archives for 04/2010

I finally planted the

first of the hedges I've been talking about all

winter. For this initial stage, I'm simply starting a solid mass

of Osage-Orange, with plans to intersperse

other hedge plants in gaps at a later date. Osage-Orange was a

no-brainer as the hedge base since this first hedge is in the floodplain (optimal Osage-Orange

habitat, but likely to kill many other plants due to the waterlogged

soil.) The trees will be liberally decked with thorns and will

form a prickly, impenetrable barrier that works well at keeping animals

in. In addition, the seeds are reputed to be edible to humans and

beloved by squirrels, so maybe the eventual inhabitants of the forest

pasture will get something to eat from the Osage-Orange.

The

first step in the Osage-Orange process was a unique type of

stratification. I put the fresh Osage-Orange fruits in a sink in

the shade and let them soak up the rain and snow all winter. When

I went to look at them Wednesday morning, the result was not

appetizing, but the weather had done its job. I was able to mash

the fruits up easily with the trake,

exposing the seeds to view. (The pulp is pretty stinky --- you might

want to wear gloves for this step if you're following along at home.)

The

first step in the Osage-Orange process was a unique type of

stratification. I put the fresh Osage-Orange fruits in a sink in

the shade and let them soak up the rain and snow all winter. When

I went to look at them Wednesday morning, the result was not

appetizing, but the weather had done its job. I was able to mash

the fruits up easily with the trake,

exposing the seeds to view. (The pulp is pretty stinky --- you might

want to wear gloves for this step if you're following along at home.)

Next, I created a very

basic mound where I wanted the hedge to go. Internet sources

suggest planting Osage-Orange seeds in a shallow trench, but I've

learned my lesson with other trees --- nothing grows directly in the

ground in damp spots on our farm. I smeared the Osage-Orange goo

liberally across the turned over sod, planting thickly so that the tree

seedlings will be able to compete with the weed roots I was too lazy to

remove from the soil. I didn't cover the seeds, though maybe I

should have? If I see any squirrels at work, I'll head back down

and cover them up. For future reference, my sinkful of fruits

created about two gallons of pulp, which in turn seeded about 35 feet

of hedge.

In

addition to our grains for human consumption, I plan to incorporate

some grains into the non-forested part of our new chicken

forest

pasture. I'll

let the chickens scratch up one of the flat areas

well, then turn the birds into another paddock while I broadcast

buckwheat, millet, and perhaps corn seeds into the distressed

ground. After three months, I'll be able to rotate the chickens

which we plan to keep for the winter into the grain paddock so that

they can supplement their winter foraging with grains.

In

addition to our grains for human consumption, I plan to incorporate

some grains into the non-forested part of our new chicken

forest

pasture. I'll

let the chickens scratch up one of the flat areas

well, then turn the birds into another paddock while I broadcast

buckwheat, millet, and perhaps corn seeds into the distressed

ground. After three months, I'll be able to rotate the chickens

which we plan to keep for the winter into the grain paddock so that

they can supplement their winter foraging with grains.

I've already outlined

the method for growing

buckwheat and

everyone

knows how to grow corn. But how do you grow millet?

Unfortunately, several different species (each in their own genus, so

only vaguely related) are called by the name "millet" and each has its

own growing requirements. Pearl millet has the largest seeds

and the advantage of threshing free from its hulls naturally, but pearl

millet also requires warm

temperatures and may not set seed in cold climates. Proso millet

can be grown in cooler areas since it requires only 60 to 90 days to

mature, and Titus emailed me that her chickens adore the seeds so I

suspect the hull doesn't bother them. Have you grown millet in

your garden? If so, what kind, and how did it do?

| This post is part of our Homegrown Whole Grains lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Step 2: Decide on location,

choose and trim suitable cedar posts, and install.

Step 3: Catch your breath and

have a glass of ice tea.

Warm

weather dried up the creek enough that I was able to haul in a golf

cart load of the storebought

compost that Mark so valiantly gathered in

the big city. I'm afraid I hurt his feelings when I arrived back

at the trailer --- he was expecting exuberant hugs, but I was actually

a bit disappointed by the compost's quality.

Warm

weather dried up the creek enough that I was able to haul in a golf

cart load of the storebought

compost that Mark so valiantly gathered in

the big city. I'm afraid I hurt his feelings when I arrived back

at the trailer --- he was expecting exuberant hugs, but I was actually

a bit disappointed by the compost's quality.

The color is a beautiful

dark brown, but the compost's structure is heavier than I would like

and the smell is musty instead of earthy. Since it was mixed and

aged in a warehouse, the usual beneficial microorganisms seem to be

absent (thus the lack of a woodsy aroma). I think the heaviness

is due to the high proportion of chicken manure in the compost, which

results in a very high N-P-K for compost

(3-4-4), but less organic matter than I'd like. My holy grail of

compost is the sponge-like stump

dirt I gather in the

woods, and I'm

beginning to think that type of compost may be impossible to create on

an industrial level.

In loamy soil,

a compost high in fertility and low in organic matter would be fine, but in my clay I

need the organic matter even more than the fertility. Luckily,

the bulk of my garden won't be going into the ground for 4 to 8

weeks, so I've got time to rectify the compost's disadvantages.

I'm going to sprinkle the compost over the top of my leaf

mulch in the

May garden beds and hope that the influx of nitrogen will make those

leaves compost quickly. I use no-till

techniques, so my soil is

brimming with decomposers and ready to take on the job!

The last component of this year's grain

experiment is equipment. Backyard gardeners often skip growing

grains because of the complicated harvesting,

threshing, winnowing, and dehulling procedures. But Home-grown

Whole Grains

introduced two pieces of DIY equipment that I'm putting on my honey-do

list.

The last component of this year's grain

experiment is equipment. Backyard gardeners often skip growing

grains because of the complicated harvesting,

threshing, winnowing, and dehulling procedures. But Home-grown

Whole Grains

introduced two pieces of DIY equipment that I'm putting on my honey-do

list.

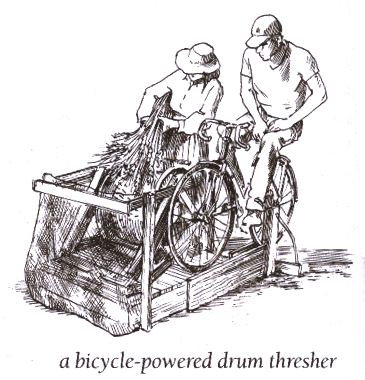

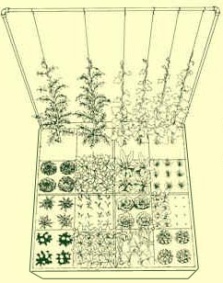

The first is a

pedal-power drum thresher --- I've stolen the picture from the book

just this once because I can't find anything like it on the

internet. Basically, a bicycle is hooked up to a utility-wire

spool. The spool is inside a collection bin of some sort and is

studded with xd nails, pounded in every two to three inches. One

person pedals, which causes the drum to spin, while another person

holds the grain heads against the drum. The nails pull seeds

out of the grain heads relatively quickly --- you can thresh about 40

pounds of grain in an hour with the DIY thresher.

If you're growing a

grain that has difficult to remove hulls (like buckwheat), you'll be

interested in Southern

Exposure Seed Exchange's method of converting a hand-cranked

grain mill into a DIY huller. Basically, you temporarily replace

the stationary disk on your grain mill with a rubber disk made by

gluing soft rubber onto a washer. With a bit of adjustment, your

mill will be able to crack the hull on seeds without breaking the grain

kernels. I can't find any pictures of this apparatus on the

internet either, but once we grow our buckwheat I'll give it a shot and

post about it.

| This post is part of our Homegrown Whole Grains lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Estimated cost of the chicken

pasture coop so far is somewhere between 1 to 2 dollars for a

handful of sheet rock screws.

