archives for 05/2011

Mark

and I have had to make the hard decision to call our worm

bin project a

failure. Many of the problems have or could be fixed --- the bad

smell resulting from Lucy breaking into the compost

bin repeatedly and

uncovering the scraps (solved), the trashy look and nastiness when Lucy

broke into the food bags before they went into the bin (solved), the

rat that made a home in the worm bin (solved), the flies that laid their

eggs in the compost bin at the advent of hot weather (solvable), the

"eww" factor when opening bags of old food scraps (solvable.) The

insurmountable problem is time.

Mark

and I have had to make the hard decision to call our worm

bin project a

failure. Many of the problems have or could be fixed --- the bad

smell resulting from Lucy breaking into the compost

bin repeatedly and

uncovering the scraps (solved), the trashy look and nastiness when Lucy

broke into the food bags before they went into the bin (solved), the

rat that made a home in the worm bin (solved), the flies that laid their

eggs in the compost bin at the advent of hot weather (solvable), the

"eww" factor when opening bags of old food scraps (solvable.) The

insurmountable problem is time.

Over

the last two months, I estimate that Mark and I have put in about

twenty hours picking up food scraps and doing worm

bin maintenance (not

counting the startup time.) In exchange, we've netted 1,226

pounds of food scraps, which I suspect might break down into about a

cubic yard of compost. To put that in perspective, it takes Mark

about two hours to shovel two cubic yards of amazing

horse manure

(basically worm castings) into the truck, or about three hours to drive

to town to pick up a similarly sized load of compost. Comparing

our worm bin project to these alternative methods of getting compost,

I'm afraid the juice just isn't worth the squeeze.

Over

the last two months, I estimate that Mark and I have put in about

twenty hours picking up food scraps and doing worm

bin maintenance (not

counting the startup time.) In exchange, we've netted 1,226

pounds of food scraps, which I suspect might break down into about a

cubic yard of compost. To put that in perspective, it takes Mark

about two hours to shovel two cubic yards of amazing

horse manure

(basically worm castings) into the truck, or about three hours to drive

to town to pick up a similarly sized load of compost. Comparing

our worm bin project to these alternative methods of getting compost,

I'm afraid the juice just isn't worth the squeeze.

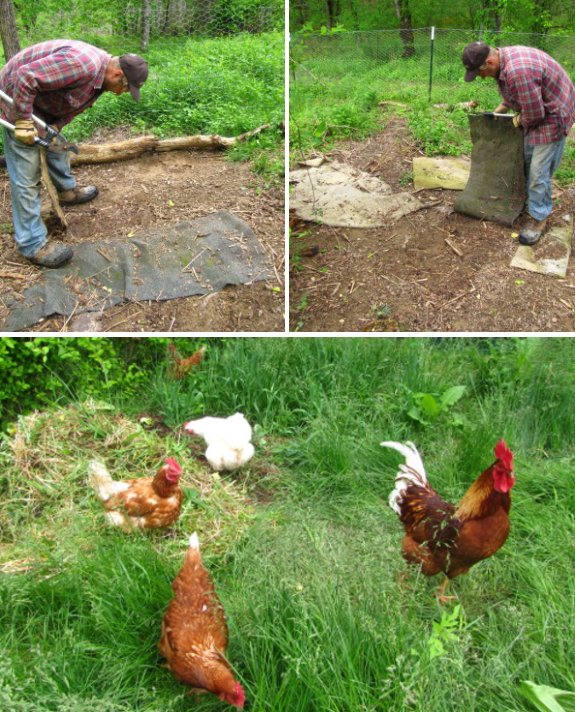

When

we embarked on the project, we had figured we'd feed some of the scraps

to our chickens, discovering just in time that we were going to be

breaking the law. If that had been possible, I suspect the food

scrap project would have been a success. The food scraps would

have been more valuable, replacing expensive storebought chicken feed

and the chickens would have dealt with rats, Lucy, and flies.

Alternatively, for folks who drive to school every day to pick up their

kids, the food scraps would have been fresh with less of a gross factor.

When

we embarked on the project, we had figured we'd feed some of the scraps

to our chickens, discovering just in time that we were going to be

breaking the law. If that had been possible, I suspect the food

scrap project would have been a success. The food scraps would

have been more valuable, replacing expensive storebought chicken feed

and the chickens would have dealt with rats, Lucy, and flies.

Alternatively, for folks who drive to school every day to pick up their

kids, the food scraps would have been fresh with less of a gross factor.

Although we're calling

it quits on collecting the school's food scraps, we aren't giving up on

worms. Now that the bin is rat-proof and the worm population is

expanding, I plan to give less-composted horse manure to the worms to

turn into castings. I suspect there will be no shortage of food

for our livestock.

Old cardboard boxes have

found a place in our forest gardening plans as a cheap source of mulch.

We save all our household

cardboard and then get a decent amount from our chicken waterer business,

but it wasn't enough for Anna, and back in the winter she started

wondering where we could get more.

I went around to several

local retail stores and found out there is a new policy where stores

pack up their discarded boxes and ship it all back to the original

warehouse. That put a crimp in our cardboard mulching plans until

Kenneth, the super nice maintenance man at the local school where we

tried our worm experiment asked if we could use any "pasteboard",

which is what some folks call cardboard around this area.

They had a truckload and I

started getting more each time I went to pick up the food scraps for

the worm bin. I'm not sure what other places do with their waste

cardboard, but it might be a good source of mulch if you have a school

in your neighborhood.

I'm a big fan of autumn

cover crops

(especially oats and oilseed

radishes), but I'm

starting to feel like cover crops in the spring are more worry than

benefit. The trouble is that most of the fall crops that didn't winter-kill (annual

ryegrass and barley) and the cover crops I'm trialing this spring (oats and

field peas) don't

mow-kill very well. As the main spring planting date approaches,

I've ended up having to resort to more time-consuming measures to get

these cover crops out of the way without tilling.

At the end of March, I cut

the barley and ryegrass as close to the ground as

possible and topped the beds off with an inch of manure and then a

heavy coating of mulch. This method was 95% effective for the

barley and about 75% effective for the ryegrass, although in both cases

the beds developed a ring of living cover crops (easy to mow repeatedly

and turn into part of the aisles.) I was left hand-weeding the

plants that were still poking up out of the middle of beds, a process

that is quite easy with barley but nearly impossible with

ryegrass. I suspect I may have to resort to a kill mulch to get rid of the ryegrass,

which won't be a big deal since I've planned late potatoes to go in

those beds and they'll enjoy the extra organic matter. Still,

it's a bit nerve-wracking to see greenery where I need to plant

shortly, especially since two months of flooding means we still can't

drive the truck off the farm to pick up more compost and mulch.

Our

spring oats and field peas bounced right back when I tried to mow-kill

them, but since I'd put the beds' compost down when planting, I didn't

have enough allotted to smother these spring beds the way I did the

overwintering fall cover crops. Instead, I've been ripping up the

oats and peas and laying them sideways and upside down across the bed

--- pretty easy since oats come out of the ground without much

effort. The beds that I dealt with during a hot, dry spell now

have a straw-like mulch of dead oats on top, but I might have to reweed

the beds I dealt with during a rainy period.

Our

spring oats and field peas bounced right back when I tried to mow-kill

them, but since I'd put the beds' compost down when planting, I didn't

have enough allotted to smother these spring beds the way I did the

overwintering fall cover crops. Instead, I've been ripping up the

oats and peas and laying them sideways and upside down across the bed

--- pretty easy since oats come out of the ground without much

effort. The beds that I dealt with during a hot, dry spell now

have a straw-like mulch of dead oats on top, but I might have to reweed

the beds I dealt with during a rainy period.

Luckily, all of the

extra mulching we did this fall means the other garden beds are in

prime condition and I have time to mess around with experimental cover

crops. Once again, Mark was right --- it was worth every penny we

spent on mulch last year!

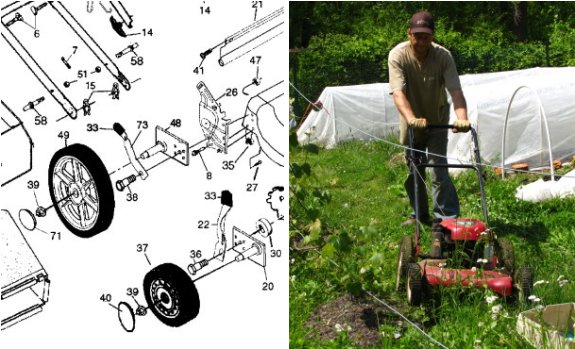

The walk behind mulching

mower still has a rear

wheel wobble due to a

parts mix up at the warehouse.

