archives for 07/2010

Even

though I'm the primary cook around here, Mark does nearly all the

grocery shopping. I just hate shopping, so every two weeks, I

hand Mark a list and send him to the big city. He always comes

home with everything on the list...plus this and that. When I

first started converting him to Walden Effect eating, the "this and

that" were things like biscuits-in-a-can and lemon cookies.

Nowadays, I roll my eyes when he brings home...an out of season

butternut.

Even

though I'm the primary cook around here, Mark does nearly all the

grocery shopping. I just hate shopping, so every two weeks, I

hand Mark a list and send him to the big city. He always comes

home with everything on the list...plus this and that. When I

first started converting him to Walden Effect eating, the "this and

that" were things like biscuits-in-a-can and lemon cookies.

Nowadays, I roll my eyes when he brings home...an out of season

butternut.

Yes, we've become such

fans of butternuts (especially butternut pie) that Mark's hard pressed

to live without them over the summer. I didn't know they would be

such a hit, so I only put in two small beds last year, and we ran out

of the delicious fruits in the middle of the winter. This year, I

expanded the planting to encompass three beds, and I fed the soil

well. Cucurbits love a good meal of manure, and before I knew it,

the butternuts had zipped off their own beds, across the aisle, and

were partying with the tomatoes. Bad butternuts!

As every parent knows, proper limits are essential in raising a healthy

child...I mean, butternut. And parents definitely have to work

together to set those boundaries. So Mark and I went out as a

team to train our recalcitrant butternuts to toe the line. Mark

hammered in fence posts and I strung up pea trellis material to cage our butternuts

in. Now they can play as hard as they want and we won't have to

worry about them skipping curfew.

As every parent knows, proper limits are essential in raising a healthy

child...I mean, butternut. And parents definitely have to work

together to set those boundaries. So Mark and I went out as a

team to train our recalcitrant butternuts to toe the line. Mark

hammered in fence posts and I strung up pea trellis material to cage our butternuts

in. Now they can play as hard as they want and we won't have to

worry about them skipping curfew.

I

know that many of you are still stuck on the ethics of eating meat

simply because you can't bear to think that you were personally

responsible for the death of a cuddly cow or cute chicken. If

you're going to go that route, you should definitely become a vegan,

since being a vegetarian doesn't prevent the death of livestock

--- check out my essay about the bloody side of eggs, for example.

I

know that many of you are still stuck on the ethics of eating meat

simply because you can't bear to think that you were personally

responsible for the death of a cuddly cow or cute chicken. If

you're going to go that route, you should definitely become a vegan,

since being a vegetarian doesn't prevent the death of livestock

--- check out my essay about the bloody side of eggs, for example.

But I hope you'll

consider the fact that most of the animals that we

kill are domesticated livestock that wouldn't be able to survive in

the wild if turned loose to fend for themselves. We've entered

into a contract with our cows and pigs, just as we have with our cats

and dogs (although the terms are a bit different.) We feed them,

shelter them, and give them a happy life...until the day the guillotine

falls.

In nature, omnivores (like

humans) eat other animals, and death is part

of life. It just made sense to those first Red

Jungle Fowl

to hang around human villages, staying where the food was copious and

the predators were few. In effect, the chickens-to-be traded a

dangerous life full of wild predators for a safe and easy life with

only one predator --- man.

In nature, omnivores (like

humans) eat other animals, and death is part

of life. It just made sense to those first Red

Jungle Fowl

to hang around human villages, staying where the food was copious and

the predators were few. In effect, the chickens-to-be traded a

dangerous life full of wild predators for a safe and easy life with

only one predator --- man.

On the other hand, pain

and suffering are not part of the contract ---

I believe that CAFOs

void the terms of our domestication agreement. On our homestead,

chickens are raised on pasture, live a happy life, and are killed

quickly, so I consider this a valid way to honor the agreement early

humans and Red Jungle Fowl made when the latter started hanging around

camps of the former.

When I was in high

school, I knee-jerked toward semi-vegetarianism, but

since then I've examined the issue in more detail and concluded that

eating meat in moderation is better for the planet. In many ways,

I think that being a vegetarian is a lot like washing

the birds caught in the oil spill

--- both actions make us feel better about living in a dangerous world

in which things die, but neither action actually helps that world

become a

better place. I'd like to make the world a better place.

| This post is part of our Ethics of Vegetarianism lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I've been curious to know how

long it might take for the baby chick to break away from the mother hen

and sleep on her own roost.

The current sleeping spot is

atop an old stump, which seems a little crowded to me.

My

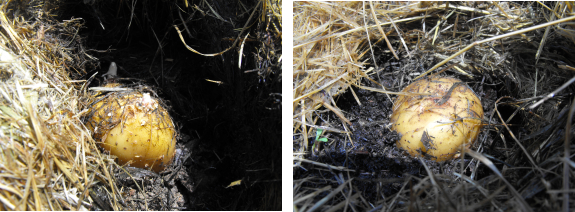

beekeeping mentor told me that he waits until June to plant most of his

potatoes, which means he doesn't have to store the mature tubers during

the heat of the summer. Since potatoes are primarily a storage

crop and have a

limited shelf life, planting them as late as possible makes sense.

My

beekeeping mentor told me that he waits until June to plant most of his

potatoes, which means he doesn't have to store the mature tubers during

the heat of the summer. Since potatoes are primarily a storage

crop and have a

limited shelf life, planting them as late as possible makes sense.

However, when I went

shopping for seed potatoes at the beginning of June, all of the feed

stores looked at me like I was crazy. Instead, I decided to see

whether I could just plant some of my halfway matured spring potatoes

in new beds for a fall crop.

I was so happy with the Ruth

Stout method of potato planting last time around that I

decided to take it a step further this time. I simply spread

manure on a freshly weeded bed, plopped down the seed potatoes, and

covered everything up with a thick layer of grass clippings.

Since then, I've been

waiting, and waiting, and waiting. Nothing has happened.

When I poked around under the mulch, I discovered that very few of the

seed potatoes had sprouted. In fact, all of the small new

potatoes that I had put in the ground whole were sitting there, while

only the few potatoes that were large enough to be cut in half had

begun to grow. I've read that some companies sell new potatoes as

seed potatoes, but I clearly haven't discovered the trick yet.

Since the beds are well

mulched and growing no weeds, I'm going to let them sit for another

month or two even though I now have small hope of a fall potato

harvest. I'll let you know if anything exciting happens, or

whether I end up just digging the seed potatoes to eat.

There

are really only two environmentally and ethically conscious ways to eat

meat --- buy from very small farmers who raise livestock as part of

permaculture systems or raise those animals yourself. We're

still a long way from reaching this optimal state, but I hope you'll

let me show you what I hope our homestead will eventually look like.

There

are really only two environmentally and ethically conscious ways to eat

meat --- buy from very small farmers who raise livestock as part of

permaculture systems or raise those animals yourself. We're

still a long way from reaching this optimal state, but I hope you'll

let me show you what I hope our homestead will eventually look like.

Here in the eastern

United States, forests are the native ecosystem for

most areas, so I envision creating forest pastures to raise both

chickens and pigs while allowing many native plants and animals to

coexist. In the prairie states, long-grass pastures are

probably more appropriate. In either case, it's also essential to

spread livestock out so that manure

becomes a boon rather than a pollutant --- don't raise more pigs than

can be used to fertilize your garden.

We already feed all of

our food waste to the

chickens, but we don't waste much, so the scraps don't make up much of

their diet. We've approached all of the local grocery

stores, hoping that they might give us spoiled produce, but

unfortunately that is against corporate policy. Those of you who

live in urban areas would probably have better luck approaching small

restaurants, and might be able to feed your livestock on food waste

alone.

Hunting is another way of feeding

ourselves high quality meat in a

relatively natural setting. Since deer are overpopulated in our

area, we'll be focusing more on this option as time goes on. Then

there are honeybees --- while they only provide empty calories, it's

hard to complain about a source of food that takes up no more than two

square feet of land and produces roughly 49,000 calories per year.

