archives for 08/2010

Everett and Missy (from Living a Simple Life) were kind enough to invite

us over to

their new homestead for lunch on Saturday and I leapt at the

offer. There are few things I like better than a farm tour --- a

great chance to walk around someone else's operation and get ideas.

Everett and Missy (from Living a Simple Life) were kind enough to invite

us over to

their new homestead for lunch on Saturday and I leapt at the

offer. There are few things I like better than a farm tour --- a

great chance to walk around someone else's operation and get ideas.

The farm was beautifully

manicured (way out of my weed-overgrown league), and I'm sure lots

of you would love to see pastoral photos. However, being who I

am, I took a few pictures of the chickens and then a whole bunch of

pictures of the garden.

Everett and Missy made

the wise choice to spend their first year on the farm focusing on

infrastructure, but they didn't ignore the garden entirely.

Instead, they planted a few cucurbits down by the creek, hired a nearby

farmer to plow up a field to plant a clover cover crop in a second

area, and then spread thick straw mulch over a third area.

This third area, of

course, was the one that caught my eye --- a patch of lawn being

transformed into a budding Ruth

Stout garden.

Mushrooms were already hard at work improving the soil, and worms had

clearly been attracted to the moist, bare soil beneath the  mulch.

The couple's free range Buckeye chickens loved scratching up

the mulch to find critters...and depositing their own organic

fertilizer in exchange. I wouldn't be surprised if this plot

turns into a bountiful and trouble-free garden next year.

mulch.

The couple's free range Buckeye chickens loved scratching up

the mulch to find critters...and depositing their own organic

fertilizer in exchange. I wouldn't be surprised if this plot

turns into a bountiful and trouble-free garden next year.

Of course, we didn't

escape the farm tour entirely unscathed. Like they say, August is

the only time you have to lock your car in Appalachia --- otherwise,

you'll come back to discover it full of zucchinis. Thanks for the

produce, the delicious lunch, and the tour!

Although The

Mulch Company has a fine product with great service, we've decided

their price is too high.

Anna's mulch instinct is

telling her we can get more for less somewhere else, and when it comes

to mulch I choose to yield to her organic intuition.

Congratulations to

Bladerunner, the winner of our most recent

giveaway!

Bladerunner, drop me an email with your t-shirt size and

we'll get your prizes out to you as soon as possible.

Thanks to everyone who helped spread the word! Don't despair if

you didn't win --- we'll start up another giveaway before long.

Since this is a light

post, I thought I'd throw in a photo I've been saving for a couple of

weeks. There's not really much to say about it, except that

succession planting corn is the best way to sweeten dinners all summer

long. Sweet corn patch part two is about to hit the plate....

Last

year, the blight took me by surprise and sent me reeling. Since

then, I've done a lot of plotting and researching, and I feel like I

have the possibility of harvesting a crop after the fungus hits.

Last

year, the blight took me by surprise and sent me reeling. Since

then, I've done a lot of plotting and researching, and I feel like I

have the possibility of harvesting a crop after the fungus hits.

I've talked about our

extreme tomato pruning

before, but I want to add a few notes since I can already tell that I'll be pruning slightly

differently next year. Most importantly, I plan to snip off the

bottom leaves repeatedly rather than spending my weekly pruning

sessions solely cutting back suckers and tying up the main stems.

I've noticed that even leaves attached a foot above the ground bend

downward with age until they are dipping into the splash zone.

Unsurprisingly, the first symptoms of the blight show up as yellowing

and browning of these leaves --- a sign that fungal spores are being

exposed to the air. In the future, I'll clip off low leaves as

soon as they droop.

| This post is part of our Organic Tomato Blight Control lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

Stink

bugs are usually bad news in the garden. They suck the juices out

of your plants and the chickens won't even eat them because of the

Stink

bugs are usually bad news in the garden. They suck the juices out

of your plants and the chickens won't even eat them because of the

noxious fluid they squirt out when disturbed. But if I'm honest,

my antipathy toward the insects dates from childhood. You see,

stink bugs love blackberries, and so do I. Pop a blackberry in

your mouth without looking and there's a good chance a stink bug might

come along for the ride, leaving the most awful taste in your mouth

imaginable.

noxious fluid they squirt out when disturbed. But if I'm honest,

my antipathy toward the insects dates from childhood. You see,

stink bugs love blackberries, and so do I. Pop a blackberry in

your mouth without looking and there's a good chance a stink bug might

come along for the ride, leaving the most awful taste in your mouth

imaginable.

Despite my scarred

childhood, stink bugs have now been redeemed in my eyes. I was

out on my weekly bug-picking expedition Monday, squashing asparagus

beetle larvae and

tossing all of the other bad bugs into a cup of water to give to the

chickens. Guess who was already helping with the asparagus beetle

control? This predatory stink bug uses its long proboscis to spear

insects and drain them dry rather than sucking a plant for lunch.

I'm glad I decided to

use manual control this year on our insects, even though it is a bit of

a pain to pick bugs for an hour a week during the growing season.

I've noticed spiders, ladybugs, and now this stink bug moving into the

asparagus, keeping the beetle populations in check. Maybe in a

few years, our beneficial insect populations will be so healthy that I

won't have to hand-squash larvae?

But

what do you do if, despite preventative pruning, your tomatoes begin to

show signs of late blight?

Rather than sticking your head in the sand the way we did last year,

your best bet is to take decisive action immediately. Single out

any tomatoes on which the blight has progressed beyond the very lowest

leaves and delete the entire plant. Then clip off any blighted

lower leaves on nearby plants.

But

what do you do if, despite preventative pruning, your tomatoes begin to

show signs of late blight?

Rather than sticking your head in the sand the way we did last year,

your best bet is to take decisive action immediately. Single out

any tomatoes on which the blight has progressed beyond the very lowest

leaves and delete the entire plant. Then clip off any blighted

lower leaves on nearby plants.

During this extensive

pruning expedition, you should wipe your clippers with a rag soaked in

alcohol every time you move from one plant to another, or from a more

blighted area to a less blighted area. In addition, you shouldn't

even think about going into a blighted tomato patch when dew or rain

are heavy on the plants --- blight spores move around and germinate on

wet surfaces.

This

is also the one time I advocate removing biomass from the farm.

You should definitely not incorporate the blighted tomato residue into

your compost pile, but I feel that it's dicey to even toss it off into

the bushes at the edge of the woods. Instead, I actually let Mark

haul our blighted tomato parts away to the dump.

This

is also the one time I advocate removing biomass from the farm.

You should definitely not incorporate the blighted tomato residue into

your compost pile, but I feel that it's dicey to even toss it off into

the bushes at the edge of the woods. Instead, I actually let Mark

haul our blighted tomato parts away to the dump.

Finally, I take the

first sign of blight as a signal to get realistic. All of your

hard work pruning off diseased foliage is not going to cure your tomato

patch of the blight --- it will merely slowly the disease's

spread. You might be able to stay ahead of the blight for a while

by removing any yellow or brown leaves, but you'll have to stay

vigilant. So harvest while you can!

| This post is part of our Organic Tomato Blight Control lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

We

tried a new mulch source that has more down to Earth prices than The Mulch

Company... including a

sale on compost for just 10 bucks a scoop.

We

tried a new mulch source that has more down to Earth prices than The Mulch

Company... including a

sale on compost for just 10 bucks a scoop.

Don't get too excited. Their

"compost" was just aged wood chips mixed in with average looking dirt.

I still took 2 scoops because

I wanted to believe the lady at the desk when she said it was just

"pure aged wood chips", and I was a bit fatigued from following a map

that was not quite accurate on what may have been one of the hottest

days of the year.

I knew right away something

was amiss when Anna didn't get that same giddy laughter of joy I've

become so accustomed to when I bring truckloads of compost home.

"We can still use it for

areas in the forest garden where the clay doesn't drain well," she

said trying to make me feel better.

BFR Mulch in Norton has a

distorted definition of compost, but I guess it's a subjective term that

will vary from person to person. The stuff will make okay raised bed

material, but was barely worth hauling home when you gauge it on the

Anna meter.

They have aged oak mulch for

21 dollars a scoop, which is what we'll try next.

The

dry season makes for good conditions to catch up on some minor ford

maintenance.

The

dry season makes for good conditions to catch up on some minor ford

maintenance.

