archives for 03/2011

The perennials are

waking up much earlier than usual this year. New plantain leaves

are pushing their way up through the muck where we wear the "lawn" down

to bare soil in front of the door every winter, and the Egyptian onions

have been sending up scads of new leaves for a couple of weeks

now. I even saw a speedwell flower Sunday, but wasn't quick

enough to capture its smiling face before a deluge washed everything

away.

As

heartening as these signs of spring are, though, I feel compelled to

ask the weather to slow down! You see, the same

warmth that wakes up the onions is also tempting my fruit trees and

vines to burst open their flowers far too soon. I can already see

green in the swollen pear and kiwi buds, which means those buds are at high

risk of being frostbitten when the inevitable cold

swings of March return. Luckily, my peaches (the only fruit trees

old enough to bear fruit this year) still have tightly coiled buds, and

I'm sending them soporific thoughts. Please, don't open until

April!

As

heartening as these signs of spring are, though, I feel compelled to

ask the weather to slow down! You see, the same

warmth that wakes up the onions is also tempting my fruit trees and

vines to burst open their flowers far too soon. I can already see

green in the swollen pear and kiwi buds, which means those buds are at high

risk of being frostbitten when the inevitable cold

swings of March return. Luckily, my peaches (the only fruit trees

old enough to bear fruit this year) still have tightly coiled buds, and

I'm sending them soporific thoughts. Please, don't open until

April!

As I've explained previously,

black

soldier flies are primarily grown to provide high quality animal feed, although they can also be

considered a way to get rid of food scraps. The larvae are

voracious feeders that can consume huge amounts of high nitrogen waste

without any input of high carbon components. Since you don't have

to add bedding, the bins can be much

smaller than a worm bin while consuming the same amount of food

waste. Even better, the larvae self-harvest, crawling right into

a collection bucket so that you can feed them to your chickens,

lizards, fish, or other critters.

As I've explained previously,

black

soldier flies are primarily grown to provide high quality animal feed, although they can also be

considered a way to get rid of food scraps. The larvae are

voracious feeders that can consume huge amounts of high nitrogen waste

without any input of high carbon components. Since you don't have

to add bedding, the bins can be much

smaller than a worm bin while consuming the same amount of food

waste. Even better, the larvae self-harvest, crawling right into

a collection bucket so that you can feed them to your chickens,

lizards, fish, or other critters.

If you add 100 pounds of

food waste to your black soldier fly bin, you should end up with 20

pounds of prepupae (large larvae, ready to change into adults.) A

nutritional analysis of dried black soldier fly prepupae consists of:

- 42.1% crude protein

- 34.8% ether extract (lipids)

- 7.0% crude fiber

- 7.9% moisture

- 1.4% nitrogen free extract (NFE)

- 14.6% ash

- 5.0% calcium

- 1.5% phosphorus

Take a look at your bag of

chicken laying pellets, and you'll probably notice some

similarities. If you fed your chickens a quarter of their daily

rations in the form of black soldier flies, you could take care of most

of their protein and calcium needs, then round out their diet with

cheap components like greens and grains. In addition to saving

money, folks growing black soldier flies for their chickens report that

the feed makes their hens' eggs brilliantly orange, a sign of high

nutrition.

Take a look at your bag of

chicken laying pellets, and you'll probably notice some

similarities. If you fed your chickens a quarter of their daily

rations in the form of black soldier flies, you could take care of most

of their protein and calcium needs, then round out their diet with

cheap components like greens and grains. In addition to saving

money, folks growing black soldier flies for their chickens report that

the feed makes their hens' eggs brilliantly orange, a sign of high

nutrition.

Larvae are the primary

output of the black soldier fly bin, but you do get a bit of compost

--- about 5 pounds for every 100 pounds of food waste you put in the

bin. This small amount of compost can be good for city-dwellers

who don't have room to use up a lot of compost anyway and who would be

thrilled not to have to clean out their food composter for months at a

time. On the other hand, if you're primarily composting your food

scraps to add fertility to the garden, black soldier flies probably

aren't the way to go.

The other disadvantage

of black soldier flies compared to worm bins or compost piles is that

black soldier fly bins are relatively high maintenance. Since you

don't add high carbon bedding to absorb odors, you have to pay

attention and only add as much food to your bin as your larvae will eat

in a day. However, if you're running a diversified homestead and

have a bunch of chickens, that bit of time is probably worth it for the

high quality feed you get in exchange. I think that compost

piles, worm bins, and black soldier fly bins will all find a niche on

our farm.

| This post is part of our Black Soldier Fly lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The storm that took down our big pine tree still has us flooded in.

I recently discovered this

semi-convenient tree crossing, which is in a smaller creek that connects

to our creek about a half mile down.

It's a handy detour that may

or may not be there after the next visit from a storm.

I put our pot

of peas on top of

the fridge, figuring that was the warmest spot inside during this

shoulder season when we're only running the wood stove now and

then. Just over a week later, the pea sprouts are up and growing

fast! I figure we'll be able to snip off tendrils to munch on

starting next week.

Meanwhile, out

in the quick hoop,

the lettuce bed has greened right up. I anticipate our first

spring salad by the middle of March.

Meanwhile, out

in the quick hoop,

the lettuce bed has greened right up. I anticipate our first

spring salad by the middle of March.

(See that grass in the

background? That's the barley cover crop that didn't winter

kill. I'm going to have to figure out how to make it bite the

dust before I plant the March bed of lettuce.)

Rounding out my March baby

photos, the

onions I started indoors are so tall I'm starting to

wonder if they need to be repotted. This is the trouble with

starting seeds inside --- they look so cute and low-work when you drop

72 seeds in a flat, but what do you do a few weeks later when they need

more elbow room? I detest the endless round of potting up (and

the neighboring task of finding room for all of those larger and larger

pots), so I may choose to transplant these guys into the onion quick

hoop I plan to build next week. For those of you who start your

onions indoors from seed, how soon do you put your onions out in a cold

frame or straight in the garden?

Rounding out my March baby

photos, the

onions I started indoors are so tall I'm starting to

wonder if they need to be repotted. This is the trouble with

starting seeds inside --- they look so cute and low-work when you drop

72 seeds in a flat, but what do you do a few weeks later when they need

more elbow room? I detest the endless round of potting up (and

the neighboring task of finding room for all of those larger and larger

pots), so I may choose to transplant these guys into the onion quick

hoop I plan to build next week. For those of you who start your

onions indoors from seed, how soon do you put your onions out in a cold

frame or straight in the garden?

I've

dragged my feet about starting black soldier flies because the bins are

relatively complicated, but after a bit of internet research, building

our own is starting to feel feasible. It sounds like a successful

black

soldier fly bin will have good drainage at the bottom, air holes at the

top to let in adults wanting to lay their eggs, and a ramp for the

larvae to crawl up and out into the collection bucket.

I've

dragged my feet about starting black soldier flies because the bins are

relatively complicated, but after a bit of internet research, building

our own is starting to feel feasible. It sounds like a successful

black

soldier fly bin will have good drainage at the bottom, air holes at the

top to let in adults wanting to lay their eggs, and a ramp for the

larvae to crawl up and out into the collection bucket.

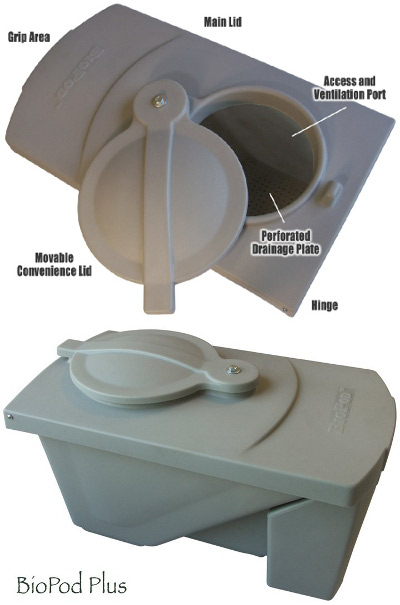

Raising black soldier

flies is a relatively new endeavor, and there only seems to be one

company producing pre-made bins. The original bin was called a

Biopod, but now there are two different types of commercial bins

available --- the Biopod Plus (which replaced the original Biopod) and

the larger Protapod.