The salvaged brackets

continue to prove themselves as a flexible fastener, especially when you have a good size

hammer to help preach your philosophy of bracket transformation.

In

the last week and a half, our three beehives have been churning out the

babies. Last time I checked on them, two hives

had a little bit of brood,

but now all three hives have brood of all ages on several frames.

They're also packing away pollen like nobody's business, and are

starting to dehydrate nectar into new honey. None of them have

started using the second super yet, though --- maybe once the fruit

trees and dandelions really start blooming.

In

the last week and a half, our three beehives have been churning out the

babies. Last time I checked on them, two hives

had a little bit of brood,

but now all three hives have brood of all ages on several frames.

They're also packing away pollen like nobody's business, and are

starting to dehydrate nectar into new honey. None of them have

started using the second super yet, though --- maybe once the fruit

trees and dandelions really start blooming.

In other pleasant news,

the raised brood cell that I thought might be

an incipient queen cup in one hive earlier in March turned into a bit

of drone brood (the few bumps in the photo above), which means I

haven't crowded the hive too much. I went ahead and opened all of

the brood boxes up, though, to stave off any feelings of overcrowding

in the near future. "Opening up the brood box" sounds confusing,

but it's actually quite simple --- just take the empty frames that

naturally gravitate to the sides of the box and intersperse them

between frames full of brood and pollen. As you leaf through the

opened brood box from one end to the other, it now reads "empty, full,

empty, full, empty, full, empty, full, empty, full" rather than "empty,

empty, full, full, full, full, full, empty, empty, empty." The

theory is that if the queen has empty frames near her, she won't think

she's running out of space, so she won't instigate a swarm. Hives

that don't swarm produce a lot more honey, so swarm prevention is key

to getting a good harvest.

In February, I got

concerned that our two weaker hives might be running low on honey,

so I stole three frames from the strongest hive to give them

backup. When I checked this week, though, the strongest hive had

eaten nearly every drop of its copious honey, presumably fueling the

huge egg-laying campaign it has embarked on. So I moved two small

frames of honey back from one

of the weaker hives to the strongest hive. This type of maneuver

is a sure sign of a far-too-hands-on beekeeper, but I can't help being

a nervous nellie about our livestock.

One detail to note is the

placement of an Avian Aqua

Miser in respect to new chicks.

I started off with one in

each corner on the starboard side of the box. The height turned out to

be a problem when all 24 chicks decided to crowd into that corner

during a brief

fire episode. The chicks

who were bunched up close to the nipple were activating the valve and

dumping water on themselves and their immediate neighbors. I'm no

expert, but wet chicks on a cold night sounds a bit too close to a

country western song for my comfort level.

The lesson is to avoid corner

placements of your automatic

chicken waterer for the first couple of weeks. After that you

should be able to raise the waterer to avoid any such issues in the

future.

Meet

our newest dwarf citrus --- Washington Navel Orange. Isn't she

cute?

Meet

our newest dwarf citrus --- Washington Navel Orange. Isn't she

cute?

Unfortunately, she is

the textbook definition of rootbound. One large root had

literally grown all the way around the perimeter of the pot...although

the plant had eschewed the stagnant dirt in the pot's bottom.

When I asked Mark

to buy me a pot, he came up with the absolutely best pot

possible. Notice how shallow and wide this pot is? No more

wasted soil on the bottom of the citrus pot!

I teased the orange's

roots out and planted the tree in a mixture of partially decomposed

horse manure and storebought

compost. I

usually try to use worm castings or stump

dirt for repotting,

but I'm all out! If the little orange tree seems to be

struggling, I'll pop it back out and hunt down some better soil.

One obvious omission to the do

it yourself table top brood coop is the lack of a front or back

door.

The chicks have a moving day

planned for tomorrow as soon as I fence in a small segment of the new

chicken pasture coop building. That's when I'll remove one of the

brood coop panels and cut out a door opening so they can be free to

come and go during the day as their nap schedule permits.

Photo credit goes to the

intriguing heyburton blog,

who has an interesting article on chicks

doing some low level math.

Plant

a fruit tree and learn patience. You'll tend them and love them

for three years, or four years, or five years before tasting the first

sampling of their fruit. But then the harvest will steadily grow,

until within a decade you have buckets and barrels full of apples,

pears, peaches, and plums.

Plant

a fruit tree and learn patience. You'll tend them and love them

for three years, or four years, or five years before tasting the first

sampling of their fruit. But then the harvest will steadily grow,

until within a decade you have buckets and barrels full of apples,

pears, peaches, and plums.

At least that's the

dream. Our first stab at making it a reality

failed when we planted fruit trees directly into our wet clay soil and

ended up with so many dead sticks. So we planted again in 2007,

this time in raised beds, starting small as we

figured out what we'd done wrong, then adding more trees in the

following years.

It was really too early

to see any fruits last year, but profuse blooms

on our oldest peach made me hope for a harvest. Then a late

freeze wiped out every bloom, and I went back to pruning and training

and mulching with no reward.

My fruit tree

spreadsheet, though, says that this year may be

different. Peaches and dwarf cherries can fruit at three years,

and our two oldest trees are coated with bumpy flower buds. In

fact, even our two year old peach and nectarine are similarly laden,

though I refuse to get my hopes up about premature fruit this year.

I've been watching the

flower buds all winter with avid curiosity, and

Sunday the inevitable happened. A week of summer-like

temperatures tempted peaches to go from green bud to red bud stage (top

picture), while the cherry buds actually burst open (second picture),

revealing the individual flower buds within. Finally, I reached

the nectarine, planted in the sunniest spot against the side of the

barn. I saw a hint of brilliant pink in one bud and just kept

photographing my way around the tree until...

...a fully opened bloom!

I can't resist throwing

in a few more shots of the signs of spring that

have been bursting out in the garden this week. The dandelions

are now in full bloom, and the comfrey (top right) has leaves bigger

than my hand, ready to take back their job of mulching

the nectarine.

Elderberry leaves (bottom left) have been growing slowly for weeks ---

these seem to be the first spring tree leaves on the farm.

Finally, the columbine has really caught hold and looks to

have bloom buds on the way. Spring!

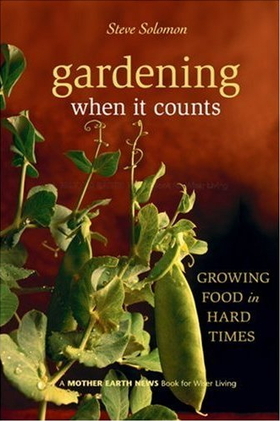

Instead

of playing the lottery, I play interlibrary loan. Each week, I

hit the library with a stack of request slips for books I've heard

about that aren't stocked by our tiny rural book-lender, and every week

something trickles down from northern Virginia to fill my voracious

book appetite. This is the saving grace of our tiny library ---

interlibrary loans are free.

Instead

of playing the lottery, I play interlibrary loan. Each week, I

hit the library with a stack of request slips for books I've heard

about that aren't stocked by our tiny rural book-lender, and every week

something trickles down from northern Virginia to fill my voracious

book appetite. This is the saving grace of our tiny library ---

interlibrary loans are free.

I try to put in requests

for an equal number of fiction and non-fiction books each week, but as

luck would have it, this week's haul was entirely fiction. I

gulped in dismay, and headed back into the library's one small room of

non-fiction on the off chance that their linear foot of gardening books

included a tome I'd not yet read. And there in front of my snooty

nose was a book every bit as good as the ones I'd requested from afar.