The do it

yourself cinder block ford hasn't really needed much repair in the

past 4 years. This turns out to be a low budget creek crossing

solution that continues to work.

During World War II, 40%

of American vegetables came from 20 million victory gardens. With

American men fighting abroad, women were raising their kids alone,

working outside the home (to fill those men's jobs), and still finding

time to till up their backyard and grow food for their families.

(Doesn't that make you

feel a bit silly for saying you don't have time to plant a

garden? There's still time to put in lettuce and greens for the fall, by the way.)

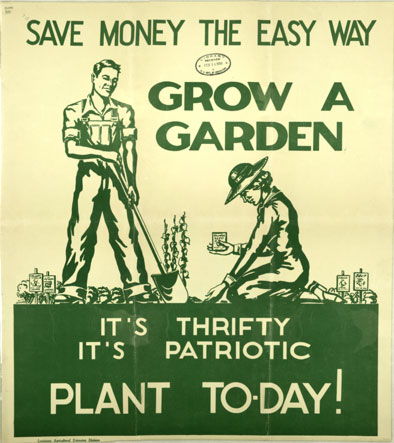

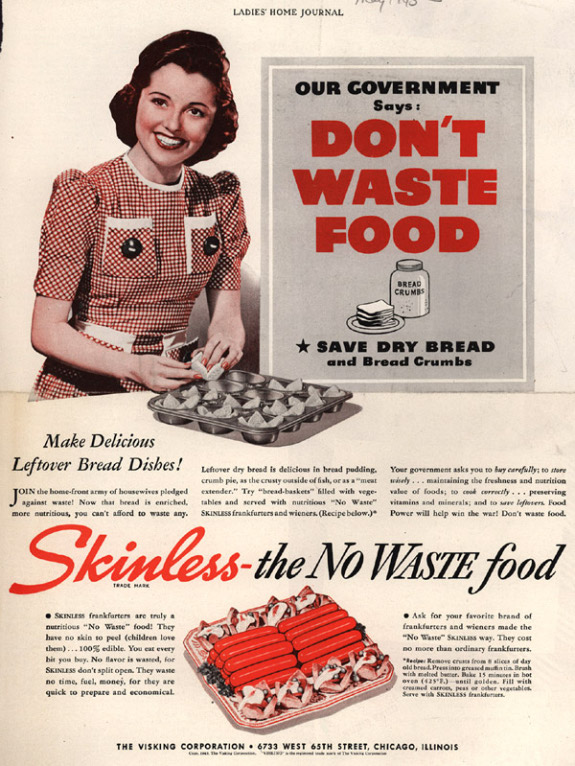

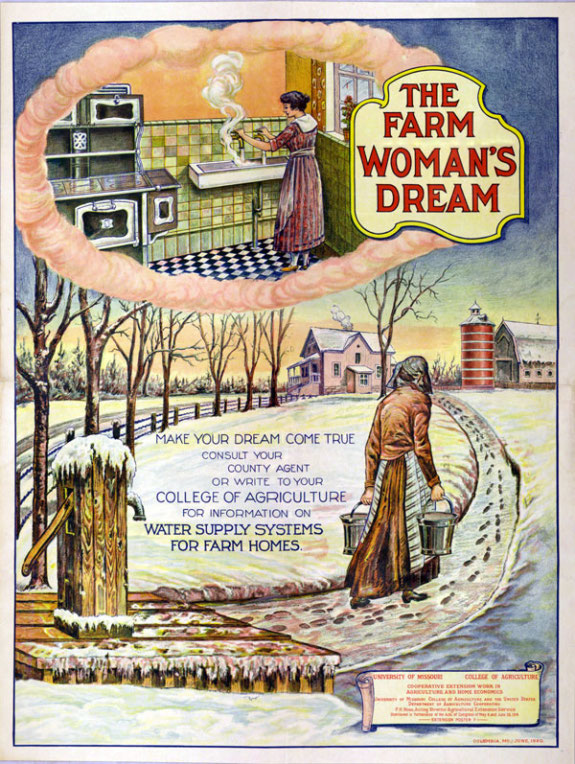

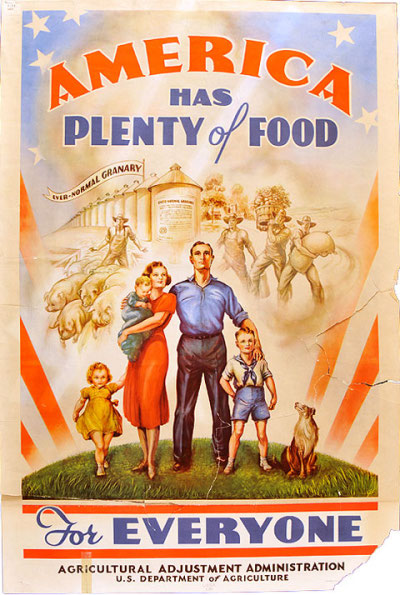

Posters like these from

both World Wars admonished women to plant a garden, can and dry the

excess, and never waste a crumb. The propaganda definitely worked

--- Americans ate potatoes instead of wheat so that the less perishable

grain could be sent abroad, and they generally managed to subsist on

what those remaining at home could grow.

As Sharon Astyk pointed

out in her fascinating

analysis of why and how we have been trained to believe that our

individual consumer choices make no difference to the world, victory gardens are clear

proof that your personal actions can have a worldwide impact.

Leading by example, you can even suck your friends and family into a

mode of eating that is lighter on the earth.

But

after the war ended, the propaganda took an abrupt about-face.

Suddenly, posters were telling us to buy, buy, buy! And, once

again, we followed along like sheep, dropped our shovels, and went out

to spend some money.

But

after the war ended, the propaganda took an abrupt about-face.

Suddenly, posters were telling us to buy, buy, buy! And, once

again, we followed along like sheep, dropped our shovels, and went out

to spend some money.

While I'm tempted to

talk here about our current government's admonitions to spend money to

prop up our ailing economy rather than striving to become more

self-sufficient, frugal, and debt-free on a personal level, I

won't. Instead, I think the takeaway message from the victory

garden campaign is clear --- think globally, act locally. If you

believe that the environment would benefit from food grown in an

ecologically conscious way, then look into permaculture and plant a

diversified garden. Anyone living anywhere can plant something,

preserve something, and cut back on food waste.

To see the source of

these posters (and peruse many more --- huge time sink, I warn you),

visit Beans

are Bullets, a

website/exhibition put together by the National Agricultural

Library.

The

agricultural extension websites are quick to tell you that no tomato

variety is immune to the blight, but I've discovered that several are

resistant. In general, tommy-toes

seem to fare quite well, losing the battle much later than the

larger-fruited varieties. On the other hand, the Green Zebra we

were testing for the first time this year turned out to be the most

blight-prone of any of our tomatoes --- we won't grow Green Zebra

again. So far, all of our other slicing tomatoes are faring

pretty well.

The

agricultural extension websites are quick to tell you that no tomato

variety is immune to the blight, but I've discovered that several are

resistant. In general, tommy-toes

seem to fare quite well, losing the battle much later than the

larger-fruited varieties. On the other hand, the Green Zebra we

were testing for the first time this year turned out to be the most

blight-prone of any of our tomatoes --- we won't grow Green Zebra

again. So far, all of our other slicing tomatoes are faring

pretty well.

The heart of our tomato

patch is our romas, and I'm starting to get a feel for which

roma varieties last longer when blight is in the air.

Large-fruited romas do the worst, and I don't think I'll even save

seeds from Italian San Rodorta this year since the plants blight so

quickly. In contrast, the even more hefty-fruited Russian Roma

plants are only barely blighted. Yellow Roma and Martino's Roma

are currently my roma winners --- the fruits are small, but they ripen

quickly and copiously, and the plants are blight-free so far.

I suspect that if I

tweaked my plantings to focus solely on the most blight-resistant

varieties, the fungus might not enter our patch until weeks

later. Or not at all?

| This post is part of our Organic Tomato Blight Control lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

Marcus Sabathil is a glass artist and furniture

maker who managed to modify

his Toyota Previa in such

a way to increase highway mileage from 20 to 36 mpg.

I've often wondered how much

of a gain we might get from our Toyota Previa if we fabricated a

similar boat tail.

