archives for 08/2009

I've been refraining from saying this because

I don't want the water gods to think I'm ungrateful.

But...please...can we have just a

little break from the rain?

I've been refraining from saying this because

I don't want the water gods to think I'm ungrateful.

But...please...can we have just a

little break from the rain?

The fall crops have all sprouted with no problem. In fact, the

broccoli looks so lush I wonder if the plants are going to head up

prematurely. We haven't had to water in over a week.

But the tomatoes. My poor, darling tomatoes. They are so

plump and juicy and totally green

on the vines. Whenever I talk to my garden friends, our

conversation revolves around the lack of ripe tomatoes. For

goodness sake, the ironweed is starting to bloom and I'm still eating

last year's pizza sauce!

My work pants have developed mildew and the roof has sprouted a

leak. There's so much humidity in the air that it cost

significantly more to mail out our chicken waterers this

week. I really could use a few sunny days to dry my laundry and

ripen the tomatoes. Please?

A few weeks ago, our Barred Rocks stopped

laying in their nest box. Something must have clicked in the lead

hen's head, because she suddenly decided it made a lot more sense to

lay her eggs hidden back under the weather flap of the chicken

tractor.

A few weeks ago, our Barred Rocks stopped

laying in their nest box. Something must have clicked in the lead

hen's head, because she suddenly decided it made a lot more sense to

lay her eggs hidden back under the weather flap of the chicken

tractor.

A quarter of the time, I'd catch the first hen to lay and move her egg

to the box, then the other hens would lay in the right place.

Another half of the time, we found the eggs before dragging the tractor

across them. The rest of the time, the eggs got smashed and Lucy

got a treat.

Last week, I tossed a golf ball in the nest, hoping it would act as a

nest egg and prompt the hens to lay in the right place. Sure

enough, the ball did the trick! The few times I manage to

outsmart them, I'm awfully glad that chickens are none too bright.

Emily

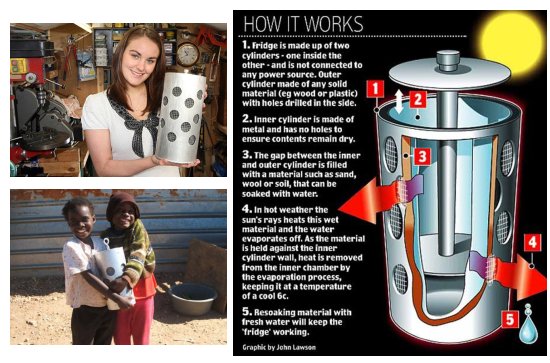

Cummins is a 21 year old student/inventor who has come up with a

clever and simple way of using the sun to cool things like perishable

food and temperature sensitive medications. The concept works with no

electricity and can be built with materials like cardboard, sand, and

recycled metal.

It takes advantage of conduction and convection to create an

evaporative cooling effect. You place what you want to keep cold in the

interior chamber and either some sand, wool, or soil in the outer

chamber that gets saturated with water. The sun warms the water soaked

material...the water evaporates, reducing the temperature of the inner

area to 43 degrees Fahrenheit for days at a time. To recharge you only

need to add more water once your material gets dry.

I've decided to give up on my pleas for a

break from the rain. We did get 24 hours of partial sun on

Saturday which mostly dried three loads of laundry and brought the

first blush of red to a few tomatoes. And then Sunday brought

another deluge, filling all of the puddles back up and dripping onto

our kitchen floor.

I've decided to give up on my pleas for a

break from the rain. We did get 24 hours of partial sun on

Saturday which mostly dried three loads of laundry and brought the

first blush of red to a few tomatoes. And then Sunday brought

another deluge, filling all of the puddles back up and dripping onto

our kitchen floor.

I could whine and complain, but the truth is that the best farmers roll

with the punches. If they get record low July temperatures, they

plant more cool season crops. While I gave up on lettuce as soon

as the first heat wave hit, my garden mentor just kept planting and is

still eating sweet lettuce. Time to follow her lead and focus on

the fall

garden!

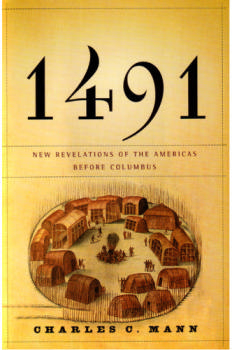

I

have to admit, I was raised on the "Noble Savage" belief that American

Indians had a pure connection with the nearly untouched wilderness they

lived in. I spent my childhood running wild and pretending that I

was an Indian, not a plain old American of mixed European

descent. My preservation ethic was built in large part on these

beliefs...which have now been debunked by the scientific community.

I

have to admit, I was raised on the "Noble Savage" belief that American

Indians had a pure connection with the nearly untouched wilderness they

lived in. I spent my childhood running wild and pretending that I

was an Indian, not a plain old American of mixed European

descent. My preservation ethic was built in large part on these

beliefs...which have now been debunked by the scientific community.

In actuality, evidence suggests that the pre-Columbian American Indians

lived in a highly constructed landscape. Over two thirds of the

United States was devoted to farmland, game was scarce (having been

hunted close to extinction near settled areas), and forests were young

and impacted by frequent, human-lit fires.

Then Europeans arrived and brought with them diseases that nearly wiped

out the Native American population. The suddenly human-free,

formerly

cultivated landscape gave rise to huge populations of bison, elk, deer,

and passenger pigeons, which feasted on corn left uneaten by dead

Indians. Then the forests began to grow up and take over the

cultivated land, so that explorers in the eighteenth century reported

vast expanses of "virgin" forests.

Despite, or perhaps because of, the deeply human-impacted nature of the

American landscape, we have a lot to learn from the American

Indians. This week's lunchtime series summarizes the permaculture

implications of Charles C. Mann's fascinating book 1491:

New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus.

I highly recommend you check the book out of your local library and

peruse it on a suddenly sunny Saturday between visits to the wringer

washer, the way I did.

| This post is part of our American Indian Permaculture lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

The Graupner

Funky Chicken is your chance to really give that troubled rooster

something to think about when he sees a super large hen flying

overhead. These birds won't be laying any eggs, but they seem like a

fun way to enjoy an afternoon at the park while spreading the word on

how cool it is to fly a chicken.

Congratulations,

Allie! You are our new Egyptian Onion winner!! Drop

me an email with

your mailing address and we'll pop your top bulbs in the mail.

Congratulations,

Allie! You are our new Egyptian Onion winner!! Drop

me an email with

your mailing address and we'll pop your top bulbs in the mail.

For everyone who didn't

win --- don't worry, those onions produce like crazy. There will

be more to give away next year, and I already know we have surplus snow

pea seeds and daffodil bulbs to give away soon. It was great to

hear from you all!

Cahokia was an

ill-fated, American Indian settlement near present-day St. Louis.

When the city was settled around 1,000 A.D., Indian

populations had grown to such a level in the eastern United States that

game was becoming scarce. Luckily, maize (corn) was making its

way north from Central and South America, allowing the Indians to

replace their hunting lifestyle with a more agricultural one.

One visionary leader realized that

changing to a lifestyle centered

around maize would require building granaries to store the kernels over

the winter. He figured the best way to go about it would be to

create a huge communal granary so that the combined might of the

community could protect the maize from depradations by neighboring

groups. Some 15,000 people joined this unnamed leader in his

quest to construct a giant city --- the largest north of the Rio Grande

--- and to plant vast fields of maize.

One visionary leader realized that

changing to a lifestyle centered

around maize would require building granaries to store the kernels over

the winter. He figured the best way to go about it would be to

create a huge communal granary so that the combined might of the

community could protect the maize from depradations by neighboring

groups. Some 15,000 people joined this unnamed leader in his

quest to construct a giant city --- the largest north of the Rio Grande

--- and to plant vast fields of maize.