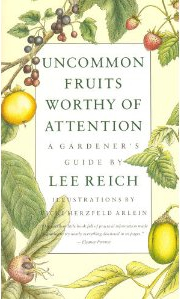

In fact, even though I'd

never heard of Lee Reich's Uncommon

Fruits Worthy of Attention,

all of my permaculture gurus clearly had. Information about

species like the hardy kiwi and the Nanking cherry had eluded me

because these plants were nearly impossible to find on the internet

(even though every permaculture book mentioned them.) I flipped

open Lee Reich's book and found that it was chock full of cultivation

and propagation information for these and seventeen other unusual

species. By the end of the week, at least four of these species

will be adequately represented on the internet --- stay tuned!

| This post is part of our Uncommon Fruits Worthy of Attention

lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I

noticed some shiny egg masses wrapped around the twigs of our biggest

peach tree this winter, but I left them in place since I didn't know

what they were. Sunday, tiny tent caterpillar webs began

radiating out from the egg masses. Bad news!

I

noticed some shiny egg masses wrapped around the twigs of our biggest

peach tree this winter, but I left them in place since I didn't know

what they were. Sunday, tiny tent caterpillar webs began

radiating out from the egg masses. Bad news!

If you live east of the

Rockies, you've probably seen the tent caterpillar before, even though

you may not have known what it is. The caterpillars live inside a

spiderweb-like tent of white silk that can reach about a foot in

length, easily visible around the limbs of wild black cherries as you

drive down the highway. Tent caterpillars are voracious eaters

and can defoliate entire trees in a season.

Although wild black

cherries are their favorite food, tent caterpillars enjoy pretty much

every fruit tree you'd plant in your yard. They like apples,

pears, cherries, plums, and peaches. Large orchards spray

chemicals to kill tent caterpillars, but on the backyard scale they're

extremely easy to pick off the branch either in the egg stage or soon

after the caterpillars hatch. And our hens want you to know that

a web full of tiny caterpillars is a very tasty treat.

If

you don't live in the Deep South, you probably thought the luscious

kiwi fruit was beyond your grasp --- I know I did. Enter the

Hardy Kiwi (Actinia

arguta),

whose vigorous vines will ripen fruits up to zone 4. The Hardy

Kiwi originated in China, where it grows naturally in humid mountain

forests that share so many species with our own Appalachian

mountains. Asian people have eaten kiwis for centuries, and

in

1983, 130,000 tons of kiwi fruit were harvested from wild vines of

several kiwi species in China alone.

If

you don't live in the Deep South, you probably thought the luscious

kiwi fruit was beyond your grasp --- I know I did. Enter the

Hardy Kiwi (Actinia

arguta),

whose vigorous vines will ripen fruits up to zone 4. The Hardy

Kiwi originated in China, where it grows naturally in humid mountain

forests that share so many species with our own Appalachian

mountains. Asian people have eaten kiwis for centuries, and

in

1983, 130,000 tons of kiwi fruit were harvested from wild vines of

several kiwi species in China alone.

Hardy Kiwi produces

fruits that taste very similar to the kiwi fruits that you buy in the

store (from Actinidia

deliciosa),

but they are much smaller and are hairless. My understanding is

that you pop Hardy Kiwis in your mouth like grapes, and can also store

them in root-cellar-like conditions (just above freezing and at 95%

humidity) for nine months. Since one plant can produce up to 100

pounds of fruit, you might be able to provide your winter dessert with

just a few vines.

The internet is full of

sites singing the praises of the Hardy Kiwi, but it is sorely lacking

in specific cultivation information. Luckily, Uncommon

Fruits Worthy of Attention walks you through the whole

process from propagating to planting to pruning and harvesting.

Here's a quick summary:

Where

should I plant my Hardy Kiwi?

Hardy Kiwis are sensitive to late spring frosts, so they are best

planted on north-facing slopes where they are shaded from early spring

sun. Provide well-drained soil (or plant

on mounds), and build a strong trellis to support the plants.

Kiwis should be at least 15 to 20 feet apart.

Do I need more than one plant? Since Hardy Kiwis have

separate male and female plants, you will need to provide at least one

of each to produce fruit. Only one male is necessary for each

eight female plants, as long as the female plants are within 35 feet of

the male.

How do I train and prune my Hardy Kiwi?

The initial training is a lot like training a young grape vine.

During the first year, develop a trunk by training the strongest shoot

up along a one to two inch thick pole, cutting away all other

shoots.

When the trunk reaches the lowest trellis wire, split it into two

cordons by training one arm along the trellis in each direction.

Once cordons are seven feet long, cut them back to that length each

winter and develop fruiting arms at one foot intervals along the

cordon. At the same time that you cut back the cordons, prune

fruiting arms to

eight buds beyond where they fruited last year.

How do I propagate the Hardy Kiwi?

If you want to perpetuate the same variety, take cuttings. Hardwood

cuttings

work, but softwood cuttings root even more easily when taken from new

growth in early summer, removing the tips and clipping leaves in

half. Softwood cuttings will root in two to four weeks.

Hardy Kiwis can also be propagated from seed (although you will end up

with more variable offspring, half of which will be male.) To

grow them from seed, put the whole fruits in a blender with some water

just long enough to create a mush, then sow the pulp and seeds

together, stratifying for two months. Hardy Kiwis bear at two

years from cuttings and at three to four years from seed.

When do I harvest the fruits?

Hardy Kiwi fruits are ready to be picked when the seeds are black, even

though the fruits are still hard. Allow them to soften for a week

at room temperature.

Why is the Hardy Kiwi a permaculture

favorite?

Permaculture admonishes us to grow plants that are well-suited to our

environment and don't require lots of sprays and babying. The

Hardy Kiwi fits a niche very similar to a grape, but

seems to have no diseases or pests (beyond Japanese Beetles) in the U.S.

Are you growing them? We

planted two females (Dunbarton Oaks and Ananasnya) and a male in fall

of 2008. They sulked for the first year, but I hope they'll take

off this year --- I'll keep you posted.

| This post is part of our Uncommon Fruits Worthy of Attention

lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I can already feel an

increase of happiness within the new flock after today's move. Now with a bigger

space and some real ground to scratch they should start to settle down and feel at home.

A couple of the more brave

chicks managed to jump out of the table

top brood box the last few days, which probably means they needed

more room a week ago.

We'll still keep a close eye

on their well being, but the care taking should be a lot easier now that

they have some elbow room.

Monday

morning, I opened the door to the building where we're keeping our

chicks and something skittered away to hide in the corner. Was it

a mouse drawn to the open bag of chick feed? Nope, it was a chick

who had hopped all the way out of the brood box and then flown or

fallen to the floor.

Monday

morning, I opened the door to the building where we're keeping our

chicks and something skittered away to hide in the corner. Was it

a mouse drawn to the open bag of chick feed? Nope, it was a chick

who had hopped all the way out of the brood box and then flown or

fallen to the floor.

Even though I put a lid

on the end of the brooder where our homemade chicken

waterer's mount

provided chicks with a handy stopping stool, our little cockerels were

clearly ready for a bigger home. I caught one perched on

the top of the box, then on Tuesday had to chase down two chicks who

had flown out and were busily exploring the seed starting area on the

floor.

As

a result, I was thrilled when Mark pushed through the heat on Tuesday

to finish up the chicken

coop and expand our

chicks' home by a factor of ten. It took the cockerels about a

minute to get their bearings, but then they started to peck and scratch

like mad. I'm not sure what, if anything, they were actually

finding to eat --- I suspect the chicks were just practicing their

foraging, testing out sticks and stones and leaves to see which ones

tasted like food.

As

a result, I was thrilled when Mark pushed through the heat on Tuesday

to finish up the chicken

coop and expand our

chicks' home by a factor of ten. It took the cockerels about a

minute to get their bearings, but then they started to peck and scratch

like mad. I'm not sure what, if anything, they were actually

finding to eat --- I suspect the chicks were just practicing their

foraging, testing out sticks and stones and leaves to see which ones

tasted like food.