While

weeding the mule garden this week, I discovered an unintentional

polyculture. I had pulled out all the seed potatoes from my fall

potato experiment because they weren't sprouting --- or so I

thought. It turns out that one potato was overlooked, and it

popped up between the leaves of a watermelon I'd planted at the end of

the bed.

While

weeding the mule garden this week, I discovered an unintentional

polyculture. I had pulled out all the seed potatoes from my fall

potato experiment because they weren't sprouting --- or so I

thought. It turns out that one potato was overlooked, and it

popped up between the leaves of a watermelon I'd planted at the end of

the bed.

Meanwhile, my primary

purpose for the bed was to plant fall carrots. I seeded three

different beds with carrots this summer, but very few seedlings

came up in two of the beds. However, in my polyculture bed, the

watermelon took off and ran across the carrot area, shading the soil

and retaining  enough moisture for the seeds to sprout.

All three

vegetables seem to be growing quite happily together so far, though I

recently

moved the watermelon tendrils aside to give the baby carrots room to

grow.

enough moisture for the seeds to sprout.

All three

vegetables seem to be growing quite happily together so far, though I

recently

moved the watermelon tendrils aside to give the baby carrots room to

grow.

In the interest of full

disclosure, I have to admit that the carrot seeds in the other beds may

have had shoddy germination rates because they were a different variety

than those sown in the polyculture bed. I usually have very good

luck with Jung's Sweetness hybrid carrots, but the pack this year seems

to have been a dud --- germination was low in our spring carrot bed

too. Next year, I might change my loyalties to one of the seed

companies recommended by Steve Solomon.

I

like to call step four in our campaign against the tomato blight

"tomato islands." While it's quite true that blight spores can

travel up to a mile in damp weather, planting patches of tomatoes in

different parts of the garden can be relatively effective in keeping

the blight from spreading if the summer stays hot and dry. So

while our romas (and a few slicers) are all clumped together along the

sunniest

edge of the mule garden, I've got slicing tomatoes and tommy-toes in

three other areas. The ones in the far-off front garden still

seem to be blight-free.

I

like to call step four in our campaign against the tomato blight

"tomato islands." While it's quite true that blight spores can

travel up to a mile in damp weather, planting patches of tomatoes in

different parts of the garden can be relatively effective in keeping

the blight from spreading if the summer stays hot and dry. So

while our romas (and a few slicers) are all clumped together along the

sunniest

edge of the mule garden, I've got slicing tomatoes and tommy-toes in

three other areas. The ones in the far-off front garden still

seem to be blight-free.

I'm also taking a page

out of our neighbor's book. Last year, while touring a friend's

garden at the end of the summer, I saw that he had a healthy tomato

plant still spitting out fruits. "How did you do that?!"

I exclaimed, and he told me that he'd thrown some seeds in the ground

in early June. This year I followed suit and seeded three more

tomato plants a couple of weeks after our frost-free date. These

late plants are starting to set fruits, and so far look pristine.

Perhaps they will give us a fall harvest?

| This post is part of our Organic Tomato Blight Control lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

I went back to BFR Mulch for two scoops of aged oak mulch

today.

It's an excellent product

that made Anna smile when she noticed the rich organic smell.

It was 21 bucks per scoop,

which is about half of what The Mulch

Company demands for

their mulch which is made from pine.

Our

back garden is a trouble spot. As I've mentioned before, previous

owners had a pasture there and I suspect allowed all of the topsoil to

erode away. What's left is dense clay over a high water table ---

a recipe for crop failure.

Our

back garden is a trouble spot. As I've mentioned before, previous

owners had a pasture there and I suspect allowed all of the topsoil to

erode away. What's left is dense clay over a high water table ---

a recipe for crop failure.

And then there are the

problems that are my own fault. When I built the back garden's raised

beds,

I believed it was best to merely scoop up the topsoil from the aisles

to create the beds. But there was so little topsoil present that

the beds turned out to be barely higher than the surrounding

aisles. A couple of years later, the beds have collapsed a bit

more,

which means that the grass and clover in the pathways encroach

constantly on the "beds", and grass seeds also drift up into the

growing area

as a matter of course. Yet more problems.

Again my fault --- I was

new to pathway planning when I laid out the

back garden, so for some reason I can no longer fathom, I created a

checkerboard of tiny beds. Mowing takes twice as long since you

have to go across the garden horizontally, then again vertically.

Yuck! Can you tell this is my least favorite gardening spot?

I took advantage of Mark's

load of topsoil (aka "compost")

to start fixing all of the back garden's problems. First step ---

merge all of the beds on a contour line into a single long bed by

dumping topsoil in the dividing aisles. Suddenly, I wanted two

more truckloads of soil so that I could also build up the empty beds

(which had been planted in buckwheat and are waiting to be planted in

oats next week.) My goal is to create a replica of my current

favorite garden --- the mule garden --- with long raised beds at least

six inches high. Then I could start to consider the high

groundwater a boon --- subirrigation!

The

final element of our tomato campaign is "never waste a tomato."

Mark and I completed our vine-ripened

versus indoor-ripened tomato taste test

last week, concluding that the former had just a hint of extra

flavor. Still, the kitchen-ripened tomatoes were ten times better

than storebought. So when I had to pull out three blighted tomato

plants last week, I first picked every tomato that had at least begun

to whiten and am now ripening them under the kitchen counter.

The

final element of our tomato campaign is "never waste a tomato."

Mark and I completed our vine-ripened

versus indoor-ripened tomato taste test

last week, concluding that the former had just a hint of extra

flavor. Still, the kitchen-ripened tomatoes were ten times better

than storebought. So when I had to pull out three blighted tomato

plants last week, I first picked every tomato that had at least begun

to whiten and am now ripening them under the kitchen counter.

Meanwhile,

fruits with a bit of blossom end rot or a cosmetic crack are fine additions to sauce

--- just slice off the troubled spot. On the other hand, our volunteer tomato

plant turned out not to be worth saving even under these drastic

conditions. I suspect the volunteer came from a storebought

tomato seed, because fully two thirds of the fruits that I left on the

vine to ripen rotted before turning red. I guess those hard, pink

tomatoes in the grocery store don't

ripen all the way, no matter what you do. That vine came out to

give more space to its neighbor.

Meanwhile,

fruits with a bit of blossom end rot or a cosmetic crack are fine additions to sauce

--- just slice off the troubled spot. On the other hand, our volunteer tomato

plant turned out not to be worth saving even under these drastic

conditions. I suspect the volunteer came from a storebought

tomato seed, because fully two thirds of the fruits that I left on the

vine to ripen rotted before turning red. I guess those hard, pink

tomatoes in the grocery store don't

ripen all the way, no matter what you do. That vine came out to

give more space to its neighbor.

| This post is part of our Organic Tomato Blight Control lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

My last trip to BFR

Mulch in Norton gave me a chance to ask the guy about delivery

options.

It seems they have a small

Mitsubishi 4 wheel drive dump truck that can haul 5 times what we can

do in the truck. The delivery fee is 30 dollars from Norton to Coeburn, which

is about the half way mark for us and why the guy guessed the charge to

be around 60 bucks for our zipcode.

I've

been putting a lot of thought lately into how we invest the fruits of

our labors. A decade ago, I read a basic investment book that

told me to put 10% of my income in a mutual fund for retirement, and

I've been following along like a sheep ever since.

I've

been putting a lot of thought lately into how we invest the fruits of

our labors. A decade ago, I read a basic investment book that

told me to put 10% of my income in a mutual fund for retirement, and

I've been following along like a sheep ever since.

But investing in a

combination of stocks and bonds means that I believe in a growth economy. Do I? I

certainly don't believe a growth economy is good, and I'm not so sure

that I believe our economy will grow over the next forty years.

On the other hand, I

don't really believe in apocalyptic scenarios either, so I don't plan

to invest in gold. (As Mark pointed out, coins worth over a

thousand dollars apiece are unlikely to be terribly useful in an

apocalyptic scenario anyway.) I'm guessing social security will

be around when I retire, but may only pay out half of what my

statements tell me to expect. Perhaps our best bet is to put our

dribs and drabs of retirement money in some combination of ultra-safe

investments (like CDs) and into farm infrastructure to make our annual

operating costs lower.

