archives for 09/2010

I

thought the drying

season had left us

behind, but this week the sun came back out and let me test a few

tomatoes in our automotive dehydrator. It tickles me pink to be

drying vegetables in a totaled

car, even if it is

running fine and useful for ferrying supplies back and forth rather

than being up on blocks in the front yard. My test tray dried

nicely, so today I'll add more tomatoes to the drier.

I

thought the drying

season had left us

behind, but this week the sun came back out and let me test a few

tomatoes in our automotive dehydrator. It tickles me pink to be

drying vegetables in a totaled

car, even if it is

running fine and useful for ferrying supplies back and forth rather

than being up on blocks in the front yard. My test tray dried

nicely, so today I'll add more tomatoes to the drier.

My

goal is to make Mark stop talking about our movie star neighbor's

sun-dried tomatoes and start talking about mine. Hollywood sun-dried

tomatoes (as I've decided to call the delicious concoction) are so

tasty you can't keep them in the fridge or they'll be gone

overnight.

My

goal is to make Mark stop talking about our movie star neighbor's

sun-dried tomatoes and start talking about mine. Hollywood sun-dried

tomatoes (as I've decided to call the delicious concoction) are so

tasty you can't keep them in the fridge or they'll be gone

overnight.

Part 1 of the recipe is

simple --- slice plum-sized romas or other small, meaty tomatoes in

half, sprinkle the cut side with a hint of salt and pepper, and dry

until slightly moist (like a dried apricot). Stay tuned for the

taste explosion of part 2 once I have enough tomato morsels dried to

show you the steps.

The internet is chock

full of articles glowing about biochar's potential, but I seldom find

any useful, hands on information. The Abingdon

Biochar presentation

we attended delved into the nitty gritty.

Today's video highlights

methods you can use to make biochar on any scale. I was

especially intrigued by the idea of modifying a rocket stove to produce biochar while

cooking your dinner.

| This post is part of our Biochar Videos lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

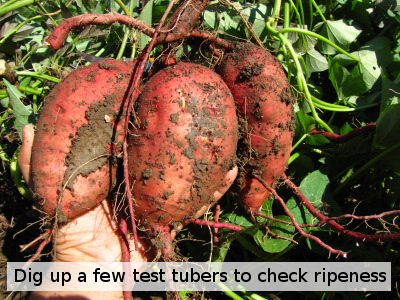

Call in Joey's truck for some assistance.

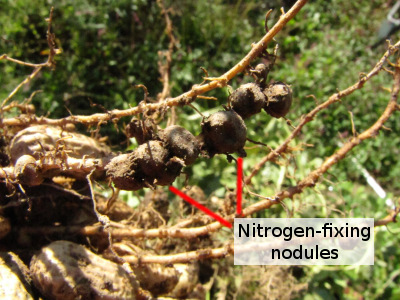

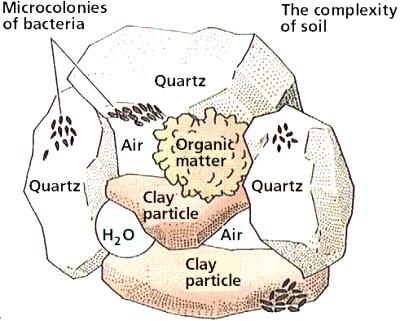

While hanging

out with other farmer geeks last week, I discovered that

there is a cool new cover crop making the rounds --- radishes.

Everyone's glowing about the way tillage radishes, oilseed radishes,

groundhog radishes, fodder radishes, forage radishes, and daikon

radishes mellow clay soil, adding copious amounts of organic matter and

tilling through hardpan. If you play your cards right, you can

even graze your livestock on the radishes a time or two during the fall

since most of the cover crop biomass comes from the roots. What

really caught my interest, though, is news that these cover crop

radishes winter-kill

here in zone 6, meaning that they work perfectly with no-till systems.

While hanging

out with other farmer geeks last week, I discovered that

there is a cool new cover crop making the rounds --- radishes.

Everyone's glowing about the way tillage radishes, oilseed radishes,

groundhog radishes, fodder radishes, forage radishes, and daikon

radishes mellow clay soil, adding copious amounts of organic matter and

tilling through hardpan. If you play your cards right, you can

even graze your livestock on the radishes a time or two during the fall

since most of the cover crop biomass comes from the roots. What

really caught my interest, though, is news that these cover crop

radishes winter-kill

here in zone 6, meaning that they work perfectly with no-till systems.

I clearly had to give a

radish cover crop a try, but which one to choose? A little

research made the choice simpler since all of the names I listed in the

last paragraph refer to the same species (Raphanus

sativus.)

Now, to be fair, cabbage, broccoli, and collards are all members of Brassica

oleracea, so it's

clearly possible to come up with multiple subspecies that act quite

differently. But in the world of cover crop radishes, there is

really only one huge distinction --- the daikon radish has been bred to

be eaten while all of the others have been bred primarily for biomass

and are types of oilseed radishes. Groundhog radish and tillage

radish, specifically, are terms that plant breeders have trademarked

for their line of oilseed radishes.

The

differences between the varieties seem to come down to the roots.

Many people want a long, thin taproot like that found in the tillage

radish, but we don't have hardpan, just heavy clay, so I chose to go

for a more branched root instead. That said, cover crop radishes

are so trendy that the ones I wanted the most were sold out and I had

to settle for a generic oilseed radish from Johnny's Select Seeds.

The

differences between the varieties seem to come down to the roots.

Many people want a long, thin taproot like that found in the tillage

radish, but we don't have hardpan, just heavy clay, so I chose to go

for a more branched root instead. That said, cover crop radishes

are so trendy that the ones I wanted the most were sold out and I had

to settle for a generic oilseed radish from Johnny's Select Seeds.

Before you go out and

seed your front lawn with radishes, though, I should warn you of one

factoid I noticed on every website. When oilseed radishes freeze

and rot over the winter, the resulting smell is quite foul. Maybe

it's best not to plant them beside your front door.

So you've made some

charcoal. How do you get it into the soil in such a way that it

helps your plants grow? The embedded video in this post walks you

through using biochar

in your farm or garden.

| This post is part of our Biochar Videos lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Putting the final piece of tin on the roof sort of feels like the last

piece of a marathon jig saw puzzle.

We recently upgraded the

WaldenEffect blog camera from the Fuji

Finepix S1000fd to a

beefier Canon Power

Shot SX20. I can already

tell a difference, but will wait for more experimentation before I give

a full report on how awesome it is.

Both

the bees and I are starting to plan ahead to overwinter our three

hives. After harvesting

honey this summer, I

put all of the empty supers back on the hives to make it easy for the

bees to clean out the precious juices left behind. Many of those

frames are now empty, so I consolidated all of the frames of honey and

dehydrating nectar into one super per hive, removing the other supers

for winter storage.

Both

the bees and I are starting to plan ahead to overwinter our three

hives. After harvesting

honey this summer, I

put all of the empty supers back on the hives to make it easy for the

bees to clean out the precious juices left behind. Many of those

frames are now empty, so I consolidated all of the frames of honey and

dehydrating nectar into one super per hive, removing the other supers

for winter storage.

Each hive now sports two

deep brood boxes and one super, a clue to my indecision. Last

winter, I overwintered each hive with one full super of honey atop a

single brood box partly full of honey and pollen --- this is what our

neighbors do. But I've had good luck with a double brood box this spring and summer and

have read that continuing the double deep through the winter helps bees

find their honey during cold weather. (Apparently, bees are

British and "mind the gap.") Anyone have thoughts on whether I  should stick to double brood

boxes or go back to one brood box and one super for the winter?

should stick to double brood

boxes or go back to one brood box and one super for the winter?

The bees aren't all that

interested in my experimentation. Instead, they're harvesting ragweed

pollen as fast as

they can so that the first spring hatchlings will have a high protein

diet. I like to tell visitors to the farm that the ten foot tall

ragweed plants around our yard were intentionally left behind --- of

course they didn't just spring up where we forgot to mow! Good

thing neither of us is prone to allergies.

The last video in this

week's lunchtime series may be too scientific for some of you, but I

highly recommend it to folks who are serious about giving biochar a

try. Ken Revell, graduate student at Virginia Tech, is

experimenting with turning overabundant

poultry litter at commercial chicken farms into biochar.

He'll tell you precisely how much biochar is beneficial in soil and why

it shouldn't be applied beyond a certain rate.

| This post is part of our Biochar Videos lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

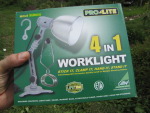

I got this 4 dollar worklight at Harbor

Freight as a replacement for our night time reading lamp.