Two weeks is very early

to move chicks outside, but the weather has been unseasonably warm and

I've given them a heat lamp to take the chill off the spring

nights. Next week, we'll let them out of the coop and into the

as-yet-unbuilt pasture, the true start to our forest

pasture experiment.

The Nanking Cherry showed up

on a list of edible hedge species, but I didn't know if the

plant was actually a cherry botanically and (more importantly) what it

tasted like. Uncommon

Fruits Worthy of Attention, as usual, cut right to the

chase.

Is the Nanking Cherry a cherry?

Nanking Cherry (Prunus tomentosa)

is in the same genus as cherries, plums, and peaches, but is a

different species than either sweet cherries (P. avium) or sour cherries (P. cerasus).

This means that your Nanking Cherries can't be pollinated by either of

these species, just as sweet cherries won't pollinate sour cherries and

vice versa.

Does the Nanking Cherry taste like a

cherry?

Flavor of the Nanking Cherry seems to be extremely variable, probably

due to the fact that American nurseries grow the plants from

seed. In stark contrast, the Nanking Cherry is the most common

garden fruit in the Russian Far East, where many named varieties

exist. Some varieties taste like tart cherries and others like

sweet cherries (though a quick search of the internet suggests that the

former flavor predominates among unnamed varieties in the U.S.)

How do I plant my Nanking Cherry?

Since Nanking Cherries are shrubs or small trees reaching between nine

and fifteen feet tall and wide, they should be planted about fifteen

feet apart. Alternatively, they can be planted four feet apart

and trimmed into a hedge. Be sure to plant more than one Nanking

Cherry for cross-pollination. Place them in an area with full sun

and well-drained soil.

How do I plant my Nanking Cherry?

Since Nanking Cherries are shrubs or small trees reaching between nine

and fifteen feet tall and wide, they should be planted about fifteen

feet apart. Alternatively, they can be planted four feet apart

and trimmed into a hedge. Be sure to plant more than one Nanking

Cherry for cross-pollination. Place them in an area with full sun

and well-drained soil.

Where can I grow the Nanking Cherry?

They can be planted in zones 3 to 6, which makes them a good choice in

more northern areas where traditional cherries can't be grown.

How do I propagate the Nanking Cherry?

If you don't mind the plants not breeding true, seeds are easiest (and

will grow a long, drought-resistant taproot, absent in plants grown

from cuttings.) Remove the seeds from the pulp, air dry slightly,

then stratify for three months. Seedlings bear by the third

year. Alternatively, take softwood cuttings when the fruit is

ripening, treat the base with rooting hormone, then keep the cuttings

under a mist. Or take 8 to 12 inch hardwood cuttings of one year

old wood, planting in well-drained soil in the fall or spring.

Why is the Nanking Cherry a

permaculture favorite?

Permaculture emphasizes making maximum use of your gardening

space. Since the Nanking Cherry is a shrub, it can fit into parts

of the garden where a standard cherry couldn't grow. Using the

Nanking Cherry as an edible hedge plant has forest

pasture implications as well.

Are you growing them? I'd like to find a named variety (or someone's backyard

shrub) that tastes like a sweet cherry, but in the meantime I bought a couple of seedlings to get us started. If you've tried them and have tasty plants, I'd love to

trade for some seeds or cuttings!

| This post is part of our Uncommon Fruits Worthy of Attention

lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Our cat Huckleberry has been

using 2 of our young fruit trees for a scratching post lately.

Let's see him try to scratch

them now.

A

film and radio crew came by the farm Wednesday to interview us for the

local radio station. They were doing a piece on how the internet

brings opportunity to an economically depressed area, and our Avian Aqua Miser business fit the bill.

Hopefully the segment will air and I'll be able to point you to the

station's website to listen and/or watch, but for now I thought you

might enjoy reading some highlights of our interview.

A

film and radio crew came by the farm Wednesday to interview us for the

local radio station. They were doing a piece on how the internet

brings opportunity to an economically depressed area, and our Avian Aqua Miser business fit the bill.

Hopefully the segment will air and I'll be able to point you to the

station's website to listen and/or watch, but for now I thought you

might enjoy reading some highlights of our interview.

We try not to make

guests walk through the floodplain (aka the alligator swamp) unless

they really want to, so Mark drove the golf cart to pick up the

crew. Four people, a big camera, and an even bigger microphone

crammed onto the cart --- I'm glad Mark added

on the truckbed in the back since it seated two. "Hold on

tight!" Mark warned, and they were off. And then, with a bump,

one was quite literally off --- the camera woman lost her hold and

ended up in the mud. Luckily, the camera came through fine.

Back at our homesite, we

showed off our chickens (though the journalists seemed even more struck

by Mark's deer deterrent.) Then we headed

inside our frantically-cleaned-up-this-morning trailer, which is still

barely presentable. Good thing Huckleberry was on hand to take

their attention away from the cobwebs --- he seemed bound and

determined to answer their questions, and kept meowing as we

talked. (Strider doesn't take well to unusual events like cleaning so he was absent.)

Thanks for coming by Rich, Mimi, and Sylvia! I hope the dunking

in the mud doesn't scare you off for good.

I'm

familiar with currants and gooseberries by name alone since my New

England relatives grew the bushes in their gardens. I'd barely

tasted the fruits and wasn't all that excited until I read

that currants were a favorite of Robert

Hart's since they will produce

fruit even in the shade. As usual, Uncommon

Fruits Worthy of Attention had answers to all of my top

questions.

I'm

familiar with currants and gooseberries by name alone since my New

England relatives grew the bushes in their gardens. I'd barely

tasted the fruits and wasn't all that excited until I read

that currants were a favorite of Robert

Hart's since they will produce

fruit even in the shade. As usual, Uncommon

Fruits Worthy of Attention had answers to all of my top

questions.

What's

the difference between a currant and a gooseberry? Gooseberries and

black, white, and red currants are all in the Ribes genus. Gooseberries

are a hybrid of R.

uva-crispa and R.

hirtellum,

and they counteract their big thorns with large, sweet berries.

Currants are thornless, but have smaller fruits that are quite tart and

are less often eaten uncooked. They come in two categories ---

black currants are a mixture of R. nigrum, R.

odoratum, and R.

americanum and

red and white currants are both a mixture of R. rubrum, R. sativum, and R.

petraeum.

Both kinds of currants are unrelated to the raisin-like "currants",

which are actually a dried grape like any other raisin.

Where

can I grow currants and gooseberries?

Currants and gooseberries are great for northern climates (some are

even hardy in zone 2), and some can be grown further south. In

all cases, if you're planting them toward the southern end of their

range (below zone 5), you should give them some shade, perhaps plant

them on the north side of a hill, and mulch them heavily to keep

moisture around their roots. Gooseberries are often listed as

growing all the way to zone 8, while currants are often listed only

down to zone 5 or 6.

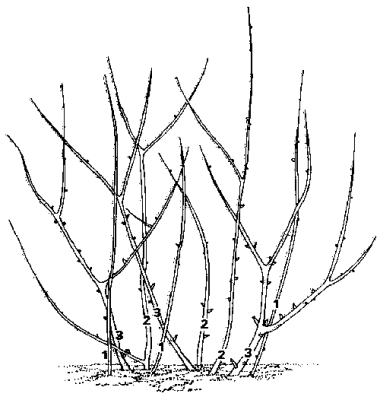

How do I grow and prune them?

Plant currant and gooseberry bushes four to six feet apart in heavy

soil

with plenty of organic matter. Each year, thin out the new shoots

so that only two or three stems for red currants or six stems for

gooseberries remain from that year, leaving older stems in place.

After three years for currants or four years for gooseberries, begin to

remove the oldest set of stems as well during the winter pruning.

The result is a mixture of stems of different ages ranging from one to

three years for currants and from one to four years for

gooseberries. Pruning for black currants is a bit different since

these bushes bear primarily on one year old wood --- cut out two to

five of the oldest branches each year and shorten other branches.