I'm curious to hear our

readers' take on investment in today's climate. Do you stick to

the rosy view that the economy will rebound, meaning that social

security will fulfill most of your needs and you'll round out your

retirement income with some sort of mutual fund? Or do you think

society as we know it will collapse and social security will be

completely absent, so you'd better stock up on firearms? I'm most

curious to hear from folks who think the future will be somewhere in

the middle --- how do you invest for your old age?

Big thanks go out to Travis and

Kacy for the nice

post they wrote about us.

They're still on the cross

country journey and have visited about 90 farming types.

I'm looking forward to

reading their book about these travels which now has a working title of

"Stewards: Stories and Perspectives From American Farmers".

"Lucy,

where did you find a brand new tennis

ball?" I asked our frugivorous dog, catching sight of a yellowish

sphere in her mouth. She dropped...the first peach from our kitchen

window peach tree.

Then promptly gulped it down, pit and all.

"Lucy,

where did you find a brand new tennis

ball?" I asked our frugivorous dog, catching sight of a yellowish

sphere in her mouth. She dropped...the first peach from our kitchen

window peach tree.

Then promptly gulped it down, pit and all.

I had smelled the scent

of ripe fruit wafting from the tree as I walked

past earlier that morning, but I was so sure the peaches weren't

ripe. You see, I had planted a Loring peach in that spot three

years ago --- a

yellow-fruited variety with a nice red blush on the skin. And the

fruits on my tree were steadfastly pale yellow with white flesh.

But Lucy likes her fruit

ripe, so I went back to check again. Sure

enough, the peaches were just barely starting to ripen, even though the

flesh was pale as can be. What's the statute of limitations on

complaining about being given the wrong tree variety?

The trouble is, I adore

yellow peaches, while white peaches are

considerably lower on the totem pole --- like the difference between

strawberries and blackberries. Luckily, I have another peach tree

out back that's one year younger but already gave me four little

peaches with great flavor and bright orange flesh. By next year,

I should be glutted with yellow peaches. But what to do in the

meantime? Perhaps I need to check out some recipes for peach

leather? Now's your chance to shower us with your favorite peach

recipes.

The new

tomato support structure is helping our plants reach towards the

sky.

The new

tomato support structure is helping our plants reach towards the

sky.

This one is already over 7

feet tall, which might require a step ladder to harvest the ones up

high.

The Master Gardeners of Santa

Clara County in California evaluated

11 different ways to support tomatos and summed up the pros and

cons of each in an easy to read report from 2001.

They used just over 100

varieties of mostly heirloom tomatos to finally get to the bottom of

which system works the best.

Perhaps

in other parts of the world, it's not considered abnormally dry when

you've had a steady one inch of rain per week for most of the

summer? Around here it sure feels dry, though, after a month with

abnormal highs in the nineties nearly every day. The floodplain has dried up, meaning that

even though there are puddles of water in the driveway, the ground

between is hard rather than mud. Perfect weather for hauling.

Perhaps

in other parts of the world, it's not considered abnormally dry when

you've had a steady one inch of rain per week for most of the

summer? Around here it sure feels dry, though, after a month with

abnormal highs in the nineties nearly every day. The floodplain has dried up, meaning that

even though there are puddles of water in the driveway, the ground

between is hard rather than mud. Perfect weather for hauling.

Last winter, when we

were trying to ferry in building supplies through endless muck, Titus

gently noted that she tries to do all of her hauling during the dry

season. So when we realized the driveway was firm enough to allow

Joey's truck to pass through, we dropped everything from the list and

instead focused on ferrying supplies into the farm. That's why

Mark went to town nearly every day last week, hauling in compost and mulch. It wasn't photogenic

enough to post about, but he also hauled out a year's

supply of household garbage --- a truckload and a half

full.

We hope to finish

bringing in the year's supply of biomass this week, and also cut up and

haul in firewood from deadfall trees along the driveway. Round it

all out with some lumber for the solar dehydrator and picnic table

projects, and we should be done hauling for a long, long time. I

just thought you all deserved an explanation so that you didn't think

we were on a crazy spending spree.

This round of firewood

cutting reminded me of a saying my uncle Art once told me.

I think I've cheated myself

out of one

of the warmings by cutting on a day like today, but I think it's

still worth the effort nonetheless.

"Look

at all the butternuts I harvested,

honey!" I said proudly. "And we've got four more left in the

garden."

"Look

at all the butternuts I harvested,

honey!" I said proudly. "And we've got four more left in the

garden."

Mark glanced over at my

22 pounds of butternuts and replied --- "Four

more baskets?" Shame-faced, I had to shake my head no. I

only had four more squash in the garden.

The truth is that when I

planned our three butternut beds this year, I

should have realized that Mark had turned a general preference for

these winter squash into an outright craving. Already, he's

talking about buying some butternuts from a friend, and he has the

right idea. Now's the perfect time of year to stock up on any

vegetables of which you have an unexpected shortfall (or ones that your

husband suddenly decides he adores and wants three times as

many of.)

If

you planted your butternuts a bit late (which would have been

smart), they might not be ready to harvest yet. Wait until your

vines are dying back, your fruits are fully tan, and the stems have

begun to brown (but be absolutely certain to harvest before the first

frost.) Then carefully cut each butternut off the vine, leaving

an inch of stem on the fruit. Never toss the butternuts around

--- even though they look hardy, they actually bruise quite quickly if

treated harshly.

If

you planted your butternuts a bit late (which would have been

smart), they might not be ready to harvest yet. Wait until your

vines are dying back, your fruits are fully tan, and the stems have

begun to brown (but be absolutely certain to harvest before the first

frost.) Then carefully cut each butternut off the vine, leaving

an inch of stem on the fruit. Never toss the butternuts around

--- even though they look hardy, they actually bruise quite quickly if

treated harshly.

Some people wash their

butternuts gently in a solution of bleach water

after harvesting to kill off any fungi living on the skin, but I've had

good luck storing our butternuts as is. For best flavor, allow

the squash to cure at 80 to 85 degrees Fahrenheit for a couple of

weeks, then store in a cool (50 to 60 F), dry place. We keep our

butternuts in a kitchen cabinet and eat them until the middle of the

winter...or until we run out.

When we first started off

clearing away the driveway we were using a very small pruning chainsaw

because we didn't know any better and funds were limited.

We finally realized the

limitations and decided to splurge for a bigger saw. We found a good

deal on a much bigger chainsaw through E-bay, and used it to finish

clearing the path.

It's a Stihl 039, or what they call a 390 these

days. A fine machine, but after it's all said and done I think we would

have been better off with a smaller one. It gets real heavy real fast,

especially after you've been cutting for a while.

After

extracting four and a

half gallons of honey from our hives, I proceeded to ignore them

for over a month. We had more pressing matters on our plate (like

killing

all of our broilers),

and I figured, what could go wrong now that we've taken out a lot of

honey and the hives are all built up to summer levels? I should

have known that I had more beginner mistakes ahead of me.

After

extracting four and a

half gallons of honey from our hives, I proceeded to ignore them

for over a month. We had more pressing matters on our plate (like

killing

all of our broilers),

and I figured, what could go wrong now that we've taken out a lot of

honey and the hives are all built up to summer levels? I should

have known that I had more beginner mistakes ahead of me.

When I opened up the

east hive on Tuesday, everything looked fine in the top super.

But the next level down was a disaster. Every frame (most of them

at least half full of honey)  had

collapsed under this summer's extreme heat, turning horizontal so that

they blocked the flow of air out of the hive. Small surprise that

the next level down was completely collapsed as well. Only the

lowest brood box (thank goodness!) still had vertical frames of wax.

had

collapsed under this summer's extreme heat, turning horizontal so that

they blocked the flow of air out of the hive. Small surprise that

the next level down was completely collapsed as well. Only the

lowest brood box (thank goodness!) still had vertical frames of wax.

The honey was mostly

uncapped, so I couldn't extract it. Instead, I yanked out all of

the trouble frames and carted them over to an out of the way spot in

the forest garden, figuring the bees would clean out the honey and pack

it away in the remaining, uncollapsed frames. Granted, the

strongest hive quickly found this bounty and joined in the feast, so I

will probably have to equalize honey between the hives at a later date,

adding a super of honey from elsewhere onto the east hive to make up

for the collapsed frames I removed.

