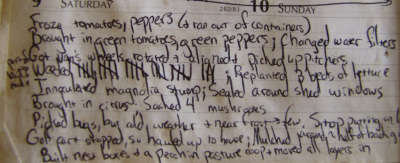

archives for 10/2010

I

don't know if you can call a dish that lacks eggplant ratatouille, but

whatever this is, it's a delicious way to use up a lot of late summer

veggies. The broiled okra completely lacks sliminess and the

other flavors meld together into a feast. Plus, by roasting the

vegetables nearly whole, you retain

most of the vitamins.

I

don't know if you can call a dish that lacks eggplant ratatouille, but

whatever this is, it's a delicious way to use up a lot of late summer

veggies. The broiled okra completely lacks sliminess and the

other flavors meld together into a feast. Plus, by roasting the

vegetables nearly whole, you retain

most of the vitamins.

To make the ratatouille,

first fill your basket with:

- 4 summer squash or zucchini

- 2 large, sweet bell peppers (or several smaller ones)

- 12 to 20 small okra

- 4 large tomatoes (or an equivalent number of tommy-toes)

- 2 large onions

- 6 cloves of garlic

Cut

the squash in half, core the peppers and cut them in halves or

quarters, chop off the okra tops and cut them in half, and cut the

tomatoes in half --- all cuts are long-ways. Peel the onions and

cut them into half inch wedges. Put the garlic through a garlic

press and add it to the rest of the vegetables.

Cut

the squash in half, core the peppers and cut them in halves or

quarters, chop off the okra tops and cut them in half, and cut the

tomatoes in half --- all cuts are long-ways. Peel the onions and

cut them into half inch wedges. Put the garlic through a garlic

press and add it to the rest of the vegetables.

Pour a few tablespoons

of olive oil and a liberal amount of salt and pepper onto the

vegetables and mix them up until all of the surfaces are lightly

oiled. Then lay the vegetables out on cookie sheets, cut sides

down. Broil in the oven until the vegetables are soft and the

skins are very slightly blackened. (About five minutes, less for

the peppers.)

While you're broiling,

rush out into the garden and clip a cup of basil leaves and chop them

into bits. Add a cup and a half of pre-cooked beans and two

tablespoons of balsamic vinegar.

Once the vegetables are

cool enough to handle, chop them into bite-size pieces and throw them

in with the beans and basil. If necessary, add more salt and

pepper.

We ate our ratatouille

over rice, and this recipe looked like it would serve about

eight. Mark rated it 7 out of 10 (probably losing points because

of the presence of beans and lack of meat) while I rated it an

8.5. Definitely worth repeating!

I've often wondered whether I could taste good nutrition, and I'm

tempted to say the answer is yes. The winter squash highest in nutrients is the butternut --- my favorite. The most nutritious fruits are those grown under a bit of nitrogen stress in the bright sun --- again, my favorites. I vastly prefer the flavor of frozen beans

to canned beans and love to saute, steam, and stir fry. Fresh

fruit is in an entirely different (and better) taste category for me

from any cooked or otherwise processed fruit.

I've often wondered whether I could taste good nutrition, and I'm

tempted to say the answer is yes. The winter squash highest in nutrients is the butternut --- my favorite. The most nutritious fruits are those grown under a bit of nitrogen stress in the bright sun --- again, my favorites. I vastly prefer the flavor of frozen beans

to canned beans and love to saute, steam, and stir fry. Fresh

fruit is in an entirely different (and better) taste category for me

from any cooked or otherwise processed fruit.

Although our bodies get

quickly confused when exposed to fake flavors,

colors, and added salts and sugars, we've clearly evolved some basic

cues for determining which foods are nutritious. In some cases,

natural sugars seem to be the key to the rich taste of fresh,

nutritious food --- higher than usual sugar content in a vegetable can

be a cue that the vegetable is also higher in vitamin C. In other

cases, bright colors hint at higher than ordinary vitamin A --- deep

orange peaches have much higher vitamin A content than white peaches.

Some days, I wish I had

a chemical laboratory in my backyard where I

could test the micronutrient levels of every piece of produce grown in

our garden. Is it really twice as high in nutrition compared to

the grocery store version, just as it is twice as high in flavor?

Without more data to back up my gut feeling, I'll have to assume that

anything that tastes good when I eat it raw is also

good

for me.

| This post is part of our Gardening for Maximum Nutrition lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

I've

been making slow progress on sealing up the skylight.

I've

been making slow progress on sealing up the skylight.

Each application yields

better results, but it still has a small leak.

It feels good to learn a new

skill, but I'm ready for this project to be over so we can move on to

the next one.

I broke my own cardinal rule this spring when

I planted parsley in the waterlogged back garden --- no root

crops in heavy clay with high groundwater. I don't think of

parsley as a root crop, but this relative of carrots and parsnips

clearly thinks of itself as a root. Half of my plants achieved

such an advanced state of root rot that the tops literally fell

off. Needless to say, we've only had just enough parsley to make

a weekly batch of soup.

I broke my own cardinal rule this spring when

I planted parsley in the waterlogged back garden --- no root

crops in heavy clay with high groundwater. I don't think of

parsley as a root crop, but this relative of carrots and parsnips

clearly thinks of itself as a root. Half of my plants achieved

such an advanced state of root rot that the tops literally fell

off. Needless to say, we've only had just enough parsley to make

a weekly batch of soup.

So, on a whim, I tossed

a handful of parsley seeds on an empty bed in the loamy side of the

garden near the end of August. Unlike the rest of our fall crops,

the parsley sprouted and grew so thickly that I carefully transplanted

the two-leaved seedlings this week to fill up a couple of nearby

beds. Already, the leaves are almost big enough to eat --- the

plants are growing about twice as fast as the spring parsley that has

had all summer to get established.

The real test will be

the killing frost. Will our baby parsley be big enough to

withstand the cold, or will it die back in a few weeks when

temperatures drop into the twenties? I'm keeping my fingers

crossed that we'll have crisp, sweet parsley through the winter just

like last year.

You can buy a new

power antenna unit for

around 35 bucks, and with a little imagination make it open and close

your chicken coop door.

Rob

from nifty-stuff.com has all the details. He's the guy who put together

the electric

door interlock solution I

posted about last year which only closed the door whereas this power

antenna will open it back up the next morning.

What I like about this design is how easy the installation must be

compared to a few of the other do it yourself automatic chicken coop

door openers out there. You'll need to supply 12 volts DC to the

antenna which can be done with a 20 dollar adapter at Radio Shack. The

next step is to control it with a timer or one of those gadgets that

turns something on when the sun goes down and off when it comes back up.

Edited to add:

After years of research, Mark eventually settled on this automatic chicken door.

You can see

a summary of the best

chicken door alternatives and why he chose this version here.

If you're planning on

automating your coop, don't forget to pick up one of our chicken waterers. They never spill or

fill with poop, and if done right, can only need filling every few days

or weeks!

Since

our sunflower

seed crop was such a

great success, we decided to buy an oil expeller so that we could make

our own cooking oil. An extensive search of the internet shows

only two oil expellers costing less than a thousand bucks. Everett

bought the slightly cheaper and more common model (the Piteba for $139), so we decided to go for the

other to give us a real comparison of the two options.

Since

our sunflower

seed crop was such a

great success, we decided to buy an oil expeller so that we could make

our own cooking oil. An extensive search of the internet shows

only two oil expellers costing less than a thousand bucks. Everett

bought the slightly cheaper and more common model (the Piteba for $139), so we decided to go for the

other to give us a real comparison of the two options.

The

Rajkumar oil expeller comes all the way from India

for $155 (shipping included). My first hint that this wasn't an

ordinary transaction came after I filled in my payment information in

paypal. I got back the following email:

The

Rajkumar oil expeller comes all the way from India

for $155 (shipping included). My first hint that this wasn't an

ordinary transaction came after I filled in my payment information in

paypal. I got back the following email:

We request you to give us your complete postal address with Zip code and telephone no. so that we may dispatch the machine at the earliest from our end. Awaiting for your reply asap.