How do I grow and prune them?

Plant currant and gooseberry bushes four to six feet apart in heavy

soil

with plenty of organic matter. Each year, thin out the new shoots

so that only two or three stems for red currants or six stems for

gooseberries remain from that year, leaving older stems in place.

After three years for currants or four years for gooseberries, begin to

remove the oldest set of stems as well during the winter pruning.

The result is a mixture of stems of different ages ranging from one to

three years for currants and from one to four years for

gooseberries. Pruning for black currants is a bit different since

these bushes bear primarily on one year old wood --- cut out two to

five of the oldest branches each year and shorten other branches.

How

do I propagate gooseberries and currants?

All can be grown from seed as long as you don't mind them not breeding

true; the seeds require three to four months of stratification, and

will bear at two to three years. To maintain your varieties, use

one of the several methods of cloning instead. Twelve inch long

hardwood

cuttings (excluding the tip) should be taken in the early fall before

all the leaves have dropped for gooseberries, or in early spring,

autumn, or the end of summer for currants. An even easier way to

propagate gooseberries or black currants is tip layering --- bending

down a branch and covering it with soil and a rock, then cutting the

new plant free once roots have formed.

What

about the white pine blister rust?

The reason that gooseberries and currants are seldom grown in the

United States is that they were illegal for decades. In the early

twentieth century, the white pine blister rust showed up in America and

began wiping out what was then an important timber tree. Since

some Ribes

species were an alternate host for the rust, planting gooseberries or

currants was prohibited by federal law, and Civilian Conservation Corps

crews began to rip the plants out of gardens and woodlands.

Later, scientists discovered that most cultivated Ribes

are resistant to white pine blister rust and don't spread the disease,

and the federal ban was finally lifted in 1966. However, you may

still face state restrictions against planting gooseberries and

currants, especially against black currants which are most susceptible

to the white pine blister rust.

Why

are gooseberries and currants permaculture favorites?

Permaculture advocates filling every available niche with a useful

plant so that weeds don't have a spot to gain a foothold. Since

gooseberries and currants can fruit in partial shade, they can be used

to turn orchards from trees-amid-lawn to a multi-storied forest

garden.

Are

you growing them?

We ordered two

gooseberries (Poorman and Invicta) that will be arriving this

month. We chose gooseberries over currants since I am first and

foremost a fresh fruit fanatic.

| This post is part of our Uncommon Fruits Worthy of Attention

lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The heat lamp we had in the new

brood coop somehow got damp during this afternoon's rain storm

which resulted in a small explosion.

Luckily there were no

casualties. I guess I should hurry up and build that heat pad chick

warmer that Anna dreamed up a few weeks ago.

We had to switch to the

smaller back up bulb due to the larger heat

lamp exploding yesterday.

I used a piece of scrap

Reflectix and an old wooden box to form a cozy insulated corner that

can hold in enough heat to keep the chicks comfortable.

Stay tuned for more details

on the up and coming heat pad chick warmer, which might not make it off

the drawing board till the next generation of chicks.

A

month after planting seeds in my cold frame,

the broccoli is big and

vibrant. Many of the seedlings are working on their third true

leaves, which means they're ready to be transplanted into the main

garden. With rainy weather predicted for the afternoon and a

general cool-down from our recent abnormal heat, Thursday seemed like

the perfect day to set them out.

A

month after planting seeds in my cold frame,

the broccoli is big and

vibrant. Many of the seedlings are working on their third true

leaves, which means they're ready to be transplanted into the main

garden. With rainy weather predicted for the afternoon and a

general cool-down from our recent abnormal heat, Thursday seemed like

the perfect day to set them out.

I was a bit leery of transplanting the broccoli, though, because the

weather

forecast says our temperature will drop to 34 Fahrenheit on Friday

night. I

know that barely sounds chilly, but our lows are generally about 5

degrees beneath what the nearest weather station reports.

Would 29 F be too cold for our tender broccoli seedlings?

I was a bit leery of transplanting the broccoli, though, because the

weather

forecast says our temperature will drop to 34 Fahrenheit on Friday

night. I

know that barely sounds chilly, but our lows are generally about 5

degrees beneath what the nearest weather station reports.

Would 29 F be too cold for our tender broccoli seedlings?

A search of the

internet suggests that broccoli won't get harmed unless

the temperature drops to 25, but I still wasn't entirely

confident. Luckily, I always start too many broccoli seeds

because I like having seedlings to give away. So I set out the

biggest broccoli plants and put the row cover fabric back on the cold

frame

to protect the seedlings left behind. If my transplanted

seedlings get nipped, I'll just re-transplant next week. If they

don't get nipped, I'll get an extra week of growth --- a conundrum has

been transformed into a win-win situation.

Every

year when we were kids, my siblings and I picked mulberries out of a

large tree in a nearby park. We liked the fruit, but not as well

as the blackberries and raspberries that ripened at the same time, and

our one attempt at a mulberry pie was pretty awful. So I put

mulberries out of my mind...until I started reading that mulberries

can provide all of the food you need for a pig or flock of chickens for

several months in the summer. Then, of course, my

ears perked up.

Every

year when we were kids, my siblings and I picked mulberries out of a

large tree in a nearby park. We liked the fruit, but not as well

as the blackberries and raspberries that ripened at the same time, and

our one attempt at a mulberry pie was pretty awful. So I put

mulberries out of my mind...until I started reading that mulberries

can provide all of the food you need for a pig or flock of chickens for

several months in the summer. Then, of course, my

ears perked up.

What

are the different kinds of mulberries? There are three

species of mulberries that can be found growing in the United

States. The White Mulberry (Morus alba)

is native to Asia, but was widely introduced in the nineteenth century

as fodder for a silk industry that never panned out. White

Mulberries are cold hardy, but have rather insipid fruits. Red

Mulberries (M. rubra) are a U.S. native with

tastier fruits than White Mulberries. Finally, Black Mulberries (M. nigra)

are members of another Asian species, this one selected primarily for

the highly tasty fruits. Unfortunately, Black Mulberries can't be

grown in many parts of the U.S. (like the southeast), but hybrids

between Red and White Mulberries (like the Illinois Everbearing

Mulberry) produce the best of both worlds --- tasty fruits on hardy

trees.

How

do you grow and prune mulberries?

Mulberries are one of those trees you mostly leave alone. Plant

them in full sun with fifteen feet of space on every side, then prune

out dead branches if you feel like it.

How

do you propagate mulberries?

Mulberries are difficult to grow from seeds since you must wait at

least a decade to know whether you've developed a good variety, and

since trees can change sex when young. More tried and true

propagation techniques include hardwood, softwood, or root cuttings and

grafting. When taking hardwood cuttings, split the lower ends of

the cutting or include a small heel of two year old wood to promote

rooting. Take softwood cuttings in midsummer and treat with a

rooting hormone.

How

do you harvest mulberries?

Be prepared for your tree to grow for a decade or more before it feels

like fruiting, especially if grown from seed. Once mulberries

begin to fruit, though, they're highly dependable since they bloom late

and are rarely affected by late spring frosts. Depending on which

variety you have, your tree will ripen its fruits over a month to three

months during the early to late summer. To harvest the fruits,

spread a sheet under the tree, shake the branches, then pour the

results into a bucket of water. The fruits will sink and

everything else will float off.

Why

are mulberries a permaculture favorite?

Mulberries are one of the least picky fruit trees out there. They

don't mind drought, pollution, or poor soil, and often grow as weeds

even in harsh city environments. Even the varieties that aren't

quite up to par as people food produce wholesome berries that can feed

your pigs or chickens for up to three months during the summer.

The leaves are high in protein too.

Are

you growing them?

