archives for 06/2011

Our

easy hive split

was a buzzing success! Both the mother and the daughter hive have

had workers flying in and out extremely busily all month, but that

doesn't really mean anything. If my hive split had failed

(meaning the queenless hive didn't manage to requeen), workers would

still go out and harvest nectar and pollen until they eventually got

picked off by predators and weren't refreshed by new bees.

Instead, I had to wait (very impatiently) for a full month and then

delve into each brood box to see what was going on down there.

Our

easy hive split

was a buzzing success! Both the mother and the daughter hive have

had workers flying in and out extremely busily all month, but that

doesn't really mean anything. If my hive split had failed

(meaning the queenless hive didn't manage to requeen), workers would

still go out and harvest nectar and pollen until they eventually got

picked off by predators and weren't refreshed by new bees.

Instead, I had to wait (very impatiently) for a full month and then

delve into each brood box to see what was going on down there.

In order to understand

the story, you have to know that each type of bee in the hive develops

along a slightly different timeline:

| Egg

(days) |

Larva

(days) |

Pupa

(days) |

Total

days |

|

| Worker |

3 |

5.5 |

12.5 |

21 |

| Queen |

3 |

5 |

8 |

16 |

| Drone |

3 |

6.5 |

14.5 |

24 |

Queens rush through their childhood and chew out of their capping within 16 days, but workers take three full weeks to mature. I checked on the bees exactly 28 days after the split and this is what I saw:

- East hive --- Small

larvae (probably no more than two or three days in the larval stage)

and eggs. (No photo because the bees got pissy.)

- Middle hive --- Lots of

capped brood, larvae, and eggs. (One frame shown above.)

Clearly, during my hive

split, I transferred the queen to the middle

hive, and she just kept plugging away at her duties (laying eggs),

which resulted in the current state with brood of all ages. In

contrast, the east hive had lost their queen, so they didn't do any

child-rearing until less than a week ago. That lines up very well

with the amount of time it would take for a queen to hatch (16 days),

mate (another few days, potentially more because of the constant rain),

and then lay the eggs that turned into the largest larvae present

(about 6 days old) --- 22 days plus whatever time her mating flight

took.

Clearly, during my hive

split, I transferred the queen to the middle

hive, and she just kept plugging away at her duties (laying eggs),

which resulted in the current state with brood of all ages. In

contrast, the east hive had lost their queen, so they didn't do any

child-rearing until less than a week ago. That lines up very well

with the amount of time it would take for a queen to hatch (16 days),

mate (another few days, potentially more because of the constant rain),

and then lay the eggs that turned into the largest larvae present

(about 6 days old) --- 22 days plus whatever time her mating flight

took.There's still a very slight chance that the new queen could have mated badly and is laying drones --- I'll know for sure next week when I see capped brood. And an even slighter chance that the eggs are being laid by workers --- unlikely since the brood pattern is so even and the eggs are in the bottom of the cells rather than on the sides. But I'm pretty confident the hive split was a success.

Since I was down so deep in the hives, I went ahead and checkerboarded both brood boxes so that the excess honey wouldn't tenpt the bees to swarm. The bees were not pleased with this intrusion, and I had to don my gloves after one stung my hand. After I know for sure that the east hive has a happy queen, I'll leave the brood box alone and focus on honey for the rest of the summer....

There's something rather glorious about a simple outdoor shower. Mark built one, here's my take.

Not as perfect as a waterfall, but more convenient. I put it together in lego mode, just snapping bits together until it seemed right. The water barrel collects the flow when the shower is not in use and also serves as ballast. I have replaced the duct taped shower head with a garden watering wand since taking the picture, as well as adding things like a soap dish.

My shower is fed down from a small spring house, using 150-some feet of hose, that drops at least 12 feet. That provides enough pressure for a good shower. Earlier this spring, there was enough water flowing to leave the hose running all the time. Now that the spring has slowed to a trickle, I turn the shower off when not in use, so it can build up a head of water in the spring house, and be ready for a nice long shower next time.

I've also found that from 10 am on, the hose heats the water enough so it's a hot shower for a few minutes, then a warm shower, before it becomes a cold springfed shower. That's perfect, it's just how I like my showers! By using a black hose this would probably even work in colder parts of the year, as a simple solar shower.

Not that the alternative isn't nice too..

Joey is an occasional guest poster and resident at the Walden Effect.

The weather has been

unusually hot this week, with highs in the 90s and record highs for our

area at the closest weather station. Monday afternoon, the

temperature inside our trailer got up over 100, setting off the high

alarm on the incubator --- now I've taken to training a fan on brood

3 during the hottest period in the late afternoon.

The weather has been

unusually hot this week, with highs in the 90s and record highs for our

area at the closest weather station. Monday afternoon, the

temperature inside our trailer got up over 100, setting off the high

alarm on the incubator --- now I've taken to training a fan on brood

3 during the hottest period in the late afternoon.

The adult hens are

spending their time resting in the shade, but the tweens have been out

and about...and so have the chicks! When we moved the

fluffballs from the house to the second coop on Sunday, I leaned a

piece of plywood against their pophole, figuring they weren't ready to

explore yet, but the youngsters knocked that down by Monday

afternoon. I figured they knew what they wanted, so I instead

used the plywood as a little ramp, and soon our youngest flock was

exploring the ragweed forest.

Other than trying to keep

ourselves cool, though, this unusually hot weather has been a

boon. After two solid months of adding items to our "must be

hauled onto the farm ASAP!" list, the driveway finally dried up enough

to allow passage. Sticking to the most important first, Mark treated me to two

truckloads of manure and a

load of straw. Meanwhile, we were able to

drive in supplies that had been building up in the parking area,

including masses of cardboard for kill mulches, bags of lawn clippings

for garden mulch,

Other than trying to keep

ourselves cool, though, this unusually hot weather has been a

boon. After two solid months of adding items to our "must be

hauled onto the farm ASAP!" list, the driveway finally dried up enough

to allow passage. Sticking to the most important first, Mark treated me to two

truckloads of manure and a

load of straw. Meanwhile, we were able to

drive in supplies that had been building up in the parking area,

including masses of cardboard for kill mulches, bags of lawn clippings

for garden mulch,  and some lumber.

Weeding has been taking up more and more of my time as last fall's

mulch melted into the soil, so I'm even more grateful than usual for my

big piles of biomass.

and some lumber.

Weeding has been taking up more and more of my time as last fall's

mulch melted into the soil, so I'm even more grateful than usual for my

big piles of biomass.

On the whole, the garden

has also been happy to see the sun. Sure, a few strawberries got

cooked on the vine and a cabbage leaf showed signs of sunscald, but I

can almost see the rest of the garden growing. We finally hooked

up the rest of the sprinklers

and are now watering in earnest to keep that momentum going.

Homegrown produce currently on the menu includes strawberries (far more

than we can eat), greens, lettuce, parsley, broccoli, snow peas, and

sugar snap peas.

I decided my previous

5 gallon automatic waterer bucket holder needed to be simplified.

2 shelf brackets, a piece of

scrap lumber, and some rope with a bungee cord tied on the end seems to

do the job quite nicely.

I've posted twice

about how

to cook an old chicken,

but in the two and a half years since then, my recipes have gained

sophistication. When it came time to cook our

mean rooster, I

earmarked most of his flesh for pizza sausage (aka Italian

sausage.) I used to think that making my own sausage sounded

scary, but lately I've decided that it's actually one of the easiest

ways of dressing up tough meat. If you plan to use the sausage in

pizza, spaghetti sauce, or gravy, there's not even any need to mess

with casings or to worry about fat to protein content. You can't

really go wrong.

I've posted twice

about how

to cook an old chicken,

but in the two and a half years since then, my recipes have gained

sophistication. When it came time to cook our

mean rooster, I

earmarked most of his flesh for pizza sausage (aka Italian

sausage.) I used to think that making my own sausage sounded

scary, but lately I've decided that it's actually one of the easiest

ways of dressing up tough meat. If you plan to use the sausage in

pizza, spaghetti sauce, or gravy, there's not even any need to mess

with casings or to worry about fat to protein content. You can't

really go wrong.