It's a great value for the

price and flexible enough to fit several applications.

I

posted earlier about Hollywood

Sun-dried Tomatoes

--- how much we love them, and how to dry the tomatoes in preparation

for the main event. Now it's time for the fun part --- assembling

the concoction. This recipe makes about 1 cup of Hollywood

Sun-dried Tomatoes.

I

posted earlier about Hollywood

Sun-dried Tomatoes

--- how much we love them, and how to dry the tomatoes in preparation

for the main event. Now it's time for the fun part --- assembling

the concoction. This recipe makes about 1 cup of Hollywood

Sun-dried Tomatoes.

Step

1: Put 3 large

cloves of garlic in the food processor and cover them up with olive

oil. Blend. (Yes, I can count. I figure those two

small cloves on the right equal one  large clove.)

large clove.)

Step

2: Add about a

cup of loosely packed basil leaves to the food processor. Blend

again.

Step

3: Line the

bottom of your container with one layer of sun-dried tomatoes.

Step

4: Spoon on

enough of your garlic, basil, and oil mixture to liberally cover the

tomatoes.

Step 5: Lay down another layer of

tomatoes, another layer of goop, another layer of tomatoes, and so

forth, until you reach the top of your container.

Step 5: Lay down another layer of

tomatoes, another layer of goop, another layer of tomatoes, and so

forth, until you reach the top of your container.

Step

6: Pour olive oil

over your tomatoes until the oil completely fills the container, as in

the photo below.

Step

7: Put on the lid

and let your concoction marinate in the fridge for a few days.

The tomatoes will plump  back

out and become infused with the herb flavors.

back

out and become infused with the herb flavors.

Alternate

Step 7: We

consider Hollywood Sun-dried Tomatoes to be a winter treat, so we toss

them in the freezer immediately after step 6. After they've

frozen, then thawed back out in the fridge months later, the flavors

have blended perfectly.

How do we eat the

Hollywood Sun-dried Tomatoes? Mark scarfs them down like potato

chips, but I like to save some for more serious cooking. A few of

these tomatoes act very much like a couple of slices of bacon in a dish

--- instant crowd-pleaser. Try them in egg salad, mixed with

pesto over pasta, or as a pizza topping. I usually throw the

tomatoes and a bit of their oil back in the food processor and whir

them up into little bits to make the taste go further, but you can put

whole tomatoes straight onto your winter sandwiches.

Our movie star neighbor

told me that the only flaw in his recipe is

that it requires so much oil, but I don't consider that a

problem. Once

you pull the tomatoes out of the juices, you're left with flavored oil

that will spice up just about any dish. If you can't think of any

other way to use it, try brushing the oil mixture over a piece of stale

bread and toasting it for instant, delicious garlic bread.

The real problem with

these tomatoes, in my opinion, is that there's never enough of

them. This week's bowlful of Martino's and Yellow romas shrunk

down into two scant cups of dehydrated beauties --- just enough for

birthday celebrations for two.

My first indoor picture with

the Canon

Power Shot SX20.

I thought this was a good

demonstration of the automatic setting with the subject bathed in a

mixture of direct light and shadow.

Huckleberry likes to express

ownership of something by taking a nap on it.

Even though the woods is

still green and vibrant, this weekend's chilly mornings herald fall.

Colored leaves are

beginning to wash up on the ford.

I've turned my mind to

winter and filled an entire page with chores that absolutely must get

done before cold weather hits. Near the middle of the list ---

finish cutting and hauling the deadfall from along the driveway to heat

our trailer through the winter. These logs wait patiently for our

attention.

Top of the list --- soak

up the green and sun to savor on a winter's day.

This is a short video of a new

deer deterrent experiment

that makes use

of a 4 dollar toy.

I glued a small hex key to

the wheel which creates a sizeable amount of

vibration and motion.

The video was created with

the Canon Power

Shot SX20 and uploaded to

Youtube with no problems.

"I'm

on the 26th floor of a hotel in downtown Atlanta," our movie star

neighbor explained when I picked up the phone. He never tells me

much about his work since I can't tell actors apart and wouldn't

recognize the names of even the leads in the Footloose

remake he was

working on. Still, I enjoyed imagining our farmer friend rubbing

shoulders with these shining Hollywood stars.

"I'm

on the 26th floor of a hotel in downtown Atlanta," our movie star

neighbor explained when I picked up the phone. He never tells me

much about his work since I can't tell actors apart and wouldn't

recognize the names of even the leads in the Footloose

remake he was

working on. Still, I enjoyed imagining our farmer friend rubbing

shoulders with these shining Hollywood stars.

Back

in his hotel for a three day weekend, the movie star had taken off his

sunglasses and put on his straw hat (figuratively, at least.) The

purpose of his phone call was simple --- our neighbor wanted a weather

report. Once I mentioned our scant tenth of an inch of rain, he

asked if I would mind heading over to his place to water his baby

collards and lemon trees.

Back

in his hotel for a three day weekend, the movie star had taken off his

sunglasses and put on his straw hat (figuratively, at least.) The

purpose of his phone call was simple --- our neighbor wanted a weather

report. Once I mentioned our scant tenth of an inch of rain, he

asked if I would mind heading over to his place to water his baby

collards and lemon trees.

I'm

always glad to visit someone else's garden, and I was especially keen

on this project since my neighbor had recently added ten baby, dwarf

citrus to his collection. In case you don't remember, he's the

one who owns the gargantuan

dwarf Meyer lemon

that produces dozens of fruits every year.

I'm

always glad to visit someone else's garden, and I was especially keen

on this project since my neighbor had recently added ten baby, dwarf

citrus to his collection. In case you don't remember, he's the

one who owns the gargantuan

dwarf Meyer lemon

that produces dozens of fruits every year.

After checking on the

baby lemons, I hosed down his garden and explored his tremendous patch

of butternuts. Although I wouldn't want to live the movie star

part of his life, I love the idea that a homesteader can keep a foot in

both worlds, growing sweet corn and tomatoes in his down time between

making movies.

Last

year at this time, I wrote a lunchtime series about lessons

learned during year 3 on the farm. I've been trying to

put together a similar series for year 4, but the truth is that my

lessons this year are both too large and too small to fit into a

lunchtime series. Basically, I learned relaxation, how to release

all worries on Friday afternoon and take the time to let my creativity

flow. I learned to love the journey of the farm rather than

becoming bogged down in daily problems and the far off glint of the

destination on the horizon. How do you write a lunchtime series

about bliss?

Last

year at this time, I wrote a lunchtime series about lessons

learned during year 3 on the farm. I've been trying to

put together a similar series for year 4, but the truth is that my

lessons this year are both too large and too small to fit into a

lunchtime series. Basically, I learned relaxation, how to release

all worries on Friday afternoon and take the time to let my creativity

flow. I learned to love the journey of the farm rather than

becoming bogged down in daily problems and the far off glint of the

destination on the horizon. How do you write a lunchtime series

about bliss?

If anyone's interested,

I'll post another time about the complicated list of lists I use every

day, week, month, and year to keep myself on the bliss track rather

than on the overextended "we'll never get everything done in time!"

track. (This is only relevant to type A people.) But bliss

doesn't just come from lists.

I

think that this year's journey toward bliss began when we went on our cruise

last October. Somewhere between gazing out at the ocean for hours

and climbing a pyramid, I realized that I'd never been on a true

vacation before in my life. Sure, I'd taken week-long trips to

the beach with my family, flown across the country to a friend's

wedding, but taking time off with the focus solely on myself?

Never.

I

think that this year's journey toward bliss began when we went on our cruise

last October. Somewhere between gazing out at the ocean for hours

and climbing a pyramid, I realized that I'd never been on a true

vacation before in my life. Sure, I'd taken week-long trips to

the beach with my family, flown across the country to a friend's

wedding, but taking time off with the focus solely on myself?

Never.

After we came home from

the cruise, I started to notice how Mark made every day a little

special. A trip to the library turned into a mini-vacation ---

just the two of us together in the car, filling the great gaping hole

in my life that yearns for the printed word, then running together

through the rain into a gas station to splurge on an ice cream cone

that we ate under the gas-pump-overhang, licking streaks of sweetness

as water poured off the roof.

As

spring came to the farm, I developed an allergy to mainstream

media. We haven't had a TV since we moved to the farm, but last

year I spent days listening to NPR while weeding the garden. This

year, even public radio felt like an intrusion, so I began to weed in

silence, watching butterflies

mate while I

wove permaculture relationships in my head. I practiced Spanish

as I built chicken waterer kits, dissolving myself into

the foreign language until I felt like I'd been on, yes, another

vacation during work hours.