Unfortunately, the population of Cahokia grew so large that the water

from the stream flowing by the city couldn't support the city's

people. So the Cahokians channeled a nearby stream from its

normal path, rerouting the water to join their existing stream and

turning their water supply into a river. More water! More

maize! More people!

The Cahokians continued to clear the surrounding land, cutting down

trees as building material, for fires, and to open up land to grow more

maize. Eventually, disaster struck. Heavy storms which

would have been soaked up by forest quickly ran off the agricultural

fields, bloating the river, and causing floods and mudslides in the

city of Cahokia. A subsequent earthquake was the last straw which

broke Cahokia's back. Within a few hundred years of its

inception, the city had

dissolved back into the earth.

The story sounds astoundingly familiar. Clearcutting, stream

channelization, monoculture, and overpopulation leading to flooding and

ecological

collapse --- it could be set next door to my house. The end of

the story, though, is something I only see dimly in modern

agriculture's future. The Indians fled the city and developed a

more sustainable agricultural system based on small fields of maize

surrounded by managed forests of fruit and nuts. Maybe those

Noble Savages were pretty smart after all.

| This post is part of our American Indian Permaculture lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

We added anti-deer

machine#5 to the upper garden to cover a another weak point in our

perimeter. I had to use the cat bowl to get a more full dinging sound.

Sorry, Huckleberry....

Just found out today from a neighbor that a large black

panther* has been spotted less than a mile from us. Maybe this shield of

noise will send a signal to this new player in the woods to stay away

from us and our chickens?

*"Panther" is the local word for Mountain Lion. Although Mountain Lions are usually light brown, the half dozen sightings we've heard of locally in the last two years have all been of large, black cats.

| We finally solved the deer in

the garden problem, and the solution was so elegant we gave it a new

website. Check out our deer

deterrent website for free plans! |

Remember how I experimented with chemical

versus organic methods of acidifying the ground for our blueberries?

The results are in, and I'm afraid the chemicals won.

Remember how I experimented with chemical

versus organic methods of acidifying the ground for our blueberries?

The results are in, and I'm afraid the chemicals won.

I only had a dozen data points, so the results of my paired t-test

weren't significant. But there was a definite trend toward better

health among the blueberries grown on sulfur-treated soil versus those

grown on pine-needle-treated soil. The photo to the right shows

one of the stressed plants --- yellow leaves with green veins are a

textbook sign of iron deficiency due to high pH.

I guess I'll probably buy some more elemental

sulfur to drop the pH in the short term, but will also keep

applying pine needles as more of a long term fix.

The Amazonian forest is considered by many

environmentalists to be the Holy Grail of untouched biodiversity.

Or it was, until recently when scientists started uncovering evidence

that anywhere from 8% to 100% of the Amazon forest is anthropogenic.

The Amazonian forest is considered by many

environmentalists to be the Holy Grail of untouched biodiversity.

Or it was, until recently when scientists started uncovering evidence

that anywhere from 8% to 100% of the Amazon forest is anthropogenic.

Slash and burn agriculture is currently the norm in the Amazon basin,

and for a long time scientists assumed that slash and burn was the

ancient method of managing the forest. In this technique, farmers

hack a small opening out of the forest, burn the fallen trees, then

plant crops in the resultant rich bed of ash. After a few years,

trees begin to grow up in the gap, and farmers move on to cultivate a

new area. Although slash and burn is harmful to the air, the

method is vastly superior to trying to till the poor soil, which would

ruin the land in less than a decade. Instead, slash and burn

seems to be marginally sustainable.

The slash and burn technique, though, is

clearly dependent on the European introduction of metal axes.

Using the Amazonians' indigenous stone axes, scientists estimate it

would have taken about three weeks to chop down a single tree.

Creating a forest gap in this scenario must have been a long term

undertaking with long term rewards.

The slash and burn technique, though, is

clearly dependent on the European introduction of metal axes.

Using the Amazonians' indigenous stone axes, scientists estimate it

would have taken about three weeks to chop down a single tree.

Creating a forest gap in this scenario must have been a long term

undertaking with long term rewards.

Scientists are now beginning to understand that slash and burn was

merely a method that Indians resorted to after disease devastated their

populations. Previously, the Amazonians did hack gaps out of the

forest canopy, but into each gap they planted small food crops like

manioc between carefully selected tree species. The trees were

the real crop, with the manioc being a secondary addition to their

diet. Over one hundred carefully bred tree species now dot the

Amazonian forest with their edible fruit. In essence, the

Amazonians were creating a forest

garden.

| This post is part of our American Indian Permaculture lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

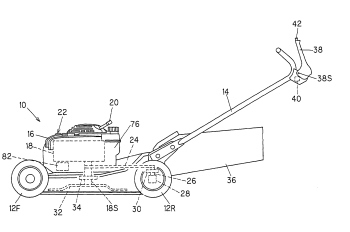

The new mower lost its get up and go today,

which prompted a search of the internet for some free advice.

The new mower lost its get up and go today,

which prompted a search of the internet for some free advice.

Samuel Goldwasser

has a fine collection of tips and instructions for the do it yourself

crowd. He is of the opinion that most lawn mowers function on a low

compression ratio and therefore can do without the high octane fuel.

Our mulch machine

just needed a new spark plug and a bit of oil to get back in the game.

Finally! The first four

tommy-toes! (Yes, I can count --- Mark snitched one before I was

able to take the picture.) They are nearly two weeks later than

last year, but are no less delicious for their lateness.

Finally! The first four

tommy-toes! (Yes, I can count --- Mark snitched one before I was

able to take the picture.) They are nearly two weeks later than

last year, but are no less delicious for their lateness.

Our butter dealers told Mark that you just have to expect to lose the

whole harvest one year in ten down in these bottoms. I'm a huge

believer in diversification in farming --- unless the flood waters come

up here and physically wash us away, we're bound to do well with at

least a few crops. The fall peas and broccoli, for example, are

growing a mile a minute.

And I believe our luck is changing. Folks nearby got six inches

of rain in a sudden downpour Tuesday, but we only got a quarter of an

inch. Maybe we'll have a summer harvest yet!

Amazonians also developed a method called

terra preta to increase the fertility of their low-nutrient

soils. Scientists estimate that up to 10% of the Amazon's soil

consists of this man-made, high fertility, "dark earth." Terra

preta is high in phosphorous, calcium, sulfur, and nitrogen, is rich in

organic matter and microorganisms, and has been shown to have elevated

moisture and nutrient retention capabilities. The soil grows good

crops too, even hundreds of years after being created.

Amazonians also developed a method called

terra preta to increase the fertility of their low-nutrient

soils. Scientists estimate that up to 10% of the Amazon's soil

consists of this man-made, high fertility, "dark earth." Terra

preta is high in phosphorous, calcium, sulfur, and nitrogen, is rich in

organic matter and microorganisms, and has been shown to have elevated

moisture and nutrient retention capabilities. The soil grows good

crops too, even hundreds of years after being created.

Although popular

articles about terra preta suggest that all you have to do is

create charcoal and work it into the ground, terra preta production is

actually more complicated. The Indians mixed charcoal with

excrement and animal bones in long trenches when creating terra

preta. The charcoal consisted of charred wood, weeds, cooking

waste, and crop debris. Copious pottery shards in the terra preta

suggest to me that the technique may have begun as simply a modified

midden heap.