Unless you make weekly

airplane flights or turn on the air conditioner

with the windows open, changing your eating choices is probably your

best bet for helping the earth. 37% of the earth's

terrestrial area is currently devoted to producing food, and at the

same time habitat destruction is the biggest cause of extinction on

the planet. Isn't it time that we put some deeper thought into

our food choices so that there will be a bit of space left for wildlife

to survive?

| This post is part of our Ethics of Vegetarianism lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

This automatic

chicken coop door design is called the up swing version for obvious

reasons.

You can get the complete kit

from a guy named Jeremy for around 135 dollars which includes an

adjustable timer.

I like the way the movement

goes out, which seems less risky than the guillotine like action of

most automatic chicken coop doors.

Edited to add:

After years of research, Mark eventually settled on this automatic chicken door.

You can see

a summary of the best

chicken door alternatives and why he chose this version here.

If you're planning on

automating your coop, don't forget to pick up one of our chicken waterers. They never spill or

fill with poop, and if done right, can only need filling every few days

or weeks!

Despite

their

uncomfortable roosting arrangement, the mother hen and her

chick are clearly midway through the weaning process. Our

youngest chicken is no longer glued to its mother's side, and instead

opts to spend most of its time foraging with the cockerels.

Despite

their

uncomfortable roosting arrangement, the mother hen and her

chick are clearly midway through the weaning process. Our

youngest chicken is no longer glued to its mother's side, and instead

opts to spend most of its time foraging with the cockerels.

With her first chick ready to fly the coop, Mama Hen has decided to

move on. Tuesday, I noticed her exploring the cockerel's coop,

and Wednesday I found two eggs tucked in an out of the way

corner. I'm tempted to leave the eggs alone and see if our broody

hen

will successfully raise a larger clutch of chicks, but I'm not sure

whether our cockerels are actually mature enough to be fathers.

Some of them are crowing, but the sounds are far from a real

"cock-a-doodle-doo!" What do you think? Is a three month

old rooster old enough to be a father?

This automatic bucket waterer was easy to put together with a DIY kit, a shelf bracket, some scrap

wood, and a handfull of drywall screws.

A future system will make use

of a 50 gallon plastic drum with some sort of gutter collecting

run off water from the roof of the chicken coop.

Has anyone ever tried gleying

a pond? Gleying seems to be an old Russian method that mimics the

way ponds sometimes form in nature. The goal is to produce an

anaerobic layer in the soil underneath the pond, which somehow prevents

water from percolating through (perhaps due to slime on the anaerobic

bacteria.) Here are tips for gleying a pond, compiled from

various websites (none of which feels very definitive):

Has anyone ever tried gleying

a pond? Gleying seems to be an old Russian method that mimics the

way ponds sometimes form in nature. The goal is to produce an

anaerobic layer in the soil underneath the pond, which somehow prevents

water from percolating through (perhaps due to slime on the anaerobic

bacteria.) Here are tips for gleying a pond, compiled from

various websites (none of which feels very definitive):

Create

a six to nine inch layer of fresh compostables. Some sites recommend

using a layer of animal manure covered by a second layer of high carbon

waste material such as paper or cardboard. Other sites note that

grass clippings can be used in place of the manure, and still others

leave out the high carbon layer.

Get

your compostables wet, then seal out the air. Most people recommend

adding a layer of soil on top and tamping it down, but others mention

putting plastic over the pond to keep air out completely. Still

other sources seem to consider the cardboard layer to be the one that

seals air out.

Wait

two to three weeks.

During this time, you shouldn't allow your gley to dry up, but you

can't fill the pond yet. After the wait, your pond is supposed to

be permanently sealed...or sealed for a couple of years (depending on

who you talk to.)

I'm a bit leery of the

technique because I can't find anyone who mentions that they have tried

it personally, although second and third hand reports abound. I'm

also curious to know whether anaerobic pond muck from the alligator

swamp would provide instant gley. If I hauled out a few

bucketsful and used the muck to line a little indentation in our forest

garden, would we have a mini pond? Or is the anaerobic layer

something that forms in place and can get disrupted by digging?

Clearly, gleying a small pond is going to have to be added to my

post-growing season experiments list!

I'm a bit leery of the

technique because I can't find anyone who mentions that they have tried

it personally, although second and third hand reports abound. I'm

also curious to know whether anaerobic pond muck from the alligator

swamp would provide instant gley. If I hauled out a few

bucketsful and used the muck to line a little indentation in our forest

garden, would we have a mini pond? Or is the anaerobic layer

something that forms in place and can get disrupted by digging?

Clearly, gleying a small pond is going to have to be added to my

post-growing season experiments list!

(As a side note, I

couldn't find a single picture on the internet of gleying a pond.

The closest ones were these photos of Sepp Holzer's pig method of

sealing a pond. As usual, click on the image to view the source

website.)

This was my first attempt at

the latest automatic

bucket waterer. I think

it once held cooking oil.

The main problem with a

container like this is the thickness of the plastic. Two of the nipples

screwed in fine, but one of them didn't seem to have enough plastic to

bite into and ended up leaking.

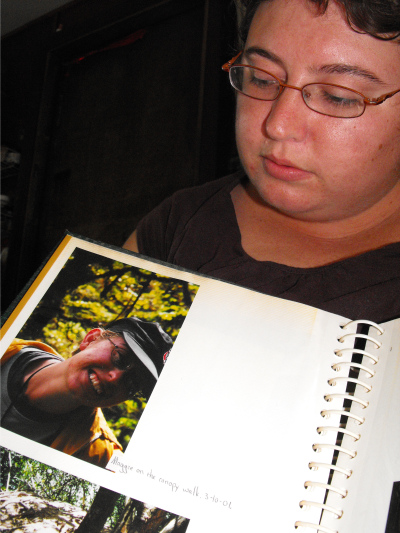

This

weekend, I tricked Mark and his mom into taking me to Sunwatch Indian

Village in Dayton. My companions win the patience award for not

even looking bored while I took notes for three hours on how Native

Americans fed themselves 800 years ago. Okay, maybe they do look

a little bored....

This

weekend, I tricked Mark and his mom into taking me to Sunwatch Indian

Village in Dayton. My companions win the patience award for not

even looking bored while I took notes for three hours on how Native

Americans fed themselves 800 years ago. Okay, maybe they do look

a little bored....

I was intrigued by this

particular window into the past because corn had just become the

mainstay of the Native American diet, making up over half of the

villagers' diets. Meat (76% of which was venison) made up another

40% of their diets, so I wasn't surprised that the Sunwatch villagers

were actually less healthy than their recent ancestors, with over half

of their children dying before the age of six. We all know that a

diet of corn and meat with very few fruits and vegetables isn't going

to promote good health.

The villagers stored

their corn for the winter in large, grass-lined storage pits.

Each family of six to eight people had their own pit, which would hold

500 or more pounds of corn. I loved the museum's reconstruction

of a typical storage pit while in use:

...and then, once

emptied of corn, how it might have looked when filled with the family's

garbage...

...and, finally, what

the pit looked like when archaeologists carefully picked through it 800

years later:

The

reconstructed village also included a typical three

sisters garden,

which I've pictured here. Unfortunately, there was much less

interpretation about the garden than about the buildings, so I came

away with more questions than answers. Most importantly, I ended

up curious about how the Native Americans combatted the squash vine

borers, which my

trained eye noticed were already hard at work wiping out the pumpkins

in Sunwatch's garden. Does anyone know?

The

reconstructed village also included a typical three

sisters garden,

which I've pictured here. Unfortunately, there was much less

interpretation about the garden than about the buildings, so I came

away with more questions than answers. Most importantly, I ended

up curious about how the Native Americans combatted the squash vine

borers, which my

trained eye noticed were already hard at work wiping out the pumpkins

in Sunwatch's garden. Does anyone know?

I

posted some images of the lodges in my review

of Sunwatch Village

over on our Clinch Trails website (which I've decided

to reenvision as our travel website), but what caught my eye in the

architectural arena was the way the Native Americans burned the bases

of their posts to protect the wood from insects and rot. I would

have thought that charring the base of a post would make it less

structurally sound, but presumably they knew what they were doing.