As

spring came to the farm, I developed an allergy to mainstream

media. We haven't had a TV since we moved to the farm, but last

year I spent days listening to NPR while weeding the garden. This

year, even public radio felt like an intrusion, so I began to weed in

silence, watching butterflies

mate while I

wove permaculture relationships in my head. I practiced Spanish

as I built chicken waterer kits, dissolving myself into

the foreign language until I felt like I'd been on, yes, another

vacation during work hours.

Soon, I began to have

negative reactions to our twice weekly dose of Netflix movies --- when

romantic comedies give you nightmares, you know it's time to back

off. I bid farewell to quick scene changes and hello to sudden

urges to write and write and write.  One

weekend, I pounded out the first quarter of a young adult novel (to be

finished this winter, if I decide the tale is as gripping as it felt at

the time.)

One

weekend, I pounded out the first quarter of a young adult novel (to be

finished this winter, if I decide the tale is as gripping as it felt at

the time.)

Mark knew he'd won when

I started to ask him if he'd mind taking random afternoons off.

Previously, I had been the task master, keeping our noses to the

grindstone from 9 to 4. Now I could tell when my body needed a

break, or when my mind was full of an idea that was aching to flow onto

paper or computer.

So, lessons learned in

year 4? Following my bliss. Unfortunately, I can't tell you

how to get there, but I can tell you that it's possible.

A few more days of dryness

and the sky light should be completely sealed.

We got a quick rain shower on

Friday just hours after the latest application which set the sealing

back a bit.

A

couple of years ago, a friend served a salsa that was so good it

tempted even me --- a non-salsa-eater --- to go back for seconds.

The salsa was full of fresh corn and tomatoes, and I figured with a

little tweaking it could be turned into a less spicy salad suitable to

be eaten on its own. Here's the result --- a quick, in-season

dish that is also delicious.

A

couple of years ago, a friend served a salsa that was so good it

tempted even me --- a non-salsa-eater --- to go back for seconds.

The salsa was full of fresh corn and tomatoes, and I figured with a

little tweaking it could be turned into a less spicy salad suitable to

be eaten on its own. Here's the result --- a quick, in-season

dish that is also delicious.

- 1 c. fresh sweet corn (2 to 3 large ears)

- 1.75 c. beans (black or pinto are best, pre-cooked)

- 2 to 3 large tomatoes

- 1 medium sweet pepper (optional)

- 1 to 2 cucumbers (optional)

- 1.5 c. loosely packed green onion tops (or about a quarter of an onion, finely chopped)

- 0.5 to 1 tsp chili powder (or finely minced fresh hot peppers. The smaller amount makes a relatively mild dish, the latter a tangy one.)

- 2 tbsp lemon juice (or lime juice)

- salt and pepper to taste

Fill a pot with water

and bring it to a boil as you harvest the sweet corn from your

garden. Drop the cleaned ears into the water and lift them out

nearly immediately (30 seconds or less). Cut the kernels off the

ear with a sharp knife, then run the back of the knife down the cob to

pull out the sweet juices left behind.

Chop the tomatoes,

peppers, cucumbers, and green onions and add them to the sweet

corn. Add the beans, chili powder, lemon juice, salt, and

pepper. We're not fans of cumin or cilantro, but this is the kind

of dish that could use either or both if you like the flavor.

Marinate in the fridge

for an hour or two to meld the flavors, then pour off the excess

juices. Serve as a side dish for burritos, fajitas, quesadillas,

or even pork chops and rice (as I did.)

Our local hardware store doesn't carry Liquid Nails, which means I've

been using an alternative glue known as "Beats the Nail".

It seems like a fine

substitute at a slightly cheaper price.

One thing to remember with a

product like this is to read the safety label on the tube.

Most of these construction adhesive chemicals give off an "extremely

explosive" vapor that could be a real danger if you're in an enclosed

space. Make sure to keep a window or door open and avoid any sources of

flame or sparks.

I'm a bit shocked by my own

mycophobia --- I almost threw away the first King

Stropharia mushroom

that popped up from our graywater

mycoremediation project. This is our first

year growing Stropharia

rugosoannulata, but that's really

no excuse. I was the one who researched and chose the species and

personally inoculated the wood chips. But the mushroom that

sprang up didn't look all that much like the pictures I'd quickly

browsed on the internet, and I thought a wild fungus had invaded my

mycoremediation project.

I'm a bit shocked by my own

mycophobia --- I almost threw away the first King

Stropharia mushroom

that popped up from our graywater

mycoremediation project. This is our first

year growing Stropharia

rugosoannulata, but that's really

no excuse. I was the one who researched and chose the species and

personally inoculated the wood chips. But the mushroom that

sprang up didn't look all that much like the pictures I'd quickly

browsed on the internet, and I thought a wild fungus had invaded my

mycoremediation project.

After a more lengthy

perusal of the internet (and my field guide to mushrooms), I decided

this lovely specimen was indeed a King Stropharia. We ate it

sauteed in garlic last night, so I assume I was right. Here are

the top tips I've run across for King Stropharia identification.

First,

take a look at the ring around the mushroom's stem. Several other

mushrooms have rings, but the ring on a King Stropharia mushroom has

indentations from the gills along the top, giving it a lined

appearance. The lined ring is probably one of the most diagnostic

features of King Stropharia.

First,

take a look at the ring around the mushroom's stem. Several other

mushrooms have rings, but the ring on a King Stropharia mushroom has

indentations from the gills along the top, giving it a lined

appearance. The lined ring is probably one of the most diagnostic

features of King Stropharia.

Next, take a look at the

gills on the underside of the cap. Notice that they are attached

to the stem and are a purply-gray in color. If the gills are

free, then you might have an Agaricus, so beware! Some Agrocybe mushrooms can look similar

too, but have brown gills.

The

top of the cap is often maroon in young specimens, but can also be

plain old brown (especially as the mushroom ages), so cap color isn't

so diagnostic.

The

top of the cap is often maroon in young specimens, but can also be

plain old brown (especially as the mushroom ages), so cap color isn't

so diagnostic.

I find it interesting

that our mycoremediation patch has fruited while the patches I

inoculated at the same time under the canopies of nearby fruit trees

have not. Clearly, the bit of bleach in the dishwater doesn't

hurt King Stropharia one bit, and frequent soakings are a boon.

Paul Stamets has written that King Stropharia mushrooms may actually

depend on coliform bacteria for growth --- perhaps the bacteria going

down the drain have helped our mycoremediation patch come out ahead?

These two PVC pipes connect

to opposite sides of our double sink. We deleted the drain trap as an

experiment to see if I could get an increase in drainage. I was a bit

worried about a gray water smell making its way into the kitchen

without the trap, but after a year of heavy dish washing I think I can

safely report it works just fine without being stinky.

What you don't see here is a

large layer of gravel about a foot below the King Stropharia wood chip bed to prevent standing water.

Even

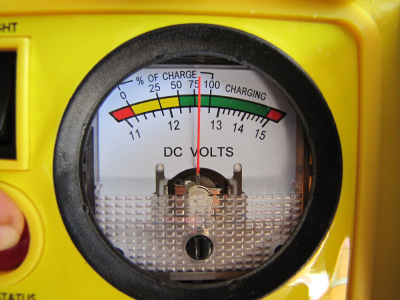

though we haven't set up the solar panels from our plug

and play solar backup

yet, I wanted to test out our Chicago Electric 5-in-1 Portable Power

Packs and see what kind of use we'll be able to get out of them.

We charged the power packs up using house AC for 48 hours (as

instructed in the manual), then I plugged my laptop into one power pack

and turned on the inverter. Everything was going just

fine...until 13 minutes later, my laptop stopped drawing juice. I

turned the inverter off and on again --- still no electricity.

Did I break it already?

Even

though we haven't set up the solar panels from our plug

and play solar backup

yet, I wanted to test out our Chicago Electric 5-in-1 Portable Power

Packs and see what kind of use we'll be able to get out of them.

We charged the power packs up using house AC for 48 hours (as

instructed in the manual), then I plugged my laptop into one power pack

and turned on the inverter. Everything was going just

fine...until 13 minutes later, my laptop stopped drawing juice. I

turned the inverter off and on again --- still no electricity.

Did I break it already?

