archives for 07/2011

Although some varieties of gooseberries change color, others look

just the same when they're ripe as they did a month previously when

they were hard and sour. So, how do you know when to pick them?

Although some varieties of gooseberries change color, others look

just the same when they're ripe as they did a month previously when

they were hard and sour. So, how do you know when to pick them?

Your best bet is to

nibble on a berry every week or two between June and August, waiting

until the fruits start to taste sweet. A ripe berry will also

give a little when you squeeze it, but will not burst open (unless

you've waited too long and it's overripe.)

Once you figure out when

your variety ripens up, you can mark that date on your calendar and

know henceforth to look for your Invicta gooseberries on June 30 (in

our specific example.) Enjoy!

So now that I've told you the

hows and whys, I can finally share my own seed

ball

experiments. My goal was to plant the summer and fall crops in

the do-nothing

grain area at the

same time that I refreshed the clover population. For our winter

grain, I opted to switch over to rye, and my new summer grains include

field corn, oilseed

sunflowers, amaranth, and pearl millet.

So now that I've told you the

hows and whys, I can finally share my own seed

ball

experiments. My goal was to plant the summer and fall crops in

the do-nothing

grain area at the

same time that I refreshed the clover population. For our winter

grain, I opted to switch over to rye, and my new summer grains include

field corn, oilseed

sunflowers, amaranth, and pearl millet.

I wanted to keep each

type of summer grain separate, so I made four different mixtures ---

sunflower/rye/clover, amaranth/rye/clover, millet/rye/clover, and

field-corn/cowpeas/rye/clover. You'll notice that the corn

mixture is a little different since I added cowpeas to give this heavy

feeder an extra dose of nitrogen.

I also wanted to know whether

seed balls are really any better than the lower work method of just

mixing up the ingredients and scattering the dirt/seed mixture amid the

wheat stubble. So, all told, I had eight experimental treatments

--- corn/rye/clover balls, corn/rye/clover mixed into loose earth, etc.

I also wanted to know whether

seed balls are really any better than the lower work method of just

mixing up the ingredients and scattering the dirt/seed mixture amid the

wheat stubble. So, all told, I had eight experimental treatments

--- corn/rye/clover balls, corn/rye/clover mixed into loose earth, etc.

Real conclusions will

have to wait a few weeks, but I already have a few observations.

First, I haven't seen any wild birds chowing down on my seeds, which is

a bit surprising since lots of seeds are visible on the outside of the

seed balls and in the loose earth mixtures. Even more exciting,

the seeds are already sprouting! Field corn may be a bit of a

problem in a seed ball since the kernels are so large that they tend to

fall out of the earth mixture and

sit on the wheat stubble, but clover and pearl millet leaves are poking

up through the dirt. I have high hopes that the other seeds will

soon follow suit.

| This post is part of our Seed Ball lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We've still got more Egyptian

Onion bulbs.

The new way to win is easy.

Just help spread the word about one of our

new E-books.

Make a blog post, mention it

on a forum, create a review(Thanks Jayne), or think of a fresh and new

way to promote it. Just drop Anna an email with the details and you

will soon know the awesome power of these perennials.

If

you're looking for a homesteading beach

read, look no further than Possum

Living by

"Dolly Freed." The chatty, informative, and

learned book was written by an 18 year old who dropped out of seventh

grade to live the "possum" life with her alcoholic father (before

getting her GED, putting herself through college, and going to work for

NASA.) The duo practiced urban

homesteading long

before it was cool, raising chickens and meat

rabbits in their basement, trapping pigeons, and rescuing wilted

produce from behind grocery stores. They lived on $1,400 per year

in 1978, using the library and the garden to keep body and soul

together.

If

you're looking for a homesteading beach

read, look no further than Possum

Living by

"Dolly Freed." The chatty, informative, and

learned book was written by an 18 year old who dropped out of seventh

grade to live the "possum" life with her alcoholic father (before

getting her GED, putting herself through college, and going to work for

NASA.) The duo practiced urban

homesteading long

before it was cool, raising chickens and meat

rabbits in their basement, trapping pigeons, and rescuing wilted

produce from behind grocery stores. They lived on $1,400 per year

in 1978, using the library and the garden to keep body and soul

together.

There are plenty of gems of

information in Possum

Living that you

won't find

in more smooth, modern homesteading books. For example, the

author recommends that you eat seed potatoes and wheat from the feed

store to save cash on staple foods, walks you through moonshining on

the cheap, and reminds you that gleaning the food left behind in fields

after the monster tractors do their harvesting is a tradition that

dates back to biblical times. (Well, without the monster

tractors.)

The facts are fun, but

the reason I call Possum

Living a beach

read is

because it's really the heart-warming tale of a girl and her father

living the good life. Yes, there are plenty of passages that made

me roll my eyes and

imagine the book I might have written at 18 before adulthood had given

me a critical lens through which to view the words of my smart,

opinionated father. But how often do you read a book by a

teenager who is so thoroughly enamored of her daddy? To best

appreciate the bittersweet elements, flip to the back of the new

edition to see what the author has to say 30 years later. And

don't miss the embedded video, part one of three.

If I had to sum up our summer

season with one sound it would be the mechanical clatter and spray that

pulsate from these sprinklers on a hot day like today.

The joke goes that July is

the only month when you have to lock your car in

[insert the name of your rural county here] or you'll return to find

it full of zucchini. Previously, I've rolled my eyes and held out

my hand when told that tale of garden bounty, but for the first time in

2012, succession planting and variety selection have allowed us to

defeat the squash

vine borer and we're

drowning under an ever expanding pile of summer squash.

The joke goes that July is

the only month when you have to lock your car in

[insert the name of your rural county here] or you'll return to find

it full of zucchini. Previously, I've rolled my eyes and held out

my hand when told that tale of garden bounty, but for the first time in

2012, succession planting and variety selection have allowed us to

defeat the squash

vine borer and we're

drowning under an ever expanding pile of summer squash.

We've done our best to

eat the bounty (and have at least one great new recipe to share), have dried

masses of the squash for the winter, but the inevitable finally

happened --- monster squash! In my gourmet

opinion, a monster squash is any summer squash where the seeds have

become more than a thin line within the flesh. There are so many

tender, young squash competing for my attention that I figure a monster

squash isn't worth my culinary time.

Of course, the

permaculture side of me isn't willing to let even a monster squash go

to waste, and once I started thinking up purposes for our one monster

squash, I wished I had a few dozen more. Here are my top ideas:

- Save the seeds.

Summer squash are on the easy

seed-saving list. Just let your monster squash keep growing

for an extra week or two until the seeds inside are well developed, cut

the squash open and carefully pull the seeds out, choose the fattest

seeds that didn't get injured, then let them dry before putting the

seeds away for next year. The only trouble you'll get into is if

you're growing a hybrid or if more than one variety of Cucurbita pepo is blooming in

your garden at the same time.

Feed the chickens, pig, goats,

etc. Monster vegetables are good to pass off on your

barnyard animals, especially if the flock doesn't have access to much

vegetation. If you're feeding monster cucurbits to chickens, be

sure to cut the vegetable in half or into smaller sections and drop it

cut-side-up in the pasture.

Feed the chickens, pig, goats,

etc. Monster vegetables are good to pass off on your

barnyard animals, especially if the flock doesn't have access to much

vegetation. If you're feeding monster cucurbits to chickens, be

sure to cut the vegetable in half or into smaller sections and drop it

cut-side-up in the pasture.

- Feed the worms. If you only have a small, under-the-sink worm bin, you'll have to be careful not to overload it. But outside bins can handle lots and lots of monster squash. For fastest results, cut the squash into chunks or throw it in the blender before feeding.

- Compost it. The

last resort with any kind of organic matter, of course, is to toss it

in the compost pile. You might end up with some volunteer squash

next year if your pile doesn't get hot enough, but won't have any other

problems.