What

did I learn from this beginner mistake? First of all, I should

have propped the hive lids up with small sticks to accelerate air flow

as soon as I saw bees "bearding" (sitting on the side of the box and

fanning their wings.) I think I also should have left the supers

at ten frames per box for a week or so after

harvesting the honey so that the bees could firm back up the wax

damaged by the extraction process before filling it up with so much

honey.

What

did I learn from this beginner mistake? First of all, I should

have propped the hive lids up with small sticks to accelerate air flow

as soon as I saw bees "bearding" (sitting on the side of the box and

fanning their wings.) I think I also should have left the supers

at ten frames per box for a week or so after

harvesting the honey so that the bees could firm back up the wax

damaged by the extraction process before filling it up with so much

honey.

Finally, I definitely

should have checked on the hive a week or two after extraction.

I've read that collapses domino through the hive if left in place,

since the horizontal frames from the first collapse make the hive heat

up further. If I'd caught the collapse in its early stages,

chances are I could have prevented the large scale catastrophe.

The BFR

Mulch guy called this

morning saying he could only deliver us 6 scoops of

compost instead of the 9

that was mentioned last week due to the dump mechanism not being able

to handle the extra weight.

I was thinking it was still a

good deal that would save me from making 3 round trips to Norton. Add

the travel time with the time to unload each load and it equals up to

somewhere over a day's worth of labor. The delivery charge was going to

be 75 dollars.

I was very clear on the phone

that I needed them to cross a creek and requested the 4 wheel drive

Mitsubishi Fuso dump truck by name.

They made it as far as our

ford when they had to

stop and give up. It seems like someone decided to add a snow plow

attachment that shrinks the clearance down to a paltry 8 or 10 inchs!

I can see how they would want

to take advantage of this 4 wheel drive beast in the winter by pushing

snow, but why not install it so that you could unbolt it for the

summer? It was welded on and the only obstacle to getting the load back

to our garden.

I almost had them dump the

load out by our parking area, but decided that would be even more work

loading back on the truck and then unloading it at the garden.

The driver was a nice guy and

apologetic about the handicapped truck.

"I guess most people don't

live this far back in the woods anymore these days?" I asked the guy

while we puzzled over the problem at the creek.

I felt bad about sending him

back with the full load, but even felt worse over the wasted morning

with nothing to show for it. This still seems to be a good option for

mulch and compost delivery, just don't expect them to go up any sort of

hill or over a big bump.

Half

of you are going to find this post ludicrously basic, but I suspect the

other half of you never learned the facts of life from your

mother. Paper towels seem to be the last bastion

of consumer society found in many homesteaders' households, but the

truth is that you already have a free alternative --- rags.

Half

of you are going to find this post ludicrously basic, but I suspect the

other half of you never learned the facts of life from your

mother. Paper towels seem to be the last bastion

of consumer society found in many homesteaders' households, but the

truth is that you already have a free alternative --- rags.

How

to make rags

The first step in making

rags is wearing your clothes into the ground. After a certain

point, there's no purpose in mending a piece of clothing --- the fabric

has degraded so much that it will merely rip along your mended

seam. Or maybe your t-shirt now has half a dozen holes that seem

to get bigger every day. Put it in the rag bag.

Once

a year or so, I get around to pulling out the rag bag and taking a

look. First, I sort my old clothes into three piles --- 100%

cotton, partially synthetic, and fully synthetic or bulky. The

last category doesn't have much use on our homestead, so we tend to

relegate it to winter pet bedding, but all of the others will be

used. We turn 100% cotton clothes into fodder for my bees'

smoker, and everything else becomes rags. Underwear and t-shirts

make the best smoker fodder and rags, and luckily they're the pieces of

clothing that wear out the quickest.

Once

a year or so, I get around to pulling out the rag bag and taking a

look. First, I sort my old clothes into three piles --- 100%

cotton, partially synthetic, and fully synthetic or bulky. The

last category doesn't have much use on our homestead, so we tend to

relegate it to winter pet bedding, but all of the others will be

used. We turn 100% cotton clothes into fodder for my bees'

smoker, and everything else becomes rags. Underwear and t-shirts

make the best smoker fodder and rags, and luckily they're the pieces of

clothing that wear out the quickest.

Making rags is

simple. Just cut through any turned-under edges, then

riiiiiiiip. (Rag production is also a great way to improve your

mood if you're down in the dumps --- so satisfying.) It's best to

tear off and discard underwear waistbands and t-shirt collars, but

otherwise there are no rules. Just be sure to end up with rags

roughly eight inches by eight inches.

How to use rags

How to use rags

Now, how do you use

rags? The first line of defense in our household is the wash

cloth. These storebought items (costing perhaps a quarter apiece

at the dollar store) will last years as long as you use them for gentle

cleaning like doing dishes and wiping down counters. I only pull

out rags when I'm going to be working in more goopy or disgusting

situations, like wiping oil off a machine or cleaning up fecal matter.

What do you do with a dirty

rag? If it's not too filthy, rinse it out in the sink, then drape

it over the side of the laundry basket to dry. Rags can then be

washed with your regular laundry. On the other hand, we reserve

the right to throw rags away if they're too awful --- that's why we use

them for the more disgusting tasks that would retire a wash cloth.

What do you do with a dirty

rag? If it's not too filthy, rinse it out in the sink, then drape

it over the side of the laundry basket to dry. Rags can then be

washed with your regular laundry. On the other hand, we reserve

the right to throw rags away if they're too awful --- that's why we use

them for the more disgusting tasks that would retire a wash cloth.

We tend to go through

rags at just about exactly the same rate we go through clothes.

You're probably discarding your clothing too soon and buying too much

of it if you're overrun with rags.

For those of you who

were raised using rags, I'm curious to hear what you'd add to my rag

tutorial. Any helpful tips for the uninitiated? Any uses

for those bulky blue jeans and fleece shirts?

Youtube

user clintfisher has created what I would call the most

sophistitcated automatic chicken coop door opener I've seen so far.

Youtube

user clintfisher has created what I would call the most

sophistitcated automatic chicken coop door opener I've seen so far.

It uses Arduino technology

that allows for wireless control and will be powered by a solar cell

that charges a small 12 volt battery.

The locking mechanism is

impressive and he makes use of an old battery powered drill for the

motor action.

I doubt if there's any

racoons out there smart enough to get through this level of security.

Edited to add:

After years of research, Mark eventually settled on this automatic chicken door.

You can see

a summary of the best

chicken door alternatives and why he chose this version here.

If you're planning on

automating your coop, don't forget to pick up one of our chicken waterers. They never spill or

fill with poop, and if done right, can only need filling every few days

or weeks!

Last

year, oilseed

sunflowers were an

experimental crop for us, so of course the deer ate them and we didn't

have any seeds to harvest. Deer aren't so interested in the

sunflowers this year, preferring to nibble our experimental

beans, so I've been

thrilled to watch these low-work vegetables do their thing. The

plants quickly shot up above my head, opened huge yellow flowers, and

then dropped the petals as the seeds swelled up and the heads drooped

under their own weight.

Last

year, oilseed

sunflowers were an

experimental crop for us, so of course the deer ate them and we didn't

have any seeds to harvest. Deer aren't so interested in the

sunflowers this year, preferring to nibble our experimental

beans, so I've been

thrilled to watch these low-work vegetables do their thing. The

plants quickly shot up above my head, opened huge yellow flowers, and

then dropped the petals as the seeds swelled up and the heads drooped

under their own weight.

Some people advocate

leaving sunflowers to dry in the field, but I know for a fact that our

local wildlife would consider that a "free lunch" sign. So as

soon as the backs of the flower heads began to yellow and the tiny

yellow disc flowers in the center of the "flower" easily rubbed off the

black seeds, I snipped the tops off the sunflower stalks and hung them

to dry under the porch eaves.

The

harvest came not a moment too soon. As I worked, a brilliant

yellow goldfinch flew to one of the headless stalks and chittered at

me. "Hey, no fair! I was counting on that to feed my

family!" A couple of hours later, he'd gathered his wife and

brothers to peck seeds out of the drying heads, so I had to cover the

whole mass with row cover fabric. I hope he isn't bright enough

to slip up underneath the fabric, but even so I'm considering rubbing

the seeds out of the heads ASAP and putting them in a sealed container.