It only took about 10 minutes

to talk to a real person at Sears parts direct and I'm happy to report

the process of reporting the mistake was quick and painless thanks to a

very competent operator by the name of Fernando.

They said it would cost more

to ship the wrong wheel back to them and I should just keep it. Not

sure what I'll use it for, but this policy went a long way in helping

me to feel like a satisfied customer that will now patiently wait till

Thursday before they can ship out a proper rear wheel. In the meantime

I'll just roll with the wobble.

On

April 21, our

hive had four full frames of brood, and I figured it might take

them about a week to reach the six frames I needed for an even

split. When

the week was up, though, the weather turned windy and rainy, so I

didn't get back into the hive until eleven days later...at which point

there were a whopping eight frames of brood!

On

April 21, our

hive had four full frames of brood, and I figured it might take

them about a week to reach the six frames I needed for an even

split. When

the week was up, though, the weather turned windy and rainy, so I

didn't get back into the hive until eleven days later...at which point

there were a whopping eight frames of brood!

I brushed dead bees out

of one of the hives

that perished over the winter and filled the brood box up

with two frames of pollen, five frames of brood (two of which were

halfway honey), and three frames of honey. I didn't bother

brushing any bees into this new brood box because there were scads of

workers along for the ride already, especially once I took a whole

super of honey (full of more bees) off the top of our healthy hive to

add to its daughter hive.

The workers who were out

foraging when I messed up their home will all go back to the old hive,

and

any foragers who I carried to the new hive during the split will

probably drift back there as well. That's no big deal, though,

because

I included extra honey in the young hive to make up for the lack of

foragers. I also made sure that there's plenty of capped brood in

the young hive that

will hatch into new foragers within a couple of weeks, so they'll be

socking away honey before long.

When doing an even hive

split, you don't have to find the queen, so I don't know whether she's

still hanging out in the old hive or has moved in with the newcomers in

the young hive. Wherever she's at, that hive will soon be back to

normal, gathering nectar and pollen from the big producers that are

about to bloom (black locust and tulip-tree). Meanwhile, the

queenless hive will be set back about three weeks as the bees figure

out they're queenless (a day or two), earmark a few of the eggs as

royalty (one to three days), feed the new princesses royal jelly during

their 5 day larval stage, and wait out their eight day pupal

stage. Queenless hives usually hedge their bets by making more

than one queen cell, but the queen who emerges from her capping first

will systematically kill her competitors. She soon goes on a

mating flight and then starts laying, bringing the hive back into

production.

When doing an even hive

split, you don't have to find the queen, so I don't know whether she's

still hanging out in the old hive or has moved in with the newcomers in

the young hive. Wherever she's at, that hive will soon be back to

normal, gathering nectar and pollen from the big producers that are

about to bloom (black locust and tulip-tree). Meanwhile, the

queenless hive will be set back about three weeks as the bees figure

out they're queenless (a day or two), earmark a few of the eggs as

royalty (one to three days), feed the new princesses royal jelly during

their 5 day larval stage, and wait out their eight day pupal

stage. Queenless hives usually hedge their bets by making more

than one queen cell, but the queen who emerges from her capping first

will systematically kill her competitors. She soon goes on a

mating flight and then starts laying, bringing the hive back into

production.

That's assuming all goes

well. I'm keeping my fingers crossed that within a month, we'll

have two fully active hives instead of one.

One of the lessons learned

from the worm bin experiment is the awesome mulch

making power of a good sized strip cut paper shredder.

The Fellowes PS-60 strip cut

paper shredder has proven itself over the last 4 months to be one heck

of an addition to our permaculture infrastructure.

It might qualify as an

entertainment device judging by how much fun Anna seems to have

generating these piles of mulch. Come to think of it I've never had a

chance to give it a spin due to that chore always ending up on her to

do list instead of mine.

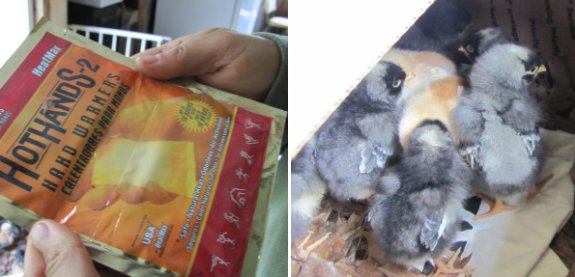

I'm trying hard not to get my

hopes up too high about incubation

batch #2, but the

stars seem to be aligned this time around. The temperature

control on our new Brinsea

Octagon 20 Advance incubator makes our previous incubator look like a

toy. Despite external temperatures near freezing over the weekend

and trailer temperatures around 50, the incubator temperature didn't

change by more than 0.1 degree! For the sake of comparison, the Brinsea

Mini Advance internal temperature dropped down 5.6 degrees

when the trailer temperature plummeted to 40 one night last time

around, and the Mini incubator always seemed to be running a bit low

even on normal nights.

I'm trying hard not to get my

hopes up too high about incubation

batch #2, but the

stars seem to be aligned this time around. The temperature

control on our new Brinsea

Octagon 20 Advance incubator makes our previous incubator look like a

toy. Despite external temperatures near freezing over the weekend

and trailer temperatures around 50, the incubator temperature didn't

change by more than 0.1 degree! For the sake of comparison, the Brinsea

Mini Advance internal temperature dropped down 5.6 degrees

when the trailer temperature plummeted to 40 one night last time

around, and the Mini incubator always seemed to be running a bit low

even on normal nights.

Meanwhile, I've gotten

scientific about humidity control in the incubator and am right on

track to make the eggs lose 13% of their weight over the incubation

period. (Every time I think about this, I feel like I've enrolled

my eggs in a weight loss program --- weight watchers, maybe?) I'm

learning to keep the night-time humidity in the low 40s and the

day-time humidity in the upper 40s, and am weighing the tray of eggs

every other day to monitor progress.

Meanwhile, I've gotten

scientific about humidity control in the incubator and am right on

track to make the eggs lose 13% of their weight over the incubation

period. (Every time I think about this, I feel like I've enrolled

my eggs in a weight loss program --- weight watchers, maybe?) I'm

learning to keep the night-time humidity in the low 40s and the

day-time humidity in the upper 40s, and am weighing the tray of eggs

every other day to monitor progress.

I'm hoping for 7 living

chicks from this batch of 24 eggs, but, secretly, I'm expecting double

digits as long as nothing drastic happens in the next two weeks.

Now, if only I could listen to ancient words of wisdom and not count my

chickens before they hatch.

This piece of land won't

put you right next door, but you'll be just over 2 hours away.

Everett and Missy have decided to move closer to town and are putting

their 15 acre farm (with house, barn, and several outbuildings) on the

market for $195,000. Visit their

blog to see contact

information and scads of pictures of the stuff most of you are probably

interested in --- they've fixed the place up so that it's beautiful and

energy efficient.

What

they don't tell you is that the farm is ready to grow all of your own

food. There's an ancient vineyard and two mature (and delicious)

apple trees leftover from previous owners. Everett and Missy have

the chicken coop in perfect repair, right beside a large pasture ready

for your goats, cows, or sheep. There's also a new no-till garden

patch already

planted --- how's that for immediate gratification?

What

they don't tell you is that the farm is ready to grow all of your own

food. There's an ancient vineyard and two mature (and delicious)

apple trees leftover from previous owners. Everett and Missy have

the chicken coop in perfect repair, right beside a large pasture ready

for your goats, cows, or sheep. There's also a new no-till garden

patch already

planted --- how's that for immediate gratification?

The farm is located in a

slightly ritzier part of southwest Virginia than we're in, which means

more like-minded neighbors (but probably steeper taxes.) They're

also a bit higher in elevation than us, so figure on better apples and

worse peaches.

The farm is located in a

slightly ritzier part of southwest Virginia than we're in, which means

more like-minded neighbors (but probably steeper taxes.) They're

also a bit higher in elevation than us, so figure on better apples and

worse peaches.