I

posted some images of the lodges in my review

of Sunwatch Village

over on our Clinch Trails website (which I've decided

to reenvision as our travel website), but what caught my eye in the

architectural arena was the way the Native Americans burned the bases

of their posts to protect the wood from insects and rot. I would

have thought that charring the base of a post would make it less

structurally sound, but presumably they knew what they were doing.

On the other hand, the

buildings weren't meant to last forever. Like my method of intentionally

underbuilding, the

Sunwatch villagers were used to moving on after a couple of decades

when firewood and game in the immediate vicinity had been

exhausted. As with slash

and burn agriculture,

the sustainability of using up all of an area's resources and then

travelling to a new region is questionable, but the method might make

sense if populations are low enough that the land is given a century to

recover after each episode.

Finally, doesn't this

watch platform look perfect? I've long wanted to have one of

these in the middle of the garden with a ramp up to the platform so

Lucy could nap there and watch over our entire domain. Who knows

--- the Sunwatch villagers might have even let their dogs stand watch

there too!

Our Black and

Decker 18 volt drill has been replaced with a DeWalt.

Our Black and

Decker 18 volt drill has been replaced with a DeWalt.

You can feel the increased

power and torque the first time you use this beauty.

Well worth the extra cost if

you find yourself delving into more advanced projects.

I'm

searching for a cover crop that:

I'm

searching for a cover crop that:

- is reliably winter-killed in zone 6 (meaning that I don't have to till it in or pull it out)

- is non-leguminous (so that I'll get lots of organic matter rather than lots of nitrogen)

- will survive in our problem spots --- dense, clayey soil with a

high water table

So far, buckwheat and oats seem to be my top

contenders. I've been slipping buckwheat into gaps in my rotation

this month, beds where spring crops have been pulled out with nothing

to take their place for at least six weeks. Next month, I'll

plant oats in empty beds.

If all goes as planned,

our cover crops will turn into a heavy mulch that will partially or

entirely decompose in time for spring planting. It's even

possible that the buckwheat will die in five or six weeks when I mow it

down at bloom time, allowing me to plant garlic under the green manure

a few weeks later.

Do you have a favorite

no-till cover crop? I'm open to any and all suggestions since

this year is our first trial.

I take back my previous 5

gallon bucket stacking suggestion after todays discovery.

The handle is obviously made

to tuck into another bucket to prevent stickage.

I need to take more time and

listen to my tools more often...I wonder what other obvious secrets

will be imparted my way if I can just listen a little harder?

I

seem to have slightly over-planted our Egyptian onions this

year. I only put in three small beds...and then three more

patches sprang up from compost piles where I'd tossed the excess

bulbs. The result was so many

onions that I didn't even put a dent in the population by pulling whole

plants to eat over the winter, and now that it's time to harvest the

top bulbs,

I'm officially overwhelmed. This basket is less than a third of

the harvest!

I

seem to have slightly over-planted our Egyptian onions this

year. I only put in three small beds...and then three more

patches sprang up from compost piles where I'd tossed the excess

bulbs. The result was so many

onions that I didn't even put a dent in the population by pulling whole

plants to eat over the winter, and now that it's time to harvest the

top bulbs,

I'm officially overwhelmed. This basket is less than a third of

the harvest!

Rather than composting

the top bulbs (a method that clearly failed last year),

I'm going to sell them in big bunches to anyone willing to start a

good-sized Egytian onion patch. I don't really want to get into

the retail side of mailing off a few bulbs here and there, but if

you're a regular commenter and just want a tiny start, email

me and

I'll likely oblige you. You definitely want these plants in your

garden if you grow in

zones 3 through 9. Sorry, I can't mail them outside the U.S.

To order, click on the

paypal button above to buy 100 top

bulbs for $25 (with free shipping.) 100 bulbs will weigh

approximately 5 ounces and will be enough to start one good-sized bed

that will feed one or two average people. Your package will

contain small, medium, and large bulbs.

If you really want to

feed an army (and help me get rid of these top

bulbs as quickly as possible), you can buy 500 top bulbs for $75 (with

free shipping.) If so, click this button instead.

Once

you receive your bulbs, plant the Egyptian onions as soon as

possible in good garden soil in full sun. The very top of the

bulb should be poking out of the ground, but the rest should be

submerged. Some people recommend planting them a foot apart, but

I've found that my plants do well in raised beds spaced only about

three inches between centers. Leave the plants alone for a few

months, then you should be able to start

harvesting green onions in the middle of the fall through the winter.

Once

you receive your bulbs, plant the Egyptian onions as soon as

possible in good garden soil in full sun. The very top of the

bulb should be poking out of the ground, but the rest should be

submerged. Some people recommend planting them a foot apart, but

I've found that my plants do well in raised beds spaced only about

three inches between centers. Leave the plants alone for a few

months, then you should be able to start

harvesting green onions in the middle of the fall through the winter.

To maintain a perennial

patch, cut only every second or third leaf,

making sure that the plant has enough green leaves to continue

growing. You can also dig up entire bulbs in the winter to use in

recipes that call for leeks, but you'll want to let all your plants

grow

the first year. By this time next year, your plants should be

putting up top bulbs, each of which can be planted to expand your

patch. As long as you don't get too greedy and overharvest,

Egyptian onions will soon become your most dependable --- and easiest

--- vegetable.

The K9

electric pet barrier

continues to keep Lucy from even coming close to the chicken

pasture area.

It seems to have taken only

one zap to get the point across.

I'm thinking of unplugging it

to see if the threat alone is enough to keep her away.

Last

week, I noticed that the bottom leaves of our tomato plants were curled

up. The leaves weren't yellowing, browning, or developing spots;

they were just bent in an odd curve that made the pale undersides

visible.

Last

week, I noticed that the bottom leaves of our tomato plants were curled

up. The leaves weren't yellowing, browning, or developing spots;

they were just bent in an odd curve that made the pale undersides

visible.

Even though I usually

try to be very proactive and look up problems as soon as I see

symptoms, this time I procrastinated. I've been living in fear of

the blight all growing season, and,

honestly, if my tomatoes were blighted, I didn't really want to know.

It turns out that I

could have set my mind at rest days ago. There is a leaf curl

disease caused by the Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus, but the virus'

symptoms include yellowing leaf margins and crumpled leaves, neither of

which my plants show. Instead, chances are my curled leaves are

the result of letting the plants get a bit drought-stressed, then

saturating the soil a bit too much, all combined with my new, drastic

pruning regime.

The leaves may stay curled, but it sounds like I won't see any damage

to the plants' growth or fruiting.

I'm very relieved that

my tomatoes aren't going to die, but I would still like them to hurry

up and feed me! The plants are dripping with huge green fruits,

but none has even shown a tinge of color. As I read on more and

more blogs about homegrown tomatoes, my patience is wearing thin.

Fresh sliced tomatoes, vegetable soups, sweet pizza sauce --- I'm

aching to taste them again....

I've always thought the

traditional pop up style campers had room for improvement.

The Yurtle will put an end to

your square lodge blues with a nice circular structure to rest within.

This portable model will run you about 6800 bucks, which seems

comparable to other new pop up campers. The Yurtle will take at least

an hour to set up compared to seconds on the pop up.

Seems like this might be a

great alternative to the FEMA trailers we heard so much about after

hurricane Katrina?

Go

to Laurelnestyurts.com for more round options and

details on their small community of 14 yurts. They've got a few

sections to their blog where they discuss permaculture and gardening,

topics that drove me to their site in the first place.

Go

to Laurelnestyurts.com for more round options and

details on their small community of 14 yurts. They've got a few

sections to their blog where they discuss permaculture and gardening,

topics that drove me to their site in the first place.

We

went a little overboard with experimental beans this year, and now

we're starting to get an idea of which ones like our garden.