After a more thorough read of

the manual, it sounds like it's best to turn the power pack's inverter

on for a two minute warmup, turn it off, plug in the laptop, then turn

the inverter back on. After following those directions, my laptop

ran quite happily for another three and a half hours. It probably

would have run longer, but we want our power pack's battery to last as

long as possible, so I turned it off when the indicator hit 50% charged.

After a more thorough read of

the manual, it sounds like it's best to turn the power pack's inverter

on for a two minute warmup, turn it off, plug in the laptop, then turn

the inverter back on. After following those directions, my laptop

ran quite happily for another three and a half hours. It probably

would have run longer, but we want our power pack's battery to last as

long as possible, so I turned it off when the indicator hit 50% charged.

Even

though my laptop's power block rates its energy consumption at 60

watts, a previous experiment with a kill-o-watt device estimated the

laptop's actual usage at 25 watts. (The much higher wattage

listed on the power block assumes that I have lots of USB devices

plugged in, which I seldom do.) So I drew roughly 94 watt-hours

from the power pack --- a bit less than half of the 216 watt-hours the

battery is rated at holding.

Even

though my laptop's power block rates its energy consumption at 60

watts, a previous experiment with a kill-o-watt device estimated the

laptop's actual usage at 25 watts. (The much higher wattage

listed on the power block assumes that I have lots of USB devices

plugged in, which I seldom do.) So I drew roughly 94 watt-hours

from the power pack --- a bit less than half of the 216 watt-hours the

battery is rated at holding.

The only (very minor)

flaw with the power pack is that the inverter has a fan that's about as

loud as a desktop computer. I'd gotten used to the near silence

of my laptop, but I know I  won't be complaining about a

little white noise when I enjoy nearly four hours of laptop use during

a power outage.

won't be complaining about a

little white noise when I enjoy nearly four hours of laptop use during

a power outage.

Although I'm quite

pleased, I've got another trick up my sleeve to stretch our power pack

usage further. The power pack has two cigarette-lighter-type

slots in the front, so I'm going to buy a "car charger" for my laptop

and see how much more runtime I can get when I'm not wasting energy

converting DC to AC and back to DC. Stay tuned for more

information as the experiment progresses.

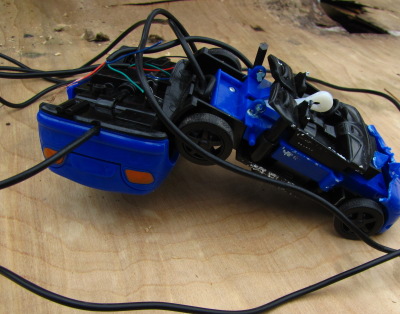

The latest

deer deterrent experiment

ran good for several days, but I forgot to build a roof for it. When it

rained a few days ago water seeped into the motor and burned it out.

This is version 2.0.

The picture illustrates the

one detail that gives this contraption enough unbalanced movement to

make it a funtional deer

deterrent.

It also provides a good

example of the Canon Power

Shot SX20's macro

capability in a low light setting.

While my sister is experimenting

with Plug and play solar backup, I am in the process of learning

to live at a isolated, off the grid, solar powered house.

While my sister is experimenting

with Plug and play solar backup, I am in the process of learning

to live at a isolated, off the grid, solar powered house.

This house was built in the mid 90's, and designed for both passive solar power (with its southern exposure and earth-sheltered rear), and solar power, with a wiring system that is entirely 12 volt throughout. But 15 years is a long time for a solar system to age, and as it degraded, the occupants adapted to living with less and less power.

That is an adaptation I have not made yet, so will this aging system be able to meet my needs? Like Anna, I am starting off with some experiments. The first was to go live there for a week and use as much power as I wanted.

Today I'm back in town. After approximatly 4 full days of use, the first battery bank dropped to 9 volts, my cutoff point for safe use. Which turned out to be below the safe use point of my laptop power adapter, which burnt out the last evening I was there.

I decided to come back while the other bank is still relatively full, leaving the low one connected to the four 64 watt solar panels to charge.

Hurrying downtown to grab lunch in between work on Branchable, I noticed it was a beautiful sunny day, and I realized that this makes such days even better, because besides enjoying them, I know I'll be enjoying the yield on chilly nights sometime later.

Well, in theory. Actually, the very antique charge controller in the house was dead and bypassed, so I removed it. I called its manufacturer wondering if it could be refurbished, but they suggested it belonged in a museum. So I've ordered a new controller, a Xantrex C-35. Until that comes, pretty days like today will charge, or possibly over-charge the batteries, which will then drain back out at night.

At

this time of year, fruit is often free for the asking. We went on

a tour of the Castlewood community cannery this week and stumbled

across a quartet of ladies who had gathered enough apples from trees

going to waste to fill a huge vat of apple butter. Their tale of

frugal scavenging reminded me that one of our neighbors has an orchard

of apples that fall to the ground and rot unless someone collects

them. Off Mark went with an empty basket and a dozen eggs, and

home he came with enough apples to turn into a year's worth of apple

sauce.

At

this time of year, fruit is often free for the asking. We went on

a tour of the Castlewood community cannery this week and stumbled

across a quartet of ladies who had gathered enough apples from trees

going to waste to fill a huge vat of apple butter. Their tale of

frugal scavenging reminded me that one of our neighbors has an orchard

of apples that fall to the ground and rot unless someone collects

them. Off Mark went with an empty basket and a dozen eggs, and

home he came with enough apples to turn into a year's worth of apple

sauce.

I opted to preserve my

apples at home since I generally put

food in the freezer (and process it a bit at a time, a quart here,

and a gallon there.) But community canneries make a lot of sense

for folks who don't want to buy (and maintain) a pressure canner, or

who do most of their year's preserving in one fell swoop. The

Castlewood Cannery will sell you cans for less than a quarter apiece

(if you live in Russell County), or let you bring in your own Mason

jars (charging you a few pennies per jar for use of their facility.)

The canning ladies

regaled me with tales of the bounty they had canned there, ranging from

the usual to cornbread, sausage, and apple sauce cake. I could

tell that spending a day at the Castlewood Cannery would earn me years

of free wisdom, along with the cheap use of kitchen facilities.

To find a community cannery in your area, visit this

website.

Since

the start of the summer I've been trying to figure out how I can

install larger, front swivel wheels on our Craftsman mower.

Since

the start of the summer I've been trying to figure out how I can

install larger, front swivel wheels on our Craftsman mower.

I found this Yard Machine

yesterday for 25 bucks that might just fit the bill once I fix the left

wheel.

The swivel action is said to

make manuvering around corners easy and fun.

Do

you like pumpkin pies? If so, you're in for a treat because

butternut squash pies are twice as good. You can make

pumpkin-like pies out of any kind of winter squash, but after

taste-testing pie pumpkins, acorn squash, cushaw, and butternut we

concluded that the last was by far superior. That said, the

recipe below can be used to create a pie out of any kind of winter

squash. You can even turn Jack-o-lanterns into pie if they

haven't been sitting out for too long.

Do

you like pumpkin pies? If so, you're in for a treat because

butternut squash pies are twice as good. You can make

pumpkin-like pies out of any kind of winter squash, but after

taste-testing pie pumpkins, acorn squash, cushaw, and butternut we

concluded that the last was by far superior. That said, the

recipe below can be used to create a pie out of any kind of winter

squash. You can even turn Jack-o-lanterns into pie if they

haven't been sitting out for too long.

Step

1: Bake the butternut. Cut your butternut

squash in half (carefully!) and scoop out the seeds. Lay the two

halves, cut side down, on a cookie sheet and bake until the skin begins

to blacken and the flesh is very tender. You can bake the squash

at just about any temperature, so I try to plan this step to coincide

with my other baking needs, such as pizza night.

Step

2: Process the butternut. Cool the butternut and peel

off and discard the skin. Then mash up the flesh with a potato

masher (or just with the back of your spoon.) Measure out two

cups of flesh, which will equal one medium butternut, half of a large

butternut, or two small buttercups. I don't worry too much if my

butternut is a quarter of a cup too large or too small --- I throw it

all in.

Step 3:

Make your crust.

I'm lazy, so I've settled on a quick and easy, pat-in-the-pan

recipe. I throw 1 cup of white flour, 0.5 tsp of salt, and 7

tablespoons of cold butter in the food processor and blend until the

butter is cut into coarse pieces. After adding two tablespoons of

cold water and blending a bit more, the dough generally starts to stick

together --- depending on your humidity, you might need to add more or

less water. Pour the dough into the bottom of your pan and press

it into place. Then put the pan in the fridge to stay cool while

you make the pie filling. (I like to make our pies in a cake pan

to leave room for more filling.)