I saved the seeds from

my monster crookneck squash and then gave the remains to the old girls,

who asked for more. What do you do with monster squash?

A week and a half after

"planting", many of my seed

balls have

germinated. In fact, the seedlings have already punched their

roots down out of the seed ball and into the ground below --- essential

if they're going to make it.

I'm excited to see the

seedlings growing so fast, but there are some clear problems with the

method. I tossed the seed balls out during a rainy spell and many

of the seeds germinated only to wither up when hot, dry weather deleted

the moisture from their exposed earth. I can see how smaller seed

balls would have nestled down into the ground and been less prone to

dessication.

Some of the seeds did much

better than others. The clover

sprouted very well, but the seedlings were also some of the first to

wither when seed

balls dried out, while the grass-like rye and millet seemed to be the

best sprouters and survivors. Cowpeas also did surprisingly well

(since the seeds are large and prone to fall out of the ball), but I

only found two field corn seedlings and one sunflower seedling.

The jury's still out on the slower-germinating amaranth.

Some of the seeds did much

better than others. The clover

sprouted very well, but the seedlings were also some of the first to

wither when seed

balls dried out, while the grass-like rye and millet seemed to be the

best sprouters and survivors. Cowpeas also did surprisingly well

(since the seeds are large and prone to fall out of the ball), but I

only found two field corn seedlings and one sunflower seedling.

The jury's still out on the slower-germinating amaranth.

Finally, I was

interested to compare seed balls to the same mixture that hadn't been

formed into balls and had merely been scattered on the ground

as-is. It's tough to tell with the seedlings so young, but both

methods seem to be about equally effective, making me lean toward the

lower work, non-ball method for future experiments. I'll keep you

posted as my experimental seedlings grow.

The 4 ton

hand winch did a good job

at squeezing the truck bed frame a few centimeters in an attempt to

make the tailgate latch stay closed.

It helped a little, but not

enough to feel like it won't pop open during a hard bump.

We've got a GMC dealer close

by that might know what's wrong, but I've been afraid to ask them due

to the fear of sticker shock.

Egg production went way down

about a month ago, but I wrote it off as our ancient hens hitting

"menopause." I should have searched harder for the answer --- 24

eggs hiding in the deep grass of the pasture!

Egg production went way down

about a month ago, but I wrote it off as our ancient hens hitting

"menopause." I should have searched harder for the answer --- 24

eggs hiding in the deep grass of the pasture!

Usually, our chickens

are very good about laying in the nest box since we keep it comfy with

clean straw or leaves and seed the

pot with golf balls. But a lot of factors have made the spot

less conducive to laying lately. First, the broody

hen took over the box, then the tweens got bigger and bigger until

the huge coop Mark built me started to feel cramped. I guess that

with two strikes against the coop, the straw-like, dense grass matted

down in parts of the pasture looked more like a nest.

Egg production rebounded

about a week ago, so I'm hoping the naughty hens have decided to

behave. These old eggs would probably be fine, but since we're

not desperate, we'll use them to give Lucy a treat for the next few

weeks.

I've researched several

automatic chicken coop door openers and one thing they have in common

is the part where you need to build your own door.

Maybe you don't have the

time, tools, or skill to build a door, but still need to protect your

chickens?

Jeremy at automatic chicken coop

door.com has a product that is ready to go right out of the box and

was kind enough to send us one to review here.

This thing is made from high

quality wood and the slider piece is coated with linseed oil for

protection. It uses a proven drapery motor to lift and lower the door,

which is nicely enclosed towards the top. The cost is just over 200

hundred dollars and I would call it a good deal when you consider how

much time you save compared to hunting down the supplies and building it

yourself. It's also nice not to go through a trial and error process

working out kinks and risking more predator attacks.

Stay tuned for my field notes

on its operation and how easy it was to install.

'Tis the season to eat summer

squash at least once a day. Unfortunately, since the tomatoes

haven't come in yet, we've gotten bored with sauteed or steamed squash

and can't branch out into my usual favorites --- squash in lasagna and

in harvest

catch-all soup.

At the same time, our basil bed needs to be nibbled on, but since we're

no longer using pesto pasta as a standby meal, I have little incentive

to pick the delicious herb. Luckily, I discovered a recipe in Possum Living that solved both my problems.

'Tis the season to eat summer

squash at least once a day. Unfortunately, since the tomatoes

haven't come in yet, we've gotten bored with sauteed or steamed squash

and can't branch out into my usual favorites --- squash in lasagna and

in harvest

catch-all soup.

At the same time, our basil bed needs to be nibbled on, but since we're

no longer using pesto pasta as a standby meal, I have little incentive

to pick the delicious herb. Luckily, I discovered a recipe in Possum Living that solved both my problems.

I tweaked Dolly Freed's

recipe a bit and actually ended up with two different recipes, quite

different but both delicious. Since we can't decide which one we

like best, I'll share both. First, cut up three or four medium

crookneck squash (or summer squash variety of your choice) into

moderately thin slices. Saute the squash in two tablespoons of

butter until all of the squash is soft and some is a bit brown, adding

salt and pepper as you cook.

I tweaked Dolly Freed's

recipe a bit and actually ended up with two different recipes, quite

different but both delicious. Since we can't decide which one we

like best, I'll share both. First, cut up three or four medium

crookneck squash (or summer squash variety of your choice) into

moderately thin slices. Saute the squash in two tablespoons of

butter until all of the squash is soft and some is a bit brown, adding

salt and pepper as you cook.

For

recipe 1, add three cloves of minced garlic, stir briefly, then turn

off the heat. Top the squash off with parmesan cheese and fresh

basil. This recipe tastes a bit like pesto pasta --- the garlic

is very evident.

For

recipe 1, add three cloves of minced garlic, stir briefly, then turn

off the heat. Top the squash off with parmesan cheese and fresh

basil. This recipe tastes a bit like pesto pasta --- the garlic

is very evident.

For recipe 2, turn off

the heat as soon as the squash is done and mix in a bit of powdered

milk and plenty of fresh basil. Stirring should make the powdered

milk rehydrate slightly in the butter coating, but the milk will still

be chunky. This recipe tastes nothing like mac and cheese in a

box but seems to give me that same comfort food feeling, probably

because of the sweetness of the powdered milk combined with the butter.

Pasta with various

sauces used to be one of our quick and easy meals, but since we've been

lowering the grain content of our diets, I've discovered that what I'm

yearning for when I crave pasta is really the intense flavors of the

toppings. Summer squash seems to be a good venue for pasta

toppings, has a higher percentage of protein than pasta does, and a cup

of squash provides 18% of your daily allotment of vitamin C. Of

course, like most vegetables, squash also has a lot fewer calories than

pasta, so you wouldn't want to consider either of these recipes to be a

main course or you'll end up hungry.

Installation of the automatic

chicken coop door can be done with just a few wood screws. Jeremy

includes some metal brackets that helped fine tune the door to our

latest chicken

coop made from pallets.

The new automatic chicken coop

door came with a timer

which makes it easy to set when the flock can go out. I first thought I

might try to get one of those dusk to dawn sensor switches, but the coop

gets shaded by a hillside that delays the full morning sun by a few

hours depending on the time of year.

I would suspect the moment

when the chickens can first start to see in the dawn light would be a

good time to hunt insects that are trying to get home after a full

night of crawling around. This might be a good reason to open the door

a little on the early side. That way they can decide when there's

enough light out to jump off the roost and start foraging. I guess that

means there's a chance that a racoon working the morning shift might

happen upon the door open, but I think it might be worth the risk if it

means the flock gets more protein rich bugs in their diet.