If you've got a bit of a

nest egg and are looking to move back to the land without starting from

square one, this farm might be just right for you.

The scrap pieces of carpet

from taking

apart one of the chicken tractors are making a good hotel for worms

to visit during the night.

Due

to this year's warm spring, we planted a lot of summer crops very

early. Just as the tender seedlings began to poke through the

soil, dogwood winter came along to nip their

toes. Good thing I save old, holey row cover fabric to make

emergency blankets for early birds.

Due

to this year's warm spring, we planted a lot of summer crops very

early. Just as the tender seedlings began to poke through the

soil, dogwood winter came along to nip their

toes. Good thing I save old, holey row cover fabric to make

emergency blankets for early birds.

Our tomatoes, melons,

and cucumbers didn't need any extra love, already snug in their quick

hoops. These hefty tomato

seedlings are

itching to be transplanted to their new homes (or at least to be

weeded.) First thing next week the lows will be in the 50s and I

suspect the last chance of frost will have passed...as long as there's

no blackberry winter.

5 years ago we put up a

barbed wire fence on a limited budget.

One of the corners we cut was

using several walnut posts because we ran out of cedar and spent most

of the budget on 2 rolls of barbed wire and a new chain for the

chainsaw.

Fast forward to today when I

spent the afternoon taking part of that fence out and you can see why

walnut is a poor choice to use as a fence post. It's still a solid

piece of wood above ground, but each one I tried to remove ended up

breaking off at the base. If I had to guess I'd say a walnut post can

be expected to fail somewhere between 3 and 5 years, maybe more in a

dryer climate.

We

have a couple of hundred garden beds that have each been treated

differently over the years, so it's a bit daunting to consider running

soil tests on them all. Luckily, there are quick and dirty,

at-home tests you can do to get an idea of the state of your

soil. My favorite is the worm test, which gives you an idea of

overall soil health (with a strong focus on organic matter.)

We

have a couple of hundred garden beds that have each been treated

differently over the years, so it's a bit daunting to consider running

soil tests on them all. Luckily, there are quick and dirty,

at-home tests you can do to get an idea of the state of your

soil. My favorite is the worm test, which gives you an idea of

overall soil health (with a strong focus on organic matter.)

To do a worm test the

right way, wait until the soil is at least 55 degrees Fahrenheit and is

damp but not sopping wet. Then dig out one cubic foot of soil ---

make a square on top of the ground one foot on each side and dig down

one foot deep. Put the dirt in your wheelbarrow or on a piece of

cardboard and root through it, counting worms as you go. If you

find at least ten worms, your soil passes the test, and more worms

means better soil. For really scientific results, repeat the worm

test in several parts of your garden that have all been treated the

same way and average your results.

Alternatively, there's my

method of doing a worm test. As you play in the dirt, planting

potatoes or ripping up weeds, keep an eye on how many worms you

see. This spring, I noticed that the amazing

horse manure compost

Mark got for me is a worm magnet --- one small handful of

compost-treated soil can hold as many as six hefty worms! On the

other hand, the imperfect

chicken manure compost

that I used last year to create new,

no-till beds for our tomatoes is nearly worm-free.

(The tomatoes didn't seem to mind.)

Alternatively, there's my

method of doing a worm test. As you play in the dirt, planting

potatoes or ripping up weeds, keep an eye on how many worms you

see. This spring, I noticed that the amazing

horse manure compost

Mark got for me is a worm magnet --- one small handful of

compost-treated soil can hold as many as six hefty worms! On the

other hand, the imperfect

chicken manure compost

that I used last year to create new,

no-till beds for our tomatoes is nearly worm-free.

(The tomatoes didn't seem to mind.)

If your soil is low on

worms, there could be several problems. In the case of my

imperfect compost, I suspect that high salts are responsible for

turning the area into a worm-free zone, and worms will also die if your

soil is consistently too wet, too dry, too acidic, or too

alkaline. On the other hand, worms adore mostly decomposed

organic matter (aka compost) and the damp soil underneath mulch (and

no-till gardens in general.) Since worms

do so much good in your soil, it's worth thinking of ways

to keep them happy.

This handsome frog has taken

up residence in our 5

gallon bucket solar shower drainage area.

I've noticed him for weeks

now, but each time I walk by he jumps back into his safe spot under the

old pallet.

Today was the first time I

got a good look at his features. Anna looked him up and confirmed he's

a green frog. It feels like a good omen to have a frog as a neighbor

and it gives me a smile everytime I walk by and hear him belly dive

back to his mini pond.

"We're not babies anymore, you know," the chicks

complained Friday. "Don't you think it's about time you let us

leave our room?"

"Okay, okay," I

conceded, peeling back the wall of cardboard I'd used to separate the

chicks from the rest of the coop. Within seconds, intrepid

youngsters had figured out how to jump through the holes in the trellis

gate and were exploring their new domain. Chaos ensued as the

chicks took dust baths, scratched up worms, snagged gnats in mid-air,

and even poked their beaks out the pophole into the pasture. (The

wide world was a bit too scary, though, so they scampered back inside.)

"What's all this ruckus

about?" asked the young golden comet.

A flurry of wings and

cheeps later, every chick had darted back behind the gate.

"Nothing to see here, I guess," said the hen, turning to go back

outside.

"But, wait! What's

that little fuzzball?"

"Hello?

Hello? Is somebody over there?"

"Maybe we're not old

enough to play with the big kids yet after all," the chicks declared,

settling down for a rest.

"You know best," I

answered, rolling my eyes. "Just remember, the

brooder belongs to a new batch of chicks in a week and a half."

Nobody answered. I

guess two and a half week old chicks still need naptime.

I never really understood the

purpose of chili since I don't like spicy food or cooked green peppers

(and used to detest hamburger meat when I only ate the cheap

stuff.) But as we've been increasing the

protein content of our diets and decreasing the carbohydrates, I discovered that there are

chilis that push my cooked tomato buttons without being full of empty

carbohydrates. Plus, if you make it yourself, you can keep the

spiciness mild, leave out the green peppers, and use pastured

meat. This recipe serves 5.

I never really understood the

purpose of chili since I don't like spicy food or cooked green peppers

(and used to detest hamburger meat when I only ate the cheap

stuff.) But as we've been increasing the

protein content of our diets and decreasing the carbohydrates, I discovered that there are

chilis that push my cooked tomato buttons without being full of empty

carbohydrates. Plus, if you make it yourself, you can keep the

spiciness mild, leave out the green peppers, and use pastured

meat. This recipe serves 5.

- 1 pound of dried great northern beans

- 6 cups of homemade chicken stock. (Boil a chicken carcass

in water for a few hours and pour off the liquid to get stock.)

- 1 pound of ground lamb

- 2 onions

- 4 cloves of garlic

- 1 tbsp chili powder

- 1 tsp fresh thyme (or half as much dried oregano. Our thyme

is always ready to eat and tends to taste better than our oregano, so I

use it for everything.)

- 1 tsp salt

- 0.25 tsp pepper

- 4 cups of homemade spaghetti sauce (or about 8 cups of stewed tomatoes, 1 onion, three cloves of garlic, and some basil)

Soak the beans

overnight, then pour off the water. Add the chicken stock to the

beans and simmer until the beans are soft (about two or three hours.)

Strain the beans through a

collander, tossing the liquid in a big pot along with one cup of the

beans. Freeze the rest of the beans for later meals.

(Clearly, you could have just started with fewer beans, but I've found

that I'm far more likely to add beans to a recipe if I have them cooked

up. Also, the bits of bean left in the stock thicken the chili

without requiring you to add cornstarch.)

Strain the beans through a

collander, tossing the liquid in a big pot along with one cup of the

beans. Freeze the rest of the beans for later meals.

(Clearly, you could have just started with fewer beans, but I've found

that I'm far more likely to add beans to a recipe if I have them cooked

up. Also, the bits of bean left in the stock thicken the chili

without requiring you to add cornstarch.)

Meanwhile, sautee the

lamb in a skillet until it's about halfway cooked (adding stock as

necessary to keep the meat from sticking to the pan.) Cut up the

onions and garlic and add them to the meat, continuing to cook over

medium heat until the onions are soft. Add in the chili powder,

thyme, salt, and pepper and sautee just a bit more, then pour

everything from the skillet into your pot of stock.