Step 3:

Make your crust.

I'm lazy, so I've settled on a quick and easy, pat-in-the-pan

recipe. I throw 1 cup of white flour, 0.5 tsp of salt, and 7

tablespoons of cold butter in the food processor and blend until the

butter is cut into coarse pieces. After adding two tablespoons of

cold water and blending a bit more, the dough generally starts to stick

together --- depending on your humidity, you might need to add more or

less water. Pour the dough into the bottom of your pan and press

it into place. Then put the pan in the fridge to stay cool while

you make the pie filling. (I like to make our pies in a cake pan

to leave room for more filling.)

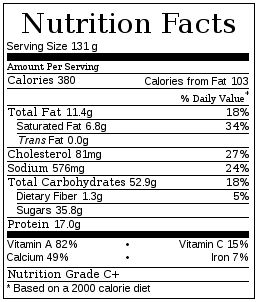

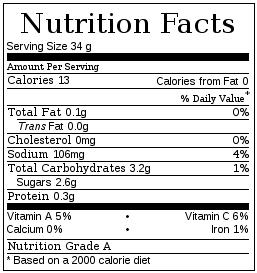

Step 4: Mix up the pie filling. Combine 2 cups of

baked butternut squash from step 2, 1.5 cups of evaporated milk or rich

cream, 0.25 cups of brown sugar, 0.5 cups of white sugar, 0.5 tsp of

salt, 1 tsp of cinnamon, 0.5 tsp of ginger, 0.25 tsp of allspice, and 2

eggs. Blend well. (I seldom have evaporated milk or cream

on hand, so I substitute a concoction of powdered milk and water ---

fill a cup with milk powder and slowly add water, stirring, until the

cup is full of liquid, then repeat with a half cup measurer. The

nutritional information reflects the extra protein from using

powdered milk rather than cream.)

Step 4: Mix up the pie filling. Combine 2 cups of

baked butternut squash from step 2, 1.5 cups of evaporated milk or rich

cream, 0.25 cups of brown sugar, 0.5 cups of white sugar, 0.5 tsp of

salt, 1 tsp of cinnamon, 0.5 tsp of ginger, 0.25 tsp of allspice, and 2

eggs. Blend well. (I seldom have evaporated milk or cream

on hand, so I substitute a concoction of powdered milk and water ---

fill a cup with milk powder and slowly add water, stirring, until the

cup is full of liquid, then repeat with a half cup measurer. The

nutritional information reflects the extra protein from using

powdered milk rather than cream.)

Step

5: Pour the filling into the crust and bake at 425 F for 15 minutes,

then at 350 F for about 30 minutes. This combination of

temperatures just happens to work quite well for baking a chicken as

well, so once again you can double up your oven time.

Step 6: Cool completely before eating. I usually ignore this

admonition, but with butternut pies, the spices really do meld and

taste better once the pie is thoroughly chilled.

Step 6: Cool completely before eating. I usually ignore this

admonition, but with butternut pies, the spices really do meld and

taste better once the pie is thoroughly chilled.

These pies are the

reason Mark became so

obsessed with making sure we have plenty of butternut squash on hand. Although no dessert

is precisely good for you, the hefty dose of protein and vitamins found

in an eighth of this butternut pie make me feel better about baking one

every week.

We spent a great day in Damascus coasting down the mountain with some

friends today.

It was our first bike

adventure together and we had a lot of fun. I'm sure it won't be our

last.

The bike guy charges 25 bucks

for the bike rental which includes a ride up to the top.

I

suspect I won't be seeing this view from my bathtub for much

longer. For the first time in months, I actually heated up water

for bathing --- winter is surely on its way.

I

suspect I won't be seeing this view from my bathtub for much

longer. For the first time in months, I actually heated up water

for bathing --- winter is surely on its way.

About

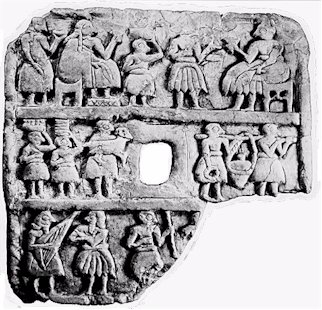

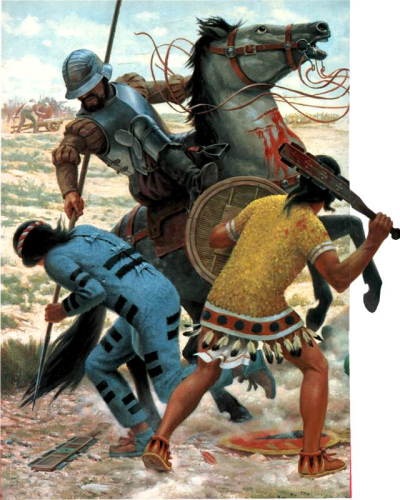

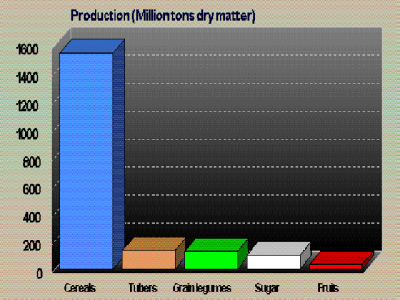

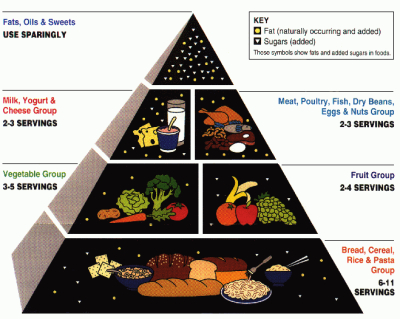

10,000 years ago, nomadic hunter-gatherers in the Fertile Crescent

(in the modern Middle East) cultivated

wheat and became the world's first farmers. They left their

nomadic ways behind and settled down into villages, domesticating

animals and other vegetables to go along with their grain. Food

surpluses allowed the villagers to specialize, and soon their arts and

technologies exploded, giving rise to the world's first civilizations.

About

10,000 years ago, nomadic hunter-gatherers in the Fertile Crescent

(in the modern Middle East) cultivated

wheat and became the world's first farmers. They left their

nomadic ways behind and settled down into villages, domesticating

animals and other vegetables to go along with their grain. Food

surpluses allowed the villagers to specialize, and soon their arts and

technologies exploded, giving rise to the world's first civilizations.

Although a few

hunter-gatherer societies remain in remote areas, most

humans have followed these peoples' lead and created their own

agriculture-based societies. Those of us  living in agricultural

societies tend to take a manifest destiny approach to the history of

farming and civilization, considering both to be part of an inevitable

march forward

toward better times. As Roland pointed out in a comment to a

previous

lunchtime series,

agriculture is at the root of what has

allowed us the spare time to develop ipods, refrigerators, and modern

medicine.

living in agricultural

societies tend to take a manifest destiny approach to the history of

farming and civilization, considering both to be part of an inevitable

march forward

toward better times. As Roland pointed out in a comment to a

previous

lunchtime series,

agriculture is at the root of what has

allowed us the spare time to develop ipods, refrigerators, and modern

medicine.

But a closer look at the

dawn of agriculture shows that farming had at

least as many detrimental effects as beneficial ones. Is there a

seamy underbelly to the advent of farming? Can modern societies

overcome the minefield left behind by early agriculture? This

special two-week lunchtime series explores these intriguing questions.

This post is part of our History of Agriculture lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

This slightly damaged stock

tank was rescued from the dump recently by someone who thought I could

use it for one of my contraptions. Thanks Dennis.

One of the many winter

projects on the drawing board is a do

it yourself black soldier fly bin, and I think this container will

work just fine.

People

like to say that varroa mites on honeybees are a lot like ticks on a

dog, but when you compare the relative sizes, you'll see that a varroa

mite is more like a blood-sucking squirrel latched onto your dog's

back. Given the size of the mites, it's not surprising that a

heavy varroa mite infestation can weaken a hive so much that it dies

over the winter.

People

like to say that varroa mites on honeybees are a lot like ticks on a

dog, but when you compare the relative sizes, you'll see that a varroa

mite is more like a blood-sucking squirrel latched onto your dog's

back. Given the size of the mites, it's not surprising that a

heavy varroa mite infestation can weaken a hive so much that it dies

over the winter.