I'd planned to buy an everbearing variety to put into our new forest

pastures this year

or next, but this post pushed me over the edge and I put in an order

for an Illinois Everbearing Mulberry in March.

| This post is part of our Uncommon Fruits Worthy of Attention

lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

One of my mother's

favorite expressions is "all ye of little faith" --- it's in reference

to me, mostly. Every year, I plant an early bed

of peas around Valentine's day.

And every year, I give up on the bed less than a month later and

replant

it. As a result, I'm never quite sure whether the Valentine's

peas came up, or whether what I'm seeing is the later peas. This

year, I got smart (though no more faithful) and marked my early row of

peas, planting the replacement row a couple inches to the side.

So I could tell that both rows of peas came up, and

that the Valentine's row came up a week earlier than the March row.

Now what do I do with

two rows of peas where one is supposed to be? Just as I was

pondering this problem, I dropped by Eliza's awesome blog and learned

that young

pea shoots taste similar to snow peas.

Just what I needed to round out the first completely-from-the-farm

salad of the year! Lettuce, pea shoots, baby kale (wintered

over), and the last of the fall carrots melded into a delectable side

dish. Last year we

lived on salads for the entire month of March, but I say better late than

never!

We've had this portable wall

of willow branches since the winter(Thanks Mom), and today was the day I found its

first use.

I put it up by the door to

give the chicks some room to scurry off to while I installed the new

Reflectix

chick warmer.

Soon we'll have a proper area

for the boys to run and scratch during the day.

Did

you know that you can inoculate

stumps with edible mushrooms soon after you cut the trees down?

Since the roots are buried in the moist soil, the stump will stay damp

enough for the mycelium to run through the wood, then mushrooms will

pop out of the cracks. After a few years of creating mushrooms,

the stump will have broken down into good compost, and the mushrooms

might

even spread into the soil of your garden and help your vegetables grow.

Did

you know that you can inoculate

stumps with edible mushrooms soon after you cut the trees down?

Since the roots are buried in the moist soil, the stump will stay damp

enough for the mycelium to run through the wood, then mushrooms will

pop out of the cracks. After a few years of creating mushrooms,

the stump will have broken down into good compost, and the mushrooms

might

even spread into the soil of your garden and help your vegetables grow.

Sadly, I didn't know

this five years ago when we cleared our garden area, so the mushrooms

coming out of our stumps are of dubious edibility (though they are

quite beautiful.) I wish I'd been reading my blog when I started

working on the farm! (Although a time loop like that might do

more harm than would be merited by a few extra mushrooms.)

Our new Craftsman lawnmower is a lot easier to work on than

its older cousins.

It only took a bit over an

hour to take it apart, clean the points, and put it all back

together with no parts left over.

It's still a little rough to

start, which I suspect is due to a slight warp in the blade. These

blades have a more complex twist to them so they can work as a mulcher

and throw the grass cuttings back towards the bag. It's this complexity

that seems to make it more sensitive than most mowers and I would have

to say gives it a disadvantage for folks like us who have the

occasional stump to work around.

Of course this problem should

work itself through as we continue to delete the stumps and level out

the mowing area.

Ramps

are a prime candidate for forest

gardening.

They are an early

spring ephemeral that will keep nutrients cycling through the soil

before trees leaf out, they prefer growing in shady spots under

deciduous trees, and they are considered a delicacy by many. Once

a patch gets going, it can outcompete other herbs and turn into a solid

groundcover, as this photo from the wild shows.

Ramps

are a prime candidate for forest

gardening.

They are an early

spring ephemeral that will keep nutrients cycling through the soil

before trees leaf out, they prefer growing in shady spots under

deciduous trees, and they are considered a delicacy by many. Once

a patch gets going, it can outcompete other herbs and turn into a solid

groundcover, as this photo from the wild shows.

There are two species of

ramps in our area --- the stereotypical Allium

tricoccum and the

slightly smaller Allium

burdickii,

sometimes known as Burdick's wild leek. I know spots where both

of these grow, but the latter is found at a lower elevation in

conditions more like those in my garden, so I thought I'd give it a

shot first.

I'd prefer to plant

ramps from seeds, but the fruits are difficult to find in the wild, so

I dug a few seedlings from the edges of a wild clump. When

digging wild plants, I never take more than 10% of a population

(preferably much less), and try to remove plants that are already

threatened in some way. The plants I dug were in the middle of a

trail and were already damaged by hiking boots, so I figure they'll

have a better chance in my garden than if left in place in the woods.

My Burdick's wild leeks

have found a new home nestled amid the leaf mold under my oldest peach

tree. If this experiment works, I may try for some Allium

trioccum in a few

weeks when the higher elevation plants are out. I hope to expand

the clump by seed once the ramps become established, and to begin to

harvest leaves in a few

years.

For more information about ramp cultivation, check out this extension

service factsheet.

To see the masses of wildflowers I stumbled across during my ramp hunt,

visit my Appalachian ecology site.

Outside

the kitchen window, our peach tree is buzzing with pollinators. I

can see hundreds of insects at a time, but they fly too quickly to

really count. Despite having three honeybee hives, our

domesticated pollinators make up a scant 1% of the peach tree

pollinator haze, and other gaudy pollinators like butterflies and

bumblebees are also in the

minority.

Outside

the kitchen window, our peach tree is buzzing with pollinators. I

can see hundreds of insects at a time, but they fly too quickly to

really count. Despite having three honeybee hives, our

domesticated pollinators make up a scant 1% of the peach tree

pollinator haze, and other gaudy pollinators like butterflies and

bumblebees are also in the

minority.

I spent a few minutes

last week snapping shot after shot of the vibrant

insect population on the peach tree, then went inside to try to figure

out who all of these wild pollinators were. That's when I

stumbled across Bug Guide,

a website run by amateur entomologists who want to share their love of

insects with you. You can browse through their online guide,

which is chock  full of photos and

fascinating information. Then,

when you get stumped, you can submit photos of your mystery insects and

their experts will give you an ID, often within an hour or two.

full of photos and

fascinating information. Then,

when you get stumped, you can submit photos of your mystery insects and

their experts will give you an ID, often within an hour or two.

This week's lunchtime

series showcases four common pollinators that

you've probably never heard of. I hadn't heard of most of them

either, and had to ask the experts at Bug Guide for a bit of

identification help. I make no promises that these are the most

common

pollinators out there --- in fact, the take home message I got from my

time spent peering at peach blossoms is that there are dozens of

species of native pollinators and no single insect is the silver bullet

to make sure your plants produce fruit. Rather than focusing

on saving the honeybee, we'd be much better served to encourage a

diversity of wild pollinator species by keeping our farms and gardens

on the wild side.

This post is part of our Native Pollinators lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: This post is part of our Native Pollinators lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Big

thanks to Vester for pointing me in the flywheel key direction in the

comments section of yesterday's post.

Big

thanks to Vester for pointing me in the flywheel key direction in the

comments section of yesterday's post.

I had to replace the

blade twice last summer, and it stands to reason that the flywheel

key is now the problem with the uneven timing and toughness to start.

Here's a good 5 minute video

on exactly how to replace this part, but in the comments section of

the video someone pointed out how the guy used a hammer and a large

screw driver to get the flywheel off, which can result in damage to the

flywheel if you're not careful.

The fear of fly wheel damage prompted me to order a special

flywheel puller tool which is pictured above. This type works on most

of the Briggs and Stratton flywheels, but you'll need to check your

engine number to see if it's a proper match.

The lesson for today is to

check out the comments. You might just learn something new about the

wonderful world of small engine repair.