I'm curious about whether terra preta could be the answer to some of

our waste disposal problems. I try to keep our homestead as

self-sufficient as possible, and the influx of cardboard from our automatic chicken waterer

microbusiness doesn't seem to fit that model. I've tossed some of

it on the worm bin, but am starting to suspect that I'm overwhelming my

poor worms with the mass of sodden cardboard. (Recycling isn't

really an option since we live an hour away from the nearest

facility.) Could I use the excess cardboard along with those

troublesome chicken bones and maybe even our excrement to create terra

preta? Only time and experimentation will tell.

| This post is part of our American Indian Permaculture lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

Hae-Jin

Kim has an interesting idea to harness the waste heat generated by

a typical refrigerator. It's not quite enough to function as a hot

plate, but 150 degrees might be able to dry a pair of socks or keep a

burrito warm? I wonder if this heat could be channeled to a small green

house structure for a steady flow of warmness as long as the

refrigerator is on?

I was raised on the old USDA food pyramid, and

even though I know it's not quite healthy, I still tend to plan my

meals based on its teachings. I try to make sure every meal has

plenty of vegetables, a bit of protein, a bit of starch. And, of

course, I eat fruit like it's candy.

I was raised on the old USDA food pyramid, and

even though I know it's not quite healthy, I still tend to plan my

meals based on its teachings. I try to make sure every meal has

plenty of vegetables, a bit of protein, a bit of starch. And, of

course, I eat fruit like it's candy.

But mushrooms mystify me. They have so many vitamins and minerals

in them that they are clearly in the vegetable group. On the

other hand, they are relatively high in protein, which means that I

might lump them in with meats (where I put eggs and legumes.)

Given this week's massive harvest, I'm tempted to say that shiitakes

fill both niches. After all, we have enough mushrooms this week

to cover the entire food pyramid!

1491's

summary of American Indian agricultural practices reveals societies

full of people a lot like current farmers. Neither Indians nor farmers aren Noble

Savages who live in totally harmony with the land, but we are constantly striving to achieve

a more sustainable system. I hope that recent forays into

permaculture show that we are on the cusp of reaching a new

relationship with the natural world.

1491's

summary of American Indian agricultural practices reveals societies

full of people a lot like current farmers. Neither Indians nor farmers aren Noble

Savages who live in totally harmony with the land, but we are constantly striving to achieve

a more sustainable system. I hope that recent forays into

permaculture show that we are on the cusp of reaching a new

relationship with the natural world.

Although I'm a bit sad to see my childhood image of Indians dashed, in

a way the reality is much cooler. I wonder what other ancient,

permaculture-like techniques scientists will turn up in the years to

come?

| This post is part of our American Indian Permaculture lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

I've had this 18 volt Black and Decker

Firestorm drill for over 4 years now and it's still as strong and

dependable as the first day I got it.

I've had this 18 volt Black and Decker

Firestorm drill for over 4 years now and it's still as strong and

dependable as the first day I got it.

Its taken some serious drops and bangs over the years ...proving itself

in the heavy duty tool league at a price well below the heavier brands.

I've worn out one battery so far...but still have 2 more that provide

more than a day's worth of work at an impressive charge time.

Over

the last year, we've made mountains and mountains of trash, which we

tossed in the barn to be dealt with later. This photo shows about

half of the trash, and I'd estimate three quarters or more of it is

plastic packaging.

Over

the last year, we've made mountains and mountains of trash, which we

tossed in the barn to be dealt with later. This photo shows about

half of the trash, and I'd estimate three quarters or more of it is

plastic packaging.

We cut down on our trash

by buying in bulk and by using food scraps, paper, and cardboard on the

farm. But plastic seems inevitable. Milk jugs, styrofoam

meat trays, thin sheets of plastic wrapping everything from toilet

paper to boxes of tea bags. In many cases the plastic is entirely

redundant, seemingly tacked on for the sole purpose of filling my barn

with trash.

The worst part is that plastic isn't really

recyclable. So

how can we cut down on our mountain of trash? The best options I

can come up with are:

- finding a way to buy even more things in bulk

- growing more of our own food

- buying less

If you have any better

ideas, I'm all ears! I'm especially interested in ways you

might reuse plastic on the farm.

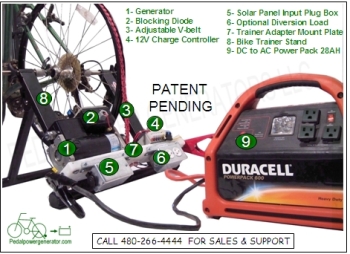

The folks at pedalpowergenerator

have added some step by step videos to the free diy section.

The folks at pedalpowergenerator

have added some step by step videos to the free diy section.

This setup takes advantage of an adjustable V-belt, which will cost you

50 bucks. You take the tire off your wheel and replace it with the

V-belt to get maximum efficiency from the exerted energy. The

Duracell power pack functions as a storage unit with a built in

inverter and usually sells for a bit over a hundred dollars. The

generator will cost you more depending on which one you choose, and all

that's left is the charge controller and blocking diode, which can be

had for under 100. I almost forgot the bike stand....which could be

made from scrap material or you can just buy the industrial model.

I've been studying different versions of pedal

power over the years and would say this configuration is the

smartest one I've seen yet. If you add a small solar cell and reduce

your use you might just make enough power to get you through the day.

The fall flowers are starting to bloom, so I wandered outside to see

which plants are attracting the honeybees. Our worker bees seemed

to be flying right past ironweed and wingstem and making a bee line

directly toward the Virgin's Bower.

These pretty white flowers are relatives of the cultivated Clematis you

might grow in your flower bed, but around here Virgin's Bower grows

wild in open, weedy areas. The vine is currently twined around

several spots which I plan to "clean up" this winter --- knocking down

the wild plants to make way for some extra berries. Given

Virgin's Bower's attractiveness to the bees, though, I wonder if I

should move some into the forest

garden to act as a nectary.

Microhydropower.com has

some exciting new products that allow the common guy to harness the

power of a small stream for the purpose of generating electricity.

Their setup will cost you about 3 thousand bucks...and then you'll need

to figure out how to store it and get it where you need it.

Not a bad solution for home made electricity if you live close enough

to a steady stream of water.

Remember how I pruned and trained my

peach trees to the open center system last winter? A good

orchardist would have done a followup pruning and training in June, but

I missed the boat and only just now got around to my summer

pruning. As you can see in the photo on the left, water sprouts

had sprung up vertically from the center of the tree, so I had to do a

lot of cutting. Optimally, these water sprouts would have been

trimmed back when they were much shorter so that all of that energy

would have gone into growth of the main branches.

Last winter's technique of training the tree with yarn seems to have

worked very well. Sunday, I cut off the old pieces of yarn since

they were starting to grow into the branches. (Once again, this

would have been better done six weeks ago.) I was expecting

branches to spring back to their former vertical form, but instead they

sat just where I'd trained them --- success! So I added a few new

training yarns back in to hold down lengthened branches and called it a

day.

Shame-faced plug: Check out our new Avian Aqua Miser website full of

information about the home made

chicken waterers which fund this blog.

--- Naomi

That's

a wonderful question, Naomi! The truth is that when I bought our

farm, my head was in a similar state. As a result, it took us

years to actually move here. After that we wasted a lot of time

running around like chickens with our heads cut off, trying to figure

out where to start. Hopefully we can save you from making the

same mistakes.

That's

a wonderful question, Naomi! The truth is that when I bought our

farm, my head was in a similar state. As a result, it took us

years to actually move here. After that we wasted a lot of time

running around like chickens with our heads cut off, trying to figure

out where to start. Hopefully we can save you from making the

same mistakes.