First of all, I should note that our old standby Masai Beans are still

plugging right along. We already have a

gallon of delicious green beans in the freezer, with many more to

come as my later-planted beds start to bear. Masai Beans

are really the best green beans I've ever tasted, and they're

stringless, so preparation is a breeze. Plus, you can save the

seeds --- we haven't bought green bean seeds in three years.

We

went a little overboard with experimental beans this year, and now

we're starting to get an idea of which ones like our garden.

First of all, I should note that our old standby Masai Beans are still

plugging right along. We already have a

gallon of delicious green beans in the freezer, with many more to

come as my later-planted beds start to bear. Masai Beans

are really the best green beans I've ever tasted, and they're

stringless, so preparation is a breeze. Plus, you can save the

seeds --- we haven't bought green bean seeds in three years.

On the experimental

side, a friend of mine mailed me a few of her favorite dried

beans to play with --- Yellow Indian (pictured above), Allubia Criolla,

and Cayamento

Cranberry. My goal here is to find a dried bean that will capture

even Mark's interest, and I'm willing to try as many varieties as it

takes to reach that point. Currently, the pole beans are happily

running up their trellis, blooming like crazy, and setting big

pods. I won't really have information for you, though, until we

run a taste test.

Our

garbanzo beans are less happy. I planted Black Karbouli Bush

Garbanzo at the end of April, but later learned that garbanzos like

cool weather and should be planted at the same time as the peas.

No wonder a

third of my plants dried up and the rest have luxuriant foliage but no

signs of blooms. Even if we get nothing out of this experimental

bed, I'll try the garbanzos again next spring, planting in a more

proper time frame to see what develops.

Our

garbanzo beans are less happy. I planted Black Karbouli Bush

Garbanzo at the end of April, but later learned that garbanzos like

cool weather and should be planted at the same time as the peas.

No wonder a

third of my plants dried up and the rest have luxuriant foliage but no

signs of blooms. Even if we get nothing out of this experimental

bed, I'll try the garbanzos again next spring, planting in a more

proper time frame to see what develops.

We

also planted Urd Beans (for sprouting) and some Endamame Soybeans

(for endamame). The two types of beans seemed

happy as little clams...until the deer came in and ate them. We

had a few minor deer incursions this summer when deterrents went

down, and our four-legged f(r)iends seem

quite partial to my experimental crops. So, just like with our

garbanzos, if we fail to get a crop this year, I won't despair.

We

also planted Urd Beans (for sprouting) and some Endamame Soybeans

(for endamame). The two types of beans seemed

happy as little clams...until the deer came in and ate them. We

had a few minor deer incursions this summer when deterrents went

down, and our four-legged f(r)iends seem

quite partial to my experimental crops. So, just like with our

garbanzos, if we fail to get a crop this year, I won't despair.

Now that we've done

everything wrong that we possibly can with beans, I'm hoping next year

will be a stunning success. For the sake of comparison, oilseed

sunflowers were one

of our big experiments last year, so the deer ate them down to the

ground. This year, the sunflowers were no longer experimental, so

the deer left them alone and the plants are now towering over my

head. Clearly, there is a moral here, if I can only figure it

out. Maybe the deer are bored by my experiments posts?

"Come

right on over," I said. "But be prepared --- I may not want to

see you in the morning."

"Come

right on over," I said. "But be prepared --- I may not want to

see you in the morning."

No, I wasn't setting up

a one night stand. I was inviting my sister to the farm to leaf

through our journals, photo albums, and sketchbooks from our Costa

Rican adventure a decade ago. (And being realistic about my

introvert tendencies that consider house guests and fish bad after

about five hours.)

I don't want to be too

specific, because it's summer and a bad, bad, bad time to take on new

writing projects. But I'm currently fired up to summarize

the highlights of our past journey on my Clinch Trails blog. I'll let you

know if it turns out to be anything more than a pipe dream, but for now,

Maggie and I are enjoying the music.

Although

I should have been taking advantage of the cool, rainy weather to get

the garden weeded, I

played hookie on Friday. I've discovered that

when I get an idea for a written or visual project, I should drop

everything and explore while I'm enthusiastic, letting those creative

juices flow while they're in motion. This freedom to create is

the best part of homesteading.

Although

I should have been taking advantage of the cool, rainy weather to get

the garden weeded, I

played hookie on Friday. I've discovered that

when I get an idea for a written or visual project, I should drop

everything and explore while I'm enthusiastic, letting those creative

juices flow while they're in motion. This freedom to create is

the best part of homesteading.

The truth is that I'd

been wanting to work up some sketchbooks from my year abroad into a

story for common consumption, but my memory is so fuzzy that I couldn't

visualize life a decade ago well enough to write about it.

Maggie's memory is considerably better, and she wrote interesting

tidbits in her journal that complement my copious scientific notes very

well. We churned out a

joint post last night about our first day in Costa Rica, and I'm excited to keep

collaborating on the project.

As usual when I get

obsessed with a non-homesteading topic, I'll stop posting about it over

here after this entry. So, if you're interested in reading about

my decade-old journey (and the natural history of Costa Rica), be sure

to subscribe to the RSS feed over on Clinch Trails. Maybe this will make

up for the continued summer vacation of the lunchtime series.

"That

fence is just there to keep the dogs out, right?" said one cockerel to

the other as they roosted on their coop roof and peered out into the

unknown wilds.

"That

fence is just there to keep the dogs out, right?" said one cockerel to

the other as they roosted on their coop roof and peered out into the

unknown wilds.

"I think I'll stay

inside anyway," replied his brother, drowsily.

(I consider this

evidence in support of the domestication

contract.)

Fulfill your side of the contract by providing your poultry with copious clean water using our homemade chicken waterer.

As

you can see in this photo of my mom, we've had our Walden Effect

t-shirts for two solid weeks. I've been holding out on you

because I can't seem to figure out whether we'll be able to send the

t-shirts for a couple of dollars as first class mail or if we have to

pay $5 for priority mail. I finally decided to just let the first

few customers buy them at the cheap price ($10), and if it costs more

to mail the shirts, we'll raise the price later. So buy them

while they're hot!

As

you can see in this photo of my mom, we've had our Walden Effect

t-shirts for two solid weeks. I've been holding out on you

because I can't seem to figure out whether we'll be able to send the

t-shirts for a couple of dollars as first class mail or if we have to

pay $5 for priority mail. I finally decided to just let the first

few customers buy them at the cheap price ($10), and if it costs more

to mail the shirts, we'll raise the price later. So buy them

while they're hot!

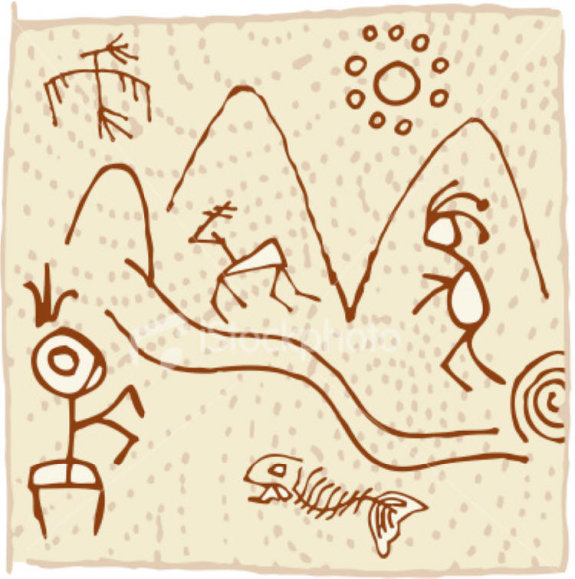

Here are some quick

stats so you'll see whether our t-shirt is right up your alley:

- Color is "serene green" --- as pictured. I chose the color

because it's light enough to work in outside in the sun, but earthy

enough that those pesky weeding stains will be less visible.

- T-shirt is "2000 Gildan Ultra Cotton", which is 100% cotton, unisex, 6.1 oz.

- Printing is on the front in black and gray. The image is

based on a petroglyph, tweaked to suit our permaculture farm. You

can see a more head-on image of the design here.