Thanks & Regards

Naresh Gambhir

(Director)

Since I had just typed in my whole postal address and zipcode, I was a bit confused, but I replied with a repeat of my shipping information, along with the phone number that I didn't see why they would need. Three weeks passed, and I had almost forgotten about our oil expeller when an amazing parcel showed up at the post office.

As you can see from the photos, the box was wrapped in a cloth sack, stitched together and sealed along the sides with red sealing wax! After I teased out the stitches and slid back the bag, I could see that the box was decked out in a bright blue bow. Now, I have to admit that even though I have thoroughly grown out of Christmas presents, I do miss the awe of opening an unknown package. When I was a kid, I spent hours testing the presents under the tree, trying to guess what was inside each one --- generally far more fun than I got out of the presents themselves. Here I was on layer two of my new oil expeller, and I was getting that same Christmas rush.

I untied the bow and ripped off the layer of plastic wrap underneath, then untaped the box. Lifting the lid, a shower of brightly colored paper shreds spilled across the table. Nestled down amid this packaging were about a dozen expeller parts, each one individually wrapped in a thin sheet of foam. I'm getting the impression that the postal service in India isn't very careful, since I had to go through five layers of packaging to get to my expeller (six layers if you count the bow.) From the state of the box, I don't think this packaging was excessive.

I've been researching insect

farming on and off for over a year now since I posted about the possibility of feeding

meal worms to our chickens instead of the laying pellets we buy at the feed store.

We've since settled on a black

soldier fly direction,

but I'm still interested in finding other easy to cultivate bugs. It

turns out there's over 1400 insects that are known to be eaten by

people all over the world.

Some experts predict a world

population of over 9 billion by the year 2050. This prompted the United

Nations to hold a meeting in Thailand back in 2008

on the subject of insect farming and how it might help to mitigate

greenhouse gases and offer a substitute for meat in some countries. A

world congress on the subject is being planned for 2013.

I'll bet a person could

travel to a few Asian countries and learn a thing or two about insect

cultivation with the right translator and an iron stomach.

Once

you start deleting pre-made food from your grocery cart, meals take

longer to prepare. But there are a few tasty and healthy meals

that can be thrown together in fifteen minutes from on-farm

materials. Here's my favorite omelet recipe, one that I consider

a full meal all by itself for about three people.

Once

you start deleting pre-made food from your grocery cart, meals take

longer to prepare. But there are a few tasty and healthy meals

that can be thrown together in fifteen minutes from on-farm

materials. Here's my favorite omelet recipe, one that I consider

a full meal all by itself for about three people.

- 1 medium head of broccoli

- 1 cup of fresh mushrooms

- 6 eggs

- 1 cup of loosely packed Egyptian Onion tops

- a couple of tablespoons of sour cream and onion flavoring powder

Cut the broccoli florets

into bite-size pieces. Then peel the tough skin from the base of

the broccoli stalk and chop the stalk into half inch rounds.

Discard

the mushroom stems. Tear the mushroom caps into bite-size pieces

and add them to a skillet with the broccoli. Pour in as little

oil as possible and saute on high heat until the mushrooms and broccoli

are nearly tender.

Discard

the mushroom stems. Tear the mushroom caps into bite-size pieces

and add them to a skillet with the broccoli. Pour in as little

oil as possible and saute on high heat until the mushrooms and broccoli

are nearly tender.

Break the eggs into a

bowl. Cut the Egyptian Onion tops into one-inch segments and add

them to the eggs. Throw in a couple of tablespoons of sour cream

and onion flavoring powder if you want a really tasty omelet. (I

don't know what's in the stuff, but Daddy gets it for me from his local

Mennonite store and a hint of the powder is enough to turn this omelet

into quite a treat. I'm sure it's not healthy, though....)

Beat the eggs, green

onions, and powder together with a fork and pour it over the broccoli

and mushrooms. I like my omelets to be more like scrambled eggs

with stuff in them rather than the typical omelet consistency, so I

stir continuously for a couple of minutes until the eggs are done.

I haven't included

nutritional information because the sites I've been using to mock up

those analyses don't distinguish between types of mushrooms and think

that my eggs are equivalent to storebought eggs. Suffice it to

say that the omelet has a lot of vitamins and minerals.

As a side note, I led a

hike at the High

Knob Naturalist Rally

this weekend and came home with a huge chunk of Hen

of the Woods mushroom

to try out. I plugged the new mushroom variety into this recipe

and it was just as tasty as the shiitakes and oysters I'd tried in the

past!

It's

been a good year for peppers.

It's

been a good year for peppers.

We're planning for our first

frost of the year sometime this week and decided to harvest everything

that might get nipped.

If it doesn't frost we'll

have lost out on some yumminess, but sometimes it's better to play it

safe.

By

the calendar, we should have at least another week of frost-free

weather, but our forecast mentioned a low of 36 F tonight. Over

the years we've lived here, I've noticed that our temperatures may drop

as much as five degrees below the predicted low so I consider any

forecast less than 37 to be a frost watch.

By

the calendar, we should have at least another week of frost-free

weather, but our forecast mentioned a low of 36 F tonight. Over

the years we've lived here, I've noticed that our temperatures may drop

as much as five degrees below the predicted low so I consider any

forecast less than 37 to be a frost watch.

If I was desperate to

extend our summer harvest, I would run around tossing row covers over

everything. But we've had a good summer, so I'm instead

harvesting any ripe or  ripenable

fruits that would be damaged by freezing, then letting the summer go

gracefully. I stewed up a gallon of ripe tomatoes to go in the

freezer and laid out any with a blush of color to ripen

over the next few weeks.

ripenable

fruits that would be damaged by freezing, then letting the summer go

gracefully. I stewed up a gallon of ripe tomatoes to go in the

freezer and laid out any with a blush of color to ripen

over the next few weeks.

I'm ashamed to say that

I left the really green tomatoes on the vine to rot. I've never

gotten excited about fried green tomatoes, but if you comment with a

more interesting green tomato recipe in the next few hours, I'll rush

out and collect them. Instead of worrying over the last tomatoes,

I'm instead focusing my energy today on harvesting squash,

beans, swiss chard, and the last watermelon.

Huckleberry wants you to

know that even though I closed the windows and put on long johns and

two sweaters, he still thinks it's warm enough to sit outside...for five

minutes at a time.

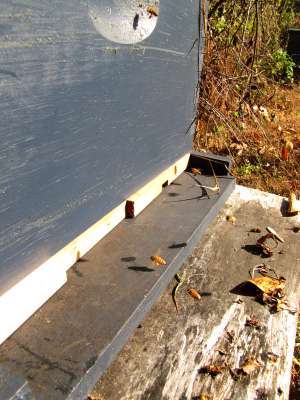

Step 1. Drill twelve 3/4 inch

holes in our new

magnolia stump.

Step 2. Carefully cram mycelium

impregnated cardboard into the holes.

Step 3. Seal up holes with melted bees wax.

Step 4. Don't forget to check

on stump in about 9 months.

We

haven't made much progress on our goal to propagate our own mushroom

spawn because this year's hot summer wasn't conducive to mushroom

fruiting. So when I found wild

oyster mushrooms, I

decided to give propagation a shot even though I knew that spring was

the best time to propagate mushrooms. I cut the stem butts off

all three of our oyster mushroom clusters and sandwiched

them between several layers of pre-soaked, corrugated cardboard.

We

haven't made much progress on our goal to propagate our own mushroom

spawn because this year's hot summer wasn't conducive to mushroom

fruiting. So when I found wild

oyster mushrooms, I

decided to give propagation a shot even though I knew that spring was

the best time to propagate mushrooms. I cut the stem butts off

all three of our oyster mushroom clusters and sandwiched

them between several layers of pre-soaked, corrugated cardboard.