Before we dive right

into the specifics, I'd like to point you to a previous lunchtime

series on the

top qualities you'll need to be a successful homesteader.

I'm going to stick to the nitty gritty in this week's lunchtime series,

but it's worth cultivating the qualities I recommend there too ---

moderate strength, frugality, ties in the community, and pacing.

| This post is part of our Starting Out on the Homestead lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

Our tomatoes are now just a big blob of

twisted and mangled branches in a few piles outside the garden.

Our tomatoes are now just a big blob of

twisted and mangled branches in a few piles outside the garden.

The blight took hold pretty strong here. We're holding off on deleting

the tommy toe varieties in hopes of getting some more healthy ones

before the blight robs them of all their delicate juices.

It was just too depressing to think of watching them die a slow death

over the next few weeks. This way we can double down on some fall peas

and other Autumn crops.

For one week, we ate tomatoes --- a handful of

Blondkopfchen tommy-toes, a Cherokee, and a Green Zebra. Then,

much faster than their ripening, the blight consumed the plants.

Walking out our door, all I could see was curling, brown tomato

leaves. Green fruits were dropping to the ground while red fruits

were rotting on the vine.

For one week, we ate tomatoes --- a handful of

Blondkopfchen tommy-toes, a Cherokee, and a Green Zebra. Then,

much faster than their ripening, the blight consumed the plants.

Walking out our door, all I could see was curling, brown tomato

leaves. Green fruits were dropping to the ground while red fruits

were rotting on the vine.

We did nearly everything right. We started our heirlooms from

seed, rather than risking the infected plants in the big box

stores. We fed them well and gave them trellises. But the

endless July rain took its toll, and blight spores found their way to

our tomatoes.

Monday morning, we made the hard decision to pull them all out rather

than building up our farm's blight spore bank further. I couldn't

bear to be involved, so I begged Mark to do the deed. Still, I

was nearly in tears. Goodbye, dreams of tomatoes.

Hello, dreams of the best fall crop ever! We're going to fill the

holes with even more fall veggies so that we can, hopefully, eke out

our harvest much later in the year. Although tomatoes are my

favorite vegetable crop, I suspect that extra months of fresh peas,

greens, and root crops may heal the wound in my heart. Meanwhile,

take a look at this yellow watermelon we had for lunch yesterday!

(I can't bear to include a photo of the blight.)

Shame-faced plug: Our new Avian Aqua Miser website

gives Mark's invention space to spread its wings.

When

we finally moved onto the farm, I had spent years dreaming and planning

about what I wanted our eventual homestead to look like. I was so

excited to be realizing my dream that I started planting things

willy-nilly, with the result that a lot of my early effort went for

naught. I wish I'd had the foresight to spend a few days

assessing my property before beginning on any of the projects.

When

we finally moved onto the farm, I had spent years dreaming and planning

about what I wanted our eventual homestead to look like. I was so

excited to be realizing my dream that I started planting things

willy-nilly, with the result that a lot of my early effort went for

naught. I wish I'd had the foresight to spend a few days

assessing my property before beginning on any of the projects.

If I could go back in

time, my first step would be to make a map of the

farm. Since most of my property is wooded, I'd just focus on the

areas we plan to to farm for now. Within that area, I'd map

existing structures, water sources (well and creeks), power and

telephone lines, septic systems and/or sewer lines, and

driveways. I'd also keep my eye out for existing cultivated

fields, orchards, or pastures. Fences are very useful --- put

those on the map.

Next, I'd start thinking

about the land as a farm. Which areas

are flat or have little slope? Which areas have good soil or poor

soil? It's very much worth it to send off some soil samples to

the extension service to find out if your soil needs help in certain

areas. But you can also learn a lot by just looking at what's

currently growing in an area --- blackberry brambles are a good sign

because they mean your soil is relatively rich, while broomsedge is

sign of worn out soil. You should use high quality soil for your

garden and orchard, if possible.

| This post is part of our Starting Out on the Homestead lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

I was talking with one of my uncles on the phone today about this year's

blight and he still has some hopes for his tomato crop. His remedy is

to clip off the offending leaves stricken with blight, get them far

away from the garden, cross your fingers and wait.

Anna and I considered this option...but decided the stress from

multiple leaf trimming would set back the fruit production even more.

This episode of vegetable loss has further reinforced my new way of

thinking which involves rolling with mother nature instead of fighting

her. Not unlike the theme of my favorite Rolling Stones song "You can't

always get what you want".

Although the traditional three

sisters method of growing beans, corn, and squash together

worked miserably in my garden last year, I decided to modify it and

give the method another shot. The concept is sound --- the

problem was that my vegetable varieties weren't right. The squash

was too vigorous for my sweet corn and bush beans and ended up

overwhelming the entire garden plot.

This time around, I'm instead growing cucumbers amid my beans.

Since cucumbers are much less vigorous than squash, they haven't taken

over the bush beans. They did try to run off the sides of the

beds, though, so I gave them some teepee trellises to climb.

The nitrogen from the bean roots seems to be doing its job well.

The cucumbers I planted amid the beans are much larger and greener than

the ones I planted earlier this summer on their own. And the

beans don't seem to mind the little bit of competition the cucumbers

give. Success!

Shame-faced plug: The new Avian Aqua Miser website is chock full of

information about chicken

waterers.

Based on your assessment

of the property, it's time to make some long term plans. These

plans don't have to be set in stone, of course, but they will

definitely help you prioritize which areas to work on first and will

prevent you from having to move your fruit trees three times.

Start

out with a ten year plan. What are your goals for the next

decade? To grow all of your own food? To live in a forest

garden?

To be running a chicken hatchery as your full time job? What

physical changes to the property will those goals entail? Break

your goals down into manageable chunks and prioritize each one.

Do you plan to build any new structures? If so, where will they

be? Do you need to bury water lines or build driveways?

These steps will be easiest if you put them early in your long range

plan rather than trying to bury a water line through your vegetable

garden, the way we did.

If you want to have an orchard, pasture, or garden, it's best to start

planning them now. If possible, plan your trees where they will

shade your house in the summer but won't block passive solar heating in

the winter. Gardens are most effective if they are very close to

the house so that you can step out the door and pull a weed. Make

a

copy of your map and add your long range goals onto it.

| This post is part of our Starting Out on the Homestead lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

Its been over 2 weeks now since we've had any

deer damage to the garden.

Its been over 2 weeks now since we've had any

deer damage to the garden.

We've got all 5 deer

deterrent devices running 24 hours a day now due to the cloudy days

we've had lately.

The experiment will continue till the end of our fall growing season,

at which time we should know if this is indeed a cheap and long term

mechanical solution for the deer problem.

| We finally solved the deer in

the garden problem, and the solution was so elegant we gave it a new

website. Check out our deer

deterrent website for free plans! |

Remember my ambitious plans to construct

a forest garden between the baby fruit trees near the barn? I

planted a couple of beds, then the normal gardening season started and

the project got pushed onto the back burner.

Remember my ambitious plans to construct

a forest garden between the baby fruit trees near the barn? I

planted a couple of beds, then the normal gardening season started and

the project got pushed onto the back burner.

Since then, I've started a slightly less ambitious method of forest

gardening, one that fits in the scanty time gaps between vegetable

gardening. Instead of trying to create an entire forest garden in

one step, I've been creating "forest islands" by slowly extending the

raised beds around each tree. Whenever I pull weeds and don't

have anything better to do with them, I'll dump a wheelbarrow load

against the side of a tree's raised bed. A few weeks later, the

weeds have rotted down into rich soil.