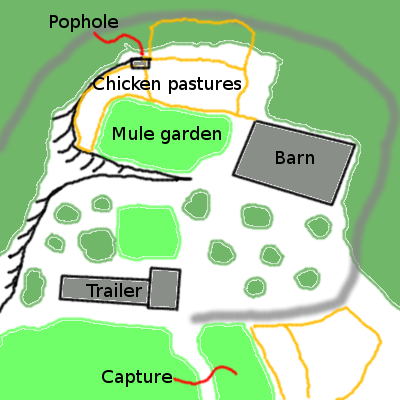

Unless

you have opposable thumbs, it's a long, long way from Mark's new

automatic chicken coop door (labeled pophole) to our trailer. We

can cut through the pastures, but a chicken has a choice of two

exhausting options. They can turn left outside the pophole and

skirt the pasture fence for quite a ways, then bushwhack through briars

and climb up the steep incline to the plateau that houses our

homestead. Or they can turn right outside the pophole and follow

the gentler slope of the driveway, traveling perhaps a tenth of a mile

around the barn and into our farm proper.

Unless

you have opposable thumbs, it's a long, long way from Mark's new

automatic chicken coop door (labeled pophole) to our trailer. We

can cut through the pastures, but a chicken has a choice of two

exhausting options. They can turn left outside the pophole and

skirt the pasture fence for quite a ways, then bushwhack through briars

and climb up the steep incline to the plateau that houses our

homestead. Or they can turn right outside the pophole and follow

the gentler slope of the driveway, traveling perhaps a tenth of a mile

around the barn and into our farm proper.

When our

australorps started slipping under the gate and exploring the floodplain a couple of months ago, I

was a bit concerned that they would make one of these treks and find

our delicious garden fruits and enticing mulch. But I soon set my

fears to rest --- even when I walked Lucy through our free ranging

flock, the chickens stopped following me at the end of the pasture

fence and headed back to the woods closer to the coop to look for

easier pickings.

When our

australorps started slipping under the gate and exploring the floodplain a couple of months ago, I

was a bit concerned that they would make one of these treks and find

our delicious garden fruits and enticing mulch. But I soon set my

fears to rest --- even when I walked Lucy through our free ranging

flock, the chickens stopped following me at the end of the pasture

fence and headed back to the woods closer to the coop to look for

easier pickings.

I'd been considering opening

a pophole directly into the floodplain so that the old girls could join

these youngsters on their free range jaunts, but I was a bit concerned

that an unfenced door into a chicken coop at the furthest limits of

Lucy's usual patrols would be too much for predators to resist. Jeremy's

automatic chicken door

seemed like the answer --- I could let the chickens out to eat all that

good food in the floodplain without worrying about predators. So

as soon as Mark had the door in place, I opened it up and called our

chickens to explore.

I'd been considering opening

a pophole directly into the floodplain so that the old girls could join

these youngsters on their free range jaunts, but I was a bit concerned

that an unfenced door into a chicken coop at the furthest limits of

Lucy's usual patrols would be too much for predators to resist. Jeremy's

automatic chicken door

seemed like the answer --- I could let the chickens out to eat all that

good food in the floodplain without worrying about predators. So

as soon as Mark had the door in place, I opened it up and called our

chickens to explore.

Less than an hour later,

our ornery old hens were eating raspberries in our front yard.

The good news is that the australorps didn't follow, so there's still a

chance that my plan to let the chickens free range in the floodplain

will work once we delete the old girls from the flock. But, for

now, the pophole is shut and everyone is relegated to the

pasture. I wonder if those few raspberries were worth such an

arduous journey?

Here's what the new automatic

chicken coop door looks like from the inside.

While I was taking these

pictures all three of the older hens walked over to investigate.

It may have been my

imagination, but it seemed like they wanted me to open the door, which

got me to wondering if they had enough long term memory to recall yesterday's

journey to our juicy raspberries?

The garden is full of

almosts this week....

Almost sweet corn.

Almost onions.

Almost crowing.

(Almost dinner.)

Almost tomatoes.

Almost okra.

Almost mountains.

Almost too many.

Almost impossible to

spend a day in the garden without realizing how lucky we are.

Last

year I struggled a bit

when it was time to catch a chicken for processing. The coop was 10

feet long and about 5 feet wide, which gave them plenty of room to

scurry away from me.

This year we decided to

convert one

of our old chicken tractors into a holding coop in an attempt to

make it easier on me and the chickens.

The white barrier wall is

made from a couple of chicken feed sacks turned inside out. It's a very

sturdy material that's easy to work with at a price that's hard to

beat.

Mark had gone into town to mail chicken waterers on Friday morning, and I was

happily mulching the garden when what did I see coming around the

corner but....eleven chickens! Those old

hens must have talked up sun-warmed raspberries until our Golden Comet

cockerel decided to lead as many of his siblings as he could around the

bend and up into the garden.

Mark had gone into town to mail chicken waterers on Friday morning, and I was

happily mulching the garden when what did I see coming around the

corner but....eleven chickens! Those old

hens must have talked up sun-warmed raspberries until our Golden Comet

cockerel decided to lead as many of his siblings as he could around the

bend and up into the garden.

Luckily for me, Black

Australorps are very different foragers than Golden Comets. While

the Golden Comets head straight for color and then scratch up the

mulch, the Australorps  were more interested in

picking bugs off the undersides of leaves in the tall weeds of the

forest garden. That's the good news.

were more interested in

picking bugs off the undersides of leaves in the tall weeds of the

forest garden. That's the good news.

The bad news is that

Black Australorps aren't as easy to capture as Golden Comets

either. Our Golden Comets are some of the easiest chickens you've

ever wrangled

--- if they don't crouch down at your feet and let you pick them up,

they'll

follow

the sound of feed rattling in a cup and come right back to the

coop. On the other hand, Black Australorps are such good foragers

that grain in a cup doesn't sound

nearly as good as that grasshopper you startled, and I couldn't even

wrap my mind around  trying to catch eleven chickens

all by my lonesome.

trying to catch eleven chickens

all by my lonesome.

What I could do, though,

was herd those pesky rascals back to their pasture and lock them

in. There's a trick to herding a flock of chickens --- you want

them alert enough to flock together rather than spreading out to

forage, but not so scared that they scatter in every direction.

If you keep your eye on the roosters and head those leaders off when

they try to walk the wrong way, then everyone else will follow. A

big hat in your extended hand turns you into two people --- one pushing

the main flock forward and another reminding that cockerel who's about

to bolt that he doesn't really want to veer off to the

right. Finally, keep your dog behind or beside the flock

--- no way those chickens are going to run straight into the

teeth of a canine.

Once Lucy and I thought the

problem through, we made short work of herding the chickens back around

the barn and into the floodplain. Then I blocked up that hole

under the gate that I'd intentionally left open to let our flock free

range. Sorry guys --- I know your pastures are overgrazed, but

you're grounded. There'll be a lot more elbow room next week, I

promise.

Once Lucy and I thought the

problem through, we made short work of herding the chickens back around

the barn and into the floodplain. Then I blocked up that hole

under the gate that I'd intentionally left open to let our flock free

range. Sorry guys --- I know your pastures are overgrazed, but

you're grounded. There'll be a lot more elbow room next week, I

promise.

You know you're hungry for

fresh, home grown tomatos when you check the ripening process multiple

times a day.

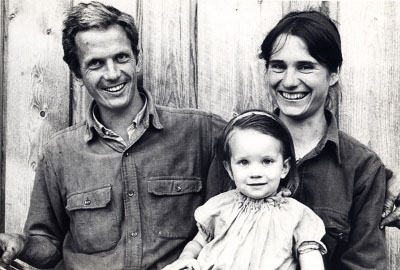

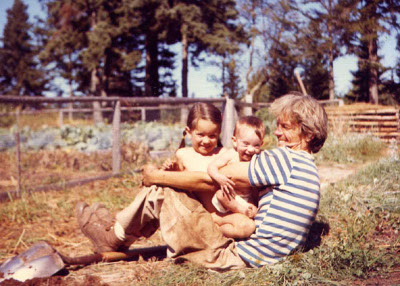

If Possum Living is the fun, beach read, Melissa Coleman's This Life is In Your Hands is a hard-hitting expose and

cautionary tale. The author writes about the joys and woes of

being the child of passionate organic farmers and homesteaders (Eliot

Coleman and his

wife) living next door to the Nearings.