Throw in the spaghetti

sauce or tomatoes. (I only used spaghetti sauce because our

freeezer is nearly bare of tomato products. As I mentioned above,

you could instead use  about eight cups of stewed

tomatoes and add a bit more garlic and onion to the previous

step. I'm not sure if we could taste the basil.) Cook over

low heat for about an hour until the flavors meld together, or for two

hours if you started with stewed tomatoes and need them to lose some

liquid.

about eight cups of stewed

tomatoes and add a bit more garlic and onion to the previous

step. I'm not sure if we could taste the basil.) Cook over

low heat for about an hour until the flavors meld together, or for two

hours if you started with stewed tomatoes and need them to lose some

liquid.

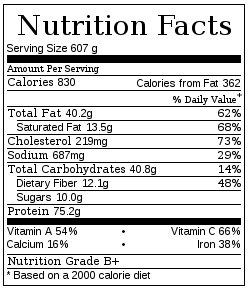

The USDA's nutritional

guidelines gives this chili a B+, probably because they don't like all

of the fat and cholesterol in the chicken stock and lamb.

However, we're believers in the nutritional

goodness of fats from pastured animals, so I'd give it an A.

Of course, the meal needs some greens on the side to round it off, and

cheddar on top of the chili makes it a treat.

It's been almost a year since

we

installed the Zereba K9 pet, lawn, and garden electric fence controller and we couldn't be happier with

the results.

First off I should say that

it only took Lucy about 10 minutes to learn when we first got chickens

that all poultry on the farm belonged to us and she was to never even

try to eat a chicken.

Food scraps in the new

pasture was another issue. She

kept being a bad girl, and I tried to plead with her

and build a better fence, but she was better at breaking in.

Food scraps in the new

pasture was another issue. She

kept being a bad girl, and I tried to plead with her

and build a better fence, but she was better at breaking in.

And then one day I saw the

Zereba K9 electric solution at a local hardware store and dared to

dream that this could send the clear message that I was unable to

articulate.

It only took her one shock to

realize any food scraps near the chickens were out of bounds. We moved

the flock to another pasture but did not need to install the K9 this

time as Lucy had clearly learned to keep a respectable distance.

Thinning

is like editing. The process is time-consuming and mentally

difficult, but if you bite the bullet and do the hard work, the fruits

of your labor are twice as good.

Thinning

is like editing. The process is time-consuming and mentally

difficult, but if you bite the bullet and do the hard work, the fruits

of your labor are twice as good.

Last year, I thinned

our peaches hesitantly,

leery of removing so many

baby fruits, but my work paid off in spades. In fact, as I picked

our huge, delicious peaches that summer, I only wished I'd thinned a

little harder since the peaches that had been left close together were

of much lower quality. And despite what you might think, the big

fruits had every bit as much flavor as you'll find in the tiny peaches

on abandoned trees that never get thinned. (I also feel obliged

to add my father's experience --- he didn't thin his peaches last year

and one tree bore so heavily that branches broke all the way off!)

So

this year, I thinned hard, removing about seven peaches for each one I

left behind. In addition to making sure the

fruits were separated by several inches along the branch, I tried to

select for large, unblemished fruits in sunnier spots. I could

tell that the oriental

fruit moth had

already laid its eggs, so I did my best to remove the infested

fruits. (No, I never did get around to implementing any control

strategies for this pest, so I'm sure I'll be scooping out wormy

centers this summer.) The tree will probably drop a few more of

fruits in a week or two, but last year I had no problem with pruning

pre-drop, and even this "hard" thinning job isn't as extreme as most

peach experts suggest.

So

this year, I thinned hard, removing about seven peaches for each one I

left behind. In addition to making sure the

fruits were separated by several inches along the branch, I tried to

select for large, unblemished fruits in sunnier spots. I could

tell that the oriental

fruit moth had

already laid its eggs, so I did my best to remove the infested

fruits. (No, I never did get around to implementing any control

strategies for this pest, so I'm sure I'll be scooping out wormy

centers this summer.) The tree will probably drop a few more of

fruits in a week or two, but last year I had no problem with pruning

pre-drop, and even this "hard" thinning job isn't as extreme as most

peach experts suggest.

Meanwhile, I went ahead

and snapped the tops off watersprouts popping

up in the center of the tree. Peach trees pruned to the open

center system will

keep putting up watersprouts every year, and if you

leave them alone, you'll be wasting a lot of your tree's energy that

could go into building useful branches instead of toward branches that

are just going to be lopped off. Meanwhile, the watersprouts

shade the fruits, negating the purpose of the open center system

(opening up as much of the fruit zone as possible to the sun.)

I'll try to remember to come back and do another round of summer

pruning later and to

remove any twigs that wilt (signs of further oriental fruit moth

damage.) But, mostly, I'll just sit back and watch the fuzzy

fruits swell outside the kitchen window.

The same wrong wheel for the lawn mower showed up

today in the mail.

I dove a bit deeper within

the schematic and discovered what they were calling a "rear wheel" was

actually the front wheel and a bit down the list we see that the rear

wheel is just called "wheel".

What impressed me was how

fast and efficient the lady at Sears parts direct was in first

listening to my explanation of the schematic error and then fixing the

problem. She even went the extra step of giving us 10% off for our

trouble plus free shipping.

The latest call took only 15

minutes, which combined with the first call equals a bit over half an

hour. That's too much time for a simple parts order, but these things

happen sometimes. Perhaps I'm the fist person ever to need the rear

wheel replaced on this particular model of push behind mower? Getting

to keep the 2 smaller front wheels is a small consolation, but maybe

they'll come in handy for something in the future.

Tomato planting day is one of

my favorite annual events, but it's also fraught with a lot of second

guessing. Last year, I had very good luck spacing my

tomatoes further apart (which meant setting out fewer of them ---

21 instead of 37) and pruning

them heavily, so

this year I'll be continuing that trend. I slipped 22 of the

heftiest transplants I've ever grown into the ground on Monday,

watering them in well to make up for the scorching heat.

Tomato planting day is one of

my favorite annual events, but it's also fraught with a lot of second

guessing. Last year, I had very good luck spacing my

tomatoes further apart (which meant setting out fewer of them ---

21 instead of 37) and pruning

them heavily, so

this year I'll be continuing that trend. I slipped 22 of the

heftiest transplants I've ever grown into the ground on Monday,

watering them in well to make up for the scorching heat.

Every

year, I grow fewer slicers and tommy-toes and more romas. In

2010, I was down to 8 non-romas, and this year I only put in 5, which

feels like very few until I remind myself that they only need to keep

us in fresh tomatoes over the summer. I had planned to put in 6

non-romas, but our delicious Japanese

Black Trifele seems to have carried blight spores in its seeds, so I

quickly culled all of the affected plants. That gave me space to

upgrade to 17 romas in hopes of socking away even more sauce, dried

tomatoes, and ketchup for the winter.

Every

year, I grow fewer slicers and tommy-toes and more romas. In

2010, I was down to 8 non-romas, and this year I only put in 5, which

feels like very few until I remind myself that they only need to keep

us in fresh tomatoes over the summer. I had planned to put in 6

non-romas, but our delicious Japanese

Black Trifele seems to have carried blight spores in its seeds, so I

quickly culled all of the affected plants. That gave me space to

upgrade to 17 romas in hopes of socking away even more sauce, dried

tomatoes, and ketchup for the winter.

I put most of our

tomatoes in one long, new bed running along the south side of the

chicken pasture. This is the very sunniest spot in the garden,

and I figure I can use the fence (with some extra posts) to train the

tomatoes upright and keep them drier than ever  before.

In our very wet climate, dry is what tomatoes crave, and we love them

enough to give them prime real estate in the garden. I had

actually hoped to make the bed a little longer, but two solid months of

wet, wet, wet has reduced me to scraping away at the last remnants of horse

manure compost, so

the new tomato bed ended rather abruptly when the manure gave

out. If nature smiles on us and we're able to drive the truck out

this week, I'll add another ten feet of tomato bed and throw in some

more roma seeds to increase our planting --- maybe this winter we'll

have enough dried tomatoes that they don't have to be a once a month

treat?

before.