If you were going to buy

one of these bins new, you'd be shelling out $180 for the Biopod Plus, which composts 5 pounds

of food waste per day, or $350 for the Protapod, which composts 20

pounds of food waste per day. Both bins are way too expensive for

us, but they do serve as templates for the do-it-yourselfer. The

ramp seems to be the complicated part of the system, since it needs to

start at the bottom of the bin and lead up to the top at no more than a

40 degree angle. Most homemade bins I've seen have mimicked the

original Biopod (and Protapod), trying to make a ramp lining the inside

of a circular bin, but various websites report that it's tough to

attach the ramp to the inside of the bin since it's wet in there and

the larvae work hard to tear everything apart. Instead, the

rectangular bin of the Protapod Plus with the simpler ramp seems like a

system that could be replicated on the home scale with much more ease.

pounds of food waste per day. Both bins are way too expensive for

us, but they do serve as templates for the do-it-yourselfer. The

ramp seems to be the complicated part of the system, since it needs to

start at the bottom of the bin and lead up to the top at no more than a

40 degree angle. Most homemade bins I've seen have mimicked the

original Biopod (and Protapod), trying to make a ramp lining the inside

of a circular bin, but various websites report that it's tough to

attach the ramp to the inside of the bin since it's wet in there and

the larvae work hard to tear everything apart. Instead, the

rectangular bin of the Protapod Plus with the simpler ramp seems like a

system that could be replicated on the home scale with much more ease.

Black

Soldier Fly Blog's DIY five gallon bucket bin has been tried by several

folks and is reported to do quite well, although you have to manually

raise and lower the ramp. The site is a great place to start your

research into black soldier flies, but the bin is too small for most

people, handling only about a pound of food scraps per day.

My favorite DIY bin so

far has been the

one pictured below,

which uses the same idea as the Biopod Plus to make a simple, mid-scale

bin out of a tupperware container and some PVC pipe. The PVC

method makes it seem like you could scale this version

up

indefinitely. You can see a

similar bin with more step by step instructions here. Some experts worry

that the larvae won't be able to find the ramps in this sytem, but

others report that they get very good crawl-off.

My favorite DIY bin so

far has been the

one pictured below,

which uses the same idea as the Biopod Plus to make a simple, mid-scale

bin out of a tupperware container and some PVC pipe. The PVC

method makes it seem like you could scale this version

up

indefinitely. You can see a

similar bin with more step by step instructions here. Some experts worry

that the larvae won't be able to find the ramps in this sytem, but

others report that they get very good crawl-off.

When

designing your bin, keep in mind that surface area determines how much

food waste your bin will compost per day. Every square foot of

surface area will allow you to put in about 3 pounds of food waste, so

for the 18 pounds of food waste currently going begging from our food

scrap program every

day, we would need 6 square feet of bin. It

seems remarkable that such a small bin could handle so much waste, but

black soldier flies are insatiable.

surface area will allow you to put in about 3 pounds of food waste, so

for the 18 pounds of food waste currently going begging from our food

scrap program every

day, we would need 6 square feet of bin. It

seems remarkable that such a small bin could handle so much waste, but

black soldier flies are insatiable.

That said, black soldier

flies aren't out flying in cold weather and

their larvae can't work when temperatures are too cool, so this might

not be the short-term solution for our extra food scraps after

all. Stay tuned for more on the black soldier fly life cycle and

how to winterize bins in later posts.

| This post is part of our Black Soldier Fly lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

This looks dangerous, but

feels safer than using a step ladder on uneven ground.

I

took advantage of a warm, sunny afternoon to

dip into the hives. As I suspected, the second weak

hive

was dead. I hadn't been entirely sure because our strong hive

found both empty hives so quickly that there were always bees coming in

and out, carrying honey home to their own colony. The robbing is

a good sign, since most people report that bees won't steal honey from

a colony collapse disorder hive --- more data to support my hypothesis

that my dead hives were due to excessive and sudden cold snaps combined

with (perhaps) too high varroa mite numbers.

I

took advantage of a warm, sunny afternoon to

dip into the hives. As I suspected, the second weak

hive

was dead. I hadn't been entirely sure because our strong hive

found both empty hives so quickly that there were always bees coming in

and out, carrying honey home to their own colony. The robbing is

a good sign, since most people report that bees won't steal honey from

a colony collapse disorder hive --- more data to support my hypothesis

that my dead hives were due to excessive and sudden cold snaps combined

with (perhaps) too high varroa mite numbers.

Inside the living hive, parts

of

two frames were already full of brood

in all stages of development (maybe a third of a frame of brood

total.) Since this hive is our only hope at the moment, I

lavished them with honey and pollen, moving a full brood box from the

other hives on top of their half-full brood box so that the colony will

have plenty

to eat. Not

that they need it --- they're already carting home wild pollen.

But I figure I might as well save them the trouble of flying over to

the

neighboring hive to steal the abandoned honey.

Inside the living hive, parts

of

two frames were already full of brood

in all stages of development (maybe a third of a frame of brood

total.) Since this hive is our only hope at the moment, I

lavished them with honey and pollen, moving a full brood box from the

other hives on top of their half-full brood box so that the colony will

have plenty

to eat. Not

that they need it --- they're already carting home wild pollen.

But I figure I might as well save them the trouble of flying over to

the

neighboring hive to steal the abandoned honey.

Now it's just a waiting

game. How soon will the hive be so full

of brood that I can split

it in half? I

saw the first dandelion

flower this week, which is a cue that spring has advanced far enough

to install new package bees, and I hope our bees also consider that

brilliant yellow orb a sign that they should have a baby boom.

Now it's just a waiting

game. How soon will the hive be so full

of brood that I can split

it in half? I

saw the first dandelion

flower this week, which is a cue that spring has advanced far enough

to install new package bees, and I hope our bees also consider that

brilliant yellow orb a sign that they should have a baby boom.

I'm tempted to say that

the farm feels empty with just one hive of bees, but the truth is that

those workers are ubiquitous. In the last week, I've seen them

out at the worm bin, inside at the forsythia I'm forcing on the kitchen

table (left the window cracked on a warm day --- oops!), and buzzing

around me as I worked in the garden. Our honeybees are never out

of sight, out of mind.

Black soldier flies are probably the least domesticated of the

invertebrates we work with on our farm. Unlike managing a worm

bin, when managing

black soldier flies you have to be aware that your

insects spend part of their life cycle outside the bin, so you need to

find a way to attract these wild critters to lay their eggs in your

rotting food scraps. This task has two parts --- producing just

the right scent and then providing optimal egg-laying habitat.

Black soldier fly adults

don't eat, but they know that their offspring

are going to be hungry, so the females are drawn to the odor of rotting

food. If you live out in the boondocks like we do, you can

probably just throw some food scraps in your bin at the right time of

year and wait for the noxious smell to attract momma flies. But

if you're putting your black soldier fly bin outside your back door and

live in an urban setting, you might want to try out one of the

attractants shown to bring in black soldier flies without

also attracting complaining neighbors. Dried corn soaked in water

so that it ferments is supposed to be a good attractant, as is sour

milk. If you have a friend who's already running a black soldier

fly bin, you can ask for some of his compost tea and paint the liquid

on the inside of the lid of your own bin --- black soldier flies

are attracted to the

scent of other black soldier flies.