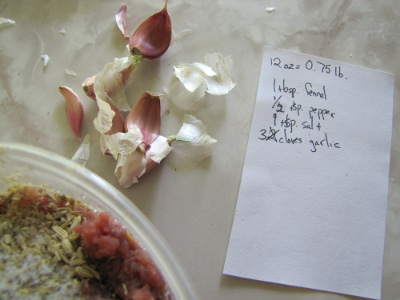

For this ultra simple

recipe, you need:

- 0.75 pounds of tough chicken meat (or any other kind of tough or not so tough meat. I've used venison, lamb, and beef hamburger, all with good results.)

1 tbsp of whole fennel seeds

1 tbsp of whole fennel seeds- 0.5 tsp pepper

- 0.75 tsp salt. (As you can see, we actually made the recipe

with a full teaspoon, but it felt a bit on the salty side.)

- 3 big cloves of garlic (or several smaller cloves)

If it's not already

ground, cut the meat off the bone and put it in the food

processor. Whir the meat up until it looks a lot like ground

meat, and if you're really using an old chicken, pick out the

connective tissue. (This will look like white, shiny lines of

dental floss. The connective tissue won't hurt you, but is

awfully tough and will be hard to chew. We give it to Lucy.)

Next,

crush the fennel seeds. If you own a mortar and pestle, I'm sure

this is a breeze, but it's not that tough even without one. I

pour out the seeds onto a large cookie sheet or a clean counter and

roll over them repeatedly with the rolling pin. You'll need to

keep pushing the uncrushed seeds into the center of the pile with your

hand until they're all crushed, so this might take two or three

minutes. Some folks put the seeds in a ziploc bag before crushing

to make the process even simpler, but then you have to throw the bag

away.

Next,

crush the fennel seeds. If you own a mortar and pestle, I'm sure

this is a breeze, but it's not that tough even without one. I

pour out the seeds onto a large cookie sheet or a clean counter and

roll over them repeatedly with the rolling pin. You'll need to

keep pushing the uncrushed seeds into the center of the pile with your

hand until they're all crushed, so this might take two or three

minutes. Some folks put the seeds in a ziploc bag before crushing

to make the process even simpler, but then you have to throw the bag

away.

Pour the crushed fennel seeds

into the ground meat along with the pepper, salt, and pressed garlic

cloves, mix well, and refrigerate for at least four hours. This

time is necessary to allow the flavors to work their way into the meat.

Pour the crushed fennel seeds

into the ground meat along with the pepper, salt, and pressed garlic

cloves, mix well, and refrigerate for at least four hours. This

time is necessary to allow the flavors to work their way into the meat.

When you're ready to use

your sausage, fry it up in a skillet on medium to high heat, stirring

often and crushing the clusters with a fork so the sausage doesn't

clump up. You might find a few more threads of connective tissue

that you missed --- pick them out. Then spread the pre-cooked

meat onto a homemade pizza and bake.

We

stewed up the bones (and residual flesh) into a simple chicken soup and

then used the rest of the flesh in the recipe above. The sausage

is a bit too much for two pizzas, so I have enough left over to add

into some homegrown omelets. All told, I figure our old rooster

served as the main course for a full fourteen people-meals.

That's not bad!

We

stewed up the bones (and residual flesh) into a simple chicken soup and

then used the rest of the flesh in the recipe above. The sausage

is a bit too much for two pizzas, so I have enough left over to add

into some homegrown omelets. All told, I figure our old rooster

served as the main course for a full fourteen people-meals.

That's not bad!

We're trying a new product

from the city of Bristol.

It's made from decomposed

leaves and it looks and feels like a quality product.

We paid a little over 50

dollars for just under 2 tons, which might end up being cheaper than bales

of straw depending on how

it socializes with the garden.

"Are you going to be mad

if I'm profligate with the

straw?" I asked Mark

tentatively on Thursday afternoon. He looked at me as if I was a

bit slow --- after all, he's the one who pushes me to buy mulch when I

say it's too expensive --- and replied: "No, if anything, you'll get

bonus kisses."

I didn't ask about the manure and cardboard because I didn't want to

give him a chance to say "No, those require a lot more work!"

Instead, once he

and the big white truck had headed into the city Friday morning, I went to

town (figuratively.) Why not hill up  potatoes with composted

manure then mulch them with straw? Those back garden beds need

some serious soil remediation anyway because the topsoil is so thin

there. Big weeds threatening to overcome some tomato plants that

haven't been weeded in two months? No problem --- lay

down a quick kill mulch of damp cardboard and then top it all off with

straw. When

quitting time came at 4 pm, I had to tear myself away from my biomass

piles.

potatoes with composted

manure then mulch them with straw? Those back garden beds need

some serious soil remediation anyway because the topsoil is so thin

there. Big weeds threatening to overcome some tomato plants that

haven't been weeded in two months? No problem --- lay

down a quick kill mulch of damp cardboard and then top it all off with

straw. When

quitting time came at 4 pm, I had to tear myself away from my biomass

piles.

When we had less cash on

hand, I frowned upon storebought mulch. But now that we can

afford it, I figure this is the kind of time-saver I can get behind

buying (at least until I come  up with a homegrown

alternative.) Not only does mulch cut down on weeding, the

biomass also breaks down into organic matter that's like money in the

bank --- mulched beds are full

of worms, and every

year the soil gets fluffier and darker. Since I can't foresee any

reason we'd ever move off the farm, building our soil is a long term

investment in our future, making gardening easier every year while the

food grown there becomes tastier and better for us. As usual,

Mark was right. (Don't let it go to your head, honey. And I

plan to collect on that bonus.)

up with a homegrown

alternative.) Not only does mulch cut down on weeding, the

biomass also breaks down into organic matter that's like money in the

bank --- mulched beds are full

of worms, and every

year the soil gets fluffier and darker. Since I can't foresee any

reason we'd ever move off the farm, building our soil is a long term

investment in our future, making gardening easier every year while the

food grown there becomes tastier and better for us. As usual,

Mark was right. (Don't let it go to your head, honey. And I

plan to collect on that bonus.)

I've finally found a motor

that is sustainable and will last longer than the previous

incarnations of this type of mechanical deer deterrent.

The above video demonstrates

the range of noise signatures that can be achieved with some adjusting

of the primary stopping point.

We've only had one minor deer

incursion this year, and we're still not sure if it was due to our recent power

failure or a particularly brave and determined deer. The system is

working quite well as you can see a very healthy and un-nibbled garden

in the background of the video.

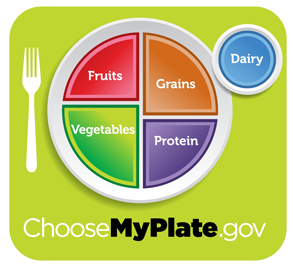

The

USDA rolled out a new visualization of their

dietary recommendations last week. After the

previous diagram (which was so painfully

difficult to get information from that I gave up on it), I was thrilled

to see that the USDA now uses the same method I do when planning dinner

--- divide the plate up into quadrants and show how much space you

should devote to each food group. (This plan is much easier to

follow at home if you plate everybody's food rather than putting bowls

on the table buffet style.)

The

USDA rolled out a new visualization of their

dietary recommendations last week. After the

previous diagram (which was so painfully

difficult to get information from that I gave up on it), I was thrilled

to see that the USDA now uses the same method I do when planning dinner

--- divide the plate up into quadrants and show how much space you

should devote to each food group. (This plan is much easier to

follow at home if you plate everybody's food rather than putting bowls

on the table buffet style.)