- Sizes are M, L, XL, and XXL. Be sure to note your size with your order! I decided to merge the slight additional cost for the XXL into the overall price, so all of the t-shirts cost $10 apiece (with free shipping in the U.S.) But I ordered fewer XXL and XL than perhaps I should have --- if that's your size, you might want to buy now. (If you're medium or large, you can probably wait a while.)

I hope you'll enjoy our

t-shirts and then email me an image of your Walden

Effect style in your own garden. I'd love to post a collage of

all of our loyal readers on their home turf. (If you hate the

design, though, don't feel in any way obligated to buy one.)

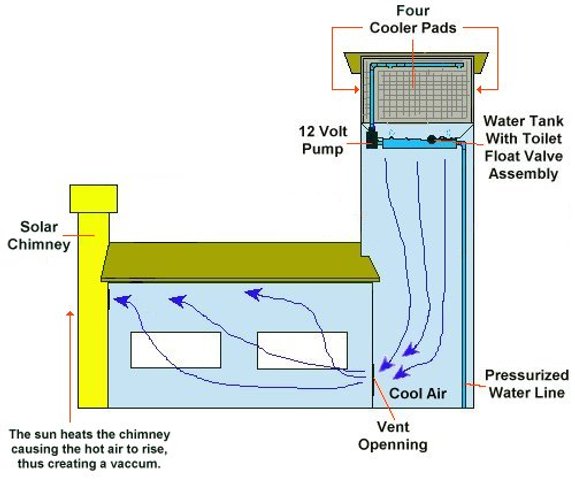

In searching for more low

budget do it yourself cooling options I came upon this cooling

tower design.

It seems like one of the more

expensive solutions out there, but might end up saving money in the

long run. The tower should be at least 6 feet square, 20 to 30 feet

tall with as much insulation as you can muster.

I wonder if this concept

could be scaled down for just one room instead of an entire house?

Image credit goes to the thefarm.org which has a well written article

on this method of sustainable cooling. They've also got a good section

on

permaculture in Tennessee.

When

I was a kid, we never cultivated brambles (blackberries and

raspberries.) Instead, we knew spots where big patches grew wild,

and we'd go on a pilgrimage to pick by the side of a country

road. With such good wild berry patches, why grow your own?

When

I was a kid, we never cultivated brambles (blackberries and

raspberries.) Instead, we knew spots where big patches grew wild,

and we'd go on a pilgrimage to pick by the side of a country

road. With such good wild berry patches, why grow your own?

Lately, I've decided

that cultivated brambles do have definite

advantages. The large cultivated berries are quick and easy to

pick, and in many cases taste as good or better than the wild

berries. You can grow thornless varieties (particularly of

blackberries) to cut down on the scratch factor and everbearing

varieties (particularly of red raspberries) that extend the bramble

season from early summer through the killing frost. If you find

varieties well suited to your soil and climate, you can also expect

much higher production out of cultivated brambles than out of wild

canes.

Although cultivated blackberries

and raspberries can be pricey, the frugal homesteader quickly learns

that she only needs to buy one plant of each variety. If the

brambles like your garden, they'll grow so fast that you'll be overrun

with offshoots to give away by the end of the second year. (But

do be prepared to

run through a few varieties before you find one well

suited to your garden.)

Although cultivated blackberries

and raspberries can be pricey, the frugal homesteader quickly learns

that she only needs to buy one plant of each variety. If the

brambles like your garden, they'll grow so fast that you'll be overrun

with offshoots to give away by the end of the second year. (But

do be prepared to

run through a few varieties before you find one well

suited to your garden.)

The only real

disadvantage I've found with cultivated brambles is that they take up a

good deal of space. On the other hand, they tend to grow well in

awful soil that wouldn't support anything else, and if you prune them

ruthlessly (and mow up any shoots that wander out of their row), you

can definitely keep brambles under control. Our patch of

blackberries and raspberries is the easiest and most productive part of

our fruit garden so far.

This is the petroglyph we

based our Walden

Effect T-shirt on.

Petroglyphs are rock carvings found all

around the world dating back as far as 12 thousand years.

This one seemed to be trying to

transmit some sort of message which I'm still trying to decipher.

This year, I

decided I was going to wean us off Bt even if it meant a

squashless season. Maybe it's a fluke, but we've actually had a

much better cucurbit year than ever before. My new secret is

succession planting.

Notice how the cucumber

vine on the left is starting to wither up? This time last year I

would have been pulling out my hair, but now I simply shrug my

shoulders and look at the bed of three week old cucumber plants nearly

ready to bloom. I plan to seed a third bed of cucumbers this week

so that we'll have a final glut of cucumbers around the end of August.

I did even better with

the summer squash. Our four spring plants gave us nearly two

gallons of fruits to go in the freezer (with who knows how many eaten

and uncounted), but now the squash have collapsed into a mass of vine

borers, squash bugs, and disease. No worries --- check out our

month-old youngsters who just gave us their first fruits. Again,

I've got more squash on my succession-planting list for this week to

take over when our second planting bites the dust.

To be fair, succession

planting isn't my only innovation this year. I'm growing a different variety

of cucumber (Diamant)

and of summer squash (Butterstick Hybrid.) I also gave our

cucurbits quite a bit of extra compost so that they'd grow quickly and

give us produce before disease and pests struck. And the weather

has been perfect --- droughty weather with us irrigating

regularly. Still, I think succession planting has been key in

this year's success, and I suggest giving it a try before spraying Bt.

I got this scar today by not obeying the first rule of the Hitch

Hikers Guide to chickens which is to always have a clean towel

handy.

This round of chicken

catching was twice as difficult due to their increased size and speed.

One of the more aggresive

roosters jumped up and karate chopped me during my first attempt.

Once I took a moment to catch my breath it became obvious where I went

wrong. No towel.

A good sized towel can act as

a shield/net when you're going up against a coop full of roosters.

Once I developed my towel

technique it started to feel similar to what you see during a bull

fight, minus the sword and dangerous horns, but those chicken claws are

nothing to sneeze at.

In

my opinion, chicken butchering is not something you want to learn out

of a book. We acquired the skill by helping out at a

couple of different chicken-processing days on friends' farms, picking

up lots of hands on information that we never would have found in

print. So when we read on Everett's blog that he'd had a hard time

with poultry processing on his new farm, we invited him to our next

kill day.

In

my opinion, chicken butchering is not something you want to learn out

of a book. We acquired the skill by helping out at a

couple of different chicken-processing days on friends' farms, picking

up lots of hands on information that we never would have found in

print. So when we read on Everett's blog that he'd had a hard time

with poultry processing on his new farm, we invited him to our next

kill day.

We thoroughly enjoyed

meeting one of our long-time readers in person, and hope that Everett

got something out the experience too. He certainly sped the

processing along, not only with his hands but with his fascinating

tales of his business endeavors (beginning with selling gum in grade

school, progressing through writing about surfing in Australia, and

culminating with his current SEO skills.)

We feel very lucky that

Everett ended up settling only two hours away, and we're looking

forward to meeting his wife. Maybe next time, Missy will come

along to paint our fence...um...er...kill our chickens.

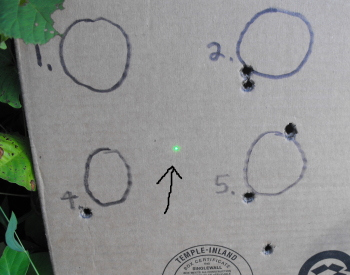

When Anna and I target practice with the Highpoint

rifle we usually take turns shooting 4 shots each and then check

the results.

There's room for improvement,

but we're getting better.

I've had my eye on our

oldest tomato plant for weeks. (This is

the one that volunteered in our lemon tree's pot this winter and which

I set out in the garden on April 21, babying

through cold spells.)

The plant swelled up huge fruits, then

kept swelling more and more fruits, none of which changed color.

Last week, I saw the tiniest hint of red on the oldest fruit, and

crossed my fingers. But I was looking in entirely the wrong spot

for our first tomato.