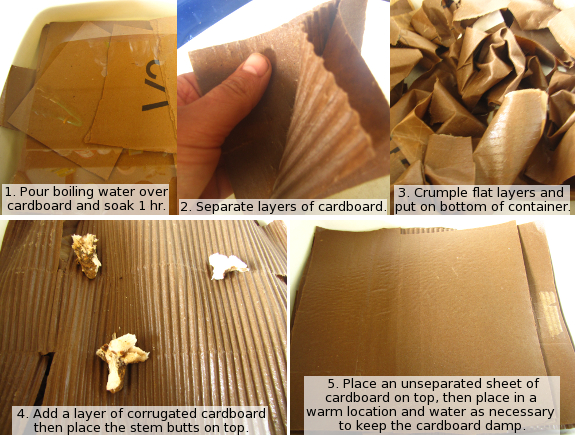

Unlike house flies, black

soldier flies

won't lay their eggs directly

into the rotting food, so you also have to give the mother fly a spot

to lay her eggs. In a pinch, she'll lay her eggs on the inside

walls of the bin, but it's better to make her a cardboard egg-laying

station. Just cut small strips of corrugated cardboard and

attach them to the inside of the lid of the bin so that lots of

crevases are exposed. Momma fly will lay her eggs inside the

cardboard corrugations, and when they hatch, the larvae will drop down

into the rotting food below.

Unlike house flies, black

soldier flies

won't lay their eggs directly

into the rotting food, so you also have to give the mother fly a spot

to lay her eggs. In a pinch, she'll lay her eggs on the inside

walls of the bin, but it's better to make her a cardboard egg-laying

station. Just cut small strips of corrugated cardboard and

attach them to the inside of the lid of the bin so that lots of

crevases are exposed. Momma fly will lay her eggs inside the

cardboard corrugations, and when they hatch, the larvae will drop down

into the rotting food below.

Using these tips, you

should get black soldier flies coming to your

bin...as long as you're trying at the right time of year. Adults

fly only during warm weather, with April being the earliest you're

likely to see any and with the majority coming out later in the

summer. So if you build your bin now, you'll want to wait to bait

it until you're getting ready to plant your summer garden. Or you

can jump the gun and buy some larvae, but be aware that the larvae

won't turn into adults until warm weather, so their population won't

expand in your bin the way worms would. I'm not sure it's worth

it to buy black soldier fly larvae unless you live in an area where

they aren't found in the wild and are hoping to jumpstart a wild

population.

| This post is part of our Black Soldier Fly lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The used

pallets are working out nicely as construction material for the new

chicken coop.

When I put the second

round of food scraps in the worm

bin this week, I was surprised to find some worms under fresh

bedding that I'd laid out on the far side of the bin to drain.

This area is six feet away from where we'd introduced the worms and had

no food to attract them, making me wonder what worms were doing there.

My first thought was that the

worms might actually be run-of-the-mill earthworms since I'd had the

cardboard bedding sitting out on the ground before soaking it and

adding it to the worm bin, and I'd noticed at least a dozen worms

taking advantage of the moist hiding place. However, a close look

at the foraging worms in the bin versus a

typical earthworm from outside the bin showed that the foraging worms

were redworms --- notice the almost orangey cast to the redworms versus

a purplish cast to the random earthworm, and the obvious yellowish

lines around

the redworms.

My first thought was that the

worms might actually be run-of-the-mill earthworms since I'd had the

cardboard bedding sitting out on the ground before soaking it and

adding it to the worm bin, and I'd noticed at least a dozen worms

taking advantage of the moist hiding place. However, a close look

at the foraging worms in the bin versus a

typical earthworm from outside the bin showed that the foraging worms

were redworms --- notice the almost orangey cast to the redworms versus

a purplish cast to the random earthworm, and the obvious yellowish

lines around

the redworms.

Poking around inside the

bin, I also discovered that the worms had found all of the food scraps,

although they seemed to be congregated in some areas at much higher

concentrations than in others. I guess worms travel further than

I give them credit for. So, the question is --- how do worms

decide where they want to go? Do they just move randomly until

they hit something good to eat, or can they smell food from a

distance? Do they give off any chemicals to attract their buddies

when they find a good stash of vittles? Anyone know a good source

of information on redworm biology, behavior, and ecology?

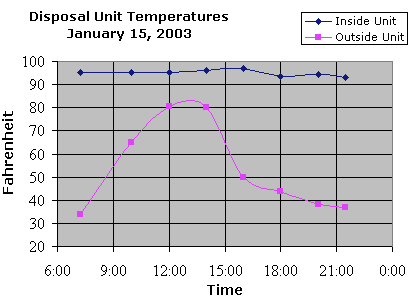

Although it's tough to get a

black soldier fly bin started during cold weather, some folks theorize

that you can keep summer-started bins operating all winter. Since

the larvae produce a lot of heat as they consume your food waste, a

piece of styrofoam placed on top of the compostables may keep the

larvae above the 70 degrees Fahrenheit they need in order to stay

active.

Although it's tough to get a

black soldier fly bin started during cold weather, some folks theorize

that you can keep summer-started bins operating all winter. Since

the larvae produce a lot of heat as they consume your food waste, a

piece of styrofoam placed on top of the compostables may keep the

larvae above the 70 degrees Fahrenheit they need in order to stay

active.

While winterizing a

black soldier fly bin sounded intriguing at first, the more I

researched it, the more I felt that I should probably just plan on

using the larvae during the summer months. An exhaustive search

of the internet turns up lots of folks who theorize about winterizing

their black soldier fly bins, but no one north of Florida who actually

kept their larvae active year-round. The problem is that if your

larvae stay active, they'll crawl out of the bin and pupate pretty

quickly, which leaves your bin empty of larvae since the adults won't

be laying fresh eggs in the winter.

On the other hand, if

you have the freezer space, you can toss extra summer pupae into your

larder for winter chicken treats. And since cold weather seems to

put the insects into a semi-hibernatory state, I wonder if you could

store a bucket of live pupae in a root cellar. Have you tried any

methods of extending your black soldier fly season into the winter

months?

| This post is part of our Black Soldier Fly lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I made this coop taller

inside so I could have room to add extra roosting areas.

Something tells me that our rooster would feel more in charge if he

had a spot slightly above the primary area where he can watch over his

flock.

When I pruned

and mulched the berries a few weeks ago, I left the dandelions that

had grown up in the row but threw a bunch of leaves on top of

them. My goal was to get sweet, blanched dandelion leaves with no

work, and my experiment succeeded quite well. Too bad there were

only a couple of plants there to work with.... I had to round out

my scavenging with plain old dandelions out of the yard to come up with

enough greens to slip into our early spring, all-from-the-garden omelet.

When I pruned

and mulched the berries a few weeks ago, I left the dandelions that

had grown up in the row but threw a bunch of leaves on top of

them. My goal was to get sweet, blanched dandelion leaves with no

work, and my experiment succeeded quite well. Too bad there were

only a couple of plants there to work with.... I had to round out

my scavenging with plain old dandelions out of the yard to come up with

enough greens to slip into our early spring, all-from-the-garden omelet.

Although you probably

think I'm nuts, I hunted high and low for named-variety dandelion seeds

and ended up settling for chicory (aka Italian Dandelion). Since

they're perennials, both chicory and dandelions will feed you greens

long before any unprotected annual is regularly putting out leaves, and

this is the time of year when I'm willing to put up with a bit of

bitterness to get fresh food. Eric Toensmeier's Perennial Vegetables noted that some  chicory varieties are

perennials while others are annuals, and I couldn't find any

specifically labelled "perennial" during my seed hunt, so I eventually

settled upon Catalogna Special and Red Rib from Johnny's. I'm

trying out both varieties, along with lovage, in the forest garden and

will hope that at least some of them become a self-maintaining

perennial addition to our garden.

chicory varieties are

perennials while others are annuals, and I couldn't find any

specifically labelled "perennial" during my seed hunt, so I eventually

settled upon Catalogna Special and Red Rib from Johnny's. I'm

trying out both varieties, along with lovage, in the forest garden and

will hope that at least some of them become a self-maintaining

perennial addition to our garden.