I'm also pleased to see

fruits and vegetables taking up a full half of the plate. I try

to make fruits and vegetables fill more like two thirds or three

quarters of our plates once you factor in dessert (strawberries and a

bit of chocolate on the side for the lunch pictured here), but I can

see how the government might  be scared to increase the

proportions so drastically from their 1980s era recommendation of 34%

of your servings being fruits and vegetables. Granted, since

serving sizes varied for each type of food in the old pyramid, the USDA

might have meant us to fill half of our plates with fruits and

vegetables all along, but I don't think that's the gist folks got from

the old diagram.

be scared to increase the

proportions so drastically from their 1980s era recommendation of 34%

of your servings being fruits and vegetables. Granted, since

serving sizes varied for each type of food in the old pyramid, the USDA

might have meant us to fill half of our plates with fruits and

vegetables all along, but I don't think that's the gist folks got from

the old diagram.

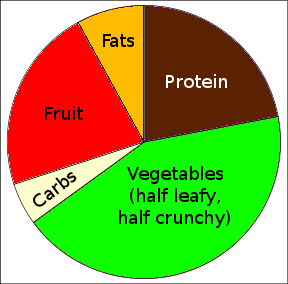

However, I have several

gripes with even this improved government recommendation:

- Why "grains" instead of "carbs"?

I know that it would take a bit more education to help people

understand what a carbohydrate-rich food is, but I think the MyPlate

chart is going to confuse a lot of people who might throw potatoes and

winter squash into the vegetable category. (I'll bet the corn

industry has a lot more lobbying power than the potato industry.)

And these confused eaters will just pretend their dessert didn't happen

since they won't know where to fit it on the plate, when they should

really be counting it into the carb category in most cases.

- Where are the fats and oils?

Most people aren't going to categorize nuts, homemade chicken broth,

and olive oil as "protein", so where will they put these fatty foods on

their virtual plate? The government website says an almond fits

in their protein group, but the percent of total calories made up by

protein in an almond is only 15%, while fat provides a whopping 70% of

the nut's energy.

- Why is dairy so special?

The more I delve into nutrition, the more I think that it's a bit odd

to make dairy its own category. (Or perhaps the milk industry is

just so powerful that they can tell Americans to drink our milk with

every meal regardless?) In fact, it makes me wonder if this isn't

the government's "fat" category, but even that is confusing since many

people drink skim milk or eat low-fat yogurt. (No, dairy is not

the only way to get calcium --- a cup of cooked greens will provide a

quarter to a half of your daily allowance, depending on variety, and

most vegetables have an appreciable amount of calcium.)

Although

it's easy to argue that government nutritional guidelines mean

nothing, I know that I learned the old food pyramd in school and strove

to incorporate the recommendations into my life. I think that

many people, like me, blindly follow the advice given by authority

figures, so it's important for those authority figures to get it right.

Although

it's easy to argue that government nutritional guidelines mean

nothing, I know that I learned the old food pyramd in school and strove

to incorporate the recommendations into my life. I think that

many people, like me, blindly follow the advice given by authority

figures, so it's important for those authority figures to get it right.

If I was in charge of

the USDA, I think my food plate would look more like the hastily thrown

together pie chart shown here. What would your ideal plate look

like?

I made another adjustment

to the tailgate latch mechanism, but it still has a tendency to

fly open if I hit a hard bump in the road.

A medium

sized ratchet strap

proved to be an easy and effective way of keeping it shut for my

trip home with the mulch.

One of the joys of working

with plants is how easy they are to propagate, even without waiting for

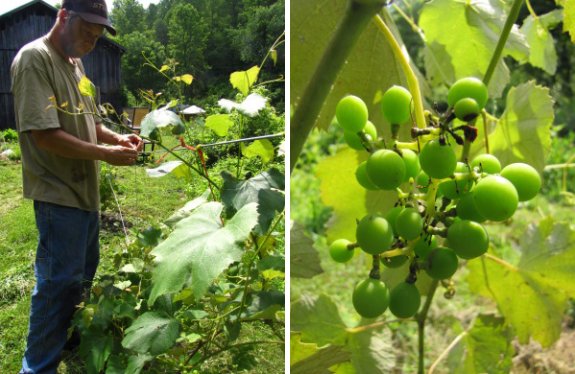

the plants to go to seed. I've posted previously about propagating

grapes from hardwood cuttings, but during the summer, the

techniques are a little different. Now the cuttings are known as

"softwood cuttings" because they consist of this year's new, flexible

growth along with the leaves, and the technique is subtly different too.

One of the joys of working

with plants is how easy they are to propagate, even without waiting for

the plants to go to seed. I've posted previously about propagating

grapes from hardwood cuttings, but during the summer, the

techniques are a little different. Now the cuttings are known as

"softwood cuttings" because they consist of this year's new, flexible

growth along with the leaves, and the technique is subtly different too.

Choose

an easy plant to propagate. I've got a windowsill

of softwood cuttings in action right now, but some are highly

experimental. The sweet

potato slips I began in a bed of gravel are one of the easiest types

of softwood cuttings --- they root in just a few days. Similarly,

I snipped off some suckers from my tomatoes when I was pruning last

week because I want a few more plants, and I expect to see roots on all

the new tomato plants shortly. I've had 17% rooting success with softwood

cuttings of rosemary

and 50% success with hardy

kiwis (although the

latter died when I didn't baby them enough in the garden.)

Currently, I'm also trying out thyme (which is supposed to be

relatively easy) and trifoliate orange (the dwarfing rootstock for

Meyer lemons.) I recommend starting with any vigorous perennial

you're in love with, as long as the original plant didn't come grafted

onto a different rootstock (a sure sign that softwood cuttings will be

difficult.)

Take a cutting with four or five

nodes. Both

softwood and hardwood cuttings need at least four nodes per cutting

(five is better) since these are the points that can grow leaves and

roots. Nodes are easily visible on dormant grapevines as bumpy

spots, and on softwood cuttings as the location where leaves are

attached to the stem. Since you can't expect every cutting to

root, you might as well increase your chances of success by taking

several.

Take a cutting with four or five

nodes. Both

softwood and hardwood cuttings need at least four nodes per cutting

(five is better) since these are the points that can grow leaves and

roots. Nodes are easily visible on dormant grapevines as bumpy

spots, and on softwood cuttings as the location where leaves are

attached to the stem. Since you can't expect every cutting to

root, you might as well increase your chances of success by taking

several.

Keep

the plants moist. Softwood cuttings are much

more sensitive than hardwood cuttings are to lack of moisture.

After all, the plants have leaves actively releasing water into the

atmosphere, so they need new water to take the lost liquid's

place. The best way to keep softwood cuttings moist is to install

misters that wet the plants (either from above or below) every minute

or two, but in the homesteading world, you can often get away with just

putting your cuttings in a glass of water. Make sure that at

least two of the nodes are below the water level at all times, and

change the water if it starts to get gunky. An alternative is to

fill a pot with moist potting soil, stick the cuttings into the dirt

two nodes deep, and then attach a transparent plastic bag over the top

of the pot. (I've had less luck with the second method because

it's tougher to harden off the plants to low moisture conditions after

they root.)

Rooting hormone increases your

chances.

You can buy rooting hormone in the store, but I like to just snip a few

twigs off the creek willow (Black Willow, Salix

nigra, but any

willow will work) and stick them in the glass with my cuttings.

Willows release a natural rooting hormone as they grow their own roots,

which will speed your more important cuttings along.

Rooting hormone increases your

chances.

You can buy rooting hormone in the store, but I like to just snip a few

twigs off the creek willow (Black Willow, Salix

nigra, but any

willow will work) and stick them in the glass with my cuttings.

Willows release a natural rooting hormone as they grow their own roots,

which will speed your more important cuttings along.

Harden

off your new plants. Once your cuttings

grow roots, you'll be tempted to toss them into the garden.

That's fine with the very vigorous rooters like tomatoes and sweet

potatoes, but I've learned the hard way that more tender perennials

need some time expanding their root network before being set out in the

hot sun. (As a rule of thumb, figure that if you had less than

90% success with rooting your cuttings, they need a hardening off

period.) Transplant your rooted cuttings into pots and put them

in a sunny windowsill (but not in a hot greenhouse), watering them

regularly. Once the plant's roots fill the pot, your cutting is

ready to go into the ground.