I transplanted

two beds of broccoli

last Thursday then three more a day later. As expected, it

frosted both Friday and Saturday night --- I can't tell you how cold it

got since our exterior thermometer is still inside the collapsed

refrigerator root cellar, but I'd say it got into the

high 20s. All of my broccoli seedlings got nipped, but the ones

transplanted on Thursday were only midly damaged while those

transplanted on Friday ended up on death's door. See for yourself

--- here is a typical Thursday seedling:

And here's a typical

Friday seedling:

I suspect that the

Friday seedlings were still dealing with the worst of their transplant

shock when the frost hit, while the Thursday seedlings were in prime

condition. If I had it to do over again, I would have

transplanted earlier in the week to give the seedlings more time to get

situated. I wonder if the seedlings wouldn't have been damaged at

all if they'd had a few more days to get their roots under them?

Good thing I've got

spares! I replaced all of the badly nipped seedlings and put out

a couple more beds' worth Monday evening. No frost is forecast

for the next week, so they should do fine.

Halictid

bees, also known as sweat bees, make up a large family of insects with

over 2,000 species. Although some are

drab colored, the common species that visited our peach (Augochlora

pura) was a

brilliant, metallic green, which is typical of many other types of

halictids as well.

Halictid

bees, also known as sweat bees, make up a large family of insects with

over 2,000 species. Although some are

drab colored, the common species that visited our peach (Augochlora

pura) was a

brilliant, metallic green, which is typical of many other types of

halictids as well.

Halictids get their

common name from their tendency to lick salt off

our sweaty skin, making them one of the better known classes of insects

despite their small size. They're also easily startled, and I get

stung by sweat bees more than by any other insect, but the pain

fades

quickly and is a small price to pay for their pollination expertise.

Like bumblebees,

halictids are buzz

pollinators,

which means they're better than honeybees at pollinating blueberries

and tomatoes. They are also generalist pollinators who are glad

to visit any flower full of pollen and

nectar. The combination adds up to a very useful pollinator

species that should definitely be encouraged in your garden.

The best way to build a

healthy population of wild pollinators is

to understand their nesting and foraging requirements and then provide

them with good habitat. Sweat bees nest in bare patches of soil

or in wood, packing brood cells full of pollen and nectar then laying

an egg on top. When the egg hatches out, the larval sweat bee

feeds itself with no help from its parents, then makes its way out of

the nest to live as an adult. Give them a patch of bare ground

and a steady flow of flowers throughout the year and sweat bees will be

industrious pollinators in your garden.

| This post is part of our Native Pollinators lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I installed a small roost

training limb in the chicken

pasture coop today.

Folks around here speak of a

mysterious benefit from using cedar in chicken coops.

Someday I'll try to figure

out the logic behind that Appalachianism. In the meantime I'll keep

using cedar in future chicken

tractors and coops just because it looks so good and feels very natural.

Except for last

weekend's Dogwood Winter, we seem to have skipped right

over spring and moved on to summer. The pollinator

haze on the

peach is starting to die down as the flowers pass their prime and

leaves pop out. Our other fruit trees --- like this pear --- are

following suit.

The blueberry bushes are

coated in flower buds, and I keep having to

remind myself not to count my berries until the frost free date.

I considered rabbiteye

blueberries an

experiment here in zone 6, but

they seem to be happy and healthy. We only lost one --- the

large, older plant my friends threw into the order so that Mark and I

would get to sample blueberries the first year. The loss is a

handy reminder that older woody plants tend to transplant badly and

often do

worse than a youngster of the same species.

Despite all of the

promise, the beginning of summer brings trials and tribulations.

This year's abnormally hot,

dry spring led to low germination rates in my spinach and swiss chard,

and I can't seem to find a single onion seedling. I know that I

should just plant some onion sets, but sets don't produce good storage

onions (and cost so much that it's barely worth your while to grow

them.) Instead, I'm going to be nutty and replant the onion seeds

in a shady corner, hoping for a miracle.

Our asparagus also

breaks my heart. Last year's asparagus

beetle

infestation killed back the fronds by early summer, and the spears now

poking up out of the ground are far thinner than they should be as

three year old plants. The calendar says that we should be able

to eat asparagus this year,

but I suspect the right thing to do is give the plants another year to

recover...assuming I can keep the asparagus beetles at bay. I've

already squashed a few and had better come up with a solution fast!

But the rest of the

garden is growing like gangbusters. I meant to go back and add

some mulch under the nectarine, but the comfrey has done that for me.

Of course, the real clue

that it's summer came when I turned on the sprinklers. I should have done

that two weeks ago --- it might have saved my seed onions!

Over half of the

pollinators visiting our peach tree were miniscule and

flighty, hard to catch a glimpse of let alone capture on film. I

did manage to snag a photo of this Small Carpenter Bee (Ceratina sp.),

which might be better named Teeny-tiny Carpenter Bee. Small

Carpenter Bees are sometimes confused with sweat bees, but the carpenter bees

have a club-shaped abdomen, a dull metallic color (versus the brilliant

color of some sweat bees), inconspicuous hair, and a pale yellow patch

on the face.

Small Carpenter Bees (Ceratina sp.)

are related to the larger carpenter bees that drill holes in your porch

and weaken the integrity of the wood, but their life cycle is a bit

different. Ceratina bees are much more likely to

be found in wild areas,

where they nest in the pith of broken plant stems. We have all

five of their favorite nesting species on our farm --- elderberry, box

elder, sumac, blackberry, and sunflower --- and I have a sneaking

suspicion the bees might also use the large, woody stems of wingstem

which are so prevalent in our floodplain.

Small Carpenter Bees

make good pollinators because they can be quite

numerous and aren't picky about the flowers they visit. To

encourage them in your yard, leave some brushy, wild areas around for

the bees to nest in, or plant sunflowers and leave the stems standing

all winter. You may be rewarded with a horde of tiny bees

visiting your flowers in the spring.

| This post is part of our Native Pollinators lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The new goat gloves

are breaking in better than the competition.

I suspect the smooth molding process is thanks to the elastic like

black fabric between each finger.

The

four tons of compost Mark bought me a few weeks

ago was actually more than

I needed.

I can't quite understand the concept, but I added a five gallon bucket

to each of my garden beds and had a lot leftover, enough to make some

extra raised beds using the lasagna method. I put down layers of

cardboard and paper as a weed retardant, then piled up masses of

compost, leaves, and mostly composted wood chips. The wood chips

are full of happy soil critters, and I'm hoping they'll inoculate the

whole pile before I need to plant the beds in a month.

The

four tons of compost Mark bought me a few weeks

ago was actually more than

I needed.

I can't quite understand the concept, but I added a five gallon bucket

to each of my garden beds and had a lot leftover, enough to make some

extra raised beds using the lasagna method. I put down layers of

cardboard and paper as a weed retardant, then piled up masses of

compost, leaves, and mostly composted wood chips. The wood chips

are full of happy soil critters, and I'm hoping they'll inoculate the

whole pile before I need to plant the beds in a month.

I was so pleased with

myself...until I went out to look at my new beds

after last week's rain. Did you know that if you buy compost that

has been allowed to dry out all the way,  the

compost becomes hydrophobic and is

very difficult to rewet? Despite nearly an inch of rain, our

lasagna beds were bone dry. Yikes!

the

compost becomes hydrophobic and is

very difficult to rewet? Despite nearly an inch of rain, our

lasagna beds were bone dry. Yikes!

So we hooked up the

sprinklers and started soaking the new raised

beds. I watered half the beds for an hour, then let the liquid

percolate down through the compost while I soaked the other beds for an

hour. Alternating this way for about fifteen hours finally wet the majority of the compost and I'm hoping the dry spots will equalize out over time.

As

with any farm trauma, there's always a silver lining. The

tiger swallowtails are quite happy with the damp compost and have

gathered

by the dozen on newly wet raised beds. Nothing like hordes of

fluttering butterflies to brighten your day!

As

with any farm trauma, there's always a silver lining. The

tiger swallowtails are quite happy with the damp compost and have

gathered

by the dozen on newly wet raised beds. Nothing like hordes of

fluttering butterflies to brighten your day!