Anthony Liekens has created a

masterpiece with this geodesic

dome chicken coop.

He's done a great job

documenting how a person can take 30 isosceles triangles, 9 equilateral

triangles, a box of screws and some plumbers strapping and make such an

awesome home for his chicken.

I think I would have added

some sort of roosting bar inside. although I'm sure the elegant

geometry of the dome makes his hen feel safe and special.

My compost

bin was dog-proof,

just as I hoped. Unfortunately, it wasn't squirrel-proof.

My compost

bin was dog-proof,

just as I hoped. Unfortunately, it wasn't squirrel-proof.

We usually walk past the

compost/worms/parking area at least twice a day while walking Lucy, and

that tends to keep critters away, but when we got flooded in, the

wildlife got bold. As soon as I was able to cross the creek, I

peered in the compost bin and saw two big holes where some kind of wild

animal (I'm guessing squirrels) had squeezed through the lattice and

had a feast.

Although it doesn't

matter too much if a few squirrels nibble on the food scraps, I want to

keep my compost, so I added a layer of chicken wire around the outside

of the bin. I'm not sure if even that will be enough to keep out

a determined critter. I guess we'll just have to wait and see if

someone else breaks in to eat.

Anna and I went to a couple of

incredible lectures on mycoremeditaion and mycoforestry this weekend by

Tradd Cotter

at the Asheville growers school.

Mr Cotter gave a riveting

talk on the importance of mushrooms in our ecosystem and how we can use

low tech methods to give your fungi a helping hand. He sells bulk

spawn, plugs, kits, extracts and supplies at his website Mushroom Mountain.com,

which has become our new source for everything fungus related.

Not only did the seats fill

up on Sunday's talk, but the floor filled up and I even saw a few people

standing in the hallway listening. Clearly his passion for mushrooms is

contagious and with any luck it will spread just like the mycelium from which

this magical fruit is born from.

We had an astounding three

day weekend in Asheville, meeting great friends (hi, Everett and Missy!),

exploring established forest gardens (thank you, Alice and Dudley!),

and learning about mushrooms, mushrooms, mushrooms (and a few other

things) at the Organic Grower's School. I'll regale you with our

gleanings over the next few days, once my brain makes sense of all of

that new information.

We had an astounding three

day weekend in Asheville, meeting great friends (hi, Everett and Missy!),

exploring established forest gardens (thank you, Alice and Dudley!),

and learning about mushrooms, mushrooms, mushrooms (and a few other

things) at the Organic Grower's School. I'll regale you with our

gleanings over the next few days, once my brain makes sense of all of

that new information.

As we drove home, we

looked down over the hill...and saw our creek

spreading out across the whole valley. I've never been able to

see our creek from that road before, so I knew we were in for a hard

walk home. We followed Mark's path across

the fallen tree (me

crawling to protect the electronics I wasn't willing to leave in the

car), then walked up the floodplain as dusk fell.

Two thirds of the way

home, we discovered the flaw in our plan --- the

alligator swamp was flooded just like the creek, and we either had to

climb up and around the slippery hillside or push our way through the

cold water. The former option is the slower, drier way, but we

opted to strip from the waist down and just plug on through. That

water was cold on our bare legs, but soon we were home to a fire in the

wood stove and a couple of lap cats. Quite a difference between

our farm and the big city, but I have to admit that I like it better

here...even during frigid floods.

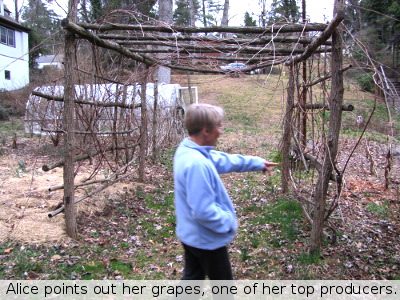

Five

years ago, Alice and Dudley started putting in edible perennials

in their large backyard, at the same time that their neighbor Robert

did the

same. Walking through their gardens was a bit like reading

through those catalogs I drool over, full of fruits I'd heard of but

had never seen in the flesh, like goumi, jujube, and more. Other

unusual plants were familiar from my own garden, where they haven't had

time to achieve

their full potential. Since most of Alice, Dudley, and Robert's

perennials were old enough to fruit, I was

Five

years ago, Alice and Dudley started putting in edible perennials

in their large backyard, at the same time that their neighbor Robert

did the

same. Walking through their gardens was a bit like reading

through those catalogs I drool over, full of fruits I'd heard of but

had never seen in the flesh, like goumi, jujube, and more. Other

unusual plants were familiar from my own garden, where they haven't had

time to achieve

their full potential. Since most of Alice, Dudley, and Robert's

perennials were old enough to fruit, I was  curious to see which ones

had been exciting (or disappointing) surprises in a climate much like

my own.

curious to see which ones

had been exciting (or disappointing) surprises in a climate much like

my own.

First for the big

disappointment. Both Alice and Robert told me

that their gojiberries never fruited. In our climate, the variety

they planted (and which I have in my own garden, a gift from Alice)

blooms so late that the fruits never have time to form.

Meanwhile, the thorny shrub takes over the garden. Robert has

plans to root out his gojiberries this year, and after hearing their

experiences, I think I'm not going to give mine the extra grace year

I'd promised it and will follow suit. There's no room in a

working garden for an underachiever.

Alice was also somewhat

disappointed in her bush cherries, noting that

the fruits were small and seedy, so they were tough to pit for

cooking. Robert mentioned that his jujube hadn't produced fruit

in five years. And Alice's jostaberry hasn't fruited in that time

frame

either, although she mentions that the problem could be shade.

Other non-fruiters included Rosa

rugosa, Japanese

walnut (although nuts take longer and this plant still has hope), hardy

kiwi, plum yew, and

paw-paw.

frame

either, although she mentions that the problem could be shade.

Other non-fruiters included Rosa

rugosa, Japanese

walnut (although nuts take longer and this plant still has hope), hardy

kiwi, plum yew, and

paw-paw.

Meanwhile, I

picked the gardeners' brains about their top perennials

--- ones that produce delicious fruit with little work.

Traditional fruits were at the top of each list --- ever-bearing

red-raspberries and thornless blackberries for Alice and a peach and

Asian pear for Robert. But so were some less usual fruits ---

both agreed that their Asian

persimmon (Eureka)

and goumi were tops for

flavor and ease. It sounds like I might need to add some of both

in our own garden.

| This post is part of our Real Forest Gardening lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

You can find a morel in every state except Florida and

Arizona, you just need to know where to look and how.

You can find a morel in every state except Florida and

Arizona, you just need to know where to look and how.

1. Carry a meat/soil

thermometer with you at

all times to test for when the season begins. Check the soil

temperature in the morning shade. When you find a spot around 50 it's

time to begin hunting, 58 is when it's all over and your only hope is

to go to higher elevations.

2. If you hunt in an old

orchard be aware that morels can absorb heavy metals which often linger

for decades in the soil from the spraying of a wide variety of toxins.

You can get a heavy metal testing kit, but I think it would be easier

and safer to go looking in another spot.

3. Go check out Tradd

Cotter's concise page on morel hunting. He's got a lot more tips

like which trees to look out for and what other mushrooms and plants

are making their appearance at around the same temperature.

Yes...the mushroom in the

picture is real and not a photoshop trick, proof that this guy knows a

thing or two about what it takes to find them and he's working on new techniques to

cultivate them at home.

I'd been watching a wild

oyster mushroom budding out of a fallen snag in the floodplain for a

couple of weeks, but something ate it before I thought it was big

enough to pick. So I was thrilled to find an oyster mushroom

growing on a stump on the campus of the University of North

Carolina-Asheville during the Organic Grower's School. I broke

the oyster loose and put it in my coat pocket, where I surprised myself

throughout the day by putting my hand in the pocket and touching a

damp, slimy object.