If Possum Living is the fun, beach read, Melissa Coleman's This Life is In Your Hands is a hard-hitting expose and

cautionary tale. The author writes about the joys and woes of

being the child of passionate organic farmers and homesteaders (Eliot

Coleman and his

wife) living next door to the Nearings.

Most people will

probably pick up the book the same way they would slow to gawk at a

wreck along the highway, but the death of Melissa's sister (perhaps

from parental neglect)  was not the only tragedy

found between its pages. Instead, a deeper and more universal

affliction seems to have befallen most of the idealists who went back

to the land in the sixties and seventies, and those of us following in

their footsteps would do well to take heed.

was not the only tragedy

found between its pages. Instead, a deeper and more universal

affliction seems to have befallen most of the idealists who went back

to the land in the sixties and seventies, and those of us following in

their footsteps would do well to take heed.

Eliot Coleman had

hyperthyroidism combined with a passion for uncovering the secrets of

organic gardening --- the first gave him the energy to work long hours

and the second made the farm seem more important  than his family. In

contrast, his wife was prone to depression and would check out of daily

life by fasting or standing on her head --- the only ways she knew to

combat a mental fatigue that her physically present but emotionally

absent husband did nothing to correct. The end result (yes, I'm

going to ruin it for you) was neglected children and, eventually,

divorce.

than his family. In

contrast, his wife was prone to depression and would check out of daily

life by fasting or standing on her head --- the only ways she knew to

combat a mental fatigue that her physically present but emotionally

absent husband did nothing to correct. The end result (yes, I'm

going to ruin it for you) was neglected children and, eventually,

divorce.

As Melissa Coleman wrote

near the end of her book:

The sad truth is that

homesteads are like a lover or child --- enticing, beguiling, but also

oh so needy of your time and thoughts. If you can't mitigate your

relationship to the land in some way, you're bound to end up breaking

the human ties you also depend on.

The sad truth is that

homesteads are like a lover or child --- enticing, beguiling, but also

oh so needy of your time and thoughts. If you can't mitigate your

relationship to the land in some way, you're bound to end up breaking

the human ties you also depend on.While reading This Life is In Your Hands, I could completely envision what my homesteading journey would have been like without Mark's painstaking efforts to help me mix some realism with my idealism. I would have been hauling five gallon buckets of water from the creek to irrigate the garden by hand like my mother did, eschewing the idea of paying a neighbor for firewood, and generally working my fingers to the bone. In the end, exhaustion resulting from my passion for homesteading and permaculture would probably have driven me off the farm like so many other back-to-the-landers, leading to an overall harsher environmental footprint than the one I currently make when I allow us to drift away from the homesteading ideal from time to time. All I can say is --- I'm eternally grateful that the romantic lottery netted me Mark instead of Eliot Coleman!

Our chicken waterer keeps chicken chores to a

minimum so we have more time to enjoy our flock.

I parked a little too close to a horse manure pile last week and got

the truck stuck.

A new group of weeds had

grown up around the base of the pile hiding some of the richer material

and I forgot to bring a shovel.

This picture is Anna pulling

me out with the tow strap.

I've lost count on how many

times we've used that tow strap since it entered our tool bag.

Which is better, conventional

asparagus or all-male hybrids?

Which is better, conventional

asparagus or all-male hybrids?

First of all, you have

to understand the difference. Most plants have both male and

female flowers, but each asparagus plant is either entirely male or

entirely female, just like a person or a chicken. The female

plants are easy to see in late summer since they produce berries that

turn bright orange as they ripen.

If you grow conventional

asparagus, about half of your plants will be females and half will be

male. The female plants have to spend a lot of energy making

fruits every year, so they tend to have fewer and smaller spears ---

extension service websites say that females produce as little as a

third of the food that male plants do. That's why nurseries have

developed all-male hybrids --- strains in which nearly all of the

plants will be male.

The problem with

all-male hybrids is the same as the problem with hybrid seeds of other

garden vegetables --- you're no longer self-sufficient. I decided

I wanted to expand my  asparagus planting this year,

so I just dug up nine tiny plants that had self-seeded below our

conventional asparagus plants and set the seedlings out in their new

home. If I wanted to get a friend started with asparagus, it

would also be as simple as mailing him or her an envelope full of seeds.

asparagus planting this year,

so I just dug up nine tiny plants that had self-seeded below our

conventional asparagus plants and set the seedlings out in their new

home. If I wanted to get a friend started with asparagus, it

would also be as simple as mailing him or her an envelope full of seeds.

Whether the lower yield

of conventional asparagus is worth the ability to easily propagate your

own plants will probably depend on your space constraints. If I

had less elbow room but wanted to stay self-sufficient, I might plant a

conventional variety, then rip out nearly all of the female plants once

I could identify them. I would keep one female to seed new

asparagus plants, still enjoying the high yields of the mostly male

planting. As it is, though, I'm too lazy to be that high tech,

and am just enjoying the complex mix of all-male and conventional

plants that my garden acquired over the years.

This is a great year for Mexican

Sour Gherkins!

A bite sized, cucumber like

snack that tastes great alone or in a salad.

I would choose these over

popcorn if they offered them at theatre concession stands.

We slaughtered our two biggest

cockerels on Monday to get a feel for

whether we should plan to kill all the birds from flock 1 this week or

wait a little longer. My goal is to get a two pound dressed

carcass,

and our birds are still a little shy of the mark at 1.86 pounds apiece,

so most of our flock will get a short reprieve.

We slaughtered our two biggest

cockerels on Monday to get a feel for

whether we should plan to kill all the birds from flock 1 this week or

wait a little longer. My goal is to get a two pound dressed

carcass,

and our birds are still a little shy of the mark at 1.86 pounds apiece,

so most of our flock will get a short reprieve.

Although the cockerels

were light weight, I was thrilled to see that their feed to meat

conversion ratio was 4.5 : 1 --- vastly lower than what we got last

year with dark cornish and also lower than published figures for any

broiler breeds other than cornish cross. Stay tuned to our chicken blog this week for more serious

number crunching.

In

addition to saving money on feed, these permaculture pastured chickens

will give us higher quality meat. I know it sounds unscientific,

but I'm starting to get a gut feeling for the gestalt of a healthy

chicken (probably based on cleanliness of the carcass and uniformity of

the internal organs.) As I pored over these birds' entrails, I

was so pleased with their quality that I cooked some chicken neck and

liver stew for supper. Sounds a bit crazy, but tasted pretty good.

In

addition to saving money on feed, these permaculture pastured chickens

will give us higher quality meat. I know it sounds unscientific,

but I'm starting to get a gut feeling for the gestalt of a healthy

chicken (probably based on cleanliness of the carcass and uniformity of

the internal organs.) As I pored over these birds' entrails, I

was so pleased with their quality that I cooked some chicken neck and

liver stew for supper. Sounds a bit crazy, but tasted pretty good.

Where did you get your Mexican Sour

Gherkin seeds from?

Where did you get your Mexican Sour

Gherkin seeds from?

Everett,

We got ours from Bakers Creek

Heirloom seeds the first year, but Anna discovered an easy

way to harvest Mexican Sour Gherkin seeds, and that's what we do now.

We

had a 22 hour power outage Monday and Tuesday, and we lost:

We

had a 22 hour power outage Monday and Tuesday, and we lost:

A few

sweet potato leaves

to marauding deer. (More proof that Mark's deer deterrents really work...as long as they're

running.)

Twenty

hard to find Light Sussex eggs when the battery

pack didn't last long enough to keep the incubator up to

temperature.

Sleep. I fretted over the

eggs far too much, waking up multiple times in the night, but  Mark was worse off since he

can't sleep without the white noise of a fan and didn't want to wake me

up by coming in to get a flashlight to read himself to sleep.

Mark was worse off since he

can't sleep without the white noise of a fan and didn't want to wake me

up by coming in to get a flashlight to read himself to sleep.

