archives for 05/2010

Friday

was my reward for a long week spent

weeding and preparing the garden. I finally put out the first of

our tender vegetables, plants that can't bear the frost and that will

be coming up around the time of our frost free date. Reading

straight off my spreadsheet, I ended up planting in alphabetical order

--- basil, beans, cantaloupe, corn, cucumbers, garbanzos, okra,

peppers, quinoa, summer squash, urd beans, and watermelon. Even

tenderer plants will be hitting the dirt in a couple of weeks.

Friday

was my reward for a long week spent

weeding and preparing the garden. I finally put out the first of

our tender vegetables, plants that can't bear the frost and that will

be coming up around the time of our frost free date. Reading

straight off my spreadsheet, I ended up planting in alphabetical order

--- basil, beans, cantaloupe, corn, cucumbers, garbanzos, okra,

peppers, quinoa, summer squash, urd beans, and watermelon. Even

tenderer plants will be hitting the dirt in a couple of weeks.

Even

though the 80 plus degree heat wore us

out fast, my Mexican sombrero let me keep moving long enough to slip

some summer flowers into gaps in the forest garden. Last year, I

finally threw flower seeds in the ground in June, and was stunned by how they

brightened my day in October. Mark points out that

with bees

in our lives, it only makes sense to take a few minutes and plant

flowers, so I raked back the mulch in a few sunny gaps and dropped in

seeds of Mexican sunflower, pink and white cosmos, zinnias, marigolds,

fennel, sunflowers of two varieties, a bumblebee

habitat mix (thanks, Jennifer!), and asters (thanks, Mom!) Except

for the last two, these are tried and true flowers that bear my neglect

admirably and bloom with no care from me.

Even

though the 80 plus degree heat wore us

out fast, my Mexican sombrero let me keep moving long enough to slip

some summer flowers into gaps in the forest garden. Last year, I

finally threw flower seeds in the ground in June, and was stunned by how they

brightened my day in October. Mark points out that

with bees

in our lives, it only makes sense to take a few minutes and plant

flowers, so I raked back the mulch in a few sunny gaps and dropped in

seeds of Mexican sunflower, pink and white cosmos, zinnias, marigolds,

fennel, sunflowers of two varieties, a bumblebee

habitat mix (thanks, Jennifer!), and asters (thanks, Mom!) Except

for the last two, these are tried and true flowers that bear my neglect

admirably and bloom with no care from me.

This is the first year

we're growing garbanzos, and the seed packet confused me. It told

me that garbanzos are a cool season crop like peas, and then combined

that with an admonition to plant them after the frost free date.

Um? Has anyone grown them? When did you plant them?

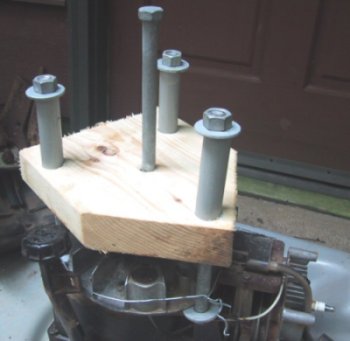

Don't forget to drill pilot

holes through the wheelbarrow

frame and the new 2x2 handle.

I placed another section of

2x2 on the other side with a pilot hole only half drilled to give the

new screws something to bite onto without splitting anyone's grain.

So

you lost your bet on the Kentucky Derby? Don't despair --- we're

holding a betting contest you're much more likely to win! And

this one is chicken related --- aren't chickens better than horses?

So

you lost your bet on the Kentucky Derby? Don't despair --- we're

holding a betting contest you're much more likely to win! And

this one is chicken related --- aren't chickens better than horses?

If you're interested,

you can read about our

plans for creating several rotational pastures for our broilers, complete with food-bearing

perennials. We'll be rotating our chickens through future

pastures every couple of weeks so that they don't demolish the

vegetation, but we want them to scratch this first pasture up pretty

good so that we can sow it with grains for their winter diet.

When will the ground become bare enough to plant in?

Post your guestimate

date in the comments, and whoever is closest will win bee

balm and Egyptian onions. Both plants are hardy

perennials that need next to no care and either attract bees and

hummingbirds (the bee balm) or feed you for ten months

out of the year (the Egyptian

onion.)

For

the scientific minded among you, here's some more data to help you

choose the very best date. Our chicken pasture is about 800

square feet and holds 25 birds who will be six weeks old on Monday, May

3. They've been eating at the pasture since April 23, and have

already started to scratch their most traveled spots bare. On the

other hand, they have been concentrating their attention on less than

half of the area so far and haven't really found the far corner

yet. I've been adding wheelbarrow loads of weeds every few days,

and am feeding them about a gallon of food a day. (They're hungry

little birds!) All of the photos in this entry were taken Friday

and are relatively representative of the pasture at this moment.

It's built around a big wild cherry that is starting to leaf out, so

the vegetation is weeds that do well in partial shade, not grass.

For

the scientific minded among you, here's some more data to help you

choose the very best date. Our chicken pasture is about 800

square feet and holds 25 birds who will be six weeks old on Monday, May

3. They've been eating at the pasture since April 23, and have

already started to scratch their most traveled spots bare. On the

other hand, they have been concentrating their attention on less than

half of the area so far and haven't really found the far corner

yet. I've been adding wheelbarrow loads of weeds every few days,

and am feeding them about a gallon of food a day. (They're hungry

little birds!) All of the photos in this entry were taken Friday

and are relatively representative of the pasture at this moment.

It's built around a big wild cherry that is starting to leaf out, so

the vegetation is weeds that do well in partial shade, not grass.

The fine print: The

ground will be considered bare enough when I randomly decide it's bare

enough. Only one guess per person, please!

Sometimes an old fashioned

shovel beats out a fancy roto tiller.

Big, thick, Poke root extraction is a task that

needs someone to invent a solution for in the form of a tiller like

machine. Maybe it will somehow use a small, flexible auger to chase

down and grind up any unwanted roots within a 4 foot deep perimeter?

Hopefully it'll be easier

to start up than our tiller was last year.

This

beautiful mushroom popped out of the half-buried log bounding one side

of our three year old peach raised bed. I've been piling

weeds and dirt along the sides of the raised bed every year, but was a bit concerned

that the peach roots would get stuck inside and not make it out into

the surrounding soil. Clearly, some fungi are hard at work

breaking those logs down into prime compost and clearing the way for

the peach roots' expansion.

This

beautiful mushroom popped out of the half-buried log bounding one side

of our three year old peach raised bed. I've been piling

weeds and dirt along the sides of the raised bed every year, but was a bit concerned

that the peach roots would get stuck inside and not make it out into

the surrounding soil. Clearly, some fungi are hard at work

breaking those logs down into prime compost and clearing the way for

the peach roots' expansion.

For a few minutes, I

thought this might be a wild oyster

mushroom, enhancing

the edibility of our forest garden. But my best guess at the

moment is Smooth Panus (Panus

conchatus), a

relative of the oysters, but one which has edibility listed as "tough

but apparently harmless." I guess I'll let the mushroom work in

peace, although I'm tempted to harvest the dozens of insects hiding in

the gills for chicken feed.

Last week, I discussed how micronutrient

deficiencies in our soil make even homegrown vegetables less nutritious

than they were a few decades ago. Steve Solomon's

solution to this problem is to enrich his soil with what he calls

"complete organic fertilizer." Gardening

When It Counts gives

you some leeway in blending this fertilizer, but the gist of the recipe

is as follows:

Last week, I discussed how micronutrient

deficiencies in our soil make even homegrown vegetables less nutritious

than they were a few decades ago. Steve Solomon's

solution to this problem is to enrich his soil with what he calls

"complete organic fertilizer." Gardening

When It Counts gives

you some leeway in blending this fertilizer, but the gist of the recipe

is as follows:

- 4 parts seedmeal

- 1 part lime. (The best mixture is a quarter agricultural lime, a quarter gypsum, and half dolomite lime. If you're only using one type, dolomite is best because it includes both calcium and magnesium.)