The

harvest came not a moment too soon. As I worked, a brilliant

yellow goldfinch flew to one of the headless stalks and chittered at

me. "Hey, no fair! I was counting on that to feed my

family!" A couple of hours later, he'd gathered his wife and

brothers to peck seeds out of the drying heads, so I had to cover the

whole mass with row cover fabric. I hope he isn't bright enough

to slip up underneath the fabric, but even so I'm considering rubbing

the seeds out of the heads ASAP and putting them in a sealed container.

If I get my act together

and buy or make an oil press, I'll let you all know how much oil you

get out of two beds of sunflowers. Or maybe I'll just save them

and feed

the high protein sunflower seeds to the chickens.

It would be great if all the

downed trees would fall like this one.

Being elevated off the ground

makes it so much easier to cut and avoid letting the chain dip into the

dirt, not to mention being safer.

I start at the far end and

just let each log fall to the ground, and then let Anna load them up in

the truck.

After

carefully

snipping butternuts off the vine and felling

towering sunflowers with a single blow, it was time to harvest our experimental

beans. First

came the garbanzos --- aren't they lovely? The only problem is

that what you see in this photo is nearly the entire harvest. I'm

not giving up on the variety, though, since a reader commented a few

months ago to let me know that the extremely confusing instructions on

the seed packet were really trying to tell me to plant

the garbanzos at the same time as peas. I planted them at the

frost free date instead, so I'll have to give the crop a more fair shot

next year.

After

carefully

snipping butternuts off the vine and felling

towering sunflowers with a single blow, it was time to harvest our experimental

beans. First

came the garbanzos --- aren't they lovely? The only problem is

that what you see in this photo is nearly the entire harvest. I'm

not giving up on the variety, though, since a reader commented a few

months ago to let me know that the extremely confusing instructions on

the seed packet were really trying to tell me to plant

the garbanzos at the same time as peas. I planted them at the

frost free date instead, so I'll have to give the crop a more fair shot

next year.

Next

stop "shelly beans", as folks around here like to call beans that you

grow for drying. The harvest in this bed was much better, despite

the fact that bean bugs ate the plants down to nubbins...then moved on

to my delightful Masai beans. I'm tempted to blame

the arrival of this new garden pest on the shelly beans, but I suspect

that it just took the beetles a few years to find us. Next year,

I'll add the Mexican Bean Beetle to my list of bad bugs to squash

weekly, and maybe all of our beans will do better.

Next

stop "shelly beans", as folks around here like to call beans that you

grow for drying. The harvest in this bed was much better, despite

the fact that bean bugs ate the plants down to nubbins...then moved on

to my delightful Masai beans. I'm tempted to blame

the arrival of this new garden pest on the shelly beans, but I suspect

that it just took the beetles a few years to find us. Next year,

I'll add the Mexican Bean Beetle to my list of bad bugs to squash

weekly, and maybe all of our beans will do better.

Although

the quantity of pods from the shelly bean bed was good, I discovered

that I should have picked the drying beans much sooner. Many

people leave beans for drying to harden on the plant, but our climate

is just too damp for that sort of harvest. By the time I picked

them, many of the older pods had begun to mold, and over half of the

beans were discolored. Next year, I'll harvest the beans when the

pods are still slightly green, then allow them to dry inside, out of the

weather.

Although

the quantity of pods from the shelly bean bed was good, I discovered

that I should have picked the drying beans much sooner. Many

people leave beans for drying to harden on the plant, but our climate

is just too damp for that sort of harvest. By the time I picked

them, many of the older pods had begun to mold, and over half of the

beans were discolored. Next year, I'll harvest the beans when the

pods are still slightly green, then allow them to dry inside, out of the

weather.

Finally,

I came to our Urd Beans (a variety of sprouting bean.) I thought

this bed was a goner after the deer nibbled it nearly down to the

ground...then repeated the maneuver a week later. But the Urd

Beans have a saving grace --- bean bugs don't like them. Despite

the name "Bean", Urd Beans are in an entirely different genus than Phaseolus

vulgaris (which

includes green beans and the green-bean-like shelling beans I

planted.) Instead, Urd Beans (Vigna

mungo) are in the

same genus as black-eyed peas, a group that seems to be of little

interest to our current crop pest.

Finally,

I came to our Urd Beans (a variety of sprouting bean.) I thought

this bed was a goner after the deer nibbled it nearly down to the

ground...then repeated the maneuver a week later. But the Urd

Beans have a saving grace --- bean bugs don't like them. Despite

the name "Bean", Urd Beans are in an entirely different genus than Phaseolus

vulgaris (which

includes green beans and the green-bean-like shelling beans I

planted.) Instead, Urd Beans (Vigna

mungo) are in the

same genus as black-eyed peas, a group that seems to be of little

interest to our current crop pest.

I

was also pleased to see that Urd Bean pods are hairy, a feature that

seems to repel moisture, keeping the seeds inside dry even after the

pods turn black. I harvested half of the pods, leaving the green

fruits on the vine to be picked at a later date. The only problem

I foresee with Urd Beans so far is their size --- shelling these little

guys by hand would take all day. (For a sense of scale, that's my

thumbnail on the left side of the first picture of urd beans.)

I'm hopeful, though, that after I let the pods dry for a week or two,

they'll be brittle enough that I can thresh them and then blow the

empty pods off the seeds.

I

was also pleased to see that Urd Bean pods are hairy, a feature that

seems to repel moisture, keeping the seeds inside dry even after the

pods turn black. I harvested half of the pods, leaving the green

fruits on the vine to be picked at a later date. The only problem

I foresee with Urd Beans so far is their size --- shelling these little

guys by hand would take all day. (For a sense of scale, that's my

thumbnail on the left side of the first picture of urd beans.)

I'm hopeful, though, that after I let the pods dry for a week or two,

they'll be brittle enough that I can thresh them and then blow the

empty pods off the seeds.

So, to sum up what

became far too long of a post --- garbanzos need to be planted in early

spring, shelly beans need to be harvested before the pods turn brown,

and Urd Beans are my new favorite experimental bean.

Saturday night in small town

America shot about an hour ago.

Our peach tree had another surprise

in store for me. I chomped down on one of its luscious

fruits...and spit that bite right back out, along with the maggot

happily consuming the peach's center. Yes, nearly every one of

our peaches has a little blob of gum on the outside marking the

entrance path of these little, white larvae.

Our peach tree had another surprise

in store for me. I chomped down on one of its luscious

fruits...and spit that bite right back out, along with the maggot

happily consuming the peach's center. Yes, nearly every one of

our peaches has a little blob of gum on the outside marking the

entrance path of these little, white larvae.

The first step in

combatting any insect infestation is figuring out

what you've got, but I had quite a time identifying my maggot. My

handy Garden Insects of North

America narrowed

down the  playing

field

to a mere score of "fruit chewers": plum curculio, plum gouger, cherry

curculio, speckled green fruit worm, peach twig borer, eyespotted bud

moth, oriental fruit moth, navel orangeworm, lesser appleworm, cherry

fruit-worm, mineola moth, cherry fruit sawfly, apple maggot, walnut

husk fly, cherry fruit fly, western cherry fruit fly, black cherry

fruit fly, chokecherry gall midge, European earwig, or green fruit

beetles.

playing

field

to a mere score of "fruit chewers": plum curculio, plum gouger, cherry

curculio, speckled green fruit worm, peach twig borer, eyespotted bud

moth, oriental fruit moth, navel orangeworm, lesser appleworm, cherry

fruit-worm, mineola moth, cherry fruit sawfly, apple maggot, walnut

husk fly, cherry fruit fly, western cherry fruit fly, black cherry

fruit fly, chokecherry gall midge, European earwig, or green fruit

beetles.

An expert at Bug Guide took a look and gave me a

tentative ID of

coddling moth or oriental fruit moth, the latter of which is more

likely as a pest of peaches. Although most of the mainstream

websites tell me to spray chemicals on my tree, an Australian

site

recommends running chickens in the orchard. I wonder if putting

up a temporary fence around our peach trees and running chickens inside

during critical periods in the spring and fall would be sufficient to

cut down on our peach damage?

That Australian site

(which I am thoroughly impressed by) also suggested some other

permaculture style control measures for the oriental fruit moth. My

favorite involves taking advantage of the fact that the moth goes

through several generations in a year. Before the fruit are

large, the larvae instead grow inside twigs, which are highly visible

because they wilt and produce gum. By cutting off and destroying

these infested twigs in the spring, you  can

cut back the population, which means there won't be adults present to

lay eggs on your precious peaches.

can

cut back the population, which means there won't be adults present to

lay eggs on your precious peaches.