Most beekeepers treat

their hives with insecticidal strips during the fall and winter, but

the chemical control method has obvious problems. You have to be

extremely careful not to eat any of the honey that was in the hive

during the treatment period, which makes life difficult the next spring

if the bees didn't consume all of their winter stores. Beekeepers

who throw in chemicals every year without testing to see whether their

hives need it also start to run up against pesticide-resistant mites

--- bad news. Finally, the organic gardener in me has to wonder

what such a heavy dose of insecticide does to the honeybees.

Luckily, there are alternatives.

We use quite a bit of

passive management designed to reduce varroa mite populations in the

hive. Foundationless frames and screened bottom boards

both help cut down on varroa mite infestations, and the latter also

allows us to monitor how many varroa mites are actually present so that

we don't put chemicals in a hive that isn't very heavily

infested. With winter looming, I figured I'd better check the

mite levels in our three hives.

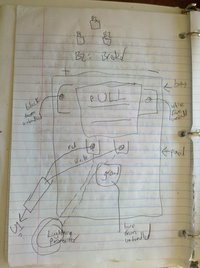

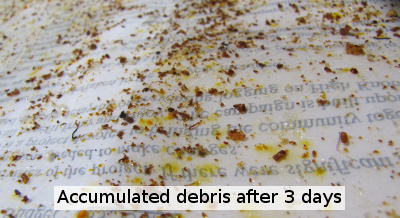

Homemade

varoa mite test sheets

Homemade

varoa mite test sheets

You can buy varroa mite

test sheets ("sticky boards") from bee supply stores, but I'm too cheap

so I've experimented until I figured out an easy way to make the sheets

at home. Just cut a piece of cardboard to 13" by 20", tape down

white scrap paper on one side, and smear on petroleum jelly (vaseline)

until it covers the entire surface of the paper. If you've got

more than one hive, it's best to label your various test sheets before

bringing them outside in order to avoid confusion. Slip one test

sheet under the screened bottom board of each hive, then remove it

three days later and take a look.

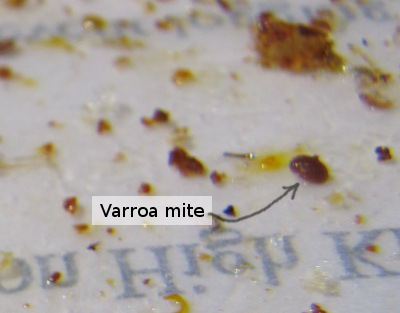

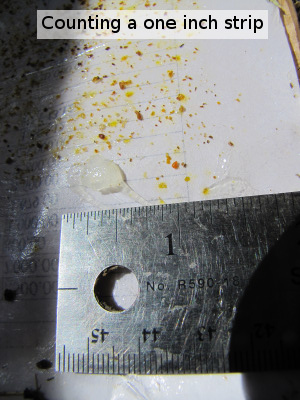

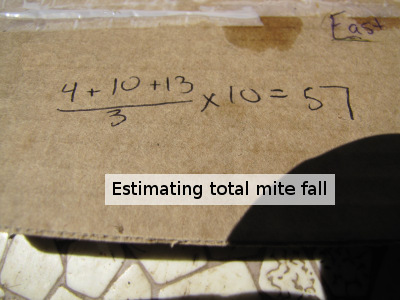

Chances

are, your test sheet will be coated in debris, so you'll need to look

carefully to see the round, dark brown varroa mites. If you're

industrious, you can count every mite on the sheet, but I generally

just rule off three strips, each one inch wide, and count the mites in

each one. Since the screened section of the bottom board is ten

inches wide, adding up the number of mites in my three strips, dividing

by 3, then multiplying by 10 gives a rough estimate of total varroa

mite fall during the three day period. My three day mite counts

came to 57 and 40 in my two smaller hives, and a whopping 540 in my

biggest hive.

Chances

are, your test sheet will be coated in debris, so you'll need to look

carefully to see the round, dark brown varroa mites. If you're

industrious, you can count every mite on the sheet, but I generally

just rule off three strips, each one inch wide, and count the mites in

each one. Since the screened section of the bottom board is ten

inches wide, adding up the number of mites in my three strips, dividing

by 3, then multiplying by 10 gives a rough estimate of total varroa

mite fall during the three day period. My three day mite counts

came to 57 and 40 in my two smaller hives, and a whopping 540 in my

biggest hive.

Varroa

mite threshold

Varroa

mite threshold

The hardest part of

checking on varroa mites is figuring out how many mites you can have in

your hive without worrying. A quick search of the internet and my

bookshelf yields up numbers ranging from 50 mites per day to 200 mites

per day as the treatment threshold. For a three day mite count

like mine, that means I can have somewhere between 150 and 600 mites on

my test sheets without taking action.

The reason the threshold

figures vary so much is that you'll get widely variable mite fall

numbers from the same hive when you test during different parts of the

year even if the percentage of bees infested by mites stays the

same. Since the typical hive has few bees in it during early

spring, few mites will fall to the ground. The same hive in the

middle of summer may have ten times as many bees present (or more), so

you'd expect to see ten times as many mites. With that

information in mind, it's not all that surprising that the hive we

bulked up with early double deeps has many more varroa mites

than the hives which began the year with a single brood box.

A North

Carolina beekeeping document suggests a way to deal with

this inherent problem in the sticky board test method. They tell

you to estimate how many adult bees are present in the hive by counting

how many frames are completely coated on both sides with bees during

your inspection. A medium frame thus coated will hold about 1,250

bees and a  deep

frame will hold about 2,000 bees. If your sticky board count

shows more than 2 mites per thousand bees per day in mid-August or more

than 4 mites per thousand bees per day in September, you should find a

way to reduce the mite population. Unfortunately, I hadn't read

this the last time I opened the hive, so I don't have any data

available except my gut reaction that one of my hives has many more

bees than the others.

deep

frame will hold about 2,000 bees. If your sticky board count

shows more than 2 mites per thousand bees per day in mid-August or more

than 4 mites per thousand bees per day in September, you should find a

way to reduce the mite population. Unfortunately, I hadn't read

this the last time I opened the hive, so I don't have any data

available except my gut reaction that one of my hives has many more

bees than the others.

Clearly, I don't need to

worry about two of my hives at all since they averaged 13 and 19 mites

fallen per day. My biggest hive, though, has ten times as many

mites even though I estimate it only has perhaps two or three times as

many bees in the hive. I could treat that hive, but I had a

colony that was similarly on the edge last fall and it made it through

the winter with flying colors, so I'm going to take my chances.

As I turn into a more experienced beekeeper (and have more data from my

own hives), I'll feel more confident about which varroa mite levels are

no big deal and which ones require drastic action.

Before I launch directly into the history of

agriculture, I want to spend a post citing my sources. Nearly all

of the information I'll discuss later comes from three books, each of

which is a fun read and chock full of fascinating information I didn't

have time to include in this lunchtime series. The books also

provide more in depth evidence for each of the assertions I'll make in

the following posts --- I've glossed over certain bits of data to keep

the posts short, sweet, and to the point. To paraphrase an old

folk song, if you want anymore you can read it yourself.

Before I launch directly into the history of

agriculture, I want to spend a post citing my sources. Nearly all

of the information I'll discuss later comes from three books, each of

which is a fun read and chock full of fascinating information I didn't

have time to include in this lunchtime series. The books also

provide more in depth evidence for each of the assertions I'll make in

the following posts --- I've glossed over certain bits of data to keep

the posts short, sweet, and to the point. To paraphrase an old

folk song, if you want anymore you can read it yourself.

Diamond, Jared.

1997. Guns,

Germs, and Steel.

W.W. Norton & Company, New York.

Leonard, Jonathon

Norton. 1974. The First

Farmers.

Littlehampton Book Services Ltd.

The only flaw in The First Farmers

is the book's age. Presumably, some of the individual facts are a

bit out of date, but the book is still a very good introduction to the

advent of farming, focusing primarily on the Fertile Crescent.

It's easy to read and full of beautiful photos, but at the same time is

clearly based on specific scientific studies.

The only flaw in The First Farmers

is the book's age. Presumably, some of the individual facts are a

bit out of date, but the book is still a very good introduction to the

advent of farming, focusing primarily on the Fertile Crescent.

It's easy to read and full of beautiful photos, but at the same time is

clearly based on specific scientific studies.

Manning, Richard.

2004. Against

the Grain: How Agriculture Has Hijacked Civilization. North Point Press,

New York.

This post is part of our History of Agriculture lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

I predict this will save us 2 to 3 hours of weeding per bale.