Miner

bees (also called mining or digger bees, in the genus Andrena) seem to be custom made for

fruit tree pollination. The adults are present only during March

and April, right when your trees are blooming, and the bees are seldom

distracted by ground-flowering weeds. (Our honeybees, in

contrast, seem to be spending most of their time on dead nettles at the

moment.) Miner bees are also able to fly at chillier temperatures

than many of the other pollinators I've discussed this week, so they're

active during the morning and evening and on drippy days.

Miner

bees (also called mining or digger bees, in the genus Andrena) seem to be custom made for

fruit tree pollination. The adults are present only during March

and April, right when your trees are blooming, and the bees are seldom

distracted by ground-flowering weeds. (Our honeybees, in

contrast, seem to be spending most of their time on dead nettles at the

moment.) Miner bees are also able to fly at chillier temperatures

than many of the other pollinators I've discussed this week, so they're

active during the morning and evening and on drippy days.

I

found at least two species of miner bees on

our peach tree, which is to be expected since 1,300 Andrena

species exist worldwide. The

bees are similar in size to a honeybee --- one of my species is a bit

smaller and one a bit larger --- but sparser hair on the bee's body

gives the miner bee

a mean look. Luckily, they're not mean at all, and are even less

likely than a honeybee to sting. You can distinguish miner bees

by their dark-tinted wings and extra-hairy back legs. These

pollen brushes seem to go, as one website put

it, "seemingly in their 'armpits'".

I

found at least two species of miner bees on

our peach tree, which is to be expected since 1,300 Andrena

species exist worldwide. The

bees are similar in size to a honeybee --- one of my species is a bit

smaller and one a bit larger --- but sparser hair on the bee's body

gives the miner bee

a mean look. Luckily, they're not mean at all, and are even less

likely than a honeybee to sting. You can distinguish miner bees

by their dark-tinted wings and extra-hairy back legs. These

pollen brushes seem to go, as one website put

it, "seemingly in their 'armpits'".

Despite being

custom-made for fruit-tree pollination, miner bees aren't

all that common in large-scale orchards. The bees won't fly very

far to forage, so they require a wild nesting site close to the trees

they feed from. To encourage Andrena

in your garden, provide them with some loose soil near or under shrubs,

preferably on a warm, south-facing bank. Your miner bees will dig

a burrow in the soil and lay eggs in brood cells full of pollen and

nectar, just like sweat bees

do. The adults will die in late spring soon after laying their

eggs, and won't be seen again until your peach trees are once again in

bloom.

| This post is part of our Native Pollinators lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

It

finally happened.

It

finally happened.

We finally hauled enough compost

to satisfy the heavy organic needs of this year's compost quota.

The new goal is to always

have a healthy size pile on hand for emergency fertilizing.

Next to that will be an even bigger pile of mulch.

Thus begins Toby Hemenway's thought-provoking

article "Is Sustainable

Agriculture an Oxymoron?" Those of you who were

intrigued (or irritated) by my post that people

worked only 3 hours per day before the Industrial Revolution should take a look at

Hemenway's article.

Thus begins Toby Hemenway's thought-provoking

article "Is Sustainable

Agriculture an Oxymoron?" Those of you who were

intrigued (or irritated) by my post that people

worked only 3 hours per day before the Industrial Revolution should take a look at

Hemenway's article.Anthropologist Yehudi Cohen broke societies down into five categories, the relevant three being foragers (hunter-gatherers), horticulturalists (gardeners), and agriculturalists (farmers.) Based on historical and anthropological data, Hemenway comes to the conclusion that agricultural societies are inherently unsustainable, but he doesn't make the leap several of you made upon reading my previous post that the only solution is to return to a hunter-gatherer existence. Instead, we can meet in the middle as horticulturalists:

Mark and I have been going back and forth for years about whether we are farmers or gardeners. On the one hand, we are serious enough about our endeavor that we consider ourselves farmers. On the other hand, we don't use tractors or sell our excess --- two signs that we're merely gardeners. Maybe I should start calling us horticulturalists?

Thanks to Vester for passing on this intriguing article! I'd love to hear from anyone with an anthropology background who could suggest a bit of reading material for me to bone up on traditional horticultural societies.

"I've

started seeing a different kind of bee lately," Mark said as April

rolled in. "It's a bit smaller than a honeybee

and...simpler."

"I've

started seeing a different kind of bee lately," Mark said as April

rolled in. "It's a bit smaller than a honeybee

and...simpler."

I knew exactly what he

was talking about since I'd noticed the same

insect hovering in mid-air as I worked around the yard. It looked

like a child's drawing of a bee --- just one big hunk of fluff with

wings. But it wasn't a bee.

The Greater Bee Fly (Bombylius

major)

is a fly that mimics a bee both in appearance and in behavior.

Once our peach flowers opened up, about a tenth of the pollinators

drawn to the abundance of nectar and pollen were bee flies. The

flies are easy to distinguish from true bees since they have a habit of

hovering, hummingbird-like, in front of flowers, or landing and showing

off their extra long legs.

Like many garden

insects, bee flies aren't really good or bad.

They're a great pollinator, but the flies also parasitize solitary bees

and wasps, thus cutting down on the population of other pollinators and

predators. Unlike other bee mimics that try to piggy-back on

predators' aversion to stinging insects, bee flies probably mimic bees

so that they can get close to the bees' burrows and fling their eggs

inside. When the bee fly eggs hatch out, the larval flies feed on

the larval bees, killing the bees in the process. Despite the

death toll, I consider the presence of bee flies a good sign since it

signals

a healthy and varied insect population. It's best not to put all

of your pollinator eggs in one basket.

| This post is part of our Native Pollinators lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The home

made golf cart dump box is holding up nicely under some serious

hauling.

I think adding a couple of

seat backs to the protruding frame might help to soften the bumps for a couple of

passengers in the back.

Homesteading teaches

flexibility. I was absolutely certain that I would have time to

finish weeding the beds of garlic and spring seedlings this week and

that Mark would have time to fence in our first chicken pasture. In reality, we each

got about halfway to our goal. It just seemed more important to

visit Mark's mom and my dad, to get the irrigation

system back up and running, and to cut the weeds before they were

too high for the mower.

I felt a bit bad about

leaving the chicks in their coop over another weekend, so I tossed in a

bag of weedy grass clippings. The shady side of the yard came up

in a dense stand of chickweed and bittercress this winter, and I didn't

get the mower over there before these weeds went to seed. I

figured it was a better idea to let the chicks pick through the weedy

clippings than to put them straight on a garden bed, and the chicks

agreed. "These are tasty!" they exclaimed, then proceeded to play

king of the hill.

I raised the automatic chick

waterer height yet again due to the rapid growth rate of the new

flock.

If everything goes as planned

they should be running free in their new pasture sometime around

the middle of next week.

My winter

leaf mulches were a

wonderful success. They kept the weeds down admirably, and seem

to have improved the soil quality in the process. While transplanting

broccoli last week, I was stunned by the moist, crumby structure of

the soil in the loamy upper garden, and by the ubiquity of worms and

other good soil critters.

Unfortunately, I can't

just keep the leaves in place for the summer. Some of the mulch

has blown away or rotted into the ground, while the big leaves left

behind are prone to move onto small seedlings and drown them out.

I raked a few dozen beds bare in March to plant peas and greens, and

now weeds are already starting to crowd my vegetables. Time to

experiment with some summer mulches:

Grass

clippings. Last year, I learned that grass/clover

clippings make a great summer

mulch since they are high in nitrogen and feed the soil while drowning

out weeds. We did make a mistake and mulched two beds with

clippings

that had already gone to seed, with predictable results, but all of the

other beds mulched with grass clippings are happy and healthy.

The