My oldest peach tree has been receiving this

treatment (albeit in a more willy-nilly fashion) for nearly three years

now. Wednesday, I pulled out another mass of weeds and poked

around at the humps of soil which now expand out in two directions from

the raised bed. White threads of fungi, a startled toad, and a

brilliant centipede all turned up --- signs that my little ecosystem is

healthy.

My oldest peach tree has been receiving this

treatment (albeit in a more willy-nilly fashion) for nearly three years

now. Wednesday, I pulled out another mass of weeds and poked

around at the humps of soil which now expand out in two directions from

the raised bed. White threads of fungi, a startled toad, and a

brilliant centipede all turned up --- signs that my little ecosystem is

healthy.

A little judicious shoveling and transplanting later and I've created a

forest island there. I planted comfrey and bee balm under the

peach's canopy, and fennel, echinacea, rhubarb, and Egyptian onions

further out from the trunk. My primary goal with these plantings

is weed control, with a secondary goal of strengthening the soil using dynamic

accumulators, and a tertiary goal of feeding hummingbirds and

parasitic wasps. Of course, I also chose the plants because I

have masses of them that need to come out of other parts of the

garden. I'm excited to see how this new forest garden island will

take hold!

Shame-faced plug: Create your own unique chicken waterer with our DIY

instructions.

Unless

you happen to have bought a farm from an organic gardener, chances are

that fertility should be your first concern when it comes to

gardening. Although I don't recommend that beginning homesteaders

do much in the way of livestock, I do believe that everyone should

start a worm

bin immediately. Worms take nearly no time and create some

high quality compost to get you started.

Unless

you happen to have bought a farm from an organic gardener, chances are

that fertility should be your first concern when it comes to

gardening. Although I don't recommend that beginning homesteaders

do much in the way of livestock, I do believe that everyone should

start a worm

bin immediately. Worms take nearly no time and create some

high quality compost to get you started.

If you have a half hour per day to put into

the operation, I also recommend that you build

a chicken tractor with two to five chickens in it. (Start

small!) You can use the chicken

tractor to add fertility to worn out parts of the soil while you

start gardening in higher quality areas.

Next, start scrounging for free fertility in the surrounding

area. If you live in town or near town, stock up on

garbage bags full of leaves in the fall. If you're out in the

country, start asking your livestock-owning neighbors what they do with

their manure.

Chances are they'll give it to you for free if you haul it away.

If your farm has a large wooded area attached, you should also go out

hunting stump

dirt, which is some of the best potting soil around.

Stop and chat with the tree cutting folks and ask them if they will

dump some mounds of wood chips in your yard --- they often need a way

to dispose of these chips and will give them to you for free. Be

aware that you need to let wood chips rot for a couple of years before

using them as mulch.

Building the fertility of your soil is a long term investment in your

land. Not only that, mulch will cut your weeding work in half

while increasing yields. You will have a better garden in the

long run if you hunt down fertility sources before planting a huge

garden.

| This post is part of our Starting Out on the Homestead lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

Our one Cochin

hen is in a broody mood again. The plan is to put her in this new

mini-coop sometime tomorrow when we pick up some fertilized eggs from a

friend who has a rooster.

I'm looking forward to this for completely selfish reasons. Each time I

urge her off the nest and steal her eggs she immediately begins chewing

me out with her very harsh tongue. It usually only lasts for a few

minutes....but I've always had a problem with listening to angry

females on a tyrannical rant.

I installed an Avian Aqua

Miser so that she can get to it without leaving the nest. I hope

this makes her stay a bit more comfortable.

Read all of the entries about

our broody hen:

|

We took advantage of a brilliantly sunny day

on Thursday to peek into two of the hives. The weak hive

was still just as weak --- the photo to the left shows how they still haven't finished building on

all of the frames in their brood box. Worker populations in that

hive are distressingly low, which means they're not saving much honey

and may not survive the winter.

We took advantage of a brilliantly sunny day

on Thursday to peek into two of the hives. The weak hive

was still just as weak --- the photo to the left shows how they still haven't finished building on

all of the frames in their brood box. Worker populations in that

hive are distressingly low, which means they're not saving much honey

and may not survive the winter.

So I popped out an empty frame from the weak hive and swapped it with a

frame of capped brood from one of our strong hives. The capped brood will

hatch out into hundreds of workers who will build up the weak hive's

population, and I suspect the strong hive won't miss the new workers

that much.

I hadn't thought ahead to realize that the frame of capped brood would

be covered with nurse bees tending to the brood, so I got a little bit

worried as I carried this buzzing frame to the new hive. I

needn't have been concerned --- I've now read that the nurse bees will

be assimilated into the weak hive with no problems.

The strong hive was not thrilled at having their lives interrupted

during such a big honey flow, so I made my inspection as fast as

possible and got out. No stings this time, though --- I'm so glad

not to have to be inspecting on a

cloudy day when the hive is crowded!

Shame-faced plug: The Avian Aqua Miser poultry waterer works great

for turkeys and ducks as well as chickens.

If

you're like me, planning is fun but you really want to start eating

your own tomatoes ASAP. My gardening advice for beginning

homesteaders is --- think big, start small.

If

you're like me, planning is fun but you really want to start eating

your own tomatoes ASAP. My gardening advice for beginning

homesteaders is --- think big, start small.

You will be a lot happier in the long run if you spend most of your

energy the first year working on garden infrastructure. Plan

permanent paths based on nodes,

and make sure that your paths are wide enough. I've found that

paths between garden beds should be about three feet wide to give me

room to easily maneuver a wheelbarrow, lawnmower, and garden cart

through them.

Think about irrigation from the beginning. We started planting

before we had any way to get water to our crops, so we ended up hauling

water in five gallon buckets from the creek. Don't repeat our

mistakes --- check out our irrigation

series for more information.

Chances

are you're going to have to deal with deer or other animals nibbling

your crops. If you have a small garden, go ahead and put in the

time up front to build a fence. If your garden is going to be

large, like ours, now's the time to start experimenting with deer

deterrants

the way Mark has. There is nothing worse than waking up one

morning to find out that your carefully tended garden has been eaten

overnight.

Chances

are you're going to have to deal with deer or other animals nibbling

your crops. If you have a small garden, go ahead and put in the

time up front to build a fence. If your garden is going to be

large, like ours, now's the time to start experimenting with deer

deterrants

the way Mark has. There is nothing worse than waking up one

morning to find out that your carefully tended garden has been eaten

overnight.

When you are ready to plant, I highly recommend building

wall-less raised beds. Or, if you have access to the

materials, build

no-till raised beds

to protect your soil ecology. Raised beds are very energy

intensive at first, but they're good for your garden and will also

force you to start small.

You may also be dreaming of fruit trees. It can't hurt to put in

a few your first year, but make sure that you have time to take care of

the ones you put in. It's better to build a really good raised

bed for one tree the first year than to hastily throw ten trees in the

ground and watch them all die.

| This post is part of our Starting Out on the Homestead lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

It was a smooth transfer from the chicken tractor to the mini coop.

We picked 15 of the best looking fertilized eggs for our Cochin to

adopt as her own. Now we wait a few weeks to see how dedicated she is

to bringing in the next generation of egg layers and broilers.

Read all of the entries about

our broody hen:

|

It looks like butterflies aren't the only

insects who like our echinacea. I caught this praying mantis in

the act of consuming a butterfly from the head down yesterday afternoon.

Yum!

It looks like butterflies aren't the only

insects who like our echinacea. I caught this praying mantis in

the act of consuming a butterfly from the head down yesterday afternoon.

Yum!

Shame-faced plug: Mark's invention is

built around a device called a chicken

nipple. Sometimes I think he invented our waterers just

because he liked the name.