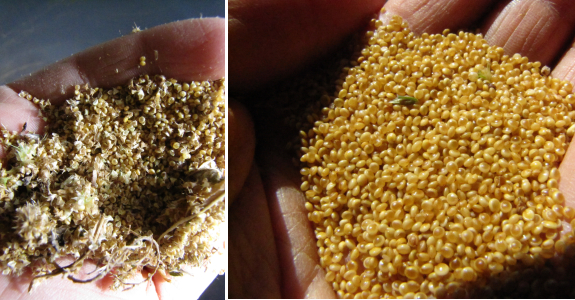

Ten days later, the

mycelium was running! I suspect that if I waited another week, I

would have had a whole bowlful of spawn, but I wanted to get the

mycelium into its final habitat so that it would have some time to get

established before winter. So I tore off all of the  white

spawn, then discarded the un-inoculated cardboard around the

edges. Look at this mass of spawn gluing several sheets of

cardboard together --- that's a healthy fungus!

white

spawn, then discarded the un-inoculated cardboard around the

edges. Look at this mass of spawn gluing several sheets of

cardboard together --- that's a healthy fungus!

Next step was choosing

something to inoculate. In the past, we've had good luck with inoculating logs, but I've been curious about

inoculating

stumps as a way of

hastening decomposition while producing a delicious food. We have

plenty of stumps in our garden area, but most are too old to inoculate

--- wild mushrooms have beat me to it. Luckily, Mark

cut down a magnolia this spring to give me space for forest

pasture trees, and the stump has sprouted a bush of new branches.

I hope the vigor of the tree means that it was able to fight off

invading fungi between April and October, but that the tree has lost

enough life that it won't be able to kill my oyster mushrooms.

Mark

already showed you the inoculation

step --- drilling the holes, stuffing in the spawn, then sealing

each one up with melted beeswax. Our three stem butts turned into

enough spawn to fill up a dozen holes, and I even had one huge stem

butt leftover to bury in the soil at the base of the stump. Maybe

next fall we'll be harvesting completely homegrown oyster mushrooms!

Mark

already showed you the inoculation

step --- drilling the holes, stuffing in the spawn, then sealing

each one up with melted beeswax. Our three stem butts turned into

enough spawn to fill up a dozen holes, and I even had one huge stem

butt leftover to bury in the soil at the base of the stump. Maybe

next fall we'll be harvesting completely homegrown oyster mushrooms!

It

didn't frost last night, but I'm glad we got all the vulnerable citrus

plants moved indoors.

It

didn't frost last night, but I'm glad we got all the vulnerable citrus

plants moved indoors.

They should get more sun in

this new location thanks to the

storage building project from 2009 that turned into an

office/bedroom when we realized how nice it was looking.

I've

been posting all year about our forest pasture experiment over on our Avian Aqua Miser blog. For those of you

haven't been following along over there, the

idea is to create a permaculture system that feeds our chickens with

very little input of storebought food. Our first season of

experimentation was very much a learning experience --- now I know that

even heirloom

broiler breeds have been bred to bulk up quickly on grain, so they look at foraging

about the same way a modern teenager looks at the idea of getting rid

of his TV and Wii. I'm changing my focus now to a forest pasture

system that will keep our

I've

been posting all year about our forest pasture experiment over on our Avian Aqua Miser blog. For those of you

haven't been following along over there, the

idea is to create a permaculture system that feeds our chickens with

very little input of storebought food. Our first season of

experimentation was very much a learning experience --- now I know that

even heirloom

broiler breeds have been bred to bulk up quickly on grain, so they look at foraging

about the same way a modern teenager looks at the idea of getting rid

of his TV and Wii. I'm changing my focus now to a forest pasture

system that will keep our  laying

hens happy and healthy, with the goal of revisiting persnickety meat

birds in the future.

laying

hens happy and healthy, with the goal of revisiting persnickety meat

birds in the future.

With the broilers in the

freezer, our forest pasture experiment started making progress.

In late August, I realized that our

two pastured chickens were so happy on their diet of kitchen scraps and

wild edibles that they didn't want any storebought grain. For six weeks now,

I've only given them a cup of feed every couple of weeks, on days when

I felt like our kitchen scraps weren't quite up to snuff.

Meanwhile, I seeded

the fallow paddock with buckwheat and shelling beans, which are now mature.

With our coop remodelled to accommodate laying hens, we turned our four

prime layers into the fallow paddock, expecting them to gorge on the

high quality seeds. Instead, they focused their energy on

nightshade berries, tender young chickweed leaves, calcium-rich snails,

and bugs found by scratching through the old compost pile.

In

fact, now that I could look at our tractored chickens and pastured

chickens side by side, I was shocked to realize that the former were

not the epitome of avian health I'd thought they were. The

pastured chickens have brilliantly red combs --- a sign of good health

--- while our confined birds' skin is a much paler shade. Keep in

mind that our tractored birds have as much grass as they can eat, along

with occassional bugs that hop through their tractor, but that they get

the majority of their nutrition from the corn and soybeans in their

laying pellets. Clearly, a grain-based diet is no better for them

than

it is for me.

In

fact, now that I could look at our tractored chickens and pastured

chickens side by side, I was shocked to realize that the former were

not the epitome of avian health I'd thought they were. The

pastured chickens have brilliantly red combs --- a sign of good health

--- while our confined birds' skin is a much paler shade. Keep in

mind that our tractored birds have as much grass as they can eat, along

with occassional bugs that hop through their tractor, but that they get

the majority of their nutrition from the corn and soybeans in their

laying pellets. Clearly, a grain-based diet is no better for them

than

it is for me.

With the garden's

exuberance winding down, I'm sure I'll have to continue feeding our

laying hens grain through the winter, but my long term goal is to come

up with a system that deletes the grain entirely. Two more

paddocks are on the horizon, which will allow us to rotate our flock

frequently enough to give them plenty of forage during the growing

season. Our Illinois

Ever-bearing Mulberry

and Nanking

Cherries should be

reaching full productivity in a few years, which will go a long way

toward feeding the flock during the summer months. Buying less

and less processed food in the grocery store will also mean more and

more food byproducts to give the chickens year round --- for example,

our oil

expeller will

produce high protein seed cakes perfect for chicken feed. We'll

continue to work on insect

farming as a

supplemental food option, and will keep you updated as our forest

pasture experiment progresses.

These windows were salvaged

from an old high school by a neighbor. He kept them in storage for

years with the intention of building a green house, but eventually

decided to drop the indoor garden dream and gave several of them to us.

Thank you Bill Boyd.

It feels good to put salvaged

material back to work, but I wonder how much heat we'll lose compared

to putting in double pane windows? The plan is to make some sort of

indoor panel with attached insulation that can be inserted in place to

keep in more heat at night.

I'm thinking some of that

thin plywood with a layer or two of Reflectix might work.

Our

freezer is now officially full. I like to stack my

produce in careful columns --- all of the squash in one

row, all of the greens in another --- but over the last week, I've had

to overcome my compulsive arranging and fit in food willy-nilly.

Not counting sauces, chickens, and fruit, we've got over 28 gallons of

vegetables in our frozen larder!

Our

freezer is now officially full. I like to stack my

produce in careful columns --- all of the squash in one

row, all of the greens in another --- but over the last week, I've had

to overcome my compulsive arranging and fit in food willy-nilly.

Not counting sauces, chickens, and fruit, we've got over 28 gallons of

vegetables in our frozen larder!

It's a good thing the

freezer is full because we're totally out of freezing containers.

We buy them in bulk on our visits to Mark's family in Ohio, and I guess

I didn't expect such a bumper garden crop this year. Just as the

freezer started bulging at the gills, we rounded up the stray

containers that had been pressed into service holding screws or chicken nipples

and put them back into the food chain. Even then, we ran out of

containers just a few shy of filling every last gap in the freezer.

With no more space in

the freezer and nothing to freeze the excess in, we're now just eating

out of the garden. I feel like I've been given a gift of time ---

a whole free day a week that I used to spend processing the bounty.