Every time the power

goes out, I think I've learned my lesson and I'll have backups on hand

next time. And every time, the ease of flicking that switch lulls

me into a false sense of security after a few weeks.

That said, we are slowly

improving by tweaking our life so that normal habits can go on if the

grid shuts down for a few days. Even though we need electricity

to pump water out of  our well and treat it with UV

light, I keep at least a few of jugs of drinking water under the sink

in case of emergencies. I always leave my solar flashlight

charging on the windowsill since I use it if we come home after dark or

if I want to go out at night to check on the chickens, so the

flashlight is also ready for power outages. And after our extended winter

power outage, we

deleted the exterior wood furnace and replaced it with fan-less wood

stoves, so we will now stay warm no matter what.

our well and treat it with UV

light, I keep at least a few of jugs of drinking water under the sink

in case of emergencies. I always leave my solar flashlight

charging on the windowsill since I use it if we come home after dark or

if I want to go out at night to check on the chickens, so the

flashlight is also ready for power outages. And after our extended winter

power outage, we

deleted the exterior wood furnace and replaced it with fan-less wood

stoves, so we will now stay warm no matter what.

On the other hand, we've

still got a ways to go, especially in the Mark comfort

department. Luckily, it was a mild enough day that hosing down

with creek water and sitting in the shade kept him cool, but I'm not

sure how he would have handled a power outage if the highs had been in

the mid nineties instead of the mid eighties. Let's see if I can

remember to ponder this problem now that the wide world of electricity

is once again at my finger tips.

The new

isolation coop worked well at housing chickens the night before

processing and making the catching part easy and trouble free.

Some folks use a killing cone

to hold their poultry upside down before the final cut, but we've found

that a 5

gallon bucket with a hole cut in the bottom works just as well.

Those of you who

overthink everything (like me) probaby plant nectaries for your bees. Yet,

despite what I read, our bees seem to prefer the flowers that aren't

listed in books.

Wild pollinators are supposed

to love members of the aster family, but our Echinacea is mostly

bare. On the other hand, the squash patch is humming so loudly I

was almost afraid to stick my hand in there to pluck dinner.

Wild pollinators are supposed

to love members of the aster family, but our Echinacea is mostly

bare. On the other hand, the squash patch is humming so loudly I

was almost afraid to stick my hand in there to pluck dinner.

No one mentions it, but

our asparagus is a hotbed of tiny pollinators in the spring and early

summer. And when I was down in South Carolina, I discovered the

holy grail of the local wild pollinator contingent --- oregano.

Which unconventional

nectary plants do you see abuzz with life right now?

The other rear wheel fell off

the walk behind mower today.

Luckily I still had the

washers that are needed to fix this problem.

I had a feeling this would

happen when I replaced the first

rear wheel earlier this year with a new and improved version that came with its own metal

bearing. I guess all those extra vibrations went directly to the weak

wheel?

It takes a lot to tempt me to

turn on the oven in the summer, but trying out a new breed of chicken

made the cut. Roasting a chicken is not only easy, it keeps

the flavor of the bird very evident, and I wanted to be able to compare

and contrast the taste of our black australorps with last year's dark

cornish.

It takes a lot to tempt me to

turn on the oven in the summer, but trying out a new breed of chicken

made the cut. Roasting a chicken is not only easy, it keeps

the flavor of the bird very evident, and I wanted to be able to compare

and contrast the taste of our black australorps with last year's dark

cornish.

Since I was heating up

the house anyway, I figured I should fill that blistering cavern all

the way up. Roast roots went under the chicken to bake in the

drippings, a modified early summer ratatouille slid onto the bottom rack,

and a butternut

pie fit into the

space left behind. All told, the only off farm products involved

in the main course were salt, pepper, butter, and olive oil (although

the pie had more storebought components.) And now I won't have to

do anything except briefly heat up the leftovers for the next two or

three meals. Maybe that hour and fifteen minutes of oven time was

actually energy efficient?

By

the way, the roast australorp got the Mark seal of approval. My

taster said he couldn't tell the difference between this year's and

last year's birds, which is high praise since cornish are supposed to

be one of the best tasting chickens around. I thought the

australorp might have been just a hint less tender than the similarly

aged dark cornish, but that's what you get when your broilers run

around and eat bugs. The broth I'm cooking up from the bones has

brilliant yelllow fat on top, a sign of omega

3s and good nutrition,

so we know the chicken is good for us.

By

the way, the roast australorp got the Mark seal of approval. My

taster said he couldn't tell the difference between this year's and

last year's birds, which is high praise since cornish are supposed to

be one of the best tasting chickens around. I thought the

australorp might have been just a hint less tender than the similarly

aged dark cornish, but that's what you get when your broilers run

around and eat bugs. The broth I'm cooking up from the bones has

brilliant yelllow fat on top, a sign of omega

3s and good nutrition,

so we know the chicken is good for us.

After two years of heavy use in all weather, one of our sprinklers

started sticking.

The sprinkler didn't have any obvious method of disassembly, so Anna

tried to use a zoom spout oiler to lubricate the trouble zone.

Unfortunately, oil quickly washes off when faced with high pressure

water. The sprinkler kept sticking.

Liquid Wrench White Lithium Grease came to the rescue. Unlike

more conventional greases, Liquid Wrench comes in a spray can for easy

access to hard to reach places.

I let the grease dry on the sprinkler for an hour, then turned her

on. No more sticking.

Although neither of the Asian

greens I tried this spring held together once the heat hit, Mark and I

both loved the taste of tokyo

bekana and want to

try it in the fall garden. I wasn't about to spend another $3 for

a tiny package that barely seeds one bed, though, so I decided to let

the spring crop go to seed and collect the bounty.

Although neither of the Asian

greens I tried this spring held together once the heat hit, Mark and I

both loved the taste of tokyo

bekana and want to

try it in the fall garden. I wasn't about to spend another $3 for

a tiny package that barely seeds one bed, though, so I decided to let

the spring crop go to seed and collect the bounty.

Asian greens definitely

fit into the easy

seed-saving category

since the pods dry on the plant and hang around for weeks until you

remember them. Snip off the brown seed heads when they are

brittle, then thresh them any way you feel like

it. Since Mom recently gave me this great pestle, it didn't take

me long to pound the seed pods into submission.

Shake

your container gently and the heavier seeds will settle to the bottom,

allowing you to lift most of the chaff off with your fingers.

Then blow into your box to finish the winnowing

process --- the light pieces of pod will float away while the heavy

seeds will stay put. I didn't winnow all that carefully since I'm

just going to be putting the seeds and debris back into the ground, but

you could also pass the seeds through a screen (like a flour sifter) if

you wanted them to be cleaner.

Shake

your container gently and the heavier seeds will settle to the bottom,

allowing you to lift most of the chaff off with your fingers.

Then blow into your box to finish the winnowing

process --- the light pieces of pod will float away while the heavy

seeds will stay put. I didn't winnow all that carefully since I'm

just going to be putting the seeds and debris back into the ground, but

you could also pass the seeds through a screen (like a flour sifter) if

you wanted them to be cleaner.

The one potential sticking

point when saving seeds from brassicas is that many will

cross-pollinate. However, Asian greens share their species (Brassica

rapa) only with

turnips and with rape (the plants that are used to produce canola

oil). As long as you don't have any other Asian green varieties,

turnips, or rape plants in bloom at the same time as your select

variety, you can save the seeds with impunity.

The one potential sticking

point when saving seeds from brassicas is that many will

cross-pollinate. However, Asian greens share their species (Brassica

rapa) only with

turnips and with rape (the plants that are used to produce canola

oil). As long as you don't have any other Asian green varieties,

turnips, or rape plants in bloom at the same time as your select

variety, you can save the seeds with impunity.