I'd been watching a wild

oyster mushroom budding out of a fallen snag in the floodplain for a

couple of weeks, but something ate it before I thought it was big

enough to pick. So I was thrilled to find an oyster mushroom

growing on a stump on the campus of the University of North

Carolina-Asheville during the Organic Grower's School. I broke

the oyster loose and put it in my coat pocket, where I surprised myself

throughout the day by putting my hand in the pocket and touching a

damp, slimy object.

Home at last, the mushroom

was a bit battered and dirty from its long ride, but I figured it was

in good enough shape to start up my cardboard

propagation

again. After soaking cardboard, separating the corrugated center

from the flat outer layers and layering the mushroom butts between the

corrugated cardboard sheets, I wandered outside to think about our

cultivated mushrooms. And there I found yet more oysters ready to

eat! Both Pohu and Blue Dolphin had sent out several fruiting

bodies. I used up our last container of frozen mushrooms two

weeks ago and was just wishing for more to go in our lasagna --- good

thing our mushroom logs came through.

Home at last, the mushroom

was a bit battered and dirty from its long ride, but I figured it was

in good enough shape to start up my cardboard

propagation

again. After soaking cardboard, separating the corrugated center

from the flat outer layers and layering the mushroom butts between the

corrugated cardboard sheets, I wandered outside to think about our

cultivated mushrooms. And there I found yet more oysters ready to

eat! Both Pohu and Blue Dolphin had sent out several fruiting

bodies. I used up our last container of frozen mushrooms two

weeks ago and was just wishing for more to go in our lasagna --- good

thing our mushroom logs came through.

Yesterday,

I showcased the trees,

shrubs, and vines that did best in two Appalachian forest gardens, but what about the lower

layers? The first thing I was struck by in both Alice and

Robert's gardens was their deep mulches. Finding enough waste

materials to mulch with is always a struggle on our farm, but Alice and

Robert had both tapped into the copious organic matter being thrown

away in cities every day.

Yesterday,

I showcased the trees,

shrubs, and vines that did best in two Appalachian forest gardens, but what about the lower

layers? The first thing I was struck by in both Alice and

Robert's gardens was their deep mulches. Finding enough waste

materials to mulch with is always a struggle on our farm, but Alice and

Robert had both tapped into the copious organic matter being thrown

away in cities every day.

Alice uses leaves --- a

system easy to replicate for any city-dweller --- but Robert's method

of finding mulch is even more elegant. Robert is a bowl-turner

who makes wooden bowls in his home studio, so he scavenges fallen trees

from the neighborhood. The trees are cut into pieces to make into

bowls, and the curly shavings are spread heavily on the soil of his

garden. Add in some alpaca manure for fertility, and you've got a

very healthy, happy forest garden.

Alice uses leaves --- a

system easy to replicate for any city-dweller --- but Robert's method

of finding mulch is even more elegant. Robert is a bowl-turner

who makes wooden bowls in his home studio, so he scavenges fallen trees

from the neighborhood. The trees are cut into pieces to make into

bowls, and the curly shavings are spread heavily on the soil of his

garden. Add in some alpaca manure for fertility, and you've got a

very healthy, happy forest garden.

Although

it was too early to see most of the herbs in the forest garden, a few

were already poking up through the mulch. Alice had stinging

nettles along the shady edge of her garden and sorrel and horseradish

mixed in among the trees and shrubs. She mentioned that she

wished she hadn't planted the horseradish --- the plants are extremely

vigorous and nearly impossible to remove if you change your mind.

I'll have to come back in the summer to see the lower level of these

two forest gardens in all their glory.

Although

it was too early to see most of the herbs in the forest garden, a few

were already poking up through the mulch. Alice had stinging

nettles along the shady edge of her garden and sorrel and horseradish

mixed in among the trees and shrubs. She mentioned that she

wished she hadn't planted the horseradish --- the plants are extremely

vigorous and nearly impossible to remove if you change your mind.

I'll have to come back in the summer to see the lower level of these

two forest gardens in all their glory.

| This post is part of our Real Forest Gardening lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Another afternoon working on

the used

pallet chicken coop makes flock moving day that much closer.

While

planting lettuce, onions, and spinach yesterday, I pondered the pros

and cons of quick

hoops versus cold frames. I'm not going to have

any side by side comparisons this year, but I have started noticing

that each system works a bit differently. Here are the main

factors to consider when choosing whether to build a quick hoop or a

cold frame:

While

planting lettuce, onions, and spinach yesterday, I pondered the pros

and cons of quick

hoops versus cold frames. I'm not going to have

any side by side comparisons this year, but I have started noticing

that each system works a bit differently. Here are the main

factors to consider when choosing whether to build a quick hoop or a

cold frame:

- Light penetration --- This is where I suspect that quick hoops win. Cold frames have wooden walls that shade a relatively large area on the south side of the bed, and in early spring I've noticed that lettuce just won't germinate in that cold spot. Quick hoops don't create any shady areas, and so far I've seen no cold spots that restrict germination.

- Heat capture --- I have

no data here, but my gut says that the lower profile of cold frames

would hold the day's heat closer to the plants. However, Eliot

Coleman's experiments suggest that light penetration is more important

than heat capture when growing cold weather crops, so quick hoops'

lower ability to capture heat might not matter.

Water penetration ---

Here quick hoops lose. The flat top of cold frames lets water

pool on the row cover fabric just long enough to drip down through and

water your bed, but water mostly runs off the quick hoop. I was

surprised to see dry spots inside our quick hoops this week despite

about eight

inches of rain in as many days.

Water penetration ---

Here quick hoops lose. The flat top of cold frames lets water

pool on the row cover fabric just long enough to drip down through and

water your bed, but water mostly runs off the quick hoop. I was

surprised to see dry spots inside our quick hoops this week despite

about eight

inches of rain in as many days.

- Snow load --- The same structural features that make water slide off quick hoops makes snow slide off as well, so I suspect quick hoops would stand up much better under heavy snow conditions than cold frames do.

- Wind --- The higher

profile of quick hoops catches wind much more than our cold frames

do. We haven't had any more major trouble since I added the rebar

to the sides, but we also don't live in a very windy climate. If

you live in a treeless area, you might be better off with cold frames.

Ease of opening --- This

is a toss-up, but I think that cold frames win. It takes me about

five minutes to carefully unroll the rebar and take the row cover

fabric off the quick hoops, although if I just want to peek in I can

simply untie one end and stick my head under the fabric. My cold

frames are usually much

easier to get into. That said, I suspect that we can come up with

a more accessible quick hoop as we play around with the design.

Ease of opening --- This

is a toss-up, but I think that cold frames win. It takes me about

five minutes to carefully unroll the rebar and take the row cover

fabric off the quick hoops, although if I just want to peek in I can

simply untie one end and stick my head under the fabric. My cold

frames are usually much

easier to get into. That said, I suspect that we can come up with

a more accessible quick hoop as we play around with the design.

- Cost --- If you have old

lumber lying around like we do, cold frames are a big winner since they

only cost as much as the fabric and screws. On the other hand, if

you're buying the materials new, I estimate that our quick hoop costs

29 cents per square foot (if you use the cheap PVC rather than the

hot/cold version) versus 64 cents per square foot for a cold frame (if

you use untreated 2X10s).

Longevity of fabric ---

After the initial construction, the only regular cost for either system

is replacing tattered row cover fabric. I've noticed that the

tautness of the quick hoop fabric makes it very

easy to punch your fingers through, and the rebar tries to snag and

tear holes as well. However, our animals don't think quick hoops

look like a fun thing to jump on, which is the fastest way to lose row

cover fabric, so we might actually get a bit more longevity out of our

quick hoop fabric than out of our cold frames.

Longevity of fabric ---

After the initial construction, the only regular cost for either system

is replacing tattered row cover fabric. I've noticed that the

tautness of the quick hoop fabric makes it very

easy to punch your fingers through, and the rebar tries to snag and

tear holes as well. However, our animals don't think quick hoops

look like a fun thing to jump on, which is the fastest way to lose row

cover fabric, so we might actually get a bit more longevity out of our

quick hoop fabric than out of our cold frames.