- 1 part finely ground rock phosphate, bonemeal, or high-phosphate guano

- 0.5 to 1 part kelpmeal or 1 part basalt dust

The recipe is mixed by volume

and results in a fertilizer with NPK of

5:5:1, along with substantial amounts of the most important

micronutrients. Solomon says that not only does complete organic

fertilizer result in balanced nutrient levels in the soil, it is also

easy for beginning gardeners to deal with and doesn't require hauling

so much bulk to your farm.

The recipe is mixed by volume

and results in a fertilizer with NPK of

5:5:1, along with substantial amounts of the most important

micronutrients. Solomon says that not only does complete organic

fertilizer result in balanced nutrient levels in the soil, it is also

easy for beginning gardeners to deal with and doesn't require hauling

so much bulk to your farm.

I was leery of the price

tag attached to Solomon's mixture, but he says

that the ingredients are relatively cheap when purchased at feed

stores. He spends about $300 per year buying

the components, and gets $4,000 to $8,000 worth of vegetables in

return. Solomon uses a gallon to a gallon and a half of his

complete organic

fertilizer on every 100 square feet of garden, then adds the same

amount again as side-dressing on his higher demand vegetables.

This fertilizer is in addition to a quarter inch coating of compost

added to the garden each year.

Before you all rush out

to buy seedmeal, here are some potential disadvantages of complete

organic fertilizer:

- The price tag is still considerably higher than buying enough compost to reach the same fertility level.

- Complete organic fertilizer doesn't add much organic matter, which is a definite problem if you have a clayey garden like mine.

- Lime should be used with care when gardening over limestone, the

way we are. Your soil will probably already be somewhat alkaline

and may be very high in calcium and magnesium. Do a soil

test before adding any lime!

All of those warnings

aside, I suspect some of you might like to give

complete organic fertilizer a shot. If you do, please check back

and let me know how your experiment went!

This post is part of our Gardening When It Counts lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

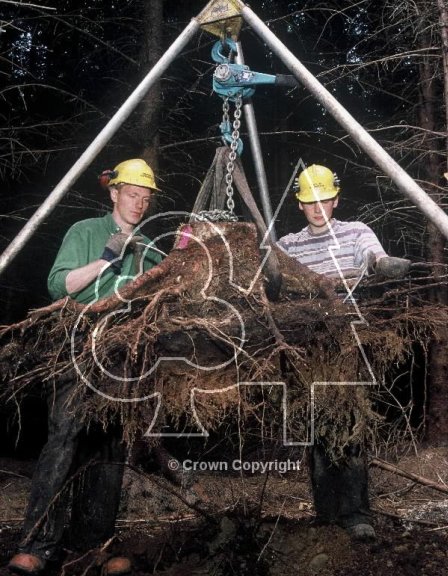

Thanks goes out to Roland for pointing me in the winch/tripod direction for any future heavy

root extraction.

With any luck our Poke roots won't get as big as this

Sitka

Spruce root in Scotland.

Some

days, my life lacks coherence and is simply an unending string of awed

discoveries. Here's Monday in a nutshell....

Some

days, my life lacks coherence and is simply an unending string of awed

discoveries. Here's Monday in a nutshell....

I woke to the sound of

rushing water --- the floodplain is submerged.

A scuffle in the hallway

--- Huckleberry caught a mouse.

Blueberry

bushes are coated in hundreds of flowers, some starting to open.

Blueberry

bushes are coated in hundreds of flowers, some starting to open.

Seven male toads

beckon lovers from our mushroom soaking kiddie pool.

Tiny fuzzball peaches

are swelling fast, now bigger than my thumbnail.

Stir-fry for dinner ---

dozens of Egyptian onions, some overwintered carrots and parsnips, and

shiitakes sodden from three plus inches of rain.

The first lightning bugs

danced in the dark.

I hope your spring days

are as sweet!

How do large logs get moved

on a remote log cabin construction site that has no power or heavy

machinary?

Gas powered winch of course.

The one on the right will cost you about 800 bucks and hooks up to most

chainsaws. The bigger one comes with it's own engine and will run you

over 1300 dollars.

A good equipment rental store

might rent these out for around 50 bucks a day, which would be well

worth it if you're trying to carve out a log cabin structure in the

middle of nowhere.

That style of building would

qualify as extreme homesteading in most people's book.

Ever

since I read that traditional

Guatemalan farmers use young elderberry leaves as mulch

around their vegetables, I've been aching to give it a shot...and to

figure out why they focus on elderberries rather than on other

trees. The answer to that question may be a combination of early

leafing, compound leaves that are easy to pull off the trunks and quick

to decompose, and elderberry's inherent resilience. I've been

mowing over some elderberry sprouts in the mule garden for three years

now, and they just keep coming back up (and spreading), so I'm not

concerned that I'll harm my shrubs by pulling off a few leaves.

Ever

since I read that traditional

Guatemalan farmers use young elderberry leaves as mulch

around their vegetables, I've been aching to give it a shot...and to

figure out why they focus on elderberries rather than on other

trees. The answer to that question may be a combination of early

leafing, compound leaves that are easy to pull off the trunks and quick

to decompose, and elderberry's inherent resilience. I've been

mowing over some elderberry sprouts in the mule garden for three years

now, and they just keep coming back up (and spreading), so I'm not

concerned that I'll harm my shrubs by pulling off a few leaves.

Tuesday I decided to

strip the patch of elderberries by the barn as part of my neverending

search for more mulch.

The big leaves broken off quickly and easily --- if I had a good-sized

plantation of elderberries, I might not need any other source of mulch.

After I ran out of

elderberries, I moved on to the box-elders that are still sprouting up

from stumps along the garden edges. These leaves took longer to

harvest, but not by much. I just closed my gloved hand around the

base of a small branch and pulled my way to the tip, stripping off all

the leaves in my path. The result is a little bin of leaves that

densely covered a couple of raised beds.

At the moment, it looks

like my

eventual solution to the weeding problem will be to try to keep my beds

under a near permanent mulch rather than spacing

the plants far enough

apart that they can be hoed. But Solomon is very

anti-mulch ---

disturbing since he's been spot on about so many other things.

Maybe mulching isn't such a good idea after all?

Solomon lists half a dozen

disadvantages of permanent mulching.

His biggest gripe is the "plague levels of small animals" that move

into the mulch if you don't live in a cold enough climate. I

assume he's talking about moles and voles and shrews here, and I feel

extraordinarily lucky that Lucy is a small animal killer and doesn't

let any of these survive in our garden.

Solomon lists half a dozen

disadvantages of permanent mulching.

His biggest gripe is the "plague levels of small animals" that move

into the mulch if you don't live in a cold enough climate. I

assume he's talking about moles and voles and shrews here, and I feel

extraordinarily lucky that Lucy is a small animal killer and doesn't

let any of these survive in our garden.

Solomon's other

arguments against mulch don't carry as much weight with

me. He notes that if you use hay, you end up with a lot of weeds

--- so don't use hay. If your summers aren't hot enough or if

your mulch is too woody, it won't rot into the bed before summer and

will tangle with your hoe --- but you shouldn't need to hoe much if

your bed is well mulched. Mulched garden soil is slower to warm

up in the spring than bare earth --- so rake the mulch off a few weeks

before you need to plant your earliest crops. He thinks that

adding too much compost

or mulch to your soil will result in soil

nutrients out of balance,

which will make your food less nutritious --- so use dynamic

accumulators to reachieve that balance.

Proponents of mulch

argue that the practice conserves water, but

Solomon makes the legitimate point that most water lost from the soil

comes out of plant leaves, not from bare soil. He points out that

mulching only

keeps the soil surface moist and doesn't reduce overall moisture

loss. On the other hand, I would argue that mulching does prevent

soil crusts from forming (something that Solomon considers a big

problem in his garden) and allows more water to soak in rather than

running off in clay soil. I suspect that overall, mulch results

in a net gain of moisture for the plants in our garden.