In our very wet climate, dry is what tomatoes crave, and we love them

enough to give them prime real estate in the garden. I had

actually hoped to make the bed a little longer, but two solid months of

wet, wet, wet has reduced me to scraping away at the last remnants of horse

manure compost, so

the new tomato bed ended rather abruptly when the manure gave

out. If nature smiles on us and we're able to drive the truck out

this week, I'll add another ten feet of tomato bed and throw in some

more roma seeds to increase our planting --- maybe this winter we'll

have enough dried tomatoes that they don't have to be a once a month

treat?

One of my favorite

spring/summer sounds is the swoosh swooshing of our 220

volt creek pump pushing water all the way up to our thirsty

garden.

Although I seem to save my

obsessing for the tomatoes, I didn't want you to think

that's all we put in the garden this week. Our first round of

sweet potato slips were ready to set out early, thanks to the gravel

starting flat that

tempted shoots to grow roots before I even snipped them from the parent

tuber. And I started peppers inside this year to give us a bit of

a head start on the growing season.

Although I seem to save my

obsessing for the tomatoes, I didn't want you to think

that's all we put in the garden this week. Our first round of

sweet potato slips were ready to set out early, thanks to the gravel

starting flat that

tempted shoots to grow roots before I even snipped them from the parent

tuber. And I started peppers inside this year to give us a bit of

a head start on the growing season.

Most of our summer crops

grow from seed, though. I put in a second planting of sweet corn,

green beans, summer squash, and watermelons since the late April

seedlings are already up and thriving, and I would have put in another

set of cucumbers if I hadn't run out of seeds. (More are on the

way.) Peanuts will go in later this week, as will the first round

of butternuts.

Then, in two weeks,

it'll be time to plant many of these crops all over again. Succession

planting keeps our

summer harvest steady for crops like sweet corn that ripen up all at

once  and for troublesome cucurbits

(squash, cucumbers) and beans that tend to peter out from pests or

disease after a few weeks of bearing. Midsummer planting is also

appropriate for winter squashes that will sit on the shelf through the

cold season --- the later the squashes ripen up, the more likely they

are to still be good come spring. So June is the time to plant

most of my butternuts as well as the naked seed pumpkins we're trying

out this year.

and for troublesome cucurbits

(squash, cucumbers) and beans that tend to peter out from pests or

disease after a few weeks of bearing. Midsummer planting is also

appropriate for winter squashes that will sit on the shelf through the

cold season --- the later the squashes ripen up, the more likely they

are to still be good come spring. So June is the time to plant

most of my butternuts as well as the naked seed pumpkins we're trying

out this year.

And then, just one month

from now, it'll be time to start putting in the fall garden! I'm

glad I keep all of this information in a spreadsheet because I'd never

get the planting dates right otherwise.

The

pump in our creek sucks

up tiny particles that eventually clog up the stainless steel filter on

our reciprocating lawn sprinklers.

We started experimenting with

deleting the filters last year. The initial concern was that the

sprinkler head might get gunked up and stop working. That hasn't

happened yet, even with the junkier plastic version.

I have a feeling this

modification wouldn't work on a system with lower pressure, but it

might be worth a try. The replacement cost for these things is less

than 10 dollars, but the feeling of security one gets knowing you can

water the garden during a dry spell is priceless.

Forest gardening books

sing the praises of alpine strawberries, promising stunning flavor in a

shade-tolerant plant that bears all summer, but my experience hasn't

been as positive. I started

some alpine strawberries from seed last year and transplanted

them into a slightly shady raised bed below my ailing dwarf

cherry. The strawberries produced that same summer, but the

fruits were a bit mealy and lacked the complex flavor that I'm used to

in my homegrown strawberries.

I figured the dull flavor

could be an artifact of the time of year, so left the alpine

strawberries in place, planning a side by side comparison this

spring. But when our first strawberries ripened up, Mark and I

both decided that the alpines didn't hold a candle to our favorite

Honeoyes.

I figured the dull flavor

could be an artifact of the time of year, so left the alpine

strawberries in place, planning a side by side comparison this

spring. But when our first strawberries ripened up, Mark and I

both decided that the alpines didn't hold a candle to our favorite

Honeoyes.

The alpines did win very

slightly on one point, though --- earliness. We ate our first

alpine strawberries on May 7 and didn't get our first June-bearing

strawberriers until May 9. Those two early fruits aren't going to

be enough to turn alpine strawberries into a core crop on our farm,

though.

That said, I wonder if

the problem with our alpine strawberries could stem from my method of

starting them from seed. Nearly all fruits are cloned rather than

grown from seed since the genetic diversity in a batch of seeds will

result in a bunch of duds and only a few winning plants. Granted,

books tell me that it's fine to start alpine strawberries from seed,

but I'm not so sure. Has anyone eaten really award-winning alpine

strawberries? Do you know what variety they were and how they

were started?

One problem I've always seen

with these window air conditioners was the limited choices a house or

trailer might have when looking for an appropriate installation spot.

I've had several of these

through the years and I often found myself standing in front of it so I

could receive the full effect of the chilled air thinking it sure would

be nice to have this artificial cool breeze blowing on me over there in

that chair.

It took Anna and me a little

over 2 hours to make the above custom fit. Now I can sit within inches

of the Arctic winter blast.

Greens

aren't very sexy, so I don't talk about them much. But if you

considered the vegetable side of our diet, I'll bet cooked greens would

make up a quarter of the pie, so I figured it was worth trying out a

few new varieties this year. (As a side note, what I call

"greens" are often referred to in the literature as potherbs. I'm

talking about vegetables we grow to eat as cooked leaves.)

Greens

aren't very sexy, so I don't talk about them much. But if you

considered the vegetable side of our diet, I'll bet cooked greens would

make up a quarter of the pie, so I figured it was worth trying out a

few new varieties this year. (As a side note, what I call

"greens" are often referred to in the literature as potherbs. I'm

talking about vegetables we grow to eat as cooked leaves.)

Before I launch into

what I thought of the newcomers to the garden, I

should probably tell you what our old standbys are. The summer

garden is Swiss chard all the

way --- this is the only green that doesn't bolt and the plant's mild

flavor doesn't need the sweetening effects of frost. Most of the

other greens are in the crucifer family with broccoli and  cabbages,

but swiss chard is just about alone (except for spinach, beets, and

amaranth), so garden rotations are a bit easier with swiss chard in the

mix. To top it all off, this summer green isn't bothered by cabbage worms or flea

beetles, although

last year we did get an infestation of striped blister beetles.

cabbages,

but swiss chard is just about alone (except for spinach, beets, and

amaranth), so garden rotations are a bit easier with swiss chard in the

mix. To top it all off, this summer green isn't bothered by cabbage worms or flea

beetles, although

last year we did get an infestation of striped blister beetles.

Our favorite fall and

winter green is kale.

After a frost, kale becomes so sweet that we eat it like candy, and the

plant is also our most cold hardy green, sometimes managing to

overwinter without protection in zone 6. That said, I usually

hedge my bets in the fall by also planting mustard.

The flavor of mustard isn't anything to write home about, but the

plants

love our weather and grow like crazy when nothing else will.

And mustard is a local staple, so you can get the seeds cheap at the

feed

store.

Everyone seemed to be

singing the praises of Asian

greens

last year, though, so I thought I'd better jump on the bandwagon.

On the recommendation of one of Elliot

Coleman's books, I

planted tokyo

bekana and kyona mizuna in early March hoping that these would turn

into good additions to our summer garden. The kyona mizuna is a

bit of a wash --- the leaves are thick and not very tasty, in my

opinion, and the flea beetles love them. On the other hand, Mark

and I both adore the flavor of the tokyo bekana (although the flea

beetles do too.) But I'm a bit disappointed to see that both of

these Asian greens are already starting to bolt (especially the kyona

mizuna) --- I guess they won't

be summer greens after all.

Meanwhile, I sprinkled chicory

(aka Italian Dandelion) seeds on expansions

of various tree mounds

in

the forest garden. The goal was to come up with a cultivated

perennnial green that likes partial shade and will give us tasty

dinners early in spring when annuals aren't growing. I couldn't

find any chicory specifically labelled as a perennial so this

experiment

may fail in the long run, but in the short run I'm thrilled with the

results. The Catalogna Special Italian Dandelion I planted in

early March was big enough for frequent small cuttings starting at

about

six weeks old and I've found that adding 10% chicory to a pot of other

greens adds complexity to the dish's flavor. (In earlier spring,

the leaves should be less bitter and edible on their own.)