- Modularity --- Our raised

beds aren't all the same width or length, so I've found it difficult to

move cold frames from bed to bed. With my rotten, salvaged

lumber, cold frames also tend to fall apart when I move them.

Quick hoops are much more modular since you can just drive in your

rebar stakes at the edges of the bed and cover irregularly shaped beds,

using the same raw materials in different years to protect beds with

somewhat different dimensions.

Speed of contstruction

--- Once we knew what we were doing, it took about two hours of my time

and half an hour of Mark's time to make a 23 foot long quick

hoop. Cold frames require two people for more of the process, but

probably take about the same number of man-hours.

Speed of contstruction

--- Once we knew what we were doing, it took about two hours of my time

and half an hour of Mark's time to make a 23 foot long quick

hoop. Cold frames require two people for more of the process, but

probably take about the same number of man-hours.

- Ease of storage --- Quick hoops win big here. During the summer when I don't need our cold frames, they're leaning up against a fence or wall, which creates a weedy spot that's hard to mow around. Quick hoops disassemble into a few long poles and a bit of fabric, so they'll be easier to fit into storage.

- Aesthetics --- Our cold

frames are pretty enough, but there's just something striking about the

domed quick hoops that tempts me out into the garden.

Worm collection --- I don't know if

this is a positive or a negative, but our quick hoop seems to collect

earthworms in the rolled up fabric on the edges. I pulled this

handful of worms out as I opened up the quick hoop Tuesday, and the

chickens were very appreciative.

Worm collection --- I don't know if

this is a positive or a negative, but our quick hoop seems to collect

earthworms in the rolled up fabric on the edges. I pulled this

handful of worms out as I opened up the quick hoop Tuesday, and the

chickens were very appreciative.

Overall, my gut feeling

is that quick hoops are the winner, although

I'd love to figure out a way to make them easier to get into. I'm

pondering making long, skinny sandbags out of old dogfood sacks that

can be laid along the entire edge of the structure. Stay tuned

for more details!

Whenever I tell people

about forest gardening, the inevitable reply is "You really expect to

grow all of your food with perennials?" I'm quick to set them

right, explaining that we definitely plan to keep growing our

delectable tomatoes, broccoli, and other row crops. Forest

gardening and traditional annual gardens work well together --- you can

set aside the best land for your vegetable garden and put your forest

garden on the sloping hillside that would wash away if you tilled it or

down in the swamp where you'd never be able to plow. You can also

plant traditional vegetables amid your forest garden plants in sunny

gaps (especially as your perennials are slowly filling out.)

Alice and Dudley mixed and matched annuals and perennials very

elegantly in their city backyard.

Since trees run along

the south side of their property, they take advantage of that partial

shade to plant their forest garden crops. Real shade lovers like

nettles, currants, and elderberries gradually give way to trees and

shrubs that need full sun. In a gap in the forest garden, Alice

had built a beautiful raised bed out of colored bottles and planted it

with garlic.

Meanwhile, Dudley had

selected the sunniest spot near the north side of the yard for growing

tomatoes and lettuce in his homemade greenhouse. You can read

about how he made this 20 foot long greenhouse for about $300 in just a

few hours on his website. You might notice in

this photo that the plastic is tearing --- Dudley explained that the

greenhouse covering is finally starting to get too brittle to repair

after five years and will need a new sheet of plastic.

I hope that Alice and

Dudley's garden will inspire some of you to take a look at your own

growing space and mix and match your annuals and perennials.

| This post is part of our Real Forest Gardening lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I

used several furring strips as a roof supporting material on the used

pallet chicken coop because it's all we had on hand at the time and

I like experimenting with cheap options.

I

used several furring strips as a roof supporting material on the used

pallet chicken coop because it's all we had on hand at the time and

I like experimenting with cheap options.

The goal is to eventually

arrive at a design that is easy and cheap to replicate while lasting a

decent amount of time.

Lately I'm liking this

geodesic frame structure which I think is using 1x1's or 2x4's and

might even be able to be done with furring strips. Maybe as a future

mushroom lab or some sort of fruit tree hoop house or some other yet

unknown function.

As a gardener, I have a hard

nose and a green thumb. In other words, I tell my plants "sink or

swim" and --- mostly --- they swim.

As a gardener, I have a hard

nose and a green thumb. In other words, I tell my plants "sink or

swim" and --- mostly --- they swim.

Which is all a long way

of explaining why I transplanted my onion

seedlings into the

garden this week even though they really aren't ready for the cold

weather that's yet to come. I hedged my bets by putting half of

the seedlings under a quick

hoop, then tempted

fate by planting the rest of the seedlings out in the open. I

figure that if the baby onions with no protection thrive, I will have

figured out the easiest method to get good onions from seed in our

climate --- start seeds in a flat and then put them out in the garden

when they have two leaves. I'm willing to risk some seedlings in

pursuit of long term laziness.

Of course, all that

experimentation isn't what I'm hanging our hopes of a summer onion crop

on. I direct-seeded another 200 seeds under the quick hoop and

yet another 200 out in the open. I figure that by the end of this

spring, I'll have tried most of the possible permutations for onion

seedling growing and will have chosen a method to use in following

years.

Meanwhile, my nectarine

tree thinks I might just get lucky this year with my transplanted

onions. The tree is already in the green bud stage, which means

she's counting on no

weather colder than 21 degrees so that she can keep 90% of her fruit. Here's hoping she's

right.

Zev Friedman, vice president

of Living Systems

Design, regaled us

with an exciting talk about Real Life Forest Gardening at the Organic

Grower's School. He included a list of the top 13 species that he

recommends for every forest garden, reproduced below:

Zev Friedman, vice president

of Living Systems

Design, regaled us

with an exciting talk about Real Life Forest Gardening at the Organic

Grower's School. He included a list of the top 13 species that he

recommends for every forest garden, reproduced below:

Sochan aka Cutleaf Coneflower (Rudbeckia

laciniata) is an

herb that can grow in shade or sun, damp or dry soil, and will feed you

spring greens followed by echinacea-like medicine in the summer.

I'd never heard of sochan and would be very curious to hear from

someone who has tried it in their own garden. I have a hard time

believing that sochan would win out over winter kale in a taste test,

but Zev asserts that he's changed over entirely to perennial greens.

Wood

nettle (Laportea

canadensis) is a

shade-loving native that's related to the more familiar (but

non-native) stinging nettle. Zev notes that wood nettle is

tastier but has fewer medicinal properties than stinging nettle.

I have wood nettle growing all over the woods of my property and I've

been meaning to bite the bullet and taste it --- maybe this spring!

American elderberry (Sambucus

canadensis) is

grown for its fruit, and also for the shrub's vigorous habit that

allows it to form hedges and retain soil along streams. We've got

wild elderberries and I even let a shrub grow up in our forest garden,

but I don't think this plant will become one of our primary food

producers --- very few people eat the fruits raw and we're not

wine-drinkers or jam-eaters.

American elderberry (Sambucus

canadensis) is

grown for its fruit, and also for the shrub's vigorous habit that

allows it to form hedges and retain soil along streams. We've got

wild elderberries and I even let a shrub grow up in our forest garden,

but I don't think this plant will become one of our primary food

producers --- very few people eat the fruits raw and we're not

wine-drinkers or jam-eaters.

Mulberries (Morus alba, M. rubra, and M. nigra) produce edible fruit,

fiber, fodder, and wood for bow-making. I'll eat mulberry fruits,

but I tend to relegate them to the bottom of my taste test list.

Nevertheless, I have planted an ever-bearing

mulberry since the

copious fruits are great for chickens and other animals.