Wednesday

morning, I caught a glimpse of

orange from the tomato bed on the opposite side of the naughty

butternuts. I

peered closer and saw a fruit nearly ripe!

Wednesday

morning, I caught a glimpse of

orange from the tomato bed on the opposite side of the naughty

butternuts. I

peered closer and saw a fruit nearly ripe!

A few years ago when we

splurged on seeds for several heirloom

tomatoes, I picked out Stupice as a very cold-tolerant and early

variety. Sure enough, it looks like the Stupice tomato will

probably be the first one on our plate, perhaps by the end of the week.

To be fair, though, this

mini-experiment doesn't prove that tomatoes started in a cold frame and

set out at the frost free date ripen just as quickly as those started

indoors and transplanted out three weeks earlier. I have

absolutely no clue what variety my volunteer belongs to, and I suspect

it might have been the seed of a storebought tomato that made it into

our neighbor's compost and thus to us. At this point, though, I'm

at the who-cares stage --- as long as I get a sun-ripened tomato

shortly, experiments will fly out of my head.

One way to improve shooting

accuracy is with a

targeting laser.

This one can be switched from

red to green depending on lighting conditions.

Stay tuned for a full report

once we get it installed and run it around the block.

Although I'm a vegetable

conneisseur, I don't have enough experience to tell the difference

between mediocre meat and awesome meat. This is where Huckleberry

comes in handy.

When I take a piece of

meat out of the supermarket wrapper, Huckleberry naps on the

couch. I can even open a can of tuna, and our spoiled cat will

barely twitch his nose. But when I bring in freshly slaughtered

chickens, he comes running to the kitchen where he meows (in vain) for

a treat.

After its two

day grace period, I

roasted up one of Tuesday's chickens yesterday and Huckleberry was

suddenly ready to help out with anything, no, really, anything. Meow! (Yes, this time I did

give him a tidbit of meat to nibble on.)

To my untrained taste

buds, the 16 week old Dark Cornish roosters are less flavorful

than the 12 week old roosters, falling on the taste gradient somewhere

between a storebought, organic, uncooked chicken and a storebought

rotisserie chicken. But to Huckleberry's nose (and mouth), our

homegrown chickens are ten times better than either. I suspect

Huckleberry is sniffing out the superior nutrition, which makes me even

more inclined to keep experimenting with a good way to raise our own

meat.

The golf cart stopped going last week and I

finally got a chance to start the troubleshooting process.

We've been running it pretty

hard lately on some rough ground, and my first thought was to take the

batteries out so I could flip it on its side to see if anything had

gotten damaged.

Everything looked fine, and

the batteries measure a full charge. It could be the solenoid, or a

problem with one of the switches. The next step will be to seek some

professional advice from the guy we took it to last year.

I like to pretend that

our garden looks like the image above --- well-weeded beds separated by

carefully mown aisles. But at this time

of year, a lot of it actually looks like this picture:

Yes, our garden is full

of weeds. We're slowly developing a mulching technique, but this year is

a bit of an experimental year, so we haven't mulched nearly as much as

I would have liked. Instead, I weed the garden constantly,

rotating through so that each area is weeded at least once a month.

Or at least that's the

plan, which I manage to achieve in the spring. By the height of

summer, though, my rotation extends out to nearly two months, which is

how long it's been since the portion of the garden in the second photo

was weeded. Luckily, our vegetables have grown tall in that span

of time, so they don't seem to have been stunted by their weedy

neighbors.

I've been reading Corn

Among the Indians of the Upper Missouri (which may become a

lunchtime series if I ever get my act together), and at first I was

stunned by the traditional cultivation method the Native Americans

employed --- plant and weed like mad until the entire garden has been

weeded twice. Then go off to hunt buffalo for the rest of the

summer, returning just in time to harvest your corn, beans, squash, and

sunflowers. But the truth is that if you weed carefully when your

vegetables are in the seedling stage, most veggies can quickly outstrip

the weeds and form a leaf canopy that excludes competitors. Sure,

we might get a slightly higher yield if I weeded more obsessively, but

there are only so many hours in the day.

The primary point of

this post is --- don't feel bad if your garden is weedy! We've

passed the point of no return (July 4), so the worst that weeds can do

to your garden now is seed a new crop of weeds for next year. If

you do your best to pull the weeds out before they fruit, I think it's

quite all right to focus on the harvest.

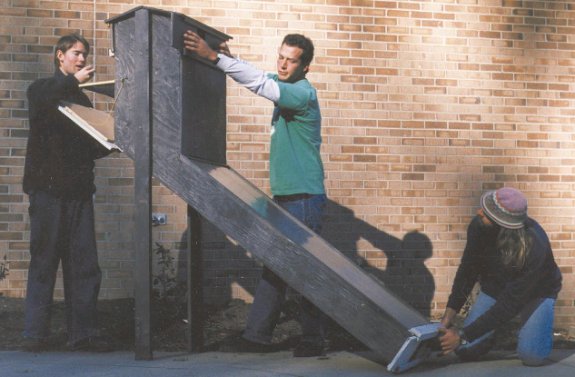

This seems to be the best

do it yourself solar dryer design out there.

You can thank the good folks

of Appalachian State University for the design and testing.

We plan on building one in

anticipation of our upcoming tomato harvest.

ASU has put this thing through many testing situations with documented

data available as a PDF download.

This

spring, I decided that broccoli

is our most productive cool season crop per unit space, so I decreased our planned

pea plantings and increased our broccoli plantings for the fall.

The broccoli came up quite well, although I did have to transplant a

few seedlings that were too close together, filling in gaps where dry

soil had prevented any broccoli from germinating.

This

spring, I decided that broccoli

is our most productive cool season crop per unit space, so I decreased our planned

pea plantings and increased our broccoli plantings for the fall.

The broccoli came up quite well, although I did have to transplant a

few seedlings that were too close together, filling in gaps where dry

soil had prevented any broccoli from germinating.

Since we gorged on

broccoli this spring and still managed to put away two gallons of

the florets, it feels a bit decadent to have planted half again as many

broccoli beds for the fall. However, the later in the year we can

eat fresh produce, the healthier and happier we'll be. I also

like to keep the garden full and productive, and I know that my usual

recipients of excess garden produce all love broccoli.

As a side note --- the

freezer is nearly half full, and we're also halfway to our winter

goal. We've put away 9 gallons of vegetables as well as a good

deal of pesto and homegrown chicken. I can tell we won't be

reduced to buying produce from the grocery store in March of 2011.

I first discovered

permaculture pioneer Sepp Holzer when I posted about do it

yourself aquaponics back

in the spring.

The guy from Richsoil.com got

a chance to spend 12 days with Sepp and he did a great job of

documenting his visit with pictures, videos, and detailed

descriptions of the Sepp Holzer style of permaculture.

Richsoil.com also has an in

depth section on his experiences and

observations with raising chickens that I found informative and

useful.

Mark and I are in the

research stages of putting together a very small solar backup for use

during power

outages, and I'm

hoping that some of the more technical folks among you can give us the

benefit of your wisdom. During three power outages over the last

few months, we've figured out that running the generator for an hour a day keeps the

farm ticking along, but that we miss two major creature comforts ---

lights on winter evenings and more steady access to the internet.

Mark and I are in the

research stages of putting together a very small solar backup for use

during power

outages, and I'm

hoping that some of the more technical folks among you can give us the

benefit of your wisdom. During three power outages over the last

few months, we've figured out that running the generator for an hour a day keeps the

farm ticking along, but that we miss two major creature comforts ---

lights on winter evenings and more steady access to the internet.

Luckily, these gadgets

don't draw much juice --- about 25 watts apiece for our laptops,

another 23 watts for the router, and 13 watts for a CFL. We

figure that if we increase efficiency by buying a car charger for the

laptops (deleting the inefficiencies from converting DC to AC to DC)

and buy a couple of DC LED lights, we could coast along on very little

electricity, allowing us to work and play online for perhaps 3 hours

per day on a solar system costing less than $300.