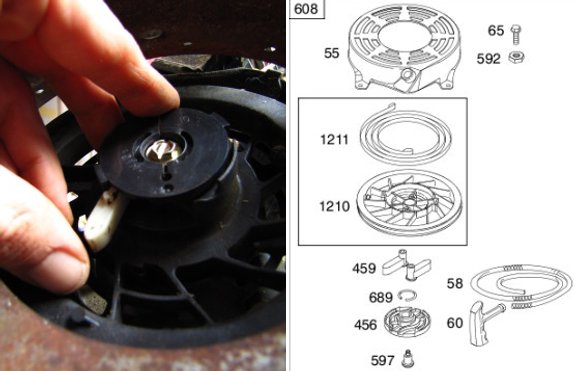

The pull rope on the mower

stopped doing its job about 10 minutes after I

fixed the rear wheel problem.

Most rewind starters have 2

white plastic fingers that extend out and grab when the rope is being

pulled and retract when the rope is released and its spring sucks it

back in.

These plastic fingers and the

groove designed to hold them are worn, causing the fingers not to

extend, and now when you pull on the rope nothing happens.

You can get the whole

mechanism for just under 40 dollars from Briggs and Stratton, which is

what I ordered. I was able to use sand paper to smooth out the rough

parts of the plastic to get it going for now, but I suspect it won't

last long due to the deformed groove.

I don't want to make you

think I don't like art --- in fact, I majored in studio art (and

biology) in college. And any good vegetable garden becomes a work

of beauty, full of enticing textures and colors. Still, I think

that many beginning homesteaders fall into the trap of thinking about

beauty first and utility second when planning their garden.

I don't want to make you

think I don't like art --- in fact, I majored in studio art (and

biology) in college. And any good vegetable garden becomes a work

of beauty, full of enticing textures and colors. Still, I think

that many beginning homesteaders fall into the trap of thinking about

beauty first and utility second when planning their garden.

My first year on the

farm, I chose the prettiest vegetables I could find in the seed

catalog. Bright Lights swiss chard with red, yellow, and orange

stalks, purple and ruffled cabbages, three colors of summer squash ---

I had it all. Over time, though, I've discovered that purple

carrots don't produce as high a yield as those ordinary-looking orange

carrots, striped zucchinis can't handle the vine borer the way yellow

crookneck can, and ruffled cabbages don't taste as good as plain Jane

cabbage heads. I've slowly started choosing varieties based first

on flavor, then on productivity (which includes bug and disease

resistance), third on seed-saving ability, and only finally on

appearance.

Our harvest basket still

looks beautiful, but now we have more, tastier food to eat and put

in the freezer. Mark's hypothesis is that folks who choose

seeds based on garden porn don't end up taking the time to harvest and

eat the produce, but I give art gardeners a bit more benefit of the

doubt. I think that, like me, they'll grow out of it.

One of the best things about

the Briggs and Stratton engine attached to our Craftsman mulching mower

is a superior design.

It only took a Philips screwdriver, and two metric sockets to access the starter

rewind unit. The fuel

tank pivots back out of the way without needing to be disconnected or

drained, which is a lot less messy than the mower I grew up with.

As

I weeded the potato beds, I stumbled across these little green fruits

nestled amid the foliage. No one seems to know why potato blooms

wither most years then develop into fruits every once in a while, but I

can attest that this is the first time in five years of growing

potatoes that I saw any fruits. I planted my potatoes very late

this year so that they'd store better, which might have had something

to do with it. Extension service websites also report that some

varieties (like the Yukon Golds I'm growing) fruit more often than

others.

As

I weeded the potato beds, I stumbled across these little green fruits

nestled amid the foliage. No one seems to know why potato blooms

wither most years then develop into fruits every once in a while, but I

can attest that this is the first time in five years of growing

potatoes that I saw any fruits. I planted my potatoes very late

this year so that they'd store better, which might have had something

to do with it. Extension service websites also report that some

varieties (like the Yukon Golds I'm growing) fruit more often than

others.

Potato fruits are

poisonous, but if you let them ripen, you can save the seeds the same

way you save

tomato seeds.

The goal isn't really to get more potatoes --- cloning the tubers is by

far the most efficient method of growing potatoes. Instead,

starting potatoes from seed is a way of playing the garden lottery,

producing lots of new varieties that might just possibly be better than

their parents.

Extensive searching of the

internet turns up only a few people who have actually committed the

time and space to grow potatoes from seed, and from what they report,

the project sounds like a lengthy undertaking. If I saved these

seeds in 2011, I'd plant them in early 2012 and end up with tiny tubers

no more than an inch in diameter. Save those tubers and use them

as seed potatoes in 2013, and I'd finally grow potatoes large enough to

taste and test. Although the garden geek in me is itching to give

it a try, I don't think we care enough about potatoes to allot that

much space and energy to the experiment.

Extensive searching of the

internet turns up only a few people who have actually committed the

time and space to grow potatoes from seed, and from what they report,

the project sounds like a lengthy undertaking. If I saved these

seeds in 2011, I'd plant them in early 2012 and end up with tiny tubers

no more than an inch in diameter. Save those tubers and use them

as seed potatoes in 2013, and I'd finally grow potatoes large enough to

taste and test. Although the garden geek in me is itching to give

it a try, I don't think we care enough about potatoes to allot that

much space and energy to the experiment.

Filear.com has an informative

post on his new solar

powered Arduino controlled automatic chicken coop door opener.

He's got a 4 minute video

that helps to show what steps are needed to make something like this

work. I'm guessing it might cost over 150 dollars due to the solar

cell and back up battery. A bit complicated and somewhat expensive, but

a good choice for those out there who need this type of application and

don't want to run electrical power out to the flock.

Edited to add:

After years of research, Mark eventually settled on this automatic chicken door.

You can see

a summary of the best

chicken door alternatives and why he chose this version here.

If you're planning on

automating your coop, don't forget to pick up one of our chicken waterers. They never spill or

fill with poop, and if done right, can only need filling every few days

or weeks!

We suffered our 2nd deer

attack last night since last

week's power outage.

I'm thinking this time of

year calls for additional measures like moving the deterrent location a couple

times per week and making the sound louder.

We talked about dumping some

soapy water near the entrance area, but we both know that will only

last so long.

I think this level of damage

allows us to hunt the offending deer in question out of season and

a venison sandwich sounds like a yummy solution to me.

Tomatoes

can be some of the easiest vegetables to grow, but only if you have a

long, hot (but not too hot), dry (but not too dry) growing

season. We struggle with tomatoes in non-drought years because

our seemingly endless rains breed fungi that take out our crops.

I've posted about preventing tomato blights in bits and pieces before,

but I thought I'd pull all of our anti-blight measures together into

one post to make it easier for you to follow along.

Tomatoes

can be some of the easiest vegetables to grow, but only if you have a

long, hot (but not too hot), dry (but not too dry) growing

season. We struggle with tomatoes in non-drought years because

our seemingly endless rains breed fungi that take out our crops.

I've posted about preventing tomato blights in bits and pieces before,

but I thought I'd pull all of our anti-blight measures together into

one post to make it easier for you to follow along.

Plant

your tomatoes in the sunniest spot. This year, we made an

extra bed running the length of the chicken pasture just for our

tomatoes. The fence line runs from east to west on the most

northern side of the yard, so this location gets the least shade from

the hillside and the plants are least likely to shade each other.

The only slight problem with this setup is that grasses on the pasture

side of the fence poke through the chicken wire, but they don't seem to

bother the tomatoes and I yank them out when I weed.

Space

the tomatoes far apart. The distance you

choose to provide between your tomato plants will depend on your

pruning method, but the goal is to make sure there's open air between

them. We prune to three main stalks and tie the plants to a

stake, so we only need about three feet between plants. If you've

got space, more room is always better.

Stake

your tomatoes.

You may be starting to notice that all of these techniques have a

common theme --- keeping the leaves of the tomatoes dry. It's a

big no-no to let your tomatoes sprawl across the ground since they'll

take much longer to dry off after a rain or even a heavy dew.