I should probably have researched the batteries in this old solar-powered house before I installed a charge controller. I had assumed that the 24 6-volt batteries in the house's battery bay were standard lead-acid deep cycle batteries. It wasn't until I stumbled over a receipt from 1997 that I learned that the batteries are really NiCads. Specifically Saft model STM5-180.

Thirty of these were purchased in 1997 from

TVA in Chatanooga,

for $350 total. An amazing price, since a single deep cycle battery is

in that ballpark, new. These batteries were used, they had been in a "bus" --

perhaps it was a

1995 Chrysler TEVan, or

maybe one of the pilot electric buses running there in the late 90's.

They were probably not in

this '79 VW TVA Bus.

All mentions of these batteries I can find involve electric vehicles --

it's unusual for them to be used to power a house.

Thirty of these were purchased in 1997 from

TVA in Chatanooga,

for $350 total. An amazing price, since a single deep cycle battery is

in that ballpark, new. These batteries were used, they had been in a "bus" --

perhaps it was a

1995 Chrysler TEVan, or

maybe one of the pilot electric buses running there in the late 90's.

They were probably not in

this '79 VW TVA Bus.

All mentions of these batteries I can find involve electric vehicles --

it's unusual for them to be used to power a house.

Being vented NiCads probably accounts for these batteries' long useful life -- surely at least 15 years. Still, with only twenty-four good ones left, they are probably toward the end of their lifespan and need to be taken care of in order to last.

Once I realized they were NiCads, I knew the charge controller was charging them wrong. NiCads like to be charged at a higher voltage than the 13 or so volts used for lead acid. I would have liked to charge them at 16 volts, but that would feed back through the house wiring, and could fry 12 volt stuff. Checking ratings, 15 volts seemed the highest voltage I could risk.

Coming back a week later, I found the batteries charged up to 13.4 volts. And they are now working great. Through several cloudy days, we had all the power we needed. And when the sun was out fully, I sometimes saw the solar panels charging the batteries at 125 watts -- fully half of the panels' rated capacity, and much better than before. The batteries start each evening at 13.4 volts, and only drop to 13.3 by morning. We started using electric lights more, and then just leaving them on all evening, and the freedombox online all night, and the batteries remained at the magic 13.3 in the morning. This is because NiCad batteries have a near-constant voltage until they are perhaps 30% discharged. In other words, I had been charging them less than half full before.

I have figured out how to combine the two banks the batteries are in into one large bank, and once I get the cables to do that, I hope to have battery capacity to get through up to a week of solid clouds in midwinter.

|

When

Mark

came home with 18 bales of straw, I thought he was being a

little decadent. Who needs 18 bales of straw? Me, clearly.

When

Mark

came home with 18 bales of straw, I thought he was being a

little decadent. Who needs 18 bales of straw? Me, clearly.

First, I just mulched

the garlic

beds as I put them

in, but then I decided to go ahead and mulch around everything

else. After a careful weeding job, I put straw around the edges

of any of the cover crops and winter crops which hadn't quite covered

their beds.

My new goal is to have

every bit of the garden either under mulch or cover crop

for the winter. I know from experience that every little bit of

energy you sink into putting the garden to bed in the winter is repaid

threefold by less work in the spring. Autumn

leaves did a pretty

good job last year, but since then I've read that a high

carbon mulch promotes a higher fungal to bacterial ratio than most

garden plants enjoy,

so straw seems to make more sense as a vegetable mulch.

About

halfway through my mulch campaign, the unimaginable happened --- I ran

out of straw. "Mark, I only have four bales left," I said sadly,

and Mark rolled his eyes, refrained from saying "I told you so", and

instead sent me and my father (currently visiting for the weekend) out

to the feed store for one more truckload. I feel even more

decadent now, but I'm looking forward to an even more healthy garden in

2011.

About

halfway through my mulch campaign, the unimaginable happened --- I ran

out of straw. "Mark, I only have four bales left," I said sadly,

and Mark rolled his eyes, refrained from saying "I told you so", and

instead sent me and my father (currently visiting for the weekend) out

to the feed store for one more truckload. I feel even more

decadent now, but I'm looking forward to an even more healthy garden in

2011.

Our broody hen has

decided that this outdoor nest is a more proper home for her 11 eggs.

Our broody hen has

decided that this outdoor nest is a more proper home for her 11 eggs.

That's what I get for

procrastinating on building those coop nest boxes.

Maybe she'll reconsider once

I make something more cozy and higher up?

I

dragged Daddy to the fruit stand on Friday, where we peered in the

cooler at two big baskets of chestnuts. "Nice looking chesnuts,"

I said to the clerk, making conversation. "They're buggy ---

we're going to throw them out this evening," he replied.

I

dragged Daddy to the fruit stand on Friday, where we peered in the

cooler at two big baskets of chestnuts. "Nice looking chesnuts,"

I said to the clerk, making conversation. "They're buggy ---

we're going to throw them out this evening," he replied.

My biomass detectors

perked right up. Five minutes later, I had a bushel of wormy

chestnuts in my possession, hoping that I'll be able to find a way to

feed them to the chickens. I know my flock won't be able to peck

their way through the tough skins, and I don't want to crack each one

open individually. Does anyone have any ideas for busting a bunch

of wormy chestnuts far enough out of their shells so that a chicken

beak can get to them?

The collapsible

lawn and leaf bag has seen better days.

The collapsible

lawn and leaf bag has seen better days.

We should have known better

and stored it in the barn when the season was over.

I'm afraid too much sunlight

exposure has weakened the tarp material resulting in a few fatal rips

that duct tape can't fix.

While

poking around the fruit stand in search of my favorite apples, I

stumbled across what was clearly a dried bean shelling station.

Since I'm just getting into growing my own dried

beans, I was

intrigued to see how a medium-scale operation like this cleans their

beans without mechanical equipment.

While

poking around the fruit stand in search of my favorite apples, I

stumbled across what was clearly a dried bean shelling station.

Since I'm just getting into growing my own dried

beans, I was

intrigued to see how a medium-scale operation like this cleans their

beans without mechanical equipment.

As best I can tell, the

beans are first hand-shelled, then this setup is used to separate the

chaff, stones, and bad beans from the good beans. A wooden frame

with a relatively fine mesh stapled to the bottom sits on top  of a table topped by crossed

rebars. I can just imagine tossing all of my shelled beans into

the frame, shaking it vigorously, and watching bits of chaff and small,

malformed beans drop out the bottom.

of a table topped by crossed

rebars. I can just imagine tossing all of my shelled beans into

the frame, shaking it vigorously, and watching bits of chaff and small,

malformed beans drop out the bottom.

I'm sure it's not

cost-effective to sell your homegrown beans after putting so much

effort into their processing, but I don't mind putting in extra time to

feed my own family more nutritious food. As I learned when my

father came to visit, shelling beans is a great thing to do with your

hands while visiting. I now have a solid cup of urd beans just waiting to be sprouted

into about a gallon of bean sprouts.

My

mom (Adrianne) has a beautiful and dynamic garden in her small city

backyard. It's very much like a cottage

garden, with flowers

and vegetables tucked together in arrangements that are not only

visually appealing, but also quite productive.

My

mom (Adrianne) has a beautiful and dynamic garden in her small city

backyard. It's very much like a cottage

garden, with flowers

and vegetables tucked together in arrangements that are not only

visually appealing, but also quite productive.

As a special treat, I've

talked her into making a few guest posts this week for a lunchtime

series. I hope you enjoy this glimpse into an urban homestead!

| This post is part of our Urban Homesteading lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

When we introduced our chicken

tractor girls to the new pasture area they quickly found a back door

that had been carved out by Lucy back before she discovered the power

of a K9

fence unit.

When we introduced our chicken

tractor girls to the new pasture area they quickly found a back door

that had been carved out by Lucy back before she discovered the power

of a K9

fence unit.

It makes me wonder why the broody hen and

the grown up

new chick never ventured out for a peek. Maybe they just weren't

interested in anything on the other side?