If you haven't already

jumped on the softwood cutting bandwagon, I strongly encourage you to

give it a try. The only downside is finding a spot in the garden

for all those vigorous plants you materialized out of thin air.

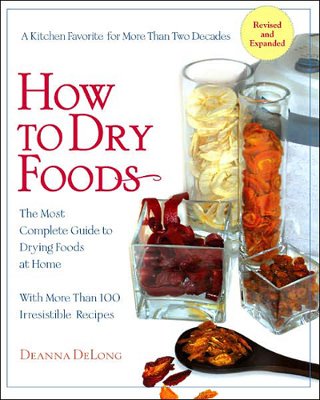

How to Dry Foods by Deanna DeLong is part

cookbook and part explanation of the whys and hows behind drying

food. The author has spent over twenty years practicing, writing,

and teaching about food dehydration, so she's able to answer all of the

questions I've been storing up as I start to consider drying more of

our winter stores. More on those answers in later posts, but

first, I feel obliged to tell you the few flaws in the book:

How to Dry Foods by Deanna DeLong is part

cookbook and part explanation of the whys and hows behind drying

food. The author has spent over twenty years practicing, writing,

and teaching about food dehydration, so she's able to answer all of the

questions I've been storing up as I start to consider drying more of

our winter stores. More on those answers in later posts, but

first, I feel obliged to tell you the few flaws in the book:

- There are ads for a single brand of dehydrator scattered throughout. I actually wouldn't have minded seeing her reviews of several different brands, but this felt more like product placement.

- She's a big fan of using sulfur to treat your fruit before dehydrating it and barely touches on alternative methods of pretreating. Some folks recommend Making & Using Dried Foods by Phyllis Hobson as a more well-rounded alternative in that department, although I haven't read it yet.

That said, I'm a big fan

of charts that sum up lots of information in a small space, and

DeLong's charts are probably worth the entire price of the book.

I actually bought an e-copy to have on hand as I experiment with drying

this summer, and I tend to only buy a few books per year, so, yes, I

recommend it.

| This post is part of our How to Dry Foods lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The pressure on our creek

pumping irrigation system turns out to be too high for the threads

on these plastic connectors. It kept popping off until I wrapped a

generous layer of plumber's tape around the threads. That fix lasted a

full year before it started popping off again.

Fast forward to the end of

this story where a metal connector seems to have no problem handling

the high pressure.

The full metal solution was

only 2 dollars compared to 49 cents on the plastic version. One new

discovery I made during this trip to the store is that Lowe's

will now give a military discount to all active duty, retired, and

veterans all year long.

10 percent is nothing to sneeze at. The only proof they need is some

sort of government issued card.

I used to dream of owning a

greenhouse. In my imagination, I would be raising tropical fruits

like pineapples, mangos, and avocados and eating fresh vegetables all

winter. I also remember the pure joy I got from walking into the

biology greenhouse when I was in college and inhaling the warm

greenness while snow coated the walk outside. At first, I figured

I'd build a greenhouse as soon as I could afford it, but now I'm not so

sure, because...

I used to dream of owning a

greenhouse. In my imagination, I would be raising tropical fruits

like pineapples, mangos, and avocados and eating fresh vegetables all

winter. I also remember the pure joy I got from walking into the

biology greenhouse when I was in college and inhaling the warm

greenness while snow coated the walk outside. At first, I figured

I'd build a greenhouse as soon as I could afford it, but now I'm not so

sure, because...

Greenhouses breed pests.

I love our dwarf

citrus, but I've noticed that once a year, the inside trees come

down with whitefly infestations. Luckily, I can just move the

trees into the garden in the spring and let natural predators deal with

the problem, but I've heard about hobbyists who completely gave up on

their greenhouses as a result of pest infestations. If you follow

natural gardening techniques, there are tons of critters, both in the

soil and in the air, working to make your garden a success, but you

have to fill all of those environmental niches yourself if you cut your

plants off inside a greenhouse. In the end, you usually have to

spray noxious chemicals or lose the growing space for good.

Greenhouses breed pests.

I love our dwarf

citrus, but I've noticed that once a year, the inside trees come

down with whitefly infestations. Luckily, I can just move the

trees into the garden in the spring and let natural predators deal with

the problem, but I've heard about hobbyists who completely gave up on

their greenhouses as a result of pest infestations. If you follow

natural gardening techniques, there are tons of critters, both in the

soil and in the air, working to make your garden a success, but you

have to fill all of those environmental niches yourself if you cut your

plants off inside a greenhouse. In the end, you usually have to

spray noxious chemicals or lose the growing space for good.- Potted plants are a lot of work.

While we're on the topic of "nature does it better", I should admit

that I consider potted plants a pain in the butt. You've probably

noticed that I start fewer plants inside than nearly any serious

gardener, and there's a reason for that --- I'd rather not mess with

reinventing the wheel when I can get nature to do chores for me.

It is possible to plan greenhouses so they're open to the earth

underneath, but then you tend to get a buildup of buildup of

salts and other problems in the soil.

- Greenhouses have to be heated. No matter how much you plan your greenhouse with passive solar techniques in mind, you're going to have to add supplemental heat in the winter if you're growing anything truly tender. Electric heat is expensive (and getting more so), and I don't think I'm willing to commit to stoking a wood stove in a greenhouse in the middle of the night. That means I'd be limited to growing spring and fall crops like broccoli and lettuce, which can be raised nearly as efficiently in a quick hoop.

Quick hoops are simpler. When I

learned that I could grow

tomato sets just as well in a quick hoop as under grow lights

inside, I was overjoyed. The more I use cold frames and similar

methods of protecting plants outdoors to give them an early jump on the

growing season, the more I think these techniques are my style.

Nature takes care of watering and I can easily move the quick hoops to

new patches of ground every season, so pests and diseases don't build

up in the soil.

Quick hoops are simpler. When I

learned that I could grow

tomato sets just as well in a quick hoop as under grow lights

inside, I was overjoyed. The more I use cold frames and similar

methods of protecting plants outdoors to give them an early jump on the

growing season, the more I think these techniques are my style.

Nature takes care of watering and I can easily move the quick hoops to

new patches of ground every season, so pests and diseases don't build

up in the soil.

- I love seasons. I

dream of the summer garden all winter, but I also love spending at

least a couple of months with no garden chores. Greenhouses

promise out of season bounty, but the truth is that I wouldn't want to

lose the building anticipation as I wait for the first strawberry or

tomato.

Which is not to say that

I might not succumb to the greenhouse bug someday, but I hope I can

stand firm!

Which is not to say that

I might not succumb to the greenhouse bug someday, but I hope I can

stand firm!

As our regular readers have

probably discovered, I'm a big fan of freezing. About 95% of our

vegetables for the year come from the garden, and the ones that aren't

fresh plucked or stored

on the shelf mostly

go in the freezer. Yes, freezers use electricity, but they also

preserve the flavor and nutrients in vegetables better than any other

method of storing food, and I put taste first. So why am I

interested in drying?

As our regular readers have

probably discovered, I'm a big fan of freezing. About 95% of our

vegetables for the year come from the garden, and the ones that aren't

fresh plucked or stored

on the shelf mostly

go in the freezer. Yes, freezers use electricity, but they also

preserve the flavor and nutrients in vegetables better than any other

method of storing food, and I put taste first. So why am I

interested in drying?

Although vegetables

taste better frozen, I've started to realize that most fruits taste

better dried. In addition, nutritional values of dried foods tend

to be on a par with frozen foods since the produce loses only some of

its vitamin A and C in the process, but maintains all other

nutrients. Drying has other advantages too, providing backup food

that doesn't depend on electricity and that takes up only a very small

amount of space.

You can dry food with

only a bare minimum of equipment, but the author of How to

Dry Foods makes it

clear that you'll end up with more nutritious, flavorful food if you

buy a dehydrator. That said, once you've bought the basic

equipment, even electric dehydrating costs very little cash compared to

the price of buying canning jar lids every year, boiling your hot water

bath canner for an hour, or running another freezer.