A final method of

control involves putting out artificial pheremones around the

tree. These pheremones mimic the scent emitted by the female moth

when she's trying to attract a mate, so they disrupt the moths' mating

behavior. At four pheremone ties per tree, replaced twice a year,

though, this method could add up.

Despite the problematic

centers, our white peaches are growing on

me. I cut them in half and scoop out the bad spots, then gulp

down half a dozen a day. Now that they're at their peak of

ripeness, I've discovered I prefer homegrown white peaches to

storebought yellow peaches!

I managed to supplement our butternut

squash supply by about 35 various sized beauties grown by a friend

of mine for the grand total of 20 dollars.

I also talked him out of this

nice cedar table for an extra 50 bucks.

Step

1: Call up Mom.

There's a knack to cutting up wormy fruit, and chances are your

maternal helper will make the work go three times as fast. Bribe

her with less wormy peaches and other garden produce.

Step

1: Call up Mom.

There's a knack to cutting up wormy fruit, and chances are your

maternal helper will make the work go three times as fast. Bribe

her with less wormy peaches and other garden produce.

Step

2: Prepare the peaches.

Unless you bought your peaches from a commerical orchard, chances are

they need some bad spots cut out. Our peaches are the worst case

scenario since our oriental

fruit moth infestation

means that over half the fruits had rotten,

wormy centers. The quick and easy way to deal with troubled fruit

is to cut them in half and scoop out the rotten centers with a

spoon. Slice off the skin last in this case, or first if your

peaches are pristine.

Step 3: Puree the raw peaches in a

food processor.

Step 3: Puree the raw peaches in a

food processor.

Step

4: Add honey to

taste. Honey gives the finished leather pliancy and helps

preserve the peach puree as

it dries. We added almost a cup of honey to about a gallon of

fruit puree --- use your own judgement here.

Step

5: Pour the puree and honey

mixture onto cookie sheets. The official method of

making

fruit leather involves spreading your puree on skins of saran wrap, but

we don't  keep that kind of disposable

in the house. Cookie sheets

work fine as long as you don't mind your finished leather

getting bent

out of shape for storage.

keep that kind of disposable

in the house. Cookie sheets

work fine as long as you don't mind your finished leather

getting bent

out of shape for storage.

Step

6: Spread the puree to about 1/8

inch thick.

At first, we tried spreading the peach mush

with spoons and butter knives, then Mom had the great idea of just

jiggling the pan. The moist peach mixture quickly settled out

across the entire surface.

Step 7: Dry the fruit leather as quickly as

possible.

We haven't built our solar

dehydrator yet, so

last time I dried our fruit leather by moving it between our

east-facing sunny window (in the morning) and our west-facing sunny

window (in the afternoon.) Mom had the great idea of drying the

leather inside Joey's truck, which seems to be working even

better. You need hot temperatures around 100 F or higher to dry

the leather before it ferments and molds. Maximum drying time

should not exceed two and a half days.

Step 7: Dry the fruit leather as quickly as

possible.

We haven't built our solar

dehydrator yet, so

last time I dried our fruit leather by moving it between our

east-facing sunny window (in the morning) and our west-facing sunny

window (in the afternoon.) Mom had the great idea of drying the

leather inside Joey's truck, which seems to be working even

better. You need hot temperatures around 100 F or higher to dry

the leather before it ferments and molds. Maximum drying time

should not exceed two and a half days.

Step 8: Scrape the fruit leather off

the trays with a spatula. Depending on how much

moisture is left in your leather, it may peel off, or rumple up as

shown in my

pictures. I prefer the slightly wetter leather even though it's

less pretty.

Step 8: Scrape the fruit leather off

the trays with a spatula. Depending on how much

moisture is left in your leather, it may peel off, or rumple up as

shown in my

pictures. I prefer the slightly wetter leather even though it's

less pretty.

Step

9: Store your peach leather.

Fruit leather will last at room temperature for about a month, but I'm

planning to use the peaches as a supplement to our winter fruit.

In the freezer, fruit leather should last about a year.

The bad thing about procrastinating on mowing is once the "lawn" gets

so high I can't run the mulch machine with the bag due to it bogging

down.

It's much more powerful once

you take the bag attachment off, but still has its limits.

The

good news is that closer inspection of our tomatoes shows they are

infected with early blight, not late blight. Notice the yellowing

of the leaves and (not pictured) the absence of problems on the stems

and fruits. Although both are fungal diseases, early blight tends

to be less devastating, and I'm having very good luck keeping the

fungus in check with my

blight control measures.

The

good news is that closer inspection of our tomatoes shows they are

infected with early blight, not late blight. Notice the yellowing

of the leaves and (not pictured) the absence of problems on the stems

and fruits. Although both are fungal diseases, early blight tends

to be less devastating, and I'm having very good luck keeping the

fungus in check with my

blight control measures.

The bad news is that

early blight tends to stick around after it shows up. Unlike late

blight, which needs living tissue to survive, early blight can

overwinter in plant debris or even in saved seeds. Although it

pains me to remove biomass from the farm, we'll continue to take our

blighted leaves to the dump.

This week, I ripped out

another three tomato plants that showed too much damage to save.

But I can't complain, since the tomatoes have been pouring in.

Here's our August 6 harvest:

Then skip ahead a few

days to August 10, and you'll notice I had to upgrade to the bigger

basket:

No photos of the next

few harvests, but suffice it to say that I'm now harvesting large

masses of tomatoes three times a week. We've already frozen a

gallon of pizza sauce and three quarts each of spaghetti sauce and

tomato-based vegetable soup. When the peach

leather comes out of

the automotive dehydrator today, I plan to replace the fruit with a

batch of sun-dried tomatoes.

sk1ppy14 from somewhere in

the United Kingdom has done a fine job fabricating this automatic

chicken coop door closer/opener from an old gate opener.

These medium sized gate

openers will sometimes get weak over years of heavy usage and require

replacement. What a great way to extend the usefulness of this farm

gadget.

Edited to add:

After years of research, Mark eventually settled on this automatic chicken door.

You can see

a summary of the best

chicken door alternatives and why he chose this version here.

If you're planning on

automating your coop, don't forget to pick up one of our chicken waterers. They never spill or

fill with poop, and if done right, can only need filling every few days

or weeks!

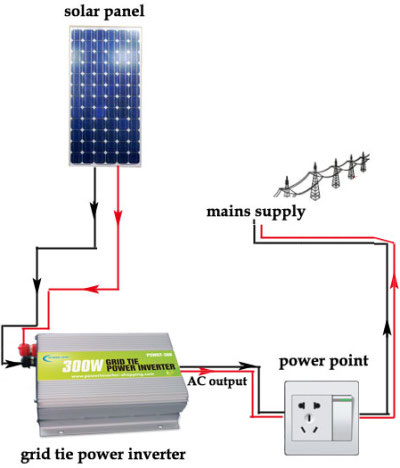

We still think that plug

and play is the way

to go for our cheap

solar backup, but

we've tweaked the specific components a

bit. We wanted to find a powerpack that we could pick up at a

physical store since powerpacks bought online have often been stored in

warehouses for years and have dubious longevity. We figure that

by picking one up locally, we can easily return it if it turns out to

be old.

The

5-in-1 power pack at Harbor Freight is the best we

could find at a physical store --- it's only two thirds as voluminous

as the Duracell 600 watt power pack, holding 216 watt-hours of energy,

but the price commensurate. And the reviews are quite good ---

one user notes that his powerpack is only starting to lose its gumption

after five years of use.

The

5-in-1 power pack at Harbor Freight is the best we

could find at a physical store --- it's only two thirds as voluminous

as the Duracell 600 watt power pack, holding 216 watt-hours of energy,

but the price commensurate. And the reviews are quite good ---

one user notes that his powerpack is only starting to lose its gumption

after five years of use.

The 45 watt solar panel kit is really too big for our system, but it's

irresistible at the current sale price ($170 on Harbor Freight's

website --- print out the price page to use as a coupon at local

stores.) Since we've oversized our solar panel, we have to throw

in a $26 charge controller, bringing the total cost to just under $300

for the entire backup system.