The

assembly instructions that came with our Rajkumar oil expeller left a

lot to be desired, but I figured it out pretty easily by looking at the

picture below, snagged from their website.

The

assembly instructions that came with our Rajkumar oil expeller left a

lot to be desired, but I figured it out pretty easily by looking at the

picture below, snagged from their website.

To be fair, it's

possible that the hand-lettered CD that came with the expeller might

have included more pictorial instructions, but I couldn't open the

files on my computer. In case you follow my lead and buy the

Rajkumar expeller, I've included step by step assembly instructions

below.

Your expeller will come

partially assembled, but you have to remove the expeller screw and wash

it, along with the rest of the expeller, prior to the first use.

Once the parts are  clean

and dry, slip one of the two included washers over the handle end of

the expeller screw and grease it with cooking oil, as shown above on

the right. The instructions note "This washer is exposed to very

high pressure and should always be well greased."

clean

and dry, slip one of the two included washers over the handle end of

the expeller screw and grease it with cooking oil, as shown above on

the right. The instructions note "This washer is exposed to very

high pressure and should always be well greased."

Next, slide the expeller

screw into the press cage (the main part of the expeller) until the

smooth end pops out the other side.

The

handle slides right over the end of the expeller screw --- just be sure

to line up the holes. The longest bolt in the kit seems to be the

only one that fits to put these two parts together.

The

handle slides right over the end of the expeller screw --- just be sure

to line up the holes. The longest bolt in the kit seems to be the

only one that fits to put these two parts together.

The

cap screws easily onto the other end of the press cage. Depending

on the type of seed you will be processing, you may also need to screw

the adjustment bolt into the cap. We left the bolt off since

we'll be expelling sunflower seeds first.

The

cap screws easily onto the other end of the press cage. Depending

on the type of seed you will be processing, you may also need to screw

the adjustment bolt into the cap. We left the bolt off since

we'll be expelling sunflower seeds first.

Those of you following

along at home may have realized by now that, up until this point, the

Rajkumar expeller is completely identical to the Piteba model, except

for the bigger stand bolted to the back. A  close

look at both websites makes me pretty sure that the two brands are in

fact identical, but that the Rajkumar expeller has added in the bigger

stand and three handy funnels. These funnels are made of much

less strong material than the angle iron and heavy pipes that make up

the main body of the expeller, but I'm sure they will hold up well

under the light use they'll be put to.

close

look at both websites makes me pretty sure that the two brands are in

fact identical, but that the Rajkumar expeller has added in the bigger

stand and three handy funnels. These funnels are made of much

less strong material than the angle iron and heavy pipes that make up

the main body of the expeller, but I'm sure they will hold up well

under the light use they'll be put to.

The longest funnel

(shown above) is meant to channel the oil away from the expeller so

that you can collect your product in a larger jar than you could with

the Piteba expeller. The oil funnel is attached with a single

screw threaded through the back of the expeller.

If

you're smarter than I was, you'll rubber-band your bottle of lamp oil

to the rounded part of the expeller before moving on to the next step,

but I didn't have any lamp oil on hand, so I went ahead and screwed the

seed cake funnel to the front of the expeller with the other small

screw. I'll have to remove this funnel and attach the "lamp"

before operating the expeller.

If

you're smarter than I was, you'll rubber-band your bottle of lamp oil

to the rounded part of the expeller before moving on to the next step,

but I didn't have any lamp oil on hand, so I went ahead and screwed the

seed cake funnel to the front of the expeller with the other small

screw. I'll have to remove this funnel and attach the "lamp"

before operating the expeller.

To complete assembly of the oil expeller, I

popped the round funnel on the top, having to bend the base a bit so

that it slid on smoothly. This last photo shows the completely

assembled expeller, with the lamp bottle in place to show its location.

To complete assembly of the oil expeller, I

popped the round funnel on the top, having to bend the base a bit so

that it slid on smoothly. This last photo shows the completely

assembled expeller, with the lamp bottle in place to show its location.

Despite this long post,

assembling the Rajkumar oil expeller only took about 15 minutes, and

that includes a bit of head-scratching. The kit came with

absolutely everything you might need, too, including a tiny screwdriver

and wrench. I would say that assembly is within the reach of even

the beginner DIYer.

I've

had tansy ever since my mother brought a start to me from South

Weymouth, Massachusetts, probably from her own yard, and probably, too,

originally from her sister, Ruth

Tirrell. My

mother

would have little

sprigs of the tansy flower mixed in with barberry bush sprigs, in a

vase

on her windowsill over the sink. These little "button" seedheads

stay

yellow for ages, and keep their bitter, aromatic smell even longer.

I've

had tansy ever since my mother brought a start to me from South

Weymouth, Massachusetts, probably from her own yard, and probably, too,

originally from her sister, Ruth

Tirrell. My

mother

would have little

sprigs of the tansy flower mixed in with barberry bush sprigs, in a

vase

on her windowsill over the sink. These little "button" seedheads

stay

yellow for ages, and keep their bitter, aromatic smell even longer.

The

reason for tansy was to keep ants away. In my mother's kitchen

this never

seemed to work! But I guess she kept tansy as a comforting

decoration,

anyway!

I've looked up a tansy

cookie

recipe, in the Rodales

Herb

Book, ed. by

Williamk Huilton, 1974: Beat 1/2 c. honey and 1/2 c. butter. Add

1 egg,

then 2 c. whole wheat flour, 1/4 tsp. baking soda, 1/4 tsp. salt, 1

tsp.vanilla and

1 1/2 tsp. tansy (probably dried leaves), plus 1 tbsp. yoghurt.

Roll out to

1/8 in. thick, cut into rounds, sprinkle with more tansy and bake at

375

for 10 min.

Because it is a "bitter

herb"

the cookies were eaten at Easter, and the

dried leaves were eaten at Passover. The seeds can be eaten

as a worm

expellent. There are other medicinal uses, of the tea brewed from

the

leaves: for eye imflammtion and styes, and in compresses  for

varicose

veins!

for

varicose

veins!

Tansy is supposed to

deter

mosquitoes, and squash bugs, besides ants.

Some say it therefore attracts aphids. Some say it deters

cucumber

beetles, some say it attracts them. I have my tansy tangled up

with a

volunteer blackberry vine, and have never had Japanese beetles

there. Some

others plant tansy under fruit trees.

This is a ferny perennial

that

is started best from small starts, not

seeds. Mine has grown to 6 feet, taller than the usual 4.

Worth growing

for its distinctive smell and flowers.

| This post is part of our Urban Homesteading lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I installed our 3rd rotisserie

motor deer deterrent in the garden today.

This new design is much more

solid and dependable.

I'm offering 2 free Walden Effect T-shirts to anyone out there industrious enough to build one of these and report back on it with a few pictures.

We haven't seen any deer

damage in our garden in a couple of months, and even then their

depredations were minimal. Compare that to years past when our

entire growing area was repeatedly defoliated by the hooved fiends, and

you'll understand why I think Mark is a genius.

We haven't seen any deer

damage in our garden in a couple of months, and even then their

depredations were minimal. Compare that to years past when our

entire growing area was repeatedly defoliated by the hooved fiends, and

you'll understand why I think Mark is a genius.

Last year, I was

thrilled by the deer deterrents Mark made using old

display motors, but those motors burnt out quickly and left holes in

our defenses. His most recent incarnation uses rotisserie motors,

which seem more hard core and also go a bit more slowly so that that

the noise is harder for deer to acclimate to. To put the icing on

the cake, the golf balls now hit brass cups, which makes the noise more

pleasing to human ears --- very similar to a wind chime.

To be fair, it's really

tough to find the true cause of our current absence of deer because

every year is a bit different. Maybe wild foods are especially

abundant this year, but we don't seem to be having a mast year on our property. And

the deer pressure is still quite strong --- a neighbor told me that

he'd recently cruised down our two and a half mile road and counted

fifty deer. Granted, I did take a potshot over the head of a deer

a few months ago when he found a gap in our deterrents and ate my

beans, but the efficacy of scare tactics like that has been short term

in the past. In previous years, I've lost the entire fall garden

in one fell swoop to the deer.