So far, our experiments

with mulch over the last year have been highly successful, but I'll

keep all of Solomon's arguments in mind and will be willing to give up

on mulching if I start to see major disadvantages.

This post is part of our Gardening When It Counts lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

A solid 25 pound brick of

chicken yummyness was acquired in the big city today for about 13 bucks.

Stay tuned for a full report

on how the new

chicks respond to the

Purina Flock Block.

Our

beekeeping mentor (aka our movie star neighbor) called to remind me

that the first major nectar

flow of the year is

about to begin. "The Black Locusts and Tulip-trees are starting

to bloom," he warned. "Be sure to put an extra super on your

hives!"

Our

beekeeping mentor (aka our movie star neighbor) called to remind me

that the first major nectar

flow of the year is

about to begin. "The Black Locusts and Tulip-trees are starting

to bloom," he warned. "Be sure to put an extra super on your

hives!"

So I suited up and

headed out to check on our honeybees. Although the nectar trees

are blooming at our mentor's nearby house, our shady farm is a bit

behind and the bees were miffed at my intrusion into their lives.

Nevertheless, I was able to see that all three hive bodies were full of

brood and pollen, and that one of the hives had filled the first super

and started on the second. I popped a third super on our

strongest hive, remembering with a smile how one beekeeper I met told

me that he likes to add plenty of supers to a hive. "It can't

hurt," he said, "And everyone passing by will think you must be an

amazing beekeeper to need room for so much honey!"

At the other extreme,

one of our hives was down to its last small frame of honey. The

queen in this hive started laying about a week later this spring than

the queens did in the other two hives, and I suspect it's just taken

the late queen longer to raise enough workers to sock away honey rather

than consuming it. I'll check on them again next week and give

them a bit of spare honey if necessary.

Did you know that proper

watering is a lot more complicated than providing your garden with that

critical one inch of water per week? To figure out the best

watering method for your area, first figure out how much water needs to

be lost before vegetables are stressed using the chart below:

| Soil type |

Amount of

water lost before vegetables experience moisture stress (inches of

water per foot of soil) |

| Sandy |

0.5 to 0.75 |

| Medium |

1 |

| Clayey |

1.5 |

Next, pick out your climate zone from this chart:

| Climate zone |

Inches of

soil moisture lost per sunny day in the summer |

| Cool (western Washington) |

0.2 |

| Moderate (northern U.S.) |

0.25 |

| Hot and humid (mid-Atlantic and

southeastern U.S.) |

0.3 |

| Hot and dry (prairies and

northern California) |

0.35 |

| Low desert (southwestern U.S.

and California) |

0.45 |

Then plug your numbers into this formula:

For example, in our clayey soil in the hot and humid climate zone:

So, every fifth day, I need to add 1.5 inches of water back to the soil. My father, who lives in the hot and humid zone too but has sandy soil, may need to water every day or two but will add less water each time.

Of course, to maintain a perfect watering schedule, you need to keep track of weather conditions. On cloudy days, the soil doesn't lose much water, so you can wait an extra day to water. When it rains, the amount of precipitation can be added back into the soil's supply, putting off watering even longer.

As further evidence that Steve Solomon and I

are on the same wavelength, Gardening

When It Counts gives

the same irrigation advice I do --- buy high

quality impulse sprinklers and ditch the trendy drip

irrigation.

Solomon notes that drip irrigation equipment is expensive, short-lived,

troublesome, easy to cut

through, and prone to shifting away from the plants it's meant to

water; and doesn't work in sandy soil because the

water won't spread horizontally; but is potentially good for permanent

plantings like

raspberries.

As further evidence that Steve Solomon and I

are on the same wavelength, Gardening

When It Counts gives

the same irrigation advice I do --- buy high

quality impulse sprinklers and ditch the trendy drip

irrigation.

Solomon notes that drip irrigation equipment is expensive, short-lived,

troublesome, easy to cut

through, and prone to shifting away from the plants it's meant to

water; and doesn't work in sandy soil because the

water won't spread horizontally; but is potentially good for permanent

plantings like

raspberries.For other prime gardening advice --- like why you should never water seedlings --- go read the book!

This post is part of our Gardening When It Counts lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

After almost 3 weeks of

waiting, the new Briggs

and Stratton flywheel puller arrived in the mail and today was

the day to put it into action.

I was planning on having

pictures of the operation and maybe a short video, but all that went

out the window when I realized my mistake in ordering the wrong

flywheel puller.

At least I know which one we

don't need. Hopefully with a bit more homework I can determine exactly

which flywheel puller is needed for this particular Craftsman.

Mom

picked up another half dozen bags of yard waste along her city curb

and brought it out to me last weekend. "It smells foul," she

warned me. "I think there might be dog poop in it, or something

awful."

Mom

picked up another half dozen bags of yard waste along her city curb

and brought it out to me last weekend. "It smells foul," she

warned me. "I think there might be dog poop in it, or something

awful."

She was right that the

grass clippings and autumn leaves stunk to high

heaven, but when I opened the bags and sent my gloved hands feeling

around, all I came across were some sodden bits. My best guess is

that a gardener bagged up his refuse last summer, then tossed the bags

into the garage and forgot about them. The moisture in the leaves

started some anaerobic decomposition and resulted in a stink, but no

real harm was done.

I'd been

meaning to hill my potatoes --- you're supposed to hill them

at four inches, and they somehow leapt from three inches to a foot this

week --- but decided to use Ruth Stout's method instead and just put my

spoiled grass clippings and leaves on top of the raised beds.

Technically, I'm not really following her lead since I planted the

potatoes in normal soil, but I've read that planting potatoes straight

into spoiled hay really only works when you've built up wonderful

garden soil, and I was planting in new beds. Take a look at the

embedded video to see a 90 year old Ruth Stout in her garden, or skip

ahead to 7 minutes into the video to see her planting potatoes.

In other potato news, I

should mention that the potato plants I covered

with

buckets during the last frost are three times bigger than

the ones I

let the frost nip. On the other hand, the beds that I let the

chickens work on for five days instead of three days have potato plants

twice as big as the

other beds, even though the fomer were uncovered during the

frost. I'm

guessing the boost of nitrogen let them grow large enough not to mind

the cold weather.

Thanks, Mom, for the

time-saving mulches!

For those of you who don't like numbers ---

thanks for slogging through this technical lunchtime series. I've

saved the best for last!

For those of you who don't like numbers ---

thanks for slogging through this technical lunchtime series. I've

saved the best for last!

In a previous

incarnation, Steve Solomon was the founder of Territorial Seeds, so

it's no surprise that his personal experiences with seed companies and

seed storage are the most powerful part of the book.

He explains that most seeds sold to the home gardener are low quality,

primarily because most of us don't know any better. ("Those seeds

didn't come up? Oh, I must have done something wrong!")

Nearly all seed

companies catering to our demographic simply buy bulk seed, repackage

it in pretty envelopes, and sell it for high prices. Only a few

seed companies either grow their own seeds or perform large seed trials

to ensure that the seeds they're selling are the proper variety, are

vigorous, and have high germination rates. Without these tests,

you could end up in the same boat I was in last year --- I bought some

Goldbar Hybrid seeds from Jung last year, and ended up with a squash

that looked nothing like the picture on the website.

Steve Solomon contacted

dozens of seed companies to inquire about their growing methods, and

came up with these few recommended suppliers for the United

States. He notes that you'll get the best results by buying from

a company in your climate zone.

- Northern U.S. -- Stokes, Johnny's

- Middle U.S. --- Stokes, Johnny's, Harris, Southern Exposure Seed Exchange (with the caveat that SESE stocks a lot of relatively unproductive heirlooms)

- Southeast U.S. --- Park

(which is currently going through bankruptcy and may end up a worse

company)

- Maritime U.S. --- Territorial

I've always wondered

which seed companies were good and which ones were not, so I'm glad to

finally read an in depth analysis without lots of guesswork!