Cages are okay, but hinder air circulation. We tie up our

tomatoes once a week to keep them climbing their stake.

Prune relentlessly. Blight spores splash

up from the ground onto tomato leaves, where the fungi grow and

reproduce, producing more spores than can spread through your whole

patch. As soon as the tomatoes are about eight inches tall, I cut

off any leaves touching the ground, a process that I repeat weekly

since the higher leaves will start to bend down as they grow

older. Meanwhile, I snip off any signs of incipient fungal damage

--- early

blight showed up at

the beginning of July, but with constant leaf removal, seems to be in

check. Finally, I remove all suckers, leaving only three main

stems. When pruning, clean your clippers with an alcohol-soaked

rag between each plant and after you cut any dicey-looking

foliage. It's okay to let healthy leaves and stems fall to the

ground, but take diseased leaves as far away as possible or burn

them. If a plant seems to be nearly all diseased, rip the whole

thing out ASAP rather than hoping you can baby it back to life.

Prune relentlessly. Blight spores splash

up from the ground onto tomato leaves, where the fungi grow and

reproduce, producing more spores than can spread through your whole

patch. As soon as the tomatoes are about eight inches tall, I cut

off any leaves touching the ground, a process that I repeat weekly

since the higher leaves will start to bend down as they grow

older. Meanwhile, I snip off any signs of incipient fungal damage

--- early

blight showed up at

the beginning of July, but with constant leaf removal, seems to be in

check. Finally, I remove all suckers, leaving only three main

stems. When pruning, clean your clippers with an alcohol-soaked

rag between each plant and after you cut any dicey-looking

foliage. It's okay to let healthy leaves and stems fall to the

ground, but take diseased leaves as far away as possible or burn

them. If a plant seems to be nearly all diseased, rip the whole

thing out ASAP rather than hoping you can baby it back to life.

Choose

resistant varieties. We've tried out dozens

of tomato varieties, but now focus on ones that are a bit more

resistant than normal to early blight, late blight, and septoria leaf

spot (our three main problems.) None of these tomatoes are

entirely immune, though, so we can't ignore them and hope for the best.

Water

from below and/or in the early morning. If you have to get the

leaves of your tomatoes wet, make sure you do it first thing in the

morning on a sunny day so that the plants will dry off as soon as

possible. I've located our sprinklers so that they don't hit the

main tomato area, but we haven't got our drip irrigation installed

yet. The plants seem to be doing fine without the extra water so

far.

Race the blight. Of our three main fungal

diseases, late

blight is the real doozy, and it tends to hit late in the season just

as the name suggests. For fresh eating, it would be great to have

ripe tomatoes all summer, but if you put away a lot of sauces, it

wouldn't hurt to try out some determinate tomatoes. This year,

over half of our total tomato planting is devoted to Martino's Roma,

which will drown you in tomatoes for a month or two and then peter

out. Another facet of racing the blight is to make sure your

plants are always growing as fast as possible by providing lots of

manure and not starting the seedlings too early (allowing them to be

stunted.)

Race the blight. Of our three main fungal

diseases, late

blight is the real doozy, and it tends to hit late in the season just

as the name suggests. For fresh eating, it would be great to have

ripe tomatoes all summer, but if you put away a lot of sauces, it

wouldn't hurt to try out some determinate tomatoes. This year,

over half of our total tomato planting is devoted to Martino's Roma,

which will drown you in tomatoes for a month or two and then peter

out. Another facet of racing the blight is to make sure your

plants are always growing as fast as possible by providing lots of

manure and not starting the seedlings too early (allowing them to be

stunted.)

And now, two blight

prevention tactics that we've tried which have failed miserably:

- Stick your head in the sand and pretend nothing's happening.

- Plant patches of tomatoes here and there and hope the blight won't reach them all.

Despite

lots of rain, we seem to be in great tomato shape this year. We

ate 2011's first tomato (a Stupice) on July 12 and have enjoyed a

tomato every other day since. The main crop is about to come in,

at which point I'll be preserving as fast as possible and quickly

forgetting that a sun-ripened tomato is a rare treat.

Despite

lots of rain, we seem to be in great tomato shape this year. We

ate 2011's first tomato (a Stupice) on July 12 and have enjoyed a

tomato every other day since. The main crop is about to come in,

at which point I'll be preserving as fast as possible and quickly

forgetting that a sun-ripened tomato is a rare treat.

The pump that we

use to irrigate the garden

stopped working last week.

Anna found out through some

internet research that laying it nearly flat in the creek may have

allowed the lubrication for the internal bearings to shift over to one

side, leaving the other side vulnerable to excess friction.

Most applications have it

working in a deep hole where it stands straight up. What you need is at

least a 15 degree angle to keep everything happy inside. I think I got

close to this by digging a hole in the creek bed so the bottom of the

pump can be at least 7 inches lower than the top.

The other improvement is a

large piece of PVC pipe that I cut down the middle and secured the pump

to. This should help to keep the working end out of the mud and

hopefully decrease the amount of sediment that gets sucked up.

Broadcasting seeds is one of my

favorite ways of planting most vegetables (with the exceptions of big

vegetables like squash, corn, beans, etc.) The method is most

appropriate for gardens with permanent beds in which you want your

vegetables to spread out and cover all of the available space. To

broadcast plant, I simply fill the palm of one hand with as many seeds

as I want to put on the bed, separate my fingers, and jiggle my arm

until the seeds bounce to the ground. Once you get the hang of

it, you can broadcast seed a bed in less than a minute and end up with

well-spaced seedlings.

Broadcasting seeds is one of my

favorite ways of planting most vegetables (with the exceptions of big

vegetables like squash, corn, beans, etc.) The method is most

appropriate for gardens with permanent beds in which you want your

vegetables to spread out and cover all of the available space. To

broadcast plant, I simply fill the palm of one hand with as many seeds

as I want to put on the bed, separate my fingers, and jiggle my arm

until the seeds bounce to the ground. Once you get the hang of

it, you can broadcast seed a bed in less than a minute and end up with

well-spaced seedlings.

The one difficulty with broadcast seeding is

that the seeds sit on the soil surface, which means trouble

germinating during hot, dry summer days. (In the spring, I

rarely have issues with germination even though I don't cover my

seeds.) But if you rake the top half inch of soil to the sides of

the bed, broadcast seed, then carefully pull that excess soil back on

top, you can have the best of both worlds --- quick seeding and

efficient germination. I tried out this method a few weeks ago

with the first of our fall carrots and was so pleased with the results

that I think it will be my new broadcast-seeding standby.

The one difficulty with broadcast seeding is

that the seeds sit on the soil surface, which means trouble

germinating during hot, dry summer days. (In the spring, I

rarely have issues with germination even though I don't cover my

seeds.) But if you rake the top half inch of soil to the sides of

the bed, broadcast seed, then carefully pull that excess soil back on

top, you can have the best of both worlds --- quick seeding and

efficient germination. I tried out this method a few weeks ago

with the first of our fall carrots and was so pleased with the results

that I think it will be my new broadcast-seeding standby.

I figured out the other day

that one of my new favorite activities is making automatic chicken

waterers with Anna.

Like many storage

vegetables, onions need a curing

period after harvest

so that they'll dry thoroughly and won't rot on the shelf. In the

past, I've laid the bulbs out on screens, but this year I wanted to

give the traditional method --- braiding --- a try.

Some of our onions are

further along than others since I tried out several planting methods

this spring. First thing in the morning, I plucked out any that had

completely or nearly dried up leaves and turned them on their side to

do a little pre-drying. The rest of the crop will come out next

week.

By afternoon, the bulbs

were dry to the touch (although some of the leaves were still

wet.) Time to braid!

Many websites will tell

you to braid around a string, and I can see the point --- you won't end

up with this:

However, as long as

you're careful, you can braid your onions with just the leaves.