We're hoping to have

some guinea pigs test out deer deterrents around their own garden to

give us a bit more data --- Mark

has offered two free t-shirts to anyone who sends us some photos (and

feedback) on their deterrents in action. Your first step

should be to read our instructions to make

your homemade deer deterrent. Those instructions

use a motor that we no longer recommend, but it should be simple to add

in the rotisserie motor and take out the drill, transformer, and

resistor using the information Mark has been posting on his deer deterrent blog. You can leave a

comment here or there if you have trouble and we'll point you in the

right direction. I estimate that your total cost to produce a

deterrent (assuming you buy everything new) will be about $30...or

considerably less if you do a bit of scavenging for components.

I know that we have a

lot of handy readers, so I'm looking forward to seeing what you come up

with. Erich, Zimmy, consider yourselves challenged.

| This post is part of our Urban Homesteading lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I installed this outdoor nestbox for the more discriminating hens of

our flock.

There still seems to be some

confusion when it comes to finding the right roost for the night.

Maybe this extra nest will

help to smooth out some ruffled feathers?

Cover

crops take almost no effort, but you do need to keep an eye on them and

make sure they don't go to seed. I thought that buckwheat planted

on August 24 would be killed by the first frost just as it reached peak

maturity, but we dodged the early frost bullet last week, and now our

buckwheat is starting to develop young fruits.

Cover

crops take almost no effort, but you do need to keep an eye on them and

make sure they don't go to seed. I thought that buckwheat planted

on August 24 would be killed by the first frost just as it reached peak

maturity, but we dodged the early frost bullet last week, and now our

buckwheat is starting to develop young fruits.

I mowed down

our first round of buckwheat, but I wasn't very happy

with the results ---  buckwheat

bits flew everywhere, and some plants got mashed down and then

regrew. This time, I decided to try out the electric hedge

trimmer Mark got at a yard sale for $10.

buckwheat

bits flew everywhere, and some plants got mashed down and then

regrew. This time, I decided to try out the electric hedge

trimmer Mark got at a yard sale for $10.

As you can see, the

sickle-type mowing blade made short work of our succulent buckwheat

stems. I slid the hedge trimmer through the buckwheat about an

inch above the ground and was done cutting in about a minute. A

minute after that, I'd finished tossing the few stems that slid off the

bed back on top of the growing area.

The buckwheat worked as

advertised in our loamy upper garden --- maturity in precisely six

weeks. Of course, the real test will be the quantity of dried

organic matter we get, compared to the amount of organic matter that

results from our slightly shorter but tougher oat stems.

No matter which cover

crops win my long term attention, I can tell that the electric hedge

trimmer has a future in our grain experiments.

Two

different types of pole beans are gradually stopping blooming in my

garden now. Both I got from Deni and Tom Peterson at a seed

exchange this

winter. Both I've grown on bamboo "tipis", with the Hidasa Shield

Figure

Bean, from the Plains, further away from the mulberry trees that

shade that part of the garden, which was a bad tomato

blight spot last

year.

Two

different types of pole beans are gradually stopping blooming in my

garden now. Both I got from Deni and Tom Peterson at a seed

exchange this

winter. Both I've grown on bamboo "tipis", with the Hidasa Shield

Figure

Bean, from the Plains, further away from the mulberry trees that

shade that part of the garden, which was a bad tomato

blight spot last

year.

The Hidasa Shield Figure

Beans are rather flat and wide, a light green, and sturdy.

The dried beans are white, with a brown "shield" which also has a white

center in it. According to the Petersons (at

tpeterson@asdevelp.org) they

were grown in Buffalo Bird Woman's Garden, and were selected to Slow

Food's "Ark of Taste." They grew really well and traveled onto a

pea fence

that was next to their poles.

The

other type, with purple blooms, is the Cherokee Trail of Tears, that

also has a purplish bean that turns green when cooked. Or has the

black

seeds when dried. This has been grown since the late 1830s.

It did well in

partial shade, climbing on poles that slanted back toward the mulberry

branches, so that I, too, had to climb up on a ladder to pick them!

The

other type, with purple blooms, is the Cherokee Trail of Tears, that

also has a purplish bean that turns green when cooked. Or has the

black

seeds when dried. This has been grown since the late 1830s.

It did well in

partial shade, climbing on poles that slanted back toward the mulberry

branches, so that I, too, had to climb up on a ladder to pick them!

The only drawback to

these beans is their strings, with the Hidatsa bean

pods being quite tough to break, while the Cherokee are almost

stringless, with an infinitesimal string, almost as tender as a corn

silk!

No bugs at all on these

beans, compared to Blue Lake, I also grew.

Conventional "half-runners" had much more persistent strings, too.

To grow these beans is to

touch history, in a spiritual way.

| This post is part of our Urban Homesteading lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

One problem that's happened a

few times with the golf cart is battery gunk eating its way through the

battery cable connectors.

You can find a replacement

cable at most auto parts stores somewhere in the battery section, but

these copper connectors will work as a replacement end at less than half

the cost.

I

am a chocoholic, so I was thrilled when I realized you can substitute

cocoa for flour in baked goods and end up with the same

fluffiness and texture as in the original, but with double the

chocolate

content. My first trial was a chocolate

crust for our butternut pie, then I created this dark

chocolate cocoa muffin recipe based on our favorite chocolate cake recipe.

I

am a chocoholic, so I was thrilled when I realized you can substitute

cocoa for flour in baked goods and end up with the same

fluffiness and texture as in the original, but with double the

chocolate

content. My first trial was a chocolate

crust for our butternut pie, then I created this dark

chocolate cocoa muffin recipe based on our favorite chocolate cake recipe.

Mark and I agree that

this is every bit as good as the world class

chocolate muffins we enjoyed on our cruise a year ago, and the muffins

are unbelievably easy to throw together. If you currently fulfill

your chocolate cravings with cake mix or pre-made cakes from the

grocery store, you can save a bundle (and delete some of the bad

ingredients) by using this recipe instead.

- 1 c. sugar

- 1/3 c. plus 1/4 c. white flour

- 2/3 c. cocoa

- 3/4 tsp. baking soda

- 3/4 tsp. baking powder

- 1/2 tsp. salt

- 2 eggs

- 1/2 c. milk powder, dissolved in water to yield 1/2 c. of dense

milk

- 1/4 c. peanut oil

- 1 tsp. vanilla extract

- 1/3 c. boiling water

Preheat the oven to 350

F. Grease two medium cookie tins --- this recipe will make 12

muffins.

Stir together the sugar,

flour, cocoa, baking powder, baking soda and salt in large bowl.

If you're adventurous, feel free to increase or decrease the flour and

cocoa quantities until you find just the right chocolate point for you

--- the sum of the two quantities should equal 1.25 cups.

Add eggs, dense milk, oil and vanilla. Beat on medium speed with

the mixer

for two minutes while bringing some water to a boil.

Stir in the boiling

water. Pour batter into muffin tins and bake until done. (I

can't tell you an exact baking time because the numbers have rubbed off

my oven temperature dial and I'm not certain I was baking at exactly

350.)

I've

tried several times adding chocolate chips to these muffins, but try as

I might, the chips drop to the bottom. I even whirred the chips

in the blender to make them smaller and still ended up with

chips-on-the-bottom. If anyone can figure out a way to make my

chocolate chips stay suspended in the thin batter, I'd be forever

grateful!

This

plastic milk carton was easy to attach to the wall with several dry

wall screws.

This

plastic milk carton was easy to attach to the wall with several dry

wall screws.

Installing it near a hole

makes egg access easy without entering the coop.

What you don't see is a roost

at the half way point to make getting up there easier for the girls.

What

happens when you merge three chicken flocks together? Lots of

excitement!

What

happens when you merge three chicken flocks together? Lots of

excitement!