Eventually,

every homesteader will be faced with the thorny issue of

livestock. Chances are that your homesteading dreams included

lots of animals giving you fresh milk, eggs, and meat. The

reality,

though, is that animals can use up your time so quickly that you're

working for them instead of vice versa.

Eventually,

every homesteader will be faced with the thorny issue of

livestock. Chances are that your homesteading dreams included

lots of animals giving you fresh milk, eggs, and meat. The

reality,

though, is that animals can use up your time so quickly that you're

working for them instead of vice versa.

My first piece of advice for new homesteaders is to make a distinction

between pets and livestock. Use your own judgement on the pet

front --- we love our cats and dog and believe that the time we put

into them is totally worth it for our own mental stability. We don't even pretend that

our pets pull their weight on the farm with their limited

mouse-catching and deer-chasing abilities. But we also know that having

more than our current two cats and one dog would be too much for us to

handle.

In

the world of livestock, as I mentioned earlier I do recommend that all

homesteaders start out with a worm bin. Most homesteaders will

also be able to handle a few chickens either their first or second

year, especially if they are careful to start small. If you are

big

honey eaters the way we are, I would recommend getting honeybees around year two

or three, once you're established and have a bit of time to devote to

their care.

In

the world of livestock, as I mentioned earlier I do recommend that all

homesteaders start out with a worm bin. Most homesteaders will

also be able to handle a few chickens either their first or second

year, especially if they are careful to start small. If you are

big

honey eaters the way we are, I would recommend getting honeybees around year two

or three, once you're established and have a bit of time to devote to

their care.

What

about bigger animals? We divide larger livestock into three main

categories --- draft animals, dairy animals, and meat animals.

Due to

our own failed experience with mules, I recommend that unless you've

had experience with draft animals in the past and have at least an hour

a day to devote to them, you save draft animals for later (if

ever.) To me, dairy animals are in the same boat --- you need to

be willing to be tied down twice a day for the rest of your life.

(With just our pets, chickens, bees, and worms, we can go out of town

for a few days without needing to find a farm-sitter.)

What

about bigger animals? We divide larger livestock into three main

categories --- draft animals, dairy animals, and meat animals.

Due to

our own failed experience with mules, I recommend that unless you've

had experience with draft animals in the past and have at least an hour

a day to devote to them, you save draft animals for later (if

ever.) To me, dairy animals are in the same boat --- you need to

be willing to be tied down twice a day for the rest of your life.

(With just our pets, chickens, bees, and worms, we can go out of town

for a few days without needing to find a farm-sitter.)

If you want to branch out beyond worms, bees, and chickens, I

would start with meat animals. Even so, I wouldn't consider

embarking on the project unless I had a good pasture and a place to

store hay for the winter. Small meat animals like poultry and

rabbits might fit into year three or four of your ten year plan, but I

suspect that larger animals would be closer to year nine or ten.

Of course, as with all parts of your homesteading plan, you should

decide what's most important for you. If all you've ever dreamed

about is having a milk cow, then by all means move it up to year two

and put off the garden until year four. After all, the best part

of a homestead is the way it allows you to choose your own

adventure. Don't forget to have fun!

| This post is part of our Starting Out on the Homestead lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

We didn't really completely give up on

tomatoes for the year, despite pulling out our

blighted tomato plants

on Monday. The saving grace of tomatoes is that they come up

prolifically from seed, so every garden tends to have volunteers.

Ours is no exception.

We didn't really completely give up on

tomatoes for the year, despite pulling out our

blighted tomato plants

on Monday. The saving grace of tomatoes is that they come up

prolifically from seed, so every garden tends to have volunteers.

Ours is no exception.

I tied up the best volunteers who were already in okay spots --- beside

the pear tree and in the berry patch, far from the blighted

tomatoes. Then Mark transplanted some younger volunteers to

garden beds.

I even started a few tommy-toes from seed. I figure we probably

don't have time for them to bear before the fall frost, but it's worth

a shot!

Shame-faced plug: Lots of our customers have started using our DIY kits

to make chicken

bucket waterers to water up to 50 birds.

We tried incubating some eggs with an

incubator a couple of winters back and didn't have any to make it

because the outside temperature was fluctuating too much.

We tried incubating some eggs with an

incubator a couple of winters back and didn't have any to make it

because the outside temperature was fluctuating too much.

Chickenschickens.com

has a nice set of free plans to make your own brood box for the typical

Styrofoam incubator.

If I didn't have the Cochin hen to

do most of the mothering work I'd be building one of these to get ready

for operation brood.

One of our sweet potato plants started

blooming last week, clearly illustrating the plant's relationship to

morning glories. I'd never seen sweet potato flowers before, so I

poked around on the web to see if I should cut off the blooms

the way you do with garlic.

One of our sweet potato plants started

blooming last week, clearly illustrating the plant's relationship to

morning glories. I'd never seen sweet potato flowers before, so I

poked around on the web to see if I should cut off the blooms

the way you do with garlic.

It turns out that sweet potato flowers are extremely unusual, and are

actually in pretty high demand. Since sweet

potatoes are propagated vegetatively, it's hard to develop new

varieties. Blooms add an element of randomness to the plant's

reproduction --- a lot of the seeds will probably turn into shoddy or

mediocre plants, but one of the seeds might just turn out to be the

next best thing in sweet potato land.

Scientists have tried a lot of tricks to get sweet potatoes to flower,

and one of the most effective seems to be high humidity combined with

damp soil. Check! Another method they've tried involves

clipping off the ends of sweet potato vines, hoping to stimulate apical

bud growth. Since the deer got in and nibbled our sweet potatoes

once before we added a deer deterrent to that part of the garden, we

accidentally used that method too.

I plan to collect the seeds from our sweet potato flowers and give them

a shot next year. Maybe we'll develop a new variety of sweet

potato and name it after Huckleberry!

Shame-faced plug: To me, the best part of

the Avian Aqua Miser is that it's an automatic chicken waterer.

If you put a couple in a small tractor, you won't have to worry about

water for days on end.

Last winter when I started

reading and dreaming about forest gardens, I put hazels on

my list of possible forest garden plants. I was primarily

interested in the shrub because I knew we had wild hazels growing in

young areas of the woods nearby, where the honeysuckle tends to

strangle them every year and prevent them from fruiting. The fact

that Mark and I are addicted to Nutella, and that hazels can grow well

in partial shade, also added to my interest.

Last winter when I started

reading and dreaming about forest gardens, I put hazels on

my list of possible forest garden plants. I was primarily

interested in the shrub because I knew we had wild hazels growing in

young areas of the woods nearby, where the honeysuckle tends to

strangle them every year and prevent them from fruiting. The fact

that Mark and I are addicted to Nutella, and that hazels can grow well

in partial shade, also added to my interest.

I kept considering

transplanting some of the strangled shrubs out of the honeysuckle and

into the forest garden. I never got around to it, though, because

I wasn't sure if I should devote precious garden space to unproven wild

plants, or if I should find a cultivated version instead which might

bear more nuts. Last week, I finally took an hour to research

hazels, and I found so much information I had to turn it into a

lunchtime series. Stay tuned and be prepared to end up as enthused

as I am.

| This post is part of our Hybrid Hazelnut lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I tried to find something like this in the pet

department of the big store I was in last week and struck out.

I tried to find something like this in the pet

department of the big store I was in last week and struck out.

It's just a compilation of 5 scrap pieces of wood and a folded over

flap of screen material. A notch on the right side with a dab of glue

seems to be enough to anchor it to the screen frame. I hope our cats

are smart enough to adapt to a proper pet entrance which can be easily

closed down at night by shutting the window.