Meanwhile, I sprinkled chicory

(aka Italian Dandelion) seeds on expansions

of various tree mounds

in

the forest garden. The goal was to come up with a cultivated

perennnial green that likes partial shade and will give us tasty

dinners early in spring when annuals aren't growing. I couldn't

find any chicory specifically labelled as a perennial so this

experiment

may fail in the long run, but in the short run I'm thrilled with the

results. The Catalogna Special Italian Dandelion I planted in

early March was big enough for frequent small cuttings starting at

about

six weeks old and I've found that adding 10% chicory to a pot of other

greens adds complexity to the dish's flavor. (In earlier spring,

the leaves should be less bitter and edible on their own.)

Coming up next in 2011's

great greens trial are a variety of amaranth

grown for summer greens and tatsoi (another Asian green) in the

fall. I also plan to experiment with several new varieties of

kale to see if I can find one that's even tastier (inconceivable!) and

more winter hardy. I'd be curious to hear which greens are your

standbys and

why.

The final chapter in my

little lawn mower saga is

a happy one.

A new and improved rear wheel

showed up in the mail. What makes this one special is the addition of 2

all metal bearings.

Makes me wonder if the

original designers planned it this way by making the original wheel

without any bearings so they could squeeze another 30 bucks out of the

customer when the plastic gives out from a few years of service?

After

letting the plants take up space in our garden for four years, I've

finally found a use for chives. Let me back up, though, and tell

you about our new favorite greens "recipe." I put

"recipe" in quotes because something this simple doesn't really seem

like cooking, but the taste is surprisingly complex:

After

letting the plants take up space in our garden for four years, I've

finally found a use for chives. Let me back up, though, and tell

you about our new favorite greens "recipe." I put

"recipe" in quotes because something this simple doesn't really seem

like cooking, but the taste is surprisingly complex:

- About three quarts of loosely packed leafy greens

- About a pint of chicory leaves

- About half a cup of Egyptian onion leaves

- A healthy dash of balsamic vinegar

- A slightly less healthy dash of peanut oil

Turn

the heat on high and stir until the leaves are just barely cooked (a

few scant minutes.) The greens cook down to make just enough to

serve two. Not elegant but definitely delicious!

Turn

the heat on high and stir until the leaves are just barely cooked (a

few scant minutes.) The greens cook down to make just enough to

serve two. Not elegant but definitely delicious!

Now, back to those

chives. Egyptian onions make an appearance on our plates daily

for much of the year, but at the beginning of May, the plants begin to

put up their fruiting stalks. At that point, the onion leaves

turn thicker and lose a lot of their prime flavor, so I needed to find

a replacement for my most-used herb. That's when I remembered

that normal people cook with chives the way I cook with Egyptian

onions, and  sure enough, chives made a

pretty good substitute in the recipe above. Chive leaves seem to

lose their flavor less when they're in bloom, even though I think the

leaves don't taste as good as Egyptian onion leaves during the rest of

the year.

sure enough, chives made a

pretty good substitute in the recipe above. Chive leaves seem to

lose their flavor less when they're in bloom, even though I think the

leaves don't taste as good as Egyptian onion leaves during the rest of

the year.

In case you're wondering

why I weeded and mulched chives for so long without eating them, the

answer is --- pollinators! Our halictid

bees, especially,

adore the flowers of chives, and I've seen several other pollinators

visiting from time to time. And, yes, they're pretty.

When I was a kid I saw an

episode of Gilligan's island where some radioactive seeds washed ashore

and they grew extra large vegetables as a result. The carrots provided

super enhanced vision and the spinach gave the Skipper super strong

muscles.

Parts of this concept might not be as

crazy as it sounds. In 1999 a robot was sent into the Chernobyl reactor

to map the building and found a black

fungus that was somehow thriving in the toxic environment. Some speculation suggests that

the fungi have an unknown mechanism that can use the energy radiated for growth.

Image credit goes to

vintage-ads.livejournal.com via a post from the Boing Boing blog and

the blue mushroom image is thanks to layoutsparks.com.

I'm nervously gearing up for

hatch #2. The Brinsea

Octagon 20 Advance Incubator seems to have done its job perfectly,

never letting the interior temperature vary by more than 0.2 degrees

Fahrenheit, and I got the eggs

to lose just the right amount of weight. I'm expecting a very

high hatch rate...as long as I don't mess up these last two days.

I'm nervously gearing up for

hatch #2. The Brinsea

Octagon 20 Advance Incubator seems to have done its job perfectly,

never letting the interior temperature vary by more than 0.2 degrees

Fahrenheit, and I got the eggs

to lose just the right amount of weight. I'm expecting a very

high hatch rate...as long as I don't mess up these last two days.

Having unplugged the egg

turner and raised the humidity up for hatch, the only remaining problem

I foresee is the chicks killing each other. You may recall that

one of our chicks accidentally

speared another in the gut during the

last hatch, and I'm

concerned that the cramped conditions inside our current incubator

might create a repeat of that disaster. I moved five eggs to the Brinsea

Mini Advance incubator

Saturday afternoon so that I had space to lay all of the eggs down flat

in the bigger incubator, but even that could be a two-edged sword ---

the littler incubator might let the temperature vary more for the last

two days, but hopefully the mostly developed chicks can deal with a bit

of variation.

What I'm trying to

decide now is whether to move yet more eggs out of the big incubator

and into our faulty Little

Giant incubator once

they begin to pip. I'm far from confident about my ability to

control the temperature in there, but the extra space might be worth

sub-optimal temperature for the last day, and during my trial on

Saturday afternoon, temperatures stayed pretty steady in the styrofoam

incubator. Alternatively, I could wait until chicks hatch and

then carefully transfer them to the Little Giant for the dry-down

period, or I could just leave that incubator out of the mix

entirely. I'd love some advice from the hatchers among you.

Does more space trump better temperature control? Would you put

some eggs in the Little Giant or leave them all in the Brinsea

workhorse? (Am I crazy to think we might get 21 live chicks out

of our 24 eggs?)

This hose splitter with

control valves is metal with a plastic coating. It cost a couple bucks

more than the all metal or all plastic, but it's money well spent if

you need to leave this stuff outside all season long.

Maybe I should build a cover for it to provide some shade and reduce the UV exposure

to help it last even longer?

This butternut seedling is

growing on the compost pile...along with a few dozen of his brothers

and cousins. Whenever I walk by, I can't help but think about the

anthropological hypothesis that agriculture may have begun when seeds

like this sprouted out of early man's midden heaps.

This butternut seedling is

growing on the compost pile...along with a few dozen of his brothers

and cousins. Whenever I walk by, I can't help but think about the

anthropological hypothesis that agriculture may have begun when seeds

like this sprouted out of early man's midden heaps.

If you pay attention,

you'll notice that some vegetables can put up with compost piles while

others can't. At first, compost life sounds like living on easy

street, but the conditions are actually a bit rough. Sure,

there's plenty of extra fertility, but my volunteer butternuts have had

to put up with undiluted

urine baths a couple

of times a week, with lots of high carbon materials to grow around, and

with shifting soil as the compost pile settles. Despite these

potential problems, volunteer tomatoes and squashes seem to prefer the

compost heap to the garden.

When you create

a kill mulch and

plant into it right away rather than letting the no-till garden mellow

for a season before planting, you're growing in soil a lot like your

compost pile. That's why I save crops that make good compost pile

volunteers for our new no-till beds each summer, and give less hearty

garden crops the older beds. Now I just have to decide whether to

let thirty butternut plants sprawl out across the forest pasture or to

turn the compost pile and crush these volunteers.

Our third homegrown

chick showed up today a bit earlier than predicted.

Not sure when we'll get

accustomed to all this eggcitement during the hatching phase.

In my opinion it's 10 times

more entertaining than any television I can remember.

I

still don't know how successful this

hatch will be, but fifteen hours into day 21, there are now two fully

fluffed chicks in the brooder, one wet chick flopping its

way out of the shell, and five more pipping. I've got a lot of

thoughts on the process so far:

I

still don't know how successful this

hatch will be, but fifteen hours into day 21, there are now two fully

fluffed chicks in the brooder, one wet chick flopping its

way out of the shell, and five more pipping. I've got a lot of

thoughts on the process so far:

- All of this activity has taken place in one half of the

incubator, making me wonder if temperatures aren't exactly the same

throughout. Perhaps next time I should flip the orientation of

the egg tray each time I weigh

it?