This post is part of our Gardening When It Counts lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

I just noticed this back door

to the chicken

pasture Lucy installed

recently and growled at her while I stitched it back together.

We could double down on

securing the bottom edge with some additional fastening, or hook up the

electric fence charger and run a strand at nose height all along the

perimeter.

Another option would be to

stop giving the pastured chickens any scraps and divert that nutrition

to the chicken

tractors or worm bin.

None of these choices work

for me because they avoid the root problem of Lucy's failure to

recognize that all food scraps belong to us and she needs special

permission to access even a banana peel.

It may seem like a tall order

to train a dog to fight the urge to eat something yummy, but I've seen

it happen before and feel that Lucy is serious about doing her part in

being a team player.

We just need to discover

where the communication is breaking down and put some extra effort in

explaining this critical lesson.

Torrential rains last

weekend hastened germination of the previous

week's planting.

First came the corn, then the green beans.

A day or two later, I

noticed a strange little seedling that looked like a weed but was

growing in straight rows. I checked my garden map and discovered

that the seedlings were one of this year's experiments --- urd beans

for sprouting.

Scorching temperatures

(highs near 90) tempted even the extreme heat-lovers out of the

ground. By Friday, a few of the okra, melons, and cucumbers were

up.

But these plants are all

gambles, put in the ground two weeks before the frost-free date, and I

suspect this will be a year for replanting. There's a good chance

of frost both tonight and tomorrow night, and I probably don't have

enough row covers to protect everyone. What were the odds we'd

get a redbud

winter, dogwood winter, and blackberry winter all

in one year? Probably pretty good considering that our frost free

date is still a week away.

Despite relying on complete

organic fertilizer

as his primary source of soil nutrients, Steve Solomon is clearly an

expert compost-maker. For those of us who use a slapdash approach

to composting, Solomon's composting description in Gardening

When It Counts is a

must-read. He explains that a good compost has more than 1.5%

nitrogen, a C:N ratio no higher than

15:1, and lots of micronutrients.

Despite relying on complete

organic fertilizer

as his primary source of soil nutrients, Steve Solomon is clearly an

expert compost-maker. For those of us who use a slapdash approach

to composting, Solomon's composting description in Gardening

When It Counts is a

must-read. He explains that a good compost has more than 1.5%

nitrogen, a C:N ratio no higher than

15:1, and lots of micronutrients.

The

carbon to nitrogen ratio, often shortened to "C:N" or "C/N" is at the

heart of building a perfect compost heap. The availability of

nitrogen in the compost is largely determined by this ratio, which can

be thought of as a bit like the pH scale. A C:N ratio of 12:1

(twelve parts carbon to one part nitrogen) is "neutral" --- this is the

C:N ratio of soil humus and is relatively stable. Most plant

matter has a C:N ratio higher than 12:1, which means that decomposing

microorganisms require a net input of nitrogen while they're

breaking down the first of the carbon --- this is why putting fresh

wood chips on your garden does more harm than good, locking up the soil

nitrogen for the first few years before the chips break down (and their

C:N ratio drops low enough) so that they begin releasing

nitrogen. On the other end of the spectrum, chicken manure has a

C:N ratio of about 6:1, which means that the manure provides nitrogen to the soil, and

actually breaks down soil humus in the process. The table below

lists the C:N ratios of various compostables. For immediate use

on your garden, you can mix and match until the C:N ratio of your pile

is around 15:1.

| 6:1 or lower |

12:1 |

25:1 |

50:1 |

more than

100:1 |

| Meat scraps Chicken manure Hair/feathers Urine (0.8:1) |

Vegetables Garden weeds Horse manure (no bedding) Cow manure (no bedding) Spring grass Garden soil Comfrey leaves Coffee grounds |

Summer grass Legume hulls Fruit waste Grass hay (green) |

Cornstalks (dry) Straw (cereal) Grass hay (poor) Corrugated cardboard Tree leaves (deciduous) Autumn grass |

Sawdust (500:1) Paper (175:1) Tree bark Pine needles |

Luckily for those of us with large masses

of high C:N waste, a compost

pile's C:N ratio will slowly drop over time as microorganisms break down

the carbon-based compounds and make nitrogen more available. If

you mix an incipient compost with a C:N ratio of 30:1 into warm soil,

for example, it will break down in about six weeks. Compost

grinders and tumblers will expedite the process, but your compost will

overheat in the process and you will lose a lot of your nutrients as

gases like methane, ammonia, and carbon dioxide. Steve Solomon

instead recommends composting slowly, starting a pile in the fall,

turning it when the apples bloom, and then turning it again a month

later if it's not done.

Luckily for those of us with large masses

of high C:N waste, a compost

pile's C:N ratio will slowly drop over time as microorganisms break down

the carbon-based compounds and make nitrogen more available. If

you mix an incipient compost with a C:N ratio of 30:1 into warm soil,

for example, it will break down in about six weeks. Compost

grinders and tumblers will expedite the process, but your compost will

overheat in the process and you will lose a lot of your nutrients as

gases like methane, ammonia, and carbon dioxide. Steve Solomon

instead recommends composting slowly, starting a pile in the fall,

turning it when the apples bloom, and then turning it again a month

later if it's not done.One of my favorite things about Steve Solomon's book is that it's full of numbers and formulas. Here's his favorite recipe for compost:

- Spread garden and kitchen waste in a pile 5 to 7 feet across, five feet long, and eight inches thick.

- Add half an inch of good garden soil (to inoculate

microorganisms.)

- Add a low C:N component --- 5 to 10% of the mass of layer 1 if you're using poultry manure or cow or horse manure with no bedding, or 2 to 5% if you're using seed meal.

- Water well.

- Repeat steps 1 through 4 until the pile is 4 to 6 feet tall.

- Cover the pile with a thin layer of soil.

This post is part of our Gardening When It Counts lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

I

figure if the ramshackled

wheel barrow makes it through its first week back on the job then

its got a bright future here on the farm.

I

figure if the ramshackled

wheel barrow makes it through its first week back on the job then

its got a bright future here on the farm.

No complaints from its main

operator after several heavy trips.

I predict this fix to last

around 2 years.

While we were gone on

our honeymoon last fall, our deterrents

got stuck and the deer ate the recently transplanted strawberries down

to the ground. This spring, the plants grew so slowly, I lost

faith. After seeing the size of my father's plants a zone or two

south in April, I figured our measly plants wouldn't give much of any

strawberry harvest this year.

Then came warm weather,

and our strawberry plants grew like crazy. Before I knew it, they

were big and blooming, then the little fruits started to swell.

And now the first strawberry is blushing pink! Maybe we'll be

eating luscious strawberries by the end of the week.

Homegrown strawberries

are a lot like homegrown tomatoes --- once you eat one, you'll never

touch storebought again. No, I won't share. Plant your own!

I

thought I would end my wheelbarrow

thread with an extreme

version that cost a bit over a hundred dollars.

I

thought I would end my wheelbarrow

thread with an extreme

version that cost a bit over a hundred dollars.

What I like most about this

flavor is the ability to lay it flat on the ground to ease loading.

It's way more wheelbarrow

than we need around here, but I can't help but to admire the design.

I run across these

interesting pupa now and then when I dig around in my garden in the

spring. They're hard and shiny, seemingly sound asleep, but then

the tail end begins to rotate slowly when you pick the pupa up.

Disturbing.

I usually don't go in

for wholesale destruction of insects, but for some reason I got it into

my head that these pupa were the overwintering stage of the squash vine

borer. So I

fed every one I found to my chickens (who were very

appreciative.) A bit of research doesn't turn up any images of

squash vine borer pupa, but does show several hawk and sphinx moth pupa

that look a lot like this. If I remember, I'll stick the next one

I find into a jar and see what hatches out. Any better ideas?

