the chicken pastures without taking

away much food from the chickens at all.

We've been doing a lot of

fencing this year for our chickens and already have nearly a tenth of

an acre of pasture (with two more pastures

partially built.) Since Nigerian dwarf goats are so small, I've

read that you can feed them on 0.13 to 0.16 acres apiece, which makes

goat pastures sound well within reach. In addition, our chickens

won't eat the woodier plants like ragweed and young trees, so it's

likely that we could add goats to the chicken pastures without taking

away much food from the chickens at all.

Most people plan to milk

year-round, but Sharon reports that if you breed your goats to kid in

the spring when forage is at its most abundant, you can let the goat

dry off for the winter and hardly have to feed any grain. That

means better quality milk and a more sustainable livestock

system. In addition, seasonal milking lets you go out of town

during the off season without finding a milking helper.

Sharon solves the twice a day

milking problem as well. She recommends milking your goats in the

morning, then putting the kid back with its mother to spend the day

grazing together. That way, you only have to milk once a day

rather than twice and your evenings are free. Meanwhile, Sharon

uses a modified breast pump to do the majority of the milking, which

saves her hands --- my carpal tunnel made the idea of daily milking

unlikely until I learned about this gadget --- and also lets an

untrained friend milk the goat if necessary.

Sharon solves the twice a day

milking problem as well. She recommends milking your goats in the

morning, then putting the kid back with its mother to spend the day

grazing together. That way, you only have to milk once a day

rather than twice and your evenings are free. Meanwhile, Sharon

uses a modified breast pump to do the majority of the milking, which

saves her hands --- my carpal tunnel made the idea of daily milking

unlikely until I learned about this gadget --- and also lets an

untrained friend milk the goat if necessary.

Using the seasonal,

once-a-day milking method, we'd end up with around 25 gallons of

milk from one Nigerian dwarf goat per year, which would fulfill our

dairy needs quite nicely. Sharon reports that milk from Nigerian

dwarf goats tastes just like cow milk and I've read that goat milk in

general is supposed to be easier to digest than cow milk. I used

to love milk until I stopped being able to drink the grocery store

stuff a few years ago, so I'm hopeful that goat milk could put me back

in business. Of course, you also get to eat goat meat in the fall

when those kids grow up.

I'm tempted to buy one

(or two if I think one would be lonely) male dwarf goats this winter to

see how he does on our pasture and with our fencing before committing

to the whole milking endeavor. Males are much cheaper than good

milking does, so it wouldn't be so  bad if the experiment didn't

work out and we had to eat the goat or sell him.

bad if the experiment didn't

work out and we had to eat the goat or sell him.

All of that said, there

are some very valid reasons not to get goats. First of all,

domesticated animals are a huge commitment, and I'm not sure if we're

ready to expand the menagerie. And I'm not clear on how the herd

dynamics would work out --- could we keep one doe and her kid, bringing

her to a local breeder when she's in heat, or would she be lonely in

the winter? Any more than one goat would mean doubling our

pasture area, which is feasible but more of a two year project.

Speaking of which, are our quick and dirty fences really good enough to

keep in even the tiniest goats? And do goats in the off season

fit our mandatory "can fend for itself for four days while we're out of

town" requirement? Finally, Mark's worried that Nigerian dwarf

goats are too cute to kill, which would make them less enticing.

Please chime in with

other reasons not to try out goats. I need someone to quench the

flame of my desire!

Today was just dry enough to

allow a few trips in the truck back to the trailer.

We managed to unload a truck

full of lumber, made a much needed trash haul to the dump, and filled

up on manure.

I must say today was a good

day.

Whenever

I read permaculture-related books, I see great ideas that I can't

resist putting into practice. Some of them have amazing results,

but half or more fail miserably. Are the authors of the books

merely book learners who haven't tried out their ideas on the

ground? Sometimes. But more often, they simply fail to

mention their specific growing conditions and I forget to think about

how the ideas might mesh with my own site.

Whenever

I read permaculture-related books, I see great ideas that I can't

resist putting into practice. Some of them have amazing results,

but half or more fail miserably. Are the authors of the books

merely book learners who haven't tried out their ideas on the

ground? Sometimes. But more often, they simply fail to

mention their specific growing conditions and I forget to think about

how the ideas might mesh with my own site.

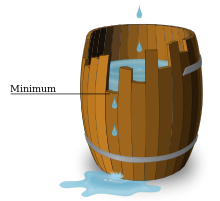

Limiting

factor is a useful ecological concept to understand when deciding

whether new ideas are worth trying in your garden. Unless you're

growing your

plants hydroponically under lights in climate-controlled conditions,

there's going to be some factor that keeps the crops from achieving

their full potential. The scientist who came up with the concept

of limiting factors used the illustration of a broken barrel to help

others visualize what he was talking about. No matter how much

water you pour into the barrel, it will only fill to the level of the

lowest stave --- the barrel's limiting factor.

Limiting

factor is a useful ecological concept to understand when deciding

whether new ideas are worth trying in your garden. Unless you're

growing your

plants hydroponically under lights in climate-controlled conditions,

there's going to be some factor that keeps the crops from achieving

their full potential. The scientist who came up with the concept

of limiting factors used the illustration of a broken barrel to help

others visualize what he was talking about. No matter how much

water you pour into the barrel, it will only fill to the level of the

lowest stave --- the barrel's limiting factor.

The most common

limiting factor for companion planted crops (and the

one that's

assumed by default in forest gardening literature) is light --- if you

plant peppers under your apple trees, the peppers will be puny because

the tree leaves steal their sunlight. In the conventional

vegetable garden, nitrogen is often assumed to be

the limiting factor since

that macronutrient can quickly wash out of the soil and since plants

won't grow much at all if faced with a nitrogen

deficiency.

Other common limiting