- Or maybe hatch time varies by breed? All of the fully

hatched chicks are my mail-ordered cuckoo maran eggs, and so are a

couple of the pippers.

- Humidity isn't so hard to deal with during hatch as people make it seem. Adding a wet washcloth to the bottom of the incubator under the wells and pouring in a bit of baby bottle temperature water whenever I mess around inside lets me keep humidity in the incubator quite high with the vent partly open, and the humidity rebounds in minutes when I have to open the lid.

- I was overreacting about space

in the incubator. All of the chicks who have hatched so far

have been brimming with life, not soft and easily damaged like the ones

that died in the incubator last time. Since the chicks hatch over

quite a long time period, I can take out dried off chicks and empty

shells at intervals, leaving more space for each newly hatched bird.

That said, I still had

nightmares and woke up three times during night 20, coming in with a

flashlight to check on the eggs. In an effort to ease my mind and

get a full night's sleep for night 21, I downloaded three free ebooks

about incubation, the most useful of which has been Incubation: Natural and Artificial

by J.H. Sutcliffe. Yes, this book is over a century old, but I

was looking for tried and true information. I learned that my gut

feeling that I should turn any pipped eggs upright if their hole is

pointing to the floor instead of the ceiling is right on track and that

you can tell if an unpipped egg is alive on day 21 by using the witch

test (you know, put it in some warm water and see if it floats.) I'll save that last

tidbit of information for an emergency.

That said, I still had

nightmares and woke up three times during night 20, coming in with a

flashlight to check on the eggs. In an effort to ease my mind and

get a full night's sleep for night 21, I downloaded three free ebooks

about incubation, the most useful of which has been Incubation: Natural and Artificial

by J.H. Sutcliffe. Yes, this book is over a century old, but I

was looking for tried and true information. I learned that my gut

feeling that I should turn any pipped eggs upright if their hole is

pointing to the floor instead of the ceiling is right on track and that

you can tell if an unpipped egg is alive on day 21 by using the witch

test (you know, put it in some warm water and see if it floats.) I'll save that last

tidbit of information for an emergency.

Photos this morning

aren't very inspired since it's not quite daylight and my photographer

(Mark) is still sound asleep. I'm sure you'll see more cute

pictures tonight.

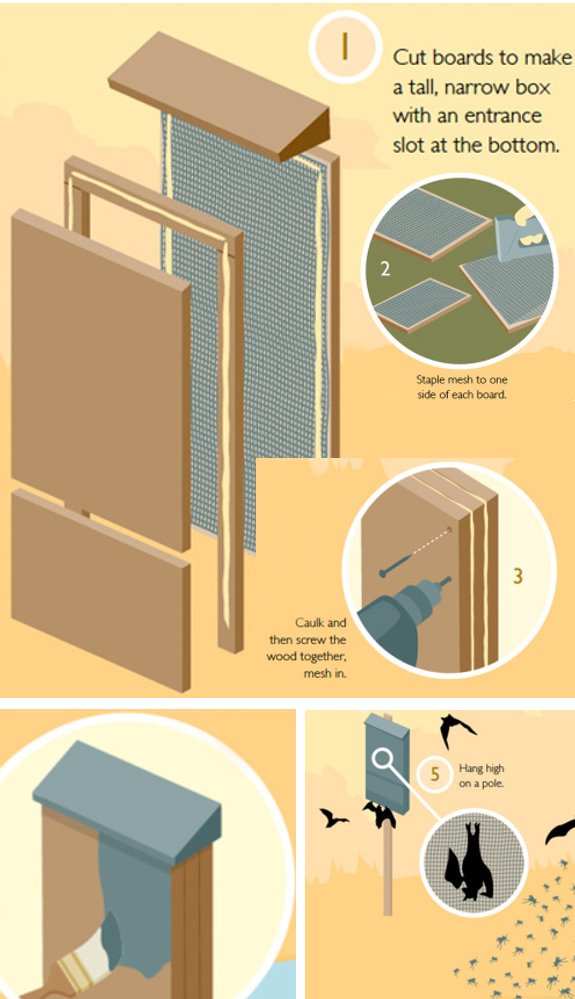

In your agrarian situation, do bats have a place in your plans?

Vester

That question brings up a

project that's been on the back burner for a while now.

I'm thinking the shady side

of our barn would be a good place to mount a few bat boxs and maybe a

bed of straw at the bottom to catch any potential guano.

Image credit goes to Lauren

Smith and Derek Fagerstrom from their intriguing book titled "More Show

Me How".

All of the books and websites

agree that you get your best chicks by the end of day 21, so even

though I'll let the rest of the eggs sit in the incubator for another

day or two, I want to do my hatching analysis with just the chicks

hatched by Tuesday afternoon. At that time, there were five happy

chicks snuggled under the brooder, two aided and ailing chicks

in the first aid incubator (more on them tomorrow), one chick just

hatched in the big incubator, and two pipped eggs.

All of the books and websites

agree that you get your best chicks by the end of day 21, so even

though I'll let the rest of the eggs sit in the incubator for another

day or two, I want to do my hatching analysis with just the chicks

hatched by Tuesday afternoon. At that time, there were five happy

chicks snuggled under the brooder, two aided and ailing chicks

in the first aid incubator (more on them tomorrow), one chick just

hatched in the big incubator, and two pipped eggs.

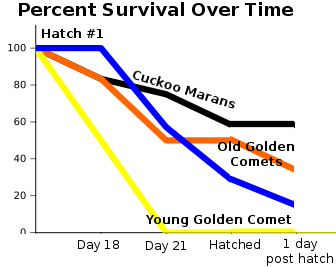

Of the six chicks that

hatched on their own, five were Cuckoo Marans and only one was a

homegrown egg. Keep in mind that the Cuckoo Marans were jiggled

around by the post office and had to wait a whole week from laying

before going in the incubator, a combination of factors that often

reduces hatch rates. So why did they do so much better?

Nine of the 24 eggs I started

with were from our four year old hens because I was hoping to pass on

their foraging genes, but I've since read that any hen older than two

years is going to produce eggs with limited viability. Even the

eggs from our "young" Golden Comet are a bit suspect since she's three

years old. Of these geriatric eggs, one hatched unaided just at

the end of day 21, I helped one out, and one is a late pipper.

For the sake of comparison, our mail order Cuckoo Marans self-hatched

42% of their eggs by the end of day 21, I helped one chick out of the

shell, and one more is a late pipper. Clearly, age of the hen

matters.

Nine of the 24 eggs I started

with were from our four year old hens because I was hoping to pass on

their foraging genes, but I've since read that any hen older than two

years is going to produce eggs with limited viability. Even the

eggs from our "young" Golden Comet are a bit suspect since she's three

years old. Of these geriatric eggs, one hatched unaided just at

the end of day 21, I helped one out, and one is a late pipper.

For the sake of comparison, our mail order Cuckoo Marans self-hatched

42% of their eggs by the end of day 21, I helped one chick out of the

shell, and one more is a late pipper. Clearly, age of the hen

matters.

As a side note, next

time I'll be sure to plan my hatch for the weekend. My ability to

focus on work while chicks are struggling out of their shells over my

right shoulder is pretty much nill. Good thing my boss is nice!

Its now been a month since

the new

poultry ramp went in and

both generations of the flock seem to be fine with getting in and out.

Home grown 2.0 is about 2 days older than the

rest of the next generation which naturally makes him their leader.

Is

it worth it to help chicks who are having trouble getting out of the

shell? For that matter, how can you tell if they're having

trouble? If you do help, how? I'm far from an expert, but

after our second hatch, I'm starting to feel like I have a handle on

the answers to these thorny questions, so I thought I'd share.

Is

it worth it to help chicks who are having trouble getting out of the

shell? For that matter, how can you tell if they're having

trouble? If you do help, how? I'm far from an expert, but

after our second hatch, I'm starting to feel like I have a handle on

the answers to these thorny questions, so I thought I'd share.

First of all, the course

of least resistance is to not help, which is what I did with our first

hatch. If you're okay with some good chicks dying in the

incubator, this route makes sense, but you can improve your hatch rate

by giving troubled chicks a hand. That said, I wouldn't recommend

helping unless:

- You have some sort of critical care unit prepared (like a spare incubator, all warmed up.) Chicks you help out of the shell are likely to be weak and will need some extra time in a warm spot where they won't be picked on. Otherwise, your more vibrant chicks might peck them to death.