When

I was a youngster, our nearest neighbor's front yard was decked out

with a

huge tire, painted white and filled with flowers. A metal glider

and chairs, also painted white, stood nearby under the shade of a large

catalpa, just waiting for a visitor to come by and sit for a

spell. There were flowers --- nearly all annuals that were easy

to grow from seed, like marigolds and cockscomb --- and a blooming

bush. Across the yard was a pen of chickens, then the barn, and

in the other direction was the vegetable garden, laid out in straight

rows. The couple clearly spent considerable time, though little

money, keeping their yard in impeccable shape.

When

I was a youngster, our nearest neighbor's front yard was decked out

with a

huge tire, painted white and filled with flowers. A metal glider

and chairs, also painted white, stood nearby under the shade of a large

catalpa, just waiting for a visitor to come by and sit for a

spell. There were flowers --- nearly all annuals that were easy

to grow from seed, like marigolds and cockscomb --- and a blooming

bush. Across the yard was a pen of chickens, then the barn, and

in the other direction was the vegetable garden, laid out in straight

rows. The couple clearly spent considerable time, though little

money, keeping their yard in impeccable shape.

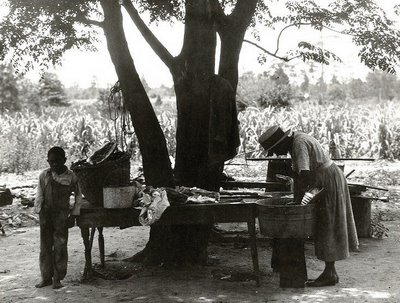

Although my neighbors

were white, their space could have graced the pages of Richard

Westmacott's African-American

Gardens and Yards in the Rural South,

with the notable lack of a hog butchering station and a swept dirt

floor. Westmacott analyzed the yards of 47 rural families

spread across

Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina, focusing on folks who had reached

or passed middle age. If there was such a thing as a traditional

Southern, African-American garden, he wanted to find it.

And he did see similarities,

many noted in my opening paragraph.

Rather than being showcased landscapes, the yards were subsistence

gardens

where work and leisure intermingled. In most cases, the yard had

become an extension of the house, the spot for a family barbecue or hog

butchering session.

And he did see similarities,

many noted in my opening paragraph.

Rather than being showcased landscapes, the yards were subsistence

gardens

where work and leisure intermingled. In most cases, the yard had

become an extension of the house, the spot for a family barbecue or hog

butchering session.

But where did the

similarities come from? Could they be traced

back to the families' heritage in western Africa, to their slave

background, or were the similarities simply the common byproduct of

being poor

in the South?

| This post is part of our African-American Gardens and Yards in the

Rural South lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

How dare you talk about extreme

wheelbarrows without mentioning the Honda HP450 power carrier!

Norman, Phoenix Arizona

I stand corrected.

Norman is right, this Honda HP450 is one tough cookie.

I wonder if you could modify

it to accept some sort of seat where you could sit and steer the thing

to your jobsite, get out and put the seat aside till the work gets

done, and then drive it back to the truck?

Photo credit goes to the good

folks at IMBA for this great shot of the HP450 in action during a

trail building day.

Everything

I do in the garden at this time of

year is a gamble. Will a late frost negate my efforts?

Or will I get away with pretending summer weather is here to stay and

reap an early harvest?

Everything

I do in the garden at this time of

year is a gamble. Will a late frost negate my efforts?

Or will I get away with pretending summer weather is here to stay and

reap an early harvest?

I've been eying our peach tree for weeks as the ovaries

began to swell

and resemble miniature fruits. If nothing goes wrong, this year

will be our first harvest and I've resolved to thin the fruits even

though thinning is really optional.

On the negative side,

thinning takes time, and if you thin and then get a heavy, late frost,

you will lose a lot of your crop. On the other hand, timely

thinning is supposed to result in fruits that are bigger and sweeter,

and will reduce the chance of limbs breaking under the fruits'

weight. I've read that you get about the same weight of fruit

whether you thin or not; it's your choice whether you want a lot of

small fruits that are mostly pit or fewer big fruits.

As long as you don't

think you'll have any more below freezing weather,

the earlier you thin the better since the tree will now be pumping all

of its energy into the chosen fruits. Extension service websites

tell you to thin peaches to six to eight inches apart, but I couldn't

quite bear to take off so many fruits and instead settled on about four

to five inches between peaches. I still pulled a full quart of

immature fruits off our oldest peach, and a smattering from our younger

peach and nectarine. I'm trying very, very hard not to count my

peaches before they hatch...um, ripen.

Westmacott

perused accounts and photos of western Africa from the eighteenth and

nineteenth centuries, searching for similarities between historical

African gardens and current

African-American

gardens in the rural South. Western Africa is a

diverse area, ranging from rainforest to subtropical desert, and the

agricultural heritage of west Africans is similarly diverse. Some

people were nomadic herders, others had grain-based diets much like our

own, while still others practiced what Westmacott called "vegeculture"

but which I would call forest

gardening --- edible

trees, roots, vines,

and grains all mashed together into one space.

Westmacott

perused accounts and photos of western Africa from the eighteenth and

nineteenth centuries, searching for similarities between historical

African gardens and current

African-American

gardens in the rural South. Western Africa is a

diverse area, ranging from rainforest to subtropical desert, and the

agricultural heritage of west Africans is similarly diverse. Some

people were nomadic herders, others had grain-based diets much like our

own, while still others practiced what Westmacott called "vegeculture"

but which I would call forest

gardening --- edible

trees, roots, vines,

and grains all mashed together into one space.

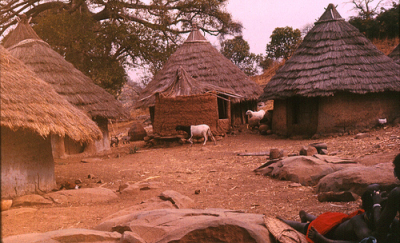

West Africans who grew

what we now consider traditional gardens

typically clustered their houses into fenced compounds. They

grazed any livestock they might happen to have outside during the day,

but took the animals in at night. Crops were grown outside the

village compound in intensively tilled and manured land, while trees

with edible fruits (like bananas, coconuts, and mangos) were planted

within the village for shade.

As you can probably

guess from my previous lunchtime series on Chinese

and Central

American traditional gardening practices, I was intrigued

by this look into traditional African agriculture. But very few

of the African practices seemed to carry over to the United

States. Shade trees are ubiquitous in African-American yards in

the South, but the trees are not edibles, and there is no sign of

forest gardening.

The one aspect of the

southern gardens that Westmacott felt confident

tracing back to Africa was the swept yard. Although inexpensive

motorized lawnmowers are now pushing swept yards into history, many of

the old timey African-American families in Westmacott's study stuck to

the traditional bare earth yard. The families spent time every

day

hoeing weeds out of the yard, then sweeping every bit of trash and

debris out of the living space. The result was an area where

children could play and adults could easily sit and talk, without

danger of snakes or ticks. The practice can be clearly traced

back to Africa, not only because Africans still keep up swept yards,

but also because bare earth yards just don't work in more temperate

climates. In areas without long dry seasons a swept yard will

turn to mud and become impassable for a large portion of the

year. I guess we won't be making a swept earth yard here!

| This post is part of our African-American Gardens and Yards in the

Rural South lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

This is the 4th breach

of security for the chicken

pasture perimeter thanks

to Lucy and her naughty behavior.

Since the spring mowing and

future fence building is starting to crunch our time I think I'm

leaning more towards that nose high stretch of electric fence wire as a

new method of keeping her out.

With any luck Lucy will get

the message right away and reclaim her title as best dog in the galaxy.

If you peruse the homesteading and serious

gardening blogosphere at this time of year, you'll see that most of us

are clinging to our sanity by dirty fingernails. I went through

my own little meltdown last week:

If you peruse the homesteading and serious

gardening blogosphere at this time of year, you'll see that most of us

are clinging to our sanity by dirty fingernails. I went through

my own little meltdown last week:

Mark: "You know, we're better off than we were at this time last year. Cheer up --- you said you wanted things to grow, and they're growing."