Lamb's

quarter (Chenopodium

album) is a

self-seeding annual green that grows in sunny, disturbed areas. I

suspect this species is of a lot more use to urban gardeners, who can

forage lamb's quarter from an abandoned lot. We try to keep the

weeds down in our garden, so don't provide much habitat for it.

Poke (Phytolacca

americana)

produces edible stalks in the summer. I've always steered clear

of it because I don't believe you get much nutrition after you boil the

greens a few times to remove the toxic substances, but Zev likes the

flavor (with plenty of butter and salt) and notes that poke stimulates

the lymph system just when you need it, at the end of a long winter.

Poke (Phytolacca

americana)

produces edible stalks in the summer. I've always steered clear

of it because I don't believe you get much nutrition after you boil the

greens a few times to remove the toxic substances, but Zev likes the

flavor (with plenty of butter and salt) and notes that poke stimulates

the lymph system just when you need it, at the end of a long winter.

Hybrid

chestnut (Castanea sp.) is grown for its nuts

and wood. American chestnuts used to be a huge component of the

Appalachian diet, and have now been replaced by Chinese

chestnuts. I've planted a few trees in out of the way spots, but

I have to admit that I'm not as keen on this nut as on others --- it's

the one nut that is nutritionally more like a grain. If I was

raising pigs, though, I'd be a chestnut-pusher.

White

oak (Quercus

alba) is grown

for the nuts and wood. I consider oak more of a livestock-food

tree than a human-food tree, but (like poke) the nuts are edible after

leaching out the toxic parts.

Deer (Odocoileus

virginianus) are

hunted for their meat and skins. Zev notes that deer prune plants

and distribute nitrogen, but that's where I think he's getting a bit

caught up in philosophy and not considering reality (a major downfall

of philosophical forest gardeners who don't garden their own

land.) I'd rather get my nitrogen from an animal that doesn't eat

up every food plant in its path!

Deer (Odocoileus

virginianus) are

hunted for their meat and skins. Zev notes that deer prune plants

and distribute nitrogen, but that's where I think he's getting a bit

caught up in philosophy and not considering reality (a major downfall

of philosophical forest gardeners who don't garden their own

land.) I'd rather get my nitrogen from an animal that doesn't eat

up every food plant in its path!

Heritage

turkey (Melagris

gallopavo) is

grown for its meat. When an audience member (not us, though I was

thinking along the same lines) asked Zev why he suggests turkeys

instead of chickens, he replied that turkeys are more capable of

dealing with predators. I could write for hours about why I think

chickens are better suited to the homestead and forest garden ---

ability to eat food scraps, taste, small size, copious eggs, etc. ---

but I'll let you draw your own conclusions.

Ducks (various species) are grown

for eggs and meat (and to remove slugs from the garden.) I've

read on several blogs, though, that ducks are very difficult to pluck

and that they lay few eggs compared to chickens. I'm sticking to

my working chicken flock.

Oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus

sp.) is

(finally!) a recommendation I can get behind whole-heartedly.

We've found that these are the easiest mushrooms to grow in our

climate, can be propagated at home, and are among the tastiest.

Zev notes that in addition to eating the mushrooms, you can also use

them for myco-remediation. (More on that next week.)

Oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus

sp.) is

(finally!) a recommendation I can get behind whole-heartedly.

We've found that these are the easiest mushrooms to grow in our

climate, can be propagated at home, and are among the tastiest.

Zev notes that in addition to eating the mushrooms, you can also use

them for myco-remediation. (More on that next week.)

Appalachian

reishi (Ganoderma tsugae) is a medicinal (and

somewhat culinary) mushroom that is Zev's response to the hemlock

woolly adelgid that is currently wiping out one of Appalachia's

keystone species. If we can't prevent the death of our mighty

hemlocks, Zev notes that we can at least grow some food on the fallen

giants.

After reading through

Zev's list, I can tell that he rates his plants quite differently than

I do. I tend to choose food species first by taste, second by

ease of growing, and only factor in multiple uses at the end.

Zev, on the other hand, clearly chooses first by multiple use, second

by ease of growth, and only considers taste at the very end.

(Either that or his taste buds are just very different from

mine.) Nevertheless, I think we can all learn a lesson just by

looking at his top 13 forest gardening species --- what other list

includes animals and fungi along with plants? We should each work

to create a diversified group of species that together provide greens,

nuts, fruits, mushrooms, and meat. What species would be on your

list?

| This post is part of our Real Forest Gardening lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Today

was one of those wet and rainy days where puttering on a project

indoors makes more sense then trying to battle the forces of spring.

Today

was one of those wet and rainy days where puttering on a project

indoors makes more sense then trying to battle the forces of spring.

While working on fixing one

of the deer deterrents I

tried out a new podcast called Stumbling

Homestead by a guy named Darcy. I skipped back to episode 9 where

he talks about keeping a family cow and was reminded about how Anna and

I recently decided to let go of the cow owning dream due to our lack of

pasture.

I like Darcy's podcasting

style and the way he presents all the trial and error steps along with

a running list of how much he paid to get started in the home milking

business. Some really invaluable information if you've ever thought

about getting a cow or just like to hear these types of homesteading

escapades.

What most impressed me was

his ability to recognize what was wrong about his first generation

milking stanchion and how he simplified it to the one in the picture

here. The two before and after pictures along with his explanations

really break it down in a way that was informative while at the same

time entertaining.

This is how I feel about

spring. It's beautiful and tender and colorful...and it has big

thorns and is an invasive species.

People who don't live on

a farm think that farmers are itching for spring right now...and we

are. But there's also the flip side of the coin. All summer

while the garden is dictating our every move, we're making a list of

the big picture projects we're saving for winter. And then all

winter we're trying to work our way through that list.

March

is when reality sets in and we realize that the other twenty things we

didn't get done just aren't happening until next winter. It's a

bit devastating to me to realize that the big picture projects left

over from our 2010 to-do list (yes, we're still working on those) are

going to be 2012 projects. Heck, if the new age pseudo-mayans are

right, maybe my rainy day moan --- "We'll never install my bathtub" --- will

really come true.

March

is when reality sets in and we realize that the other twenty things we

didn't get done just aren't happening until next winter. It's a

bit devastating to me to realize that the big picture projects left

over from our 2010 to-do list (yes, we're still working on those) are

going to be 2012 projects. Heck, if the new age pseudo-mayans are

right, maybe my rainy day moan --- "We'll never install my bathtub" --- will

really come true.

On the other hand, is it

possible to look at this baby ramp plant pushing up through the soil

under our kitchen peach and not smile? I can hardly believe that

two of the ramps I grubbed up with my fingers

in a rush last spring far too late in the season for transplanting

actually survived. And there are leaves coming out on the

elderberries, gooseberries, and gojiberries too. Our poppies have

sprouted and I can nearly taste the first spring lettuce.

The truth is that we

each make choices about what to do with our time. On the one

hand, it is a little nuts that we still take bird baths all winter four

and a half years after moving to the farm. But if you ask me

whether I'd rather have installed the bathtub or cloned oyster

mushrooms and planted spinach, swiss chard, and onions this week, I'll

tell you that there's no contest --- fresh food beats hot baths any

day. The average American's choices are hidden beneath a veil of

normalcy, but they're constantly making choices too, opting to spend

forty hours per week away from their loved ones so that they can take a

long hot bath (if they can find the time.) Our choices are more

overt, but the truth is that I'd rather be planting perennials that

will turn into a patch of edible leaves in a few years than working on

our living conditions. Bathtubs don't multiply exponentially over

time, but ramps do.

Last fall when I planted

our potato

onion and garlic bulbs, I left gaps in the

straw mulch so that the new shoots would be able to push up

through. If I'd been smart, I would have come along a month later

once the leaves showed and added straw snug up against my onion and

garlic plants. I didn't. Instead, once the snow melted, I

was chagrined to see big weed islands surrounding each plant.

At first, I figured I'd

have to hand weed each bed, but I put that off for about a month since

the ground has been way too cold to make weeding pleasant.