To refresh your memory,

the forest pasture had been home to our broody

white cochin and her foster son for a couple of months while our three

oldest hens lived together in one tractor and one younger hen lived

alone in another tractor. The youngest hen's sister currently

lives in another tractor until we find time to turn her into sausage

--- she developed

some sort of egg-laying problem that can't be solved and she

isn't worth feeding through the winter.

I rushed the move to

pasture a bit because I felt bad about the hen living all by herself in

a tractor, but at first our loner seemed to have been better off in

solitary confinement. The mother hen and her son teamed up to go

after the newcomers until all four lived in fear (and were cut off from

the food.) While the three oldsters had each other for moral

support, our youngest hen hovered on the periphery and went so far as

to fly out of the pasture in her efforts to escape harassment.

That was the status quo

for a few days, until I decided to open up the other coop door to let

the chickens use both pastures. Our old hens are about ten times

smarter than the others, so they figured out right away that they could

pop into the coop on one end and out the other end into a tyrant-free

paradise. I started feeding the three wise hens in their own

pasture, and the other three birds in the broody hen's pasture.

A

week after flock merger, our poor loner was out of the pasture again,

and this time I decided to pop her back into the wise hens' pasture

rather the other one. This small decision seems to have changed

the entire flock dynamic --- a couple of hours later, I discovered the

rooster in the wise hens' pasture, lording over four hens who all got

along just fine. Maybe he knew how to change pastures all along,

but saw no reason to follow along after middle-aged biddies?

A

week after flock merger, our poor loner was out of the pasture again,

and this time I decided to pop her back into the wise hens' pasture

rather the other one. This small decision seems to have changed

the entire flock dynamic --- a couple of hours later, I discovered the

rooster in the wise hens' pasture, lording over four hens who all got

along just fine. Maybe he knew how to change pastures all along,

but saw no reason to follow along after middle-aged biddies?

Our rooster's regard

seems to have flip-flocked our youngster's status from loner to

flockmate. The wise hens used to peck at her when she got too

close, but under the rooster's reign, the pasture was full of serenely

scratching hens.

Meanwhile, the mean

white cochin hardly seemed to notice that her son had defected.

Will she eventually make her way into the popular pasture? Will

she maintain her rank at the top of the pecking order once I merge all

of the chickens back into one pasture to plant winter wheat in the

other?

I can't imagine why I

would need to watch TV with so much drama right in my backyard.

I've discovered that a good

cloth tow strap is a great addition to the homesteading tool box.

We used ours recently to tow

the golf cart back to the trailer when it had a problem.

It's also handy when winching

out something that's stuck in the mud.

Even

though it didn't frost a week and a half ago, it turns out that harvesting

all of the blushing tomatoes was a good move. Our

vines are laden with fruits of all ages, and it seemed like when I

picked all of the slightly ripe fruit, the remaining green fruit

started ripening faster.

Even

though it didn't frost a week and a half ago, it turns out that harvesting

all of the blushing tomatoes was a good move. Our

vines are laden with fruits of all ages, and it seemed like when I

picked all of the slightly ripe fruit, the remaining green fruit

started ripening faster.

I decided to go ahead

and repeat the maneuver this week in hopes of getting even more

ripenable fruits off our vines before the frost. We now have a

three story hanging basket completely full of ripening tomatoes and

peppers, along with another basket of greener tomatoes and a collander

of green peppers. There are still two weeks' worth of green

tomatoes out in the garden, if by chance the frost holds out that long.

Poor Daddy had to put up

with peppers in every meal while he was visiting. Roast peppers,

peppers on salad, ratatouille, peppers in fajitas...I

suspect he won't be eating another pepper anytime soon.

The current plan is to move the 5

gallon bucket waterer from the side of this tree to inside

the pasture coop.

The current plan is to move the 5

gallon bucket waterer from the side of this tree to inside

the pasture coop.

I've got a few ideas

involving the Ice and Easy heater coupled

with some insulation that might prevent our chicken water from freezing

this winter.

Mark

and I took a quick trip up north this past weekend to experience our

first real sailing lesson, to hang out with old buddies, and then to

enjoy a beautiful wedding. (Congratulations, Kira and Erskin!)

Mark

and I took a quick trip up north this past weekend to experience our

first real sailing lesson, to hang out with old buddies, and then to

enjoy a beautiful wedding. (Congratulations, Kira and Erskin!)

We thoroughly enjoyed

the decadence of eating out, luxuriating in a hot bath, and having no

chores. But after just two days, we were sick of the big

city. Despite seeking out vegetables on every menu and snacking

on a big bag of fruit stand apples lugged from home, I was starting to

feel malnourished without my farm fresh produce, greenery, and fresh

air.

Back home, we see the

frost came calling while we were gone. I always have mixed

feelings about the first frost. Seeing the blackened leaves on

the tomatoes, okra, squash,  and

basil, I know that the bounty of summer is truly over. On the

other hand, summer weeds have blackened too, so the first frost gives

me an inkling of the serenity of winter. I know that in just a

few months I will be aching for an excuse to push my hands into the

soil again.

and

basil, I know that the bounty of summer is truly over. On the

other hand, summer weeds have blackened too, so the first frost gives

me an inkling of the serenity of winter. I know that in just a

few months I will be aching for an excuse to push my hands into the

soil again.

Of course, the first

frost brings its own bounty. Oyster mushroom logs that sat

dormant all summer have sprung into life! Good thing I found a

small stack of freezer containers in the barn while preparing for our

trip. I guess I could squeeze a few more quarts into our

jam-packed freezer.

I'm not sure what took the

bungee cord industry so long to wise up to the innovation of a

carabiner instead of a hook, but it sure makes overloading the golf

cart much easier compared to more traditional bungee cords.

We

stayed at Village

Inn in Annapolis, MD,

during last weekend's trip

north. Since this is me we're talking about, you probably won't

be terribly surprised that I learned about a new garden vegetable in

the process, right?

We

stayed at Village

Inn in Annapolis, MD,

during last weekend's trip

north. Since this is me we're talking about, you probably won't

be terribly surprised that I learned about a new garden vegetable in

the process, right?

The motel is run by an

Indian family, and they were growing a squash

I'd never seen before. The vine was exuberant, running out across

the lawn in every direction just like any other squash, but when I

walked closer, I saw that the fruits were fuzzy! The crinkly

white flowers were unique too, and I was positive I'd never seen such a

thing before.

I bearded one of the

proprietors in the office and picked his brain

about this vegetable, which turned out to be an Indian Long

Squash. He told me that his family eats the long squash like a

vegetable (presumably like a summer squash?), cooks it into sweets

(like pumpkin pie?), and even  uses it to lower their

cholesterol.

I was dying for more information, but he had to answer the phone, and

we had a sailing lesson starting up any minute.

uses it to lower their

cholesterol.

I was dying for more information, but he had to answer the phone, and

we had a sailing lesson starting up any minute.

As I walked out the

door, though, the nice gentleman called after

me. "No chemicals!" he exclaimed --- just making sure I knew that

his beautiful garden was organic. I wouldn't be exaggerating if I

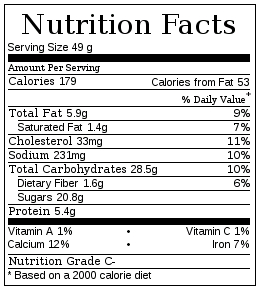

told you this stay in a budget motel was the best hotel experience of

my life.

Anna and I saw this huge pumpkin on our

trip up north last week at Burke's fruit stand outside of Abingdon.

It's by far the biggest one

I've seen this year.

The sign says it's not for

sale, but if I had to guess I would say it might go for 40 or 50

bucks...maybe more in a bigger city.

If someone had asked me

yesterday how long wood chips need to age before they can be used as

mulch, I would have said, "You should probably wait two years.

And even then there could be pockets of chips too young to mulch

with. Wait until your chips have turned black."