On a sunny, summer day, our 45 watt solar panel will probably be

wasting quite a bit of juice, since it should pull in 135 watt-hours of

energy a day even in the dead of winter. I suspect that there

will be a way to capture that excess, perhaps by plugging an inverter

directly into the included power center to run electronics while also

charging the powerpack. Or, better yet, we might buy a (roughly)

$100 grid tie inverter, which would allow us to plug our solar panel

directly into an electric socket in the house and sell power back to

the grid --- no muss, no fuss, and easily detachable to plug the solar

panel into an inverter when the power goes out.

We'll update you as we experiment, but Mark is currently on his way to

pick up our components, so this phase of the project is now set in

stone.

Harbor

Freight in Johnson City is an awesome store!

Harbor

Freight in Johnson City is an awesome store!

The manager was in a good

mood and gave us the additional 2 year warranty on each solar power kit

along with the portable power packs.

Stay tuned for more details

as I unbox and set up this new

technology.

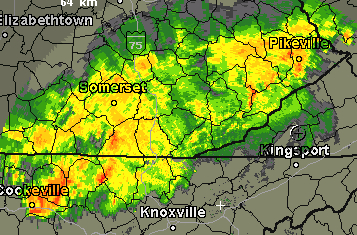

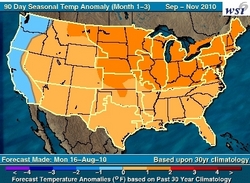

Wednesday

morning, the doppler radar looked like this. We'd had 5 inches of

rain already in the past week, the alligator swamp was filling back up,

and the main creek was once more creating a waterfall off the edge of

the ford. Clearly, our three week dry season had come to an abrupt end.

Wednesday

morning, the doppler radar looked like this. We'd had 5 inches of

rain already in the past week, the alligator swamp was filling back up,

and the main creek was once more creating a waterfall off the edge of

the ford. Clearly, our three week dry season had come to an abrupt end.

At times like this, I

feel like I'm always a step or two behind the weather, scurrying to

catch up. I'd just gotten into the swing of drying

fruit without a dehydrator and would have liked to

continue my success with tomatoes. I also had another  week's

worth of hauling on Mark's agenda. But the weather has mandated

that we shift gears, so we will --- on to weeding and mowing, planting

the last of the fall crops, and maybe finally finishing the shed.

week's

worth of hauling on Mark's agenda. But the weather has mandated

that we shift gears, so we will --- on to weeding and mowing, planting

the last of the fall crops, and maybe finally finishing the shed.

To be fair, drippy

summer afternoons when I'm just barely chilled in a t-shirt and shorts

are probably on my top ten list of favorite times. The rain

encloses me in a cocoon of gray noise and my mind becomes so clear I

can feel deep thoughts gelling in the corners.

I

wrote about the resumption

of rainy weather

yesterday afternoon, after Mark drove Joey's truck out to leave it

across the creek and out of harm's way. It seems like we made the

right call. Rain pounded on the roof all night, bringing our

week's total up over 7 inches. By the time I walked Lucy, the

creek had risen from my ankle to my knee.

I

wrote about the resumption

of rainy weather

yesterday afternoon, after Mark drove Joey's truck out to leave it

across the creek and out of harm's way. It seems like we made the

right call. Rain pounded on the roof all night, bringing our

week's total up over 7 inches. By the time I walked Lucy, the

creek had risen from my ankle to my knee.

I

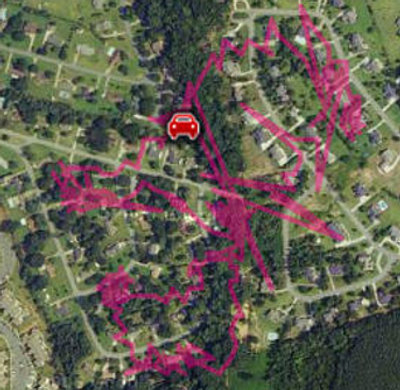

dawdled a bit more than I should have since I knew from the doppler

radar that I only had about twenty minutes between cloudbursts.

But how could I resist trying to capture fog between the hills or a box

turtle catching a huge leech right along the edge of the public

road? My dawdling was worthwhile --- two trucks of tree

trimmers/chippers rolled by and I flagged them down to ask if they

would dump some wood chips in our parking area. They agreed

(although they've agreed before, and no wood chips have shown up), so I

scurried around to move our vehicles out of the way and give them a

place to dump my biomass.

I

dawdled a bit more than I should have since I knew from the doppler

radar that I only had about twenty minutes between cloudbursts.

But how could I resist trying to capture fog between the hills or a box

turtle catching a huge leech right along the edge of the public

road? My dawdling was worthwhile --- two trucks of tree

trimmers/chippers rolled by and I flagged them down to ask if they

would dump some wood chips in our parking area. They agreed

(although they've agreed before, and no wood chips have shown up), so I

scurried around to move our vehicles out of the way and give them a

place to dump my biomass.

Now an hour had passed

and the rain was pouring down. The muddy creek had risen past the

middle of my thigh, and at the rate the rain is still falling, I

suspect we may attain flood conditions today. I love the

neverending excitement on our farm!

I've been looking everywhere

for a replacement wheel for this small wheelbarrow.

A bit of browsing at the Harbor

Freight store yesterday

lead me to this pneumatic wheel with heavy duty bracket for just 10

dollars.

Stay tuned for more pictures

of the installation process.

When

I was a junior in college, I spent my first summer away from home with

no cafeteria. In preparation, I

picked my father's brain for instructions on making my favorite

vegetable soup, pinning him

down on a specific number of onions, potatoes, tomatoes, and

more. But

it was a struggle to turn Daddy's words into a recipe, because that

wasn't the information he was trying to impart. Over a decade

later, I've finally figured out what my wise father was saying.

Yes,

I am a slow learner.

When

I was a junior in college, I spent my first summer away from home with

no cafeteria. In preparation, I

picked my father's brain for instructions on making my favorite

vegetable soup, pinning him

down on a specific number of onions, potatoes, tomatoes, and

more. But

it was a struggle to turn Daddy's words into a recipe, because that

wasn't the information he was trying to impart. Over a decade

later, I've finally figured out what my wise father was saying.

Yes,

I am a slow learner.

Daddy

was teaching me the trick of cooking in season with the easiest

in-season recipe --- harvest catch-all soup. He was trying to get

through my thick noggin the notion that meals should begin in the

garden with what's fresh and numerous, rather than with a detailed

shopping list at the grocery store. Clearly, this soup had been

his mother's way of using up odds and ends --- bits of browned carrots,

wilted greens, anything that wasn't rotten but wasn't prime enough for

being served plain. And, in essence, the soup was simple --- make

a stock, then throw in whatever vegetables you have lying around.

Daddy

was teaching me the trick of cooking in season with the easiest

in-season recipe --- harvest catch-all soup. He was trying to get

through my thick noggin the notion that meals should begin in the

garden with what's fresh and numerous, rather than with a detailed

shopping list at the grocery store. Clearly, this soup had been

his mother's way of using up odds and ends --- bits of browned carrots,

wilted greens, anything that wasn't rotten but wasn't prime enough for

being served plain. And, in essence, the soup was simple --- make

a stock, then throw in whatever vegetables you have lying around.

The

first step was to make a soup base. Daddy's method involves one

onion, some garlic, and a cup and a half of cabbage all sauteed in a

bit of oil,

then simmered for a couple of hours with two stalks of celery, an 18

ounce can of tomatoes, and enough water to fill up the pot. My

method (at the moment, and ever evolving) starts with three quarters of

a pot of halved tomatoes, enough chicken stock to submerge the fruits,

two onions, six big cloves of garlic (minced), a big

handful of parsley (chopped), and about half a cup of dry beans

(pre-soaked.) This is the part of the soup where you'll want to

follow a vague recipe, but you'll notice that parsley is a great

substitute for the much harder to grow celery, and that if you start

with stock you don't need to bother with the sauteeing step. This

is also where you can tweak the flavor to suit your particular tastes.

The

first step was to make a soup base. Daddy's method involves one

onion, some garlic, and a cup and a half of cabbage all sauteed in a

bit of oil,

then simmered for a couple of hours with two stalks of celery, an 18

ounce can of tomatoes, and enough water to fill up the pot. My

method (at the moment, and ever evolving) starts with three quarters of