Eventually, it occurred to me  that I might be able to get

away with just adding another layer of straw over the problem plants

and let lack of sun do my weeding job for me. Some of these weeds

are very sneaky, and I wouldn't be at all surprised if the chickweed

slips up through the straw and continues to grow, but I figure it's

worth a shot at preventing all of that cold weather weeding.

that I might be able to get

away with just adding another layer of straw over the problem plants

and let lack of sun do my weeding job for me. Some of these weeds

are very sneaky, and I wouldn't be at all surprised if the chickweed

slips up through the straw and continues to grow, but I figure it's

worth a shot at preventing all of that cold weather weeding.

A side benefit of

mulching my Alliums

was moving our over-wintered straw off the secondary daffodil

patch. We have more daffodils than we can shake a stick at, and I

certainly wouldn't have spent energy moving the bales just to save a

few dozen of our thousands of bulbs. But with the first flowers

already opening up, I know we'll enjoy seeing a sea of yellow flowers

next week.

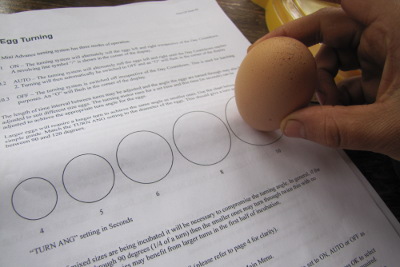

I tried ordering the type of

motor found in a rotisserie

unit and instead of

getting ones that ran on 120 volts I somehow mistakenly asked for 12

volts AC. I burned the first 2 out by applying 120 volts without

knowing any better. They only turned for a few seconds and then smoked

and sizzled.

It took me about 20 minutes

to remember a transformer from an old cordless phone was still in the

barn and its output was in the low AC range. 9 volts AC to be exact, a

full 3 volts under what I needed.

The lower voltage makes the

motor go slower, which is a good thing. Now the time in between clangs

is closer to a minute as opposed to 30 seconds. I also adjusted the

location to intersect with the two main deer paths near our blueberries.

I've got a feeling this new

configuration will last longer due to its reduced speed and low voltage.

If

you've got cute, little mushrooms popping out of your straw mulch,

chances are you've grown inky caps. The aptly named inky cap

mushrooms dissolve into a mass of black goo as they mature.

If

you've got cute, little mushrooms popping out of your straw mulch,

chances are you've grown inky caps. The aptly named inky cap

mushrooms dissolve into a mass of black goo as they mature.

Scientists

think that the life history of these mushrooms is a way of spreading

their spores more efficiently, and recent evidence suggests that

various unrelated mushrooms have come up with the same trick through

convergent evolution. Older books lump them all into one "genus"

--- Coprinus --- and I'm not enough of a

mushroom expert to tell you which of the newly split off genera my

species is actually a member of.

Scientists

think that the life history of these mushrooms is a way of spreading

their spores more efficiently, and recent evidence suggests that

various unrelated mushrooms have come up with the same trick through

convergent evolution. Older books lump them all into one "genus"

--- Coprinus --- and I'm not enough of a

mushroom expert to tell you which of the newly split off genera my

species is actually a member of.

I'm also disappointed to

discover that there doesn't seem to be much information out there about

how inky caps fit into the garden ecosystem. The fungi are

decomposers, working hard to break your straw down into compost, so I

guess that makes them beneficial (unless you were hoping not to have to

refresh the mulch this summer.) But I can't find any information

on whether inky cap inoculated straw is beneficial or harmful to garden

plants in any other way. Any ideas?

I've

been intrigued by coppicing ever since I visited the ancient New Forest

in England and saw huge trees that had been providing wood to the

locals for hundreds of years. The idea is simple --- certain

trees resprout when they're cut, so you can cut off the shoots every

five, ten, or twenty years and have a renewable source of wood without

disturbing the forest. Since I'd only read about coppicing in

Europe, I was excited to hear Zev Friedman's information on which

species can be coppiced in our neck of the woods.

I've

been intrigued by coppicing ever since I visited the ancient New Forest

in England and saw huge trees that had been providing wood to the

locals for hundreds of years. The idea is simple --- certain

trees resprout when they're cut, so you can cut off the shoots every

five, ten, or twenty years and have a renewable source of wood without

disturbing the forest. Since I'd only read about coppicing in

Europe, I was excited to hear Zev Friedman's information on which

species can be coppiced in our neck of the woods.

The eight species that

Zev considers worth coppicing in the southern Appalachians are black

locust, mulberry, willow, basswood, tulip-tree, hazelnut, black cherry,

and chestnut. These trees not only resprout copiously, the bushy

habit you get after coppicing has a benefit to the forest

gardener. For example, mulberries bear fruits on first year wood,

so the fruiting area tends to move further and further out on the

tree. By coppicing, you keep the mulberries within reach, and can

even coppice part of the tree each year so that you have young wood

ready to bear fruit annually.

On the backyard scale, you're

probably only going to have a few trees to coppice, but on the

homestead scale you might set up an entire woodlot in what's known as

"coppice with standards." Standards are full-sized trees that are

left alone and only cut every 75 to 150 years for timber, providing

shade and livestock feed in the interim. Oaks are a good choice

for standards in our area (or perhaps walnuts or sycamores in damper

areas?), and Zev recommends keeping 20 standards per acre.

On the backyard scale, you're

probably only going to have a few trees to coppice, but on the

homestead scale you might set up an entire woodlot in what's known as

"coppice with standards." Standards are full-sized trees that are

left alone and only cut every 75 to 150 years for timber, providing

shade and livestock feed in the interim. Oaks are a good choice

for standards in our area (or perhaps walnuts or sycamores in damper

areas?), and Zev recommends keeping 20 standards per acre.

Scattered amid the

standards are the smaller trees that are coppiced much more

regularly. These coppiced trees are generally spaced 6 to 10 feet

across on diagonal and provide firewood, fiber (mulberries), tender

young leaves (basswood), mushroom logs (tulip-trees for oysters and

oaks for shiitakes), and fruits or nuts. We might try coppicing

our mulberry tree and hazelnut bushes in a couple of years to see what

kind of growth form results.

| This post is part of our Real Forest Gardening lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Our hillsides are shaded

and cool and still flower-free, but I had a feeling that our recent

warm spell had tempted out the early spring

ephemerals at the sunnier Sugar Hill.

The hepatica was in full

bloom, and two beetles were checking out one flower's stamens. I

guess I know who's out pollinating at this time of year.

On the drive to town, we

saw two weeping willows starting to leaf out, and Sugar Hill's buckeyes

were also unfurling their leaves. I'd never seen a sprouting

buckeye before --- beautiful, isn't it? Since buckeye leaves are

easily nipped by heavy frosts, I guess that's one more vote for an

early spring.

No photos, but I also

saw the year's first Spring Azure butterflies. These weren't the

first butterflies of the year, though --- Mourning Cloaks, Commas, and

Question Marks were already out flying in last week's warmth.

If you live in our area

or further south, now's a great time to head out and see spring in

action!

As Mark mentioned last week, our favorite part of the Organic Growers

School was the two talks we attended led by Tradd Cotter of Mushroom

Mountain. Even

though Tradd runs a big operation, supplying

spawn both retail and wholesale and testing out fascinating fungal

partnerships in the lab, he really understands what the little guy is

looking for --- simple, low tech techniques we can use to grow

mushrooms in our backyard.

For example, while most

people will tell you to carefully drill holes,

pound in your plug spawn, and paint over the holes with beeswax, Tradd

says that you'll get nearly as good results in much less time by

cutting two inch deep gashes in logs with your chainsaw, pushing in

(cheaper) grain or sawdust spawn with your hands, and then waxing over

the holes. Everyone else tells you to inoculate your logs

in late

winter, but Tradd

says if you've got freshly cut wood, go ahead and

throw spawn in it --- you won't get quite as good survival rates, but