In

my early childhood memories, it seems like my mother was always cutting

up apples. Perhaps she was carefully removing the skins so that

my younger sister could wrap her toothless mouth around them (allowing

me to eat the parts left behind.) Or maybe Mom was making a

"Dan'l Boone apple pie" --- whole wheat crust with barely a hint of

butter, apples cored but not peeled, filling mildly sweetened with a

dab of honey. Often, though, it seemed like she was just cutting

up apples to be cutting them up, and she never minded me snagging one

or two or ten out of her bowl.

In

my early childhood memories, it seems like my mother was always cutting

up apples. Perhaps she was carefully removing the skins so that

my younger sister could wrap her toothless mouth around them (allowing

me to eat the parts left behind.) Or maybe Mom was making a

"Dan'l Boone apple pie" --- whole wheat crust with barely a hint of

butter, apples cored but not peeled, filling mildly sweetened with a

dab of honey. Often, though, it seemed like she was just cutting

up apples to be cutting them up, and she never minded me snagging one

or two or ten out of her bowl.

Mom's

apple sauce was simply stewed apples, skins left on. Although I

heartily approve of eating fruits and vegetables skin-on so that you

don't lose the vitamins, I like the texture of skinless apple sauce

(which can easily be made at home by stewing apple wedges, then passing

them through a Foley mill to remove the skins.) I invited Mom

over to help me cut up our scavenged

apples, then

experimented with various methods of making skin-on apple sauce.

Mom's

apple sauce was simply stewed apples, skins left on. Although I

heartily approve of eating fruits and vegetables skin-on so that you

don't lose the vitamins, I like the texture of skinless apple sauce

(which can easily be made at home by stewing apple wedges, then passing

them through a Foley mill to remove the skins.) I invited Mom

over to help me cut up our scavenged

apples, then

experimented with various methods of making skin-on apple sauce.

The best method seemed

to be --- cut the apples into quarters, removing the cores; cook in a

pot with some water until the apple meat begins to fall off the skins;

then blend in the food processor. You're less likely to scorch

the bottom of the pan if you cook up your apple sauce in a skillet

rather than a pot and fill at least a couple of inches in the bottom of

the

pan with water. The result is very much like storebought apple

sauce in texture, but with flecks of skin here and there. (The

photo above shows the result of my experiment.)

the

pan with water. The result is very much like storebought apple

sauce in texture, but with flecks of skin here and there. (The

photo above shows the result of my experiment.)

I'd be curious to hear

if anyone else has a different method of creating skin-on apple

sauce. Meanwhile, if you're overflowing in scavenged apples (and

you should be --- it's that time of year), you might want to check out

a post I made a couple of years ago about how

to make apple cider in a juicer.

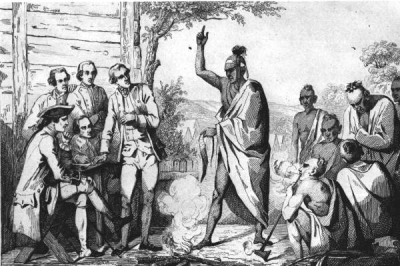

Mankind

has fed ourselves as hunter-gatherers for 99% of our time on

earth. Why did

we suddenly put down our spears and pick up the hoe?

Mankind

has fed ourselves as hunter-gatherers for 99% of our time on

earth. Why did

we suddenly put down our spears and pick up the hoe?

Archaeologists agree

that several factors coincided to make agriculture

possible around 8500 BC. Wild cereals were already part of the

diet of nomadic hunter-gatherers, but around 10,000 years ago climate

change increased the extent of these fields of native grain in the

Fertile Crescent. At about the same time, we began to develop

tools

and tricks necessary to take full advantage of the wild grains --- we

created sickles, baskets, and mortars and pestles; we figured out how

to roast grains so that they wouldn't sprout during  storage; and we

developed underground

storage pits.

Suddenly, a family could

gather enough seeds to feed itself for a year during the three week

ripening season of the wild wheat.

storage; and we

developed underground

storage pits.

Suddenly, a family could

gather enough seeds to feed itself for a year during the three week

ripening season of the wild wheat.

Now, as someone who

spends months during the summer carefully tending

my crops, I was a bit stumped when I read that last fact. If I

could just go out and pick wild swiss chard, okra, and tomatoes for

three weeks once a year and not have to plant and weed all season, I

think I would choose the former occupation. Why did these early

wheat-eaters

turn into farmers?

The switch from

gathering this abundant wild wheat to growing it seems

to come down to one factor --- overpopulation. At the same time

that wild wheat was expanding in the Fertile Crescent, large wild game

was becoming much less numerous, either because of climate change,

because we became better hunters, because our numbers exploded, or some

combination of these three factors. Whatever the reason, hunting

was no longer really working for us, so wheat became more and more

important in our diets.

It seemed sensible to

settle down near the important wheat fields, and

this change in turn dismantled the factors that had previously kept our

population in check. As nomads, our women had been limited to

bearing children about four years apart in age since the first child

had to be old enough to walk by itself before baby number two could

come along --- Mom could only carry one kid at a time during frequent

moves and I guess Dad wasn't the nurturing type. But we no longer

had this restriction in our new, settled lifestyle, so our reproductive

rate doubled, with women producing on average one child every two years.

When previously ample

wheat fields suddenly became too bit puny to feed our burgeoning

numbers, agriculture was the clear solution. By clearing

new ground outside the natural wheat fields, we were able to plant wild

wheat seeds and reap harvests from a larger area. Agriculture was

born.

This post is part of our History of Agriculture lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

The 5 gallon

bucket method continues

to be an efficient solution for moving large quantities of horse manure

from the neighbor's field to our compost pile.

This latest trip yielded

almost 150 gallons of organic matter, which we traded a dozen eggs and

one of our valuable

butternut squashes for.

After

researching fruit growing for a decade, I moved to the farm and quickly

discovered how much I didn't know. I've written previously about

how our heavy clay soil with high groundwater requires that we plant our

fruit trees on mounds --- learning that set us back about two

years. But what I want to talk about in this post is how to

choose a combination of fruit trees that will keep you fed throughout

the year.

After

researching fruit growing for a decade, I moved to the farm and quickly

discovered how much I didn't know. I've written previously about

how our heavy clay soil with high groundwater requires that we plant our

fruit trees on mounds --- learning that set us back about two

years. But what I want to talk about in this post is how to

choose a combination of fruit trees that will keep you fed throughout

the year.

Once I found the right

farm, the young, exuberant, farmer-wannabe Anna browsed the catalogs

and

gleefully picked out my favorite fruit varieties. Now, I'm not

going to tell you to plant a variety you don't like, but there's a lot

more to planning a homestead orchard than planting Stayman Winesaps

because that's the kind of apple you've always bought in the

store. Our Stayman Winesap tree will be hitting the burn pile

this

winter because it is so sensitive to the Cedar

Apple Rust that

there's no point in even trying  to

grow a Stayman here with organic

methods. Similarly, the self-pollinating, white dwarf cherry I

was so sure would start producing fruit in 2009 gets so

badly defoliated by Japanese Beetles every year that it may never give

us a

cherry --- I'm going to experiment for another year or two before I rip

it out, but I wouldn't say the variety was a good choice.

to

grow a Stayman here with organic

methods. Similarly, the self-pollinating, white dwarf cherry I

was so sure would start producing fruit in 2009 gets so

badly defoliated by Japanese Beetles every year that it may never give

us a

cherry --- I'm going to experiment for another year or two before I rip

it out, but I wouldn't say the variety was a good choice.

One way to find

varieties that will survive your local bugs and

diseases is to check out what kind of fruit trees your organic gardener

neighbors grow. The

apples we scavenged

are from Liberty apple

trees that are never pruned or sprayed, and

yet provide a bountiful crop every year. Not only that, I felt

like the apples were tastier than storebought Stayman Winesaps --- a

Liberty apple will definitely be making its way into our garden this

winter.

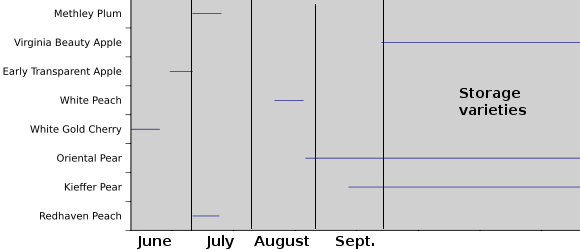

I

also didn't put enough thought into spreading our ripe fruit throughout

the year. I learned with our mature peach this year that I

wouldn't want to have more than one tree in full fruit during any

given week --- it just takes a lot of time to process that

bounty. On the other hand, if you're like me and think that the

only real way to eat fruit is

fresh, you'd better fill in all of those gaps so that you don't spend a

month in August wishing you had fresh fruit. Although our vine

and bush fruits bear relatively continuously through the growing

season, I'd still like to add in a late July and early August fruit

tree, replace our problematic cherry with a different early fruit,

plant a mid-season apple tree to feed me before the pears fully ripen,

and perhaps expand our storage apple selection to keep me in fresh

fruit through the winter.