Start with three onions and braid them for a couple of loops for a firm

bottom, then start adding a new onion each time you loop one of your

three lines of leaves to the center. Once you get good at it,

you'll realize that some onions have long, strong stalks while others

have short, weak stalks. You can slip the weaker-stalked onions

in when your current line looks bulky enough to last another round.

At the end, I tied a bit

of baling twine around the braided tops to give me an easy hanging

point.

As a side note, you'll

find it much easier to braid your onions if you

take them inside and work on a flat surface. Braiding in the

grass

means you tend to literally braid in the grass.

That said, braiding was

simple and fun. And the project required significantly less time

than it would have taken me to find a sheltered spot and set up my

drying screens.

I'll leave my onions in

braids for a few weeks until they're bone dry, then will cut the heads

off and store them in mesh bags on a kitchen shelf. I suspect

we'll run out of onions long before they go bad --- our total harvest

will probably clock in around 35 or 40 pounds, which should last us

about three or four months. Now that I've figured out the best

method (more on that in a later post), we'll be growing many more

onions next year!

Anna did the bulk of the

research for our new

creek pump which led us to the local Home Depot.

They

had a good selection of small to medium pumps, but no 220 volt well

pumps. I went to the front desk where the guy was grumpy and shuffled

me to the Home and Bath department instead of letting me ask the simple

question "Can you order me a pump so I can come in next week to pick it

up?" There was only one person working at Home and Bath and she was

taking care of a customer. She was nice and said she would be

with me soon. She was having some computer trouble and called Mr Grumpy

front desk back to help her. The guy actually sneered at me when

he made eye contact. I'm sure that could be a misinterpretation on my

part and my body language was sending a message that I was getting

tired of waiting by the way I was standing there with my arms crossed,

and maybe some frustration was building when my wait went past the 20

minute point?

They

had a good selection of small to medium pumps, but no 220 volt well

pumps. I went to the front desk where the guy was grumpy and shuffled

me to the Home and Bath department instead of letting me ask the simple

question "Can you order me a pump so I can come in next week to pick it

up?" There was only one person working at Home and Bath and she was

taking care of a customer. She was nice and said she would be

with me soon. She was having some computer trouble and called Mr Grumpy

front desk back to help her. The guy actually sneered at me when

he made eye contact. I'm sure that could be a misinterpretation on my

part and my body language was sending a message that I was getting

tired of waiting by the way I was standing there with my arms crossed,

and maybe some frustration was building when my wait went past the 20

minute point?

45 minutes after I entered

the store the lady was finally ready to walk over to the pumps to see

if she could help me. She confirmed that the pump was not in stock or

not in the back room and her solution was for me to order it on the

internet. I'm guessing the shipping on something this heavy is around

50 bucks or more and then you would have to turn around and pay that

again if there was a need to send it back. She offered to write down

the model number so I could take it with me. That's when I lost my cool

and calmly told her with a slight tinge of attitude "No thanks, I'll

just go to Lowe's down the street".

Lowe's had a variety of 220

volt well pumps to choose from. Our old one was a half horse power. I

decided to go up a notch to a 3/4 horsepower, which cost around 340

dollars when you factor in the connector parts.

My new

method of broadcast seeding is perfect for small autumn vegetables,

but what about the big plants like cabbage and broccoli? I

usually start three seeds per spot to make sure enough come up, then

thin, but this year I was running low on seeds and only planted one per

hole. The result was extremely spotty germination and not nearly

enough fall crucifers.

My new

method of broadcast seeding is perfect for small autumn vegetables,

but what about the big plants like cabbage and broccoli? I

usually start three seeds per spot to make sure enough come up, then

thin, but this year I was running low on seeds and only planted one per

hole. The result was extremely spotty germination and not nearly

enough fall crucifers.

Although it was a bit

late by the time I noticed the problem (the beginning of July), I went

ahead and moved on to plan B --- start broccoli and cabbage in flats

where I know I can get them to come up, then transplant into the garden

just as they get their first true leaves. It turned out that my

broccoli seeds had low germination even there, so I ordered another

batch and tried again. This last round of seeds will have to be

protected by quick

hoops if I want them

to head up, unless we get a late killing frost the way we do some years.

I seem to gamble with

broccoli a lot, and sometimes it pays off. I got spooked

by our constant rain

in the middle of May and planted a bed of broccoli as a consolation

prize if the blight took our tomatoes. So far, our tomatoes are

in good shape, but so are my summer broccoli! I guess we'll have

some fall broccoli no matter what happens with my late seedlings.

I seem to gamble with

broccoli a lot, and sometimes it pays off. I got spooked

by our constant rain

in the middle of May and planted a bed of broccoli as a consolation

prize if the blight took our tomatoes. So far, our tomatoes are

in good shape, but so are my summer broccoli! I guess we'll have

some fall broccoli no matter what happens with my late seedlings.

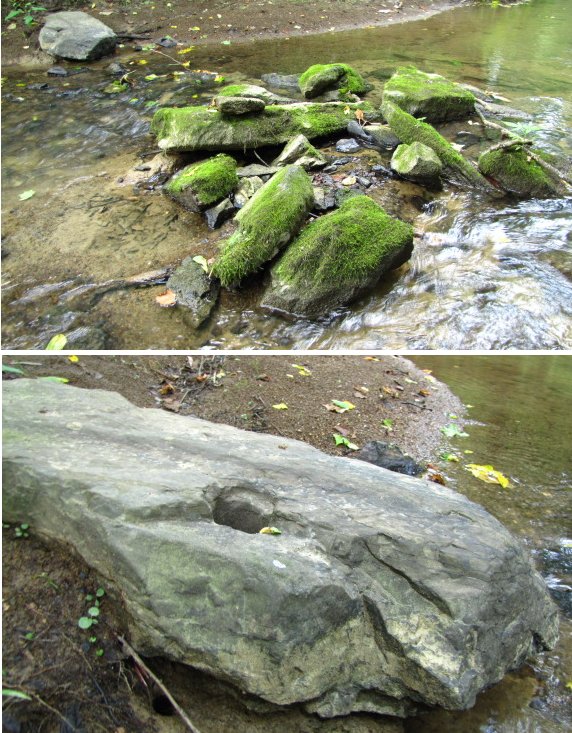

It looks like there was once

a hand made dam here in the creek next to our new

pump.

I'm guessing that the water was channeled

towards the hole that seems to have been cut out with a hammer and

chisel.

I'm guessing that the water was channeled

towards the hole that seems to have been cut out with a hammer and

chisel.

Maybe a pipe was connected at

the bottom to carry the water to some sort of mini grain mill or

rudimentary electrical generator?

It must have taken the

previous homesteaders hours upon hours of hard, back breaking labor to

carry these rocks from I'm guessing the nearby river which is an 8

minute drive away. That kind of project must have surely yielded some

sort of mechanical advantage to make it worthwhile.

One month after the

solstice, I can feel the long, slow descent into winter beginning.

We're racing the shortening days now.

Even though it seems strange

to be thinking of winter in July, we're in the middle of planting the fall

garden. I'm also putting in cover crops

(more on those in a later post) to add organic matter to beds that will

remain fallow until garlic planting time or until the spring.

It's already too late to direct seed anything except bush beans,

lettuce, greens, and garlic unless we plan to protect the crops from

frost.

Even though it seems strange

to be thinking of winter in July, we're in the middle of planting the fall

garden. I'm also putting in cover crops

(more on those in a later post) to add organic matter to beds that will

remain fallow until garlic planting time or until the spring.

It's already too late to direct seed anything except bush beans,

lettuce, greens, and garlic unless we plan to protect the crops from

frost.

Meanwhile, I'm

preserving the harvest as fast as I can. I've got 8.75 gallons of

vegetables and a gallon of fruit in the freezer, along with 0.8 gallons

of dried vegetables and 1.3 gallons of dried fruit. Although it

feels like a lot of food, I hope to freeze at least 30 gallons of

vegetables (exluding tomato sauces) this year, so we've got a long way

to go.

Even though I start