Food safety is the last

point in favor of drying over canning. Although dried food can go

bad, there's no hidden killer like botulism --- you'll be able to smell

or see mold growing on your food and can just toss it.

As long as you choose the foods that taste

best dried (more on that in a later post), the only real disadvantage

with drying is preparation time. There's a lot of work involved

in slicing up foods to an even thickness and laying them carefully on

the tray, and if you don't buy a top of the line dehydrator, you'll end

up spending yet more time turning trays around to dry the food evenly

and removing pieces that dried faster. That said, I'm a huge fan

of fruit leathers, which take only barely more time to prepare than

applesauce. If you like the taste of fresh fruit, it's worth

trying out drying.

As long as you choose the foods that taste

best dried (more on that in a later post), the only real disadvantage

with drying is preparation time. There's a lot of work involved

in slicing up foods to an even thickness and laying them carefully on

the tray, and if you don't buy a top of the line dehydrator, you'll end

up spending yet more time turning trays around to dry the food evenly

and removing pieces that dried faster. That said, I'm a huge fan

of fruit leathers, which take only barely more time to prepare than

applesauce. If you like the taste of fresh fruit, it's worth

trying out drying.

| This post is part of our How to Dry Foods lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Due to a very cold winter and

soil that warmed extra-slow this spring, the garden is running about a

week behind last year. That means our garlic isn't quite ready to

dig yet, but we still have four pounds left from last

year, so I'm not

terribly concerned.

Due to a very cold winter and

soil that warmed extra-slow this spring, the garden is running about a

week behind last year. That means our garlic isn't quite ready to

dig yet, but we still have four pounds left from last

year, so I'm not

terribly concerned.

I harvested

broccoli a week late

too. We'd been eating broccoli nearly every day since last

Tuesday, but the majority of the heads were suddenly in need of picking

early this week. Since I

decided to ditch the shelling peas this spring and plant broccoli in

their place, I ended

up with so many heads that they barely fit in my basket. 2.75

gallons of broccoli now in the freezer!

This week also heralded

the beginning of the year's roots. I pulled some new

potatoes from early beds planted just for that purpose and also

thinned out part of a carrot bed, saving the fingerling carrots to go

in chicken soup. I plant my carrots thick on purpose since the

seeds sometimes don't germinate evenly, and since I like being able to

harvest  little

carrots early without using up my main crop. The carrots left

behind will now have room to grow big and sweet.

little

carrots early without using up my main crop. The carrots left

behind will now have room to grow big and sweet.

Despite the slow spring

crops, it looks like our summer vegetables might be ahead of schedule

thanks to judicious quick

hoop use. I think this cucumber is going to be ready within

the week!

I've been having a lot of fun

drying

strawberry leather in an old car (22 cups of strawberry

leather preserved for winter feasts!), but there are clear downsides to

the method. Deanna DeLong summarized the pros and cons of several

different methods of drying as follows.

I've been having a lot of fun

drying

strawberry leather in an old car (22 cups of strawberry

leather preserved for winter feasts!), but there are clear downsides to

the method. Deanna DeLong summarized the pros and cons of several

different methods of drying as follows.

Oven

drying. You

can simply put your food on cookie sheets (or on cheese-cloth-covered

oven racks), turn the oven on very low, crack the door, and dry food

that way. But oven drying takes two to three times as long as

dehydrator drying (which means fewer nutrients and less flavor survives

the process) and you use a lot more electricity. You need to move

the food around often since the air flow isn't very regular, and you

often end up with areas that overheat and turn brittle. I think

that oven drying's primary use is as a backup to solar drying --- if

you have food nearly dry and suddenly the weather turns rainy, you can

finish it off in the oven.

Sun-drying. The simplest

dehydration method is to put your food on cookie sheets or screens in a

sunny spot, covering them with netting to keep off bugs. Although

easy, sun-drying is really only appropriate for climates with high heat

(highs in the 90s or above for extended periods), low humidity, and low

air pollution. If you can get away with it (mostly in the

southwest if you live in the U.S.), sun-drying is the cheapest method

and the UV light kills some microorganisms in your food. On the

other hand, sun-drying can take ten times as long as dehydrator drying

(which means fewer nutrients left at the end), and cloudy or rainy days

can ruin your food. Even in hot climates, sun-drying is only

appropriate for fruit, and you need to be prepared to poke at the

drying produce two or three times a day.

Sun-drying. The simplest

dehydration method is to put your food on cookie sheets or screens in a

sunny spot, covering them with netting to keep off bugs. Although

easy, sun-drying is really only appropriate for climates with high heat

(highs in the 90s or above for extended periods), low humidity, and low

air pollution. If you can get away with it (mostly in the

southwest if you live in the U.S.), sun-drying is the cheapest method

and the UV light kills some microorganisms in your food. On the

other hand, sun-drying can take ten times as long as dehydrator drying

(which means fewer nutrients left at the end), and cloudy or rainy days

can ruin your food. Even in hot climates, sun-drying is only

appropriate for fruit, and you need to be prepared to poke at the

drying produce two or three times a day.

Drying

in a warm room.

A few foods can be successfully dried in a warm room. These

include herbs and nuts in the shell. Be sure to set up a fan to

move moisture-laden air off the drying food.

Solar dehydrator. A solar

dehydrator like the

one we dream of building can elevate air temperature by 20 to 30

degrees Fahrenheit, so you can get away with drying food in more

temperate climates, even if you have high humidity. You're

still at the mercy of the weather and food must be rotated, but solar

dehydrators will dry food faster than sun-drying, so the food is more

nutritious.

Solar dehydrator. A solar

dehydrator like the

one we dream of building can elevate air temperature by 20 to 30

degrees Fahrenheit, so you can get away with drying food in more

temperate climates, even if you have high humidity. You're

still at the mercy of the weather and food must be rotated, but solar

dehydrators will dry food faster than sun-drying, so the food is more

nutritious.

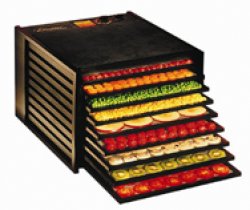

Electric

dehydrator.

A good electric dehydrator has a thermostatically controlled heating

unit and a fan, so food is dried as fast as possible (meaning maximum

flavor and nutrients.) Top of the line units heat very evenly,

too, so they're set-it-and-forget-it, and  many even come with a

timer. After doing the math on how much it would cost me to buy

enough cookie sheets to dry our excess fruit in our very variable

climate using the sun, I decided to go ahead and buy an electric

dehydrator. More on the model we chose once it arrives and we

give it a test run.

many even come with a

timer. After doing the math on how much it would cost me to buy

enough cookie sheets to dry our excess fruit in our very variable

climate using the sun, I decided to go ahead and buy an electric

dehydrator. More on the model we chose once it arrives and we

give it a test run.

Solar/electric

hybrid dehydrator.

You can get the best of both worlds (low energy usage and fast,

nutritious food) by building a solar/electric hybrid. The solar

collector heats the food on sunny days, while the thermostatically

controlled heating unit kicks on when it's cloudy and at night. A

fan keeps air flow more uniform. I dream of turning our electric

dehydrator into a hybrid unit, but Mark wants to spend a bit more time

learning how a standalone solar dehydator works first.

I think that the path I

took --- dabbling in solar dehydrating in an old car and with the oven

--- is a good beginning to see if you like the flavor of dried

food. But if you decide to make dehydration one of your main food

storage methods, you'll probably want to build a high tech solar

dehydrator or buy one of the best consumer grade electric dehydrators

(or maybe do a little of both.)

| This post is part of our How to Dry Foods lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We had a nice journalist stop

by today to interview us on some of the finer points of rural access to

broadband internet and how it can be used to generate an income.

I made an audio recording of

Anna's chicken pasture tour with the intention of seeing if it can be

turned into a short Youtube video or something like that.