I

also didn't put enough thought into spreading our ripe fruit throughout

the year. I learned with our mature peach this year that I

wouldn't want to have more than one tree in full fruit during any

given week --- it just takes a lot of time to process that

bounty. On the other hand, if you're like me and think that the

only real way to eat fruit is

fresh, you'd better fill in all of those gaps so that you don't spend a

month in August wishing you had fresh fruit. Although our vine

and bush fruits bear relatively continuously through the growing

season, I'd still like to add in a late July and early August fruit

tree, replace our problematic cherry with a different early fruit,

plant a mid-season apple tree to feed me before the pears fully ripen,

and perhaps expand our storage apple selection to keep me in fresh

fruit through the winter.

My final word of wisdom

is --- don't price shop for fruit trees.

I am a skinflint, and have been guilty of picking the cheapest tree

from the cheapest catalog in the past. That's how I ended up with

an unknown white peach after three years of nursing

along what I

thought was going to be a yellow peach. (Luckily, the white peach

was still delicious.) Choosing a fruit tree is a lot like

choosing a spouse --- it will be an integral part of your life for a

long, long time. Choose quality.

I'm still barely a

seedling in a tree's eyes, so I'm sure I have a lot

more to learn. What other pitfalls would you point out for a new

orchardist to sidestep?

The

results of the Neolithic

Revolution were

striking. On the positive side, a

farmer was able to grow more food than he needed to feed his family, so

for the first time in human history we saw specialization.

Agricultural societies were able to support leaders, artists,

craftsmen, priests, scribes, and soldiers, none of whom had to worry

much about where their food came from.

The

results of the Neolithic

Revolution were

striking. On the positive side, a

farmer was able to grow more food than he needed to feed his family, so

for the first time in human history we saw specialization.

Agricultural societies were able to support leaders, artists,

craftsmen, priests, scribes, and soldiers, none of whom had to worry

much about where their food came from.

We also had time to

create

new tools and technologies. The first example of writing sprang

up in

the Fertile Crescent, probably as a method of recording information

about ownership and production of land. In fact, you can follow

the trail of agriculture all the way to present, tracing the

domestication of wheat, maize, and rice foward to most of humanity's

most striking

accomplishments.

Agriculture basically

created civilization as we know it. In fact, using

anthropologists' definition of civilization, farming was a prerequisite

for civilization in every part of the world. This is the

explanation you'll see in most modern history texts --- doesn't it

sound a bit like a revisionist history? "Look, the people with

agriculture won! Let's say that agriculture created civilization."

This post is part of our History of Agriculture lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

The first bit of feedback I

have on the new Canon

Power Shot SX20 comes

after only a few weeks of experimentation.

It's been my experience that

the automatic setting is not quite acceptable in most situations, that

is to say the picture either has the color off or it's a bit too washed

out. Anna has some

good examples of this on her more

in depth review.

The good news is that the

manual mode is easy to use and understand. Making this camera maybe not

a good choice for someone who struggles with basic point and shoot

units.

The above picture was taken

today by Anna on the SCN setting.

In addition to expanding

our fruit orchard,

this winter we plan to branch out into nuts. In the past, I've

steered clear of nut trees for a couple of very good reasons --- most

nut trees are much bigger than fruit trees and it takes a long time to

crack all of those nuts. However, I just discovered that almonds

are peach-sized trees sometimes no more than 15 feet tall, and Mark has

promised to invent an automatic nutcracker for me by the time they

bear. As you can see, almond flowers are also so beautiful that

the trees are sometimes grown as ornamentals. Time to pick out

some nuts!

In addition to expanding

our fruit orchard,

this winter we plan to branch out into nuts. In the past, I've

steered clear of nut trees for a couple of very good reasons --- most

nut trees are much bigger than fruit trees and it takes a long time to

crack all of those nuts. However, I just discovered that almonds

are peach-sized trees sometimes no more than 15 feet tall, and Mark has

promised to invent an automatic nutcracker for me by the time they

bear. As you can see, almond flowers are also so beautiful that

the trees are sometimes grown as ornamentals. Time to pick out

some nuts!

A quick search turns up

the following nuts being sold to backyard growers:

| Variety |

Zone |

Spacing |

Pros and Cons |

| Almond |

5 - 9 |

10 - 22 ft. |

With new, self-pollinating

varieties on the market, the small size of almonds makes them easy to

fit into a nook in your garden. On the other hand, rain and high

humidity in July and August can rot the nuts. |

| Black Walnut |

5 - 9 |

30 - 40 ft. |

Very large trees with very hard

nuts. We actually have dozens of these growing on our property

already, but I rarely bother to gather the fruits since you have to

crack them with a hammer. |

| Butternut | 4 - 9 |

30 - 40 ft. |

Very winter hardy and tolerant

of poor soil. However, most of our native butternut trees have

been killed by a blight, so be sure to pick out a resistant variety.

Shells are very hard and the tree is large and needs a pollinator. |

| Carpathian Walnut |

5 - 9 |

25 - 40 ft. |

The Carpathian Walnut is

significantly more cold hardy than the English Walnut, but is still

damaged by spring frosts. The nut is supposed to be very similar

to the walnuts you buy in the store. The trees are large and

require a pollinator. |

| Chinese Chestnut |

4 - 9 |

20 - 40 ft. |

The trees are large and two

trees are required for good fruit set. The prickly cases around

the fruits are very tough on bare feet. Chestnuts don't store

well and must be harvested every day or two or they will rot on the

ground. All of that said, though, chestnuts are delicious and

have a thin shell that can be pried off without a nutcracker --- I can

bite them open in a pinch. Chestnuts are the most common nut

trees grown in our region. |

| English Walnut | 5 - 9 |

40 - 50 ft. |

Sensitive to cold weather and

spring frosts. Very large trees, but most don't require a

pollinator. These are the walnuts you buy in the store, with

relatively thin shells and a taste everyone can enjoy. |

| Hazelnut/Filbert |

5 - 8 |

15 - 20 ft. |

We've already planted a few

hybrid hazels and wrote

extensively about them here. In short, they're small and easy

to fit into your backyard, but you need to pick out a blight-resistant

version and plant two for pollination. |

| Heartnut | 5 - 8 |

20 - 25 ft. |

This is a variety of Japanese

Walnut. It seems to be mostly a gimmick --- people like the

heart-shaped nut. It needs a pollinator. |

| Hickory | 5 - 8 |

20 - 40 ft. |

Large tree that needs a

pollinator. Nut shells are very hard and the meats are small.

If I want hickory nuts, I'll gather them out of the woods. |

| Pecan | 4 - 9 |

40 ft. |

The pecan is a southern

specialty, but some hardy varieties can be grown as far north as zone

4. Like walnuts and almonds, the nuts are familiar and delicious.

The downside is size and the need for a pollinator. |

| Stone Pine |

varies |

??? |

The Korean

Nut Pine is hardy down to zone 4, while the more common Stone Pine (Pinus

pinea) is only hardy to zone 7. They seem to require very

little work, but take more than a decade to bear. I can't seem to

find any real spacing data on the internet --- some sites say you can

plant them 10 feet apart, while others tell you to go for 40 feet. |

As I mentioned, we're already trying out hybrid hazelnuts (highly recommended, though they're not big enough to fruit yet), and I planted a Korean Nut Pine from seed last year (which is now about an inch tall.) Of the other types of nuts, I'm most interested in trying out an almond in the sunniest part of the garden, where perhaps our humidity won't be so devastating, and an English Walnut in the shadiest part of the yard, where I might trick it

into flowering late after

hard spring frosts have passed us by. Almonds (part of my

breakfast at the moment) and walnuts (integral to pesto) also happen to

be the nuts most frequently served in our household's meals.

into flowering late after

hard spring frosts have passed us by. Almonds (part of my

breakfast at the moment) and walnuts (integral to pesto) also happen to

be the nuts most frequently served in our household's meals.I've read varying reports about whether you need to buy named varieties or can just sprout shelled nuts out of the grocery store. Almonds seem to be a bad candidate for growing from seed since the nuts are bitter in most of the offspring, so I'll probably go ahead and buy named varieties for both of our nut additions.