- You have a way of boosting the humidity in the incubator. Helping means opening the lid more, which can harm your currently hatching chicks. I devised an easy method of increasing the incubator humidity so that the chicks barely noticed me lifting the lid.

- You're willing to cull chicks.

The process of escaping the shell naturally kills chicks that are

damaged or are too weak to make it in life. By helping chicks out

of the shell, you're taking responsibility for euthanizing the ones

that survive but are too damaged to live in your flock. One of

the three chicks we helped had a problematic leg (not splayed legs, but

worse) that meant it would never be able to walk, and we had to put it

out of its misery. We figured out how to cull

chicks so that they die in seconds (but I'm putting the information

behind a link since I know the image will bother some of you.)

If you aren't scared into

letting nature take its course, let's move on to when to help

chicks. In most cases, an untroubled chick will pip (peck a hole

in its shell) and then spend some time thinking about its

options. After anywhere from a few minutes to a few hours, the

chick starts hitting its beak against the shell in earnest to unzip

itself, a process that usually only takes an hour or so once

started. You can tell the chick is having trouble if it gets

stuck for several hours in the unzipping stage, either futilely banging

its beak against the hole without making further openings in the shell

or mostly unzipped but unable to kick free. A chick is also

troubled if it's pipped but hasn't started unzipping after twelve

hours, or if the bit of exposed membrane around the pipping hole is

starting to turn tan and dry. Finally, if a chick somehow

maneuvers itself so that it's trying to pip at the pointed end of the

shell, it won't be able to get out, so you might as well help from the

beginning.

If you aren't scared into

letting nature take its course, let's move on to when to help

chicks. In most cases, an untroubled chick will pip (peck a hole

in its shell) and then spend some time thinking about its

options. After anywhere from a few minutes to a few hours, the

chick starts hitting its beak against the shell in earnest to unzip

itself, a process that usually only takes an hour or so once

started. You can tell the chick is having trouble if it gets

stuck for several hours in the unzipping stage, either futilely banging

its beak against the hole without making further openings in the shell

or mostly unzipped but unable to kick free. A chick is also

troubled if it's pipped but hasn't started unzipping after twelve

hours, or if the bit of exposed membrane around the pipping hole is

starting to turn tan and dry. Finally, if a chick somehow

maneuvers itself so that it's trying to pip at the pointed end of the

shell, it won't be able to get out, so you might as well help from the

beginning.

If you have a stuck

chick, how can you help? You'll need a basin of warm water (baby

bottle temperature), a clean rag, and nimble fingers. First step

is to moisten the membranes since they've probably started to dry out

if the chick has been pipped for so long. Dampen the rag in the

warm water and encircle the egg, then squeeze a few drops of water onto

the exposed membrane around the pipping hole. Be careful not to

drown the chick, though, since its beak will be right there --- you

don't want any water to actually run into the egg, just hydrate the

membrane. Since the chick has already started a hole, it should

be pretty simple to gently pick off bits of shell and membrane, opening

up a line around the shell just like the chick would have. If

your chick is worth saving, once you get the shell separated into two

halves, it will kick its way out, which is important for development of

the chick's legs. The membrane shouldn't bleed --- if it does,

the chick isn't really quite ready to hatch, so pop it back in the

incubator. (All of this is done in a warm spot outside the

incubator, by the way. You plucked out the problematic egg and

quickly reclosed the lid to keep everyone else toasty and moist.)

I

helped three chicks during our most recent hatch, and all three of them

would have survived if I hadn't decided to cull the chick with the

troubled leg. I'm about 95% sure all three of these chicks would

have died if I hadn't helped, so I figure the time was well

spent. Plus, I didn't have dead chicks stinking up the incubator

like I did last time around, so I was able to let it keep running clear

to the end of day 22, netting one late hatcher halfway through the last

day. I'll definitely help any ailing chicks next time.

I

helped three chicks during our most recent hatch, and all three of them

would have survived if I hadn't decided to cull the chick with the

troubled leg. I'm about 95% sure all three of these chicks would

have died if I hadn't helped, so I figure the time was well

spent. Plus, I didn't have dead chicks stinking up the incubator

like I did last time around, so I was able to let it keep running clear

to the end of day 22, netting one late hatcher halfway through the last

day. I'll definitely help any ailing chicks next time.

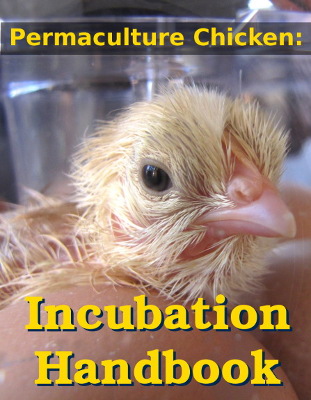

Since writing this post, I've perfected my

technique of helping chicks without bothering their siblings.

I've also got a better handle on when it's a good idea to help, and

when those chicks will have to be culled. Learn more about

helping chicks out of the shell in my 99 cent ebook.

Since writing this post, I've perfected my

technique of helping chicks without bothering their siblings.

I've also got a better handle on when it's a good idea to help, and

when those chicks will have to be culled. Learn more about

helping chicks out of the shell in my 99 cent ebook.

Permaculture

Chicken: Incubation Handbook walks beginners through perfecting the

incubating and hatching process

so they can enjoy the exhilaration of the hatch without the angst of

dead chicks. 92 full color photos bring incubation to life, while

charts, diagrams, and tables provide the hard data you need to

accomplish a hatch rate of 85% or more.

We've had the new Kobalt

never flat wheel barrow

in service for a few months now and it still feels like the best wheel

barrow money can buy.

We've had the new Kobalt

never flat wheel barrow

in service for a few months now and it still feels like the best wheel

barrow money can buy.

What would be great is if

someone would come up with a never flat wheel upgrade for the size of

wheels on the TC1840H

garden wagon.

I love strawberries, but have

always been a bit undecided about strawberry shortcake. For one

thing, there just aren't enough strawberries in the dish. And

where's the chocolate? With strawberry season in full swing, I

tested out a new recipe that won everyone's heart...including my own.

Start with a big bowl of strawberries. A

gallon of strawberries will serve about seven or eight strawberry

lovers. Try not to eat too many on the way into the house.

If you must, wash the

strawberries, but only if it's been raining and the fruit is really

dirty. Then cut off the stems and slice the berries into

slivers. Sprinkle on a bit of sugar (perhaps 0.25 cups at the

most) --- you shouldn't need much, but if you couldn't wait to pick the

berries on a sunny afternoon, a bit of sugar will bring out the

flavor. Stir up the berries and set them aside. You should

have just over two quarts of lightly sweetened strawberry slices.

Now make the

brownies...I mean, shortcake. Preheat the oven to 350 degrees

Fahrenheit and butter a 9 by 13 inch pan. Melt a stick of butter

and stir in 1 cup of sugar, 2 eggs, 1.25 cups of cocoa (we used

Hershey's Special Dark because it was on sale), 0.25 c. flour, 0.5

teaspoons salt, 0.5 teaspoons baking powder, 1.5 teaspoons vanilla, and

about 2 tablespoons of water  (enough to make the dough

hang togeher.) Whir up one 3.52 ounce bar of 60% dark chocolate

(we used Hershey's Extra Dark) in the food processor to turn it into

chips. Stir the chips into the dough and spread the result into

the bottom of the pan --- it won't want to spread and will be a bit

thin. Bake until a butter knife barely comes out clean.

(enough to make the dough

hang togeher.) Whir up one 3.52 ounce bar of 60% dark chocolate

(we used Hershey's Extra Dark) in the food processor to turn it into

chips. Stir the chips into the dough and spread the result into

the bottom of the pan --- it won't want to spread and will be a bit

thin. Bake until a butter knife barely comes out clean.

Now, pour a pint of

whipping cream in a bowl and turn your mixer on high to whip it.

At the end, sprinkle in a bit of sugar (perhaps 3 or 4 tablespoons) and

mix just enough to blend.

Finally,

assemble your dessert. Brownies on the bottom, then strawberries

(being sure to pour on some of the juices), and finally whipped

cream. This recipe is too rich to eat every day, but is