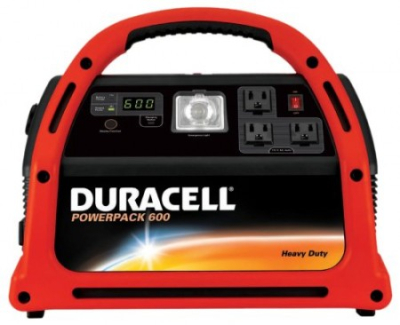

A

simple solar system that doesn't seem to require much technical

know-how consists of a 600 watt Duracell Power Pack (basically, a 12

volt, 28 amp-hour, AGM battery; a controller; and a 600 watt inverter

combined into one unit, costing roughly $125) along with a 25 to 30

watt solar panel (roughly $150.) Many solar panels come with the

right connectors, so the system would be basically plug and play.

A

simple solar system that doesn't seem to require much technical

know-how consists of a 600 watt Duracell Power Pack (basically, a 12

volt, 28 amp-hour, AGM battery; a controller; and a 600 watt inverter

combined into one unit, costing roughly $125) along with a 25 to 30

watt solar panel (roughly $150.) Many solar panels come with the

right connectors, so the system would be basically plug and play.

The flaw I see in the

combo above is that the solar panel might not fully charge the battery

in a single day of sun --- some websites say the system will charge up

in 5 to 7 hours, but other sites think the system will take 16 to 18

hours to charge. We can't just add a larger solar panel for

quicker charging since the manufacturer notes that you can't hook a

panel larger than 30 watts directly to the power pack without adding an

external charge controller.

So here are my questions:

- Is it okay to shop around and find the cheapest 30 watt solar

panel, or are cheaper solar panels going to burn out quickly? Are

there solar panel categories I should be aware of in the low end,

consumer market?

- We're willing to pay a bit extra for plug and play (and

portability), but don't want to be seriously ripped off. Would it

be smarter to do more research and buy the battery, inverter, and

charge controller separately?

- If we bought an external charge controller and a 50 watt solar panel, would the larger panel charge our power pack faster? My very vague understanding makes me think it wouldn't, that the charge controller would just filter out the extra power from the larger solar panel since it's more than the battery can handle.

- One website notes that this system would give us around 160 watt-hours per day. I'm not actually sure where people came up with that figure --- does it make sense? Does that mean that I could run a single 25 watt laptop for 6 hours?

Basically, these

questions all come down to one major one --- is this a bad idea?

We like the modular nature of the system, especially since Mark thinks

we could use the power pack with pedal power, a bit like this article describes. But we

don't want to spend a few hundred bucks on a dud.

With

tomato season officially underway, we're

going to have to make some hard

decisions. Like --- now that our happy plants reach over my head,

do I keep tying them up and harvest with a

stepladder or do I let the plants hang

down?

With

tomato season officially underway, we're

going to have to make some hard

decisions. Like --- now that our happy plants reach over my head,

do I keep tying them up and harvest with a

stepladder or do I let the plants hang

down?

Or, how about this ---

do we plan ahead for a future blight year and can some tomatoes

as well as freezing them?

And --- what do I do

with that first roma when it doesn't have enough sisters to make into

sauce?

This week's lunchtime

series doesn't actually answer any of those

questions, but it does explore some of the cosmetic problems you might

run into while wandering through your tomato patch. I mentioned

in an earlier comment that orange

tomatoes are caused by high heat, and the truth is that

tomatoes will complain about lots of environmental variations in

several different ways.

I subscribe to the "eat

it or give it to the chickens" school of

thought, so discussing vegetable cosmetics is out of the

ordinary. But I recently realized that beginning gardeners might

not know the difference between pissy tomato plants upset by two days

without adequate water and blighted tomatoes that are going to wipe out

your entire tomato garden. If that describes you, stay tuned for

a look at all of the tomato problems that aren't contagious and can simply be

cut out of the ripe fruit.

| This post is part of our Minor Tomato Ailments lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The new chick

continues to grow and is no longer attached to the mother hen.

I guess this growing up thing

happened a week or so ago.

He's an outsider to the flock

and flies by his own rules.

Thanks

to everyone's great advice, I'm starting to narrow down our choices for

our power

outage solar backup system. First of all, Joey

and Roland (and the web) helped me figure out what size system I should

be looking for. I added up two hours run time on our laptops,

router, and two lights and came up with 150 watt-hours per day.

Using Joey's math, or just dividing by the 3 peak sun hours our area is

rated to receive in the dead of winter (from the map above), we would

need a 50 watt solar panel to achieve our goal. Since it's bad

business to discharge your batteries more than halfway, we would need

to buy two Duracell Power Packs and two 25 watt panels to reach this

level --- total cost roughly $450.

Thanks

to everyone's great advice, I'm starting to narrow down our choices for

our power

outage solar backup system. First of all, Joey

and Roland (and the web) helped me figure out what size system I should

be looking for. I added up two hours run time on our laptops,

router, and two lights and came up with 150 watt-hours per day.

Using Joey's math, or just dividing by the 3 peak sun hours our area is

rated to receive in the dead of winter (from the map above), we would

need a 50 watt solar panel to achieve our goal. Since it's bad

business to discharge your batteries more than halfway, we would need

to buy two Duracell Power Packs and two 25 watt panels to reach this

level --- total cost roughly $450.

For comparison's sake, I

followed Daddy's advice and gave Backwoods Solar a call. The salesman

there was happy to walk me through my choices, even though he clearly

wasn't going to make much money off me. Here are the components

and prices he quoted me for a 50 watt system:

- 50 watt solar panel - $275

- charge controller - $33

- 400 watt inverter - $45

- 2 RV or marine batteries (bought locally) - $180

He

also mentioned buying a tilt mount ($68), which would let us adjust the

panel's orientation seasonally for slightly higher output.

Assuming Mark could make our tilt mount, but that we would have to buy

some connectors not on the list, the total would come to around

$600. On the other hand, I suspect I could shave around $100 off

the cost by hunting down the components elsewhere on the web.

He

also mentioned buying a tilt mount ($68), which would let us adjust the

panel's orientation seasonally for slightly higher output.

Assuming Mark could make our tilt mount, but that we would have to buy

some connectors not on the list, the total would come to around

$600. On the other hand, I suspect I could shave around $100 off

the cost by hunting down the components elsewhere on the web.

In other words, the plug

and play version and the real DIY version have a comparable price

tag. But do they have comparable longevity? I asked the

Backwoods Solar salesman what he thought of using a 600 watt Duracell

Power Pack as our battery, controller, and inverter. "That would

probably work," he said (and I paraphrase), "if you're just going to

use it very ocassionally as a backup. However, if you'd like to

take the laptop and lighting loads permanently off the grid and run

your solar system daily, you would be better off with a different

battery."

Now, I trust that he knows

what he's talking about, but I don't quite understand why he would be

right. My research shows that AGM batteries have a rated lifespan

of 4 to 7 years while marine batteries have a lifespan of 1 to 6

years. In addition AGM batteries are sealed, which means no need

for us to fuss over them, worry about fumes, or freak out when I

accidentally knock them over. Finally, they can be shipped, so we

can shop around and buy the ones at rock bottom prices on Ebay.

As far as I understand it, the main disadvantage of an AGM battery is

price, but the cost of the Duracell Power Pack seems to be roughly

comparable to a marine battery when you consider that the former

includes a charge controller and inverterter.

Now, I trust that he knows

what he's talking about, but I don't quite understand why he would be

right. My research shows that AGM batteries have a rated lifespan

of 4 to 7 years while marine batteries have a lifespan of 1 to 6

years. In addition AGM batteries are sealed, which means no need

for us to fuss over them, worry about fumes, or freak out when I

accidentally knock them over. Finally, they can be shipped, so we

can shop around and buy the ones at rock bottom prices on Ebay.

As far as I understand it, the main disadvantage of an AGM battery is

price, but the cost of the Duracell Power Pack seems to be roughly

comparable to a marine battery when you consider that the former

includes a charge controller and inverterter.