For those of you who are

in the midst of gardening frenzy, I hope you can take Mark's advice

(along with a deep breath) and enjoy the beauty of spring.

Remember, there's always winter to catch up on all of those important,

long term projects, and it does seem to help to let the weeds grow up

and hide problem spots you aren't going to have time to deal with this

year. Right now, I figure we're doing well if we manage to tread

water and not sink much further behind than we already are.

On the other hand, if

you're living vicariously through our blog, now's when you can snicker

in your cubicle....

Westmacott

explained that gardening practices of slaves in the American South were

almost as diverse as those

in Africa.

Slaves unlucky enough to

live in upland regions tended to be worked from sunup to sundown under

the heavy thumb of an overseer --- they usually had no time to tend

their own garden, and were seldom allowed to keep livestock for their

own consumption. The "luckier" slaves on large plantations along

the coast were often given a daily quota of chores to pursue at their

own speed, and if they were fast and hard-working, they could make time

to grow their own vegetables and keep a hog and chickens. The

families craved this bit of self-sufficiency, which could mean the

difference between malnutrition and relative health.

Westmacott

explained that gardening practices of slaves in the American South were

almost as diverse as those

in Africa.

Slaves unlucky enough to

live in upland regions tended to be worked from sunup to sundown under

the heavy thumb of an overseer --- they usually had no time to tend

their own garden, and were seldom allowed to keep livestock for their

own consumption. The "luckier" slaves on large plantations along

the coast were often given a daily quota of chores to pursue at their

own speed, and if they were fast and hard-working, they could make time

to grow their own vegetables and keep a hog and chickens. The

families craved this bit of self-sufficiency, which could mean the

difference between malnutrition and relative health.

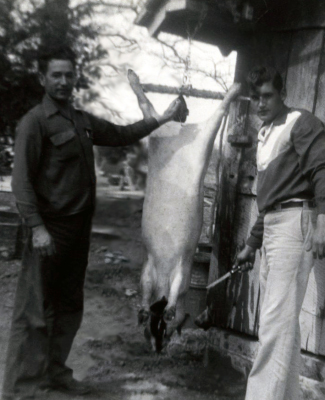

A focus on pigs and

chickens as a path to meat self-sufficiency carries

through to the modern day in the African-American families Westmacott

interviewed.

Many of the families had either hogs, chickens, or both, and hog

butchering stations in nearly all of the yards showed that the families

not currently keeping pigs used to. Despite the daunting size of

a full-grown pig, about half of the families still slaughtered their

own hogs, explaining that butchers won't return ears and chitterlings,

which the families like to cook with.

Pigs and chickens (and

mules, nearly all of which have been replaced by

tractors and rototillers) made the traditional Southern,

African-American family very self-sufficient. Families used to

feed their food scraps and excess produce to the animals and get meat

and manure in return. This homesteading feature is quickly

disappearing, with purchased fertilizers and grocery store meat now

cheap enough that families see little need to keep their own livestock.

| This post is part of our African-American Gardens and Yards in the

Rural South lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

This nose high strand of

electric fence wire will help to keep Lucy out and any other stray

critters that might be a potential threat when she takes her random

naps.

Despite being a

vegeholic, I have to admit that the prettiest part of the

garden right now is the flowers. Our chamomile and columbine are

in

full bloom, and the first brilliant red poppy unfurled its petals

Wednesday morning. It's hard to walk through the yard without

having my eyes drawn to that splash of red.

But the most exciting

flower is white and relatively small, sitting atop a pea vine.

Juicy pods are now only days away, and they promise to spice up our

current garden diet of lettuce, greens, pea

tendrils, kale

flowers, mushrooms, Egyptian onions, parsley, fresh eggs, and

slightly woody overwintered carrots and parsnips. The best thing

about eating in season is that when you're starting to get sick of

collards every day, something new pops up to tempt your palate.

Perhaps

the most important factor influencing

African-American

gardens in the rural South --- and the hardest to

disentangle from other potential factors --- is poverty. If you

were born black in America, you are nearly three times as likely to

live in poverty as if you were born white. Many of the "unique"

aspects of African-American gardens are ones I grew up with in my own

area, since Appalachia is nearly as poor as the so-called "Black Belt"

further south.

Perhaps

the most important factor influencing

African-American

gardens in the rural South --- and the hardest to

disentangle from other potential factors --- is poverty. If you

were born black in America, you are nearly three times as likely to

live in poverty as if you were born white. Many of the "unique"

aspects of African-American gardens are ones I grew up with in my own

area, since Appalachia is nearly as poor as the so-called "Black Belt"

further south.

Poor people tend to have smaller houses,

so it's no surprise that their

yards act as an extension of their living space. Even though most

of the families in Westacott's study now have electricity and running

water, many continued to use the back porch and/or the area around

their well as a center of cooking and washing. Anyone who has

cooked in the South in the summer without air-conditioning can

understand why you might want to can, make soap, or even fry up your

dinner outside over a fire rather than heating up the whole

house. And if you've been crammed into five hundred square feet

with five other human beings, you might choose to shell the peas

outside under a shade tree too.

Poor people tend to have smaller houses,

so it's no surprise that their

yards act as an extension of their living space. Even though most

of the families in Westacott's study now have electricity and running

water, many continued to use the back porch and/or the area around

their well as a center of cooking and washing. Anyone who has

cooked in the South in the summer without air-conditioning can

understand why you might want to can, make soap, or even fry up your

dinner outside over a fire rather than heating up the whole

house. And if you've been crammed into five hundred square feet

with five other human beings, you might choose to shell the peas

outside under a shade tree too.

Westacott noted that

"piles of temporarily discarded or

recently-acquired-for-some-unspecified-use-in-the-future materials are

commonplace on most small farms and rural properties." See, that

trash heap by our barn is just a sign of frugal ingenuity! The

author explained that similar piles grace most of the properties he

visited, for use in building animal pens and fixing other objects

around the farm. The families he visited even used found art to

brighten up their front yards, lining their paths with colored bottles

and tacking hubcaps to the fence.

| This post is part of our African-American Gardens and Yards in the

Rural South lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

In looking for ideas to

expand our outdoor worm

farming I found this

clever use of a discarded bathtub as a medium sized worm bin at the pleasant lifeboat.co.nz.

We've decided to give this

approach a try along with a few others so we can determine which one is

most trouble free.

If you've got a good source

of horse manure then you really need to put a

small army of worms to work on that manure to speed up the composting

action and take advantage of that wonderful worm tea. It's one of those

things we neglected to set aside time to build back in the beginning, but sometimes it takes a while to wake up to the wonders of worm assisted home grown

compost.

I'm

afraid our chicken

pasture contest is a

bit of a wash. As the weeds grow taller and taller and our pudgy

chickens become slower and slower, it's becoming clear that there will

be no scratching the earth bare at this rate. Our Dark

Cornish chickens

don't seem to be as avid foragers as I'd hoped they'd be, although they

do like picking through the huge mound of weeds I keep wheelbarrowing

into their pasture.

I'm

afraid our chicken

pasture contest is a

bit of a wash. As the weeds grow taller and taller and our pudgy

chickens become slower and slower, it's becoming clear that there will

be no scratching the earth bare at this rate. Our Dark

Cornish chickens

don't seem to be as avid foragers as I'd hoped they'd be, although they

do like picking through the huge mound of weeds I keep wheelbarrowing

into their pasture.

What

you all probably care about the most is --- who wins?! I've

decided to name Bethany our grand prize winner since she picked the

furthest away date which is closest to infinity. Bethany, drop me

an email with your address and your onions and flowers will be in

the

mail next week.