Today,

I'll tell you something completely different. With a flock of

broilers scratching through and fertilizing fresh wood

chips, and with wild

fungi colonizing the substrate, your wood chips could be perfect mulch

in just 6 months. And black isn't the prime color --- white

is. The best mulch will be held together by huge masses of

mycelium, bringing the fungi to

bacteria ratio to

the point that trees love.

Today,

I'll tell you something completely different. With a flock of

broilers scratching through and fertilizing fresh wood

chips, and with wild

fungi colonizing the substrate, your wood chips could be perfect mulch

in just 6 months. And black isn't the prime color --- white

is. The best mulch will be held together by huge masses of

mycelium, bringing the fungi to

bacteria ratio to

the point that trees love.

As I shoveled the world

class mulch out of the forest pasture, I had to keep my wits about me

so that I didn't cut off any hen toes. My wise old hens knew that

worms and grubs like to hide out under mulch, and they also knew that

the hen closest to the shovel always gets the prize.

The chickens feed the

wood chips, the wood chips feed the orchard, and the grubs feed the

chickens. I love it when permaculture systems fit so well

together.

Adding a couple of ladder

hooks on the tail gate of the golf

cart dump box makes

hauling over sized pieces like this plywood a breeze.

Every

year, I splurge and spend a hundred bucks on new perennials.

Although it seems like a lot of cash, fruit trees take a long time to

mature and it just makes sense to find the money to sink into long term

farm infrastructure as soon as possible.

Every

year, I splurge and spend a hundred bucks on new perennials.

Although it seems like a lot of cash, fruit trees take a long time to

mature and it just makes sense to find the money to sink into long term

farm infrastructure as soon as possible.

This year, Mark talked

me into spending even more on perennials since

we've got several gaps in the forest garden, remnants of the days when

I didn't realize that there is

no point in planting fruit trees in the

waterlogged soil without raising them up on significant mounds and that I should plant

disease resistant varieties rather than just my favorite foods.

So I put in an order for Liberty and

old-fashioned Winesap apples, Redhaven and Cresthaven peaches, Prima

and Bounty Almonds, Carpathian walnuts (to go in the

other forest

garden where there's

room for mammoths), timber bamboo, dwarf Korean

nut

pine, and Chicago hardy fig.

The old saw admonishes

us to dig a $10 hole for a $2 tree, and I'm now

a firm believer in every part of the saying except the hole part.

Take a look at the photos above, and you'll probably become a believer

too. The peach on the left was planted on a large mound of rich

soil that I expanded over the next two years by piling garden weeds

around the mound edges. That peach gave us a glut of

delicious

peaches this

year. The peach on the right was planted one year

later on a much smaller mound that was never expanded. It gave us

four peaches this year, and its leaves have always been a yellowish

color instead of the vibrant green of the peach planted in a $10

mound. The dark green peach is actually 25 feet further away from

the camera, but it looks nearly as big as the yellow peach, doesn't it?

In actuality, our happy peach is about twice as big around.

I've learned my lesson

and have resolved to plant this year's perennials in $20 mounds.

After laying down a sheet of cardboard to kill

vigorous weeds, I hauled four wheelbarrow loads of composted weeds from

the forest pasture, then topped the mound with a  wheelbarrow

load of

the world's

best wood chip mulch.

Unfortunately, I ran out of the prime composted weeds after mound

number three, so I need to come up with some other awesome soil to

build the other half of the mounds.

wheelbarrow

load of

the world's

best wood chip mulch.

Unfortunately, I ran out of the prime composted weeds after mound

number three, so I need to come up with some other awesome soil to

build the other half of the mounds.

As a side note, the

chickens were just as helpful when it came time to shovel compost as

when I was shovelling wood chips. I was impressed to see how well

our merged flock plays together now that the

rooster has taken all of the biddies under his wing. Just a week

ago, our broody hen would never have let the loner forage so close to

her sharp, sharp beak.

The skylight passed its final test last week when it held back a good

size downpour with no leakage.

Today was the day it

graduated to being fully insulated and covered up with plywood.

We went for two layers of

insulation and it wasn't so bad getting it to stay in place with a good

staple gun.

It's hard to describe just

how good it feels to almost be finished with this project

that we began a year ago this week.

Although

I left laying pellets to tide our chickens over, they

clearly got a bit hungry while we were out of town for four days.

They had ignored

the buckwheat and beans before we left, but when we

returned I saw that our flock had eaten up every seed and scratched the

ground into a crumbly texture perfect for planting.

Although

I left laying pellets to tide our chickens over, they

clearly got a bit hungry while we were out of town for four days.

They had ignored

the buckwheat and beans before we left, but when we

returned I saw that our flock had eaten up every seed and scratched the

ground into a crumbly texture perfect for planting.

I shut the flock back

into the larger paddock and planted our winter wheat in the newly bare

ground. The combination of frost and chickens had broken down

even the stems of the previous crop so that I could easily rake the

wheat seeds into the soil.

I would have liked to

plant our wheat earlier, but it's very important to pay attention to

the Hessian fly free date when seeding wheat for grain. This

little insect burrows into leaves of young wheat before the frost, and

heavily infected fields will struggle so much that you get little or no

wheat harvest the next spring. By waiting until cold weather hits

to plant your wheat, you can bypass this pest. Each part of the

country has a Hessian fly free date after which it is safe to plant

your grain.

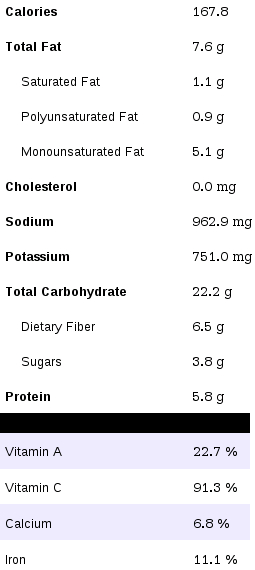

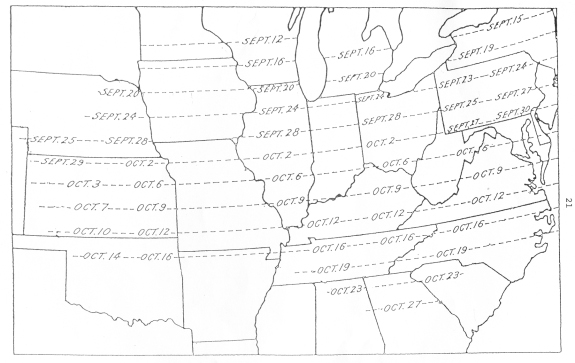

This map of Hessian fly

free dates from Purdue

University is the

best I've found, but I wonder about its accuracy here in the

mountains. I waited a few days longer than the map suggested,

until a frost made me confident that Hessian flies were long

gone. If all goes well, I should be able to graze

the chickens on the winter wheat in about a month, providing

a bit of winter greenery in their diets, then still get grain in spring

of 2011.

One of the last things I need

to do is fabricate some sort of shutter system so the skylight can be

closed half way or all the way or somewhere in between.

Just

a week after noticing that the

six week old buckwheat was going to

seed, I saw these

beautiful oat flowers popping out of my two month old

oats. Since I'm growing the oats as a cover crop right now, I

went ahead and mowed them down with the hedge trimmer.

Incidentally, the hedge trimmer got slightly bogged down in the

thickest parts of the oat beds, so I wouldn't want to use it on

anything tougher than ripening oat stalks.

Just

a week after noticing that the

six week old buckwheat was going to

seed, I saw these

beautiful oat flowers popping out of my two month old

oats. Since I'm growing the oats as a cover crop right now, I

went ahead and mowed them down with the hedge trimmer.

Incidentally, the hedge trimmer got slightly bogged down in the

thickest parts of the oat beds, so I wouldn't want to use it on

anything tougher than ripening oat stalks.

Meanwhile, I'm

continuing to go a little overboard testing out every

possible autumn cover

crop. Two

weeks ago, I planted

several beds with crimson clover, the only fall-planted legume cover

crop that is supposed to be at least semi-reliably winter-killed in our

region.

Early October is late to be planting crimson clover, but the seeds are