So, I'm opening up to

questions and answers again. Can anyone think of a reason that

the Duracell Power Pack would have less longevity than a different

system? Currently, I'm leaning toward trying out one 25 watt plug

and play system, doubling it later if all goes well.

If some of your tomatoes

have a black spot on the bottom, chances are

they've come down with blossom end rot. This condition isn't

something to be overly concerned about since it's not caused by a

virus, bacterium, or fungus and won't travel beyond the fruit in

question.

Technically, blossom end

rot is caused by lack of calcium, but that

doesn't necessarily mean your soil is low on the essential

micronutrient. A variety of other

factors can reduce your plants'

ability to take up calcium, including drought, damage to the plant's

root system, excessive heat, or even rapid plant growth.

I'm not as careful as I

could be about making sure my tomatoes always

have an even supply of water, so I often find a fruit here and there

that has succumbed to blossom end rot. The affected plants are

most common at the beginning of the season, and are more prevalent in

certain varieties than in others. If blossom end rot seemed to be

excessively widespread in your garden, you should mulch your tomatoes

to maintain an even supply of

water in the soil and should take care not to overfertilize.

Otherwise, just cut out the spot and enjoy your homegrown tomatoes.

| This post is part of our Minor Tomato Ailments lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The new NcSTAR

red/green laser is now

mounted and ready for action.

It was easy to move the laser

dot to a desired location with just 2 adjustment screws.

The hard part will be

learning how to work within the limitations of the laser. I can already

tell you need to be lined up pretty straight otherwise the laser tends

to drift the further you tilt the angle up or down. There's also an 8mm

difference in the point of impact at 20 yards when you switch from

green to red, with the difference increasing as you increase the

distance. I think that can be solved by just using the green all the

time.

With a little practice I

think this laser aid can help to improve our accuracy under certain

conditions, but I think we should also be ready to take a shot without

the laser when the angle needs to be tilted beyond its range of

effective use.

I'm

not sure why no one talks about planting sunflowers for their honeybees

--- our bees adore them. We put in two beds of oilseed sunflowers

so that we could experiment with pressing

our own oil this

fall, but the flowers have already paid for themselves by feeding local

pollinators.

I'm

not sure why no one talks about planting sunflowers for their honeybees

--- our bees adore them. We put in two beds of oilseed sunflowers

so that we could experiment with pressing

our own oil this

fall, but the flowers have already paid for themselves by feeding local

pollinators.

During the day, it's not

at all unusual to catch several honeybees on

the same flower head, along with lots of smaller pollinators. The

action doesn't even stop when night falls --- yesterday, I snuck out at

dusk and found a moth on every flower, each dipping its proboscis deep

into the tiny florets opening around the circumference of the sunflower

head.

On a semi-related note,

if you're interested in native

pollinators and have

a bit of time on your hands, you might want to check out the Great

Sunflower Project.

Just plant a Lemon Queen Sunflower seed, watch the pollinators flock to

your flower for 15 minutes, and input your data to help scientists

figure out how pollinator populations are doing in your area. I

suspect this project would be especially good for science-oriented kids.

Cracking

is probably the most common tomato blemish out there. Like

blossom end rot, split tomatoes are often

the result of improper

watering, but the symptoms usually show up when the fruit is closer to

maturity.

Cracking

is probably the most common tomato blemish out there. Like

blossom end rot, split tomatoes are often

the result of improper

watering, but the symptoms usually show up when the fruit is closer to

maturity.

At a certain point in

the tomato ripening process, your fruit has

achieved its full size and it toughens up its formerly stretchable

skin. If a heavy

rain soaks the soil after the tomato epidermis hardens, the tomato can

swell

up further and crack its skin. Alternatively, cracks sometimes

occur when hot days are followed by cold nights, causing the skin to

expand and then contract quickly.

My advice is about the

same as it was for blossom end rot --- mulch if you're worried --- but

I tend

to think that cracking is just an inevitable fact of life. I cut

out hardened cracks and just eat soft cracks. Life's too

short to throw out a delicious tomato just because it has cosmetic

damage!

| This post is part of our Minor Tomato Ailments lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The

problem with chickens

roosting on the roof at

night is that the roof gets fertilized and the chickens avoid the small

coop where a guy like me has a fighting

chance at catching one for dinner the next morning.

The

problem with chickens

roosting on the roof at

night is that the roof gets fertilized and the chickens avoid the small

coop where a guy like me has a fighting

chance at catching one for dinner the next morning.

Maybe this sheet of tin will

keep them off tonight?

Our

garlic has had a good month plus of drying

time hanging under the eaves, so I decided it was time to clean it

up and move it inside for storage. I took down our strands of

garlic, rubbed the dirt out of the roots, and trimmed both roots and

leaves back. Next step was sorting --- I like to pull out the

very biggest heads for planting, and at the same time I set aside the

tiny or damaged heads for immediate eating. We've saved lots of

mesh bags from buying oranges and onions, so I popped each variety into

its own bag and put the whole mess on our scales.

Our

garlic has had a good month plus of drying

time hanging under the eaves, so I decided it was time to clean it

up and move it inside for storage. I took down our strands of

garlic, rubbed the dirt out of the roots, and trimmed both roots and

leaves back. Next step was sorting --- I like to pull out the

very biggest heads for planting, and at the same time I set aside the

tiny or damaged heads for immediate eating. We've saved lots of

mesh bags from buying oranges and onions, so I popped each variety into

its own bag and put the whole mess on our scales.

"How

many pounds of garlic do you think we grew this year?" I asked Mark

minutes later, wanting to brag.

"How

many pounds of garlic do you think we grew this year?" I asked Mark

minutes later, wanting to brag.

"Six pounds?" was his

less than ambitious reply.

"No!" I hooted.

"25.5, plus whatever we've eaten in the last month." Then, as the

wheels turned in my head, I added "That's half a pound of garlic per

week. Do you think we grew too much?"

Mark got a puzzled look

on his face --- clearly, the idea of too much garlic had never occurred

to him. "Of course not," he answered. "You'd better get

cooking!" Garlic green beans for supper it was.

Green

shoulders are the most purely cosmetic problem I'll discuss. I

have certain tomato varieties --- notably this yellow roma and our

pear-shaped "black" tomato --- that ripen the bottom two

thirds of the fruit quickly, but leave the top third green. My

solution, as usual, is to cut off the tops

and give them to the chickens, but I was interested to discover there's

a reason for the green shoulders.

Green

shoulders are the most purely cosmetic problem I'll discuss. I

have certain tomato varieties --- notably this yellow roma and our

pear-shaped "black" tomato --- that ripen the bottom two

thirds of the fruit quickly, but leave the top third green. My

solution, as usual, is to cut off the tops

and give them to the chickens, but I was interested to discover there's

a reason for the green shoulders.

Green shoulders form

when tomatoes deal with high temperatures and

strong sunlight during ripening. The light and heat prompt the

fruits to retain

chlorophyll around the stem area, and the "shoulders" often become hard

and leathery.

Unless you've pruned

excessively and removed leaves that would normally

shade your fruits, you haven't done anything to cause green

shoulders. And there's not much you can do to fix the "problem"

either, short of ripening your tomatoes indoors or choosing a different

variety. This is definitely one of those times I'm glad not to be

a market gardener whose customers demand blemish-free fruit.

| This post is part of our Minor Tomato Ailments lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Yesterday's

roof

roosting prevention tin

worked well to persuade the remaining pasture flock to sleep in the

coop last night.

Yesterday's

roof

roosting prevention tin

worked well to persuade the remaining pasture flock to sleep in the

coop last night.

Now the mother hen and

chick have the whole

place to themselves and we have enough farm raised chicken to last most

of the winter.

We

killed the rest of our broilers this week, and while we were at it we

deleted our three Plymouth

Rocks for failing to

meet their egg quota. The farm feels very quiet without them.

We

killed the rest of our broilers this week, and while we were at it we

deleted our three Plymouth

Rocks for failing to

meet their egg quota. The farm feels very quiet without them.