Our dehydrator came in the

mail Tuesday, and I barely had it out of the

box before filling it up with food. I wanted to pull overripe

bananas and last fall's applesauce out of the freezer to make room for

the produce that's starting to pour in, and also wanted to give the

dehydrator a good test run. So I mixed up four types of

experimental fruit leather:

Our dehydrator came in the

mail Tuesday, and I barely had it out of the

box before filling it up with food. I wanted to pull overripe

bananas and last fall's applesauce out of the freezer to make room for

the produce that's starting to pour in, and also wanted to give the

dehydrator a good test run. So I mixed up four types of

experimental fruit leather:

- Apple: 2 cups of applesauce, 1 tablespoon of lemon juice, 2 tablespoons of honey

- Apple/strawberry: 0.5 cups of strawberry puree, 1 cup of applesauce, 0.75 tablespoons of lemon juice, 1.5 tablespoons of honey

- "Banana bread": 1.75 cups of mashed banana, 1 teaspoon of lemon zest

- Banana/strawberry: 0.5

cups of strawberry puree, 1 cup of mashed banana, 1 teaspoon of lemon

juice, 1 teaspoon of honey

(All measurements are

enough to make one trayful.)

Four and a half hours later,

I

was peeling the first leather off the nonstick tray inserts. My

primary objective was to make the old fruit disappear into our bellies

quickly, and I'm very happy with the experiment in that respect ---

Mark

happily nibbled on the leather without any prompting.

Four and a half hours later,

I

was peeling the first leather off the nonstick tray inserts. My

primary objective was to make the old fruit disappear into our bellies

quickly, and I'm very happy with the experiment in that respect ---

Mark

happily nibbled on the leather without any prompting.

In terms of flavor, I

don't think any of these recipes are nearly as

good as pure strawberry or peach leather, but the apple/strawberry came

close. If I only had a few strawberries and plenty of apples, I

might be tempted to eke out of my strawberries this way to make them go

three times as far. In general, I've read that apple is a good

addition to other types of leather since it helps the consistency and

stretches the fruit without adding too much flavor.

The banana and

banana/strawberry leathers were the least appealing to

both me and Mark. Banana has such a strong flavor that it

overpowered the strawberry, and it lacks the sweet/tart combo we

enjoy. We concluded that even without adding honey, the dried

banana was just too sweet. That said, Mark hasn't turned up his

nose at any of the leathers --- I think I may have found a new, healthy

snack to have on hand.

Once

I decided to spend $300 on an electric dehydrator and fruit leather

trays, I figured I'd better get my money's worth by figuring out what

else can be dried. Although many fruits and vegetables (and even

meats and fish) can be dehydrated, some dried foods taste much better

than others.

Once

I decided to spend $300 on an electric dehydrator and fruit leather

trays, I figured I'd better get my money's worth by figuring out what

else can be dried. Although many fruits and vegetables (and even

meats and fish) can be dehydrated, some dried foods taste much better

than others.

In general, Deanna

DeLong writes that vegetables often aren't worth drying. Her list

of excellent dried vegetables is very short --- garlic, onions, chili

peppers, popcorn, and tomatoes.

Vegetables that she considers good enough to dry include lima beans,

carrots, sweet corn, horseradish, mushrooms, parsley, parsnips, green

and red peppers, and sweet potatoes (as part of a leather.)

Although DeLong thinks pumpkins and winter squash are not worth drying,

I've read bloggers who swear by them, and I know my father's a fan of

dried cucumber, so it sounds like there's some

room for experimentation there.

Fruits, on the other

hand, are often excellent dried. Since I love it so much,

tomorrow's post will be entirely about fruit leather, but DeLong's top

picks for fruits dried plain include: apples, apricots, cherries,

citrus peel, dates, figs, grapes, kiwi, nectarines, peaches, pears,

persimmons, pineapples, plums, and strawberries. In fact,

the only fruits she recommends against

drying by themselves are avocados, unprocessed berries (because of the

seeds), crab apples (too sour?), guava, pomegranates (seeds again), and

quince (too sour?).

Fruits, on the other

hand, are often excellent dried. Since I love it so much,

tomorrow's post will be entirely about fruit leather, but DeLong's top

picks for fruits dried plain include: apples, apricots, cherries,

citrus peel, dates, figs, grapes, kiwi, nectarines, peaches, pears,

persimmons, pineapples, plums, and strawberries. In fact,

the only fruits she recommends against

drying by themselves are avocados, unprocessed berries (because of the

seeds), crab apples (too sour?), guava, pomegranates (seeds again), and

quince (too sour?).

Finally, if you've got a

dehydrator, you might as well put it to use for other things.

During the winter, the dehydrator makes a great place to rise bread

(set it to 80 to 85 degrees) or incubate yogurt (110 degrees.)

You can dry flowers at 130 to 150 or recrisp crackers at 160.

Reliquify crystalized honey at 120 degrees for twelve hours, or make

dog treats or a slew of craft items. And, of course, jerky is

best made in an electric dehydrator.

For those of you who've been experimenting with drying, what vegetables

do you think make the grade? What's your favorite use for your

dehydrator?

| This post is part of our How to Dry Foods lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We found a super nice guy on

Craigs list that had freshly cut bales of straw for a dollar less than

the feed store which included delivery!

He was telling me that when

his father was a young man he would camp out in these fields around

harvest time working for the local farmers to bring in the crops.

According to this guy every field from here to the river was bursting

with either corn or tobacco.

The hike would have taken his

father a full day or maybe two to get here from Nickelsville, not to

mention the elevation that would have slowed them down around the

halfway point. Sounds like the kind of coming of age ritual that would

make a good movie with the right character development and a juicy

conflict to overcome that maybe involves one or more of the farmer's

daughters.

If you're looking for large

quantities of straw for a no-till

garden (or to make a

strawbale house), it's worth starting to think about straw

season. In the past, we've bought a truckload of straw at the

feed store now and then for $5.78 per bale (factoring in tax), mostly

because I assumed people didn't really grow grains around here and thus

didn't have straw as a "waste" product. But when we started

thinking about trying to buy enough straw in one fell swoop so that we

could mulch the garden for a full year even if it sets in to raining

again and the driveway becomes impassable, I decided to check

craigslist just in case.

If you're looking for large

quantities of straw for a no-till

garden (or to make a

strawbale house), it's worth starting to think about straw

season. In the past, we've bought a truckload of straw at the

feed store now and then for $5.78 per bale (factoring in tax), mostly

because I assumed people didn't really grow grains around here and thus

didn't have straw as a "waste" product. But when we started

thinking about trying to buy enough straw in one fell swoop so that we

could mulch the garden for a full year even if it sets in to raining

again and the driveway becomes impassable, I decided to check

craigslist just in case.

It turns out that I lucked

into the spring straw season --- three farmers within an hour and a

half drive were selling rye and barley straw for anywhere from $2 to $4

per bale. We chose the most expensive straw because it came from

just down the road and the

farmer was willing to deliver all 80 bales for free. (Plus, he's the only

one who called us back.) Yes, the farmer had to unload his

trailer at the end of the driveway and we had to ferry the bales the

rest of the way home in four overflowing truckloads, but the delivery

probably saved Mark about six hours of work and $142.

It turns out that I lucked

into the spring straw season --- three farmers within an hour and a

half drive were selling rye and barley straw for anywhere from $2 to $4

per bale. We chose the most expensive straw because it came from

just down the road and the

farmer was willing to deliver all 80 bales for free. (Plus, he's the only

one who called us back.) Yes, the farmer had to unload his

trailer at the end of the driveway and we had to ferry the bales the

rest of the way home in four overflowing truckloads, but the delivery

probably saved Mark about six hours of work and $142.

To be honest, I have to

admit that the locally baled straw wasn't as tight and regular as the

industrial strawbales --- not appropriate for building with. But

since we're just going to turn it into mulch in our garden, we're

thrilled. We're already thinking ahead for the next straw season,

which our new farmer contact tells us comes in October.