What

you all probably care about the most is --- who wins?! I've

decided to name Bethany our grand prize winner since she picked the

furthest away date which is closest to infinity. Bethany, drop me

an email with your address and your onions and flowers will be in

the

mail next week.

The more scientific

among you may be asking --- what now? I still want to have the

chickens scratch up some of the earth to expedite grain planting, so

we're going to subdivide their current pasture in hopes that a smaller

enclosure will actually get scratched bare. Given the proximity

of butchering day,

we may wait to build more pastures until next year, and will be

rethinking our broiler experiment --- maybe we'd be better off having

the slow, fat broilers in tractors and our perky layers achieving self

sufficiency on pasture? Stay tuned for future experimentation!

Other

common features in African-American gardens in the rural South were

probably also linked

to poverty.

Although potted plants were

common --- presumably a remnant of a transient past --- nearly all

gardening was extensive

instead of intensive.

Only one gardener

of the 47 families studied used raised beds, and hers were really

vegetables grow in tire

planters.

Other

common features in African-American gardens in the rural South were

probably also linked

to poverty.

Although potted plants were

common --- presumably a remnant of a transient past --- nearly all

gardening was extensive

instead of intensive.

Only one gardener

of the 47 families studied used raised beds, and hers were really

vegetables grow in tire

planters.

In most of the gardens

Westmacott studied, plants were spaced far apart in rows and were

seldom watered except

during transplanting. Although records from earlier

African-American gardens showed the ubiquity of rain barrels, current

gardeners tended to rely solely on rain and to believe that drought was

God's

will.

Mulching and composting

were nearly absent from the gardens.

Instead, weeds were removed by cultivation, often with a hoe but

sometimes with a tractor or mules. One gardener explained that

cultivation brought moisture to the surface for the plants (although I

can't quite figure out how this makes scientific sense.)

Mulching and composting

were nearly absent from the gardens.

Instead, weeds were removed by cultivation, often with a hoe but

sometimes with a tractor or mules. One gardener explained that

cultivation brought moisture to the surface for the plants (although I

can't quite figure out how this makes scientific sense.)

In the end, I'm

disappointed that I can't extract any permaculture

techniques from the African-American gardens, but they do seem to prove

Solomon's point. People who value yield over beauty, who garden

on a shoestring budget to feed their families, do seem to practice

extensive gardening.

| This post is part of our African-American Gardens and Yards in the

Rural South lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Since the do

it yourself golf cart dump box is working out so well we've

decided the Heavy

Hauler garden cart can

start its new carreer as a large

outdoor worm bin.

It took less than an hour to

scrounge around for the parts and put it all together.

The spigot was salvaged from

a thrift store drink dispenser. (Thanks

Mom)

I used a couple of 2x2's cut

to 30.5 inches for the bottom support and modified a portion of the willow wall to function as the floor. A small

gap at the bottom helps to prevent the spigot from clogging and worms

from drowning in their own tea.

Being on heavy wheels makes

it easy to manuever and tilt for the most effecient drainage

When

I checked the bees at the beginning of May,

I was a bit concerned about one colony. The hive was chock full

of

brood, but had only one shallow frame of honey, a vast reduction in

stores since the last time I checked. Would the bees keep

consuming honey and starve despite the nectar flow?

When

I checked the bees at the beginning of May,

I was a bit concerned about one colony. The hive was chock full

of

brood, but had only one shallow frame of honey, a vast reduction in

stores since the last time I checked. Would the bees keep

consuming honey and starve despite the nectar flow?

A few days later, I

noticed a lot of aimless activity in front of that

hive. Usually, a busy hive is like an airport with lots of

takeoffs and landings, but this hive had a bunch of circling workers

just wandering around in the air. I'm pretty sure I caught the

orientation flight of new foraging workers getting their bearings so

that they'd know which hive was their home.

Sure enough, a hive

check on May 13 showed that my hungry hive was

honeyless no longer. The bees were drawing out comb and filling

it with nectar just as fast as their sister hives, making me think that

we may need to make plans for our first honey

harvest soon.

In

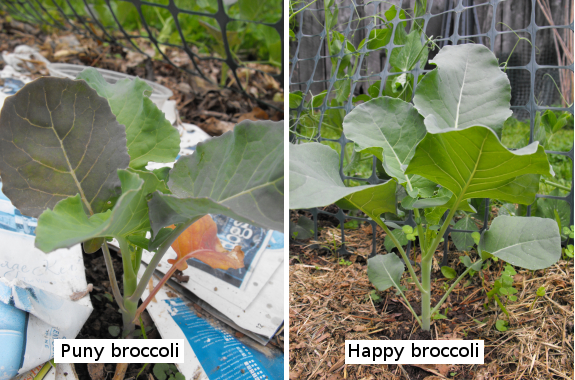

the last couple of weeks, "bad bugs" have started to show up in the

garden. This guy is a "cabbage worm" (aka Cabbage White

caterpillar) and it enjoys gobbling big bites out of our broccoli and

cabbage plants.

In

the last couple of weeks, "bad bugs" have started to show up in the

garden. This guy is a "cabbage worm" (aka Cabbage White

caterpillar) and it enjoys gobbling big bites out of our broccoli and

cabbage plants.

My approach to cabbage

worm control is pretty lackluster, but it seems to work --- I handpick

the caterpillars whenever I happen to notice them, then feed them to

the chickens. If you're going to head out to check your plants,

look for the dark pellets of frass (poop) on leaves, then lean in

closer and hunt down the caterpillar who left the traces behind.

Cabbage worms like to orient their bodies parallel to veins, making

them difficult to find without the tell-tale frass.

I

spend even less time worrying about flea

beetles. Tiny

black specks hopping around on the potatoes alerted me to their

presence last week and a close look showed that the potato leaves are

now perforated with hundreds of tiny holes. But the plants don't

seem to mind, so I'm ignoring the flea beetles.

I

spend even less time worrying about flea

beetles. Tiny

black specks hopping around on the potatoes alerted me to their

presence last week and a close look showed that the potato leaves are

now perforated with hundreds of tiny holes. But the plants don't

seem to mind, so I'm ignoring the flea beetles.

I don't mean to suggest

that all "bad bugs" are harmless or easy to deal with. I'm still picking

asparagus beetles

every week, hoping to put a dent in their population and save our

fronds, and I know that we'll be battling squash vine borers all

summer. But I hope that you'll consider a more laissez-faire

approach to bad bugs, at least until they prove themselves a major

hindrance to your garden.

We've

had issues with using a broody hen to hatch eggs in the past, and our current experiment

(which I'll outline in detail at lunch) was only minimally

successful. But the idea has so much merit from a homesteading

perspective that we'll keep plugging away until we make it work.

We've

had issues with using a broody hen to hatch eggs in the past, and our current experiment

(which I'll outline in detail at lunch) was only minimally

successful. But the idea has so much merit from a homesteading

perspective that we'll keep plugging away until we make it work.

For example, look at

this --- a mother hen teaching her chick to forage on day two!

They spent the first day hunkered down in the nest, but by midafternoon

Sunday, the Cochin had led the way to the ground and was scratching up

worms. She picked up each wriggler, clucked over it

enthusiastically, then dropped it at the chick's feet. Granted,

the chick was less than sure what to do with this largesse, but I still

think such early exposure will turn it into an awesome forager.

If that's not enough to

convince you of the utility of the natural approach to chick-rearing,

consider how much electricity we'll be saving by not having to run an

incubator for three weeks and then a heat

lamp for another

month. After following its mother around the brood coop for ten

minutes, the chick decided it was chilly, so it poked at its mother's

feathers, then tunneled underneath the hen and disappeared.

Best yet, I've

discovered that I can delegate most of the worrying to the mother

hen. Yes, we will definitely be trying the broody hen approach

again, and I have high hopes the third time will be the charm.