There's so much going on here on the farm that I can't for the life of

me choose a single thing to post about. We're still eating all

garden meals

whenever possible, and I've discovered that I suddenly like omelets

with Egyptian Onion greens in them. Our ever-bearing raspberries

are starting to fruit again, which turns the meal into a feast.

I'm also getting a bit more serious about seed-saving.

We've never had a good crop of watermelons before, so this year we

tried out four varieties. The most successful and prolific was

Sugar Baby, which is billed as being both disease and drought

resistant. I'm hoping it didn't cross with its less prolific

neighbors and that these seeds will give us an equally exciting crop

next year.

Meanwhile,

the abnormally cool and rainy July has tempted my broccoli to start

heading up in August. The bug damage has been minimal and I

staggered my plantings so I expect to be eating broccoli for several

weeks once this one is ready. Finally, a success big enough

to outweigh our potato and tomato failures!

Our broody hen

has settled in for the duration. She did hop off the nest for a

couple of minutes on Monday to eat her breakfast, but otherwise has

barely moved. It seems like she has the entire farm's biological

clock energy. We'll enjoy eating the fruits of that energy

this fall and winter.

Shame-faced plug: Our DIY kits include information on how to make a

chicken waterer for as low as $1 per bird.

My

primary question about hazels was --- is there a more prolific,

cultivated variety that I should plant instead of the wild shrubs

growing around my yard?

My

primary question about hazels was --- is there a more prolific,

cultivated variety that I should plant instead of the wild shrubs

growing around my yard?

The answer is that here

in the eastern U.S., we have both Beaked and

American Hazelnuts, but both of these wild species produce small nuts

in thick shells. In contrast, all of the hazelnuts we buy in the

store are a completely different species of hazelnut --- European

Hazelnut --- which has big seeds and thin shells.

Unfortunately, we can't

just grow European Hazelnuts here. The

European species is very sensitive to an American disease known as Eastern

Filbert Blight,

which you can see in the photo above. If you try to grow European

Hazelnuts in the eastern U.S., your shrubs will wither away. Only

American and Beaked Hazelnuts are able to resist the fungal infection.

Is there a solution to

the small nut vs. dead shrub dilemma? You bet!

| This post is part of our Hybrid Hazelnut lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Our garden learning curve has been steep this

year --- that's my new way of looking at our copious failures.

Last year, I tossed onion seeds in the ground, watched them grow like

crazy until they were as big as storebought, then ate them

until Valentine's Day.

Our garden learning curve has been steep this

year --- that's my new way of looking at our copious failures.

Last year, I tossed onion seeds in the ground, watched them grow like

crazy until they were as big as storebought, then ate them

until Valentine's Day.

This year I rotated to another part of the garden, planted twice as

many beds, and expected to eat onions for a solid year. Instead,

we ended up with a slightly lower volume of harvest and much smaller

onions. What happened?

I'm starting to realize that some crops (like onions and potatoes and,

to a lesser extent, carrots) just don't like heavy clay. We have

three different garden patches, one with excellent loam, one with

mediocre loam-clay mix, and one that's pretty much all clay. I

grew our onions in the excellent loam last year and in the nasty clay

this year, with predictable results. Next year, I'll have to be

sure to put my root crops in the loam where they'll excel and leave the

clay for veggies like greens and peas who don't really care what their

soil's like.

Shame-faced plug: I usually make our DIY chicken

waterer kits while Mark makes the ready-to-go waterers.

Many of you have probably

heard of the breeding experiments currently underway to cross American Chestnuts with

Chinese Chestnuts

and hopefully develop a hybrid that can be reintroduced to the woods

without succumbing to the chestnut blight. Scientists are taking

a page out of the chestnut project book by crossing American, Beaked,

and European Hazelnuts, hoping to develop a hazel variety resistant to

the Eastern Filbert Blight but capable of producing high quality nuts.

Many of you have probably

heard of the breeding experiments currently underway to cross American Chestnuts with

Chinese Chestnuts

and hopefully develop a hybrid that can be reintroduced to the woods

without succumbing to the chestnut blight. Scientists are taking

a page out of the chestnut project book by crossing American, Beaked,

and European Hazelnuts, hoping to develop a hazel variety resistant to

the Eastern Filbert Blight but capable of producing high quality nuts.

Efforts have been

underway for twenty years, and the hybrid hazelnuts are finally

beginning to bear fruit. According to Badgersett Research

Farm and the Arbor

Day Foundation, the

results are delicious! Good quality nuts, thin shells, and

disease resistance --- just what I was looking for.

| This post is part of our Hybrid Hazelnut lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

It would seem that 15 eggs is one egg too many for our broody Cochin hen

to sit on because she ate one the other day bringing the total down to

14.

You might want to consider leaving the empty egg shell in there with

her for safe keeping.....unless you need to know what it feels like

when a chicken's beak bites down on a human finger.

Read all of the entries about

our broody hen:

|

A couple of weeks ago, my mom came to visit. As I took her on the

grand tour of the garden, she looked toward the back of the trailer

where tall annuals had grown up over the roof. "What are those

beautiful plants?" she asked in awe.

"That's ragweed," I answered, and hurried her on by, to a more

manicured area of the yard. The truth is that we have patches of

ragweed growing all around, wherever it's hard to mow. I'd been

meaning to pull them out...until yesterday when I noticed that they are

our honeybees' new favorite plant!

All

of that pollen which makes ragweed the bane of allergy sufferers also

means that honeybees can load up on winter protein with ease. I

was first alerted to their activity when the bees' buzzing broke into

my weeding trance Wednesday morning. I stopped to watch as the

worker bees brushed their hind legs together, pushing pollen into the

bright yellow sacs at the base of their legs. I even noticed

other insects visiting the ragweed, like the little fly in the skinny

photo to the right.

All

of that pollen which makes ragweed the bane of allergy sufferers also

means that honeybees can load up on winter protein with ease. I

was first alerted to their activity when the bees' buzzing broke into

my weeding trance Wednesday morning. I stopped to watch as the

worker bees brushed their hind legs together, pushing pollen into the

bright yellow sacs at the base of their legs. I even noticed

other insects visiting the ragweed, like the little fly in the skinny

photo to the right.

The picture on the far right is an example of what our three strong

hives look like during sunny days when there's a good nectar

or pollen

flow. The first time I noticed this, I thought something was

wrong, but the truth is that it's merely a bee version of rush hour

congestion. I guess I'll have to leave some ragweed around after

this --- good thing neither Mark nor I has allergies!

Shame-faced plug: Check out the chicken

waterers which fund this blog.

I

started this adventure merely searching for a tasty hazelnut to plant

in the understory of my forest garden, but the researchers who produced

the hydrid hazel have

loftier ambitions.

They figure hazels can produce food for people, a new cash crop for

farmers, a high protein feed for livestock, and an efficient way to

make biofuel. The scientists even promise that planting woody

hazels instead of the usual annual vegetable crops will help combat

global warming.

I

started this adventure merely searching for a tasty hazelnut to plant

in the understory of my forest garden, but the researchers who produced

the hydrid hazel have

loftier ambitions.

They figure hazels can produce food for people, a new cash crop for

farmers, a high protein feed for livestock, and an efficient way to

make biofuel. The scientists even promise that planting woody

hazels instead of the usual annual vegetable crops will help combat

global warming.

I'm most intrigued by

the potential to produce hazelnut oil. As

long-time readers probably know, we've been interested in the idea of making our

own cooking oil

for a while. We had settled on sunflowers as the easiest crop to

turn into oil on our farm, but now I'm starting to wonder if hazelnuts

wouldn't be easier. Hazelnuts have the definite advantage over

sunflowers of being perennials which need less care after the initial

planting. And even though deer and squirrels love hazelnuts,

birds are less attracted to them than to sunflowers --- our sunflower

crop this year went into the bellies of birds.