Meanwhile, I just thought I'd alert those of you with gardens in need

of mulch --- now's the time to buy straw while it's cheap!

I'm sorry for anyone who

tried to load up Walden Effect in the last day or so and had

trouble! I've been trying to change my domain registrar to the

more ethical Gandi, and clearly did it wrong. Now I know better

than to mess with domain transfers and then go to bed early.

Thanks to everyone who

emailed me to make sure I knew about the problem. I hope the rest

of you didn't go into too serious withdrawal. All should be well

as soon as you can read this.

If you are new to drying and

like the flavor of dried fruit, I highly recommend starting with

leather. Fruit leather tends to be faster, easier, and tastier

than whole dried fruit because:

If you are new to drying and

like the flavor of dried fruit, I highly recommend starting with

leather. Fruit leather tends to be faster, easier, and tastier

than whole dried fruit because:

- The fruit is pureed, so you can mix in lemon juice and not worry about dipping fruits in sulfur or ascorbic acid to stop enzymes from degrading your dried food.

- I've found that it's much faster to take off the stems and skins, remove seeds or pits, and toss the fruit in the processor than to carefully slice pieces of equal thickness and lay them on the tray.

- There's no need to worry about checking (a process of piercing the skin of whole fruits like blueberries and strawberries so that moisture can escape.)

- You can run pureed berries through a foley mill and dry even very

seedy fruits like raspberries.

- Once you jiggle the tray, the puree spreads out evenly, so you don't have to pick off pieces that dry faster and seldom have to flip anything over.

- The thin layer of fruit puree dries faster than slices of fruit.

- Fruit leather is even tastier than fruit dried whole. This

is especially true since you can add a little bit of sweetening without

going through the elaborate glacé process.

I've walked you through

making peach

leather and strawberry

leather, so I won't

give step by step instructions here. Instead, here are some ideas

for making fruit leather even more exciting:

I've walked you through

making peach

leather and strawberry

leather, so I won't

give step by step instructions here. Instead, here are some ideas

for making fruit leather even more exciting:

- Mix and match fruits.

Adding applesauce to other fruits helps make low pectin fruit leathers

rollable, but you can also think about mixing fruits from a flavor

point of view. You can even add small chunks of other kinds of

fruit to the puree.

- Add seasoning. I've been adding a bit of lemon and honey to my fruit leathers, and that really helps turn them into the kind of snack Mark will drag off to his lair. I also want to experiment with adding a bit of lemon zest (1 tsp per quart of puree), and perhaps making a "butternut pie" leather with pie spices. When adding seasonings to fruit leather, though, you should be aware that a little goes a long way since the puree will dry down to a much more condensed package.

- Add garnishes. My breakfast is usually fruit and nuts, so I'm excited to try adding some seeds or chopped nuts to my leather for instant meals.

- Make fun shapes. If you've got kids in your household, DeLong suggests making fruit leather shapes by pouring puree into open-topped cookie cutters. You can remove the cutter and use it over and over as long as the puree is thick enough.

- Try vegetable leather.

DeLong has recipes for several sweet-potato-based leathers in her book,

but I'm envisioning a sun-dried tomato, garlic, and basil leather.

Aren't you just itching

to try out some new fruit leather ideas? I know I am!

| This post is part of our How to Dry Foods lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

It seems like we've reached a

pause in the rainy part of the season.

One lesson I learned this

year is that 25 gallons of gravel can come in handy when you need a

small increase in traction to get things moving again.

Do you remember how our

heroes left the path against Gandalf's advice and ended up lost in

Mirkwood? (I'm writing about The Hobbit, of course.) Finally,

they decided that Bilbo would have to climb a tree in hopes of finding

a landmark to steer toward, and our less than intrepid hobbit summoned

his courage and clambered up through the scratchy limbs until "he poked

his head above the roof of leaves" and "saw all round him a sea of

green, ruffled here and there by the breeze."

Do you remember how our

heroes left the path against Gandalf's advice and ended up lost in

Mirkwood? (I'm writing about The Hobbit, of course.) Finally,

they decided that Bilbo would have to climb a tree in hopes of finding

a landmark to steer toward, and our less than intrepid hobbit summoned

his courage and clambered up through the scratchy limbs until "he poked

his head above the roof of leaves" and "saw all round him a sea of

green, ruffled here and there by the breeze."

Well, that's how I felt

on Friday morning when I started summer

pruning our largest peach tree. Luckily for me, the

tree is short enough that the job required no climbing, but the leaves

were so dense that I had to creep underneath and then pop my head up in

little openings. I could almost imagine that I was parched and

starving, perched atop a tree in the canopy of Mirkwood --- maybe

that's why I was so hungry for lunch.

I was glad to see capped

worker brood in our new hive since that means our hive split

was definitely a success. I only lifted out the

one frame from their lower brood box to confirm the queen's activity

since the bees had been less than pleased to be poked at last

time. But, even so, I could tell that they've been working hard

because the upper brood box was heavy with dehydrating nectar.

I was glad to see capped

worker brood in our new hive since that means our hive split

was definitely a success. I only lifted out the

one frame from their lower brood box to confirm the queen's activity

since the bees had been less than pleased to be poked at last

time. But, even so, I could tell that they've been working hard

because the upper brood box was heavy with dehydrating nectar.

The mother hive was also

doing well, despite losing so many of her workers to the daughter a

month ago. The bees had plenty of uncapped honey and had already

covered over two big frames of  honey in the upper brood box

and a few small frames of honey in the super. I stole enough to extract a quart and a half since I

used up the last of my honey in our final round of strawberry

leather.

honey in the upper brood box

and a few small frames of honey in the super. I stole enough to extract a quart and a half since I

used up the last of my honey in our final round of strawberry

leather.

The only downside of a

hive split is that we won't get very much honey from either hive this

year. Maybe I can talk my movie star neighbor into giving us some

of his surplus in exchange for our "acting" on his audition tapes?

Have you ever been around

when a real pro is grilling, making his charcoal from scratch on

site? It's quite an experience.

Have you ever been around

when a real pro is grilling, making his charcoal from scratch on

site? It's quite an experience.

Meet Keyen. He

learned to barbecue from his father, and his stepson Anthony is

currently following in his footsteps. The duo seemed cool as

cucumbers despite being engaged in cooking up pork and chickens for a

horde of people in ninety plus degree heat.

They started out by making

charcoal out of split firewood. The burning logs on top were

heating the coals below, which Keyen shoveled out to fill the bottom

of his grill. He admonished me not to watch the temperature dial

on the front of the grill, but to instead keep an eye on the steam

billowing out the vents and to listen to the sizzle to make sure the

meat hadn't caught fire.

They started out by making

charcoal out of split firewood. The burning logs on top were

heating the coals below, which Keyen shoveled out to fill the bottom

of his grill. He admonished me not to watch the temperature dial

on the front of the grill, but to instead keep an eye on the steam

billowing out the vents and to listen to the sizzle to make sure the

meat hadn't caught fire.

Although no one was able

to finagle the secret recipe, Keyen started out with some sort of

spice rub, marinated the meat throughout by spraying on apple juice,

and finished with his special sauce. Here's where I tell you that

I don't like barbecue...but this meat was amazing. The whole

chickens had been split in half down their backs so that they held in

the juices, and I've never tasted such succulent chicken. But the

pork loin was even more delicious.

After an hour and a half, the

chickens were ready to go into the cooler. Since it's well

insulated, the cooler holds in the heat and lets the birds keep cooking

a little bit as they wait to be put on the table. Keyen's trick

for telling when his meat is ready to take off the grill is to twist a

leg --- if the bone pulls right out, the chicken is done.

After an hour and a half, the

chickens were ready to go into the cooler. Since it's well

insulated, the cooler holds in the heat and lets the birds keep cooking

a little bit as they wait to be put on the table. Keyen's trick

for telling when his meat is ready to take off the grill is to twist a

leg --- if the bone pulls right out, the chicken is done.