When

we were in South Carolina last month, Daddy gave me eleven fertilized

Rhode Island Red eggs to try to hatch out. I brought them home

and started preheating the incubator, only to discover that the cheap

brand we'd gotten at the feed store only works if you keep your room

temperature very constant. So I made a spur of the moment

decision and popped the eggs in the brood coop with our White Cochin instead.

When

we were in South Carolina last month, Daddy gave me eleven fertilized

Rhode Island Red eggs to try to hatch out. I brought them home

and started preheating the incubator, only to discover that the cheap

brand we'd gotten at the feed store only works if you keep your room

temperature very constant. So I made a spur of the moment

decision and popped the eggs in the brood coop with our White Cochin instead.

Regular

readers may remember that we tried a similar experiment last fall, with

the result that our

hen killed the only chick that hatched. But I wanted to give

our hen another chance before putting her on the dinner table, figuring

she may have killed her first batch of chicks because their color made

it obvious that they weren't her own. Rhode Island Red chicks are

pale, so color wouldn't be an issue this time around.

Regular

readers may remember that we tried a similar experiment last fall, with

the result that our

hen killed the only chick that hatched. But I wanted to give

our hen another chance before putting her on the dinner table, figuring

she may have killed her first batch of chicks because their color made

it obvious that they weren't her own. Rhode Island Red chicks are

pale, so color wouldn't be an issue this time around.

I added a lip to her

culvert nest so that none of the eggs would roll out, then I threw the

hen in the coop. I'd heard her make a broody moan the week

before, but she wasn't really broody yet and it took her most of the

week to decide the eggs were worth sitting on. By then, I figured

our chances of getting a hatch were close to nill, so I didn't even

post about it, but I left the hen to sit on the nest since I figured I

might as well get the broodiness out of her system.

Saturday

morning, I dropped by to toss in a bit of feed...and saw a fluffy chick

running in and out of the Cochin's feathers! I moved the automatic chicken waterer into the culvert nest at

chick eye level and tossed in some chick feed, and the peep immediately

followed the mother's lead, eating and drinking. It seems quite

healthy, and the Cochin has clearly accepted it, so the only question

now is...will it be a new layer or a broiler? And have I finally learned enough that next time we'll get a good hatch rate?

Saturday

morning, I dropped by to toss in a bit of feed...and saw a fluffy chick

running in and out of the Cochin's feathers! I moved the automatic chicken waterer into the culvert nest at

chick eye level and tossed in some chick feed, and the peep immediately

followed the mother's lead, eating and drinking. It seems quite

healthy, and the Cochin has clearly accepted it, so the only question

now is...will it be a new layer or a broiler? And have I finally learned enough that next time we'll get a good hatch rate?

| This post is part of our Farm Experiments lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I decided to use an old piece

of tin to shore up the chicken

pasture gate.

Putting a strand

of electric wire across the gate bottom would make getting in and

out of the pasture a small hassle.

After several days of basking

in the sun the solar fence box seems to have a weak battery, which

means our next step will be to spring for the 40 dollar electric fence

charger.

We

have a horrible time with most of our cucurbits. Even before the

squashes fall prey to the vine borer, the cucumbers and

canteloupes come down with powdery mildew. Or maybe it's cucumber

mosaic or bacterial wilt. All I know is that the plants start to

bloom, then they keel over.

We

have a horrible time with most of our cucurbits. Even before the

squashes fall prey to the vine borer, the cucumbers and

canteloupes come down with powdery mildew. Or maybe it's cucumber

mosaic or bacterial wilt. All I know is that the plants start to

bloom, then they keel over.

I've never seen data to

back this up, but many organic gardeners

believe that pest and disease infestations originally stem from ill

health on the part of your crop. The idea makes sense --- if we

don't eat a well-rounded diet, we're more likely to catch a cold, so

why wouldn't the same

be true of our cucurbits?

Following this

reasoning, I top-dressed all of our baby cucurbits with a hearty scoop

of compost, hoping to perk them up so they'll outgrow their diseases

(and the weeds.) Native Americans used a similar idea when they

planted squash on hills of dirt over fresh fish. Maybe I'll get

lucky this year and taste our first home-grown canteloupe?

The

tomato

blight of 2009 left

me close to tears last summer, and with a serious

craving for red sauce this spring. This year is also a tomato

seed turning point. I last saved seeds in 2007, assuming that I

could collect more in 2009, but I didn't manage to harvest any tomato

seeds before the blight hit. This spring, my three year old seeds

had low germination percentages, so I absolutely must have ripe

tomatoes to save seeds from this year or I'll have to rebuild my

collection of the

tastiest and most utilitarian tomato varieties from scratch.

The

tomato

blight of 2009 left

me close to tears last summer, and with a serious

craving for red sauce this spring. This year is also a tomato

seed turning point. I last saved seeds in 2007, assuming that I

could collect more in 2009, but I didn't manage to harvest any tomato

seeds before the blight hit. This spring, my three year old seeds

had low germination percentages, so I absolutely must have ripe

tomatoes to save seeds from this year or I'll have to rebuild my

collection of the

tastiest and most utilitarian tomato varieties from scratch.

So I'm experimenting

with spacing, location, and timing in search of a

blight-free tomato harvest. The goal of the first two experiments

is to allow lots of sunlight and air movement around the plants so that

they'll dry off quickly after rains. To that end, I've planted

all of our tomatoes in the sunniest part of the garden, and am doubling

the spacing between plants to three feet. In addition, we'll be

individually staking the plants and pruning off the suckers to promote

even speedier drying.

Meanwhile,

I'm trying three different planting

times/ages. I've discovered in the past

that young seedlings started

in a cold frame then

transplanted to the garden do better than

leggy

tomato plants that have been struggling on a windowsill for

months. So the majority of my plants have just been transplanted

out at

the two sets of true leaves stage.

Meanwhile,

I'm trying three different planting

times/ages. I've discovered in the past

that young seedlings started

in a cold frame then

transplanted to the garden do better than

leggy

tomato plants that have been struggling on a windowsill for

months. So the majority of my plants have just been transplanted

out at

the two sets of true leaves stage.

On the other hand, my

neighbors believe in buying big transplants and

putting them out earlier, covering the plants with bottomless milk jugs

during cold spells and hoping that they will bear at least some harvest

before blight sets in. A volunteer tomato came up in our lemon

pot in the sunroom this spring, and I decided to transplant it out into

the garden on April 21 to see how its growth compares to that of my

younger transplants --- it's currently big and hefty, with about six

pairs of true leaves.

Finally, my father

likes to tell me that he once direct-seeded tomatoes into the garden

after all danger of frost was past and still got harvests nearly as

quickly as from transplants. So I filled the last tomato spot

with ten seeds and will weed the seedlings down to the strongest one

once its up. Will it catch up with its transplanted

siblings? Only time will tell.

If all else fails, I

have one last trick up my sleeve. One

volunteer tomato plant survived the blight of 2009, and I carefully

saved its seeds to add to my collection. I have high hopes that

at least this one variety will be resistant enough to give me a

crop. Here's hoping something works!

| This post is part of our Farm Experiments lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

It only took about 2 minutes

to install an eye hook on the port and starboard side of the do

it yourself golf cart dump box.

Now we have tie down points

to attach a bungee cord to for easy snugging.

Once

you've been gardening in an area for a while, you'll start seeing

volunteer vegetables. Unless they're impinging on the space of a

beloved crop, I often leave volunteers at least for a while, as a sort

of insurance against catastrophe in other parts of the garden.

But Mom reminded me that blight overwinters in left behind

potatoes,

and that my volunteers are vectors of infection. Oops! I

ripped out those volunteers as fast as I could, hoping I hadn't let the

blight loose on our farm again.

Once

you've been gardening in an area for a while, you'll start seeing

volunteer vegetables. Unless they're impinging on the space of a

beloved crop, I often leave volunteers at least for a while, as a sort

of insurance against catastrophe in other parts of the garden.

But Mom reminded me that blight overwinters in left behind

potatoes,

and that my volunteers are vectors of infection. Oops! I