Producing our own oil is

a long term goal which will require several

steps, but it wouldn't hurt to start growing hazels as a potential

source of oil. After all, hazelnut

oil has a nearly identical nutritional makeup compared to the healthy

olive oil.

| This post is part of our Hybrid Hazelnut lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I was picking up some bee hive supplies

today and heard a weird tale of some unusual honey bee activity from

the owner Ken.

I was picking up some bee hive supplies

today and heard a weird tale of some unusual honey bee activity from

the owner Ken.

He's got a group of 7 hives that seem healthy but have not produced any

honey this year. They have over 6 acres of clover to work with along

with their neighboring hives which seem to be doing fine. The local

inspector was giving him a visit just before I got there and the

mystery had him stumped as well.

Maybe it's the quality of the clover, and maybe it's connected

to the reason why hay fields around here only got one good cutting this

year?

One month after putting our first set of fall

peas in the ground, differences between varieties is extremely

apparent. Usually we just plant Mammoth Melting Sugar snow peas

and some random kind of shelling pea (I'm still choosing my favorite

variety there.) But on a visit to Ohio, Mark fell in love with

sugar snap peas, so I added a third type --- Sugar Daddy.

One month after putting our first set of fall

peas in the ground, differences between varieties is extremely

apparent. Usually we just plant Mammoth Melting Sugar snow peas

and some random kind of shelling pea (I'm still choosing my favorite

variety there.) But on a visit to Ohio, Mark fell in love with

sugar snap peas, so I added a third type --- Sugar Daddy.

The photo to the left shows the massive size difference between the

Mammoth Melting Sugar peas (behind the trellis) and the

Sugar Daddy peas (in the foreground.) Yup, the snow peas are

already four times as big when planted in the same ground at the same

time! None of the peas are supposed to start bearing fruit until

nearly October, but our snow peas look like they might start flowering

any second. I sure do love our prolific and delicious Mammoth

Melting Sugar peas.

Shame-faced plug: Check out the chicken

waterers which fund this blog.

After

learning about all of the benefits of the new hybrid hazels, I had to

go out and buy one. A quick search of the internet turned up two

options. If I was willing to buy at least $75 worth of shrubs, I

could get proven hybrids for $3 apiece from Badgersett

Farms. I was

sorely tempted, but twenty plus shrubs seemed to be a bit too much for

us to handle.

After

learning about all of the benefits of the new hybrid hazels, I had to

go out and buy one. A quick search of the internet turned up two

options. If I was willing to buy at least $75 worth of shrubs, I

could get proven hybrids for $3 apiece from Badgersett

Farms. I was

sorely tempted, but twenty plus shrubs seemed to be a bit too much for

us to handle.

Instead, I joined the Arbor

Day Foundation's Hazelnut Project

for $20 and will soon receive my three "free" bushes. On the down

side, these bushes are experimental and may not have the proven results

I would have gotten from Badgersett Farms. On the up side, I'll

be participating in a scientific experiment, seeing how new hazel

varieties grow in different parts of the U.S. I'll look forward

to seeing how the hybrid hazelnuts integrate into our forest garden.

| This post is part of our Hybrid Hazelnut lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Time to put together the 4 supers I picked up yesterday.

I wonder if some Gorilla

glue might work as a quicker substitute to the old fashioned tiny

nails that sometimes cause a crack in the wood when being hammered in?

If you have ever wanted to know more about

the mechanics of the mind and how consciousness works then you might

find a new website I discovered a few months ago of great value.

If you have ever wanted to know more about

the mechanics of the mind and how consciousness works then you might

find a new website I discovered a few months ago of great value.

It's a husband and wife team that have struck out on their own with

what they call the Conscious

Media Network. They interview authors of books in the growing field

of consciousness and awareness and varying degrees of finding the

truth. They have hours and hours of interviews going back to 2005 and

it's all free at this time. You need to become a member to view the

interviews the same month they come out, but the archives are

generously offered as a gift to the public. I've heard enough really

good free interviews that I'll probably get around to sending them a

donation as a show of gratitude for a job well done.

Each interview is like a juicy sample snack of what new and or old

concept the author is exploring in their book or documentary. It's a

great way to taste a book and its essence before dedicating your

valuable time and resources to actually obtaining the book and finding

the time to read it. I dare anyone out there to listen to the Bob Dean

or Jim

Marrs interviews of the most far out and fantastic material

out there and try to dismiss what they're saying as "fantasy" or

"crackpottery". If anything it's going to really make you

think...Question Everything is the Conscious Media Networks motto and

it's a simple way to sum up this kind of search for truth at its most

fundamental level.

For this weekend, though, I'm just enjoying the floral abundance. The seeds I tossed in the ground this summer are finally starting to bloom, like the brilliant red zinnia on the right. At the edges of the woods, goldenrod, joe-pye-weed, wingstem, thistles, jewelweed, and ironweed are blazing.

In the garden, we're eating our first crisp lettuce with none of the summer bitterness. Butternut squash vines are dying back as sugars concentrate in their fruits and the last of our staggered corn plantings is starting to tassle. Even the air is starting to smell of autumn --- that first tang of falling leaves. The dog days of summer are over. It's all downhill from here.

Shame-faced plug: Check out the chicken

waterer that funds this blog.

--- various people including my mother and friends

Like many aspects of homesteading life,

beekeeping is a long term endeavor. A new package of honeybees is

a very small colony, and they spend a lot of their energy in the first

year beefing up into a regular size colony. If you do everything

right, they'll put away enough honey to get through the winter, but

they won't have much to spare. So, we don't plan to harvest any

honey until next fall.

Like many aspects of homesteading life,

beekeeping is a long term endeavor. A new package of honeybees is

a very small colony, and they spend a lot of their energy in the first

year beefing up into a regular size colony. If you do everything

right, they'll put away enough honey to get through the winter, but

they won't have much to spare. So, we don't plan to harvest any

honey until next fall.

Many American beekeepers harvest a lot of honey immediately, planning

to feed their bees sugar water or corn syrup to keep them going through

the late winter and early spring. We did feed our new

package bees sugar water, but I consider sugar water feeding a last

ditch effort afterwards. My gut reaction is that sugar water for

honeybees is a lot like corn chips for humans --- tasty, but not

fulfilling all of their nutritional needs. Instead, I want to

overcompensate and make sure they have plenty of honey to last them

until the first nectar flow next spring.

I read on one website that the modern tradition of harvesting honey in

late summer or early autumn is a recent invention. Supposedly,

beekeepers traditionally harvested honey in mid spring after the first

nectar flow began so that the beekeeper could be sure that the honey

they were taking was truly excess. Of course, you can't do this

if you use chemical mite control over the winter, but otherwise this

option seems to make a lot of sense.

Shame-faced plug: Check out the chicken

waterer that funds this blog.

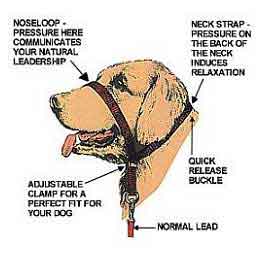

After

television watching, our number one pet peeve with American society is

probably dog care. Most dogs we meet are neurotic and/or out of

control. We're not saying that Lucy is the best dog in the world

(well, Mark might say that....), but she is a pleasure to be around and

makes life on the farm easier.

After

television watching, our number one pet peeve with American society is

probably dog care. Most dogs we meet are neurotic and/or out of

control. We're not saying that Lucy is the best dog in the world