Just as I was about to

succumb to the heat and leave the grilling theater, Keyen told me

about his career as a cowboy and how he lassoed an unruly guest at his

wedding. And he wasn't even pulling my leg.

I think that if my family had

a crest, it would have an Egyptian onion

smack dab in the middle. So I thought you'd enjoy this video that

my mother and sister cooked up between them walking you through the

anatomy of the Egyptian onion while also telling how the Egyptian onion

entered our lives.

What got left on the

cutting room floor was the tale of how, when my

grandmother enthusiastically carried these "round trip onions" all the

way home to Massachusetts from Virginia, her sister smiled and

nodded. You see, my aunt Ruth (who

wrote for Organic Gardening) had been growing Egyptian

onions in

her garden next door all along.

Perhaps Egyptian onions

are just prone to being overlooked. My

own father only started cooking with them last year when I treated him

to a start from my garden's excess. Now, he's turned into an

Egyptian onion pusher too. Meanwhile, Mark's mother also got some

bulblets from

me a couple of years ago and is doing her best to populate the

entire state of Ohio. What's not to love about Egyptian onions?

Our Cochin hen just decided

to go broody on us yesterday, which is perfect timing as the latest incubation

generation comes online.

The plan is to sneak the new

chicks in with Ms. Broody tonight and hopefully she'll wake

up with her biological clock still ticking and ready to shift into

mother hen mode.

I used a plastic milk carton

looking thing called a "File Crate"

for the new and improved nest box complete with chick friendly access

ramp.

"It

seems like you spend so much time worrying over the incubator, you

would have been better off ordering chicks through the mail," my father

said after I wrote about my chick-hatching

rollercoaster.

"It

seems like you spend so much time worrying over the incubator, you

would have been better off ordering chicks through the mail," my father

said after I wrote about my chick-hatching

rollercoaster.

In the short term, he

was right. Raising our own chicks isn't worth all the sleepless

nights and emotional highs and lows. On the other hand, by hatch

three, the only reason I woke up in the night is because four chicks

were hatching very loudly three feet away from my pillow at 2 am.

I like to peruse our blog archives and am

always amused to read about how tough various tasks were the first few

times we did them. Killing

chickens and extracting

honey were initially

traumatic, but now an

evening of chicken-plucking is restful, and I didn't

think twice about snagging

a couple of quarts of honey from the hive last

week. Ditto with waiting for chicks to poke their way out of the

shell or even deciding that a troubled chick needs to be helped

or euthanized.

In the end, self-sufficiency and "job" satisfaction are worth being

sent for a loop the first few times I try a new skill.

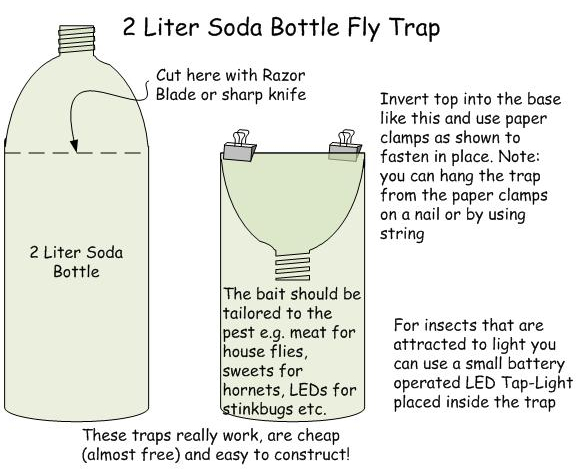

Duncan sent me this plan

for a nearly free, homemade fly trap that he made out of a plastic soda

bottle. The top of the bottle turns into a slippery funnel down

which the insects slide into the trap zone. Although a few might

find their way back out the small opening, it looks like in practice

most insects aren't that smart.

Duncan's goal was to

keep down flies that sprang up around his chickens, but I can envision

using the same setup as a homemade Japanese beetle trap and others on

the internet use it to catch stinkbugs. Since chickens are at the

top of my mind, I'm tempted to make a trap like this with a solar LED

light at the bottom to snag nocturnal insects to feed the

chickens. (The only thing holding me back is the lack of plastic

soda bottles in our trailer at the moment!)

Duncan's goal was to

keep down flies that sprang up around his chickens, but I can envision

using the same setup as a homemade Japanese beetle trap and others on

the internet use it to catch stinkbugs. Since chickens are at the

top of my mind, I'm tempted to make a trap like this with a solar LED

light at the bottom to snag nocturnal insects to feed the

chickens. (The only thing holding me back is the lack of plastic

soda bottles in our trailer at the moment!)

For more tantilizing

inventions, read about Duncan's wheel

lift for a chicken tractor and his heated

PVC pipe chicken waterer on our chicken blog. You can also see his beautiful, homemade musical instruments on his website.

When I notice a landscaping

crew working a job site most of the time the weed eater guy is using a

Stihl.

It was this observation along

with my neighbor's recent round of research that led me to choose the

Stihl FS-90R weed eater.

Stay tuned for a full report

after I've had a chance to see how well it cuts the mustard.

Chicks are very cute on day

1, but by day 2, I'm heartily wishing they

were all grown up and able to take care of themselves. That's why

we decided to take the risk of slipping our

newest eleven under

the

broody hen. We knew there was a chance some or all of

the chicks would die if the mother hen rejected them, but we've been

losing

nearly a quarter of our motherless birds to predators/power outages in

the first month anyway, so she can probably do the job better.

Mostly, though, the chance of foisting off motherhood on someone else

was irresistable.

Chicks are very cute on day

1, but by day 2, I'm heartily wishing they

were all grown up and able to take care of themselves. That's why

we decided to take the risk of slipping our

newest eleven under

the

broody hen. We knew there was a chance some or all of

the chicks would die if the mother hen rejected them, but we've been

losing

nearly a quarter of our motherless birds to predators/power outages in

the first month anyway, so she can probably do the job better.

Mostly, though, the chance of foisting off motherhood on someone else

was irresistable.

The best time to introduce

chicks to a broody hen is in the evening,

after she's been sitting tight on the nest for at least a couple of

days. You're banking on the fact that chickens can't count,

either time or eggs. If she wakes up in the morning with eleven

youngsters peeping amid her feathers, she'll just assume they hatched

out of the one egg she's been sitting on for a mere three days.

Of course, the chicks need to be young enough for this to be at least

vaguely believable, so don't try to toss those two week olds under your

broody hen.

The best time to introduce

chicks to a broody hen is in the evening,

after she's been sitting tight on the nest for at least a couple of

days. You're banking on the fact that chickens can't count,

either time or eggs. If she wakes up in the morning with eleven

youngsters peeping amid her feathers, she'll just assume they hatched

out of the one egg she's been sitting on for a mere three days.

Of course, the chicks need to be young enough for this to be at least

vaguely believable, so don't try to toss those two week olds under your

broody hen.

Our hen was setting in a

plastic egg crate we'd tossed in the coop as a nest box and never

modified, and when we tried to move her to Mark's more chick-friendly

brood box on Monday

night, she threw a fit and I let her return to her old nest box.

As a result, we had to make the box switch at the same time we

introduced the chicks on Tuesday night, and the broody hen was not

pleased. After taking a nice chunk out of Mark's gloves as he

lifted  her onto the cluster of

chicks in the new brood box, she proceeded to peck at the chicks

peeking out from beneath her feathers until they squeaked in

pain. Still, it was nearly dark, and soon she couldn't see to

peck, so we crossed our fingers and went to bed.

her onto the cluster of

chicks in the new brood box, she proceeded to peck at the chicks

peeking out from beneath her feathers until they squeaked in

pain. Still, it was nearly dark, and soon she couldn't see to

peck, so we crossed our fingers and went to bed.

I figured the test would

come at dawn, so I slipped outside as soon as it grew light and padded

to the chicken coop. Ms. Broody was awake, and so were the

chicks, with several pecking at the surrounding straw while keeping

their  bodies warm underneath the

white feather blanket. I was glad to finally hear motherly

clucking coming from the broody hen and being answered by soft chick